inbox and environment news: Issue 603

October 29 - November 4, 2023: Issue 603

Fledgling Magpie Being Fed

The Largest Spotted Gum In The World: Old Blotchy

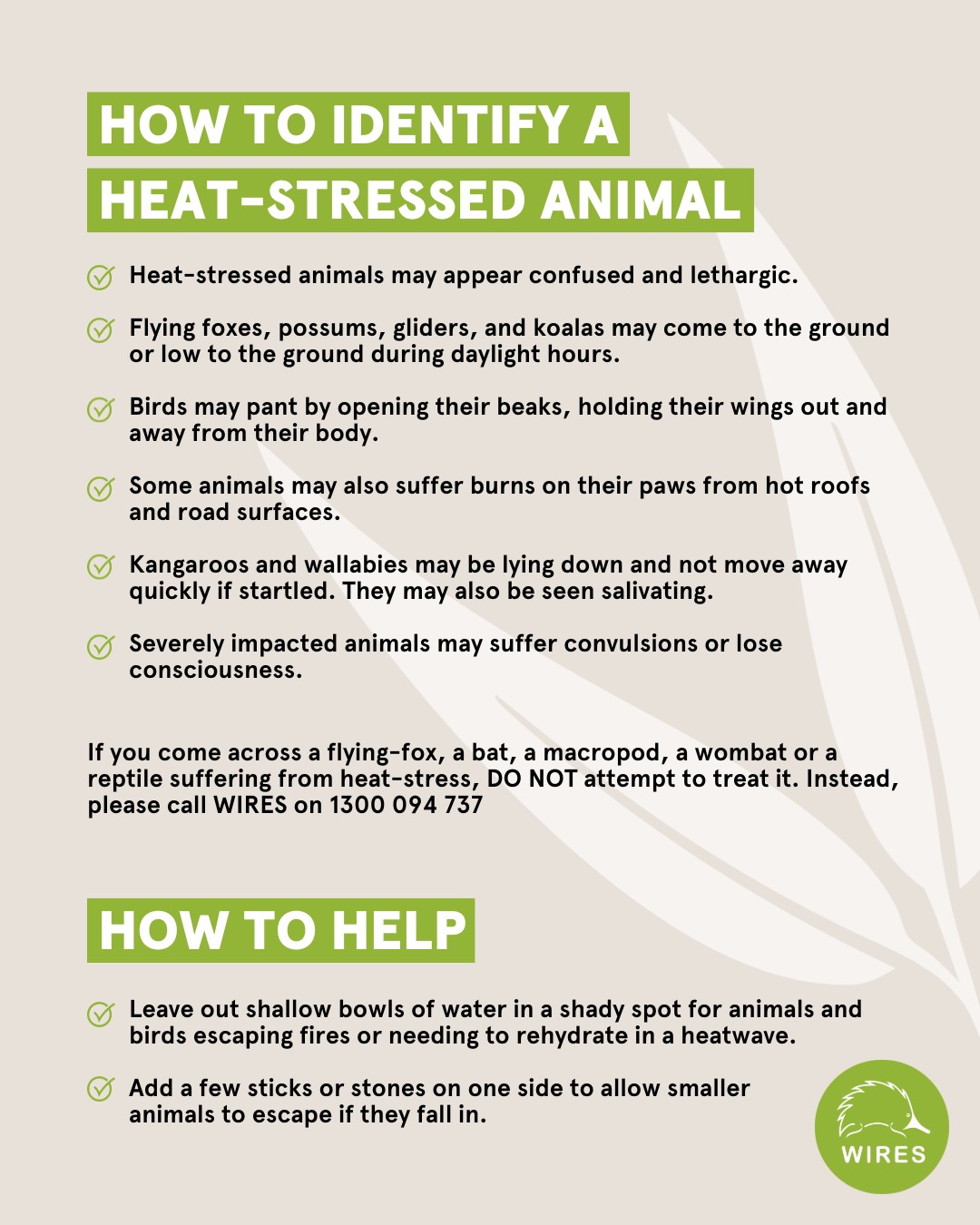

Please Look Out For Wildlife During This Spring Heat

AER Releases Social Licence For Electricity Transmission Directions Paper

- What expectations should be held of transmission businesses in undertaking community engagement

- What outcomes need to be achieved from engagement

- When and how social licence issues can be factored into regulatory tests for the approval of and recovery of cost for new transmission development

- What evidence is needed to justify transmission network expansion and associated expenditure.

- clearly identify the information that is the subject of the confidentiality claim

- provide a non-confidential version of the submission in a form suitable for publication.

Bushwalk Fundraiser

- Friday 10 November

- Friday 8 December

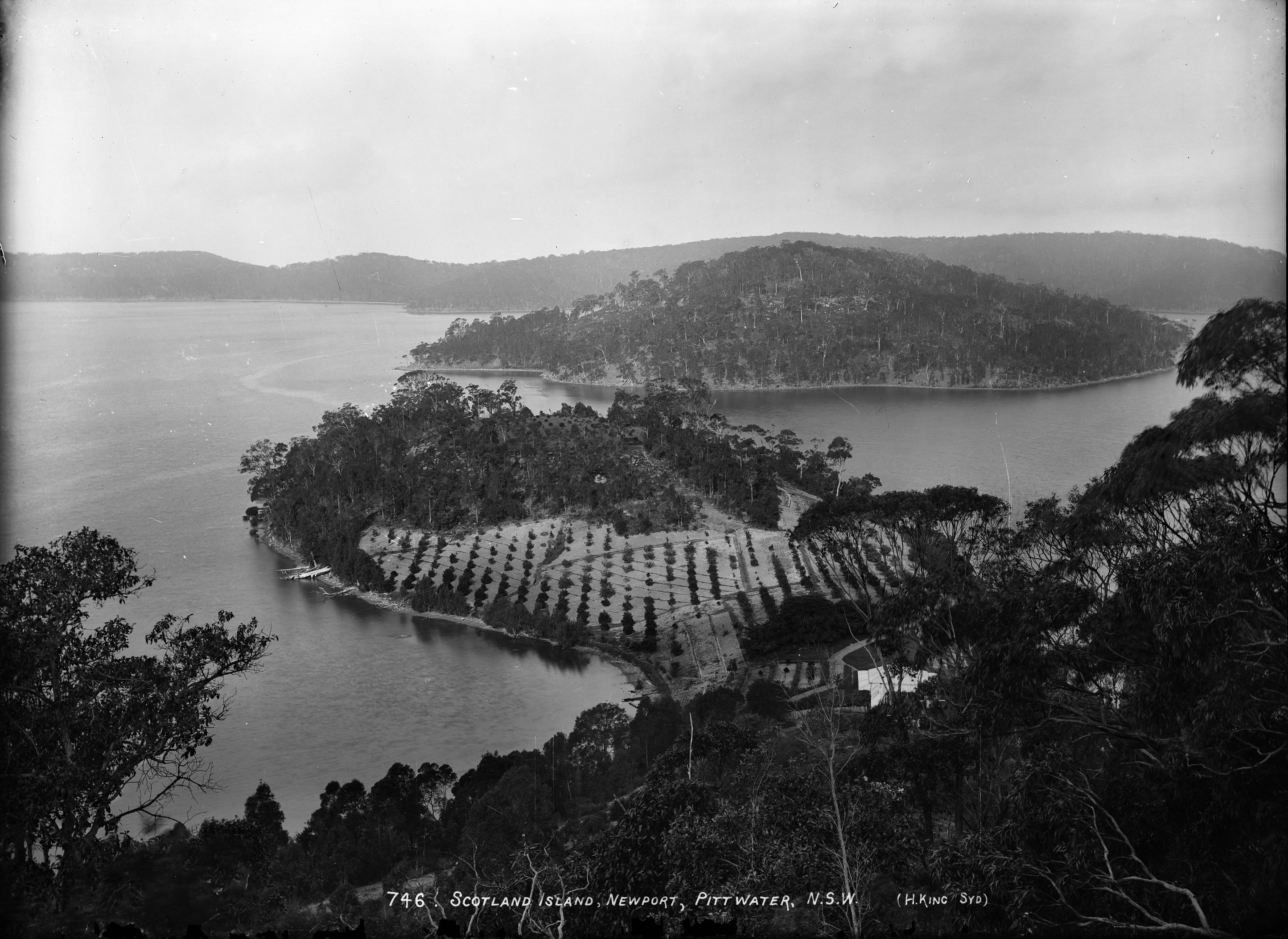

'Scotland Island, Newport, Pittwater, N.S.W.', photo by Henry King, Sydney, Australia, c. 1880-1886. and section from to show cottage on neck of peninsula at western end with no chimneys through roof. From Tyrell Collection, courtesy Powerhouse Museum

𝗞𝗶𝗺𝗯𝗿𝗶𝗸𝗶 𝗥𝗲𝘀𝗼𝘂𝗿𝗰𝗲 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗼𝘃𝗲𝗿𝘆 𝗖𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗿𝗲 𝗶𝗻𝘃𝗶𝘁𝗲𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗺𝘂𝗻𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝘁𝗼 𝗼𝘂𝗿 𝗢𝗽𝗲𝗻 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟮𝟬𝟮𝟯 𝗮𝘁 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗛𝗨𝗕 - 𝗞𝗶𝗺𝗯𝗿𝗶𝗸𝗶.

Highlighting the four resident not-for-profit organisations: Peninsula Seniors Toy Recyclers, Bikes4Life, Boomerang Bags Northern Beaches - Kimbriki, Reverse Garbage and their dedicated volunteers.

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group Begins

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

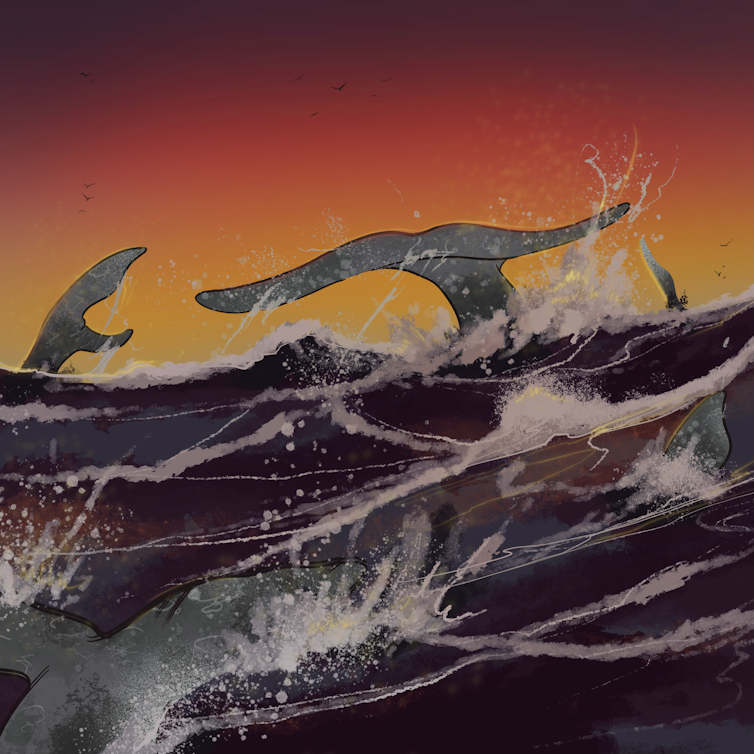

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

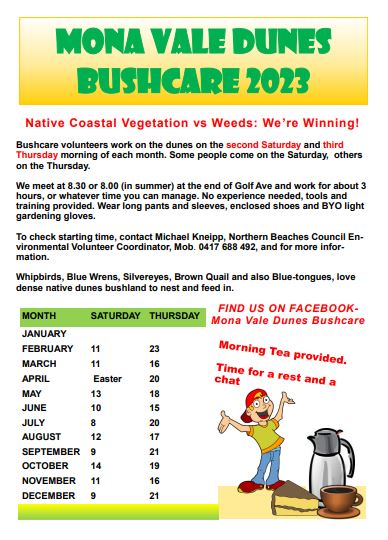

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Biodiversity Can Rebound After Bushfires But Recovery Lags In Severely Burnt Areas: UNSW

October 23, 2023

by Ben Knight, UNSW Media

Extreme fires drove biodiversity declines despite overall resilience after the 2019-2020 Black Summer bushfire season in NSW, a new study suggests.

The Black Summer Bushfires burnt an unprecedented area of over 5 million hectares of eastern Australia, with severe economic, environmental, and human impacts. Now, a study conducted by UNSW Sydney researchers shows plant and animal life has struggled to rebound in locations subjected to the most severe fires.

The study, published in the journal Global Change Biology, analysed differences in species diversity in the aftermath of the 2019-2020 bushfire season in New South Wales. The researchers found that up to 18 months post-fire, biodiversity can recover after fires of low to high severity (when fires burnt the understorey and scorched or partially consumed the canopy) – and did increase a year and a half after the Black Summer Bushfires. However, areas burnt by fires of extreme severity (when fires completely consumed the canopy) experienced reduced levels of biodiversity compared to unburnt and other less severe burnt regions.

Associate Professor Will Cornwell, senior co-author of the study from the School of Biological, Earth & Environmental Sciences, says the findings highlight the fire adaptations of Australian fauna and flora, but also that these adaptations have limits.

“Fire can have both positive and negative effects on biodiversity, and the context is crucial,” A/Prof. Cornwell says. “For example, many Australian species can persist, even with very high severity fires, but some species may struggle when extreme fire severity occurs over large scales.”

Simon Gorta, lead author of the study and a PhD candidate at the UNSW Centre for Ecosystem Science, says the research will help scientists and conservation managers understand which animal and plant species may be impacted by future fires, and identify the areas most needing monitoring and management.

“Our findings illustrate the extent and severity that fires can reach under extensive drought and above-average temperatures, conditions typical of climate change projections,” Mr Gorta says. “As we grapple with the effects of these events on lives and property, we should also be concerned about how our wildlife and ecosystems respond, and how this can be better managed.”

Differing post-fire recovery regions

For the study, the researchers used tens of thousands of wildlife observations of multiple groups of invertebrates, plants, and vertebrates collected by citizen scientists as part of the Environment Recovery Project and the iNaturalist platform to investigate how biodiversity has recovered after the fires and how the type of fire is essential for determining recovery trajectories.

“This initiative was critical, as long-term biodiversity monitoring data covering multiple groups of organisms, such as plants, insects, birds, and more, especially at the scale of these mega-fires, does not exist outside of citizen science data,” Mr Gorta says. “These data allow us to draw conclusions about the overall effects of these events and determine conservation and management approaches for post-fire recovery.”

Overall, the researchers discovered species diversity increased in burnt regions compared to before the fires in both burnt and unburnt parts. But, compared to unburnt regions, species diversity significantly decreased in areas exposed to extreme fire severity.

“The increase in species diversity, or richness, in burnt areas was greater than the increase after fires in unburned areas, which suggests they can recover well if fires are not too severe,” A/Prof. Cornwell says. “But pushing them into this high severity zone has the opposite effect on biodiversity.”

“Many Australian species can persist, even with very high severity fires, but some species may struggle when extreme fire severity occurs over large scales.”

The researchers say they’re not sure whether or when diversity in the extreme severity regions will fully recover.

“We don’t have the data yet to know whether diversity will bounce back – a lot will depend upon whether they burn again with the same intensity in upcoming fire seasons,” A/Prof. Cornwell says. “It implies that in the immediate post-fire aftermath, we need to focus our efforts on supporting recovery in areas that were subject to the highest severity burns.”

In addition to the findings at the biodiversity scale, the study also identified how species with post-fire recovery mechanisms can drive response patterns, particularly for plant species. For example, plants with limited resprouting capacity after severe fires in rainforests are particularly vulnerable to increasingly frequent and intense fires.

“The study highlighted adaptations such as fire-cued flowering, which is a key part of the life cycle of many Australian native plants, potentially increased the detectability and attractiveness of plants in the post-fire environment,” says Dr Mark Ooi, co-author of the study. “This provides both an understanding of the post-fire patterns we see and highlights some of the challenges in surveying biodiversity after these events.”

The researchers plan to conduct further studies monitoring different post-fire impacts, including which species are most at risk. They say the efforts of citizen scientists to capture observations represent not only a critical data resource but also reflect the willingness of the public to participate in science to protect the environment.

“Fire seasons are only going to worsen under the current climate projections,” Mr Gorta says. “We need amateur scientists to help grow the dataset further so we can continue to monitor and manage the environmental impacts of wildfires in a rapidly warming and fire-conducive climate.”

Simon B. Z. Gorta, Corey T. Callaghan, Fabrice Samonte, Mark K. J. Ooi, Thomas Mesaglio, Shawn W. Laffan, Will K. Cornwell. Multi-taxon biodiversity responses to the 2019–2020 Australian megafires. Global Change Biology, Oct. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16955

Sea-Lovers Urged To Help To Save Sea Turtles This Nesting Season

.jpg?timestamp=1697895535957)

.jpg?timestamp=1697895565175)

- walk your local beach early in the morning, as sea turtles generally nest during the night.

- keep your eyes peeled for any tracks in the sand, which are usually 80–100 cm wide and can sometimes be mistaken for tire tracks.

- take your phone with you so you can quickly call NSW TurtleWatch or NPWS if you see any signs of turtles, tracks or a nest.

$16 Million For Crown Reserve Improvements

- Maintaining or increasing public access, amenity and use of a reserve.

- Supporting social cohesion and participation in community life.

- Enabling people with accessibility requirements or living with a disability to be included.

- Delivering a service or infrastructure to enable Aboriginal people to access, care for or protect and manage land.

- Conserving heritage values and/or natural values of a reserve.

- Creating employment or business opportunities.

Funding To Make Apartment Buildings Ready For EVs

Have Your Say On 10-Year Trout Cod Recovery Roadmap

The Trout Cod (Maccullochella macquariensis) or bluenose cod, is a large predatory freshwater fish of the genus Maccullochella and the family Percichthyidae, closely related to the Murray cod. It was originally widespread in the south-east corner of the Murray-Darling river system in Australia, but is now an endangered species.

The Trout Cod (Maccullochella macquariensis) or bluenose cod, is a large predatory freshwater fish of the genus Maccullochella and the family Percichthyidae, closely related to the Murray cod. It was originally widespread in the south-east corner of the Murray-Darling river system in Australia, but is now an endangered species.$6 Million For Tamworth To Investigate Recycling Industrial Water

- Diversifying water sources to reduce demand on the town's water supply.

- Improving long-term water security for the region, including during droughts.

- Unlocking economic growth for agricultural businesses so they can expand operations without putting more pressure on Tamworth’s water network.

- Addressing water salinity issues that impact water quality and the environment.

Digital Safety Upgrades For NSW National Parks Bushwalkers

New Hope For Rare Australian Bird

$1.5 Million For NSW Bushfire And Natural Hazards Research Centre Climate And Weather Research

2 biggest threats to wombats revealed in new data gathered by citizen scientists

Launched in 2015, WomSAT (Wombat Survey and Analysis Tool) is a citizen science project and website that allows “wombat warriors” to report sightings of wombats, their burrows, and even their cube-shaped poops.

The project initially aimed to uncover information on all things wombat from across Australia, particularly threats. Its ultimate aim is to support conservation, informed by an enhanced understanding of wombat biology.

WomSAT also aims to educate the wider community by using the hashtag #WombatWednesday to spread the word. The project has resulted in raising the profile of wombats in the broader community.

People have jumped onboard to support the charismatic species, and thousands of posts have been shared via social media.

To date, citizen scientists across Australia have reported more than 23,000 wombat sightings to WomSAT. These sightings have recently been analysed and the findings published in Australian Mammalogy and Integrative Zoology.

Importantly, the data have given us new insights into where to find two of the biggest threats: Australia’s wombat roadkill hotspots, and the worst areas for sarcoptic mange (a disease related to scabies).

Making Our Roads Safer For Wombats

Wombats are large, mostly grass-eating native Australian marsupials. They play an essential role in maintaining biodiversity as ecological engineers. Through their burrowing, they maintain soil health and create habitat to support other plants and animals.

There are three species of wombats: the critically endangered northern hairy-nosed wombat (Lasiorhinus krefftii), the threatened southern hairy-nosed wombat (L. latifrons), and the bare-nosed or common wombat (Vombatus ursinus).

Like most Australian native animals, wombats are under threat on many different fronts – habitat destruction, changed fire regimes, competition from introduced species, and even direct persecution by humans, as they are deemed pests by some. The bare-nosed wombat is particularly impacted by roadkill and sarcoptic mange.

The new data reported to WomSAT have identified roadkill hotspots and factors affecting wombat vehicle collisions. Several areas were identified as roadkill hotspots, including Old Bega Road and Steeple Flat Road in southern New South Wales. Most wombat roadkill deaths occurred in winter, and sadly most appeared otherwise healthy.

Having better data and identifying these roadkill hotspots will ultimately reduce road risks for people and wombats. We can target these hotspots using mitigation strategies such as reduced speeds, signage and barriers to prevent wombat crossing and avoid collisions.

Mangy Marsupials

WomSAT data have also revealed that wombat populations in closer proximity to urban areas have more wombats with sarcoptic mange. Mange is a disease caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei mite.

In people this mite causes scabies. But in wombats, the disease is fatal if left untreated. The mites cause disease by burrowing into the skin of wombats, causing extreme itchiness and discomfort. Eventually it leads to large open wounds, and the wombat dies from secondary infections.

For sarcoptic mange reports, the season was not statistically significant, but rainfall was. This could potentially be because scabies mites thrive in more humid environments, but more research is needed.

Interestingly, our field research has also indicated that rainfall contributes to higher occurrence of sarcoptic mange in specific populations we have monitored over several years.

Overall, roadkill events and sarcoptic mange are two of the biggest threats to bare-nosed wombats. As we continue to track both over time, it will help us to better understand and mitigate these threats.

You Can Become A Wombat Warrior Too

Recent upgrades to WomSAT will now allow GPS location data embedded in photos taken using smartphones. Importantly, this means users can upload wombat sightings when they come back into phone signal or internet range.

Users can also now upload information where wombats are not found, which provides important information on wombat distribution and abundance.

Another new feature on WomSAT will assist wildlife carers to directly monitor and record treatment of wombats with sarcoptic mange in the field. In the past, treatment regimes have rarely been recorded. This will benefit the wider wildlife care network by highlighting areas where wombats are currently being treated, as well as new areas where wombats require treatment.

In the longer term, the resource will also help to support the development of better treatment regimes by recording treatment methods and tracking wombats (through photographs) to help monitor their recovery.

Regardless of the level of experience with wombats, everyone can get involved and become a wombat warrior. You can do so by reporting sightings of wombats and their burrows to the WomSAT website via a mobile phone or computer.

Ongoing reporting to WomSAT will provide more insights into these amazing marsupials. It can be used to assist with determining wombat distribution and abundance patterns, as well as help manage the threats they face.![]()

Julie Old, Associate Professor, Biology, Zoology, Animal Science, Western Sydney University and Hayley Stannard, Senior lecturer, Charles Sturt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Cleaning up Australia’s 80,000 disused mines is a huge job – but the payoffs can outweigh the costs

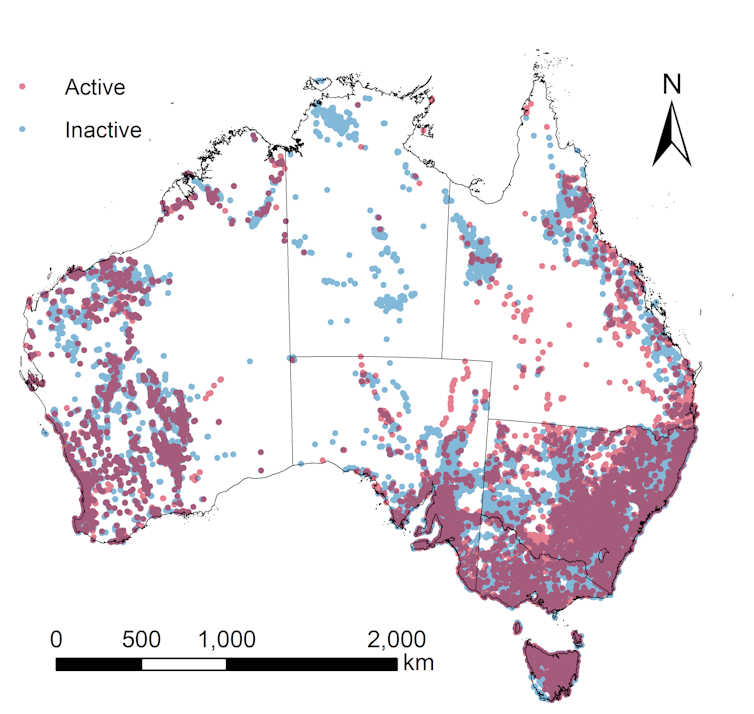

Newly announced closures of Glencore’s copper and zinc mines in Mt Isa will add to a huge number of former mines in Australia. A 2020 study by Monash University’s Resources Trinity Group found more than 80,000 inactive mine sites across the country.

Globally, a 2023 study estimates the mining footprint at around 66,000 square kilometres. Abandoned mines account for much of this area.

It’s estimated the US has about 500,000 abandoned mines and Canada at least 10,000. The UK and China have at least 1,500 and 12,000 old coalmines, respectively.

Abandoned mines can pose extreme environmental, health and safety risks. Unreclaimed coalmines, for example, continue to emit greenhouse gases.

Land is a scarce resource. Restoration enables sustainable and dynamic use of former mining land. It opens up golden opportunities – environmental, social and economic.

Environmental Benefits

Carbon farming

Mine leases generally lock up vast land areas. This land presents a commercially viable, yet neglected, opportunity for carbon farming.

For example, replanting abandoned leases could earn carbon credits under the Australian government’s Carbon Farming Initiative. It can help “hard to abate” industries such as mining move towards net zero emissions.

Sustainable and renewable energy

Abandoned mines can also be used to produce and store renewable energy. Examples range from providing sites for solar farms to Green Gravity’s energy storage technology.

Green Gravity uses a system of weights in a mine shaft to store energy from renewable sources. This energy is used to raise the weights. The energy can later be released when the weights are lowered under the pull of gravity.

Another example is the former Kidston gold mine’s pumped storage hydro project. This system uses two water reservoirs in former open pits. Renewable energy is used to pump water into the higher reservoir. Releasing this water into the lower reservoir generates hydropower energy as needed.

For abandoned deeper mines, tapping into geothermal energy could even make it viable to resume mining.

Water security

Abandoned mines or quarry pits can store large amounts of drinking, harvested and recycled water. This will help increase water security, especially when located near urban areas or industry corridors.

Disaster prevention

Another option is renaturalisation. This depends heavily, though, on location and mine type.

For example, Indonesia has plans to restore forest on former mine sites to help reduce floods. These reforested areas will help retain floodwaters.

Biodiversity restoration

Nature-based approaches to mine rehabilitation include reforestation and phytoremediation, which uses plants to clean up contaminated environments. These approaches tackle mines’ legacy of pollution and add ecological value.

Restored land allows for native species to be reintroduced. It can also provide bridges between patches of habitat to enhance biodiversity. In Victoria, this has been done with a former quarry at Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne.

Social Benefits

Improving urban liveability

Renaturalised mines can be valuable communal and green spaces. Particularly when done in urban areas, it can provide residents with better air quality, microclimates and quality of life as these sites support recreational and cultural activities. All Nations Park is another example of a quarry restoration just seven kilometres from the Melbourne CBD.

Education and tourism opportunities

Restored mining land opens up educational, architectural and tourism opportunities. These range from hotels such as the InterContinental Shanghai Wonderland – most of it is underground – to eco-tourism and education centres, such as the Eden Project in the UK.

Economic Benefits

Critical minerals

Critical minerals are vital for batteries, electric vehicles and electrification needs. These minerals can be extracted from inactive mines and tailings storages.

Mine waste processing could contribute billions of dollars a year to the economy and support regional jobs.

Job creation

Several large regions in Australia, including the Pilbara and Bowen Basins, face similar rehabilitation challenges. But each company is responsible for its own mine closure and rehabilitation. Current mining business models are not well suited for rehabilitation.

However, the scale of the rehabilitation work required in a major mining region would support an entire regional industry. It could provide many local jobs after mines close.

There are synergies between the many uses of restored mine sites. For example, Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne not only restores biodiversity, but has also created an attractive space for people to gather, along with jobs and education opportunities.

So What Are The Obstacles?

A mine’s rehabilitation costs may total hundreds of millions of dollars. These costs are often many times greater than what governments hold in rehabilitation bonds, which operators must provide as financial security before mining begins. Nevertheless, the financial and environmental consequences of inaction dwarf such costs.

Globally, the costs of mine rehabilitation and closure liabilities run into billions of dollars. However, investments in green infrastructure have reached trillions of dollars. Some of these funds could be directed into rehabilitation and clean-up efforts, with the benefits of:

- providing capital to “kick off” and refine the collaborative work needed to deliver multiple benefits – as well as mining companies, this work involves many other organisations and individuals

- creating clear financial accountability for rehabilitation

- generating business opportunities and sites for testing new sustainability practices and developing “gold standards” for restoring and repurposing mine sites.

A co-operative investment approach enables all partners to understand their shared responsibilities before any long-term expenses affect them individually.

Strong governance, initial funding and collaborative development are needed to achieve environmental, social and economic outcomes that add value to mine rehabilitation.

Acknowledgements: David Whittle, Alec Miller, Tim T. Werner and a number of Monash University staff and students over the years who have contributed to the research base.![]()

Mohan Yellishetty, Co-Founder, Critical Minerals Consortium, and Associate Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Monash University and Peter Marcus Bach, Senior Research Scientist, Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences, and Adjunct Research Fellow, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How Australian companies can fudge their numbers to show social and environmental progress

What’s the easiest way to improve a company’s social and environmental performance? The unfortunate answer, from our analysis of Australian public companies, is to change the way you measure it. In particular, by changing what you said last year to make this year’s performance look better.

Reporting on environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance is increasingly important to the fortunes of listed companies – under pressure from investors, regulators and other stakeholders.

In some cases, executive pay is tied to these metrics.

Our study, which examined reports from the top 500 companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) over the past 15 years, suggests progress can be little more than sleight of hand, facilitated by the lack of clarity around how ESG performance is measured and reported.

Our final data set includes those companies that report on both their ESG performance and their executive remuneration practices. This numbered about 215 individual companies.

Of these, roughly one in six made adjustments to past reported ESG performance, particularly around social measures such as gender diversity or workplace safety. The average size of the adjustments was also significant, at 28% of the original value reported.

About 55% of companies tied a proportion of their chief executive’s bonus to ESG metrics. These companies were twice as likely to make one or more adjustments to past reported ESG numbers. In fact, 33.5% of all adjustments were of an ESG measure that was included in the chief executive’s bonus. The average size of these adjustments was also larger, at 36% of the original value.

This occurred across all industries but was most common in two areas: the financial sector and the materials sector, which covers mining and chemical, construction and forest products.

Linking Executive Pay To Improvements

If retrospective changes were the result of previous mistakes or improvements in measurement systems, there should be no bias in the direction of changes to past performance (that is, it could go up or down). But we found a significant bias towards making past performance look worse, thereby making the current year’s look better.

Fuelling this seems to be the practice of tying executive bonuses to a simple improvement, rather than to a stipulated target. For example, executives might be rewarded for increasing the proportion of female or Indigenous employees or cutting injury rates, rather than hitting specific targets for these metrics.

We found about 17% of bonus pay is typically attributed to ESG targets. For the average chief executive in our study, this translates to around $200,000 in extra income. It’s not surprising that retrospective changes making current-year performance seem better were more likely to occur when greater weighting was given to these targets in the chief executive’s contract.

The Case Of Commonwealth Bank

The restatement of ESG measures is illustrated by the case of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, which has been criticised for vague performance targets.

Over the past few years it has tied about 10-15% of the chief executive’s bonus to relatively intangible metrics. In its 2020 report, for example, “people measures” covering “culture, wellbeing, talent and capability” comprised 9% of the chief executive’s bonus.

Thees metrics have persistently changed retrospectively, as shown by employees’ “safety and wellbeing” results.

For example, the bank’s 2017 annual report showed 1.1 injuries per million hours worked (this is a standard measure, known as the “lost time injury frequency rate”).

However, in its 2018 annual report, the bank revised the 2017 figure from 1.1 to 1.6, which meant the 2018 report showed injury rates as having decreased relative to the previous year.

The stated reason for the change was that the updated 2017 figure includes injury claims received after the year-end reporting date, as well as expanding the scope to include New Zealand employees when calculating this metric.

In its 2019 annual report, the 2018 figure was then revised up from 1.1 to 1.4. This meant the report showed no increase in injury rates for 2019.

In its 2020 report, the 2019 figure was revised upward to 1.6. If we compare the final adjusted figures for 2019 and 2018, there was actually an increase in rates between the two years.

This practice is persistent up to the 2023 reporting period, and it’s likely legitimate that some injury claims are indeed filed after the year-end reporting date. However, if this is the case, we might wonder why an incomplete number from a current report is being compared with a complete one from a previous report.

In response to queries from The Conversation, a spokesperson for Commonwealth Bank confirmed this is indeed how these figures are collated, but denied that there is pressure to compile the data in a way that gives the impression of constant improvement.

Of course, safety and wellbeing are important issues, but the discretionary nature of these metrics means retrospective changes can make it look like improvements have occurred. Therefore, we advise users of this information to exercise caution when comparing performance to adjusted numbers, particularly as little information is typically given to explain why the adjustment was made.

For example, Commonwealth Bank’s 2023 annual report features a change to the way full-time equivalents are calculated, but without explaining how or why the previous years’ figures were adjusted.

Manipulating Vs Managing

As per the adage “what gets measured gets managed”, governments and investors have pushed sustainability reporting on the basis it will encourage companies to be socially and environmentally responsible.

This is partly due to a shift away from the view that companies exist purely to maximise shareholders’ wealth, and towards the idea they should be good corporate citizens with minimal negative impact on the environment and society. Some investors prefer to invest only in stocks that meet ESG performance criteria.

This creates incentives to exaggerate claims – made easier by the lack of uniformity in measuring and reporting such results.

Who Sets The Standard?

An international body to set global standards, the International Sustainability Standards Board, was established in 2021. It published its first set of ESG standards in June.

Australia is set to follow these standards, under a proposal by Treasury, with one catch: the regulations will focus only on climate-related disclosures, which will apply to Australian companies from 2024, overseen by the Australian Accounting Standards Board.

While these standards will create greater consistency in ESG disclosures, there will remain significant discretion in how ESG performance is measured – including the ability to change how ESG items are measured from year to year and to adjust previous years’ apparent performance.

Currently, ESG performance isn’t required to be audited, and just 22% of the companies we looked at had their ESG performance audited. Last month, the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board issued a draft sustainability assurance standard that will require auditors to provide assurance of reported ESG figures.

Treasury has also said Australia will follow this standard, and expects auditors to provide reasonable assurance on all climate disclosures by 2027. Hopefully, these audits will also consider the legitimacy of revisions or changes in measurement. But regardless of this improvement in accountability regarding environmental performance, companies’ reporting on social metrics will still be unregulated.

The irony is striking. What was conceived as a mechanism to drive positive environmental and social change may instead act as an incentive to manipulate sustainability performance.![]()

Helen Spiropoulos, Associate Professor, University of Technology Sydney and Rebecca L. Bachmann, Lecturer in Accounting, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pushing water uphill: Snowy 2.0 was a bad idea from the start. Let’s not make the same mistake again

Last night ABC’s Four Corners investigated the problem-plagued Snowy 2.0 pumped hydro power station, focusing on a bogged tunnelling machine, toxic gas and an unexpected volume of sludge.

While these specific problems are new, we have criticised this project since 2019 and outlined six key problems even earlier elsewhere.

How Did We Get Here?

In March 2017, then-Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced the project, lauding it as a game changer for our clean-energy revolution.

In his memoir, Turnbull dubbed Snowy 2.0 “the single most important and enduring decision of the many I made on energy”.

Alas, Snowy 2.0 has not gone well. The warning signs were there from the start. Both the government-appointed Snowy Hydro Board and federal government were warned they had greatly under-costed it, underestimated the construction time and failed to recognise the damage it would do to the Kosciuszko National Park.

In August this year, the government bumped up funding for Snowy 2.0 to A$12 billion – triple the October 2018 figure, when the final decision was made to go ahead, and six times what Turnbull first claimed it would cost in March 2017. That’s before counting the new transmission lines through the controversial HumeLink and VNI West transmission projects. When complete, Snowy 2.0 plus transmission could cost upwards of $20 billion – over ten times the figure Turnbull claimed.

Energy minister Chris Bowen put the Snowy failures and blowouts down to poor execution. Was it still worthwhile? Yes, he said. But Bowen also admits to being swayed by the sunk cost – the government has already spent over $4 billion on it.

Snowy Hydro’s new CEO Dennis Barnes has claimed that while costs have blown out, the public benefits have increased as well.

To date, nothing has been released to substantiate claims of extra benefit despite requests by journalists and by the Senate. All that has been released is a one-page press release and a highly redacted report.

What Are The Lessons Here?

Pumped hydro is essentially a hydroelectricity plant with the ability to pump water back up to the top reservoir. You use cheap power to pump it uphill, and run water back down through turbines to generate power as needed.

The technology isn’t new. It had a previous burst of popularity in developed nations in the 1970s. But since then, there’s been very little pumped hydro built except in China.

Since the 1970s, Australia has had three pumped-hydro generators supplying the National Electricity Market, two in New South Wales and one in Queensland. Data on their generation shows they have only a minor role in energy storage.

None of these are comparable to Snowy 2.0, which would be vastly bigger than any we’ve built before. Snowy 2.0 has by far the longest tunnels – 27 kilometres – of any pumped-hydro station ever built.

Even our smaller pumped-hydro projects are proving harder to complete than expected. The depleted Kidston gold mine in Queensland is being converted to a 250 megawatt pumped-hydro station. The project is much simpler and smaller than Snowy 2.0 and has had extensive policy and financial support by federal and state governments. But it too is running over budget and late, although not remotely close to the same extent as Snowy 2.0.

These projects present hard and expensive engineering problems. They do not deliver economies from learning because each is different from the other.

By contrast, chemical batteries are increasingly standardised. They’re attracting huge investment in research and production. They improve the capacity of existing transmission. They’re made in factories so become cheaper as the industry scales, they have much lower capital outlays per unit of storage, so you get a much quicker payback. And you can resell them easily.

How Did We Make Such An Expensive Mistake?

One simple explanation is that it was a political decision. The original Snowy Hydro scheme is famed as a nation-building project in post-war Australia. Snowy 2.0 was framed in the same way. Then there’s the need to be seen to “do something”, with economic and technical merit a distant third place.

But there’s another factor – a failure to acknowledge the pace of technology change in ever-better solar panels and wind turbines as well as in battery storage. Apparently insurmountable problems are being solved quickly, such as rapid manufacturing and installation of solar panels, the ability to harness low quality winds, and producing batteries able to service different markets at different points in the grid.

Given the pace of change, it would seem sensible to make the most of cheaper solutions which can be built quickly and don’t lock us in or out to technologies for the long term.

In practice, that means we should focus first on Australia’s huge potential for solar on warehouse and factory rooftops close to our cities. It’s easy to store rooftop solar surpluses for local use. We should make the most of the enormous local potential before reaching for complex, risky, expensive and distant alternatives.

By analogy, don’t try to summit the mountain before climbing its foothills. From base camp, we are bound to find the mountain looks quite different to how we imagined it from a great distance.

Energy expert Ted Woodley contributed to this article.![]()

Bruce Mountain, Director, Victoria Energy Policy Centre, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Increasing melting of West Antarctic ice shelves may be unavoidable – new research

The rate at which the warming Southern Ocean melts the West Antarctic ice sheet will speed up rapidly over the course of this century, regardless of how much emissions fall in coming decades, our new research suggests. This ocean-driven melting is expected to increase sea-level rise, with consequences for coastal communities around the world.

The Antarctic ice sheet, the world’s largest volume of land-based ice, is a system of interconnected glaciers comprised of snowfall that remains year-round. Coastal ice shelves are the floating edges of this ice sheet which stabilise the glaciers behind them. The ocean melts these ice shelves from below, and if melting increases and an ice shelf thins, the speed at which these glaciers discharge fresh water into the ocean increases too and sea levels rise.

In West Antarctica, particularly the Amundsen Sea, this process has been underway for decades. Ice shelves are thinning, glaciers are flowing faster towards the ocean and the ice sheet is shrinking. While ocean temperature measurements in this region are limited, modelling suggests it may have warmed as a result of climate change.

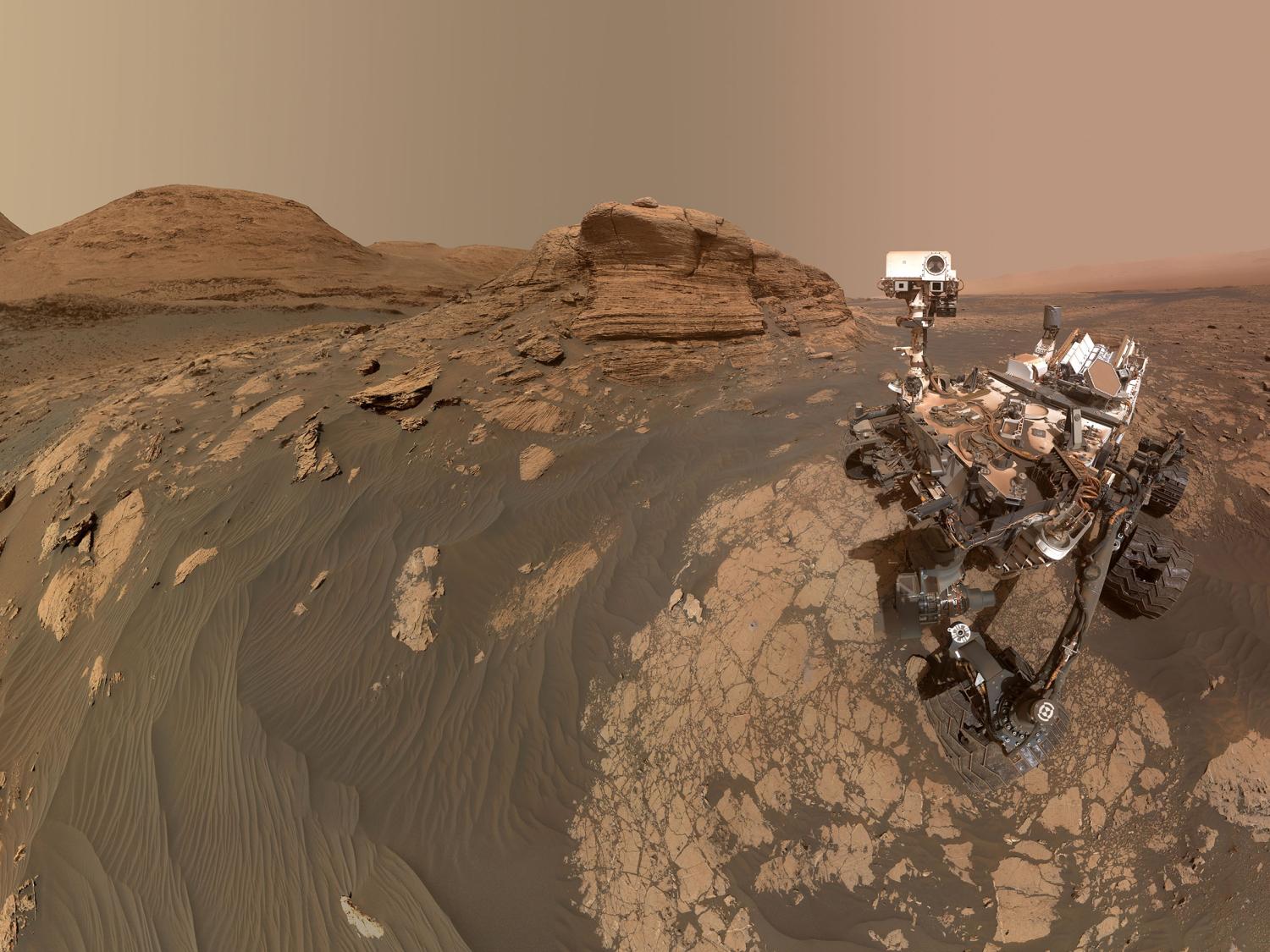

We chose to model the Amundsen Sea because it is the most vulnerable sector of the ice sheet. We used a regional ocean model to find out how ice-shelf melting will change here between now and 2100. How much melting can be prevented by reducing carbon emissions and slowing the rate of climate change – and how much is now unavoidable, no matter what we do?

Rapid Change Is Locked In

We used the UK’s national supercomputer ARCHER2 to run many different simulations of the 21st century, totalling over 4,000 years of ocean warming and ice-shelf melting in the Amundsen Sea.

We considered different trajectories for fossil fuel burning, from the best-case scenario where global warming is limited to 1.5°C in line with the Paris Agreement, to the worst, in which coal, oil and gas use is uncontrolled. We also considered the influence of natural variations in the climate, such as the timing of events such as El Niño.

The results are worrying. In all simulations there is a rapid increase over the course of this century in the rate of ocean warming and ice-shelf melting. Even the best-case scenario in which warming halts at 1.5°C, something that is considered ambitious by many experts, entails a threefold increase in the historical rate of warming and melting.

What’s more, there is little to no difference between the scenarios up to 2045. Ocean warming and ice-shelf melting in the 1.5°C scenario is statistically the same as in a mid-range scenario, which is closer to what existing pledges to reduce fossil fuel use over the coming decades would produce.

The worst-case scenario shows more melting than the others, but only from around mid-century onwards, and many experts think this amount of future fossil fuel burning is unrealistic anyway.

The results imply that we are now committed to rapid ocean warming in the Amundsen Sea until at least 2100, regardless of international policies on fossil fuels.

The increases in warming and melting are the result of ocean currents strengthening and driving more warm water from the deep ocean towards the shallower ice shelves along the coast. Other studies have suggested this process is behind the ice shelf thinning measured by satellites.

How Much Will The Sea Level Rise?

Melting ice shelves are a major cause of sea-level rise, but not the whole story. We can’t put a number on how much sea levels will rise without also simulating the flow of Antarctic glaciers and the rate of snow accumulating on the ice sheet, which our model didn’t include.

But we have every reason to believe that increased ice-shelf melting in this region will cause the rate at which sea levels are rising to speed up.

The West Antarctic ice sheet is already contributing substantially to global sea-level rise and is losing about 80 billion tonnes of ice a year. It contains enough ice to cause up to 5 metres of sea-level rise, but we don’t know how much of it will melt, and how quickly. Our colleagues around the world are working hard to answer this question.

Courage And Hope

There are some consequences of climate change that can no longer be avoided, no matter how much fossil fuel use falls. Substantial melting of West Antarctica up to 2100 may now be one of them.

How do you tell a bad news story? The conventional wisdom is that you’re supposed to give people hope: to say that there’s a disaster behind one door, but we can avoid it if only we choose a different one. What do you do when your science tells you that all doors lead to the same disaster?

Kate Marvel, an atmospheric scientist, said that when it comes to climate change, “we need courage, not hope … Courage is the resolve to do well without the assurance of a happy ending”. In this case, courage means shifting our attention to the longer term.

The future will not end in 2100, even if most people reading this will no longer be around. Our simulations of the 1.5°C scenario show ice-shelf melting starting to plateau by the end of the century, suggesting that further changes in the 22nd century and beyond may still be preventable. Reducing sea-level rise after 2100, or even slowing it down, could save many coastal cities.

Courage means accepting the need to adapt, protecting coastal communities where it’s possible to do so, and rebuilding or abandoning them where it’s not. By predicting future sea-level rise in advance, we’ll have time to plan for it – rather than wait until the ocean is on our doorstep.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Kaitlin Naughten, Ocean-Ice Modeller, British Antarctic Survey; Jan De Rydt, Associate Professor of Polar Glaciology and Oceanography, Northumbria University, Newcastle, and Paul Holland, Ocean and Ice Scientist, British Antarctic Survey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How to beat ‘rollout rage’: the environment-versus-climate battle dividing regional Australia

Peter Burnett, Australian National UniversityThis article is part of a series by The Conversation, Getting to Zero, examining Australia’s energy transition.

In August, Victoria’s Planning Minister Sonya Kilkenny made a decision that could set a difficult precedent for Australia’s effort to get to net-zero emissions by 2050.

In considering the environmental effects of the proposed $1 billion Willatook wind farm 20km north of Port Fairy in southwest Victoria, the minister ruled that the developers, Wind Prospect, had to build wider buffers around the wind turbines and observe a five-month ban on work at the site over each of the two years of construction.

Her reason? To protect the wetlands and breeding season of the brolga, a native crane and a threatened species, and the habitat of the critically endangered southern bent-wing bat.

The decision shocked many clean energy developers. Wind Prospect’s managing director Ben Purcell said the conditions imposed by the minister would reduce the planned number of 59 turbines by two-thirds and make the project “totally unworkable”.

Kilkenny acknowledged that her assessment might reduce the project’s energy output. However, she said “while the transition to renewable energy generation is an important policy and legislative priority for Victoria”, so was “protection of declining biodiversity values”.

The military uses the term “blue on blue” for casualties from friendly fire. In the environmental arena we now risk “green on green” losses, and agonising dilemmas as governments try to reconcile their responses to the world’s two biggest environmental problems: climate change and biodiversity loss.

The Green Vs Green Dilemma

The goal of achieving net zero by 2050 requires nothing less than an economic and social transformation. That includes extensive construction of wind and solar farms, transmission lines, pumped hydro, critical mineral mines and more.

Australia needs to move fast – the Australian Energy Market Operator says 10,000km of high-voltage transmission lines need to be built to support the clean energy transition – but we are already lagging badly.

The problem is that moving fast inflames what is often fierce opposition from local communities. They are especially concerned with the environmental impacts of vast electricity towers and lines running across land they love.

In southern New South Wales, organised groups are fighting to stop the construction of a huge infrastructure project, HumeLink, that seeks to build 360km of transmission lines to connect Snowy Hydro 2.0 and other renewable energy projects to the electricity grid.

Locals say the cities will get the power, while they pay the price. “No one should minimise the consequences of ‘industrialising’ Australia’s iconic locations – would we build power lines above Bondi Beach?” the Snowy Valleys Council asked in a submission to a parliamentary inquiry.

Clean energy developers are caught in a perfect storm, at loggerheads with environmentalists and landholders alike over environmental conditions, proper consultation and compensation, while grappling with long regulatory delays and supply chain blockages for their materials.

They see a system that provides environmental approval on paper but seemingly unworkable conditions and intolerable delays in practice. Does the bureaucracy’s left hand, they wonder, know what its right hand is doing?

Net zero, nature protection and “rollout rage” feel like a toxic mix. Yet we have to find a quick way to deliver the clean energy projects we urgently need.

What Is To Be Done?

The major solution to climate change is to electrify everything, using 100% renewable energy. That means lots of climate-friendly infrastructure.

The major regulatory solution to ongoing biodiversity loss is to stop running down species and ecosystems so deeply that they cannot recover. Among other things, that means protecting sensitive areas, which are sometimes the same areas that need to be cleared, or at least impinged upon, to build new infrastructure.

To get agreement, we need a better way than the standard project-based approval processes and private negotiations between developers and landowners. The underlying principle must be that all citizens, not just directly affected groups, bear the burden of advancing the common good.

As tough as these problems look, elements of a potential solution, at least in outline, are on the table.

These elements are: good environmental information, regional environmental planning and meaningful public participation. The government’s Nature Positive Plan for stronger environmental laws promises all three.

The Albanese Government’s Plan

Australia lags badly in gathering and assembling essential environmental information. Without it, we are flying blind. The government has established Environment Information Australia “to provide an authoritative source of high-quality environmental information.” Although extremely belated, it’s a start.

The Nature Positive Plan may also improve the second element – regional planning – by helping it deal with “green on green” disputes through its proposed “traffic light” system of environmental values.

Places with the highest environmental values (or significant Indigenous and other heritage values) would be placed in “red zones” and be protected from development, climate-friendly or not.

Development would be planned in orange and green zones, but require biodiversity offsets in orange zones.

The catch is that most current biodiversity offsets, which commonly involve putting land into reserve to compensate for land cleared, are environmental failures.

The government has promised to tighten these rules, but advocates ranging from former senior public servant Ken Henry to the Australian Conservation Foundation are pushing for more. A strict approach would make offsets expensive and sometimes impossible to find, but that is the price of becoming nature-positive.

The Need For Regional Planning

Good regional planning – based, say, on Australia’s 54 natural resource management regions – would deal with a bundle of issues upfront. That approach would avoid the environmental “deaths of a thousand cuts” that occur when developments are approved one by one.

But regional planning will only succeed if federal and state governments allocate significant resources and work together. Australia’s record on such cooperation is a sorry one. Again, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek is attempting a belated fresh start, but this will be a particularly rocky road.

The third element – meaningful public participation – involves restoring trust in the system. This requires transparency, proper consultation, and the public’s right to challenge decisions in the courts.

Meaningful consultation requires time, expertise, and properly funded expert bodies that can build a culture of continuous improvement. Again, Australia’s record to date has been piecemeal and poor.

These reforms – better information, planning and public participation – will take time. In the meantime, the precautionary principle suggests a three-pronged approach to keeping us on track for net zero.

One, work proactively with developers to find infrastructure sites that avoid environmentally sensitive areas.

Two, speed up regulatory approvals. Fund well-resourced taskforces for both, as the gains will vastly outweigh the costs.

Three, be generous in compensating landowners where development is approved. Fairness comes at a cost, but unfairness will create an even higher one.

All this makes for a political sandwich of a certain kind. Why would government even consider it?

The answer lays bare the hard choice underlying modern environmental policy. We can accept some pain now, or a lot more later. The prize, though, is priceless: a clean energy system for a stable climate, and a natural environment worth passing on to future generations.![]()

Peter Burnett, Honorary Associate Professor, ANU College of Law, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Himalayan communities are under siege from landslides – and climate change is worsening the crisis

Ashutosh Kumar, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi; Eedy Sana, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi, and Ellen Beatrice Robson, Durham UniversityThree-quarters of annual rain in the Himalayas arrives in the monsoon season from June to September. Within this rainy period are sudden and extremely intense cloudbursts, which often “pop” over a relatively small area (akin to a cloud bursting open like a balloon).

As climate change is making these cloudbursts and other forms of heavy rainfall more intense and more frequent in the Himalayan foothills, the hilly slopes are becoming saturated more frequently, and thus unstable. Rainfall-triggered landslides are already happening extensively across the Himalayas, and things are likely to get worse.

From July to August 2023, the Indian Himalayas, particularly the state of Himachal Pradesh in the northern part of the country, experienced an unprecedented number of cloudbursts which triggered thousands of devastating landslides. The state’s disaster management authority reported that by the end of August, heavy rain and rainfall-triggered landslides had caused 509 fatalities, destroyed at least 2,200 homes and damaged a further 10,000. It is estimated that Himachal Pradesh’s losses from this period amount to US$1.2 billion. Much of the destruction took place during two short periods, one in mid-July and one in mid-August.

The level of damage to buildings, roads and bridges is extremely difficult to comprehend. Several sections of national and state roads have been washed away, a temple in Shimla collapsed and killed 20 people, rural dwellings largely constructed on sloped ground were washed away by rain, and houses are still sliding downhill.

Schools and hospitals have been damaged, posing an ongoing threat to lives. A school in Kullu district was closed for 52 days because the bridge which connected it to a town had been washed away. Local people have had no option but to live in tents with minimal facilities. They are hugely concerned about their safety ahead of a cold and snowy winter.

Four days of heavy rainfall in July 2023 triggered landslides that blocked around 1,300 roads including five national highways, leaving the state almost cut off from the rest of India. This had huge knock-on effects as 1,255 bus routes were suspended, 576 buses were stranded, more than 70,000 tourists had to be evacuated, and people could not access key facilities and services. This impeded emergency responders, causing critical delays in search and rescue operations as well as delivery of aid.

Across the whole of India, the summer monsoon and its related cloudbursts are decreasing. But in the Himalayan foothills, they are increasing significantly – partly because when warm moist air encounters the Himalayan barrier it rapidly lifts and cools, forming large clouds that then dump their rain. With intense rain happening more and more often in the Himalayan foothills, it is likely that 2023’s summer of disasters will occur again.

Unnecessarily Vulnerable

Although climate change may be to blame for the rise in cloudbursts, in an ideal world rainfall alone needn’t lead to disastrous landslides. But the Himalayas have been made more vulnerable by human actions.

The region has largely been deforested, removing tree roots which reinforce the ground and form a crucial barrier that stops soils washing away. And unplanned developments and haphazard construction have destabilised already fragile slopes.

Initial reports on this year’s landslides suggest the worst damages occurred along artificially cut slopes (for roads or buildings), where there has been a lack of proper provisioning for drainage and slope safety. In both India and Nepal, many of the hill roads have been haphazardly constructed, which makes landslides during rainfall more likely. Construction guidelines and building codes are outdated and have been ignored anyway, and there is little assessment of the link between urbanisation and landslide risk.

One obvious solution is to prevent rain from penetrating the ground, so the slopes avoid losing any strength. However, if the soil is entirely prevented from absorbing any rain, the water will instead run off the surface and cause greater flooding problems further downhill.

One engineering solution is to place an artificial soil layer above the natural soil to temporarily hold water in the surface when it is raining extremely hard, preventing it penetrating deeper within the slope. This “climate adaptive barrier layer” will then release water back to the atmosphere during a later drying period.

As the heavy rain intensifies, it will be hugely important for the Himalayas to implement new user-friendly and reliable construction guidelines that factor in how the climate is changing. Landslides can’t be avoided entirely, and India certainly won’t be able to reverse global warming and the increase in cloudbursts any time soon. But these preventive actions should at least make communities more resilient to the changing climate.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Ashutosh Kumar, Assistant Professor, School of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi; Eedy Sana, PhD Candidate, Geotechnical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi, and Ellen Beatrice Robson, Postdoctoral research associate, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

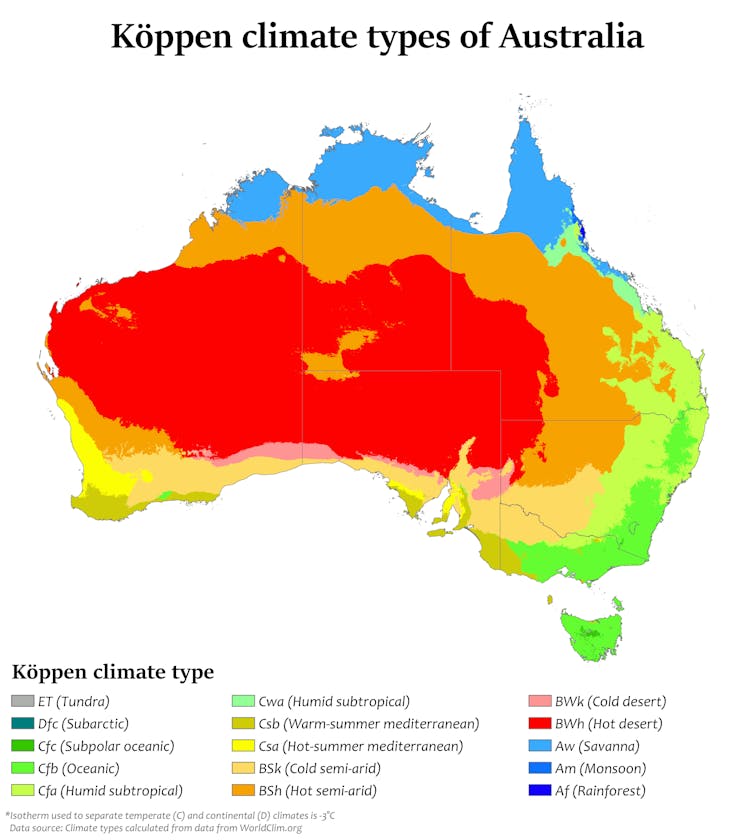

Remember the climate map from your school atlas? Here’s what climate change is doing to it

You probably saw a multi-coloured climate map at least once in school. You might have pored over it, fascinated. Was Antarctica really a cold desert? And why was so much of Russia listed as tundra?

Almost always, those maps were based on the climate classification system proposed by Wladimir Köppen. The colours are chosen to suit our imagination: Australia with its red desert centre, surrounded by a yellow or orange semi-arid fringe and more lush green climates along many coastlines and hinterland.

But these maps were made for a climate that doesn’t exist any more. Our new research shows just how fast climate change has altered these maps – and how they will continue to change.

Our web app lets you see for yourself for any country in the world and for different emission scenarios. For Australia, you can watch the hot desert area expand and the temperate areas shrink.

The climate map of the future below assumes nations meet their climate goals. It could be far worse. Or it could be better, if we finally treat climate change with the urgency it needs.

How Do You Classify A Climate?

Köppen was a 19th century Russian botanist who later retrained in meteorology. Over his career, he combined both interests, becoming fascinated by the relationship between climate and types of vegetation.

Around 1900, he proposed the influential climate classification system which now bears his name alongside his collaborator, Rudolf Geiger. It remains by far the most used classification system, as it combines different aspects of climate data into types of landscapes and vegetation types we can actually picture, from rainforests, savannahs and deserts to temperate and boreal forests, tundras, glaciers and ice sheets.

The Köppen-Geiger classification has five major climate classes: tropical, dry, temperate, cold and polar. These are divided into 30 subclasses based on the amount of rain and temperatures in summer and winter.

You might think it would be relatively straightforward to figure out if climate change has pushed a region into a new classification. Add the recorded global warming of 1.2°C so far and see if that changes anything.

Alas, it’s not that simple. This is because climate change can have weird regional effects. We’re getting much more rain in some areas, and much less in others. Some regions are warming faster than the global average and others are warming slower.

Climate models predict there will continue to be such differences. Plus, a degree of warming will have a greater impact at the edge of a glacier than in the Sahara.

To find out what will happen, we analysed vast databases of past weather observations and future climate projections under different socio-economic and emission pathways to redraw the Köppen map. We did so at a very fine scale, dividing the world up into square kilometres so we could observe localised changes in mountainous regions and on small islands.

Change Has Already Happened – And There’s Much More To Come

The results were surprising. In some parts of the world, climate zones have already shifted considerably since Köppen drew his first climate map more than a century ago. The fastest change has been in the last few decades. The largest changes have been in cold and polar climates, which have become less cold and sometimes drier.

Eastern Europe has been a climate change hotspot over the last century. Its continental climate of cold winters and warm summers has given way to a temperate climate with hot summers.

Several countries have already changed climate zones across more than half of their area. Hungary, for instance, has changed the most of any nation. A whopping 81% of the country has already moved into a different, more temperate climate zone. Other global hot spots include central Europe, the Middle East and South Korea.

Our projections show these regions are among those to undergo the biggest climatic shifts through to 2100. Some areas will shift climate zones more than once.

Countries at higher latitudes will see some of the largest changes. Almost a quarter (24%) of both Canada and Russia have already moved into another climate zone since Köppen’s first map. Another 39-40% of their immense landmasses will follow suit before the end of the century.

A similar story applies to Europe, where climate zones will change in between one-third and two-thirds of the area in most countries.

South Africa and neighbouring countries Eswatini and Lesotho are the fastest changing countries in the Southern Hemisphere. Their climate zones have shifted across 28% of their combined area. By 2100, an additional 44% will change.

In Australia, climate zones have already shifted across 14% of the country, with another 13% predicted during the remainder of this century.

You might wonder how it can be that climate zones don’t move in some areas. That is because each Köppen climate zone represents a specific range of temperature and rainfall conditions, and a region can move within that range.

But Köppen didn’t foresee what’s happening now. In his classification, deserts and tropical climates are at the high end of the temperature scale and cannot change - they just get hotter.

What Will This Mean On The Ground?

Changes as dramatic and rapid as this are already upending natural ecosystems. As climate change progresses, it will force significant change to our farms and infrastructure. Humanity gets half its calories from just three plants – rice, maize and wheat – and each of these has a preferred climate.

Warmer and drier climates bring more drought as well as crop loss, water shortages, ecosystem degradation, bushfires and desertification. Warmer winters, extreme heat, drought and fire have been pummelling forests the world over - from the cold high latitudes in Canada and Russia to the dry forests in the Mediterranean region, California and Australia. Even the Amazon rainforest is affected.

Of course, some changes may be beneficial for people, such as better agricultural conditions or lower heating costs in cold regions. But the overall picture is one of calamitous change.

Over the next decades, it will take all of humanity’s commitment and ingenuity to avoid a major climate catastrophe.![]()

Albert Van Dijk, Professor, Water and Landscape Dynamics, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University; Hylke Beck, Assistant Professor, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, and Pablo Rozas Larraondo, Research fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Beyond Juukan Gorge: how First Nations people are taking charge of clean energy projects on their land

Lily O'Neill, The University of Melbourne; Brad Riley, Australian National University; Ganur Maynard, Indigenous Knowledge, and Janet Hunt, Australian National UniversityThis article is part of a series by The Conversation, Getting to Zero, examining Australia’s energy transition.

Many of the big wind and solar farms planned to help Australia achieve net zero emissions by 2050 will be built on the lands and waters of First Nations peoples. More than half of the projects that will extract critical minerals to drive the global clean energy transition overlap with Indigenous-held lands.

Australia’s Pilbara and Kimberley regions have high rates of Indigenous land tenure, while hosting some of world’s best co-located solar and wind energy resources. Such abundance presents big opportunities for energy exports, green steel and zero carbon products.

Almost 60% of Australia is subject to some level of First Nations’ rights and interests, including exclusive possession rights (akin to freehold) over a quarter of the continent. So the stakes for all players are high.

In 2020, after news Rio Tinto had legally destroyed the sacred Juukan Gorge rock shelter in order to gain access to more than $100 million worth of iron ore, we wrote an article questioning how much legal say First Nations people would have over massive new wind and solar farms planned for their Country. We asked whether the move to a zero-carbon economy “would be a just transition for First Nations?”

The Long But Hopeful Journey Back From Juukan Gorge

Much has happened in the past three years, and while more needs to be done, some signs are promising.

First, the furore and subsequent parliamentary inquiry following the Juukan Gorge incident forced the resignation of Rio Tinto boss Jean-Sebastien Jacques. Companies were put on notice that they can no longer run roughshod over First Nations communities. Research in progress indicates the clean energy industry has heard this message.

Second, in 2021 the First Nations Clean Energy Network – a group of prominent First Nations community organisers, lawyers, engineers and financial experts – was created and began to undertake significant advocacy work with governments and industry.

The network has released several useful guides on best practice on First Peoples’ Country. Again, research indicates the clean energy industry is paying attention to the work of the network.

Third, there is a question whether the Native Title Act allows large-scale clean energy developments to go ahead without native title holders’ permission. We are increasingly convinced the only way such developments will gain approval through the Native Title Act is through an Indigenous Land Use Agreement.

Moreover, Queensland and Western Australia have both implemented policies and South Australia is developing legislation that make it clear these states will require renewable energy developers to negotiate an agreement with First Nations land holders. Because these agreements are voluntary, native title holders can refuse to allow large wind and solar farms on their Country.

As always, these decisions come with caveats. Governments can compulsorily acquire land, and many of the power imbalances we observed in our earlier article persist. These include the power corporations have – unlike most Indigenous communities – to employ independent legal and technical advice about proposed projects, and to easily access finance when a community would like to develop a project itself.

Promising Partnerships On The Road To Net Zero

Are First Nations peoples refusing to have wind and solar projects on their land? No, they are not. Many significant proposed projects announced in the last few years show huge promise in terms of First Nations ownership and control.

In Western Australia the partnership between Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation and renewable energy company ACEN plans to build three gigawatts of solar and wind infrastructure on Yindjibarndi exclusive possession native title. Mirning traditional owners hold equity stakes in one of the largest green energy projects in the world, the massive Western Green Energy Hub located on their lands in the great Australian Bight.

Further north, Balanggarra traditional owners, the MG Corporation and the Kimberley Land Council have together announced a landmark East Kimberley Clean Energy project aimed at producing green hydrogen and ammonia for export.

Across the border in the Northern Territory, Larrakia Nation and the Jawoyn Association have created Desert Springs Octopus, a majority Indigenous-owned company backed by Octopus Australia.

Still, much more needs to happen to provide Indigenous communities with proper consent and control. In its 2023 amendments to allow for renewable energy projects on pastoral leases, the Western Australian government could have given native title holders more control but it chose not to. And much needed reforms to cultural heritage laws in WA were scrapped following a backlash from farmers.

In New South Wales, some clean energy developers seem to be avoiding Aboriginal lands, perhaps because they think it will be easier to negotiate with individual landholders. The result is lost opportunities for partnership, much needed know-how and mutual benefit.

In the case of critical mineral deposits on or near lands subject to First Nations’ title, not nearly enough has been done to ensure these communities will benefit from their extraction.

Why Free, Prior And Informed Consent Is Crucial

To ensure the net zero transition is just, First Nations must be guaranteed “free, prior and informed consent” to any renewable energy or critical mineral project proposed for their lands and waters, as the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples makes clear.

So long as governments can compulsorily acquire native title to expedite a renewable energy project and miners are allowed to mine critical minerals (or any mineral) without native title holders’ consent, the net zero transition will transgress this internationally recognised right.

The Commonwealth government has agreed in principle with the recommendations of the Juukan Gorge inquiry to review native title legislation to address inequalities in the position of First Nations peoples when they are negotiating access to their lands and waters.

The meaningful participation of First Nations rights holders is critical to de-risking clean energy projects. Communities must decide the forms participation takes – full or part ownership, leasing and so on – after they have properly assessed their options. Rapid electrification through wind and solar developments cannot come at the expense of land clearing and loss of biodiversity.

Ongoing research highlights that when negotiating land access for these projects, First Nations people are putting protection of the environment first when negotiating the footprint of these developments. That’s good news for all Australians.![]()

Lily O'Neill, Senior Research Fellow, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne; Brad Riley, Research Fellow, Australian National University; Ganur Maynard, Indigenous Knowledge Holder, Indigenous Knowledge, and Janet Hunt, Honorary Associate Professor, CAEPR, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

From meerkat school to whale-tail slapping and oyster smashing, how clever predators shape their world

In the 1980s a single humpback whale in the Gulf of Maine developed the “lobtail feeding method”. This unique hunting method of slapping the water’s surface appears to drive fish into dense schools, making it easier to consume them. Lobtail feeding caught on. Now many humpback whales are doing it.

Ecologists have long thought animals acted on instinct alone. But a growing body of evidence shows many animals, much like us, have complex brains and social lives.

In our new research, we argue the science of ecology can learn a great deal from the study of animal cognition and culture. Cognition is what goes on in the mind, which determines how animals perceive and respond to the world around them. Culture is the development and spread of socially learned behaviours. These are important – but generally overlooked – mechanisms influencing ecosystems.

More Than Cogs In The Eco-Machine

Research shows prey are adept at learning from previous encounters with predators. They remember what predators look like, what they smell like and the locations and times they are active.

This means every time an animal encounters a predator they can gather knowledge about how to improve their chances of survival.

Predators learn as well. Meerkat pups go to meerkat “school”. Eating dangerous prey such as scorpions is challenging because scorpion toxin can be fatal. To overcome this, meerkat teach their young how to remove scorpion stingers, allowing them to safely eat them.