inbox and environment news: Issue 600

October 8 - 14, 2023: Issue 600

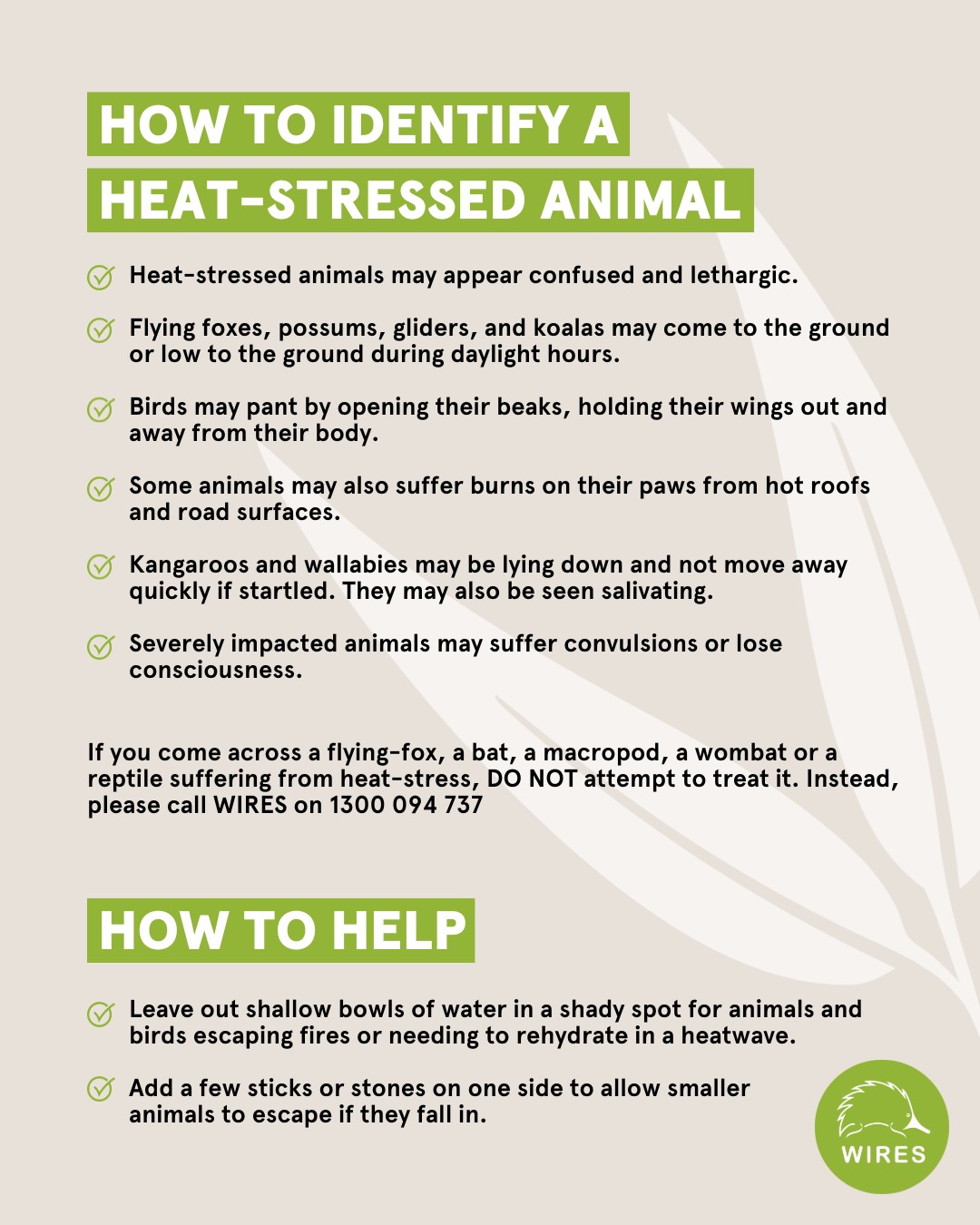

Please Look Out For Wildlife During This Spring Heat

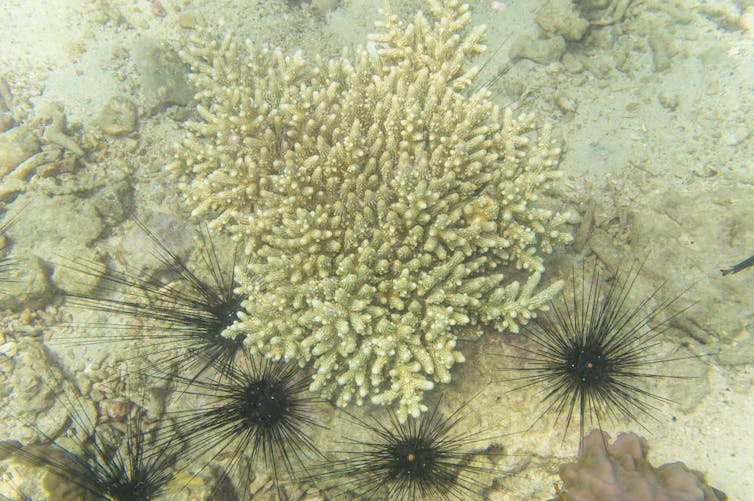

Summer 2023 Snorkelling

Picnic For Nature

Bushwalk Fundraiser

- Friday 10 November

- Friday 8 December

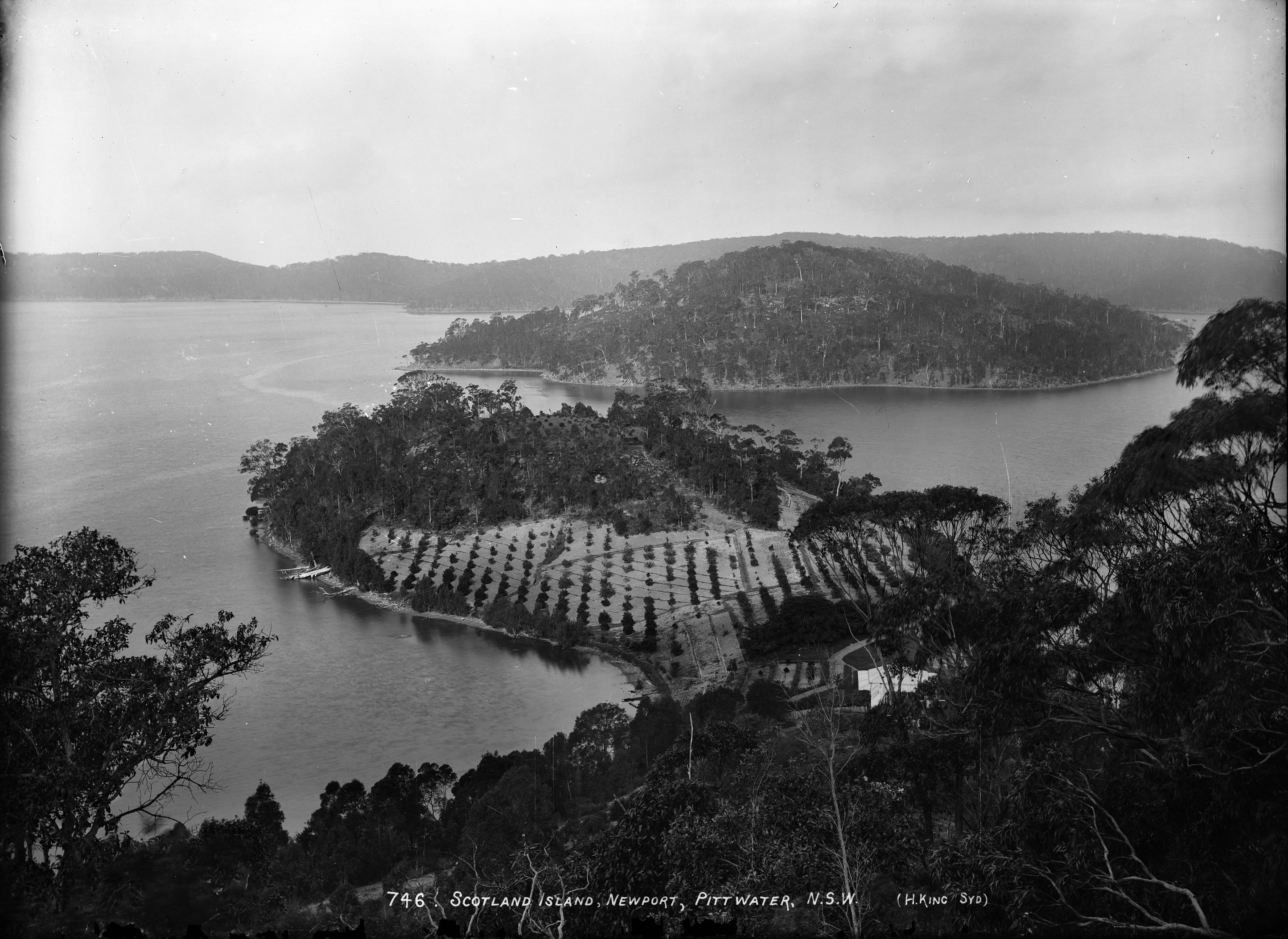

'Scotland Island, Newport, Pittwater, N.S.W.', photo by Henry King, Sydney, Australia, c. 1880-1886. and section from to show cottage on neck of peninsula at western end with no chimneys through roof. From Tyrell Collection, courtesy Powerhouse Museum

𝗞𝗶𝗺𝗯𝗿𝗶𝗸𝗶 𝗥𝗲𝘀𝗼𝘂𝗿𝗰𝗲 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗼𝘃𝗲𝗿𝘆 𝗖𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗿𝗲 𝗶𝗻𝘃𝗶𝘁𝗲𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗺𝘂𝗻𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝘁𝗼 𝗼𝘂𝗿 𝗢𝗽𝗲𝗻 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟮𝟬𝟮𝟯 𝗮𝘁 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗛𝗨𝗕 - 𝗞𝗶𝗺𝗯𝗿𝗶𝗸𝗶.

Highlighting the four resident not-for-profit organisations: Peninsula Seniors Toy Recyclers, Bikes4Life, Boomerang Bags Northern Beaches - Kimbriki, Reverse Garbage and their dedicated volunteers.

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group Begins

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

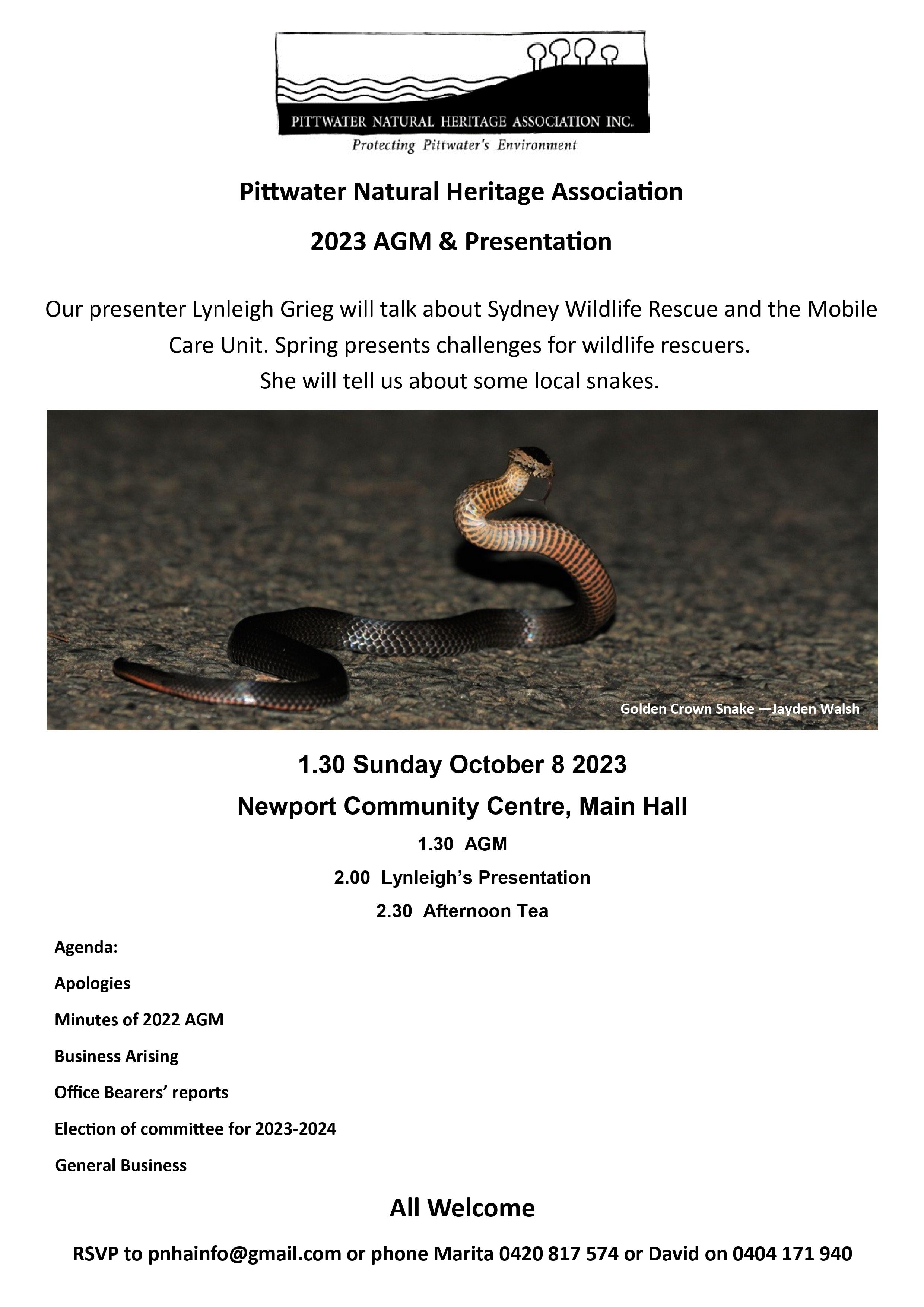

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Next Rescue And Care Course Commences October 28

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

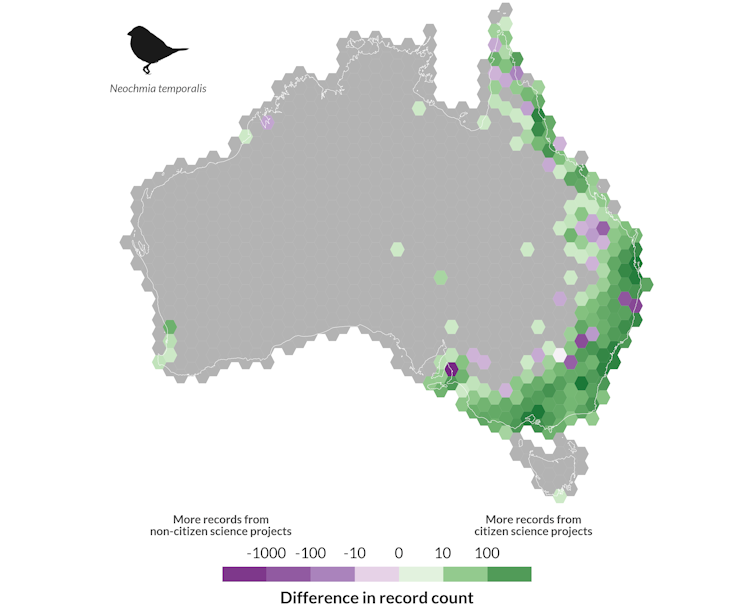

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

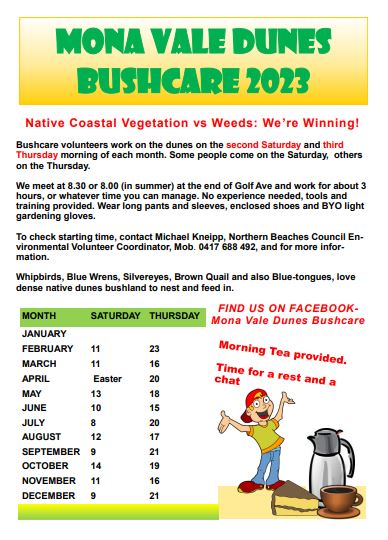

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Critically Endangered Swift Parrot Detection Near NSW Boggabri Coal Mine Sites

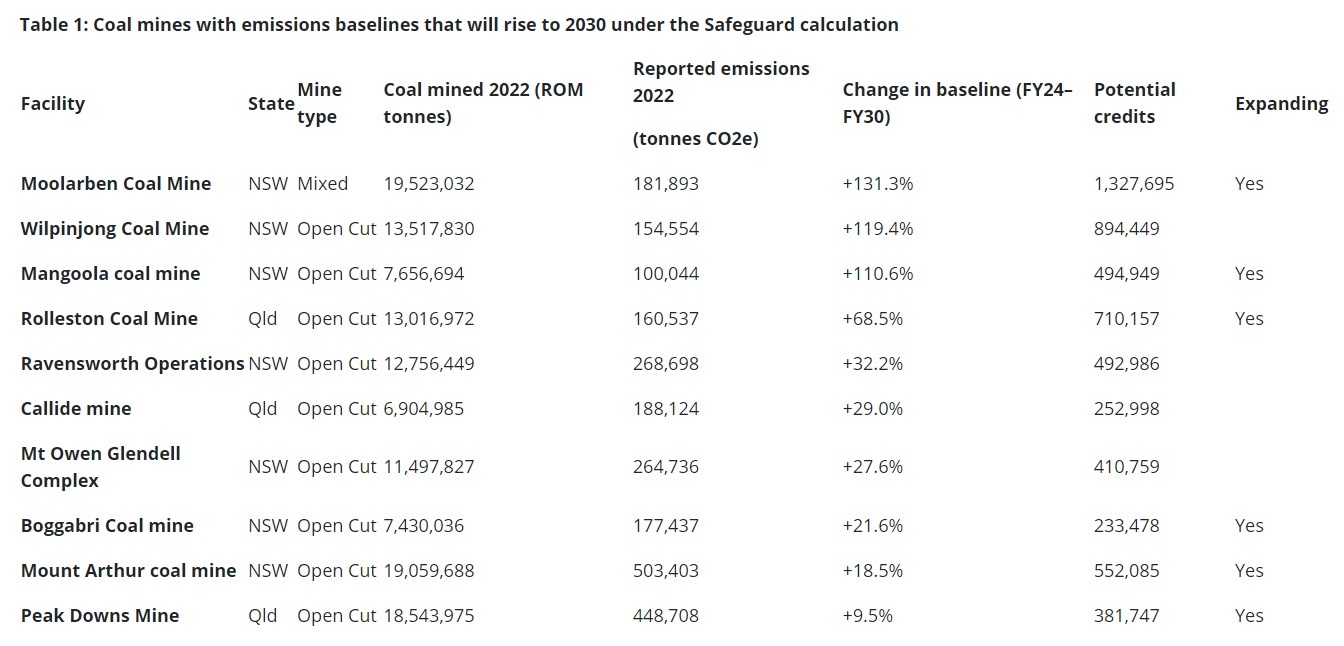

Ten Big Coal Mines Can Increase Emissions Under Safeguard Mechanism: New Analysis

Woodside’s Seismic Blasting Approval Thrown Out After Legal Challenge By Traditional Custodian Intent On Saving The Songlines

''Australia’s reputation among international investors centres on its ability to provide certainty and stability, both of which are important for our global competitiveness and valued long-term relationships with international customers and investors.Important energy projects which are following the rules, consulting in good faith and being granted approvals by the regulator are being impacted because unclear regulations and the application of them are effectively changing the goal posts. The time delays and costs incurred are substantial.More obstacles are being put in the way of critical energy developments, risking the new supply needed to deliver domestic energy security, emissions reductions and substantial economic returns for Australians.Comprehensive and effective consultation with Traditional Owners and landholders has been an important part of the work of Australia’s oil and gas industry going back decades.Regulations which provide clarity and certainty for industry while maintaining consultation obligations are desperately needed.Governments must make clear regulations for consultation that maintain high standards of consultation with stakeholders, including Traditional Owners, but also provide regulatory certainty when an approval is granted.Investors in Australia’s resources sector face increasing approvals uncertainty after today’s court decision, compounding the uncertainty stemming from last year’s decision against a regulatory approval for the Santos Barossa Project.''

Bass Strait Gas Explorer Aims To Seismic Blast Whale Breeding Grounds-National Parks

Federal Government Urged To Rein In Coal Mine Approvals On BHP’s Caval Ridge Horse Pit

- Mine 15 million tonnes of coal each year until 2055 - 20 years beyond the mine’s current lifespan.

- Leave a 545 hectare coal pit, meaning the majority of disturbed land will not be rehabilitated at all.

- Clear important native vegetation that supports threatened species like the ornamental snake, squatter pigeon, and king bluegrass.

National Industries And Governments Decide To Transition The Varroa Mite Program From Eradication To Management

Australia has officially given up on eradicating the Varroa mite. Now what?

The federal government body in charge of pest control has announced Australia will abandon efforts on eradicating the Varroa mite.

This parasitic mite (Varroa destructor) lives in honey bee colonies, feeding on pupae and adult bees. The mites spread viruses, impair the bees’ ability to fly and communicate, and makes them more susceptible to pesticides, eventually causing a colony collapse if left unmanaged.

Until recently, Australia remained free of Varroa thanks to stringent biosecurity measures. But in June 2022, the mite was detected in the New South Wales coastal area near Newcastle and has continued to spread.

A recent increase in detections over a greater area has now made eradication technically unfeasible. As a result, Australia is transitioning from eradication to management of the Varroa mite.

Can We Fight The Mite?

It has been a tough time for beekeepers, the broader beekeeping community and the growers of crops relying on honey bees for pollination.

Varroa mite is already causing significant economic damage to livelihoods, due to restrictions on hive movements and the euthanasia of around 30,000 bee colonies.

To manage it, we will need to learn from overseas, where people have lived with Varroa for decades. However, Australia also has to develop its own solutions because of our unique climate, biodiversity and agricultural systems.

As seen in other countries, honey production and hive numbers may remain relatively stable. But beekeepers will need to invest significant time and resources to monitor, manage and replace hives due to Varroa losses.

There are effective chemical control options, but these cannot eliminate the mites completely. They also have impacts on bees and can leave residues in hive products. Over-reliance on synthetic chemicals will rapidly lead to resistance in Varroa populations, as seen in almost every country Varroa exists.

Effective organic and non-chemical treatments exist, but they are comparatively labour intensive – an additional burden on certified organic beekeepers.

To keep Varroa mite numbers below economically damaging thresholds, beekeepers will need to use integrated pest management solutions – a combination of approaches to reduce mite populaitons, while following up to ensure these appraoches have been effective.

Beekeeping Will Become More Complex And Expensive

Costs for the average-sized Australian bee business could increase by as much as 30%. Experience in other countries suggests there will be significant declines (up to 50%) of hobbyist and semi-commercial operators. Currently, recreational beekeeping is worth A$173 million in Australia annually.

We also know Varroa will progressively kill around 95% of Australia’s feral honey bees within approximately three years. Therefore, we will likely need more bee colonies per hectare to pollinate some crops effectively.

Cumulatively, increased costs of production, a decrease in the numbers of beekeepers and fewer feral bees will likely result in higher demand for bee hives to service 35 pollination dependent industries across the country. As seen in Aotearoa New Zealand, where the Varroa mite established in 2000, prices for bee hives rented to growers increased by 30–100% per hive within five years..

What Should Australia Do To Minimise The Impact?

We need a national program in Australia that monitors colony losses so we can quantify the impacts across the sector. This also holds true for Australian native bees which play an important role in pollination of tropical crops – we do not have the monitoring and baseline data needed to evaluate the changes about to occur.

As an industry that contributes more than $14.2 billion to the economy, we now have a critical need for national capacity building for beekeeping, Varroa and pollination research, development and training.

Western Australia and Tasmania have significant opportunities to remain free from Varroa for as long as possible because the mite is currently only in NSW on the eastern boarder. Restricted movements of honey bees across the Bass Strait and the Nullarbor offer an additional biosecurity buffer.

Australia also remains free from virulent bee viruses, such as the deformed wing virus. Hopefully, the Varroa incursion will lead to strengthened biosecurity for honey bee pests and diseases we do not have in the country yet, like Tropilaelaps mites.

We also need to strengthen compliance with the honey bee biosecurity code of practice and improve monitoring of bee losses, bee viruses and native bees. In the long term, we will need to establish breeding programs for bees with Varroa tolerance, as seen in other countries such as the United States, New Zealand and Hawaii.![]()

Cooper Schouten, Project Manager - Bees for Sustainable Livelihoods, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

6 reasons why global temperatures are spiking right now

The world is very warm right now. We’re not only seeing record temperatures, but the records are being broken by record-wide margins.

Take the preliminary September global-average temperature anomaly of 1.7°C above pre-industrial levels, for example. It’s an incredible 0.5°C above the previous record.

So why is the world so incredibly hot right now? And what does it mean for keeping our Paris Agreement targets?

Here are six contributing factors – with climate change the main reason temperatures are so high.

1. El Niño

One reason for the exceptional heat is we are in a significant El Niño that is still strengthening. During El Niño we see warming of the surface ocean over much of the tropical Pacific. This warming, and the effects of El Niño in other parts of the world, raises global average temperatures by about 0.1 to 0.2°C.

Taking into account the fact we’ve just come out of a triple La Niña, which cools global average temperatures slightly, and the fact this is the first major El Niño in eight years, it’s not too surprising we’re seeing unusually high temperatures at the moment.

Still, El Niño alone isn’t enough to explain the crazily high temperatures the world is experiencing.

2. Falling Pollution

Air pollution from human activities cools the planet and has offset some of the warming caused by humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions. There have been efforts to reduce this pollution – since 2020 there has been an international agreement to reduce sulphur dioxide emissions from the global shipping industry.

It has been speculated this cleaner air has contributed to the recent heat, particularly over the record-warm north Atlantic and Pacific regions with high shipping traffic.

It’s likely this is contributing to the extreme high global temperatures – but only on the order of hundredths of a degree. Recent analysis suggests the effect of the 2020 shipping agreement is about an extra 0.05°C warming by 2050.

3. Increasing Solar Activity

While falling pollution levels mean more of the Sun’s energy reaches Earth’s surface, the amount of the energy the Sun emits is itself variable. There are different solar cycles, but an 11-year cycle is the most relevant one to today’s climate.

The Sun is becoming more active from a minimum in late 2019. This is also contributing a small amount to the spike in global temperatures. Overall, increasing solar activity is contributing only hundredths of a degree at most to the recent global heat.

4. Water Vapour From Hunga Tonga Eruption

On January 15 2022 the underwater Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcano erupted in the South Pacific Ocean, sending large amounts of water vapour high up into the upper atmosphere. Water vapour is a greenhouse gas, so increasing its concentration in the atmosphere in this way does intensify the greenhouse effect.

Even though the eruption happened almost two years ago, it’s still having a small warming effect on the planet. However, as with the reduced pollution and increasing solar activity, we’re talking about hundredths of a degree.

5. Bad Luck

We see variability in global temperatures from one year to the next even without factors like El Niño or major changes in pollution. Part of the reason this September was so extreme was likely due to weather systems being in the right place to heat the land surface.

When we have persistent high-pressure systems over land regions, as seen recently over places like western Europe and Australia, we see local temperatures rise and the conditions for unseasonable heat.

As water requires more energy to warm and the ocean moves around, we don’t see the same quick response in temperatures over the seas when we have high-pressure systems.

The positioning of weather systems warming up many land areas coupled with persistent ocean heat is likely a contributor to the global-average heat too.

6. Climate Change

By far the biggest contributor to the overall +1.7°C global temperature anomaly is human-caused climate change. Overall, humanity’s effect on the climate has been a global warming of about 1.2°C.

The record-high rate of greenhouse gas emissions means we should expect global warming to accelerate too.

While humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions explain the trend seen in September temperatures over many decades, they don’t really explain the big difference from last September (when the greenhouse effect was almost as strong as it is today) and September 2023.

Much of the difference between this year and last comes back to the switch from La Niña to El Niño, and the right weather systems in the right place at the right time.

The Upshot: We Need To Accelerate Climate Action

September 2023 shows that with a combination of climate change and other factors aligning we can see alarmingly high temperatures.

These anomalies may appear to be above the 1.5°C global warming level referred to in the Paris Agreement, but that’s about keeping long-term global warming to low levels and not individual months of heat.

But we are seeing the effects of climate change unfolding more and more clearly.

The most vulnerable are suffering the biggest impacts as wealthier nations continue to emit the largest proportion of greenhouse gases. Humanity must accelerate the path to net zero to prevent more record-shattering global temperatures and damaging extreme events.![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Net zero by 2050? Too late. Australia must aim for 2035

This year’s heightened drumbeat of extreme weather shows us how little time we actually have to slash emissions.

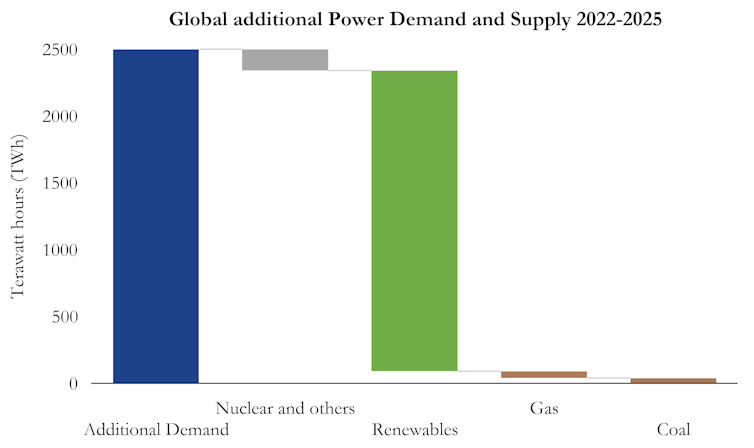

It is now clear that going slow on cutting greenhouse gas emissions is much more expensive than taking action. At this week’s climate ambition summit, United Nations secretary general António Guterres warned the world is “decades behind” in the transition to clean energy.

The UN’s new Global Stocktake makes clear we need to accelerate the race to net zero.

It’s time to act as quickly as humanly possible. This week, Australia’s leading engineers and technology experts from the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering have called for Australia to get to net zero 15 years quicker than our current goal of 2050 to be more consistent with a 1.5℃ trajectory.

It will be hard. But ask yourself – what is the alternative?

To shake us out of business as usual, we have to fast-track regulatory change, upskill the workforce, future-proof national infrastructure, embed a zero-waste approach to supply chains and massively boost business investment. Here’s how.

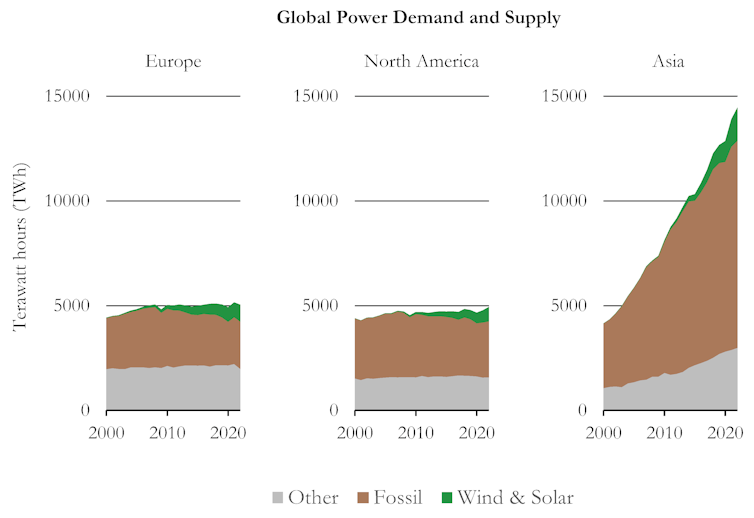

The Net Zero Grid

Per capita, Australia is the world leader in solar and wind generation. But we’ll need more as we electrify the entire economy, which will triple demand.

To get there means investing in distribution, transmission, battery and pumped hydro storage and grid integration. All of this has to be fast-tracked through closer engagement with communities and streamlined regulations.

Electrifying our export industries is vital for both Australia’s and the world’s net zero efforts. This would make full use of our advantages in cheap power from renewables such as by making green hydrogen, which can help with green chemical and green metals manufacturing.

Pulling carbon dioxide back out of the air is another potential “export” industry. Direct air capture will be needed to bring levels in the atmosphere back down, and Australia could use cheap renewable energy to do it, and sell the credits to offset hard-to-abate areas such as plane flights.

Embrace The Circular Economy

Supply chains of products and raw materials put out emissions at every step along the way. Some emissions are from activities in Australia, others overseas. But all end up in the atmosphere.

Fixing this means slashing waste and removing emissions at every stage of production, from raw materials to recycling. Our food systems produce an estimated 29% of global emissions but around 30–40% of food is wasted.

But it’s more than that. The end goal must be embracing a circular economy, where overconsumption is phased out and waste becomes the feedstock for new products. We can greatly accelerate our efforts by working with European authorities, given they are far ahead of Australia here.

Make Our Buildings Run Cleaner

Emissions from our buildings come largely from electricity and gas use, with embodied emissions from, say, the use of concrete in construction a smaller concern. Here, the low-hanging fruit is moving to zero-emissions electricity and switching from gas to electricity.

Banning new household connections to the gas network as Victoria and the ACT are doing, is another opportunity.

When gas heaters reach their end of life, we can require they be replaced by electric heaters. This won’t significantly increase the grid demand if high efficiency heat pumps are used.

And we should boost efficiency standards still further for new buildings and major renovations. Australia’s new National Construction Code will help, but more can be done.

In the longer term, cement made without emissions and new construction methods will help further cut emissions.

Electrify Transport

After a slow start, electric cars are finally gaining popularity in Australia. Now we’re seeing electric utes and trucks. Electric buses are already on the roads in some states. This is essential. Now it’s time to speed it up.

We need all states and territories on board to plan for a phase-out of internal combustion engines, coupled with better investment in public and private charging infrastructure.

Electrifying transport will give us enormous battery packs in our driveways – often several times the capacity of a home battery. New technologies such as vehicle-to-grid will let us use our cars as grid backup and give households security if there’s a blackout.

Shipping giants are working on the challenge of cleaning up emissions, while work is being done on electric planes. These are harder nuts to crack, but already there are electric ferries up and running in Europe and short-trip electric planes on sale in Australia.

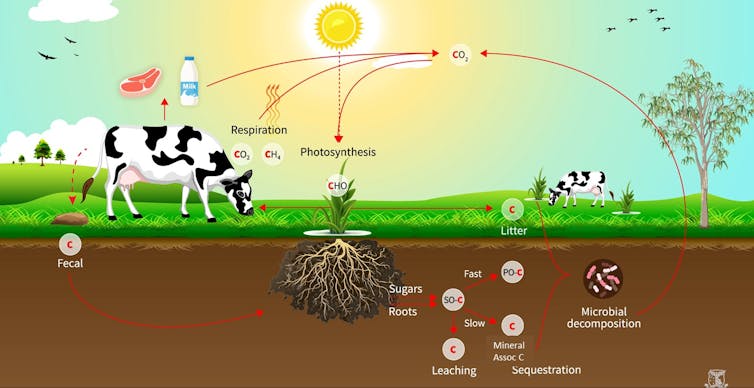

Farming And Mining

Some farms are already running on solar and storage for cost and energy security reasons. But there’s more to do, such as slashing emissions of the potent greenuouse gas nitrous oxide from fertilisers using nitrification inhibitors.

In mining, some operators are rapidly cleaning up their operations – and often for cost reasons. Running a mine site on diesel is expensive. We need to accelerate the shift here towards powering grinding machines, excavators and ore trains with renewables.

Some problems don’t yet have off-the-shelf solutions, such as reducing methane from livestock or producing steel cost-effectively without using coal.

These hard-to-cut sources of emissions will need significant and sustained investment to produce practical and cost-effective technologies solving the problems.

Technology – And Talking

Swapping fossil fuels for clean technologies will take talking as well as technology. Many of us find change confronting, especially at this pace.

So we need to do this right, sharing economic benefits and preserving the social fabric of communities and avoiding damaging nature. The debate over new transmission lines is a case in point.

We’ll need an honest national conversation – and one that isn’t limited to expert, government and industry circles.

We have new institutions to help us move faster, such as the Net Zero Authority, the new mandates for the Climate Change Authority, and the sector-level net zero plans in progress.

Now we need to get on and do it. Yes, it’s faster than we thought possible. But fast is now necessary.![]()

Mark Howden, Director, ANU Institute for Climate, Energy and Disaster Solutions, Australian National University; Frank Jotzo, Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy and Head of Energy, Institute for Climate Energy and Disaster Solutions, Australian National University; Ken Baldwin, Inaugural Director, ANU Grand Challenge, Zero-Carbon Energy for the Asia Pacific, Australian National University; Kylie Catchpole, Associate Professor of Solar Engineering, Australian National University; Kylie Walker, Visiting Fellow, Australian National University, and Lachlan Blackhall, Entrepreneurial Fellow and Head, Battery Storage and Grid Integration Program, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Emperor penguins face a bleak future – but some colonies will do better than others in diverse sea-ice conditions

The long-term future looks bleak for Emperor penguins, but our new research shows some birds may be able to survive in certain conditions, depending on where they live, at least for the next few decades.

Over the past two years, Antarctic sea ice has declined dramatically, prompting scientists to suggest it could reach a “new state”.

A study based on satellite images shows that sea ice broke out early in Antarctica’s Bellingshausen Sea in 2022, potentially resulting in breeding failures across several Emperor penguin colonies in that region.

Our research shows Emperors form colonies in surprisingly diverse environmental conditions that vary depending on location around the continent. Within each of these regions, there is little difference between where birds make their homes and other sites, suggesting they could shift if they had to. This provides a ray of hope in an otherwise bleak outlook.

Emperor penguins may be the only birds to rarely set foot on land. They are unique among penguin species in that they breed on sea ice during the harsh Antarctic winter.

We know that they need “fast ice” – the coastal sea ice attached to the Antarctic continent or ice shelves. But they actually inhabit a range of fast-ice locations that differ in the timing of ice formation, how much ice forms and breaks, and even how close they get to other penguin species.

Depending on where they are along the Antarctic coast, Emperors make use of the habitat available to them. Their behaviour may be flexible enough to allow some colonies to cope better in a warming world.

Why Fast Ice Is Important

Emperor penguins rely on fast ice as a stable platform for their breeding season. Female Emperors lay their eggs and the males incubate them for about two and a half months.

Even though Antarctica’s sea ice is diminishing, this refers to a measure known as “sea ice extent”, which includes all sea ice covering the polar ocean, whether it is fast ice or drifting pack ice.

A decrease in sea ice extent is not necessary linearly linked to a drop in the area covered by fast ice (although the reverse is true).

If fast ice were to disappear, we would expect more than 90% of Emperor colonies to become functionally extinct by the end of the century. However, our study suggests that in the short to medium term, we should consider the differences in the penguins’ breeding habitats when we think about ways to protect them.

Emperors Are Unlikely To Move Far

By looking a little closer at different fast-ice habitats, we found Emperor penguins have certain preferences. The persistence of the ice (how long it lasts into the summer) was important because chicks had more time to develop their water-proof swimming feathers.

In some cases, being close to Adélie penguins made a difference. In other cases, Emperors preferred sites with shallow ocean depths below the colony.

Our results suggest that two of these habitat conditions support larger colonies: stable fast ice that lasts throughout the breeding season (with only small changes in the growth and retreat seasonal cycle) and a good balance between a fast-ice platform that is wide enough to raise chicks but close enough to the ocean to get food for them.

We need further studies to clarify these links and the relationship between population size and habitat quality. In our study, we weren’t able to consider prey availability and there may be other factors that play an important role.

Previous research has already shown that Emperor penguins have limited capacity to disperse to find more suitable climate refuges. This is supported by the genetic partitioning among the penguin populations in different Antarctic regions we studied.

It is therefore unlikely Emperors would move far to avoid more severe climate impacts, even if “better” habitats existed and could host larger colonies.

Protecting Penguin Habitat

Climate change is currently one of the main pressures driving Emperor penguins closer to extinction.

However, the latest global assessment by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) clearly identified fishing activities as historic and current drivers of the erosion of marine biodiversity worldwide.

This is also true for Antarctica. While fishing pressure there is limited to a fraction of the global fishing fleet, some of the largest vessels target krill, a tiny shrimp-like crustacean consumed by many Antarctic predators, including Emperor penguins.

With climate models predicting further reductions in sea ice extent, new fishing grounds could open and amplify pressure on other Antarctic wildlife.

If we want to live in a world with Emperor penguins, the most important thing to do would be to cut greenhouse gas emissions steeply. Another key action could be to prevent fishing in areas where climate change will have the most impact.

In this respect, truly protected areas are one conservation tool at our disposal. Now that our research provides more detailed information about penguin habitats, we can begin the process of more careful planning for conservation.

The world’s largest marine protected area exists in the Ross Sea, which is home to about 25% of the world’s Emperor penguins. Lessons we learn from protection there could help mitigate future declines of Emperors around Antarctica.![]()

Sara Labrousse, Chercheuse en écologie polaire, Sorbonne Université and Michelle LaRue, Associate Professor in Conservation Biology, University of Canterbury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

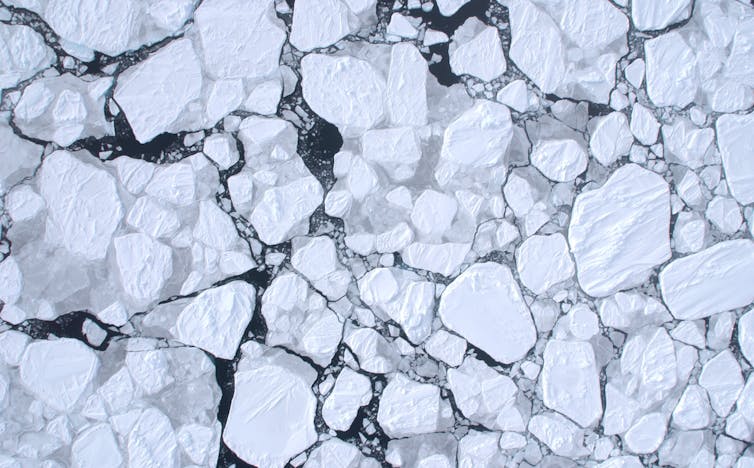

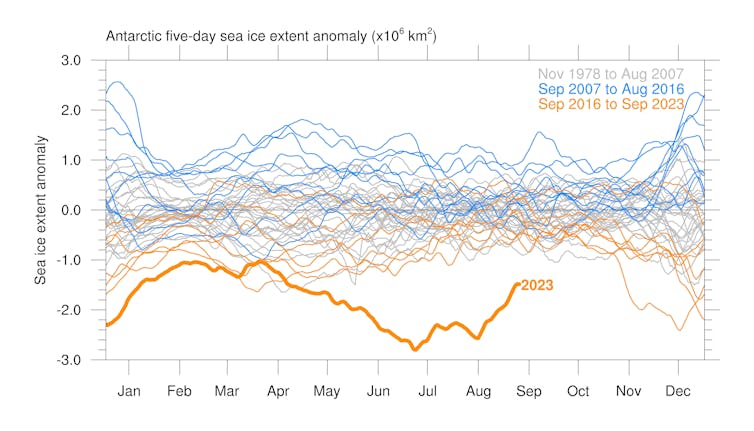

As Antarctic sea ice continues its dramatic decline, we need more measurements and much better models to predict its future

After two seasons of record-breaking lows, Antarctica’s sea ice remains in dramatic decline, tracking well below any winter maximum levels observed since satellite monitoring began during the late 1970s.

A layer of frozen seawater that surrounds the Antarctic continent, sea ice cycles from maximum coverage in September to a minimum in February. The summer minimum has also continued to diminish, with three record low summers in the past seven years.

Some scientists have suggested this year could mark a regime shift for Antarctic sea ice. The consequences could be far-reaching for Earth’s climate, because sea ice keeps the planet cooler by reflecting solar energy back into the atmosphere and insulating the ocean. Its formation also generates cold, salty water masses that drive global ocean currents.

The annual freeze-thaw cycle of Antarctic sea ice is one of Earth’s largest seasonal changes, but is a major challenge for climate models to predict accurately.

Since the 1970s, satellites have been tracking a quantity known as “sea ice extent”, which is the total surface area where at least 15% is covered by sea ice.

This September, it reached a satellite-era record low for this time of year. The previous year, after tracking much lower than the median all winter, Antarctic sea ice extent made a late rally and was 18.3 million square kilometres at its maximum by September 2022, around 2% below the 1981-2010 median.

Although 2% might not sound like much, the following summer biologists reported devastating effects on Emperor penguins. No chicks survived in four out of five breeding sites in one region of sea ice loss.

In 2023, Antarctic sea ice extent started the winter even lower than in 2022, and by the end of July was almost 13% below the 1981-2010 median for that time of year. It reached its maximum extent on September 7, at just under 17 million square kilometres, which is nearly 9% below the 1981-2010 median.

Why We Couldn’t Predict This

Antarctica has bucked the trend of vanishing sea ice observed in the Arctic for decades. Satellite records show a small increasing trend in Antarctic sea ice extent from 2007 to 2016, but this was followed by a decrease since then.

A recent study shows that almost all models in the current collection of simulations used for the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) failed to reproduce the trend in Antarctic sea ice area observed between 1979 and 2018.

Global climate models predicted that Antarctic sea ice extent should have been diminishing for all of that period, which is at odds with the observations.

These models remain our best tools for forecasting future climate. They have been developed since the 1960s to represent the wide range of physical processes of importance to the climate system as realistically as possible.

They are made up of individual component models for the circulation of the atmosphere and oceans, the transfer of solar energy through the atmosphere, land surface properties and the evolution of sea ice.

While these models have generally done well at forecasting ocean and land surface warming over the past few decades, they have struggled to simulate Antarctic sea ice.

Many research groups around the world have investigated the reasons why models have failed to accurately simulate Antarctic sea ice. Changes in wind and wave patterns, natural variability, stratospheric ozone and melt water from the Antarctic ice sheet entering the Southern Ocean have all been proposed as potential explanations.

So far, none of these have proved to be the definitive answer.

Changes In Sea Ice Thickness

The thickness, or depth, of sea ice cannot be measured directly by satellites because it is thin, salty and hidden below a layer of snow of unknown thickness.

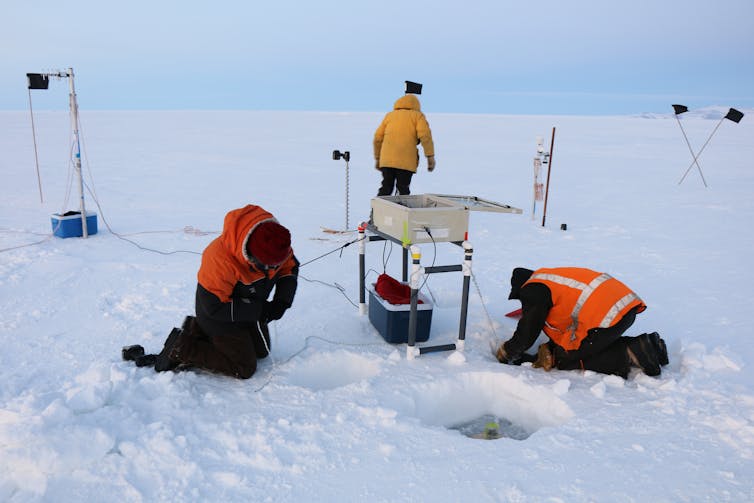

Unlike the Arctic, where we have extensive data from submarines and other sources, information about Antarctic sea ice thickness is very sparse. The data we have mainly come from holes drilled in the sea ice, sea ice monitoring stations, and electromagnetic induction measurements from sleds, helicopters or planes.

The data are mostly from land-fast sea ice, which is the sea ice attached to land or ice shelves.

We have only a few airborne thickness measurements over freely moving pack ice, which makes up most of Antarctic sea ice. We need both sea ice area and thickness to determine sea ice volume, which is important for knowing the overall impact of climate change on sea ice.

Antarctic Storms

McMurdo Sound is a region of the Antarctic coastline in the Ross Sea where both New Zealand (Scott Base) and the USA (McMurdo Station) have Antarctic bases. The sea ice in McMurdo Sound was dramatically thinner than usual in 2022, but not in 2023.

In 2022, multiple storms kept blowing out McMurdo Sound sea ice during winter. Sea ice that would normally be about two metres thick was around 1-1.3 m thick because it was not able to stay in place and grow thicker over the winter season.

Snow was thicker than usual in places, which slowed down the growth of sea ice by insulating it from the cold air above. The weather was not warmer, and the ice had not melted; it had been blown out by strong winds.

This thinner-than-usual sea ice caused major disruptions in Antarctic operations for New Zealand and other countries in 2022. The University of Otago’s automated sea ice monitoring system is installed each year to measure sea ice thickness, temperature and snow depth. In 2022, Scott Base staff had to take the equipment onto the sea ice on foot for the first time because the sea ice was deemed unsafe to drive vehicles on.

Seeing open water in front of McMurdo Station in the middle of winter in 2022 was shocking for us. However, despite the extremely low winter sea ice extent around most of Antarctica in 2023, sea ice in McMurdo Sound formed in a similar way to most years.

It is not yet clear how much climate change has driven the huge anomalies in Antarctic sea ice extent or thickness, but events like these could be a harbinger of things to come.

To have a chance of predicting these changes, we will need dramatically improved modelling capabilities, more measurements of crucial factors driving sea ice change, and new ways of making those measurements.![]()

Inga Smith, Associate Professor in Physics, University of Otago; Andrew Pauling, Research Fellow in Physics, University of Otago; Greg Leonard, Senior Lecturer in Surveying, University of Otago; Maren Elisabeth Richter, Assistant Research Fellow, University of Otago; Max Thomas, Senior Research Fellow, University of Otago; Pat Langhorne, Professor Emerita in Physics, University of Otago, and Wolfgang Rack, Associate Professor for Remote Sensing and Glaciology, University of Canterbury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The social lives of kangaroos are more complex than we thought

Have you ever wondered what a kangaroo’s social life looks like? Well, kangaroos have stronger bonds to one another than you might think.

Over six years, we monitored a population of around 130 eastern grey kangaroos near Wollar in New South Wales to see how their relationships changed over time. Keeping tabs on individual roos led to some surprising results.

We found that kangaroo mothers become more social when caring for joeys (which is the opposite of what we previously thought). We also uncovered new evidence that indicates kangaroos could potentially form long-term relationships.

This research, published in Animal Behaviour, sheds new light on the behaviour of Australia’s most iconic animal.

How To Watch Kangaroos

Eastern grey kangaroos (Macropus giganteus) are found throughout the eastern third of Australia, and they are extremely social animals.

If you’re lucky enough to have some living near you, you’ll notice they are rarely alone. What you might not notice is how often their small groups (called mobs) fluctuate throughout the day.

Kangaroos have a loose “fission–fusion” social structure, which means mobs often split and reform. Knowing this, we wanted to see just how strong kangaroo relationships actually are, and how these relationships changed over several years.

To find out, we spent a few days each year taking photographs of every single kangaroo in our study population. We then used these photographs (all 3,546 of them!) to individually identify each kangaroo.

The best way to tell kangaroos apart (for humans) is the unique shape of their ears, because both the outline of the ears and the inner ear tufts remain very similar throughout the years. New scars can change the overall ear shape, but we were careful to watch out for those.

Using this method, we identified 130 individual kangaroos. We then looked at which kangaroos appeared next to each other in the same photograph to get an idea of what their social groups looked like.

We also gave each kangaroo a social score based on how many other kangaroos they associated with and how “popular” these associates were.

Suprising Sociability

There are usually a couple of difficulties in this sort of long-term animal study, such as identifying individual animals and being able to follow the same population over several years. These problems are easily avoided with kangaroos, as our photographic survey let us identify animals without invasive tagging, and they tend to return to the same place every day.

We could easily look at the short-term and long-term relationships of each kangaroo, as well as how these relationships varied with sex, age and reproduction.

Looking at sociability on an individual level produced some surprising results.

We discovered some kangaroos were just more social than others. In some this was consistent, and in others it changed from year to year.

In fact, we found female kangaroos tended to be much more social in years when they had joeys. This is quite different from earlier research, which suggested kangaroos actually tend to isolate from the rest of the population when they become mothers.

What we think is happening here is that, while mothers tend to spend time in smaller groups (which is what other studies have shown), those groups change often. As a result, mothers associate with more other kangaroos in total – which would account for their high social scores.

So kangaroos’ loose social structure allows them to adjust their sociability with their reproductive state.

Long-Term Friendships?

However, the fact the social structure is loose doesn’t mean it is simple. We found kangaroo relationships might be far more complex than previously thought.

Some of our kangaroos maintained friendships across multiple years, a phenomenon that was particularly common among females. Kangaroos that were more “popular” – as determined by the social score we calculated – were far more likely to have these friendships.

This is the first evidence for long-term relationships in macropods (the animal family that includes kangaroos as well as wallabies, quokkas and others). However, long-term relationships are common in other large, social herbivores such as elephants, giraffes and ibex.

We only looked at the kangaroos for a short time each year. To find out whether they really do form long-term relationships, we will need to do more research. However, we have shown such relationships are a possibility, which is itself a very exciting development in the study of kangaroo behaviour.

The Importance Of Social Organisation

So what’s next? The study of animal behaviour is constantly changing and there’s always lots more we can learn.

We have shown the benefits of looking at animal populations on an individual level, not just a species level. With this in mind, future research should investigate the existence of long-term relationships in kangaroos, as well as why female kangaroos might deliberately increase their sociability when they become mothers.

We often underestimate the importance of social organisation in animals. Further research into kangaroo behaviour can help us better appreciate the intelligence and social complexity of our favourite marsupials.![]()

Nora Campbell, PhD Candidate, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

From glowing cats to wombats, fluorescent mammals are much more common than you’d think

Kenny Travouillon, Western Australian Museum; Christine Elizabeth Cooper, Curtin University; Jemmy Bouzin, Curtin University; Linette Umbrello, Queensland University of Technology, and Simon Lewis, Curtin UniversityRecently, several mammals have been reported to “glow” under ultraviolet (UV) light, including our beloved platypus. But no one knew how common it was among mammals until now.

Our research, published in Royal Society Open Science today, found this glow – known as fluorescence – is extremely common. Almost every mammal we studied showed some form of fluorescence.

We also examined the glow to determine if it was really fluorescence and not some other phenomenon. Then, we tested if the fluorescence we observed in museum specimens was natural and not caused by preservation methods.

We also searched for links between the type and degree of fluorescence and the lifestyle of each species, to gain insights on whether there are any benefits to glowing under UV if you’re a mammal.

Nightclub Lights

Nightclub visitors will be familiar with white clothes, or perhaps their gin and tonic, glowing blue under UV light. This is a great example of fluorescence – when the energy from UV light, which is a form of electromagnetic radiation invisible to humans, is absorbed by certain chemicals.

These chemicals then emit visible light, which is lower-energy electromagnetic radiation. In the case of gin and tonic, this is due to the presence of the quinine molecule in the tonic water.

In the case of animals, this can be due to proteins or pigments in their scales, skin or fur. Fluorescence is quite common among animals. It has been reported for birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, corals, molluscs and most famously scorpions and other arthropods.

However, it has been described less frequently in mammals, although recent studies have provided several examples. We already knew that bones and teeth glow with fluorescence, as do white human hair and nails. Some rodents have a pink glow under UV light and platypuses glow blue-green.

How Often Do Mammals Glow?

Our team came together because we were curious about fluorescence in mammals. We wanted to know if the glow reported recently for various species was really fluorescence, and how widespread this phenomenon was. We obtained preserved and frozen specimens from museums and wildlife parks to study.

We started with the platypus to see if we could replicate the previously reported fluorescence. We photographed preserved and frozen platypus specimens under UV light and observed a fluorescent (although rather faint) glow.

To make sure it was fluorescence and not some other effect that looked like it, we used a technique called fluorescence spectroscopy.

This involved shining various sources of light at the samples and recording the specific “fingerprints” of the resulting glow, known as an emission spectrum. This way, we could confirm what we saw was indeed fluorescence.

We repeated this process for other mammals and found clear evidence of fluorescence in the white fur, spines and even skin and nails of koalas, Tasmanian devils, short-beaked echidnas, southern hairy-nosed wombats, quendas (bandicoots), greater bilbies and even cats.

Both fresh-frozen and chemically treated museum specimens were fluorescent. This meant it wasn’t preservation chemicals such as borax or arsenic causing the fluorescence. So, we concluded this was a real biological phenomenon.

Mammals In Dazzling Lights

Using specimens from the Western Australian Museum’s collection, we took the experiment to the next stage. We recorded every species of mammal that was fluorescent when we exposed the specimens to UV light.

As a result, we found 125 fluorescent species of mammal, representing all known orders. Fluorescence is clearly common and widely distributed among mammals.

In particular, we noticed that white and light-coloured fur is fluorescent, with dark pigmentation preventing fluorescence. For example, a zebra’s white stripes fluoresced while the dark stripes didn’t.

We then used our dataset to test if fluorescence might be more common in nocturnal species. To do this, we correlated the total area of fluorescence with ecological traits such as nocturnality, diet and locomotion.

Nocturnal mammals were indeed more fluorescent, while aquatic species were less fluorescent than those that burrowed, lived in trees, or on land.

Based on our results, we think fluorescence is very common in mammals. In fact, it is likely the default status of hair unless it is heavily pigmented. This doesn’t mean fluorescence has a biological function – it may just be an artefact of the structural properties of unpigmented hair.

However, we suggest florescence may be important for brightening pale-coloured parts of animals that are used as visual signals. This could improve their visibility, especially in poor light – just like the fluorescent optical brighteners that are added to white paper and clothing.![]()

Kenny Travouillon, Curator of Mammals, Western Australian Museum; Christine Elizabeth Cooper, Senior Lecturer, Curtin University; Jemmy Bouzin, PhD candidate, Curtin University; Linette Umbrello, Postdoctoral research associate, Queensland University of Technology, and Simon Lewis, Professor of Forensic and Analytical Chemistry, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

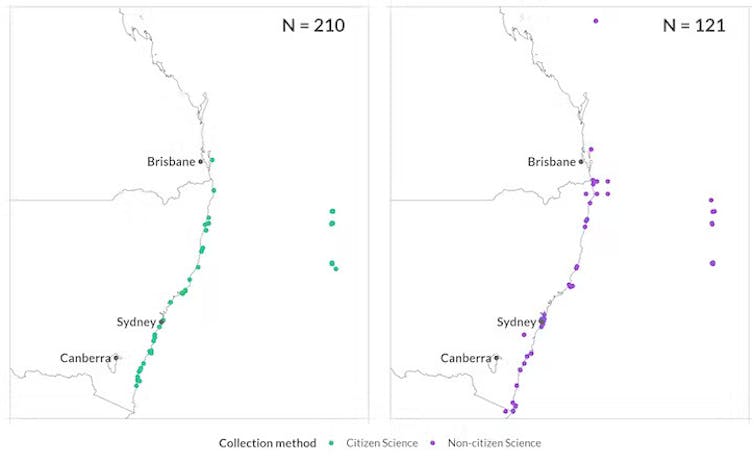

Citizen scientists collect more nature data than ever, showing us where common and threatened species live

Citizen science isn’t new anymore. For decades, keen amateur naturalists have been gathering data about nature and the environment around them – and sharing it.

But what is new is the rate at which citizen scientists are collecting and sharing useful data. Last year, 10 million observations of species were collected. Our new research shows 9.6 million of those came from citizen scientists. It makes intuitive sense. There are only so many professional researchers. But nearly everyone now has a smartphone.

But if anyone can contribute data, how do you know it’s reliable? Was it really an antechinus, or was it a black rat? Despite the growing success in collecting data, there has long been scepticism over how reliable the data are when used to, say, estimate how abundant a threatened species is.

It turns out, citizen science is extremely useful – especially when paired with professionally collected data.

How Did We Test It?

It’s now much simpler and quicker to be a citizen scientist than it used to be. You might take a photo of an unusual mammal you spot at a campground, record your observations, and upload it to an app or website. This, in turn, has helped standardise the data and make it even more useful. Around Australia, thousands of people contribute regularly through platforms like iNaturalist, DigiVol, 1 Million Turtles, FrogID and Butterflies Australia.

When you upload your observation, it’s recorded in the database of the individual app. But data from all major citizen science apps is also shared with the Atlas of Living Australia, Australia’s largest open-source open-access biodiversity data repository.

That’s important, because it means we can aggregate sightings across every app to get a better sense of what’s happening to a species or ecosystem.

To tackle the question of data reliability, we looked at what proportion of total records added to the data repository came from citizen scientists.

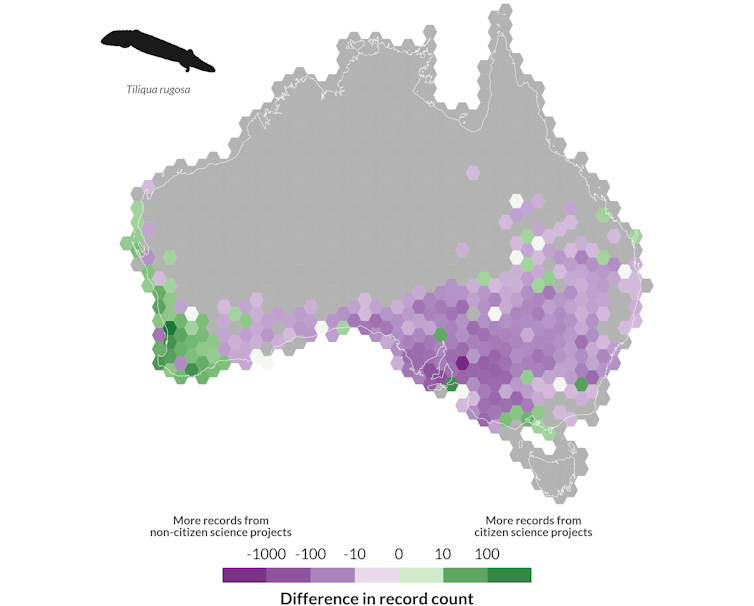

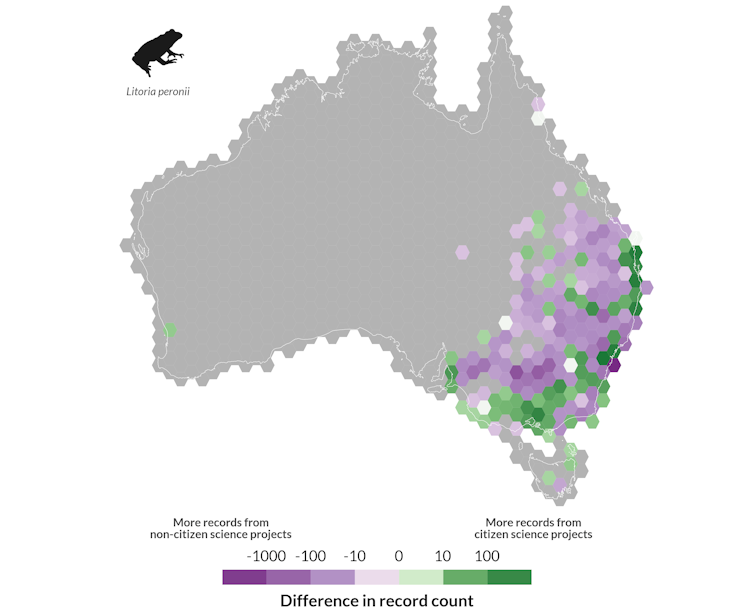

Then we chose three common species – shingleback lizards, Peron’s tree frog, and the red-browed firetail finch – and compared citizen science observations with professionally recorded data across their distribution.

For the shingleback lizard (Tiliqua rugosa), the majority of locations where it was sighted came from professional projects such as government programs and museums, with only 18.5% of locations drawn largely from citizen science.

Peron’s tree-frog (Litoria peronii) had 33.5% of its locations mainly contributed by citizen scientists.

But for the red-browed firetail (Neochmia temporalis), citizen science was the main contributor in over 86.5% of its locations.

Why the difference? We believe it’s due to the impact of long-running citizen science projects driven by enthusiasts. Birders are a large enthusiast community, while people who go herping (looking for reptiles) are a smaller group.

As a reflection of community enthusiasm, birds make up nearly 50% of all species observation records in the Atlas of Living Australia, with the Australian magpie the most commonly recorded species.

What About Rarely Recorded Species?

Next, we looked at several species with fewer than 1,000 records to find out whether citizen science contributes less data when species are less conspicuous.

In fact, the reverse was often true. For some rare species, citizen science is proving invaluable in ongoing monitoring.

Take the threatened black rockcod (Epinephelus daemelii), a large, territorial fish which been decimated by spearfishing and other pressures.

Here, citizen science proved its worth, adding 63% of observations. Most data came from a few high profile projects, such as annual reef and fish surveys.

Citizen Science Is Coming Of Age

For decades, citizen science has struggled to feed data into professional monitoring and conservation efforts.

But this is increasingly unfair. By combining citizen science data with professionally collected data, we can get the best of both worlds – a much richer picture of species’ distributions.

It’s only going to get better, as observation and citizen scientist numbers grow each year. There’s a large spectrum of projects, many with excellent data quality controls in place.

Citizen science has come a long way. The data created by keen amateurs is now of better quality, aided by new technologies and support from researchers.

Apps which add automatic time stamps, dates and locations make it much easier to validate observations.

This suggests there’s untapped potential for citizen science to contribute consistent data over significant parts of many species’ ranges, though the strength of this contribution will vary by species.

There’s still more to do to help citizen scientists contribute as usefully as they’d like to. For instance, observations tend to cluster in the regions around cities, because that’s where citizen scientists live. Citizen scientists can also favour larger, charismatic and brightly coloured species.

One method of improving collection could be to focus the interest of citizen scientists on a wider range of species.

For citizen scientists themselves, a big part of the appeal is the ability to create useful data to help the environment. Citizen scientist Jonathon Dashper, for instance, spends his spare time looking for frogs and recording fish. Why? He told us:

My drive to contribute to citizen science is to further my understanding of the natural world and contribute to decision making on environmental matters. Using citizen science platforms, I have been able to learn so much about harder-to-identify organisms.

Erin Roger, Sector Lead, CSIRO; Cameron Slatyer, Project Manager, Atlas of Living Australia, CSIRO, CSIRO, and Dax Kellie, Science Lead | Data Analyst, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

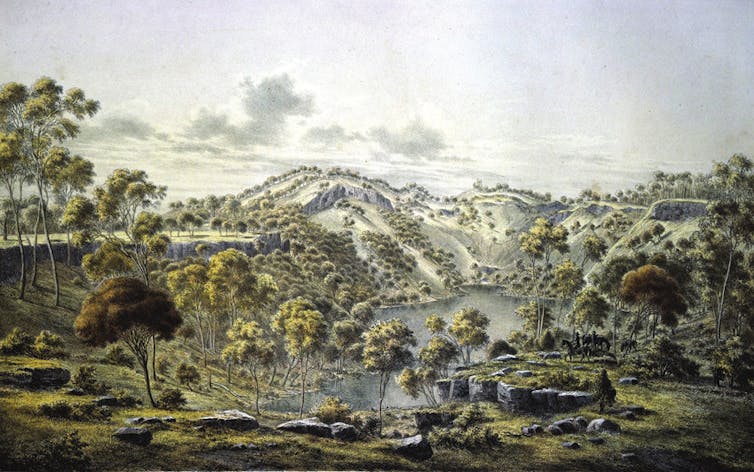

Colonists upended Aboriginal farming, growing grain and running sheep on rich yamfields, and cattle on arid grainlands

First Nations readers are advised this article contains references to colonial violence against First Nations people.

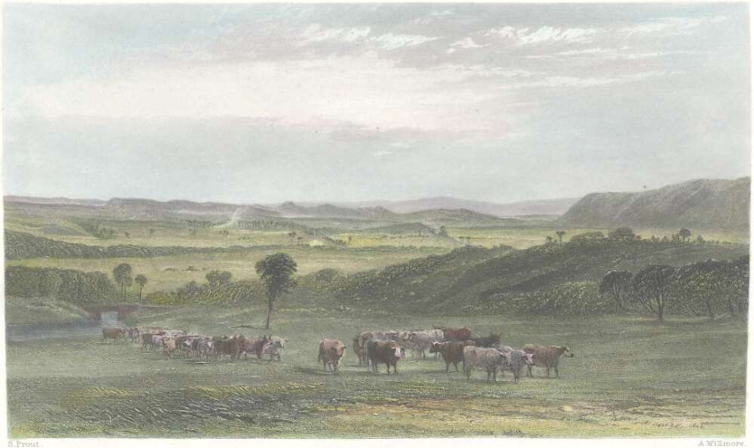

In 1788 the First Fleet brought two bulls and four cows from the Cape of Good Hope and put them on grass on Bennelong Point, where Sydney Opera House is now. But there wasn’t much grass, and it wasn’t much good, so the cattle took off. Seven years later they were found 65 kilometres southwest, on the Cowpastures near Camden, a flourishing herd. By 1820 they were supporting an abattoir and a couple of tanneries.

The cows had found land that was deliberately made for grazing animals – kangaroos. In small patches and on extensive plains, Dharawal managers had performed cool burns to promote rich grass near water. When the cattle found this grass, they stayed.

It was the start of dispossession. Grazing animals trod on or ate the staple tubers such as murnong, on which local groups relied. These grew in rich beds, but were easily trampled. As colonists moved inland, they took Aboriginal land used for growing grain and ran sheep or cattle on it.

The effects of this upheaval are still with us today.

Without Fire, The Trees Took Over

The newcomers who took the Camden country tried to keep it open, without scrub. There, John and Elizabeth Macarthur developed the Australian merino sheep. But they did not understand fire, and the bush got away. As early as 1817, the Macarthurs’ land “had become crowded – choked up in many places by thickets of saplings and large thorn bushes [Bursaria spinosa] and the sweet natural herbage had for the most part been replaced by coarse wiry grasses which grew uncropped”.

In 1848, Thomas Mitchell observed the effects:

The omission of the annual periodical burning by the natives (sic), of the grass and young saplings, has already produced in the open forest lands nearest to Sydney, thick forests of young trees, where, formerly, a man might gallop without impediment, and see whole miles before him. Kangaroos are no longer to be seen there; the grass is choked by underwood.

On good grass, stock fed themselves – they needed only shepherds or stockmen – but European crops grew reluctantly on Sydney sandstone. In 1789, English farmer James Ruse grew corn on better land at Rose Hill near Parramatta, but it still yielded poorly.

In 1794, Ruse sold his block and joined the settlers crowding the rich flats of the Hawkesbury River. Here, he produced the first successful wheat crop.

Soon, corn, English wet wheat and barley were supplying government stores and the Sydney market.

On those Hawkesbury flats, Dharug people had long grown a key staple: tubers. They could not afford to lose the land. They gave some up, but the settlers wanted it all. In 1794, guerilla war broke out. It lasted 22 years – Australia’s longest war – until in 1816 British soldiers finally broke Dharug resistance.

Tubers And Grain

Unlike the newcomers, the Dharug rarely ate grain. They preferred tubers. This was common – wherever it was wet enough, people across Australia relied on tubers, notably warran (Dioscorea hastifolia) in the southwest, and the yam daisy, murnong (Microseris lanceolata) in the southeast.

Women regularly dug over tuber fields to make the soil crumbly, and replanted tuber tops for the next harvest. For mile after mile where they had worked, the ground looked ploughed. At Sunbury, near Melbourne, Isaac Batey, a gardener in England, saw a slope of:

rich basaltic clay, evidently well fitted for the production of myrnongs. On the spot are numerous mounds with short spaces between each, and as all these are at right angles to the ridge’s slope, it is conclusive evidence that they were the work of human hands extending over a long series of years.

In country too dry for tubers – most of Australia – people grew grain, notably native millet (Panicum decompositum). They chose land near water, burned the ground, spread seed, blocked channels to spread water, watched the seasons to know when to return, reaped the crop by pulling or stripping with stone knives, dried, threshed and winnowed the grain, and stored it in skin bags or ground it into flour.

On the Narran River, northwest of Lightning Ridge, the explorer and surveyor Thomas Mitchell observed in 1848:

Dry heaps of this grass, that had been pulled expressly for the purpose of gathering the seed, lay along our path for many miles. I counted nine miles along the river, in which we rode through this grass only, reaching to our saddle-girths.

Dispossession And Reversal

Even allowing for the modern expansion of irrigation in the north, people probably farmed more of Australia in 1788 than we do now.

But we don’t crop the widespread grainlands of the arid interior. We leave them to cattle or camels. Our crops largely grow on tuber country, so a great many tubers have diminished or disappeared. How people use the land has essentially reversed since 1788, based on my research into the subject.

This upended the lives of many species. It let inland birds such as galahs, crested pigeons, and later, little corellas, expand their range. When Europeans arrived, galahs were typically inland birds. Now they’re common from coast to coast. What changed? My research suggests it was colonisation. Galahs feed on the ground. To get at tall inland grasses, they relied on Aboriginal grain cropping before contact. Afterwards, introduced stock shook or trampled grass – and expanded the galah’s range.

But ground-dwelling small and medium-sized mammals and birds declined. Dozens of species became extinct or endangered. The toolache wallaby was gone in less than a century. The lesser stick-nest rat and the paradise parrot disappeared not long after newcomers, their stock, and new predators like cats and foxes invaded their habitats. Today, even the koala is endangered.

Those who had cared for these species – the people of 1788 and after – were devastated by invasion. It’s possible they had more war dead than white Australia’s 103,000 in all its wars.

Survivors were commonly driven or taken from their country, and the land they managed so carefully was made a resource to exploit, or left to burn randomly.

So much was lost. Gone are the stories, the dances, the paintings, the languages of ten thousand campfires, gone knowledge of land, sea and sky, the skill to care for every habitat, to grow local crops and husband native animals, to feel truly at home. ![]()

Bill Gammage, Emeritus Professor, Humanities Research Centre, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We should use Australia’s environment laws to protect our ‘living wonders’ from new coal and gas projects

From Kakadu and the Great Barrier Reef in the North, to the Snowy Mountains in the Southeast, and jarrah and marri forests in the Southwest, Australia is home to incredibly diverse ecosystems. Many of our plants, animals, birds and fish are found nowhere else in the world.

Our First Nations people protected these living wonders through their holistic approach to managing the land and caring for Country for more than 65,000 years. But the European settlers took a different approach and the land suffered.

Federal laws made in 1999 to better protect the environment are failing. Climate change is not explicitly mentioned in the legislation. These shortcomings have prompted a volunteer environment group to mount a legal challenge against federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek “to protect our living wonders from coal and gas”. The matter is currently before the courts.

This week’s new report from the Climate Council Australia (which I was an expert reviewer on) explains the problem with our environment law and charts a way forward.

The fundamental flaw in our national environmental law must be urgently addressed if we are to have any hope of protecting our wildlife and habitat into the future.

Australia’s National Environmental Law

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) should be designed to keep our living wonders safe from harm.

The primary objective of the EPBC Act is to:

provide for the protection of the environment, especially those aspects of the environment that are matters of national environmental significance.

But it’s clear the environment is deteriorating. The EPBC Act requires a comprehensive assessment of Australia’s environment every five years. The latest assessment, published in 2022, found the state of Australia’s environment is poor and getting worse.

Climate change was identified in that assessment as one of the greatest threats to all aspects of the Australian natural environment. Climate change is a compounding factor that increases the impacts of other pressures on our environment, such as land clearing, invasive species, pollution and resource extraction.

However, climate change is not considered directly in the EPBC Act as one of the factors affecting matters of national environmental significance.

According to the Climate Council report, since 1999, 740 new projects to extract coal, oil and gas have been approved or passed, with 555 of them not having undergone detailed environmental assessment. Burning these fossil fuels increases greenhouse gas emissions and makes climate change worse.

In 2020, a scathing independent review of the EPBC Act led by former competition watchdog chair Graeme Samuel found the act is ineffective, outdated and needs comprehensive reform.

Climate Risks To Australia

In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released the most recent comprehensive global assessment of climate change risks.

The special fact sheet about climate impacts on natural and human systems in Australia and New Zealand provides a helpful summary of that assessment.

It lists nine key risks in Australia associated with climate change. Of these, the top five risks for our living wonders are:

“loss and degradation of coral reefs and associated biodiversity and ecosystem service values [what they are worth] in Australia due to ocean warming and marine heatwaves

loss of alpine biodiversity in Australia due to less snow

loss of natural and human systems in low-lying coastal areas due to sea level rise

increase in heat-related mortality and morbidity for people and wildlife in Australia due to heatwaves

inability of institutions and governance systems to manage climate risk”.

That last one is particularly relevant to the EPBC Act.

A Legal Challenge Is Underway

To test the climate blindspot in the EPBC Act, the Environment Council of Central Queensland submitted 19 reconsideration requests to Plibersek in July 2022.

The minister was asked to reconsider the previous evaluation of 19 coal and fossil gas extraction projects under the former government, because they did not take into account potential harms on Australia’s living wonders.

The environment council provided the minister with thousands of state and federal government reports listing the impacts of climate change on several thousand matters of environmental significance.

In November 2022, the minister accepted 18 reconsideration requests as valid. However, in May 2023, the minister decided not to change the climate risk assessments by the previous government for three of the projects she was asked to reconsider. In Plibersek’s official responses she determined that based on the new information provided to her in the reconsideration requests, it wasn’t possible to say the proposals would be a “substantial cause of the stated physical effects of climate change” on a matter of national environmental significance.

The matter is now in the Federal Court. Last week, the environment council challenged Plibersek’s rejection to reconsider two of the three coal mine expansion projects, both in New South Wales. A decision from the judge on this case is pending and should be provided in the next few months. A spokesperson for the minister has advised the media they would not comment “as this is a legal matter”.

Protecting Our Living Wonders Means Fixing Australia’s Environment Law

We need to fix Australia’s national environment law, making sure it contains an explicit objective to prevent actions that accelerate climate change. We need a national environment law that genuinely protects our environment by stopping highly polluting projects and enabling ones that can help us rapidly switch to a clean economy instead.

Every fraction of a degree of avoided warming matters for preserving our environment. Every decision made under our national environment law can either help or hinder the urgent task to drive down greenhouse gas emissions. ![]()

David Karoly, Professor emeritus, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Container deposit schemes reduce rubbish on our beaches. Here’s how we proved it

Our beaches are in trouble. Limited recycling programs and a society that throws away so much have resulted in more than 3 million tonnes of plastic polluting the oceans. An estimated 1.5–1.9% of this rubbish ends up on beaches.

So can waste-management strategies such as container deposit schemes make a difference to this 50,000–60,000 tonnes of beach rubbish?

The Queensland government started a container deposit scheme in 2019. We wanted to know if it reduced the rubbish that washed up on beaches in a tourist hotspot, the Whitsundays region.

To find out, our study, the first of its kind, used data from a community volunteer group through the Australian Marine Debris Initiative Database.

It turned out that for the types of rubbish included in the scheme – plastic bottles and aluminium cans – the answer was an emphatic yes.

Container Deposit Schemes Work

After the scheme began, there were fewer plastic bottles and aluminium cans on Whitsundays beaches. Volunteer clean-up workers collected an average of about 120 containers per beach visit before the scheme began in 2019. This number fell to 77 in 2020.

Not only that, but those numbers stayed down year after year. This means people continued to take part in the scheme for years.

Rubbish that wasn’t part of the scheme still found its way to the beaches.

However, more types of rubbish such as larger glass bottles are being added to the four-year-old Queensland scheme. Other states and territories have had schemes like this for many years, the oldest in South Australia since 1971.

But we didn’t have access to beach data from before and after those schemes started. So our findings are great news, especially as some of these other schemes are set to expand too. The evidence also supports the creation of new schemes in Victoria this November and Tasmania next year.

These developments give reason to hope we will see further reductions in beach litter.

The Data Came From The Community

To find out whether the scheme has reduced specific sorts of rubbish on beaches we needed a large amount of data from before and after it began.

The unsung heroes of this study are the diligent volunteers who provided us with these data. They have been recording the types and amounts of rubbish found during their cleanups at Whitsundays beaches for years.

Eco Barge Clean Seas Inc has been doing this work since 2009. In taking that extra step of counting and sorting the rubbish, they may not have known it at the time, but they were creating a data gold mine. We would eventually use their data to prove the container deposit scheme works.

The rubbish clean-ups are continuing. This means we’ll be able to see how adding more rubbish types to the scheme will further reduce rubbish on beaches.

The long-term perspective we can gain from such data is testament to this sustained community effort.

There’s Still More Work To Do

So if we recycle our plastics, why do we still get beaches covered in rubbish? The reality is that most plastics aren’t recycled. This is mainly due to two problems:

- technological limitations on the sorting needed to avoid contamination of waste streams

- inadequate incentives for people to reduce contamination by properly sorting their waste, and ultimately to use products made from recycled waste.

Our findings show we can create more sustainable practices and a cleaner environment when individuals are given incentives to recycle.

However, container deposit schemes don’t just provide a financial reward. Getting people directly involved in recycling fosters a sense of responsibility for the environment. This connection between people’s actions and outcomes is a key to such schemes’ success.

Our study also shows how invaluable community-driven clean-up projects are. Not only do they reduce environmental harm and improve our experiences on beaches, but they can also provide scientists like us with the data we need to show how waste-management policies affect the environment.

Waste management is a concern for communities, policymakers and environmentalists around the world. The lessons from our study apply not only in Australia but anywhere that communities can work with scientists and governments to solve environmental problems.![]()

Kay Critchell, Lecturer in Oceanography, Deakin University and Michael Traurig, PhD Researcher, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Playful whales can use seaweed as a hat – or exfoliant. This “kelping” behaviour is more common than we realised

If you’re a whale, there’s often not too much to see out in deeper water. Perhaps that’s why so many whales get playful with kelp and other seaweed.

Once might have been chance. But we’ve collected over 100 examples on social media of whales playing with seaweed, known as “kelping”. It’s not just one species – gray whales, southern and northern right whales, and humpback whales all do it.

To date, there’s far more social media and news reports on whale play with seaweed than scientific literature. A 2011 study in New South Wales described these interactions as playful behaviour. Other researchers have documented instances of whales moving logs through the water in Colombia or interacting with jellyfish on the United States east coast.

Our new research compiles data from over 100 kelping events captured on social media. From this, we deduced two things. First, it is playful. And second, it’s likely to have a useful component, such as using the seaweed to scratch an itch (hard without hands), brush off baby barnacles, or flick away whale lice – parasites that drive the whales mad.

How Do Whales Find Kelp – And What Do They Do With It?

Sightings of this behaviour tend to occur in regions where kelp is abundant. That’s no surprise. Kelp is a very strong seaweed and can take the punishment a whale can dish out.

Most videos and photos capturing this behaviour are of humpback whales as they migrate. That’s also not surprising. Humpback whales are one of the most common species. They tend to migrate closer to shore. And they do more activities at the surface compared to other baleen whales, which is why beach goers and whale-watching boats most often see humpback whales.

Until now, kelp play has been documented in Australia, the United States and Canada. But this is likely due to the fact these regions have a larger number of people who do whale-watching and who use social media platforms to share their observations.

Drones have given us a new way of studying this behaviour. In several drone videos, we can see humpback whales actively seeking out seaweed. These interactions aren’t just fleeting – whales can play with it or use it for up to an hour.

During kelping, whales tend to lift the seaweed up and balance it on their rostrum, their flat upper head.

They also seem willing to share their kelp patches with other whales, engaging in cooperative behaviours such as rolling, lifting and balancing the seaweed together.

So is it play? In part, yes. When animal researchers look at a behaviour, it has to meet three criteria to be play. First, it seems voluntary and enjoyable. Second, it’s different to more serious behaviours. It can be exaggerated or deliberately incomplete. And third, the animals don’t seem stressed or hungry, suggesting they’re in good health. Kelping meets all three of these.

For animals, play has long-term benefits such as boosting their coordination and movement skills. Balancing seaweed may also be stimulating for the whales, as their rostrums have fine hair follicles. It could even be ticklish.

Kelping Might Be More Than Just Play

Toying with seaweed might have benefits other than just being fun. Some of us enjoy seaweed wraps at a spa or as a facial mask.

It might be the same for whales. Some seaweed species have been found to reduce bacterial growth, which could be useful for whales, as their skin hosts a range of viruses and bacteria. Whales have to constantly shed their skin to keep on top of bacterial growth.