Book Of The Month - June/July 2024: Voss By Patrick White

Voss (1957) is the fifth published novel by Patrick White. It is based upon the life of the 19th-century Prussian explorer and naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt, who disappeared while on an expedition into the Australian outback.

The novel centres on two characters: Voss, a German, and Laura, a young woman, orphaned and new to the colony of New South Wales. It opens as they meet for the first time in the house of Laura's uncle and the patron of Voss's expedition, Mr Bonner.

Johann Ulrich Voss sets out to cross the Australian continent in 1845. After collecting a party of settlers and two Aboriginal men, his party heads inland from the coast only to meet endless adversity. The explorers cross drought-plagued desert, then waterlogged lands until they retreat to a cave where they lie for weeks waiting for the rain to stop. Voss and Laura retain a connection despite Voss's absence and the story intersperses developments in each of their lives. Laura adopts an orphaned child and attends a ball during Voss's absence.

The travelling party splits in two and nearly all members eventually perish. The story ends some 20 years later at a garden party hosted by Laura's cousin Belle Radclyffe (née Bonner) on the day of the unveiling of a statue of Voss. The party is also attended by Laura Trevelyan and the one remaining member of Voss's expeditionary party, Mr Judd.

The strength of the novel comes not from the physical description of the events in the story but from the explorers' passion, insight and doom. The novel draws heavily on the complex character of Voss. The spirituality of Australia's indigenous people also infuses the sections of the book set in the desert.

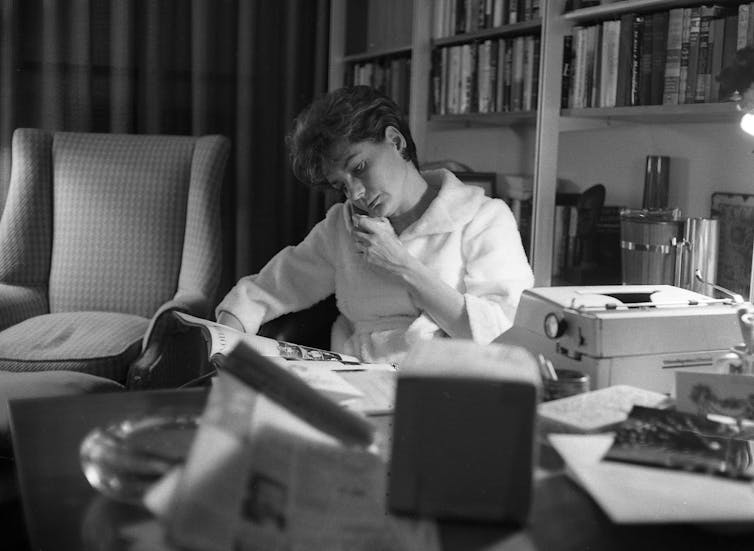

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1973

The Australian Patrick White has been awarded the 1973 Nobel Literature Prize “for an epic and psychological narrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature”, as it says in the Swedish Academy’s citation. White’s growing fame is based chiefly on seven novels of which the earliest masterly work is The Aunt’s Story, a portrayal imbued with remarkable feeling of a lonely, unmarried, Australian woman’s life during experiences that extend also to Europe and America. The book with which White really made his name, however, was The Tree of Man, an epically broad and psychologically discerning account of a part of Australian social development in the form of two people’s long life together, and struggle against outward and inward difficulties.

Another aspect of Australia is shown in Voss, in which a fanatical explorer in the country’s interior meets his fate: an intensive character study against the background of the fascinating Australian wilds. The writer displays yet another kind of art in Riders in the Chariot, with special emphasis on his cystic and symbolic tendencies: a sacrificial drama, tense, yet with an everyday setting, in the midst of current Australian reality. From contrasting viewpoints, The Solid Mandala gives a double portrait of two brothers, in which the sterilely rational brother is set against the fertilely intuitive one, who is almost a fool in the eyes of the world.

White’s last two books are among his greatest feats, both as to size and to frenzied building up of tension. The Vivisector is the imaginary biography of an artist, in which a whole life is disclosed in a relentless scrutiny of motives and springs of action: an artist’s untiring battle to express the utmost while sacrificing both himself and his fellow-beings in the attempt. The Eye of the Storm places an old, dying woman in the centre of a narrative which revolves round, and encloses, the whole of her environment, past and present, until we have come to share an entire life panorama, in which everyone is on a decisive dramatic footing with the old lady.

Particularly, these latest books show White’s unbroken creative power, an ever deeper restlessness and seeking urge, an onslaught against vital problems that have never ceased to engage him, and a wrestling with the language in order to extract all its power and all its nuances, to the verge of the unattainable. White’s literary production has failings that belong to great and bold writing, exceeding, as it does, different kinds of conventional limits. He is the one who, for the first time, has given the continent of Australia an authentic voice that carries across the world, at the same time as his achievement contributes to the development, both artistic and, as regards ideas, of contemporary literature.

_______________________________________________________

Patrick Victor Martindale White (28 May 1912 – 30 September 1990) was a British-born Australian writer who published 12 novels, three short-story collections, and eight plays, from 1935 to 1987.

White was born in Knightsbridge, London, to Victor Martindale White and Ruth (née Withycombe), both Australians, in their apartment overlooking Hyde Park, London on 28 May 1912. His family returned to Sydney, Australia, when he was six months old. As a child he lived in a flat with his sister, a nanny, and a maid while his parents lived in an adjoining flat. In 1916 they moved to a house in Elizabeth Bay that many years later became a nursing home, Lulworth House, the residents of which included Gough Whitlam, Neville Wran, and White's partner Manoly Lascaris.

At the age of four White developed asthma, a condition that had taken the life of his maternal grandfather. White's health was fragile throughout his childhood, which precluded his participation in many childhood activities.

He loved the theatre, which he first visited at an early age (his mother took him to see The Merchant of Venice at the age of six). This love was expressed at home when he performed private rites in the garden and danced for his mother's friends.

At the age of five he attended kindergarten at Sandtoft in Woollahra, in Sydney's Eastern Suburbs, followed by 2 years at Cranbrook School.

At the age of ten White was sent to Tudor House School, a boarding school in Moss Vale in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, in an attempt to abate his asthma. It took him some time to adjust to the presence of other children. At boarding school, he started to write plays. Even at this early age, White wrote about palpably adult themes. In 1924 the boarding school ran into financial trouble, and the headmaster suggested that White be sent to a public school in England, a suggestion that his parents accepted.

Lulworth, White's childhood home in Elizabeth Bay, Sydney

White struggled to adjust to his new surroundings at Cheltenham College, England, describing it later as "a four-year prison sentence". He withdrew socially and had a limited circle of acquaintances. Occasionally, he would holiday with his parents at European locations, but their relationship remained distant. But he did spend time with his cousin Jack Withycombe during this period, and Jack's daughter Elizabeth Withycombe became a mentor to him while he was writing his first book of poems, Thirteen Poems between the years 1927–29.

While at school in London White made one close friend, Ronald Waterall, an older boy who shared similar interests. White's biographer, David Marr, wrote that "the two men would walk, arm-in-arm, to London shows; and stand around stage doors crumbing for a glimpse of their favourite stars, giving a practical demonstration of a chorus girl's high kick ... with appropriate vocal accompaniment". When Waterall left school White again withdrew. He asked his parents if he could leave school to become an actor. The parents compromised and allowed him to finish school early if he came home to Australia to try life on the land. They felt he should work on the land rather than become a writer, and hoped his work as a jackaroo would temper his artistic ambitions.

White spent two years working as a stockman at Bolaro, a 73-square-kilometre (28 sq mi) station near Adaminaby on the edge of the Snowy Mountains in south-eastern Australia. Although he grew to respect the land, and his health improved, it was clear that he was not suited to this work.

In 1936, White met the painter Roy De Maistre, 18 years his senior, who became an important influence in his life and work. The two men never became lovers but remained firm friends. In White's own words, "He became what I most needed, an intellectual and aesthetic mentor". They had many similarities: both were gay and felt like outsiders in their own families, for whom both harboured ambivalent feelings yet maintained close lifelong links with them, particularly their mothers. They also both appreciated the benefits of social standing and its connections. Christian symbolism and biblical themes are common to both artists' work.

White dedicated his first novel Happy Valley to De Maistre, and acknowledged De Maistre's influence on his writing. In 1947 De Maistre's painting Figure in a Garden (The Aunt) was used as the cover for the first edition of White's The Aunt's Story. White bought many of De Maistre's paintings, all of which in 1974 he gave to the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Toward the end of the 1930s White spent time in the United States, including Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and New York City – artistic hotbeds at the time, where he wrote The Living and the Dead. By the time World War II broke out he had returned to London and joined the British Royal Air Force. He was accepted as an intelligence officer, and was posted to the Middle East. He served in Egypt, Palestine, and Greece before the war was over. While in the Middle East he had an affair with a Greek army officer, Manoly Lascaris, who was to become his life partner.

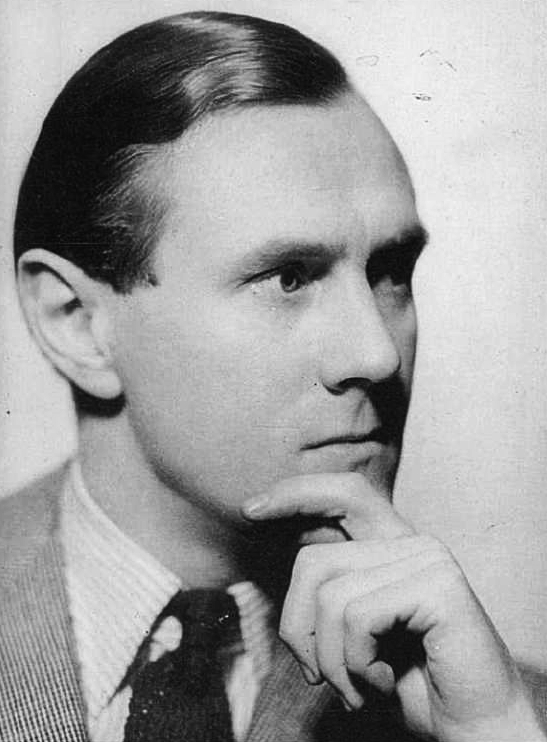

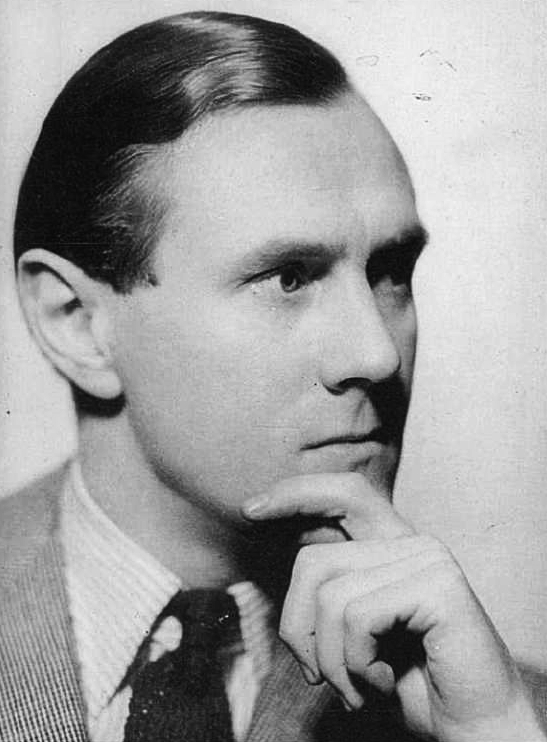

White, circa 1940s

White and Lascaris lived together in Cairo for six years before moving in 1948 to a small farm purchased by White at Castle Hill, now a Sydney suburb but then semi-rural. He named the house "Dogwoods", after trees he planted there. They lived there for 18 years, selling flowers, vegetables, milk, and cream as well as pedigree puppies.

Patrick_White_house_Castle_Hill-2.jpg?timestamp=1718312104659)

White's house in Castle Hill, Sydney. Photo: By Sardaka

After the war, when White had settled down with Lascaris, his reputation as a writer increased with publication of The Aunt's Story and The Tree of Man in the United States in 1955 and shortly after in the United Kingdom. The Tree of Man was released to rave reviews in the United States, but in what had become a typical pattern, it was panned in Australia. White had doubts about whether to continue writing after his books were largely dismissed in Australia (three of them having been called 'un-Australian' by critics), but decided to persevere, and a breakthrough in Australia came when his next novel, Voss, won the inaugural Miles Franklin Literary Award.

In 1961, White published Riders in the Chariot, a bestseller and a prize-winner, garnering a second Miles Franklin Award. A number of White's books from the 1960s depict the fictional town of Sarsaparilla; his collection of short stories, The Burnt Ones, and the play, The Season at Sarsaparilla. Clearly established in his reputation as one of the world's great authors, he remained a private person, resisting opportunities for interviews and public appearances, though his circle of friends widened significantly.

Deciding not to accept any more prizes for his work, White declined both the $10,000 Britannia Award and another Miles Franklin Award. Harry M. Miller proposed to work on a screenplay for Voss but nothing came of it. He became an active opponent of literary censorship and joined a number of other public figures in signing a statement of defiance against Australia's decision to participate in the Vietnam War. His name had sometimes been mentioned as a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, but in 1971, after losing to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, he wrote to a friend: "That Nobel Prize! I hope I never hear it mentioned again. I certainly don't want it; the machinery behind it seems a bit dirty, when we thought that only applied to Australian awards. In my case to win the prize would upset my life far too much, and it would embarrass me to be held up to the world as an Australian writer when, apart from the accident of blood, I feel I am temperamentally a cosmopolitan Londoner".

Nevertheless, in 1973, White did accept the Nobel Prize "for an epic and psychological narrative art, which has introduced a new continent into literature". His cause was said to have been championed by a Scandinavian diplomat resident in Australia.[19] White enlisted Nolan to travel to Stockholm to accept the prize on his behalf. The award had an immediate impact on his career, as his publisher doubled the print run for The Eye of the Storm and gave him a larger advance for his next novel. White used the money from the prize to establish a trust to fund the Patrick White Award, given annually to established creative writers who have received little public recognition. He was invited by the House of Representatives to be seated on the floor of the House in recognition of his achievement. White declined, explaining that his nature could not easily adapt itself to such a situation. The last time such an invitation had been extended was in 1928, to pioneer aviator Bert Hinkler.

White was made Australian of the Year for 1974, but in a typically rebellious fashion, his acceptance speech encouraged Australians to spend the day reflecting on the state of the country. Privately, he was less than enthusiastic about it. In a letter to Marshall Best on 27 January 1974, he wrote: "Something terrible happened to me last week. There is an organisation which chooses an Australian of the Year, who has to appear at an official lunch in Melbourne Town Hall on Australia Day. This year I was picked on as they had run through all the swimmers, tennis players, yachtsmen".

After the death of White's mother in 1963, they moved into a large house, Highbury, in Centennial Park, where they lived for the rest of their lives.

White and Lascaris hosted many dinner parties at Highbury, their Centennial Park home, a leafy part of the Sydney's affluent Eastern Suburbs. In Patrick White, A Life, his biographer David Marr portrays White as a genial host but one who easily fell out with friends.

Patrick_White_house_Centennial_Park.jpg?timestamp=1718311682198)

Patrick White's home Highbury, in Centennial Park, Sydney. Photo: By Sardaka

White supported the conservative, business oriented Liberal Party of Australia until the election of Gough Whitlam's Labor government and, following the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, he became particularly antiroyalist, making a rare appearance on national television to broadcast his views on the matter. White also publicly expressed his admiration for the historian Manning Clark, satirist Barry Humphries, and unionist Jack Mundey.

Marr dismissed ideas of White's Christian faith, which Patricia Morley has considered a weakness in the biography. Greg J Clarke has argued that Christian faith is central to White's fiction, even in the way that White uses apocalyptic imagery in the landscape of his 1957 work, Voss. He personally found it all but impossible to follow Christ's instruction to forgive, which he believed precluded him from becoming a Christian. Even so, in one essay he revealed, "What I am interested in is the relationship between the blundering human being and God."

During the 1970s, White's health began to deteriorate: he had issues with his teeth, his eyesight was failing and he had chronic lung problems. During this time he became more openly political, and commented publicly on current issues. He was among the first group of the Companions of the Order of Australia in 1975 but resigned in June 1976 in protest at the dismissal of the Whitlam government in November 1975 by the Governor-General Sir John Kerr. In 1979, his novel The Twyborn Affair was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, but White requested that it to be removed to give younger writers a chance to win. (The prize was won by Penelope Fitzgerald, who ironically was just four years younger than White.) Soon after, White announced that he had written his last novel, and thenceforth would write only for radio or the stage.

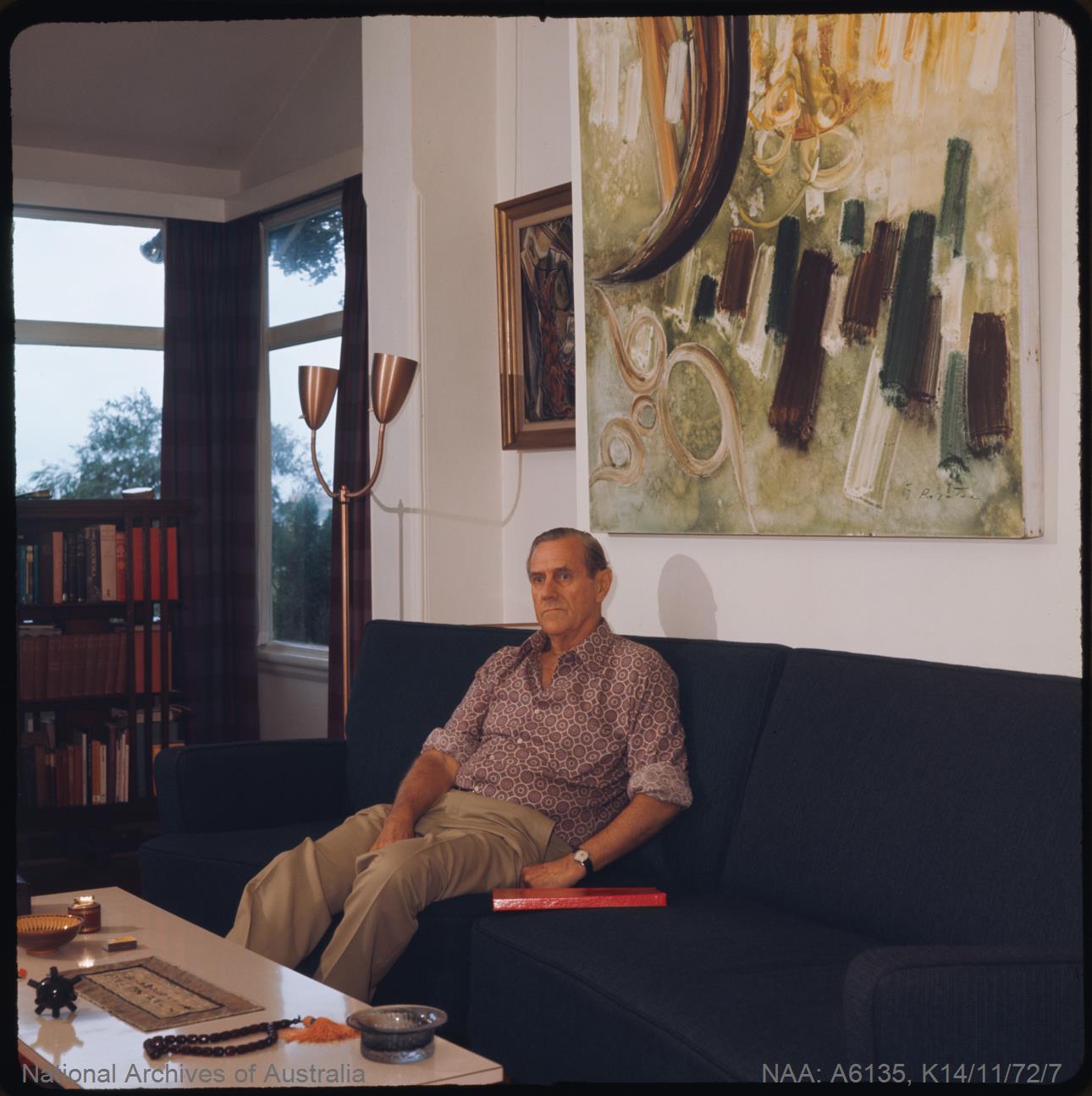

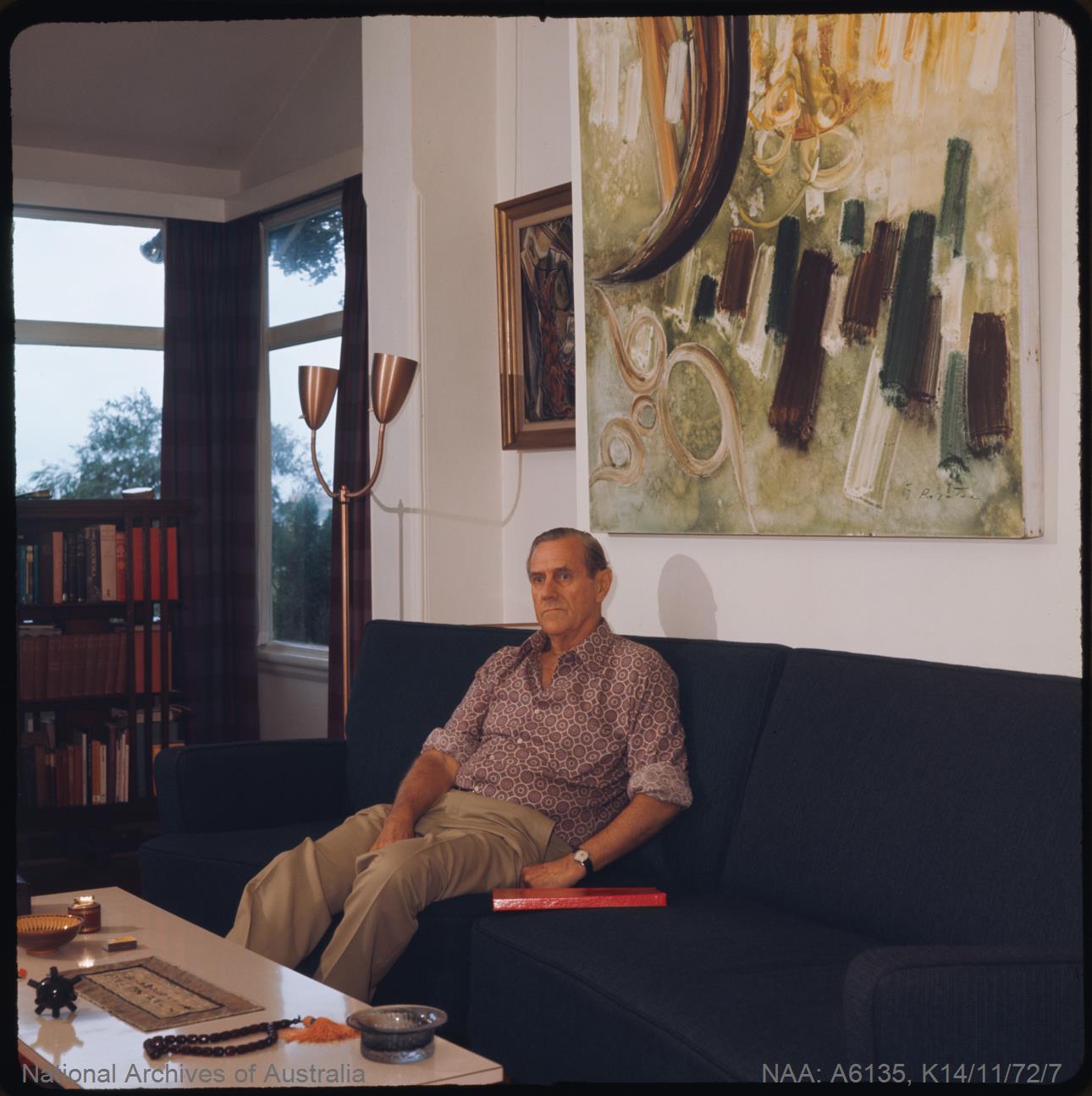

White in 1972. National Archives of Australia image

Director Jim Sharman introduced himself to White while walking down a Sydney street, some time after White had seen a politically loaded stage revue by Sharman, Terror Australis, which had been panned by Sydney newspaper critics. White had written a letter to the editor of a newspaper defending the show. There was a significant difference in their ages, but the two men became friends. Sharman in his theatrical circle, as well as his visual style as a director, inspired White to write a couple of new plays, notably Big Toys with its satirical portrayal of a posh and vulgar upper-class Sydney society. A few years later, Sharman asked White if he could make a film of The Night the Prowler. White agreed and wrote the screenplay for the film.

In 1981, White published his autobiography, Flaws in the Glass: a self-portrait, which explored issues about which he had publicly said little, such as his homosexuality, his dislike of the "subservient" attitude of Australian society towards Britain and the Royal family, and also the distance he had felt from his mother. On Palm Sunday, 1982, White addressed a crowd of 30,000 people, calling for a ban on uranium mining and for the destruction of nuclear weapons.

In 1986 White released one last novel, Memoirs of Many in One, but it was published under the pen name "Alex Xenophon Demirjian Gray" with White named as editor. In the same year, Voss was turned into an opera, with music by Richard Meale and the libretto adapted by David Malouf. White refused to see it when it was first performed at the Adelaide Festival of Arts, because Queen Elizabeth II had been invited, and chose instead to see it later in Sydney. In 1987, White wrote Three Uneasy Pieces, which incorporated his musings on ageing and society's efforts to achieve aesthetic perfection. When David Marr finished his biography of White in July 1990, his subject spent nine days going over the details with him.

White passed away in Sydney on 30 September 1990.

A 2024 review of White's legacy noted that, while a number of places of significance to his life have been afforded heritage protection, his works are less widely known in Australia than might be expected of one of the country's few Nobel Prize winners, even in literary circles.

In 2006 a literary hoax was perpetrated whereby a chapter of his novel The Eye of the Storm was submitted to a dozen Australian publishers under the name Wraith Picket (an anagram of White's name). All of the publishers rejected the manuscript and none recognised it as White's work. All those young writers from the peninsula should take note of this - just because your work has been rejected by a publisher does not mean they know or can recognise good work when they have it placed in their hands.

Write on!

![]()

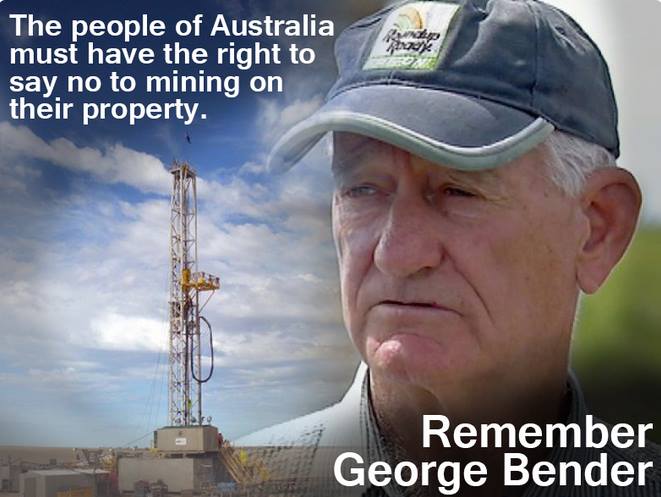

According to the Queensland State Government’s most recent publicly available figures, at least 16,499 coal seam gas wells have been drilled in Queensland, and granted petroleum leases cover at least 3.5 million hectares of the state.

According to the Queensland State Government’s most recent publicly available figures, at least 16,499 coal seam gas wells have been drilled in Queensland, and granted petroleum leases cover at least 3.5 million hectares of the state.

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Patrick_White_house_Castle_Hill-2.jpg?timestamp=1718312104659)

Patrick_White_house_Centennial_Park.jpg?timestamp=1718311682198)

.jpg?timestamp=1719372039384)