inbox and environment news: Issue 605

November 12 - 18, 2023: Issue 605

Collaroy Beach Coastal Works: Have Your Say - Closes December 3

- completing the submission form here

- emailing council@northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au

- writing to council at Northern Beaches Council, PO Box 82 Manly NSW 1655.

November Colours: Angophora Costata, Jacaranda, Spotted Gums; Trees In Your Streets - Pittwater

Angophora - from two Greek words, meaning 'vessel' or 'goblet', and 'to bear or carry', referring to the shape of the fruits; costata - ribbed; the capsules bear prominent ribs.

The genus Angophora is closely allied to Corymbia and Eucalyptus (family Myrtaceae) but differs in that it usually has opposite leaves and possesses overlapping, pointed calyx lobes instead of the operculum or lid on the flower buds found in those genera.

Angophora costata, or Smooth-barked Apple, is a large, wide, spreading tree growing to a height of between 15 and 25 m. The trunk is often gnarled and crooked with a pink to pale grey, sometimes rusty-stained bark. The timber is rather brittle. In nature the butts of fallen limbs form callused bumps on the trunk and add to the gnarled appearance. The old bark is shed in spring in large flakes with the new salmon-pink bark turning to pale grey before the next shedding. The leaves are dark green, lance-shaped, 6-16 cm long and 2-3 cm wide. They are borne opposite each other on the stem.

The flowers are white and very showy, being produced in large bunches on terminal corymbs or short panicles. The individual flowers are about 2 cm wide with five tooth-like sepals, five larger semi-circular petals, and a large number of long stamens. The seed capsules are goblet shaped, 2 cm long and as wide, often with fairly prominent ribs. The usual recorded flowering time is December or January, but here in Pittwater they are out by early November, while at the Australian National Botanic Gardens in Canberra the species flowers for about one month between early January and early February.

Photos; taken in Pittwater, Friday November 10, 2023:

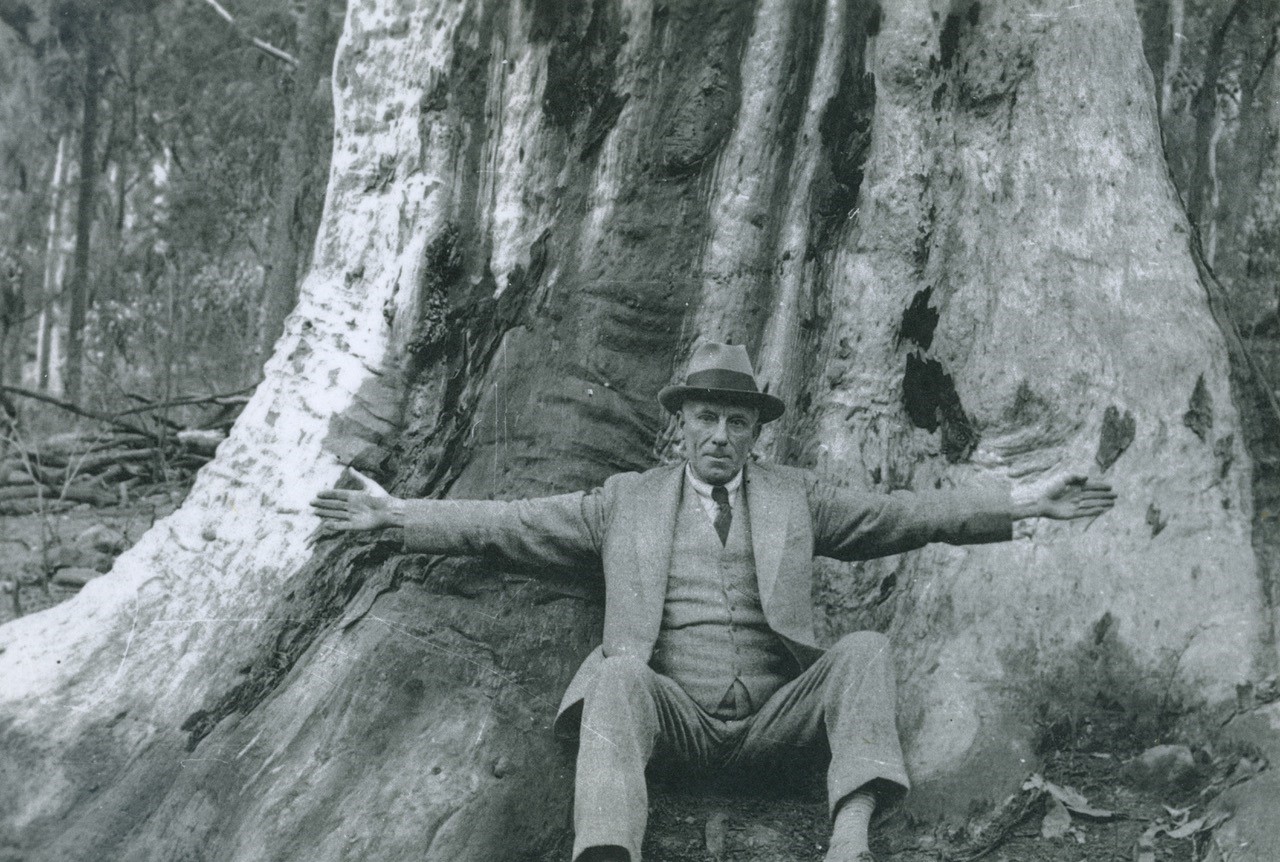

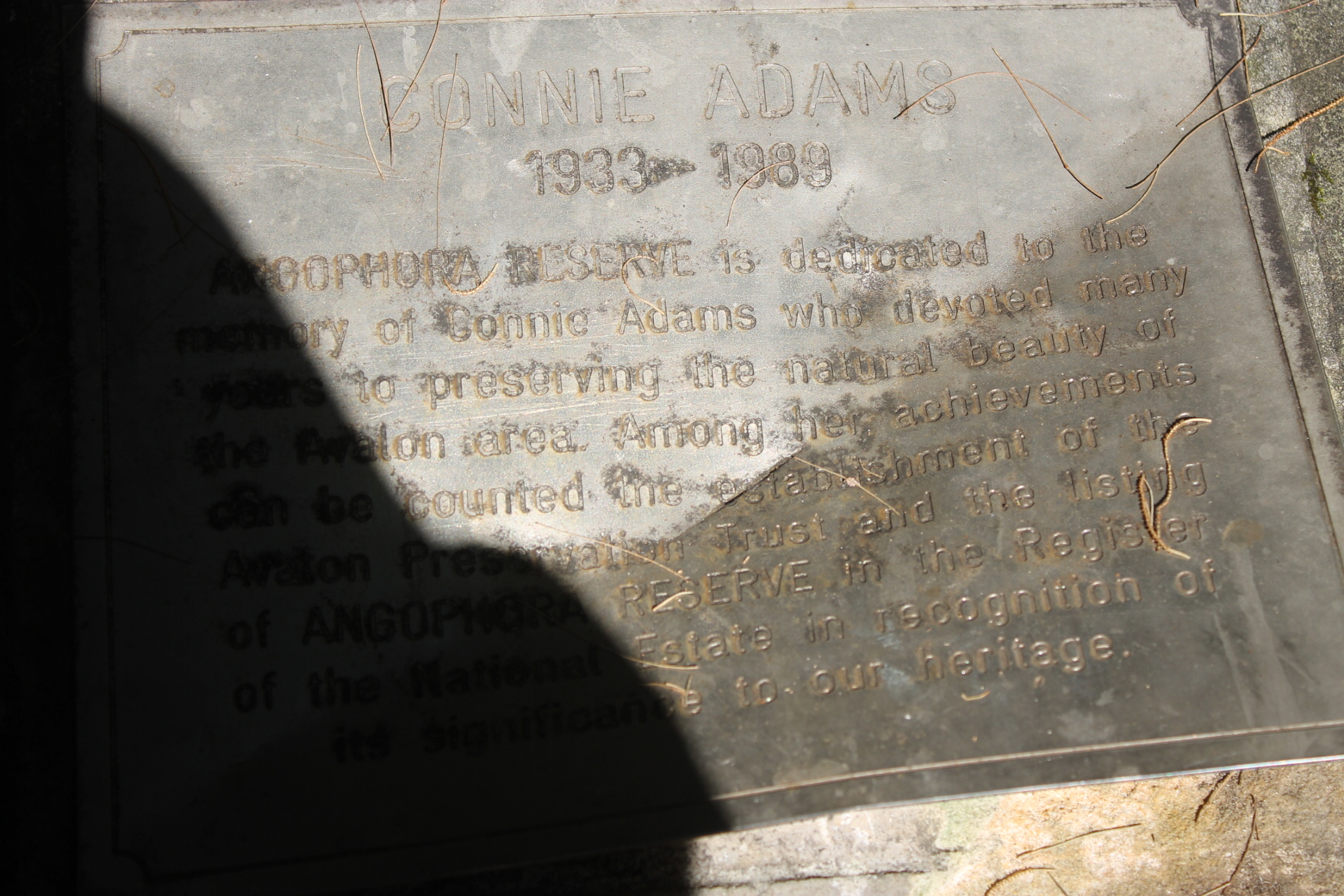

This photo shows the official opening of the Angophora Reserve on 19 March 1938 by Sir Phillip Street (KCMG). Much of the groundwork to enable the purchase of the land by the Wildlife Preservation Society in January 1937 was done by Thistle Harris. The reserve cost the Society 364 pounds 19 shillings and 7 pence (which converts to around 730 dollars!). The volunteer bush care group meet on the 3rd Sunday of each month usually at the Palmgrove Road entrance. – Geoff Searl, President of the Avalon Beach Historical Society - photo courtesy ABHS More In 'Grand Old Tree Of Angophora Reserve Falls Back To The Earth'

Arthur Jabez Small and the Old Girl, pre-1954 - photo courtesy ABHS - Geoff Searl OAM

Also Flowering Now - Jacaranda

How did they get here?

The story is that Allan Cunningham a roving British botanist, with a penchant for rare and exotic plants, was so transfixed by the stunning jacarandas when he first saw them in bloom in Rio de Janeiro sometime in 1818, that he brought a specimen back to London, for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. The harsh Northern Hemisphere winters meant that jacarandas could only survive within hothouses. A far milder climate, closer to its Brazilian home, was what this delicate tree really craved. So, when Cunningham was briefly appointed the colonial botanist of NSW, it’s believed he was the first person to successfully plant a jacaranda in Sydney.

Cunningham, along with many European plant-experts familiar with the jacaranda, had believed the plant to be especially difficult to grow. Cuttings would rarely flourish and more attempts to propagate the tree failed than succeeded. Gardeners would go to extraordinary lengths to get jacarandas to thrive – one of the most trusted methods, devised in 1886 by noted landscape designer Michael Guilfoyle, horticulturalist and owner of Guilfoyle’s Exotic Nursery at Double Bay, required elaborate rigs of bell jars, specially constructed ‘cold pits’ and baths of precisely warmed water. For these reasons, the handful that did manage to mature were considered the most precious and rare of trees. The Sydney Morning Herald noted in 1868 that the jacaranda planted in the Royal Botanic Gardens (which you can still visit today) “is well worth a journey of 50 miles or more to see. Its beautiful, rich lavender blossoms and its light, feathery foliage render it the gem of the season.”

However, like many species of Bignonia, while the jacaranda is incredibly difficult to grow from a cutting it propagates with ease when its freshly released seeds find just the right conditions – such as those found across Sydney in the Spring. Being a Southern Hemisphere city on nearly the same latitude as Rio, the first jacarandas to grow in Sydney felt right at home, and the descendants of that handful of original trees now flourish throughout Sydney in their hundreds. By the 1930s, the trees were so plentiful, people happily accepted that these beautiful blooms must have always been here, dusting the ground with petals, filling the spring air with scent.

In 1952, Sister Irene Haxton began giving out a jacaranda seedling to every new baby born at her hospital at Jacaranda Maternity Hospital in Woolooware. Now, every October and November, the streets of St George and Sutherland Shire are awash with purple blooms.

Photos taken November 7 and 10, 2023 in Pittwater!

Spotted Gums Changing Colours

Corymbia maculata, commonly known as Spotted Gum, is a species of medium-sized to tall tree that is endemic to eastern Australia. It has smooth, mottled bark, lance-shaped to curved adult leaves, flower buds usually in groups of three, white flowers and urn-shaped or barrel-shaped fruit.

Flowering occurs from March to September and the flowers are white. The fruit is a woody oval, barrel-shaped or slightly urn-shaped capsule 9–14 mm (0.35–0.55 in) long and 8–13 mm (0.31–0.51 in) wide with the valves enclosed in the fruit.

These trees replace their bark seasonally, but not all at once. Instead, bits of the bark are shed and new bark grows at different rates. That leaves the famous spots on their trunks (maculatus is Latin for spotted).Early in the growing season some of these spots can be a bright green before fading to tans and greys over the coming months. Many patterns can be stunningly beautiful. This bark shedding is called “decorticating” and is a normal thing.

The Pittwater and Wagstaffe Spotted Gum Forest in the Sydney Basin Bioregion is listed as an Endangered Ecological Community in NSW.

Occurs entirely within the Pittwater Local Government Area, on the Barrenjoey Peninsula and Western Pittwater Foreshores. Remnants are typically small and on private property, however there are a few remnants in Council reserves and one remnant within Ku-ring-gai Chase NP.

Threats

- Habitat loss and degradation due to urban development including encroachment.

- Encroachment from urban areas including illegal and legal tree and understorey removal, planting of exotic species and weed invasion.

- Inappropriate fire regime being a combination of lack of fire and too frequent fires due to arson and hazard reduction burns.

- Stormwater and soil erosion.

- Disturbance from recreational users, including unauthorised visitor access; rubbish dumping, illegal trails, illegal mountain bike tracks, and walkers.

- Introducing and spreading of disease including phytophthora and myrtle rust.

- Weed invasion, including multiple asparagus species, mickey mouse weed, bitou, privet, crofton weed, lantana, mixed woody weeds and garden escapes.

- Lack of knowledge about extent, composition and condition beyond the areas mapped.

Activities to assist this species and community

- Remove rubbish.

- Control stormwater and soil erosion.

- Introduce measures to control unrestricted access and/or inappropriate use.

- Manage weed infestations.

- Protect areas of habitat from clearing and further fragmentation.

- Restore degraded habitat using bush regeneration techniques.

Photos taken November 7, 2023 in Pittwater!

Careel Creek Birds: Pacific Black Duck, Royal Spoonbill

Pacific black duck: A protector Songline that runs through Pittwater

The Pacific black duck (Anas superciliosa) is a dabbling duck found in much of Australia.

The Black Duck Songline, as current Aboriginal knowledge holders confirm, travels up the South Coast from over the Victorian border to the Hawkesbury River, north of Sydney, passing through not only Pittwater but also many important cultural locations of the Yuin and Dharawal peoples of the region.

A songline is not just a map across Country. It is a celebration of the stories which make up the songline, and these stories are encompassed in the form of song. The melody stays consistent as a songline passes through different language groups and dialects along the route.

A songline is never extinguished, although the Country through which it passes may be dying because it is not being sung. This has given rise to the Aboriginal expression to “sing up Country”: refreshing the songs and the Country to which the songs belong.

The Pacific Black Duck (Anas superciliosa), is known as Umbarra to the Yuin and Wumbarra to the Dharawal. The Yuin story of Umbarra comes from Wallaga Lake near Narooma on the NSW far south coast. Umbarra is an animal hero, rather than a Creator, and is the totem and protector of the Yuin peoples from the Dreaming.

A Yuin man, Merriman, had Umbarra as his totem. When his people were in danger, Umbarra warned them so they could take refuge on what is now called Merriman’s Island in Wallaga Lake.

Umbarra became the Yuin protector, and, through kinship linkages, the bird is equally important to the Dharawal.

The Pacific black duck is mainly vegetarian, feeding on seeds of aquatic plants. This diet is supplemented with small crustaceans, molluscs and aquatic insects. Food is obtained by 'dabbling', where the bird plunges its head and neck underwater and upends, raising its rear end vertically out of the water. Occasionally, food is sought on land in damp grassy areas.

The nest is usually placed in a hole in a tree, but sometimes an old nest of a corvid is used and occasionally the nest will be placed on the ground. The clutch of 8–10 pale cream eggs is incubated only by the female. The eggs hatch after 26–32 days. The precocial downy ducklings leave the nest site when dry and are cared for by the female. They can fly when around 58 days of age.

mum with bubs

Photos; Pacific Black Duck mum and bubs + others - taken at Careel Creek, Pittwater, Friday November 10 2023. Pics: AJG/PON

Royal Spoonbill

The Royal Spoonbill (Platalea regia) also known as the black-billed spoonbill, occurs in intertidal flats and shallows of fresh and saltwater wetlands in Australia. The renowned ornithologist John Gould first described the royal spoonbill in 1838, naming it Platalea regia and noting its similarity to the Eurasian spoonbill (P. leucorodia). A 2010 study of mitochondrial DNA of the spoonbills by Chesser and colleagues found that the royal and black-faced spoonbills were each other's closest relatives.

The royal spoonbill is a large, white bird with a black, spoon-shaped bill. It is approximately 80 cm (31 in) tall, 74–81 cm (29–32 in) and a weight of 1.4–2.07 kg (3.1–4.6 lb). It is a wading bird and has long legs for walking through water. It eats fish, shellfish, crabs and amphibians, catching its prey by making a side-to-side movement with its bill.

Spoonbills form monogamous pairs during the breeding season, which extends from October to March. When they are breeding, long white plumes grow from the back of their heads and coloured patches appear on the face. The nest is an open platform of sticks in a tree in which the female lays two or three eggs. The chicks hatch after 21 days. The birds are highly sensitive to disturbance in the breeding season. In Australia, whole colonies have been known to desert their eggs after a minor upset.

Photos taken at Careel Creek, Friday November 10, 2023. Pics: AJG/PON

Shearwaters On Our Beaches: Is Monster Eddy Current Off The Coast Of Sydney May Be To Blame?

- Birdlife Australia says "wreck" events are "confronting", but not unusual

- It is suspected that stormy weather or an ocean warming event may have caused the deaths

- Some birds are being euthanised and others are being moved to safe places to recuperate

Beach-Washed Birds Now On Birdata

EPA Extends Stop Work Order In Tallaganda State Forest: Forestry Corporation Of NSW (FCNSW) Set To Kill Greater Glider Den Trees

_in_a_Eucalypt.jpg?timestamp=1699636297844)

Next Steps To Beat Plastic Pollution In NSW: Have Your Say

- Are frequently littered or release microplastics into the environment;

- Contain harmful chemical additives; or

- Are regulated or proposed to be in other states and territories.

- Items containing plastic such as lollipop sticks, cigarette butts, bread tags and heavyweight plastic shopping bags are some of the problematic products that could be redesigned or phased out.

EPA Publishes Results Of Investigation Into Metals In Cadia Water Tanks

Why are dead and dying seabirds washing up on our beaches in their hundreds?

In October and November, horrified beachgoers often find dead and dying muttonbirds washing up in an event called a seabird “wreck”.

Again this year, there are reports of Australia’s beautiful east coast beaches turned grim with hundreds of dying seabirds.

Here’s what we do and don’t know about seabird wrecks, and what you can do if you come across one.

Wrecks Are Becoming More Common

Millions of short-tailed shearwaters (Ardenna tenuirostis), commonly known as muttonbirds, return to southern Australia from the Arctic each spring – a round trip of up to 35,000km.

Not all birds survive their long migration. The fit and healthy largely return in late September and October. The less fit lag behind. To some extent, deaths are natural.

Muttonbirds keep a strict timetable and, while failed migrants can wash up any time during spring, mass mortalities can occur from mid-October to November. Muttonbird wrecks have happened on rare occasions since time immemorial, but are becoming more common.

The many ideas about what is causing wrecks range from storms and overfishing to plastic, blue-green algae and irradiated water from Fukushima.

University of Tasmania researchers have studied the muttonbirds for decades. While we can’t pinpoint the exact cause for every wreck, we can explain what we know and eliminate the unlikely culprits.

What We Know

When muttonbird wrecks occur, the casualties are starving. These birds weigh only half their healthy body weight. The factors leading to this starvation start before they reach Australia.

Muttonbirds chase an eternal summer. After returning to Australia from the North Pacific, they lay eggs in late November on Australia’s southern islands and raise a single chick. When the weather cools in April the adults depart on a great migration north where the sea ice is melting on the Bering Sea ahead of an Arctic summer.

Ecosystem changes in the sub-Arctic, where the birds fatten up over the northern summer, can lead to death on Australian beaches.

Many marine animals share the North Pacific Ocean with muttonbirds. Among them are several salmon species, which compete with muttonbirds and other marine wildlife for the same zooplankton prey – the abundant small animals floating in the surface waters of the ocean.

The pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), in particular, is central to the muttonbirds story. You may have seen them in documentaries, being eaten by bears on the annual “salmon run”. You may also eat them yourself, as tinned salmon.

Pink salmon live hard and fast. Their life cycle from hatching to spawning lasts two years. However, wild numbers couldn’t satisfy consumer demand and by the mid-20th century the species was in trouble.

To take pressure off wild fish stock and meet soaring demand, salmon hatcheries now release billions of fry, many more than would exist through nature, into the North Pacific Ocean. Pink salmon numbers, both hatchery and wild fish, have more than doubled in recent decades.

Increased salmon numbers have caused crashes in zooplankton in odd-numbered years, when most pink salmon reach spawning size and are 25 times more abundant than in even-numbered years. The effect is so strong that even healthy breeding muttonbirds arriving in Tasmania are lighter most odd-numbered years.

Other factors are also affecting zooplankton. The Arctic seas are among the fastest warming on Earth. Marine heatwaves have been causing shifts in where and when zooplankton occur, and how large they grow.

When seabirds on a strict schedule arrive to feed, they can miss the zooplankton buffet. This has led to devastating wrecks for Arctic and sub-Arctic seabird species, including muttonbirds.

In 2013, millions of muttonbirds starved along Australia’s coast from K'gari/Fraser Island to Tasmania. Though we don’t know the exact cause, this was likely influenced by a double whammy: competition for food with salmon and a severe marine heatwave called “the blob”.

But what about the other causes? Examination of wrecked birds rules out plastic, blue-green algae and irradiated water from Fukushima as causes of death.

Birds are already in poor condition when they arrive. Storms or strong winds might push an already poorly muttonbird over the edge, but are generally not the cause of its poor condition. People often find muttonbirds after storms because onshore winds blow them from the sea onto beaches.

What Should I Do If I Find A Muttonbird?

If a muttonbird is too weak to fly, sadly it’s unlikely to recover.

If you want to give them a chance, though the odds are low, contact a specialist seabird rescue group. Seabirds have very specific care needs. Taking one home or feeding it, while well intended, may cause more harm than good.

If you find more than a few along the beach, you can report the wreck by emailing the author or contacting the University of Tasmania. Note the time, date, location and number of birds per kilometre.

If you find a muttonbird (or any bird) with a metal ring on its leg, please report the number to the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme.

What If I Find Other Dead Seabirds Or Waterbirds?

There’s another reason to watch out for unusual bird deaths this summer. A deadly bird disease has a high probability of reaching Australia’s shores. High pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI) has killed millions of birds worldwide, including seabirds.

The disease could enter Australia if carried by birds, including muttonbirds, migrating from the Northern Hemisphere (where HPIA is infecting wild bird populations) to Australia.

If you find an unusual number of sick or dying seabirds, shorebirds or waterbirds, report the incident to Wildlife Health Australia.![]()

Lauren Roman, ARC DECRA Fellow, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A monster eddy current is spinning into existence off the coast of Sydney. Will it bring a new marine heatwave?

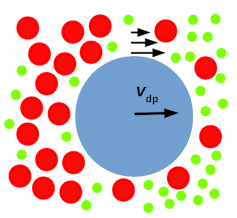

Right now, there’s something big spinning off the coast from Sydney – a giant rotating vortex of sea water, powerful enough to dominate the ocean currents off south-eastern Australia.

Oceanographers describe these spinning water bodies as “eddies” – but they’re not the small eddy currents you see in creeks or rivers. Ocean eddies are enormous. They’re usually hundreds of kilometres across (100–300km), up to 2km deep and can be visible from space.

It turns out these eddies drive change underwater by spawning marine heatwaves. Our new research demonstrates the link between a warm ocean eddy and a record-breaking marine heatwave which struck off Sydney from December 2021 to February 2022.

Now it’s happening again. An even bigger eddy is forming about 50km off Sydney. We have just returned from a 24-day research voyage on CSIRO’s research vessel RV Investigator to explore this monster eddy.

Our estimates suggest this 400km wide beast holds 30% more heat than normal for this part of the ocean. Its currents are spinning at 8km per hour. And the temperatures deep underwater are up to 3°C above normal. If it moves close to shore, it could trigger another coastal marine heatwave.

How Can An Eddy Current Make A Heatwave?

Eddies are the ocean equivalent of storms in the atmosphere. Like weather patterns, they can be warm or cold. But ocean eddies can shape the ocean’s patterns of life.

Warm eddies are like ocean deserts with little life, while cold eddies are typically much more productive. That’s because they draw up nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous from the deep sea, which become food for plankton.

Just as storms can in the atmosphere, ocean eddies can drive extreme “ocean weather”. That’s because warm eddies can bring in masses of warm water and keep it there for months. Sea life is often very finely attuned to temperature, so a sudden heatwave like this can heavily impact ecosystems.

It’s important to better understand how eddy currents grow, move and decay better. That’s because they can store large amounts of heat and can temporarily increase coastal sea levels.

What we do know is that warm eddies along Australia’s east coast can be fed by the East Australian Current when it becomes unstable. The current wobbles back and forth until eventually the wobbles form a coherent circle – an eddy – or adding to an existing one. It’s like a garden hose thrashing around on the grass when the flow is too great. These unstable currents can be small, on the kilometre scale, or huge.

Our research pinpointed the root cause of the 2021 marine heatwave off Sydney. A large warm eddy formed. But it couldn’t spiral away into deeper waters, because there were cold eddies to the north and south preventing it. That’s very similar to what can happen in the atmosphere, where a high pressure system can be held in place by other weather systems.

Now, it looks as if history is repeating.

Over the past month, an enormous eddy – fully 400km wide and 3km deep – has been spinning up just off southeastern Australia. It’s being fed by the warm East Australian Current, which brings warm water from the tropics down to more temperate waters. This eddy is bigger and warmer than most eddies in the region, especially at this time of year. It has been growing over the past month, and is pushing up against cold waters to the south. Where the two systems meet there are very strong temperature differences – up to 5°C over just 4km.

You can get some insight into how eddy currents behave from satellites.

Our trip on the research vessel RV Investigator made it possible for us to grasp how this powerful current was behaving – in three dimensions.

We also released drifters, GPS-tracked buoys which float around the eddy centre in a massive circle. Some have been carried more than 2,000km in the last month, passing where they originally started. Others have escaped the eddy and headed east into the Pacific.

These sensors and instruments have given us vital information. Now we know the water in the eddy is flowing at a fast walking pace, around 8km per hour. And we know that while the currents within the eddy are rotating quickly, the eddy itself has remained fairly stationary off the NSW coast, growing with warm waters from further north.

We also deployed five diving Argo floats. Satellite data shows us surface temperatures in the eddy have hit 23°C, two degrees above average for a month. But Argo floats show us the temperatures are even more extreme 500m below the surface, more than 3°C above average.

What happens to eddies? Like atmospheric systems, these are effectively heat engines. They transport heat to new areas as they whirl in the ocean. While they hold heat a long time, eventually it’s lost to the atmosphere and through mixing at the edges of the current. Eventually, they disappear.

But as we head into summer, the mega eddy is unlikely to go anywhere. If it moves towards the coast, where marine life is concentrated, we will see water temperatures spike – and possibly, underwater disaster for many species.

We would like to thank the RV Investigator’s Master, Captain Andrew Roebuck, Deck Officers and crew and the CSIRO technical staff.![]()

Moninya Roughan, Professor in Oceanography, UNSW Sydney; Amandine Schaeffer, Senior lecturer, UNSW Sydney; Junde Li, Postdoctoral research associate, and Shane Keating, Associate Professor, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Upcoming Workshop With Permaculture Northern Beaches + 2023 AGM + 2023 Raffle

Gardening for a Long Hot Summer

Gardening for a Long Hot Summer

Pet Cat Containment A Vital Step To Protect NSW’s Wildlife: Calls For Companion Animals Act Amendments

- Amend the NSW Companion Animals Act 1998 to enable local governments to enforce anti roaming laws for pet cats at a local level.

- Allocate a minimum of $9 million to fund compliance, education, desexing, identification and registration programs.

- Encourage local governments to develop companion animal management plans.

- Develop a state-wide web resource for pet owners.

- Streamline pet identification and registration processes.

- Make desexing mandatory state-wide.

- Collectively, roaming pet cats kill 546 million animals per year in Australia - 323 million of these are native

- In the Greater Sydney area, there are approximately 1 million pet cats and roaming pet cats kill 112 million animals per year - 66 million of these are native

- 71% of all pet cats in Australia are able to roam, and 78% of these roaming cats hunt

- 85% of the animals killed by pet cats are not brought home

- On average, each roaming, hunting pet cat kills more than three animals every week - for a total of 186 animals per year. This number includes 110 native animals (40 reptiles, 38 birds and 32 mammals).

- Hunting pet cats kill 30-50 times more native animals per square kilometre in suburbs than feral cats kill per square kilometre in the bush! This is because pet ownership allows inflated density: While feral cats kill 4x more animals per year, there are between 54 and 100 roaming and hunting cats per square kilometre in suburbs compared to only one feral cat for every 3-4 square kilometres in the bush.

- Pet cats kill 6,000 to 11,000 native animals per square kilometre each year in urban areas

- When cats prowl and hunt in an area, wildlife have to spend more time hiding or escaping. This reduces the time spent feeding themselves or their young, or resting.

- An analysis by the Biodiversity Council, Invasive Species Council and Birdlife Australia on the impact of roaming pet cats nationwide is available here.

- Whether or not you have a pet cat, you can help us protect native wildlife and keep pet cats safe by pledging support for better management of roaming pet cats by governments across Australia. This includes ensuring all states and territories have laws that facilitate and promote mandatory desexing, microchipping and 24/7 pet cat containment.

- If you are a cat owner, there are many things you can do to help keep pets happy and wildlife safe, but the most important thing is to keep your cat securely contained at home or on a leash at all times just like a pet dog. This will keep them safe from injury and disease and protect native wildlife in your local neighbourhood. You can transition your cat to a contained lifestyle by following this helpful guide from RSPCA. Responsible owners can also ensure pet cats are desexed, microchipped and registered.

Wakehurst Parkway Update: REF For Proposed Works Available - Feedback Closes December 6

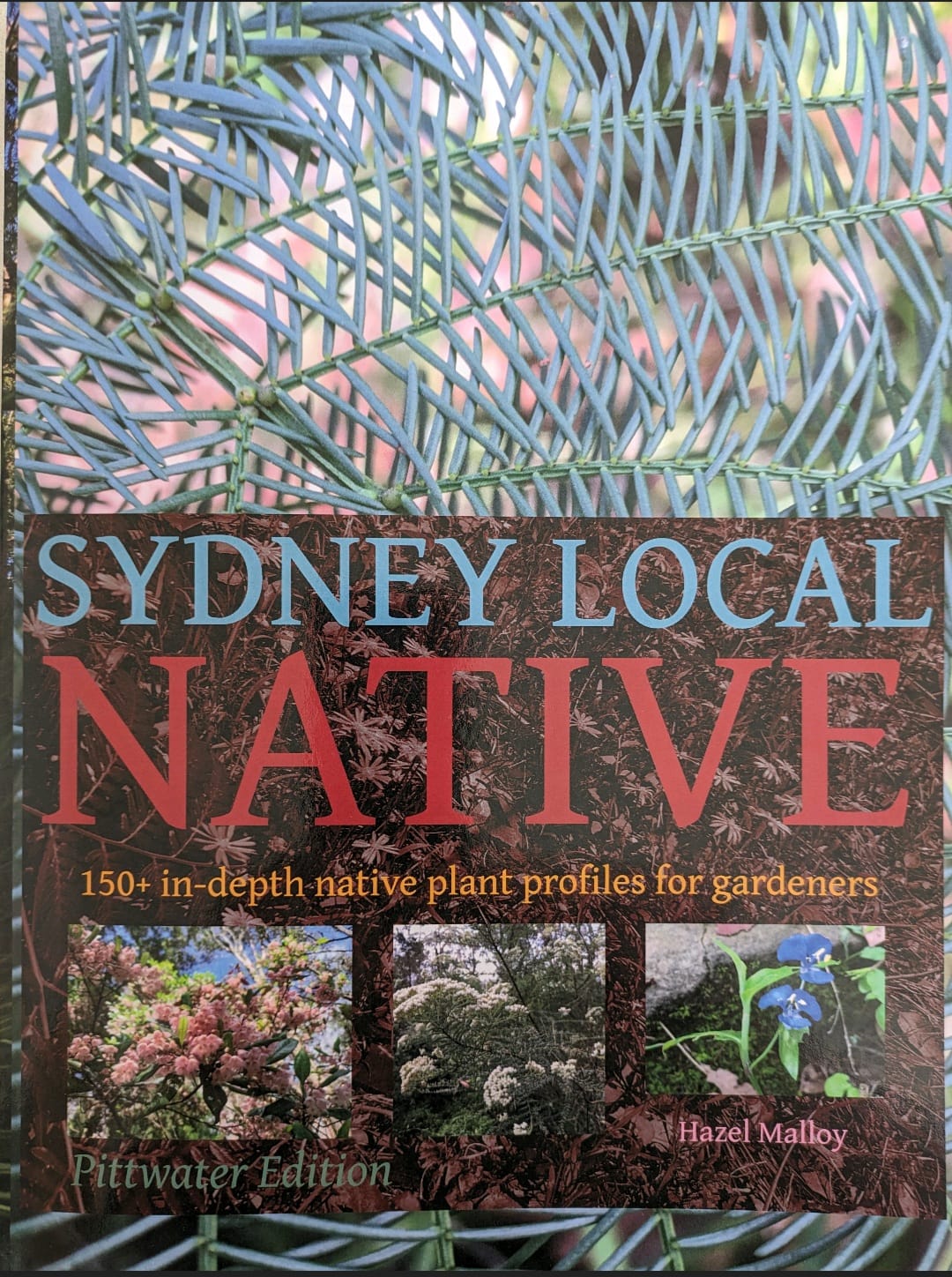

Sydney Local Native: Pittwater Edition Published

- average maximum height and width

- a description of the plant's form

- flower colour and flowering season

- an overview of the plant's best features

- its preferences for soil, water and light

- where it is naturally distributed.

Murray-Darling Bill Needs To Go Much Further To Deliver Real Water To Rivers And Justice For First Nations

$54.6 Million Investment To Clean Up Contaminated Sites Across The State

- Site investigations and remediation of contamination in buildings, soil and water at the former Bathurst Gasworks site which operated from 1888 until 1987.

- Dealing with lead contamination on Crown land sites at Captains Flat, where a multi-agency taskforce has been working on lead abatement plans after elevated lead levels were discovered from the former Lake George Mine which operated from 1882 until 1962.

- Remediation of the former Dural sandstone quarry which ceased in the early 2000s. More than 214 tonnes of waste have already been removed but further work is required to deal with landslip issues and contaminated soil.

- Remediating contamination and dealing with land stabilisation at Quarry Lane at Dural.

- Clean-up work on the former Empire Bay Marina site on the Central Coast. which has been declared significantly contaminated by the EPA.

- Dealing with legacy asbestos pollution on the Walka Water Works reserve at Oakhampton Heights near Maitland.

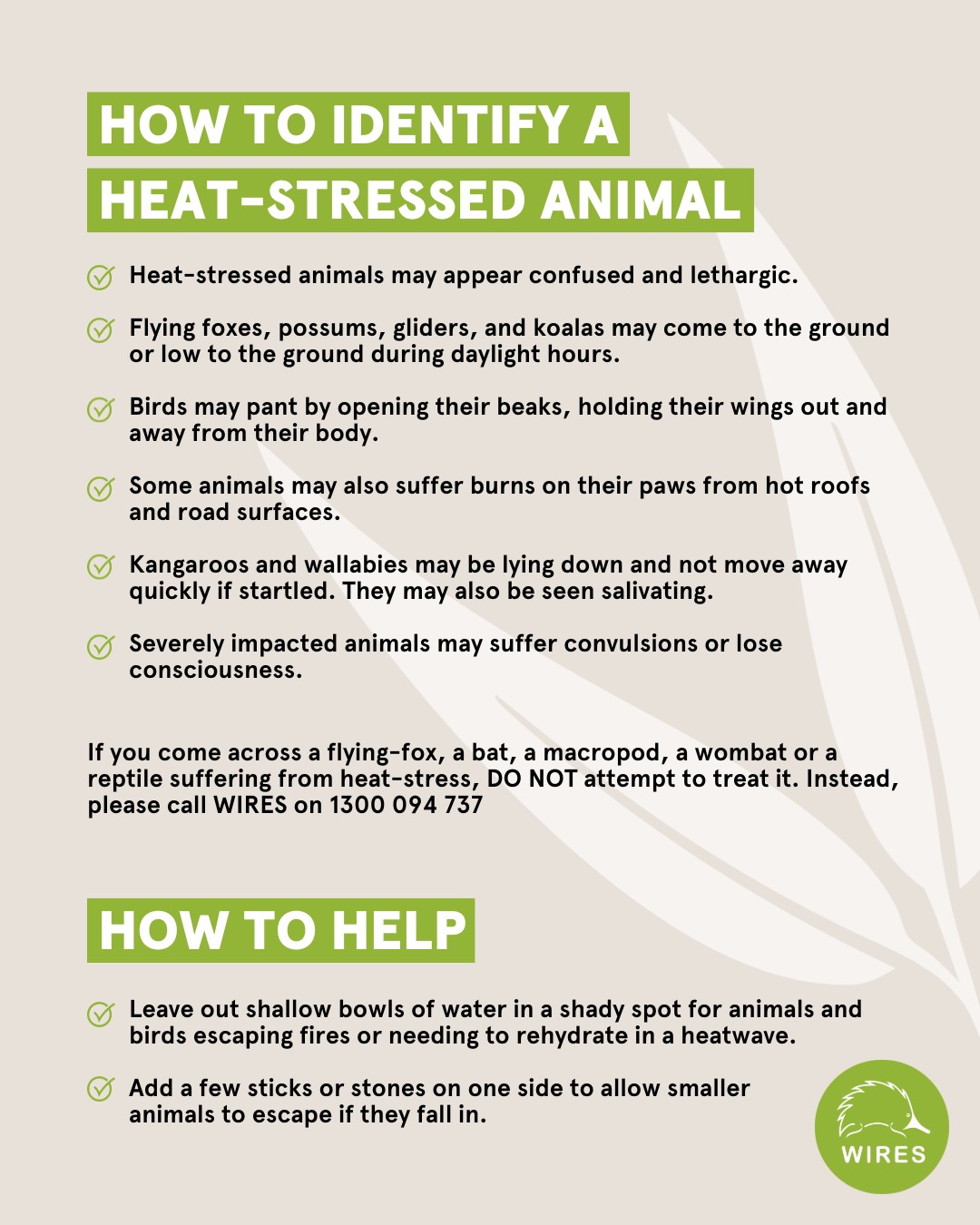

Please Look Out For Wildlife During Heatwave Events

AER Releases Social Licence For Electricity Transmission Directions Paper

- What expectations should be held of transmission businesses in undertaking community engagement

- What outcomes need to be achieved from engagement

- When and how social licence issues can be factored into regulatory tests for the approval of and recovery of cost for new transmission development

- What evidence is needed to justify transmission network expansion and associated expenditure.

- clearly identify the information that is the subject of the confidentiality claim

- provide a non-confidential version of the submission in a form suitable for publication.

Bushwalk Fundraiser

- Friday 8 December

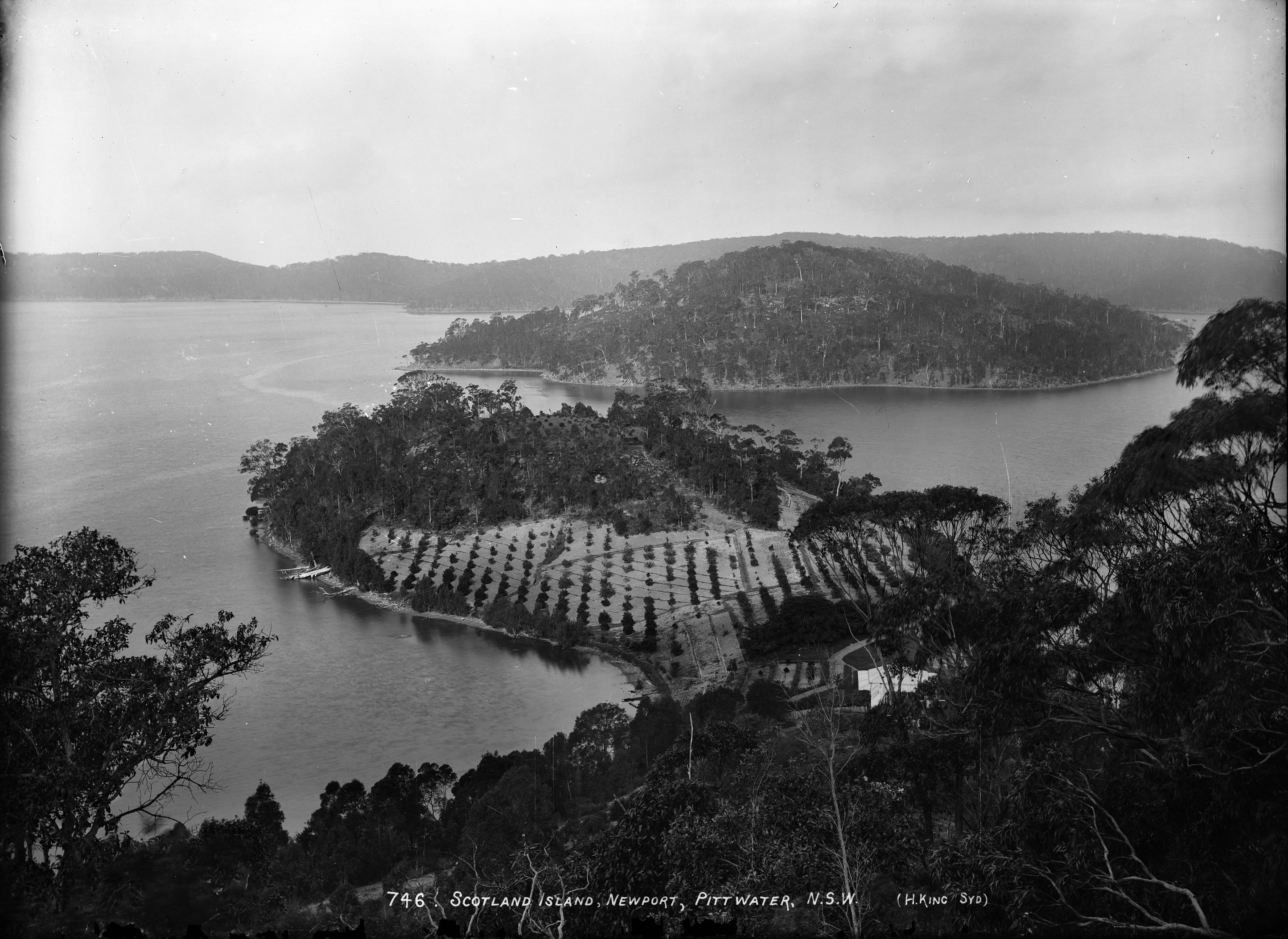

'Scotland Island, Newport, Pittwater, N.S.W.', photo by Henry King, Sydney, Australia, c. 1880-1886. and section from to show cottage on neck of peninsula at western end with no chimneys through roof. From Tyrell Collection, courtesy Powerhouse Museum

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

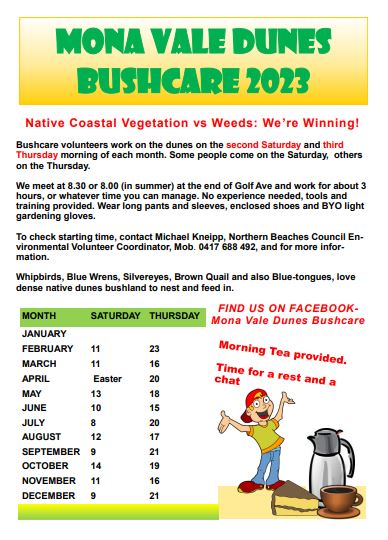

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

26 years ago, Howard chose fossil fuels over the Pacific. What will Albanese choose?

Wesley Morgan, Griffith UniversityHot on the heels of trips to Washington and Beijing, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is now in the Cook Islands for the Pacific Island Forum. There, he will aim to strengthen relations with Pacific countries and reaffirm Australia’s place as a security partner of choice.

But to do that, he’ll have to repair a historic split from when former prime minister John Howard met with Pacific leaders on the same island, Aitutaki, a quarter of a century ago to defend his choice to expand Australia’s fossil fuel industries.

Pacific leaders see climate change as by far their greatest security threat. Sea level rise, stronger cyclones, marine heatwaves and ocean acidification pose existential threats. They will ask Albanese to support a regional declaration for a phaseout of fossil fuels.

What will happen on the atoll? We could see history repeat – Pacific outrage, Australian intransigence. Or we could see a better outcome, if Albanese signals Australia is at last ready to move away from fossil fuels.

A Split In Aitutaki

When a scientific consensus on global warming emerged in the mid-1980s, Australia’s initial response was aligned with Pacific nations. In fact, they called for industrialised countries to immediately cut greenhouse gas emissions in a joint statement in 1990.

Pacific island nations suggested Australia’s national target – to cut emissions by 20% by 2005 – should be binding for all developed countries.

That brief window soon closed. Under sustained lobbying from the fossil fuel industry, the Australian government came to see global climate action as a threat to economic prosperity.

At the first Conference of Parties (COP1) to the UN climate convention in 1995, Australia’s negotiators argued for a weaker emissions target because our economy was more fossil fuel dependent than comparable nations. This positioning in the UN climate talks was further entrenched when Howard came to power in 1996.

Differences with island nations came to a head at the 1997 South Pacific Forum, when island leaders tried to persuade Howard to support their calls for globally binding emissions cuts ahead of Kyoto Protocol negotiations later that year. Discussions in Aitutaki turned bitter and ran into overtime in the airport lounge.

Howard was not moved. At the Kyoto negotiations, Australia sought and won its own clause, allowing it to actually increase emissions, and expand its fossil fuel industries.

Afterwards, the Cook Islands prime minister Geoffrey Henry described Australia’s approach as a “self-serving” attempt to protect coal and energy intensive industries. Tuvalu prime minister Bikenibau Paeniu told regional media that “Australia dominates us so much in this region, for once we would have liked to have got some respect”.

For his part, Howard dismissed concerns that climate change and sea-level rise could threaten island states as “exaggerated” and “apocalyptic”.

Australia’s decision has rankled ever since.

Could We See Australia Repair The Rift?

For his part, Albanese has said he wants to repair the climate rift. At last year’s forum, he joined island leaders to declare a Pacific climate emergency. Australia is bidding to host the UN climate talks in 2026 in partnership with Pacific island countries, a move island leaders have formally welcomed. But it’s also clear Pacific countries want him to support a regional declaration to phase out fossil fuels.

Pacific governments have not been sitting still. This year, a group of Pacific governments called for a fossil-fuel-free Pacific. Island countries want to establish a new Pacific Energy Commissioner to oversee the region’s energy transition.

Pacific countries are also campaigning for a global Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty which would oversee the end of fossil fuel expansion. These goals will be put to leaders again this week – including Albanese.

There are signs Albanese will arrive with new climate finance in hand, including A$50 million for the global Green Climate Fund and funds for a regional Pacific Resilience Facility. Support to tackle rising climate adaptation costs will be welcomed, but it won’t be enough for Pacific leaders. What they want to see is their regionally powerful neighbour actually stop adding fuel to the fire.

Vanuatu’s climate minister Ralph Regenvanu says Pacific nations need genuine allies who will make substantive commitments to move away from coal, oil and gas.

No Stopping The Global Energy Transition

It’s not just Pacific nations calling on Australia to commit to a fossil fuel phase-out. Germany’s international climate envoy Jennifer Morgan is headed to this week’s forum to call on Australia to support the European Union push for a phase-out at next month’s UN COP28 climate talks in Dubai.

Ambassador Morgan this week said:

we have to not only phase out fossil fuels, we need to stop building new infrastructure for fossil fuels, because they will become stranded assets. We need to be working on a just transition for workers and building up new industries.

She has a point. The International Energy Agency last week released its annual World Energy Outlook, which found global deployment of renewable energy technologies is rapidly overtaking fossil fuel projects, and demand for fossil fuels is likely to peak before 2030.

Australia’s economic interests are shifting as the world economy heads toward net zero emissions. Gas and coal aren’t the only valuable things underneath Australian dirt – we’ve got a wealth of critical minerals vital to the clean energy transition.

Governments have no choice but to plan for the inevitable decline of fossil fuels and smooth the transition to clean energy industries such as battery manufacturing and green hydrogen and ammonia.

The sooner Australia gets on with the transition away from fossil fuels, the sooner we will be embraced by the rest of the Pacific family. ![]()

Wesley Morgan, Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Luminous ‘mother-of-pearl’ clouds explain why climate models miss so much Arctic and Antarctic warming

Our planet has warmed by about 1.2°C since 1850. But this warming is not uniform. Warming at the poles, especially the Arctic, has been three to four times faster than the rest of the globe. It’s a phenomenon known as “polar amplification”.

Climate models simulate this effect, but when tested against the past 40 years of warming, these models fall short. The situation is even worse when it comes to modelling past climates with very high levels of greenhouse gases.

This is a problem because these are the same models used to project into the future and forecast how the climate will change. They are likely to underestimate what will happen later this century, including risks such as ice sheet melting or permafrost thawing.

In our new research published today in Nature Geoscience we used a high-resolution model of the atmosphere that includes the stratosphere. We found a special type of cloud appears over polar regions when greenhouse gas concentrations are very high. The role of this type of cloud has been overlooked so far. This is one of the reasons why our models are too cold at the poles.

Back To The Future

Looking into past climates can give us glimpses of possible futures for a range of extreme conditions. For us, this means we can use Earth’s history to find out how well our climate models perform. We can test our models by simulating episodes in the past when Earth was much warmer. The advantage of this is that we have temperature reconstructions for these episodes to evaluate the models, as opposed to the future, for which measurements are not available.

If we go back 50 million years or so, our planet was very hot. Carbon dioxide (CO₂) concentrations ranged between 900 and 1,900 parts per million (ppm), compared with 415 ppm today. Methane (CH₄) concentrations were likely also much higher.

Canada’s arctic archipelago was covered in lush rainforests inhabited by alligators, turtles, lizards and mammals.

For these plants and animals to survive, conditions must have been warm and ice-free year-round. Indeed, surface ocean temperatures exceeded 20°C near the north pole (at about 87°N) and 25°C in the Southern Ocean (at about 67°S).

This period called the early Eocene is a perfect test bed for our models, because it was globally very warm, and the poles were even warmer, meaning it was a climate with extreme polar amplification. In addition, the Eocene is recent enough for temperature reconstructions to be available.

But as it turns out, the models fail again. They are much too cold at high latitudes. What are our models missing?

Polar Stratospheric Clouds

In 1992 American paleoclimatologist Lisa Sloan suggested polar stratospheric clouds might have caused extreme warming at high latitudes in the past.

These clouds are a rare and beautiful sight today. They are also called nacreous or mother-of-pearl clouds for their vivid and sometimes luminous colours.

They form at very high altitudes (in the stratosphere) and at very low temperatures (over the poles). In the present day climate, they appear mainly over Antarctica, but have also been observed during winter months over Scotland, Scandinavia and Alaska, at times when the stratosphere was particularly cold.

Just like greenhouse gases, they absorb infrared radiation emitted by the Earth’s surface and re-emit a portion of this energy back to the surface. This suggests polar stratospheric clouds could be one of the missing puzzle pieces.

They warm the surface. And their effect could be significant, especially in winter, when the sun does not rise. But they are difficult to simulate in a climate model, so most models ignore them. This omission could explain why climate models miss some of the polar warming, because they miss a process that warms the poles.

Three decades after Sloan’s paper, a few atmosphere models are finally complex enough to allow us to test her hypothesis. In our research we use one of them and find that under certain conditions, the additional warming due to these polar stratospheric clouds exceeds 7°C during the winter months. This significantly reduces the gap between climate models and temperature evidence from the early Eocene. Sloan was right.

Implications For Future Projections

Our research explains why climate models don’t work so well for past climates when greenhouse gas levels were much higher than they are today. But what about the future? Should we be concerned?

There is some good news. While polar stratospheric clouds do warm the poles, they won’t be as common in the future as they were in the distant past, even if both CO₂ and CH₄ reach very high levels.

This is due to another difference between the Eocene and today: the position of continents and mountains, which were different back then and which also influence the formation of polar stratospheric clouds. So even if we hit early Eocene levels of CH₄ and CO₂ in the future, we would expect less polar stratospheric cloud to be formed. This suggests the standard climate models are better at predicting the future than the past.

It’s therefore unlikely the Arctic and Antarctica will be covered by these beautiful clouds anytime soon. But our research shows evidence from past climates can reveal processes that only become important when greenhouse gas concentrations are high. Some of these processes are not included in our models because models are tested against present day observations and other processes simply seemed more important to include. Looking into the past is a way of broadening our horizon and learning for the future.![]()

Katrin Meissner, Professor and Director of the Climate Change Research Centre, UNSW, UNSW Sydney; Deepashree Dutta, Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Cambridge, and Martin Jucker, Lecturer in Atmospheric Dynamics, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

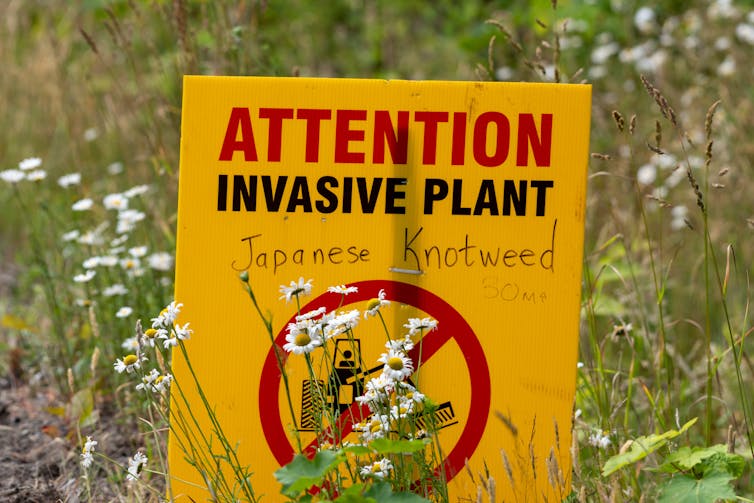

Extreme weather may help invasive species outcompete native animals – new study

Non-native species appear to be better able to resist extreme weather, threatening native plants and animals and potentially creating more favourable conditions for invasive species under climate change. That’s the conclusion of a new study in the scientific journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Wildfires, droughts, heavy rainfall and storms are all increasing, and predicted to become more frequent throughout the next century due to human-driven climate change.

At the same time, humans are transporting more species into new areas, despite concerted global efforts to increase biosecurity across borders and to target the eradication of specific species. Some of these non-native species can go on to become invasive, damaging native ecosystems.

Capitalising On Opportunities

Invasive species introduced by humans often possess traits that help them survive or even thrive when ecosystems are disturbed (perhaps by wildfire, a storm or human buildings).

Invasive plants are generally fast-growing, for instance, allowing them to quickly fill gaps before native species can recover from disturbances. They are also often very good at dispersing their seeds, allowing them to quickly colonise disturbed areas.

This is why scientists have long suspected that extreme weather and the success of non-native species could be linked.

If extreme weather removes native plants and animals, that increases the availability of resources such as water and space. Non-native species can then capitalise on these new resources to establish themselves.

Even more concerning is the potential for extreme weather and non-native species to interact, exacerbating their effect on native biodiversity. For instance, in a recent field experiment in the US, scientists deliberately started a fire which killed about 10% of the longleaf pine trees in the area studied.

But in areas where an invasive grass – cogongrass, an Asian native – was allowed to establish itself alongside the pines, the fires had more fuel and were larger, hotter and burned for longer.

Where the scientists had added rain shelters to simulate drought conditions, the grass dried out further and the fires became much more lethal. A combination of drought and the invasive species meant longleaf pine mortality soared to 44%.

Similarly, on the small Macquarie Island in the south west Pacific, a combination of extreme rainfall and the presence of invasive European rabbits reduced the breeding success of nesting black-browed albatrosses. Heavy grazing by the invasive rabbits reduced plant cover, exposing the albatross chicks to the harsh weather conditions.

This relationship between extreme weather and invasive species – two human-driven drivers of global change – threatens native plants and animals and could cost countries billions of dollars in coming decades. Ecologists must identify priority areas and species that can be targeted in efforts to minimise costs and prevent the loss of native biodiversity.

Bad Weather, Good For Non-Natives

To better understand how native and non-native species respond to extreme weather events, the scientists behind the new study reanalysed information from 443 peer-reviewed studies on how species responded to wildfires, droughts and storms. In all, they gathered data on 187 non-native species and 1,852 native species from all major animal groups.

Their results suggest that native and non-native species may indeed respond differently to extreme weather. Across all studies, a total of 24.8% of non-native species benefited from extreme weather events compared to only 12.7% of native species.

For example, while native species in both freshwater and land-based ecosystems were harmed by droughts, their non-native counterparts showed no significant response. Notably, marine ecosystems were comparatively more resistant to extreme weather events, with fewer differences between native and non-native species.

The authors did find marine heatwaves harmed native coral species, however, a relationship that has been documented in other scientific studies.

Identifying Global Hotspots

The authors took this information and combined it with known global hotspots of extreme weather, to identify areas where native species may be particularly vulnerable to the combination of extreme weather and invasive species.

They found high latitude areas such as northern US and Europe, for instance, are both vulnerable to extreme cold spells and possess non-native species that benefit from cold spells. Alternatively, areas of the western Amazon in Brazil and east Asia were identified as vulnerable to flooding and possessing flood-resistant non-native species.

In these regions, non-native species could benefit from increasing cold spells or flooding respectively, posing a greater threat to native plants and animals.

Studies like this are very useful. Regions that are identified as vulnerable can be targeted with early preventative measures to stop the spread of invasive species, or with measures to help native biodiversity cope with climate change.

This research could also allow targeted restoration to remove non-native species and produce invasion-resistant native communities that could better withstand future conditions. This is what happened on Macquarie Island, where invasive rabbits and rats were eventually eliminated and the whole ecosystem soon bounced back.

Such action could be critical as we adapt to a changing climate and a greater mixing of the world’s plants and animals.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Harry Shepherd, Postdoctoral Research Associate, King's College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How global warming shakes the Earth: Seismic data show ocean waves gaining strength as the planet warms

As oceans waves rise and fall, they apply forces to the sea floor below and generate seismic waves. These seismic waves are so powerful and widespread that they show up as a steady thrum on seismographs, the same instruments used to monitor and study earthquakes.

That wave signal has been getting more intense in recent decades, reflecting increasingly stormy seas and higher ocean swell.

In a new study in the journal Nature Communications, colleagues and I tracked that increase around the world over the past four decades. These global data, along with other ocean, satellite and regional seismic studies, show a decadeslong increase in wave energy that coincides with increasing storminess attributed to rising global temperatures.

What Seismology Has To Do With Ocean Waves

Global seismographic networks are best known for monitoring and studying earthquakes and for allowing scientists to create images of the planet’s deep interior.

These highly sensitive instruments continuously record an enormous variety of natural and human-caused seismic phenomena, including volcanic eruptions, nuclear and other explosions, meteor strikes, landslides and glacier-quakes. They also capture persistent seismic signals from wind, water and human activity. For example, seismographic networks observed the global quieting in human-caused seismic noise as lockdown measures were instituted around the world during the coronavirus pandemic.

However, the most globally pervasive of seismic background signals is the incessant thrum created by storm-driven ocean waves referred to as the global microseism.

Two Types Of Seismic Signals

Ocean waves generate microseismic signals in two different ways.

The most energetic of the two, known as the secondary microseism, throbs at a period between about eight and 14 seconds. As sets of waves travel across the oceans in various directions, they interfere with one another, creating pressure variation on the sea floor. However, interfering waves aren’t always present, so in this sense, it is an imperfect proxy for overall ocean wave activity.

A second way in which ocean waves generate global seismic signals is called the primary microseism process. These signals are caused by traveling ocean waves directly pushing and pulling on the seafloor. Since water motions within waves fall off rapidly with depth, this occurs in regions where water depths are less than about 1,000 feet (about 300 meters). The primary microseism signal is visible in seismic data as a steady hum with a period between 14 and 20 seconds.

What The Shaking Planet Tells Us

In our study, we estimated and analyzed historical primary microseism intensity back to the late 1980s at 52 seismograph sites around the world with long histories of continuous recording.

We found that 41 (79%) of these stations showed highly significant and progressive increases in energy over the decades.

The results indicate that globally averaged ocean wave energy since the late 20th century has increased at a median rate of 0.27% per year. However, since 2000, that globally averaged increase in the rate has risen by 0.35% per year.

We found the greatest overall microseism energy in the very stormy Southern Ocean regions near the Antarctica peninsula. But these results show that North Atlantic waves have intensified the fastest in recent decades compared to historical levels. That is consistent with recent research suggesting North Atlantic storm intensity and coastal hazards are increasing. Storm Ciarán, which hit Europe with powerful waves and hurricane-force winds in November 2023, was one record-breaking example.

The decadeslong microseism record also shows the seasonal swing of strong winter storms between the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It captures the wave-dampening effects of growing and shrinking Antarctic sea ice, as well as the multi-year highs and lows associated with El Niño and La Niña cycles and their long-range effects on ocean waves and storms.

Together, these and other recent seismic studies complement the results from climate and ocean research showing that storms, and waves, are intensifying as the climate warms.

A Coastal Warning

The oceans have absorbed about 90% of the excess heat connected to rising greenhouse gas emissions from human activities in recent decades. That excess energy can translate into more damaging waves and more powerful storms.

Our results offer another warning for coastal communities, where increasing ocean wave heights can pound coastlines, damaging infrastructure and eroding the land. The impacts of increasing wave energy are further compounded by ongoing sea level rise fueled by climate change and by subsidence. And they emphasize the importance of mitigating climate change and building resilience into coastal infrastructure and environmental protection strategies.![]()

Richard Aster, Professor of Geophysics and Department Head, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Window To The Past: New Microfossils Suggest Earlier Rise In Complex Life

Making money green: Australia takes its first steps towards a net zero finance strategy

Alison Atherton, University of Technology Sydney and Gordon Noble, University of Technology SydneyThis article is part of a series by The Conversation, Getting to Zero, examining Australia’s energy transition.

Just north of Jamestown in South Australia, 70 kilometres east of the Spencer Gulf and next to a wind farm of nearly 100 turbines, stands the world’s first big battery.

Built in partnership with Tesla and financed and operated by Neoen, a French multinational renewable energy developer, the Hornsdale Power Reserve and other big battery projects could stimulate a homegrown battery industry, contributing many billions of dollars and thousands of jobs to the Australian economy. But for that industry to rise, it will need money.

Australia aspires not only to transition its economy to net zero emissions, but to become a green energy superpower. That means building a host of solar and wind farms, batteries, electric vehicle charging stations, upgrades to the grid and to all kinds of buildings, as well as investments in new technology.

These investments and big infrastructure projects don’t come cheap. Getting to net zero emissions by 2050 requires investment in renewable energy of A$754 billion in power generation alone, according to research by the UTS Institute for Sustainable Futures and funded by Future Super.

The Size Of The Green Finance Challenge

By 2030, the world will have to invest an estimated US$4.3 trillion a year – roughly the GDP of Japan, the world’s third-largest economy – in climate finance. These financial flows need to grow by 21% a year, on average. Without this enormous increase, the economic transition will not happen in time to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

The scale of financing means that superannuation funds and other big institutional investors must be involved. They need to know where their money is going, and whether investments are genuine or a case of “greenwashing”. They need certainty that companies in which they invest have solid plans to reduce their climate risk, and the ability to ask the companies questions when they don’t.

But current financial regulation is not set up to support such best practice. To give just one example, default superannuation funds lack the benchmarks – measures of performance assessed by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority – they need to invest in start-up businesses that are developing clean energy technologies.

Successive Australian governments have been slow to grasp this reality, and we are now playing catch-up with many other countries.

Australia Releases Its Strategy

The Australian government’s Sustainable Finance Strategy, released by Treasurer Jim Chalmers last Thursday, lays solid foundations for this recovery. Yet more needs to be done if Australia is to achieve the strategy’s stated ambition to be a global sustainability finance leader.

The strategy is arranged around three core pillars. The first focuses on creating access to information that is credible, accurate and of practical value. It seeks to ensure markets operate efficiently and money flows to where it is most needed.

From July 1 2024, large Australian companies and financial institutions will have to disclose information about the impacts of climate on their business, the risks climate change poses to their operations, and how they plan to decarbonise.

The disclosure requirements will be based on internationally accepted standards, to ensure Australian and overseas investors can compare data across companies and countries.

The government is also supporting the development of an Australian sustainable finance taxonomy – a set of criteria that enables investors to evaluate whether and to what extent an investment supports sustainability goals.

A taxonomy spells out which investments result in real decarbonisation, and reduces the likelihood of false claims about the sustainability of projects and investments. A government agency will manage the taxonomy, which will start as a voluntary code but may eventually become mandatory.

Large companies will also be required to disclose their net zero transition plan, if they have one. With companies representing 80% of the market capitalisation of ASX 200 companies pledging to achieve net zero emissions, the government wants to ensure their plans are credible. It wants the corporate regulator, the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC), to set out its expectations of the plans – a welcome step.

The second pillar focuses on building the capabilities of Australia’s financial system regulators to manage risk and to clamp down on greenwashing – the practice of making misleading or deceptive claims about the environmental benefits of activities or assets.

Fighting Greenwashing

ASIC Deputy Chair Karen Chester believes the economic cost and loss of investor confidence caused by greenwashing “cannot be overstated”. Her organisation has set out guidelines to help financial institutions identify it. This year ASIC launched its first three legal actions, including one against the local arm of US investment giant Vanguard, and another against Active Super, which allegedly falsely claimed it had eliminated investments, such as coal mining, that posed too great a risk to the environment and the community.

The third pillar concerns government leadership and engagement. Such a large and rapid increase in the scale of private sector finance requires growth in a range of financial assets, including shares, bonds and other kinds of debt.

The government is supporting the development of a green bond market by issuing Australia’s first green sovereign bond in June. These bonds are designed to establish standards for lending and borrowing for all green finance; they will also help the government to fund projects such as electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

Finally, the strategy recognises the importance of collaboration across the Asia-Pacific. If Australia achieves its goal of becoming a regional sustainable finance hub it would not only benefit our national interest but help Pacific Island nations to raise the finance to decarbonise.

What’s Missing From The Strategy?

The strategy does not focus on green finance skills and competencies. Yet these capabilities, ranging from a basic understanding of what business activities are unsustainable to specialist expertise in the use of scenario analysis to assess climate risk, are essential to the net zero transition.

LinkedIn’s recent Green Skills Report shows that, globally, the finance sector is lagging behind other sectors in building green skills. And Australia ranks only 30th in a list of countries on its share of talent for green finance.

Australia’s financial system must urgently transform itself to meet the climate challenge. If the financing of the transition were a bicycle race, Australia has now caught up to the global peloton. The next step is to take the lead.![]()

Alison Atherton, Program Lead, Business, Economy and Governance at the Institute for Sustainable Futures., University of Technology Sydney and Gordon Noble, Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Our minds handle risk strangely – and that’s partly why we delayed climate action so long

We now have a very narrow window to significantly and rapidly slash greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the most disastrous effects of climate change, with just an estimated six years left before we blow our carbon budget to stay below 1.5°C of warming.

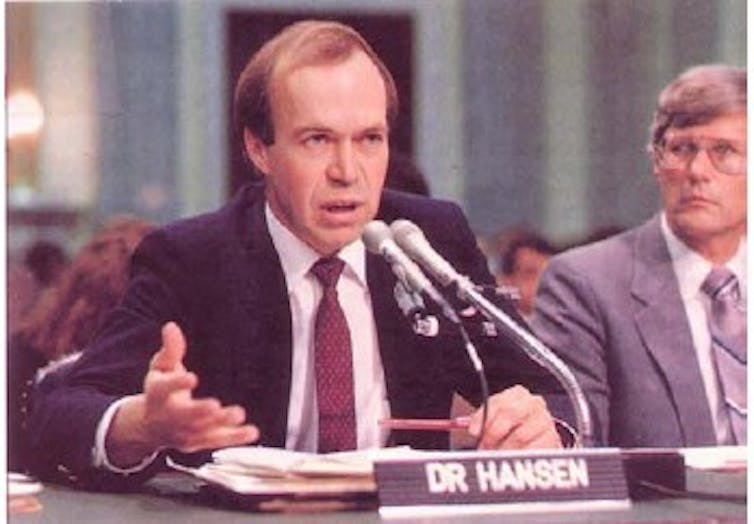

We’ve known how gases like carbon dioxide trap heat for over 100 years and alarm bells have been ringing loudly for over 35 years, when climate scientist James Hansen testified that global warming had begun.

As extreme weather and temperatures arrive, many of us wonder whether it had to get this bad before we acted. Did we need to see to believe? What role has our own psychology played in our sluggishness?

How Do We Respond To Threats?

From a psychology point of view, motivating us to take action on climate is a wicked problem. Many factors combine to make it harder for us to act.

The necessary policies and behaviour changes have been viewed as too hard or costly. Until recently, the consequences of doing nothing have been seen as a distant problem. Given the complexity of climate modelling, it has been difficult for scientists and policymakers to lay out what the specific environmental consequences would be from any given action or when they would manifest.

As if that’s not enough, climate change presents a collective-action problem. It would do little good for Australia to reach net-zero emissions if other countries keep emitting without change.

When we write about climate change, we often frame it as an ever more urgent and significant threat to our way of life. We do this thinking that showing the seriousness of the threat will galvanise others into faster action.

Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case. When we’re confronted with big risks – and the need for a painful shift from the status quo – some of us respond unexpectedly. We might find ourselves motivated to seek out evidence to undercut the reality of the threat, and use this uncertainty to justify staying on the same path.

One unfortunate aspect of this is that people motivated to avoid or deny climate risk are actually better able to do so when they have more scientific training. This background equips them better to counter-argue and rationalise the dissonance, meaning they seek out information to align with their beliefs and justify their passivity. Misinformation and doubt are particularly damaging to climate action. They let us feel OK about inaction.

This tendency to rationalise away risk was also clearly visible among people who downplayed the impact or even denied the existence of COVID-19.

Is there an antidote?

We’ve found explaining the simple and well-understood way that emissions of specific gases trap the Sun’s heat and warm the planet can be effective, because people can’t rationalise these facts away. The greenhouse effect is a well-accepted phenomenon, even by those most sceptical of global warming. After all, it’s essential to life on Earth – without these gases trapping heat, the world would be too cold for life.

Why Are We Finally Acting?

As climate change has moved out of the computer models and become very much a part of our present, we are seeing stronger efforts to cut emissions.

More and more of us are experiencing tangible events such as forest fires, droughts, sudden floods, rapidly intensifying hurricanes or record-breaking heatwaves. This has removed one barrier to inaction. Until now, the consequences of doing nothing seemed far off and uncertain. Now they are seen as certain and already present.

Better still, technological advancement and economies of scale in production have meant clean energy and clean transport have fallen significantly in price.

At government and individual levels, there are now measures we can take that aren’t too costly and come with immediate gains such as cutting power bills or avoiding petrol price increases. Greater political consensus in many countries is also helping challenge the inertia of the status quo. That’s another barrier to action evaporating.

As climate damage gets worse, we’re likely to see ever-starker warnings. Does fear motivate us? When faced with threats, we are more likely to take action, particularly if we think we can make a difference.

Yes, we now have a very narrow window to avert the worst. But we also have an increased certainty about climate change and the damage it causes, as well as greater confidence in our ability to bring about change.

For years, our own psychology slowed down efforts to make the sweeping changes necessary to quit fossil fuels. Now, at least, some of these psychological barriers are getting smaller. ![]()

Jeff Rotman, Senior Lecturer in Marketing and Consumer Psychology & Co-Director of the Better Consumption Lab, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Planet Earth III: how cookie cutter nature programming could fail to educate and inform audiences

Leora Hadas, University of NottinghamPerhaps nothing embodies the BBC’s values of inform, educate and entertain more than its nature documentaries. Planet Earth III is the latest in a proud tradition going back to the founding of the BBC Natural History Unit in 1957 and has everything devoted fans (myself included) expect.

There are sweeping shots, a soaring orchestral soundtrack, and exciting scenes of hunting, courtship and breeding. Tender family relations, desperate chases and amazing survival stories are all narrated in Sir David Attenborough’s signature style. Planet Earth III brings us all the beauty and wonder we know and love – which may be a problem when it tries to sound an urgent warning about the future of our world.

In terms of its story, Planet Earth III warns of environmental catastrophe more than any similar BBC show before it. The second episode includes a heartbreaking scene of seals caught screaming in a fishing net and ends with a question: can animals really adapt to survive our changing planet?

Part of this new willingness from the BBC to tackle environmental collapse head-on is due to the climate and ecological crisis that has become increasingly obvious and urgent. But another cause can be found in another crisis the BBC is facing.

What we might call the “planet format” has become so perfected and so popular, that the BBC’s competitors are eager to pick it up themselves. The format is a good fit for streaming platforms like Netflix, Amazon and Apple+. But with them all creating similar programmes, what effect does that have on their ability to inform, educate or entertain?

Comforting Catastrophe

Nature and wildlife stories are universally engaging and are great for showing off high budgets and virtuoso filmmaking. Copyright laws can protect a show’s characters or plot, but not a visual, musical or storytelling style.

This has led to many competitors fighting for a slice of this global market with shows that look, feel and sound virtually the same. Netflix has expanded their scope with Our Planet, Our Planet II and Our Universe (2022). Apple+ came out with Prehistoric Planet (2022). The format – from the timbre and rhythm of Attenborough’s narration to the style of shots – is even now used globally in productions like the Indian Wild Karnataka (2019).

It’s good to have more documentaries tackling the collapse of the natural world. But, I do wonder, what effect their looking and sounding the same might have on their ability to really educate audiences about the climate crisis and communicate the urgency of it. These stories all follow a single format, comforting in its familiarity but should anything that seeks to educate about climate catastrophe be comforting?

The planet formula is not just the stories it tells – it’s also how it tells them. Whether Planet Earth or Our Planet, Wild Karnataka or for the BBC’s Wild Isles (2023), the sweeping shots of pristine wilderness, the striking views and the orchestral music are the same. And the main emotion this formula works to inspire is not urgency, but awe.

An academic report commissioned by the BBC tells us that watching nature documentaries can soothe climate anxiety. This may seem paradoxical when the narration tells us about the loss of precious species and habitats. But consider what the format spends most of its time showing us: untouched landscapes unfolding endlessly from the air, beautiful animals in super high definition, and no humans in sight. Even Attenborough is only present through his calm and grandfatherly tone.

Neither Netflix nor anyone else has attempted to change these features: they are baked too deeply into the successful formula, and keeping to the formula is what keeps audiences coming. The narration in Planet Earth III might be telling us that time is running out to act, but the show invites us to sit back and absorb.

There is also the question of diversity. The climate crisis is a global problem with many faces, but the BBC’s planet format was born out of a particularly British tradition of nature programming. What do we lose when environmental stories are all told through the same lens and speak with the same voice?

Tackling Climate Change Head On

The increase in competition has led to one important change. Produced by the BBC’s frequent partner Silverback, Our Planet, which was released in 2019, was shot and edited in the same familiar and beloved style and featured the same type of animal stories. The first season did, however, offer one distinct competitive edge: a clear focus on environmental issues, which the BBC’s had been sorely lacking.

The BBC’s nature documentaries have come under considerable criticism over the years for not addressing the climate and ecological crisis. Historically, the BBC had chosen to stay neutral on the debate about human-caused global heating and this decision affected the Planet shows.

To undermine their rival, Netflix partnered with the World Wildlife Federation for Our Planet and widely promoted the show’s environmental message to audiences. The streaming platform presented itself as more progressive and cutting-edge than the staid and conservative BBC.

It was now survival of the fittest in the field of nature documentaries and this was not a bad thing for the BBC who now had to adapt and improve their nature content in the face of competition by explicitly tackling climate.

This one change, while great and urgently needed, has been quickly folded into the planet format and is a feature of all subsequent nature shows. This one change was not enough.

The popularity of nature documentaries means they can play an important role in making audiences aware of the state of our world. But for the Planet format to survive in the changing media ecosystem, the TV industry must keep an eye on whether and how it can continue to evolve.