Inbox and Environment News: Issue 601

October 15 - 21, 2023: Issue 601

Bilgola Plateau Probus Club 1st Birthday

National Immunisation Program – Changes To Shingles Vaccination From 1 November 2023

- people aged 65 years and older

- First Nations people aged 50 years and older

- immunocompromised people aged 18 years and older with medical conditions including:

- haemopoietic stem cell transplant

- solid organ transplant

- haematological malignancy

- advanced or untreated HIV.

Are You Prepared To Manage Older Peoples’ Health During Heatwaves?

- residential aged care

- home and community care.

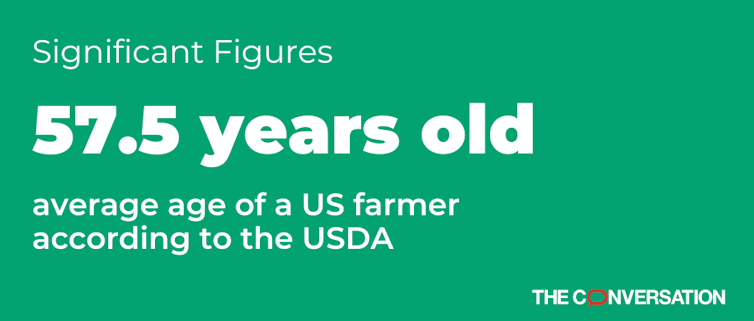

COTA Australia Marks Ageism Awareness Day, Calls For Greater Government Action On Ageism

Campaign Draws Attention To Ageism

- 68% of all over-50s agree “ageism against older people is a serious problem in Australia”. It was 73% for respondents aged 60-69.

- 74% of all over-50s believe Australia is “not doing enough to raise awareness of ageism and fight against it”.

- 58% of over-50s want “a government campaign to raise awareness about ageism and its effects”.

- People in their 60s are the most likely older Australians to have experienced ageism in the past year.

- 36% of over-50s agree with the statement that, “people have assumed I cannot understand or learn new technology”. It was 50% for those aged 90 and over.

- 21% of over-50s say, “People have insisted on doing things for me that I am capable of doing on my own.” It was 35% for over-90s.

- 28% of 50-59-year-olds say, “My applications for jobs have been rejected because of my age.”

- 25% of those in their 50s and 60s say, “I have been made to feel like I am too old for my work.”

- 8% of 50-59-year-olds say, “I have been denied health services or treatment because of my age”, but that figure leaps to 20% among those 90+.

- 28% of over-50s say, “I have been ignored or made to feel invisible.”

- 11% say, “Doctors and healthcare workers talk past me to my companion or carer.” That figure is 27% among those aged over 90.

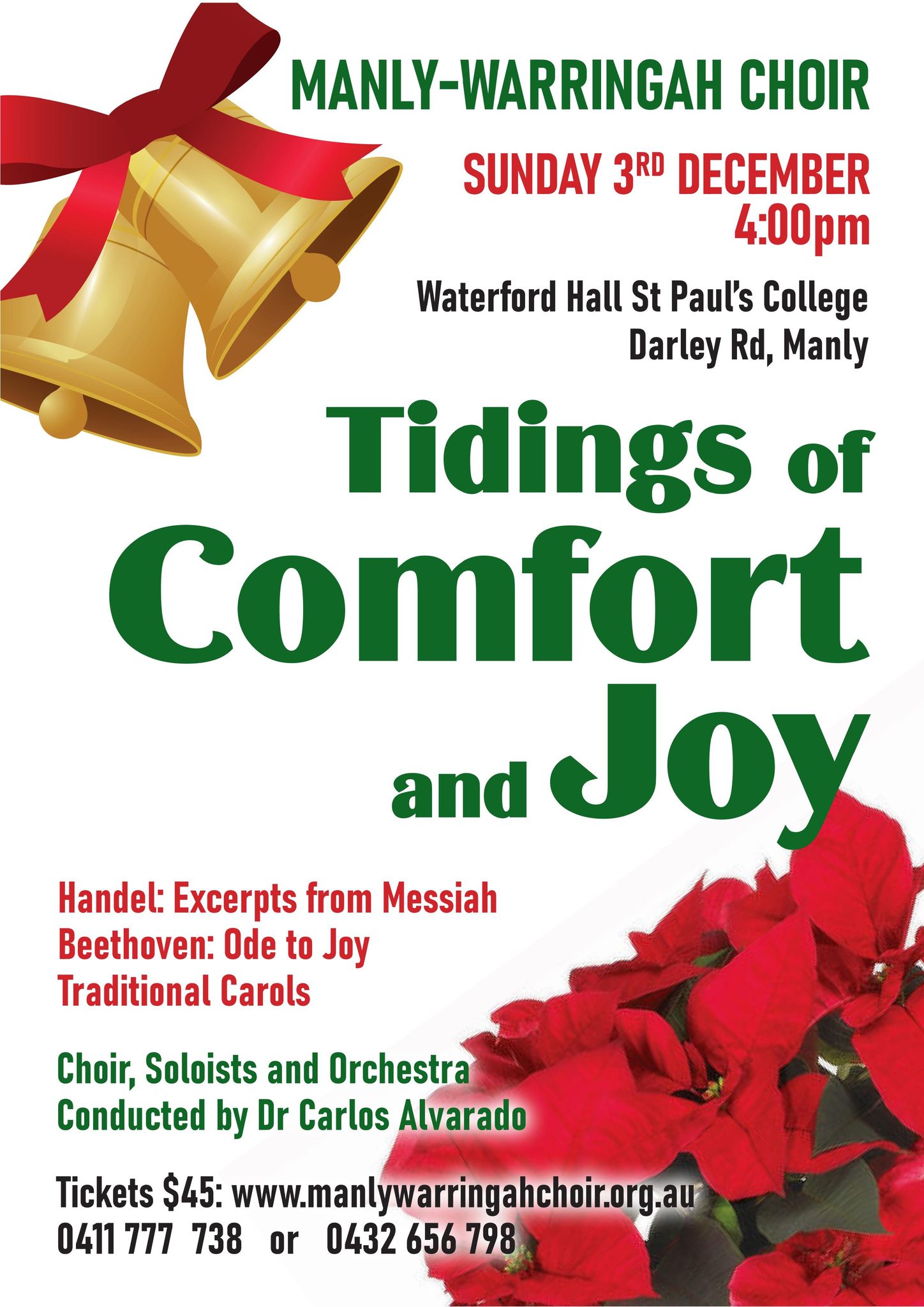

Manly-Warringah Choir: Tidings Of Comfort And Joy

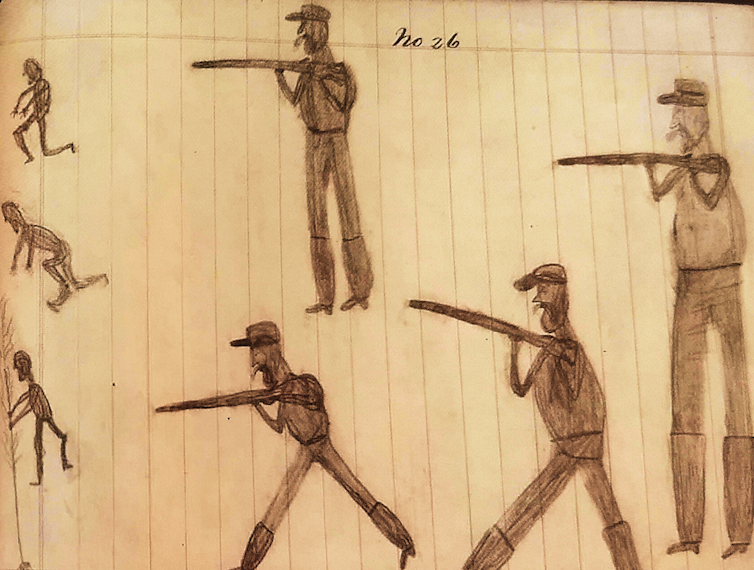

‘Equal Social Rights For SEXES’: in the 1930s, the Australian Women’s Weekly was a political forum

The Australian Women’s Weekly, the first Australian magazine dedicated solely to the interests of women, turned 90 this year. The magazine is known for its coverage centred around the home and child-rearing, but the early editions of the Weekly also created a space for Australian women to engage with politics through the lens of womanhood.

Since its first edition in June 1933, the Weekly has provided Australian women with a forum to learn, discuss and debate a range of issues. Its coverage throughout the 1930s reveals how the magazine negotiated the tension between conservative and progressive viewpoints on women’s involvement in political affairs.

The Weekly And The 1930s

The magazine’s first editor, George Warnecke, developed a prototype for a publication tailored to female readers after studying women’s interests. He wanted it to be “distinctly Australian [and] appeal across age groups”.

The Weekly was immediately popular. The initial estimated print run of 50,000 copies increased to 121,162 copies. By the end of 1939, the Weekly had a circulation of 445,000.

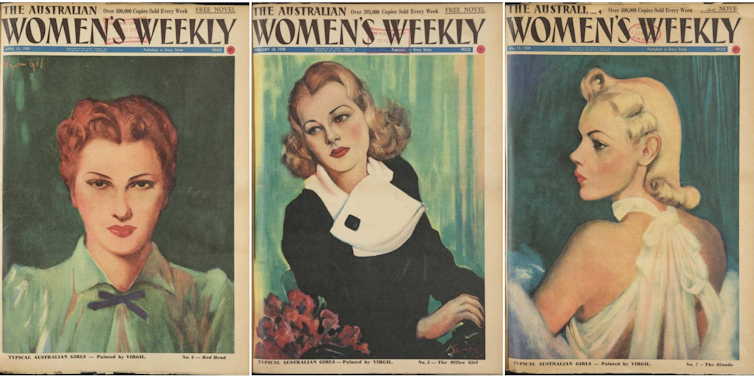

Originally launched as a “forty-four-page black and white newspaper”, it sold for two pence and followed traditional newspaper formatting, printed in broadsheet columns. It appealed to female readers with engaging images of womanhood – the first issue’s cover story was on Sydney women’s fashion.

However, the paper quickly moved away from this format towards a cover centred on a single evocative image. This change can be seen throughout August and September 1933, when the images on the front cover became increasingly prominent. Eventually, they took over the whole page.

Inside, the paper covered fashion, beauty, homemaking, entertainment – and current affairs. The first edition’s other cover story reported on a recent conference of the Women Voters’ Federation in Adelaide under the headline “Equal Social Rights for SEXES”.

In early issues, political topics were primarily addressed in the “Points of View” column on the editorial page, which acted as a forum for the editorial team to provide short critical commentaries on issues they deemed important to Australian women.

This space included readers’ responses. Another dedicated column, “So They Say”, provided space for readers to discuss previous articles, current affairs and social issues.

Politics And The Home

The Weekly’s coverage and reader contributions on current affairs created a platform for women to dissect political topics. But it balanced the tension between conservative and progressive viewpoints on women’s involvement in politics to cater to their commercial audience.

In a March 1934 editorial, Warnecke declared “this paper knows no politics” and “most women are not specially politically minded”. Women’s sphere of influence, he argued, was the household.

But Warnecke implied that women could still influence society and culture. They were outside formal institutions, but could shape the nation politically in other ways: “public opinion starts off as private opinion, and this is formed in the home”.

The editorial suggested that the Weekly’s coverage was not “non-political”, as one reader, Miss Clarke, interpreted. Rather, the paper managed to establish a forum for both conservative and progressive ideological viewpoints by claiming to separate the social from the political.

An example of this can be seen in the editorial “Women and Democracy”, published on July 14 1934, which showcased the political influence women held over their families:

The fact is that, though [women] may not take a public part in politics, the Australian woman exercises a potent influence at election times, not only because of her voting power, but because of the high esteem in which her opinion is held by the male members of her household.

Warnecke also defended women’s right to vote: “there has never been any serious question of the Australian woman being in an ‘inferior’ position because of her sex”, he argued.

Australian Women’s Political Interest

Although the Weekly often framed political debate through social and cultural lenses, there was still ample traditional political reportage in early editions. This is evident in feature articles, occasional columns and reader contributions that asserted the importance of women’s engagement with political institutions.

Mrs V. Cantwell’s October 1933 contribution positioned her against a fellow reader, identified by the initials A.S., who had declared that women were not interested in politics. Cantwell retorted:

The improved conditions of women and children to-day, as regards social services, general health, etc., are directly attributable to the fact that women are taking an increased and creditable interest in public affairs.

Cantwell’s contribution illustrated the progressive view of modern Australian women. Written in response to another reader, her piece illustrates the Weekly’s willingness to foster dialogue and debate.

Historian Hannah Viney developed the notion of “feminised politics” to describe the way “the threads of the domestic and the politics that were interwoven” in the Weekly’s coverage in the 1950s. Here we can clearly see that the Weekly allowed readers “politically minded, politically ambivalent or somewhere in between” a forum to engage with political coverage in the 1930s as well.

Towards the end of the decade, as war in Europe began to appear inevitable, Weekly readers were eager to understand the extremist ideologies that threatened world peace. This is apparent in Miss M. Muir’s reader contribution published on August 12, 1939, under the headline: “Need knowledge of foreign politics”.

Muir believed fewer than one in 50 Australian women understood what the Nazi, fascist and communist movements stood for. She proposed the Education Department supply paper lectures to Australian women “on possible political dangers”.

“We should not leave the knowledge of modern foreign politics only to the men,” she argued.

The publication of Muir’s piece in a highlighted box in the “So They Say” column implies the paper’s agreement.![]()

Zara Saunders, PhD Candidate, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

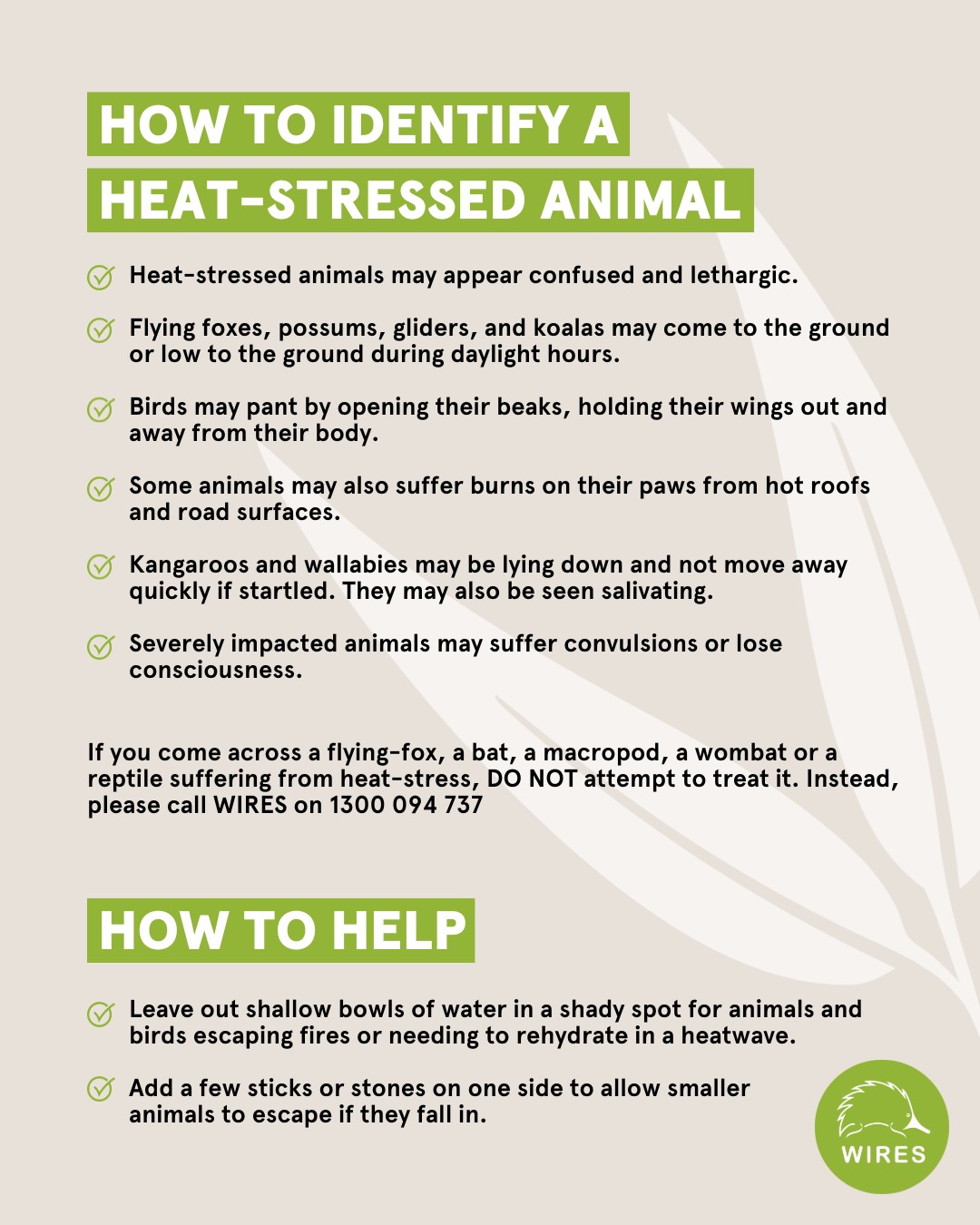

Please Look Out For Wildlife During This Spring Heat

Picnic For Nature

Bushwalk Fundraiser

- Friday 10 November

- Friday 8 December

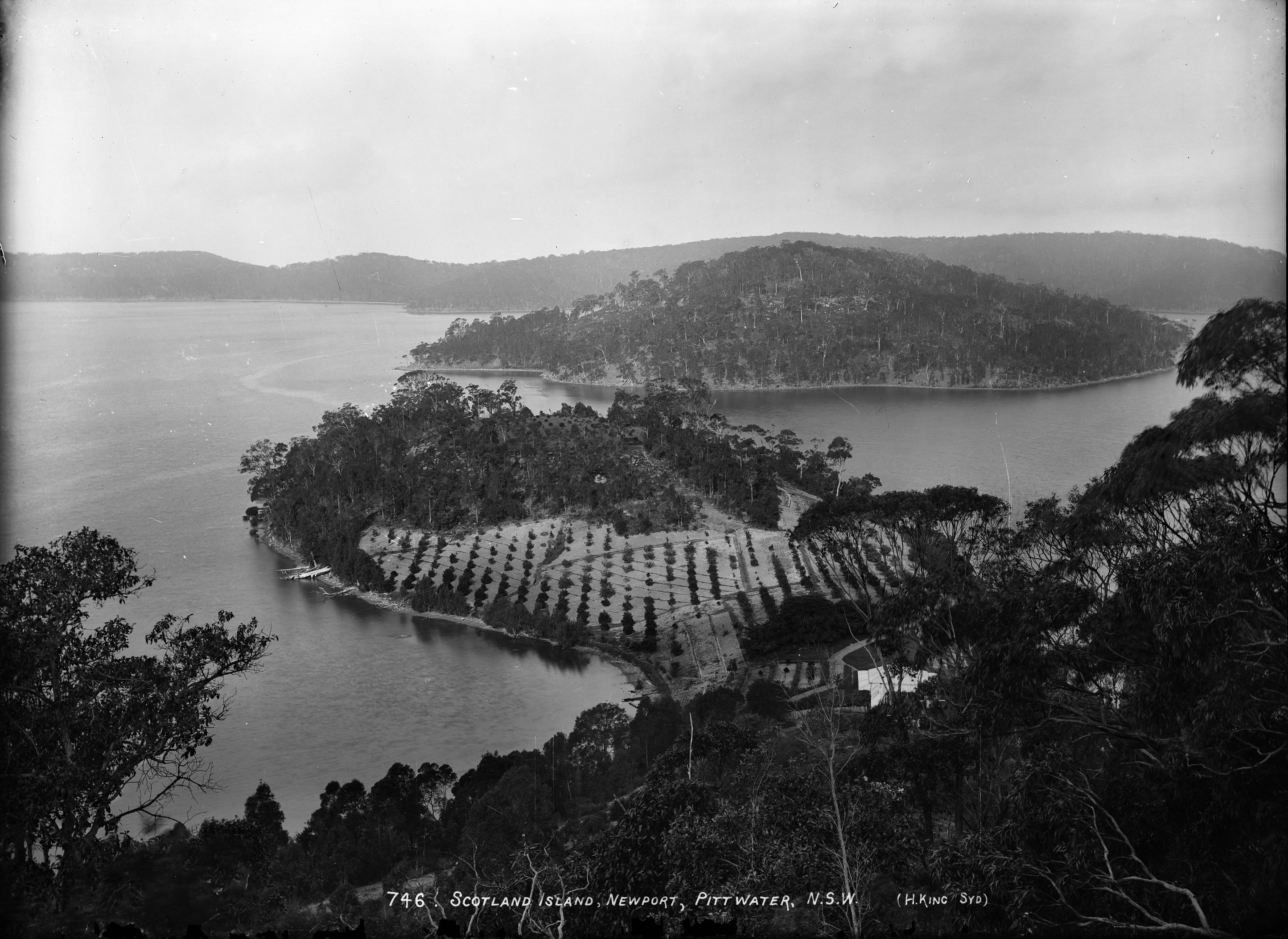

'Scotland Island, Newport, Pittwater, N.S.W.', photo by Henry King, Sydney, Australia, c. 1880-1886. and section from to show cottage on neck of peninsula at western end with no chimneys through roof. From Tyrell Collection, courtesy Powerhouse Museum

𝗞𝗶𝗺𝗯𝗿𝗶𝗸𝗶 𝗥𝗲𝘀𝗼𝘂𝗿𝗰𝗲 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗼𝘃𝗲𝗿𝘆 𝗖𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗿𝗲 𝗶𝗻𝘃𝗶𝘁𝗲𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗺𝘂𝗻𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝘁𝗼 𝗼𝘂𝗿 𝗢𝗽𝗲𝗻 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟮𝟬𝟮𝟯 𝗮𝘁 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗛𝗨𝗕 - 𝗞𝗶𝗺𝗯𝗿𝗶𝗸𝗶.

Highlighting the four resident not-for-profit organisations: Peninsula Seniors Toy Recyclers, Bikes4Life, Boomerang Bags Northern Beaches - Kimbriki, Reverse Garbage and their dedicated volunteers.

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group Begins

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Next Rescue And Care Course Commences October 28

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

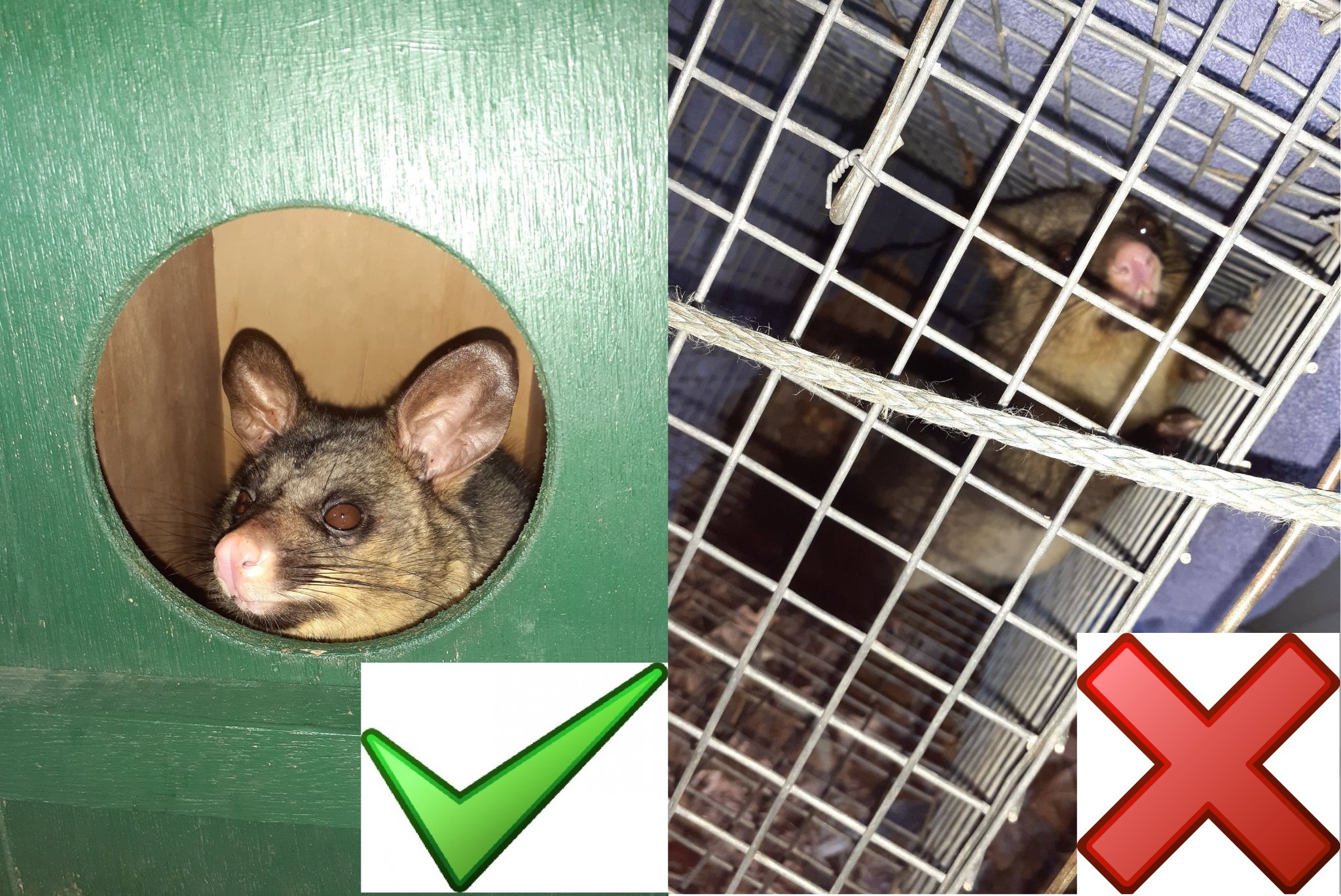

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

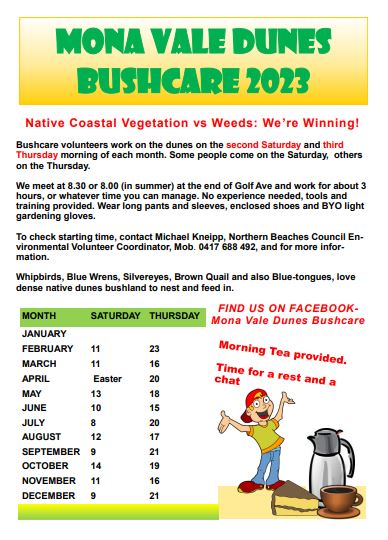

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

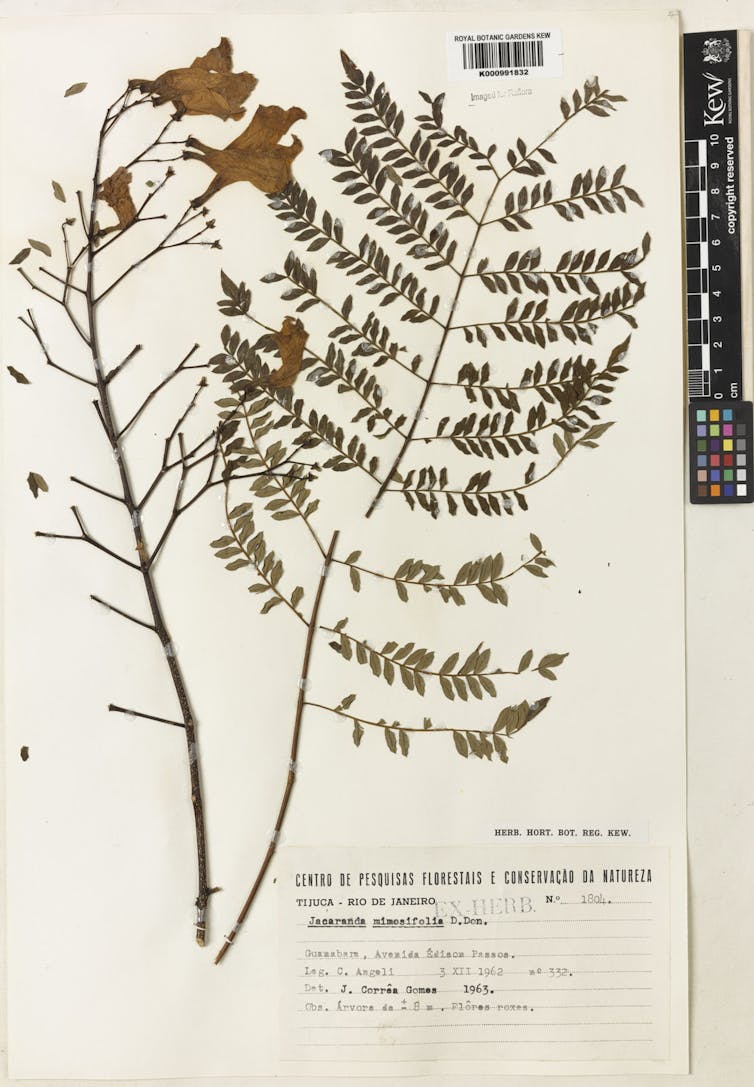

Streets of purple haze: how the South American jacaranda became a symbol of Australian spring

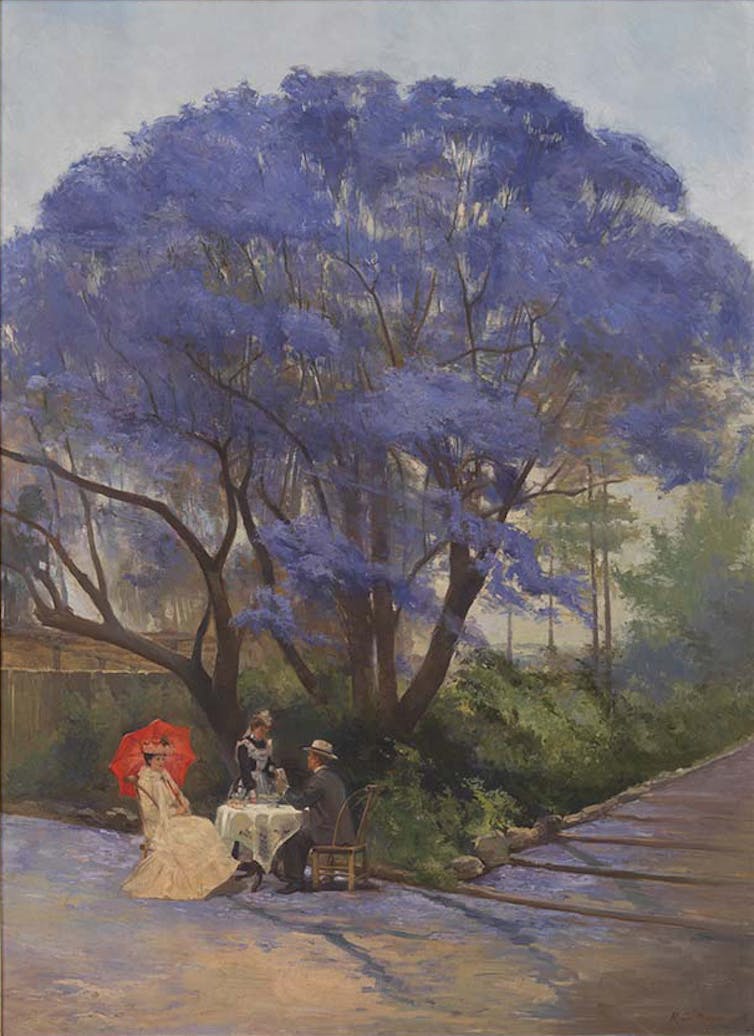

Jacaranda season is beginning across Australia as an explosion of vivid blue spreads in a wave from north to south. We think of jacarandas as a signature tree of various Australian cities. Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth all feature avenues of them.

Grafton in New South Wales hosts an annual jacaranda festival. Herberton in Queensland is noted for its seasonal show.

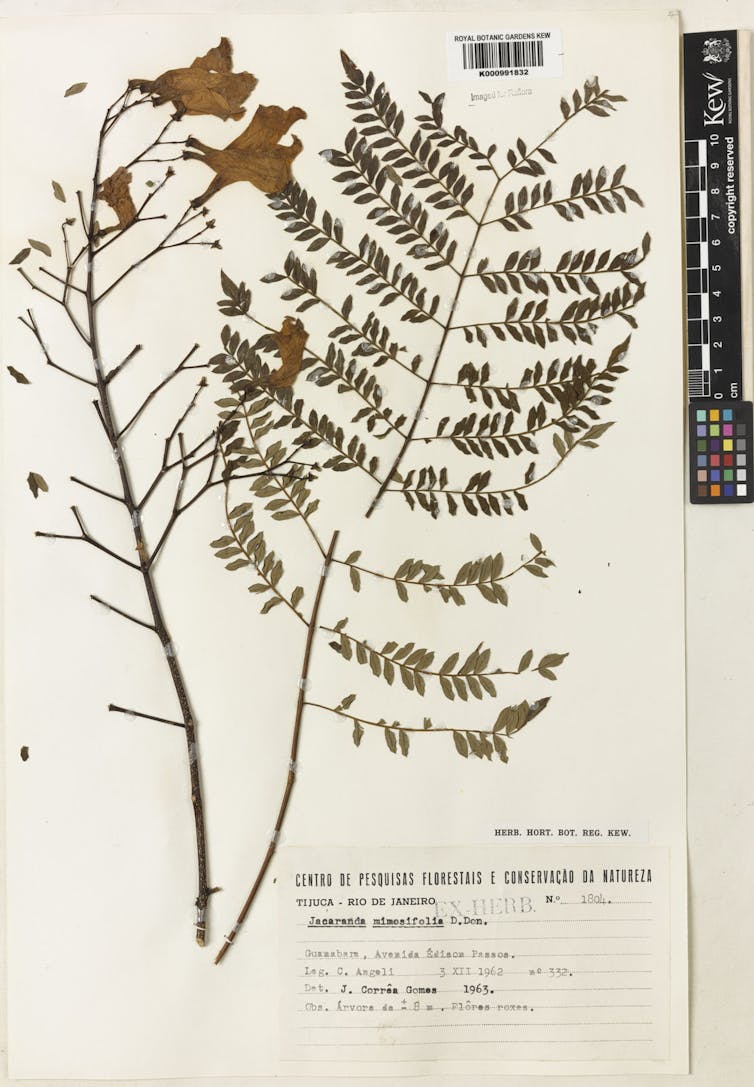

There are significant plantings in many botanic, public and university gardens across Australia. Jacaranda mimosifolia (the most common species in Australia) doesn’t generally flower in Darwin, and Hobart is a little cold for it.

So showy and ubiquitous, jacarandas can be mistaken for natives, but they originate in South America. The imperial plant-exchange networks of the 19th century introduced them to Australia.

But how did these purple trees find their stronghold in our suburbs?

Propagating The Trees

Botanist Alan Cunningham sent the first jacaranda specimens from Rio to Britain’s Kew gardens around 1818.

Possibly, jacaranda trees arrived from Kew in colonial Australia. Alternately, Cunningham may have disseminated the tree in his later postings in Australia or through plant and seed exchanges.

Jacarandas are a widespread imperial introduction and are now a feature of many temperate former colonies. The jacaranda was exported by the British from Kew, by other colonial powers (Portugal for example) and directly from South America to various colonies.

Jacarandas grow from seed quite readily, but the often preferred mode of plant propagation in the 19th century was through cuttings because of sometimes unreliable seed and volume of results.

Cuttings are less feasible for the jacaranda, so the tree was admired but rare in Australia until either nurseryman Michael Guilfoyle or gardener George Mortimer succeeded in propagating the tree in 1868.

Once the trees could be easily propagated, jacarandas became more widely available and they began their spread through Australian suburbs.

A Colonial Import

Brisbane claims the earliest jacaranda tree in Australia, planted in 1864, but the Sydney Botanic Garden jacaranda is dated at “around” 1850, and jacarandas were listed for sale in Sydney in 1861.

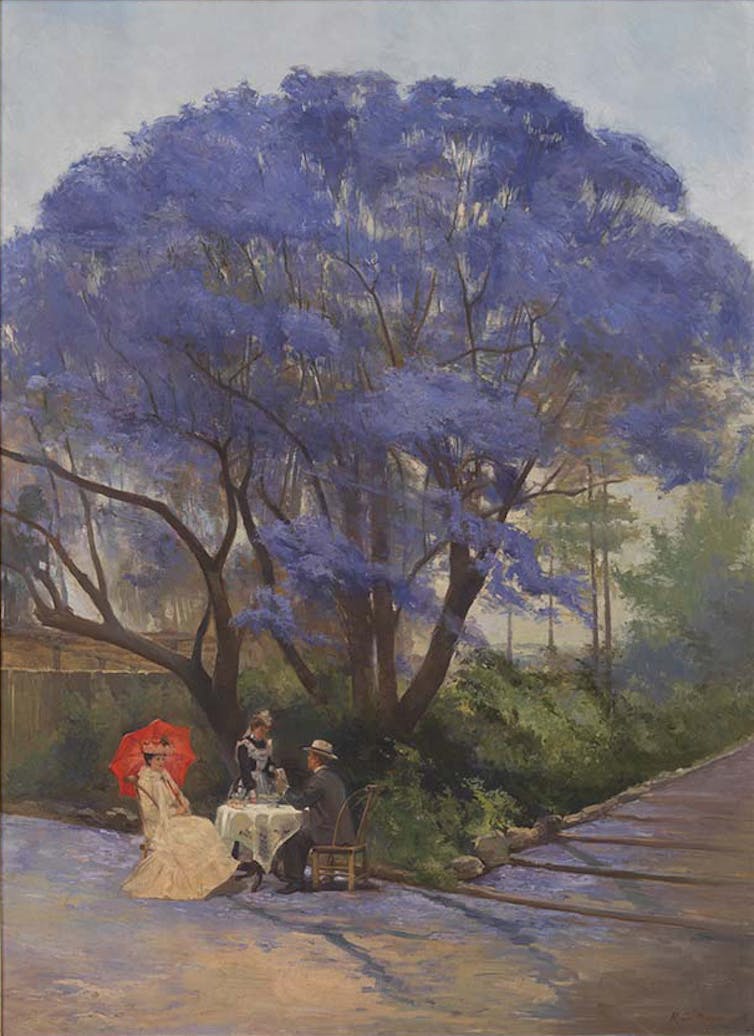

These early park and garden plantings were eye-catching – but the real impact and popularity of jacarandas is a result of later street plantings.

Jacaranda avenues, in Australia and around the world, usually indicate wealthier suburbs like Dunkeld in Johannesberg and Kilimani in Nairobi.

In Australia, these extravagant displays appear in older, genteel suburbs like Subiaco and Applecross in Perth; Kirribilli, Paddington and Lavender Bay in Sydney; Parkville and the Edinburgh Gardens in North Fitzroy in Melbourne; Mitcham, Frewville and Westbourne Park in Adelaide; and St Lucia in Brisbane.

The trend toward urban street avenue plantings expanded internationally in the mid 19th century. It was particularly popular in growing colonial towns and cities. It followed trends in imperial centres, but new colonial cities offered scope for concerted planning of avenues in new streets.

Early Australian streets were often host to a mix of native plants and exotic imported trees. Joseph Maiden, director of the Sydney Botanic Gardens from 1896, drove the move from mixed street plantings towards avenues of single-species trees in the early 20th century.

Maiden selected trees suitable to their proposed area, but he was also driven by contemporary aesthetic ideas of uniformity and display.

By the end of the 19th century, deciduous trees were becoming more popular as tree plantings for their variety and, in southern areas, for the openness to winter sunshine.

It takes around ten years for jacaranda trees to become established. Newly planted jacarandas take between two and 14 years to produce their first flowers, so there was foresight in planning to achieve the streets we have today.

In Melbourne, jacarandas were popular in post-first world war plantings. They were displaced by a move to native trees after the second world war. Despite localised popularity in certain suburbs, the jacaranda does not make the list of top 50 tree plantings for Melbourne.

In Queensland, 19th-century street tree planting was particularly ad hoc – the Eagle Street fig trees are an example – and offset by enthusiastic forest clearance. It wasn’t until the early 20th century street beautification became more organised and jacaranda avenues were planted in areas like New Farm in Brisbane.

The popular plantings on the St Lucia campus of the University of Queensland occurred later, in the 1930s.

A Flower For Luck

In Australia, as elsewhere, there can be too much of a good thing. Jacarandas are an invasive species in parts of Australia (they seed readily in the warm dry climates to which they have been introduced).

Parts of South Africa have limited or banned the planting of jacarandas because of their water demands and invasive tendencies. Ironically, eucalypts have a similar status in South Africa.

Writer Carey Baraka argues that, however beloved and iconic now, significant plantings of jacarandas in Kenya indicate areas of past and present white population and colonial domination.

Despite these drawbacks, spectacular jacaranda plantings remain popular where they have been introduced. There are even myths about them that cross international boundaries.

In the southern hemisphere – in Pretoria or Sydney – they bloom on university campuses during examination time: the first blooms mark the time to study; the fall of blooms suggests it is too late; and the fall of a blossom on a student bestows good luck.![]()

Susan K Martin, Emeritus Professor in English, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change is disrupting ocean currents. We’re using satellites and ships to understand how

Earth’s ocean is incredibly vast. Some parts of it are so remote that the nearest human habitation is the International Space Station.

As the world warms, what happens in the ocean – and what happens to the ocean – will be vital to all our lives. But to monitor what’s happening in remote waters, we need to study the ocean from space.

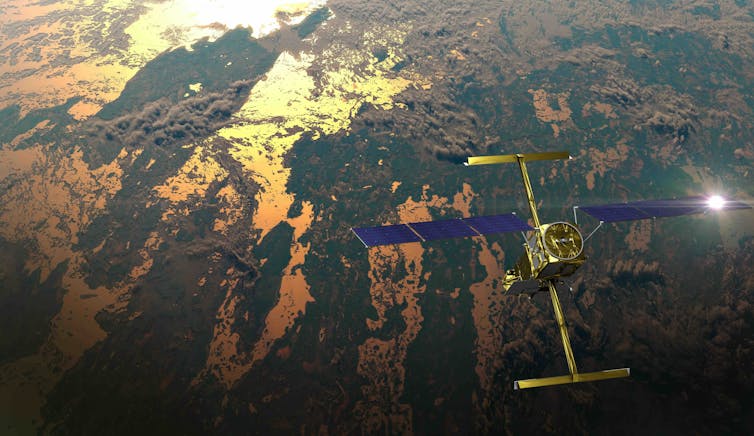

Late last year, NASA and CNES, the French space agency, launched a satellite that promises to give scientists a far better view than ever before of the ocean’s surface. The Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) mission will reveal ocean currents that play a crucial role in the weather and climate.

To make the most of the satellite observations, we need to compare them with measurements made at surface level. That is why we are heading out to sea on the state-of-the-art CSIRO research vessel RV Investigator to gather essential ocean data under the satellite’s path as it orbits Earth.

Current Affairs

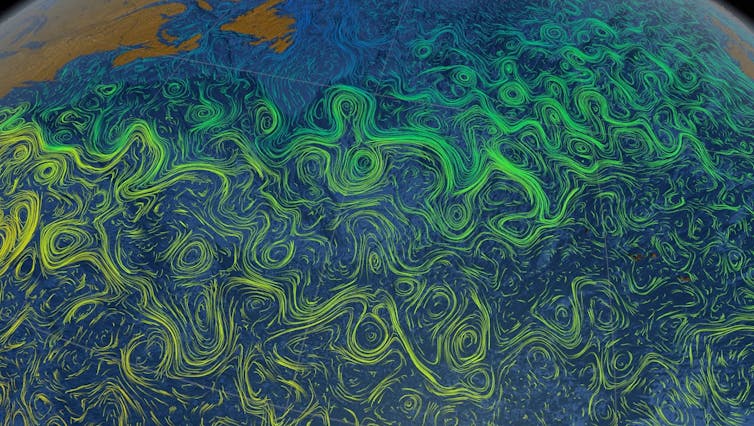

Climate change is disrupting the global network of currents that connect the oceans. Researchers have detected a slowdown of the deep “overturning circulation” that carries carbon, heat, oxygen and nutrients from Antarctica around the globe. Meanwhile, at the surface, ocean currents are becoming more energetic.

We have also seen dramatic changes in fast, narrow rivers of seawater called western boundary currents, such as the Gulf Stream and the East Australian Current.

These currents funnel heat from the tropics towards the poles, and in recent decades they have become hotspots for ocean warming. In the Southern Hemisphere, they are warming two to three times faster than the global average.

As these currents destabilise, they alter how heat is distributed throughout the ocean. This in turn will cause major changes in local weather and marine ecosystems that may impact the lives of millions of people.

Playground Physics

The SWOT satellite mission will give researchers a powerful new tool to monitor changes in ocean currents by using accurate satellite measurements of the sea surface – plus a little bit of playground physics.

The satellite carries an instrument that will map variations in the height of the sea surface in unprecedented detail. These variations might be less than a metre in height over horizontal distances of hundreds of kilometres. But oceanographers can use the measurements to estimate ocean currents flowing underneath.

Small variations in the height of the sea surface create horizontal pressure differences that try to push water away from areas of high sea level and towards areas of low sea level. That pressure difference is balanced by the Coriolis force, which gently deflects ocean currents to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere.

You can experience the Coriolis force at the playground. Step onto a merry-go-round and ask a friend to stand on the opposite side from you. As you start spinning, toss a ball to your friend. You will notice that the ball appears to be deflected away from the direction of rotation.

In reality, the ball has moved in a straight line; your friend has simply moved away from where you were aiming. But, to you both, the ball seems to have been deflected by an invisible “pseudo-force” – the Coriolis force.

Now imagine the merry-go-round is Earth, and the ball is an ocean current. The Coriolis deflection is enough to balance pressure differences across hundreds of kilometres and causes seawater to flow in ocean currents.

Science At Sea

By carefully measuring the height of the sea surface and using our knowledge of the Coriolis force, oceanographers will be able to use data from NASA’s satellite to reveal ocean currents in greater detail than ever before. But to make sense of that data, researchers need to compare satellite measurements with observations made down here on Earth.

That’s why we are leading a voyage of more than 60 scientists, support staff and crew aboard the RV Investigator, Australia’s national flagship for blue water ocean research.

Our 24-day voyage will study ocean dynamics off Australia’s southeast coast using the Investigator’s world-class scientific equipment, including satellite-tracked floating buoys and drifters that will be used to measure the real-time movement of currents at the ocean surface.

The voyage is part of a huge collaboration by scientists around the world to gather observational data under the satellite’s path as it orbits Earth. This data will help validate satellite measurements and improve weather forecasts, including those from Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology, and assist with climate risk assessment and prediction.

We hope to better understand how our oceans are changing using what we observe in space, at sea — and in the playground.

This research is supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.

You can follow our voyage on Twitter/X using the hashtag #RVInvestigator.![]()

Shane Keating, Senior Lecturer in Mathematics and Oceanography, UNSW Sydney and Moninya Roughan, Professor in Oceanography, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why the ‘drug dealers defence’ doesn’t work for exporting coal. It’s actually Economics 101

John Quiggin, The University of QueenslandIn defending a Federal Court case brought by opponents of her decisions to approve two export coal mines, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek is relying in part on what critics call the “drug dealer’s defence”.

It’s reasoning that argues: if we don’t sell this product, someone else will.

Prime Minister Albanese has argued the same thing, telling The Australian

policies that would just result in a replacement of Australian resources with resources that are less clean from other countries would lead to an increase in global emissions, not a decrease.

Albanese’s reasoning is that saying no to new Australian coal mines wouldn’t cut global emissions, it would just produce “less economic activity in Australia”.

If it sounds like a familiar argument, it is – past prime ministers and the coal industry have made similar claims for decades.

It’s possible to test this argument using economics, putting to one side the question of whether it is morally justifiable.

The Defence Works For Drug Dealers

Let’s look at how this defence works with retail drug dealers, many of whom are drug users themselves.

Street-level drug dealing is a job that doesn’t require much skill and pays above the minimum wage, even after allowing for the risk of arrest.

As a result, as soon as one dealer is arrested, someone will enter the market to replace the dealer. For this reason, drug policy has shifted away from traditional modes of street-level enforcement and towards community partnerships.

But coal is different. Global markets are supplied by a range of producers, each with different costs. Some mines can cover their costs even when world prices are low, others require very high world coal prices to break even.

In the case of metallurgical (coking) coal used to make steel, Australia’s mines are mostly at the low-cost end of the spectrum as shown below:

Indicative hard coking coal supply curve by mine, 2019

Thermal coal, used in electricity generation, is more complex, since much of the variation in price relates to its quality, rather than extraction cost.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that if one producer withdraws from the market or reduces output, it is highly unlikely to be replaced by an identical-cost producer.

It is likely instead to be replaced by a higher-cost supplier who needs a higher price to cover its costs. That’ll make the coal less attractive to the buyer who would have bought from the low-cost producer, making that buyer likely to buy less of it.

This is Economics 101, illustrated in the supply and demand diagrams in just about every economics textbook.

Why Australia’s Coal Matters Globally

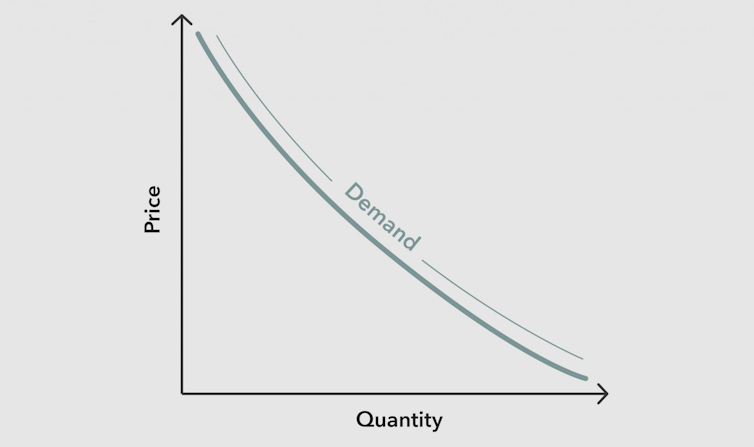

In most markets, the demand curve is downward sloping, meaning the higher the price, the less the buyer wants.

And in most markets, the supply curve is upward sloping, meaning the higher the price, the more the seller is prepared to sell.

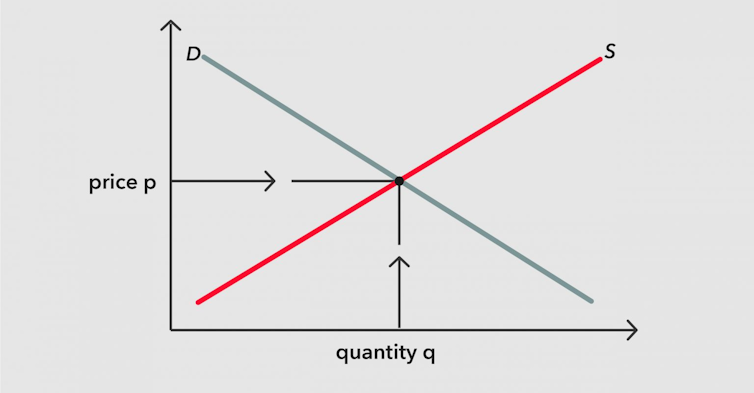

What’s bought, and for how much, depends on where those curves meet.

If the supply curve moves up, because the cost of supply has increased, the price at which the good is bought will move up and the quantity bought will move down.

In the figure below, the supply curve S1 is the current global supply.

If Australia supplies less coal, the supply curve will shift from S1 to S2, resulting in the higher price P2.

The higher price will result in increased supply from competitors, but also a reduction in the total amount consumed, a cut from Q1 to Q2.

This means that, contrary to government claims, our decisions will have an impact on global emissions and ultimately on global heating

Moreover, Australian decisions aren’t isolated.

All around the world, governments, financial institutions and civil society groups are grappling with the need to transition away from coal.

Proposals for new and expanded coal mines and coal-fired power stations face resistance at every step. In particular, the great majority of global banks and insurance companies now refuse to finance and insure new coal.

This means that the long-run response to a reduction in Australia’s supply of coal will involve less substitution and more of a drop in use than might be thought.

For Coal, The Drug Dealer’s Defence Is Shoddy

It makes the drug dealers defence for exporting coal especially shoddy.

It would be open to Plibersek to make another argument: that in the government’s political judgement, Australians are not willing to wear the short-run costs of a transition from coal, regardless of the impact on the global climate manifested every day in bushfires, floods and environmental destruction.

But instead, we are being told that if Australia cuts supply, other suppliers will rush in, without being told about their costs and what will happen next.

In markets like coal, with a fixed number of suppliers facing different costs, demand responds to the withdrawal of supply in the way the economics textbooks say it should.![]()

John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s emissions must decline more steeply to reach climate commitment: OECD

Michelle Grattan, University of CanberraAustralia’s emissions need to decline “on a much steeper trajectory” if it is to meet its declared commitment of a 43% reduction by 2030 and net zero by 2050, the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development says.

In its report on Australia, released as part of its Going For Growth update on Tuesday, the OECD recommends Australia develop

a national, integrated long-term emissions reduction strategy with clear goals and corresponding policy settings to achieve climate targets.

The OECD also suggests broadening the scope of Australia’s so-called Safeguard Mechanism, which at present regulates the emissions of Australia’s 215 biggest polluting facilities.

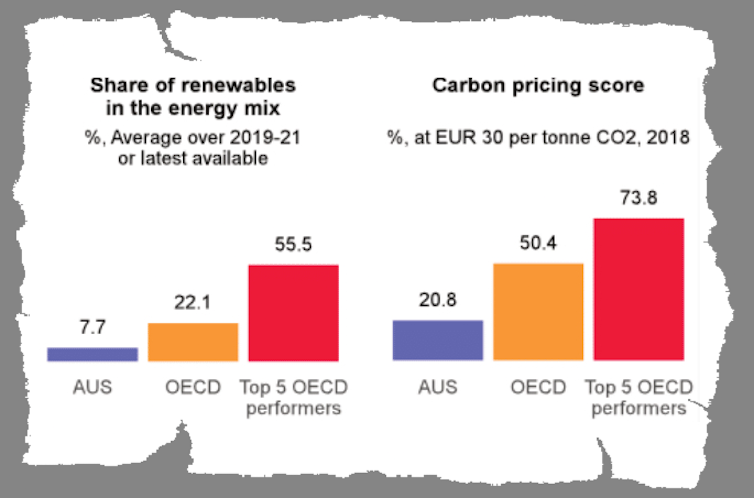

It awards Australia a score on carbon pricing well below the OECD average and even further below that of the top OECD performers.

It says the share of renewables in Australia’s energy supply averaged only 7.7% between 2019 and 2021, compared to an average of 22.1% for OECD members, and 55.5% for the top performers.

The OECD is a forum of 38 mainly high-income countries, including Australia, that describe themselves as committed to democracy and market economies.

The report is critical of Australia’s performance on a number of other fronts, including income support for the unemployed, job market flexibility and the recognition of trade qualifications.

It says Australia’s JobSeeker unemployment benefit remains among the lowest in the OECD and below the relative poverty line when compared to the wages available from work.

The Albanese government has increased the rate of JobSeeker in the May budget. The report recommends the government consider “further increasing” it.

Declining Productivity, Declining Competitiveness

The OECD finds signs of “reduced competitive intensity” in product markets, as well as falling labour mobility. “Productivity growth has also slowed down.” It says about one in five workers needs a licence to do their work, raising economic costs, and calls for automatic mutual recognition of licenses across states.

Access to fast broadband is low compared to other developed countries, and the take-up of digital technologies by businesses can be improved, the report says.

The OECD also draws attention the “large” gaps in economic and wellbeing measures between Indigenous and other Australians. It recommends the government “embed the Productivity Commission Indigenous Evaluation Strategy in the policy design and evaluation process of all Australian government agencies”.

Workforce Transformation Needed For 2050 Target

Meanwhile, a report prepared by Jobs and Skills Australia entitled The Clean Energy Generation: workforce needs for a net zero economy says the government’s 2050 net-zero emissions target will require a transformation in the workforce that is “substantial but not unprecedented”.

“Like the post-war industrial transformation and the digital transformation of the late twentieth century, a new generation of workers will be required, both from existing energy sectors and through new pathways into clean energy. New jobs, skills, qualifications, training pathways, technologies and industries will emerge over the next 30 years,” the report says.

“Australia will need to consider the full range of levers across the education, training, migration, procurement, and workplace relations systems to ensure a sustainable and equitable path towards net zero.”

Treasurer’s Response To OECD

Treasurer Jim Chalmers said the Albanese government was acting on the areas identified in the OECD report.

Its policies were “focused on maximising the opportunities of the energy transformation, embracing digitalisation and new technology and investing in our people and their skills so that we can build a more productive, prosperous and dynamic economy”.

“We’re securing faster progress towards decarbonisation through our safeguard mechanism, over $40 billion of investment in the energy transformation, our sustainable finance strategy, and establishing a new Net Zero authority to train workers and prepare communities for new opportunities here,” Chalmers said.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why Australia urgently needs a climate plan and a Net Zero National Cabinet Committee to implement it

Tony Wood, Grattan InstituteAustralia has a legislated target to reduce greenhouse emissions, a federal government with commitments to increase the share of renewable electricity and reduce power prices, and a globally important economic opportunity at its feet.

In the second half of the government’s current term, delivery looks hard across the board. All is not lost, but we must transform our economy to a timetable. The unprecedented scale and pace of the economic transformation, and the consequences of failure, demand an unprecedented response.

To get things on track requires the government to develop a plan with the right mix of political commitment, credible policies, coordination with industry, and support from communities. And, critically, the plan must be implemented. Too often targets have been set without being linked to policies to achieve them, or linked so poorly that the extra cost and delay sets back the climate transition.

By the middle of this year, Australia’s emissions were 25 per cent below the 2005 level. But the trend of steady reductions has stalled, and sectors such as transport and agriculture have moved in the wrong direction.

Such ups and downs will continue in response to external events, as we have seen with COVID, droughts, and war on the other side of the world. Policies must be flexible if they are to remain broadly on course in the face of such events.

Trouble In The Power Department

The detail matters: national emissions reductions have slowed, as has the growth in renewable generation towards the government’s 2030 target of 82 per cent.

At the same time, the government’s target of lower power bills by 2025 looks out of reach, and electricity reliability is threatened as coal-fired generation closes without adequate replacement.

The production and use of natural gas contributes around 20 per cent of Australia’s emissions. The use of gas in industry will be covered by the Safeguard Mechanism, a policy designed by the Coalition and now revised by Labor, to drive down emissions from the country’s 200 biggest emitters.

Emissions from gas-fired power generation will fall with the growth of renewables. But there are no constraints on fossil gas use in other sectors, such as our homes.

Industrial emissions are slowly growing. The huge amount of hype about green hydrogen has so far proven to be little more than that: Australia continues to have lots of potential green hydrogen projects, but virtually none are delivered.

Finally, we remain without constraints on vehicle emissions, and with a large herd of grazing cattle and sheep whose emissions are determined more by the weather than the actions of our best-meaning farmers.

The Risk Of Swinging From Naive To Negative

So, we are in a hard place. Naïve optimism about an easy, cheap transition to net zero is at risk of giving way to brutal negativity that it’s all just too hard. The warnings of early spring fires and floods in Australia and extreme heat during the most recent northern hemisphere summer will feed this tension.

The federal government’s latest Intergenerational Report provides a deeply disturbing snapshot of the potential economic impacts if we fail to get climate change under control. Yet in a world 3 to 4 degrees hotter than pre-industrial levels, economic impacts could be the least of our worries.

The task is unparalleled outside wartime. Within 30 years we must manage the decline of fossil fuel extractive sectors, transform every aspect of our energy and transport sectors, reindustrialise much of manufacturing, and find solutions to difficult problems in agriculture.

What’s to be done?

The Need For A Net Zero National Cabinet Committee

We should begin with leadership across the federal government, coordinated with the states and territories. The best structure might be a Net Zero National Cabinet Committee with two clear objectives – to develop and begin implementing a national net zero transformation plan by the end of 2024.

Modern governments are more than happy to set targets and announce plans to meet them. They seem to have lost the capacity or will to implement such plans. The Net Zero Economy Agency, created in July and chaired by former Climate Change Minister Greg Combet, could be charged with that task.

The first step is being taken – the Climate Change Authority is now advising on emissions reduction targets for 2035 and perhaps beyond. The government’s work to create pathways to reducing emissions in every economic sector must be used to build a comprehensive set of policies that are directly linked to meeting the targets.

How To Get Electricity Moving In The Right Direction

The electricity sector can be put on track with three actions. One, drive emissions reduction towards net zero using a sector-focused policy such as the Renewable Energy Target or the Safeguard Mechanism.

Two, implement the Capacity Investment Scheme, a policy intended to deliver dispatchable electricity capacity to balance a system built on intermittent wind and solar supply.

Three, set up a National Transmission Agency to work with the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) to plan the national transmission grid and with authority to direct, fund, and possibly own that grid.

For heavy industry, the scale and pace of change demands a 21st-century industry policy, in three parts. Activities such as coal mining will be essentially incompatible with a net-zero economy. Activities such as steel-making may be able to transform through economic, low-emissions technologies.

Finally, activities such as low-emissions extraction and processing of critical energy minerals, which are insignificant today but which in time could help Australia to capitalise on globally significant comparative advantages.

Create A Plan – And Stick To It

The government has made a good start by revising the Safeguard Mechanism and the Hydrogen Strategy and developing a Critical Minerals Strategy. These should be brought together in an overarching policy framework with consistent, targeted policies linked to clear goals, developed and executed in sustained collaboration with industry.

The Safeguard Mechanism will need to be extended beyond 2030 and its emissions threshold for the companies it covers lowered to 25,000 tonnes of emissions per year.

Industry funding will probably need to expand, and give priority to export-oriented industries that will grow in a net-zero global economy. And the federal and state governments should phase out all programs that encourage expansion of fossil fuel extraction or consumption.

In transport, long-delayed emissions standards should be set and implemented. Finally, government-funded research, some of it already underway, should focus on difficult areas such as early-stage emissions reduction technologies in specific heavy industries, transport subsectors, and emissions from grazing cattle and sheep.

There is little new or radical in the elements of this plan. What would be new is a commitment to its design and implementation. This is what government needs to do now. The consequences of failure are beyond our worst fears, the benefits of success beyond our best dreams.![]()

Tony Wood, Program Director, Energy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

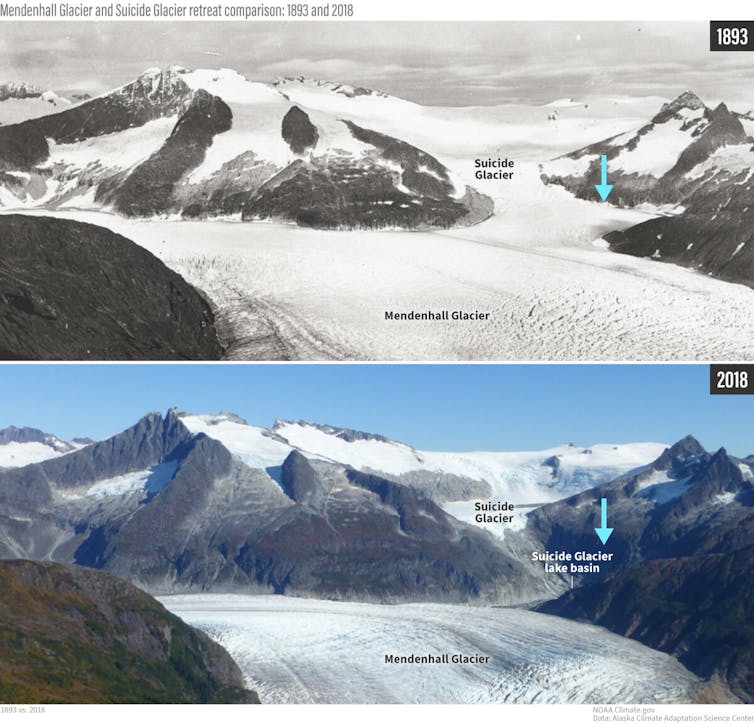

Even temporary global warming above 2℃ will affect life in the oceans for centuries

There is growing consensus that our planet is likely to pass the 1.5℃ warming threshold. Research even suggests global warming will temporarily exceed the 2℃ threshold, if atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO₂) peaks at levels beyond what was anticipated.

Exceeding our emissions targets is known as a climate overshoot. It may lead to changes that won’t be reversible in our lifetime.

These changes include sea-level rise, less functional ecosystems, higher risks of species extinction, and glacier and permafrost loss. We are already seeing many of these changes.

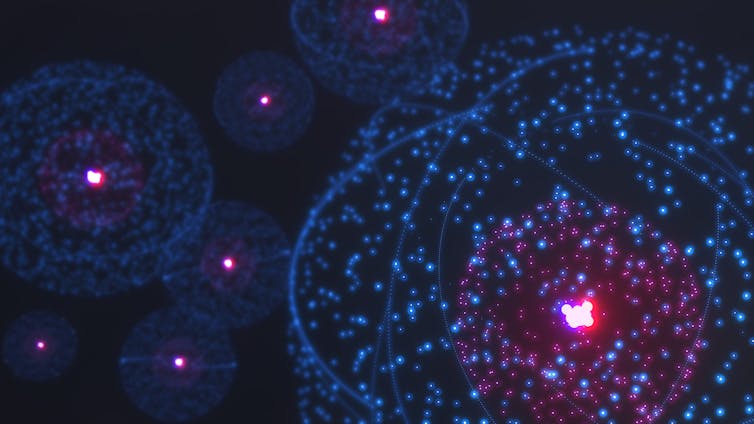

Our newly published research investigates the implications of a climate overshoot for the oceans. Across all climate overshoot experiments and all models, our analysis found associated changes in water temperatures and oxygen levels will decrease viable ocean habitats.

The decrease was observed for centuries. This means humanity will continue to feel its impacts long after atmospheric CO₂ levels have peaked and declined.

What Did The Study Look At?

Our analysis is based on simulations with Earth system models as part of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6). The project underpins the latest assessment reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

We looked at multi-model results from two different CMIP6-developed experiments that simulate a climate overshoot.

One corresponds to a climate scenario simulating an overshoot this century.

The other experiment is from the Carbon Dioxide Model Intercomparison Project (CDRMIP). It was designed to explore the reversibility of a climate overshoot and how this impacts the Earth system.

We studied the combined effects of changes in ocean temperature and oxygen levels. These changes are linked because the warmer the water, the less dissolved oxygen it can hold.

In this study we explored what warmer oceans and deoxygenation mean for the long-term viability of marine ecosystems. These changes have already begun under climate change.

To quantify these impacts we used a metabolic index, which describes the (aerobic) energy balance of individual organisms. In viable ecosystems the supply of oxygen needs to exceed their demand. The closer supply is to demand, the more precarious ecosystems become, until demand exceeds supply and these ecosystems are no longer viable.

Under global warming in the ocean we are already seeing an increase in metabolic demand and reduction in supply due to deoxygenation.

The index gives us the ability to assess how changing ocean temperatures impact the long-term viability of different marine species and their habitats. This allows us to explore how ecosystems across the world’s oceans respond to a climate overshoot, and for how long these changes will persist.

As conditions changed under the scenarios, we followed the evolution of the global ocean volume that can or cannot support the metabolic demands of 72 marine species.

What Did The Study Find?

Across all climate overshoot experiments and all models, our findings show the water volumes that can provide viable habitats will decrease. This decrease persisted on the scale of centuries – well after global average temperature recovers from the overshoot.

Our study findings raise concerns about shrinking habitats. For example, species like tuna live in well-oxygenated surface waters and are restricted by low oxygen in deeper waters. Their habitat will be compressed towards the surface for hundreds of years, according to our study.

Fisheries that rely on such species will need to understand how changes in their distribution will affect fishing grounds and productivity. What is clear is that ecosystems would need to adapt to these changes or risk collapsing with significant environmental, societal and economic implications.

What Are The Implications Of Shrinking Marine Habitats?

To date, most research has focused on ocean warming. The combination of temperature and deoxygenation we studied shows warming may harm marine ecosystems for hundreds of years after global mean temperatures have peaked. We will have to think more about resource management to avoid compromising species abundance and food security.

Climate overshoots not only matter in terms of their peak value but also in terms of how long temperature remains above the target. It is better to return from an overshoot than staying at the higher level, but a lot worse than not overshooting in the first place.

If we significantly overshoot the temperature targets of the Paris Agreement, many climate change impacts will be irreversible. Therefore, every effort should be made to drastically reduce emissions now. We can then avoid a significant climate overshoot, reach net-zero emissions by mid-century and keep warming “well below” 2℃.

Our assessment of potential future changes relies heavily on Earth system models. To better answer key questions about climate overshoots and the reversibility of the climate system, we need to further improve our models.

This includes sustained observations to validate our models. We must also develop new experimental frameworks to explore what can be done in the event of a climate overshoot to minimise its long-term impact.![]()

Tilo Ziehn, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO; Andrew Lenton, Director Permanent Carbon Locking Future Science Platform (CarbonLock), CSIRO Environment, CSIRO, and Yeray Santana-Falcón, Postdoctoral research fellow, CNRM, Météo-France (Toulouse, France)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Early heat and insect strike are stressing urban trees – even as canopy cover drops

Have you noticed street trees looking oddly sad? You’re not alone. Normally, spring means fresh green leaves and flowers. But this year, the heat has come early, stressing some trees.

But there’s more going on – insects are on the march. Many eucalypts are showing signs of lerp or psyllid attack. These insects hide underneath leaves and build little waxy houses for themselves. But as they feed on the sap, they can give the leaves a stressed, pinkish look. When they appear in numbers – as they are this year – they can defoliate a whole tree with a serious infestation.

How did we get here? Milder, wetter summers during three successive La Niña years mean boomtime for insects. This year, we’ve had a warm winter and a warm spring, meaning insects are up and about early and in large numbers.

This summer will be an El Niño, which usually means drier and hotter weather for most of Australia. For those of us interested in urban trees, these conditions are troubling.

But it’s more than that. The fact our urban trees are in danger should tell us something – we need to value and protect them better. As the world heats up, our urban forests will be even more at risk.

What’s Different This Year?

In most years, insect infestations arrive later. That gives trees time to produce a flush of new growth. As a result, they’re rarely lethal. Trees can put out more leaves and recover.

But this year, they’re attacking early and in numbers. It also makes it more likely we’ll see more and more infestations over a long summer. End result: stressed trees, and even deaths from sap-sucking and other insect damage.

That’s not ideal for us either. In an El Niño summer, we’ll likely face hotter days. This year is unusually hot, due to unchecked climate change. The heatwaves to come could make us sick, hospitalise us, or even kill.

Urban trees are one of our best methods of protecting ourselves. Suburbs with greater tree canopy cover are significantly cooler. Trees shade the ground and their foliage emits water, which cools the air. Good canopy cover can cut temperatures by up to 6℃.

So, it’s not good news for us that our urban trees are looking stressed. Worse is the fact that our urban tree canopy is actually declining, due to bad urban planning of new suburbs with no space for canopy trees coupled with tree loss from subdivisions or apartment builds. Our state governments talk about this in their planning documents, but efforts to correct the problem don’t seem to be working.

What happens in hot summers with fewer trees? More air conditioner use, sending energy demand and electricity bills soaring.

We can hope this summer acts as a wake up call about the importance of healthy urban trees as we head into ever-hotter years.

What Can You Do For Your Trees?

It’s worth looking after your own trees in anticipation of the tough summer ahead.

As soils are already drying out, keep up the moisture and add quality mulch under trees to a good depth.

The longer you can keep them healthy and stress free, the more likely trees are to be able to cope with the summer stress and insect attacks.

If water restrictions are imposed in your town or city, it’s likely irrigating trees and gardens will be the first activity restricted.

If your plants have been kept stress free as long as possible, they are more likely to survive.

An irony here is that if trees are water-stressed, many species will start to defoliate by shedding leaves. That means we lose both shade and transpirational cooling when we could use them most.

Councils, state governments and water authorities face a dilemma in these situations. Save the water for human use? Or keep urban trees alive and reduce the risk of heat illness and death?

Time To Value Our Urban Trees

What this summer will show is the need for local and state governments to place greater value on their urban forests and canopy cover.

In many places, urban canopy cover is dropping by about 1-1.5% per year. Many tree removals are thoughtless and unnecessary.

Sometimes, these losses provoke outcry. Adelaide, for instance, has been losing an estimated 75,000 trees a year in recent years. That prompted a parliamentary inquiry into how to better protect urban forests.

For things to change for the better, our local governments need the ability to protect mature trees in the front and back yards of developed sites and to set out minimum areas of green space and numbers of canopy trees for new developments.

In most states, giving councils these powers would require changes to state planning laws. But without them, the urban forest and canopy cover of most major cities, regional centres and country towns will continue to decline.

With proper planning, we can have both new housing and canopy trees. If we simply aim to maximise housing, our towns and suburbs will be economically and environmentally unsustainable.

So when you see sick trees on our streets this spring, see them as a symptom. We need to value them. We would most certainly notice if they were gone. ![]()

Gregory Moore, Senior Research Associate, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If we protect mangroves, we protect our fisheries, our towns and ourselves

Mangroves might not look like much. Yes, they can have strange aerial roots. Yes, they’re surrounded by oozing mud.

But looks can be deceiving. These remarkable shrubs and trees are nurseries for many species of fish, shellfish and crabs. They protect our coastlines from erosion, storm surges, wind and floods. And that mud? It’s one of the best biological ways we know of to store carbon.

These ecosystem services are extremely valuable – but people often don’t notice what they offer until they’re lost to aquaculture, firewood or settlement.

Conserving mangroves by declaring parks and other protected areas seems like a logical solution. But often, nations can see protected areas as a cost, walling them off from human use, and ignoring their benefits to people.

What our new research shows is that you don’t have to choose between nature and humans. Protecting mangroves offers a win-win, given how valuable they are to coastal communities, fishers and the fight against climate change.

As nations aim to conserve 30% of their lands and waters by decade’s end, those lucky enough to have mangroves should look to their coasts.

Why Are Mangroves So Important?

Mangroves thrive on the coast, poised between land and sea. They first evolved between 100 and 65 million years ago. Each of the 65 species of mangrove is a shrub or tree which has, over time, evolved to live in salt or brackish water.

These trees are extremely resilient, surviving in low-oxygen conditions which would kill other trees. To survive, they’ve acquired adaptations such as aerial roots that can take in oxygen. These tangled roots make excellent hiding places for the creatures of land and sea, such as mudskipper fish able to survive out of water.

Their complex roots are ideal nurseries for juvenile fish, crabs and prawns by providing shelter and places to feed. In turn, these nurseries keep populations healthy, sustaining commercial fisheries and supplying direct sources of protein for coastal people.

Their robust tangles of roots protect them from the force of waves, storm surges and wind. In turn, this helps people, who can shelter behind this green wall.

Mangroves also act as a natural way to tackle climate change. Their roots trap sediment, burying inorganic and organic carbon in the process. They also store carbon in their biomass. Overall, these sea forests store carbon at almost three times the rate of tropical rainforests, twice that of peat swamps, and almost seven times the rate of seagrasses.

Protecting Mangroves Needs A Different Approach

While mangroves give us a host of benefits, many of these only become apparent when these ecosystems are gone.

Unfortunately, mangroves are often cleared to make way for aquaculture, farming and human settlements, or for firewood. An estimated 20–35% of the world’s mangroves have been lost since 1980. In better news, losses have declined significantly. We now lose around 0.13% per year.

Protected areas work well as a way to cut mangrove losses. When a government sets out to create these areas, the aim is usually to protect biodiversity while minimising conflict with human use.

In our research, we found the world’s network of protected areas isn’t doing a great job in protecting either mangrove biodiversity or the ecosystem benefits mangroves give us. In fact, it’s no better than just picking areas at random.

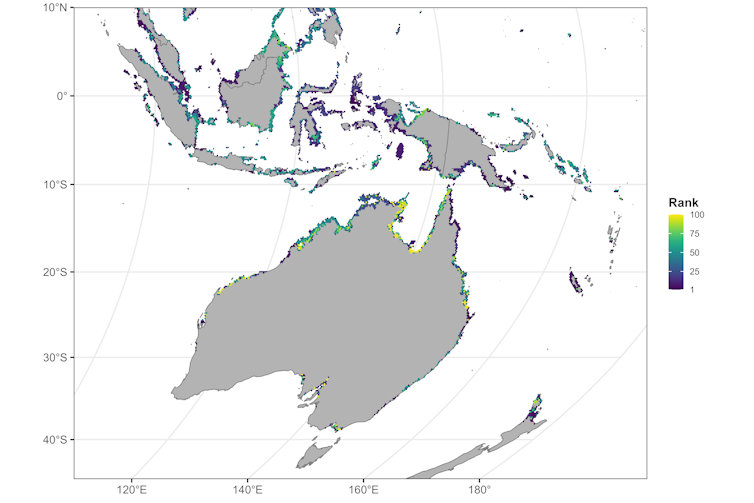

That means high-priority mangrove forests important for both biodiversity and ecosystem services are not being properly conserved. Clever expansion of the current network could solve the problem. At present, parks and other protected areas cover about 13% of the world’s mangrove forests, which are clustered around the tropics.

Boosting this to 30% – in line with the biodiversity conservation target agreed to by 196 nations last year – would reap benefits. Our research suggests it would safeguard houses and infrastructure worth A$25.6 billion, protect six million people against coastal flooding, and store over one billion extra tonnes of carbon. Also, fishers would gain an extra 50 million days of successful fishing a year.

Even better – we found optimising conservation of both biodiversity and ecosystem services needed only 3–9% more area protected compared to mangrove protection areas based on saving species alone.

Protect Mangroves In Asia And Oceania

Mangrove forests urgently needing protection are almost all in Asia (63% of the total) and Oceania (17%), where we find large biodiverse mangrove forests which support fishing industries and many coastal communities.

Indonesia is a particular hotspot, given its 17,000-odd islands are often ringed by mangroves. Mangroves in India, Vietnam and Papua New Guinea also need better protection.

Australia does reasonably well. Around 18% of our mangroves are protected, above the global average of 13.5%. Over 20% of the areas we have flagged are high-priority for mangrove conservation are already protected. Even so, expanding the protected area network would be a good move, as Australian mangroves are some of the world’s most biodiverse and carbon-rich.

Mangroves in parts of northern Queensland need better protection. Some mangroves are already protected by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Reserve, but there are still large unprotected tracts.

Mangroves around Darwin and Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory need expanded protected areas, as do those on the coast between the Pilbara and the Kimberley in Western Australia.

Too often, protecting nature is seen as a cost to society. What our modelling shows is that we can have a win-win. By protecting the most precious areas of mangrove, we can protect human communities and wider biodiversity at a stroke.![]()

Alvise Dabalà, Research associate, The University of Queensland; Anthony Richardson, Professor, The University of Queensland; Daniel Dunn, A/Prof of Marine Conservation Science & Director of the Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science (CBCS), The University of Queensland, and Jason Everett, Senior research fellow, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A successful energy transition depends on managing when people use power. So how do we make demand more flexible?

Chris Briggs, University of Technology SydneyEnergy security concerns are mounting as renewable projects and transmission lines are delayed.

In New South Wales, for instance, the government has flagged it may defer the closure of Eraring coal power station beyond 2025.

NSW has other new policies to “get the energy transition back on track”. These include expanding “customer energy resources”, such as solar panels and batteries, and increasing “demand flexibility” (broadly, using smart technology to shift the times when businesses and homes use power).

With more variable supply from solar and wind energy, demand flexibility is a cheaper and cleaner way to keep the electricity grid stable.

Modelling for the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) shows this approach could save consumers up to A$18 billion to 2040. Shifting demand can avoid:

- higher-priced power use at the end of the day

- building new poles and wires to increase network capacity to meet peak demand

- paying coal plants to stay open.

What Does Flexible Demand Involve?

Examples of flexible demand include:

shifting water heating from night-time (mostly coal-powered) to daytime (using solar)

reducing temperatures in commercial coolrooms using solar power in the middle of the day, then switching chillers off in the late afternoon until they return to standard refrigeration temperatures

remotely controlling air conditioners to turn them down when the grid is under stress. Households get paid and don’t notice if the aircon is briefly turned down, but across many homes it can make a big difference.

The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) estimates NSW needs an extra 191 megawatts (MW) of capacity to maintain reliability when Eraring closes.

Another way to cover that capacity shortfall is more flexible demand. Queensland already has almost 150MW of remote-controlled air conditioning. Other types of demand management that Queensland grid operators can call on total about 900MW.

In Western Australia, a newly signed contract will provide 120MW of demand flexibility.

So What Are The Obstacles To More Flexible Demand?

ARENA commissioned the Institute for Sustainable Futures to review the pilot demand flexibility projects it has funded. Many didn’t deliver as much as hoped.

Sometimes, this was because businesses were too busy with day-to-day operations or payments for households were too low to catch their interest. But often it’s a matter of putting policies, technical standards and regulations in place to make demand management seamless and efficient.

ARENA has spent about $180 million on 55 projects with at least some focus on flexible demand. They include air conditioning, pool pumps and hot water systems in homes, commercial building air conditioning and electric vehicle charging.

4 Ways To Increase Demand Flexibility

What do these projects tell us about how to increase demand flexibility?

1. Better technical standards

The technical standards required of manufacturers often don’t ensure devices can be used to shape demand. Many air-conditioners couldn’t be controlled in ARENA pilots.

There is also no technical standard for “inter-operability” of devices within homes. Batteries, hot water systems and other devices with different companies’ technologies don’t always work well together.

Vehicle-to-grid charging for electric vehicles will be the largest opportunity for demand flexibility, but there is no common technical standard. It’s vital to have one before the mass uptake of electric vehicles.

Outside Victoria, smart meters that provide real-time information on home energy use are rare. The Australian Energy Market Commission has recommended governments accelerate roll-out of smart meters to 100% by 2030.

2. Simpler measurement systems

The measurement systems to calculate payments for demand flexibility are a barrier to expansion. It’s tricky as you need to measure how much electricity was used relative to what would otherwise have occurred.

ARENA pilots that tried to precisely measure residential demand flexibility found it was financially unviable at the smaller scale.

The system used for AEMO’s Wholesale Demand Response Mechanism (WDRM) effectively limits participation to businesses with predictable, flat consumption profiles. This excludes as much as 80–90% of sites. International measurement models could be trialled here to open up participation.

3. More certainty about payments

Earnings from providing demand flexibility depend on weather, market prices and so on. This uncertainty makes it hard to get businesses to sign up.

Overseas, some energy markets guarantee payment for making demand flexibility available. These have the highest participation.

The federal government is consulting on a capacity investment scheme. Because it will have the same measurement system as the current mechanism, participation is likely to be limited.

4. Fresh policy approaches

Businesses that sign up under the Wholesale Demand Response Mechanism make bids in the National Electricity Market to be paid for reducing their power use when demand and prices are high. This should reduce prices for all consumers and improve energy security when the grid is under stress. However, it has attracted only one participant – mainly due to the complex measurement system – and isn’t open to households.

Another incentive scheme for electricity networks to invest in demand management is chronically under-used.

There are simpler alternatives that have worked before. The national Renewable Energy Target and state energy efficiency certificate schemes fund rooftop solar or energy retrofits based on average output or energy savings from past experience. These simple calculations offer a relatively stable incentive, which could work for demand flexibility.

NSW’s Peak Demand Reduction Scheme, launched last year, could provide a model for using certificate schemes to boost demand flexibility.

Get Serious About Demand Flexibility

The focus of NSW’s development of a customer energy resources policy appears to be on “virtual power plants”. These co-ordinate household solar and battery systems to store solar power and export to the grid when it’s most needed.

Batteries are part of the solution, but cheaper options exist. An electric water heater with a 300-litre tank can store as much energy as a second-generation Tesla battery at much less cost.

Modelling for ARENA finds hot water systems could store as much energy as more than 2 million household batteries. Retrofitting these systems will spread savings more widely to include low-income households as well as those that can afford a battery.

It’s time we got serious about developing a holistic demand flexibility strategy. It will be cheaper and cleaner than paying coal plants to stay open.![]()

Chris Briggs, Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

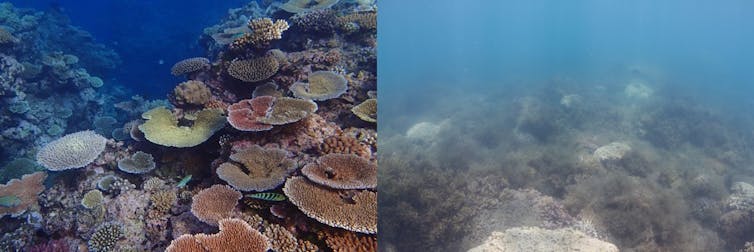

There’s a hidden source of excess nutrients suffocating the Great Barrier Reef. We found it

The Great Barrier Reef is one of Australia’s most important environmental and economic assets. It is estimated to contribute A$56 billion per year and supports about 64,000 full-time jobs, according to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation. However, the reef is under increasing pressure.

While much public attention is focused on the impacts of climate change on the Great Barrier Reef and the debate around its endangered status, water quality is also crucial to the reef’s health and survival.

Our new study, published today in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, found that previously unquantified groundwater inputs are the largest source of new nutrients to the reef. This finding could potentially change how the Great Barrier Reef is managed.

Too Much Of A Good Thing

Although nitrogen and phosphorous are essential to support the incredible biodiversity of the reef, too much nutrient can lead to losses of coral biodiversity and coverage. It also increases the abundance of algae and the ability of coral larvae to grow into adult coral, and impacts seagrass coverage and health, which is crucial for fisheries and biodiversity.

Nutrient enrichment can also promote the breeding success of crown-of-thorns starfish, whose increasing populations and voracious appetite for corals have decimated parts of the reef in recent decades.

What are the sources of nutrients driving the degradation of the reef? Previous studies have focused on river discharge. According to one estimate, there has been a fourfold increase in riverine nutrient input to the Great Barrier Reef since pre-industrial times.

This past focus on rivers has emphasised reducing surface water nutrient inputs through changing regulations for land-clearing and agriculture, while neglecting other potential sources.

However, the most recent nutrient budget for the Great Barrier Reef found river-derived nutrient inputs can account for only a small proportion of the nutrients necessary to support the abundant life in the reef. This imbalance suggests large, unidentified sources of nutrients to the reef. Not knowing what these are may lead to ineffective management approaches.

With recent government funding of more than $200 million to tackle water quality on the reef which is largely focused on managing river water inputs, it is crucial to make sure other nutrient sources are not overlooked.

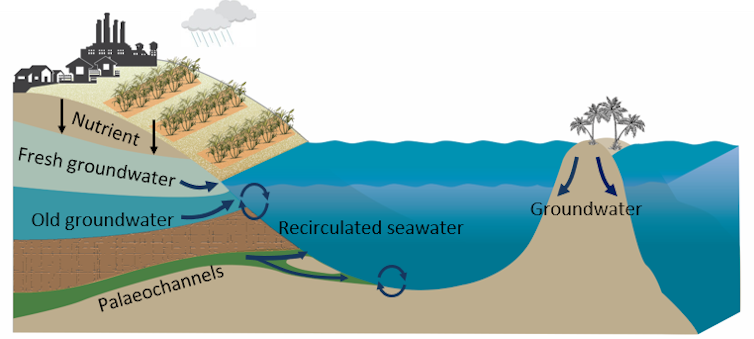

We Found A New Nutrient Source

Our research team decided to try and track down this missing source of nutrients.

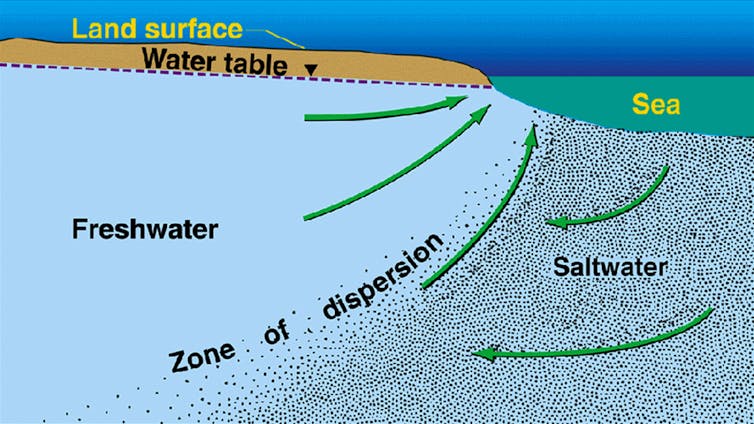

We used natural tracers to track groundwater inputs off Queensland’s coast. This allows us to quantify how much invisible groundwater flows into the Great Barrier Reef, along with the nutrients hitching a ride with this water. Our findings indicate that current efforts to preserve and restore the health of the reef may require a new perspective.

Our team collected data from offshore surveys, rivers and coastal bores along the coastline from south of Rockhampton to north of Cairns. We used the natural groundwater tracer radium to track how much nutrient is transported from the land and shelf sediments via invisible groundwater flows.

We found that groundwater discharge was 10–15 times greater than river inputs. This meant roughly one-third of new nitrogen and two-thirds of phosphorous inputs came via groundwater discharge. This was nearly twice the amount of nutrient delivered by river waters.

Past investigations have revealed that groundwater discharge delivers nutrients and affects water quality in a diverse range of coastal environments, including estuaries, coral reefs, coastal embayments and lagoons, intertidal wetlands such as mangroves and saltmarshes, the continental shelf and even the global ocean.

In some cases, this can account for 90% of the nutrient inputs to coastal areas, which has major implications for global biologic production.

Nevertheless, this pathway remains overlooked in most coastal nutrient budgets and water quality models.

A Paradigm Shift Needed?

Our results suggest the need for a strategic shift in management approaches aimed at safeguarding the Great Barrier Reef from the effects of excess nutrients.

This includes better land management practices to ensure fewer nutrients are entering groundwater aquifers. We can also use ecological (such as seaweed and bivalve aquaculture, enhancing seagrass, oyster reefs, mangroves and salt marsh) and hydrological (increasing flushing where possible) practices at groundwater discharge hotspots to reduce excess nutrients in the water column.

The reuse of nutrient-rich groundwater for agriculture also needs to be explored as it represents an untapped and inexpensive nutrient source.

Importantly, unlike river outflow, nutrients in groundwater can be stored underground for decades before being discharged into coastal waters. This means research and strategies to protect the reef need to be long-term. The potential large lag time may lead to significant problems in the coming decades as the nutrients now stored in underground aquifers make their way to coastal waters regardless of changes to current land use practices.

The understanding and ability to manage the sources of nutrients is pivotal in preserving global coral reef systems.

While we need to reduce the impact of climate change on this fragile ecosystem, we also need to adjust our policies to manage nutrient inputs and safeguard the Great Barrier Reef for generations to come.![]()

Douglas Tait, Senior Researcher, Southern Cross University and Damien Maher, Professor, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Nullarbor’s rich cultural history, vast cave systems and unique animals all deserve better protection

The Nullarbor is one of Australia’s iconic natural places. It’s renowned as a vast and mostly treeless plain. But hidden beneath this ancient landscape is an immense network of caves.

These caves are part of the world’s largest contiguous limestone karst system. This karst landscape, created by water dissolving the limestone, spans some 200,000 square kilometres.

The caves are as important for their geological value and what they can teach us about Australia’s past, as they are for the unique animals they house, the fossils they hold and their beautiful and unusual cave decorations.

The Nullarbor Plain is the land of the Mirning people. Their Dreaming, associated with the Great Australian Bight, recalls oral histories of changing sea levels.

The Mirning have actively traversed the plain for millennia. Their artwork in its caves, extensive flint mining and artefacts scattered over its surface provide evidence of their presence.

But it’s only in modern times that the plain’s natural values have been threatened. The threats include invasive species, such as foxes, cats, camels and buffel grass, climate change and, perhaps most detrimentally, human activities. Mining, wildlife poaching, uncontrolled tourism and large-scale development, for example a proposed green energy project, could impact much of what makes the Nullarbor Plain so precious.

Greater recognition of the Nullarbor’s superlative natural features is needed to change a common perception that there is nothing out there, and to ensure the preservation of unprotected areas in the region.

A Place Of Spectacular Cliffs And Caves

Sloping gently seawards, the Nullarbor terminates spectacularly at the Great Southern Scarp, possibly the world’s longest cliff line.

The caves scattered across the plain vary from small caves to those that extend for many kilometres.

The smaller caves include blowholes, narrow smooth-walled vertical tubes named for the breathing in and out of air as atmospheric pressure changes. Sometimes the air movement feels like a gale.

Some of the deep caves contain lakes of clear, salty, blue-green water. Flooded passages lead away from these lakes. Only cave divers can reach these passages, which include the longest underwater cave systems in Australia.

Dating of stalactites and stalagmites confirms most of the caves were formed in the Early Pliocene, around 5 million to 3 million years ago. At this time, the region was much wetter and home to forests of eucalypts. It was very different from the sparse plain we see now.

Home To Unique And Vulnerable Life

With low light levels and relatively stable temperatures and humidities, caves are extreme environments.

In remote sections of some caves fragile curtains of bacterial colonies known as slime curtains hang from the roof and walls. These are unique to the Nullarbor.

Many animals found in caves can survive above ground. But some, known as troglobites, have become so specialised they can only survive underground. They often lack pigment, have elongated limbs and highly reduced or absent eyes.

One such group of cave specialists are the blind cave spiders of the genus Troglodiplura. These large, enigmatic spiders occur only on the Nullarbor Plain. And most species are known from single caves.

They are the only cave-adapted mygalomorph spiders (the primitive spiders, such as the funnel-web and trapdoor spiders) known from Australia. As with many cave-dwelling animals, we know very little about them.

The highly specialised and diverse animals that live in underground water, known as stygofauna, are a good example of this. Only a very small fraction of the species have been scientifically described.

Many such animals are restricted to tiny geographic areas. Some occur only in a single cave.

This means these species are at exceptionally high risk from threats to them or the fragile cave environment they rely on. These threats include predation by foxes, changes to water availability within the cave, or damage to the cave structure.

Given how little we know about cave fauna, it’s unfortunately likely extinctions are occurring unrecorded and undocumented.

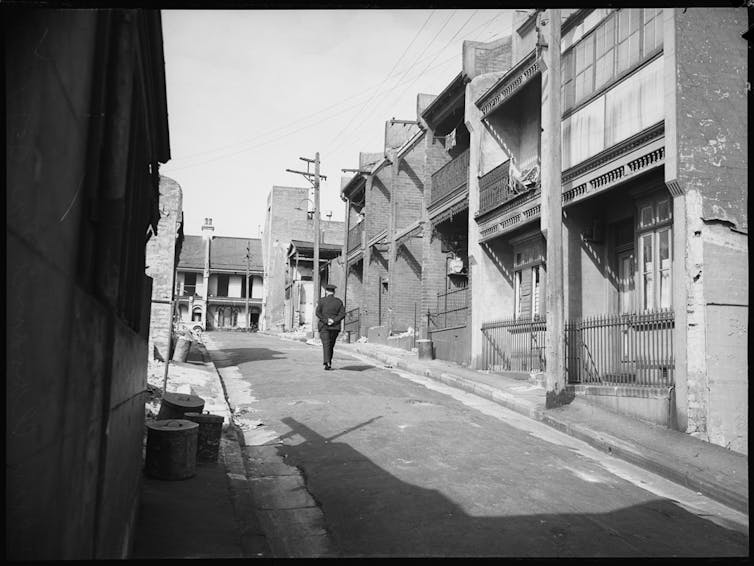

Nature’s Time Capsules