Inbox and environment news: Issue 613

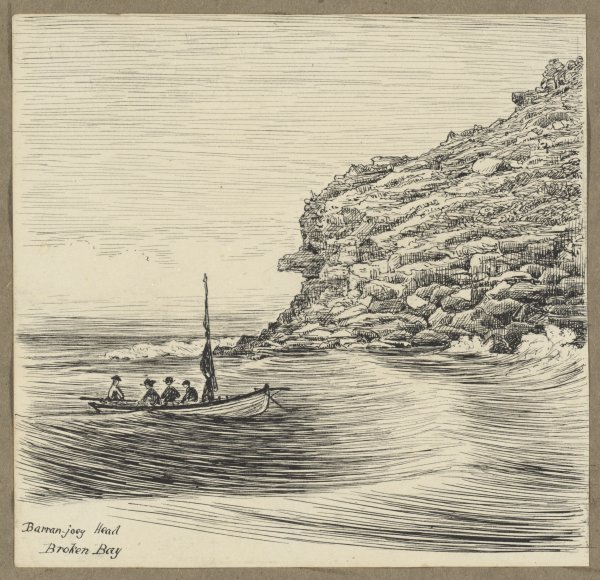

February 11 - 17, 2024: Issue 613

Historic 100-Year-Old Mona Vale Tree To Be Replaced

For over 100 years the Mona Vale Victory Tree has stood sentry at the site of the original local Methodist Church on Pittwater Road.

Planted to commemorate the end of World War I and in honour of the many fallen soldiers, the tree has succumbed to Armillaria Root Rot disease.

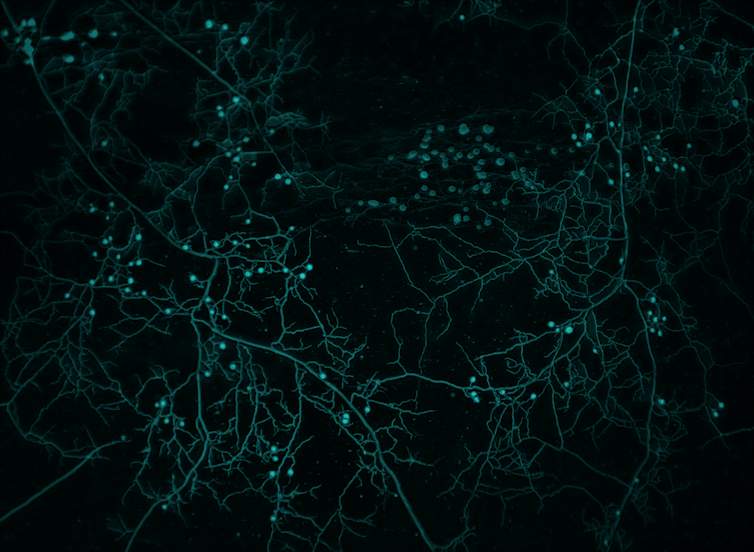

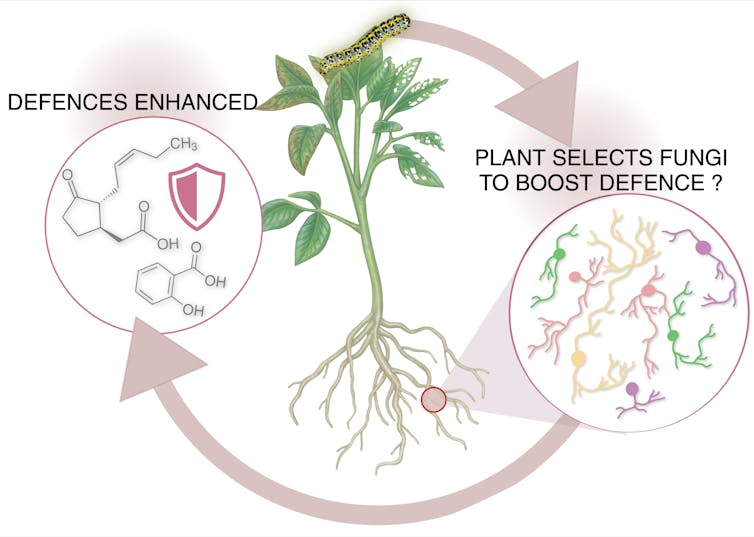

Armillaria root rot is a disease of trees and woody plants, although it also affects palms, succulents, ferns and other herbaceous plants. This disease is caused by fungi in the genus Armillaria, also known as “oak root fungus,” although the fungus has no specificity for oaks.

Overseas, the disease is reported to be caused by Armillaria mellea. But in Australia a related indigenous fungus Armillaria luteobubalina is the most common cause of Armillaria root rot.

The fungus can spread in several ways, but usually spread is from a woody food base such as an infected tree or stump, or a small piece of infected root.

Most spread is by root contact: the fungus grows from a diseased root into a healthy root via the point of contact of the roots. Rhizomorphs can grow from infected roots through the soil to roots of a nearby plant.

Occasionally, after an infected tree has died, honey-coloured clusters of toadstools grow from the base of the tree. These usually appear from May to July. The toadstools (the fruiting bodies of the fungus) have honey-coloured to deep brown caps covered with scales, whitish gills and yellow to brown stems with a pronounced ring or collar around the upper part of the stem

Airborne spores produced by the toadstools can be another method of spread, although these spores can only infect dead or injured wood.

Situated on private property, Council states it has worked with the property owner trying several treatments to save the tree. Over an eight-month period these treatments, recommended by Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens PlantClinic, were tested on the tree without success.

Council announced on Thursday February 8 it is now planning to plant another symbolic tree nearby as they are unable to plant in the same location due to soil contamination.

The century-old Holly Oak (Quercus ilex), an evergreen oak, was one of the remaining few of the original 200 trees planted across NSW under a Methodist Youth program, supplied with the assistance of Mr J H Maiden, Chief Botanist at Sydney Botanical Gardens.

The aim of the planting was for the relatives and friends of those who died to have a place to leave flowers and acknowledge their loved ones in the absence of a grave site.

Council’s Heritage Officer is assisting with guidance on preserving the tree’s heritage value.

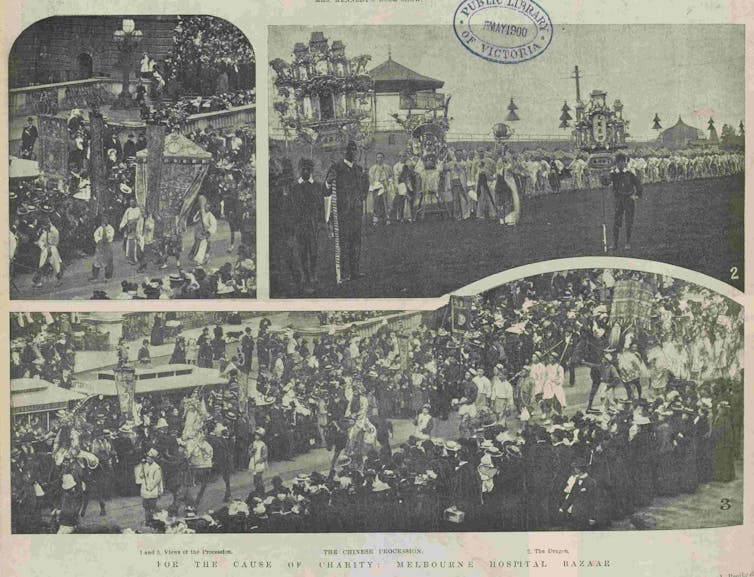

The Mona Vale tree was planted in 1920 and became the first place Mona Vale ANZAC Day ceremonies were conducted by students and the community:

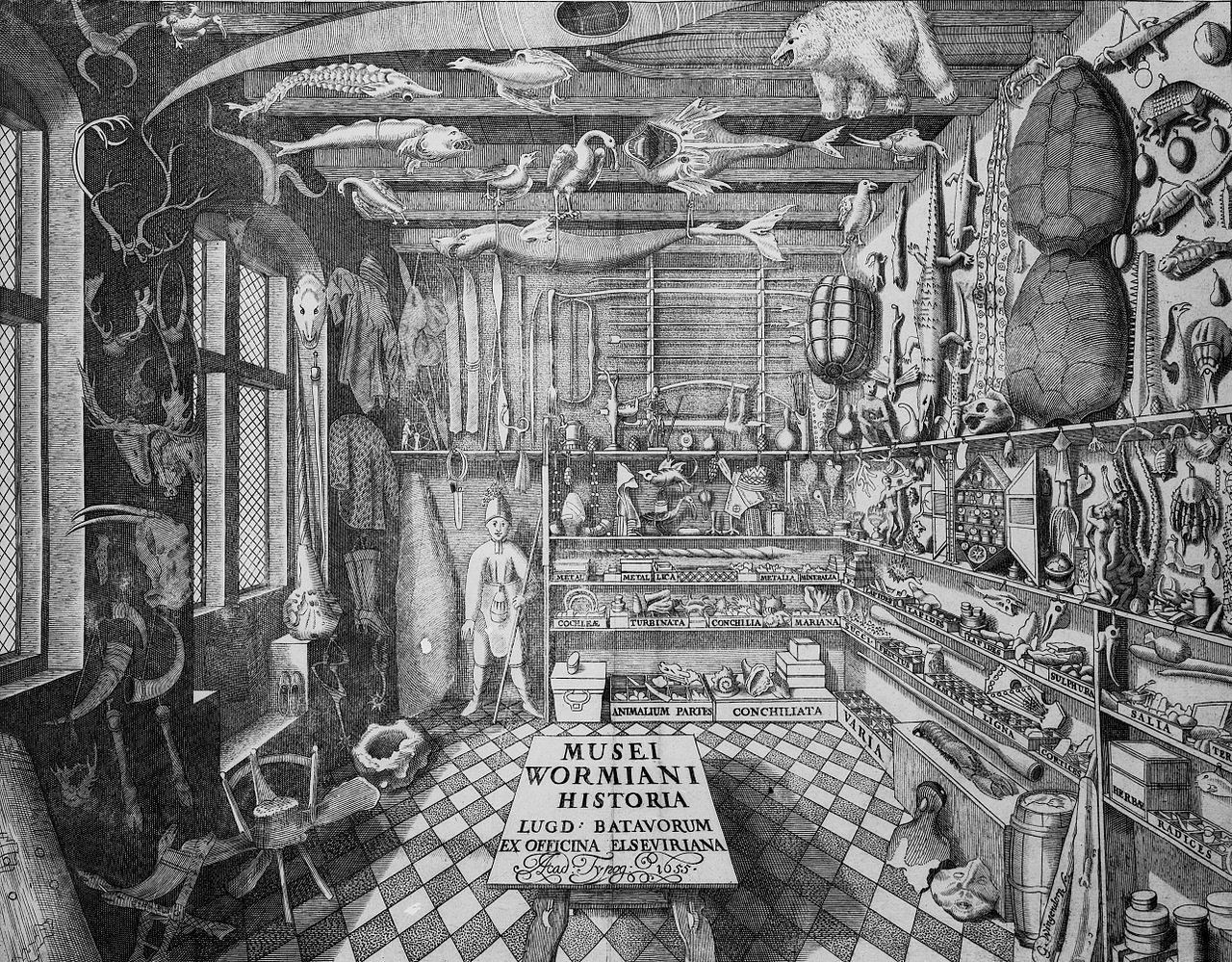

The Victory Tree.

To stand as a living expression of gratitude to God for victory in the great war, and to continually remind the youth of Methodism of the ideals for which our soldiers so nobly fought,' the Young People 's Department recently offered to present and forward to every Sunday School in the State a 'Victory Tree,' for planting in school or church grounds. The Department stipulated that applications should be made upon a prescribed form, which stated the conditions of gift, and a copy of which was forwarded to every Sunday School.

Below is a list of the schools ' that have made application for a tree, and to many of these the trees have already been forwarded. Superintendents and teachers are requested to scan the list, and if the name of their school does not appear thereon, to take steps to have an application lodged at the Y.P. Department's Office at an early date.

The trees are beautiful specimens of the kind most suit-able for the districts concerned, and the presentation of them is made possible by the kindness of Mr. Maiden, the Government Botanist: —

SYDNEY DISTRICT.— Rockdale, French's Forest, West Bexley, St. Ives, Bexley, Pymble, Turramurra, Wahroonga, Willoughby, Tempe Park, Bondi, Waverley, Malvern Hill, Chatswood (Central), Mona Vale...The Victory Tree. (1920, June 19). The Methodist (Sydney, NSW : 1892 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155274628

Narrabeen Lagoon Entrance Blocked Again

Narrabeen lagoon entrance is blocked again, after recent storm swells, and Council spending $1.5. million on moving the sand south to Collaroy for weeks.

Council announced on Tuesday, 12 September 2023 work to clear Narrabeen Lagoon entrance to reduce the risk of flooding to local homes and businesses.

''Council contractors will excavate more than 20,000 cubic metres (40,000 tonnes) of sand – equivalent to the weight of 100 jumbo jets – to the east and west of Ocean Street Bridge.'' it was stated

The sand is to be deposited at Collaroy-Narrabeen Beach between Goodwin and Stuart Streets.

Works were expected to start in the coming weeks, although the above photo shows they were commenced immediately, and were completed in time for the Summer school holidays, which commenced on December 19 2023. This means the lagoon entrance was open for around 6.5 weeks prior to the big seas which moved so much sand over the past few days of weather conditions as the tail end of Cyclone Kirrily moved south.

After impacting Queensland, ex-Tropical Cyclone Kirrily crossed the border into western NSW on Monday afternoon, February 5, bringing heavy rainfall and flash flooding to inland communities, before reaching Sydney early the next day bringing 21mm of rain and localised flash flooding, along with strong winds.

This had preceded by swell set to peak at 4 to 4.5 metres in Sydney over the weekend of February 3-4.

However, at high tide about 6 inches of water still goes over the top of the entrance and into the lagoon. Joe Mills' (Turimetta Moods) sent in pictures this week of Pelicans standing in the shallow overflow at high tide - see below.

Joe said; ''They are waiting (with the Cormorants and Seagulls as well) for the small fish brought in by the waves.''

So - good for some residents of the lagoon.

The Wonderful Songs Of The Butcher Bird - Summer In Pittwater: 15

Stinky Mushroom Worth Keeping Around

Australia's Climate In 2023: Warmer With Contrasting Rainfall - BOM

- Winter 2023 was Australia's warmest on record, with the national mean temperature 1.53C above the 1961–1990 average.

- September 2023 was Australia’s driest September on record with total rainfall around 70% below the 1961–1990 average, and the second driest month since national rainfall records began in 1900, behind April 1902.

- August to October 2023 was Australia's driest three month period since rainfall records began in 1900.

- Sea surface temperatures for the Australian region were the seventh-highest on record since 1900 at 0.54°C above the 1961–1990 average.

- Globally, sea surface temperatures were the highest on record – and each of the past 10 years have been among the 10 warmest on record.

- The state-averaged annual rainfall was 428.9 mm, which was 22.9% below the 1961–1990 average.

- Rainfall was above average over small parts of the state's south, west of the Great Dividing Range, while being below average over most of the northern half of the state, especially over parts of the Northern Tablelands, Northern Rivers, Mid-North Coast, and Upper Hunter, where annual rainfall was in the lowest 10% of historical records (since records began in 1900).

- A number of sites had their highest daily rainfall on record.

- Moruya (Kiora) had its highest total rainfall on record.

- The state-averaged annual maximum temperature was 1.96 °C above the 1961–1990 average, which is the third-highest on record (since records began in 1910) and the highest since 2019.

- Maximum temperatures for March, June, August, September and December were in the top ten warmest on record for their respective months.

- Maximum temperatures were very much above average over most of the state, with north-west parts of the state being highest on record.

- The state-averaged annual minimum temperature was 0.63 °C above the 1961–1990 average.

- Minimum temperatures were above average over northern and south-eastern parts of the state, as well as over central parts of the coast, while being below average over parts of the Riverina and the Central Tablelands.

- The state-averaged annual mean temperature was 1.30 °C above the 1961–1990 average, which is the equal sixth-highest on record.

- A number of sites had their highest mean daily maximum temperature on record.

- Scone Airport AWS and Mangrove Mountain AWS had their lowest temperature on record.

- A few sites along the South Coast had their warmest night (highest daily minimum temperature) on record.

- Ulladulla AWS had its highest mean daily minimum temperature on record.

- Mangrove Mountain AWS and Lismore Airport AWS had their lowest mean daily minimum temperature on record while a few sites had their lowest mean daily minimum temperature for at least 20 years.

- A few sites had their equal-highest mean temperature on record.

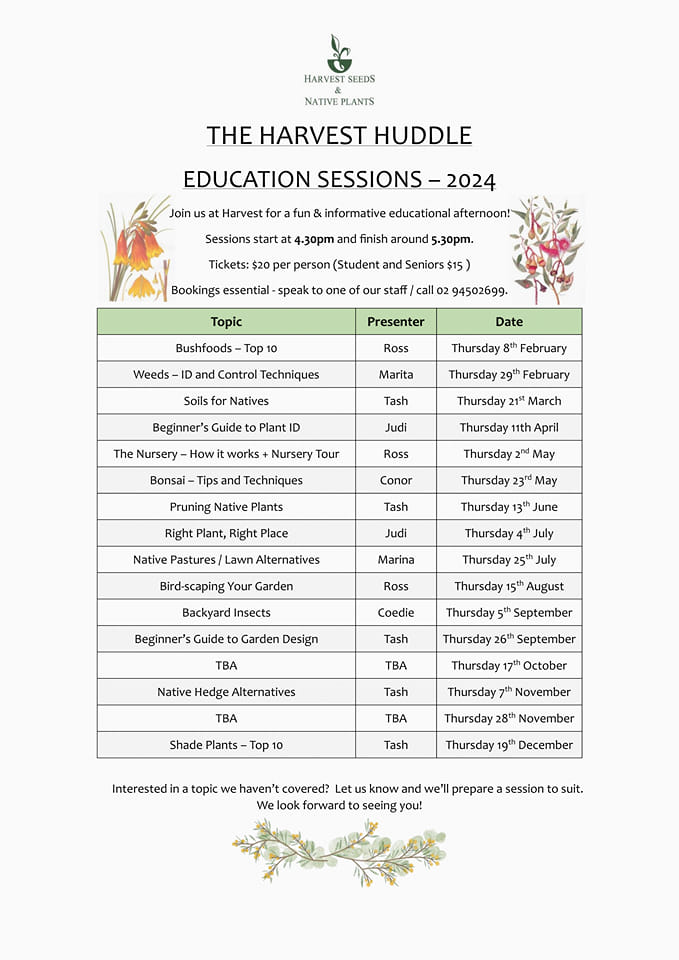

Harvest Seeds & Native Plants: Education Sessions 2024 - "The Harvest Huddle"

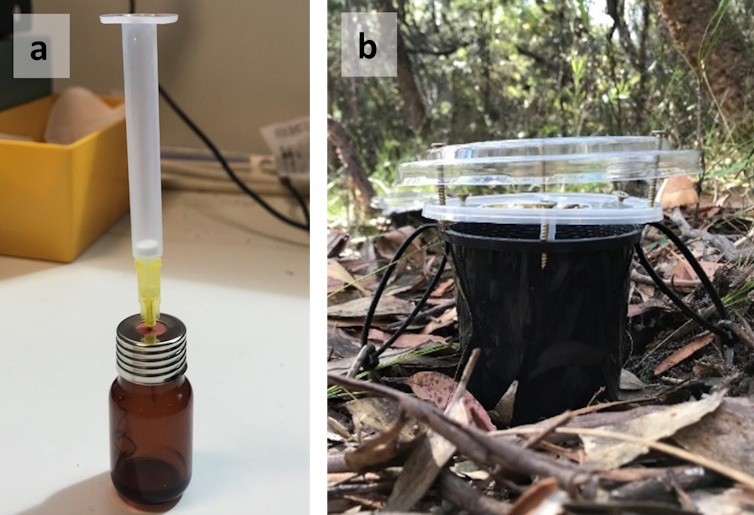

Notice Of 1080 Baiting: February 1 - July 31 2024

Please note the following notification of continuous and ongoing fox control using 1080 POISON with ground baits and canid pest ejectors (CPE’s) in Sydney Harbour National Park, Garigal National Park, Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, and Lane Cove National Park. As part of this program, baiting also occurs on North Head Sanctuary managed by Sydney Harbour Federation Trust and the Australian Institute of Police Management facility at North Head.

This provides notification for the 6 monthly period of 1 February 2024 – 31 July 2024.

Warning signs are displayed at park entrances and other entrances to the baiting location to inform the public of 1080 baiting.

1080 Poison for fox control is used in these reserves in a continuous and ongoing manner. This means that baits and ejectors (CPE’s) remain in the reserves and are checked/replaced every 6 – 8 weeks.

1080 use at these locations is in accordance with NSW pesticides legislation, relevant 1080 Pesticide Control Orders and the NPWS Vertebrate Pesticides Standard Operating Procedures.

A series of public notifications occur on a 6 monthly basis including; alerts on the NPWS website, public notices in local papers, Area pesticide use notification registers and to the NPWS call centre.

If you have any further general enquiries about 1080, or for specific program enquiries please contact the local NPWS Area office:

For further information please call the local NPWS office on:

NPWS Sydney North (Middle Head) Area office: 9960 6266

NPWS Sydney North (Forestville) Area office: 9451 3479

NPWS North West Sydney (Lane Cove NP) Area office: 8448 0400

NPWS after-hours Duty officer service: 1300 056 294

Sydney Harbour Federation Trust: 8969 2128

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association: First PNHA Nature Event 2024

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Bilgola Beach Clean - February 25

Clean Up Australia Day 2024 Registrations Are Now Open

NEW At Eco House & Garden(At Kimbriki): 'Supporting School & Community Composts Workshop'

Where you can become part of the (waste) solution in our 3-hour workshop.

See below for more details and for bookings go to 👉https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1162545

Kimbriki Resource Recovery Centre: Early Childhood Educators Professional Development Day

As part of Kimbriki's 2024 Eco House & Garden Educational Calendar, this year we introduce the Early Childhood Educators Professional Development Day on Friday 22nd March. For more details and bookings 👉 https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1162305

Coastal IFOA Forest Monitoring Review

Consultation period

From: 22 January 2024

To: 18 February 2024

The Natural Resources Commission is seeking your feedback on monitoring in NSW’s coastal state forests. The Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approval (Coastal IFOA) sets out the rules for native timber harvesting in NSW coastal state forests. These rules have been in place since November 2019.

A monitoring program has been established to assess the ongoing effectiveness of the Coastal IFOA in delivering its objectives and outcomes. The first program framework was approved in March 2020 and extends to 2024.

Get more information on the Coastal IFOA monitoring program.

The monitoring program must have a major review every five years, the first of which is due in 2024. This first review will focus on program progress and results, including trends. It will also assess the adequacy of the program and how it can be improved.

This review must include:

- detailed reporting of monitoring program progress and all results

- detailed analysis of trends

- an assessment of the adequacy of the monitoring program.

The Natural Resources Commission is undertaking the review as part of its role as the independent chair of a cross-agency Steering Committee that oversees the monitoring program.

To inform the review, we are seeking your thoughts on the first five years of the Coastal IFOA monitoring program, including any feedback on:

- Does the monitoring program provide useful information and insights that meet your needs? If not, what are the key gaps?

- Is the monitoring program and its findings clear and easy to understand, or can this be improved?

- Any other ways we can improve the monitoring program?

Have your say by Sunday 18 February 2024 via:

Email: nrc@nrc.nsw.gov.au

Mail: Address - Natural Resources Commission, GPO Box 5341, Sydney, NSW, 2001.

More information

Email: Project team

Phone: 02 9228 4844

Documents

Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approval Approved Monitoring Program 2019-2024 (PDF 2.38MB)

Stay Safe From Mosquitoes

- Applying repellent to exposed skin. Use repellents that contain DEET, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus. Check the label for reapplication times.

- Re-applying repellent regularly, particularly after swimming. Be sure to apply sunscreen first and then apply repellent.

- Wearing light, loose-fitting long-sleeve shirts, long pants and covered footwear and socks.

- Avoiding going outdoors during peak mosquito times, especially at dawn and dusk.

- Using insecticide sprays, vapour dispensing units and mosquito coils to repel mosquitoes (mosquito coils should only be used outdoors in well-ventilated areas)

- Covering windows and doors with insect screens and checking there are no gaps.

- Removing items that may collect water such as old tyres and empty pots from around your home to reduce the places where mosquitoes can breed.

- Using repellents that are safe for children. Most skin repellents are safe for use on children aged three months and older. Always check the label for instructions. Protecting infants aged less than three months by using an infant carrier draped with mosquito netting, secured along the edges.

- While camping, use a tent that has fly screens to prevent mosquitoes entering or sleep under a mosquito net.

Mountain Bike Incidents On Public Land: Survey

- Mountain Bike Incidents On Public Land: Survey Launched To Gather Data On What's Happening To Public Parks - Community Land - Bush Reserves In Pittwater

- Mother Brushtail Killed On Barrenjoey Road: Baby Cried All Night - Powerful Owl Struck At Same Time At Careel Bay During Owlet Fledgling Season: calls for mitigation measures - The List of 'What You can Do' as requested

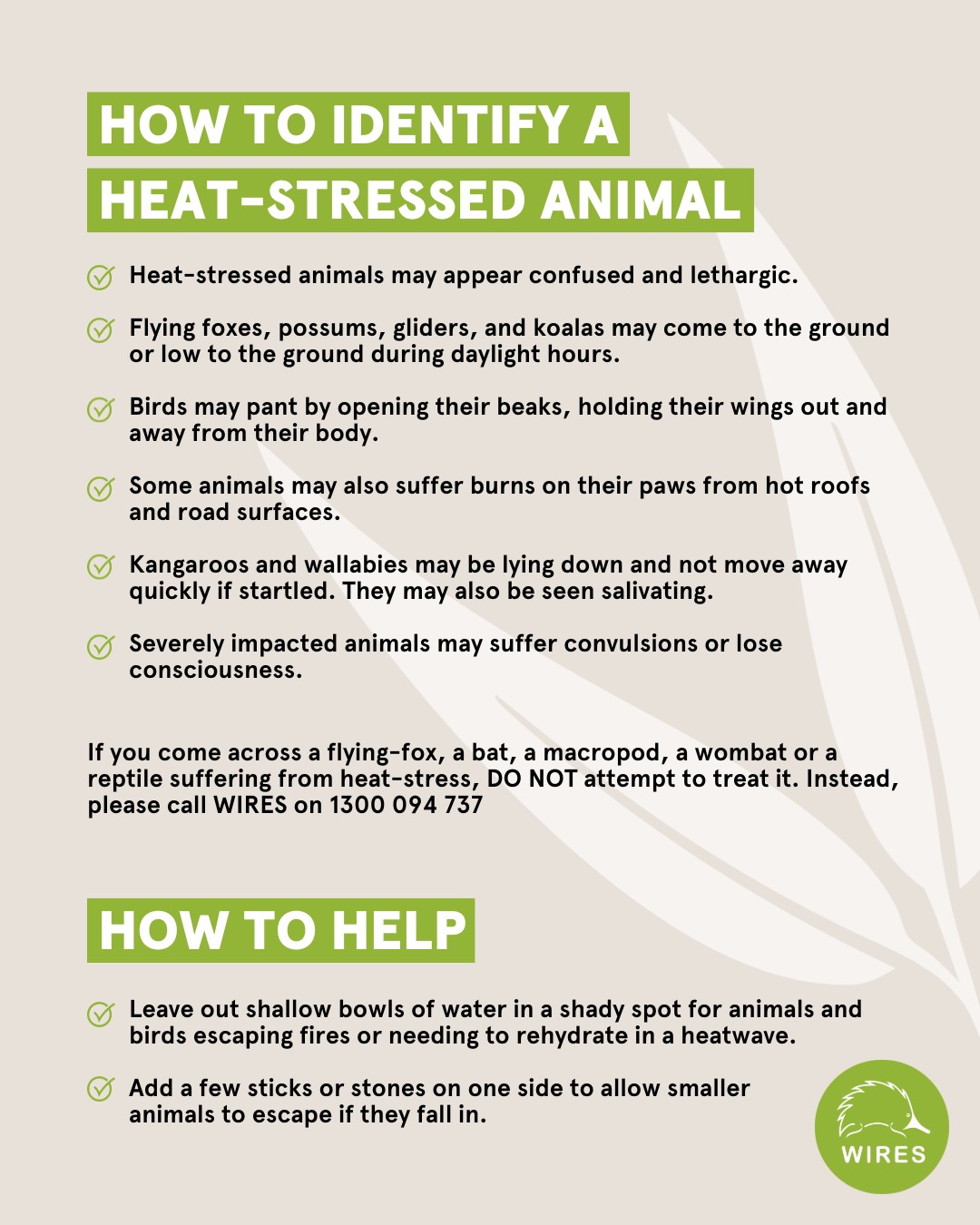

Please Look Out For Wildlife During Heatwave Events

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

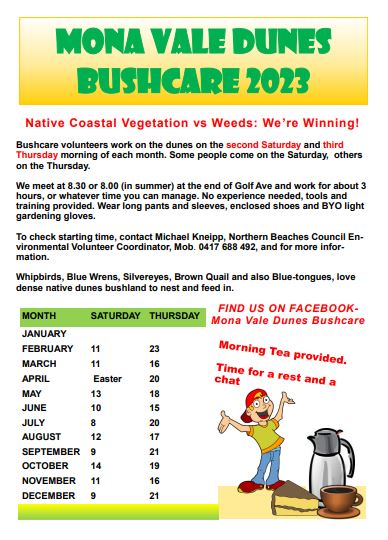

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

- Ringtail Posse: 1 – February 2023; Anna Maria Monticelli: King Parrots/Water Dragons - Jacqui Scruby: Loggerhead Turtle - Lyn Millett OAM: Flying-Foxes - Kevin Murray: Our Backyard Frogs - Miranda Korzy: Brushtail Possums

- Ringtail Posse: 2 - March 2023; Kevin Murray: Tawny Frogmouth - Kayleigh Greig: Red-Bellied Black Snake - Bec Woods: Australian Water Dragon - Margaret Woods: Owlet-Nightjar - Hilary Green: Butcher Bird - Susan Sorensen: Wallaby

- Ringtail Posse 3 - April 2023: Jeffrey Quinn: Kookaburra, Tom Borg McGee: Kookaburra, Stephanie Galloway-Brown: Bandicoot, Joe Mills: Noisy Miner

- Ringtail Posse 4 May 2023 - Andrew Gregory: Powerful Owl, Marita Macrae: Pale-Lipped Or Gully Shadeskink, Jools Farrell: Whales & Seals, Nicole Romain: Yellow-Tailed Black Cockatoo

- Ringtail Posse 5: June 2023 - Lynleigh Greig OAM: Snakes, Dick Clarke: Diamond Python, Selena Griffith: Glossy Black-Cockatoo, Eric Gumley: Bandicoot

- Ringtail Posse 6: July 2023 - Sonja Elwood: Long-Nosed Bandicoot, Dr. Conny Harris: Swamp Wallaby, Neil Evers: Bandicoot, Bill Goddard: Bandicoot

- Ringtail Posse 7: August 2023 - Geoff Searl OAM: Tawny Frogmouth, Peter Macinnis: Echidna, Peter Carter: Ringtail Possum, Nathan Wellings; Kookaburra

- Ringtail Posse 8: September 2023 - Saving Sydney's Last Koalas; Logging Now Stopped In Future Koala Park By Minns Government - ''Is There Time To Save Sydney's Last Koalas Too?'' Asks: John Illingsworth, WIRES, Sydney Wildlife Rescue, Save Sydney Koalas, The Sydney Basin Koala Network, The Help Save The Wildlife & Bushlands In Campbelltown Group, Appin Koalas Animal Rescue Service, Patricia and Barry Durham, Sue Gay, Save Mt. Gilead, Paola Torti Of The International Koala Intervention Group

- Ringtail Posse 9: October 2023 - David Palmer OAM: Bandicoots, Helen Pearce: Brushtail Possum, Amina Kitching: Goanna, David Goudie: Ringtails Possums + Bandicoots + Owls

- Mother Brushtail Killed On Barrenjoey Road: Baby Cried All Night - Powerful Owl Struck At Same Time At Careel Bay During Owlet Fledgling Season: calls for mitigation measures - The List of what you can do for those who ask 'What You I Do' as requested

- Ringtail Posse 10: November 2023 - Stop Wildlife Roadkill Group: You Can Help By Using The Wildlife Incident Mapping Website

Harry Potter and the Disenchanted Wildlife: how light and sound shows can harm nocturnal animals

Jaana Dielenberg, Charles Darwin University; Euan Ritchie, Deakin University; Loren Fardell, The University of Queensland, and Therésa Jones, The University of MelbourneLight and sound shows in parks can enthral crowds with their colour, music and storytelling. Lasting for weeks to months, the shows provide entertainment and can boost local economies. But unless they are well-located, the shows can also harm wildlife.

A planned production at a wildlife sanctuary in outer Melbourne has brought these concerns to the fore. In April and May this year, a wildlife reserve on the Mornington Peninsula will host Harry Potter: A Forbidden Forest Experience. The event involves a two-kilometre night walk where, according to organisers, characters from the film are “brought to life”.

The event has prompted an outcry from people worried about the effect on the reserve’s vulnerable wildlife. The sanctuary, known as The Briars, is home to native animals including powerful and boobook owls, owlet-nightjars, koalas, wallabies, Krefft’s gliders, lizards, frogs, moths and spiders. A petition calling for the event to be relocated has attracted more than 21,000 signatures.

Research shows artificial light, sound and the presence of lots of people at night can harm wildlife. It’s not hard to see why. Imagine if a music and light show, and thousands of people, turned up at your house every night for weeks on end. How would you feel?

A History Of Community Opposition

In addition to the lights and sounds, these shows can involve artificial smoke and animated sculptures. While they often take place along existing walking trails, they attract huge crowds at a time when animals usually have the place to themselves.

Most of Australia’s mammals and frogs and many bird and reptile species are nocturnal, or active at night. They have adapted to the natural darkness, sounds and smells of the night.

The Harry Potter experience planned for The Briars has taken place elsewhere around the world, including at a nature area near the Belgian capital of Brussels. That event, in February last year, was also opposed by locals on ecological grounds. Belgian Minister for Nature Zuhal Demir has reportedly said the show would not return this year due to concern for wildlife.

Light shows proposed for other wildlife conservation areas have also faced community opposition. In Australia, there were calls to halt the Parrtjima light festival in the Alice Springs Desert Park over potential harm to the threatened black-footed rock wallabies. The Lumina light show proposed for Mount Coot-tha in Brisbane has also attracted concern for wildlife.

Light, Sounds, Action!

Research shows artificial light affects wildlife in many ways. For example, it can change their hormone levels, and the numbers and health of their offspring.

Light also interferes with the ability of many species to navigate. This can cause birds to become disorientated and crash. It can also prevent baby turtles from finding the sea.

Some animals will forgo feeding or drinking and attracting mates. Other animals will try to move to a darker location. In the Belgian case, locals claimed owls left the park to avoid the lights.

Studies of small mammals such as bats, micro-bats, possums and bandicoots have shown many will avoid using habitat that is artificially lit. When there is no alternative dark habitat, species forced to deal with bright conditions – whether natural or artificial – have been found to reduce their activity.

Conversely, some animals are attracted to light. Insects such as moths will cluster around the artificial light source, unable to leave. Some will become so exhausted they will become easy prey.

What’s more, human-caused noise also stresses animals and changes animal behaviour. It masks the natural soundscape, making it harder for animals to find mates or hear the calls of their young. It can also mean animals can’t hear predators or their prey.

When thousands of humans travel through an area they leave strong predator-like smells. This can be stressful for wildlife. It can also mask smells vital for an animal’s survival, such as that of food and predators.

Long-Term Harm

When faced with all this disruption, many nocturnal animals will hide until a site returns to normal, which in the case of light shows is often close to midnight. This cuts in half the time animals have to go about their life-sustaining activities and exposes them to greater risks when they do go out.

Light and sound shows are usually temporary – but can have major long-term impacts.

In species with low birth rates and short lifespans, a disturbance to breeding can be catastrophic. For example, males of the genus Antechinus (small marsupials) live long enough for just one short breeding season. If they are disrupted, there are no second chances.

The stress of human lights, sounds, smells and disturbance can shorten an animal’s life. Stress can make them more prone to illness and create problems with sleeping, reproduction, development and growth that can last for multiple generations.

Find A Better Location

The Mornington Peninsula Shire Council has defended the Harry Potter event, saying the placement of props, lights and sounds has been carefully considered.

Organisers may have minimised impacts where they can, but evidence suggests the impact on wildlife will still be extensive.

The sanctuary where the event will be held is billed as “an ark – a place which nurtures, protects and celebrates the unique flora and fauna of the peninsula, now rare but not lost”. Deliberately locating a light and sound show at the reserve seems at odds with this mission.

Events such as this clearly affect wildlife. Finding genuinely suitable locations should be done with care – and should avoid wildlife conservation areas altogether.![]()

Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University; Loren Fardell, Research Fellow, The University of Queensland, and Therésa Jones, Professor in Evolution and Behaviour, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

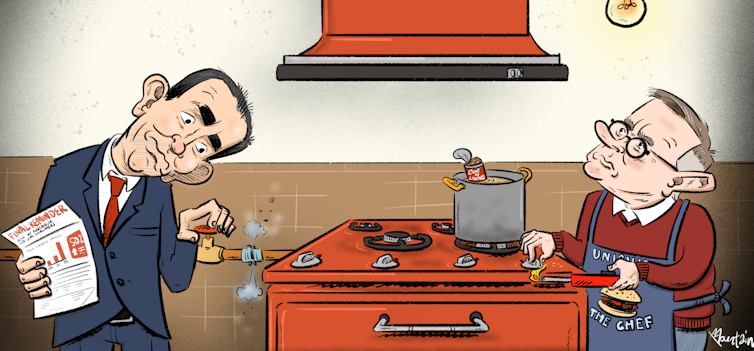

Wholesale power prices are falling fast – but consumers will have to wait for relief. Here’s why

Wholesale power prices are falling steeply in Australia, following two years of surging prices after the Ukraine war triggered an energy crisis. New data shows annualised spot prices for power in Australia’s main grid fell by about 50% in 2023. That brings the cost of wholesale power down towards the levels seen in 2021.

Is that good news for consumers? It will be – but not yet. Energy retailers buy most of their power in advance at set prices, accepting higher average prices for less volatility. That means the cheaper spot prices won’t flow through to you for a while. But they will.

Here’s how the system works.

How Is Power Priced?

The way we price electricity will be different depending where you live in Australia.

If you live in Tasmania, Western Australia, regional Queensland or in the Northern Territory, there’s no competition. The state or territory government runs the power system, and prices are set by a regulator.

In South Australia, Victoria, New South Wales, and south-east Queensland, the competitive National Energy Market applies. Here, retailers buy power on the wholesale spot market from generators and compete for your business by offering different prices and bundling electricity with other services such as gas or broadband. (Some energy companies are both generators and retailers.)

While the federal government doesn’t set prices in the market, it does have some involvement. In 2019, it introduced a mandatory default market offer, effectively setting a maximum price a retailer can charge customers. Victoria also implemented its own default offer. These changes stemmed from concerns retail competition was overly complicated and not delivering benefits to all electricity consumers.

Default offers were intended as a fair price for power and to work as a safety net so consumers weren’t overcharged.

Retailers compete in part by offering deals set below the default price. Nearly all of us have now signed up for market offers, leaving fewer than 10% of consumers still on a default offer.

The price of electricity in default offers is set by energy regulators, usually on 1 July each year. Competing retailers tend to mirror changes to the default offers in their market offers. That means most, if not all, consumers should start seeing lower default prices reflected in their bills from this date onwards.

But don’t expect falling wholesale prices to be passed on immediately or in full. Buying electricity wholesale is only around 40% of a retailer’s total cost. Retailers also pass through the costs of transmission and distribution.

Ironing Out Fluctuations

In the National Energy Market, the spot price of power changes every five minutes – often drastically. Prices can be as low as negative A$1,000 per megawatt hour or as high as +$16,000 a megawatt hour if there are outages or intense demand during a heatwave. (Prices can turn negative if there’s an oversupply of power, such as when millions of rooftop solar arrays are putting energy into the grid in the middle of the day, and act as an incentive to boost demand or cut supply.)

You and I don’t want to be exposed to such price volatility. We rely on our retailers to do it, and they do so by taking out multi-year contracts to smooth out the price of power.

That means we are not exposed immediately to sudden increases in price, but it also means we do not benefit from rapid falls. Retail prices, including default offers, will respond to changes in wholesale prices when those changes are reflected in the retailers’ contract prices.

What About Politics?

Power prices are political. Everyone uses electricity and bill shock hurts.

At present, the Albanese government is under real pressure over the cost of living. Successive interest rate rises and more expensive petrol and groceries have left many of us feeling poorer.

Could there be direct intervention? Unlikely. Since the National Electricity Market was introduced in 1998, governments have avoided directly regulating prices.

When partial interventions are tried, they tend to have little impact. When the Coalition was in office federally, they introduced the so-called Big Stick laws, aimed at forcing energy retailers to pass on cost savings. To date, the laws have gathered dust.

What we can expect to see are calls to action. For instance, South Australia’s energy minister recently called on retailers to pass on price falls as quickly as possible.

This makes headlines and can put pressure on regulators such as the Australian Energy Regulator. We can expect the pressure of the election cycle to lead to even more calls for regulators to act.

But regulators should respond in line with their clear guidelines, rather than in response to political pressure. After all, governments have given regulators a difficult job to do: deliver fair prices in a rapidly evolving electricity market.

It would be better for the long-term interests of consumers and energy suppliers if they were allowed to get on with it.

What’s Next?

As more clean energy comes into the grid, it should push wholesale prices still lower. But the energy transition isn’t as simple as substituting solar and wind for coal. Big investments in transmission and energy storage are needed to connect more renewables and maintain a reliable system. Prices could once again rise sharply if our ageing coal plants give up the ghost before there’s enough renewable generation and storage to take up the slack.

These challenges and risks were inevitable given the scale of our net-zero transition. But the recent trend towards lower prices should give us confidence that more investment in renewables and storage can cover the closure of coal to deliver a reliable, low-emissions future – without threatening affordability. ![]()

Tony Wood, Program Director, Energy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

First Nations people must be at the forefront of Australia’s renewable energy revolution

Adam Fish, UNSW Sydney and Heidi Norman, UNSW SydneyAustralia’s plentiful solar and wind resources and proximity to Asia means it can become a renewable energy superpower. But as the renewable energy rollout continues, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people must benefit.

Renewables projects can provide income and jobs to Aboriginal land owners. Access to clean energy can also help First Nations people protect their culture and heritage, and remain on Country.

This is not a new idea. Policies in the United States and Canada, for example, actively seek to ensure the energy transition delivers opportunities to Indigenous people.

The Australian government is developing a First Nations Clean Energy Strategy and is seeking comment on a consultation paper. Submissions close tomorrow, February 9. If you feel strongly about the issue, we urge you to have your say.

We must get this policy right. Investing meaningfully in First Nations-led clean energy projects makes the transition more likely to succeed. What’s more, recognising the rights and interests of First Nations people is vital to ensuring injustices of the past are not repeated.

Good For Business, And People

Indigenous peoples have recognised land interests covering around 26% of Australia’s landmass. Research shows Aboriginal land holders want to be part of the energy transition. But they need support and resources.

This could take the form of federal grants to make communities more energy-efficient or less reliant on expensive, polluting diesel generators. Funding could also be spent on workforce training to ensure First Nations people have the skills to take part in the transition. Federal agencies could be funded to support grants for First Nations feasibility studies of renewable energy industry on their land.

As well as proper investment, governments must also ensure First Nations people are engaged early in the planning of renewable projects and that the practice of free prior and informed consent is followed. And renewable energy operators will also need to ensure they have capability to work with First peoples.

The First Nations Clean Energy Network – of which one author, Heidi Norman, is part – is a network of First Nations people, community organisations, land councils, unions, academics, industry groups and others. It is working to ensure First Nations communities share the benefits of the clean energy boom.

The network is among a group of organisations calling on the federal government to invest an additional A$100 billion into the Australian renewables industry. The investment should be designed to benefit all Australians, including First Nations people.

In Australia, the Albanese government has set an emissions-reduction goal of a 43% by 2030, based on 2005 levels. But Australia’s renewable energy rollout is not happening fast enough to meet this goal. Climate Change Minister Chris Bowen has called for faster planning decisions on renewable energy projects.

To achieve the targets, however, the federal government must bring communities along with them – including First Nations people.

As demonstrated by the US and Canada, investing meaningfully and at scale in First Nations-led clean energy projects is not just equitable, it makes good business sense.

Follow The Leaders

The US Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 made A$520 billion in investments to accelerate the transition to net zero. Native Americans stand to receive hundreds of billions of dollars from the laws. This includes funding set aside for Tribal-specific programs.

Canada is even further ahead in this policy space. In fact, analysis shows First Nations, Métis and Inuit entities are partners or beneficiaries of almost 20% of Canada’s electricity-generating infrastructure, almost all of which is producing renewable energy. In one of the most recent investments, the Canadian government in 2022 invested C$300 million to help First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples launch clean energy projects.

Policymakers in both countries increasingly realise that a just transition from fossil fuels requires addressing the priorities of First Nations communities. These investments are a starting point for building sustainable, globally competitive economies that work for everyone.

As the US and Canada examples demonstrate, the right scale of investment in First Nations-led projects can mean fewer legal delays and a much-needed social licence to operate.

Dealing With The Climate Risk

First Nations people around the world are on the frontline of climate change. It threatens their homelands, food sources, cultural resources and ways of life.

First Nations have also experienced chronic under-investment in their energy infrastructure by governments over generations, both in Australia and abroad.

Investing in First Nations-led clean energy projects builds climate resilience. This was demonstrated by the federal government’s Bushlight program, which ran from 2002 to 2013. It involved renewable energy systems installed in remote communities in the Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland.

Bushlight’s solar power meant that communities were not dependent on the delivery of diesel. So they still had power if roads were closed by flooding or other climate disasters.

Australia Must Get Moving

The Biden government’s Inflation Reduction Act prompted a swift reaction from governments around the world. But after 15 months, Australia is yet to respond or develop equivalent legislation.

We must urgently develop our response and seize this unique opportunity to become world leaders in the global renewables race. That includes ensuring First Nations participate in and benefit from these developments.

The First Nations Clean Energy Strategy consultation paper can be found here. Feedback can be provided here.![]()

Adam Fish, Associate Professor, School of Arts and Media, UNSW Sydney and Heidi Norman, Professor, Faculty of Arts, Design and Architecture, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

El Niño is starting to lose strength after fueling a hot, stormy year, but it’s still powerful − an atmospheric scientist explains what’s ahead for 2024

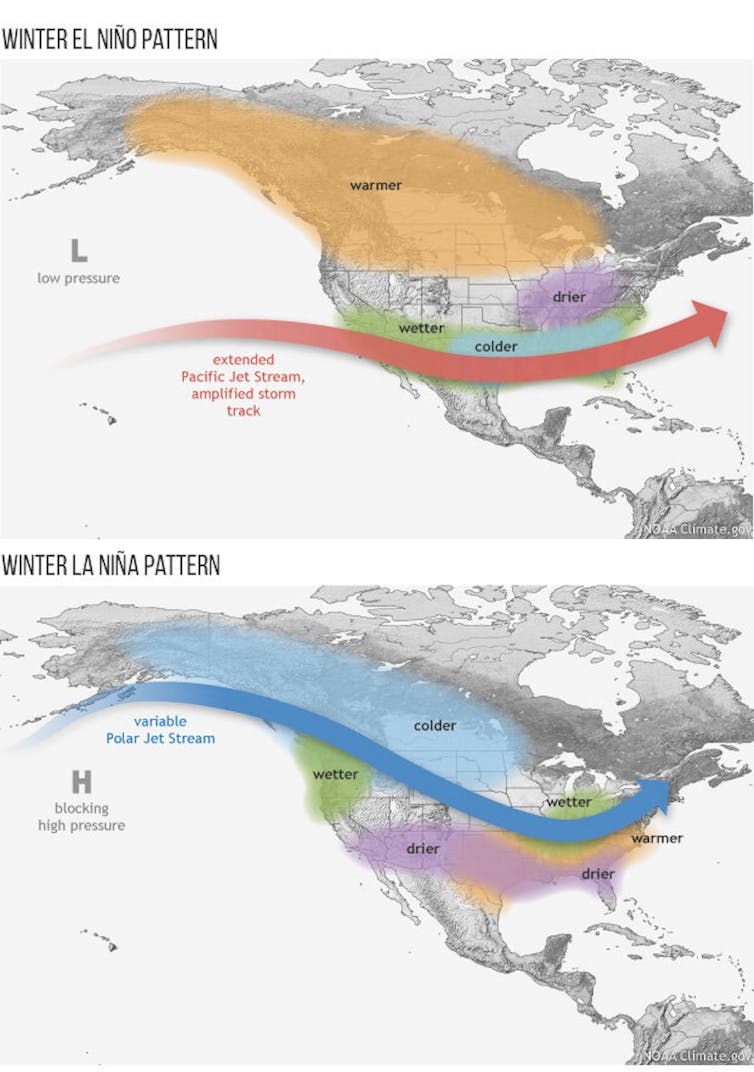

Wild weather has been roiling North America for the past few months, thanks in part to a strong El Niño that sent temperatures surging in 2023. The climate phenomenon fed atmospheric rivers drenching the West Coast and contributed to summer’s extreme heat in the South and Midwest and fall’s wet storms across the East.

That strong El Niño is now starting to weaken and will likely be gone by late spring 2024.

So, what does that mean for the months ahead – and for the 2024 hurricane season?

What Is El Niño?

Let’s start with a quick look at what an El Niño is.

El Niño and its opposite, La Niña, are climate patterns that influence weather around the world. El Niño tends to raise global temperatures, as we saw in 2023, while La Niña events tend to be slightly cooler. The two result in global temperatures fluctuating above and below the warming trend set by climate change.

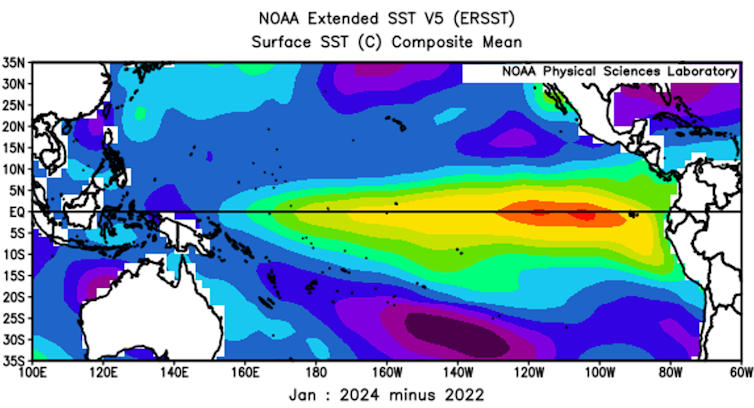

El Niño starts as warm water builds up along the equator in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, off South America.

Typically, tropical Pacific winds blow from the east, exposing cold water along the equator and building up warm water in the western Pacific. Every three to seven years or so, however, these winds relax or turn to blow from the west. When that happens, warm water rushes to the east. The warmer-than-normal water drives more rainfall and alters winds around the world. This is El Niño.

The water stays warm for several months until, ultimately, it cools or is driven away from the equator by the return of the trade winds.

When the eastern Pacific region along the equator becomes abnormally cold, La Niña has emerged, and global weather patterns change again.

What To Expect From El Niño In 2024

While the 2023-24 El Niño event likely peaked in December, it is still strong.

For the rest of winter, forecasts suggest that strong El Niño conditions will likely continue to favor unusual warmth in Canada and the northern United States and occasional stormy conditions across the southern states.

El Niño is likely to end in late spring or early summer, shifting briefly to neutral. There’s a good chance we will see La Niña conditions this fall. But forecasting when that happens and what comes next is harder.

How An El Niño Ends

While it’s easy to tell when an El Niño event reaches its peak, predicting when one will end depends on how the wind blows, and everyday weather affects the winds.

The warm area of surface water that defines El Niño typically becomes more shallow toward spring. In mid-May 1998, at the end of an even stronger El Niño event, there was a time when people fishing in the warm surface water in the eastern tropical Pacific could have touched the cold water layer a few feet below by just jumping in. At that point, it took only a moderate breeze to pull the cold water to the surface, ending the El Niño event.

But exactly when a strong El Niño event reverses varies. A big 1983 El Niño didn’t end until July. And the El Niño in 1987 retreated into the central Pacific but did not fully reverse until December.

As of early February 2024, strong westerly winds were driving warm water from west to east across the equatorial Pacific.

These winds tend to make El Niño last a little longer. However, they’re also likely to drive what little warm water remains along the equator out of the tropics, up and down the coasts of the Americas. The more warm water that is expelled, the greater the chances of full reversal to La Niña conditions in the fall.

Summer And The Hurricane Risk

Among the more important El Niño effects is its tendency to reduce Atlantic hurricane activity.

El Niño’s Pacific Ocean heat affects upper level winds that blow across the Gulf of Mexico and the tropical Atlantic Ocean. That increases wind shear - the change in wind speed and direction with height – which can tear hurricanes apart.

The 2024 hurricane season likely won’t have El Niño around to help weaken storms. But that doesn’t necessarily mean an active season.

During the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season, El Niño’s effect on the winds was more than offset by abnormally warm Atlantic waters, which fuel hurricanes. The season ended with more storms than average.

The Strange El Niño Of 2023-24

Although the 2023-24 El Niño event wasn’t the strongest in recent decades, many aspects of it have been unusual.

It followed three years of La Niña conditions, which is unusually long. It also emerged quickly, from March to May 2023. The combination led to weather extremes unseen since perhaps the 1870s.

La Niña cools the tropics but stores warm water in the western Pacific. It also warms the middle latitude oceans by weakening the winds and allowing more sunshine through. After three years of La Niña, the rapid emergence of El Niño helped make the Earth’s surface warmer than in any recent year.![]()

Paul Roundy, Professor of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University at Albany, State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In Chile, huge wildfires have killed at least 131 people – but one village was almost untouched

Yasna Palmeiro Silva, UCLChile has experienced one of the worst fire-related disasters in its history. A series of huge forest fires burned from February 1 to 5, leaving at least 131 people dead – and this number will probably increase as charred bodies are collected and severely injured people die.

But even this is only the tip of the iceberg. There are people with burns, post-traumatic stress and other mental health disorders. Existing diseases have been exacerbated by service interruptions, and people have lost their homes and livelihoods. Also, the long-term effects from smoke inhalation are yet to be seen.

This is not really a “climate disaster”, nor even a “natural disaster”. It is a disaster mainly caused by our decisions and lack of preparation to deal with a more extreme climate hazard. As an academic disaster researcher from Chile, I think there are lessons we can learn from these fires.

So, why did things become so deadly?

Fire-Prone Conditions

The weather, of course, played a role. Meteorological conditions have made Chile very prone to fires this summer, especially in this long-and-thin country’s central region, where it is warm enough for fires yet wet enough for there to be vegetation to burn.

Temperatures were high, above 35°C for more than three days before and during the fires in some places. Conditions were dry on top of a longer-term mega-drought, and relative humidity was low. It was also very windy.

It is very likely that these conditions have been influenced by El Niño, on top of human-induced climate change. However, even when fire danger is extremely high, fires can still be prevented from happening, expanding, or being deadly. But to achieve this, other factors are needed in this formula: social factors.

Formula For A (Not Natural) Perfect Disaster

My colleague Ilan Kelman has defined disasters as “where the ability of people to cope with a hazard or its impacts by using their own resources is exceeded”. This is exactly what happened in Chile: a deadly combination of an extreme climate hazard and inadequate social preparation.

In addition, regional authorities and the national government have suggested that some fires were ignited intentionally, as there were four simultaneous outbreaks and a state prosecutor claims that fire accelerants paraffin and benzine have been discovered. No arrests have been made.

The most devastating fires occurred in urbanising areas with significant land-use change, and where urban planning regulation has always been inadequate – leading to houses with no building regulation, and narrow streets with limited access to emergency services when needed.

There was also limited preparation for the expected hot season, either in the form of seasonal public campaigns for heatwaves and fires, or evacuation routes and plans.

Chile’s national early warning system, which sends a mass alert via text, audio and vibration to everyone who uses a compatible mobile device, also faced challenges. Several antennas were affected by the fires and not properly working, so many people did not receive the message on time. And those messages that were sent only said “evacuate”, so many people did not know where to go. This led to traffic jams and bottlenecks, some of which became engulfed in the middle of the fires.

Climate-Related Hazards Shouldn’t Turn Disastrous

Climate change means it is likely that Chile will be even more prone to huge fires in future. However, the human health risks this poses can be reduced by adequate preparedness and response plans.

Villa Botania, near the city of Quilpué in central Chile, emerged from these fires as an interesting example to learn from. This little village was surrounded by flames but was almost unaffected.

That’s because residents were prepared. A community-led project had managed waste and controlled vegetation and weeds, to ensure there was less flammable material when a fire passed by. Villa Botania demonstrated that a climate-related hazard does not always end in a massive human disaster, and lessons can be learned from this.

Chile recently created a national policy on disaster risk reduction, but it still needs to factor disaster risk and climate change into its planning regulations. This can save lives, as shown by the success since the 1970s of anti-seismic building regulations in this earthquake-prone country.

In a changing climate, we need to prepare the systems that prevent a disaster from occurring in the first place. This is sometimes forgotten, as most resources go to the response phase once it has occurred. However, Chile’s recent fires have again demonstrated that the twin threat of changing climate and inadequate social preparedness poses a serious danger to the health and wellbeing of many people.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 30,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Yasna Palmeiro Silva, Research Fellow, Institute for Global Health, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Heart attacks, cancer, dementia, premature deaths: 4 essential reads on the health effects driving EPA’s new fine particle air pollution standard

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has announced a new standard for protecting the public from fine particulate air pollution, known as PM2.5 because the particles are smaller than 2.5 millionths of a meter. These minute particles can penetrate deeply into the body and have been linked to many serious illnesses.

The new rule sets an annual limit of 9 micrograms per cubic meter of air, down from the previous level of 12 micrograms. States will be required to meet this standard and to take it into consideration when they evaluate applications for permits for new stationary air pollution sources, such as electric power plants, factories and oil refineries.

Under the Clean Air Act, the EPA is required to set air pollution standards at levels that protect public health. In the four articles that follow, scholars wrote about the many ways in which exposure to PM2.5 contributes to cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, other illnesses such as dementia, and premature deaths.

1. An Alarming Array Of Health Effects

Scientists have known since the 1993 Six Cities Study, which showed that people were dying faster in dirty cities than in clean cities, that exposure to PM2.5 increased the risk of lung cancer and heart disease. Subsequent research has linked fine particulates to a much broader range of health effects.

Once a person inhales PM2.5, “it causes an inflammatory response that sends signals throughout the body, much as a bacterial infection would,” wrote public and environmental health scholars Doug Brugge of the University of Connecticut and Kevin James Lane of Boston University. “Additionally, the smallest particles and fragments of larger particles can leave the lungs and travel through the blood.”

In Brugge and Lane’s view, evidence that PM2.5 could affect brain development, cognitive skills and children’s central nervous systems is particularly notable. They termed fine particle pollution an urgent global health threat.

“Developed countries have made progress in reducing particulate air pollution in recent decades, but much remains to be done to further reduce this hazard,” they observed. “And the situation has gotten dramatically worse in many developing countries – most notably China and India, which have industrialized faster and on vaster scales than ever seen before.”

2. Aging The Brain

Medical researchers are looking closely at air pollution as a possible accelerator of brain aging. University of Southern California preventive medicine specialist Jiu-Chiuan Chen and his colleagues have found that older women who lived in locations with high levels of PM2.5 suffered memory loss and Alzheimer’s-like brain shrinkage not seen in women living with cleaner air.

Chen and his colleagues compared brains scans taken at five-year intervals of older women who lived in areas with varying levels of air pollution.

“When we compared the brain scans of older women from locations with high levels of PM2.5 to those with low levels, we found dementia risk increased by 24% over the five years,” Chen wrote.

More alarmingly, “(T)hese Alzheimer’s-like brain changes were present in older women with no memory problems,” Chen noted. “The shrinkage in their brains was greater if they lived in locations with higher levels of outdoor PM2.5, even when those levels were within the current (2021) EPA standard.”

3. Disadvantaged Communities Have Dirtier Air

As researchers in environmental justice have shown, facilities such as factories and refineries often are concentrated in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. This means that these areas are exposed to higher pollution levels and face heavier related health burdens.

Regulations put in place under the Clean Air Act have greatly reduced levels of harmful air pollutants across the U.S. over the past 50 years. But when University of Virginia economist Jonathan Colmer and public policy scholar Jay Shimshack analyzed data tracing PM2.5 concentrations at more than 8.6 million distinct U.S. locations from 1981 through 2016, they found that the areas that were most polluted in 1981 remained the dirtiest nearly 40 years later.

“In 1981 PM2.5 concentrations in the most polluted 10% of census tracts averaged 34 micrograms per cubic meter,” the authors reported. “In 2016 PM2.5 concentrations in the most polluted 10% of census tracts averaged 10 micrograms per cubic meter. PM2.5 concentrations in the least polluted 10% of census tracts averaged 4 micrograms per cubic meter.” In other words, while all areas had cleaner air, people in the most polluted areas still were exposed to PM2.5 levels more than twice as high as people in the cleanest zones.

“For decades, federal and state environmental guidelines have aimed to provide all Americans with the same degree of protection from environmental hazards,” Colmer and Shimshack note. “The EPA’s definition of environmental justice states that ‘no group of people should bear a disproportionate share of the negative environmental consequences.’ On this front, our research suggests that the United States is falling short.”

4. Fine Particle Pollution Hurts Wildlife Too

Like the proverbial canaries in coal mines, wild animals can show effects of exposure to pollution that offer broader warnings. One example is wildfires, which produce high levels of gases and particulate matter.

Cornell University conservation biologist Wendy M. Erb was studying wild orangutans in Indonesian Borneo when that island suffered large-scale wildfires. Orangutans are semi-solitary animals that communicate with each other through long, booming calls in the tropical forests where they live.

During the fires and for several weeks after the smoke cleared, Erb and her colleagues found that four male orangutans they were following called less frequently than usual – about three times daily instead of their usual six times. “Their voices dropped in pitch, showing more vocal harshness and irregularities,” Erb reported. “Collectively, these features of vocal quality have been linked to inflammation, stress and disease – including COVID-19 – in human and nonhuman animals.”

Erb hoped to see further study of how toxic smoke affects wildlife. “Using passive acoustic monitoring to study vocally active indicator species, like orangutans, could unlock critical insights into wildfire smoke’s effects on wildlife populations worldwide,” she observed.

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archive.![]()

Jennifer Weeks, Senior Environment + Cities Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dangerous climate tipping points will affect Australia. The risks are real and cannot be ignored

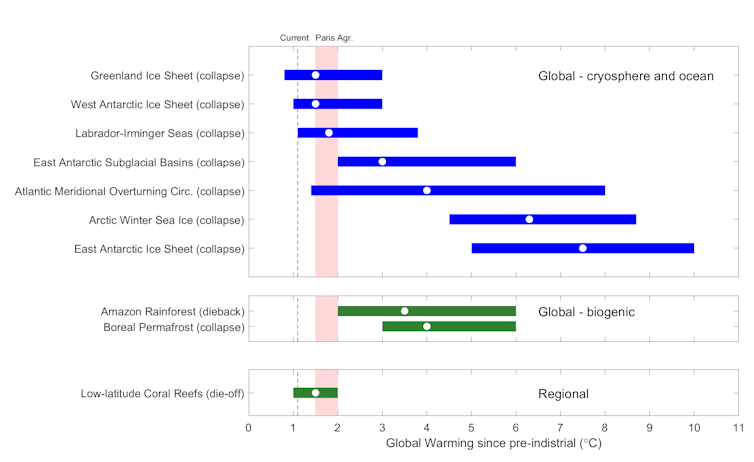

Michael Grose, CSIRO and Andy Pitman, UNSW SydneyIn 2023, we saw a raft of news stories about climate tipping points, including the accelerating loss of Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, the potential dieback of the Amazon rainforest and the likely weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Ocean Circulation.

The ice sheets, Amazon rainforest and the Atlantic ocean circulation are among nine recognised global climate tipping elements. Once a tipping point is crossed, changes are often irreversible for a very long time. In many cases, additional greenhouse gases will be released into the atmosphere, further warming our planet.

New scientific research and reviews suggest at least one of Earth’s “tipping points” could be closer than we hoped. A milestone review of global tipping points was launched at last year’s COP28.

What will these tipping points mean for Australia? We don’t yet have a good enough understanding to fully answer this question.

Our report, released overnight, includes conclusions in three categories: we need to do more research; tipping points must be part of climate projections, hazard and impact analyses; and adaptation plans must take the potential impacts into account.

What Are Climate Tipping Points?

Climate scientists have known for a while, through paleoclimate records and other evidence, that there are “tipping elements” in the climate system. These elements can undergo an abrupt change in state, which becomes self-perpetuating and irreversible for a very long time.

An example is the loss of Greenland ice. Once ice is lost, climate feedbacks lead to further loss, and major ice loss becomes “committed”. It becomes unlikely the ice sheet will reform for tens of thousands of years and only if the climate cools again.

Triggering climate tipping points would lead to changes in addition to those commonly included in climate projections. These changes include a significant rise in sea level at double the rate (or even more) of usual projections, as well as extra warming, altered weather systems, climate variability and extremes.

Triggering one tipping point may trigger other tipping points. If that happens, the cascading impacts would push many systems outside their adaptive capacity.

Cutting fossil greenhouse gas emissions is the most important thing we can do to limit warming and the risk of triggering tipping points. The faster we reduce emissions, the better our chances.

But as the planet continues to warm, we must consider the consequences of triggering some, or several, tipping points for Australia and the resulting risks for society. We need to have the right tools for adaptation planning to consider these risks.

Grappling With Deep Uncertainties

There’s a major gap in the research literature around the implications of tipping points for the southern hemisphere and Australia. Researchers from Australian science agencies and universities came together last year to consider what global climate tipping points could mean for Australia.

We launched our report last night at the national conference of the Australian Meteorological & Oceanographic Society. We identified several priority areas for the research community, risk analysts and policymakers.

We considered the nine global climate tipping points – and one of the most relevant regional tipping points for Australia, coral reef die-offs – as defined in a recent scientific review.

For almost all tipping points, we don’t understand all the relevant processes. There are deep uncertainties about what conditions would trigger tipping points, how they would play out and their likely impacts.

Along with recognising the most urgent point – that deep emission cuts will limit the chances of triggering tipping points – our conclusions cover three areas.

1. We need more research

We need to expand research on paleoclimate records, theory and process understanding, observations, monitoring and modelling. Australia leads world-class research, including on Antarctica, the Southern Ocean, the carbon cycle, weather processes and ecosystems. It is essential we support and expand the work, bringing a southern hemisphere perspective to global efforts.

2. Climate projections, hazard and impact analyses must include tipping points

Triggering some climate tipping points would have direct impacts on our coasts, ecosystems and society. In an interconnected world, other tipping points would have major indirect impacts – through climate migration, conflict, disrupted trade and more.

We need credible projections of what the climate looks like if tipping points are triggered. Our climate impact and risk analyses should illustrate what it really means for us. Given the limited state of knowledge, the “storyline” approach – linking past, current and future unfolding of events in a narrative or pathway framework – is particularly useful, informed by all the available evidence.

3. We need to consider what it means for adaptation

We can consider where, when and how we can act to reduce potential impacts if tipping points are triggered. Appropriate risk management accounts for likelihood, consequence and timeframe.

For example, planning for major coastal infrastructure with a long lifetime and low tolerance for failure could draw on the sea-level projections of “low likelihood, high impact” storylines that include the west Antarctic ice sheet collapsing. This would safeguard critical infrastructure against one worst-case risk. Of course, there is much more to adaptation than this.

We still have much to learn, but we cannot wait for perfect knowledge before we start planning. It’s clear the risks are real and cannot be ignored.

We need to focus on what we can do to avoid triggering tipping points, manage risk and build our climate resilience. There are also positive tipping points in technology, economy and society that are part of the solution. If we get it right, positive change can happen more rapidly than we might think.![]()

Michael Grose, Climate Projections Scientist, CSIRO and Andy Pitman, Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘A deeply troubling discovery’: Earth may have already passed the crucial 1.5°C warming limit

Malcolm McCulloch, The University of Western AustraliaGlobal temperatures have already exceeded 1.5°C warming and may pass 2°C later this decade, according to a world-first study I led. The worrying findings, based on temperature records contained in sea sponge skeletons, suggest global climate change has progressed much further than previously thought.

Human-caused greenhouse gas emissions drive global warming. Obtaining accurate information about the extent of the warming is vital, because it helps us understand if extreme weather events are more likely in the near future, and whether the world is making progress in reducing emissions.

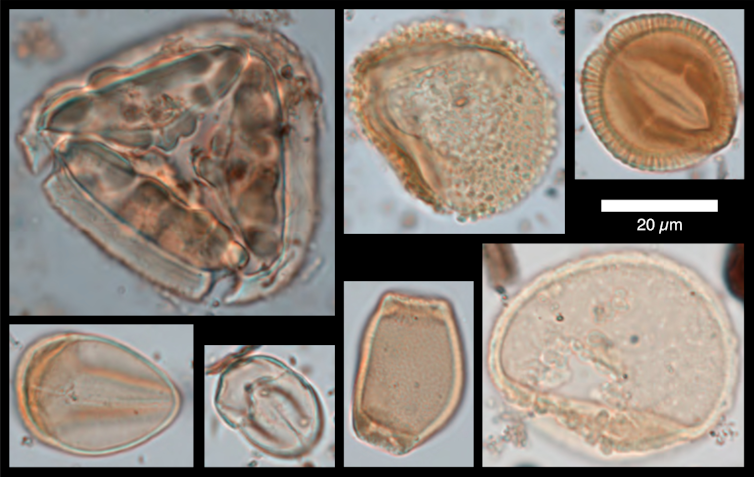

To date, estimates of upper ocean warming have been mainly based on sea-surface temperature records, however these date back only about 180 years. We instead studied 300 years of records preserved in the skeletons of long-lived sea sponges from the Eastern Caribbean. In particular, we examined changes in the amount of a chemical known as “strontium” in their skeletons, which reflects variations in seawater temperatures over the organism’s life.

Keeping the average global temperature rise below 1.5°C since pre-industrial times is a goal of the 2015 Paris climate deal. Our research, published in Nature Climate Change, suggests that opportunity has passed. Earth may in fact have already reached at least 1.7°C warming since pre-industrial times – a deeply troubling discovery.

Getting A Gauge On Ocean Heat

Global warming is causing major changes to the Earth’s climate. This was evident recently during unprecedented heatwaves across southern Europe, China and large parts of North America.

Oceans cover more than 70% of Earth’s surface and absorb an enormous amount of heat and carbon dioxide. Global surface temperatures are traditionally calculated by averaging the temperature of water at the sea surface, and the air just above the land surface.

But historical temperature records for oceans are patchy. The earliest recordings of sea temperatures were gathered by inserting a thermometer into water samples collected by ships. Systematic records are available only from the 1850s – and only then with limited coverage. Because of this lack of earlier data, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has defined the pre-industrial period as from 1850 to 1900.

But humans have been pumping substantial levels of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere since at least the early 1800s. So the baseline period from which warming is measured should ideally be defined from the mid-1700s or earlier.

What’s more, a series of exceptionally large volcanic eruptions occurred in the early 1800s, causing massive global cooling. This makes it more difficult to accurately reconstruct stable baseline ocean temperatures.

But what if there was a way to precisely gauge ocean temperatures over centuries in the past? There is, and it’s called “sclerosponge thermometry”.

Studying A Special Sponge

Sclerosponges are a group of sea sponges that resemble hard corals, in that they produce a carbonate skeleton. But they grow at a much slower rate and can live for many hundreds of years.

The skeletons incorporate a number of chemical elements including strontium and calcium. The ratio of these two elements varies during warmer and cooler periods. This means sclerosponges can provide a detailed diary of sea temperatures, down to a resolution of just 0.1°C.

We studied the sponge species Ceratoporella nicholsoni. They occur in the Eastern Caribbean, where the natural variability of upper ocean temperatures is low which makes it easier to tease out the effects of climate change. We wanted to investigate temperatures in a part of the ocean known as the “ocean mixed layer”. This is the upper part of the ocean, where heat is exchanged between the atmosphere and the ocean interior.

We looked at temperatures going back 300 years, to see whether the current time period which defines pre-industrial temperatures was accurate. So what did we find?

The sponge records showed nearly constant temperatures from 1700 to 1790 and from 1840 to 1860 (with a gap in the middle due to volcanic cooling). We found a rise in ocean temperatures began from the mid-1860s, and was unambiguously evident by the mid-1870s. This suggests the pre-industrial period should be defined as the years 1700 to 1860.

The implications of these findings are profound.

What Does This Mean For Global Warming?

Using this new baseline, a very different picture of global warming emerges. It shows human-caused ocean warming began at least several decades earlier than previously assumed by the IPCC.

Long-term climate change is commonly measured against the average warming over the 30 years from 1961 to 1990, as well as warming in more recent decades.

Our findings suggest that in the interval between the end of our newly defined pre-industrial period and the 30-year average mentioned above, the temperatures of the ocean and land surface increased by 0.9°C. This is far more than the 0.4°C warming the IPCC has estimated, using the conventional timeframe for the pre-industrial period.

Add to that the average 0.8°C global warming from 1990 to recent years, and the Earth may have warmed on average by at least 1.7°C since pre-industrial times. This suggests we have passed the 1.5°C goal of the Paris Agreement.

It also suggests the overriding goal of the agreement, to keep average global warming below 2°C, is now very likely to be exceeded by the end of the 2020s – nearly two decades sooner than expected.

Our study has also produced another alarming finding. Since the late 20th century, land-air temperatures have been increasing at almost twice the rate of surface oceans and are now more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels. This is consistent with well-documented decline in Arctic permafrost and the increased frequency around the world of heatwaves, bushfires and drought.

We Must Act Now

Our revised estimates suggest climate change is at a more advanced stage than we thought. This is cause for great concern.

It appears that humanity has missed its chance to limit global warming to 1.5°C and has a very challenging task ahead to keep warming below 2°C. This underscores the urgent need to halve global emissions by 2030.![]()

Malcolm McCulloch, Professor, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is it time for a Category 6 for super cyclones? No – warnings of floods or storm surges are more useful

Liz Ritchie-Tyo, Monash UniversityWhen a tropical cyclone forms, people who live in its path anxiously monitor news of its direction – and strength. If a Category 5 storm with wind speeds of 250 kilometres per hour is heading for you, you prepare differently than you would for a Category 1 with wind speeds of 65 km/h.

In a hotter world, cyclones are expected to become less common but more intense when they do form. That, according to new research, means it might be time to consider introducing a Category 6 to the hurricane scale used in the United States to better communicate the threat.

But do cyclone scales need a new category for more severe storms? Only one hurricane in the Western Hemisphere has yet gone past the 309 km/h winds the researchers nominate for a Category 6. And the whole idea of storm scales, including Australia’s own tropical cyclone scale, is that Category 5 storms are those likely to do catastrophic damage. It’s hard to see what a Category 6 could offer.

What is worth exploring is how we can better communicate what specific threats a given storm poses. Is it carrying more water than average, making flooding a bigger risk? Or are unusually intense winds likely to bring more water ashore in storm surges?

In December, Cyclone Jasper made landfall as a Category 2 storm in northern Queensland. Despite being at the lower end of severity, it dumped huge volumes of water and triggered devastating floods. Residents and farmers criticised the Bureau of Meteorology for not fully conveying the size of the threat. More specific warnings could help.

What Are Storm Scales For?

The world’s tropical cyclone warning centres classify cyclones using simple intensity scale systems based on maximum wind thresholds. Cyclones, hurricanes and typhoons are different names for the same tropical storms.

There are several different intensity scales in use. The Saffir-Simpson scale is used by the US National Hurricane Center for hurricanes forming in the central and eastern North Pacific and North Atlantic basins. Different scales are used in the Australian, North Indian, Southwest Indian, and western North Pacific basins. Importantly, every scale in use is open-ended, meaning their final category is based on winds greater than a certain threshold – but with no upper limit.

Tropical cyclones can pose many threat to us while at sea, as they approach and make landfall, and even afterwards.

These threats include the intense winds near the eye of the tropical cyclone, the ring of damaging winds which can extend hundreds of kilometres from the eye, wind-driven high seas, storm surge, heavy rainfall and associated flooding and mudslides.

We can’t say one of these is definitively more deadly or damaging than any other threat. Tropical Cyclone Oswald, a 2013 Category 1 storm, led to heavy rainfall and flooding through Queensland and New South Wales, while the 1992 Category 5 Hurricane Andrew caused catastrophic wind damage – but little rain or storm surge damage when it hit Florida.

So Do We Really Need A Category 6?

The researchers suggest a Category 6 on the Saffir-Simpson scale would be for storms with winds over 86 metres per second (309 km/h).

They suggest five tropical cyclones have now passed that threshold since 2013. Certainly, Hurricane Patricia (2015) would meet that threshold. But this is the only one which meets their criteria in the last 40 years, as it was well observed by US aircraft missions. The other four were not in the Western Hemisphere – they were typhoons affecting Asia. In these areas, meteorologists do not use aircraft reconnaissance to confirm wind speeds. Estimates of wind speeds can vary substantially. That means the wind speeds of these four cannot be verified.

To make their case, the researchers also use the maximum possible intensity a tropical cyclone could reach in a given environment. It’s useful to scientists because it can be directly calculated from climate projections and is often used to explore how tropical cyclone intensity might change in the future. But it has an important limitation – tropical cyclones rarely reach their maximum potential intensity.

In their original formulation of the Saffir-Simpson scale, Herb Saffir and Bob Simpson described a Category 5 hurricane making landfall as one which would cause catastrophic destruction of all infrastructure. The Australian Tropical Cyclone Scale has different thresholds but similar reasoning for a Category 5 storm.

Based on the understanding that winds at Category 5 and above lead to catastrophic outcomes, it’s hard to see how adding a Category 6 would help the public. If a Category 5 means “expect catastrophic consequences”, what would Category 6 mean?

How Can We Best Communicate Cyclone Threats?

Scientists came up with tropical cyclone intensity scales as a way to clearly communicate the nature and size of the damage likely to occur. They are not intended to be comprehensive, as they’re based on a single wind speed valid only for the area near the eye, where the most intense winds occur.

Fundamentally, these scales are meant to measure how well our buildings and infrastructure can survive the wind force and also protect us. If our building codes, evacuation plans, and other protective strategies ever improved to the point where Category 5 storms no longer lead to catastrophic loss, it might make sense to introduce a Category 6. But we’re not at that point. The catastrophic loss from a Category 5 or Category 6 would look the same: catastrophic.

What we should do is explore whether we can improve the scale in different ways. Can we keep their simple, effective messages while also capturing the different threats a weather system like this can pose? ![]()

Liz Ritchie-Tyo, Professor of Atmospheric Sciences, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.