inbox and environment news: Issue 595

August 20 - 26, 2023: Issue 595

The Powerful Owl Project: It’s Fledging Time!

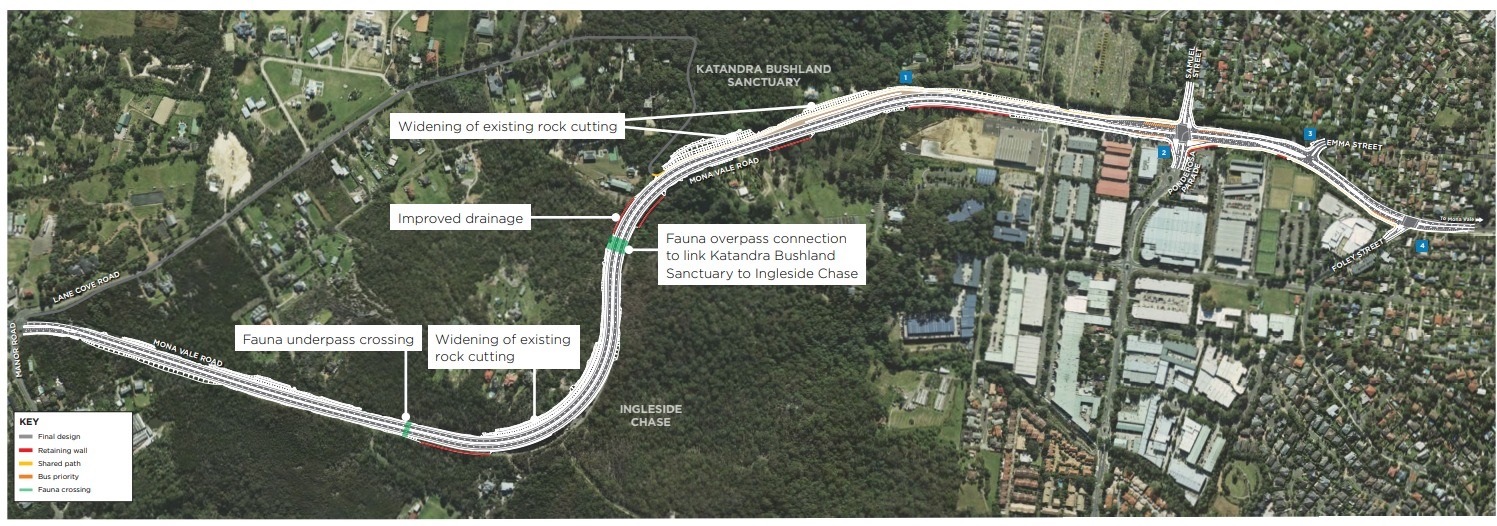

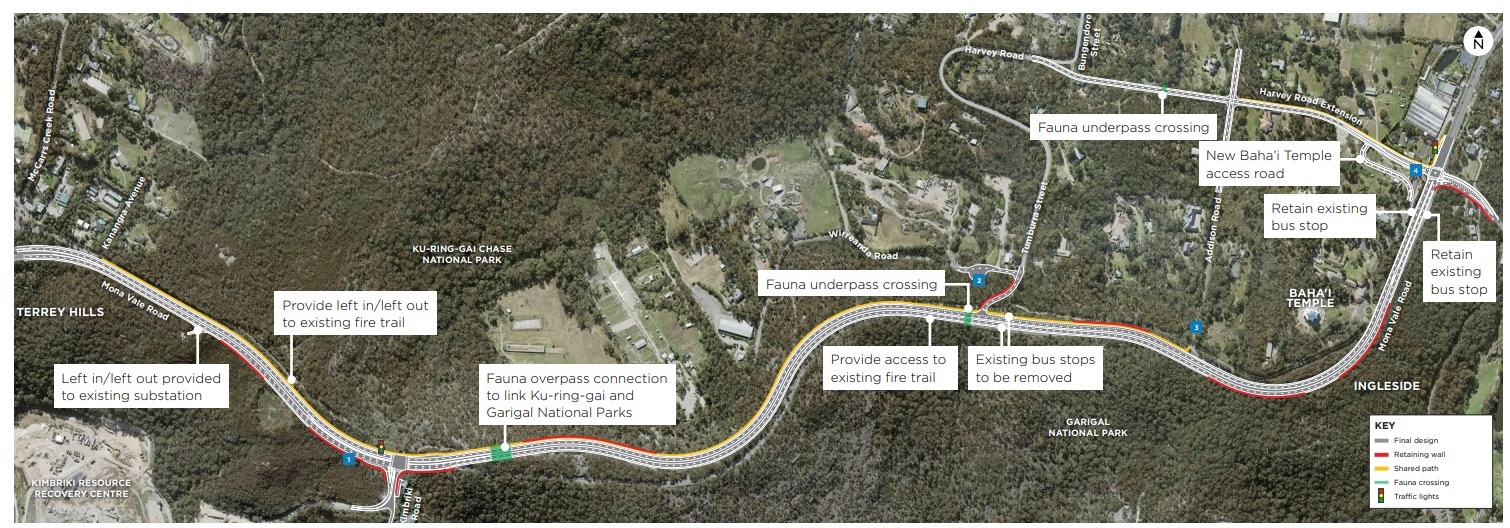

Mona Vale Road (East) Upgrade: Fauna Bridge Supports Installed

- safely install the fauna bridge supports

- minimise traffic disruptions

- reduce safety risks to workers and motorists.

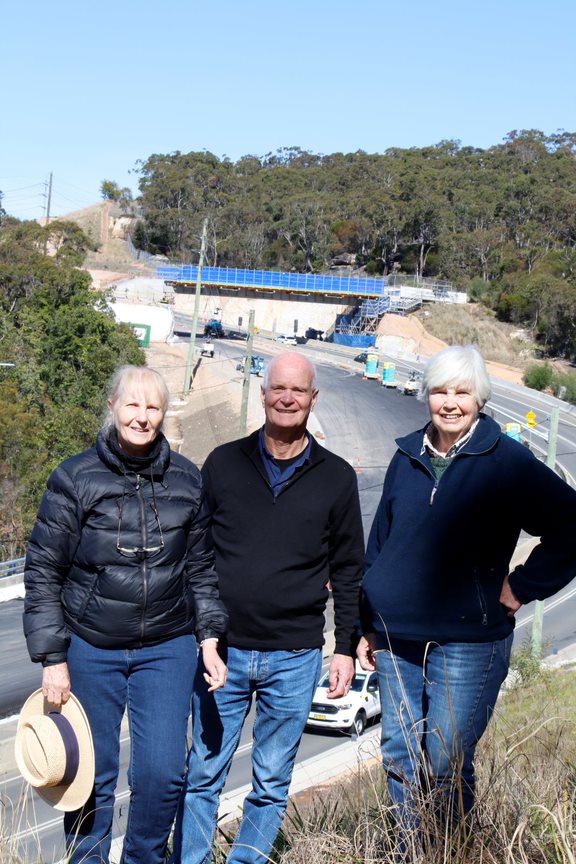

Photo: David Palmer, Jacqui Marlow and Marita Macrae celebrate the June 2019 announcement of a fauna bridge to be built over Mona Vale Rd East.

Photo: August 19 2023 - Jacqui Marlow, David Palmer and Marita Macrae celebrate the installation of the MVR East Upgrade fauna bridge supports.

The Wildlife Roadkill Prevention Association aims to reduce the roadkill of native animals on the Northern Beaches of Sydney, Australia. In 2005, the association was formed to address wildlife roadkill and raise awareness of broader conservation issues for our area.

The Pittwater Natural Heritage Association was formed to act to protect and preserve the Pittwater areas major and most valuable asset - its natural heritage.

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association seeks to raise awareness and provide information and advice to members on issues such as:

Native Tree Canopy

Identification of trees local to your particular area. What to plant to replace dead or dying trees, and how to care for trees. The characteristic form of the native tree canopy is a major contributor to Pittwater's sense of place.

"Bush Friendly" Gardens

Selecting plants for your garden that will live in harmony with nearby bushland and provide habitat for native animals and birds.

Building and Landscaping

Promoting practices which preserve and protect the visual qualities of the landform, preserve soil stability and prevent erosion of steep slopes and siltation of waterways.

Weed Infestation

Information on noxious and environmental weeds, weed identification and methods of control and eradication.

Living with Wildlife

Maintaining habitat and wildlife corridors for our rich and diverse native fauna. Understanding the impacts of introduced birds and animals and uncontrolled domestic pets.

Keeping our Waterways Healthy

Using and enjoying our waterways and estuaries whilst maintaining appropriate water quality and habitat for aquatic creatures. Caring for the streams, wetlands, saltmarsh and mangrove systems that are an integral part of our waterways.

Rock Platforms, Beaches and Dunes

Protecting and preserving the plant and animal communities on rock platforms. Restoration and regeneration of dune systems and maintenance of their stability.

Find out more and become a member at: https://pnha.org.au

Above and below: how the fauna overpass looks now. Photos supplied.

Mother And Calf Southern Right Whales Expected To Take A Breather In Sydney Harbour This Weekend: Please Stay Away From Them

Sydneysiders may be welcoming 2 very rare and special visitors this weekend as the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) waits to see if a mother-calf pair of Southern Right Whales will stop in for a rest in Sydney Harbour over coming days.

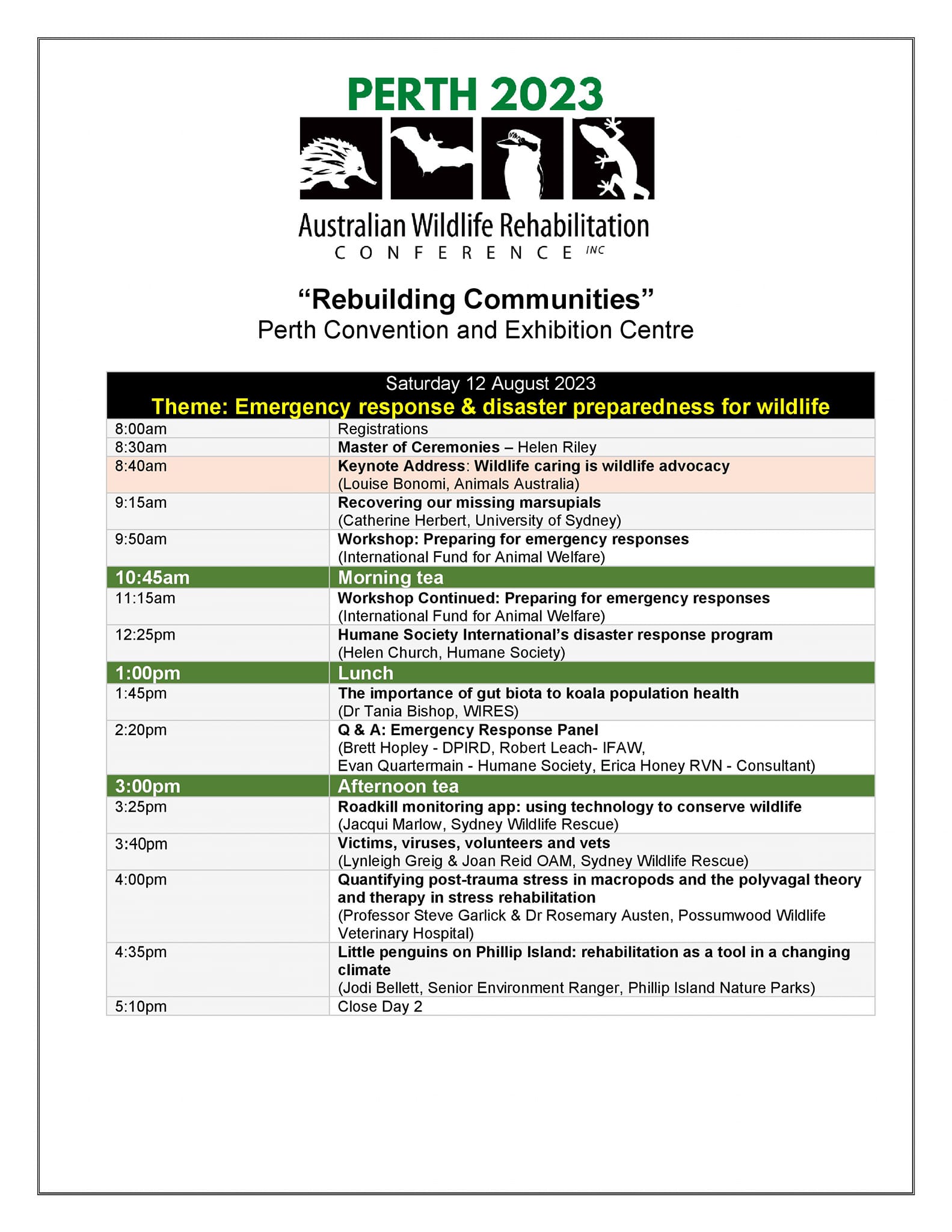

Sydneysiders may be welcoming 2 very rare and special visitors this weekend as the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) waits to see if a mother-calf pair of Southern Right Whales will stop in for a rest in Sydney Harbour over coming days.Australian Wildlife Rehabilitation Conference 2023: Local Papers Presented

- Encourage and facilitate the organisation of regular national wildlife rehabilitation conferences around Australia

- Provide if requested, operational support to conference organising committees + Administer conference funds, including the interest-free "rolling loan" to conference organising committees

- Maintain the conference website between conferences, and disseminate conference information through the website

Joan Reid and Lynleigh Greig

Jacqui Marlow repairing wildlife exclusion fencing on Wakehurst Parkway

Saving Native Species Grants

- 22 Birds

- 21 Mammals

- 9 Fish

- 6 Frogs

- 11 Reptiles

- 11 Invertebrates

- 30 Plants

Invitation For Public Comment: Mt Gilead Stage 2 Residential Development, Gilead, NSW (EPBC 2019/8587)

- Click here to download – EPBC 2019_8587 Mt Gilead Stage 2 Preliminary Documentation_AdequacyAssessment_Ver 3_20230720

- Click here to download – Appendix A_2019-8587 Referral

- Click here to download – Appendix B_EPBC 2019_8587 Decision notice 24FEB2020

- Click here to download – Appendix C_EPBC 2019_8587 PD Requirements_24FEB2020

- Click here to download – Appendix E_Lendlease SustainabilityPolicy

- Click here to download – Appendix F_cam-sustainability-framework-full-1

- Click here to download – Appendix G_ Australia-mission-zero-roadmap-summary

- Click here to download – Appendix H_MtGilead Stage2_Biocert_v8_20230718

- Click here to download – Appendix I_Draft Response Principles for Koala Protection in the Greater Macarthur and Wilton Growth Areas

- Click here to download – Appendix J_DPE Methodology to calculate Koala corridor widths

- Click here to download – Appendix K1_DPE Letter to Lendlease re Koala corridors – Dec 2021

- Click here to download – Appendix K2_DPE Indicative koala corridor map Gilead

- Click here to download – Appendix L_Koala_Conservation_at_Gilead_Lendlease 2022

- Click here to download – Appendix M_ Mount Gilead Stage 2 Koala Plan of Mgnt v4_20230720

- Click here to download – Appendix N_Mount Gilead Stage 2 EPBC CEMP V5_20230720_signed

- Click here to download – Appendix O – PMST Search – 2 February 2023

- Click here to download – Appendix P_EPBC Likelihood tables_v3-02022023

- Click here to download – Appendix Q_Koala Drone surveys Figtree Hill_Wild Conservation 2021

- Click here to download – Appendix R_Koala Drone Surveys Figtree Hill_Wild Conservation 2022

- Click here to download – Appendix S_PlotData_EPBCondition_20191009

- Click here to download – Appendix T_Flora Species List from plot data

- Click here to download – Appendix U_Naturalised Stormwater Strategy for Gilead_E2 Designs

- Click here to download – Appendix V_BioBankingCreditSummaryReport_Development_20230626

- Click here to download – Appendix W_BioBankingCreditSummaryReport_BiobankSite_20230626

- Click here to download – Gilead EPBC offset_CPW Step 1_Cond C_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead EPBC offset_CPW Step 2_Cond A_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead EPBC Offset_GHFF_Large-eared Pied Bat Offset Calculations_existing_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead EPBC Offset_GHFF_Large-eared Pied Bat Offset Calculations_restored_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead EPBC offset_Pomaderris_Vul_Ver 3_20220628

- Click here to download – Gilead EPBC offset_RFEF Step 1_Cond C_Ver 2_10112022

- Click here to download – Gilead EPBC offset_SSTF Step 1_ Cond A_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead EPBC offset_SSTF Step 2_ Cond B_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead EPBC offset_SSTF Step 3_Cond D_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead_Koala Offset Calculations_Endangered_existing_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead_Koala Offset Calculations_Endangered_restored_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead_Koala Offset Calculations_Vulnerable_existing_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead_Koala Offset Calculations_Vulnerable_restored_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead_Quoll Offset Calculations_Vulnerable_existing_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead_Quoll Offset Calculations_Vulnerable_restored_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead_Quoll Offset Calculations_Vulnerable_Ver 2_10112022

- Click here to download – Gilead_Swift Parrot Offset Calculations_existing_CE_Ver 3_20230628

- Click here to download – Gilead_Swift Parrot Offset Calculations_restored_CE_Ver 3_20230628

Time Of Wiritjiribin

August

Female Lyre bird - Elanora Heights

Photo by Selena Griffith, May 29 2023

Selena says ''this one followed me along the path. Never been so close.''

Bushcare Training Day At North Narrabeen

- Weed identification and best practice removal techniques

- Native plant identification and weed species including lookalikes

- Hands-on weed removal

- Bring along your unknown plant species for identification

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group Begins

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

2023 Banksia Foundation NSW Sustainability Awards Open For Nominations

Pittwater Garage Sale Trail Returns: Repurpose Your Items

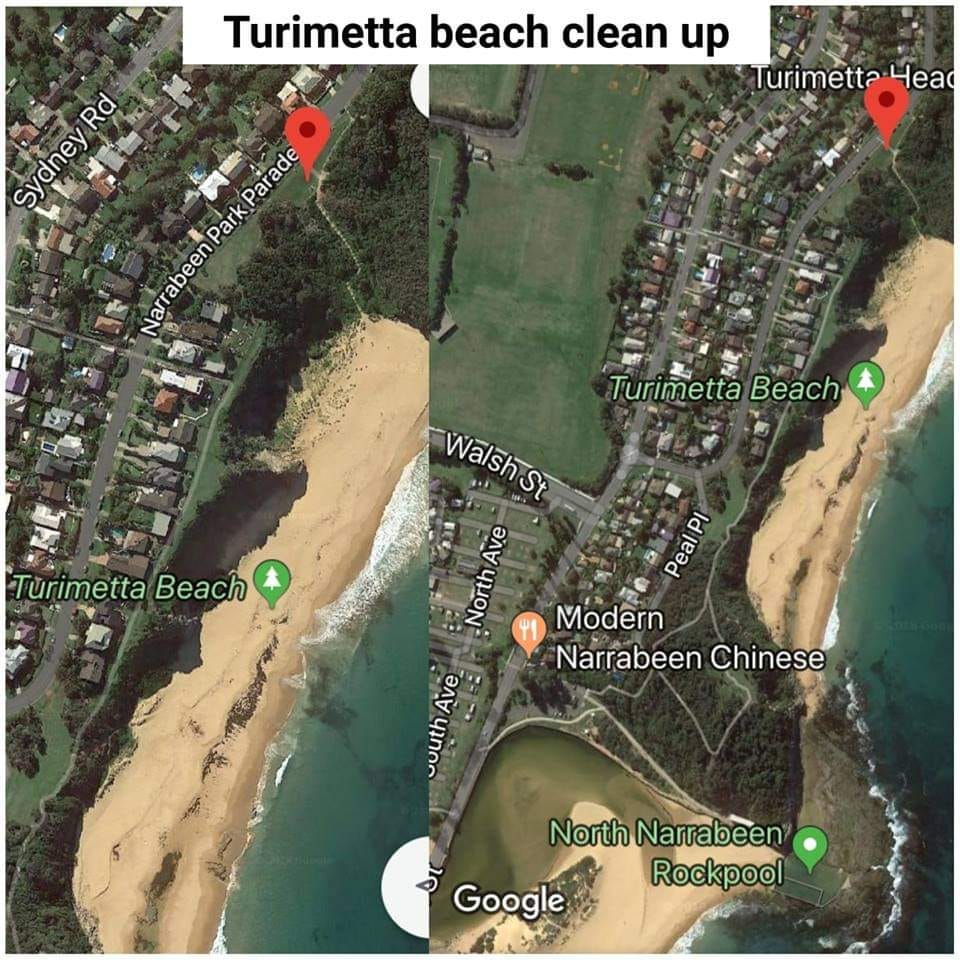

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Sunday August 27 2023 From 10:00-12:15 - Turimetta Beach Clean Up

Waste And Sustainability In Schools NR37040: At Kimbriki

Stony Range Spring Festival 2023: Sunday September 10

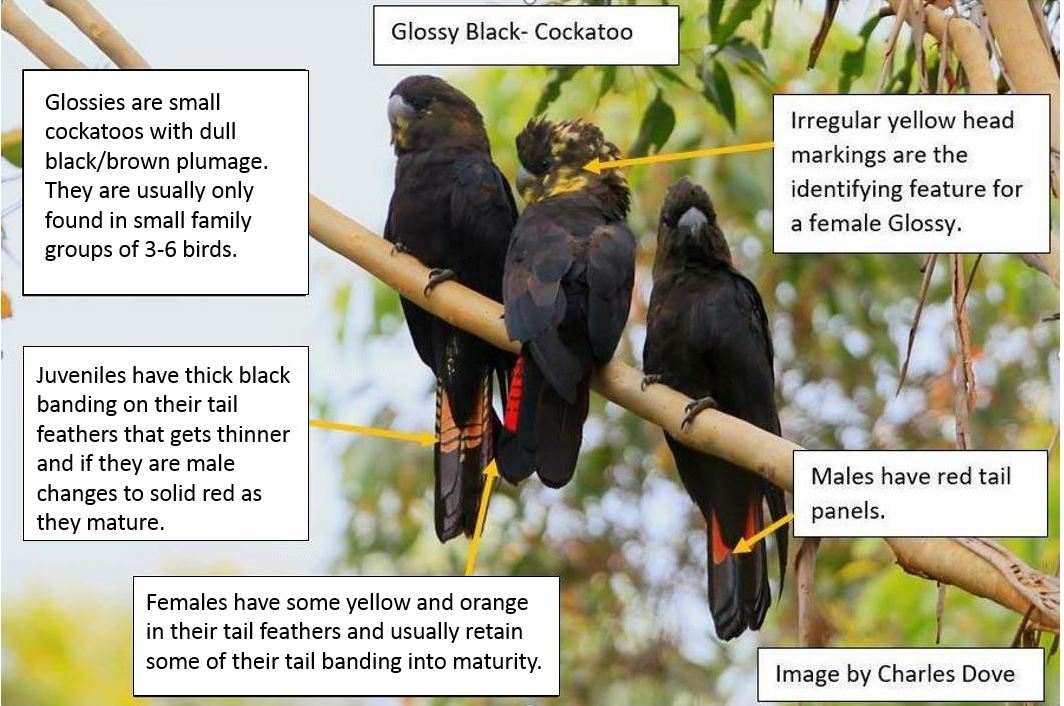

Seen Any Glossies Drinking Around Nambucca, Bellingen, Coffs Or Clarence? Want To Help?: Join The Glossy Squad

- a female bird (identifiable by yellow on her head) begging and/or being fed by a male (with plain black/brown head and body and unbarred red tail feathers)

- a lone adult male, or a male with a begging female, flying purposefully after drinking at the end of the day.

Department Of Planning And Environment To Become Two New Departments From January 1st 2024

Rising River Alert – Snowy River Below Jindabyne Dam

More Councils To Recycle Food And Garden Waste

$850,000 In Funding Open To Improve Fish Habitat

- removal or modification of barriers to fish passage

- rehabilitation of riparian lands (riverbanks, wetlands, mangrove forests, saltmarsh)

- re-snagging waterways with timber structure

- the removal of exotic vegetation from waterways and replacement with native plants

- bank stabilisation works

- fencing to exclude livestock.

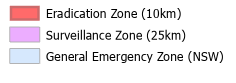

Alcohol Washing Confirms New Varroa Detection Near Kempsey

- Ensure they are registered

- Not move hives from their current location

- Report the location of those hives to NSW DPI

- Undertake mandatory alcohol washes on their hives at least every 16-weeks and report the results to NSW DPI within 7 days.

Blue Mountains National Park And Kanangra-Boyd National Park Draft Plan Of Management: Public Consultation

- improving recognition of the parks significant values, including World and National Heritage values, and providing for adaptive management to protect the values

- recognising and supporting the continuation of partnerships with Aboriginal communities

- providing outstanding nature-based experiences for visitors through improvements to visitor facilities - including:

- Opportunities for supported or serviced camping, where tents and services are provided by commercial tour operators, may be offered at some camping areas in the parks

- Jamison Creek, Jamison Valley Walk-in camping Potential new camping

- Leura Amphitheatre Jamison Valley Walk-in camping Potential new camping

- Mount Solitary Jamison Valley Walk-in camping Potential new camping

- Maxwell’s HuC Kedumba Valley Cabin/hut Potential new accommodation

- Kedumba Valley Maxwell’s Hut (historic slab hut) - Building restoration in progress; potential new Accommodation for bushwalkers

- Government Town Police station; courthouse - Potential new Visitor accommodation

- write clearly and be specific about the issues that are of concern to you

- note which part or section of the document your comments relate to

- give reasoning in support of your points - this makes it easier for us to consider your ideas and will help avoid misinterpretation

- tell us specifically what you agree/disagree with and why you agree or disagree

- suggest solutions or alternatives to managing the issue if you can.

Plans For New Wind Energy Project At Spicers Creek On Public Exhibition

Nauseous Territory: Outfoxing Predators Using Baits That Make Them Barf

Introduced foxes, dogs, cats, rats, and other predators kill millions of native animals every year, but what if they were conditioned to associate this prey with food that made them ill?

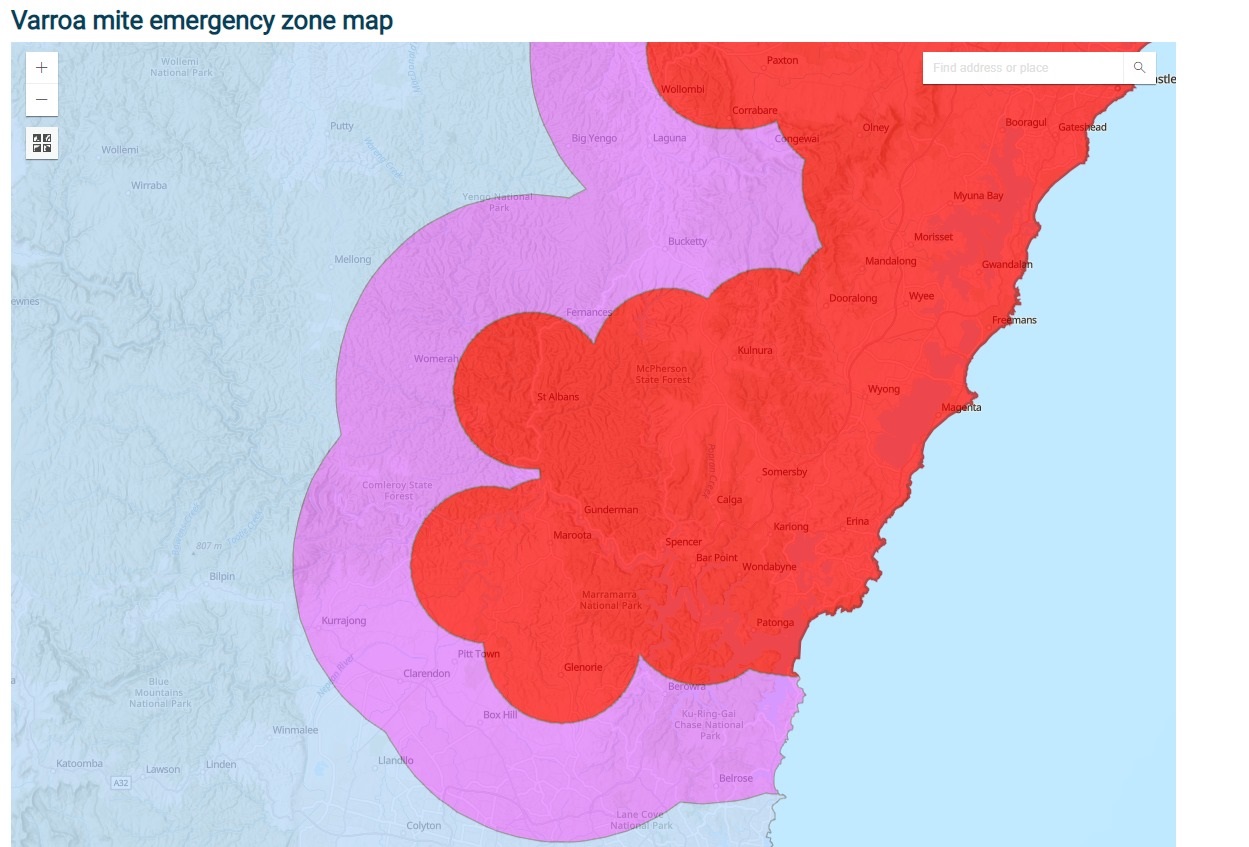

Introduced foxes, dogs, cats, rats, and other predators kill millions of native animals every year, but what if they were conditioned to associate this prey with food that made them ill?Areas Closed For West Head Lookout Upgrades

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

- West Head lookout

- The loop section of West Head Road

- West Head Army track.

Vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians will have access to the Resolute picnic area and public toilets. Access is restricted past this point.

The following walking tracks remain open:

- Red Hands track

- Aboriginal Heritage track

- Resolute track, including access to Resolute Beach and West Head Beach

- Mackeral Beach track

- Koolewong track.

The West Head lookout cannot be accessed from any of these tracks.

Image: Visualisation of upcoming works, looking east from the ramp towards Barrenjoey Head Credit: DPE

Bush Turkeys: Backyard Buddies Breeding Time Commences In August - BIG Tick Eaters - Ringtail Posse Insights

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

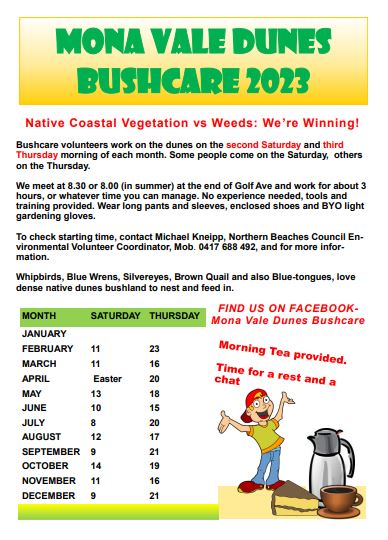

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Trapped: Australia’s extraordinary alpine insects are being marooned on mountaintops as the world warms

We may not pay invertebrates much thought, but they’re the workhorses of all ecosystems. Insects and other invertebrates do essential jobs such as pollinating plants, improving soils and controlling pests. They’re also food for many larger animals, which moves nutrients up the food chain.

Invertebrates are vulnerable to rising global temperatures. In response to climate change, many are moving to cooler areas, be that across land towards the poles, or upward in elevation.

But not all invertebrates have that option. In Australia, invertebrates already living at the highest possible elevation – on mountain summits – have nowhere higher to go. So how will they cope? And how can we help them?

Answering these questions is important. Invertebrates underpin Earth’s ecosystems – so if their numbers decline, the ecological damage will be felt far and wide.

A Life At The Top

The invertebrates of the Australian Alps are beautiful and diverse. As in all ecosystems, they make up the largest proportion of our alpine animal species.

Most of our alpine invertebrates are found nowhere else If we don’t look after them they’re gone forever. And each species extinction is like losing a rivet in an aeroplane wing; eventually whole ecosystems will crash.

Warmer temperatures can affect invertebrates in many ways. For example, pollinating insects that collect nectar may hatch before plants flower – creating issues for both the insects and the plants. Species that rely on wet or damp conditions may find their habitat dried out. Less harsh, cold conditions may also bring new predators and competitors into their habitats.

Overseas, where mountain ranges are typically much higher, animals have been moving up in elevation to survive. But Australia’s mountains are small – less than half the height of many key mountain ranges overseas. This leaves little room to move higher.

Alpine invertebrates tend to live in small, isolated populations on mountain tops. This limits their genetic diversity and therefore the potential that offspring can survive and adapt to changing conditions.

What’s more, many invertebrates don’t have wings, so can’t fly away to a more hospitable place. And being trapped on mountain tops also makes them vulnerable to devastating local threats such as unusually severe or extensive bushfires.

Extraordinary Bogong Moths

Some species might seem to be moving higher up the Australian Alps. For example, it seems bogong moths inhabit low elevation caves less frequently than they once did. But this probably just shows the species’ habitat is shrinking upward.

Each year, bogong moths undertake an extraordinary nocturnal migration. From their starting point many hundreds of kilometres away, they use the stars and Earth’s magnetic field to navigate to the Australian Alps in search of cool caves and rock crevices. There, they rest and take refuge from the summer heat, before returning to their winter pastures.

In 2021, bogong moths were listed as endangered because the availability of their summer habitat is declining.

Bogong moths bring an incredibly important influx of nutrients to the alps. They provide food for many animals, including the adorable, critically endangered mountain pygmy possum, as well as many types of birds.

The Taungurung people refer to the bogong moth as “Deberra”. The annual concentration of Deberra in the alps is culturally significant to the Taungurung and other traditional custodians.

Deberra have a high fat content and were harvested by Taungurung and other groups for eating. During the harvest, large gatherings of many Aboriginal nations were held and cultural business was conducted.

So Deberra offers not only a rich source of food, but also connection with deeply significant cultural landscapes. They are an important element in the cyclical movement of people and exchange of knowledge within and between Indigenous nations.

For Traditional Owners, Deberra is, like all things, part of the interrelated web of Country. When Deberra travels, human and non-human entities follow. It supports energy flows of many kinds.

The decline of Deberra is a sign that Country is sick. Sick Country tells us the land is not being managed well.

Colour-Changing Skyhoppers

The adults of many alpine invertebrate species live for just a single summer, lay their eggs, then die. They include skyhoppers, a group of alpine grasshoppers unique to Australia, many species of which are threatened.

Skyhoppers rely on a thick snow layer to protect their eggs in winter. But Australia’s snow cover is becoming increasingly unreliable as the planet warms.

Thermocolour skyhoppers, listed as endangered, are unique among grasshoppers in that they change colour from black to turquoise when their body temperature exceeds 25℃.

Until recently, five skyhopper species were known to science. But when researchers walked the entire 655-kilometre Australian Alps walking track, they discovered 15 species of skyhopper exist – each separated by the rugged mountain landscape.

The true biodiversity of the alps is unknown. What we do know is that it is heavily fragmented. What may look like one species across the alps is likely to be many species each occupying small areas. This means they’re even more vulnerable than currently recognised.

Helping Them Hang On

Much of the Australian Alps region is contained in national parks, but this alone is not adequate protection for our alpine biodiversity.

Greenhouse gas emissions to date have put our alpine biodiversity on a knife’s edge. Australian and international governments must swiftly undertake far more ambitious climate action to cool the alps.

And more effort is needed to give our alpine ecosystems the best chance of coping with climate change. This includes allowing Traditional Owners to connect to and manage Country and removing threats such as feral species, disease and habitat destruction.![]()

Kate Umbers, Senior Lecturer in Zoology, Western Sydney University; Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University, and Matthew Shanks, Director, Cultural Land Management at Taungurung Land and Waters Council, Indigenous Knowledge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Two new Australian mammal species just dropped – and they are very small

You probably know about the Tasmanian devil. You might even know about its smaller, less-famous relative, the spotted-tailed quoll.

But these are far from the only meat-eating marsupials. Australia is home to a suite of other carnivorous and insectivorous pouched mammals as well, some of them the size of a mouse or smaller.

Tiniest of all are the planigales, some of which weigh less than a teaspoonful of water. Despite their size, these fierce predators often take on prey as big as themselves.

To date, there are four known species of planigale found across Australia. We have recently discovered another two species, both inhabitants of the Pilbara region of northwest Western Australia: the orange-headed Pilbara planigale (Planigale kendricki) and the cracking-clay Pilbara planigale (P. tealei).

How Many Kinds Of Planigale Are There?

The name planigale translates to “flat weasel”, an allusion to their extremely flat heads, which allow them to shelter in small cracks in rocks and clay soils. Planigales are among Australia’s smallest mammals, with some weighing an average of 4–6 grams (and measuring around 11cm in length), and other species a bit larger at 8–17 grams (and 13cm long).

Scientific studies from the late 1970s onward using body-shape and DNA data have suggested there are many more planigale species than we think.

We put these theories to the test, and found that planigales in the Pilbara display unique body shapes and are genetically unrelated to any of the four known planigale species.

Why Have These Species Only Been Described Now?

The process of describing these two new species was actually started more than 20 years ago, by scientists who were working at the Western Australian Museum at the time.

Their work began after ecologists conducting surveys for developing mines in the Pilbara were capturing planigales that didn’t really fit the descriptions of the known species. For want of a better option, they were still usually identified as either the common planigale (P. maculata) or the long-tailed planigale (P. ingrami).

Scientists led by taxonomist Ken Aplin began examining specimens held in the WA Museum and sequencing their DNA. These studies helped to confirm the discovery of two new species.

Sadly, Ken fell ill and passed away in 2019. This is where we stepped in.

Through support from the Australian Biological Resources Study and the Queensland University of Technology we were able to finish off Ken’s species descriptions and submit the research for publication. This is a crucial step in taxonomy – the species description has to be published before the new name can be considered official.

What Do We Know About The New Species?

Both new species occur in the Pilbara and surrounding areas. The orange-headed Pilbara planigale is the larger of the two, weighing an average of 7g (up to 12g for large males) with a longer, pointier snout and bright orange colouring on the head.

The cracking-clay Pilbara planigale is much smaller, averaging just 4g with darker colouration and a shorter face. It has only been found on cracking clay soils, hence its name.

The orange-headed Pilbara planigale has been found on rocky and sandy soils as well, but both species require a dense cover of native grasses to persist. Both species actively forage during the night, while taking shelter during the day.

This means the two widespread species, the common planigale and the long-tailed planigale, do not occur in the Pilbara or on neighbouring Barrow Island, as was previously thought.

There is still a lot more work for us to do as there remain two “species complexes” of planigales. These are groups where genetic data suggests a species is comprised of multiple different forms.

We’ll be following up on this with more analysis to define more of Australia’s tiniest mammals.![]()

Linette Umbrello, Postdoctoral research associate, Queensland University of Technology; Andrew M. Baker, Academic in Ecology and Environmental Science, Queensland University of Technology, and Kenny Travouillon, Curator of Mammals, Western Australian Museum

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

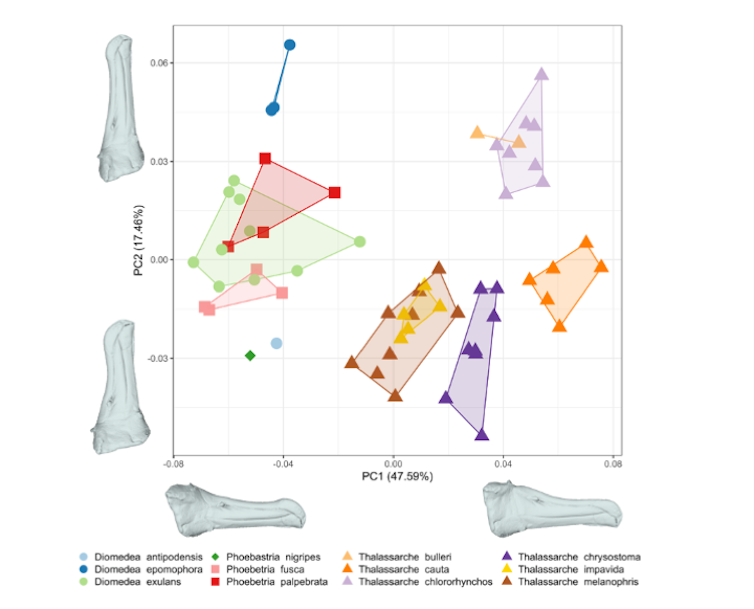

Thick ones, pointy ones – how albatross beaks evolved to match their prey

Albatross are among the world’s largest flying birds, with wingspans that can stretch beyond a remarkable three metres. These majestic animals harness ocean winds to travel thousands of kilometres in search of food while barely flapping their wings.

Young albatross, embarking on their first journey, can spend up to five years at sea without ever touching land.

Yet not all albatross are the same. Across the world’s oceans there exist 22 species, with many sharing an overlapping range around the Southern Ocean — a region synonymous with cold, roaring winds and towering waves.

Our new research published today shows how albatross species evolved different beak shapes to make the most of the ocean’s food resources. These species have adapted to different seafood diets.

Move Over, Darwin’s Finches!

In 1835 Charles Darwin discovered the finches of the Galápagos Islands and noted their beaks varied in shape and size to suit different diets. This observation became a centrepiece for the theory of evolution, showing how species adapt to different ways of life.

From a single common ancestor, Darwin’s finches diversified. Some birds have thick beaks for feeding on seeds and nuts, while others have pointed beaks for eating insects. This variation allows species to specialise, helping them to share available food sources and limit competition.

Albatross have fascinating beaks. Unlike most other birds, they have a “compound” beak made of multiple pieces of keratin. Albatross spend most of their lives at sea, so they have adapted to drink seawater. They use a special gland to remove salt from the seawater and their beaks contain tube-like passages that excrete the salty liquid.

By studying the shape of albatross beaks in three dimensions (3D), our new research shows that, just like Darwin’s finches, albatross beaks vary in size and shape to adapt to different diets.

The 3D Scanning Revolution

Wildlife research is undergoing a revolution as scientists use new 3D scanning and modelling techniques to compare the anatomy of animals. This gives fresh insights into their ecology and evolution.

Using museum specimens, we made 3D digital models of beaks for 61 birds from 12 different albatross species. We compared the size and shape of different species’ beaks. We tested if closely-related species had similar beaks. Alternatively, beaks might be more alike between species that are distantly related but consume similar food. Such a pattern would be an example of convergent evolution.

We found beak size and shape varied between albatross species, making it a useful tool for identifying species that otherwise look similar.

Beaks also varied between species that eat either invertebrate prey, fish, or a mixture of both. Even in species that have similarly shaped beaks and diets, variations in beak size enable them to focus on prey of different sizes within the same category, such as small versus large fish.

The variation is most obvious in changes in the length and thickness of the beaks, but they can also vary in how the separate keratin pieces come together to make up the whole shape of the beak. These differences help albatross species to avoid competition with each other as they forage together over the open ocean.

A Future For Albatross?

This research was made possible by the large collection of more than 750 albatross specimens preserved at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

Almost all of these specimens came to the museum after being caught as bycatch in past longline fisheries, where bird carcasses were collected to identify which species were being captured on hooks.

Fortunately, improved fishing methods have reduced albatross bycatch, but this collection now remains as a valuable resource for new research like this into the biology of these birds.

Sadly, fisheries are not the only threat these extraordinary birds face. The first European record of an albatross from 1593 tells us how the bird was captured, killed and eaten. Today, of the 22 albatross species, two are considered critically endangered, seven species are endangered, and a further six species are considered vulnerable.

Albatross are still frequent victims of fisheries bycatch, plastic pollution, and introduced predators on their breeding islands.

Like most wildlife species, the persistent threat of climate change looms large, as the world’s oceans warm and alter their habitat and the abundance of their prey.

Despite their evolutionary marvels and remarkable adaptations to the harshest ocean on Earth, the albatross serves as a poignant reminder of nature’s fragility. It is our duty to ensure their wings continue to soar above our oceans for generations to come.![]()

Jane Younger, Lecturer, Southern Ocean Vertebrate Ecology, University of Tasmania; David Hocking, Adjunct Research Associate, Monash University, and Josh Tyler, Postgraduate Research Student, Department of Life Sciences, University of Bath

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Nearly two-thirds of the top fossil fuel producers in Australia and the world aren’t on track for 1.5℃ climate target

Rapid reductions in fossil fuel production and use are essential to limit global warming to 1.5℃ compared to pre-industrial levels. Our new research shows most of the world’s major coal, oil and gas companies are yet to make meaningful reductions.

Some companies have been quick to announce net-zero targets or other claims of alignment with the Paris Agreement. But how do their actions compare to what must be done to achieve the agreed goal of keeping the temperature increase below 1.5℃?

Our research developed a method to track whether production by individual fossil fuel companies is aligned with putting the world on a 1.5℃ climate pathway. We use production budgets as these can be compared directly with fossil fuel demand scenarios and avoid the need for complex emissions calculations.

More than 60% of the top 142 oil, gas and coal companies – including three of the five Australian companies assessed – were not on track. Rio Tinto and BHP were the two Australian companies found to be on track. Between 2014 and 2020, the fossil fuel sectors exceeded overall production budgets by 64% (oil), 63% (gas) and 70% (coal).

These budgets are the levels of production needed to limit warming to 1.5℃ under the Paris Agreement “middle-of-the-road scenario” (where trends broadly follow their historical patterns).

We need freely available information to understand the impact companies are having on the climate and to hold them accountable. Our results are on the website Are you Paris compliant?.

How Can We Track Companies’ Actions?

In an earlier research paper, we laid the foundation of what Paris compliance means using a strict science-based approach. We developed several conditions.

Firstly, the base year of measuring progress of an entity should be the same as the starting year of the decarbonisation scenario being used. While there are many such scenarios, the pathway has to be consistent with a 1.5℃ or “well below” 2℃ warming limit as stated in the Paris Agreement.

To prevent constant delay of action, only pathways starting in or before 2015 should be used. That’s when the world’s nations committed to decarbonisation under the Paris Agreement. For example, if a company wants to track its alignment with a well-below 2℃ pathway starting in 2014, it should start tracking from 2014.

Also, companies should make up for action deficits since the base year to stay within their budgets.

Commonly used frameworks such as the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) and the London School of Economics’ Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI) don’t comply with these conditions. The not-for-profit SBTi is the primary point of call for companies wanting to develop emission reduction targets. It’s a partnership between CDP (which runs the global system of environmental impact disclosures), UN Global Compact, World Wildlife Fund and World Resources Institute.

We have now applied our more rigorous approach to fossil fuel companies. Using publicly available production data from the Climate Accountability Institute allows us to assess a large number of companies.

We evaluated the 142 largest producers of coal, oil and gas against four possible emissions “pathways” to limit temperature increase to 1.5℃ this century. We used three pathways set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2014 and the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero Emissions pathway from 2020. Each pathway involves different scenarios of climate actions, emissions and carbon capture and storage.

Off Course, With Much More To Do

Not only did we find the majority of these companies are not currently aligned, but the outlook is also troubling. If recent trends (2010-2018) continue, the companies would produce up to 68% (coal), 42% (oil) and 53% (gas) more than their cumulative production budgets by 2050.

In Australia, the three companies not on track were Whitehaven Coal, Santos and Woodside. They exceeded their production budgets by 232% (Woodside coal), 28% (Santos oil) and 33% (Santos gas), and 39% (Woodside gas, on track for oil).

BHP was on track because it has reduced its coal, oil and gas production more than required between 2014 and 2020 under the middle-of-the-road 1.5℃ scenario. It used 87% (coal), 85% (oil) and 92% (gas) of its production budgets. Rio Tinto entirely stopped its production of coal in 2018.

While we project future production using historical (2010-2018) growth, a next step would be to assess how current production plans align with 1.5℃ pathways.

Companies can use our method to see how much they need to reduce production to be aligned. They can also see how much carbon capture and storage is required under a certain 1.5℃ pathway.

Tracking Enables Accountability

For companies to claim Paris alignment, they must be accountable for achieving the required levels of mitigation (reducing production and carbon capture and storage) under a particular 1.5℃ pathway.

Our method provides a foundation to drive this change. It offers a relatively simple way to measure corporate actions against the reductions required.

Our work aids the development of standards, regulation and guidance on what Paris alignment actually means. The Science Based Targets initiative has yet to finalise a method for the oil and gas sector. It has no method for coal.

Our method provides a process that can fill this void. In addition to tracking individual companies’ compliance with the Paris Agreement, we require clarity on their intentions beyond just setting targets. The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) will play a vital role by requiring detailed climate transition plans from companies in countries that adopt its standards.

Tracking how companies are performing empowers all stakeholders – including governments, investors and individuals like you and me – to advocate for climate action and make climate-safe decisions. For example, investors can use this information to decide which companies to invest in and advocate for change where required. Governments can integrate this information into corporate guidelines for climate action.![]()

Saphira Rekker, Senior Lecturer in Sustainable Finance, The University of Queensland and Belinda Wade, Adjunct Associate Professor, School of Business, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

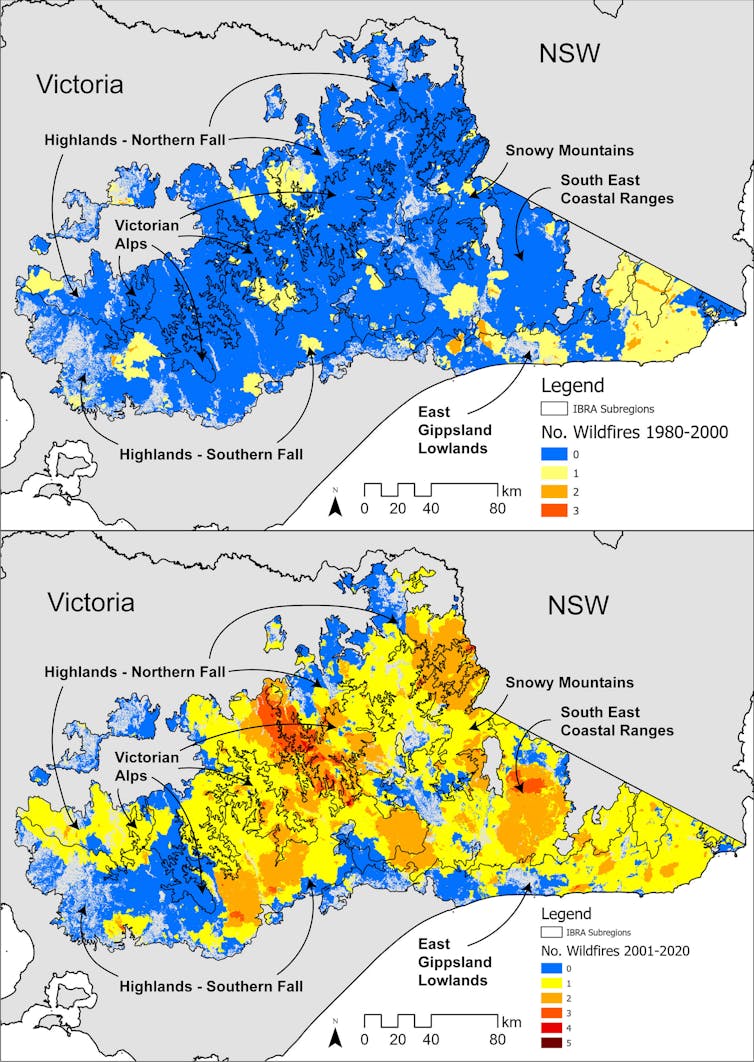

Yes, climate change is bringing bushfires more often. But some ecosystems in Australia are suffering the most

David Lindenmayer, Australian National University; Chris Taylor, Australian National University; Maldwyn John Evans, Australian National University, and Philip Zylstra, Curtin UniversityBlack Summer, Black Saturday, Ash Wednesday: these and so many other bushfire disasters are regular reminders of the fact Australia is among the most flammable continents on Earth.

Alarmingly, climate change is making bushfires more frequent. This is a huge concern, given the devastating effects of fire on both human communities, and the diversity of plants and animals.

As our new research shows, however, the trend is not uniform. We examined the frequency of wildfires in parts of Victoria over the past 40 years. We found fire frequency is increasing in all ecosystems we studied, but to varying extents. In some places, fires are occurring so often, entire ecosystems are at risk of collapse.

These nuances are important. They point to the urgent need to tackle climate change. They also have major implications for biodiversity conservation, and bushfire management and prevention, and cast further questions over the controversial practice of native forest logging.

Fires Are Becoming Shockingly More Frequent

To understand the effects of wildfires, it’s not enough to focus on a single fire. We must examine successive fires in an area and how frequently they occur.

Our analysis focused on southeastern Australia – one of the most populated, heavily forested, and fire-prone parts of the continent.

Specifically, we homed in on six geographic areas in Victoria known as “bioregions”. Bioregions vary in their climatic conditions, geological features, biodiversity and other characteristics. The six areas together cover 4.64 million hectares – much of it forest.

We excluded deliberate burns such as hazard reduction (or prescribed) burns lit by fire authorities. We also excluded places that had been logged, because they’re known to be at a high risk of severe fire – and so including them would have skewed the results.

We found a major change in the frequency of wildfire over the past four decades. Between 2001 and 2020, there were substantially more fires in almost all bioregions than between 1981 and 2000.

In the earlier two decades, almost 667,000 hectares of forest burned. More than 36,000 hectares of this burned more than once.

In the latter two decades, 3.1 million hectares burned. About 1 million hectares burned more than once.

The change was most pronounced in the three bioregions at higher elevations - the Snowy Mountains, Victorian Alps, and South East Coastal Ranges (which lie southeast of the Snowy Mountains).

The least amount of change was found in Victoria’s East Gippsland Lowlands. This area had more fires in 1981-2000 than the other areas we studied, but only a modest increase in number of fires between 2000 and 2020.

Fascinatingly, however, the story doesn’t end there.

A Complex Picture

We found the changes in fire frequency were nuanced and complex. Across the study areas, the frequency of wildfires was very strongly affected by topographical features such as slope, as well as climate measures such as rainfall and temperature. However, the influence of these factors differed markedly between areas.

For example, in four bioregions we studied, wildfires became more frequent as rainfall declined. But the opposite was true in the other two bioregions.

The reasons for these complex findings remain unclear. Increased average rainfall may, in some cases, arrive in storm events with associated lightning (which can start fires). It can also lead to faster water runoff, meaning rainfall may not be as well retained in the soil as otherwise might be, and forests could become drier.

Similarly, fire frequency was also affected by the extent to which temperatures deviated from the long-term average. Generally, this deviation was toward hotter temperatures.

In some areas, this temperature variation was associated with less frequent fires. In others, it coincided with more frequent fires. Again, the reasons for these differences are not yet clear.

The increase in fire frequency is alarming. Some places where fire has been particularly frequent include wetter forests, such as those dominated by ash-type eucalypts. Consistent with earlier analyses, we found evidence of locations that have experienced up to four fires in the past 25 years.

Fires in ash-type ecosystems have historically occurred only once every 75 to 150 years. Fires occurring too often in these environments may lead to the entire ecosystem collapsing.

Our results have major implications for the native forest logging forestry industry. More frequent fires means many trees burn well before they’ve reached an age suitable for sawlogs. This suggests yields from native forest logging in south-eastern Australia will decline, making the practice even more financially precarious.

What Must Happen Next?

Our results confirm wildfires are becoming more frequent in parts of fire-prone south-eastern Australia. And while climate change influences the frequency of fire, the effects vary across geographical areas.

Clearly, we must seek to limit the number of wildfires. An obvious response is to take more strident steps to tackle climate change. But even if humanity meets this huge global challenge, it will be a long time before we see demonstrable changes in climate conditions.

More immediate options include managing vegetation to reduce flammability. For example, activities such as logging and thinning can make forests more flammable, so such practices should be halted in these vulnerable ecosystems.

Greater efforts are needed to conserve biodiversity that is sensitive to fire, and to conserve ecosystems at risk of collapse. We must also embrace new technologies to detect wildfires as soon as they ignite, and suppress them as quickly as possible.![]()

David Lindenmayer, Professor, The Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University; Chris Taylor, Research Fellow, Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University; Maldwyn John Evans, Senior Research Fellow, Australian National University, and Philip Zylstra, Adjunct Associate Professor at Curtin University, Research Associate at University of New South Wales, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Giant old trees are still being logged in Tasmanian forests. We must find ways of better protecting them

The photo said it all. On the back of a logging truck, a tree so large it could barely fit. It was cut down in Tasmania’s Florentine Valley, not far from Mount Field, where it had started life as a seedling over a century ago.

The photo triggered outrage from conservationists and the public. Greens founder Bob Brown called the felling “a national disgrace” and urged a halt to the felling of old growth giants.

Giant trees are supposed to be protected as a matter of normal process. Trees over 85 metres high or with a trunk volume of 280 cubic metres should be retained with a 100 metres radius of uncleared bush around them. The loggers say this one was cut down for “safety reasons”. We don’t know if this one met those criteria.

Whether or not that’s true, the felling has sparked a new battle in Tasmania’s long-running forest wars. Unlike in Victoria, old growth logging in Tasmania doesn’t look like ending any time soon. But we must find ways to better protect these giants of nature, the tallest flowering trees in the world. They store huge amounts of carbon in their trunks and in the soil, provide habitat for many forest creatures and produce awe in humans who see them.

Why Was This Giant Logged?

The truck transporting the trunk of the tree was seen exiting Tasmania’s Florentine Valley. This valley has been the site of many protests over the years. Part of it is in the World Heritage Area, but logging is still allowed in other parts of it.

Why was a tree this size cut down? Safety.

“On occasion, it may be necessary for Sustainable Timber Tasmania to remove a large tree where it presents an access or safety risk,” a spokeswoman told news.com.au.

That is possible. Giant old trees can hollow out as they age and become a safety risk if people are allowed near them. But the trunk in the published photo shows no sign of hollowing out. If it was a giant, the mandatory 100 metre protection zone would eliminate almost all risk.

At the very least, the felling suggests not all of Tasmania’s ancient trees are adequately protected. What it shows is the need for independent assessment of areas slated for logging likely to be home to giants – and to ensure trees felled for “safety” reasons" genuinely need to be removed.

And what about trees that are not quite big enough to be protected? As ecologist and tall-tree expert Dr Jennifer Sanger has observed, the 85-metre figure is arbitrary. We need to plan for the giant trees of the future by keeping the almost giant trees of now.

Ancient Giants Matter

Mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) is the world’s largest flowering plant. The trees can live up to 700 years and reach over 100 metres in height.

Do they matter more than other trees? Yes. That’s because big old trees begin to decay in interesting ways, creating hollows for possums and birds to nest in, and even hollowing out inside the trunk, which makes habitat for bats. They play an outsized role in ecosystems in providing shelter, hollows and food.

Ironically, these processes of decay can make these giants all but useless for timber. If you’re logging a giant to turn it into large structural beams, you might find it’s hollow inside and all but useless.

The sheer size of these trees also means they have more habitat to offer for other forms of life. Native animals, birds and invertebrates rely on these trees. Plus, they store massive amounts of carbon, both above ground and in the soil. Cutting down the old growth forests of which these trees are a part and turning them into production forests results in a substantial ongoing leakage of soil carbon for many generations.

The trees induce awe and wonder in most who see them. People are passionate about keeping them on the planet – one of the reasons for the forest wars in the first place. These huge trees attract tourists to walk beneath them or up in their canopies.

Haven’t Tasmania’s Forest Wars Stopped?

Sadly, no. The decades-long battle between loggers and conservationists in Tasmania has certainly become less intense after many old growth forests such as the Weld, Styx, Florentine and Great Western Tiers gained World Heritage protection in 2013.

But native forest logging in Tasmania shows no sign of stopping entirely. Old-growth logging continues around the state, including in the Florentine Valley where this giant tree was felled. Rainforest trees in some reserves are available for logging.

In May, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews announced his state would this year end native forest logging, which has long been a loss-making industry. Instead, plantation logging will be expanded.

Why can’t Tasmania do this? It mostly comes down to politics. Tasmania is the poorest state in Australia, and the few jobs logging native forests are politically important.

Also, the wood from larger trees are better for ends such as veneer, exposed beams and furniture than most plantation-sourced wood. Their felling can be rewarding financially for the companies that do it, as no-one has to pay to grow them and they can contain large volumes of high quality wood.

But overall, cutting down old growth forests may not stack up economically, with the quasi-government enterprises managing production forests often making losses. It didn’t make much financial sense in Victoria, and may not in Tasmania.

Will the felling of this giant bring change? Don’t bet on it. Probably the best we can hope for is to preserve as many giants – and near-giants – as we can. And to do that, we’ll need independent assessments of old growth forest slated for logging to double-check measurements of these precious trees. ![]()

Jamie Kirkpatrick, Professor of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

More Than 250 Scientists Call For An End To Land Clearing

Let's End Land Clearing

Letters Show Need For Urgent Action To Protect Threatened Species

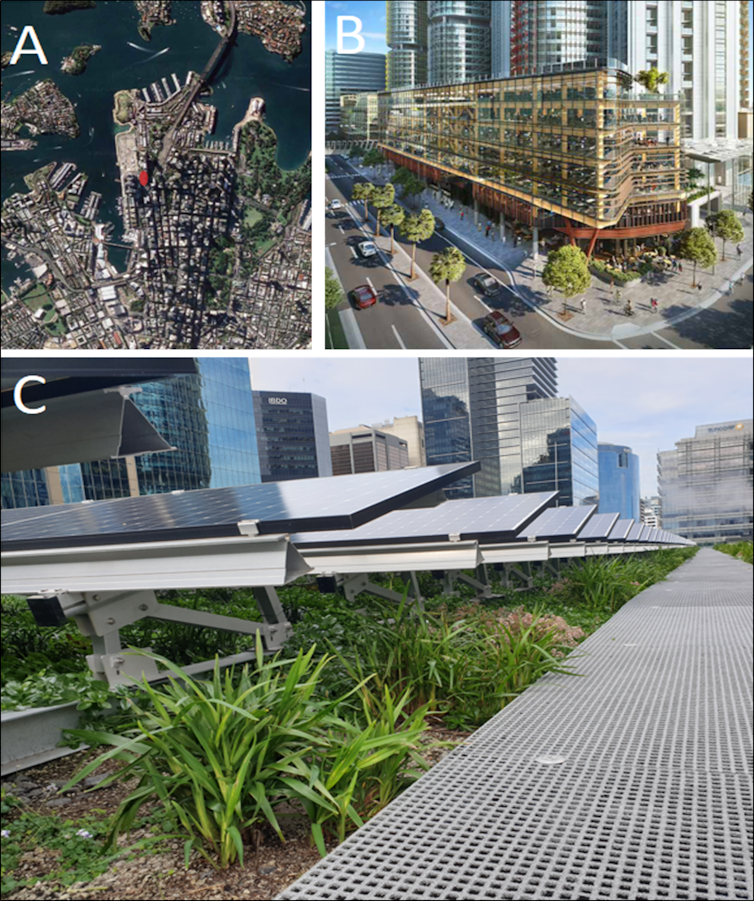

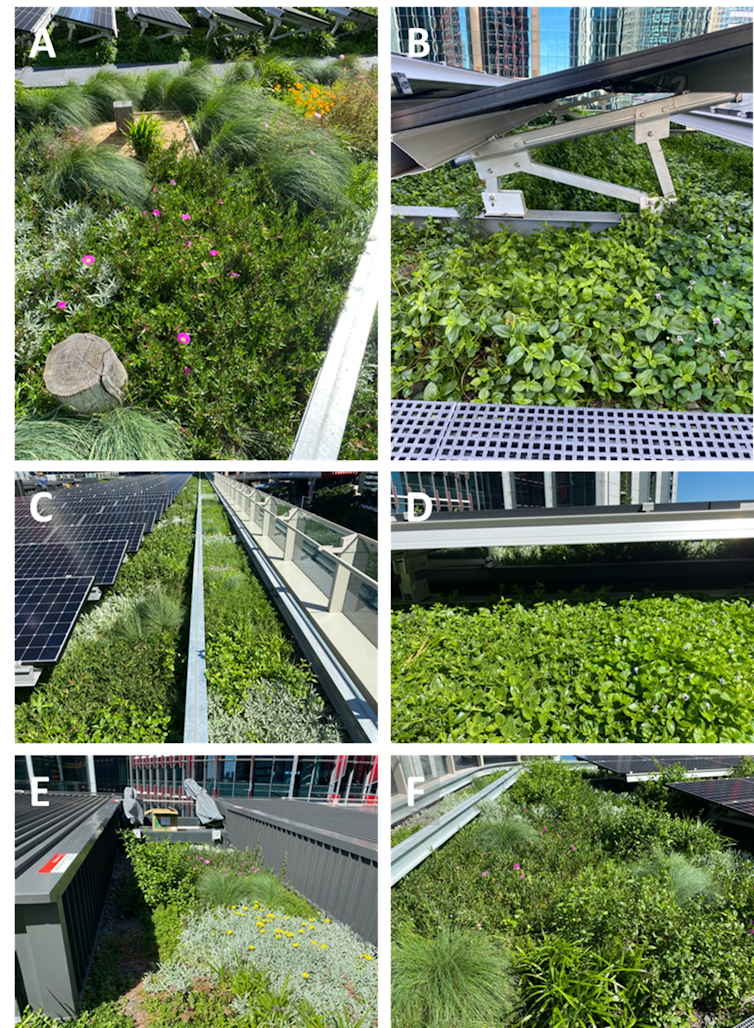

A green roof or rooftop solar? You can combine them in a biosolar roof, boosting both biodiversity and power output

Growing city populations and limited space are driving the adoption of green roofs and green walls covered with living plants. As well as boosting biodiversity, green roofs could play another unexpectedly valuable role by increasing the electricity output of solar panels.

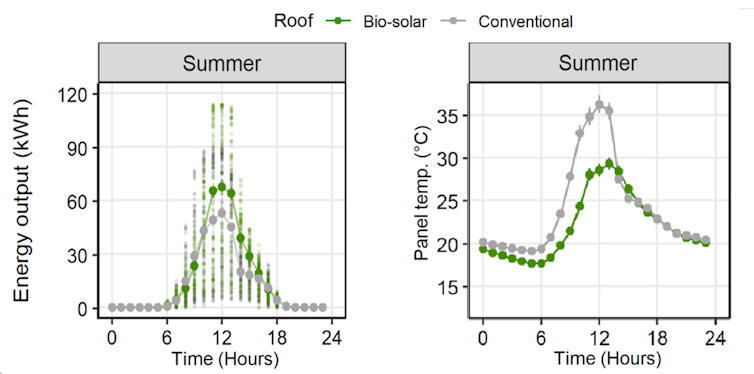

As solar panels heat up beyond 25℃, their efficiency decreases markedly. Green roofs moderate rooftop temperatures. So we wanted to find out: could green roofs help with the problem of heat reducing the output of solar panels?

Our research compared a “biosolar” green roof – one that combines a solar system with a green roof – and a comparable conventional roof with an equivalent solar system. We measured the impacts on biodiversity and solar output, as well as how the plants coped with having panels installed above them.

The green roof supported much more biodiversity, as one might expect. By reducing average maximum temperatures by about 8℃, it increased solar generation by as much as 107% during peak periods. And while some plant species outperformed others, the vegetation flourished.

These results show we don’t have to choose between a green roof or a solar roof: we can combine the two and reap double the rewards.

How Was The Study Done?

Many studies have tested a single rooftop divided into “green roof” and “non-green roof” sections to measure the differences caused by vegetation. A problem with such studies is “spatial confounding” – the effects of two nearby spaces influencing one another. So, for example, the cooler green roof section could moderate the temperature of the non-green section next to it.

In studies that use distinct buildings, the buildings might be too far apart or too different in construction to be comparable.

The two buildings in our study were the same height, size and shape and located next to each other in Sydney’s central business district. The only difference was Daramu House had a green roof and International House did not.

We selected a mix of native and non-native grasses and non-woody plants, which would flower across all seasons, to attract diverse animal species.

The biosolar green roof and conventional roof had the same area, about 1860 square metres, with roughly a third covered by solar panels. Vegetation covered about 78% of the green roof and the solar panels covered 40% of this planted area.

To identify which species were present on the roofs we used motion-sensing cameras and sampled for DNA traces. We documented changes in the green roof vegetation to record how shading by the solar panels affected the plants.

How Did The Panels Affect The Plants?

In the open areas, we observed minimal changes in the vegetation cover over the study period compared to the initial planted community.

Plant growth was fastest and healthiest in the areas immediately around the solar panels. Several species doubled in coverage. We selected fast-growing vegetation for this section to achieve full coverage of the green roof beds as soon as possible.

The vegetation changed the most in the areas directly below and surrounding the solar panels. The Baby Sun Rose, Aptenia cordifolia, emerged as the dominant plant. It occupied most of the space beneath and surrounding the solar panels, despite having been planted in relatively low densities.

This was surprising: it was not expected the plants would prefer the shaded areas under the panels to the open areas. This shows that shading by solar panels will not prevent the growth of full and healthy roof gardens.

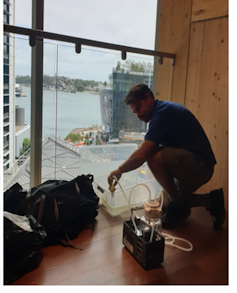

What Were The Biodiversity Impacts?

We used environmental DNA (eDNA) surveys to compare biodiversity on the green roof and conventional roof. Water run-off samples were collected from both roofs and processed on site using portable citizen scientist eDNA sampling equipment to detect traces of DNA shed by the species on the roof.

The eDNA surveys detected a diverse range of species. These included some species (such as algae and fungi) that are not easily detected using other survey methods. The results confirmed the presence of bird species recorded by the cameras but also showed other visiting bird species went undetected by the cameras.

Overall, the green roof supported four times as many species of birds, over seven times as many arthropods such as insects, spiders and millipedes, and twice as many snail and slug species as the conventional roof. There was many times the diversity of microorganisms such as algae and fungi.

Encouragingly, the green roof attracted species unexpected in the city. They included blue-banded bees (Amegilla cingulata) and metallic shield bugs (Scutiphora pedicellata).

How Did The Green Roof Alter Temperatures?

The green roof reduced surface temperatures by up to 9.63℃ for the solar panels and 6.93℃ for the roof surfaces. An 8℃ reduction in average peak temperature on the green roof would result in substantial heating and cooling energy savings inside the building.

This lowering of temperatures increased the maximum output of the solar panels by 21-107%, depending on the month. Performance modelling indicates an extensive green roof in central Sydney can, on average, produce 4.5% more electricity at any given light level.

These results show we don’t have to choose between a green roof or a solar roof. We can combine them to take advantage of the many benefits of biosolar green roofs.

Biosolar Roofs Can Help Get Cities To Net Zero

The next step is to design green roofs and their plantings specifically to enhance biodiversity. Green roofs and other green infrastructure may alter urban wildlife’s activities and could eventually attract non-urban species.

Our green roof also decreased stormwater runoff, removed a range of run-off pollutants and insulated the building from extremes of temperature. A relatively inexpensive system provides all of these services with moderate maintenance and, best of all, zero energy inputs.

Clearly, biosolar green roofs could make major contributions to net-zero cities. And all that’s needed is space that currently has no other use.![]()

Peter Irga, ARC DECRA Fellow and Lecturer in Air and Noise Pollution, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Technology Sydney; Eamonn Wooster, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Gulbali Institute, Charles Sturt University; Fraser R Torpy, Director, Plants and Environmental Quality Research Group, University of Technology Sydney; Jack Rojahn, PhD Candidate, Institute for Applied Ecology, University of Canberra, and Robert Fleck, Research Scientist, School of Life Sciences, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Rising seas and a great southern star: Aboriginal oral traditions stretch back more than 12,000 years

Content note: this article mentions genocide and acts of colonial violence against Aboriginal people.

How long do you think stories can be passed down, generation to generation?

Hundreds of years? Thousands?

Today, we publish new research in the Journal of Archaeological Science demonstrating that traditional stories from Tasmania have been passed down for more than 12,000 years. And we use multiple lines of evidence to show it.

Tasmania’s Violent Colonial History

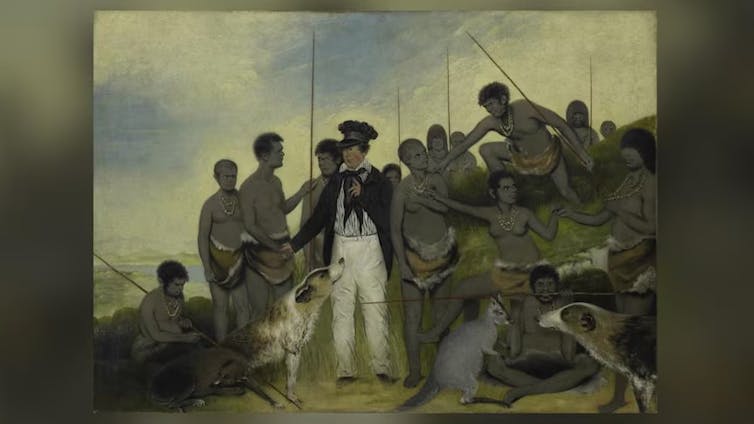

Within months of establishing a colonial outpost on the island in 1803, British officials had committed several acts of genocide against Aboriginal Tasmanian (Palawa) people. By the mid-1820s, soldiers, convicts, and free settlers had taken up arms to fight what became known as the “Black War”, aimed at capturing or killing Palawa and dispossessing them of their Country.

Tasmania’s colonial government appointed George Augustus Robinson to “conciliate” with the Palawa. From 1829 to 1835, Robinson travelled with a small group of Palawa, including Trukanini and her husband, Wurati. By 1832, Robinson’s “friendly mission” had turned to forced removals.

Robinson kept a daily journal, which included records of Palawa languages and traditions. Over time, Palawa men and women slowly began to share some of their knowledge, explaining how their ancestors came to Tasmania (Lutruwita) by land from the far north, before the sea formed and turned their home into an island. They also spoke about the Sun-man, the Moon-woman, and a bright southern star.

These stories are of immense importance to today’s Palawa families who survived the devastating impact of colonisation, and who continue to share these unique creation stories. Through careful investigation of colonial records, and collaborating with Palawa knowledge-holders, we found something remarkable.

Rising Seas And The Formation Of Lutruwita

Over the past 65,000 years, Australia’s First Peoples witnessed natural disasters and significant changes to the land, sea and sky. Volcanoes spewed fire, earthquakes shook the land, tsunamis inundated the coastlines, droughts plagued the continent, meteorites fell to the earth, and the stars shifted in the night sky.

Some 20,000 years ago, the world was in the grip of an ice age. Australia was conspicuously drier than it is today, and the ocean was significantly lower. All of that sea water was bound up in glaciers that swathed vast tracts of land, particularly across the Northern Hemisphere, and polar ice caps much larger than ours today.

As time passed, temperatures gradually rose and the ice began to melt. After 10,000 years, the sea level had risen 125 metres; a process that dramatically transformed coastlines and submerged landscapes that had been ancestral Country for thousands of generations. This forced humans to change where and how they lived.

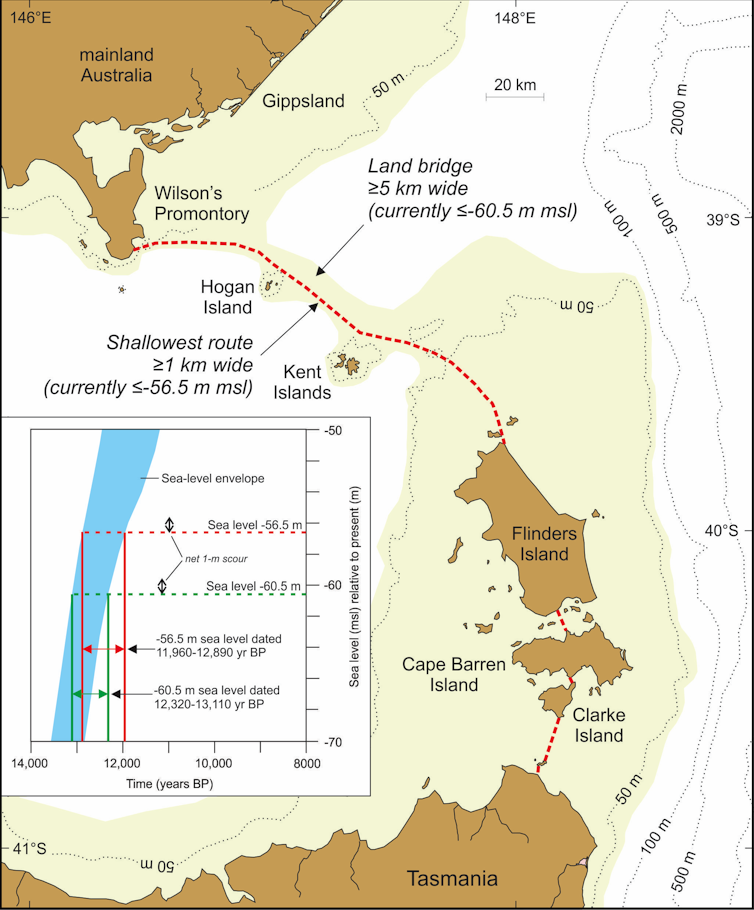

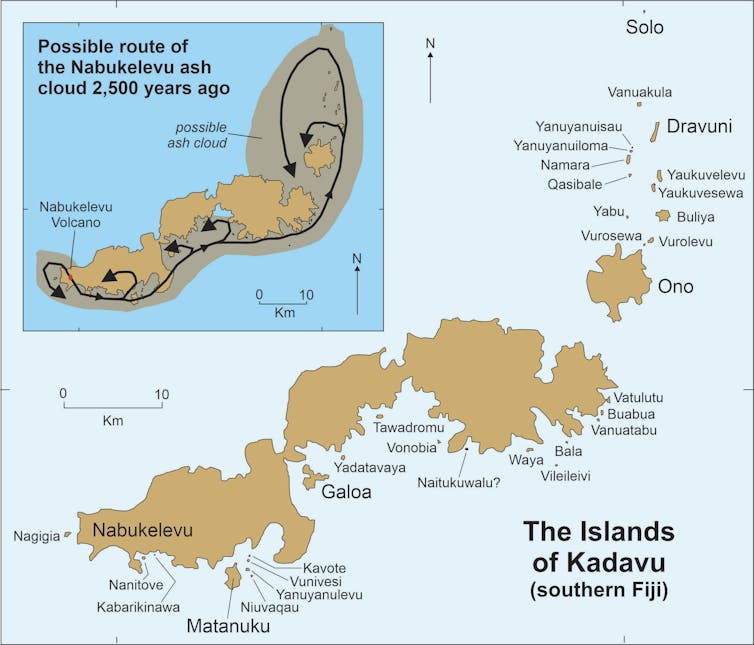

During the ice age, both Lutruwita and Papua New Guinea were connected to mainland Australia by dry land, forming a landmass called Sahul. As the seas rose, Tasmania’s connection gradually narrowed to form what geologists call the Bassian Land Bridge.

People continued to live on this “land bridge”, but by 12,700 years ago it had narrowed to just 5 kilometres wide (lime-green shading on the map above). Habitable land was gradually reduced as the sea closed in. Less than 300 years later, the “land bridge” was gone and Lutruwita was completely surrounded by water.

Palawa traditions from that time survived hundreds of generations of retelling, forming part of a larger canon of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories around Australia. They described rising seas and submerging coastlines as the ice sheets melted before levelling off around 7,000 years ago. Stories of similar antiquity are known from other parts of the world.

A Great South Star

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures developed rich and complex knowledge systems about the stars, which are still used today. They describe the movements of the Sun, Moon, and stars, as well as rare cosmic events, such as eclipses, supernovae, and meteorite impacts.

In the 1830s, a Palawa Elder spoke about a time when the star Moinee was near the south celestial pole. He laid down a pair of spears in the sand and drew a few reference stars to triangulate its position.

Colonists seemed perplexed about the presence of an antipodean counterpart to Polaris, as no southern pole star exists today. Some tried to identify the stars on the star map, but seemed confused and labelled them incorrectly, as they were unaware of an important astronomical process called axial precession.

As the Earth rotates, it wobbles on its axis like a spinning top. This shifts the location of the celestial poles, tracing out a large circle every 26,000 years. As thousands of years pass by, the positions of the stars in the sky slowly change.

Long ago, Canopus was at its southernmost point in the sky. Lying just over 10 degrees from the south celestial pole, it appeared to always hover in the southern skies each night. That last occurred 14,000 years ago, before rising seas turned Lutruwita into an island.

Exciting Collaborative Futures

We can see through independent lines of evidence that Palawa stories have been passed down for more than twelve millennia. We also find here the only example in the world of an oral tradition describing a star’s position as it would have appeared in the sky over 10,000 years ago.

Our investigation of colonial records that record traditional systems of knowledge has demonstrated a powerful cross-cultural way of better understanding deep human history. This also recognises the immense value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditions today.

This research was co-authored by graduate Michelle Gantevoort from RMIT University, and student researchers Ka Hei Andrew Law from the University of Melbourne and Mel Miles from Swinburne University of Technology.![]()

Duane Hamacher, Associate Professor, The University of Melbourne; Greg Lehman, Pro Vice Chancellor, Aboriginal Leadership, University of Tasmania; Patrick D. Nunn, Professor of Geography, School of Law and Society, University of the Sunshine Coast, and Rebe Taylor, Associate Professor of History, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thousands of migratory birds will make NZ landfall in spring – will they bring a deadly bird flu with them?

A highly pathogenic bird flu is currently sweeping the world – and New Zealand could be better prepared for its potential arrival.

Over the past few years, more and more birds have come to harbour new strains of this deadly virus as it continues to evolve to infect new species. It is now causing a panzootic (a pandemic of animals) among wild aquatic birds.

The virus, known as highly pathogenic avian influenza virus, has likely already killed thousands of birds worldwide (the exact number is difficult to estimate). What’s more, spillovers to non-avian hosts such as mammals are becoming increasingly common.

While only a few human cases have been reported, cats, foxes and sea lions are being infected at an alarming rate.

Despite intercontinental transmission of highly pathogenic bird flu variants during the past 20 years, no cases have been reported in New Zealand – yet. Australia is also considered free of the virus, although a few years ago a strain in chickens was thought to have evolved locally.

One reason we emphasise “yet” is because each spring, thousands of migratory birds arrive in Aotearoa New Zealand. Will they bring these deadly strains of avian influenza with them? An unwanted viral hitchhiker of this type could have devastating consequences for our biota and industries.

How Bird Flu Could Get To New Zealand

New Zealand is conventionally assumed to be at low risk from highly pathogenic avian influenza. We are thought to be too far away from other landmasses and not on routes that migratory waterfowl usually take.

Any migratory shore and seabirds that do usually make landfall in New Zealand are thought likely to die of the disease before reaching our shores.

But some wild birds might experience asymptomatic infections, even of strains that are typically highly pathogenic.

Also, the recent expansion of susceptible host species, including to marine mammals, increases the risk that some species might carry the virus here.

As for geography, research suggests wild bird migrations are responsible for transmitting the virus from Europe to the Americas across the Atlantic, as well as throughout Eurasia. So why not to New Zealand? Are we really just too far away?

How To Prepare For An Outbreak

If this highly pathogenic avian influenza virus were to arrive, New Zealand is not as prepared as it could be. The major reason is that we have very little active virus surveillance of wildlife.

New Zealand monitors livestock, including cows, sheep and poultry, for a range of diseases. But the impact of this virus on people and non-poultry livestock is likely to be minimal.

The first signs might be the death of seabirds or marine mammals. While perhaps not as iconic as a kiwi or kākāpō, New Zealand is home to a great many seabirds found nowhere else on the planet.

Some species, such as tara iti (or fairy tern) are critically endangered, with only about 50 individuals left. A virus such as this could directly drive the extinction of species with such low numbers.

Given this risk, the US took action to vaccinate the Californian condor against avian influenza – but only after finding 21 dead condors (4% of the remaining population) which had tested positive for the H5N1 strain.

What should New Zealand watch for and how can we be better prepared to detect any incursions early?

Raising awareness: unexpected deaths in animals are a red flag. Usually, such events are investigated by the Ministry for Primary Industries. But we must better inform the public about what to do if they spot a dead bird or sea lion.

Testing: ramp up active and targeted surveillance of known pathogens. Wild birds have been surveyed annually since 2004 for avian influenza. However, since 2010 the focus has shifted away from migratory birds to sampling resident wildfowl in the summer months, concentrating on a small number of coastal locations visited by migratory shorebirds. This is based on the lack of positive samples from migratory bird prior to 2010, but the global situation and consequences of an incursion warrant revisiting active migratory bird surveillance across more locations.

Genomics: use the viral genomics capabilities we have already established during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Europe, for instance, there are some circulating variants of avian influenza that seem to better infect mammals. If the virus arrives here, viral genomics can be used effectively to let us know what form we are dealing with, and inform our response.

It is clear that to first spot and then stop a virus such as this, we need to look at the entire ecosystem – that is, where humans, animals and the environment are interconnected. This is known as the “One Health” approach.

While this makes intuitive sense, the reality is that disease surveillance affecting humans, domestic animals and wildlife is largely siloed and under-resourced. There is limited integration of activities across these domains. The result is that we are currently ill-equipped to track and respond rapidly to this deadly virus were it to arrive in New Zealand.

We are advocating defragmentation of our surveillance for emerging pathogens. It is time to provide a more enhanced and integrated One Health surveillance system, involving expertise across universities, research institutes and government departments to re-evaluate our pandemic (and panzootic) preparedness.![]()

Jemma Geoghegan, Professor and Webster Family Chair in Viral Pathogenesis, University of Otago and Nigel French, Distinguished Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Public Health, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Montana youth win unprecedented climate case: What does this ruling mean for Canada?

On Aug. 14, a Montana court delivered what is being hailed as a game-changing ruling in a much anticipated youth-led climate change case, Held v. State of Montana.

The Montana First Judicial District Court ruled that the state’s energy policy forbidding the government from considering the impacts of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and climate change in its environmental decision-making violates the state constitution’s fundamental “right to a clean and healthful environment.”

The court’s decision is a resounding victory for the 16 youth plaintiffs and their legal team. Michael Gerrard, founder of Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change (who was not involved in the case), said that “I think this is the strongest decision on climate change ever issued by any court.”

That said, the court stopped short of requiring the state to develop a supervised GHG emissions reductions plan.

The Montana state government issued a fiery response to the ruling and has signalled its intention to appeal, which will send the case to the state Supreme Court. However, regardless of how events play out in Montana, one question stands out: What are the implications of this ruling here in Canada and around the world?

Express And Implied Rights

The legal landscape here in Canada is, unsurprisingly, quite a bit different from the United States. Specifically, The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms does not include a green amendment like Montana’s; indeed, the Charter has not been amended once since its enactment in 1982.

Consequently, rights-based climate litigation in Canada requires the judiciary to interpret other Charter rights — particularly Section 7’s right to life, liberty and security of the person, and Section 15’s right to equality — as naturally and necessarily encompassing a right to a clean and healthy environment.

A number of Canadian environmental law scholars argue forcefully that even though Canada’s Charter is silent on the need to protect the Earth’s critical life-support systems — clean air, water and a stable climate — the rights to life, equality and security of the person will be meaningless on a dying planet and therefore must be interpreted with reference to ecological sustainability.

Indeed, the core argument advanced in the ongoing youth climate case in Canada, La Rose v. His Majesty the King, is that the federal government has a constitutional duty to protect Canadian youth and future generations from climate change. A decision by the Federal Court of Appeal in the La Rose case is expected soon.

If the youth plaintiffs prevail, the case will proceed to a trial. If the court rules in favour of the federal government, the youth plaintiffs will almost certainly appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The Montana decision, however, as strong an endorsement as it is of climate science and renewable energy alternatives to fossil fuels, will not likely assist the youth plaintiffs in the La Rose case. The Montana decision is legally distinguishable because its constitution includes an express — as opposed to an implied — right to a clean and healthful environment.

The same goes for Canadian arguments advancing the common law public trust doctrine, which is already expressly codified in the Montana Constitution.

A Constitutional Challenge

The other key climate law case in Canada is the Supreme Court of Canada’s pending decision in Alberta’s constitutional challenge to the federal Impact Assessment Act. Here, too, the Montana decision is a sobering reminder of the limitations of constitutional litigation when it comes to advancing climate policy.

If the Montana decision stands, state agencies will have the discretion to consider GHG emissions and climate change when reviewing energy projects. But as the Supreme Court of Canada case illustrates, the key question is not whether climate change is considered, but how.

After all, Canada approved the Bay du Nord offshore oil project under the Impact Assessment Act, contrary to Alberta’s claims that the “no more pipelines law” will block future fossil fuel development.

Beyond Symbolism

But that does not mean that the Montana decision is merely a symbolic victory. It’s a strong vindication of independent scientific expertise and its relevance to climate and energy policymaking.

The Montana decision also reaffirms the potential of collective action and collaboration among youth, environmental lawyers, and climate change scholars.

The Montana court joins other courts around the world in highlighting the problem of delaying climate action, which requires youth and future generations to make even faster, more radical and more expensive emissions reductions down the road.