May 29 - June 4, 2022: Issue 540

The Krill Seekers: How Nuyina Is Revolutionising Antarctic Research

Scientists and engineers at AAD have designed and built equipment that has revolutionised not only the capture of live Antarctic krill in the Southern Ocean, but also world-leading research in a krill aquarium.

The project has been more than a decade in the making, fuelled by determination to understand a keystone species on our planet.

In 2012, krill biologist Rob King and the crew of icebreaker Aurora Australis found themselves stuck in thick sea ice.

Mr King’s team was on a mission to collect krill but they faced an obvious problem – how to reach the swarm beneath the frozen surface.

“It was just too difficult,” Mr King said.

“A whale punched a hole in the ice next to us and was breathing through it. It was having a wonderful time sucking up all of these krill that were under the sea ice.”

“I was sitting there thinking we’ve really got to be able to do something about this.”

The team tested a fish pump used in the prawn industry, bringing a handful of krill to the surface.

It encouraged Mr King to pursue a new idea.

Wishing well

A year later the team tested the pump again, this time through a ‘moon pool’ on board a different ship in the Weddell Sea.

“We caught two or three thousand krill larvae on that voyage,” Mr King said.

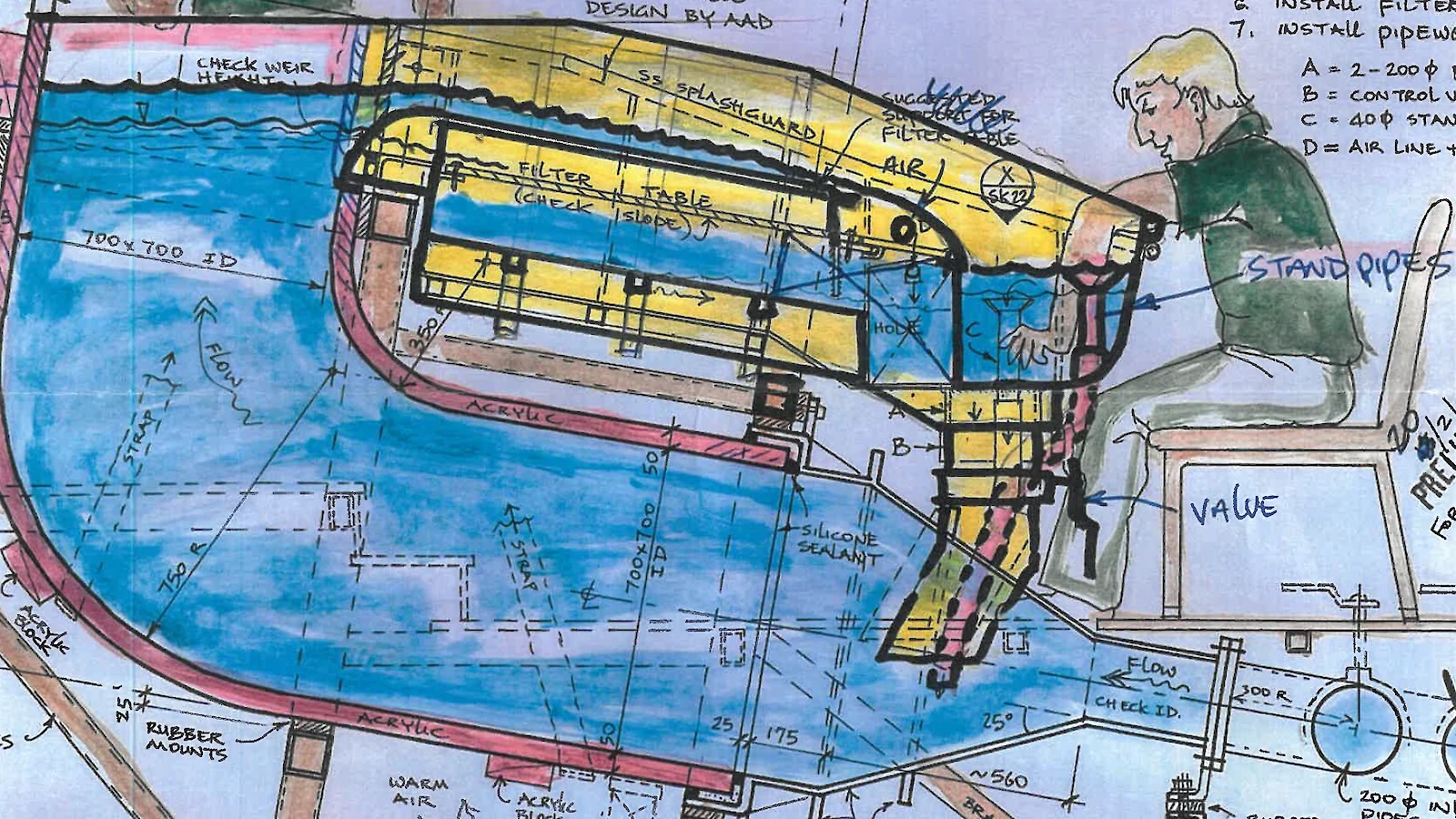

It backed his vision to install a ‘wet well’ on Australia’s future new icebreaker, then in early design stages.

The technology would use pipes to gently vacuum small sea life into the ship without causing harm to fragile organisms.

“It really was the key finding that enabled me to propose to the executive that we should put a wet well on our next icebreaker.”

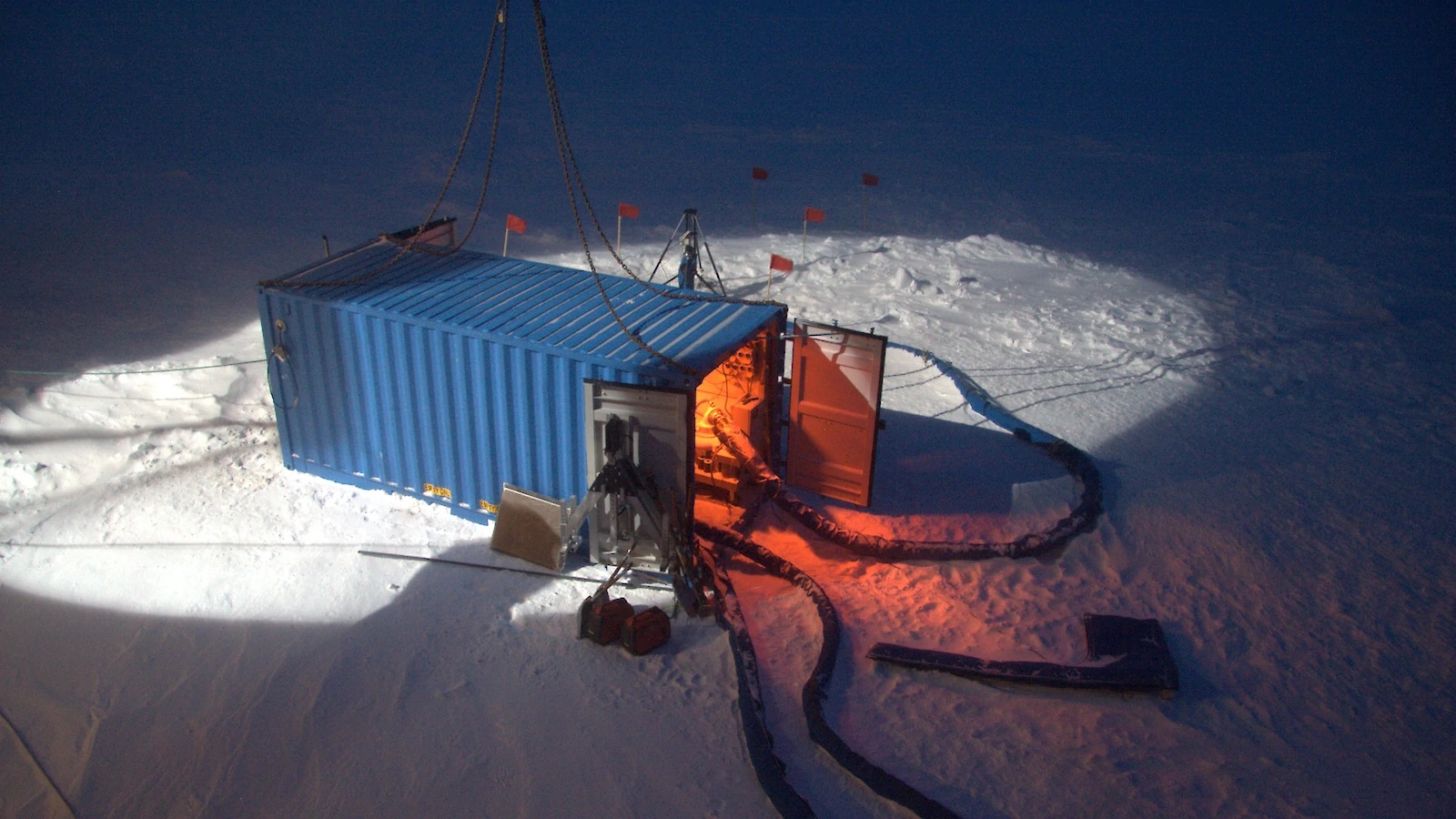

The krill pump on the SIPEX II voyage in 2012 Photo: Kym Newberry

Buckets and a lot of exercise

Early efforts to collect krill on RV Aurora Australis were basic.

“We used to haul them out of the ocean with a big trawl net,” Mr King said.

“Then they’d go into the aquarium tanks, and then you’d manually chill the water in a blast freezer in drums.”

Krill had to be moved in buckets as did replacing aquarium water until upgrades were installed.

“Carting water manually around the ship was literally just chains of people. There would be many people the first day and it would start to diminish each day after that because everyone would get really quite sick of it.”

The wet well would change all that.

An illustration of the wet well Photo: AAD

Here comes Nuyina

The technology formed part of Australia’s new $528 million icebreaker, RSV Nuyina.

The ship’s first voyage to the Southern Ocean was scheduled for December 2021.

Mr King was excited…and nervous.

“There was an awful lot riding on it because if you push a wheelbarrow for 10 years and at the end there’s just a pile of ‘didn’t work’, that’s no fun at all,” he said.

Early tests in the Hobart harbour collecting crustaceans gave the team confidence for the challenge ahead.

Nuyina's maiden voyage south in December Photo: Pete Harmsen

Krill country

Once in Antarctic waters, Mr King’s team began rising earlier each day with the hope of catching krill during their morning feed.

At 5am on January 2 2022, they hit the jackpot.

“We opened up the wet well and almost instantaneously live Antarctic krill appeared in front of us.”

“It was pretty much a grand final winning goal moment, it really was. A lot of hooting and lots of fun.”

“And the next day when we ran it again we went through a surface swarm, and it literally was just as you’d dream a system like this could be.”

Anton Rocconi and Rob King get to work in the wet well Photo: Pete Harmsen

Kick the bucket

Mr King was also looking for a better way to transport krill on the return journey to Hobart.

“The solution in my mind was to not have buckets and tanks anymore but to have a whole aquarium in a container, meaning you could put the container on board configured already.”

A containerised aquarium was built into the ship’s design and proved hugely successfully in maintaining the live specimens.

Once in Hobart, the big blue container was effortlessly loaded from the ship onto a truck and brought to the Australian Antarctic Division headquarters in Kingston.

The containerised aquarium arriving on Nuyina Photo: Mark Horstman

So what’s the catch?

An estimated 10,000 Antarctic krill were collected on the voyage.

Roughly 95 percent survived the trip back to the lab, compared to just 10 percent before the wet well.

“It really has revolutionised how we can work,” Mr King said.

“Those krill now will become the backbone of our breeding program going forward.”

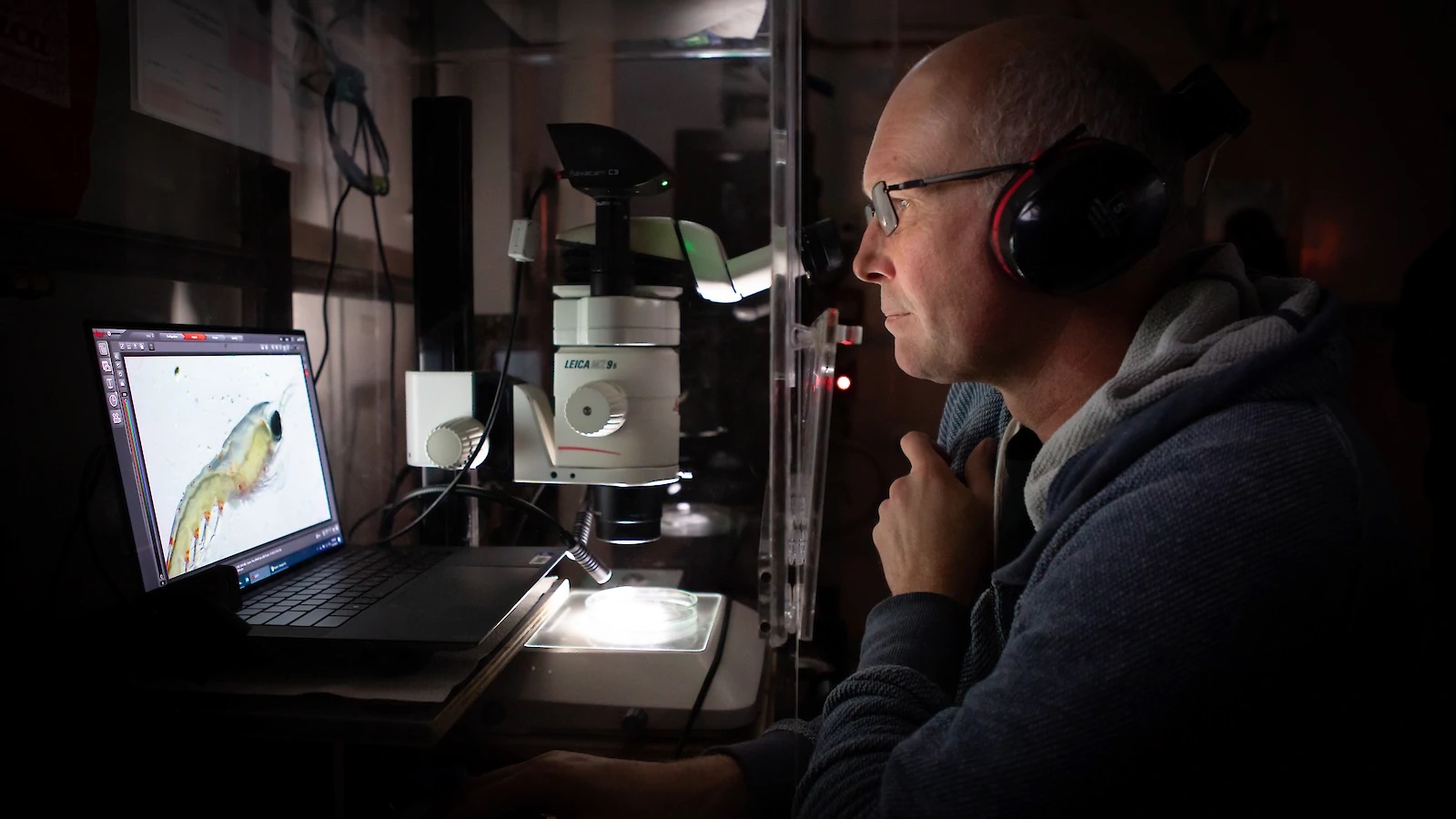

Examining the catch on board Nuyina Photo: Pete Harmsen

Enter the krill keeper

The AAD operates the only research facility for captive Antarctic krill in the world.

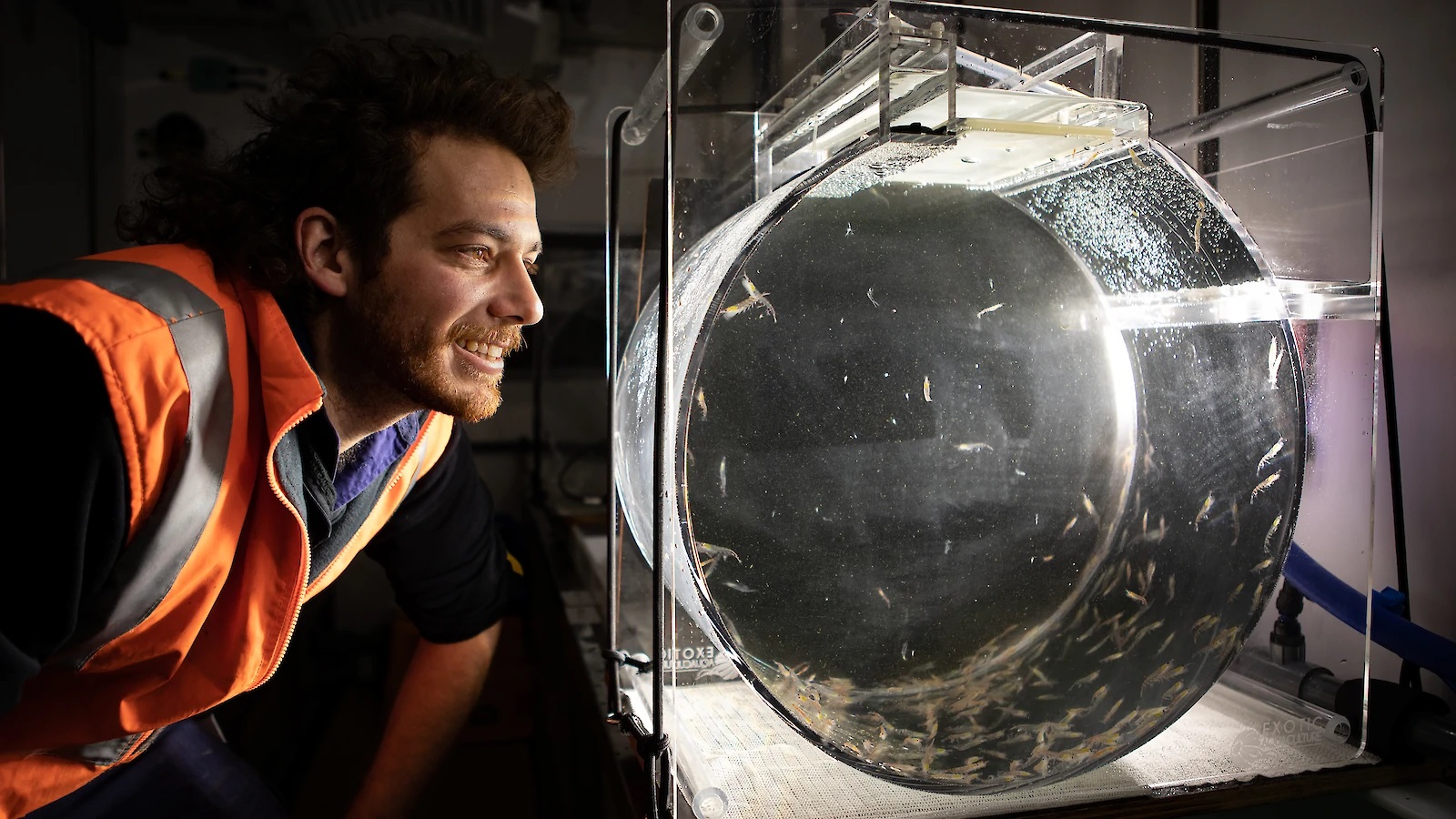

Caring for Kingston’s 10,000 new residents is aquarium technician Anton Rocconi.

“They’ve been doing really well,” Mr Rocconi said.

“Lots of our juveniles and larvae have continued to develop and they look really good.”

“And not long after we returned the handful of adults we did catch actually spawned and we’re raising those eggs and larvae in captivity as well.”

A happy scientist: krill keeper Anton Rocconi Photo: Pete Harmsen

The krill calendar

The year ahead will see the team meet the challenges of feeding and keeping the animals healthy.

“Keeping krill happy in captivity is all about trying to keep them as nourished as possible. So we grow live algae cultures, and we also supplement with some commercially available feeds.”

Inside the lab the team will also run feeding and exposure experiments to increasing temperature as well as acidity to understand the impacts of climate change.

Longer term, the team will turn their attention to developing a new krill lab in Hobart in partnership with the University of Tasmania, with five times the capacity and providing unprecedented capabilities for scientists.

Krill are a keystone species Photo: Pete Harmsen

Report: Australian Antarctic Division (AAD)