Inbox and Environment News: Issue 606

November 19 - 25, 2023: Issue 606

PNHA: Invertebrate Night Life In McCarrs Creek Reserve November 25 - All Welcome - Part Of Great Southern BioBlitz 2023

Collaroy Beach Coastal Works: Have Your Say - Closes December 3

- completing the submission form here

- emailing council@northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au

- writing to council at Northern Beaches Council, PO Box 82 Manly NSW 1655.

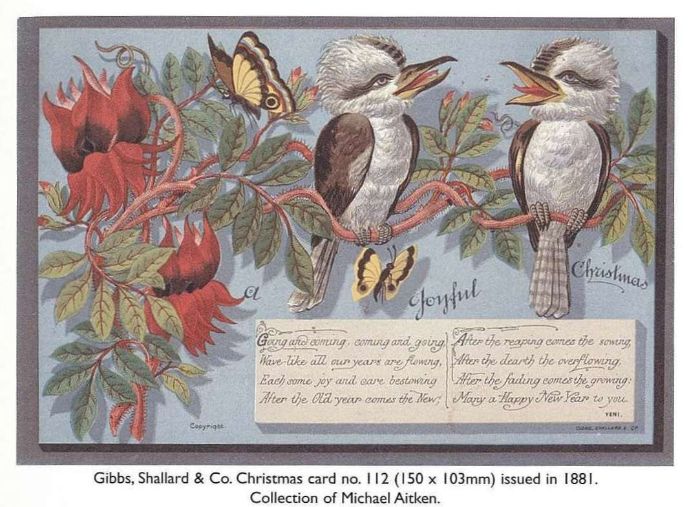

Yardbirds

West Head Lookout Update

- >reinstatement of the previous sandstone paving and the bronze map plinth

- > installation of the stainless-steel balustrade along the lower retaining wall

- > planting of native species in the garden beds.

Norah Head Community Group Has Long Standing Connections

Communities And Industry To Have Their Say As NSW Accelerates Renewable Energy Transition

Next Steps To Beat Plastic Pollution In NSW: Have Your Say

- Are frequently littered or release microplastics into the environment;

- Contain harmful chemical additives; or

- Are regulated or proposed to be in other states and territories.

- Items containing plastic such as lollipop sticks, cigarette butts, bread tags and heavyweight plastic shopping bags are some of the problematic products that could be redesigned or phased out.

Upcoming Workshop With Permaculture Northern Beaches + 2023 AGM + 2023 Raffle

Gardening for a Long Hot Summer

Gardening for a Long Hot Summer

Finding Frogs In Warriewood Wetlands

Creative Christmas: Making Natural Christmas Decorations At Narrabeen + Avalon

Saturday, 2 December 2023 - 10:00 am to 01:00 pm

Saturday, 2 December 2023 - 10:00 am to 01:00 pmJoin The Avalon Christmas Tree Decoration Program

Wakehurst Parkway Update: REF For Proposed Works Available - Feedback Closes December 6

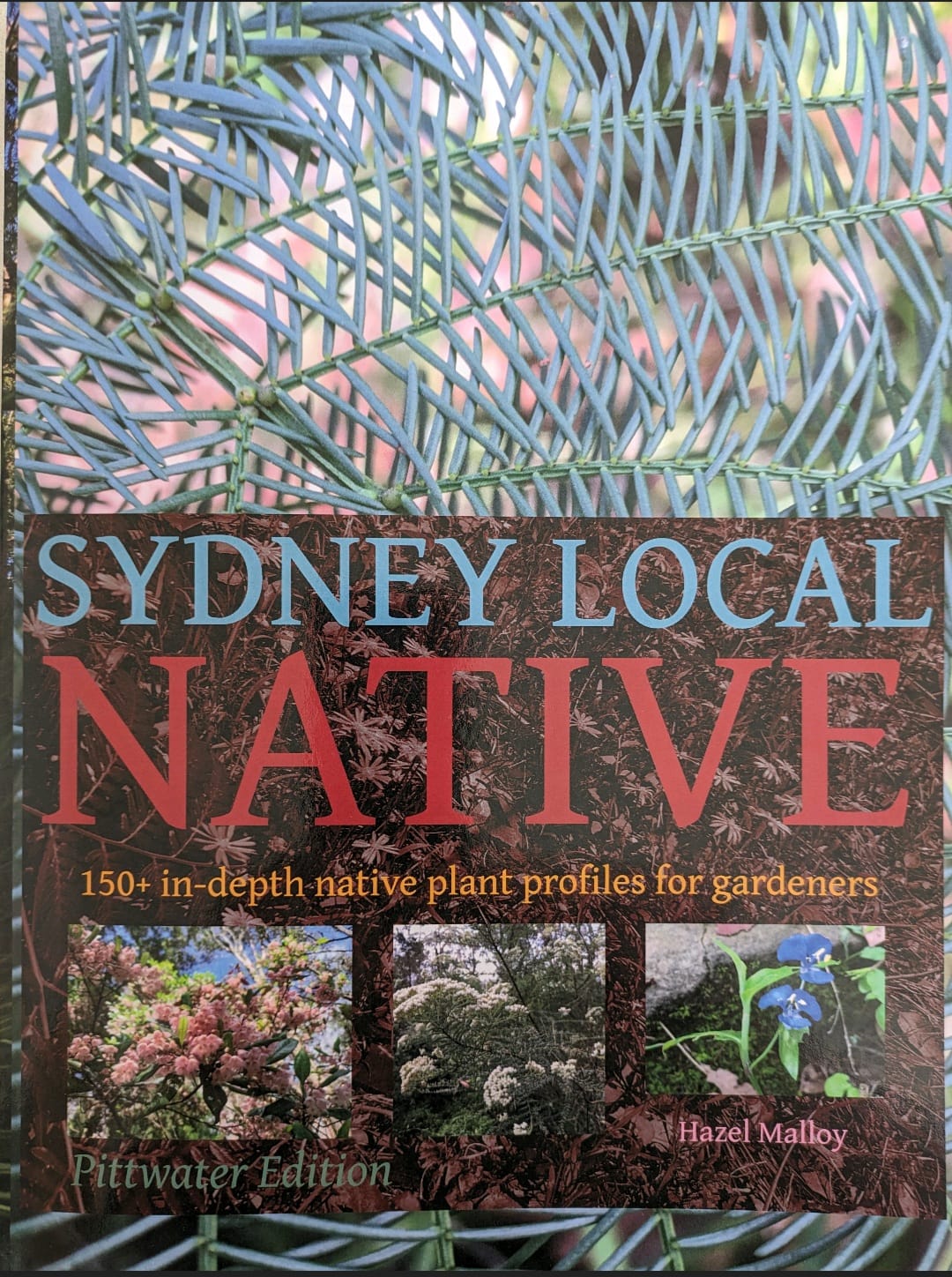

Sydney Local Native: Pittwater Edition Published

- average maximum height and width

- a description of the plant's form

- flower colour and flowering season

- an overview of the plant's best features

- its preferences for soil, water and light

- where it is naturally distributed.

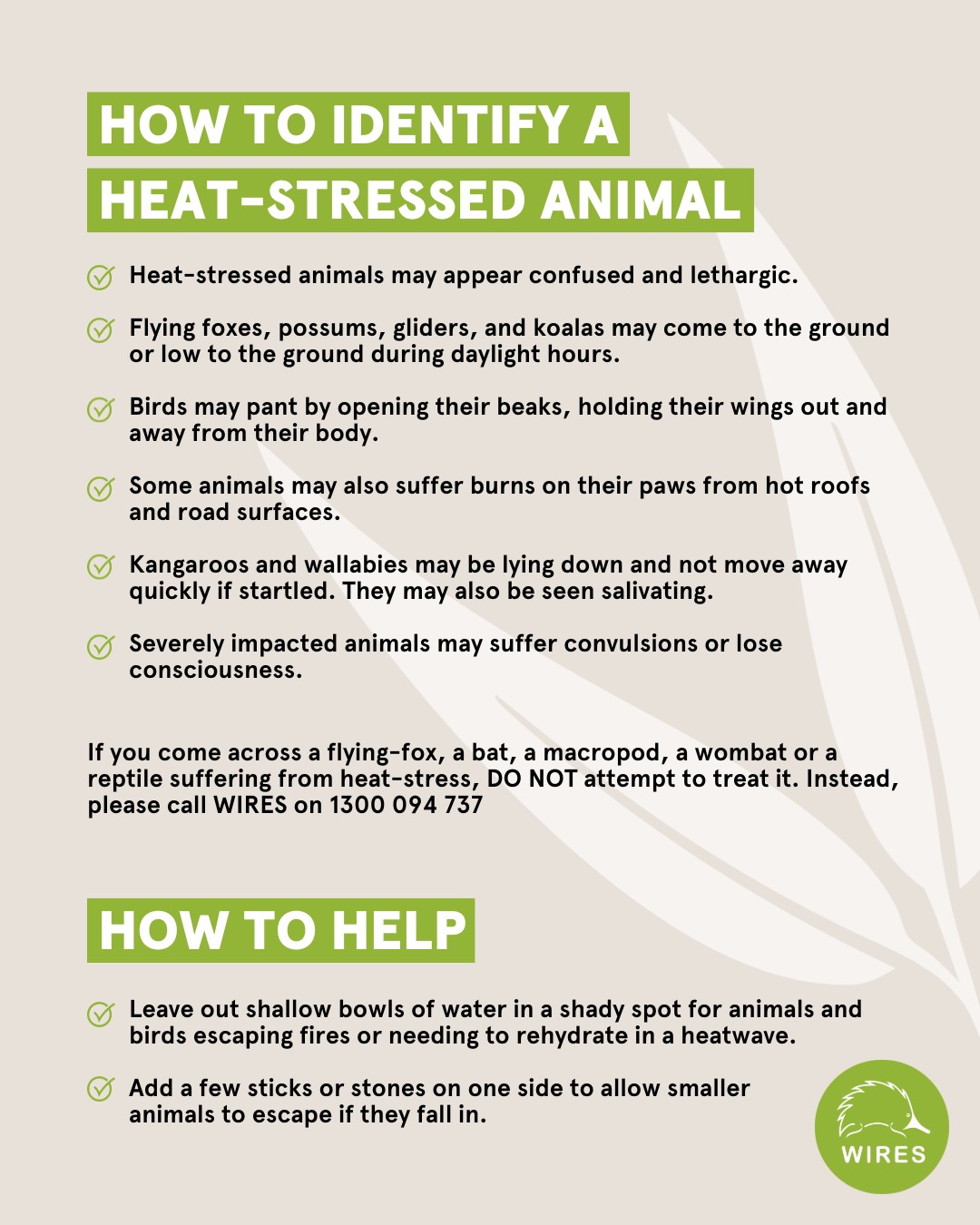

Please Look Out For Wildlife During Heatwave Events

AER Releases Social Licence For Electricity Transmission Directions Paper

- What expectations should be held of transmission businesses in undertaking community engagement

- What outcomes need to be achieved from engagement

- When and how social licence issues can be factored into regulatory tests for the approval of and recovery of cost for new transmission development

- What evidence is needed to justify transmission network expansion and associated expenditure.

- clearly identify the information that is the subject of the confidentiality claim

- provide a non-confidential version of the submission in a form suitable for publication.

Bushwalk Fundraiser

- Friday 8 December

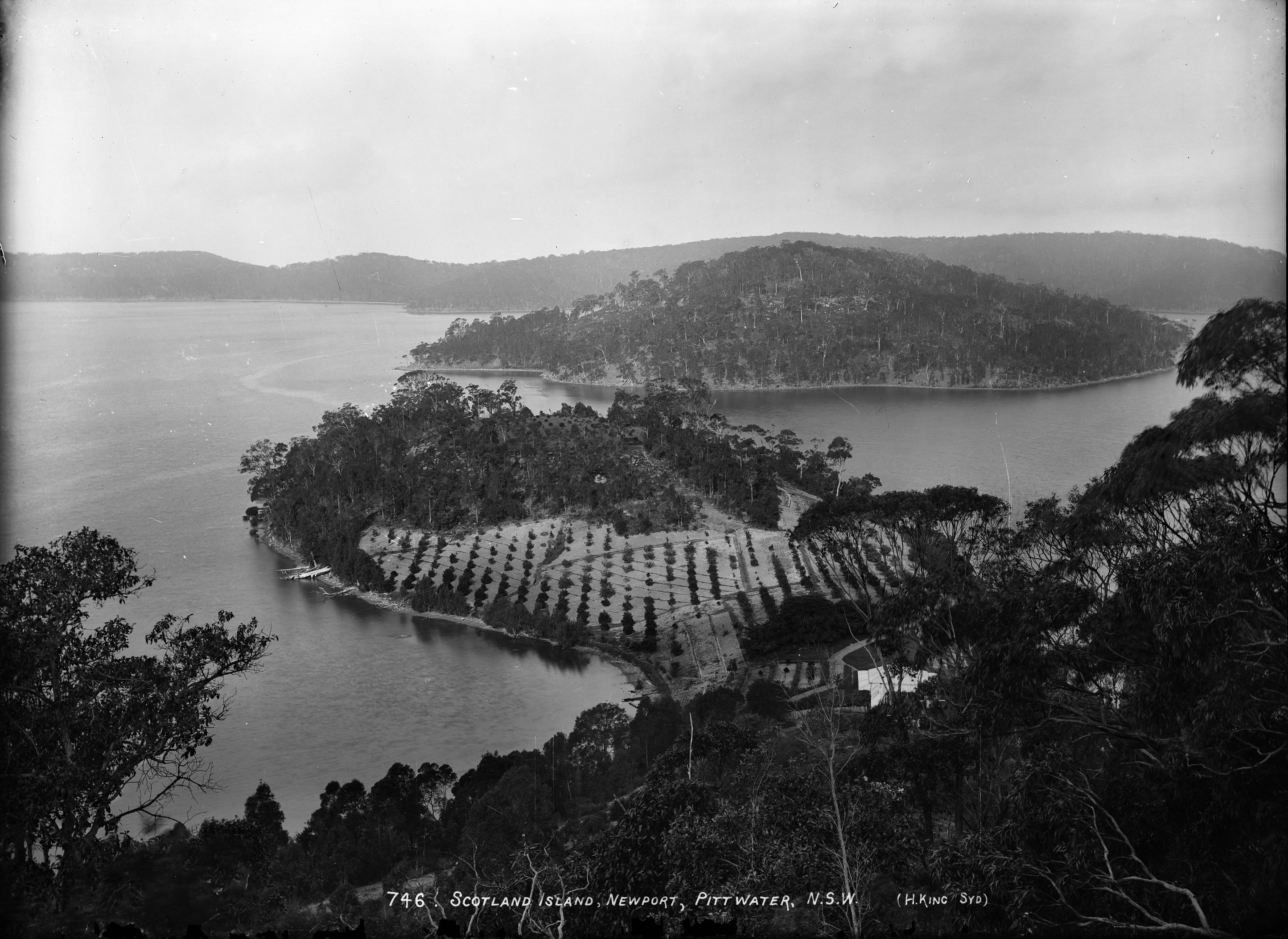

'Scotland Island, Newport, Pittwater, N.S.W.', photo by Henry King, Sydney, Australia, c. 1880-1886. and section from to show cottage on neck of peninsula at western end with no chimneys through roof. From Tyrell Collection, courtesy Powerhouse Museum

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

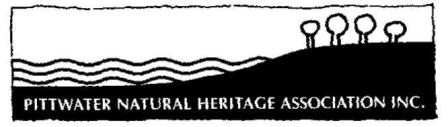

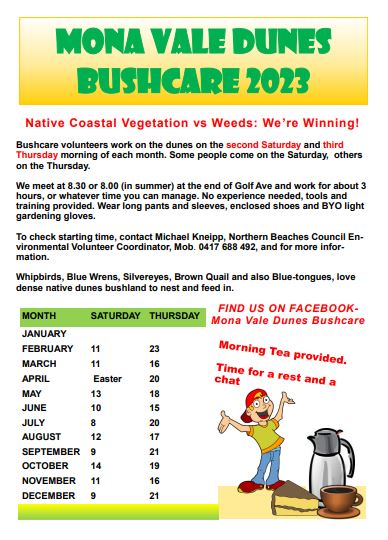

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Australia’s New Nature Positive Laws: Public Webinars On EPBC Act Reforms Run November 23 & 28 - Register Now

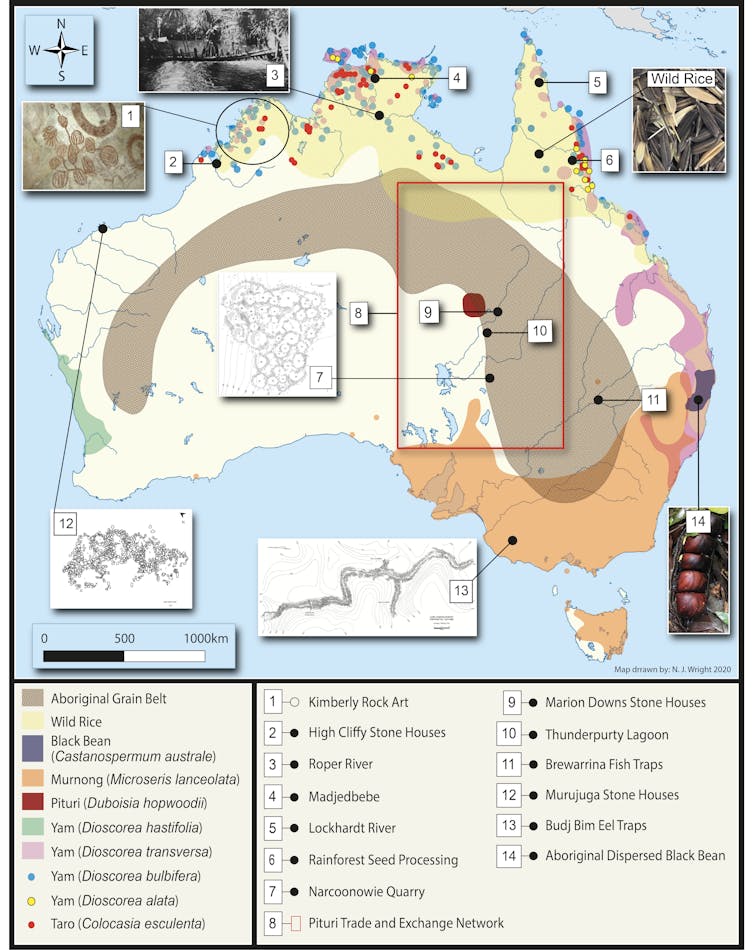

5 things we need to see in Australia’s new nature laws

Australia’s abysmal rates of extinctions and land clearing since European colonisation are infamous globally. Our national environmental legislation has largely failed to protect biodiversity, including many threatened plants, animals and ecological communities. But change is afoot.

The federal government is reforming our national environmental law. Following a scathing review in 2021, the legislation is being rewritten. While amendments to the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) are yet to be tabled in parliament, the government says “rolling consultation” has begun.

About 30 environment, business and industry groups attended “targeted stakeholder workshops” last month. Public consultation begins with two webinars, on November 23 and 28. Government officials are offering to “explain how the proposed changes are designed to work and how they compare to existing laws”. But they are not sharing the draft legislation yet.

How can we assess whether these new laws can prevent further species loss and habitat destruction? Here’s an essential checklist of five things the law must include if we are to avoid calamity and hasten environmental recovery.

1. A Climate Trigger

The EPBC Act does not explicitly discuss and account for climate change and its impacts. So the federal environment minister is not legally bound to consider – or authorised to refuse – new or expanded coal mines and fossil gas fields based on their future climate impacts.

But climate change clearly threatens biodiversity and special places such as the Great Barrier Reef, as well as human communities and culture.

2. Habitat Means Homes For Wildlife

Protection of sufficient and connected habitat must be central to Australia’s national environmental law. If homes for swift parrots, koalas, greater gliders and other threatened species continue to be destroyed and fragmented, it is all but guaranteed Australia will fail in its stated quest to avoid further extinctions.

Northern Australia is home to exceptional but declining biodiversity that is increasingly threatened by development of pastoral, cotton and fracking industries.

Significant increases in land clearing and water extraction are seldom referred under the EPBC Act, let alone assessed.

Environmental law reform must stem the accelerating loss of biodiversity in this region and elsewhere. Reforms must include expanding the water trigger to apply to shale gas fracking, and ensuring significant land clearing is referred and assessed.

It is also crucial that federal approval powers are not devolved to states and territories, particularly in remote regions where so much damage occurs out of sight and out of mind.

3. Setting Clear Objectives And Measuring Outcomes

The new laws must state policy objectives such as no new extinctions and no actions that accelerate climate change.

Decision-makers must be required to address direct, indirect and cumulative threats that undermine these objectives.

The new National Environment Standards (the centrepiece of this law reform) must stipulate red lines not to be crossed, such as no clearing of any critically endangered ecological communities or critical habitat of threatened species.

We should always seek first to avoid harm, then keep harm to a minimum, and only as a last resort, offset remaining impacts – and then only with credible offset plans that fully account for uncertainties in delivering environmental compensation.

4. An Independent Umpire

We need a well-resourced, independent umpire, operating at arms length from government. This “independent cop on the beat” will need powers to prevent activities and developments deemed too harmful for biodiversity.

The government has vowed to create a national Environmental Protection Agency. The functioning and powers of such an entity risk being severely undermined if the environment minister of the day has the ability to “call-in” projects and make unilateral decisions over whether they can proceed. That would also create concern regarding industry influence and pressure on ministers to approve projects.

It’s essential ministers not only have regard for environmental standards but also follow them to the letter of the law.

5. A Voice For Country And Culture

Our national environment laws must make room for genuine Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders participation in how matters of cultural and environmental significance are managed.

Our new nature laws must interact with federal cultural heritage laws, which are also under reform. Entities of cultural significance, such as humpback whales and dingoes, must be cared for in a way deemed appropriate by Indigenous Australians. Such a mechanism must be co-designed with Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders.

Policy must continue to be developed in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people. We suggest a Land and Sea Country Commissioner, “a Voice for Country”, could lead this ongoing collaboration. We also need to ensure groups are adequately resourced and supported to Care for Country.

We Must Do Better

The time has come to lift our ambitions and truly protect our nation’s precious environment and biodiversity.

Australians want effective, urgent action from government. For cultural, social, economic and environmental reasons, biodiversity conservation should be treated as a public good and receive bipartisan support. It’s not an optional extra. We simply must invest in nature. We cannot afford not to.![]()

Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University; Jack Pascoe, Research fellow, The University of Melbourne; Kirsty Howey, , Charles Darwin University; Terry Hughes, Distinguished Professor, James Cook University, and Yung En Chee, Senior Research Fellow, Environmental Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

As school students strike for climate once more, here’s how the movement and its tactics have changed

On Friday, students will once again down textbooks and laptops and go on strike for climate action. Many will give their schools a Climate Doctor’s Certificate signed by three leading climate academics.

These strikes – part of a National Climate Strike – mark five years since school students started walking out of schools to demand greater action on climate change. In 2018, the first students to strike defied calls by then prime minister Scott Morrison for “less activism” and to stay in school.

Last year, Australia voted out the Morrison government, in what was widely seen as a climate election. Teal independents won Liberal heartland seats on climate platforms, while the Greens recorded high votes. Labor came to office promising faster action on climate.

So why are school students still striking? Has the movement changed its focus? We have been researching these questions alongside young people involved in climate action in the ongoing Striking Voices project, as well as through the coauthor’s Sapna South Asian Climate Solidarity project.

We found the movement has expanded its demands from climate action to climate justice, stressing the uneven and unfair distribution of climate impacts. The movement itself has also become more diverse.

From Climate Action To Climate Justice

Across the world, young climate advocates such as those from School Strike 4 Climate are calling for “climate justice” alongside “climate action”.

Why? Because climate change doesn’t impact everyone equally. As the Australian Youth Climate Coalition puts it, it’s “often the most marginalised in our societies who are hit first and worst by climate impacts and carry the burden of polluting industries”.

Mere semantics? No. The idea of climate justice draws attention to existing social and ethical injustices which climate change amplifies. The phrase also points to the need for climate solutions that work for people in a transformative way and help create collective and just societies.

In Australia, calls for climate justice are intimately connected with justice for First Nations people and to protecting, defending and “heal[ing] Country”, as Seed Mob write, with First Nations-led solutions.

Climate justice is central to the messaging of groups such as Pacific Climate Warriors diaspora, and Sapna South Asian Climate Solidarity.

In our conversations with young people, climate justice appears highly compelling. High-school student Yehansa Dahanayake explained:

I think I’d always thought of climate change as sort of a 2D thing. I thought about it as the temperature rise, deforestation, and sea caps melting - and while that is definitely true, I think [when] I started to learn about the justice aspects of climate change, [it] made me realise that there are many other factors that tie in, such as the Global North/ Global South difference and how that relates.

High-school student Emma Heyink told us about the importance of what she called a “justice-centred lens”:

You can’t look at climate change without looking at all these other issues. It just becomes so much more interlinked and solutions become so much more obvious.

Diversifying Networks And Strategies

So who are these young people, and what have they been doing in recent years?

Swedish student Greta Thunberg is frequently credited as sparking the youth-led climate movement.

But the movement is much larger – and more diverse – than one person, and increasingly so in recent years.

As a report by Sapna points out, Australia’s youth-led climate justice networks are more likely to be racially diverse than mainstream climate movements.

Yet climate justice networks are not immune from the oppressive dynamics they protest against. When the coauthor interviewed 12 now-graduated school strikers of South Asian heritage, they reported sometimes feeling sidelined in climate spaces – which are often white-dominated – as well as in media opportunities. As one young person put it, it seemed “hard to tell a brown person’s climate justice story”.

There are signs of positive change. The upheaval of the COVID pandemic saw stronger connections emerge between social movements, and clearer links between intersecting crises and injustices, both globally and in youth-led climate networks.

As recent high-school graduate and school strike organiser Owen Magee explained:

at our strikes, we are platforming First Nations people, rural and regional people who’ve directly been affected by the climate crisis, directly being affected by fossil fuel greed and corporation greed. That in itself is focusing on the intersectional nature of climate justice.

You can see this cross-pollination in the support shown by young advocates across multiple climate justice networks in the Power Up gathering on Gomeroi Country in northwestern New South Wales to show solidarity with Traditional Owners fighting coal and gas projects on their lands.

The targets and tactics of youth-led climate justice networks have shifted and proliferated in recent years - for example, to the banks that finance fossil fuel companies.

When school strikers graduate, some move into different modes of climate-related action.

Some have taken part in strategic climate litigation in a bid to create legislation embedding a climate duty of care for young people in government decisions on issues such as fracking approvals.

Others are involved in non-violent direct actions, such as next week’s Rising Tide People’s Blockade of the world’s largest coal port in Newcastle.

Young climate advocates are battling for climate justice on a wide range of fronts. They are calling on politicians to do the same.

We would like to acknowledge and thank the Striking Voices project research associates, Natasha Abhayawickrama, Sophie Chiew, Netta Maiava and Dani Villafaña.![]()

Eve Mayes, Senior Research Fellow in Education, Deakin University and Ruchira Talukdar, Casual senior research fellow, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How could Australia actually get to net zero? Here’s how

Every bit of warming matters if we want to avoid the worst impacts for climate change, as the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change shows.

In 2020, we released modelling showing how Australia could get to net zero faster – and keep the Paris Agreement goal of holding warming to 1.5°C in play. Our new update shows this is still the case.

This week, we released our latest modelling based on cutting emissions in line with the 2015 Paris Agreement, which set an upper limit on warming of well below 2°C, with a commitment to strive for the lower harm limit of 1.5°C.

At present, the government’s 2030 goal is a 43% reduction from 2005 levels, with plans to set a further target for 2035 soon. Our new modelling of 1.5°C and well-below-2°C (1.8°C) pathways shows we must increase the pace of emissions cuts to between 48–66% for 2030 and 61%–85% for 2035.

This means Australia would reach net zero emissions by 2039, around a decade sooner than the current target of net zero by 2050. Our research shows this is possible.

So How Do You Actually Do This?

In July, the government announced the development of net zero plans for six sectors: electricity and energy, industry, built environment, agriculture and land, transport and resources. Treasurer Jim Chalmers recently said the government is preparing an ambitious policy agenda with big spending on green industries to help cut emissions, and to grow the economy as reliance on gas and coal falls.

These plans are now under development. Our modelling of these sectors shows which ones must cut emissions fastest – and how to do it for the least cost.

Electricity: In these 1.5°C and well-below-2°C least-cost scenarios, the electricity sector reaches near zero between 2034 and 2038. Renewable energy is already the least-cost way to generate power. In turn, clean electricity can help decarbonise the rest of the economy.

Industry and resources: In our scenarios, industrial emissions fall by 42% (well-below-2°C) or 54% (1.5°C) by 2035. By 2050, they fall by 54% and 67% respectively. Earlier and faster electrification and uptake of hydrogen technologies through the 2020s and 2030s drives more emissions reductions in the 1.5°C scenario.

Buildings: Rapid emissions reductions in the building sector come from electrification and improvements in energy performance in both scenarios. Housing energy efficiency improves by 41% by 2050 compared to today’s levels.

Agriculture and land: Cutting emissions in line with the 1.5°C goal will require much more removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, mainly through sequestration in trees or soil. This can happen without damaging agricultural production.

How much CO₂ we need to pull from the air depends on our ambition. For the well-under-2°C scenario, we need to remove 1.4 billion tonnes (1.4 Gt). For 1.5°C, it’s 4.6 Gt. Farming emissions such as methane from livestock and nitrous oxide from fertilisers will take longer to cut, as emissions per, say, kilogram of beef falls while production increases overall. Adding algae to livestock feed and rolling out slow and controlled-release fertilisers may help lower emissions here.

Transport: Without strong action on transport, emissions will keep growing. Both scenarios show minimal change in total transport sector emissions until 2030. That’s because steady increases in vehicle use as our population and economy grows will prevent overall reductions – even as people go electric.

Under both scenarios, the transport sector changes markedly. Electric vehicles (EVs) become dominant, making up 73% of new car sales under the 1.5°C scenario or 56% in the well-below-2°C scenario. Our modelling doesn’t account for the additional potential benefits of shifting trips from cars to public transport, or from road to rail freight.

For Most Sectors, Net Zero Relies On Clean Electricity

Our modelling suggests it’s most cost effective for Australia to rapidly switch fossil fuel electricity to renewable sources and push beyond the current 82% clean energy target by 2030. We should instead aim for between 83 and 90%, and almost 100% by 2050.

Coal-powered electricity generation disappears before 2035 in our 1.5°C scenario, and by late 2030s in our well-below-2°C scenario. Gas-powered electricity falls sharply around the same time period.

By 2050, gas-fired power stations would contribute less than 1% of total generation, only firing up briefly to firm electricity supply to the grid.

Under both the 1.5°C and well-below-2°C scenarios, Australia’s electricity generation increases markedly. Renewable-powered electricity generation in 2030 would be greater than the total amount of electricity generated in 2020. By 2050, it is more than three times as great.

The Rise Of Hydrogen For Hard-To-Tackle Sectors

Support for green hydrogen has soared in recent years, both internationally and locally through government programs such as Hydrogen Headstart.

Why the change? Because of its potential uses in hard-to-green sectors. Industrial processes such as steelmaking rely on high temperatures. Traditionally coal has been used, but hydrogen is emerging as an alternative. It may have a role in transport, through fuel-cell vehicles, and to replace gas in those industries that rely on high-temperature heat.

Neither of our modelled scenarios show a role for hydrogen in buildings, passenger transport or short-haul freight. That’s because electrifying homes and using battery-electric vehicles is cheaper and more market-ready.

But our modelling shows hydrogen can play a role in industry, long-haul freight and maritime shipping – if it becomes commercially viable for these sectors.

In our scenarios, domestic hydrogen demand grows to between 383 and 465 petajoules by 2050 – around 12–16% of Australia’s energy demand.

Time Is More Precious Than Ever

Our latest analysis shows a 1.5°C least-cost pathway would see Australia reach net zero more than a decade earlier than the current goal of 2050.

If Australia and the rest of the world can cut emissions in line with the Paris Agreement goals, a safer and more prosperous future awaits.

But it’s only possible if Australia acts quickly, builds on the momentum towards net zero and seizes the enormous opportunities offered in fast decarbonisation.![]()

Anna Skarbek, CEO, Climateworks Centre; Anna Malos, Climateworks Centre - Country Lead, Australia, Monash University, and Michael Li, Research and Analysis Manager, Climateworks Centre, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Murray-Darling water buybacks won’t be enough if we can’t get water to where it’s needed

Avril Horne, The University of Melbourne and Andrew John, The University of MelbourneWhen it was clear the Murray-Darling Basin Plan could not be completed on time, Federal Water Minister Tanya Plibersek announced a new agreement (without Victoria) to deliver in full the plan’s aim of restoring the health of this vast river system.

The new agreement required changes to the Water Act to allow more water for the environment to be purchased from irrigators (water buybacks). Concerns about these changes prompted a Senate inquiry.

The report from that inquiry, released on Friday, supports buybacks but also makes key recommendations to remove “constraints” to water delivery. These are physical constraints or limits to the movement of water through the river system. Managers can only deliver so much water before it spills out of the river onto private land.

The report goes so far as to ask whether constraints should be removed before more water is recovered. This is a question we have been asking in our research. And our results suggest the answer is yes.

Currently, we cannot physically deliver all of the water recovered from other uses for the environment (known as environmental water) to where it’s needed without flooding private property along the way. And the government is not prepared to do that.

Basin Health Is Improving But Challenges Remain

Under the Basin Plan, about 20% of water used for irrigation a decade ago is now used for environmental purposes. This has improved river health, encouraging fish to spawn and plants to grow, and reduced salt levels in the Lower Lakes and Coorong.

These benefits rely on the river’s flow regime, not just the annual volume. Higher flows inundate wetlands, move sediment down the river, and provide natural triggers for various species to breed or migrate.

But raising water levels in the river channel isn’t enough to get environmental water everywhere it’s needed. Sometimes larger flows are required. Unfortunately, sending more water down the river runs the risk of inundating private property or damaging infrastructure such as low-lying pumps on floodplains.

Restoring the river’s health requires not only recovering water but also completing projects that allow more of this water to flow despite physical constraints such as a narrow stretch of river. These projects might involve modifying or improving infrastructure such as low-lying roads and bridges, as well as working with communities to limit damage and compensate for flooding of private property.

The Senate inquiry report highlights the challenges for these projects. It also supports improving the approach to delivering these projects across the southern basin.

Challenges, Priorities And Solutions May Differ

Our research on the Goulburn River in Victoria’s part of the Murray-Darling Basin shows recovery of additional water for the environment does not guarantee environmental outcomes.

This is because the amount of water that can be sent down the river is constrained. So having more environmental water at your disposal does not help, because it is physically impossible to get all the water to where it is needed, when it is needed, without risking inundation of private property.

Current river system operations, including rules and physical constraints, prevent the full volume of environmental water held in Goulburn River being delivered at the right time and in the right way to achieve the best environmental outcomes.

Narrow sections of the river and adjacent private development limit releases from Lake Eildon. River managers are not allowed to deliberately inundate the floodplain if it risks private property.

So the volume of environmental water available in the Goulburn River is not the issue – delivering this water is the challenge. In this regard, Victoria’s refusal to sign up to the new basin deal is understandable, because more water buybacks would potentially cause more pain to the local community than gain to the local environment.

However, neither Victoria nor New South Wales has addressed these capacity constraint issues, significantly limiting the ability to get better environmental outcomes with less water. So the challenge is much more complex than simply redistributing entitlements and buying back environmental water.

The Elephant In The Room: Climate Change

Temperature, rainfall and streamflow have already changed in parts of the Murray-Darling Basin. Over the coming decade these changes will become more pronounced, widespread and entrenched, causing more frequent floods and droughts.

While the precise consequences for water availability remain to be seen, the impact on the basin will be immense.

But climate change simply adds to the need to have difficult conversations around the future of communities along the Murray-Darling. Focusing on whether buyback targets have been achieved does not resolve this. In many regions, there will not be enough water, with or without buybacks, to achieve current management objectives.

Buybacks should be placed in the context of this imminent threat. In rivers like the Goulburn, addressing capacity constraints provides the single best climate adaptation option to improve environmental outcomes in the short and medium term.

Removing these constraints would allow more water onto the lower Goulburn River floodplain, with due care for land and infrastructure that could be affected. For example, projects may offer landholders options to avoid or compensate for any water damage and associated costs.

This is because removing constraints gives river managers more flexibility, which can increase the resilience of the environment to a wider range of future climates. More water from buybacks provides very limited additional benefit because it doesn’t change how environmental water can be delivered.

The senate report emphasises the need to embed consideration of climate change in the Water Act and Basin Plan. The decisions we are making now on water recovery and constraints relaxation will have big impacts on communities.

Our work shows considering climate change is essential to ensuring lasting benefits and resilient outcomes for the rivers and communities that rely on them.

The first basin plan took a big step towards sustainable management of the vast Murray-Darling river system. But it was always meant to be the first step in an adaptive policy process. Priorities and solutions will look different across the basin. We need a holistic approach where buybacks may very well be part of the solution, but are not the whole solution. We also need to ensure we can deliver this water where and when the environment needs it. ![]()

Avril Horne, Research fellow, Department of Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne and Andrew John, Research fellow, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COP28: a year on from climate change funding breakthrough, poor countries eye disappointment at Dubai summit

Lisa Vanhala, UCLAt the COP27 summit in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, an agreement to establish a loss and damage fund was hailed as a major breakthrough on one of the trickiest topics in the UN climate change negotiations. In an otherwise frustrating conference, this decision in November 2022 acknowledged the help that poorer and low-emitting countries in particular need to deal with the consequences of climate change – and, tentatively, who ought to pay.

This following year has seen more extreme weather records broken. Torrential rains created flooding which swept away an entire city in Libya, while wildfires razed swathes of Canada, Greece and the Hawaiian island of Maui.

As these events become routine worldwide, the case grows for an effective fund that can be set up quickly and help those most vulnerable to climate change. But after a year of talks, the fund has, so far, failed to materialise in the way that developing countries had hoped.

I’m writing a book on UN governance of loss and damage, and have been following the negotiations since 2013. Here’s what happened after the negotiators went home and what to watch out for when they return, this time at COP28 in Dubai.

Big Questions

Many questions were raised and left unresolved in Sharm El-Sheikh. Among them: who will pay into this new fund? Where will it sit? Who will have power over it? And who will have access to the funding (and who won’t)?

A transitional committee with 14 developing country members and 10 developed country members was appointed by the UN to debate these questions after COP27. The committee has met regularly over the last year, but at its fourth meeting at the end of October – scheduled as the last session – important questions surrounding the fund, such as who should host and administer it, remained. Discussions broke down without an agreement.

In early November, less than a month before COP28, a hastily arranged fifth meeting presented committee members with a text cobbled together by the two co-chairs from South Africa and Finland as a take-it-or-leave-it agreement. Developing countries agreed to having the fund hosted by the World Bank for an interim period, despite reservations.

Developed countries also objected to the final text. The US wanted to add the adjective “voluntary” to any mention of contributions to the fund. Others argued that the pool of contributors to the fund should be widened to include some developing countries, such as Saudi Arabia, and also private sources of finance. These objections were noted but the text was adopted without them.

These recommendations must now be signed off at COP28, which begins on November 30. With almost 200 countries having to reach agreement on these arrangements and dissatisfaction widespread, the process isn’t likely to be straightforward.

The World’s Bank?

Developing countries have been sceptical of the World Bank as a potential host of the fund for several reasons.

Many delegates worry about the bank’s reputation, including the dominance of developed country donors, its emphasis on providing loans rather than grants, and the lack of climate-savviness in the bank’s operations. These concerns are likely to reemerge in Dubai.

The US is the biggest shareholder in the World Bank and traditionally, the bank’s president has been a US citizen nominated by Washington. Small-island developing states (among the most vulnerable to climate change due to sea-level rise) have argued for moving the fund away from a donor-recipient model, with all their usual power imbalances, towards a partnership founded on a shared commitment to protecting the planet.

This will require partial or total reform of the World Bank – and some argue this is already happening under its new president. But hosting the fund within the bank would still give donor countries disproportionate influence, despite recommendations by the transitional committee that the fund’s governing board be composed of a majority of developing country members.

High overhead costs are another concern. One board member of another fund hosted by the World Bank has suggested that the administrative fees the bank charges are rising and absorbing a larger share of aid. This could mean that, for every US$100 billion offered to countries and communities reeling from disaster, the World Bank will keep $US1.5 billion. This will be hard for an institution still funding the climate-wrecking oil and gas industry to justify.

The types of finance made available by the fund will need to be at odds with the bank’s traditional mode of loan financing, by offering grants and other forms of highly concessional lending. Developing countries have consistently argued that loss and damage funding should not increase a developing country’s debt burden.

The agreed text says the loss and damage fund will “invite financial contributions”, with developed countries expected to “take the lead”. Developing countries want developed nations (as the largest historical emitters) to provide funding, but rich nations have pushed back against any notion that they have an obligation to pay.

Rather, while making all the right noises on climate finance, they may gain short-term kudos by simply rebranding existing forms of climate finance or development aid, rather than offering any new money.

The Compensation Taboo

One thing you’re unlikely to hear at COP28 is “compensation”. While newspaper editors love headlines about reparations, liability and compensation when reporting on loss and damage, and a rise in climate litigation is making governments and polluting companies nervous, this language is still totally absent in discussion of the issue in the negotiations.

In fact, research has shown that mentions of compensation in state submissions to the UN declined dramatically after the establishment of the mechanism on loss and damage in 2013. The fine print of the 2015 Paris Agreement noted that loss and damage was “not a basis for liability or compensation”.

I have noticed a taboo emerging around the term within the COP process. Instead, countries are increasingly opting for language such as “solidarity” as the basis for finance. These word choices show where power lies.

All of this is to sound a note of caution going into COP28. Major agreements on loss and damage have historically not lived up to their promises due to bureaucratic forum-shifting (moving topics to venues outside of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change), delays, and under-resourcing. The adaptation fund was established in 2001 but only approved its first funding in 2010.

How is the urgent need for support among vulnerable communities and countries going to be met when the pace of progress within the climate change negotiations is glacial at best, and tends to be particularly slow and unambitious on loss and damage finance?

At COP28, making the loss and damage fund real is a litmus test for the legitimacy of the entire climate change negotiation regime.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Lisa Vanhala, Professor of Political Science, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

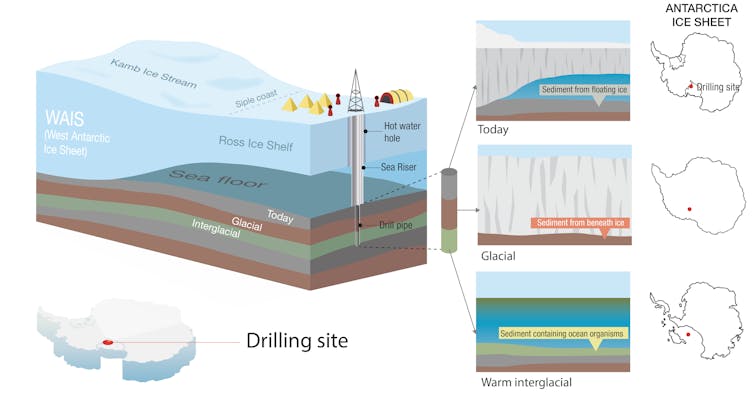

We can still prevent the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet – if we act fast to keep future warming in check

Projecting when and how fast the West Antarctic Ice Sheet will lose mass due to current and future global ocean warming – and the likely impact on sea level rise and coastal communities – is a priority for climate science.

We know deep water flowing towards and around Antarctica is warming, and the fringes of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) are increasingly vulnerable to ocean-driven melting.

Submerged continental shelves along large portions of West Antarctica, including offshore Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers in the Amundsen Sea, are already bathed by upwelling arms of this relatively warm water.

Ice shelves in this region – massive floating slabs of ice that flow out from the coast – are already losing mass. Because ice shelves float, their melting doesn’t affect sea levels. But they hold back land-based ice, which does.

Recent research suggests increasing flow of warm deep water in this area will speed up the melting of the WAIS over the coming decades, regardless of future anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

This would mean global net-zero emissions targets cannot limit the amount of future sea-level rise caused by the melting of the WAIS. This poses significant challenges for coastal communities in low-lying regions as they plan for and adapt to unavoidable change.

Our project, an ambitious international collaboration known as the “Sensitivity of the WAIS to 2°C” (SWAIS2C), aims to retrieve sediments from the seafloor beneath the Ross Ice Shelf to explore how West Antarctica responded to warmer periods in Earth’s past – and what might happen in a warming future.

We May Have (Some) Time

While it may appear too late to slow or stop the retreat of the WAIS in areas where the ocean cavities beneath ice shelves are already “warm”, the inevitable demise of the entire WAIS is not so certain. There are also regions where ice shelf cavities are currently “cold”.

The Ross and Ronne-Filchner are Earth’s largest ice shelves and currently buttress and stabilise large regions of ice in the West Antarctic interior. The ocean cavity that lies beneath the Ross Ice Shelf is cold, generally characterised by temperatures at or below minus 1.8°C.

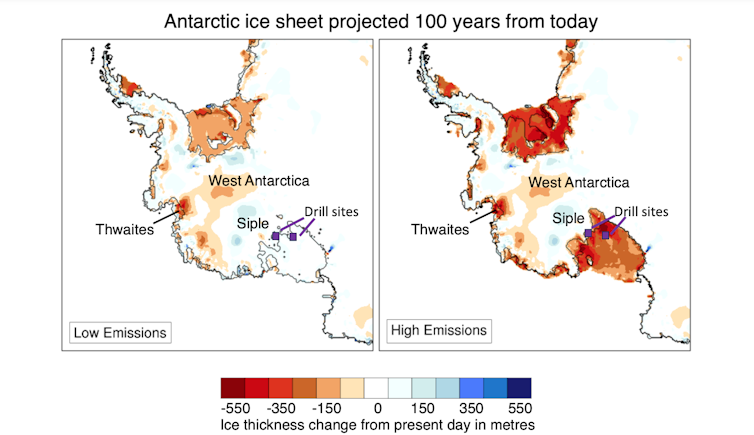

A recent ice sheet modelling study shows these large ice shelves and the WAIS will remain largely intact under low-emissions pathways which aim to keep warming close to or below 2°C above pre-industrial values.

Modelling experiments indicate an emissions pathway in line with the goals of the Paris agreement can still limit the total contribution to sea level rise coming from the Antarctic ice sheet to 0.12–0.44 metres by 2100 (0.45–1.57 metres by 2300).

Importantly, these experiments also show that spatial patterns of ice thinning and retreat in the Amundsen Sea region are similar for 2100 compared to 2015 (see figure below) under both low and high emissions.

The clearest contrasts between the scenarios occur in the Ross Sea sector, where the grounding line of the ice shelf advances in low-emissions (“sustainable”) scenarios but the shelf ice thins or even collapses in high-emissions (“fossil fuel intensive”) scenarios.

Observation Gaps From Key Antarctic Regions

Global surface temperature is likely to exceed 1.5°C above pre-industrial values by the early 2030s. It may warm by as much as 4.4°C by the end of this century.

Our current global policy and action trajectory will yield 2.7°C of warming by the end of century, but more ambitious pledges and targets could keep global warming to 2.0°C. We need to know how sensitive the large, cold-cavity ice shelves are to these increases in global temperature.

Ice sheet modelling suggests rapid cuts in emissions can still limit WAIS melt, but we lack direct observations to support these findings. Collecting new data from locations around the WAIS margin will offer insights into present-day changes and a possible future response to warming.

Significant effort to address data gaps has been made in the Amundsen Sea around the Thwaites Glacier region, but observations beneath the Ross Ice Shelf, especially near the point where the WAIS begins to float, are limited. The SWAIS2C project aims to address this knowledge gap.

Tapping The Geological Record

SWAIS2C is an international collaboration involving scientists, drillers, engineers and science communicators. Our team will travel to the Siple coast, close to the centre of West Antarctica, to melt holes through the ice shelf at two sites.

Oceanographic measurements and geophysical observations at each site will improve our understanding of current ocean mechanics and ice sheet dynamics. But to understand the potential future contribution to sea-level rise from melting of the WAIS, we will need to turn to the geological record.

Seafloor sediments from beneath the Ross Ice Shelf represent an archive of climate information from warmer periods in Earth’s history and offer a means to “see” how the ice shelf and ice sheet responded to past warmth.

We will drill up to 200 metres below the seafloor to recover a geological record of changing rock types that reflect environmental conditions at the time they formed.

These data will allow us to identify previous episodes when the ice shelf thinned and disintegrated, driving retreat of the WAIS interior. Environmental data from these intervals will identify the regional climatic conditions that drove this retreat and help determine the sensitivity of the system to increases in global mean temperature.

SWAIS2C builds on other successful international scientific drilling programmes in the Ross Sea region, including ANDRILL and IODP and is supported by ICDP.![]()

Richard Levy, Principal Scientist/Environment and Climate Research Leader, GNS Science; Dan Lowry, Ice Sheet & Climate Modeller, GNS Science; Denise Kulhanek, Professor of Marine Micropaleontology, University of Kiel; Gavin Dunbar, Senior Lecturer in Palaeoclimate, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington; Huw Joseph Horgan, Research Scientist, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich; Molly Patterson, Assistant Professor in Geology, Binghamton University, State University of New York; Nick Golledge, Professor of Glaciology, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington, and Tina van de Flierdt, Professor of Isotope Geochemistry, Imperial College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s offer of climate migration to Tuvalu residents is groundbreaking – and could be a lifeline across the Pacific

Jane McAdam, UNSW SydneyFor many years, I have been calling for the Australian government – along with other governments – to play its part in assisting Pacific communities affected by the adverse impacts of climate change and disasters.

Our region is already experiencing some of the most drastic effects of climate change. Pacific communities are showing enormous innovation and resilience in the face of these challenges, but as a matter of international solidarity and climate justice, additional support and cooperation is needed.

One way of providing assistance is by creating migration pathways for people who wish to move. Australia’s recent Pacific Engagement Visa is one such example – enabling up to 3,000 workers and their families from the Pacific and Timor-Leste to migrate permanently to Australia each year.

In addition, the announcement this week of an Australia–Tuvalu Falepili Union Treaty is groundbreaking. Under this deal, Australia will provide migration pathways for people from Tuvalu facing the existential threat of climate change. It is the world’s first bilateral agreement on climate mobility.

How The New Visa Program Will Work

Based on the principles of “neighbourliness, care and mutual respect”, the treaty is a result of a request by Tuvalu for Australia to support and assist its efforts on climate change, security and human mobility.

According to Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, “developed nations have a responsibility to provide assistance” to countries like Tuvalu that are deeply impacted by climate change.

Under the treaty, Australia will implement a special visa arrangement to allow Tuvaluans to work, study and live in Australia. This is not a refugee visa, but rather will allow up to 280 Tuvaluans (from a population of around 11,200) to migrate to Australia each year – presumably on a permanent basis.

They will be able to access Australian education, health care, and income and family support on arrival. This is a welcome development that will provide people with both legal and psychological security. Despite longstanding “promises” that Australia would not sit by as disasters continue to affect the Pacific, this program provides the long-awaited security that many have wanted.

Historically, most Pacific visa programs in Australia (and the region) have been tied to labour mobility. And none has specifically referenced climate change as a driving rationale. In contrast, the measures announced this week are deliberately framed in the context of climate change and – furthermore – are not tied purely to work.

Indeed, it remains to be seen just how far the special visas may extend. Beyond “work” and “study”, the treaty says Tuvaluans can also come to Australia to “live”. This implies the visa may potentially provide a humanitarian pathway for people who want – or need – to move. This would include older people, who would not qualify for existing Pacific labour migration programs.

Despite the threats posed by climate change, however, most Pacific peoples do not want to leave their homes. Being dislocated from home is one of the greatest forms of cultural, social and economic loss people can suffer. It can often lead to inter-generational trauma.

The treaty itself recognises Tuvaluans’ “deep, ancestral connections to land and sea”, and pledges Australia will work with Tuvalu to help people “stay in their homes with safety and dignity”. At the same time, people want to know they have safe options to move if they need to – with dignity and choice.

How Novel Is The New Treaty?

While there are other programs in the Pacific that facilitate mobility, this is the first to do so specifically in the context of climate change. It also operates differently from arrangements implemented by New Zealand and the United States.

As part of the “realm” of New Zealand, for instance, people from the countries of Niue, Tokelau and Cook Islands are considered New Zealand citizens, so they have the right to move there if they wish.

New Zealand has also long had its “Pacific Access” visa category and the Samoa quota resident visa, which together enable around 2,400 people to move from the Pacific to New Zealand on a permanent basis each year.

The United States, meanwhile, has compacts of free association with the Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia and Palau, which enable eligible citizens to enter the US visa-free and live and work there indefinitely. However, those migrants do not have access to many government benefits and can easily fall through the cracks.

Last year, Argentina announced a special humanitarian visa program for people displaced from 23 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean due to disasters. Unlike the Australia–Tuvalu treaty, which allows for migration in anticipation of climate-related disasters, access to the Argentinian program is only available after displacement has occurred. As yet, no one has used the scheme.

For at least two decades, Pacific governments have made perennial requests for special visa pathways or relocation to Australia for their citizens.

In 2019, former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd proposed that Australia accept people from Tuvalu and other Pacific countries on account of projected climate impacts – but in exchange for “their territorial seas, their vast exclusive economic zones, including the preservation of their precious fisheries reserves”.

He was shot down by the then-prime minister of Tuvalu, Enele Sopoaga, who labelled it “imperial thinking”.

What Could Come Next?

Last week, Pacific Leaders endorsed a world-first Pacific framework on climate mobility, which has gone relatively unnoticed, despite the Australia–Tuvalu announcement.

I had the privilege of working and consulting with Pacific governments and communities to draft the early versions of the framework. It will hopefully inspire the creation of further visa arrangements and other concrete mobility mechanisms to ensure Pacific peoples have dignified pathways to move when they wish, as well as support and assistance to remain in place when possible.

Earlier this year, Samoan Prime Minister Fiame Naomi Mata’afa suggested the Pacific could create a European Union-like entity, “based on cooperation and integration”, that would enable free movement across the region.

If enacted, it would follow a similar agreement signed by leaders in eastern Africa that specifically allows people in that region to cross borders in anticipation of or in response to disasters.

Though this is still a long way off in the Pacific, the agreement between Australia and Tuvalu could help pave the way for similar mobility pathways across the region and – ultimately – a broader regional scheme. If, and when, that time comes, the choice, agency and dignity of affected communities must be front and centre.![]()

Jane McAdam, Scientia Professor and Director of the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Here’s how a TV series inspired the KeepCup revolution. What’s next in the war on waste?

Changing habits can be hard. So when a single episode of an Australian television show prompted a national shift in behaviour, as behavioural researchers, we took notice.

The first (2017) and second (2018) seasons of the ABC TV program War on Waste reached audiences of 3.8 million and 3.3 million viewers, respectively. That’s one in seven Australians. It inspired action, slashing the waste footprint of hundreds of Australian organisations. So it remains a valuable example of TV driving social change, and one we can still learn from today.

Through focus groups conducted in 2018, we explored how the first season encouraged Melbourne millennials’ to adopt reusable coffee cups. Then, when the COVID pandemic prompted greater use of disposable consumer products, we revisited the data and delved deeper into behavioural science.

Our analysis revealed people were drawn to the engaging storytelling, confronting visuals and prankster ex-Chaser host Craig Reucassel. He demonstrated, step-by-step, how to minimise waste in a relatable and guilt-free way. Our research, recently published in the journal Communication Research and Practice, can guide others to achieve similar success in behavioural change.

Educational Entertainment

In War on Waste, Reucassel confronts Australia’s many waste-management problems and potential solutions.

The series is an example of what behavioural psychologists call “entertainment-education interventions”.

In one episode, Reucassel staged a stunt on a Melbourne tram during peak hour, proclaiming it was filled with 50,000 disposable coffee cups – the amount sent to landfill every 30 minutes in Australia.

Almost overnight, KeepCup sales quadrupled, crashing the company’s website. Membership of a Responsible Cafes initiative promoting reusable coffee cups spiked from 400 cafes to 1,800.

An ABC study found more people of all ages bought coffee in reusable cups after War on Waste aired (up from 37% to 42%).

The survey also revealed millennials (aged 18-34 in 2017) were generally less likely to adopt waste-reduction behaviours compared with other age groups. But they excelled in using reusable coffee cups.

Why was the show so successful in encouraging people, and specifically millennials, to use reusable coffee cups?

If we can explain why this behaviour was so readily adopted, perhaps we can promote other sustainable behaviours at scale, in other entertainment-education interventions.

Our research uncovered five tactics used by the show to get these results.

1. Use A Relatable Host

Humans relate to people on TV. Research shows celebrities and people we consider engaging and credible are more likely to influence us.

Reucassel is a popular host with celebrity status. One focus group participant said:

A lot of films […] feel very preachy. It’s often either an expert, or just a narrator, who clearly didn’t know anything about the topic beforehand, who has now researched things, who is telling you things. Whereas in the case of the War on Waste, it felt more like he [Reucassel] was learning it with you, at the same time.

In the first season, we watched as Reucassel sorted the contents of a recycling bin, sharing the learning experience with the viewer. Research shows we are more likely to adopt a new behaviour if we’re shown how to do it rather than told what to do.

2. Mix Statistics With Confronting Visuals

High-impact visuals have lasting effect. Reucassel’s many stunts served not only as an engaging way to present statistics, but also a way to connect with viewers by stirring up emotions. This approach builds audience knowledge and willpower, making a change in behaviour more likely.

As one focus group participant put it:

My favourite thing about the show was all the stunts that Craig pulled – it’s classic Chaser stuff. Like the big rolling ball of plastic bags and the tram full of coffee cups. I thought that aspect of it was the most hard-hitting and interesting.

3. Promote Widespread Community Action

A common problem with behaviour change initiatives is a person will only change their behaviour if they feel like others are going to change their behaviour too. This often leads to “the tragedy of the commons”, where no one ends up taking action.

The opposite was true for War on Waste. Focus group participants felt the show created a groundswell for environmental change, so they were more inspired to take action because they felt others were taking action too. In the words of one:

I really enjoyed how it was a mix of personal actions [and] more systemic changes […] like getting Coles and Woolworths to change cosmetic standards [for fresh produce] but also the episode with the fast fashion, about getting the teenage girls to consider their own personal choices.

4. Choose Behaviours With An Easy Learning Curve

Reducing waste may never be “easy”, but by choosing behaviours perceived to be low-cost with little inconvenience, we have a better chance of success.

Swapping the disposable coffee cup for a reusable cup was considered relatively easy with a “quick learning curve” – compared to composting or having a worm farm – and so became more readily adopted than other behaviours demonstrated in War on Waste.

5. Show How Behaviour Can Reveal Social Identity

People from all generations prefer to act in accordance with what society deems acceptable. So pro-environmental behaviours are more likely to be adopted when social pressure is placed on them.

War on Waste placed social pressure on us all to reduce our waste. Adopting a reusable coffee cup became a visible symbol for millennials to demonstrate to others that they were doing their bit, while expressing their environmental values.

As one participant said:

I think it’s just a trendy, convenient way to maybe look and feel like you are doing something that’s […] the right step.

What Can We Learn From This, And What’s Next?

Many of the strategies we identified as successful in season one reappeared this year in season three, such as confronting visual stunts, shared learning experiences and targeting easy behaviours.

Based on the findings from our research, we expect to see further positive change generated from this season.

Our research also presents an opportunity to practitioners wanting to create behaviour change at scale by providing them with behavioural science strategies to embed in entertainment-education interventions. ![]()

Danie Nilsson, Behavioural Scientist, CSIRO and Rachael Vorwerk, Science Communicator, ARC Centre of Excellence in Optical Microcombs for Breakthrough Science (COMBS), RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We need a global treaty to solve plastic pollution – acid rain and ozone depletion show us why

After years of discussion, international negotiations on a global plastics treaty resume this week in Nairobi, Kenya, at the UN Environment Programme headquarters.

The third session of the UN Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution will take place from today until Sunday November 19.

The committee’s goal is to develop a legally binding agreement, finalised in 2024, to address the full life cycle of plastics – including their production, design and disposal.

Involving 175 nations, the treaty aims to transform plastic waste management, paving the way for new technologies and industries.

The problem of plastic pollution is too big for any one nation to handle. That’s why we need a global approach. It’s worked before with the ozone layer and acid rain and it can work again with plastic.

How We Repaired The Ozone Layer

At CSIRO I lead the Ending Plastic Waste Mission, which aims to change the way we make, use, recycle and dispose of plastic. Our work aligns with the aims of the proposed UN plastic treaty, so I have been following the negotiations closely.

Multilateral agreements have helped create significant change in the past. The Montreal Protocol shaped environmental and industrial landscapes globally. Enacted in 1987, the protocol’s objective was to phase out substances causing ozone depletion.

The protocol is widely recognised for its global ratification – everyone got on board. And countries continued to adhere to the changes. This ongoing work has not only contributed to the tangible recovery of the ozone layer, but also prevented millions of potential cases of skin cancers and cataracts.

The protocol also sparked chemical industry innovation. Industries had to transition away from ozone-depleting substances such as chlorofluorocarbons or CFCs to more environmentally friendly alternatives.

The earliest replacements – hydrofluorocarbons or HFCs – were quickly recognised as a potent greenhouse gas, resulting in the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the protocol to phase them out too and use climate-friendly alternatives. As a result of this global process, we now have safer chemicals for refrigeration and air conditioning.

Global Legislation Can Deliver Real Change

Clean air legislation is another example. Acid rain became a prominent environmental concern in the latter half of the 20th century. It happens when sulphur dioxide (SO₂) and nitrogen oxides are released into the atmosphere, typically from industrial processes and the burning of fossil fuels.

Once in the atmosphere, these pollutants react with water vapour to form sulphuric acid and nitric acid. As they fall to the ground mixed with rain or snow, the high acidity harms aquatic ecosystems, forests and even human-made structures.

In response, various countries enacted clean air legislation. For instance, the United States Clean Air Act of 1963, amended several times in the following decades, motivated change in industrial and automotive sectors.

The laws forced industries to transition to cleaner technologies and invest in advanced pollution-control equipment. This paved the way for a widespread adoption of catalytic converters and more fuel-efficient engines.

How Multilateral Agreements Can Force Change

Regulatory tools such as multilateral agreements introduce restrictions. Instead of doing business as usual, these restrictions then foster cleaner, more sustainable practices. They blend environmental responsibility with business imperatives. As a result, the regulatory changes open up new market opportunities.

Additionally, global collaborations driven by these agreements often encourage the transfer of technologies across borders. This speeds up the adoption of cleaner technologies.

Multilateral environmental agreements can drive technological progress and industrial innovation. By establishing high standards and fostering global collaboration, these agreements blend environmental stewardship with industrial evolution.

Now For The UN Plastic Treaty

The global plastic treaty will address the pervasive challenge of plastic pollution, which affects our oceans, marine life and carbon footprint. It is expected to usher in transformative regulations on waste management, reduce the use of single-use plastics and advocate for the circular economy principles of eliminating waste and keeping materials circulating in use.

We are already seeing a shift in plastics manufacturing towards more sustainable, biodegradable, or recyclable plastics. Industries are developing more circular business models that emphasise the reuse and recycling of products and reducing waste.

To reduce single-use plastics, the packaging industry is transitioning towards reduction, reuse and recyclability. Advanced recycling technologies and better bio-derived plastics are expected to emerge as industry standards.

The multilateral treaty and its implementation will help to reduce problematic and unnecessary plastics. It will also speed up the removal of harmful chemicals from product supply chains.

The UN plastic treaty is set to be finalised in 2024. If we can get a global agreement on this, we have a real opportunity to significantly reduce plastic waste for a sustainable future.![]()

Deborah Lau, Ending Plastic Waste Mission Director, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

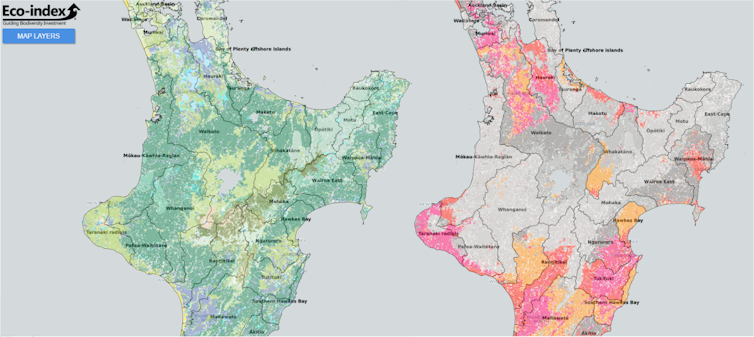

Restoring ecosystems to boost biodiversity is an urgent priority – our ‘Eco-index’ can guide the way

Biodiversity continues to decline globally, but nowhere is the loss more pronounced than in Aotearoa New Zealand, which has the highest proportion of threatened indigenous species in the world.

We hope our Eco-index initiative, which today launches an online ecosystem restoration map for New Zealand, will help change the story for nature.

Planning large-scale biodiversity restoration projects – whether they’re run by NGOs, governments or Indigenous groups – requires high-quality data.

Despite the rising demand, however, accessible biodiversity data have not been collected regularly or consistently. There are also challenges around the standardisation, storage and sharing of such data.

This means it has been difficult to quantify native ecosystems and biodiversity at scale. Cost-benefit analyses often have information gaps, meaning prioritising the various options for restoration projects can become guesswork.

Better Data With Help From New Technologies

Without accurate information, improving biodiversity becomes harder. But emerging technologies – such as remote sensing and artificial intelligence – are making it easier to gather better data.

The Eco-index Ecosystem Restoration Map provides New Zealand’s first public, open-access digital tool in this area. It aims to address information gaps in biodiversity restoration, and to show users which native ecosystems are appropriate to reconstruct in any given catchment area.

It also shows where the highest restoration priorities are – such as in areas with very low native ecosystem cover. And it allows anyone to view the restoration targets for each native ecosystem in any catchment.

The map was developed with input from Indigenous leaders, rural professionals, community group leaders, government and industry bodies. Our goal is to share science-based information to support national discussion, policy and planning for ecosystem restoration.

It will be most useful when used alongside local information based on regional council guidance and local restoration expertise.

Ecological, economic, social and data science underpin the map’s development, as well as mātauranga Māori (Indigenous knowledge). The map will continue to be refined with data from new technologies and user feedback.

Biodiversity In Policy And Business

Internationally, there is growing interest in more strategic biodiversity support, including improved policy frameworks and sustainable finance.

New Zealand is addressing some national biodiversity issues through policy, such as the release of a national biodiversity strategy. The strategy encompasses three pillars, with objectives to improve systems that influence biodiversity, empower residents to take action, and protect or restore native biodiversity.

New Zealand’s National Policy Statement for Indigenous Biodiversity requires regional councils to safeguard native biodiversity and to “set a target of at least 10% Indigenous vegetation cover”.

The Eco-index has a minimum goal of 15% native ecosystem cover. It recommends land managers tackle ecosystem restoration from wherever they are now. This may mean aiming for 10% cover in the next ten years, followed by 15% in 15 years, and 30% in two decades.

The rationale behind the 15% goal is that large tracts of native ecosystems support more native species than small, fragmented patches. Once an area drops below 10-20% of its original land cover, the number of species it can support declines suddenly.

Aotearoa New Zealand is also a signatory to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework against which biodiversity strategy outcomes will be assessed and reported internationally.

Beyond this, global discussions focus on the development of biodiversity credit frameworks and include considerations such as the United Nations-supported Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures. The potential of these separate but aligned initiatives to create cumulative, positive impacts for nature is substantial.

Creating Change

The success of these policies and frameworks hinges on the availability of high-quality data to understand the current state and trends in biodiversity, and to monitor outcomes.

Initiated in 2020, the Eco-index group focuses on biodiversity in Aotearoa New Zealand being protected, restored and connected by 2121. This long term vision aligns with inter-generational land-management thinking. It acknowledges that it takes time to fully realise these native biodiversity ambitions.

Eco-index also claims the status of being the first digital public good in New Zealand. The interactive public map is the first publicly available tool, with other digital tools in development for release next year.

The wider toolkit aims to empower large-scale restoration planning with a range of customised spatial and economic tools. These can help identify the best locations for planting, inform costings, and provide valuations of ecosystem services.

They can also detect native ecosystems remotely, using satellite imagery and artificial intelligence.

If successful, the toolkit can be expanded for global use. It could also include specialised tools for natural hazard mitigation, such as the restoration of urban wetlands for flood control.

These tools are developed from the best information available, including Planet satellite imagery and data from Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research and Rongowai Science Payloads Operations Centre in partnership with the Geospatial Research Institute.![]()

Kiri Joy Wallace, Research Fellow in Restoration Ecology, University of Waikato; John Reid, Senior Research Fellow, University of Canterbury, and Penny Payne, Social Scientist, University of Waikato

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Fire is consuming more than ever of the world’s forests, threatening supplies of wood and paper

A third of the world’s forests are cut for timber. This generates US$1.5 trillion annually. But wildfire threatens industries such as timber milling and paper manufacturing, and the threat is far greater than most people realise.

Our research, published today in the journal Nature Geoscience, shows that between 2001 and 2021, severe wildfires worldwide destroyed timber-producing forests equivalent to an area the size of Great Britain. Severe fires reach the tree tops and consume the forest canopy.

The amount of timber-producing forest burning each year in severe wildfires has increased significantly in the past decade. The western United States, Canada, Siberia, Brazil and Australia have been most affected.

Timber demand is expected to almost triple by 2050. Supplying demand is clearly going to be challenging. Our research highlights the need to urgently adopt new management strategies and emerging technologies to combat the increasing threat of wildfires.

What We Found

We combined global maps of logging activity and severe wildfires to determine how much timber-producing forest was lost to wildfire this century. Between 2001 and 2021, up to 25 million hectares of timber-producing forest was severely burned. The extent of fire has jumped markedly in the past decade, from an average of less than one million hectares a year up to 2015 to triple that since then.

At a national scale, the three countries with the largest absolute wildfire-induced losses of timber-producing forest were Russia, the US and Canada. When it comes to proportion of their forestry land lost, the nations with the highest percentages burnt were Portugal, followed by Australia.

Why Are More Forests Burning?

Climate change is a major driver of fire weather and fire behaviour. The increased risk of high-severity wildfire is an entirely expected outcome of warmer temperatures and, in some places, reduced rainfall.

However, it remains unclear why so much wood-production forest is being lost, and why the increase in burnt area has been so marked in the past decade.

One possible reason is logging makes forests more flammable. This has been documented in parts of southeastern Australia, where intact forest always burnt at lower severity than harvested forest across the entire footprint of the Black Summer fires. Forests that have been subject to thinning also are at risk of high-severity wildfire.

What Does This Mean For Us?

Whatever the reason, it is clear these fires in wood-production forests will have profound impacts on global timber supplies and all the industries associated with them. This is a huge problem for society and the environment, because timber demand is expected to triple by 2050, in part to facilitate the transition away from carbon-intensive cement in construction.

In many parts of the world, it typically takes 80–100 years or even longer to grow a tree to a size at which it can be a sawlog for products like furniture and floorboards. So the increased frequency of high-severity wildfire means fewer areas of forest will escape fire for long enough to reach timber harvesting age.

This is especially problematic where logging makes forests more prone to burning in a high-severity wildfire.

Furthermore, given the long-term nature of timber production, typically on cutting cycles ranging from 40 years to more than a century, future timber crops will face a very different climate as they mature.

Responding To The Challenge