inbox and environment news: Issue 617

March 10-16, 2024: Issue 617

Newport's Saved Littoral Rainforest At Hillside Road: New Bushcare Group Begins

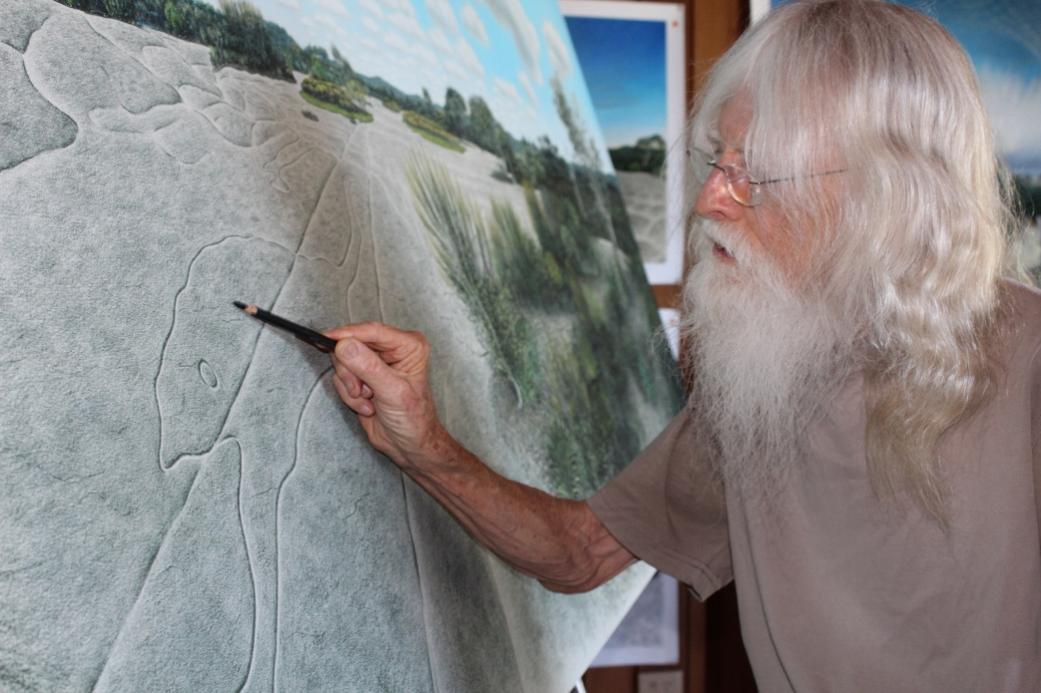

Pittwater Online spoke to Artist Mick Glasheen, who had also been speaking about the same matter in 2017, and was renting a premises on the property at that time.

Having spent time exploring Newport's 'Crown to the Sea' paths, which wend from one side of Bilgola to Newport through the green pockets of Newport and Bilgola reserves, the potential to realise a 'connecting completion of this loop' was envisioned by the residents and Mick.

The land includes significant Littoral Rainforest which is listed as an Endangered Ecologically Community (EEC) under NSW Legislation and Critically Endangered under Commonwealth Legislation. It is adjacent to the public bushland areas called the 'Crown to the Sea', making it a corridor extension to other important habitat and biodiversity rich areas.

Pittwater Online subsequently contacted Newport Residents Association President Gavin Butler, Marita Macrae, President of the Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA), Neil Evers of the Aboriginal support Group, Manly, Warringah, Pittwater and arranged, with Mick as host, an informal morning tea on site so all the people who had spoken about the same thing separately together so they could speak about it as one. The news service also informed MP for Pittwater Rob Stokes about the community's aspiration to secure this land.

These individuals and groups, took it from there - arranging to make a great video (by Bruce Walters with Danielle Bressington), launched an online petition (via PNHA) and liaised with their members (Gavin of Newport Residents and Neil Evers of ASPMWP, PNHA members) Councillors and Council as well as former Pittwater MP Rob Stokes to get this one over the line.

Former Councillors Alex McTaggart and now new Pittwater MP Rory Amon 'stepped up' in particular, speaking out at council meetings for the acquisition of this 2.56 acres of land.

There was lantana and other weeds on this land, which may need extra bushcare volunteer hands to help clear it, now that Council's contractors have completed the initial works.

Confirmation the land had been secured was announced by former Pittwater's MP, The Hon Rob Stokes, then NSW Minister for Planning and Public Spaces was released on Monday, March 11th, 2019, stating that more than 10,000 square metres of Littoral rainforest near Newport will be preserved as public open space thanks to a $4.6 million joint investment by the NSW Government and Northern Beaches Council.

Member for Pittwater and Planning and Public Spaces Minister Rob Stokes said the acquisition will ensure the pristine ecological area is preserved for the next generation.

“Our government is committed to ensuring the people of NSW have access to great public open space,” Mr Stokes said.

“Protecting the environment is a huge priority for the Northern Beaches community, so I am delighted we have been able to preserve endangered rainforest, while protecting an important wildlife corridor and increasing green space in the Sydney basin.”

Then Mayor Michael Regan said the purchase was a huge win for the local community.

“Despite its high environmental value, this land on Hillside Road had been slated for sub-division and significant development, so it’s great we’ve been able to partner with the State government to save it and bring it into public hands,” Mayor Regan said.

“I’d like to thank the many community groups and individuals who fought to have this critical land saved and ensure this incredible outcome became a reality.”

The purchase, co-funded with Northern Beaches Council through the Greater Sydney Open Space Program, demonstrated the NSW Government’s priority to secure and improve green space across the State.

The site was transferred to the Northern Beaches Council for ongoing care and management.

The Council then ran a 'Have Your Say' consultation about the classification for the land; to classify the land as either 'operational' or 'community' land and give public notice of this proposed resolution.

As 'Community Land - for all, and for all time' had been the object of the community's campaign, even for years under Pittwater Council, the feedback and wondering why the council had broached a possibility of making the land 'operational' was responded to in no uncertain terms.

However, as Mick was tenant of 85 Hillcrest at the time, the council was required to undertake this process. For a variety of reasons, including site security, the council wanted to keep this tenancy in place. In order to maintain the tenancy, 85 Hillside Road would be classified 'Operational'.

Under the Local Government Act 1993, all land in Council’s ownership must be classified as either operational or community. Land, such as parks, reserves and other open space is classified as 'community', which means that it is set aside for community uses for the public.

Some land, such as Council depots and land that is being used as an investment, is classified as 'operational' which means it can be used for a broader number of purposes.

The land was formally acquired on 24 June 2021. As three months had passed since acquisition, the classification of the land at 85 Hillside Road (Lot 2 DP 1036400) and 62 Hillside Road, Newport (Lot 1 DP 408800) defaulted to a community classification in accordance with S31(2A) of the Local Government Act.

The land was to be rezoned to a zoning that respects the bushland conservation and public ownership of the land.

A Plan of Management (PoM) was due to be prepared for the site following the transfer of the land from the State Government to Council.

This PoM will include the Land Transfer Agreement signed by the State Government and Northern Beaches Council, which mandates that the majority of the land will be used for public recreation and cannot be sold to a third party. Under the Land Transfer Agreement, which had to be signed by Council before DPIE transferred the land, the land cannot be sold or subdivided and at least 80% of the land must be retained as open space.

The PON's first report (May 2018) shared:

The Newport Bushlink, 'From the Crown to the Sea' comprises the Attunga Reserve, Kanimbla Reserve, the Porters Reserve and the Crown of Newport (McMahon's Creek) Reserve at the end of Hillside road. The work to restore these and create an interlinked walkable route was commenced in 1994 by just four Newport Residents.

The reserves allow walkers to revel in glorious Newport vistas, be among Coastal Heathland landscapes as well as Littoral Rainforest and green lit creeklines. They also provide vital fauna habitat and connection pathways.

The site now on the market is approximately 1.06 ha in size, and includes 0.84 ha of native vegetation (Littoral Rainforest) and 0.22 ha of Urban Native/Exotic Vegetation. The majority of the land consists of rainforest associated species, including Cabbage Tree Palms (Livistona australis), mesic tree species such as Lilly Pillys (Acmena smithii) and Pittosporum sp., ferns; such as the Rough tree fern (Cyathea australis), vines and twiners such as Cissus sp. and sparse tussock grasses such as Lomandra sp.

The site now on the market is approximately 1.06 ha in size, and includes 0.84 ha of native vegetation (Littoral Rainforest) and 0.22 ha of Urban Native/Exotic Vegetation. The majority of the land consists of rainforest associated species, including Cabbage Tree Palms (Livistona australis), mesic tree species such as Lilly Pillys (Acmena smithii) and Pittosporum sp., ferns; such as the Rough tree fern (Cyathea australis), vines and twiners such as Cissus sp. and sparse tussock grasses such as Lomandra sp.

Other species such as Banksia integrifolia (Coastal Banksia), Ficus rubiginosa (Port Jackson Fig), Eucalyptus botryoides (Bangalay), and Allocasuarina littoralis (Forest Oak) occur less frequently in the canopy but have been recorded. Underneath the canopy a small tree layer is present, comprised predominately of Eupomatia laurina (Native Guava), Synoum glandulosum (Scentless Rosewood), Acmena smithii, and Pittosporum undulatum. The exotic tree species Erythrina x sykesii is present in the canopy in the southern half of the site.

A shrub layer is present in most areas dominated by Eupomatia laurina and Synoum glandulosum and juveniles of the trees Livistona australis and Pittosporum undulatum. Other shrubs species present with patchy occurrences include Wilkiea huegeliana (Veiny Wilkiea), Notelaea longifolia, Pittosporum revolutum (Rough-fruited Pittosporum), and Elaeocarpus reticulatus (Blueberry Ash). Vines are common in the understorey and include the species Morinda jasminoides (Sweet Morinda), Smilax australis (Lawyer Vine), Geitonoplesium cymosum (Scrambling Lily).

The ground level has ferns in most areas, the dominant species on site being Doodia aspera (Rasp Fern) and Blechnum cartilagineum (Gristle Fern), and others such as Adiantum aethiopicum (Maidenhair fern), Adiantum hispidulum (Rough Maidenhair Fern), and Calochlaena dubia (False Bracken Fern) occurring less frequently. Other herbaceous species such as Pseuderanthemum variabile (Pastel Flower), Lepidosperma elatius (Tall Sword-sedge), Schelhammera undulata (Lilac Lily), and the grasses Entolasia marginata (Margined Panic) and Oplismenus imbecillis (Creeping Beard Grass) have a scattered distribution in the ground layer.

There has been, as it has been in many Reserves prior to bush regeneration, the encroachment of lantana. There are also patches of privet and other exotic weeds association with areas that have been disturbed by development or run off from adajcent sites.

A total of 73 native species and 68 exotic species were recorded on the site and its parts during previous and subsequent development applications. The overall abundance of native and exotic species varies across the land, with native species predominating.

The site slopes steeply from the north-western side to the south-eastern boundary. There is extensive sandstone outcropping and boulders on the upper slopes, wonderful outcrops through which rain would wend.

The site adjoins Attunga Reserve and an old path around its northern perimeter once led to and joined that behind Porter's. A gambol across from Attunga would allow hikers to enjoy the great views and breeze from the peak of the site before ambling along the road to the reserve through which McMahon's creek wends.

People who live adjacent to site report seeing a powerful owl nesting in a tree on the land and a chorus of birds can be heard, during the day, singing from its green understorey. No nocturnal count of animals (or fauna that moves at night) is available but that which frequents the reserves around the land range from ring-tail possums to reptiles to a wide range of resident or seasonally returning birds.

Sounds like a paradise because it is a paradise - and would certainly appeal to anyone who wants a lofty home within a quiet corner with a glorious view and pockets of cooling green flora and fauna around them.

As the land is currently on offer as a subdivision of six large blocks, the sales pitch being a potential 'gated community', and previous discussions to have this green space acquired have availed none, the April 2018 announced NSW Government’s $290 million Open Spaces and Green Sydney package, may be just one way (or potential option for some funding) to get everyone happy this time.

- Newport's Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Celebrating Over 20 Years Of Community Volunteer Bushcare Results - December 2017

- Potential For Newport Paradise To Be Expanded: A Greener Sydney Spark! - May 2018

- Newport's 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Complete the Loop Update - July 2018

- Community Hope To Add To Newport Bushlinked Reserves Receives Council Support: Funding Will Be Sought - August 2018

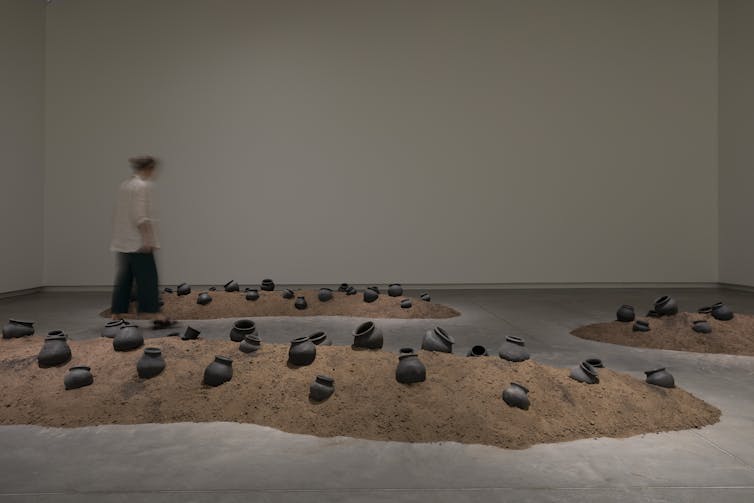

- Michael Glasheen Art Exhibition To Go On The Road To Support Newport Acquisition Of Crown To The Sea Land Add-In To 'Complete The Loop' - November 2018

- From Palm Beach To Pasadena: Mick Glasheen's Drawing On The Land - GARIGAL COUNTRY Opens - December 2018

- NSW Government Working To Deliver More Green Space For Newport - March 2019

- Council Briefs - May 2019 Meeting

- Littoral Rainforest On The Newport-Bilgola Verge Secured As Public Space - September 2019

The view from the land saved for the public by former Pittwater's MP The Hon. Rob Stokes and the Northern Beaches Council.

Increase Tree Vandalism Penalties: NSW Parliamentary Petition

.jpg?timestamp=1708790130470)

Tree Vandalism On Harbour Trust Land At Goat Paddock, Woolwich

Eastern Blue Groper Changes: Have Your Say

Iconic Blue Groper Now Protected In NSW

$23.8 Million To Cut Carbon Emissions: Example - The Duck Creek Blue Carbon Project

%20-%20Copy.jpg?timestamp=1710009523757)

.jpg?timestamp=1710009587225)

- Site history assessment Underway

- Hydrologic assessment and project extent mapping Underway

- Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment Complete

- Mosquito Management Plan

- Project operation and maintenance plan

- deliver abatement at scale

- deliver co-benefits alongside carbon abatement

- use innovative delivery to maximise benefits to land managers.

- 24 Degree Forest

- Wilmot Cattle Company

- Regen Farmers Mutual

- Greening Australia

- World Wide Fund for Nature Australia

- NSW Department of Primary Industries.

- Reforestation by environmental or mallee plantings: A reforestation by environmental or mallee plantings project involves establishing and maintaining vegetation such as trees or shrubs on land that has been clear of forest for at least 5 years. You can plant either a mix of trees, shrubs and understory species native to the local area or species of mallee eucalypts.

- Estimation of soil organic carbon sequestration using measurement and models: To be eligible under this method, projects must introduce one or more of the following activities:

- apply nutrients to the land

- apply lime to remediate acid soils

- apply gypsum to remediate sodic or magnesic soils

- undertake new irrigation

- re-establish or rejuvenate a pasture by seeding establishing or pasture cropping

- establishing, and permanently maintaining, a pasture where there was previously no or limited pasture, such as on cropland or bare fallow

- alter the stocking rate, duration or intensity of grazing

- retain stubble after a crop is harvested

- convert from intensive tillage practices to reduced or no tillage practices

- modify landscape or landform features to remediate land

- use mechanical methods to add or redistribute soil

- use legume species in cropping or pasture system, or

- use a cover crop to promote soil vegetation cover or improve soil health or both.

- Tidal restoration of carbon blue ecosystems method (coastal wetlands): The blue carbon method enables Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs) to be earned by projects that remove or modify tidal restriction mechanisms and allow tidal flow to be introduced to an area of land. This results in the rewetting of completely or partially drained coastal wetland ecosystems and the conversion of freshwater wetlands to brackish or saline wetlands. The method enables ACCUs to be earned for the establishment of coastal wetland ecosystems that occurs as a result of project activities. There are three components within coastal wetland ecosystems that contribute to carbon abatement for a blue carbon project:

- soil carbon sequestration (through vertical accretion)

- carbon sequestered in above and below ground vegetation biomass

- emissions avoided from introducing tidal flow.

- reforestation by environmental or mallee plantings

- estimation of soil organic carbon sequestration using measurement and models

- beef cattle herd management

- tidal restoration of blue carbon ecosystems.

- High impact partnership grant guidelines (Round 1 - December 2022)

- Frequently asked questions

Wolli Creek Regional Park Officially Expanded

Wolli Creek Preservation Society: Protecting the natural and cultural values of Wolli Creek Valley

- [White A.W.and Burgin S. 2004. "Current status and future prospects of reptiles and frogs in Sydney’s urban-impacted bushland reserves". In Lunney D. and Burgin S. Urban wildlife: more than meets the eye. Mosman, NSW. Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales.]

- [Schell C.B. and Burgin S. 2003. Swimming against the current: the Brown Striped Marsh Frog (Limnodynastes peronii) success story. Australian Zoologist 32: 401–405.]

- DECC. 2007. Wolli Creek site profile: report for the Sydney metropolitan catchment management authority. Hurstville, NSW. Department of Environment and Climate Change.

- DECC. 2008. Management plan for the Green and Golden Bell Frog – key population on the lower Cooks River. Sydney, NSW. Department of Environment and Climate Change.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2023, December 19). Wolli Creek Regional Park. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19:13, March 9, 2024, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wolli_Creek_Regional_Park&oldid=1190692963

Early Autumn Moth + Caterpillar That Will Become A Moth

Lichen Moths (Arctiidae: Lithosiinae) - Alternative Name/S: Footman Moths

Painted Apple Moth Caterpillar

- Dahlia ( Dahlia pinnata, ASTERACEAE ),

- Cypress ( Cupressus, CUPRESSACEAE ),

- Lupins ( Lupinus, FABACEAE ),

- Geranium ( Pelargonium x zonale, GERANIACEAE ),

- Gladiola ( Gladiolus byzantinus, IRIDACEAE ),

- Albizia ( Albizia species, MIMOSACEAE ),

- Banana Fruit ( Musa acuminata, MUSACEAE ),

- Passionfruit ( Passiflora edulis, PASSIFLORACEAE ),

- Primrose ( Primula, PRIMULACEAE ),

- Roses ( Rosa odorata, ROSACEAE ),

- Gardenia ( Gardenia jasminoides, RUBIACEAE ),

- ( Gardenia jasminoides, RUTACEAE ),

- Willow ( Salix, SALICACEAE ),

- Native Cherry ( Exocarpus cupressiformis, SANTALACEAE ),

- Lantana ( Lantana camara, VERBENACEAE ).

- Coral Pea ( Hardenbergia species, FABACEAE ),

- Wattles ( Acacia species, MIMOSACEAE ),

- Bottlebrush ( Callistemon species, MYRTACEAE ),

- Ferns ( POLYPODIOPHYTA ), and

- Spider Flowers ( Grevillea species, PROTEACEAE ).

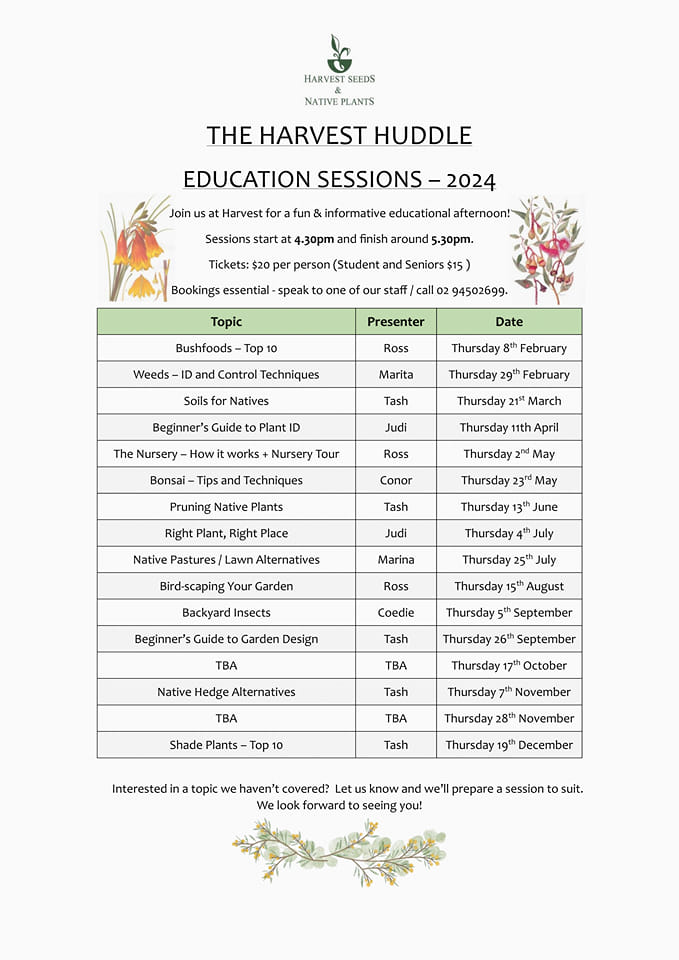

Harvest Seeds & Native Plants: Education Sessions 2024 - "The Harvest Huddle"

Notice Of 1080 Baiting: February 1 - July 31 2024

Please note the following notification of continuous and ongoing fox control using 1080 POISON with ground baits and canid pest ejectors (CPE’s) in Sydney Harbour National Park, Garigal National Park, Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, and Lane Cove National Park. As part of this program, baiting also occurs on North Head Sanctuary managed by Sydney Harbour Federation Trust and the Australian Institute of Police Management facility at North Head.

This provides notification for the 6 monthly period of 1 February 2024 – 31 July 2024.

Warning signs are displayed at park entrances and other entrances to the baiting location to inform the public of 1080 baiting.

1080 Poison for fox control is used in these reserves in a continuous and ongoing manner. This means that baits and ejectors (CPE’s) remain in the reserves and are checked/replaced every 6 – 8 weeks.

1080 use at these locations is in accordance with NSW pesticides legislation, relevant 1080 Pesticide Control Orders and the NPWS Vertebrate Pesticides Standard Operating Procedures.

A series of public notifications occur on a 6 monthly basis including; alerts on the NPWS website, public notices in local papers, Area pesticide use notification registers and to the NPWS call centre.

If you have any further general enquiries about 1080, or for specific program enquiries please contact the local NPWS Area office:

For further information please call the local NPWS office on:

NPWS Sydney North (Middle Head) Area office: 9960 6266

NPWS Sydney North (Forestville) Area office: 9451 3479

NPWS North West Sydney (Lane Cove NP) Area office: 8448 0400

NPWS after-hours Duty officer service: 1300 056 294

Sydney Harbour Federation Trust: 8969 2128

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association: Second PNHA Nature Event 2024

NEW At Eco House & Garden(At Kimbriki): 'Supporting School & Community Composts Workshop'

Where you can become part of the (waste) solution in our 3-hour workshop.

See below for more details and for bookings go to 👉https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1162545

Kimbriki Resource Recovery Centre: Early Childhood Educators Professional Development Day

As part of Kimbriki's 2024 Eco House & Garden Educational Calendar, this year we introduce the Early Childhood Educators Professional Development Day on Friday 22nd March. For more details and bookings 👉 https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1162305

Upcoming Events At Permaculture Northern Beaches

Saving Our Seeds is a crucial part of our own food chain and it enables us to grow our own food and plants with no additional costs! The strongest seeds are locally grown over many generations and well adapted to local conditions - so your plants will thrive while you save on costs. Join us with seed-saving guest speakers Mylene Turban, and Elle Sheather to have an overview and to inspire you to get seed-saving!

Saving Our Seeds is a crucial part of our own food chain and it enables us to grow our own food and plants with no additional costs! The strongest seeds are locally grown over many generations and well adapted to local conditions - so your plants will thrive while you save on costs. Join us with seed-saving guest speakers Mylene Turban, and Elle Sheather to have an overview and to inspire you to get seed-saving!About

Stony Range Nursery

Stay Safe From Mosquitoes

- Applying repellent to exposed skin. Use repellents that contain DEET, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus. Check the label for reapplication times.

- Re-applying repellent regularly, particularly after swimming. Be sure to apply sunscreen first and then apply repellent.

- Wearing light, loose-fitting long-sleeve shirts, long pants and covered footwear and socks.

- Avoiding going outdoors during peak mosquito times, especially at dawn and dusk.

- Using insecticide sprays, vapour dispensing units and mosquito coils to repel mosquitoes (mosquito coils should only be used outdoors in well-ventilated areas)

- Covering windows and doors with insect screens and checking there are no gaps.

- Removing items that may collect water such as old tyres and empty pots from around your home to reduce the places where mosquitoes can breed.

- Using repellents that are safe for children. Most skin repellents are safe for use on children aged three months and older. Always check the label for instructions. Protecting infants aged less than three months by using an infant carrier draped with mosquito netting, secured along the edges.

- While camping, use a tent that has fly screens to prevent mosquitoes entering or sleep under a mosquito net.

Mountain Bike Incidents On Public Land: Survey

- Mountain Bike Incidents On Public Land: Survey Launched To Gather Data On What's Happening To Public Parks - Community Land - Bush Reserves In Pittwater

- Mother Brushtail Killed On Barrenjoey Road: Baby Cried All Night - Powerful Owl Struck At Same Time At Careel Bay During Owlet Fledgling Season: calls for mitigation measures - The List of 'What You can Do' as requested

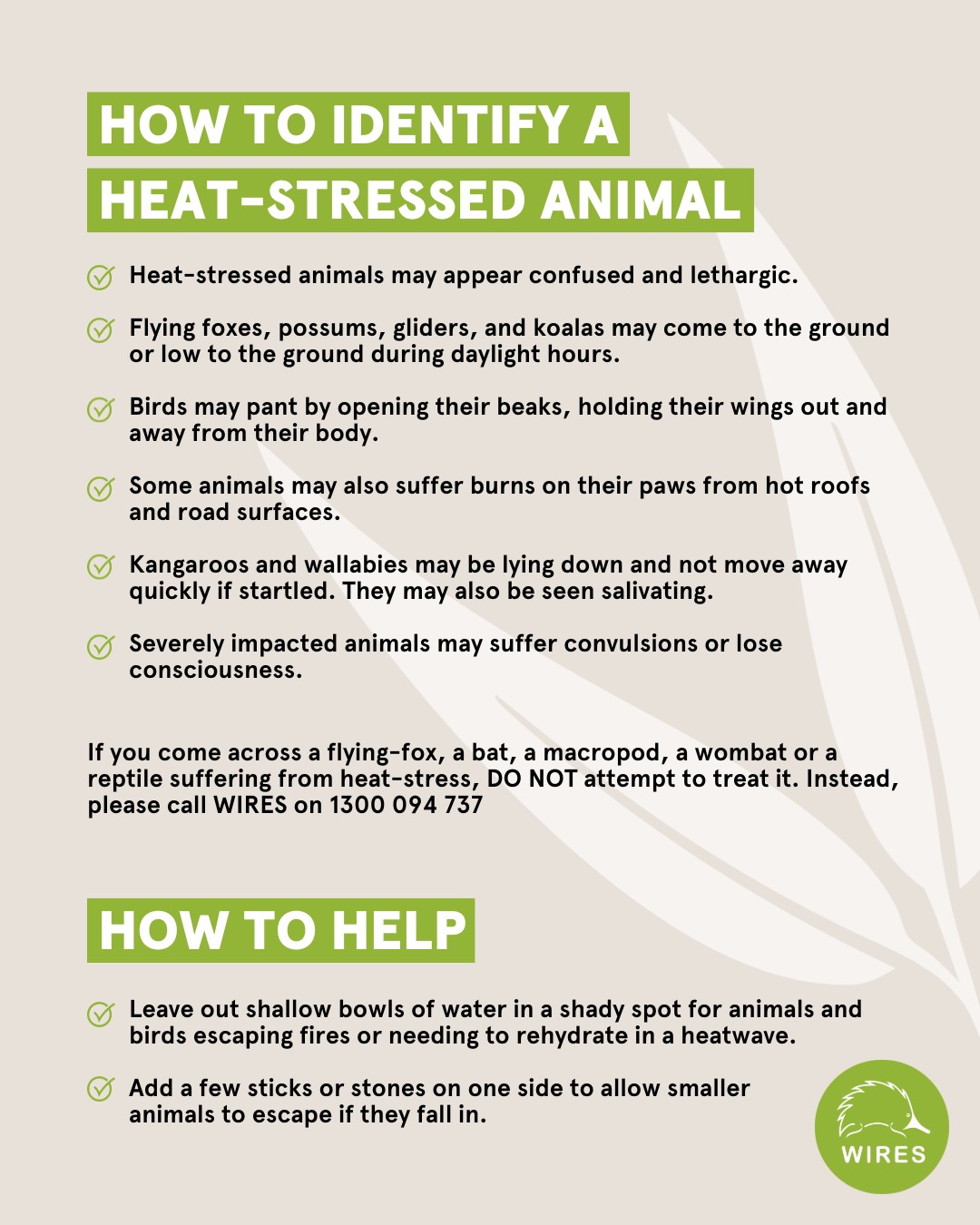

Please Look Out For Wildlife During Heatwave Events

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

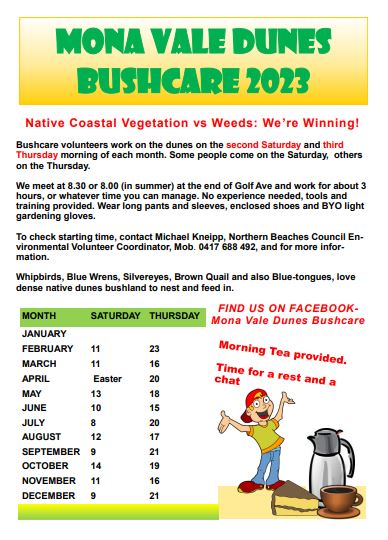

Bushcare In Pittwater: Where + When

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

- Ringtail Posse: 1 – February 2023; Anna Maria Monticelli: King Parrots/Water Dragons - Jacqui Scruby: Loggerhead Turtle - Lyn Millett OAM: Flying-Foxes - Kevin Murray: Our Backyard Frogs - Miranda Korzy: Brushtail Possums

- Ringtail Posse: 2 - March 2023; Kevin Murray: Tawny Frogmouth - Kayleigh Greig: Red-Bellied Black Snake - Bec Woods: Australian Water Dragon - Margaret Woods: Owlet-Nightjar - Hilary Green: Butcher Bird - Susan Sorensen: Wallaby

- Ringtail Posse 3 - April 2023: Jeffrey Quinn: Kookaburra, Tom Borg McGee: Kookaburra, Stephanie Galloway-Brown: Bandicoot, Joe Mills: Noisy Miner

- Ringtail Posse 4 May 2023 - Andrew Gregory: Powerful Owl, Marita Macrae: Pale-Lipped Or Gully Shadeskink, Jools Farrell: Whales & Seals, Nicole Romain: Yellow-Tailed Black Cockatoo

- Ringtail Posse 5: June 2023 - Lynleigh Greig OAM: Snakes, Dick Clarke: Diamond Python, Selena Griffith: Glossy Black-Cockatoo, Eric Gumley: Bandicoot

- Ringtail Posse 6: July 2023 - Sonja Elwood: Long-Nosed Bandicoot, Dr. Conny Harris: Swamp Wallaby, Neil Evers: Bandicoot, Bill Goddard: Bandicoot

- Ringtail Posse 7: August 2023 - Geoff Searl OAM: Tawny Frogmouth, Peter Macinnis: Echidna, Peter Carter: Ringtail Possum, Nathan Wellings; Kookaburra

- Ringtail Posse 8: September 2023 - Saving Sydney's Last Koalas; Logging Now Stopped In Future Koala Park By Minns Government - ''Is There Time To Save Sydney's Last Koalas Too?'' Asks: John Illingsworth, WIRES, Sydney Wildlife Rescue, Save Sydney Koalas, The Sydney Basin Koala Network, The Help Save The Wildlife & Bushlands In Campbelltown Group, Appin Koalas Animal Rescue Service, Patricia and Barry Durham, Sue Gay, Save Mt. Gilead, Paola Torti Of The International Koala Intervention Group

- Ringtail Posse 9: October 2023 - David Palmer OAM: Bandicoots, Helen Pearce: Brushtail Possum, Amina Kitching: Goanna, David Goudie: Ringtails Possums + Bandicoots + Owls

- Mother Brushtail Killed On Barrenjoey Road: Baby Cried All Night - Powerful Owl Struck At Same Time At Careel Bay During Owlet Fledgling Season: calls for mitigation measures - The List of what you can do for those who ask 'What You I Do' as requested

- Ringtail Posse 10: November 2023 - Stop Wildlife Roadkill Group: You Can Help By Using The Wildlife Incident Mapping Website

More Green Space To Enhance Liveability In NSW Communities: Metropolitan Greenspace Program + Community Gardens Program Grants Now Open

- Metropolitan Greenspace Program. All councils in the Greater Sydney region and Central Coast Council are eligible and encouraged to apply by 29 April 2024. Successful applicants will be announced in June 2024.

- Places to Roam Community Gardens program. Applications close on 29 March 2024.

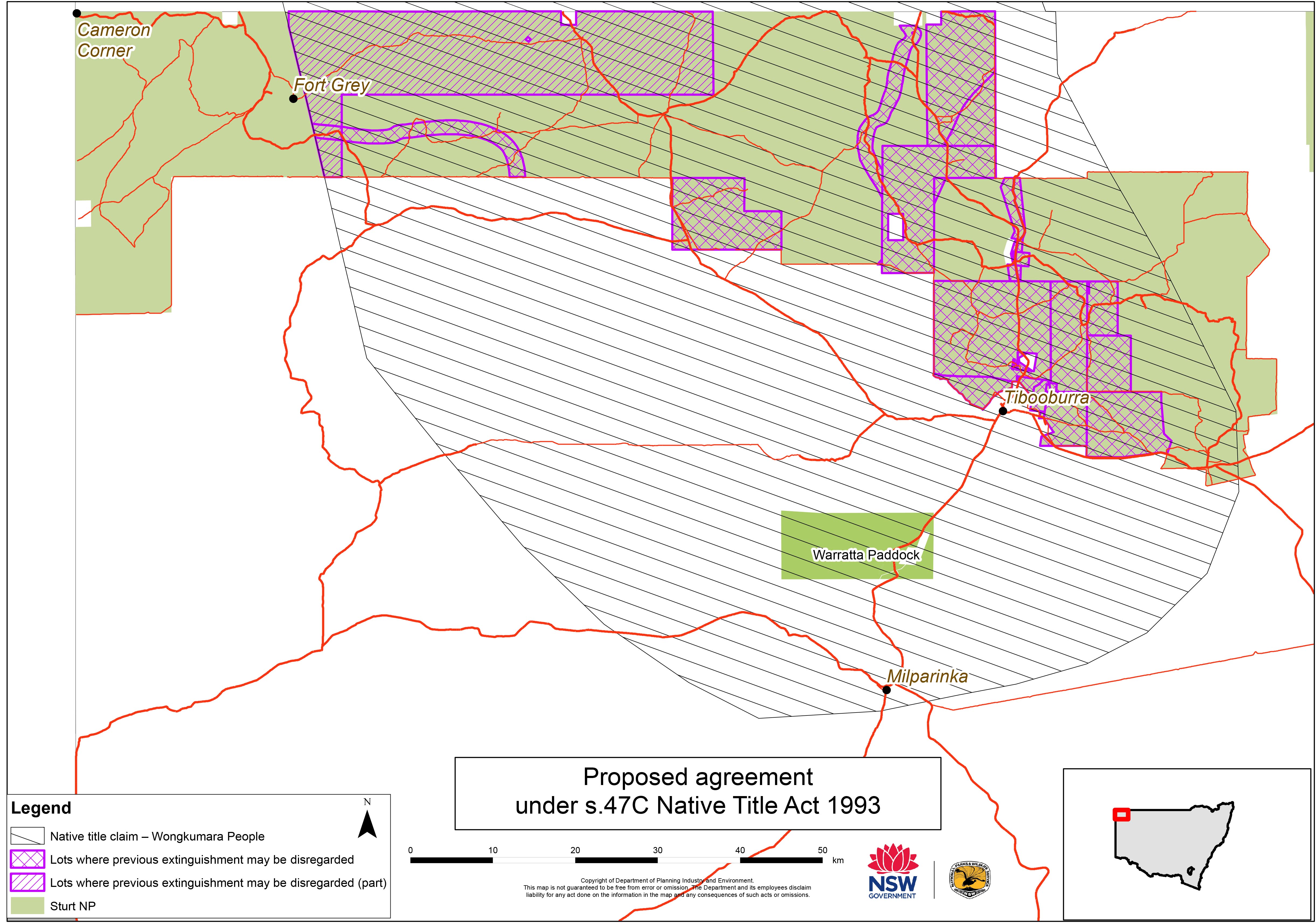

Wongkumara People – Native Title Act: Have Your Say

- Informal submission

- Mailout

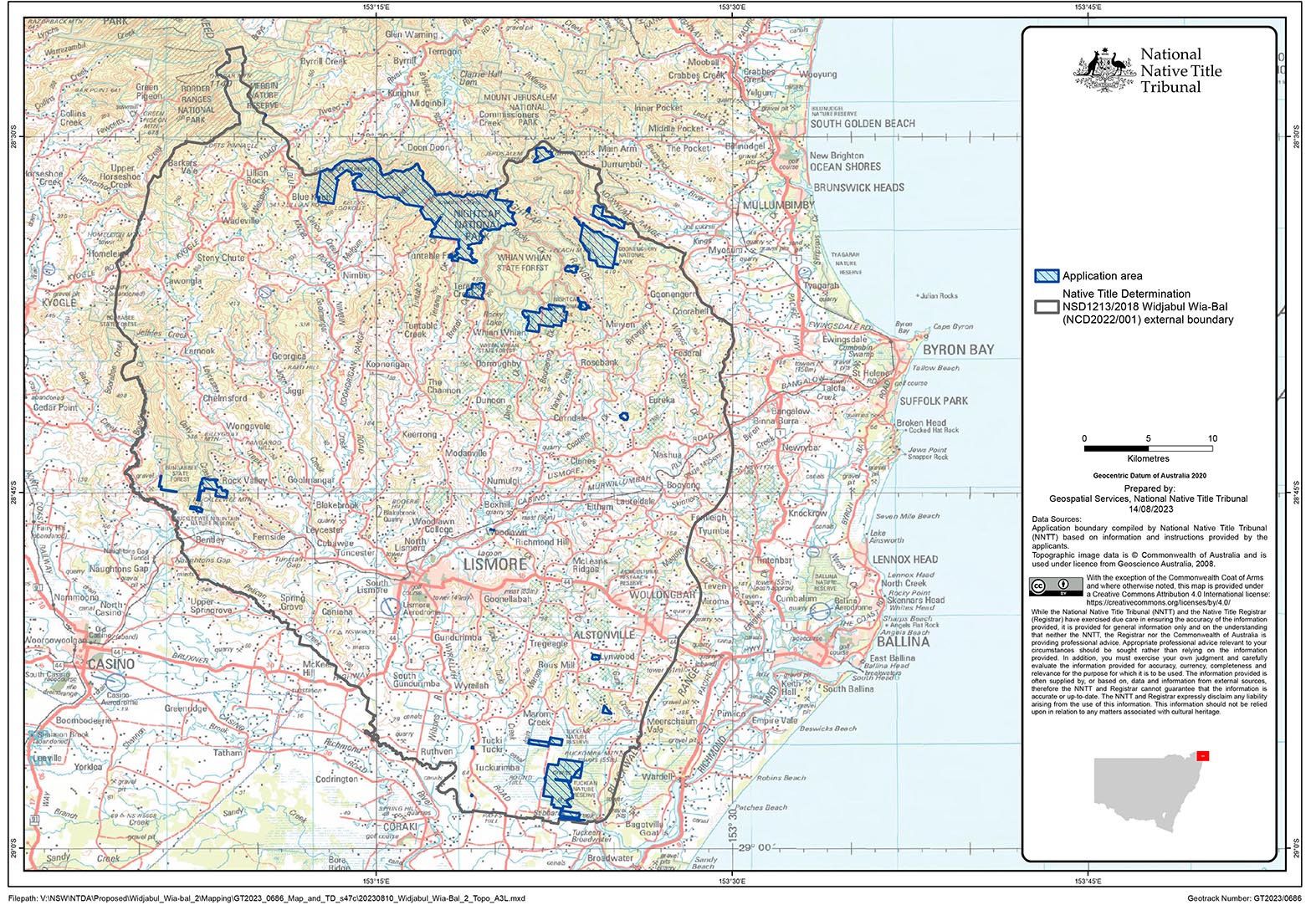

Widjabul Wia-Bal People – Notice Under The Native Title Act: Have Your Say

- Boatharbour Nature Reserve

- Tuckean Nature Reserve

- Muckleewee Mountain Nature Reserve

- Goonengerry National Park

- Victoria Park Nature Reserve

- Mount Jerusalem National Park

- Nightcap National Park

- Davis Scrub Nature Reserve

- Snows Gully Nature Reserve

- Tucki Tucki Nature Reserve

- Andrew Johnson Big Scrub Nature Reserve

- Whian Whian State Conservation Area.

Environmental Grants Connect To Country: Applications Close 2 April 2024

Independent Review Of Small-Scale Titles: Have Your Say

Crown Land Management Act 2016 Review: Have Your Say

.jpg?timestamp=1708537972385)

Coastal Floodplain Drainage Project: Have Your Say

- addressing the complexity, time and costs associated with the approvals process

- reducing the impact of these works and activities on downstream water quality, aquatic ecosystems, communities and industries.

- Option 1: One-stop shop webpage - A single source of information on the various approvals that may be required by government agencies for coastal floodplain drainage works.

- Option 2: Drainage applications coordinator - A central officer(s) to guide the applicant through the approvals processes for all NSW government agencies (Department of Planning and Environment’s Water Group, Planning, Crown Lands, and the Department of Primary Industries — Fisheries) and answer the applicant’s questions about their individual location and proposed works. The drainage applications coordinator would complement both Option 1 and Option 3.

- Option 3: Concurrent assessment - Concurrent assessment of applications by relevant government agencies.

- Option 4: Risk-based approach - NSW Government agencies would use a standardised risk matrix to compare the type and extent of the drainage works against the acidic water and blackwater potential of the drainage area to identify the level of risk associated with the proposed works. The identified level of risk could then be used to determine the level of information required from applicants, the level of assessment required by the approval authority, and the types of conditions applied to any approvals.

- Option 5: Drainage work approvals under the Water Management Act 2000 - Switch on drainage work approvals under the Water Management Act 2000. Two different methods of implementation are possible:

i. a drainage work approval would be required only when works are proposed and for the area of works onlyii. a drainage work approval could apply to existing and new drainage works across the entire drainage network.

Within either of these two methods, one of three different approaches for public authorities could be applied:

a. require public authorities to hold a drainage work approvalb. allow for public authorities to hold a conditional exemption from requiring approvalsc. exempt public authorities from requiring a drainage work approval.

- Option 6: Streamlining of Fisheries and Crown Land approvals through the use of drainage work approvals - Drainage work approvals, particularly under Option 5(ii), have the potential to deliver a catchment-wide consideration of the drainage network. This would provide greater certainty to other agencies such as Fisheries and Crown Land that environmental impacts have been considered and appropriate conditions applied, supporting them to assess and issue approvals more quickly.

- Tuesday 5 March 2024 - Register to attend

- Friday 8 March 2024 - Register to attend

Australia’s Eucalypt Of The Year Voting Opens Today In Your Backyard!

- Dwarf Apple Angophora hispida

- Ghost Gum Corymbia aparrerinja

- Red-flowering Gum Corymbia ficifolia

- Silver Princess Eucalyptus caesia

- Argyle Apple Eucalyptus cinerea

- Yellow Gum Eucalyptus leucoxylon

- Risdon Peppermint Eucalyptus risdonii

- Coral Gum Eucalyptus torquata

- Heart-leaved Mallee Eucalyptus websteriana

- Lemon-flowered Gum Eucalyptus woodwardii

Milestone Reached In Doubling Landcare Funding

- Fund the employment of up to 7.5 full-time equivalent staff to provide centralised support to host organisations and coordinators funded through the Program.

- Establish a Shared Services Hub that provides centralised support to host organisations and coordinators funded under the Local and Regional Coordinators Grants across a range of business services, but specifically administration and human resources.

- Implement and manage a state Community of Practice including Landcare state gatherings, conferences and regional events.

- Implement and manage a Digital Landcare solution to improve reporting processes and knowledge sharing for program participants.

- Develop and maintain strategic partnerships and leverage investment, to increase Landcare’s self-sustenance and reduce reliance on direct NSW Government funding over the medium to longer term.

Cultural burning is better for Australian soils than prescribed burning, or no burning at all

Imagine a landscape shaped by fire, not as a destructive force but as a life-giving tool. That’s the reality in Australia, where Indigenous communities have long understood the intricate relationship between fire, soil and life. Cultural burning has been used for millennia to care for landscapes and nurture biodiversity. In contrast, government agencies conduct “prescribed burning” mainly to reduce fuel loads.

In our new research, we compared cultural burning to agency-led prescribed burning or no burning. We studied the effects on soil properties such as moisture content, density and nutrient levels.

Both fire treatments increased soil moisture and organic matter, while reducing soil density. That means burning improved soil health overall. But cultural burning was the best way to boost soil carbon and nitrogen while also reducing soil density, which improves the soil’s ability to nurture plants.

Understanding the effects of different fire management techniques is crucial for developing more sustainable land management practices. By studying what happens to the soil, we can work out how best to promote healthy, resilient ecosystems while also reducing risks of uncontrolled bushfires.

The Vital Role Of Fire

Fire has shaped Australian landscapes for millions of years, transforming ecosystems and influencing biodiversity.

For Indigenous Australians, fire is not just a tool but a way of life. Fire is used to care for Country, for cultural purposes including ceremonies, to promote new plant growth and food resources, and to facilitate hunting and gathering.

Cultural burning is only ever conducted when it will benefit the health of Country. It is a practice deeply rooted in Indigenous knowledge and traditions. Fires are small, slow and cool. Practitioners read signs in the environment in relation to the local flora and fauna that provide guidance on the right time to burn.

In comparison, prescribed burning, conducted by government agencies, is principally conducted to reduce fuel loads and minimise the risk of wildfires. Fires are often larger and burn hotter than cultural burning.

In recent times, bushfires have become more frequent and severe in parts of Australia. So understanding and supporting Indigenous-led fire management practices is becoming increasingly important for sustainable land management.

Unlocking The Secrets Of Soil Health

Our new research sheds light on the impact of fire management techniques on soil properties. The study was conducted on the south coast of New South Wales, on land managed by the Ulladulla Local Aboriginal Land Council. At this plot, one area of land experienced no burn, another was burnt by NSW Rural Fire Service and another experienced a cultural burn.

While the area burnt was relatively small, about 5,000 square metres for each plot, it can still help shed a light on the effect of fire treatments on soil properties.

We found both agency-led prescribed burning and cultural burning increased soil moisture levels. There may be different reasons for this. For soils that experienced the cultural burn, the extra moisture could be explained by the reduction in soil density, which promotes water flow. For soils that experienced the agency-led prescribed burn, where density didn’t decrease much, it’s possible the hotter fire removed the water-repellant layer of soil that sometimes develops following a fire, allowing more moisture to soak in.

Cultural burning had a more pronounced effect on reducing soil density and increasing organic matter content. Having more organic matter in the soil means more nutrients such as carbon and nitrogen are available to plants. Lower density improves soil structure. Both improve the capacity of ecosystems to withstand environmental stress such as drought and wildfire.

These findings suggest cultural burning not only benefits soil health but also helps make ecosystems more resilient, by providing more water and nutrients that native plants need.

Embracing Indigenous Wisdom

Indigenous communities use cultural land management practices, of which cultural burning is one tool, to care for Country as kin. They do not see themselves as separate to the environment. Instead their practices are guided by place-based knowledge that weaves human, spiritual and ecological needs together in a symbiotic relationship where one cannot thrive without the other.

Supporting Indigenous-led fire practices is not just about what it can do for the environment. It’s also a recognition of the deep cultural and spiritual connections Indigenous communities have with the land.

By learning from and working with Indigenous communities, we can foster a more harmonious relationship with Country, one that benefits both people and the environment.

Rekindling Our Relationships

Indigenous fire management practices offer invaluable wisdom and the potential to transform our approach to land stewardship.

By embracing these practices, we can nurture healthier soils, promote biodiversity, and foster more resilient ecosystems.

Practically, to make this possible, ongoing investment is required to build the capacity of Indigenous communities to fulfil their obligations to care for Country. Policies must be updated to allow greater access to Country and to reduce red tape and bureaucracy.

There is a danger here. Government agencies often want to incorporate or take on some of the principles of cool burns themselves, forgetting the cultural aspects and the need for this to be Indigenous-led. We must understand this is not just about managing fires, it’s about rekindling our relationship with the land and learning from those who have lived in harmony with it for thousands of years. ![]()

Anthony Dosseto, Professor, University of Wollongong; Katharine Haynes, Honorary Senior Research Fellow, University of Wollongong; Leanne Brook, CEO, Ulladulla Local Aboriginal Land Council, Indigenous Knowledge, and Victor Channell, Murramarang and Walbunga Elder, Indigenous Knowledge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Gomeroi win puts native title holders in a stronger position to fight fossil fuel projects on their land

Lily O'Neill, The University of Melbourne and Rebekkah Markey-Towler, The University of MelbourneIn a significant win for the Gomeroi People, the Federal Court has ruled climate change impacts must be properly considered when determining whether a fossil fuel project can go ahead on native title land.

This is the latest in a series of disputes involving First Nations people fighting to prevent coal, oil and gas projects on their land. It’s part of the growing trend of First Nations people spearheading climate litigation. For example, cases involving Raelene Cooper, Dennis Tipakalippa, and Pabai Pabai.

This week’s legal decision is the first of its kind because the Court ruled climate change must be part of the public interest test before the National Native Title Tribunal can allow a project to proceed on native title land.

The decision puts native title holders in a stronger position when fighting to prevent future fossil fuel projects. There’s no guarantee of success, but it’s clear climate impacts can no longer be dismissed.

An Uphill Battle For Traditional Owners

The win for the Gomeroi People was about a dispute relating to native title approvals made by the National Native Title Tribunal in 2022. This gave the Australian oil and gas company Santos permission to proceed with plans to extract gas from forest and farmland around Narrabri, in northern New South Wales.

Up to 850 gas wells would be drilled over 20 years to extract coal seam gas. The wells and infrastructure, including gas processing and water treatment facilities, would be located within 1,000 hectares of the 95,000ha project area.

Under the Native Title Act companies like Santos are required to negotiate with the land’s Traditional Owners for at least six months with a view to reaching an agreement.

But an obligation to negotiate does not mean there is an obligation to reach an agreement. Traditional Owners cannot veto the project. And even without an agreement the company can apply to the tribunal to grant native title approvals.

Companies know they are likely to win once they get to the tribunal. The tribunal has only ever sided with native title holders trying to prevent resource extraction project on their Country three times, most recently back in 2011. In comparison, it has sided with the developer 149 times.

The tribunal must look at a range of factors when reaching its decision. This includes the public interest.

The Gomeroi People argued greenhouse gas emissions from the Santos project would cause unacceptable damage to their Country, and also contribute to global climate change, and therefore the project was not in the public interest.

They enlisted an expert witness, the late and highly respected climate scientist Professor Will Steffen, who told the tribunal in 2021 that the project was expected to result in between 109.75 million and 120.55 million tonnes of extra carbon dioxide (or equivalent) into the atmosphere.

The continued expansion of the fossil fuel industry, Steffen said, would result in the Narrabri region experiencing “more extreme heat, further and more intense droughts, harsher fire danger weather, and heavier rainfall when it occurs, all of which will continue to increase in frequency and intensity”.

The tribunal’s then president, John Dowsett, concluded that while he accepted greenhouse gas emissions were warming the planet, it was not in his remit to consider climate change when looking at the public interest. Rather, he said, he had to consider factors such as whether the project was of “economic significance to Australia, the State and the region, as well as Aboriginal people”.

He ruled that it was, and also opined that Steffen should have been more deferential to the NSW Independent Planning Commission’s views that the project would have an acceptable impact on climate. Steffen was just “one scientist”, Dowsett said, and it was “disturbing” that he should dismiss the authority’s view.

Dowsett even referenced the classic climate fallacy about there being two sides to the argument: “there are conflicting views concerning climate change and knowledge is rapidly expanding”.

A Groundbreaking Win

The Federal Court was clearly not impressed, this week delivering the tribunal a judicial slap. The court said the definition of what was in the public interest was wide, and in this case, consideration of climate change impacts clearly fell within that definition.

In her judgement, Federal Court Chief Justice Debra Mortimer pointed out that Steffen was not just one scientist, but rather was on a panel of experts of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, representing the world’s leading climate scientists.

Gomeroi Traditional Owners reacted to the decision with happiness, pride and celebration.

Gomeroi Elder Maria (Polly) Cutmore released a statement saying:

Santos now have to decide what they are going to do, we strongly encourage them to withdraw their operations from the Pilliga forest and our floodplains for good. That would respect our culture and law and Santos would be better off for it.

Santos responded to the case by saying it has “at all times negotiated with the Gomeroi people in good faith”.

This is not the first time First Nations people have led the way in holding decision makers accountable for the climate consequences of their actions. Indeed, Australia has been a particularly active jurisdiction for climate litigation, the jurisdiction with the second-highest number of cases worldwide. The Australian and Pacific Climate Litigation database we run at the University of Melbourne records these cases.

We expect more of these disputes to arise in the future.

What Comes Next?

For the Gomeroi People, the matter will likely be sent back to the tribunal with instructions to revisit the decision. This time, we hope, climate change will be forefront in the decision-making process.

The broader implications of this latest ruling are still unclear. It is conceivable the tribunal will reconsider the climate impacts and yet still arrive at the same conclusion.

Alternatively, this case could be the start of more significant engagement with climate issues in Australian courts, led by First Nations people.![]()

Lily O'Neill, Senior Research Fellow, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne and Rebekkah Markey-Towler, PhD Candidate, Melbourne Law School, and Research fellow, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

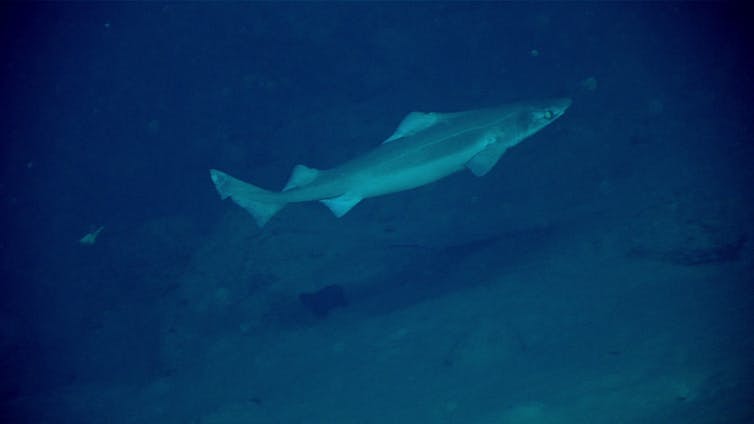

Fished for their meat and liver oil, many remarkable deep-water sharks and rays now face extinction

The deep ocean, beyond 200 metres of depth, is the largest and one of the most complex environments on the planet. It covers 84% of the world’s ocean area and 98% of its volume – and it is home to a great diversity of species.

Yet it remains among the least studied places on Earth, with no comprehensive assessments of the state of deep-water biodiversity and no policy-relevant indicators to guide the taking of species targeted by fisheries.

This also applies specifically to deep-water sharks and rays, even though these species make up nearly half of the recognised diversity of all cartilaginous fishes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras) we know today.

Our research highlights how our growing impact on the deep ocean raises the threat to these species.

Using the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species, we show that the number of threatened deep-water sharks and rays has more than doubled between 1980 and 2005, following the emergence and expansion of deep-water fishing.

We estimate one in seven species (14%) are threatened with extinction.

Fishing For Meat And Oil

Deep-water sharks and rays are in a group of marine vertebrates that are most sensitive to overexploitation. This is because of their long lifespans (possibly up to 450 years for the Greenland shark, Somniosus microcephalus) and low reproduction rate (only 12 pups in a lifetime for the gulper shark, Centrophorus granulosus).

These biological characteristics make them similar to formerly exploited, and now highly protected, marine mammals.

The Greenland shark and the leafscale gulper shark (Centrophorus squamosus), for example, have population growth rates comparable to the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) and the walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), respectively. Despite their known inherent vulnerability, there are very few species-specific management actions for deep-water sharks.

Our research shows that overfishing is the primary threat to deep-water sharks and rays. They are used for their meat and liver oil, which drives targeted fisheries but also incidental capture, meaning any accidental catches are retained by fisheries targeting other species.

In many nations, deep-water sharks and rays are regarded as a welcome catch because of the high value of their liver oil and high demand for skate meat. These are not new trades, but the global expansion and diversification of use, particularly for shark liver oil, is a relatively new phenomenon.

Targeted shark liver oil fisheries are boom-and-bust fisheries. They drive shark populations down and raise the extinction risk over short periods of time (less than 20 years). There is particular interest in shark liver oil for applications in cosmetics and human health products, including vaccine adjuvants.

This is despite a lack of evaluation of possible human health risks of using liver oil for medical purposes (deep-water sharks can bioaccumulate heavy metals and contaminants at concentrations at or above regulatory thresholds).

Need For Global Deep-Water Shark Action

There have been tremendous triumphs in shark conservation, including the regulation of the global trade in fins from threatened coastal and pelagic species. But deep-water sharks have been largely left out of conservation discussions.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora has yet to see a listing proposal for a deep-water shark or ray.

We call for trade and fishing regulations specific to deep-water sharks and rays to ensure legal, traceable and sustainable trade and to prevent their further endangerment.

There are presently limited ways of determining which species comprise internationally traded liver oil. It may be a byproduct of sustainable fisheries but the current lack of regulations could also be masking the trade of threatened species.

We also propose closures of areas important to deep-water sharks and rays to provide refuge from fishing and promote recovery and long-term survival. Nearly every deep-water shark is threatened by incidental capture.

Retention bans have been implemented in some regions as a mitigation strategy, including European waters managed under the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. But they don’t prevent the mortality of prohibited species that are released after being brought to the surface from great depths.

We need efforts to prevent capture in the first place. There is now a global push to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030 through the Convention on Biological Diversity, which New Zealand has ratified.

Our work shows protecting 30% of the deep ocean (200-2000m) would provide around 80% of deep-water shark species with at least partial spatial protection across their range. If a worldwide prohibition of fishing below 800m were to be implemented, it would provide 30% vertical refuge for one third of threatened deep-water sharks and rays.

Even though the extinction risk for these species is much lower than that of their shallow-water relatives, their potential for recovery from overexploitation is much reduced because of their long lifespans and low fecundity. One study estimated it would take 63 years or more for the little gulper shark (Centrophorus uyato) to recover to just 20% of its original population size.

We know many shark populations around the world are in trouble. Threatened deep-water sharks have little chance of recovery without immediate action. Now is the time to implement effective conservation actions in the deep ocean to ensure half of the world’s sharks and rays have a refuge from the global extinction crisis.![]()

Brittany Finucci, Fisheries Scientist, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research and Cassandra Rigby, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

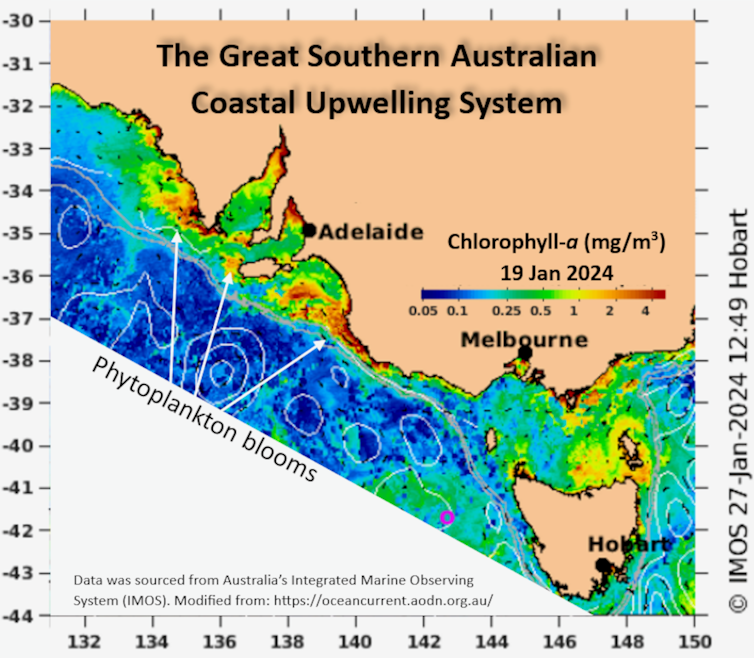

The Southern Ocean upwelling is a mecca for whales and tuna that’s worth celebrating and protecting

The Great Southern Australian Coastal Upwelling System is an upward current of water over vast distances along Australia’s southern coast. It brings nutrients from deeper waters to the surface. This nutrient-rich water supports a rich ecosystem that attracts iconic species like the southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) and blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda).

The environmental importance of the upwelling is one reason the federal government this week declared a much-reduced zone for offshore wind turbines in the region. The zone covers one-fifth of the area originally proposed.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of a research publication that revealed the existence of the large seasonal upwelling system along Australia’s southern coastal shelves. Based on over 20 years of scientific study, we can now answer many critical questions.

How does this upwelling work? How can it be identified? Which marine species benefit from the upwelling? Does the changing climate affect the system?

Where Do The Nutrients Come From?

Sunlight does not reach far into the sea. Only the upper 50 metres of the water column receives enough light to support the microscopic phytoplankton – single-celled organisms that depend on photosynthesis. This is the process of using light energy to make a simple sugar, which phytoplankton and plants use as their food.

As well as light, the process requires a suite of nutrients including nitrogen and phosphorus.

Normally, the sunlight zone of the oceans is low in nitrogen. Waters deeper than 100m contain high levels of it. This deep zone of high nutrient levels is due to the presence of bacteria that decompose sinking particles of dead organic matter.

Upwelling returns nutrient-rich water to the sunlight zone where it fuels rapid phytoplankton growth. Phytoplankton production is the foundation of a productive marine food web. The phytoplankton provides food for zooplankton (tiny floating animals), small fish and, in turn, predators including larger fish, marine mammals and seabirds.

The annual migration patterns of species such as tuna and whales match the timing and location of upwelling events.

What Causes The Upwelling?

In summer, north-easterly coastal winds cause the upwelling. These winds force near-surface water offshore, which draws up deeper, nutrient-enriched water to replace it in the sunlight zone.

The summer winds also produce a swift coastal current, called an upwelling jet. It flows northward along Tasmania’s west coast and then turns westward along Australia’s southern shelves.

Satellites can detect the areas of colder water brought to the sea surface. Changes in the colour of surface water as a result of phytoplankton blooms can also be detected. This change is due to the presence of chlorophyll-a, the green pigment of phytoplankton.

From satellite data, we know the upwelling occurs along the coast of South Australia and western Victoria. It’s strongest along the southern headland of the Eyre Peninsula and shallower waters of the adjacent Lincoln Shelf, the south-west coast of Kangaroo Island, and the Bonney Coast. The Bonney upwelling, now specifically excluded from the new wind farm zone, was first described in the early 1980s.

Coastal upwelling driven by southerly winds also forms occasionally along Tasmania’s west coast.

Coastal wind events favourable for upwelling occur regularly during summer. However, their timing and intensity is highly variable.

On average, most upwelling events along Australia’s southern shelves occur in February and March. In some years strong upwelling can begin as early as November.

Recent research suggests the overall upwelling intensity has not dramatically changed in the past 20 years. The findings indicate global climate changes of the past 20 years had little or no impact on the ecosystem functioning.

What Are The Links Between Upwelling, Tuna And Whales?

The Great Southern Australian Coastal Upwelling System features two keystone species – the ecosystem depends on them. They are the Australian sardine (Sardinops sagax) and the Australian krill (Nyctiphanes australis), a small, shrimp-like creature that’s common in the seas around Tasmania.

Sardines are the key diet of larger fish, including the southern bluefin tuna, and various marine mammals including the Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea). Phytoplankton and krill are the key food source for baleen whales. They include the blue whales that come to Australia’s southern shelves to feed during the upwelling season.

Unlike phytoplankton and many zooplankton species that live for only weeks to months, krill has a lifespan of several years. It does not reach maturity during a single upwelling season. It’s most likely the coastal upwelling jet transports swarms of mature krill from the waters west of Tasmania north-westward into the upwelling region.

So the whales seem to benefit from two distinct features of the upwelling: its phytoplankton production and the krill load imported by the upwelling jet.

Seasonal phytoplankton blooms along Australia’s southern shelves are much weaker than other large coastal upwelling systems such as the California current. Nonetheless, their timing and location appear to fit perfectly into the annual migration patterns of southern bluefin tuna and blue whales, creating a natural wonder in the southern hemisphere.![]()

Jochen Kaempf, Associate Professor of Natural Sciences (Oceanography), Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Yabby traps and discarded fishing tackle can kill platypuses - it’s time to clean up our act

Recreational fishing is a popular pastime in Australia’s inland rivers and streams. Unfortunately in the process, many people are unwittingly killing platypuses.

The animals can become trapped in nets commonly used to catch yabbies such as “Opera House traps” (so-called because their shape resembles the sails of the Sydney Opera House). The enclosed structure stops platypuses swimming back to the surface to breathe, causing them to drown in minutes.

Enclosed traps are banned in most states, but they are still being used. They are sold online and can be shippped across Australia. During our field research, we frequently encounter these traps and clumps of discarded fishing line. We have also conducted research on the bodies of platypuses killed by these hazards.

It’s time for a national ban on these inhumane traps. And recreational fishing waste should be kept out of our waterways. We must save our platypuses, before it’s too late.

A Natural Wonder

The platypus is one of Australia’s most loved and iconic species. These semi-aquatic, air breathing monotremes (egg-laying mammals) can be naturally found in waterways of the east coast, Tasmania and Kangaroo Island.

But there are growing concerns for the species’ survival. Platypuses are becoming scarce and in some areas, completely disappearing from waterways.

The animals spend most of their time foraging in freshwater creeks and rivers. They have very poor eyesight underwater and use special sensors in their duck-shaped bill to locate prey. A trap full of live yabbies can attract platypuses, but this tempting feast may be their last meal.

Closing In On Enclosed Traps

Closed-top traps are baited then submerged in a river or stream for hours or a day, before being hauled out.

The traps funnel creatures into an enclosed space where they can’t escape. They are designed to catch freshwater crayfish (known as yabbies or marron). But they also inadvertently trap aquatic animals such as platypuses, freshwater turtles and the native water rat, rakali.

But there are wildlife-friendly alternatives. For example, some nets are open at the top while others have a hinged lid that can be pushed open by a larger animal, such as a platypus, as it tries to escape.

Opera House style, closed-top yabby traps are now banned in Tasmania, Victoria, the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales and South Australia.

Queensland allows use west of the Dividing Range, where platypuses are not thought to exist, or on private property. Restrictions around the size of trap entrance holes were introduced in 2015.

A Litany Of Platypus Deaths

The Australian Platypus Conservancy found 41% of reported platypus deaths from 1980 to 2009 were caused by drowning in enclosed nets.

Meanwhile platypuses have continued to drown in closed-top traps. In 2022, four reportedly died in one trap at Dorrigo on the mid-north coast of New South Wales. In 2021, a platypus died in Queensland’s Broken River and in 2018, one trap drowned seven in Victoria’s Werribee River.

Aside from deaths by closed-top traps, many platypuses become entangled in abandoned fishing line as they search for food along the bottom of waterways.

The animal’s tapered shape, duck-shaped bill and short webbed feet make it hard to free themselves. They are prone to getting wrapped in rings or loops of plastic, rubber or metal rubbish.

In 2021 a Victorian study of 54 cases of platypus entanglement found litter commonly encircled the neck (68%). Almost one in five were wrapped “from in front of a shoulder to behind the opposite foreleg” (22%). Others had plastic around their torso or jaw.

That study also found platypuses in greater Melbourne were up to eight times more likely to become tangled in litter than those in regional Victoria. That’s because urban areas tend to be more polluted.

Fishing line can cut through skin and muscle, causing a slow painful death. Entangled platypuses can also drown after they become caught on underwater debris.

We study how heavy metals and other emerging contaminants accumulate in platypuses. Together with the community, local and state governments and wildlife organisations such as Taronga Zoo, we collect dead platypuses to examine their organs and body tissues.

On a trip this month to regional NSW for water quality testing and sampling, we found multiple instances of tangled fishing line and an abandoned submerged Opera House trap.

Swapping Traps And Binning Trash

Between December 2018 and February 2019, when the Victorian Fisheries Authority invited people to swap their old closed top nets for a free “wildlife friendly” net, 20,000 traps were exchanged.

OzFish is currently running a Yabby Trap Round Up in NSW and SA. The Opera House traps are recycled and turned into useful fishing products.

Recreational fishers should also round up their used fishing line and hooks. The “TAngler bin” initiative encourages safe disposal. Since 2006, more than 350 TAngler bins have been installed at fishing hotspots in Victoria, NSW and Queensland, collecting more than ten tonnes of discarded fishing line.

A study in known platypus habitat on the Hawkesbury-Nepean River in Greater Sydney found more than 2.5km of fishing line was disposed of correctly in the bins in just three years.

Save Our Platypuses

Closed-top nets should be banned nationwide. This would ensure recreational fishers can no longer buy these traps and then use them in banned areas, as is happening now.

Net exchange programs should continue, in conjunction with a national awareness campaign, so the closed-top traps already sold are all handed in.

And both fishers and the wider community can take action by collecting discarded fishing line and nets.

Platypuses need all the help they can get. With our support, these beloved iconic animals can live on in Australian waterways. ![]()

Katherine Warwick, PhD Candidate, Western Sydney University; Ian A. Wright, Associate Professor in Environmental Science, Western Sydney University, and Michelle Ryan, Senior lecturer, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Big businesses will this year have to report their environmental impacts – but this alone won’t drive change

This year, large businesses in Australia will likely have to begin reporting their environmental impacts, climate risks and climate opportunities.

The final draft of Australia’s new mandatory climate disclosure laws are due any day now, following consultation.

These laws are meant to increase transparency about how exposed companies are to risks from climate change, and will require companies to look into and share what impact their activities have on the environment. This, the government hopes, will accelerate change in the corporate sector.

But will it help lower emissions? I don’t think so. We don’t have a carbon tax, which means many companies have no financial incentive to actually lower their emissions. (The strengthened Safeguard Mechanism applies to about 220 big emitters, but they can simply buy offsets and avoid harder change.)

By themselves, climate disclosures will not trigger the change we need.

Why Are These Laws Being Proposed?

In June 2023, the newly formed International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) released a set of sustainability standards and climate disclosures.

These standards have influenced Australia’s draft laws.

In planning mandatory corporate disclosures on climate and environment, Australia is following similar efforts overseas. In 2022, the United Kingdom began to roll out mandatory reporting on climate risks and opportunities for the largest UK companies (those with more than 500 employees and A$970 million in turnover).

Once the Australian legislation comes into effect, it will require large companies and asset owners to publish their climate-related risks and opportunities.

In the draft legislation, companies would have to evaluate and report on their direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions from sources they own or control and from sources such as purchased electricity.

From July this year, the laws would require disclosures from companies with 500 employees, $1 billion in assets or $500 million in revenue. Over time, this would expand to medium-sized companies. From July 2027, companies with 100 employees, $25 million in assets or $50 million in revenue would have to share this information.

Sustainability reports will be subject to external auditing and directors would be personally liable for the accuracy of the disclosures – with one major exception.

For many Australian companies, it’s already proving too hard to account for Scope 3 emissions – the greenhouse gas emissions upstream and downstream in a company’s operations, such as the emissions from gas burned after we export it.

As these emissions occur outside a company’s direct control, accounting for them is a complex task costing time and money. Only some companies have voluntarily started to report their Scope 3 emissions in anticipation of future regulatory change.

The draft legislation exempts companies from the need to report Scope 3 emissions for their first year of reporting and proposes limited liability for these disclosures for a fixed three-year period.

This means companies can simply come up with a best-guess estimate, rather than reporting their actual Scope 3 emissions, which can make up 65–95% of their overall emissions. In some sectors, such as the integrated oil and gas industry, Scope 3 emissions can comprise more than six times the sum of Scope 1 and 2 emissions. Woolworths’ Scope 3 emissions account for 94% of emissions.

What Are Disclosure Laws Meant To Do?

You can see why the government is introducing these laws. To nudge corporate Australia towards a greener future, it helps to know what impact your business has – and what risks it is exposed to. It will also be useful for investors.

But it will not drive rapid decarbonisation. Critics have pointed out that reporting and disclosure alone will not lead to a shift away from carbon-intensive business operations. Disclosures give the appearance of action rather than real action. If there are no stronger policies accompanying, disclosures act as window dressing for global financial markets.

Our existing policies do not require organisations to make genuine changes in terms of their emissions. Unless organisations abandon their reliance on fossil fuels and substantially decarbonise their operations, we are simply not going to get any change.

These laws also come with a cost. The regulatory burden and compliance costs for Australian companies will not be trivial, especially for companies which haven’t reported on climate or sustainability before.

We already have a shortage of trained reporting, auditing and assurance professionals able to do climate and environment work, following years of minimal action on climate change in Australia. To fix this will require substantial and rapid upskilling.

These costs should give us pause. It’s worth thinking through how much emphasis we place on disclosures to drive change versus policies that would actually drive change, such as mandating that large companies have to reduce their direct emissions 10% a year.

Australian companies can only benefit from these laws if they use the data unearthed by disclosure to rethink how they operate, invest and green their supply chains towards sustainability. This may mean investing in clean technology, shifting from polluting transport fleets to electric, or reconsidering how they produce their products.

And to do that, of course, companies will need to see supportive government policies.

These Laws Can Be Useful – But Not Alone

Assuming the laws pass, big companies will begin assessing and reporting their emissions and environmental impact from July this year.

In doing so, Australia will align itself with international efforts for more transparency. Requiring companies to scrutinise and disclose their environmental impact will give corporate leaders the data needed to look for greener ways to run their business. But this assumes they have the interest and time to do so.

This isn’t a quick fix for climate change. To be worth the cost, Australia will need to link climate-related financial disclosures to clear policies designed to bring down emissions.

Disclosure policies produce disclosures. Emission reduction policies produce emission reductions. ![]()

Martina Linnenluecke, Professor of Environmental Finance at UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In a dangerously warming world, we must confront the grim reality of Australia’s bushfire emissions

Robert Hortle, University of Tasmania and Lachlan Johnson, University of TasmaniaIn the four years since the Black Summer bushfires, Australia has become more focused on how best to prepare for, fight and recover from these traumatic events. But one issue has largely flown under the radar: how the emissions produced by bushfires are measured and reported.

Fires comprised 4.8% of total global emissions in 2021, producing about 1.76 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO₂). This exceeds the emissions of almost all individual countries except the biggest emitters of China, the United States, India and Russia.

It’s crucial to accurately track the greenhouse gas emissions bushfires produce. However, the modelling and reporting of bushfire emissions is a complex, poorly understood area of climate science and policy.

The University of Tasmania recently brought together leading scientists and policymakers to discuss Australia’s measuring and reporting of bushfire emissions. The resulting report, just released, shows where Australia must improve as we face a fiery future.

Getting A Read On Bushfire Emissions

By the end of this century, the number of extreme fire events around the world is expected to increase by up to 50% a year as a direct result of human-caused climate change.

Emissions from bushfires fuels global warming – which in turn makes bushfires even more destructive. Estimating these emissions is a complicated and technical task, but it is vital to understanding Australia’s carbon footprint.

Australia reports on emissions from bushfires according to rules defined by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and as part of our responsibilities under the Paris Agreement.

Countries estimate bushfire emissions in different ways. Some rely on default data provided by the UNFCCC. In contrast, Australia’s modelling combines the area of burned land with highly specific local data on the types of fuel burned (such as leaves, bark and dead wood) and the amount of different types of gas these fuels emit. This makes it among the most sophisticated approaches in the world.

More Transparency Is Needed

Australia’s modelling may be sophisticated but it can also be confusing – even for those who follow climate policy closely. One reason is the complex way we differentiate between “natural” fires (those beyond human control) and “anthropogenic” or human-caused fires such as controlled fuel-reduction burns.

Emissions from natural fires are reported to the UNFCCC, but do not initially count towards Australia’s net emissions calculations. This is consistent with guidance from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

However, we believe that to improve transparency and accountability, the federal government should work with the states and territories to provide a separate breakdown of natural and human-caused fire emissions. This data should be made publicly available to provide a clearer picture of bushfire emissions and the impact of climate change on large fires.

Where We Must Improve

As mentioned above, emissions from natural fires do not initially count towards Australia’s net calculations. Consistent with other countries, our modelling assumes that emissions will be offset after the fires because forest regrowth captures carbon from the atmosphere.

This approach is based on current scientific evidence. For example, within two years of the Black Summer fires, 80% of the burned area was almost fully recovered.

If monitoring of a fire site shows regrowth has not fully offset emissions after 15 years, the difference is retrospectively added to Australia’s net emissions for the year of the original fire.