inbox and environment news: Issue 602

October 22 - 28, 2023: Issue 602

Narrabeen Lagoon Entrance Clearing Works: September To October Pictures By Joe Mills

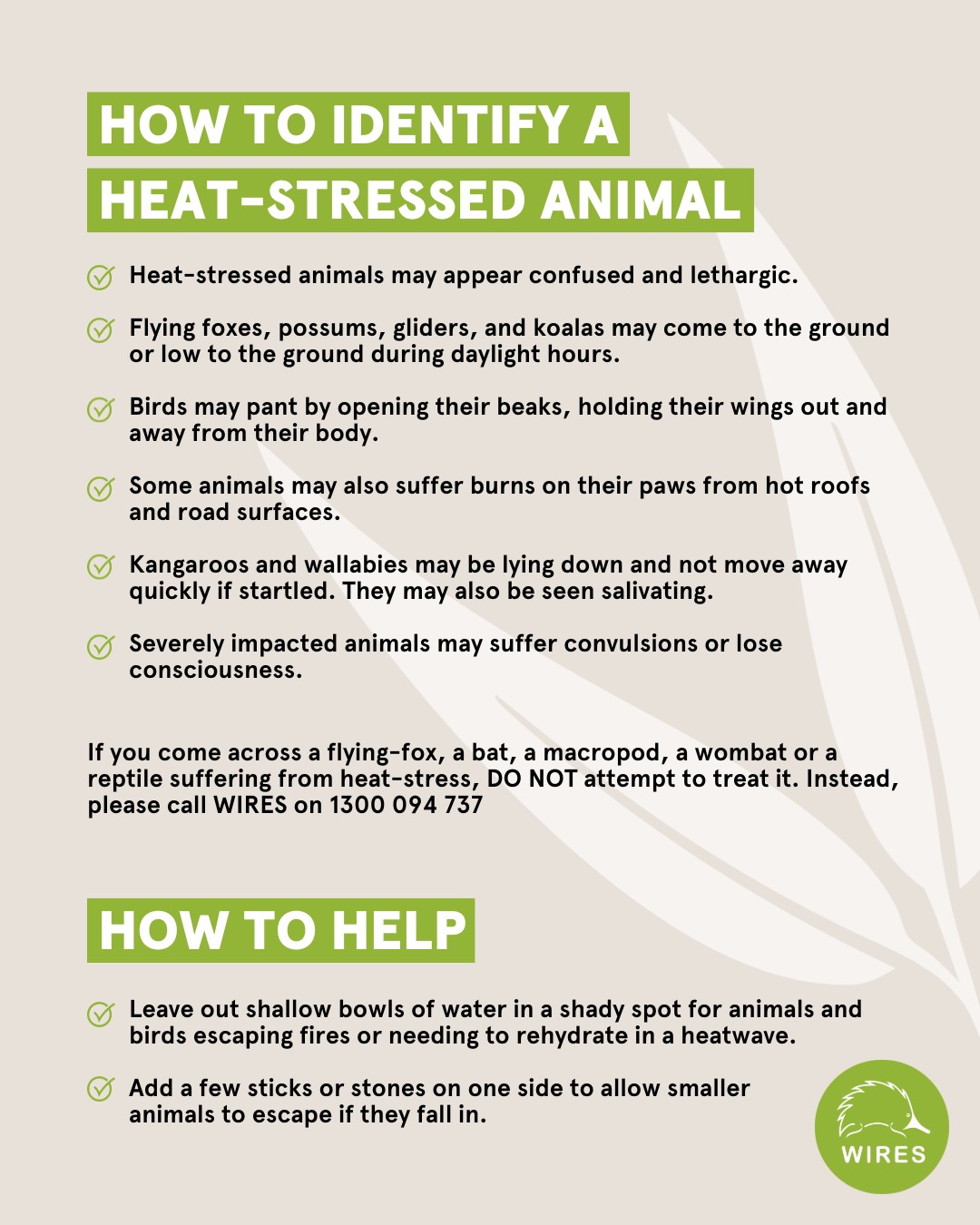

Please Look Out For Wildlife During This Spring Heat

Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Next Rescue And Care Course Commences October 28

Bushwalk Fundraiser

- Friday 10 November

- Friday 8 December

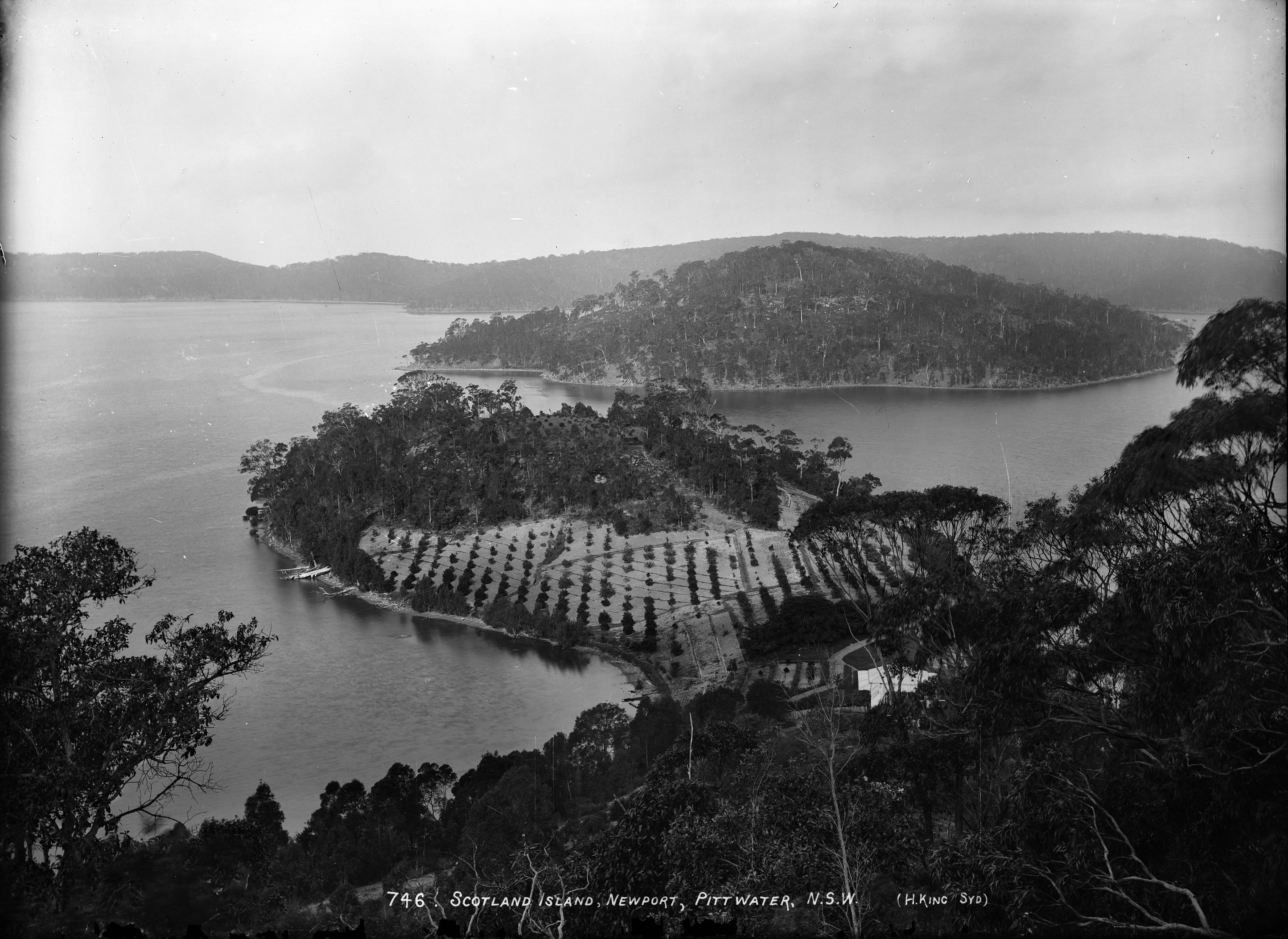

'Scotland Island, Newport, Pittwater, N.S.W.', photo by Henry King, Sydney, Australia, c. 1880-1886. and section from to show cottage on neck of peninsula at western end with no chimneys through roof. From Tyrell Collection, courtesy Powerhouse Museum

𝗞𝗶𝗺𝗯𝗿𝗶𝗸𝗶 𝗥𝗲𝘀𝗼𝘂𝗿𝗰𝗲 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗼𝘃𝗲𝗿𝘆 𝗖𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗿𝗲 𝗶𝗻𝘃𝗶𝘁𝗲𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗺𝘂𝗻𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝘁𝗼 𝗼𝘂𝗿 𝗢𝗽𝗲𝗻 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟮𝟬𝟮𝟯 𝗮𝘁 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗛𝗨𝗕 - 𝗞𝗶𝗺𝗯𝗿𝗶𝗸𝗶.

Highlighting the four resident not-for-profit organisations: Peninsula Seniors Toy Recyclers, Bikes4Life, Boomerang Bags Northern Beaches - Kimbriki, Reverse Garbage and their dedicated volunteers.

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group Begins

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

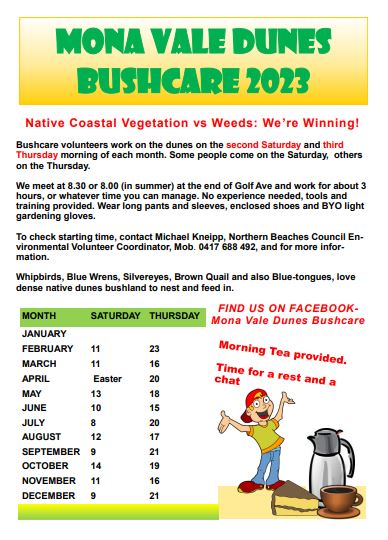

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Sea-Lovers Urged To Help To Save Sea Turtles This Nesting Season

.jpg?timestamp=1697895535957)

.jpg?timestamp=1697895565175)

- walk your local beach early in the morning, as sea turtles generally nest during the night.

- keep your eyes peeled for any tracks in the sand, which are usually 80–100 cm wide and can sometimes be mistaken for tire tracks.

- take your phone with you so you can quickly call NSW TurtleWatch or NPWS if you see any signs of turtles, tracks or a nest.

$16 Million For Crown Reserve Improvements

- Maintaining or increasing public access, amenity and use of a reserve.

- Supporting social cohesion and participation in community life.

- Enabling people with accessibility requirements or living with a disability to be included.

- Delivering a service or infrastructure to enable Aboriginal people to access, care for or protect and manage land.

- Conserving heritage values and/or natural values of a reserve.

- Creating employment or business opportunities.

Funding To Make Apartment Buildings Ready For EVs

Have Your Say On 10-Year Trout Cod Recovery Roadmap

The Trout Cod (Maccullochella macquariensis) or bluenose cod, is a large predatory freshwater fish of the genus Maccullochella and the family Percichthyidae, closely related to the Murray cod. It was originally widespread in the south-east corner of the Murray-Darling river system in Australia, but is now an endangered species.

The Trout Cod (Maccullochella macquariensis) or bluenose cod, is a large predatory freshwater fish of the genus Maccullochella and the family Percichthyidae, closely related to the Murray cod. It was originally widespread in the south-east corner of the Murray-Darling river system in Australia, but is now an endangered species.Joint Watering Action To Support Native Fish And Waterbirds Ahead Of Predicted Dry Times

.jpg?timestamp=1697896397190)

State Government Announces $128 Million For Communities In Central-West Orana REZ

- public infrastructure upgrades

- housing and accommodation

- training and employment programs

- health and education programs

- support for energy efficiency and local rooftop solar

- initiatives for First Nations people.

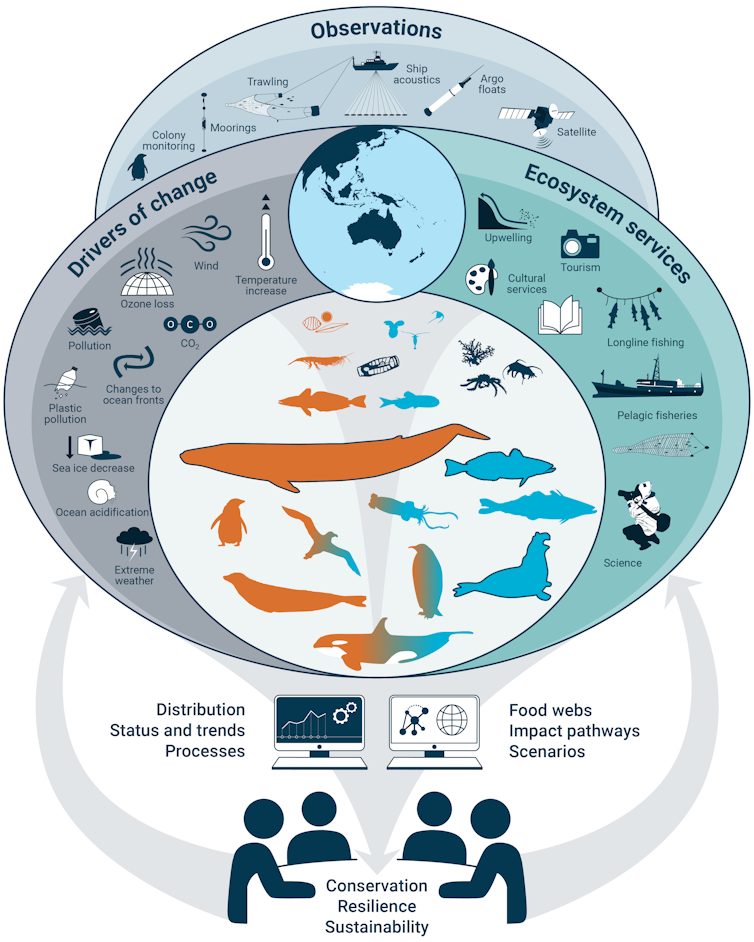

More than 200 scientists from 19 countries want to tell us the Southern Ocean is in trouble

While the Southern Ocean around Antarctica has been warming for decades, the annual extent of winter sea ice seemed relatively stable – compared to the Arctic. In some areas Antarctic sea ice was even increasing.

That was until 2016, when everything changed. The annual extent of winter sea ice stopped increasing. Now we have had two years of record lows.

In 2018 the international scientific community agreed to produce the first marine ecosystem assessment for the Southern Ocean. We modelled the assessment process on a working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). So the resulting “summary for policymakers” being released today is like an IPCC report for the Southern Ocean.

This report can now be used to guide decision-making for the protection and conservation of this vital region and the diversity of life it contains.

Why Should We Care About Sea Ice?

Sea ice is to life in the Southern Ocean as soil is to a forest. It is the foundation for Antarctic marine ecosystems.

Less sea ice is a danger to all wildlife – from krill to emperor penguins and whales.

The sea ice zone provides essential food and safe-keeping to young Antarctic krill and small fish, and seeds the expansive growth of phytoplankton in spring, nourishing the entire food web. It is a platform upon which penguins breed, seals rest, and around which whales feed.

The international bodies that manage Antarctica and the Southern Ocean under the Antarctic Treaty System urgently need better information on marine ecosystems. Our report helps fill this gap by systematically identifying options for managers to maximise the resilience of Southern Ocean ecosystems in a changing world.

An Open And Collaborative Process

We sought input from a wide range of people across the entire Southern Ocean science community.

We sought to answer questions about the state of the whole Southern Ocean system - with an eye on the past, present and future.

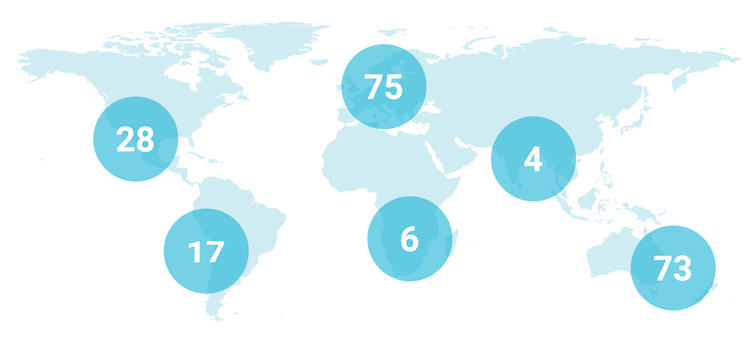

Our team comprised 205 authors from 19 countries. They authored 24 peer-reviewed papers. We then distilled the findings from these papers into our summmary for policymakers.

We deliberately modelled the multi-disciplinary assessment process on a working group of the IPCC to distill the science into an easy-to-read and concise narrative for politicians and the general public alike. It provides a community assessment of levels of certainty around what we know.

We hope this “sea change” summary sets a new benchmark for translating marine research into policy responses.

So What’s In The Report?

Southern Ocean habitats, from the ice at the surface to the bottom of the deep sea, are changing. The warming of the ocean, decline in sea ice, melting of glaciers, collapse of ice shelves, changes in acidity, and direct human activities such as fishing, are all impacting different parts of the ocean and their inhabitants.

These organisms, from microscopic plants to whales, face a changing and challenging future. Important foundation species such as Antarctic krill are likely to decline with consequences for the whole ecosystem.

The assessment stresses climate change is the most significant driver of species and ecosystem change in the Southern Ocean and coastal Antarctica. It calls for urgent action to curb global heating and ocean acidification.

It reveals an urgent need for international investment in sustained, year-round and ocean-wide scientific assessment and observations of the health of the ocean.

We also need to develop better integrated models of how individual changes in species along with human impacts will translate to system-level change in the different food webs, communities and species.

What’s Next?

Our report will be tabled at this week’s international meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources in Hobart.

The commission is the international body responsible for the conservation of marine ecosystems in the Southern Ocean, with membership of 26 nations and the European Union.

It is but one of the bodies our new report can assist. Currently assessments of change in habitats, species and food webs in the Southern Ocean are compiled separately for at least ten different international organisations or processes.

The Southern Ocean is a crucial life-support system, not just for Antarctica but for the entire planet. So many other bodies will need the information we produced for decision-making in this critical decade for action on climate, including the IPCC itself.

Beyond the science, the assessment team has delivered important lessons about how coordinated, collaborative and consultative approaches can deliver ecosystem information into policymaking. Our first assessment has taken five years, but this is just the beginning. Now we’re up and running, we can continue to support evidence-based conservation of Southern Ocean ecosystems into the future. ![]()

Andrew J Constable, Adviser, Antarctica and Marine Systems, Science & Policy, University of Tasmania and Jess Melbourne-Thomas, Transdisciplinary Researcher & Knowledge Broker, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The original and still the best: why it’s time to renew Australia’s renewable energy policy

Tim Nelson, Griffith University; Joel Gilmore, Griffith University, and Tahlia Nolan, Griffith UniversityThis article is part of a series by The Conversation, Getting to Zero, examining Australia’s energy transition.

If Australia is to meet its commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 43% below 2005 levels by 2030, we need to cut emissions faster. Even if all current government policy commitments are achieved – an unlikely outcome given delays in implementation – emissions are still projected to be only 40% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Last year the federal government announced that 82% of all electricity production would come from renewable energy by 2030. This was a crucial step. To have any chance of hitting our overall emission reduction targets, we must speed up the rollout of renewable energy.

Several experts, such as Tony Wood at the Grattan Institute and the Clean Energy Council are calling on governments to consider using the Renewable Energy Target (RET) to accelerate investment in new renewable supply. Why are these experts recommending the RET as a policy option?

A Brief History Of Renewable Energy In Australia

At the turn of the century Australia had almost no wind or solar energy generation. In 2001, the Howard government recognised the potential benefits of renewables and introduced the RET. The target, which was expanded and reformed by the Rudd and Abbott governments, has two elements:

the Large-Scale Renewable Energy Target, which requires retailers to buy a set percentage (currently about 15%) of their energy from renewable producers through the purchase of a Large-Scale Generation Certificate

the Small-Scale Renewable Energy Scheme, which provides an upfront subsidy to households and small businesses that install their own rooftop solar panels.

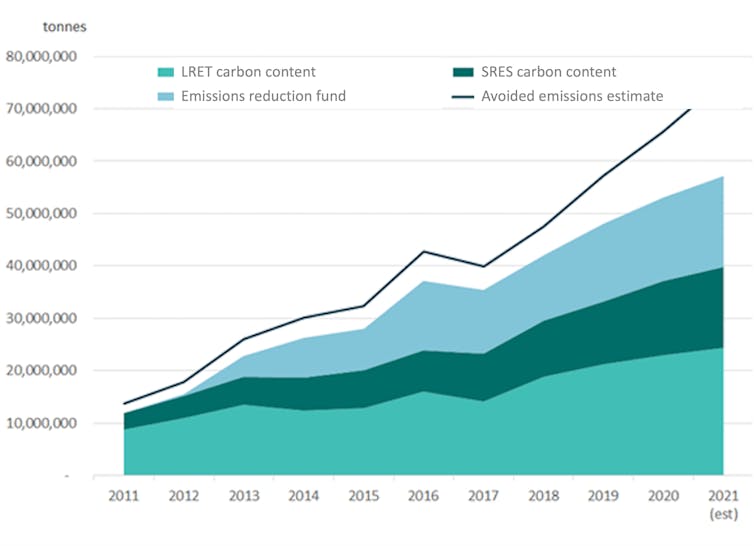

Over the past two decades, the RET has been by far the most effective of all Australia’s climate initiatives. It has led to an additional 40 gigawatts (the capacity of around 20 Liddell power stations) of new solar and wind generation. It has lifted Australia’s renewable generation from almost nothing other than hydro (from Hydro Tasmania and Snowy Hydro) in 2000 to nearly 37% of all electricity today.

Between 2011 and 2021, the RET accounted for more than half of Australia’s greenhouse gas abatement, delivering by 2021 40 million metric tonnes (Mt) out of about 75 Mt. Over a decade that’s the equivalent of retiring two very large coal-fired power stations each year (see chart below).

The RET succeeded for two reasons. First, its targets extend all the way through to 2030, creating certainty for investors. Second, it created a market that encourages retailers to purchase the lowest-cost large-scale generation certificates. In purchasing a certificate, the retailer pays the difference between the cost of a project and what its generated power earns on the market.

That approach has diversified our renewable energy mix by making it easier to compare different technologies. For example, a wind farm might cost more to build than a solar farm but it can potentially earn more on the market by generating at the right time of day or night. A greater diversity of renewable energy sources means more reliable generation.

Why Has The Boom In Renewables Investment Stalled?

The bad news is that while investment in small-scale solar photovoltaic continues to grow, investment in large-scale renewables has largely stalled. There are two main reasons why.

First, Australia must build more transmission infrastructure. We have great renewable energy resources but we need new transmission lines to take that energy to homes and businesses. Governments have recognised this and are prioritising new Renewable Energy Zones, with the Commonwealth providing substantial funding through its Rewiring the Nation package.

But the second reason for the stalled investment is less well known. The target of 33 terrawatt hours under the Large-Scale Renewable Energy Target was largely achieved in 2020 and since then has not been increased. The current legislated target is about 15%, well below the government’s commitment to reach 82% by 2030. Why did governments pivot away from the successful RET policy?

In the late 2010s, the Commonwealth government was not interested in increasing renewable energy targets. So state governments keen to act on climate change moved away from using the RET and other market-based policies, instead creating their own policy frameworks, known as Contracts-for-Difference.

Under these frameworks, state governments hold reverse auctions and award solar and wind projects a contract for a guaranteed price for their energy for 15–20 years.

Government contracts-for-difference can be a useful tool to assist new technologies, such as offshore wind, to enter the market. But they have significant limitations when they are used to deploy mature technologies such as solar and wind.

The most obvious problem is that, in contrast to a market framework such as the Large-Scale Renewable Energy Target, under contracts-for-difference the government becomes the only market for renewable energy. The government assumes the risk of any project, freeing operators from the need to efficiently locate and run their projects. If a project fails, the public pays the cost in higher power prices or taxes.

Moreover, when government is buying the power, it naturally often goes for the cheapest option, thereby usually favouring solar and narrowing our renewable energy mix. And a generator has no incentive to sell its electricity to households and businesses. The result is that investors hold off building new projects, waiting instead to be awarded a contract-for-difference.

This dynamic is stalling investment even as coal generators near the end of their useful lives and the market demand for both energy and firming capacity grows.

Governments Working Together To Get Investment Flowing

But there is reason to be optimistic. The states and the Commonwealth all now agree on the need to rapidly decarbonise the electricity sector by deploying renewables, transmission and storage. Now the states have the opportunity to work with the Commonwealth to incorporate their different frameworks into a nationally consistent, market-based approach built on the Large-Scale Renewable Energy Target.

The simplest approach, which would create a pivot back to market-based frameworks, would be to legislate to increase that target each year to achieve a linear growth from current renewable energy levels to 82% in 2030.

Under that solution, history suggests investors would rush to capture their share of the target. Investors and energy retailers would work together to find the right mix of technologies to deliver the lowest-cost power to consumers.

A national 82% renewable energy target also ensures that as other sectors use electrification to decarbonise, they will have access to clean energy. Without a target, electrification may lead to use of high-emissions coal power.

Under our proposal, state governments could still pursue their own objectives, such as supporting projects in a particular region, but they could align their policy frameworks with the RET by funding the cost of Large-Scale Generation Certificates rather than entire renewable energy projects.

If the electricity sector does not reach 82% by 2030, other sectors will have to do more to deliver our legislated 43% reduction in emissions by 2030. This is likely to be more costly and unnecessarily increase pressure on our trade-exposed industries, which would be required to reduce emissions more quickly at higher cost.

No Australian emission reduction policy matches the success of the Renewable Energy Target. By working together and aligning their renewable energy policies with the target, Commonwealth and state governments can get Australia’s renewable energy investment back on track, providing us with a reliable, competitive and clean electricity system by 2030 and beyond.![]()

Tim Nelson, Associate Professor of Economics, Griffith University; Joel Gilmore, Associate Professor, Griffith University, and Tahlia Nolan, , Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The climate impact of plastic pollution is negligible – the production of new plastics is the real problem

Karin Kvale, GNS Science; Andrew Weaver, University of Victoria, and Natalia Gurgacz, University of VictoriaThe dual pressures of climate change and plastic pollution are frequently conflated in the media, in peer-reviewed research and other environmental reporting.

This is understandable. Plastics are largely derived from fossil fuels and the burning of fossil fuels is the major driver of human-caused climate change.

The window for cutting emissions to keep warming at internationally agreed levels is closing rapidly and it seems logical to conclude that any “extra” fossil carbon from plastic contamination will be a problem for the climate.

Our research examines this question using an Earth system model. We found carbon leaching out of existing plastic pollution has a negligible impact. The bigger concern is the production of new plastics, which already accounts for 4.5% of total global emissions and is expected to rise.

Organic Carbon Leaching From Plastic Pollution

In nature, plants make organic carbon (carbon-hydrogen compounds) from inorganic carbon (carbon compounds not bonded with hydrogen) through photosynthesis. Most plastics are made from fossil fuels, which are organic carbon compounds. This organic carbon leaches into the environment from plastics as they degrade.

Concerns have been raised that this could disrupt global carbon cycling by acting as an alternative carbon source for bacteria, which consume organic carbon.

A key assumption in these concerns is that organic carbon fluxes and reservoirs are a major influence on global carbon cycling (and atmospheric carbon dioxide) over human timescales.

It is true that dissolved organic carbon is a major carbon reservoir. In the ocean, it is about the same amount as the carbon dioxide (CO₂) held in the pre-industrial atmosphere. But there are key differences between atmospheric CO₂ and ocean organic carbon storage. One is the climate impact.

Atmospheric CO₂ warms the climate directly, whereas dissolved organic carbon stored in the ocean is mostly inert. This dissolved organic carbon reservoir built up over many thousands of years.

When phytoplankton make organic carbon (or when plastics leach organic carbon), most of it is rapidly used within hours to days by bacteria and converted into dissolved inorganic carbon. The tiny fraction of organic carbon left behind after bacterial processing is the inert portion that slowly builds up into a natural reservoir.

Once we recognise that plastics carbon is better considered as a source of dissolved inorganic carbon, we can appreciate its minor potential for influence. The inorganic carbon reservoir of the ocean is 63 times bigger than its organic carbon store.

Plastics Carbon Has Little Impact On Atmospheric CO₂

We used an Earth system model to simulate what would happen if we added dissolved inorganic carbon to the surface ocean for 100 years. We applied it at a rate equivalent to the amount of carbon projected to leach into the ocean by the year 2040 (29 million metric tonnes per year).

This scenario likely overestimates the amount of plastics pollution. Current pollution rates are well below this level and an international treaty to limit plastic pollution is under negotiation.

We repeated the model simulation of adding plastics carbon both with strong climate warming (to see if plastics carbon might produce unexpected climate feedbacks that increase warming) and without (to see if it could alter the climate by itself). In both cases, plastics carbon only increased atmospheric CO₂ concentrations by 1 parts per million (ppm) over a century.

This is a very small increase, considering that current burning of fossil fuels is raising atmospheric CO₂ by more than 2ppm each year.

Direct Emissions From Burning Plastic

We also examined the impact of plastics incineration. We used a scenario in which all plastic projected to be produced in the year 2050 (1.1 billion metric tonnes) would be burned and directly converted into atmospheric CO₂ for 100 years.

In this scenario, we found atmospheric CO₂ increased a little over 21ppm by the year 2100. This increase is equivalent to the impact of fewer than nine years of current fossil fuel emissions.

Relative to the current continued widespread burning of fossil fuels for energy, carbon emitted from plastic waste will not have significant direct impacts on atmospheric CO₂ levels, no matter what form it takes in the environment.

However, plastics production, as opposed to leaching or incineration, currently represents about 4.5% of total global emissions. As fossil fuel consumption is reduced in other sectors, emissions from plastics production are expected to increase in proportional footprint and absolute amount.

A legally binding plastics pollution treaty, currently under development as part of the UN’s environment programme, is an excellent opportunity to recognise the growing contribution of plastics production to climate change and to seek regulatory measures to address these emissions.

Limiting the use of incineration is another climate-friendly measure that would make a small but positive contribution to the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Of course, environmental plastics pollution has many negative impacts beyond climate effects. Our work does not diminish the importance of cleaning up plastic pollution and implementing stringent measures to prevent it. But the justification for doing so is not primarily grounded in an effort to cut emissions.![]()

Karin Kvale, Senior Scientist, Carbon Cycle Modeller, GNS Science; Andrew Weaver, Professor, School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of Victoria, and Natalia Gurgacz, Graduate Student, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The dams are full for now – but Sydney will need new water supplies as rainfall becomes less reliable

When Australia last went into El Niño, we had water supply issues in Brisbane, Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne.

Are we better placed now, after three wet La Niña years? Yes and no. Take Sydney as an example. After the big wet, Greater Sydney’s dams are around 90% full, holding more than four times the volume we use in a year. But hot, dry weather can drain them surprisingly rapidly through increased demand, increased evaporation and environmental flows in rivers such as the Nepean.

Hot weather also dries out the soil in water catchments. When it rains, dry soils soak up water like a sponge, preventing it from running off to waterways. This means there’s little runoff to replenish the dams. You need very intense rainfall to overcome this.

So despite Sydney’s full dams, it will inevitably face water supply shortages if El Niño returns for several years. That’s because the city of five million is highly dependent on rainfall, which isn’t always plentiful and doesn’t always produce runoff.

To fix this problem and future-proof supplies as climate change makes rainfall less reliable, we must draw more water from desalination plants and recycling schemes.

Desalination

The combined effects of a growing population and future periods of drought will increasingly challenge our ability to meet water demand from Sydney’s dams.

In 2010, Sydney’s first large seawater desalination plant came on line. At maximum production, it can provide 90 gigalitres of drinking water per year. This is about 15% of Sydney’s annual demand.

In the past, the desal plant has been turned off and on depending on rainfall. After the Millennium Drought broke in 2009, dams began refilling. Once Sydney’s dams were 90% full in 2012, the plant was switched off. In 2019, it was turned back on as drought intensified. One problem is that it takes months to restart a mothballed desalination plant.

If the desalination plant had been operating continuously at a low rate, it could have more quickly shored up supply shortages when the drought started in 2017.

To achieve full benefit, desal plants must be used to provide ongoing service, rather than just as an emergency drought-response solution. Keeping the plant running is also an effective way of maintaining the workforce and skills required to operate the plant when it’s needed.

Water Recycling

Many cities around Australia now have desal plants. Fewer have explored purified water recycling from wastewater treatment plants due to unwarranted public scepticism.

Australia’s most significant purified recycled water project is Perth’s groundwater replenishment scheme, built to refill the aquifers on which the city draws much of its water.

Beginning in 2017, wastewater was purified and injected below ground into an important aquifer used for drinking water. The project was recently doubled in size, and now puts around 10% of Perth’s drinking water demand (28 gigalitres) back below ground annually.

By 2035, Water Corporation aims to recycle more than a third (35%) of treated wastewater.

Queensland has built but not fully used a far larger water recycling scheme, the Western Corridor Recycled Water Scheme. If it was used for drinking water as well as industrial use, it could add 80 GL a year to supply – more than a quarter of the water used by South East Queensland’s 3.8 million residents. That would be enough to replenish supplies in the region’s largest surface water storage, Lake Wivenhoe.

So What Should Sydney Do?

Sydney relies on rainfall-dependent sources for about 80% of its drinking water supply.

If dry conditions continue, the city could be running short of water within three years, according to the Greater Sydney Water Strategy.

To make sure that shortfall never arrives, Sydney needs to start building more rainfall-independent water supplies. This would help ensure full dams at the start of future droughts, allow more time to respond, and slow dam depletion rates during the drought.

Authorities could expand the desal plant. They could build a new desal plant. Or they could develop purified recycled water as an option. Each of these has costs and benefits which must be considered.

In reality, the city is likely to need all of the above. This is because there are limits to how much water can be delivered to any specific location in the supply network, so several water sources will be needed in different areas of Sydney.

The real question isn’t which one to choose. It’s which order to construct them in. ![]()

Stuart Khan, Professor of Civil & Environmental Engineering, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Doubling Sydney's Desalination Plant Capacity

Better Management Of Contaminated Land Legislation Passes NSW Parliament: Belrose's Bare Creek Cited As Example

NSW Introduces Landmark Climate Change Bill To Set Emissions Reduction Targets

- establish the Net Zero Commission – a strong, independent, expert body to monitor the state's progress to net zero. It will report annually to ensure parliamentary transparency and accountability

- put in place guiding principles for action to address climate change

- set an objective to make New South Wales more resilient to our changing climate.

Federal Government Announces $25 Million To Better Protect Nature

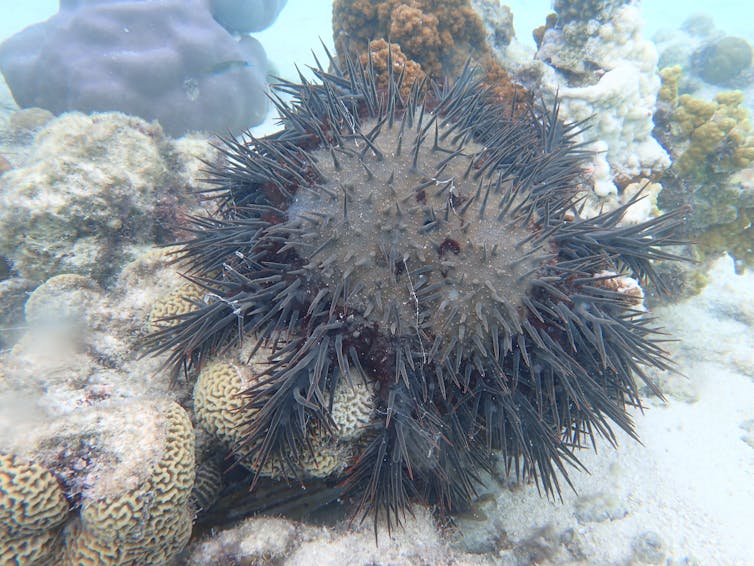

Young crown-of-thorns starfish can survive heatwaves. That’s yet more bad news for the Great Barrier Reef

You might not realise it, but the infamous crown-of-thorns starfish is native to coral reefs throughout the Indo-Pacific – including the Great Barrier Reef. When they’re fully grown, these large, thorn-covered starfish dine on hard coral polyps.

That’s fine when their populations are small. They can play an important role in keeping reefs healthy by eating fast-growing branching corals and clearing space for slower-growing coral species.

But when their populations surge, they can decimate coral reefs – and strip habitat for the myriad species relying on them.

Our coral reefs are already suffering from marine heatwaves, pollution and overfishing. Crown-of-thorns outbreaks can push reefs over the edge.

But can these starfish survive the marine heatwaves now striking the oceans more and more regularly? To find out, we worked out what temperatures the starfish could handle.

Our results suggest baby crown-of-thorns starfish are, unfortunately, very tolerant of warmer water. It’s more bad news for our sick reefs.

Keystone Predators Of The Reef

At up to 80 centimetres across, crown-of-thorns starfish are one of the largest invertebrates on coral reefs. They are named after their toxic spines.

Their large central body houses a particularly large stomach. To eat, they force their stomachs out of their mouths to cover the coral underneath their body. Once wrapped around the coral, enzymes released from the stomach liquefies the coral’s soft tissues and absorbs the nutrients – leaving only the skeleton behind.

These starfish have evolved to become keystone predators. That is, relative to their population, they have a disproportionately large ability to control how abundant other species are.

During an outbreak, their swarms can eat up to 95% of hard corals on some reefs. When this happens, not only are coral species hard hit, but the animals dependent on them as well.

When the conditions are right, these starfish can go from a very low abundance of one per hectare to upwards of a thousand in a short period of time.

They are remarkably good at reproducing. The females can spawn hundreds of millions of eggs and the males can put out 10 trillion sperm into the water during the breeding season.

Not only that, but the larvae can adjust their bodies depending on the availability of food. When food is low, the arms of the larvae grow longer. These arms have bands of little hairs used to capture food. The longer these bands are, the more food they can capture.

Despite their ability to breed like rabbits, crown-of-thorns populations go through boom and bust. Why? We don’t fully know, even after decades of intensive research and enormous expenditure. Leading theories include a boom following nutrient run-off from rivers and the removal of predatory fish. Other important predators such as the giant triton shell (which eats adults) and the red decorator crab (which eats juveniles).

What We Did And What We Found

Virtually all research on crown-of-thorns starfish has focused on larval or adult stages, with little to no attention to juveniles, which are difficult to study.

The juveniles start their life on the reef as algae eaters. Our previous research has shown they don’t have to grow up fast. They can remain herbivores for many years when there’s not enough coral to eat and feast on the algae growing on the skeletons of coral killed by heatwaves.

These Peter Pan-like juveniles can build up hidden in the reef over many years. But how do they cope with heat?

Our experiments revealed young starfish can survive tremendous heatwaves, well above the temperatures needed to bleach or kill coral. Coral can bleach or die when water gets 1–3°C warmer, depending on how long the heat lasts. But the starfish had much greater tolerance – almost three times the heat needed to bleach coral.

All of them survived in coral bleaching conditions – four consecutive weeks of temperatures 1°C above the average maximum temperatures for the sea surface in summer, as well as eight consecutive weeks (enough for mass death of corals) and even 12 weeks – extreme conditions well past what coral can survive.

Over the course of the experiment, the juveniles could handle waters up to 34–36°C.

More Bad News For Coral Reefs

This is not good news for our reefs. Warming waters may actually make life easier for a major predator of coral.

Even if the coral-eating adults decline as their coral prey dies back, their young can wait patiently for the right moment to develop into predators able to devour corals just as they begin to recover.

This discovery may help explain why adult crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks can occur so suddenly.

For years, we’ve suspected the acceleration of outbreaks was linked to predator removal or a build-up of nutrients in the water.

Now we have evidence that coral bleaching and death could actually aid the juvenile crown-of-thorns starfish – and that the heat tolerance of juveniles could add even more pressure to struggling reefs.

Ultimately, the only real solution is to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions.![]()

Matt Clements, PhD Student, University of Sydney and Maria Byrne, Professor of Developmental & Marine Biology, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

AER Alleges Breaches Of National Gas Rules By Santos Direct

Wholesale Energy Prices And Demand Fall In July To September Period

The smarter the magpie, the better they can handle our noisy cities

Cities are hard for wildlife. Many animal species avoid the cars, buildings, smog and fragmented habitats of urban environments. Then there’s the noise pollution, a serious issue for humans and animals alike, according to the World Health Organization.

Human-made (anthropogenic) noise can be very bad for animals. Busy cities can make it harder for animals to reproduce, communicate and behave naturally.

But magpies have generally found our cities to their liking. There is enough food about – and they can usually out-compete other urban bird species.

Even within magpie populations, there are differences in how individuals cope with noise. Our new research has found the magpies that perform better on an associative learning task are better able to maintain their normal anti-predator behaviours in noise. That is, the smarter the magpie, the better they are likely to do in our cities.

What Does Noise Do To A Magpie?

While magpies are often thought of as similar to crows, they’re not corvids at all and not related to Eurasian magpies. Their closest relatives are actually butcherbirds.

To date, most research on the damage done by human-made noise has examined what it means for a species or population. There’s been little work done on how individuals respond differently to noise. What we do know suggests factors such as the sex, age, body condition and prior experience with noise can change how animals cope with noise.

But what about cognition? Animals from the same species can have very different cognitive abilities – the ways an animal perceive, store and respond to information from their environment.

So would smarter animals be more able to change their behaviour to survive better in the urban jungle?

To find out, we observed all behaviours shown in timed 20-minute periods by 75 wild magpies in Perth (to a total of 333 observation periods). We also played magpie alarm calls with and without the noise of planes in the background to 24 magpies to see how plane noise affected their anti-predator response.

These wild magpies live in Perth, Western Australia and have been studied consistently since 2013. Most birds have coloured rings or bands on their legs so we can easily identify them.

Individual identification meant we could test the intelligence of 52 of these magpies to see whether performing better on associative-learning tests would change how birds respond to and cope with anthropogenic noise.

The first thing we found was, yes, magpies find our noise difficult to handle. Our observations revealed loud man-made noises such as traffic, airplanes, or leafblowers forced magpies to spend more time vigilant and alert to threats, to sing less, and to forage less efficiently.

That’s likely because these magpies saw anthropogenic noise as dangerous or threatening stimuli, or as a distraction. That forces them to spend more time alert, with less time for other important behaviours.

But there are other potential causes too. Noise from a bustling restaurant strip may drown out small sounds magpies use as cues, such as the rustle of beetles burrowing under leaf litter.

We also found human-made noise made it harder for our birds to respond to a magpie alarm call, used to warn others of predators. When we played an alarm call in isolation, about 37% of birds sought cover. When we added the noise of a plane flying overhead to the alarm, only 8% of birds fled. This suggests birds couldn’t properly hear and respond to this cue of danger.

Our magpies also spent much more time on alert after an alarm call played alone compared to an alarm call played with human-made noise. This suggests their normal anti-predator response doesn’t work as well against a backdrop of our noise.

Why Would Intelligence Help Magpies Deal With Noise?

Researchers in the United Kingdom working on animal cognition suggest better cognition on a species level may help animals cope with new environments or environmental stress. Other researchers argue cognition is what makes it possible to adapt to and succeed in urban environments.

To test this, we gave magpies a learning task to measure their intelligence and cognition. Could they associate a colour cue with a food reward? How long did it take them to learn that, say, dark blue meant a snack?

This test is a measurement of how quickly they learn. It’s thought to be involved in how successful an animal is in foraging, social interactions and responding to predators.

We found smarter birds reacted more similarly to a standalone alarm call as they did to one with a noisy plane in the background. By contrast, less intelligent birds responded significantly less to alarm calls with plane noise compared to an alarm call alone.

For a magpie, that could be the difference between life or death. If you’re clever enough to shut out the background noise of the plane so you can better hear a warning, you stand a better chance of surviving, say, a dog rushing you at a park.

Birds with better associative learning may also be better in other aspects of intelligence too. In fact, previous research on this species found birds that performed better in one cognitive task also performed better in other cognitive tasks.

As researchers learn more about animal intelligence, we’ll find out more about how associative learning helps animals adapt – and why these abilities are so strongly conserved in evolution.

Our study reveals intelligence matters for individual animals as they grapple with how to adapt to and cope with human-induced stressors.![]()

Grace Blackburn, PhD Candidate, The University of Western Australia and Amanda Ridley, Associate professor, behavioural ecology, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pittwater Reserves: Histories + Notes + Pictorial Walks

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

A Stroll Around Manly Dam: Spring 2023 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

A Stroll Through Warriewood Wetlands by Joe Mills February 2023

A Walk Around The Cromer Side Of Narrabeen Lake by Joe Mills

America Bay Track Walk - photos by Joe Mills

An Aquatic June: North Narrabeen - Turimetta - Collaroy photos by Joe Mills

Angophora Reserve Angophora Reserve Flowers Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth - History page

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Boathouse In Governor Phillip Park Part Of Our Community For 75 Years: Photos From The Collection Of Russell Walton, Son Of Victor Walton

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers

Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham Beach by Barbara Davies

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong and Palm Beach Views - Winter 2018

Currawong-Mackerel-The Basin A Stroll In Early November 2021 - photos by Selena Griffith

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Duck Holes: McCarrs Creek by Joe Mills

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Iluka Park, Woorak Park, Pittwater Park, Sand Point Reserve, Snapperman Beach Reserve - Palm Beach: Some History

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

Lucinda Park, Palm Beach: Some History + 2022 Pictures

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mona Vale Woolworths Front Entrance Gets Garden Upgrade: A Few Notes On The Site's History

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater Reserves: The Green Ways; Bungan Beach and Bungan Head Reserves: A Headland Garden

Pittwater Reserves, The Green Ways: Clareville Wharf and Taylor's Point Jetty

Pittwater Reserves: The Green Ways; Hordern, Wilshire Parks, McKay Reserve: From Beach to Estuary

Pittwater Reserves - The Green Ways: Mona Vale's Village Greens a Map of the Historic Crown Lands Ethos Realised in The Village, Kitchener and Beeby Parks

Pittwater Reserves: The Green Ways Bilgola Beach - The Cabbage Tree Gardens and Camping Grounds - Includes Bilgola - The Story Of A Politician, A Pilot and An Epicure by Tony Dawson and Anne Spencer

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Resolute Track at West Head by Kevin Murray

Resolute Track Stroll by Joe Mills

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Seagull Pair At Turimetta Beach: Spring Is In The Air!

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

Stony Range Regional Botanical Garden: Some History On How A Reserve Became An Australian Plant Park

The Chiltern Track

The Chiltern Trail On The Verge Of Spring 2023 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Topham Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP, August 2022 by Joe Mills and Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Tranquil Turimetta Beach, April 2022 by Joe Mills

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands - Creeks Deteriorating: How To Report Construction Site Breaches, Weed Infestations + The Long Campaign To Save The Warriewood Wetlands & Ingleside Escarpment March 2023

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Wilshire Park Palm Beach: Some History + Photos From May 2022

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

Sydney Opera House 50th Anniversary Film: Play It Safe

"I like to be on the edge of the possible," Jørn Utzon once said, and his design marked a daring leap in 20th-century architecture.

Celebrating 50 years of brave creativity at Sydney Opera House, our new film pays tribute to those who defy that nervous little voice inside us that tells us to play it safe and keep it simple.

Starring Tim Minchin, Sydney Symphony Orchestra, The Australian Ballet, Sydney Philharmonia Choirs, Ziggy Ramo, Zahra Newman - Sydney Theatre Company, John Bell - Bell Shakespeare, Australian Chamber Orchestra, Elma Kris - Bangarra Dance Theatre, Kira Puru, Cathy-Di Zhang - Opera Australia, William Barton, Courtney Act, Jimmy Barnes, Sydney Dance Company Pre Professional Year Students and Associate Artists, Lucy Guerin Inc dancers, and DirtyFeet dancers.

Music and lyrics: Tim Minchin

Director: Kim Gehrig

Executive Music Producer/Arranger: Elliott Wheeler

Cinematographer: Stefan Duscio

Creative Agency: The Monkeys, part of Accenture Song

A Revolver X Somesuch Production

Archival footage and photography courtesy of National Film and Sound Archive, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, British Broadcasting Corporation, Nine Entertainment Co., 10X Media Group, State Library of NSW and Utzon Family.

Presented by Sydney Opera House in partnership with Australia.com.

NSW Government To Host Vaping Roundtable

- Hear evidence on how vaping is affecting young people and schools

- Discuss effective school-based vaping interventions

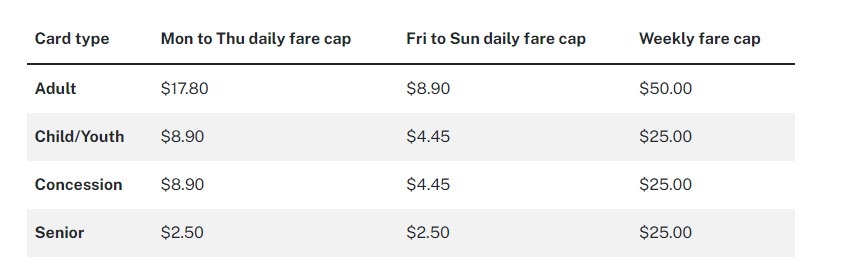

TGIF! Passengers Tap Into Cheaper Public Transport On Fridays

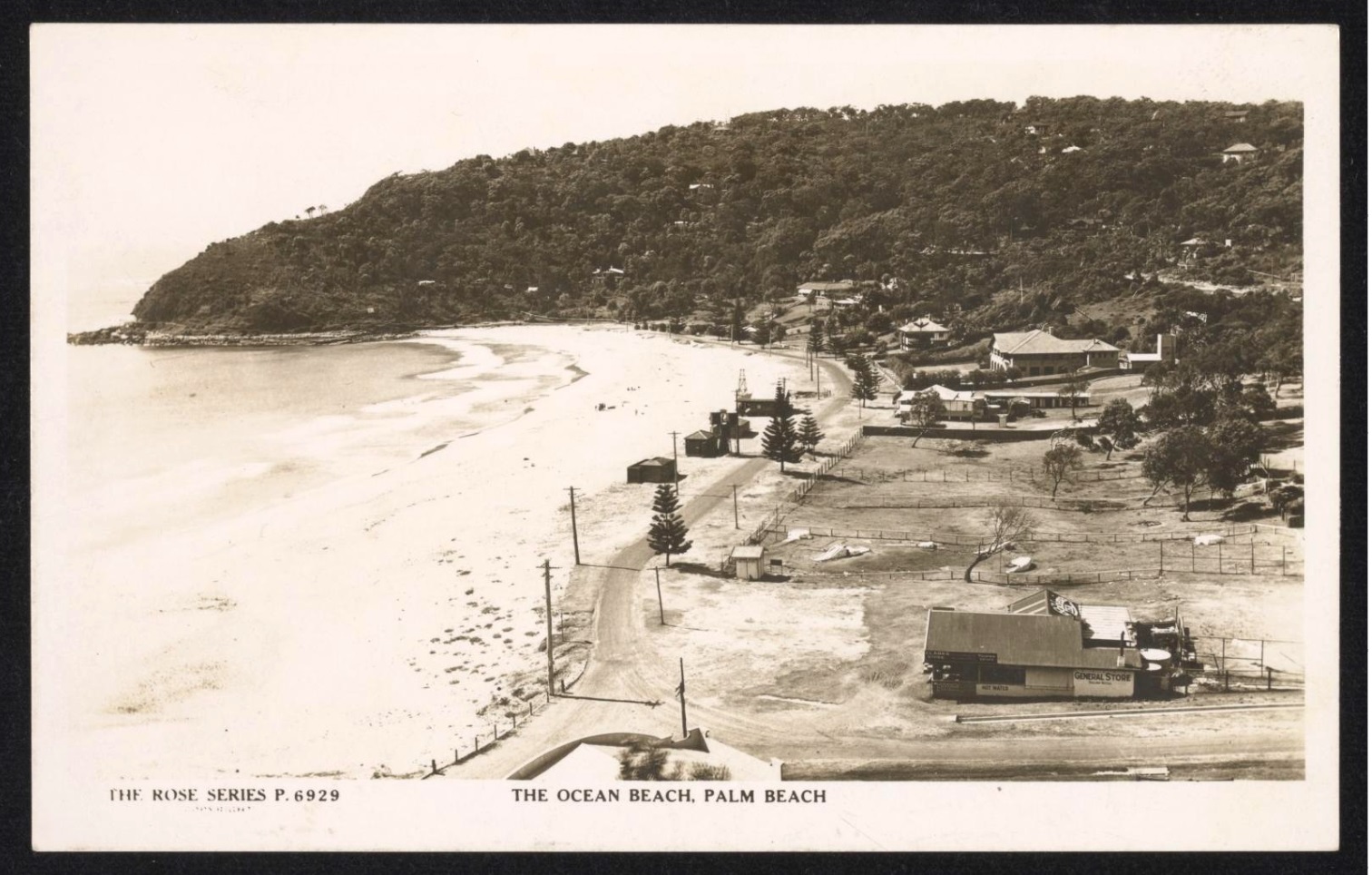

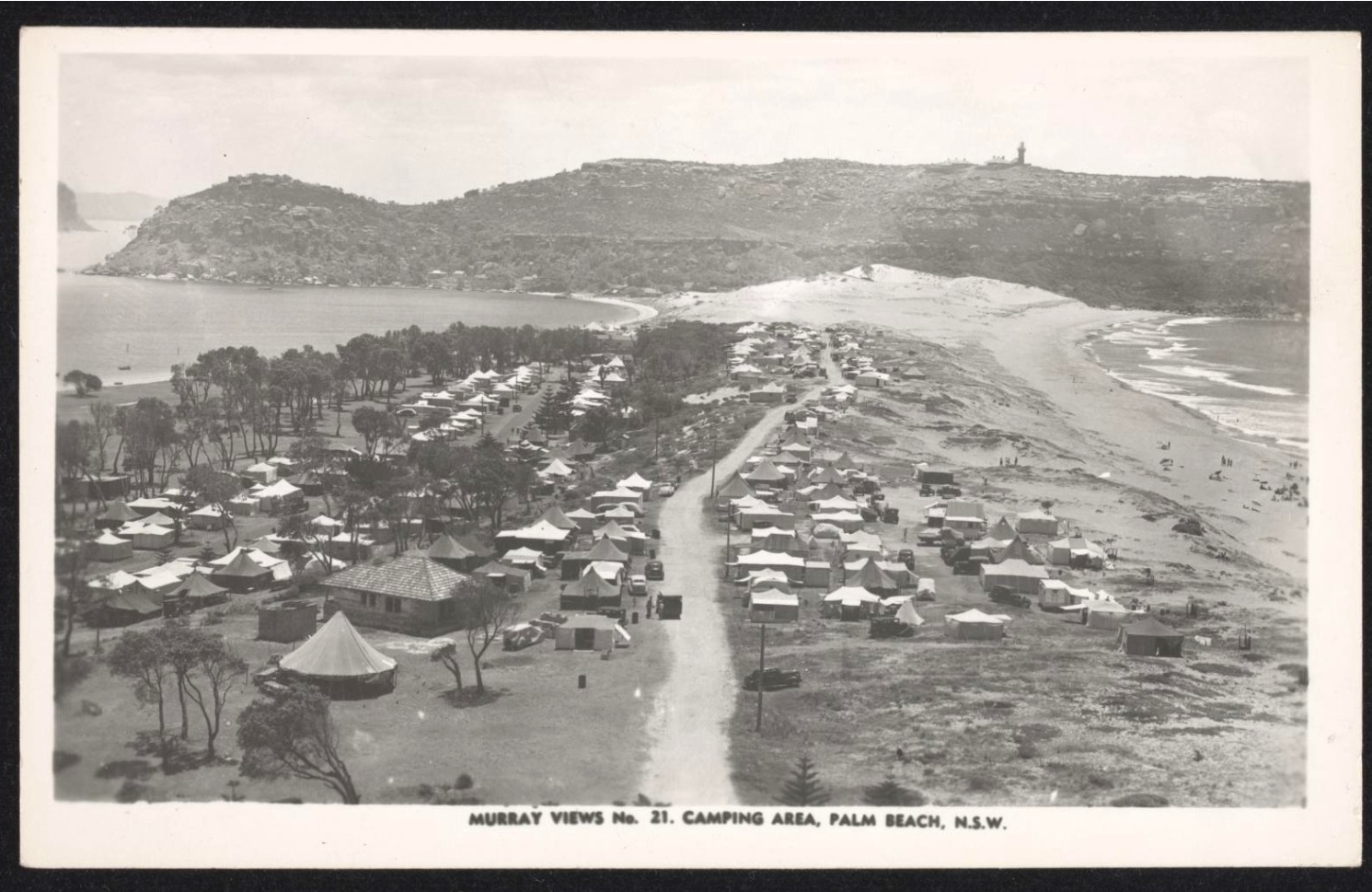

Postcards From The Past: Palm Beach

Exhibition Spotlights Film Behind And Beyond The Front Line

A new touring exhibition from the Australian War Memorial, Action! Film and War, opened in Sydney at the State Library of New South Wales on Friday 6 October.

A new touring exhibition from the Australian War Memorial, Action! Film and War, opened in Sydney at the State Library of New South Wales on Friday 6 October.New Research By ReachOut Highlights Links Between Study Stress And Poor Sleep In The Lead Up To Year 12 Exams

- Lifeline – 13 11 14

- Kids Helpline – 1800 55 1800

- 13YARN – 13 92 76 to speak with an Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander crisis supporter

- If you are in immediate danger dial 000

Links To ReachOut Support Content

8 Student-Backed Study Tips To Help You Tackle The HSC

By University of Sydney: Last updated 6 July 2023

Our students have been through their fair share of exams and learned a lot of great study tactics along the way. Here they share their top study tips to survive and thrive during exam time.

1. Start your day right

Take care of your wellbeing first thing in the morning so you can dive into your day with a clear mind.

“If you win the morning, you can win the day,” says Juris Doctor student Vee Koloamatangi-Lamipeti.

An active start is a great way to set yourself up for a productive day. Begin your morning with exercise or a gentle walk, squeeze in 10 minutes of meditation and enjoy a healthy breakfast before you settle into study.

2. Schedule your study

“Setting up a schedule will help you organise your time so much better,” says Master of Teaching student Wesley Lai.

Setting a goal or a theme for each study block will help you to stay focused, while devoting time across a variety of subjects will ensure you've covered off as much as possible. Remember to keep your schedule realistic and avoid over-committing your time.

Adds Wesley, “Make sure to schedule in some free time for yourself as well!”

3. Keep it consistent

“Make studying a habit,” recommends Alvin Chung, who is currently undertaking a Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Laws.

With enough time and commitment, sitting down to study will start to feel like second nature rather than a chore.

“Do it every day and you’ll be less likely to procrastinate because it’s part of your life’s daily motions,” says Alvin.

4. Maintain motivation

Revising an entire year of learning can seem like an insurmountable task, which is why it’s so important to break down your priorities and set easy-to-achieve goals.

“I like to make a realistic to-do list where I break down big tasks into smaller chunks,” says Bachelor of Arts and Advanced Studies student Dannii Hudec.

“It’s also really important to reward yourself after you complete each task to keep yourself motivated.”

Treat yourself after each study block with something to look forward to, such as a cup of tea, a walk in the park with a friend or an episode of your latest Netflix obsession.

5. Minimise distractions

With so many distractions at our fingertips, it can be hard to focus on the task at hand. If you find yourself easily distracted, an “out of sight, out of mind” approach might do the trick.

“What helps me is to block social media on my laptop. I put my phone outside of my room when I study, or I give it to my sister or a friend to hide,” says Bachelor of Commerce and Bachelor of Laws student Caitlin Douglas.

While parting ways with your phone for a few hours may seem horrifying, it can be an incredibly effective way to stay on task.

“It really helps me to smash out the work and get my tasks done,” affirms Caitlin.

6. Beware of burnout

Think of the HSC period as a marathon rather than a sprint. It might be tempting to cram every single day but pacing out your study time will help to preserve your endurance.

“Don’t do the work for tomorrow if you finish today’s work early,” suggests Daniel Kim, who is currently undertaking a Bachelor of Commerce and Advanced Studies.

“Enjoy the rest of your day and save the energy for tomorrow,” he recommends.

Savouring your downtime will help you to avoid burning out before hitting the finish line.

7. Get a good night's sleep

Sleep is one of your greatest allies during exam season.

“I’ve found that a good night’s sleep always helps with concentration and memory consolidation,” says Bachelor of Science (Medical Science) student Yasodara Puhule-Gamayalage.

We all know we need to be getting around 8 hours of sleep a night to perform at our best, but did you know the quality of sleep also matters? You can help improve the quality of your sleep with some simple tweaks to your bedtime routine.

“Avoid caffeine in the 6 hours leading up to sleep, turn off screens an hour before going to bed, and go to bed at the same time every night,” suggests Yasodara.

8. Be kind to yourself

With exam dates looming and stress levels rising, chances are high that you might have a bad day (or a few!) during the HSC period.

According to Bachelor of Arts and Advanced Studies student Amy Cooper, the best way to handle those bad days is to show yourself some kindness.

“I know that if I’m in a bad state of mind or having a bad day, I’m not going to be able to produce work that I’m proud of,” she says.

For Amy, the remedy for a bad day is to take some time to rest and reset.

“It’s much more productive in the long run for me to go away, do some things I love, and come back with a fresh mind.”

Immerse yourself in a mentally nourishing activity such as going for a bushwalk, cooking your favourite meal, or getting stuck into a craft activity.

If you feel completely overwhelmed, know you're not alone. Reach out to a friend, family member or teacher for a chat when you need support.

There are also HSC Help resources available at: education.nsw.gov.au/student-wellbeing/stay-healthy-hsc

Wednesday 11 October, 2023: HSC written exams start. Friday November 3, 2023: HSC exams finish.

School Leavers Support

- Download or explore the SLIK here to help guide Your Career.

- School Leavers Information Kit (PDF 5.2MB).

- School Leavers Information Kit (DOCX 0.9MB).

- The SLIK has also been translated into additional languages.

- Download our information booklets if you are rural, regional and remote, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, or living with disability.

- Support for Regional, Rural and Remote School Leavers (PDF 2MB).

- Support for Regional, Rural and Remote School Leavers (DOCX 0.9MB).

- Support for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander School Leavers (PDF 2MB).

- Support for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander School Leavers (DOCX 1.1MB).

- Support for School Leavers with Disability (PDF 2MB).

- Support for School Leavers with Disability (DOCX 0.9MB).

- Download the Parents and Guardian’s Guide for School Leavers, which summarises the resources and information available to help you explore all the education, training, and work options available to your young person.

School Leavers Information Service

- navigate the School Leavers Information Kit (SLIK),

- access and use the Your Career website and tools; and

- find relevant support services if needed.

Word Of The Week: Volunteer

Noun

1. a person who freely offers to take part in an enterprise or undertake a task. 2. a person who works for an organization without being paid. 3. Volunteering is time willingly given for the common good and without financial gain.

Verb

1. freely offer to do something. 2. work for an organization without being paid.

From the Latin word voluntarius, meaning willing or of one's own choice. Originally of feelings, later also of actions. This Latin verb originated from the Latin noun voluntas, meaning will or desire - late 16th century (as a noun, with military reference): from French volontaire ‘voluntary’. The change in the ending was due to association with -eer. The first English language use of the word, “Volunteer,” was in a poem titled, “Of Arthour and of Merlin,” which originated around 1330.

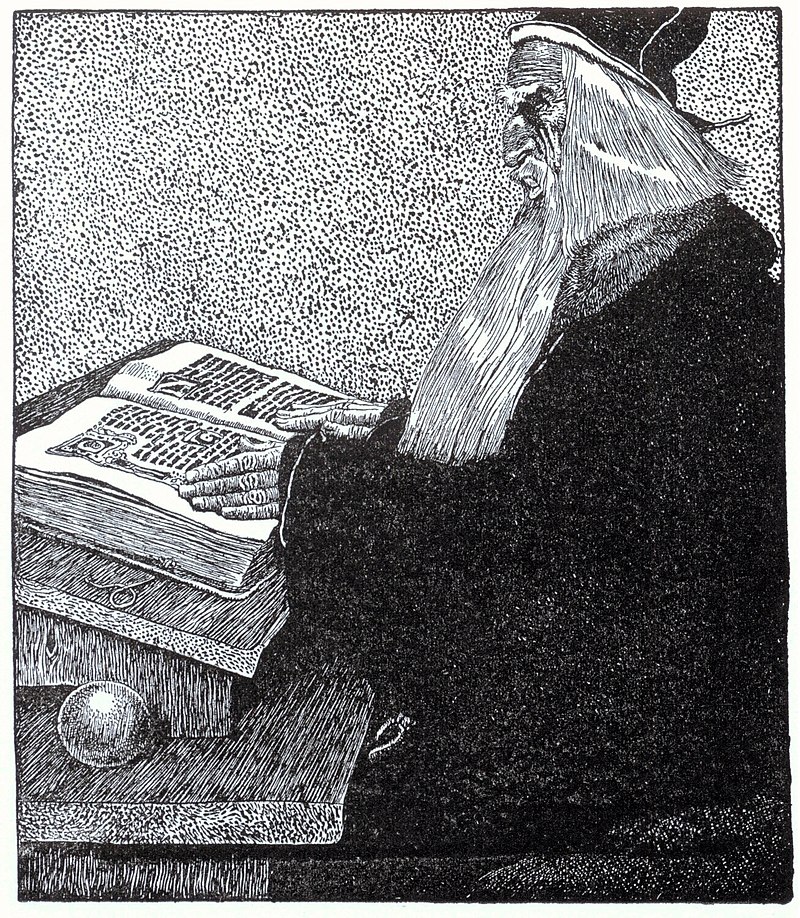

Of Arthour and of Merlin, also known as just Arthur and Merlin, is an anonymous Middle English verse romance giving an account of the reigns of Vortigern and Uther Pendragon and the early years of King Arthur's reign, in which the magician Merlin plays a large part. It can claim to be the earliest English Arthurian romance. It exists in two recensions: the first, of nearly 10,000 lines, dates from the second half of the 13th century, and the much-abridged second recension, of about 2000 lines, from the 15th century. The first recension breaks off somewhat inconclusively, and many scholars believe this romance was never completed. Arthur and Merlin's main source is the Estoire de Merlin, a French prose romance.

Tapestry showing Arthur as one of the Nine Worthies, wearing a coat of arms often attributed to him, c. 1385 - unknown creator.

King Arthur (Welsh: Brenin Arthur, Cornish: Arthur Gernow, Breton: Roue Arzhur, French: Roi Arthur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain. In Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a leader of the post-Roman Britons in battles against Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain in the late 5th and early 6th centuries. He first appears in two early medieval historical sources, the Annales Cambriae and the Historia Brittonum, but these date to 300 years after he is supposed to have lived, and most historians who study the period do not consider him a historical figure. His name also occurs in early Welsh poetic sources such as Y Gododdin. The character developed through Welsh mythology, appearing either as a great warrior defending Britain from human and supernatural enemies or as a magical figure of folklore, sometimes associated with the Welsh otherworld Annwn.

Merlin (Welsh: Myrddin, Cornish: Marzhin, Breton: Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a magician, with several other main roles. The familiar depiction of Merlin, based on an amalgamation of historic and legendary figures, was introduced by the 12th-century British pseudo-historical author Geoffrey of Monmouth and then built on by the French poet Robert de Boron and their prose successors in the 13th century.

The name Merlin is derived from the Brythonic term Myrddin, a bard who was one of Merlin's chief sources. Brythonic was a Celtic language spoken in Britain and Brittany, North France.

Geoffrey seems to have combined earlier tales of Myrddin and Ambrosius, two legendary Briton prophets with no connection to Arthur, to form the composite figure that he called Merlinus Ambrosius. His rendering of the character became immediately popular, especially in Wales. Later chronicle and romance writers in France and elsewhere expanded the account to produce a fuller more multifaceted image, creating one of the most important figures in the imagination and literature of the Middle Ages.

Merlin's traditional biography casts him as an often-mad cambion, born of a mortal woman and an incubus, from whom he inherits his supernatural powers and abilities.[6] His most notable abilities commonly include prophecy and shapeshifting. Merlin matures to an ascendant sagehood and engineers the birth of Arthur through magic and intrigue.[7] Later stories have Merlin as an advisor and mentor to the young king until his disappearance from the tale, leaving behind a series of prophecies foretelling the events yet to come. A popular version from the French prose cycles tells of Merlin being bewitched and forever sealed up or killed by his student, the Lady of the Lake after falling in love with her. Other texts variously describe his retirement or death.

Howard Pyle illustration from the 1903 edition of The Story of King Arthur and His Knights

Volunteerism

Of course Volunteerism didn't need a word to mark when people first started helping each other without expecting anything in return. The oldest books we have, and prior to that artefacts, record caring about your fellow humans. That has persisted in the form of institutions such as hospitals, through churches' tending the sick, to more current forms of volunteering which sees people commit their time and knowledge in any area that they have a passion for; P and C members at schools, surf lifesaving, wildlife, pets that no longer have a home, sailing, cooking meals for people, delivering meals to people, restoring the environment where you actually get to see your contribution grow - literally, reading to others, connecting with older generations - in fact, whatever your interest, how ever much time you have to give, there's a way for you to learn new skills, expand your knowledge base, connect with like-minded others and build community ion your area of interests at a local, state and global stage nowadays.

This opportunity, for those who want to acquire some skills in a larger scale music event, is currently on offer - great for the c.v. and great for those who want to find out a little more about what goes into putting a music festival together.

The Northern Beaches Music Festival 2023: Volunteers needed

The Northern Beaches Music Festival 2023, like a magical musical phoenix rising from the ashes of Covid closure, is once again raising our live music banner high.

On November the 4th and 5th we will be presenting 50 acts on five stages over the weekend. The festival will once again be located at the Tramshed Community Arts Centre and The Berry Reserve by the beautiful Narrabeen Lake. It includes fabulous, multi genre world music on three ticketed stages and one free stage (free to the general public), set amidst our festival village of world food and merchandise stalls.

Our festival is a not-for-profit event produced by the Northern Beaches Music Alliance composed of:

- The Shack

- Humph Hall

- The Manly Fig

- Fairlight Folk

- Songs on Stage

- Acoustic Picnic

With a definite focus on the Northern Beaches, our common goals are to:

- To produce and present musicians and other performing artists including up and coming young artists.

- To provide, maintain and help create venues at which artists can be presented.

- To invite, involve and include our diverse community including the disabled and indigenous, especially with regard to music, performing arts, food, dance, costume and culture.

We are keen to hear from all potential volunteers to help us with the presentation and production of our festival. We need people to:

- work on the gate

- help with administration

- help on stage (including compering)

- help with waste management

- help with musical instrument storage and retrieval as well as a whole range of other more skilled activities!

A “four hour shift “ gets you a day’s free entry! Two “four hour shifts” gets you a free weekend pass. If you’ve got the skills and would like to be involved please contact us!!!

Paul Robertson

Executive Producer

You can contact them at via the numbers listed in the poster below - this is a 'give-get given' opportunity:

Make new friends and become a role model: why you should consider volunteering if you’re in your 20s or 30s

If you’re aged between 25 and 34, you’re part of the age group least likely to take part in volunteering.

Only 19% of 25-34 year olds in England volunteered at least once in 2021-22. By comparison, 29% of 16-24 year olds volunteered in the same period, and the average for all age groups was 27%.

There are all kinds of good reasons why people in their twenties and thirties don’t volunteer. If you’re in this group, you’re likely to be busy establishing your career and relationships, as well as perhaps having and looking after children. It’s more than likely that you’re just really busy.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our twenties and thirties. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

How community gardening could ease your climate concerns

Three ways to get your nature fix without a garden

How often do you think about the Roman empire? TikTok trend exposed the way we gender history

You may also face obstacles to volunteering if you have a disability, come from a marginalised community, or struggle financially.

But volunteering can be extremely beneficial for volunteers, recipients, and society. By not volunteering, 25-34 year olds are largely missing out on these benefits, while organisations that need volunteers are missing out on their skills and abilities. Here are five reasons that might lead you to consider helping out at your local library, food bank or youth club.

Why To Do It

Wellbeing: Volunteering can be good for both your physical and mental health. There is a host of psychological and other research in support of the immediate and longer-lasting wellbeing benefits of volunteering, such as improved confidence and life satisfaction.

Much of the mental health benefit from volunteering comes from engaging with other people – often people that you wouldn’t ordinarily meet. And for your physical health, volunteering can provide opportunities for doing different types of physical activity, such as working on a community garden, coaching a youth sports team, or even moving stock in a charity shop.

Friendship: Making friends as an adult can be tricky – especially now many jobs are hybrid or fully remote, meaning you can’t socialise easily with colleagues. Volunteering can provide you with the opportunity to meet new people and build social connections.

Even if friendships only last for the duration of the volunteer activity, this is still beneficial. This can be particularly significant for people who would otherwise be at risk of being isolated. Meeting new people can also help open up further opportunities beyond volunteering. You can become part of new social networks where information and other resources get shared, such as new job opportunities.

Employability: Although volunteering can lead to paid work, this is not the typical pathway outside of specific work-training programmes. Instead, volunteering is a very good way to fill your CV, show that you’re willing to be proactive and learn skills that can easily be transferred to a workplace. These are highly desirable traits for employers.

Volunteering is also an opportunity to learn new skills or to practise and refine existing ones. These could be role-specific technical skills, such as learning to use a particular piece of equipment. More often, though, you’ll improve your “soft” interpersonal skills. By volunteering in a charity shop or being a “befriender”, for example, you’ll gain experience talking to people from different walks of life.

Be a role model: Children and young people who grow up in households where adults volunteer are themselves much more likely to volunteer as adults. And people that volunteer in their youth are more likely to continue volunteering as adults. If you have children, or are thinking about having them, taking part in volunteering is a way of demonstrating and passing on kindness, compassion and care for your community.

Enjoyment: This is a simple but often overlooked reason. Volunteering can be a fun and enjoyable thing to do.

How To Do It

Despite all these benefits, fitting in regular volunteering might sound daunting – if not completely impossible. However, there are ways you can get the benefits of volunteering while taking part in a flexible way that suits your schedule and circumstances.

You could try episodic volunteering, which requires less regular commitment. This could be helping out with a beach clean over a weekend, or occasionally marshalling a local parkrun.

Your employer might coordinate volunteering opportunities that you can take part in during work hours – such as helping maintain a local park as part of a team building day. Some companies also have “community champions” to make links with their local community.

Or you could look for skills-based volunteering that builds on strengths you already have. If you plan events for your employer, for instance, you could lend this expertise to a charity. Or if you’re an accountant, you could offer pro bono advice to a local community group.

You can even volunteer online. While we traditionally view volunteering as something that takes place face-to-face, volunteers can carry out tasks through digital technology. For example, if you volunteered as a befriender to someone, you could spend time with them online or stay in contact via text. It’s worth thinking about how you could give volunteering a go.![]()

Kris Southby, Researcher in Health Promotion, Leeds Beckett University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

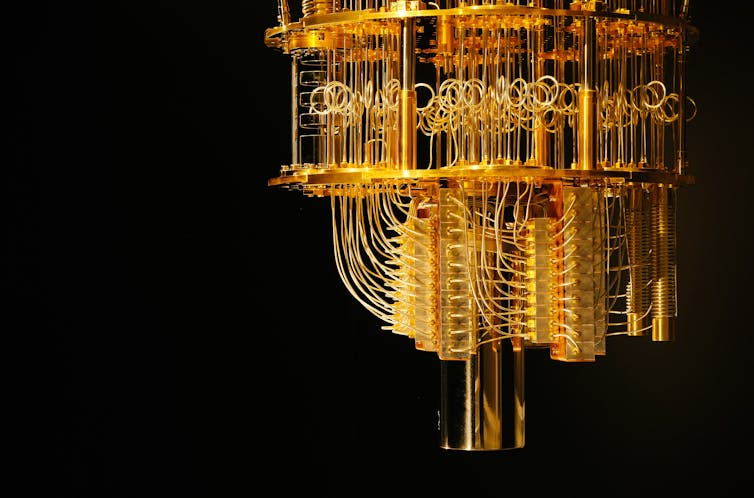

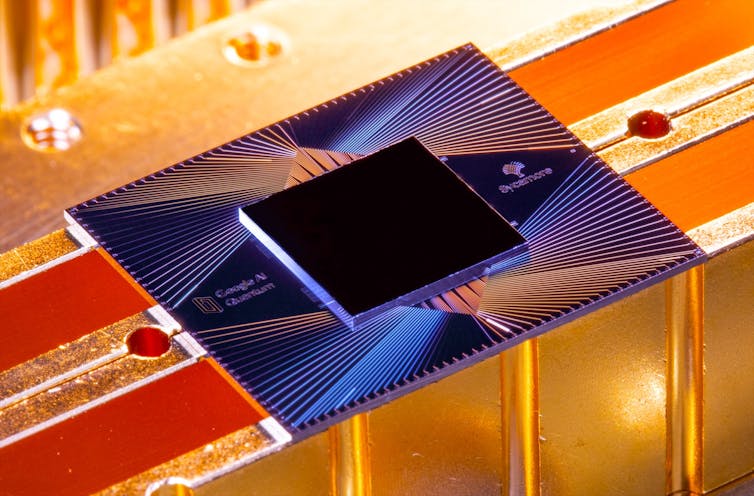

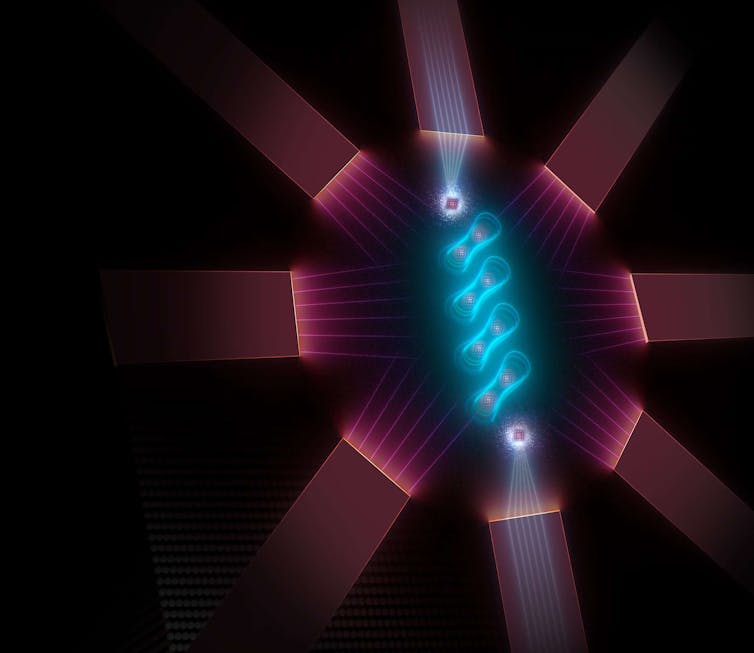

Quantum computers in 2023: how they work, what they do, and where they’re heading

In June, an IBM computing executive claimed quantum computers were entering the “utility” phase, in which high-tech experimental devices become useful. In September, Australia’s Chief Scientist Cathy Foley went so far as to declare “the dawn of the quantum era”.

This week, Australian physicist Michelle Simmons won the nation’s top science award for her work on developing silicon-based quantum computers.

Obviously, quantum computers are having a moment. But – to step back a little – what exactly are they?

What Is A Quantum Computer?

One way to think about computers is in terms of the kinds of numbers they work with.

The digital computers we use every day rely on whole numbers (or integers), representing information as strings of zeroes and ones which they rearrange according to complicated rules. There are also analogue computers, which represent information as continuously varying numbers (or real numbers), manipulated via electrical circuits or spinning rotors or moving fluids.

In the 16th century, the Italian mathematician Girolamo Cardano invented another kind of number called complex numbers to solve seemingly impossible tasks such as finding the square root of a negative number. In the 20th century, with the advent of quantum physics, it turned out complex numbers also naturally describe the fine details of light and matter.

In the 1990s, physics and computer science collided when it was discovered that some problems could be solved much faster with algorithms that work directly with complex numbers as encoded in quantum physics.

The next logical step was to build devices that work with light and matter to do those calculations for us automatically. This was the birth of quantum computing.

Why Does Quantum Computing Matter?

We usually think of the things our computers do in terms that mean something to us — balance my spreadsheet, transmit my live video, find my ride to the airport. However, all of these are ultimately computational problems, phrased in mathematical language.

As quantum computing is still a nascent field, most of the problems we know quantum computers will solve are phrased in abstract mathematics. Some of these will have “real world” applications we can’t yet foresee, but others will find a more immediate impact.

One early application will be cryptography. Quantum computers will be able to crack today’s internet encryption algorithms, so we will need quantum-resistant cryptographic technology. Provably secure cryptography and a fully quantum internet would use quantum computing technology.

In materials science, quantum computers will be able to simulate molecular structures at the atomic scale, making it faster and easier to discover new and interesting materials. This may have significant applications in batteries, pharmaceuticals, fertilisers and other chemistry-based domains.

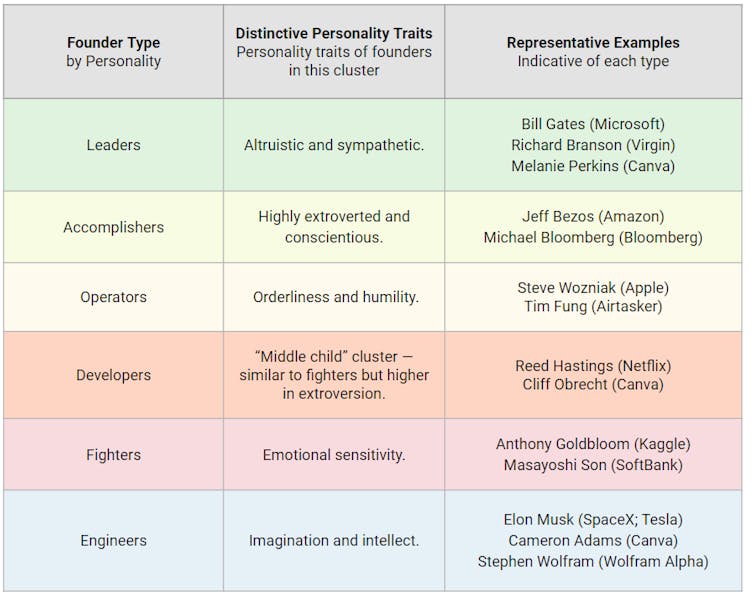

Quantum computers will also speed up many difficult optimisation problems, where we want to find the “best” way to do something. This will allow us to tackle larger-scale problems in areas such as logistics, finance, and weather forecasting.