Inbox and environment news: Issue 604

November 5 - 11, 2023: Issue 604

Mother Brushtail Killed On Barrenjoey Road: Baby Cried All Night - Powerful Owl Struck At Same Time Careel Bay During Owlet Fledgling Season

- Formal recovery strategies for every nationally threatened bird and species.

- National environmental standards to support more rigorous and consistent decision making.

- An independent national Environmental Protection Agency (to be called Environment Protection Australia) that would sit at arm’s length from the Government of the day and would be responsible for making decisions on project proposals that could harm threatened birds and important natural areas.

- The development of a more robust system for the management and use of environmental data by a statutory office, Environment Information Australia.

- Boosting people’s confidence in the new laws. To improve public trust in the new laws and the institutions that will be responsible for delivering them the Government should provide the public with an opportunity to review and have its say.

- The Minister of the day will retain a broad general ‘call in’ power that will allow them to make a decision on individual proposals that are deemed to warrant ministerial intervention. What is proposed in this new package is weaker than the settings under current laws.

- The new laws envisage a system of “restoration actions’ – offsets – and “restoration contributions” to compensate for “residual” environmental impacts. This mechanism will need to be carefully designed, implemented and monitored to ensure that it supports real improvements for wildlife and their habitat, and doesn’t facilitate destruction.

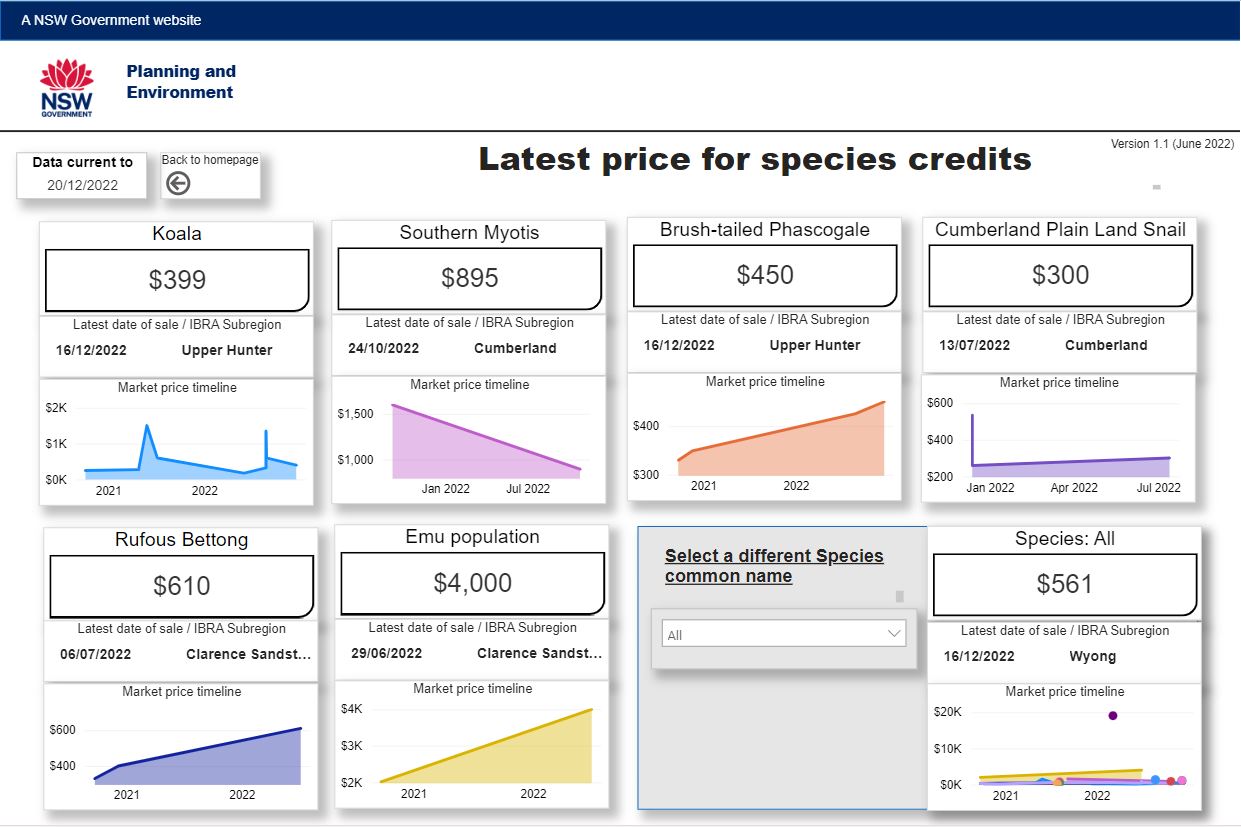

"It is noted that the off-set requirement could be met by total payment of $8,850,139.39 into the Biodiversity Conservation Fund in accordance with the NSW Biodiversity Offsets Scheme."

Transport for NSW (Transport) proposes to carry out road improvements along Wakehurst Parkway between Frenchs Forest Road, Frenchs Forest and Pittwater Road, North Narrabeen.These include intersection upgrades and focus on improving safety and capacity for this key road link in Sydney’s northern beaches.A Review of Environmental Factors (REF) including Biodiversity Development Assessment Report (BDAR) has been prepared for the proposal. These documents outline the proposed work, potential construction and environmental impacts and mitigation measures.The documents will be available for viewing on the project webpage from Monday 6 November.Formal submissions about the proposal are welcomed by emailing northplace@transport.nsw.gov.au by 5pm Wednesday 6 December.The Wakehurst Parkway project team will be at Oxford Falls Main Hall at Oxford Falls Peace Park on Thursday 16 November from 3pm to 6pm, and at Bilarong Community Hall on Saturday 18 November from 10am to 2pm.

Narrabeen Lagoon Entrance Works 2023: Update Pics

Wakehurst Parkway Update: REF For Proposed Works Available From November 6

Scarlet Honeyeaters Spotted In Avalon Beach: Spring 2023

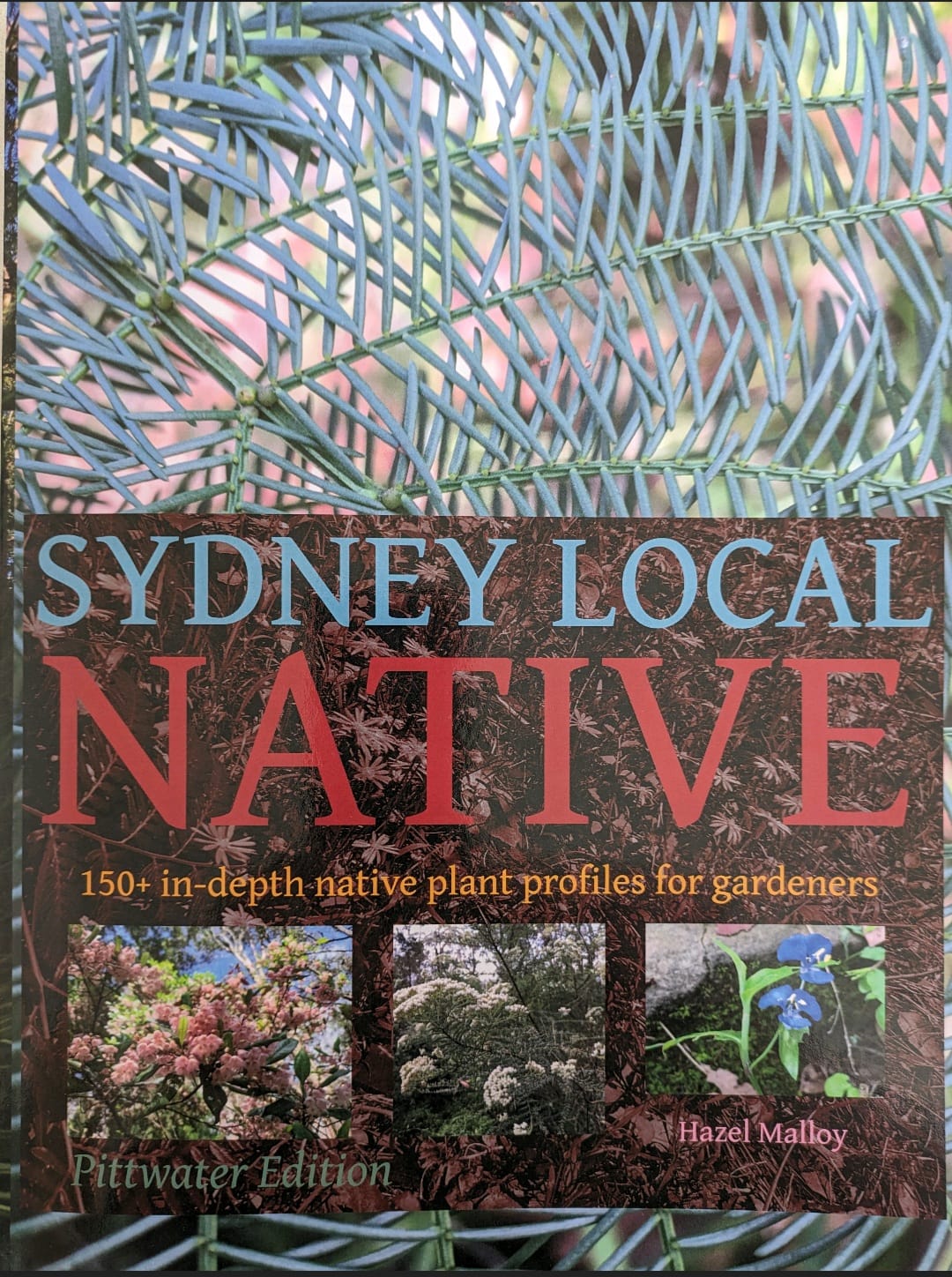

Sydney Local Native: Pittwater Edition Published

- average maximum height and width

- a description of the plant's form

- flower colour and flowering season

- an overview of the plant's best features

- its preferences for soil, water and light

- where it is naturally distributed.

A monster eddy current is spinning into existence off the coast of Sydney. Will it bring a new marine heatwave?

Right now, there’s something big spinning off the coast from Sydney – a giant rotating vortex of sea water, powerful enough to dominate the ocean currents off south-eastern Australia.

Oceanographers describe these spinning water bodies as “eddies” – but they’re not the small eddy currents you see in creeks or rivers. Ocean eddies are enormous. They’re usually hundreds of kilometres across (100–300km), up to 2km deep and can be visible from space.

It turns out these eddies drive change underwater by spawning marine heatwaves. Our new research demonstrates the link between a warm ocean eddy and a record-breaking marine heatwave which struck off Sydney from December 2021 to February 2022.

Now it’s happening again. An even bigger eddy is forming about 50km off Sydney. We have just returned from a 24-day research voyage on CSIRO’s research vessel RV Investigator to explore this monster eddy.

Our estimates suggest this 400km wide beast holds 30% more heat than normal for this part of the ocean. Its currents are spinning at 8km per hour. And the temperatures deep underwater are up to 3°C above normal. If it moves close to shore, it could trigger another coastal marine heatwave.

How Can An Eddy Current Make A Heatwave?

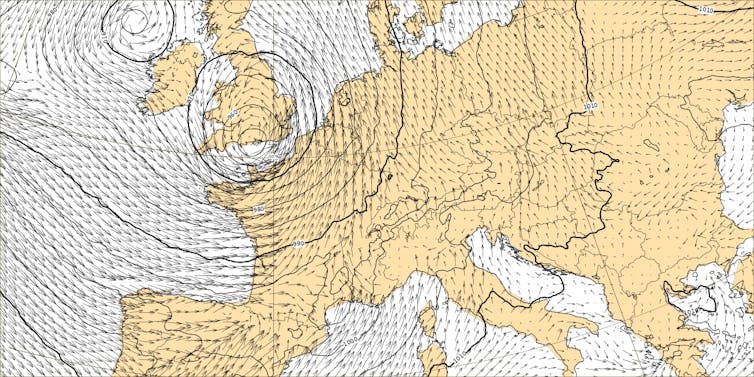

Eddies are the ocean equivalent of storms in the atmosphere. Like weather patterns, they can be warm or cold. But ocean eddies can shape the ocean’s patterns of life.

Warm eddies are like ocean deserts with little life, while cold eddies are typically much more productive. That’s because they draw up nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous from the deep sea, which become food for plankton.

Just as storms can in the atmosphere, ocean eddies can drive extreme “ocean weather”. That’s because warm eddies can bring in masses of warm water and keep it there for months. Sea life is often very finely attuned to temperature, so a sudden heatwave like this can heavily impact ecosystems.

It’s important to better understand how eddy currents grow, move and decay better. That’s because they can store large amounts of heat and can temporarily increase coastal sea levels.

What we do know is that warm eddies along Australia’s east coast can be fed by the East Australian Current when it becomes unstable. The current wobbles back and forth until eventually the wobbles form a coherent circle – an eddy – or adding to an existing one. It’s like a garden hose thrashing around on the grass when the flow is too great. These unstable currents can be small, on the kilometre scale, or huge.

Our research pinpointed the root cause of the 2021 marine heatwave off Sydney. A large warm eddy formed. But it couldn’t spiral away into deeper waters, because there were cold eddies to the north and south preventing it. That’s very similar to what can happen in the atmosphere, where a high pressure system can be held in place by other weather systems.

Now, it looks as if history is repeating.

Over the past month, an enormous eddy – fully 400km wide and 3km deep – has been spinning up just off southeastern Australia. It’s being fed by the warm East Australian Current, which brings warm water from the tropics down to more temperate waters. This eddy is bigger and warmer than most eddies in the region, especially at this time of year. It has been growing over the past month, and is pushing up against cold waters to the south. Where the two systems meet there are very strong temperature differences – up to 5°C over just 4km.

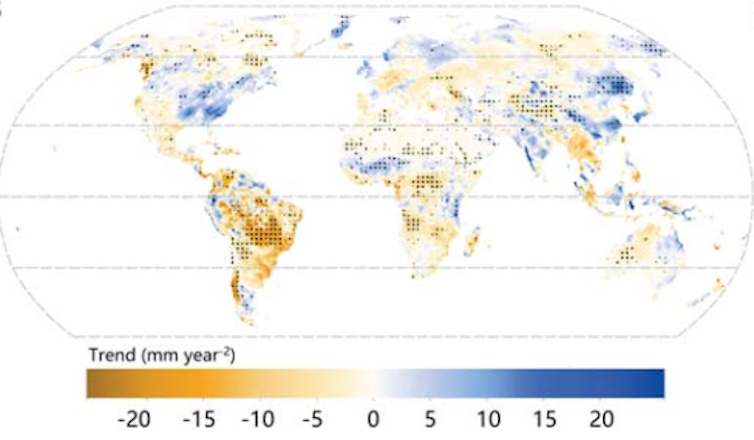

You can get some insight into how eddy currents behave from satellites.

Our trip on the research vessel RV Investigator made it possible for us to grasp how this powerful current was behaving – in three dimensions.

We also released drifters, GPS-tracked buoys which float around the eddy centre in a massive circle. Some have been carried more than 2,000km in the last month, passing where they originally started. Others have escaped the eddy and headed east into the Pacific.

These sensors and instruments have given us vital information. Now we know the water in the eddy is flowing at a fast walking pace, around 8km per hour. And we know that while the currents within the eddy are rotating quickly, the eddy itself has remained fairly stationary off the NSW coast, growing with warm waters from further north.

We also deployed five diving Argo floats. Satellite data shows us surface temperatures in the eddy have hit 23°C, two degrees above average for a month. But Argo floats show us the temperatures are even more extreme 500m below the surface, more than 3°C above average.

What happens to eddies? Like atmospheric systems, these are effectively heat engines. They transport heat to new areas as they whirl in the ocean. While they hold heat a long time, eventually it’s lost to the atmosphere and through mixing at the edges of the current. Eventually, they disappear.

But as we head into summer, the mega eddy is unlikely to go anywhere. If it moves towards the coast, where marine life is concentrated, we will see water temperatures spike – and possibly, underwater disaster for many species.

We would like to thank the RV Investigator’s Master, Captain Andrew Roebuck, Deck Officers and crew and the CSIRO technical staff.![]()

Moninya Roughan, Professor in Oceanography, UNSW Sydney; Amandine Schaeffer, Senior lecturer, UNSW Sydney; Junde Li, Postdoctoral research associate, and Shane Keating, Associate Professor, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NSW Government's Update On The Creation Of The Great Koala National Park

The release of an 8 years old female back into Angophora Reserve after she had been bombarded by magpies. Taronga Zoo picked her up and nursed her back to health before the release on November 5th, 1989. Doug Bladen and Marita Macrae are in the background representing the Avalon Preservation Trust (now APA). Photo by Geoff Searl OAM

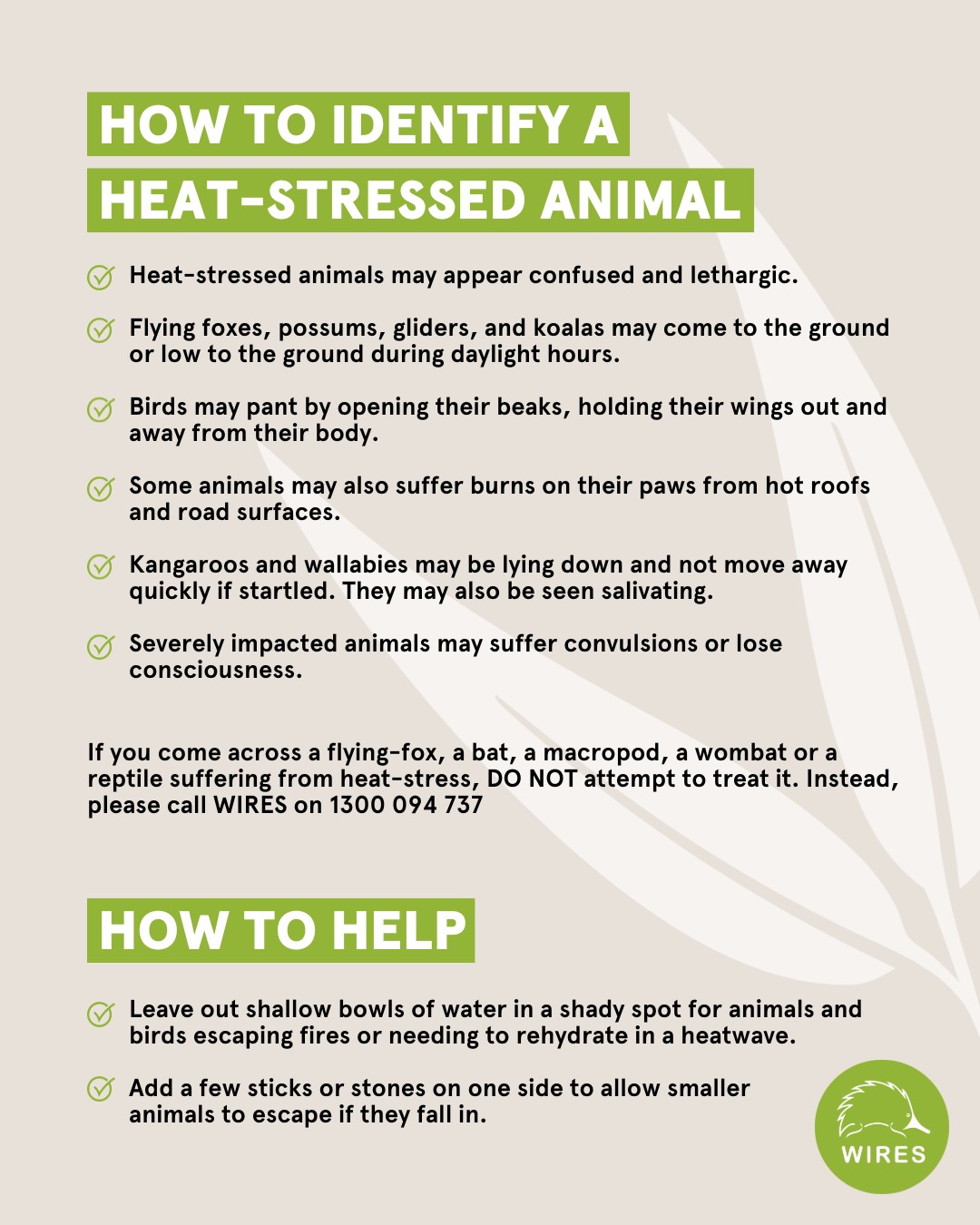

Please Look Out For Wildlife During Heatwave Events

AER Releases Social Licence For Electricity Transmission Directions Paper

- What expectations should be held of transmission businesses in undertaking community engagement

- What outcomes need to be achieved from engagement

- When and how social licence issues can be factored into regulatory tests for the approval of and recovery of cost for new transmission development

- What evidence is needed to justify transmission network expansion and associated expenditure.

- clearly identify the information that is the subject of the confidentiality claim

- provide a non-confidential version of the submission in a form suitable for publication.

Bushwalk Fundraiser

- Friday 10 November

- Friday 8 December

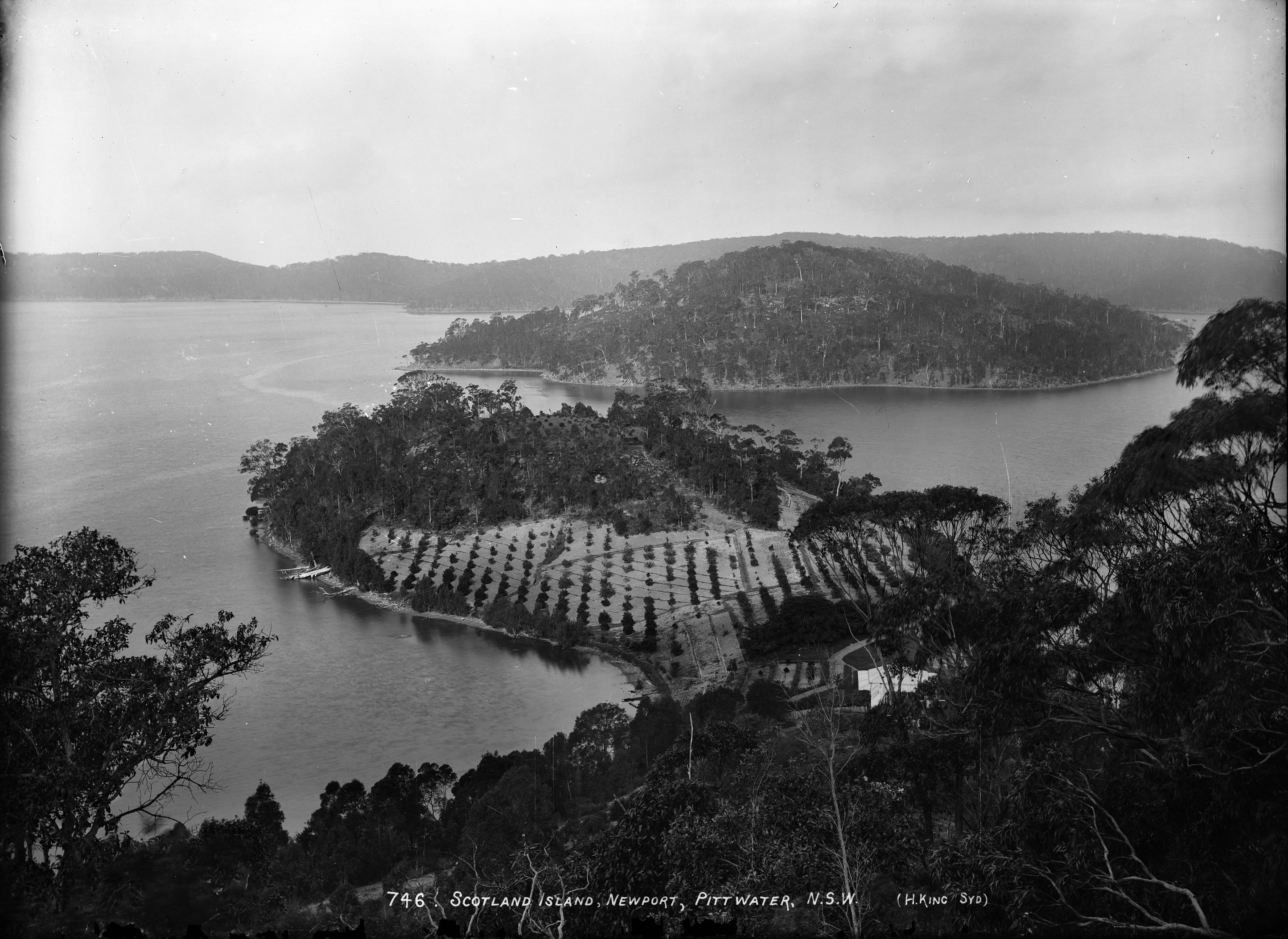

'Scotland Island, Newport, Pittwater, N.S.W.', photo by Henry King, Sydney, Australia, c. 1880-1886. and section from to show cottage on neck of peninsula at western end with no chimneys through roof. From Tyrell Collection, courtesy Powerhouse Museum

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group Begins

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

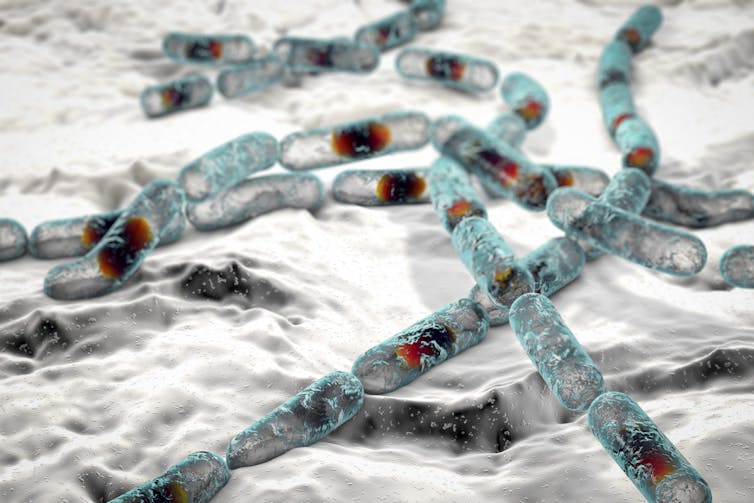

The Beetaloo gas field is a climate bomb. How did CSIRO modelling make it look otherwise?

Even as Australia braces for a summer of projected extreme heatwaves and bushfires amid the intensifying climate crisis, the fossil gas industry is gearing up for a truly enormous new fracking project in the Northern Territory’s Beetaloo Basin.

In February, a CSIRO-backed report was published, stating Beetaloo could be developed without adding to Australia’s net emissions. In May, the Northern Territory government gave the green light to the project, citing the report as evidence emissions could be “mitigated, reduced or in some cases eliminated”.

This report is important. It was produced by CSIRO’s Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance in response to a key recommendation from the NT’s Pepper Inquiry into fracking. That recommendation? Territory and federal governments should “seek to ensure” no net increase in life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions in Australia from fracking in the NT.

How could it find a massive new fossil fuel field won’t add to emissions? Our forensic analysis of the report found it made the most optimistic assumptions about emissions at every stage, and placed far too much faith in Australia’s ability to offset emissions.

Remind Me – How Big Is Beetaloo?

Big. The fossil fuel basin 500 kilometres south of Darwin is bigger than any current gas project on Western Australia’s North-West Shelf.

We estimate 1.2 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions would be emitted over 25 years to 2050 – a figure 45% higher than in the report.

Our analysis shows annual domestic emissions from fracking in the Beetaloo and processing at Darwin’s Middle Arm industrial precinct would produce up to 49 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, 11% of Australia’s total emissions in 2021. That means a single project would produce more emissions than the entire reduction goal under Labor’s revised safeguard mechanism.

Our deep dive into the CSIRO report found its cumulative domestic emissions projections are underestimates of up to 84% in some cases. Emissions are underestimated at almost every stage, from how emissions-intensive fracked gas is to how much methane is lost to the atmosphere and how much is emitted in manufacturing LNG. We have submitted our report to the Senate Inquiry into Middle Arm.

The report also underestimates upstream emissions – emissions created by actually fracking the gas and transporting it to Darwin – by up to 110%, and emissions from turning gas into LNG at the plant by up to 89%.

A CSIRO spokesperson told The Conversation:

CSIRO scientists have delivered a robust and detailed technical analysis, confirmed through an intensive peer review process, of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with onshore gas production scenarios in the Beetaloo Sub-basin, and important information about realistic mitigation and offset options. CSIRO stands behind the quality of its research and the integrity of its peer review process.

No Net Increase – By The Power Of Offsets?

Any large new fossil gas project would, of course, add more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. So how could it represent “no net increase”?

The answer: offsets. The report recommends sequestering carbon in Australia’s soils and forests to offset the global warming caused by burning Beetaloo’s single product, gas.

As we and many other experts have demonstrated, offsets are riddled with flaws. Every tonne of fossil carbon we emit stays in the atmosphere far longer than the 100 years a land-based offset might store carbon. Around 40% of our emissions remain in the atmosphere after 100 years. Up to a quarter is still there after 1,000 years. And up to 20% is still there after 10,000 years.

Offsets often don’t work over the short term, because many are simply not real or not additional to what would otherwise have happened. Their problems are now well known, but not broadly accepted by Australian policymakers.

CSIRO’s report uses overly optimistic estimates of how many offsets are likely to be available. If they could be realised, the offsets required for Beetaloo would take up very large areas of land in Australia – up to 2.9 million hectares, 12 times the size of the Australian Capital Territory.

The Problem With Blue Hydrogen

Blue hydrogen is touted as another use for Beetaloo gas. Here, hydrogen is made from fossil gas, with emissions captured and stored to reduce the climate impact of Beetaloo.

CSIRO’s report assumes fossil gas facilities can capture 90% of the carbon from the project. This is way too optimistic. To date, no commercial blue hydrogen facility in the world has achieved anything close.

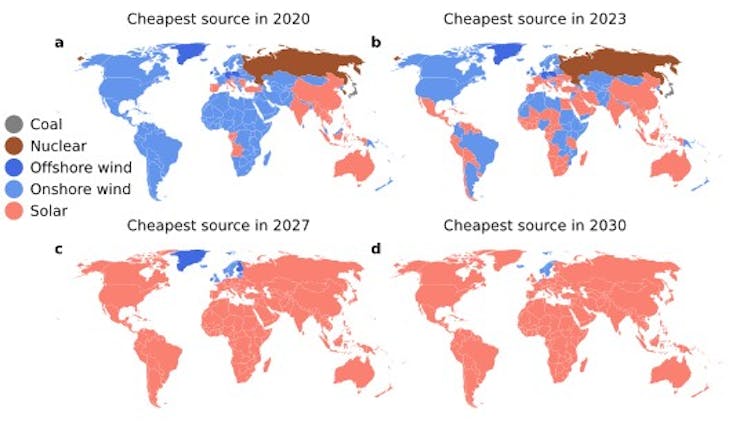

Even with carbon capture and storage research shows blue hydrogen is very carbon intensive. Energy experts project that green hydrogen – made by breaking water apart with clean energy – will undercut blue hydrogen on cost by around 2030.

What About The Middle Arm LNG Project?

After the gas is extracted by hydraulic fracturing, it would be transported to the Middle Arm precinct in Darwin to get ready for shipping. We analysed the total cumulative emissions, including exports. The result? 25 years of emissions from this project and its large LNG plant in Darwin would be more than three times the entire country’s emissions in 2021.

One of the companies looking to profit from Beetaloo, Tamboran Energy, has already announced plans to expand after 2030. If this gets up, it would add the equivalent of another 30–38 million cars (10–13% of Australia’s 2021 emissions). Given there are only 15 million cars in Australia, this would wipe out the benefit of making our entire light vehicle fleet electric by the mid 2030s.

The International Energy Agency has shown we have to slash demand for fossil fuels 25% by 2030 and 80% by 2050 to keep heating under 1.5°C and limit the worst effects of climate change.

If it is allowed to proceed, this single project could undo all of our efforts to cut emissions. Beetaloo and Middle Arm are a climate bomb. They will produce vast volumes of emissions which cannot be offset. The atmosphere doesn’t respond to clever accounting, overly optimistic projections and reliance on offsets – only on how many tonnes of emissions end up there.![]()

Bill Hare, Adjunct Professor, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Carbon budget for 1.5°C will run out in six years at current emissions levels – new research

If humanity wants to have a 50-50 chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, we can only emit another 250 gigatonnes (billion metric tonnes) of CO₂. This effectively gives the world just six years to get to net zero, according to calculations in our new paper published in Nature Climate Change.

The global level of emissions is presently 40 gigatonnes of CO₂ per year. And, as this figure was calculated from the start of 2023, the time limit may be actually closer to five years.

Our estimate is consistent with an assessment published by 50 leading climate scientists in June and updates with new climate data many of the key figures reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in August 2021.

How much CO₂ can still be emitted while remaining under a certain level of warming is referred to as the “carbon budget”. The carbon budget concept works because the increase in Earth’s global mean surface temperature has increased in a linear fashion with the total amount of CO₂ people have emitted since the industrial revolution.

The other side of this equation is that, roughly speaking, warming stops when CO₂ emissions stop: in other words, at net zero CO₂. This explains why net zero is such an important concept and why so many countries, cities, and companies have adopted net zero targets.

We revised the remaining carbon budget down from the 500 gigatonnes reported by the the IPCC from the start of 2020. Some of this revision is merely timing: three years and 120 gigatonnes of CO₂ emissions later, the world is closer to the 1.5°C threshold. Improvements we made to the method for calculating budget adjustments shrank the remaining budget further.

Clearing The Air

Alongside CO₂, humanity emits other greenhouse gases and air pollutants that contribute to climate change. We adjusted the budget to account for the projected warming caused by these non-CO₂ pollutants. To do this, we used a large database of future emissions scenarios to determine how non-CO₂ warming is related to total warming.

Some of the warming caused by greenhouse gases is offset by cooling aerosols such as sulphates – air pollutants that are emitted along with CO₂ from car exhausts and furnaces. Almost all emissions scenarios project a reduction in aerosol emissions in the future, regardless of whether fossil fuels are phased out or CO₂ emissions continue unabated. Even in scenarios where CO₂ emissions increase, scientists expect stricter air quality legislation and cleaner combustion.

In its most recent report, the IPCC updated its best estimate of how much air pollution cools the climate. As a result, we expect that falling air pollution in future will contribute more to warming than previously assessed. This reduces the remaining 1.5°C budget by about another 110 gigatonnes.

Other updates we made to the carbon budget methodology tend to reduce the budget even more, such as projections of thawing permafrost that were not included in earlier estimates.

All Is Not Lost

It is important to stress that many aspects of our carbon budget estimate are uncertain. The balance of non-CO₂ pollutants in future emissions scenarios can be as influential on the remaining carbon budget as different interpretations of how the climate is likely to respond.

We also do not know for sure whether the planet will really stop warming at net zero CO₂ emissions. On average, evidence from climate models tends to suggest it will, but some models show substantial warming continuing for decades after net zero is reached. If further warming after net zero is the case, the budget would be further reduced.

These uncertain factors are why we quote a 50/50 likelihood of limiting warming to 1.5°C at 250 gigatonnes of CO₂. A more risk-averse assessment would report a two-in-three chance of staying under 1.5°C with a remaining budget of 60 gigatonnes - or one-and-a-half years of current emissions.

Time is running out to limit global heating to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. While we have revised the remaining carbon budget, the message from earlier assessments is unchanged: a dramatic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions is necessary to halt climate change.

It looks less likely that we will limit warming to 1.5°C, but this does not mean that we should give up hope. Our update also revised the budget for 2°C downwards relative to the IPCC’s 2021 estimate, but by a smaller amount – from 1,350 to 1,220 gigatonnes, or from 34 to 30 years of current emissions. If current national climate policies are fully implemented (admittedly, an optimistic scenario), this may be enough to hold warming below 2°C.

The risks of triggering tipping points such as the dieback of the Amazon rainforest increase – sometimes sharply – with increasing warming, but 1.5°C itself is not a hard boundary beyond which climate chaos abounds.

With effective action on emissions, we can still limit peak warming to 1.6°C or 1.7°C, with a view to bringing temperatures back below 1.5°C in the longer term.

This is a goal absolutely worth pursuing.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Chris Smith, Senior Research Fellow in Climate Science, University of Leeds and Robin Lamboll, Research Fellow in Atmospheric Science, Imperial College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

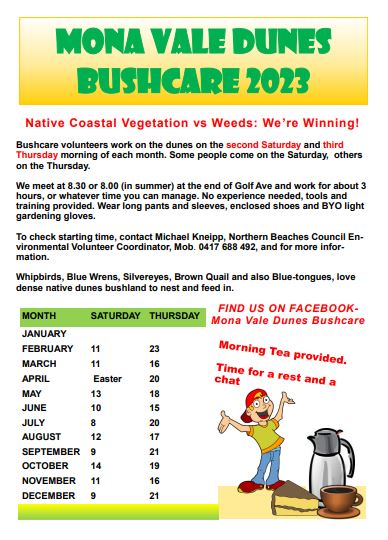

Queensland’s fires are not easing at night. That’s a bad sign for the summer ahead

Calum Cunningham, University of Tasmania; David Bowman, University of Tasmania, and Grant Williamson, University of TasmaniaThis week, dozens of fires have burned across Queensland. More homes have burned in the state than during the 2019–2020 Black Summer – 57 so far this year, compared to 49.

The question many are asking is – are these fires normal? Our analysis shows these fires are weird in at least two ways.

First, many more than usual are burning through the night. This is anomalous, as nighttime usually brings lower temperatures and more moisture in the air, slowing or quelling fires. Queensland’s south-east and Western Downs regions are seeing more than five times more nighttime hotspots than average. And second, these fires are early in the season – especially the nighttime fires.

Why? Much of the east coast is now exceptionally dry. The plant regrowth from La Niña rains has dried out and is, in many places, set to burn. It’s still spring, with a long summer ahead. Where there has been rain, such as in eastern Victoria, it has sometimes coincided with intense bushfire. That gave rise to the extremely unusual situation in early October where residents grappled with fire one day and flood the next.

Put together, it suggests we may be facing a very bad fire season on the east coast and Tasmania. This is, of course, happening against the drumbeat of global warming, and the extra spike in heating this year caused by El Niño.

What’s Happening In Queensland?

This spring has been exceptionally dry across most of the Sunshine State. September and October rainfall in the state’s heavily populated south has been close to the lowest on record and certainly in the bottom 10% of years.

This, in turn, has made many areas ready to burn. While there are fires up and down Queensland, most house losses have been within a few hundred kilometres of Brisbane. The town of Tara and surrounding areas has been worst affected.

How do we know where the fires are? Four times a day, heat-sensing satellites pass over Australia and pinpoint hotspots, where temperatures suddenly jump compared to areas nearby, based on square kilometre tiles. These tell us where the fires are, almost in real time and let us track them as they grow.

To this region, October has brought the third highest number of daytime hotspots seen this century. But it’s the nighttime hotspots that are freakish. Five times more nighttime hotspots than average have been detected compared to previous Octobers.

Why is that so concerning? Think of it from the firefighters’ point of view. If you know that fires usually ease off at night, you can plan around this reprieve – or even get some rest. But this belief will have to change as the nighttime barrier to fire weakens around the world.

Climate change can speed up how fast droughts happen, in what’s been dubbed “flash drought”. It was not so long ago that Australia’s east coast was seemingly underwater, with record-breaking floods. Now drought is back with a vengeance.

Is south-east Queensland seeing more fire than usual? On the whole, yes. And it’s early – one of the earliest seasons since satellite records began in 2001.

So far, most of the serious fires in this area are burning not through grasslands, as is happening in Central Australia, but through open forest and woodlands.

Could we see rainforests in Queensland burn, as we did during the Black Summer? It’s possible, but less likely. But we could see some areas which burned during Black Summer along the east coast burn again, though probably not to the same severity.

There’s certainly enough fuel for some areas on the east coast burned by the 2019–20 bushfires to re-burn, such as New South Wales’ coast and the fringes of the Blue Mountains. That would have serious ecological consequences for areas still in recovery if fires returned before seedlings matured.

Fire Scientists Are Flying Blind

For decades, we’ve known that parts of Australia – the world’s most fire prone continent – would be likely to see more intense and more damaging fires as climate change adds heat and takes away moisture in many regions.

One problem is that we and other professional fire scientists are forced to read the tea leaves from media reports to gauge what’s happening on the ground.

Data on fire progression, fuels and weather are often walled away in government agencies. Firefighters have access, but they are – rightly – focused on the immediate crisis at hand. And insurers have their own data sets on trends in property loss but they are commercially sensitive.

Because there’s no systematic and accessible way to publicise fire data, we end up with a lot of speculation in the media about whether this is a normal or abnormal fire season.

This could be easily fixed with more investment and coordination. Data from geostationary satellites have revolutionised fire spotting, shifting from six-hourly updates to every ten minutes.

These data and historic data, could and should be made easily available to non-specialists, ideally through either the Bureau of Meteorology or a new agency.

Researchers have a role to play in developing tools to help put this flood of data to use.

If we have better public data sets, we can also more quickly shut down talking points from climate deniers, who might claim “there’s nothing new – Queensland has always burned” or use selective statistics to claim the number of dangerous forest fires on Earth is declining. We can’t adapt as a society if we’re arguing whether the fires really are happening or really are this bad.

If we don’t start to adapt to new fire regimes – and fast – we will face a very real crisis. We could soon see insurers stop offering insurance, as some have in California. ![]()

Calum Cunningham, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Tasmania; David Bowman, Professor of Pyrogeography and Fire Science, University of Tasmania, and Grant Williamson, Research Fellow in Environmental Science, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

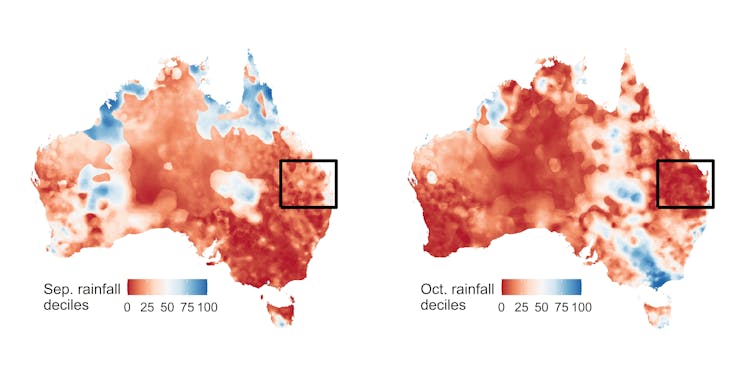

Extreme weather is landing more Australians in hospital – and heat is the biggest culprit

Hospital admissions for injuries directly attributable to extreme weather events – such as heatwaves, bushfires and storms – have increased in Australia over the past decade.

A new report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) shows 9,119 Australians were hospitalised for injuries from extreme weather from 2012-22 and 677 people died from these injuries in the decade up to 2021.

In 2021-22, there were 754 injury hospitalisations directly related to extreme weather, compared to 576 in 2011-12.

Extreme heat is responsible for most weather-related injuries. Exposure to prolonged natural heat can result in physical conditions ranging from mild heat stroke, to organ damage and death.

As Australia heads into summer with an El Niño, it’s important to understand and prepare for the health risks associated with extreme weather.

A Spike Every Three Years

Extreme weather-related hospitalisations have spiked at more than 1,000 cases every three years, with the spikes becoming progressively higher. There were:

- 1,027 injury hospitalisations in 2013–14

- 1,033 in 2016–17

- 1,108 in 2019–20.

In each of these three years, extreme heat had the biggest impact on hospital admissions and deaths.

Extreme heat accounted for 7,104 injury hospitalisations (78% of all injury hospitalisations) and 293 deaths (43% of all injury deaths) in the ten year period analysed.

In 2011-12, there were 354 injury hospitalisations directly related to extreme heat. This rose to 579 by 2021-22.

El Niño And La Niña

Over the past three decades, extreme weather events have increased in frequency and severity.

In Australia, El Niño drives a period of reduced rainfall, warmer temperatures and increased bushfire danger.

La Niña, on the other hand, is associated with above average rainfall, cooler daytime temperatures and increased chance of tropical cyclones and flood events.

Although similar numbers of heatwave-related hospitalisations occurred in El Niño and La Niña years studied, the number of injuries related to bushfires was higher in El Niño years.

During the 2019–20 bushfires, in the week beginning January 5 2020, there were 1,100 more hospitalisations than the previous five-year average, an 11% increase.

Although El Niño hasn’t directly been proved as the cause for these three spikes, according to the Bureau of Meteorology, two of the three years (2016-17 and 2019-20) were El Niño summers. And the other year (2013-14) was the warmest neutral year on record at that time.

Regional Differences

Exposure to excessive natural heat was the most common cause leading to injury hospitalisation for all the mainland states and territories. From 2019 to 2022, there were 2,143 hospital admissions related to extreme heat, including:

- 717 patients from Queensland

- 410 from Victoria

- 348 from NSW

- 267 from South Australia

- 266 from Western Australia

- 73 from the Northern Territory

- 23 from the ACT

- 19 from Tasmania.

The report also includes state and territory data on hospitalisations related to extreme cold and storms.

During the ten-year period analysed, there were 773 injury hospitalisations and 242 deaths related to extreme cold. Extreme rain or storms accounted for 348 injury hospitalisations and 77 deaths.

From 2019 to 2022, there were 191 hospitalisations related to extreme cold, with Victoria recording the highest number (51, compared to 40 in next-placed NSW). During the same period there were 111 hospitalisations related to rain and storms, with 52 occurring in NSW and 28 in Queensland.

What About For Bushfires?

Over the ten-year period studied, there were 894 hospitalisations and 65 deaths related to bushfires.

Bushfire-related injury hospitalisations and deaths peaked in 2019–20, an El Niño year with 174 hospitalisations and 35 deaths. The two most common injuries that result from bushfires are smoke inhalation and burns.

During the 2019–20 bushfires, in the week beginning 5 January 2020 there were 1,100 more respiratory hospitalisations than the previous five-year average, an 11% increase.

The greatest increase in the hospitalisation rate for burns was 30% in the week beginning December 15 2019 — 0.8 per 100,000 persons (about 210 hospitalisations), compared with the previous 5-year average of 0.6 per 100,000 (an average of 155 hospitalisations).

Some People Are Particularly Vulnerable

Anyone can be affected by extreme weather-related injuries but some population groups are more at risk than others. This includes older people, children, people with disabilities, those with pre-existing or chronic health conditions, outdoor workers, and those with greater socioeconomic disadvantage.

People in these groups may have reduced capacity to avoid or reduce the health impacts of extreme weather conditions, for example older people taking medication may be less able to regulate their body temperature. “Thermal inequity” includes people living in poor quality housing who have difficulty accessing adequate heating and cooling.

For heat-related injuries between 2019–20 and 2021–22, people aged 65 and over were the most commonly admitted to hospital, followed by people aged 25–44.

Across age groups, men had higher numbers of heat related injury hospitalisations than women. This difference was most notable among those aged 25-44 and 45-64 years, where over twice as many men were hospitalised due to extreme heat as women.

We Still Don’t Have A Full Picture

The AIHW data only includes injuries which were serious enough for patients to be admitted to hospital; it doesn’t include cases where patients treated in an emergency department and sent home without being admitted.

It includes injuries that were directly attributable to weather-related events but does not include injuries that were indirectly related. For example, it doesn’t include injuries from road traffic accidents that occur due to wet weather, since the primary cause of injury would be recorded as “transport”.

Improved surveillance of weather-related injuries could help the health system and the community better prepare for responding to extreme weather conditions. For example, better data aids communities in predicting what resources will be needed during periods of extreme weather.

A more complete picture of injuries during weather events could also be used to inform people of actions they can take to protect their own health. Given a predicted hot summer, this could be a matter of life or death.

This article was co-authored by Sarah Ahmed and Heather Swanston from the Injuries and System Surveillance Unit at the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.![]()

Amy Peden, NHMRC Research Fellow, School of Population Health & co-founder UNSW Beach Safety Research Group, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We discovered three new species of marsupial. Unfortunately, they’re already extinct

Australia is famous for its diverse and unique marsupials, and infamous for its world-leading rate of mammal extinctions.

In our latest research, we have added new names to the list of Australian marsupials – and at the same time, new entries to the grim catalogue of species driven to extinction since European colonisation.

Our new study, published in Alcheringa, has identified three previously unknown species of small carnivores called mulgaras, which live in the dry country of Australia’s west and north.

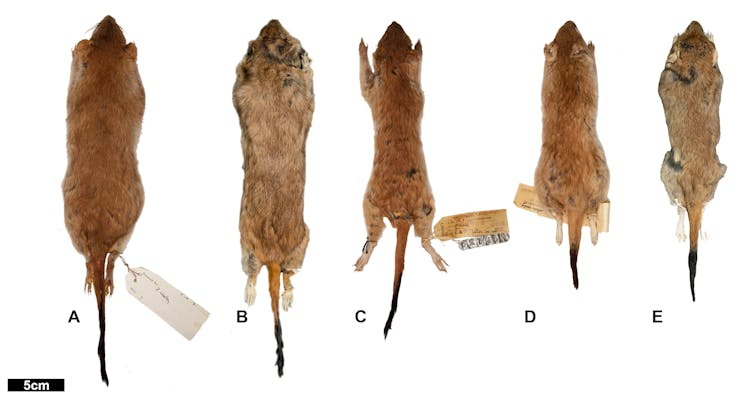

The species were “hiding” in museums, among specimens collected since the 19th century, and none of them survive today.

A Deeper Look At Mulgaras

Mulgaras (Dasycercus) are small, ferocious carnivorous marsupials that are so well adapted to their arid habitats that they do not need to drink water. They play important roles in maintaining the health of their environments by controlling populations of insects and small rodents, and turning over desert soils through foraging.

Until recently, it was thought there were only two species of mulgara, the brush-tailed mulgara (D. blythi) and the crest-tailed mulgara (D. cristicauda).

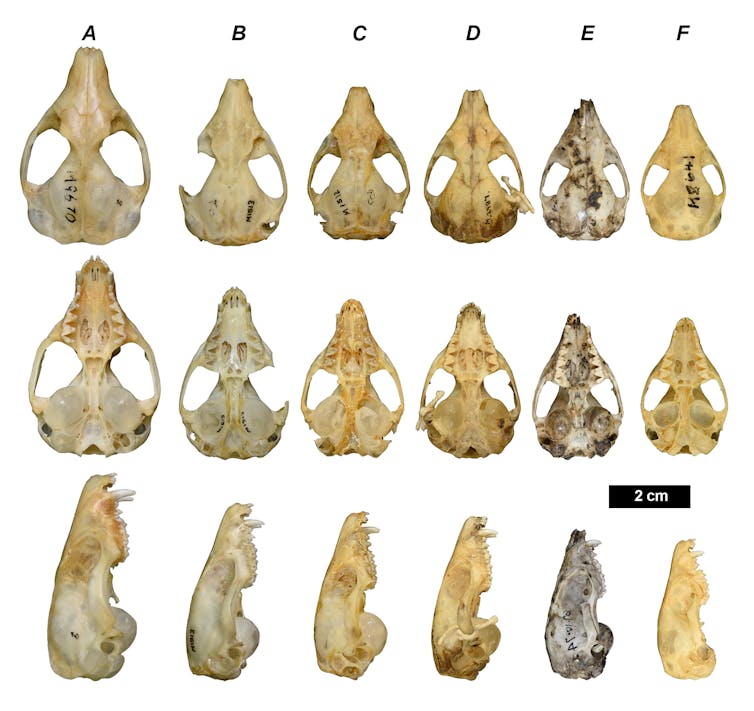

Earlier efforts to classify mulgaras focused on external differences, such as the hair on their tail or the number of nipples. Our new work looked deeper, through an analysis of skulls and teeth.

Mammals use their teeth for many things, most obviously as offensive or defensive weapons, for eating, and for manipulating the environment. If the shape of a species’ teeth changes in some way, this could indicate an adaptation to a change in diet or environment. With enough adaptions and changes, a new species emerges.

In our investigation, we examined “subfossils” – skeletal remains that are not old enough to be true fossils – from sites around Australia where mulgaras are no longer found.

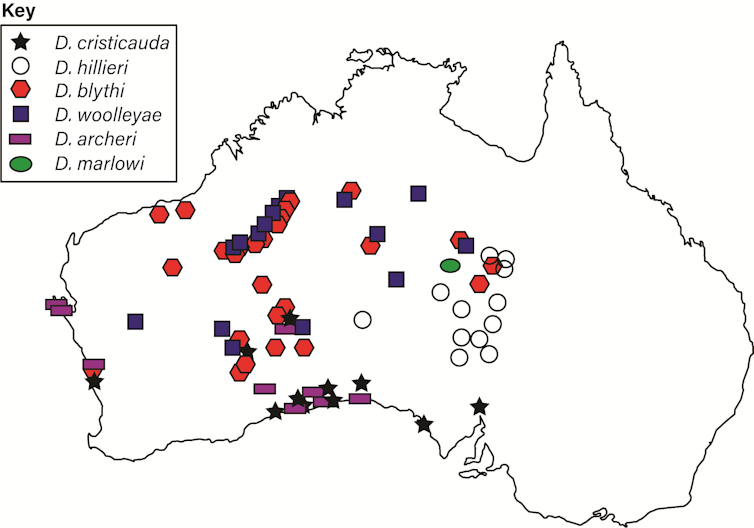

We trawled through animal trapping and subfossil collections made since the 19th century in museums across every mainland state and territory in Australia, and even the Natural History Museum of London. Subfossil specimens from the Nullarbor Plain, the Great Victoria Desert, and the northern Swan Coastal Plain were of particular interest as they had not been attributed to a particular species until now.

We also mounted an expedition to the caves of the Nullarbor Plain to collect additional mulgara skulls.

Not One, Two Or Three Species, But Six

Once we had assembled our collection, we measured the skulls and teeth of the mulgaras to find differences in their overall shape and size. The particular diets and habitats of particular species are expected to leave distinct patterns in their skulls and teeth.

We found differences in the skulls and teeth of mulgaras that completely revised our understanding of their diversity and recent history. Our most remarkable discoveries were found in subfossil deposits that had previously not been classified.

Previously, researchers disagreed about whether there are one, two, or even three species of mulgara. We found a total of six species, living in different habitats across central and western Australia. Two of these were already accepted to exist, another had been proposed in the past but dismissed, and three were entirely new.

We also found that some of the external features previously proposed for identifying species of mulgara were actually shared by multiple species.

For instance, the brush-tailed mulgara (D. blythi) and the crest-tailed mulgara (D. cristicauda) were separated based on the shape of the hairs on the end of their tails. However, it now seems that four of the six mulgara species have crested tails, while the other two have brush tails.

Just as you cannot judge a book by its cover, you cannot judge the importance of a mulgara by its size, or its taxonomy by its tail!

Four Modern Extinctions

Our research is not all good news. Of the six mulgara species, we determined that four are already extinct, likely as a result of the introduction of foxes and cats to Australia.

The extinction of these mulgara species may represent the first extinction in modern Australia within the broader family of Dasyurid marsupials, which also includes quolls and Tasmanian devils.

These newly identified mulgara disappeared with even less recognition than the now infamous extinction of their marsupial relative the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger.

These historical extinctions and lack of awareness exemplify the current ecological crisis facing Australian mammals.

Prior to our research, it was known that mulgaras are threatened and their population and distribution across Australia has decreased.

Our research shows these declines are far greater than we thought. It also shows the importance of using subfossil records to understand the relatively recent history of marsupials for conservation. To protect Australia’s ecosystems, we will need to invest in much broader taxonomic understanding.![]()

Jake Newman-Martin, PhD candidate, Curtin University; Alison Blyth, Senior Lecturer, Curtin University; Kenny Travouillon, Curator of Mammals, Western Australian Museum; Milo Barham, Associate Professor, Earth and Planetary Sciences, Curtin University, and Natalie Warburton, Associate Professor in Anatomy, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We need a single list of all life on Earth – and most taxonomists now agree on how to start

Species lists are one of the unseen pillars of science and society. Lists of species underpin our understanding of the natural world, threatened species management, quarantine, disease control and much else besides.

The people who describe new species and create lists of them are taxonomists. A few years ago, a headline in the journal Nature accused the taxonomic community of anarchy for not coordinating a common view of species, leading to confusion about our knowledge of life on earth.

Many in the taxonomic community took umbrage at this. Taxonomists were concerned that the ideas proposed would limit their freedom of expression and they would be tied to a bureaucracy before they could publish new species descriptions.

Taxonomists certainly argue – disputation is essential to the practice of taxonomy, as it is to science in general. Ultimately, however, a taxonomist’s life is spent trying to discern order in the extraordinarily diverse tree of life.

The results of a new survey published today in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, show just how much taxonomists really do like order.

Hardly A Group Of Anarchists

The argument was about how to solve disagreements between taxonomists. Eventually, the two sides came together to produce principles on the creation of a single authoritative list of species.

This group then went to the taxonomic community to survey their views on whether a global species list is needed and how it should be run.

The newly published results show that a large majority (77%) of respondents – which included over 1,100 taxonomists and users of taxonomy across 74 countries – have expressed support for having a single list of all life on Earth.

They also agreed there should be a governance system that supports the list’s creation and maintenance. Just what that governance system would entail is not yet specified. Deciding that will be the next step in the process.

Taxonomists Propose Hypotheses, Not Facts

Why is this important? Many may not realise that when a taxonomist names a new species description, they are proposing a scientific hypothesis, not presenting an objective scientific fact.

Other taxonomists then look at the evidence provided in the description and decide whether they agree. If people making species lists judge that there is agreement about a hypothesis, the new species goes on their list.

Only after a species is listed can it be protected, studied, eradicated, ignored or whatever else governments decide is appropriate. Scientists and conservation advocates also need species to be listed before they can include them in their work. Until listed, the species remains, for all practical purposes, invisible.

However, not all lists are equally trusted. Very rarely taxonomists do go rogue. One notorious taxonomist has been blacklisted for “taxonomic vandalism”. He published all sorts of new names – some even commemorated his dog – with little justification. If accepted, his field (herpetology) would have been thrown into chaos.

The work of rogue taxonomists wastes everyone’s time and money. In one instance, poor taxonomy has even killed people – an antivenom labelled with the wrong name for a snake was distributed in Africa and Papua New Guinea with disastrous results.

Even without rogue taxonomists, there is an enormous problem with so-called synonyms – different people giving different names for the same species. Some species have tens of scientific names, not to mention misspellings.

This leaves users uncertain what name to use. Sometimes they use different names but mean the same species; sometimes the same names but mean different species. The only way to clarify this confusion is by having a working master list of species names linked to the scientific literature.

Now What?

The newly released survey shows taxonomists and users of taxonomy have achieved an agreement that good lists need good governance. Species lists need to reflect the best science, independent of outside influence. They need dispute resolution processes. And they need involvement and agreement from the taxonomic community on their contents.

Governance of science does not work unless a large majority of scientists agree with the rules, because participation is voluntary. There’s no such thing as science police.

Agreement and compliance is best achieved if scientists themselves are involved in the creation of the rules. This helps to increase buy-in among the community of peers to make sure rules are kept.

Based on the survey results, the Catalogue of Life – the group that has the most comprehensive global species list to date, and the one we’re involved in – is piloting ways of measuring the quality of the lists that make up their catalogue.

These are being trialled first with the creators of lists, everything from viruses to mammals. Then, they will be tested with the taxonomic community at large for further feedback.

Good taxonomy is far more valuable than people realise. One recent study in Australia found that, for every dollar spent on taxonomy, the economy gained A$35. The value of taxonomy globally is likely to be colossal.

But the value will be higher still if everyone the world over is able to use the same list of species.![]()

Stephen Garnett, Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University and Aaron M. Lien, Assistant Professor of Ecology, Management and Restoration of Rangelands, University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Two questions, hundreds of scientists, no easy answers: how small differences in data analysis make huge differences in results

Over the past 20 years or so, there has been growing concern that many results published in scientific journals can’t be reproduced.

Depending on the field of research, studies have found efforts to redo published studies lead to different results in between 23% and 89% of cases.

To understand how different researchers might arrive at different results, we asked hundreds of ecologists and evolutionary biologists to answer two questions by analysing given sets of data. They arrived at a huge range of answers.

Our study has been accepted by BMC Biology as a stage 1 registered report and is currently available as a preprint ahead of peer review for stage 2.

Why Is Reproducibility A Problem?

The causes of problems with reproducibility are common across science. They include an over-reliance on simplistic measures of “statistical significance” rather than nuanced evaluations, the fact journals prefer to publish “exciting” findings, and questionable research practices that make articles more exciting at the expense of transparency and increase the rate of false results in the literature.

Much of the research on reproducibility and ways it can be improved (such as “open science” initiatives) has been slow to spread between different fields of science.

Interest in these ideas has been growing among ecologists, but so far there has been little research evaluating replicability in ecology. One reason for this is the difficulty of disentangling environmental differences from the influence of researchers’ choices.

One way to get at the replicability of ecological research, separate from environmental effects, is to focus on what happens after the data is collected.

Birds And Siblings, Grass And Seedlings

We were inspired by work led by Raphael Silberzahn which asked social scientists to analyse a dataset to determine whether soccer players’ skin tone predicted the number of red cards they received. The study found a wide range of results.

We emulated this approach in ecology and evolutionary biology with an open call to help us answer two research questions:

“To what extent is the growth of nestling blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) influenced by competition with siblings?”

“How does grass cover influence Eucalyptus spp. seedling recruitment?” (“Eucalyptus spp. seedling recruitment” means how many seedlings of trees from the genus Eucalyptus there are.)

Two hundred and forty-six ecologists and evolutionary biologists answered our call. Some worked alone and some in teams, producing 137 written descriptions of their overall answer to the research questions (alongside numeric results). These answers varied substantially for both datasets.

Looking at the effect of grass cover on the number of Eucalyptus seedlings, we had 63 responses. Eighteen described a negative effect (more grass means fewer seedlings), 31 described no effect, six teams described a positive effect (more grass means more seedlings), and eight described a mixed effect (some analyses found positive effects and some found negative effects).

For the effect of sibling competition on blue tit growth, we had 74 responses. Sixty-four teams described a negative effect (more competition means slower growth, though only 37 of these teams thought this negative effect was conclusive), five described no effect, and five described a mixed effect.

What The Results Mean

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we and our coauthors had a range of views on how these results should be interpreted.

We have asked three of our coauthors to comment on what struck them most.

Peter Vesk, who was the source of the Eucalyptus data, said:

Looking at the mean of all the analyses, it makes sense. Grass has essentially a negligible effect on [the number of] eucalypt tree seedlings, compared to the distance from the nearest mother tree. But the range of estimated effects is gobsmacking. It fits with my own experience that lots of small differences in the analysis workflow can add to large variation [in results].

Simon Griffith collected the blue tit data more than 20 years ago, and it was not previously analysed due to the complexity of decisions about the right analytical pathway. He said:

This study demonstrates that there isn’t one answer from any set of data. There are a wide range of different outcomes and understanding the underlying biology needs to account for that diversity.

Meta-researcher Fiona Fidler, who studies research itself, said:

The point of these studies isn’t to scare people or to create a crisis. It is to help build our understanding of heterogeneity and what it means for the practice of science. Through metaresearch projects like this we can develop better intuitions about uncertainty and make better calibrated conclusions from our research.

What Should We Do About It?

In our view, the results suggest three courses of action for researchers, publishers, funders and the broader science community.

First, we should avoid treating published research as fact. A single scientific article is just one piece of evidence, existing in a broader context of limitations and biases.

The push for “novel” science means studying something that has already been investigated is discouraged, and consequently we inflate the value of individual studies. We need to take a step back and consider each article in context, rather than treating them as the final word on the matter.

Second, we should conduct more analyses per article and report all of them. If research depends on what analytic choices are made, it makes sense to present multiple analyses to build a fuller picture of the result.

And third, each study should include a description of how the results depend on data analysis decision. Research publications tend to focus on discussing the ecological implications of their findings, but they should also talk about how different analysis choices influenced the results, and what that means for interpreting the findings.![]()

Hannah Fraser, Postdoctoral Researcher , The University of Melbourne; Elliot Gould, PhD student, School of Biosciences, The University of Melbourne, and Timothy H. Parker, Professor of Biology and Environmental Studies, Whitman College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Storms or sea-level rise – what really causes beach erosion?

Beaches are dynamic. They change from week to week and month to month. Have you ever wondered what causes these changes? Or how beaches might fare as sea levels rise and if storms increase in frequency and severity?

To help answer these questions, we studied 50 years of change at Bengello Beach, near the Moruya airport on the New South Wales south coast. This is a typical beach with moderate waves and no hard infrastructure such as sea walls or houses built over dunes. The results therefore represent natural beach change over half a century. This helps us understand the natural behaviour of beaches around the world.

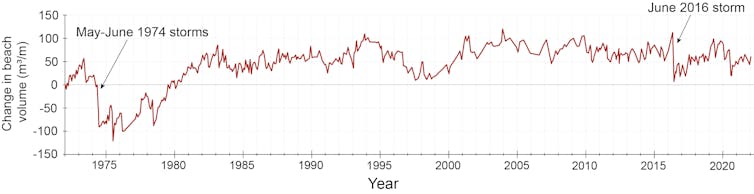

We found the main driver of coastal erosion is frequent storms of moderate intensity. These storms remove sand from the beach. This sand is generally returned within a matter of months. But what about more extreme events?

In the 50 years of monitoring, offshore wave buoys recorded 21 storms where maximum waves heights exceeded ten metres. That’s roughly equivalent to the height of a three-story building. These larger events cause even greater erosion, so the beach takes longer to recover.

The ‘Biggest Of The Big’ Storms

Some of the largest events in the record have been particularly destructive, for example the storm in June 2016 where a residential swimming pool washed onto the beach at Narrabeen-Collaroy. Or the June 2007 event when the Pasha Bulka container ship broke its mooring and washed up on Nobbys Beach in Newcastle. Both storms also caused substantial beach erosion at Bengello.

One sequence of storms stands out in the record. The successive storm events of May–June 1974 including the renowned Sygna Storm of May 1974. During these two months, more than a B-double truck full of sand was cut away at every metre strip of beach (95 cubic metres of sand per metre of beach), and the shoreline moved inland farther than the length of an Olympic swimming pool (63m).

Astonishingly, it took five and half years for the beach to recover to its previous condition after these events. The recovery was hampered by more severe storms in 1976 and 1978, which interrupted the gradual build-up of beach sand.

No other storms in the record have had such a huge impact on the beach. Importantly, this is our only quantitative record of this event because it occurred before satellite imagery was available. Therefore it is not captured by tools such as CoastSat and Digital Earth Australia Coastlines, which derive shoreline positions from more than 30 years of satellite images, and have proved so powerful in understanding recent shoreline changes.

But how often do the biggest storms occur? Looking into the past, research suggests an erosion event of this magnitude has occurred at least one other time in the past 500 years.

Can Beaches Survive Future Sea-Level Rise?

So how will beaches fare in a warming world where sea-level rise accelerates and coastal storms intensify?

This beach has sufficient sand to enable recovery after extreme storm events such as those experienced in the La Niña period of 1974–78. This degree of recovery is related to each beach’s so-called “sand budget”.

Recent research has even suggested extreme storms can replenish beaches with more sand from deeper waters.

Under present-day conditions this beach appears to have the capacity to fully recover. This means that it and other similar beaches with positive sand budgets can absorb certain levels of sea-level rise – but only up to a point. There will be a threshold beyond which a beach starts to retreat unless a new source of sand is supplied.

Sources of beach sand could come from deeper water offshore or from neighbouring beaches alongshore. These “credits” of sand into the beach budget may help them maintain their current position. Other NSW beaches in credit include the northern end of Seven Mile Beach near Gerroa, Nine Mile Beach north of Tuncurry and Dark Point just north of Hawks Nest. Around Australia, we can use time-series of shoreline change to estimate beach sand budgets.

Beaches in sand “defecit” are more vulnerable to sea level rise. Examples include the southern end of Stockton Beach and Old Bar in NSW and the northern end of Bribie Island in Queensland.

In a dynamic and volatile future, it is more important than ever that we maintain long-term records of beach change. This will ensure we have a critical baseline of data to test future projections. Monthly surveys at the site are continuing.![]()

Thomas Oliver, Senior lecturer, UNSW Canberra, Australian Defence Force Academy; Bruce Thom, Emeritus Professor, University of Sydney, and Roger McLean, Emeritus Professor, UNSW Canberra, Australian Defence Force Academy

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Extreme weather is outpacing even the worst-case scenarios of our forecasting models

Ravindra Jayaratne, University of East LondonIn the wake of the destructive Hurricane Otis, we find ourselves at a pivotal moment in the history of weather forecasting. The hurricane roared ashore with 165mph winds and torrential rainfall, slamming into the coastal city of Acapulco, Mexico and claiming the lives of at least 48 people.

The speed at which Otis intensified was unprecedented. Within 12 hours it went from a regular tropical storm to a “category 5” hurricane, the most powerful category and one which might occur only a few times worldwide each year.

This rare and alarming event, described by the US National Hurricane Center as a “nightmare scenario”, broke records for the fastest intensification rate over a 12-hour period in the eastern Pacific. Otis not only caught residents and authorities off guard but also exposed the limitations of our current predictive tools.

I specialise in the study of natural disasters with the goal of improving our ability to predict them and ultimately to save lives. It is critical that we address the pressing concerns related to the tools we use for forecasting these catastrophic events, all while recognising the significant influence of rapid climate change on our forecasting capabilities.

The Predictive Tools We Rely On

At the core of weather forecasting are computer programs, or “models”, that blend atmospheric variables such as temperature, humidity, wind and pressure, with fundamental physics.

Since the atmospheric processes are nonlinear, a small degree of uncertainty in initial atmospheric conditions can lead to a large discrepancy in final forecasts. That’s why the general practice now is to forecast a set of possible scenarios rather than predict the single scenario most likely to occur.

But while these models are instrumental in issuing early warnings and evacuation orders, they have fundamental limitations and carry a significant degree of uncertainty, especially when dealing with rare or extreme weather. This uncertainty arises from various factors including the fundamentally chaotic nature of the system.

First, the historical data is incomplete, since a hurricane such as Otis might occur only once in several millennia. We don’t know when an east Pacific storm last turned into a category 5 hurricane overnight – if ever – but it was certainly before modern satellites and weather buoys. Our models struggle to account for these “one in 1,000-year events” because we simply haven’t observed them before.

The complex physics governing the weather also has to be simplified in these predictive models. While this approach is effective for common scenarios, it falls short when dealing with the intricacies of extreme events that involve rare combinations of variables and factors.

And then there are the unknown unknowns: factors our models cannot account for because we are unaware of them, or they have not been integrated into our predictive frameworks. Unanticipated interactions among various climatic drivers can lead to unprecedented intensification, as was the case with Hurricane Otis.

The Role Of Climate Change

To all this we can add the problem of climate change and its impact on extreme weather. Hurricanes, in particular, are influenced by rising sea surface temperatures, which provides more energy for storms to form and intensify.

The connection between climate change and the intensification of hurricanes, coupled with other factors such as high precipitation or high tides, is becoming clearer.

With established weather patterns being altered, it is becoming even more challenging to predict the behaviour of storms and their intensification. Historical data may no longer serve as a reliable guide.

The Way Forward

The challenges are formidable but not insurmountable. There are a few steps we can take to enhance our forecasting and better prepare for the uncertainties that lie ahead.

The first would be to develop more advanced predictive models that integrate a broader range of factors and variables, as well as consider worst-case scenarios. Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools can help us process vast and complex datasets more efficiently.

But to get this additional data we’ll have to invest in more weather monitoring stations, satellite technology, AI tools and atmospheric and oceanographic research.

Since even world experts and their models can be caught out by sudden weather extremes, we also need to educate the public about the limitations and uncertainties in weather forecasting.

We must encourage preparedness and a proactive response to warnings, even when predictions seem uncertain. And of course we still have to mitigate climate change itself: the root cause of intensifying weather events.

Hurricane Otis provided a stark and immediate reminder of the inadequacies of our current predictive tools in the face of rapid climate change and increasingly extreme weather events. The urgency to adapt and innovate in the realm of weather forecasting has never been greater.

It is incumbent upon us to rise to the occasion and usher in a new era of prediction that can keep pace with the ever-shifting dynamics of our planet’s climate. Our future depends on it.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Ravindra Jayaratne, Reader in Coastal Engineering, University of East London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

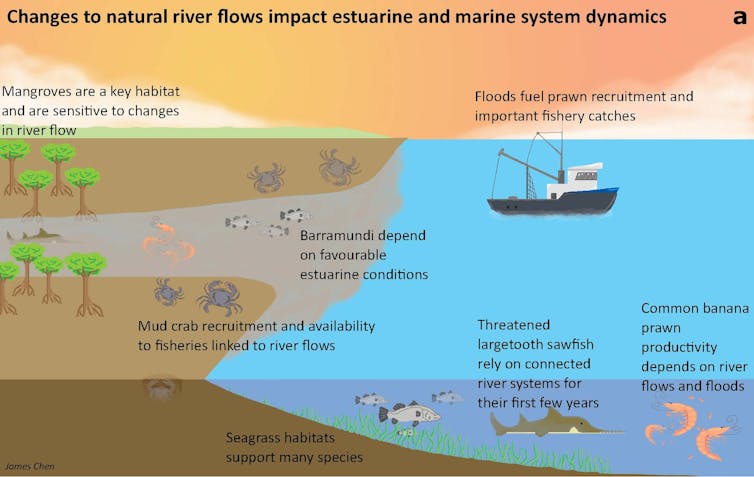

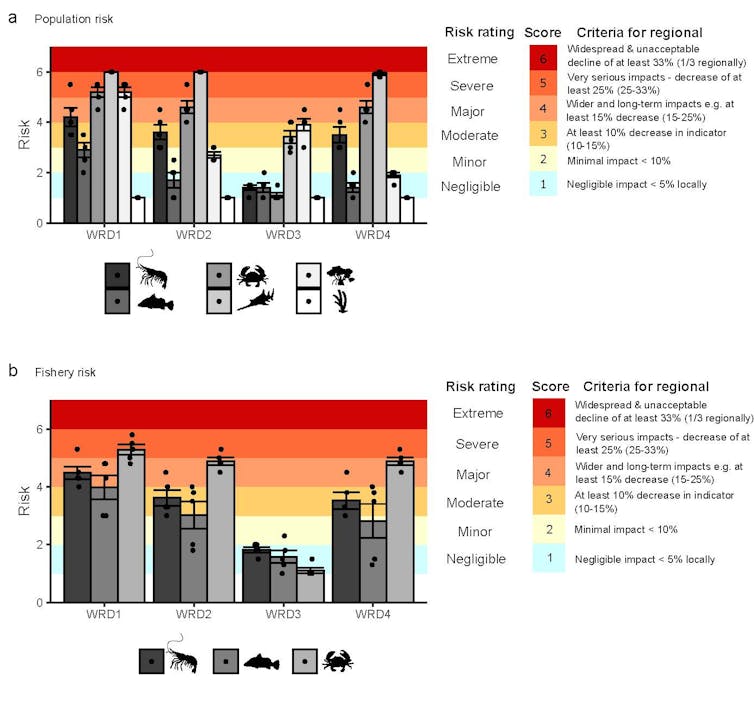

Taming wild northern rivers could harm marine fisheries and threaten endangered sawfish

Australia’s tropical northern rivers still run wild and free. These relatively pristine areas have so far avoided extensive development. But this might not last. There are ongoing scoping studies exploring irrigating agricultural land using water from these rivers.

Our new research in the journal Nature Sustainability shows disturbing the delicate water balance upstream can have major consequences downstream, even hundreds of kilometres away.

Using our latest computer modelling, we found northern water resource development would have substantial effects on prawn, mud crab and barramundi fisheries in the Gulf of Carpentaria. These are valuable Australian marine fisheries which depend on healthy estuaries. Reducing river flows would also disturb mangrove and seagrass habitats and threaten the iconic endangered largetooth sawfish.

Freshwater flows to the sea play a crucial role, boosting the productivity of marine, estuarine and freshwater systems. These complex interactions must be carefully considered in the assessment of future development plans.

Rivers Are Our Lifeblood

Worldwide, few wild running rivers remain. Their future is uncertain given growing demand for water.

Climate change is putting extra pressure on rivers as temperatures rise, rainfall patterns shift and extreme events become more frequent.

Rivers are the lifeblood of ecosystems and communities. They connect land, estuaries and the sea. But assessments of river developments often focus narrowly on local effects. They ignore the fact downstream estuaries and marine systems depend on freshwater flows. Few studies have calculated the costs of upstream catchment developments to downstream estuarine and marine ecosystems and fisheries.

We must avoid the mistakes made in southern Australia where too much water has been taken out of the system for growing crops. That means carefully evaluating the design of dams or irrigation schemes, considering when, where and how much water should be taken – and the likely trade-offs.

Why Should We Care About Northern Rivers?

Australia’s remote northern rivers are one of the last strongholds for endangered species such as the largetooth sawfish. These iconic species are born in estuaries before spending their first few years of life upstream in freshwater rivers.

Flows from these rivers also sustain extensive mangrove forests and seagrass beds. Periodic floods boost the food supply for many prized marine fisheries such as prawns, barramundi and mud crabs.

The rivers also have cultural significance for Aboriginal people and represent a valuable resource, providing food and supporting livelihoods.

Using Modelling To Connect Rivers, Estuaries And Oceans

We coupled CSIRO’s sophisticated river models with our specially tailored ecosystem models to represent how altering river flows may influence the downstream ecology and fishery yields.

We used catch data from fisheries to analyse how past natural changes in flow influenced catch rates. This was combined with extensive previous research on the biology and ecology of each species to model the dynamics of catchment-to-coast systems. We were particularly interested in the natural life cycles of fish and crustaceans in our unique northern wet-dry tropical rivers and estuaries. We then simulated multiple water resource development scenarios to assess and compare various impacts and ways to reduce them.

For mud crabs, we linked river flow and other climate drivers to their life cycle and were able to show how past changes in flow could explain the past variation in crab catch, particularly for rivers in which flow was seasonally variable. We could then use this model to predict how crab catch and abundance might change in the future, depending on how much water is removed from rivers and the method of removal.

Integrated Management From Catchment To Coast

Our research shows freshwater flows to the sea are crucial for environmentally and economically important species. Any plan to dam or extract freshwater from Australia’s last wild rivers should account for these effects.

Coupling scientific knowledge about marine and freshwater ecosystems with catchment development will improve infrastructure planning and flow management.

This is vital on a dry continent already challenged by climate change. Every drop counts.

The authors wish to acknowledge Annie Jarrett, Chief Executive Officer of NPF Industry Pty Ltd, which represents Northern Prawn Fishery operators, for her contribution to the research.![]()

Éva Plagányi, Senior Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO; Laura Blamey, Senior Research Scientist, CSIRO; Michele Burford, Professor - Australian Rivers Institute, and Dean - Research Infrastructure, Griffith University, and Robert Kenyon, Marine Ecologist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In the 1800s, colonial settlers moved Ballarat’s Yarrowee River. The impacts are still felt today

David Waldron, Federation University Australia; Kelly Ann Blake, Indigenous Knowledge, and Shannen Mennen, Indigenous KnowledgeThe discovery of gold in Ballarat in 1851 transformed its landscape to a staggering degree. Within days, and despite the news being initially suppressed, hundreds of men had gathered along the Yarrowee River.

They sluiced the clay and soil, turning the once pristine waters into what writer William Bramwell Withers described as

liquid, yellow as the yellowest Tiber flood, and its banks grew to be long shoals of tailings.

Over the next few weeks, the waterways of the Yarrowee River and of Gnarr Creek were diverted into water courses to support the search for gold.

The river was moved to make way for the town population boom, which was driven by a lust for gold. The end result was that the original, serpentine path of the river – originally across floodplains equipped to handle the natural ebb and flow of water and seasonal flooding – eventually came to be a much straighter line. Part of the river now runs underground through a tunnel.

Our new interactive map, Yarrowee River History: Peel to Prest (which takes its name from the two streets that serve as borders for the mapping), interrogates the long-term effects of this water diversion on community and Country.

A collaboration between Federation University, the Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and the city of Ballarat, our project overlays historical maps with Google Maps to illustrate how the area changed.

‘We Inherit The Scars Of This Trauma’

In Ballarat, water is deeply significant to the culture of the area’s First Nations inhabitants, the Wadawurrung people, who stewarded these lands and waterways for millennia.

So we wanted people using our interactive map to ponder the cultural significance of these gold rush impacts to the Wadawurrung people and the environment.

For the Wadawurrung people, the watercourse now known as the Yarrowee River carries profound historical meaning.

This river bore the names Yaramlok and Narmbool, and these names were used interchangeably to reference different segments of the Yarrowee.

The river wasn’t merely a physical entity – it was a symbol of spiritual and cultural significance, the life force which flows through Country.

It supported fishing, agriculture and food gathering. It symbolised the deep and harmonious connection with dja (Country) and the precious resource of ngubitj (water).

The river diversion affected the Wadawurrung profoundly. As two of us (Shannen Mennen and Kelly Ann Blake) write on the Yarrowee River History: Peel to Prest site:

Colonisation and mining in Ballarat led to devastation and destruction of Wadawurrung dja, including the Yarrowee River. Settlement was built upon our living spaces and as a result Wadawurrung people were displaced.

The withholding of cultural rights and obligations further increased the dispossession of our people, who were unforgivingly forced to adapt to change. Still today we inherit the scars of this trauma.

Colonial settlers altered the river

in a way which excluded the knowledge Wadawurrung people had built upon for many thousands of years […] The habitat surrounding the Yarrowee was removed or altered, damaging animal, fish and insect populations.