July 5 - 18, 2020: Issue 457

Kevin Bruce Murray

Some of our residents retire and then do so many other things it becomes obvious that it's great they did retire so all esle could be done. Sharing skills learned and giving access to others to a whole wide world of wonderful insights has been the focus of one of our Warriewood residents. A Speaker for U3A Kevin has utilised his knowledge of the online world to be among those now offering Talks Online through Zoom, and even developed a Discussion Group using the same technology.

Mr. Murray is also a wonderful writer, an extract from his book 'And Then My Mother Took Me to Hospital' features as the July 2020 Artist of the Month and can also be accessed on his website, in full, in a PDF version: kbmurray.com/Writings. Also featured are some of his wonderful images - Kevin is a great photographer too.

When Kevin was a teacher he was a firm believer in Discovery Learning - a technique of inquiry-based learning considered a constructivist based approach to education. In many ways he could be considered equally a fan of Lifelong learning - the "ongoing, voluntary, and self-motivated" pursuit of knowledge for either personal or professional reasons.

Even now all he does for others not only enhances social inclusion, active citizenship, and personal development, but also self-sustainability.

Mr. Murray is in fact a Renaissance Man - the notion expressed by one of its most-accomplished representatives, Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72), that “a man can do all things if he will.” The ideal embodied the basic tenets of Renaissance humanism, which considered man and woman is limitless in their capacities for development, and led to the notion that men should try to embrace all knowledge and develop their own capacities as fully as possible.

But where did all that begin?

Where and when were you born?

1950 – I was born in Mosman but we very soon after that moved to Seaforth. I’ve spent all of my life on the northern beaches. In 1962 we moved to what was then Harbord, now Freshwater - ‘Freshie’ we used to call it. We were in a red brick house on the corner of Oceanview Road and Charles Street, only 2 minutes from the beach. We spent all of our spare time, when we weren’t at school, on the beaches. My current crop of skin cancers bear witness to our lives on the beach. We had surf-o-planes, we’d go out when the bombora was running.

While we were at Seaforth we’d leave home straight after breakfast and maybe make an appearance for lunch but mostly we’d come home when the sun went down. Mum would say ‘did you have a nice day?’ to which we’d reply ‘oh yeah.’. That was about the limit of what we’d reveal to our mothers.

Where did you go to school?

I went to school firstly at Saint Cecelia’s at Balgowlah. Then in 3rd Class I moved to Marist Brothers in Mosman and then, in the Senior school, I went to Marist Brothers at North Sydney. So I travelled from Harbord to North Sydney every day of my school life and consequently spent a lot of time on the bus.

I was in the second year of the then new Higher school Certificate in 1968. I then went to the University of New South Wales and did a double degree in Science and Education. We were the first year when they combined the degrees – prior to that you had to do a Science degree and then separate to that you’d do an Education Certificate.

I did pretty well in the first year of the newly combined Science/Education course, so for the second year I had to deliver a speech to the new people coming in to tell them how fabulous it was, and that was my first experience of public speaking. I thought ‘this will be a doddle’. Like many universities, the UNSW had the tiers and the front amphitheatre where the lecturers stand – so for my first Public Speaking engagement, with a room filled with around 500 new students all keenly anticipating some insights into what their first year was going to be like, and I just stood out the front and there happened to be a sink with a tap in it at that front section. I just grabbed onto that tap and went on, without any notes, and to this day I have no idea what I said. I was so nervous and so overwhelmed by that situation.

Where did you go to work once you graduated?

In those days, because I was on a Teacher’s Scholarship, you were indentured to the Department and had to go wherever they sent you for the first couple of years. I was fully expecting to be sent to the Back o’ Bourke or somewhere similar, but because I topped my year they actually rang me and offered me the choice of where I wanted to go. I wanted to stay near the beaches and coast and so chose Wyong High School and spent a year there.

I abandoned the curriculum pretty quickly when I discovered that many of the girls at Wyong High were getting pregnant at the age of around 13 to 14 and so I taught the practicalities of Reproductive Biology. I wasn’t much older than the kids I was teaching. I was teaching the HSC students Chemistry and Biology and Physics and most of them were really only 3 or 4 years younger than me. I played drums and rode motorbikes, so I very much identified with them rather than with the stuffy Science Master who actually gave me a very poor report at the end of the year.

How long were you there for?

Only a year. My intention, as it was for many of us in those years, was to work for a year, earn some money, then travel. Then come back, work for a year again, then travel – there was no question of getting jobs then – so that’s what I did: worked, saved and then I did my first overseas trip.

Where did you go?

On my website (kbmurray.com) is a publication of mine called ‘Asia Diaries’ which is based on that first trip in 1974, following in the footsteps of the guy who wrote the ‘Lonely Planet Guide’ – I was only one step behind him. His first guide was Bali and that was my first stop.

Did you experience any culture shock?

It was fantastic. I travelled for about 6 months. The intention was to make my way overland to Europe of course, as everyone did, but the odd war broke out in Thailand and Cambodia, and so it was getting a bit dangerous. I also got very homesick, which surprised me. I was travelling on my own. I had left with a couple of friends, but they went their way and I mine and I ended up on my own. Although you meet a lot of people along the way you don’t have that continuity of relationships, and I missed Glenys, my then-girlfriend, and so decided to come home and live a more “sedentary” life for a while.

What did you do when you came home?

I didn’t really want to go back in to High School Teaching – I didn’t find that a very rewarding experience, mainly due to the attitudes of the other teachers and the constant discipline issues. As I was trained in Education and Science I applied for a few things and got an interview with TAFE. I must have impressed them in the interview because they decided to pay off my bond to the Education Department– as at that stage TAFE and the Education Department were separate.

They employed me as a teacher in TAFE and I was to spend the rest of my educational career in TAFE.

Where did you commence?

I started off teaching in a condemned building in Sussex street, where, prior to us being there and ever since the Depression, homeless people had used it as a flophouse or would come and get fed. Every so often, while I was teaching there, some old guy would wander through the door with the memory of it being a flophouse.

Sussex Street TAFE

The whole place was condemned as a fire hazard and yet we did science experiments involving volatile chemicals and Bunsen Burners. They also discovered a high incidence of birth defects in teachers and students who had attended there. A team was sent in to investigate and found a high level of mercury embedded in all the floorboards and cracks everywhere. It was closed down shortly afterwards and cleared of this, as well as building fire escapes, and then it was reopened.

One of the stories in my book (titled “And Then My Mum Took Me To Hospital” and accessed via my website - kbmurray.com) is called ‘The Sussex Street Volcano’ and this relates to one incident there. When you’re a Science Teacher you’re given a book listing all the science experiments you’re not supposed to do- and of course, as Science Teachers we went through the book and diligently did all of those, one of which was the infamous volcano.

Many people may recall from their school years a bit of iodine mixed in with some potassium permanganate forms a big volcano. We liked to embellish it a bit; we’d add bits of a metallic substances and magnesium and whatever else inside it so that as it exploded it did so with a bit more theatrical vigour. The story relates how on one memorable occasion a big blob of molten metal flew out of the middle of it, fortunately not hitting any of my students who were all standing around it at the time, and landed in the very space where there wasn’t a student. Not only did I think ‘phew’, I then saw it commence burning through the floor and knew we had to warn those below – we were on the first floor of this building in Sussex Street. There was a class being taught below and so I very calmly sent one of our students down to let the teacher know there might be this molten blob of metal coming through their ceiling imminently.

She disappeared and about five minutes later reappeared – ‘did you tell them?’ I asked – ‘No. no, no – I just stood there waiting for him to ask me what I wanted.’

Fortunately it didn’t burn through – and luckily I didn’t get fired.

How long were you at Sussex Street?

I was there for 4 or 5 years, mainly as a Biology Teacher, as well as teaching some other science as well.

I was then transferred to the Kensington campus at Randwick Tech. That was fantastic as they had a really active Science faculty where I got to teach a wider range of Sciences to a wider range of students, and because it was so close to the university we had some great access to really good equipment.

I was there for almost two years and then at the end of that second year I lost my voice. I had what they call a granuloma on the vocal chords. This is a very common complaint that teachers get. When we were doing our studies, learning how to project your voice didn’t form part of what you were taught at Teacher’s College. Obviously I was abusing my vocal chords and I later learnt our family has a history vocal problems – so there was a bit of genetics involved as well.

Losing my voice taught me a lot about myself and about being disabled and about how people treat disabled people. However, the last few months of my teaching at Randwick was also some of the best teaching I ever did. Because I couldn’t talk very much I gave the students topics and then they did the lessons which consequently allowed or induced them to go into these topics in depth. Nothing enables you to learn better than having to teach it.

This method proved very successful and was something I carried on and developed later into my career, embracing a philosophy called ‘Discovery Learning’. Discovery Learning is where the students determine the speed, the pace and the direction of their learning and the teacher is there to guide them along their individual learning pathways rather than being the repository of knowledge and the determinant of progress.

At the time I didn’t know if I was going to get my voice back or whether I would remain silent for the rest of my life. There are a few little experiences I’ve related in my book as to how people treated me during that time. One instance I’ll share concerns a family get together over Christmas when I first lost my voice. Everyone was sitting around cracking jokes with family, as you do, and I’d think of something clever to say, to add to the conversation and subject being discussed, but couldn’t say it and so would write it down. By the time I’d written it and passed it to the next person the conversation had moved on – people would just look at you as though you were an idiot, simply because you just couldn’t keep up the conversational pace. So, it taught me an awful lot.

How long did that go on for?

About six to twelve months. I had an operation, and then vocal training, but there was no way I could go back into a classroom.

The only thing could do with me was redeploy me elsewhere. They had an External Studies arm based in Redfern. They put me there, as it was where they put a lot of the people that were “misfits” who couldn’t fit into the system as it was designed around the process of classroom instruction.

Luckily I took to it as a duck takes to water – Distance Learning to me was just brilliant. It was very student focused, I could prepare all the learning materials – and as there was no teacher there for the student I could design all the learning materials and course structure to suit them. I ended up being in charge of producing all the distance learning materials for all of TAFE. I did a further degree in Instructional Design and then ended up teaching Instructional Design for TAFE teachers and school teachers.

I just loved it because it was organised, it was structured, student-centred, and it could deal with people who had difficulty getting to classrooms; mothers, people who worked, a big rural contingent – it enabled them all to access learning materials in a format that enabled them to learn. We had forty five thousand students in those days and only a couple of dozen teachers looking after all of them. So we relied a lot on our learning materials and of course, this was in the beginnings of the Internet as well. A lot of the Online Teaching you see now, we were the pioneers of that.

So I stayed with what was originally called External Studies, then it became the Open Training Education Network, called ‘OTEN’, which was then moved to Strathfield, and I became the Education Planning Manager for both schools and TAFE. This gave me a lot of leeway to change things, to change a lot of the curriculums. And even impact the very philosophy of distance education. For instance, I wrote ‘The Basic Methods of External Teaching’, a manual which they still use to this day.

I also lost my voice again during this time, about 10 years after the first incident – so it was very clear to me I couldn’t do any lecturing or face to face teaching and so was in the right place by accident and that worked out very very well indeed nonetheless.

How long were you doing all this?

I started teaching in 1976 and left the Department in 2004.

While on the writing – if you have been journaling since your first visit to Bali, and ever since – where does that will to put it down in writing come from?

I actually wish I’d started as a much younger person – I’m writing a daily diary now but my life is nowhere as near as adventurous as it was in those younger days. But every overseas trip we did, and for a lot of our domestic trips, I kept very detailed diaries mostly with the intention of sending these home. So those early Asia diaries were actually letters home to Glenys and my family. A lot of these were written on the old very thin Aerogrammes. Glenys had kept these and I could use these as the basis of my ‘Asia Diaries’ book.

From then on I used to write travel dairies and then when we’d get access to the internet, which was very rare in those early days, I’d do a summary and send that home just to let people knew where we were and what we were doing.

So you left the Education Department in 2004?

Yes, I was only 53 when I retired. I had lived through 11 major restructures of TAFE by then – TAFE was a government department that subsequent governments loved to fiddle with. I survived 11 restructures – and a restructure in TAFE never reaches an end – it starts off with the changing of the headers of all the memos and the names of the departments and you have all these meetings with the new minister and they draw up a plan and commence implementing that plan. By the time they just start to implement that plan the incumbents are thrown out, another new minister comes in, and they commence their own restructure. It is never-ending. It is so disruptive, and so convoluted. For example I was employed as a teacher and never became a Head Teacher as by then they had discovered I was reasonably good at management but the only way to get me into management was to designate me as acting in management roles. So for most of my TAFE career I was an actor, not just in one role, but at times, in several roles. I recall one period where I was ‘acting’ in three roles all at the same time – I was managing a warehouse, and the learning materials development and also Education Planning Manager. Each of those roles should have been take by a Senior Manager, but because the restructures never finished you never got to apply for those jobs, you always just ‘acted’ in them.

When, in 2004, they announced a twelfth restructure, and actually offered us redundancies at that stage, I took it. I could see the writing on the wall; they were privatising TAFE, had all those private organisations running out of garages making money left, right and centre, and NOT delivering the kind of education that I thought was needed. There was very little I could do in my position to address that so I took the redundancy.

What did you do then?

At aged 53 I decided to start my own business ventures and did a lot of consultancy work in education. I’d earn more in an hour than I’d earn in TAFE. I travelled around a bit, particularly to different education institutions showing them how to develop education resources, and as we were well into the Internet age by then, I was helping them transfer over to Online Learning.

The other major business I started was my own consultancy business which I called QED - and acronym for "quod erat demonstrandum", literally meaning "what was to be shown", used when proving a theorem in maths or science. One of the major pursuits of that business was the recording and online publishing of Oral Histories. This enabled me to pursue an old love of mine - History, but particularly personal histories. I’m not too interested in kings and queens and wars and so forth, I’m much more interested in how people lived their lives.

So I started recording people’s lives. A lot of things came out of that but one of the main ones was I was employed by Baulkham Hills Shire Council – we did around 100 Oral Histories for them, interviewing present and past residents of the Hills District. You can access these Oral Histories through my website (kbmurray.com) or just by searching for “Hills Voices Online”. The way we approached this was we recorded the Oral Histories with a whole bunch of questions, we took photographs and scanned photographs that they brought to the interview, we then transcribed the interviews so we had a word-for-word transcription of the interview and then we placed the audio, the pictures and the transcriptions on the Internet so you could hear them speaking and read the transcript and of course, these were fully searchable.

So if, for example, you wanted to hear about the 1938 fires in the Baulkham Hills Shire you would stick in ‘fires, 1938’ and up would come all those people who had talked about those fires and their different experiences of that. That contract with Baulkham Hills went on for around 10 years.

What struck you most about doing these – people using phrases now no longer in use, the change in the landscape, or what?

With the Baulkham Hills Shire project there was a clear purpose – they wanted to archive the history of the area; so that was fairly straightforward, the questions were all simple; ‘where did you grow up’, ‘what was the suburb like at the time’, ‘what do you remember about your neighbours?’ – those kinds of questions.

I combined these with another love of mine, which is doing virtual tours. I was one of the innovators of doing virtual tours; in fact, before they became popular on the internet, as they are these days. I remember going to a Real Estate agent in town trying to interest them in doing virtual tours to sell properties as I could see then what it could do and offer them. I went along with my little Macintosh computer and was surrounded by this room full of men in suits and gave them a presentation of a virtual tour of my house that I’d done and suggested to them that this might be the future of online Real Estate. They didn’t see it and it never went anywhere, unfortunately. About five years later such virtual tours of houses started appearing all over the internet and now it’s the way places are found and sold to buyers.

I did virtual tours for Baulkham Hills Council as well and put these online as well. We went to all the heritage buildings in the area, went through each room taking 360 degree photographs. We inserted links to the Oral Histories with people speaking about the rooms and what they recall about them – and this worked out well.

We’d interview, for example, Clive Roughley, who was the great grandson of the person who built Roughley House in Castle Hill. Clive was an old man even at that time – we’d show him photographs of each room and ask him to just tell us about what his memories were of each room.

We’d use that same technique for a lot of the other interviews. We’d ask people to collect around 10 photos that had meaning to them or reflected some story of their lives - and because we’d publish them on the web, the photos were very important as triggers for the conversation.

Apart from the Baulkham Hills Council work I also did oral histories and virtual tours for private individuals.

For example, I interviewed several people about their experiences in WWII. I remember one was a couple who did a combined interview – they had met during the war and married, had lived in England and then moved to Australia afterwards. This interview was just their stories from the war years.

Another couple I did were in their 80’s who wanted to leave their video story for their grandchildren They wanted it to be shown at their funerals as if they were giving their own eulogy.

They came from Holland in the 1950’s, so had been through WWII in Holland as children and all that entailed; no shoes, no food, no money. When they had tried to share those stories with their grandchildren they just weren’t interested, or were not ready yet. So they wanted to capture that so it would be there for them later on.

I did quite a few of those.

One of the Oral Histories I did was with my own mother, years ago now. She has since passed away. That’s the vital thing about Oral Histories – capture it while you can, before dementia may set in, or before they die. Mum spoke about her early life – she grew up in Fairlight. This is something I will treasure always.

Mum with her brother Don at Woy Woy in 1932

What was her maiden name?

She was Dorothy Ferguson. They grew up overlooking Forty Baskets Beach at Fairlight. Her life was even more adventurous than mine in many respects; they built canoes out of old corrugated iron sheeting and paddled around North Head – in fact her life was freedom personified, and that’s how she raised us. My father was fairly absent, as most fathers were during that era – always working at a job to pay to raise a family.

Glenys – how did you meet Glenys?

I met her on a blind date. A friend of mine who lived next door to us at Harbord was dating Glenys at the time but he met someone that he liked more. As he didn’t want to hurt Glenys’ feelings he thought he’d set her up with me, his best friend, as he knew we’d probably get on well together.

His courting of the other girl only lasted about a month.

Glenys and I have been together ever since.

Interestingly, where we live now, which is on the northern hillside of Warriewood, the view we had when we first moved here included being able to see the Warriewood Drive-In theatre and that was where we met – that was our first date.

When did you buy a place in Warriewood?

When I first came back from overseas, having decided I wanted to spend the rest of my life with Glenys, we lived in Dee Why for a little while in a unit, then in a tiny rented cottage on a strawberry farm in Terrey Hills. We then decided we wanted somewhere more permanent to live and moved in here in 1977.

What changes have you seen in the Warriewood valley during that time?

I’ve documented a lot of that, because I’m a photographer and because I like documenting things as they are - which eventually becomes as they were. Doing the Oral Histories I realised that people don’t get how important this is – it’s like the boiled frog, you don’t know that the temperature is changing while you’re being boiled – we don’t realise that we’re all living in history and particularly these days, we’re all living in a time of pretty dramatic history, and just don’t know it because we’re in the middle of it.

So one of the reasons I like taking photographs is so that in 10, 20 or 100 years time there will be a record of it – I know this because of how valuable those photographic records were for the people we interviewed.

Consequently I’ve taken lots of photographs of the Warriewood valley and the coastline with the intention to at least have a record of these changes kept somewhere.

When we first moved in here there were sheep and horses and the cows. There was a horse-riding school down where McDonalds currently is – there was one little corner shop run by people named ‘Wright’ on Warriewood Road – and that was it, for the whole valley. You can still see where that little shop was.

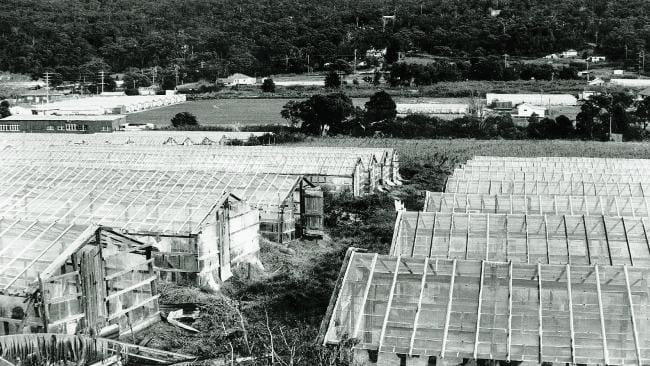

There were very few houses in the valley, most of it was glasshouses and farmland that flooded. The year we moved in the whole valley flooded – so our outlook was basically a lake – the whole of the Warriewood Valley was flooded.

They have since drained part of the swamp and built weirs so it doesn’t flood so much but every now and then you will get the hint of what was clearly an obvious water thoroughfare area, in its landscape, through the inundations that occur after lots of or prolonged periods of rain.

The most obvious change is the loss of the glasshouses – there’s still a few remnants of them and I’ve photographed them – but the valley was full of these and was referred to as ‘the valley of glass’ or something similar. One of the reasons for this is because it’s a kind of little heat sink here so the vegetables, particularly tomatoes, would ripen here about 2 weeks prior to ripening anywhere else in Sydney. So they could get them to the market and get the high prices first.

Our home has been left fairly much as how it was when we bought – the old fibro and weatherboard clad era. It appears to have been built in the early 1940’s. When you go up in the roof there’s about three layers of ceiling – there’s one with a little chimney in it, then a corrugated-fibro roof and then a metal tiled roof atop that – so three eras at least there. We bought the house from Frank Adshead who was a prolific letter-writer for the Manly Daily, and it had 2 or 3 owners prior to the Adshead family – It was built in the early 1940’s, so it was one of the original places in the valley.

Warriewood glasshouses 1978

Our Warriewood view in 1978

Development in Warriewood Valley - photo taken August 24th, 2003

Clearing land in Warriewood, 2005

What are the most dramatic changes between then and now in Warriewood?

Well, a lot more houses, a lot more noise – and crowded roads. One of my pet peeves is the desire for continuous population growth based on the capitalist philosophy of growth at all costs. It is just a nightmare. I find we are reaching the point where we need to pause, to stop, to appreciate what we already have and not constantly strive for something that we can never achieve. That is the capitalist way; it’s all based on promises of a better future which of course never arrives.

Could you share some insights into writing your book?

I wrote and self-published my book (And Then My Mum Took Me To Hospital) in 2005. It contains 25 short stories from my childhood and early adult years. In many of these stories I ended up with some form of injury, hence the origin of the title. After I had written my book I was asked to not only give talks on what it was about but also on the process of writing a book. I had one of my stories published in “Seniors Stories” that the NSW Government puts out each year. They asked me to give a speech at its launch at Parliament House. Most of that short speech was about the process of writing and my ‘process’ is to not pay too much attention to all the nuances of correct grammar, and all the conventional “rules” of writing. I find they just inhibit you.

I had written a list of all sorts of memories that I had jotted down over the years, because I suspected I would eventually lose my memory. So I wanted to have things that would trigger those memories – these could just be a sentence or even just a word. Something that would remind me. So I would just grab some of those sentences and start writing the story that surrounds them – and the details just poured out, it proved to be a relatively easy process.

Some of those memories on that ever-growing list have less to do with events in my life and more to do with the evolution of my thoughts on everything from the evils of capitalism to the meaning of life. From the non-existence of gods to debates about Fate and the limitations of the scientific method. I have amplified many of these thoughts into a series of essays that I continue to write and collate into a living document I call “Snap-Thoughts”… because they are really like snapshots of my mind. These, like most of my writings can be accessed via my website (kbmurray.com).

You are also giving Talks – who are they to?

Anyone who will listen! (laughs)

I do lots of Probus talks. I also do a lot of Talks for U3A, the University of the Third Age, which I find particularly satisfying – as the audience is usually there to learn something, which of course appeals to the teacher in me. I’ve been doing these talks for U3A since about 2016 and was averaging over 30 a year – I’ve also made these Science Talks on varying subjects available online as PDFs as well. As with much of my writings, these can be easily accessed through my website (kbmurray.com).

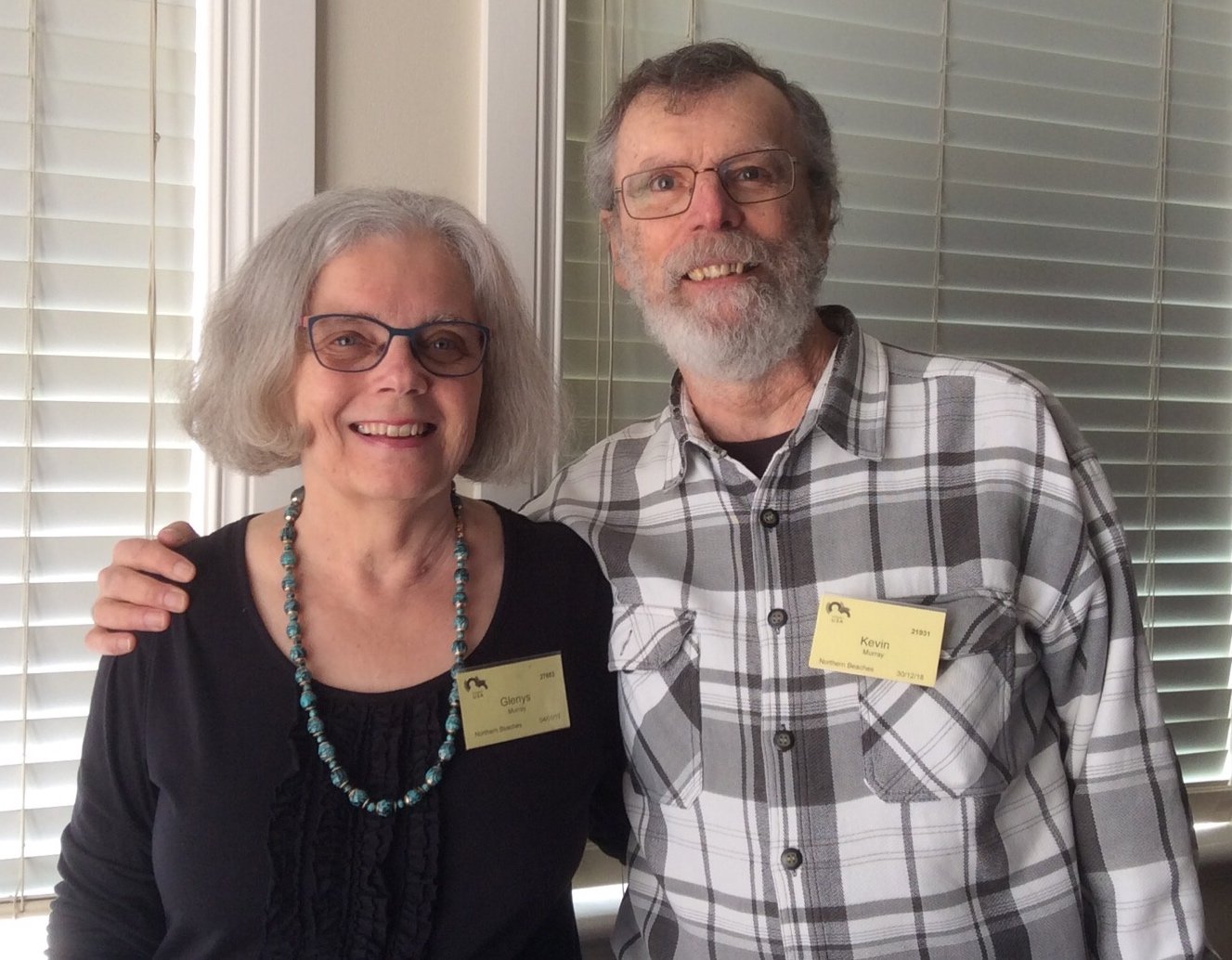

Talking with Probus Group

Some of the talks I do with my wife on our travels – we have travelled quite extensively and been to places others may not have insights of. It’s interesting that when we give talks on our travels I’ll ask people how many have been to Alaska – and half or more will put their hands up. But what they have been on is a gigantic cruise ship with known ports of call and being funnelled this way or that – they haven’t been off that tour track.

Kevin and Glenys Presenting

Some of our travels have been quite adventurous – particularly to Mongolia, Siberia, Alaska, Western China or South America. One instance we speak about would be when we went up into the Altai region of Siberia and walked to a glacier – we would have been up over 2500 metres and so very heady due to the low oxygen. We were so excited to get there, and then we heard this rumbling noise on the path behind us – the same track we’d used to get there. We looked back behind us just in time to see these giant boulders sliding down the mountainside onto the very path where we had been two minutes earlier – this was still a geologically active region and you could feel it shaking all the time. We should have got the hint as the sides of the mountains were all scree slopes and knew all those boulders we’d passed must have come from somewhere. To get there we were transported in an old Russian six-wheel drive truck – I have a little video that I can show people as part of the talk – we were all in the back of this truck in the snow like cattle.

Russian Truck

Alaska Glacier Bay

Alaska - Bald Eagle

I was very fortunate to have a friend who organised such trips for his job – so he would go on these routes for the first time to check them out and we would go along with him just to explore the regions and ended up going to places that you would never go back to, but of course the unknown element of these made the trips so much more interesting. That Trans-Siberian railway journey, though, was just beautiful though, just a wonderful experience.

Something that has developed out of the U3A Talks is Discussion Groups where a bunch of around 20 of us will discuss the contemporary issues of the day.

We used to do these once a fortnight and even during the Covid-19 lockdowns we were able to continue doing these weekly via Zoom. These have proved really valuable for people who have been isolated or locked away to have that connection and be able to discuss the latest excesses of government or whatever is on their minds.

The Discussion Groups are quite planned – we discuss local issues, such as the privatisation of our local buses or the hospitals – but we also discuss international news: North Korea, or what’s happening in Great Britain or the US, so a wide range of stuff – and this has proved to be just such a wonderful outlet for people.

It’s been a really important part of my life to enable people to do that – to have that connection, to not be isolated, to be able to discuss what is affecting them at a local level and comment on what else is happening. Every week we can keep up with the news and have some contact with each other.

During the Covid era I have also been delivering my Science presentations online via Zoom and these too are providing people with contact and something there specifically of interest to them. When I did the face to face Talks at Newport for U3A, or wherever, we’d have up to 120 people in the audience – we’re still getting 60+ people for the online ones. I love being able to do that for others.

You were a drummer when younger and still involved in music?

Yes. I’ve been involved in music in several ways. After I retired I was a drummer in a local band called ‘Loosely Woven’ run by Wayne Richmond. We were in that for about 8 years – Glenys was a singer and I was a music composer and drummer.

Playing drums in Loosely Woven

I wrote my music compositions on my computer at home. I would be inspired by snippets of musical phrases or ideas or themes, and I’d produce them in midi form, and the only people that would get to hear them would be Glenys and our cat. I had this repository of about 20 or 30 songs and tunes that I had written over the years, many of which were on environmental themes. When Loosely Woven came into our lives I thought this may be an opportunity to spread them further than Glenys and the cat. I very nervously gave a couple of these tunes to Wayne, who is a brilliant musician, and he was able to arrange them for his group to perform.

I remember being so nervous the first time they performed one of my songs – called ‘Leaving You’. It was sung by a woman who had just got a divorce – so she had the meaning of the tune down pat and had the whole audience almost in tears by the end of it. I was so nervous when the song started, and so pleased when it finished – it received the reaction I had imagined when sitting at my computer writing it.

There is also a choir that Glenys is involved in now called ‘’Cantiamo’’ – an acapella choir, and they perform all around the northern beaches at retirement villages and entertain the residents. Since Covid-19 happened we started up an online form of this called ‘’Singing Together While Apart’’. I’ve been recording each of them in their homes, sometimes via Zoom if it’s video, or they record their own audio and send it back to me. I then put it all together into a format like so many you may have seen with all the people onscreen at once and all singing together. Consequently Cantiamo have kept their Wednesday morning sessions alive even while they’ve been isolated – so it’s been very good to be able to do that for them.

There is a clear thread through these stories of doing something Creative while also being immersed in the Technical – have you ever experienced that ‘shift’ so many describe when they change from doing one to the other?

Not at all – I hate that idea of a clash of cultures – I think it’s wrong and it’s never been right. My greatest heroes have been people like Galileo or Leonardo daVinci who would in one moment be drawing the Mona Lisa and in the next designing submarines. They saw no difference whatsoever and I see no difference either. It may sound pretentious but I think the idea of the Renaissance Man is a term that recognises that both can be done at once. When I was in TAFE and we’d go off to these conferences or management seminars and we’d do all these tests like Myers-Briggs, with an old-fashioned model where they’d divide you into four quadrants of the brain with the Artistic Creative side and then the obverse “Accountant” side – my graph would often come out as a square shape, equal in all four quadrants.

When I’m working on my midi programs on the computer I don’t know whether you’d describe that as Technical or Creative – to me it’s the same thing. Designing a webpage is a creative exercise that requires a lot of technical expertise. To me there is no distinction.

Speaking of webpages, I do have a personal website where you can read many of my writings and hear much of my music compositions. There are also links there to my virtual tours and Oral Histories… and even my numerous photographs. It’s web address is “kbmurray.com”.

What are your favourite places in Pittwater and why?

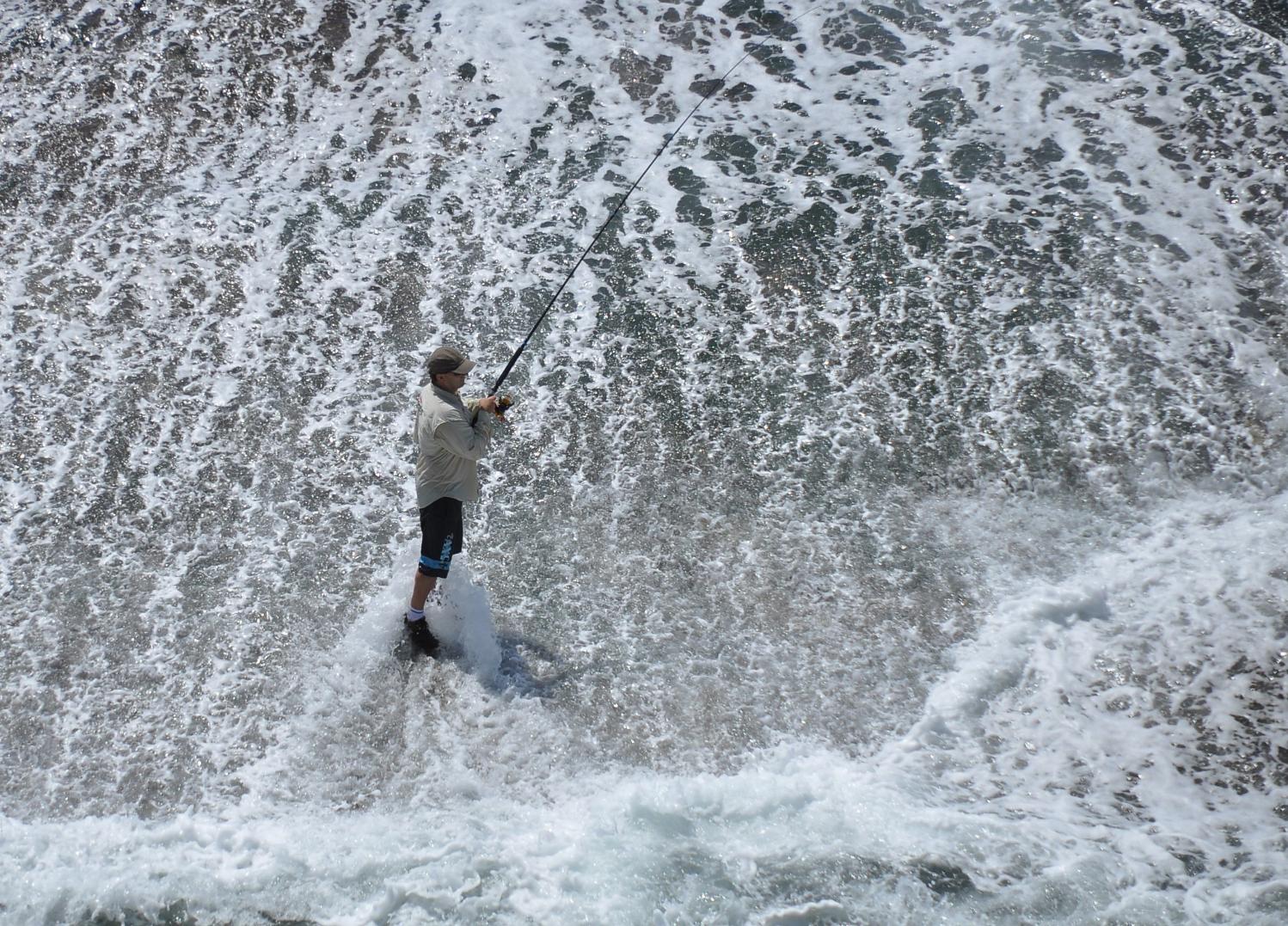

I just love that walk around Long Reef - I just love the view from that headland there, or any of the Northern Beaches headlands really. In fact most of my photos of this area are taken from headlands. I took one just last week from the Warriewood headland looking north and you can just see Terrigal right in the distance – it’s a misty morning shot with the mist just allowing the tops of the headlands to be revealed. Just superb.

I would be hard pressed to name a favourite place as I sailed for years from Palm Beach and when doing that visited every bay on Pittwater and they’re all beautiful. I loved being on Pittwater, loved seeing it all from the water.

I used to run a bushwalking group called “The Stragglers” and we wandered all over the Pittwater bushland, taking photos as we went. We encountered many breathtaking views, but if forced to nominate one – the end of the Bairne Track which you enter from the West Head road. From this promontory you have The Basin on one side and Scotland Island in front of you – that view is just so spectacular.

Stragglers bushwalking group, The Basin

View from Bairne Track Lookout

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase that you try to live by?

One of the very first songs I wrote is called ‘The answer is there is no answer’. I wouldn’t say that is my favourite phrase but it is one that encapsulates the idea that as a Scientist we never say ‘we know’ – we always say ‘the evidence shows’. To us that is the answer as it’s not actually an answer, it’s a question. A Scientist always lives on the very edge of knowledge which means, yes, we’ve learnt an awful lot - but all that has really taught us is how to ask the next question.

Another “motto” which I attribute to a friend of mine but which resonated with me is “All one needs in life is a project, someone to love and someone to love you”. I guess that once your basic needs are met then this is all you really need for a fulfilling life.

Certainly worth thinking about!

A Sample Of Kevin's Photographs

Long Reef - photo by Kevin Murray

Long Reef Rock Fisherman - photo by Kevin Murray

Seagull - photo by Kevin Murray

Looking south from North Narrabeen - photo by Kevin Murray

North Narrabeen Pool - photo by Kevin Murray

Cockatoo - photo by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale shorebreak - photo by Kevin Murray

Misty view north from Warriewood Headland - photo by Kevin Murray

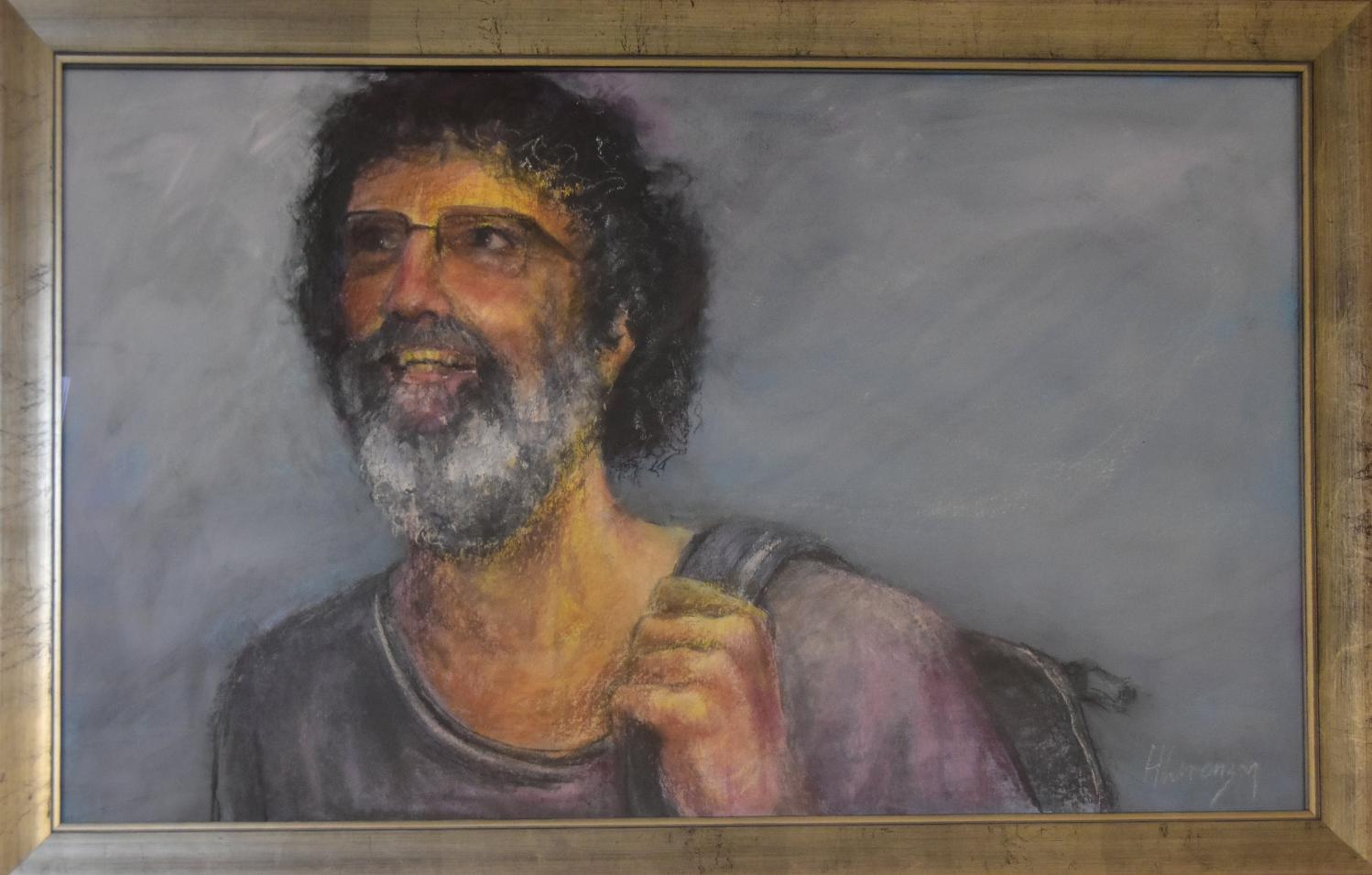

Kevin - painting by his cousin

All photographs this page by Kevin Murray