Inbox and Environment News: Issue 616

March 3 - 9, 2024: Issue 616

Increase Tree Vandalism Penalties: NSW Parliamentary Petition

.jpg?timestamp=1708790130470)

Lone Dollarbird - A Sign Of Autumn

.jpg?timestamp=1709266424435)

Avalon Beach Cockatoos

Adoption Of The Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park, Lion Island Nature Reserve, Long Island Nature Reserve And Spectacle Island Nature Reserve Plan Of Management

Protecting The Spirit Of Sea Country Bill 2023: Senate Inquiry

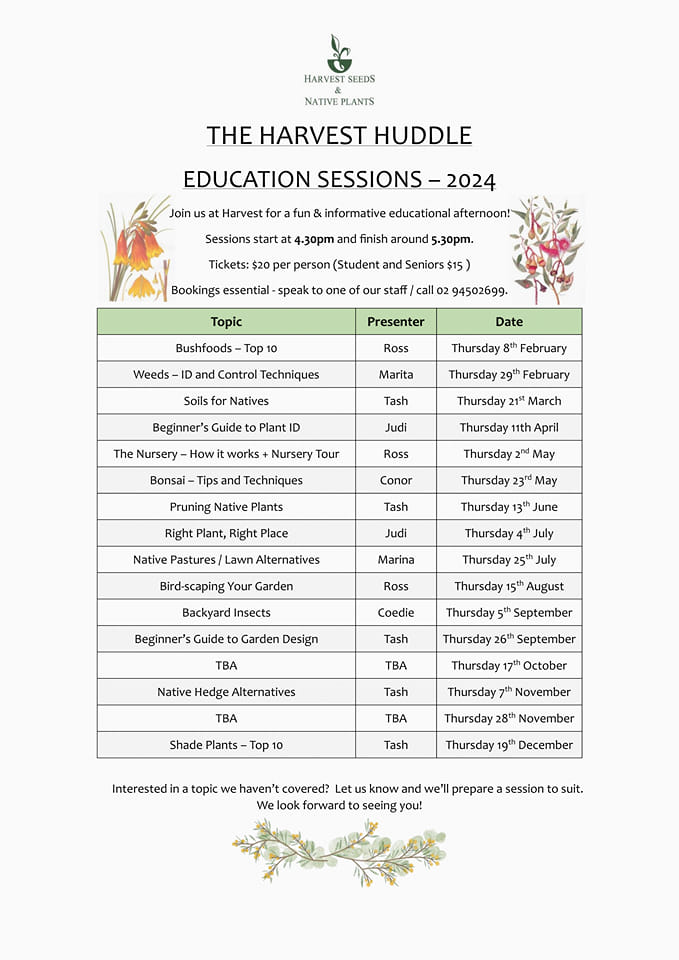

Harvest Seeds & Native Plants: Education Sessions 2024 - "The Harvest Huddle"

Notice Of 1080 Baiting: February 1 - July 31 2024

Please note the following notification of continuous and ongoing fox control using 1080 POISON with ground baits and canid pest ejectors (CPE’s) in Sydney Harbour National Park, Garigal National Park, Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, and Lane Cove National Park. As part of this program, baiting also occurs on North Head Sanctuary managed by Sydney Harbour Federation Trust and the Australian Institute of Police Management facility at North Head.

This provides notification for the 6 monthly period of 1 February 2024 – 31 July 2024.

Warning signs are displayed at park entrances and other entrances to the baiting location to inform the public of 1080 baiting.

1080 Poison for fox control is used in these reserves in a continuous and ongoing manner. This means that baits and ejectors (CPE’s) remain in the reserves and are checked/replaced every 6 – 8 weeks.

1080 use at these locations is in accordance with NSW pesticides legislation, relevant 1080 Pesticide Control Orders and the NPWS Vertebrate Pesticides Standard Operating Procedures.

A series of public notifications occur on a 6 monthly basis including; alerts on the NPWS website, public notices in local papers, Area pesticide use notification registers and to the NPWS call centre.

If you have any further general enquiries about 1080, or for specific program enquiries please contact the local NPWS Area office:

For further information please call the local NPWS office on:

NPWS Sydney North (Middle Head) Area office: 9960 6266

NPWS Sydney North (Forestville) Area office: 9451 3479

NPWS North West Sydney (Lane Cove NP) Area office: 8448 0400

NPWS after-hours Duty officer service: 1300 056 294

Sydney Harbour Federation Trust: 8969 2128

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association: Second PNHA Nature Event 2024

Clean Up Australia Day 2024 Registrations Are Now Open

NEW At Eco House & Garden(At Kimbriki): 'Supporting School & Community Composts Workshop'

Where you can become part of the (waste) solution in our 3-hour workshop.

See below for more details and for bookings go to 👉https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1162545

Kimbriki Resource Recovery Centre: Early Childhood Educators Professional Development Day

As part of Kimbriki's 2024 Eco House & Garden Educational Calendar, this year we introduce the Early Childhood Educators Professional Development Day on Friday 22nd March. For more details and bookings 👉 https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1162305

Upcoming Events At Permaculture Northern Beaches

Saving Our Seeds is a crucial part of our own food chain and it enables us to grow our own food and plants with no additional costs! The strongest seeds are locally grown over many generations and well adapted to local conditions - so your plants will thrive while you save on costs. Join us with seed-saving guest speakers Mylene Turban, and Elle Sheather to have an overview and to inspire you to get seed-saving!

Saving Our Seeds is a crucial part of our own food chain and it enables us to grow our own food and plants with no additional costs! The strongest seeds are locally grown over many generations and well adapted to local conditions - so your plants will thrive while you save on costs. Join us with seed-saving guest speakers Mylene Turban, and Elle Sheather to have an overview and to inspire you to get seed-saving!About

Stony Range Nursery

Stay Safe From Mosquitoes

- Applying repellent to exposed skin. Use repellents that contain DEET, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus. Check the label for reapplication times.

- Re-applying repellent regularly, particularly after swimming. Be sure to apply sunscreen first and then apply repellent.

- Wearing light, loose-fitting long-sleeve shirts, long pants and covered footwear and socks.

- Avoiding going outdoors during peak mosquito times, especially at dawn and dusk.

- Using insecticide sprays, vapour dispensing units and mosquito coils to repel mosquitoes (mosquito coils should only be used outdoors in well-ventilated areas)

- Covering windows and doors with insect screens and checking there are no gaps.

- Removing items that may collect water such as old tyres and empty pots from around your home to reduce the places where mosquitoes can breed.

- Using repellents that are safe for children. Most skin repellents are safe for use on children aged three months and older. Always check the label for instructions. Protecting infants aged less than three months by using an infant carrier draped with mosquito netting, secured along the edges.

- While camping, use a tent that has fly screens to prevent mosquitoes entering or sleep under a mosquito net.

Mountain Bike Incidents On Public Land: Survey

- Mountain Bike Incidents On Public Land: Survey Launched To Gather Data On What's Happening To Public Parks - Community Land - Bush Reserves In Pittwater

- Mother Brushtail Killed On Barrenjoey Road: Baby Cried All Night - Powerful Owl Struck At Same Time At Careel Bay During Owlet Fledgling Season: calls for mitigation measures - The List of 'What You can Do' as requested

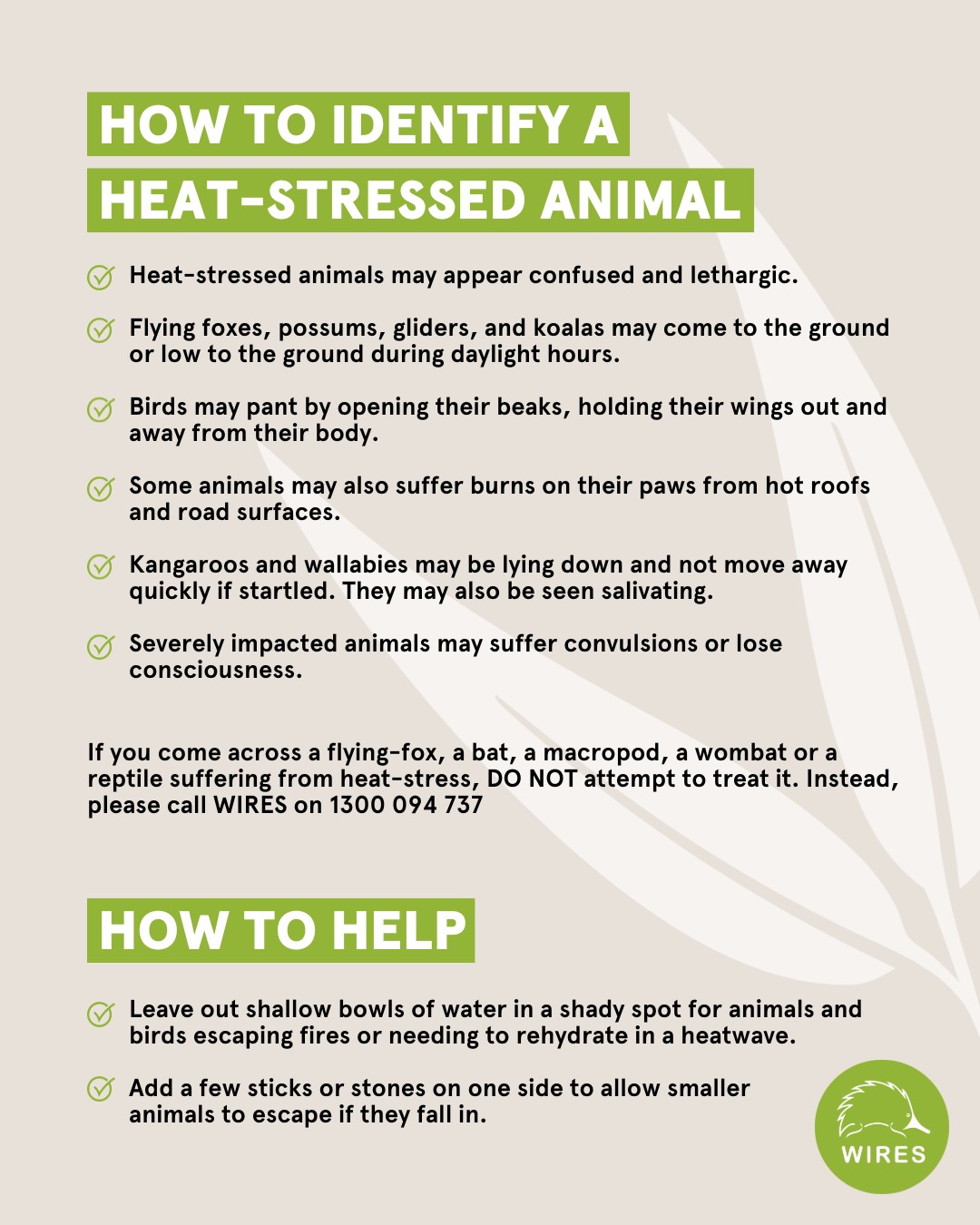

Please Look Out For Wildlife During Heatwave Events

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

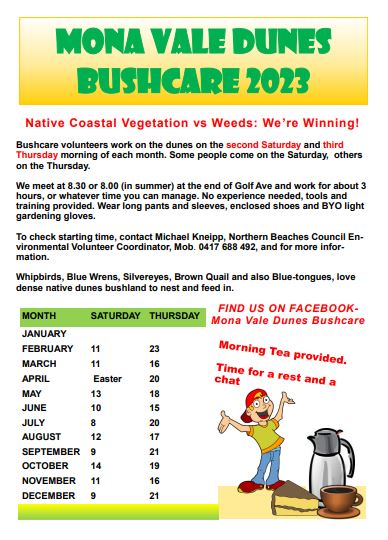

Bushcare In Pittwater: Where + When

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

- Ringtail Posse: 1 – February 2023; Anna Maria Monticelli: King Parrots/Water Dragons - Jacqui Scruby: Loggerhead Turtle - Lyn Millett OAM: Flying-Foxes - Kevin Murray: Our Backyard Frogs - Miranda Korzy: Brushtail Possums

- Ringtail Posse: 2 - March 2023; Kevin Murray: Tawny Frogmouth - Kayleigh Greig: Red-Bellied Black Snake - Bec Woods: Australian Water Dragon - Margaret Woods: Owlet-Nightjar - Hilary Green: Butcher Bird - Susan Sorensen: Wallaby

- Ringtail Posse 3 - April 2023: Jeffrey Quinn: Kookaburra, Tom Borg McGee: Kookaburra, Stephanie Galloway-Brown: Bandicoot, Joe Mills: Noisy Miner

- Ringtail Posse 4 May 2023 - Andrew Gregory: Powerful Owl, Marita Macrae: Pale-Lipped Or Gully Shadeskink, Jools Farrell: Whales & Seals, Nicole Romain: Yellow-Tailed Black Cockatoo

- Ringtail Posse 5: June 2023 - Lynleigh Greig OAM: Snakes, Dick Clarke: Diamond Python, Selena Griffith: Glossy Black-Cockatoo, Eric Gumley: Bandicoot

- Ringtail Posse 6: July 2023 - Sonja Elwood: Long-Nosed Bandicoot, Dr. Conny Harris: Swamp Wallaby, Neil Evers: Bandicoot, Bill Goddard: Bandicoot

- Ringtail Posse 7: August 2023 - Geoff Searl OAM: Tawny Frogmouth, Peter Macinnis: Echidna, Peter Carter: Ringtail Possum, Nathan Wellings; Kookaburra

- Ringtail Posse 8: September 2023 - Saving Sydney's Last Koalas; Logging Now Stopped In Future Koala Park By Minns Government - ''Is There Time To Save Sydney's Last Koalas Too?'' Asks: John Illingsworth, WIRES, Sydney Wildlife Rescue, Save Sydney Koalas, The Sydney Basin Koala Network, The Help Save The Wildlife & Bushlands In Campbelltown Group, Appin Koalas Animal Rescue Service, Patricia and Barry Durham, Sue Gay, Save Mt. Gilead, Paola Torti Of The International Koala Intervention Group

- Ringtail Posse 9: October 2023 - David Palmer OAM: Bandicoots, Helen Pearce: Brushtail Possum, Amina Kitching: Goanna, David Goudie: Ringtails Possums + Bandicoots + Owls

- Mother Brushtail Killed On Barrenjoey Road: Baby Cried All Night - Powerful Owl Struck At Same Time At Careel Bay During Owlet Fledgling Season: calls for mitigation measures - The List of what you can do for those who ask 'What You I Do' as requested

- Ringtail Posse 10: November 2023 - Stop Wildlife Roadkill Group: You Can Help By Using The Wildlife Incident Mapping Website

More Green Space To Enhance Liveability In NSW Communities: Metropolitan Greenspace Program + Community Gardens Program Grants Now Open

- Metropolitan Greenspace Program. All councils in the Greater Sydney region and Central Coast Council are eligible and encouraged to apply by 29 April 2024. Successful applicants will be announced in June 2024.

- Places to Roam Community Gardens program. Applications close on 29 March 2024.

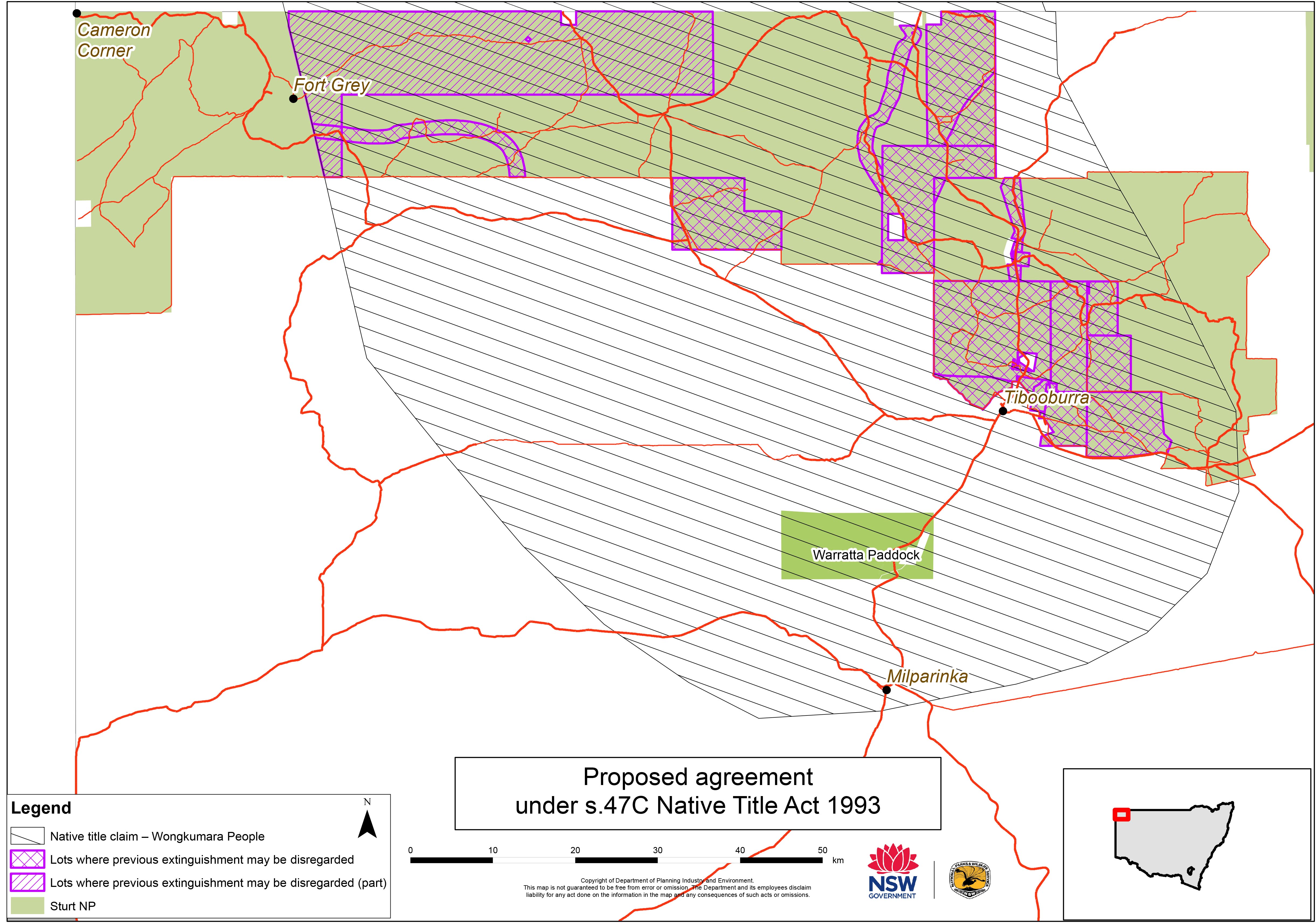

Wongkumara People – Native Title Act: Have Your Say

- Informal submission

- Mailout

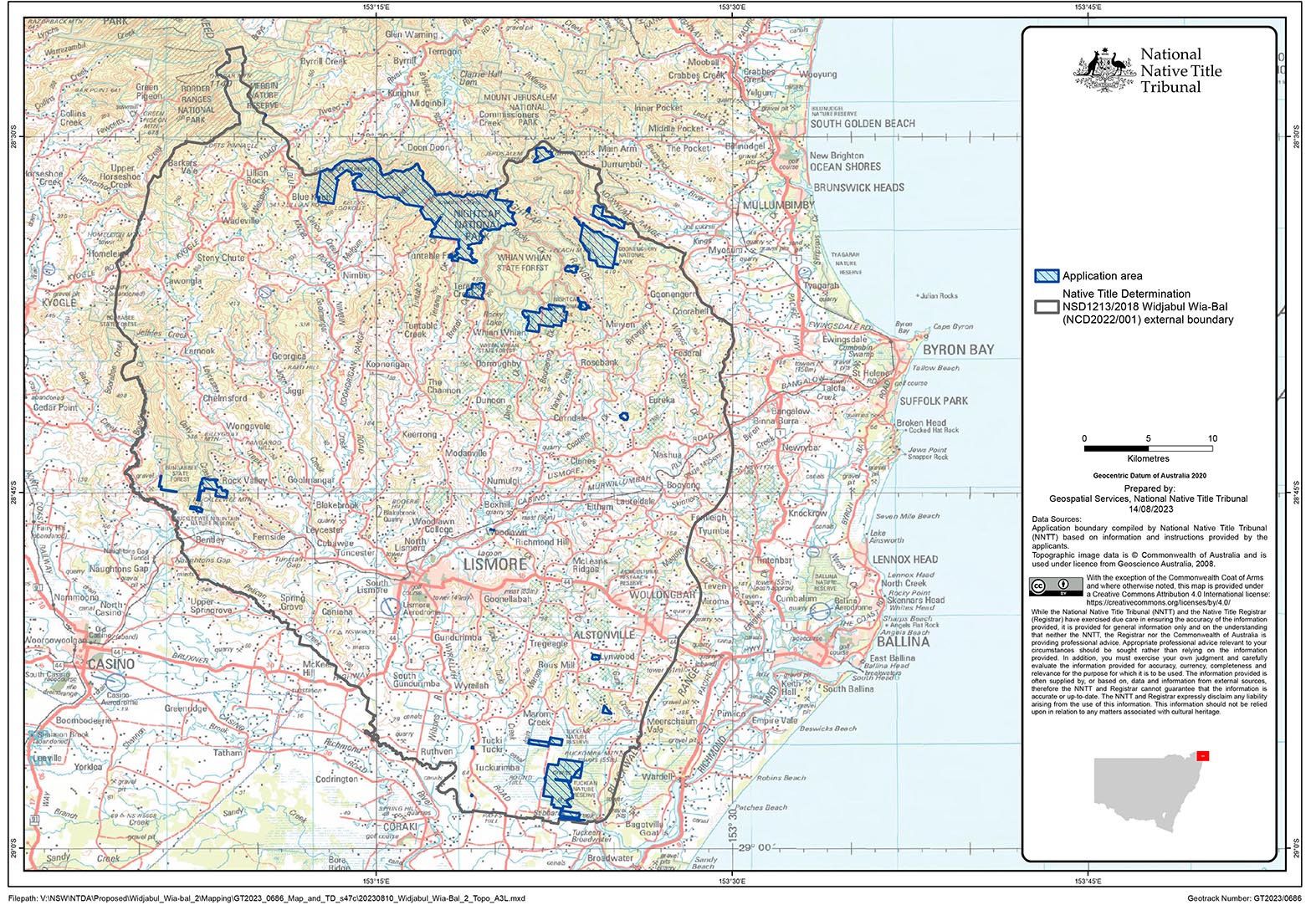

Widjabul Wia-Bal People – Notice Under The Native Title Act: Have Your Say

- Boatharbour Nature Reserve

- Tuckean Nature Reserve

- Muckleewee Mountain Nature Reserve

- Goonengerry National Park

- Victoria Park Nature Reserve

- Mount Jerusalem National Park

- Nightcap National Park

- Davis Scrub Nature Reserve

- Snows Gully Nature Reserve

- Tucki Tucki Nature Reserve

- Andrew Johnson Big Scrub Nature Reserve

- Whian Whian State Conservation Area.

Environmental Grants Connect To Country: Applications Close 2 April 2024

Independent Review Of Small-Scale Titles: Have Your Say

Crown Land Management Act 2016 Review: Have Your Say

.jpg?timestamp=1708537972385)

Coastal Floodplain Drainage Project: Have Your Say

- addressing the complexity, time and costs associated with the approvals process

- reducing the impact of these works and activities on downstream water quality, aquatic ecosystems, communities and industries.

- Option 1: One-stop shop webpage - A single source of information on the various approvals that may be required by government agencies for coastal floodplain drainage works.

- Option 2: Drainage applications coordinator - A central officer(s) to guide the applicant through the approvals processes for all NSW government agencies (Department of Planning and Environment’s Water Group, Planning, Crown Lands, and the Department of Primary Industries — Fisheries) and answer the applicant’s questions about their individual location and proposed works. The drainage applications coordinator would complement both Option 1 and Option 3.

- Option 3: Concurrent assessment - Concurrent assessment of applications by relevant government agencies.

- Option 4: Risk-based approach - NSW Government agencies would use a standardised risk matrix to compare the type and extent of the drainage works against the acidic water and blackwater potential of the drainage area to identify the level of risk associated with the proposed works. The identified level of risk could then be used to determine the level of information required from applicants, the level of assessment required by the approval authority, and the types of conditions applied to any approvals.

- Option 5: Drainage work approvals under the Water Management Act 2000 - Switch on drainage work approvals under the Water Management Act 2000. Two different methods of implementation are possible:

i. a drainage work approval would be required only when works are proposed and for the area of works onlyii. a drainage work approval could apply to existing and new drainage works across the entire drainage network.

Within either of these two methods, one of three different approaches for public authorities could be applied:

a. require public authorities to hold a drainage work approvalb. allow for public authorities to hold a conditional exemption from requiring approvalsc. exempt public authorities from requiring a drainage work approval.

- Option 6: Streamlining of Fisheries and Crown Land approvals through the use of drainage work approvals - Drainage work approvals, particularly under Option 5(ii), have the potential to deliver a catchment-wide consideration of the drainage network. This would provide greater certainty to other agencies such as Fisheries and Crown Land that environmental impacts have been considered and appropriate conditions applied, supporting them to assess and issue approvals more quickly.

- Tuesday 5 March 2024 - Register to attend

- Friday 8 March 2024 - Register to attend

Australia’s Eucalypt Of The Year Voting Opens Today In Your Backyard!

- Dwarf Apple Angophora hispida

- Ghost Gum Corymbia aparrerinja

- Red-flowering Gum Corymbia ficifolia

- Silver Princess Eucalyptus caesia

- Argyle Apple Eucalyptus cinerea

- Yellow Gum Eucalyptus leucoxylon

- Risdon Peppermint Eucalyptus risdonii

- Coral Gum Eucalyptus torquata

- Heart-leaved Mallee Eucalyptus websteriana

- Lemon-flowered Gum Eucalyptus woodwardii

Baiting foxes can make feral cats even more ‘brazen’, study of 1.5 million forest photos shows

Foxes and cats kill about 2.6 billion mammals, birds and reptiles across Australia, every year. To save native species from extinction, we need to protect them from these introduced predators. But land managers tend to focus on foxes, which are easier to control. Unfortunately this may have unintended consequences.

We wanted to find out how feral cats respond to fox control. In one of the biggest studies on this issue to date, we worked with land managers to set up 3,667 survey cameras in a series of controlled experiments. We studied the effects on cat behaviour and population density.

Our research shows feral cats are more abundant and more brazen after foxes are suppressed.

In some regions, cats need to be managed alongside foxes to protect native wildlife.

Could Feral Cats Benefit From Fox Control?

Foxes and cats were brought to Australia by European colonisers more than 170 years ago. They now coexist across much of the mainland.

While foxes are bigger than cats, they compete for many of the same prey species.

But most wildlife conservation programs in southern Australia only control foxes. That’s largely because controlling foxes is relatively straightforward. Foxes are scavengers and readily take poison baits. Feral cats, on the other hand, prefer live prey. So they’re much more difficult to control using baits.

Consequently, foxes have become the most widely controlled invasive predator in Australia, while feral cat control has been relatively localised.

Some native species have thrived following fox control or eradication, but others have continued to decline. For example, one study found numbers of common brushtail possums, Western quolls and Tammar wallabies increased following fox control in southwest Western Australia. However, seven other species crashed: dunnarts, woylies, southern brown bandicoots, western ringtail possums, bush rats, brush-tailed phascogales and western brush wallabies.

People suspected controlling foxes could inadvertently free feral cats from competition and aggression, particularly if there were no dingoes around.

Experimenting With Fox Control

To investigate how cats respond to fox control programs, we worked with land managers to run two large experiments in southwest Victoria. Foxes are the top predator in these forests and woodlands, because dingoes have already been removed.

We studied cat behaviour and population density before and after fox control in the Otway Ranges. In a separate study, we compared conservation reserves with and without fox control in the Glenelg region.

We put out 3,667 survey cameras over seven years. The cameras photograph animals as they walk by, allowing us to analyse where and when invasive predators and native mammals are active.

From these photographs, we were also able to identify individual feral cats based on their unique coat markings.

When multiple photographs of one cat were taken by several different cameras, we could track their movement. Combining information on the tracks of all the cats in an area allowed us to estimate cat population density.

It was a painstaking process. We went through almost 1.5 million images manually to check for animals, eliminate false triggers and identify individual cats.

Future research is exploring using artificial intelligence to streamline the process, but the computer still needs to be taught what to look for.

What We Found

We found sustained, intensive baiting for foxes worked. Areas with more poison baits had fewer foxes. Replacing baits regularly was also worthwhile.

Feral cat density was generally higher in areas with fox control. The strength of this effect varied with the extent and duration of fox management. We found up to 3.7 times as many cats in fox-baited landscapes.

Productive landscapes also supported more cats. There was about one feral cat per square kilometre in wet forests, compared with less than half as many in dry forests.

Feral cat behaviour also varied with fox control and forest type, including how visible cats were, how far they moved, and what times of day they were active.

Feral cats appeared more adventurous where fox populations were suppressed. In dry forests, for example, foxes were largely nocturnal, as were most native mammals. Feral cats became more active at night when there were fewer foxes, potentially giving them access to different prey species.

We found some threatened species, such as long-nosed potoroos, were doing much better in areas with long-term fox control, although others, such as southern brown bandicoots, showed no improvement.

We don’t know how fox control affected smaller native rodents and marsupials, which are likely to be most at risk from increased cat predation.

A Conservation Balancing Act

Broad-scale fox control is an important tool in the ongoing battle to protect Australia’s wildlife. Fox baiting is relatively simple and effective. But we have to balance the known benefits of fox control against potential unintended consequences.

Our study reinforces the need to carefully consider what could happen if you only control one pest animal, and to monitor carefully rather than assume that fox control will benefit all native species. We are not saying people should stop fox baiting, because there are clear benefits to species such as long-nosed potoroos. But we need to keep an eye on the cats and might need to also manage their impacts on native prey.

As feral cats are notoriously difficult to control lethally, indirect management may also be helpful. For example, promoting dense understorey vegetation for native prey to hide in or removing other sources of food that boost cat numbers such as pest rabbits.

Integrated pest management is challenging and expensive but likely needed, especially where feral cats or other pests are thriving alongside foxes.![]()

Matthew Rees, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, CSIRO and Bronwyn Hradsky, Research Fellow in Ecology, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Researchers found 37 mine sites in Australia that could be converted into renewable energy storage. So what are we waiting for?

The world is rapidly moving towards a renewable energy future. To support the transition, we must prepare back-up energy supplies for times when solar panels and wind turbines are not producing enough electricity.

One solution is to build more pumped hydro energy storage. But where should this expansion happen?

Our new research identified more than 900 suitable locations around the world: at former and existing mining sites. Some 37 sites are in Australia.

Huge open-cut mining pits would be turned into reservoirs to hold water for renewable energy storage. It would give the sites a new lease on life and help shore up the world’s low-emissions future.

The Benefits Of Pumped Hydro Storage

Pumped hydro energy storage has been demonstrated at scale for more than a century. Over the past few years, we have been identifying the best sites for “closed-loop” pumped hydro systems around the world.

Unlike conventional hydropower systems operating on rivers, closed-loop systems are located away from rivers. They require only two reservoirs, one higher than the other, between which water flows down a tunnel and through a turbine, producing electricity.

The water can be released – and power produced – to cover gaps in electricity supply when output from solar and wind is low (for example on cloudy or windless days). And when wind and solar are producing more electricity than is needed – such as on sunny or windy days – this cheap surplus power is used to pump the water back up the hill to the top reservoir, ready to be released again.

Off-river sites have very small environmental footprints and require very little water to operate. Pumped hydro energy storage is also generally cheaper than battery storage at large scales.

Batteries are the preferred method for energy storage over seconds to hours, while pumped hydro is preferred for overnight and longer storage.

Why Mining Sites?

There are big benefits to converting mining areas into pumped hydro plants.

For a start, the hole has already been dug, reducing construction costs. What’s more, mining sites are typically already serviced by roads and transmission infrastructure. The site usually has access to a water source for which the mine operators may have pumping rights. And the development takes place on land that is already cleared of vegetation, avoiding the need to disturb new areas.

Finally, community support may have already been obtained for the mining operations, which could easily be rolled over into a pumped hydro site.

In Australia, one pumped hydro energy storage project is already being built at a former gold mine site at Kidston in Far North Queensland.

The feasibility of two others is being assessed at Mount Rawdon near Bundaberg in Queensland, and at Muswellbrook in New South Wales. Both would repurpose old mining pits.

What We Found

Our previous research identified suitable locations in undeveloped areas (excluding protected land) and using existing reservoirs. Now, we have turned our attention to mine sites.

Our study used a computer algorithm to search the Earth’s surface for suitable sites. It looked for mining pits, pit lakes and tailings ponds in mining sites which were located near suitable land for a new upper reservoir. The idea is that the reservoir and mining site are “paired” and water pumped between them.

Globally, we identified 904 suitable mining sites across 77 countries.

Some 37 suitable sites are located in Australia. They include the Mount Rawdon and Muswellbrook mining pits already under investigation.

There are a number of potential options in Western Australia: in the iron-ore region of the Pilbara, south of Perth and around Kalgoorlie.

Options in Queensland and New South Wales are mostly located down the east coast, including the Coppabella Mine and the coal mining pits near the old Liddell Power Station. Possible sites also exist inland at Mount Isa in Queensland and at the Cadia Hill gold mine near Orange in NSW.

Potential sites in South Australia include the old Leigh Creek coal mine in the Flinders Ranges and the operating Prominent Hill mine northwest of Adelaide. Tasmania and Victoria also offer possible locations, although many other non-mining options exist in these states for pumped hydro storage.

We are not suggesting that operating mines be closed – rather, that pumped hydro storage be considered as part of site rehabilitation at the end of the mine’s life.

If old mining sites are to be converted into pumped hydro, several challenges must be addressed. For example, mine pits may contain contaminants that, if filled with water, could seep into groundwater. However, this could be overcome by lining reservoirs.

Looking Ahead

Australia has set a readily achievable goal of reaching 82% renewable electricity by 2030.

The Australian Energy Market Operator suggests by 2050, this nation needs about 640 gigawatt-hours of dispatchable or “on demand” storage to support solar and wind capacity. We currently have about 17 gigawatt-hours of electricity storage, with more committed by Snowy 2.0 and other projects.

The 37 possible pumped hydro sites we’ve identified could deliver 540 gigawatt-hours of storage potential. Combined with other non-mining sites we’ve identified previously, the options are far more numerous than our needs.

This means we can afford to be picky, and develop only the very best sites. So what are we waiting for?![]()

Timothy Weber, Research Officer for School of Engineering, Australian National University and Andrew Blakers, Professor of Engineering, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Our native animals are easy prey after a fire. Could artificial refuges save them?

Australia is home to some of the most spectacular and enigmatic wildlife on Earth. Much of it, however, is being eaten by two incredibly damaging invasive predators: the feral cat and the red fox.

Each year in Australia, cats and foxes kill an estimated 697 million reptiles, 510 million birds, and 1.4 billion mammals, totalling a staggering 2.6 billion animals. Since the predators were introduced more than 150 years ago, they have contributed to the extinction of more than 25 species – and are pushing many more to the brink.

Research suggests cats and foxes can be more active in areas recently burnt by fire. This is a real concern, especially as climate change increases the frequency and severity of fire in south-eastern Australia.

We urgently need new ways to protect wildlife after fires. Our study trialled one such tool: building artificial refuges across burnt landscapes. The results are promising, but researchers need to find out more.

Triple Threat: Cats, Foxes And Fire

Many native animals are well-adapted to fire. But the changing frequency and intensity of fire is posing a considerable threat to much of Australia’s wildlife.

Fire removes vegetation such as grass, leaf litter and shrubs. This leaves fewer places for native animals to shelter and hide, making it easier for cats and foxes to catch them.

We conducted our experiment in three Australian ecosystems: the forests of the Otway Ranges (Victoria), the sand dunes of the Simpson Desert (Queensland) and the woodlands of Kangaroo Island (South Australia). Each had recently been burnt by fire.

We built 76 refuges across these study areas. They were 90cm wide and up to 50m long – and backbreaking to install! They were made from wire mesh, mostly covered by shade cloth. Spacing in the mesh of 50mm allowed small animals to enter and exit from any point, while completely excluding cats, foxes and other larger animals. The shade cloth obstructed the vision of predators.

We then placed remote-sensing camera traps both inside and away from each refuge, and monitored them for periods ranging from four months to four years.

The placement of the cameras meant we could compare the effect of the refuges with what occurred outside them.

What We Found

Across the three study areas, the artificial refuges were used by 56 species or species groups. This included the critically endangered Kangaroo Island dunnart, the threatened white-footed dunnart and the threatened southern emu-wren.

For around half the species, we detected more individuals inside the refuges than outside. As we predicted, the activity of small birds and reptiles, in particular, was much higher inside the refuges.

But surprisingly, reptile activity was also generally higher inside the refuges, particularly among skinks. We had not predicted that, because the shade cloth likely made conditions inside the refuges cooler than outside, and reptiles require warmth to regulate their body temperature.

Over time, the number of animals detected inside the refuges generally increased. This was also a surprise. We expected detections inside the refuges to decline through time as the vegetation recovered and the risk of being seen by predators fell.

But there were also a few complicating factors. For example, in the Otway Ranges and Simpson Desert, similar numbers of the mammals were detected inside and away from the refuges. This suggests the species didn’t consider the refuges as particularly safe places, which means the structures may not reduce the risk of these animals becoming prey.

So what’s the upshot of all this? Our findings suggest that establishing artificial refuges after fire may help some small vertebrates, especially small birds and skinks, avoid predators across a range of ecosystems. However, more research is required before this strategy is adopted as a widespread management tool.

Important Next Steps

Almost all evidence for an increase in cat and fox activity after fire comes from Australia, particularly the tropical north. But cats are an invasive species in more than 120 countries and islands.

That means there’s real potential for post-fire damage to wildlife to worsen globally, especially as fire risk increases with climate change.

Our results suggest artificial refuges may be a way to help animals survive after fire. But there are still important questions to answer, such as:

- can artificial refuges improve the overall abundance and survival of individuals and species?

- if so, how many refuges would be required to achieve this?

- in the presence of natural refuges – such as rocks, logs, burrows, and unburnt patches – are artificial refuges needed?

- does their effectiveness vary between low-severity planned burns and high-severity bushfires?

These questions must be answered. Conservation budgets are tight. After fires, funds must be directed towards actions that we know will work. That evidence is not yet there for artificial refuges.

Our team is busy trying to find out more. We urge other ecologists and conservationists to do so as well. We also encourage collaboration with designers and technologists to improve on our refuge design. For example, can such large refuges be made biodegradable and easier to deploy?

Solving these problems is important. It’s almost impossible to rid the entire Australian continent of cats and foxes. So land managers need all the help they can get to stop these predators from decimating Australia’s incredible wildlife. ![]()

Darcy Watchorn, PhD Candidate, Deakin University; Chris Dickman, Professor Emeritus in Terrestrial Ecology, University of Sydney, and Don Driscoll, Professor in Terrestrial Ecology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Victoria’s fire alert has knocked Australians out of complacency. Under climate change, catastrophic bushfires can strike any time

David Bowman, University of TasmaniaVictorians were braced for the worst on Wednesday amid soaring temperatures and gusty winds, creating the state’s worst fire conditions in years. Authorities have declared a “catastrophic” fire risk in some parts of the state.

At the time of writing, the Bayindeen bushfire near Ballarat was still burning out of control, almost a week after it began. It had razed 21,300 hectares, destroyed six homes and killed livestock. And more than 30,000 people in high-risk areas between Ballarat and Ararat had reportedly been told to leave their homes.

This statewide emergency is noteworthy for several reasons. First, it represent a big test of Australia’s updated fire danger rating system. The new version adopted in 2022 dictates that if a fire takes hold under catastrophic conditions, people should leave an area rather than shelter in place or stay defend their homes.

The second point to note is the timing: late February, when many Australians probably thought the worst of the bushfire season was over. Climate change is bringing not just more frequent and severe fires, but longer fire seasons. That means we must stay on heightened alert for much longer than in the past.

Under Catastrophic Conditions, Leave

The current Australian Fire Danger Rating System was implemented in September 2022. It’s a nationally consistent system based on the latest scientific research.

Authorities hope the system will more accurately predict fire danger. It was also designed to more clearly communicate the danger rating to the public. For example, it involves just four danger ratings, compared to the previous six under the old Victorian regime.

“Catastrophic” fire danger – previously “code red” in Victoria – represents the worst conditions. The main message for the public under these conditions is:

If a fire starts and takes hold, lives are likely to be lost. For your survival leave bushfire risk areas.

Under catastrophic conditions, people are advised to move to a safer location early in the morning or even the day before. Authorities warn “homes cannot withstand fires in these conditions. You may not be able to leave, and help may not be available”.

Lessons From Black Saturday

Australia’s previous fire danger rating system was developed in the 1960s and was formally known as the McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index. It initially comprised five risk levels ranging from low-moderate to extreme. However, states were free to adapt the system to their needs, including adding extra categories.

The devastating 2009 Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria killed 173 people. Many people died after staying to defend their properties.

The tragedy prompted scrutiny of the fire danger ratings system in Victoria, and the “code red” category was added. The message under those conditions was that those living in a bushfire-prone area should leave. The first code red was declared in 2010, then another in 2019.

That system was replaced by the national system in 2022.

Don’t Stay And Defend

Under the current fire danger rating system, catastrophic conditions mean everyone should leave an area. The leave orders currently issued in Victoria cover many thousands of people, and represent a big test of this advice.

We don’t yet know how many people will heed the advice of authorities. However, at least some people have reportedly decided to stay and defend their properties.

If thousands of others do flee, what will result? Will rural roads be blocked? Do we have the infrastructure to temporarily house all those evacuees? Whether or not the fire situation escalates on Wednesday, there will be much to learn about how we deal with such threats.

Certainly, it’s prudent for people in high-risk areas to leave. In hot, windy conditions, a fire could erupt and take hold in minutes. The collapse of electricity transmission towers in Victoria last week showed the vulnerability of such infrastructure in high winds. It doesn’t take long for downed power lines to ignite the surrounding bush.

Is there a potential alternative to the mass relocation of people in response to a major fire risk? Yes: building communities that are sufficiently fire-proofed to withstand catastrophic fire weather.

This could be achieved through adaptation measures such as building fire bunkers and specially-designed houses. It would also involve carefully managed bushland and creating fire breaks by planting non-flammable plants. It may also include targeted cultural burning by Traditional Owners. These options require further discussion and research.

Our Fire Seasons Are Getting Longer

The current emergency in Victoria shows how Australia’s fire seasons are changing.

It’s late February and summer is almost over. The kids are back at school and the adults are back at work. It seemed southeast Australia had escaped the bad fire summer that many had feared. Few people expected this late-season emergency.

But as climate change escalates, we must expect the unexpected. In a fire-prone continent such as Australia, we can never relax in a warming world. We must be in a constant, heightened state of preparedness.

That means know your risk and prepare your home. Draw up a bushfire survival plan – think about details such as what to do with pets and who will check on vulnerable neighbours. And please, heed the advice of authorities.![]()

David Bowman, Professor of Pyrogeography and Fire Science, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What we know about last year’s top 10 wild Australian climatic events – from fire and flood combos to cyclone-driven extreme rain

Fire. Flood. Fire and flood together. Double-whammy storms. Unprecedented rainfall. Heatwaves. Climate change is making some of Australia’s weather more extreme. In 2023, the country was hit by a broad range of particularly intense events, with economy-wide impacts. Winter was the warmest in a record going back to 1910, while we had the driest September since at least 1900.

We often see extreme weather as distinct events in the news. But it can be useful to look at what’s happening over the year.

Today, more than 30 of Australia’s leading climate scientists released a report analysing ten major weather events in 2023, from early fires to low snowpack to compound events.

Can we say how much climate change contributed to these events? Not yet. It normally takes several years of research before we can clearly say what role climate change played. But the longer term trends are well established – more frequent, more intense heatwaves over most of Australia, marine heatwave days more than doubling over the last century, and short, intense rainfall events intensifying in some areas.

What Happened In 2023?

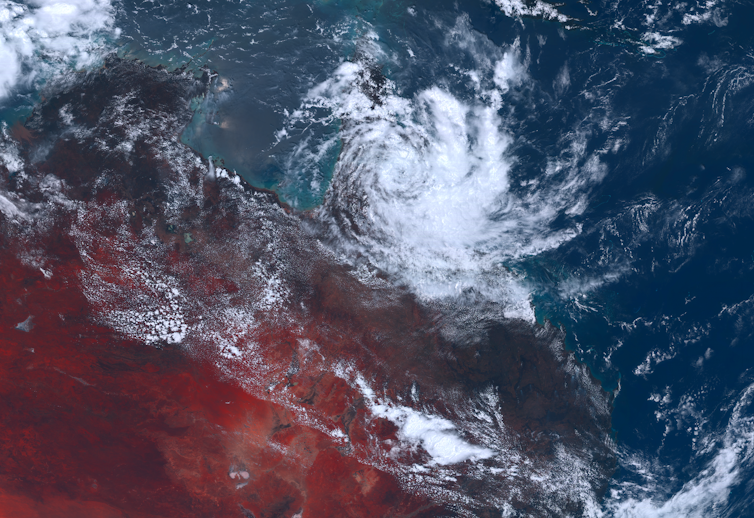

January. Event #1: Record-breaking rain in the north (NT, WA, QLD)

The year began with above-average rainfall in northern Australia influenced by the “triple-dip” La Niña phase.

Some parts of the country were already experiencing heavy rainfall even before Cyclone Ellie arrived. From late December 2022 to early January 2023, Ellie brought heavy rainfall to Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland, resulting in a one-in-100-year flooding of the Fitzroy River. Interestingly, Cyclone Ellie was only a “weak” Category 1 tropical cyclone. So why did it cause so much damage? In their analysis, climate scientists suggest it was actually low wind speeds in the mid-troposphere which allowed the system to stall and keep raining.

February–March. Event 2: Extreme rain and food shortages (NT, QLD)

Climate scientists observed the same behaviour from late February to early March 2023, when a persistent slow-moving low-pressure system known as a monsoonal low dumped heavy, widespread rain over the Northern Territory and north-west Queensland. The resulting floods cut transport routes in the NT, and led to food shortages.

June–August. Event 3 and 4: Warmest winter, little snow (NSW)

After a wet start to the year, conditions became drier and warmer in southern and eastern Australia. New South Wales experienced its warmest winter on record, with daily maximums more than 2°C above the long-term average.

The unusual heat and lack of precipitation translated into the second-worst snow season on record (the worst was 2006).

September. Event 5: Record heatwave (SA)

In September, South Australia faced a record-breaking heatwave. Temperatures reached as high as 38°C in Ceduna. As warming continues, scientists suggest unusual heat and heatwaves during the cool season will become more frequent and intense.

September also saw El Niño and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole declared by the Bureau of Meteorology. When these two climate drivers combine, we have a higher chance of a warm and dry Australia, particularly during late winter and spring.

October. Event 6, 7 and 8: Fire-and-flood compound event (VIC), compound wind and rain storms (TAS), unusually early fires (QLD)

Dry conditions gave rise to an unseasonably early fire season in Victoria and Queensland. In October, Queensland’s Western Downs region was hit hard. Dozens of houses and two lives were lost in the town of Tara.

The same month, Victoria’s Gippsland region was hit by back-to-back fires and floods, a phenomenon known as a compound event.

While it’s difficult to attribute these events to climate change, scientists say hot and dry winters make Australia more prone to early season fires.

Also in October, a different compound event struck Tasmania in the form of successive low-pressure systems. The first dumped a month’s worth of rain in a few days over much of the state, while the second brought strong winds. The rain from the first storm loosened the soil, making it easier for trees to be blown down.

Scientists say the combined effects were more severe than if just one of these events occurred without the other. Such extreme wind-and-rain compound events are expected to occur more frequently in regions such as the tropics as the climate continues to change.

November. Event 9: Supercell thunderstorm trashed crops (QLD)

In November, a supercell thunderstorm hit Queensland’s south-east, destroying A$50 million worth of crops and farming equipment. Initial research suggests extreme winds and thunderstorms may become more likely under climate change, but more work is needed.

December. Event 10: Unprecedented flooding from Cyclone Jasper (QLD)

In mid-December, Tropical Cyclone Jasper made landfall as a Category 2 tropical cyclone in north Queensland. The system weakened into a tropical low and then stalled over Cape York. The weather system’s northerly winds drew in moist air from the Coral Sea, which collided with drier winds from the south-east. This caused persistent heavy rainfall over the region – up to 2 metres in places. Catchments flooded across the region, causing widespread damage to roads, buildings and crops. Similar to ex-Tropical Cyclone Ellie, most damage occurred after landfall as the system stalled and dumped rain.

Climate Change Can Make Extreme Weather Even More Extreme

It’s generally easier to identify and understand the role of human-caused climate change in large-scale extreme events, particularly temperature extremes. So we can say 2023’s exceptional winter heat was probably intensified by what we have done to the climate system.

For smaller-scale extremes, it is often harder to determine the role of climate change, but there’s some evidence short, intense rainfall events are getting even more intense as the world warms. Early-season bushfires and low snow cover are consistent with what we expect under global warming.

There’s also an increasing threat from the risk of compound events where concurrent or consecutive extreme events can amplify damage.

Australia’s intense weather events during 2023 are broadly what we can expect to see as the world keeps getting hotter and hotter due to the heat-trapping greenhouse gases humanity continues to emit. ![]()

Laure Poncet, Research officer, UNSW Sydney and Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

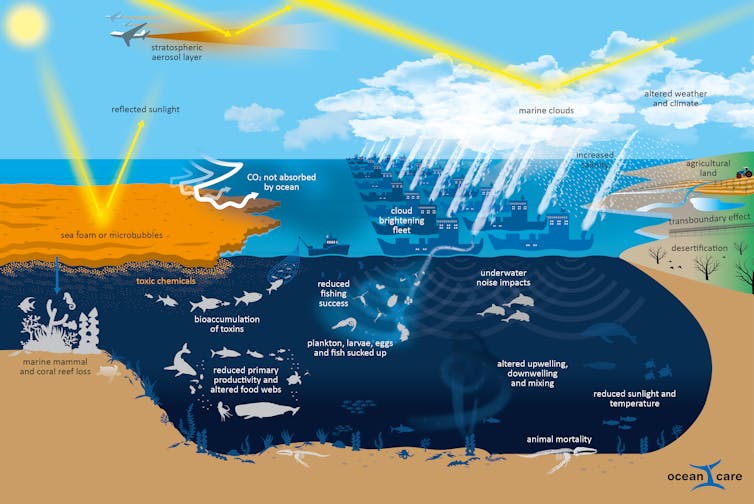

Not such a bright idea: cooling the Earth by reflecting sunlight back to space is a dangerous distraction

The United Nations Environment Assembly this week considered a resolution on solar radiation modification, which refers to controversial technologies intended to mask the heating effect of greenhouse gases by reflecting some sunlight back to space.

Proponents argue the technologies will limit the effects of climate change. In reality, this type of “geoengineering” risks further destabilising an already deeply disturbed climate system. What’s more, its full impacts cannot be known until after deployment.

The draft resolution initially called for the convening of an expert group to examine the benefits and risks of solar radiation modification. The motion was withdrawn on Thursday after no consensus could be reached on the controversial topic.

A notable development was a call from some Global South countries for a “non-use agreement” on solar radiation modification. We strongly support this position. Human-caused climate change is already one planetary-scale experiment too many – we don’t need another.

A Risky Business

In some circles, solar geoengineering is gaining prominence as a response to the climate crisis. However, research has consistently identified potential risks posed by the technologies such as:

unpredictable effects on climate and weather patterns

biodiversity loss, especially if use of the technology was halted abruptly

undermining food security by, for example, reducing light and increasing salinity on land

the infringement of human rights across generations – including, but not limited to, passing on huge risks to generations that will come after us.

Here, we discuss several examples of solar radiation modification which exemplify the threats posed by these technologies. These are also depicted in the graphic below.

A Load Of Hot Air

In April 2022, an American startup company released two weather balloons into the air from Mexico. The experiment was conducted without approval from Mexican authorities.

The intent was to cool the atmosphere by deflecting sunlight. The resulting reduction in warming would be sold for profit as “cooling credits” to those wanting to offset greenhouse gas pollution.

Appreciably cooling the climate would, in reality, require injecting millions of metric tons of aerosols into the stratosphere, using a purpose-built fleet of high-altitude aircraft. Such an undertaking would alter global wind and rainfall patterns, leading to more drought and cyclones, exacerbating acid rainfall and slowing ozone recovery.

Once started, this stratospheric aerosol injection would need to be carried out continually for at least a century to achieve the desired cooling effect. Stopping prematurely would lead to an unprecedented rise in global temperatures far outpacing extreme climate change scenarios.

Heads In The Clouds

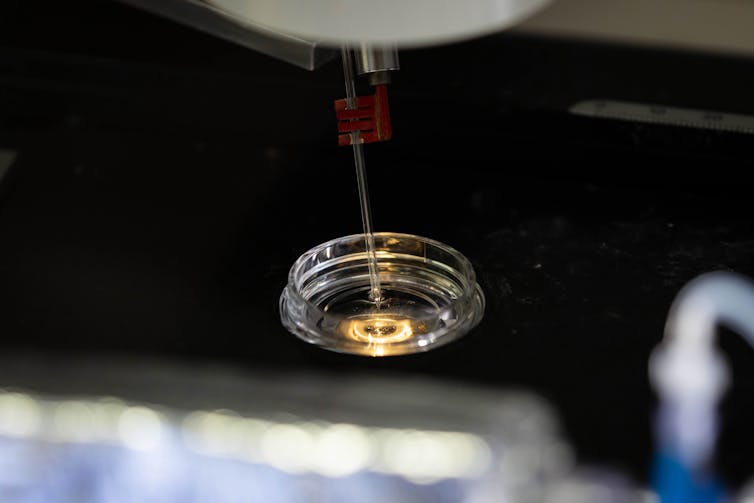

Another solar geoengineering technology, known as marine cloud brightening, seeks to make low-lying clouds more reflective by spraying microscopic seawater droplets into the air. Since 2017, trials have been underway on the Great Barrier Reef.

The project is tiny in scale, and involves pumping seawater onto a boat and spraying it from nozzles towards the sky. The project leader says the mist-generating machine would need to be scaled up by a factor of ten, to about 3,000 nozzles, to brighten nearby clouds by 30%.

After years of trials, the project has not yet produced peer-reviewed empirical evidence that cloud brightening could reduce sea surface temperatures or protect corals from bleaching.

The Great Barrier Reef is the size of Italy. Scaling up attempts at cloud brightening would require up to 1,000 machines on boats, all pumping and spraying vast amounts of seawater for months during summer. Even if it worked, the operation is hardly, as its proponents claim, “environmentally benign”.

The technology’s effects remain unclear. For the Great Barrier Reef, less sunlight and lower temperatures could alter water movement and mixing, harming marine life. Marine life may also be killed by pumps or negatively affected by the additional noise pollution. And on land, marine cloud brightening may lead to altered rainfall patterns and increased salinity, damaging agriculture.

More broadly, 101 governments last year agreed to a statement describing marine-based geoengineering, including cloud brightening, as having “the potential for deleterious effects that are widespread, long-lasting or severe”.

Balls, Bubbles And Foams

The Arctic Ice Project involves spreading a layer of tiny glass spheres over large regions of sea ice to brighten its surface and halt ice loss.

Trials have been conducted on frozen lakes in North America. Scientists recently showed the spheres actually absorb some sunlight, speeding up sea-ice loss in some conditions.

Another proposed intervention is spraying the ocean with microbubbles or sea foam to make the surface more reflective. This would introduce large concentrations of chemicals to stabilise bubbles or foam at the sea surface, posing significant risk to marine life, ecosystem function and fisheries.

No More Distractions

Some scientists investigating solar geoengineering discuss the need for “exit ramps” – the termination of research once a proposed intervention is deemed to be technically infeasible, too risky or socially unacceptable. We believe this point has already been reached.

Since 2022, more than 500 scientists from 61 countries have signed an open letter calling for an international non-use agreement on solar geoengineering. Aside from the types of risks discussed above, the letter said the speculative technologies detract from the urgent need to cut global emissions, and that no global governance system exists to fairly and effectively regulate their deployment.

Calls for outdoor experimentation of the technologies are misguided and detract energy and resources from what we need to do today: phase out fossil fuels and accelerate a just transition worldwide.

Climate change is the greatest challenge facing humanity, and global responses have been woefully inadequate. Humanity must not pursue dangerous distractions that do nothing to tackle the root causes of climate change, come with incalculable risk, and will likely further delay climate action.![]()

James Kerry, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, James Cook University, Australia and Senior Marine and Climate Scientist, OceanCare, Switzerland, James Cook University; Aarti Gupta, Professor of Global Environmental Governance, Wageningen University, and Terry Hughes, Distinguished Professor, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

As Varroa spreads, now is the time to fight for Australia’s honey bees – and you can help

A tiny foe threatens Australian beekeepers’ livelihood, our food supply and the national economy. First detected in New South Wales in 2022, the Varroa mite is now established in Australia.

The parasitic mite, which feeds on honey bees and transmits bee viruses, has since spread across New South Wales.

It is expected to kill virtually all unmanaged honey bees living in the bush (also known as “feral” honey bees), which provide ecosystem-wide pollination. Honey bees managed by beekeepers will survive only with constant and costly use of pesticides.

As the last holdout against Varroa, Australia has a key advantage – we can still take action that was impossible elsewhere. We know Varroa-resistant bees would be the silver bullet. Despite decades of research, no fully resistant strains exist, largely because the genetics of Varroa resistance are complex and remain poorly understood.

A recently released national management plan places a heavy focus on beekeeper education, aiming to transition the industry to self-management in two years. This leaves research gaps that need to be urgently filled – and we can all work together to help tackle these.

Unlocking The Genetic Key To Resistance

Without human intervention, Varroa kills around 95% of the honey bees it infects, but the survivors can evolve resistance. However, losing almost all bees would decimate Australia’s agriculture.

Our feral honey bees will have no choice but to evolve resistance, as they have in other countries. However, feral honey bees are not suited for beekeeping as they are too aggressive, don’t stay with the hive and don’t produce enough honey.

In principle, we could breed for a combination of feral resistance and domestic docility. But figuring out the genetics of how feral bees resist Varroa has been a challenge. As most bees exposed to the parasite will die, the survivors will be genetically different.

Some of these differences will be due to natural selection, but most will be due to chance. Identifying the genes responsible for resistance in this scenario is difficult. The best way to find them is to measure genetic changes before and after Varroa infestation. But to do that, we need bee populations largely unaffected by Varroa.

This is where our unique Australian opportunity comes in. We have a small and vanishing window to collect bees before the inevitable rapid spread of the mites, and the mass die-offs, occur.

We Are Collecting Information… And Bees

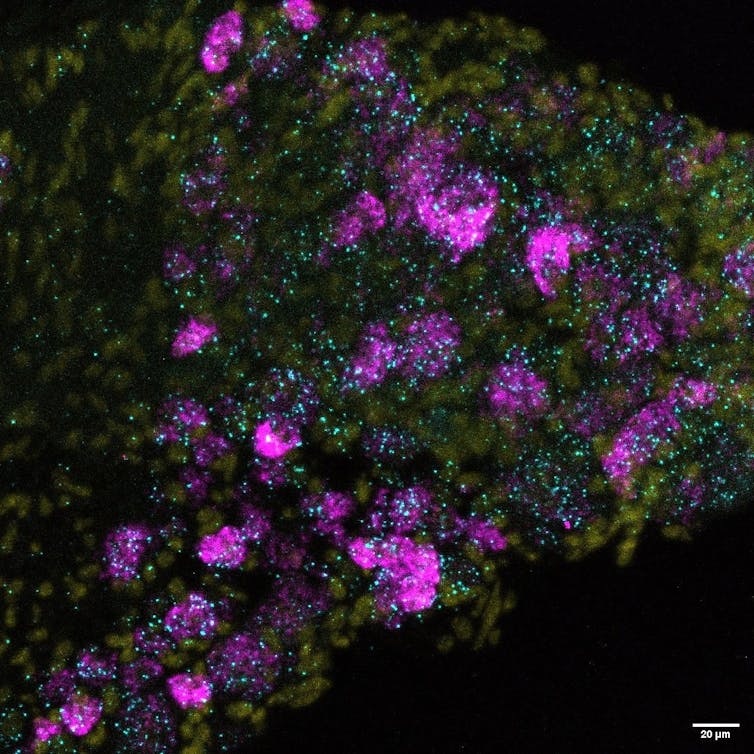

My lab at the Australian National University’s Research School of Biology has started collecting data on feral bee populations around New South Wales to identify pre-Varroa genetic diversity.

We will also monitor changes in bee population size and the spread of viruses and mites.

The most efficient way to collect bees is to go to a local clearing, such as a sports oval surrounded by forest. Unbeknownst to the cricket players, honey bee males (that is, drones) congregate at these sites by the thousands on sunny afternoons looking for mates.

You can lure them with some queen pheromone suspended from a balloon, and sweep them up with a butterfly net. Bee drones have no stinger and only come out for a couple of hours when the weather is fantastic, making collecting them literally a walk in the park, suitable for nature enthusiasts of all ages.

Anyone Can Help

You can help this effort by collecting some drones in your local area – this would save us time and carbon emissions from driving all over the country. We will provide pheromone lures, instructions, and materials for sending the bees back via mail. By sacrificing a few drones for the research now, we might save millions of bees in the future.

If you can spare just a couple of summer afternoons, this would give two timepoints at your location, and we can monitor any changes as the Varroa infestation progresses. More information can be found on our website.

Apart from our project, there are also other urgent research questions. For example, how will native forests respond to the loss of their dominant pollinators? Will honey bee viruses spread into other insects?

Work on these and other projects also requires pre-Varroa data. Unfortunately, Varroa falls through our research infrastructure net. Most of Australia’s agricultural funding is industry-led, however, the beekeeping industry is small and lacks the resources to tackle Varroa research while also reeling from its impacts.

Other industries that rely on honey bees for pollination, including most fruit, nut and berry growers, have diverse research needs and are one step removed from the actual problem.

Together, we can take action to save Australia’s honey bees and assure security for our key pollinators.![]()

Alexander Mikheyev, Professor, ANU Bee lab, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Secrets in the canopy: scientists discover 8 striking new bee species in the Pacific

After a decade searching for new species of bees in forests of the Pacific Islands, all we had to do was look up.

We soon found eight new species of masked bees in the forest canopy: six in Fiji, one in French Polynesia and another in Micronesia. Now we expect to find many more.

Forest-dwelling bees evolved for thousands of years alongside native plants, and play unique and important roles in nature. Studying these species can help us better understand bee evolution, diversity and conservation.

Almost 21,000 bee species are known to science. Many more remain undiscovered. But it’s a race against time, as the twin challenges of habitat loss and climate change threaten bee survival. We need to identify and protect bee species before they disappear forever.

Introducing The New Masked Bees

Pollinators abound in forests. But scientific research has tended to focus on bees living closer to the ground.

We believe this sampling bias is replicated across much of the world. For example, another related Oceanic masked bee, Pharohylaeus lactiferus (a cloaked bee), was recently found in the canopy after 100 years in hiding.

Our first decade of bee sampling in Fiji turned up only one bee from the genus Hylaeus. This bee probably belonged in the canopy so we were very lucky to catch it near the ground. Targeted attempts over the next few years, using our standard short insect nets, failed to find any more.

But this changed when we turned our attention to searching the forest canopy.

Sampling in the canopy is physically challenging. Strength and skill are required to sweep a long, heavy net and pole through the treetops. It’s quite a workout. We limit our efforts to the edges of forests, where branches won’t tangle the whole contraption.

By lifting our gaze in this way, we discovered eight new bee species, all in the genus Hylaeus. They are mostly black with stunning yellow or white highlights, especially on their faces – hence the name, masked bees.

They appear to rely exclusively on the forest canopy. This behaviour is striking and has rarely been identified in bees before (perhaps because few scientists have been looking for bees up there).

Because the new species live in forests and native tree tops, they’re likely to be vulnerable to land clearing, cyclones and climate change.

More work is needed to uncover the secrets hidden in these dense tropical treetops. It may require engineering solutions such as canopy cranes and drones, as well as skilful tree-climbing using ropes, pulleys and harnesses.

Michener’s Missing Links

The journey of bees across the Pacific region is a tale of great dispersals and isolation.

Almost 60 years ago, world-renowned bee expert Charles Michener described what was probably the most isolated masked bee around, Hylaeus tuamotuensis.

The specimen was found in French Polynesia. At the time, Michener said that was “entirely unexpected”, because the nearest relatives were, as the bee flies, 4,000km north in Hawaii, 5,000km southwest in New Zealand, and 6,000km west in Australia.

So how did it get there and where did it come from?

Our research helps to answer these questions. We found eight new Hylaeus species including one from French Polynesia. Using genetic analysis and other methods, we found strong links between these species and H. tuamotuensis.

So Michener’s bee was probably an ancient immigrant from Fiji, 3,000km away. A journey of that magnitude is no mean feat for bees smaller than a grain of rice.

Of course, there are more than 1,700 islands in the Pacific, which can serve as stepping stones for bees on their long journeys.

We don’t yet know how many new Hylaeus species might exist in the South Pacific, or the routes they took to get to their island homes. But we suspect there are many more to be found.

Our Pacific Emissaries

The early origins of Fijian bees – both ground-dwelling Homalictus and forest-loving Hylaeus – can be traced to the ancient past when Australia and New Guinea were part of one land mass, known as Sahul. The ancestors of both groups then undertook epic oceanic journeys to travel from Sahul to the furthest reaches of the Pacific, where they diversified. But the Hylaeus travelled furthest, by thousands of kilometres.

These little emissaries have similarly brought together researchers across the region. We resolved difficulties sampling and gathering knowledge by working with people across the Pacific, including Fiji, French Polynesia, and Hawaii. It shows what can be accomplished with international collaboration.

Together we are making great strides towards understanding our shared bee biodiversity. Such collaborations are our best chance of discovering and conserving species while we can.

We would like to thank Ben Parslow and Karl Magnacca for their contribution to this article. We would further like to thank our collaborators and their home institutions, the Hawiian Department of Land and Natural Resources, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, University of the South Pacific, the South Australian Museum and Adelaide University.![]()

James B. Dorey, Lecturer in Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong; Amy-Marie Gilpin, Lecturer in Invertebrate Ecology, Western Sydney University, and Olivia Davies, , Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

From crickets in Melbourne to grasshoppers in Cairns, here’s what triggers an insect outbreak

In recent weeks, Melburnians have reported thousands of crickets showing up in large numbers after dark, flying into homes and shops and taking up residence.

The insect in question is the widespread, native black field cricket (Teleogryllus commodus).

Some media reports have described the swarms as a “plague”. This is not quite accurate, because scientists in Australia reserve that term for serious pests such as mice and some locusts. It’s best to call the present phenomenon an “outbreak”.

So what triggers these outbreaks, and how can we best live alongside insects as they go through these cycles of boom and bust?

Why The Crickets Moved To Melbourne

Black field crickets are not usually pests – the insects belong here and their song is that of the Australian bush. Crickets are a valuable food source for birds, reptiles and mammals.

Males sing every night by rubbing their wings together. They can easily be distinguished from females by the absence of the needle-like organ called an ovipositor that the females use for laying eggs.

Black field crickets are notorious for breeding in large numbers then flying to new sites at night.

Recent unseasonal and persistent rain fostered the growth of plants and insects, supplying ample food for the crickets. This is the most likely trigger for the extraordinarily large numbers we’re seeing.

The crickets may have flown in on persistent winds, or maybe the city lights attracted them. Nocturnal insects use light to work out which way is up, so they find artificial light confusing.

Cooler weather will help keep crickets in their natural habitat, where they belong. The hot weather would have stimulated their movement and spurred them on, because crickets are more active when it’s warm.

Tips For Dealing With The Crickets

Crickets are naturally attracted to light sources during the night. This can lead them to enter indoor spaces – often through small openings such as cracks around doors, or through windows or vents.

Keeping crickets out of your home can be challenging. Start by turning off outdoor lights and closing curtains and blinds. Seal entry points and install insect screens.

Changing outdoor lights from bright white to yellow will also help to deter insects.

If crickets do enter your home, they can easily be caught in a jar and taken outside.

A lack of humidity means crickets don’t survive indoors for more than a few days. Females require soil to lay their eggs, which means they won’t breed inside the home.

As an aside, if you fancy a cricket as a pet, they can be kept alive for a few weeks in a takeaway plastic container with some air holes. Captive crickets should be provided with a source of water such as a wet cotton ball in a jar lid. They can be fed muesli and a bit of apple, which provides another source of moisture. The water and the moist food raises the humidity to a suitable level.

Other Insects Swarm, Too

Rain often triggers insect outbreaks.

In Far North Queensland, where I live, we had almost 2 metres of rain in less than a week during Cyclone Jasper. And the rain persists. This has caused some insects that normally occur in small numbers to reproduce abnormally.

Cairns is a favoured destination for multiple grasshopper species that thrive in warm, wet conditions. They have been known to trouble Cairns Airport, but authorities there now have a good Wildlife Hazard Management Plan in place.

In Canberra, huge numbers of bogong moths have been known to infiltrate Parliament House for few weeks en route to the Australian Alps, where they spend the summer. The moths reproduce during wet years and the following season, they migrate in great numbers.

The widespread little Upolu meadow katydid (Conocephalus upoluensis) also breeds in large numbers after good rain. Adults fly to lights, often in their hundreds, and can be seen at outback petrol stations and cafes. As with most of these outbreaks, their presence is shortlived.

Looking Ahead

Under climate change, plagues of some insects such as locusts are expected to worsen as a result of increased heat and extreme rains.

However, climate change is also expected to lead to declines in some insect species. This compounds other harms caused by humans such as habitat loss and pollution.

Those pressures mean insect populations may be moving into new, populated areas in search of more favourable conditions.

All that said, we can expect insect outbreaks to happen again. My advice for those in Melbourne is just to wait until the crickets move on – and in the meantime, enjoy the spectacle of nature.![]()

David Rentz, Adjunct Professorial Research Fellow, School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

On fisheries, Australia must be prepared for New Zealand as opponent rather than ally

On February 1, senior Australian and New Zealand ministers signed a Joint Statement of Cooperation, acknowledging the long history of collaboration between the two nations.

The same week, New Zealand rejected an Australian proposal on sustainable fishing at the annual fisheries meeting of nations that fish in the high seas of the South Pacific. The move has driven a wedge between these traditional allies.

At stake was an agreement by those nations to protect 70% of special and vulnerable marine ecosystems, such as ancient corals, from destructive fishing practices like bottom-trawling.

Until December 2023, NZ was jointly leading the work to implement this agreement with Australia. But New Zealand’s new government, a coalition of conservative parties, rejected the proposed restrictions, citing concerns about jobs and development.

This sudden about-face raises many questions for Australia, and for progress on sustainable fishing more generally. On fishing, Australia must now be prepared to consider New Zealand an opponent rather than ally.

Sustainable Fishing Alliance No More?

In 2009, Australia, New Zealand and Chile led successful negotiations for a convention governing sustainable fishing in the South Pacific high seas beyond a nation’s marine exclusive economic zones, meaning more than 370km off the coast. The goal was to make sure fish stocks were not fished out and to protect marine ecosystems. (Tuna are not included, as they are dealt with under a separate convention.)

Since then, New Zealand and Australia have led much of the development of regulations governing the sustainable use of deepwater fish species and the conservation of vulnerable marine ecosystems in the South Pacific region. Their work led to the first measures governing deepwater fisheries, science-based catch limits for deepwater species, and a joint assessment of seafloor fishing methods such as trawling.

But the idea of banning or restricting trawling was controversial. Bottom-trawling, in which boats deploy giant nets that scrape along the ocean floor, is very effective – so much so that it can devastate everything in its path.

In 2015, the United Nations’ first worldwide ocean assessment found bottom-trawling causes widespread, long-term destruction to deep-sea environments wherever it is done. Scientists have compared it to clear-felling a forest. The practice is banned in the Mediterranean and in shallow waters of the Southern Ocean, and is increasingly restricted by many nations, including Australia.

The UN has repeatedly called for better protection, as well as specific actions to make it a reality. And many nations and organisations are heeding that call.

The science is clear. But the politics is not. International waters in the South Pacific are one of the few areas where deepwater bottom-trawling is still permitted on seamounts – underwater mountains rich in life – and similar features.

Last year, South Pacific nations agreed to protect a minimum of 70% of marine ecosystems vulnerable to damage from fishing. This agreement came from research done largely by New Zealand.

Other countries pushed for a higher level of protection, but New Zealand insisted on 70% to ensure its fishing could continue. These kinds of compromises are common at meetings like this.

The meeting in February was meant to agree on how to make the consensus decision a reality. But it was not to be. Now that NZ has withdrawn support, the original decision remains but without the mechanisms to make it happen. Bottom-trawling will likely continue in the South Pacific.

Why? The new NZ fisheries minister, Shane Jones, has publicly stated he was “keen to ensure that, number one, we’re looking after our own people, looking after jobs and opportunities for economic development to benefit New Zealand.”

While high seas fishing is an important industry for New Zealand, their bottom trawling activity in the South Pacific is small. One vessel fished the bottom in 2021-2022, catching only 20 tonnes of orange roughy. No bottom trawling has happened since then.

Since coming to power, New Zealand’s new government has questioned 2030 renewable energy targets, promised to “address climate change hysteria”, declared mining more important than nature protection – and supported bottom-trawling.

Many of these changes will be of considerable concern to Australia. For the past 15 years, Australia has taken a prominent leadership role – alongside New Zealand – in sustainable ocean management.

With Pacific island nations, Australia and NZ worked long and hard to progress the High Seas Treaty – a breakthrough opening new legal avenues to protect up to 30% of the unregulated high seas where illegal and exploitative fishing practices are common.

The NZ government’s willingness to jettison long collaborative work, abandon agreed commitments and risk existing agreements bodes poorly for cooperation across the Tasman. Australia must sadly now treat New Zealand as an opponent when it comes to protecting the seas and managing fisheries for the long term. ![]()

Lynda Goldsworthy, Research Associate, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is there an alternative to 10,000 kilometres of new transmission lines? Yes – but you may not like it

Building transmission lines is often controversial. Farmers who agree to host new lines on their property may be paid, while other community members protest against the visual intrusion. Pushback against new lines has slowed development and forced the government to promise more consultation.

It’s not a new problem. Communities questioned the routes of earlier transmission lines built during the 1950s-70s to link new coal and hydroelectric plants to the cities.

But this time, the transition has to be done at speed. Shifting from the old coal grid to a green grid requires new transmission lines. In its future system planning, Australia’s energy market operator sees the need for 10,000 kilometres of new transmission lines in the five states (and the Australian Capital Territory) which make up the National Energy Market.

Do we need all of these new transmission lines? Or will the “staggering growth” of solar on houses and warehouses coupled with cheaper energy storage mean some new transmission lines are redundant?

The answer depends on how we think of electricity. Is it an essential service that must be reliable more than 99.9% of the time? If so, yes, we need these new lines. But if we think of it as a regular service, we would accept a less reliable (99%) service in exchange for avoiding some new transmission lines. This would be a fundamental change in how we think of power.

Why Do We Need These New Transmission Lines?

The old grid was built around connecting a batch of fossil fuel plants via transmission lines to consumers in the towns and cities. To build this grid – one of the world’s largest by distance covered – required 40,000 km of transmission lines.

The new grid is based around gathering energy from distributed renewables from many parts of the country. The market operator foresees a nine-fold increase in the total capacity of large scale solar and wind plants, which need transmission lines.

That’s why the market operator lays out integrated systems plans every two years. The goal is to give energy users the best value by designing the lowest-cost way to secure reliable energy able to meet any emissions goals set by policymakers.