inbox and environment news: Issue 593

August 6 - 12, 2023: Issue 593

Time Of Wiritjiribin

August

Female Lyre bird - Elanora Heights

Photo by Selena Griffith, May 29 2023

Selena says ''this one followed me along the path. Never been so close.''

Bushcare Training Day At North Narrabeen

- Weed identification and best practice removal techniques

- Native plant identification and weed species including lookalikes

- Hands-on weed removal

- Bring along your unknown plant species for identification

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group Begins

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

2023 Banksia Foundation NSW Sustainability Awards Open For Nominations

Pittwater Garage Sale Trail Returns: Repurpose Your Items

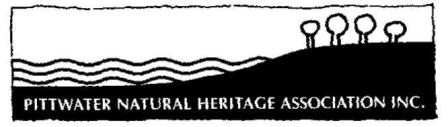

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Sunday August 27 2023 From 10:00-12:15 - Turimetta Beach Clean Up

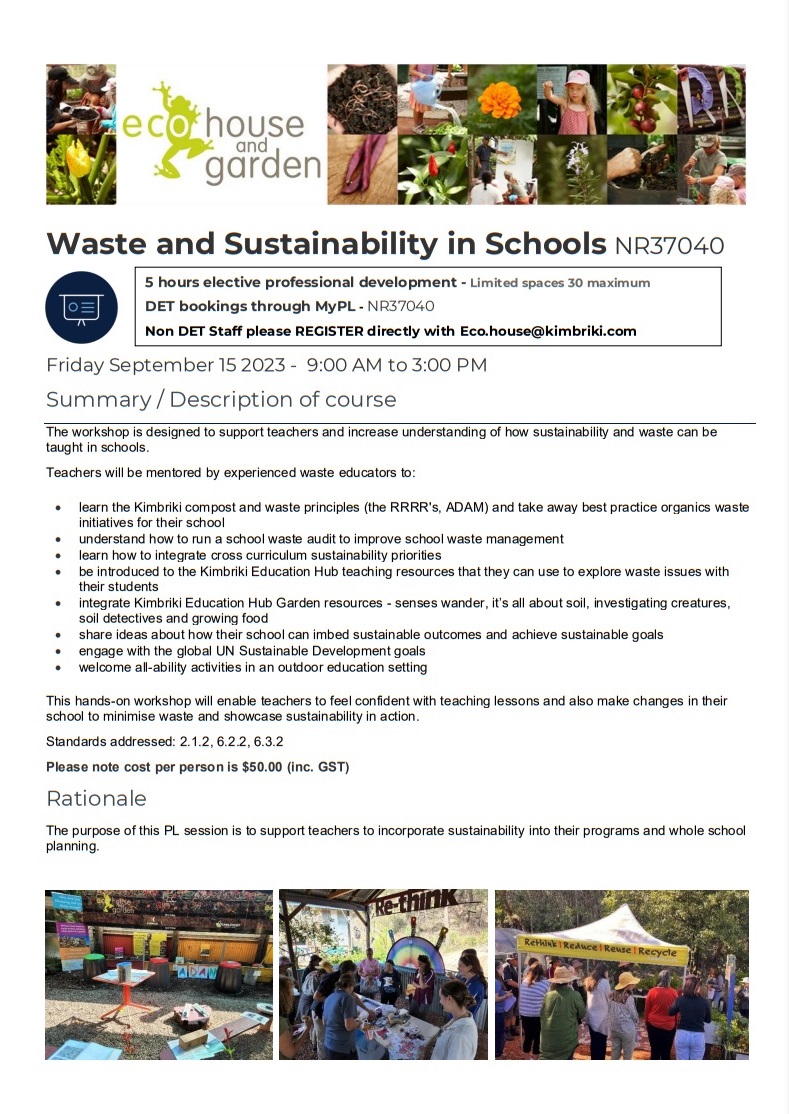

Waste And Sustainability In Schools NR37040: At Kimbriki

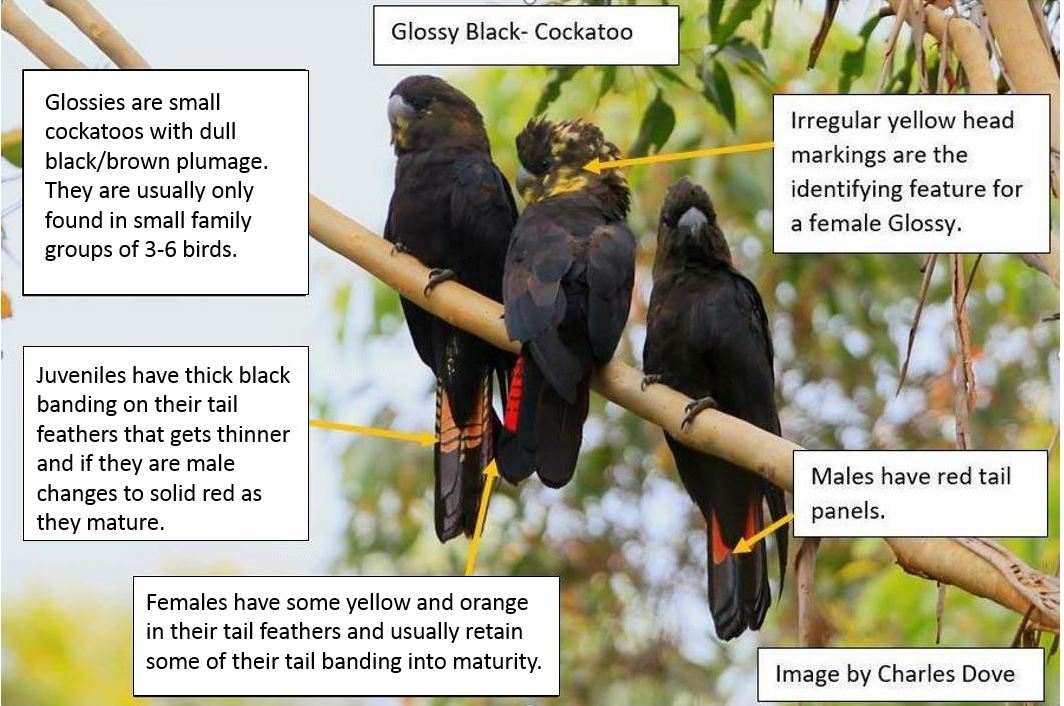

Seen Any Glossies Drinking Around Nambucca, Bellingen, Coffs Or Clarence? Want To Help?: Join The Glossy Squad

- a female bird (identifiable by yellow on her head) begging and/or being fed by a male (with plain black/brown head and body and unbarred red tail feathers)

- a lone adult male, or a male with a begging female, flying purposefully after drinking at the end of the day.

NSW Clearing 640 Football Fields Of Land Per Day: The Majority Unexplained

NSW Land Clearing Data Released

- 15% increase for agricultural

- 35% decrease for native forestry harvesting

- 21% decrease in clearing for infrastructure.

Forestry Corp Taking A Wrecking Ball To Gumbaynggirr Culture And The Great Koala National Park

80-Plus Groups Worldwide Demand End To Greenwashing Maugean Skate Extinction With Farmed Salmon Accreditations

Critically Endangered Fledgling Hooded Plover Takes Long Haul Flight To North Coast

New Outback Park In NSW Protects Important Wetlands

Blue Mountains National Park And Kanangra-Boyd National Park Draft Plan Of Management: Public Consultation

- improving recognition of the parks significant values, including World and National Heritage values, and providing for adaptive management to protect the values

- recognising and supporting the continuation of partnerships with Aboriginal communities

- providing outstanding nature-based experiences for visitors through improvements to visitor facilities - including:

- Opportunities for supported or serviced camping, where tents and services are provided by commercial tour operators, may be offered at some camping areas in the parks

- Jamison Creek, Jamison Valley Walk-in camping Potential new camping

- Leura Amphitheatre Jamison Valley Walk-in camping Potential new camping

- Mount Solitary Jamison Valley Walk-in camping Potential new camping

- Maxwell’s HuC Kedumba Valley Cabin/hut Potential new accommodation

- Kedumba Valley Maxwell’s Hut (historic slab hut) - Building restoration in progress; potential new Accommodation for bushwalkers

- Government Town Police station; courthouse - Potential new Visitor accommodation

- write clearly and be specific about the issues that are of concern to you

- note which part or section of the document your comments relate to

- give reasoning in support of your points - this makes it easier for us to consider your ideas and will help avoid misinterpretation

- tell us specifically what you agree/disagree with and why you agree or disagree

- suggest solutions or alternatives to managing the issue if you can.

Plans For New Wind Energy Project At Spicers Creek On Public Exhibition

Green Light For Two New Batteries To Help Secure Power For 100,000 Homes

NSW Landholders To Be Rewarded For Private Land Conservation

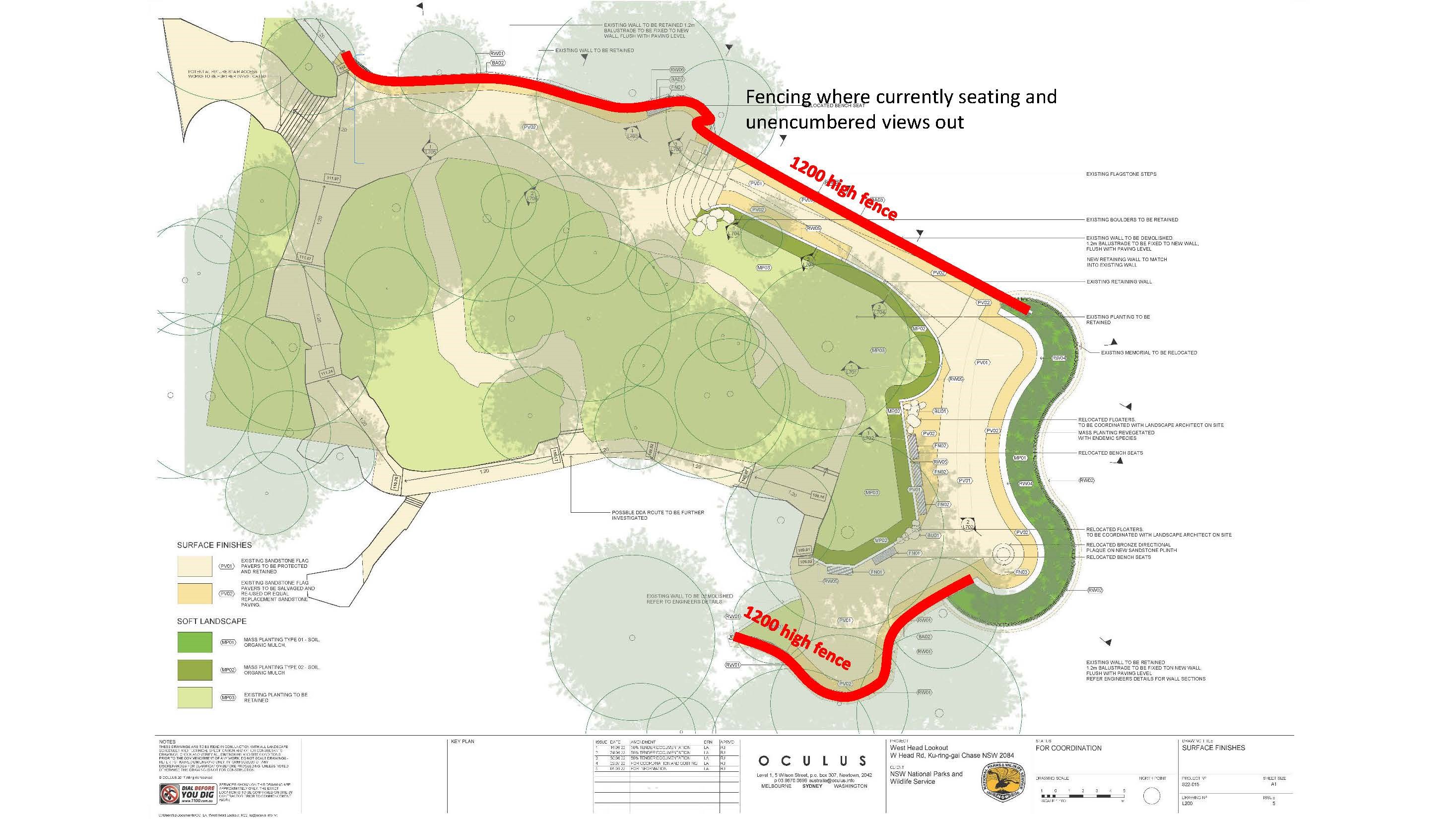

Areas Closed For West Head Lookout Upgrades

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

- West Head lookout

- The loop section of West Head Road

- West Head Army track.

Vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians will have access to the Resolute picnic area and public toilets. Access is restricted past this point.

The following walking tracks remain open:

- Red Hands track

- Aboriginal Heritage track

- Resolute track, including access to Resolute Beach and West Head Beach

- Mackeral Beach track

- Koolewong track.

The West Head lookout cannot be accessed from any of these tracks.

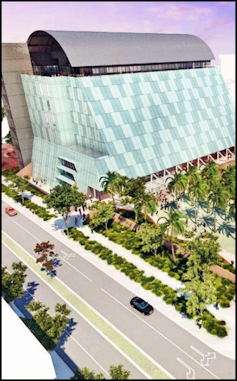

Image: Visualisation of upcoming works, looking east from the ramp towards Barrenjoey Head Credit: DPE

Bush Turkeys: Backyard Buddies Breeding Time Commences In August - BIG Tick Eaters - Ringtail Posse Insights

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

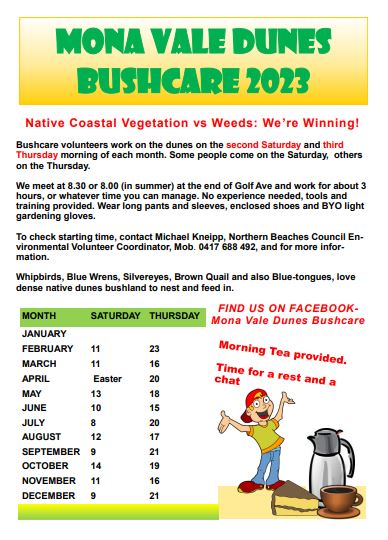

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Leaving dog and cat poo lying around isn’t just gross. It’s a problem for native plants and animals, too

Dodging dog poo along the local path has become something of an Olympic sport of late. I thought I’d count path-side dog poo on my bike ride the other day and gave up after counting 30 piles in the first kilometre. It really does feel a bit out of control at the moment.

We know leaving dog poo lying around is bad for human health. But have you ever wondered what all this mess means for native wildlife?

It turns out pet poo – including both dog and cat poo – can have a number of negative effects on native plants and animals. And some of these might surprise you.

1. Unwelcome Fertiliser

Just like adding manure to the garden, pet poo left on the ground is a fertiliser. But not all plants thrive on excess.

Australian soils are naturally nutrient-poor and native plants and fungi are incredibly well-adapted to these conditions.

Yes, wildlife go to the toilet in nature too. But the difference is they also eat in nature – they’re part of the system.

Our pets, on the other hand, are fed nutrient-rich meals in our backyards and kitchens and then deliver these outside nutrients into the ecosystem. Pet poo can quickly find its way into waterways, which can drive algal blooms.

Researchers in Berlin estimated that if nobody picked up after their dogs, more than 11kg of nitrogen and 4kg of phosphorous per hectare would be added to urban nature reserves each year – levels that would be illegal for most farms.

2. Lurking Disease

Pet cats aren’t off the hook. If you have a roaming kitty, they could be spreading toxoplasmosis – a disease that can cause serious illness and even death in native mammals.

Symptoms include blindness and seizures, and have been observed in kangaroos, wallabies, possums, wombats, bandicoots and bilbies. The disease even increases “risky” behaviours, with infected animals more prone to wandering around the open or being unafraid of predators.

It’s morbidly fascinating. The parasite causing the disease, Toxoplasma gondii, has two phases to its lifecycle. In the first phase, it’s happy hanging out inside pretty much any warm-blooded animal. But to complete the second phase, it has to jump to a cat. The easiest way to do this is to make your current host easy prey, hence the symptoms that debilitate native wildlife or make them prone to dangerous decisions.

Infected cats shed the parasite in their poo. So whenever native animals can come into contact with cat poo, they’re at risk. Researchers from the University of British Columbia found “wildlife living near dense urban areas were more likely to be infected”, citing domestic cats as the most likely culprit.

Worse, the parasite can lay dormant in poo for as long as 18 months, waiting for a host to jump into.

3. Eau De Predator

Finally, and probably the most obvious: dog poo might signal to wildlife that predators are about and they should stay away.

Even though dogs are a new predator to Australian wildlife, our native species have had enough experience existing alongside dingoes to consider your pooch a threat.

Recent research shows that in 83% of tests, Australian native mammals recognised dogs as a threat – with dog poo being a common trigger.

This means the signs and smells your dog leaves out and about can affect the behaviour of native wildlife.

For example, bandicoots in Sydney were less likely to visit backyards that had a resident dog, even if it was kept inside at night.

‘What Wildlife? What Nature? We Live In The City!’

It might surprise you to know we share our cities and towns with a huge range of native animals – even rare and endangered ones.

And as people have paid more attention to the nature in their local neighbourhood in recent years, we’re becoming more aware of the wildlife living right beneath our noses.

These species often depend on a seemingly rag-tag collection of urban green patches such as nature strips, utility easements, sports ovals and public gardens.

If these are all littered with smelly signs for wildlife to stay away, places safe for wildlife become even rarer in our cities. Reining in the pet poo problem is an easy way to reduce our impact.

The old adage “take only photographs, leave only footprints” is a good rule of thumb. Pick up after your pet and, importantly, take it with you to the nearest bin – don’t leave plastic bags dangling from fences like ornaments on the world’s worst Christmas tree. ![]()

Kylie Soanes, Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Unique study shows we can train wild predators to hunt alien species they’ve never seen before

Humans have trained domestic animals for thousands of years, to help with farming, transport, or hunting.

But can we train wild animals to help us in conservation work? Wild animals can be taught to recognise dangerous predators, avoid toxic food, and stay away from people.

However, there are few examples of using classical learning techniques to train free-living animals to act in a way that benefits their ecosystem. In our newly published study in Biological Conservation, we trained wild Australian native predatory rats to recognise an unfamiliar species of cockroach prey. It worked – in a simulated cockroach invasion, this training increased predation rates by the rats.

Growing Number Of Aliens

As humans have engaged in global trade, various species have moved across otherwise impossible-to-cross geographical barriers and into new environments. These species are known as alien species, and their number continues to grow.

Some alien species are relatively harmless in their new environment, and can even positively affect the ecosystem. However, many others have costly and devastating impacts on biodiversity and agriculture.

Not all species that arrive in new environments become established or spread. Even fewer of these species become invasive. Yet we don’t really know why some species are successful and others aren’t, and there are many different theories. One reason some species fail to thrive in new environments is when native species resist, either by eating or simply outcompeting the arrivals.

However, native species can only resist against alien species if they can respond appropriately, which they may not do if they’ve never encountered the invaders before (biologists call this being “naive”).

Naivete can occur when two species with no recent evolutionary or ecological history come into contact with one another. Prey naivete is well documented, and the effect of alien predators on native prey that can’t recognise or escape them is significant.

But the role of native predator naivete in biological invasions is less clear. Native predators may not recognise an alien prey species or lack the ability to hunt them effectively. Sometimes predators may simply prefer to hunt their natural prey. When predators are naive, alien prey can establish and spread unchecked.

Speeding Up A Natural Process

Native predators do eventually learn to hunt alien prey, but this process can take a long time when prey aren’t encountered often.

We wanted to know if we could speed up learning by exposing a free-living native predator to the scent of a novel prey species paired with a reward.

We conducted our study on bushland in the outskirts of Sydney, New South Wales, using native bush rats (Rattus fuscipes) as our model predator. Our chosen alien prey species, speckled cockroaches (Nauphoeta cinerea), don’t live in Sydney and surrounds, so rats have no experience with them.

We housed cockroaches in small boxes for days at a time with absorbent paper on the floor to collect odour. When using them as prey, we froze and tethered the cockroaches to tent pegs, to avoid accidental introduction of cockroaches in the area.

We confirmed the presence of bush rats at 24 locations, and randomly allocated 12 as training sites and 12 as non-training (control) sites. At the training sites, we placed a metal tea strainer with the cockroach smell, and three dead cockroaches as a reward. The tea strainer and cockroaches were tethered to a tent peg in the ground so rats couldn’t carry them away.

We used cameras to observe the rat behaviour, and checked the training stations every one to two days. We also moved the stations so the rats wouldn’t just learn to associate the reward with the location.

Trained For An Invasion

Immediately after training, we conducted a simulated invasion at all sites. The invasion involved ten dead and tethered cockroach “invaders”. The number of “surviving” (that is, uneaten) cockroaches was recorded each day for five days.

We compared prey survival rates in sites with trained and untrained rats, and found cockroach prey in training sites were 46% more likely to be eaten than prey in non-training sites.

We also found the number of cockroaches eaten during training was a significant predictor for how many were eaten on the first night of the “invasion”.

We also wanted to ensure we had not just attracted more rats to training sites during the training process. To do this, immediately after the invasion we used cameras to compare rat visits to all sites using a peanut oil attractant. There was no difference between training and non-training sites.

Our study is the first to train free-living predators to hunt species they’ve never seen before. It shows the potential for training our native species to fight biological invasions. More broadly, we think our study adds to the growing evidence that training animals can help to address a variety of problems, such as birds picking up litter and rats sniffing out landmines.![]()

Finn Cameron Gillies Parker, PhD candidate, University of Sydney and Peter Banks, Professor of Conservation Biology, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wild bird feeding surged worldwide during lockdowns. That’s good for people, but not necessarily for the birds

Feeding wild birds in backyards was already known to be extremely popular in many parts of the northern hemisphere and in Australia, despite being strongly discouraged. But the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns led to a dramatic increase in wild bird feeding around the world, our research published today shows. There was a surge in interest beyond traditional bird-feeding countries in North America, Europe and Australia: 115 countries in total, including many where feeding was assumed not to occur.

Those opposed to feeding wild birds cite a plethora of reasons:

- the spread of diseases (well-documented in the US and UK)

- poor nutrition as a result of an unbalanced diet

- advantaging already abundant species

- changing community structure (birds that visit feeders prosper at the cost of those that don’t)

- even altering migration patterns.

These impacts occur everywhere wild birds are fed and are potentially serious.

On the other hand, engaging with wild birds in this way is now recognised as one of the most effective ways people can connect with nature. There is strong evidence that spending time in natural settings is good for people’s wellbeing and mental health. This becomes increasingly important as more and more of the world’s people live in large cities.

These trends mean the simple, common practice of attracting birds to your garden by feeding them is taking on much greater significance for the welfare of both birds and people.

What Did The Study Look At?

Previous studies documented a global increase in birdwatching during lockdowns. We wondered whether interest in feeding birds might have increased similarly as well. That usually means buying seed mixes and providing a feeder. To be included in our study, some cost was required; discarded food scraps were not counted as feeding.

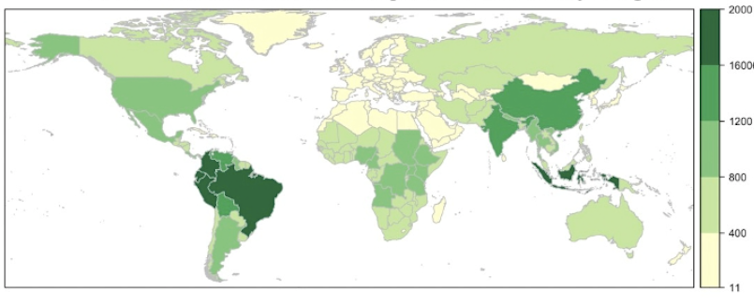

It was important to go beyond the countries where we already knew feeding was common. We wanted to compare the interest levels for more than 100 countries during and after lockdowns. We also examined whether the level of interest in bird feeding was related to the diversity of birds in each country, a measure known as “species richness”.

We assessed the weekly frequency of search terms, including “bird feeder”, “bird food” and “bird bath”, using Google Trends for all countries with sufficient search volumes from January 1 2019 to May 31 2020. We wanted to see if these searches increased during each country’s specific lockdown period (generally around February-April 2020). We drew on bird species richness data for each nation from the BirdLife International database.

Comparing the interest volume for 52 weeks leading up to the lockdown with the week immediately before, we found no discernible change. Within only two weeks, however, the frequency of searches showed a surge in bird feeding interest during the general lockdown period across 115 of the countries surveyed. This happened in both the northern and southern hemispheres.

What Explains The Change?

There are several possible reasons for this change. People throughout the world were forced to remain close to home. The backyard or nearby park became the focus of attention, perhaps for the first time.

Lockdowns were a time of high anxiety and stress. Aspects of life that seemed to be carrying on regardless, such as birds arriving each day to be fed, may have been a course of comfort and reassurance.

Feeding birds has been found to enhance feelings of personal worth and peace. Presumably, it’s because of the relative intimacy associated with being able to attract wild, unrestrained creatures to visit by simply providing some food.

Bird feeding is also cheap, simple and available to virtually everyone. Birds will visit a feeder in a private garden, a public park or even a balcony on a residential tower.

And What Difference Does Bird Diversity Make?

We found a clear association between the level of interest in feeding and species diversity. Countries that lacked bird-related search interest had an average of 294 bird species. In contrast, those countries with clear interest had an average of 511 species.

This clear difference suggests that having a greater variety of species prompts more bird feeding. It may also mean places with more species have a larger number of bird types living in their cities (where most feeders live). This remains to be be investigated. We do know that feeding birds leads to more birds overall, but not more species.

Because we used Google searches as the proxy measurement for bird-feeding interest, bird-feeding practices in countries with lower income or less internet access may not have been adequately captured. Nonetheless, our method was able to detect a surge of interest in bird feeding in countries such as Pakistan and Kenya.

The COVID-19 lockdowns seemed to encourage people all over the world to seek connection and interaction with their local birds. We hope future studies can further analyse the global extent of bird feeding and capture more data in previously understudied countries.

Feeding birds is obviously very popular. For people. But it can lead to problems for the birds. To minimise the risks, keep in mind some simple rules: ![]()

- keep the feeder extremely clean (disease is always a concern)

- don’t put out too much food (they don’t need it)

- provide food that is appropriate for the species (never human food – buy wild bird food from pet food companies).

Darryl Jones, Deputy Director of Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Antarctica is missing a chunk of sea ice bigger than Greenland – what’s going on?

Ella Gilbert, British Antarctic Survey and Caroline Holmes, The Open UniversityDeadly heatwaves, raging wildfires and record global temperatures are upon us. But far from the flames, at the southernmost tip of the planet, something just as shocking is unfolding.

It’s Antarctic winter, a time when the area of floating sea ice around the continent should be rapidly expanding. This year though, the freeze-up has been happening in slow motion.

After reaching a record low minimum extent this summer there is now an area of open ocean bigger than Greenland. If the “missing” sea ice were a country, it’d be the tenth largest in the world.

Who Cares About Antarctic Sea Ice?

In the face of more immediate climate concerns, why does Antarctic sea ice matter?

Floating sea ice is a pivotal climate puzzle piece. Without it, global temperatures would be warmer because its bright, white surface acts like a mirror, reflecting the sun’s energy back to space. This keeps the Antarctic – and by extension, the planet – cool.

Antarctic sea ice also plays a particularly important role in controlling ocean currents and may act as a buffer that protects floating ice shelves and glaciers from collapsing and adding to global sea levels.

In short, the loss of Antarctic sea ice matters for the whole planet.

Southern Sea Ice: A Short History

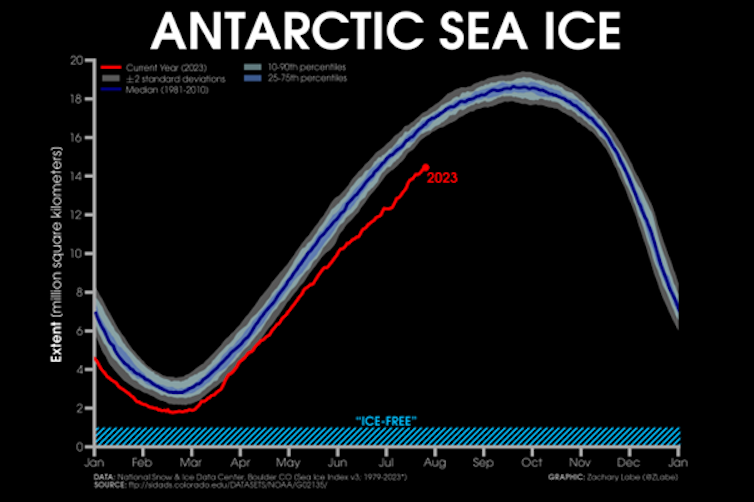

Every year Antarctic sea ice undergoes a transformation: from its summer minimum in February, its area increases more than sixfold during the winter freeze-up which reaches its height in September. A clear way to monitor the health of Antarctic sea ice is to track these peaks and troughs.

Records began in 1979 and until 2015, the yearly average extent of frozen sea around Antarctica was increasing ever so slightly. Yet in the past seven years, Antarctic sea ice has changed dramatically.

After a record high two years prior, the amount of sea ice fell dramatically at the end of 2016 to a record minimum in February 2017. This was followed by successive low years with the southern hemisphere summer record again being broken in February 2022 and most recently, a new lowest extent of 1.79 million square kilometres being recorded in 2023, a fall of nearly 10% from last year’s summer record.

Since February 2023, slow regrowth has meant sea ice has fallen further and further behind where it should be for the time of year.

And now, in July, what we’re seeing is truly remarkable.

A Complex Picture

Antarctic sea ice, and how it’s affected by climate change, has been so hard to understand because there are so many factors at play.

Wind patterns, storms, ocean currents and air and ocean temperatures all affect how much of the sea around Antarctica is covered by ice and they often push and pull in different directions. This means it can be hard to link the behaviour of Antarctic sea ice in any particular year, or over several years, to just one factor.

This complexity is behind the perplexing increase in Antarctic sea ice extent observed between 1979 and 2015, and what makes it so hard to understand current conditions.

Before 2015, contrasting trends in sea ice growth in different regions of the vast continent mostly counterbalanced each other. What’s remarkable about 2023 is that these regional differences are largely absent.

How Rare Is It?

This year’s record low summer minimum and record slow freeze-up are astonishing because they fall so far outside the range we have come to expect.

Antarctic sea ice varies a lot year-to-year, but even by Antarctic standards this is well outside the bounds of normality. Some experts have attempted to put a number on just how rare this would be without climate change and arrived at “a once in 7.5-million-year event”.

However, while the current situation is certainly off the charts, those charts don’t go back very far, and so it’s hard to make these sorts of statements with any real certainty.

Given how complex a system it is, we can’t say conclusively whether the past 40 years (the period for which we have satellite observations) are an accurate reflection of the “natural” behaviour of Antarctic sea ice. In fact, there’s good reason to think they aren’t. Which makes it difficult to say exactly how unusual this year’s values are.

However, while we may not be able to put an exact number on it, we know that this is a rare event.

Is It Climate Change?

Compared with Arctic sea ice, the precipitous decline of which can be robustly linked to rising temperatures, Antarctic sea ice has proved more enigmatic.

In response to greenhouse gas emissions, models have long predicted a drop in Antarctic sea ice: a prediction that previously appeared at odds with the data.

As the ocean and atmosphere warm, we might expect sea ice sandwiched between the two to shrink. But as scientists have come to learn, Antarctic sea ice is more complicated than that.

Models seem unreliable on this topic, which means we still don’t know what Antarctic sea ice decline will look like. And while seven days may be a long time in politics, seven years is a short time when it comes to the climate. It is too early to say conclusively whether the recent dramatic fall in Antarctic sea ice extent is simply a blip in the record or, as now seems more likely, the first sign of a longer-lasting reduction induced by climate change.

What Happens In Antarctica Doesn’t Stay In Antarctica

Regardless of the vagaries of Antarctic sea ice behaviour, the polar regions play a vital role in the climate system. And they are changing before our very eyes.

Antarctica isn’t just for the penguins: it matters for all of us.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Ella Gilbert, Climate Scientist, British Antarctic Survey and Caroline Holmes, Polar Climate Scientist, British Antarctic Survey, Associate Lecturer, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A carbon tax can have economic, not just environmental benefits for Australia

A new study has found that a carbon tax, accompanied by “revenue recycling”, can produce both environmental and economic benefits for Australia.

Revenue recycling means money reaped from a carbon tax would be redirected back into the economy. This means the money accumulated from the tax would be redistributed between different stakeholders in the economy without increasing the government’s revenue.

To be more specific, the tax income should be used to support consumption, invest in new research and development projects, and subsidise energy saving and pollution reducing programs. Using this approach makes the tax more politically appealing to companies and other opponents.

Australia’s Experience With A Carbon Tax

Debate about a carbon tax has always been heated in Australia. The Gillard government introduced a carbon pricing scheme in 2012 which involved an initial rate of $23 per tonne on about 500 big carbon emitters, including the electricity industry.

The scheme contained compensation measures including increases in money to government payment recipients and a program to help emissions-intensive, trade-exposed industries reduce carbon emissions, which were themselves a form of recycling.

Despite reducing emissions, the tax only lasted two years before it was terminated by the Abbott government, which argued the tax was costing big companies and causing electricity prices to rise.

I examined how such a scheme could work again, basing the design on the models used in Norway, Ireland and Switzerland. I simulated Australia’s economy from 2020 to 2035 to examine the impact of a carbon tax policy with the associated revenue recycling approach on prices, total emissions and economic growth.

The first step in the design is identifying a tax rate and the reach of the policy. Research shows that a uniform rate covering the whole industry sector generates the greatest environmental benefits.

As well as suggesting a uniform tax rate on all sectors including the electricity sector (which is excluded from the current emissions safeguard mechanism), my study recommends starting the tax rate at $23 (the same rate applied in Gillard’s scheme) in 2023 and increasing it gradually to $70 in 2030.

The rate would stay at this level until 2035.

A carbon tax increases the cost of production and leads to an increase in the inflation rate. The inflation impact of this policy is estimated to be 0.5% in 2023, increasing substantially to 1.52% in 2035.

Rising inflation reduces the spending power of families and reduces consumption and economic growth. Considering consumption has a fundamental role in a growing economy, the accumulated tax revenue would be used to keep consumption unchanged after implementing a carbon tax.

How A New Version Of The Tax Would Work

My study recommends using the accumulated carbon tax revenue to lower income taxes. This would leave more money for families, thereby reducing the impact of inflation, caused by the tax, on the economy.

As well as strengthening families’ spending power, a share of the tax revenue would be invested in research and development projects. This would create new jobs and provide a baseline for a prosperous economy.

My study recommends that in the first year, all the tax revenue would be used to support consumption. However, the amount of money allotted to investment would rise from the second year as the carbon tax rate increases. It is estimated that about $57 billion would be available for new technologies over 13 years under this carbon tax.

Imposing a carbon tax would also provide a financial incentive for industry to reduce its fossil fuel use. It would motivate the sector to shift to low-carbon technologies as they would bear a smaller tax bill and reap larger profits.

My study concludes Australia could reduce carbon emissions by 35% while GDP would increase by 0.286% by 2035 and new jobs would be created in research and development. Following the recommended carbon tax design, Australia’s transition to a low-carbon economy would be accelerated, which would benefit both the economy and the environment.![]()

Mona Mashhadi Rajabi, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Out of danger because the UN said so? Hardly – the Barrier Reef is still in hot water

Today is a good day to be Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek. UNESCO, the United Nations body expected to vote on whether to list the Great Barrier Reef as “in danger”, instead deferred the decision for another year. This, an insider told French newspaper Le Monde, was largely due to the change in approach between the former Coalition government and Labor.

“It’s a bit like night and day,” the insider said – which was promptly included in Plibersek’s media release.

So, it’s a good day for the government. But is it a good day for the reef? No. The longstanding threats to the world’s largest coral ecosystem are still there, from agricultural runoff, to shipping pollution, to fisheries, although we have seen improvement in areas such as water quality.

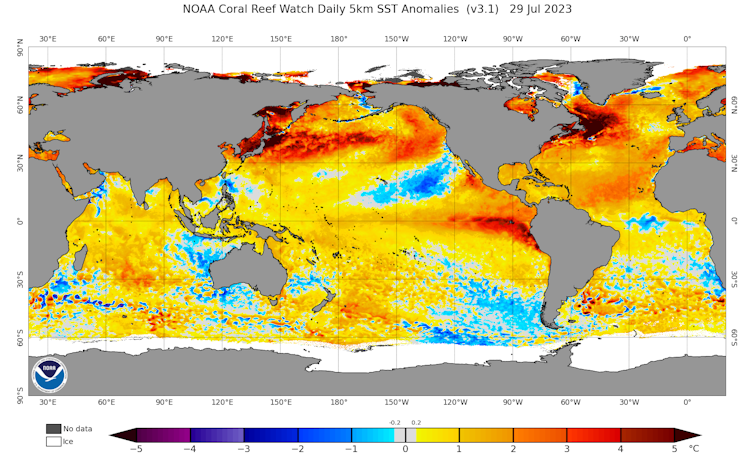

But any incremental improvement will be for naught if we don’t respond to the big one – climate change – with the necessary urgency. This year has seen record-breaking heat and extreme weather, with intense heating of the oceans during the northern summer. These intense marine heatwaves have devastated efforts to regrow or protect coral in places like Florida. And our own summer is just around the corner.

It is not hyperbole to say the next two years are likely to be very bad for the Great Barrier Reef. It’s already enduring a winter marine heatwave. Background warming primes the reef for mass coral bleaching and death. We’ve already experienced this in 2016-17, which brought back-to-back global mass coral bleaching and mortality events including on the Great Barrier Reef. We can expect more as global temperatures continue to soar.

While the government may congratulate itself on not being the previous one, it’s nowhere near enough. We’re facing D-Day for the reef, as for many other ecosystems. Incrementalism and politics as usual are simply not going to be enough.

What Has The Government Done For The Reef To Date?

To its credit, Labor has made some marginal improvements to the Great Barrier Reef’s prospects. The list includes: legislating net zero greenhouse emissions, with a 43% cut within seven years; improving water quality with revegetation projects and work to reduce soil erosion; and ending gillnet use in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park by 2027.

For at least a century, cattle, sugarcane and other farmers have relied on rivers to take animal waste and fertiliser runoff away from their properties. In much of Queensland, that means the runoff heads for the Great Barrier Reef instead. We did see some improvement under the Coalition government, which put A$443 million into trying to solve the issue. Labor has put in a further $150 million. But the water quality problem is still not solved.

Ending gillnet use in the marine park is also welcome, given these nets can and do catch and kill sharks, dugongs and turtles. But challenging though these issues are, they pale in comparison to climate change.

Tinkering While The Reef Burns

When coral is exposed to warmer water than it has evolved to tolerate, it turns white (bleaches) – expelling its symbiotic algae. If the water stays too hot for too long, the corals simply die en masse.

You might have seen the positive reports on coral regrowth during the three recent cooler La Niña years and wonder what the issue is. Isn’t the reef resilient?

Yes – to a point. But after that point, the coral communities collapse. The world is having its hottest days on record. Coupled with a likely El Niño, the reef will likely face the hottest waters yet.

That’s because we still haven’t tackled the root cause. Greenhouse gas emissions are still going up. Year on year, we’re trapping more heat, of which 90% goes into the oceans. Antarctic sea ice is not reforming as it should after last summer. Coral restoration efforts in the United States had to literally pull their baby corals out of the sea to try to keep them alive, as the water was too hot to live in.

The North Atlantic Ocean is far warmer than it should be, amid a record-breaking northern summer. After the equinox next month, it will be our turn to face the summer sun once more.

Is the Great Barrier Reef in danger? Of course it is. We should not pretend things are normal and can be handled routinely. This year, we’re beginning to see the full force of what the climate crisis will bring. We have clearly underestimated the climate’s sensitivity to rising carbon dioxide levels, and the gloomy predictions I made more than 20 years ago are looking positively optimistic.

And still we fail to face up to the fact that the Great Barrier Reef is dying. We thought we might have had decades but it may be just years. Before 1980, no mass bleaching had ever been recorded. Since then it has only become more common.

Incremental efforts to save the reef, such as looking for heat-tolerant “supercorals”, or replanting baby coral, now look unlikely to work. We don’t have decades or the capacity to find and cultivate resilient corals at scale. And we certainly do not have the massive funding required to replant even a small coral reef.

For people like us who work in the field, it is a devastating time. I now know the feeling of having a broken heart. The pace and intensity of climate change risks rendering all our efforts over the years null and void. It’s almost impossible to look directly at what this will mean for this immense living assemblage, which first began growing more than 600,000 years ago along the Australian east coast.

Giving the government more time to show the reef is improving seems like a fool’s errand. Time is precisely what we don’t have. ![]()

Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, Professor, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why is Australia having such a warm winter? A climate expert explains

If you’ve been out and about the past few days, you may have noticed Australia is experiencing an unseasonably warm winter. It’s been t-shirt weather across many parts of the country’s east, including Sydney where temperatures topped 25℃ on Sunday.

Meanwhile, at high altitudes, the cover at some snowfields remains lacklustre, even after warm conditions forced a delay to the start of the traditional ski season.

All this comes after the world experienced its hottest month since reliable records began. July brought an incredible 21 of the warmest 30 days ever recorded – prompting the United Nations to declare a new era of “global boiling”.

So what’s going on with the weather in Australia? Should we just enjoy the pleasant conditions, or is it a troubling sign of what’s to come under climate change?

The Nice Weather, Explained

Australia’s unseasonably warm conditions are the result of both natural drivers of our weather and continued global warming.

Since early July, warmer and drier conditions have dominated, due to a high pressure system sitting stubbornly over Australia at the moment. The clear conditions are leading to warmer daytime conditions.

For example, daytime temperatures in Canberra in July – historically known for its cold winters – were the warmest on record, despite frequent frosty mornings. Sydney has just experienced its warmest July on record, too.

The high pressure has caused the air over the continent’s interior to warm. When cold fronts move across the south of Australia they push this warm air ahead of them, bringing warm and windy conditions to southern coastal areas. This is similar to the weather pattern we see in summer when cities such as Adelaide and Melbourne experience their hottest days.

On Thursday, an approaching cold front is forecast to lift temperatures ahead of it to about 23℃ in Adelaide, 20℃ in Melbourne and 18℃ in Hobart. These are very warm temperatures in these locations for early August.

And what about the oceans? Around Australia, oceans are a bit cooler than average in some places including to the northwest of the continent.

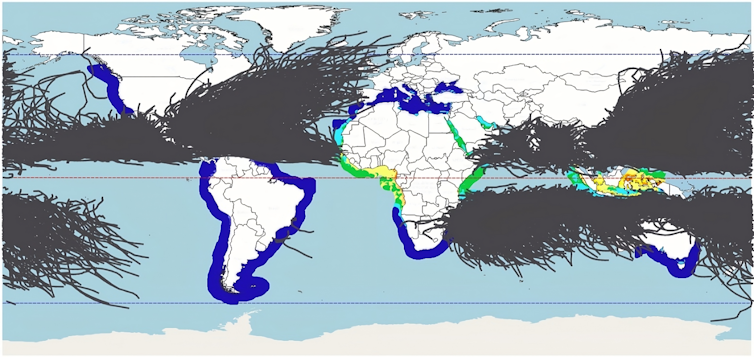

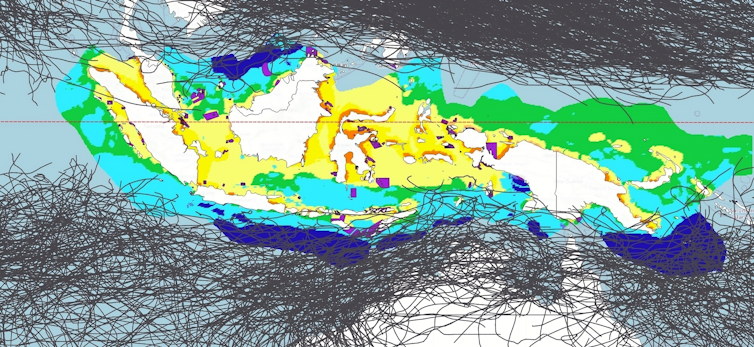

But as the image below shows, ocean temperatures are currently above normal in many places around the world, including the west Indian Ocean and the central and eastern tropical Pacific. This indicates a developing El Niño and positive Indian Ocean Dipole – two natural climate drivers that affect Australia’s weather patterns.

This difference in ocean temperatures reduces the amount of atmospheric moisture over southern and eastern Australia. It also makes low pressure systems weaker and less frequent, reducing rainfall over the region.

Over the coming months, warm and dry weather is expected to continue. For the rest of winter and spring, it’s expected to be drier than normal in the southwest of Western Australia and much of the east of the continent. And the whole of Australia is predicted to be warmer than normal during this period. Of course, this doesn’t rule out occasional cool, wet spells.

So is climate change a factor here? Yes. Australia’s land areas have already warmed by 1.4℃ since pre-industrial times. This is the result of humans burning fossil fuels and releasing greenhouse gases.

The record winter warmth is part of a long-term upward trend in Australian winter temperatures.

As I’ve written previously, there has been at least a 60-fold increase in the likelihood of a very warm winter that can be attributed to human-caused climate change.

And we’re likely to see more record warm winters as the planet continues to warm.

Looking North

Of course, Australia’s spell of warm weather seems harmless compared to the Northern Hemisphere’s weird and wild summer.

There, simultaneous extreme heatwaves have struck all four continents in recent weeks. Ocean temperatures are well above previous record highs for this time of year. Last week, 1,000 wildfires burned in Canada alone.

The planet’s warmest average temperatures typically happen in July. That’s because the Northern Hemisphere’s large land masses heat up more quickly than the oceans, in response to the high amounts of radiation from the sun. Still, the heat of the last few weeks has been unprecedented.

The heatwaves are linked to high-pressure weather systems that are “blocking” or deflecting oncoming low-pressure systems (and associated clouds and rain). On top of this, human-caused global warming is greatly increasing the chance of record-breaking extreme heat events and concurrent heatwaves across many regions.

Worryingly, a rapid analysis by international experts suggests the extreme heat should not be viewed as unusual, given the effects of climate change. For example, it says China’s recent record-breaking heatwave should now be expected about once in every five years, on average.

Not all extreme weather events can be attributed to human-caused climate change. But the study found climate change significantly contributed to the recent heatwaves in China, North America and Europe.

A Sign Of What’s To Come

The Northern Hemisphere’s heatwaves are very alarming. But Australia’s temperatures are also unusually high for winter – and this is also cause for concern.

Warm winters in Australia can negatively affect some parts of the economy, including the ski industry. It also disrupts flora and fauna and increases the chance of “flash droughts” – where drier-than-normal conditions turn into severe drought in the space of weeks.

The warm, dry conditions may also lead to an earlier start to the fire season in Australia’s southeast.

So while we may appreciate warm winter weather, we mustn’t forget what’s driving it – and how urgently we need to stabilise Earth’s climate by slashing greenhouse gas emissions.![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Here’s how wastewater facilities could tackle food waste, generate energy and slash emissions

Melita Jazbec, University of Technology Sydney; Andrea Turner, University of Technology Sydney, and Ben Madden, University of Technology SydneyMost Australian food waste ends up in landfill. Rotting in the absence of oxygen produces methane, a potent greenhouse gas. While some facilities capture this “landfill gas” to produce energy, or burn it off to release carbon dioxide instead, it’s a major contributor to climate change. Valuable resources such as water and nutrients are also wasted.

Composting food waste is the most common alternative. In the presence of oxygen, microbes break down food and garden organics without producing methane. The product returns nutrients to farms and gardens. But composting facilities are limited and struggling to cope with contamination from plastic.

We analysed the capacity of three wastewater facilities in Sydney to process organic wastes from surrounding households and businesses.

We found processing at the wastewater treatment plants could cut 33,000 tonnes of emissions and capture 9,600 tonnes of nutrients. All 14 wastewater facilities in Sydney could be modified to accept food waste, reducing emissions and producing renewable energy.

Why Process Food Waste At Wastewater Facilities?

Most wastewater facilities in Sydney use “anaerobic digestors” to treat sewage. Along with producing energy, this type of processing produces nutrient-rich biosolids that can be used for soil conditioning and as fertiliser.

Wastewater facilities are normally built with excess capacity to meet future demand and so could be used to handle food waste.

When the New South Wales government recently assessed the infrastructure needs to process food waste for the Greater Sydney Area by 2030, it identified an additional 260,000 tonnes per year of anaerobic digestion capacity is needed, on top of additional new composting infrastructure.

Currently, there is only one commercial anaerobic digestion plant in Sydney with a processing capacity of 52,000 tonnes per year.

Our study estimated just three wastewater facilities could fill 20% of the identified anaerobic digestion capacity gap required for Sydney by 2030.

Overseas, it is common for wastewater facilities to handle food waste, and in some cases generate more electricity than needed for their operation. These facilities give the excess electricity to the communities from which the food waste is collected and the nutrients back to local farms, creating a circular economy.

While industrial-scale composting facilities are normally located on the outskirts of Sydney, wastewater facilities are distributed throughout the city. This provides an additional benefit as food waste can be processed closer to where it is made, saving on significant transfer infrastructure and transport costs.

Although some changes are required to enable wastewater facilities to accept and process food waste, there are great returns on investment. As a recent economic study for Western Parkland City has shown, upgrading facilities brings wider economic benefits and creates jobs, along with the environmental benefits.

Separate Food Waste At The Source

To maximise anaerobic digestion at wastewater facilities, food waste needs to be separated from other wastes. This is because contamination and non-compatible materials in the waste stream can hinder the microbal processes driving anaerobic digestion.

NSW targets require all businesses making large amounts of food waste to separate it from other waste by 2025. Similarly, all households will need to separate food waste by 2030.

Currently most councils in Sydney offer a garden waste collection service. Only a few provide food waste collection and mostly in FOGO bins (combined Food Organics and Garden Organics waste service). However, the garden organics component of FOGO cannot be easily digested with sewage and would need significant additional pre-treatment before it can be processed.

Urban food organics are normally collected by trucks. This waste stream could potentially be piped to the wastewater treatment plant, with or without sewage. But piped networks were not considered for food waste collection in this study. It’s an interesting area for future research, especially in dense urban areas.

Achieving Net Zero Targets While Reducing Waste

The three wastewater facilities we studied could generate an estimated total of 38 billion litres of methane a year. This could replace the natural gas used by 30,000 households.

The bioenergy potential of the organic wastes from the study areas was estimated to be 126,000MWh. That is four and a half times more than the energy generated from solar panels installed in the area.

This study shows methane generated by anaerobic digestion can play an important role in the renewable energy mix. It can be used to generate electricity, as transport fuel, or as a natural gas replacement.

The wastewater facility at Malabar in Sydney is the first project in Australia injecting biogas into the gas network, demonstrating its feasibility.

The waste, energy and water sectors are all expected to achieve net zero targets. Reducing food waste and redirecting to more beneficial use works towards these targets.

Harnessing the full potential of anaerobic digestion of food waste at wastewater facilities will require collaboration between these sectors. But as we have shown, it will be worth it. ![]()

Melita Jazbec, Research Principal at the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology, Sydney, University of Technology Sydney; Andrea Turner, Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, and Ben Madden, Senior Research Consultant at the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Cooking (and heating) without gas: what are the impacts of shifting to all-electric homes?

Gas connections for all new housing and sub-divisions will be banned in Victoria from January 1 next year. The long-term result of the state government’s significant change to planning approvals will be all-electric housing. The ACT made similar changes early this year, in line with a shift away from gas across Europe and other locations, although the NSW Premier Chris Minns has baulked at doing the same.

Around 80% of homes in Victoria are connected to gas. This high uptake was driven by gas being seen as more affordable and sustainable than electricity over past decades. The situation has changed dramatically as renewable electricity generation increases and costs fall.

Research has suggested for more than a decade that the benefits of all-electric homes stack up in many locations. New homes built under mandatory building energy performance standards (increasing from 6 to 7 stars in Victoria in May 2024) need smaller, cheaper heating and cooling systems. Installing reverse-cycle air conditioning for cooling provides a cost-effective heater as a bonus.

Savings from not requiring gas pipes, appliances and gas supply infrastructure help to offset the costs of highly efficient electric appliances. Mandating fully electric homes means economies of scale will further reduce costs.

How Does This Ban Help?

To achieve environmentally sustainable development, reforms of planning policy and regulation are essential to convert innovation and best practice to mainstream practice. Planning policy is particularly important for apartment buildings and other housing that may be rented or have an owners’ corporation. Retrofits to improve energy efficiency can be difficult in these situations.

Banning gas in new and renovated housing will cut greenhouse gas emissions. It’s also healthier for households and reduces healthcare costs as well as energy bills and infrastructure costs. The Victorian government suggests the change will save all-electric households about $1,000 a year. Houses with solar will be even better off.

The government appears to be offering wide support to ensure these changes happen, but this will need to be monitored closely.

Some households will face extra costs for electric appliances and solar panels. The government’s announcement of $10 million for Residential Electrification Grants should help with some of these costs while the industry adjusts.

There will be impacts and benefits for the local economy. Some jobs may be lost, particularly in the gas appliance and plumbing industry. The government has announced financial support to retrain people and they will still have essential roles in the existing housing sector.

Many gas appliances are imported, including ovens, cooktops and instantaneous gas water heaters. Some components of efficient electric products, such as hot water storage tanks, are made locally. Local activities, including distribution, sales, design, installation and maintenance, comprise much of the overall cost.

Challenges Of Change Must Be Managed

Sustainability benefits will depend on what happens with the energy network. We need more renewable energy, energy storage and smarter management of electricity demand.

The shift to all-electric homes may mean winter peak demand for heating increases. Energy market operators and governments will have to monitor demand changes carefully to avoid the reliability issues we already see in summer. However, improving energy efficiency, energy storage and demand management will help reduce this load (and household costs).

While the benefits are clear for new homes, the changes may increase gas costs and energy poverty for residents of existing housing who don’t shift to efficient electric solutions. The government has reconfirmed financial rebates to help households switch from gas.

In addition, existing housing may face building quality and performance issues. Some may require electrical wiring upgrades as part of the transition.

Social acceptance of some electric appliances may also be an issue. For example, our research has found some households dislike the way heating from reverse cycle air conditioners feels. Others do not like cooking on induction cooktops.

Consumer education and modifications to appliances and buildings may be needed to increase acceptance and avoid backlash.

Some electric appliances are available overseas but not in Australia. Higher demand may increase the range of imports. For example, floor-mounted heat pumps can make heating feel similar to gas heating while still providing effective cooling.

We should not assume electric appliances are all equal. To improve consumer protection, action is needed on weak standards and limited and inconsistent public information. For example, information on noise levels and efficiency under a range of weather conditions must be standardised.

Moving housing away from gas is an important step in the transition to a zero-carbon economy and energy system. Careful management is needed to ensure this transition is effective, accepted and fair.

Continued planning reforms are also essential to ensure environmentally sustainable development of housing and communities. Other urgent priorities include urban cooling and greening, and circular economy approaches to reduce the material and waste impacts of housing and thus the carbon that goes into building and running homes.![]()

Trivess Moore, Senior Lecturer, School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University; Alan Pears, Senior Industry Fellow, RMIT University, and Joe Hurley, Associate Professor, Sustainability and Urban Planning, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

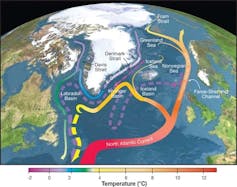

The ‘Gulf Stream’ will not collapse in 2025: What the alarmist headlines got wrong

Those following the latest developments in climate science would have been stunned by the jaw-dropping headlines last week proclaiming the “Gulf Stream could collapse as early as 2025, study suggests” — which responded to a recent publication in Nature Communications.

“Be very worried: Gulf Stream collapse could spark global chaos by 2025” announced the New York Post. “A crucial system of ocean currents is heading for a collapse that ‘would affect every person on the planet” noted CNN in the U.S. and repeated CTV News here in Canada.

One can only imagine how those already stricken with climate anxiety internalized this seemingly apocalyptic news as temperature records were being shattered across the globe.

This latest alarmist rhetoric provides a textbook example of how not to communicate climate science. These headlines do nothing to raise public awareness, let alone influence public policy to support climate solutions.

We See The World We Describe

It is well known that climate anxiety is fuelled by media messaging about the looming climate crisis. This is causing many to simply shut down and give up — believing we are all doomed and there is nothing anyone can do about it.

Alarmist media framing of impending doom has become quintessential fuel for personal climate anxiety, and when amplified by sensational media messaging, it is quickly emerging as a dominant factor in the collective zeitgeist of our age, the Anthropocene.

This is also not the first time such headlines have emerged. Back in 1998, the Atlantic Monthly published an article raising the alarm that global “warming could lead, paradoxically, to drastic cooling — a catastrophe that could threaten the survival of civilization.”

In 2002, editorials in the New York Times and Discover magazine offered the prediction of a forthcoming collapse of deep water formation in the North Atlantic, which would lead to the next ice age.

Building on the unfounded assertions in these earlier stories, BBC Horizon televised a 2003 documentary entitled The Big Chill, and in 2004 Fortune magazine published “The Pentagon’s Weather Nightmare,” piling on where previous articles left off.

Seeing the opportunity for an exciting disaster movie, Hollywood stepped up to created The Day After Tomorrow in which every known law of thermodynamics was ever so creatively violated.

The Currents Are Not Collapsing (Anytime Soon)

While it was relatively easy to show that it is not possible for global warming to cause an ice age, this still hasn’t stopped some from promoting this false narrative.

The latest series of alarmist headlines may not have fixated on an impending ice age, but they still suggest the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation could collapse by 2025. This is an outrageous claim at best and a completely irresponsible pronouncement at worst.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has been assessing the likelihood of a cessation of deep-water formation in the North Atlantic for decades. In fact, I was on the writing team of the 2007 4th Assessment Report where we concluded that:

“It is very likely that the Atlantic Ocean Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC) will slow down during the course of the 21st century. It is very unlikely that the MOC will undergo a large abrupt transition during the course of the 21st century.”

Almost identical statements were included in the 5th Assessment Report in 2013 and the 6th Assessment Report in 2021. Other assessments, including the National Academy of Sciences Abrupt Impacts of Climate Change: Anticipating Surprises, published in 2013, also reached similar conclusions.

The 6th assessment report went further to conclude that:

“There is no observational evidence of a trend in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), based on the decade-long record of the complete AMOC and longer records of individual AMOC components.”

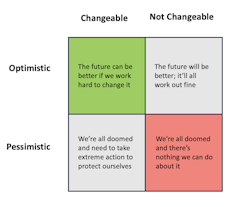

Understanding Climate Optimism

Hannah Ritchie, the deputy editor and lead researcher at Our World in Data and a senior researcher at the Oxford Martin School, recently penned an article for Vox where she proposed an elegant framework for how people see the world and their ability to facilitate change.

Ritchie’s framework lumped people into four general categories based on combinations of those who are optimistic and those who are pessimistic about the future, as well as those who believe and those who don’t believe that we have agency to shape the future based on today’s decisions and actions.

Ritchie persuasively argued that more people located in the green “optimistic and changeable” box are what is needed to advance climate solutions. Those positioned elsewhere are not effective in advancing such solutions.

More importantly, rather than instilling a sense of optimism that global warming is a solvable problem, the extreme behaviour (fear mongering or civil disobedience) of the “pessimistic changeable” group (such as many within the Extinction Rebellion movement), often does nothing more than drive the public towards the “pessimistic not changeable” group.

A Responsibility To Communicate, Responsibly

Unfortunately, extremely low probability, and often poorly understood tipping point scenarios, often end up being misinterpreted as likely and imminent climate events.

In many cases, the nuances of scientific uncertainty, particularly around the differences between hypothesis posing and hypothesis testing, are lost on the lay reader when a study goes viral across social media. This is only amplified in situations where scientists make statements where creative licence is taken with speculative possibilities. Possibilities that reader-starved journalists are only too happy to play up in clickbait headlines.

Through independent research and the writing of IPCC reports, the climate science community operates from a position of privilege in the public discourse of climate change science, its impacts and solutions.

Climate scientists have agency in the advancement of climate solutions, and with that agency comes a responsibility to avoid sensationalism. By not tempering their speech, they risk further ratcheting up the rhetoric with nothing to offer in terms of overall solutions or risk reduction.![]()

Andrew Weaver, Professor, School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Olympic swimming in the Seine highlights efforts to clean up city rivers worldwide

Gary Osmond, The University of Queensland and Rebecca Olive, RMIT UniversityOne year out from the 2024 Summer Olympic and Paralympic games, Paris has announced it will reopen the River Seine for swimming competition and then allow public swimming, ending a century-long ban. This ban was in place to stop people immersing themselves in river waters polluted by stormwater, sewage and chemicals.

But after many years of stormwater management work, three Olympic and Paralympic events will be held in the Seine in 2024 – the swimming marathon and the swimming legs of the Olympic triathlon and Para-triathlon. The Seine will also feature in the opening ceremony when, instead of the traditional athletes’ parade in a stadium, a parade of boats will carry the teams along the river.

The clean waters of the swimmable Seine are being promoted as a positive legacy of these games. But it’s not the first time Olympic swimming events have been held in the famous river. And with growing commitments to swimmable cities around the world, it is unlikely to be the last.

A Brief History Of River Swimming

At the 1900 Paris Olympics, Australia’s Freddie Lane won two swimming events in the Seine. These were the 200 metres freestyle and a 200m obstacle race. This unusual event required the 12 athletes from four countries to climb over a pole, scramble over a row of boats and then swim under another row of boats.

Historians Reet and Max Howell quoted Lane describing his winning strategy: “[Knowing] a bit about boats [I] went over the sterns […] unlike the majority of competitors who fought their way over the sides.”

Following the tradition of linking to classical history that was common in the Games at the time, this event referenced Sequana, the Gallo-Roman goddess of the Seine. She is typically represented standing on a boat: clambering over and swimming under the river’s vessels was clearly for mere mortals.

That was the first and only time the Olympics included an obstacle race. But swimming competitions at the time were often held in rivers, harbours, lakes and other natural water bodies. The swimming races at the first modern Olympics, in Athens in 1896, were held in the Bay of Zea on the Piraeus peninsula. It wasn’t until 1908 in London that swimming moved to landlocked pools.

Swimming in rivers has a very long history related to pleasure and politics. Competitive river swimming remained common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Freddie Lane won the New South Wales mile championship in the Murrumbidgee River at Wagga Wagga in January 1899.

“Professor of swimming” Fred Cavill helped pioneer swimming lessons for the masses in Sydney – including girls and women. He gave promotional swims in the Murray River on his arrival from the United Kingdom in 1880. Later that year he had to abandon a much-touted river swim from Parramatta to Sydney due to strong tides. One of Cavill’s sons, Arthur “Tums” Cavill, emigrated from Sydney to the United States where he introduced an annual winter swim in the Willamette River in Portland, Oregon, in 1909.

And while it wasn’t an Olympic feat, in 1918 Alick Wickham made a world record high dive of 205 feet 9 inches (62.7 metres) into the Yarra River in Melbourne.

Even Chinese leader Mao Zedong used river swimming to promote his health and political image.

More recently, the swim leg of the triathlon for the 2000 Olympic Games was held in Sydney Harbour, where divers were on shark patrol.

However, like the 1900 obstacle race, organised and informal river swimming in cities became uncommon. In rivers such as the Seine in Paris and parts of the Yarra in Melbourne, it was even illegal.

The rise of built pools contributed to this shift, and for good reason. The novelty and modern design of concrete pools might have been part of the reason people abandoned city rivers and natural waterways. However, these new facilities also offered safety from sharks and stormwater, bacteria, chemicals and pollutants. Admittedly, questions of hygiene have also swirled around pools, especially before chlorine was added.

Ocean baths and pools served a similar purpose. As regulated spaces managed by local governments, pools meant swimmers were safer: lifeguards could watch over them and swimmers had access to more discreet changing facilities.

The Quest For Swimmable Cities

Pools have remained popular, but river swimming never disappeared. In recent years, a resurgence in interest has been buoyed by the environmental movement’s efforts to rehabilitate waterways and growing research supporting the health benefits of outdoor swimming.

The Seine will reopen for swimming thanks to a €1.4 billion (A$2.3 billion) regeneration project to “reinvent the Seine”. It began in 2017 and includes floating hotels, walkways and other social spaces as well as swimming and diving areas.

The revival of swimming in the Seine is just one example of how outdoor and “wild” swimming is contributing to better caring for rivers. In England, there’s pressure to improve the water of the River Thames in London as well as broader movements to stop sewage outfalls on rivers. In Denmark, Copenhagen harbour has summer swimming sites. In Beijing there is a somewhat subversive outdoor swimming subculture.

In Australia, too, a number of new swimming sites have opened. In Sydney, sites along the Parramatta River and in the harbour – one spot at Barangaroo opened this year – complement established river and harbour swimming areas, including the famous Dawn Fraser Baths. In Melbourne, there are calls for a chain of city swimming spots along the Birrarung/Yarra.

The growth in awareness of the important role that blue spaces – oceans, rivers, lakes, canals and other waterways – play in human health and wellbeing comes alongside a revival of the popularity of outdoor swimming and immersion. While we know this is good for people, public interest in clean, swimmable waterways for our own health, wellbeing and pleasure can also have great benefits for these environments.![]()

Gary Osmond, Associate Professor of Sport History, The University of Queensland and Rebecca Olive, Vice Chancellor's Senior Research Fellow, Social and Global Studies Centre, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Do phrases like ‘global boiling’ help or hinder climate action?

Last week, United Nations General Secretary António Guterres coined an arresting new term. The era of global warming has ended, he declared dramatically, and the era of “global boiling” has arrived.

You can see why he said it. July was the hottest month on record globally. Searing temperatures and intense wildfires have raged across the Northern Hemisphere. Marine heatwaves are devastating the world’s third-largest coral reef, off Florida. And as greenhouse emissions keep rising, it means many even hotter summers await us.

But critics and climate sceptics have heaped scorn on the phrase. Taken literally, they’re correct – nowhere on Earth is near the boiling point of water.

Is Guterres’ phrase hyperbolic or an accurate warning? Do phrases like this actually help drive us towards faster and more effective climate action? Or do they risk making us prone to climate doomism, and risk prompting a backlash?

Rhetoric And Reality

Guterres is rhetorically adept. He uses the moral authority of his position to vividly depict the climate crisis. For instance, he told attendees at last year’s COP27 climate summit in Egypt we are on “a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator”. In many ways, it’s one of the only tools he has, given the UN has global influence but limited real power.

“Global boiling” ups the verbal ante. It’s designed to sound the alarm and trigger more radical action to stave off the worst of climate change.

Guterres chooses his words carefully. But does he choose them wisely?

At one level, “global boiling” is clearly an exaggeration, despite the extreme summer heat and fire during the northern summer.

But then again, “global warming” is now far too tame a descriptor. Prominent climate scientists have pushed for the term “global heating” to be used in preference.

Similarly, phrases such as “the climate crisis” haven’t gained traction with either elites or the ordinary public. That’s because many of us still feel we haven’t seen this crisis with our own eyes.

But that is changing. In the past few years, extreme weather and related events have struck many countries – even those who may have thought themselves immune. Australia’s Black Summer brought bushfires that burned an area the size of the United Kingdom. Germany suffered lethal flooding in 2021. The unprecedented 2022 deluge in Pakistan flooded large tracts of the country. China has seen both drought and floods. Savage multi-year droughts have hit the Horn of Africa. India has banned rice exports due to damage from heavy rain.

Once-abstract phrases are now having real-world purchase – in developed and developing nations alike.

Climate scepticism has also dropped away. Fewer doubters are trying to discredit the fundamental science than during the long period of manufactured scepticism in Western nations.

In this context, we can see “global boiling” as an expression of humanitarian concern backed by rigorous science showing the situation continues to worsen.

The Hazards Of Theatrical Language

There are risks in warning of catastrophe. People who don’t pay close attention to the news may switch off if the predicted disaster doesn’t eventuate. Or the warnings can add to climate anxiety and make people feel there’s no hope and therefore no point in acting.

There’s another risk, too. Catastrophic language often has moral overtones – and, as we all know, we don’t like being told what to do. When we hear a phrase like “global boiling” in the context of a prominent official exhorting us to do more, faster, it can raise the hackles.

You can see this in the emerging greenlash, whereby populist-right figures scorn solar and wind farms. Even struggling mainstream leaders like UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak can pivot this way, as evidenced by his recent positioning as pro-car and pro-oil extraction.

Opponents of climate action – who tend to be on the right of politics – often complain about what they see as the overuse of “crisis talk”. If everything is a crisis, nothing is a crisis. This view has some merit.