November 5 - 11, 2023: Issue 604

Lindsay Dufty

WWII Veteran - Remembrance Day 2023: Darwin, February 19, 1942

This Issue, as a prelude to Remembrance Day 2023, Saturday November 11th, Honouring Australian service personnel who have died or suffered in wars, conflicts and peacekeeping operations, Lindsay Dufty's war service memoirs, as collected by John Sowden, Secretary of the War Veterans Village [Narrabeen] RSL sub-Branch, are shared.

Remembrance Day 2023 will be observed with Commemorative Services at Palm Beach RSL cenotaph commencing at 10.45 a.m., at Pittwater RSL, commencing at 10.20 a.m. at the lower cenotaph, at Avalon Beach RSL cenotaph, commencing at 10.30 a.m. at the cenotaph, at RSL ANZAC Village, Narrabeen, commencing at 10 a.m., and at Narrabeen RSL Cenotaph on Ocean street and Pittwater road, commencing at 10.45 a.m. for Narrabeen RSL Sub-branch members and family.

On the 19th of February each year, we commemorate the Anniversary of the Bombing of Darwin. In 2011, Bombing of Darwin Day joined Anzac Day and Remembrance Day as a National Day of Observance. It is 81 years ago that Australia faced this attack on home soil.

Lindsay Allan Dufty was on the ground in Darwin on February 19th 1942. He had enlisted at Willoughby in October 1941 and was called up for duty in the Army in Sydney on January 7th 1942. He and a schoolmate, Stan Burrows, found themselves in the same place at the same time. They were 18 years old and weren't close friends before serving but remained lifelong mates afterwards.

Lindsay celebrated his 100th birthday on May 8th 2023.

After two days of basic training Lindsay and Stan volunteered for a “hush hush” new unit. The radio direction finder, or RDF, unit would train on secret equipment for determining the position and direction of aircraft and be stationed on the islands north of Australia.

“It sounded intriguing,” Lindsay explains, “We attended a few lectures and saw the equipment working at Beacon Hill. They sent us to North Head for inoculations and fitting out with tropical gear. Then, incredibly, on January 14th we were sent on three days final leave.”

Lindsay and Stan took 10 days to travel to Darwin on troop trains and troop trucks, and in cattle trucks with open slat floors and tarpaulins for the rain. They arrived in Darwin on February 1st 1942.

The Bombing of Darwin, also known as the Battle of Darwin, on Thursday the 19th of February 1942 was the largest single attack ever mounted by a foreign power on Australia. On that day, 242 Japanese aircraft, in two separate raids, attacked the town, ships in Darwin Harbour and the town's two airfields in an attempt to prevent the Allies from using them as bases to contest the invasion of Timor and Java during World War II.

The two Japanese air raids were the first, and largest, of more than 100 air raids against Australia during 1942–1943. The event occurred just four days after the Fall of Singapore.

Darwin was attacked by aircraft flying from aircraft carriers and land bases in the Netherlands East Indies (NEI). The main force involved in the raid was the 1st Carrier Air Fleet which was commanded by Vice-Admiral Chūichi Nagumo. This force comprised the aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū, and Sōryū and a force of escorting surface ships. All four carriers had participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th 1941. In addition to the carrier-based aircraft, 54 land-based bombers also struck Darwin in a high-level bombing raid nearly two hours after the first one struck at 09.56. These comprised 27 G3M "Nell" bombers flying from Ambon and another 27 G4M "Betty" bombers operating from Kendari in Celebes.

A total of 65 Allied warships and merchant vessels were in Darwin harbour at the time of the raids. Darwin was lightly defended compared to the size of the attack, and the Japanese inflicted heavy losses upon Allied forces at little cost to themselves. The urban areas of Darwin suffered damage from the raids and there were a number of civilian casualties. More than half of Darwin's civilian population left the area permanently, before or immediately after the attack.

LINDSAY DUFTY’S WAR SERVICE

by John Sowden,

Secretary of War Veterans Village [Narrabeen] RSL sub-Branch

With added thanks also to Helen Johnston, RSL LifeCare researcher and writer for her 'Hidden Treasures' series, and the New South Wales Government's 'Life Stories' series on the NSW War Memorials Register website.

At 9.58AM on 19 February 1942, when the war in the Pacific was just 10 weeks old, Australians were awoken to war on their doorstep with the bombing of Darwin by 188 aircraft of a Japanese naval carrier taskforce. The primary objective was to inflict as much damage as possible on the shipping and port facilities of Darwin Harbour. This first air attack was quickly followed by a second at 11.57AM the same day of 54 land-based aircraft and was directed at neutralising the RAAF Base at Darwin. The two air attacks brought death, destruction, and confusion of a degree then unknown in Australia.

At 9.58AM on 19 February 1942, when the war in the Pacific was just 10 weeks old, Australians were awoken to war on their doorstep with the bombing of Darwin by 188 aircraft of a Japanese naval carrier taskforce. The primary objective was to inflict as much damage as possible on the shipping and port facilities of Darwin Harbour. This first air attack was quickly followed by a second at 11.57AM the same day of 54 land-based aircraft and was directed at neutralising the RAAF Base at Darwin. The two air attacks brought death, destruction, and confusion of a degree then unknown in Australia.

Located within the confines of Darwin’s Harbour at the time of the attacks were 49 ships including a hospital ship, 32 Australian naval vessels and two American naval vessels.

Two hundred and forty-three people were killed, approximately 350 injured. Eight vessels were sunk within the Harbour, a further two were sunk at sea off Bathurst Island, and another two were beached to prevent them sinking. Thirteen other vessels were badly damaged or put out of action. Forty-five aircraft were destroyed and there was great property damage in the port, the township, and the air bases.

The above description sets the scene of devastation in and around Darwin in the middle of February 1942 about 2 months after the bombing of Pearl Harbour. It is believed the aircraft involved in that attack were from the same Japanese naval carrier taskforce as those that attacked Darwin.

Just one month earlier – in fact on 7 January, 1942 – a young 18-year-old Lindsay Dufty fronted up at a military depot off Victoria Avenue, Chatswood and happened to find an old school mate, Stan Burrows, doing the same thing. They became great mates and have remained so to this day. Lindsay was sent to Georges Heights for a couple of days drill exercises and when asked for volunteers to go to northern Australia to operate some new special equipment he stepped forward and found himself joining a very secretive new unit called R.D.F. (Radar Direction Finder).

He and Stan were attached to 22nd AA Battery as Gunners and told to be ready to move by 20 January. He spent the intervening time at North Head getting vaccinations and tropical equipment, some time at the Artillery School, a few days at Chowder Bay, some lectures at Beacon Hill, and was given 3 days final leave.

''We were taken to Beacon Hill to see a machine operating which could pick up a rowing boat well out to sea providing it had steel rowlocks.'' Lindsay explained

On 23 January he took the train to Melbourne and Adelaide where he joined a troop-train to Darwin via Alice Springs on the old Ghan train track. From Alice to Darwin was in Army trucks for several hundred kilometres along corrugated red dust roads before changing to cattle trucks on a narrow-gauge railway at Birdum/Larrimah for the last 500km to Darwin. The cattle trucks had slatted floors (you can guess why?), board sides and a tarpaulin over the top.

They had torrential rain with the tarps becoming bellies of water until a bayonet would let it out and continue to give some shade in the heat and humidity.

Lindsay arrived in Darwin on 1st February 10 days after leaving Sydney and was allocated to Larrakeyah Barracks where he settled in by cleaning out the accommodation, washing and sleeping.

Life in Darwin commenced with morning drills, RDF lectures in the afternoon and sometimes a movie after dinner in the open air on canvas seats and would see the glow worms along the side of the road on the way back to barracks.

In February the Harbour was full of supply ships and a troop transport convoy. Some flights over the city, at high altitude, had been noticed with little action taken to identify them although the alarm was sounded on 17th February.

‘’On 19th February at 0958 while on the parade ground all hell broke loose. Bombs started falling all around, wave upon wave of bombers passed overhead and fighters streaked across at rooftop level.

There really was no defence of the airfield. Some American Kittyhawk’s (with some still in the air) were caught on the ground by the Japanese Zeros and did not stand a chance, having landed for refuelling.

All senses were overwhelmed by the destruction that followed. All shipping in the Harbour was either sunk or burning, the town was a shambles and a great pall of smoke hung over the scene. After the noise of the bombing, aircraft and anti-aircraft fire, the silence was rather eerie.

The job now was to right overturned vehicles and clear debris from the streets. A second wave of bombers followed with the main target being the airfield.’’

The Japanese lost four aircraft in the first raid – two Val dive bombers and two Zeke fighters. One of the fighters crash-landed on Melville Island, north of Darwin. Its pilot became the first prisoner of war taken on Australian soil when he was captured by Tiwi man Matthias Ulungura. Photo courtesy AWM

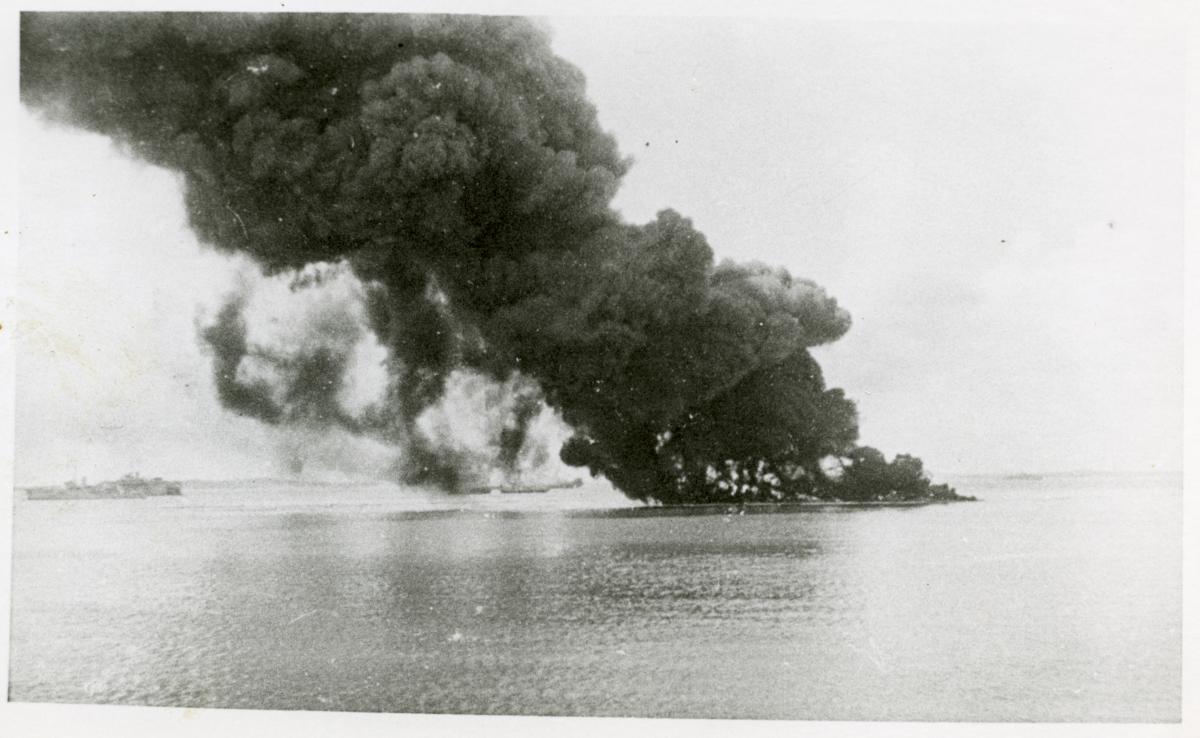

Oil tanks in Darwin on fire after bombing, 1942. Photo PH0808/0004, courtesy Northern Territory Library

Between the two raids on the airfield, Lindsay’s section of Gun layers replenished the ammunition (shells) for the guns in the gun pits.

The attack on Darwin had been anticipated and most civilians had been evacuated further south. Immediately after the bombings all except essential personnel were withdrawn from the town.

“When we woke the morning after the raid, Darwin was empty. All the troops had been sent 50 to 80 miles south. Only the essential people were left behind. Darwin was on a peninsula and if the Japanese invaded, they didn’t want the troops trapped there.”

After only six weeks in the Army, Lindsay and Stan found themselves on very active service in a war zone. Not long after the second raid, a ship at the wharf which was carrying ammunition including depth charges was burning and suddenly there was an almighty explosion – sections of the ship were scattered over a wide area and a huge column of smoke shot skywards with an incredible smoke ring formed in the upper atmosphere.

The Japanese bombed the wharf and ships moored in the harbour. Six large vessels were sunk and another 14 ships were damaged. The MV Neptuna exploded at the wharf causing massive damage. The greatest loss of life occurred when the destroyer USS Peary (pictured) sank killing 88 people. Photo: 6_NTL-PH0566-0017, courtesy Northern Territory Library

For some days after the 19th, bodies continued to be washed up on the beaches.

Lindsay said, “We did get bodies washing up from the ships onto the beach below us. They were in a horrible condition. We had to haul them up above the tide and put rocks over them to save them from the crocodiles till the people came to collect them.”

However, the recovery of bodies did not have a high priority so the stench soon became quite unpleasant. The anti-aircraft sites were restocked with ammunition and recommenced operating.

Working at the oval, Lindsay and Stan felt pretty exposed to enemy attack. “We were told we could have a slit trench if we dug it ourselves, but we hit solid rock six inches down. Instead, we had to crouch down between the masses of ammo in the grandstand for shelter. If a bomb hit, they would never have found us.”

Lindsay and Stan were inducted into the 14th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery and moved from supplying the ammunition to manning the guns during enemy raids.

They were soon allocated the job at the RAAF aerodrome of clearing the airstrips of debris and when in early March they were strafed by three Zeros it soon became clear how exposed one can feel on an airstrip. Fortunately, there were slit trenches to ensure some protection from the hail of bullets thudding into the ground.

''This new unit’s mobile guns were usually out in the bush protecting airstrips. These positions entailed total isolation in very primitive conditions with strict water rationing (one kerosene tin per person for all uses), maggot infested food, endemic dysentery and tropical ulcers that ate into your legs. The mobile guns had to be dug into the ground with pick and shovel and moved frequently.

“What were we young guys thinking – food was scarce, rice became the regular ration each day, invasion was considered imminent, we were vulnerable.

We were given 10 rounds of .303 ammunition, a packet of 6 Sao biscuits, a pinch of tea and salt were issued to be used only in an emergency. In the event of an invasion, we were ordered to fight for as long as we were able and in an extreme situation, spike our guns, then every man for himself.

After the raids on 19th February, air cover was nil but morale was excellent. I was now incorporated into the gun crews and lived in camouflaged shelters against the gun revetments. It was so hot and humid I wore only shorts or lap-lap, boots, and hat.

The Japs seemed to pick on lunch time for a visit with between 7 and 27 bombers accompanied by fighters. One raid stands out – April 2, a cloudy day, and after getting one salvo away were heard the ripping sound of bombs falling and were ordered to ‘take cover’ – not easy in a gun pit full of H.E. (high explosive) shells.

On the 4th April the first salvo hit the point of the formation, three bombers fell behind streaming thick white smoke, one falling and one blowing up in mid-air.

The next salvo scattered the remainder in all directions. I observed one chap bail out with his parachute on fire plunging all the way down to the beach. ”

“There was one occasion at the oval when we were told to take cover. There was a formation of Japanese planes coming straight over us. It was pretty hard to take cover. All you could do was lean against the revetment in the gun pit.”

“The bombs came down but, believe it or not, they straddled us. They came down on either side and we got lots of rocks on us, but there was no direct hit.”

“When you’re in action, you’re not frightened because you’re doing your job. There were nine people on a gun and each had a job to do, and you couldn’t let the others down.”

“That day when the planes had passed over, I found myself crouching down by the gun holding the other gunner’s hand. I hadn’t even realised we were doing it.”

Photo 7_NTL-PH0115-0014. Photo courtesy Northern Territory Library

Later in 1942 the air defences were vastly improved after General MacArthur had given Darwin top priority.

The R.D.F. equipment Lindsay was originally sent to Darwin to operate never arrived.

“After the initial air raid, there were 64 other raids. On moonlit nights it was frustrating that the guns were not allowed to fire so as not to give away the positions of the fighters and bombers hidden in their revetments along the highway. ‘’

On one occasion when foraging for firewood Lindsay found a downed aircraft with the pilot’s body still in the cockpit having been burned and with his battered and burned flying goggles (now in the War Vets Museum).

‘’All guns were manned seven days a week and when the alarm sounded you were expected to be at your allotted station immediately regardless of your dress or undress - let your imagination run wild for all the options.’’

“Our unit was the most awarded Australian anti-aircraft unit in World War II. An Aboriginal machine gunner, Wilburt “Darkie” Hudson, got the military medal. He was under the shower when the air raid warning sounded and had no time to put on clothes, just a towel. He took down one of the Zero strafers and his towel dropped off in the action.”

Members of the 14th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery were awarded a British Empire Medal, two Military Medals, a commendation card and a mention in despatches; the most awards obtained by an Australian anti-aircraft unit in any theatre in World War II.

After six months the 14th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery was relieved and Lindsay was sent from Darwin to Western Australia where he served with the 22nd Anti-Aircraft Battery for a further two years, guarding a US submarine base.

“Towards the end of the war, the Japanese had very little air force left,” said Lindsay. “There was no need for so many anti-aircraft gunners.”

By 1945 less antiaircraft was required so it was back to N.S.W. for infantry and mortar training to prepare them for New Guinea, before Lindsay was found after a medical check-up to be unfit for further service.

“I was deemed unfit for tropical service,” said Lindsay. “In one way I was relieved, but I wondered why they didn’t do the medical exam before we did the infantry training.”

Lindsay was sent to the ordnance depot in Muswellbrook where he worked as the sole armed guard on the goods trains transporting ordnance between Sydney and Brisbane.

“Everything was very scarce at that time, so I had to protect the goods from black marketeers. They would jump onto the train as it slowed on the incline and throw stuff off to others following. Seeing someone with a rifle they would let that one go.”

“It was a pretty tough job. I didn’t need to threaten anyone, but I was all by myself on the train and they didn’t send me off with any food.”

“When the train was going very slowly up an incline past cornfields, I would leap off and jump the fence and grab a couple of cobs of corn and get back on the train. If I’d fallen and missed the train, I would have been in trouble.”

Lindsay was in Muswellbrook when World War II ended. He said the emotion he felt was “just relief”.

“My war was not glamorous, far from it. I cannot think of any period in those years on which I can look back with pleasure. Just one small corner, in a global conflict which cost many lives and robbed many young people of their best ‘growing up’ years.”

“But there was comradeship. I had known Stan Burrows from school but we hadn’t really been friends. Our time together in war forged a lifelong friendship. War also gave me an appreciation of how wonderful life is.”

''After the war I had the most remarkable luck in meeting my wife Gwen. We had four children and a wonderful life together.''

DUFTY-ROSE.-The Engagement is announced of Gwen, eldest daughter of Mr. and Mrs. V. A. Rose, of Sydney, late of Taree, to Lindsay, son of Mr. and Mrs. A. L. Dufty, of Willoughby. Family Notices (1947, February 22). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 36. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18016410

Lindsay and Gwenyth, née Rose, were married in 1948 and had 73 wonderful years together, as parents, grandparents and great-grandparents.

''I’ve been here (at the War Veterans Village [Narrabeen]) for 18 years now and I am involved with the War Museum as its Acquisitions Officer. I love living here. I have friends, my family, the garden, and each other to be thankful for.''

The fact that a small group of very young men with basically no Army training went on active service in a war zone within 6 weeks of enlistment must surely be unique.

From the above story taken from Lindsay’s memoirs, one can understand why so many of the school children who come through the War Vets War Museum stand in awe as Lindsay relates his story when describing some of the memorabilia and other items that relate to the ‘Raid on Darwin.’

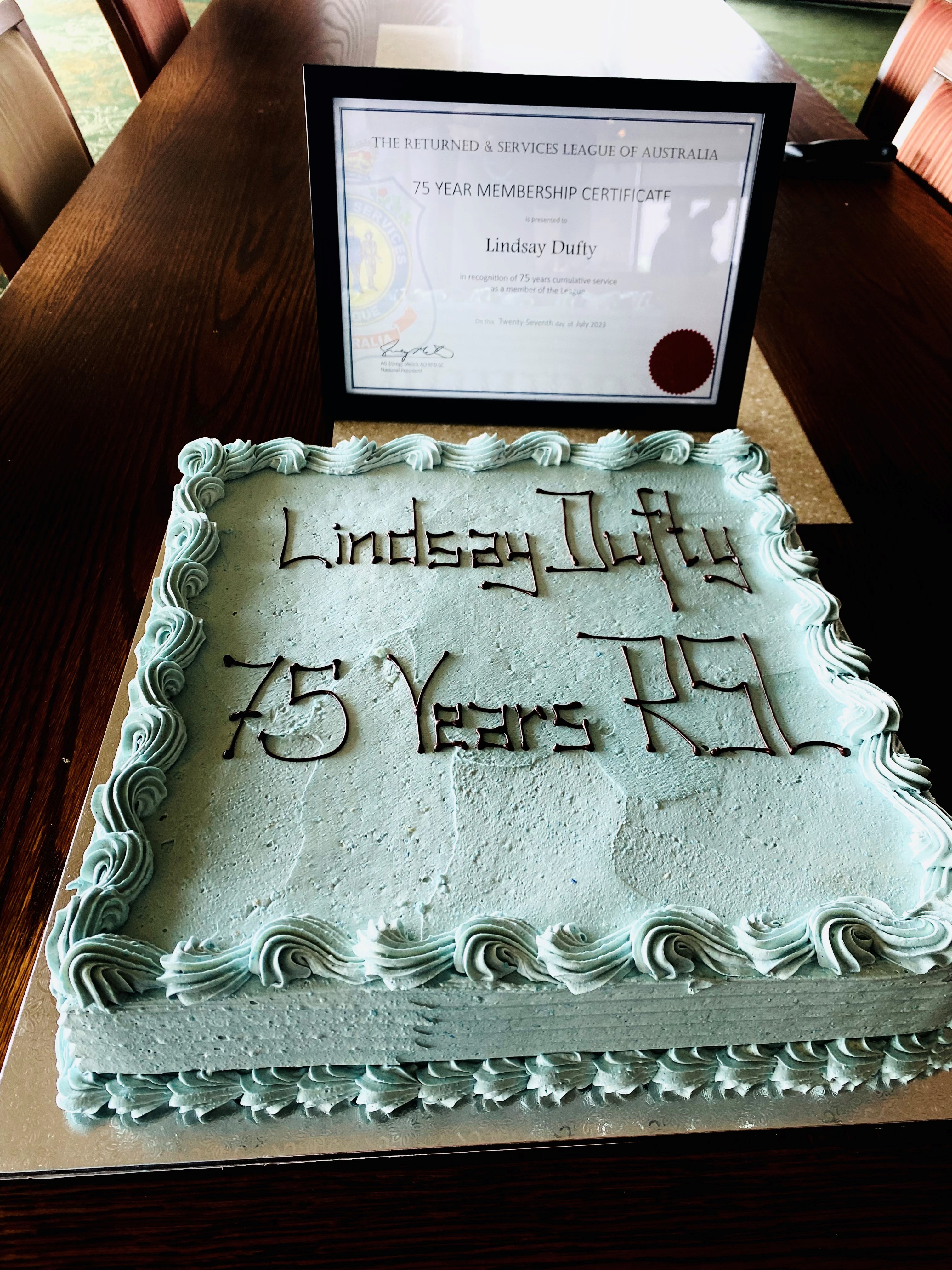

Lindsay turned 100 on 8th May 2023 and has recently been presented with a rather unique Certificate by RSL Australia to acknowledge 75 years of membership – a feat few can achieve.

The September general meeting of the War Veterans Village [Narrabeen] RSL sub-Branch was a little more special than most with this presentation of a 75-Year Membership Certificate by RSLNSW President Ray James OAM to member Lindsay Dufty.

Lindsay joined the RSL as a serving member of the Army in 1944 so he is coming up to 80 years of membership – what an achievement. Members state 'It was nice to celebrate with a cake sign-written with Lindsay’s name and “75 years RSL.”-'

Photo: Lindsay with his granddaughter Karen and his daughter in law Sue (mother to Karen).

Lindsay Dufty being presented with his 70th year Membership Certificate by State President Ray James OAM, and with Chaplain Bob Durbin, President of War Vets sub-Branch Narrabeen (at left)

The cake! Photos by and courtesy Beverley Ash

RSL NSW President Ray James said: ''Last week I awarded Lindsay Dufty for his 75-year commitment to supporting veterans and their families as a member of RSL NSW.

Wearing our membership badge is not about what you can get from the League, but what you can do for your fellow members and veterans. Lindsay is a fine example of the how RSL members across Australia are working each day to support their mates.

His remarkable 75-year tenure embodies the unbreakable bond that ties us all to the RSL and his enduring commitment is nothing short of inspirational.''

A Few Extras

4 SHOT DOWN

DAMAGE "CONSIDERABLE": CASUALTIES UNKNOWN

DARWIN WAS HEAVILY BOMBED BY 93 JAPANESE PLANES IN TWO RAIDS YESTERDAY.

Mr. Curtin, Prime Minister, announced last night that the first attack was made by 72 twin-engined bombers, accompanied by fighters. The second was by 21 twin-engined bombers.

"It is known for certain that 4 enemy aircraft were brought down," he said.

"Damage to property has been considerable, but reports so far to hand do not give precise particulars as to loss of life."

In a communique announcing the first raid, Mr. Drakeford, Air Minister, said that preliminary reports indicated that the attack was concentrated on the township. Shipping in the harbour was also bombed.

There were some casualties and damage to service installations. The raid lasted about one hour.

The first raid began about 10am (Darwin time). The second took place in the afternoon.

In his announcement last night Mr. Curtin said :— " The Government regards these attacks as most grave and makes it quite clear that a severe blow has been struck in this first battle on Australian soil.

''It will be a source of pride to the public to know that the armed forces and civilians conducted themselves with the gallantry that was traditional in people of British stock.

'Although the information does not disclose the details of casualties, it must be obvious that we have suffered' We must face with fortitude the first onslaught and remember that whatever the future holds in store for us we are Australians and will fight grimly and victoriously.

'Let us each vow that this blow at Darwin and the loss is has involved and the suffering it has occasioned will have the effect of making us grid up our loins and nerve our steel. We, too, in every other city can face these assaults.

'Let it be remembered that Darwin has been bombed, but it has not been conquered.'

After announcing the first raid yesterday morning Mr. Curtin said:

"Australia has now experienced the physical contact of war within Australia. Face it as Australians!

"As head of the Government I know there is no need to say anything else. Total mobilisation is the Government's policy for Australia. Until the time elapses when all the necessary measures can be put into effect, all Australians must voluntarily answer the Government's call for the complete giving of everything to the nation."

"What we have feared has now happened, and Australia, for the first time in its history, has been subjected to attack," said Mr. Dunstan, Premier, yesterday.

"The enemy had crossed the threshold of our native land Our testing time is at hand and people must face things in the light of reality. There is no room for conjecture or complacency."

We could no longer have doubts regarding the enemy's intentions nor his ability to bomb this country. The feeling of splendid isolation no longer remained. Our mettle was about to be tested, but he was confident none of us would be found wanting. Unity must be our watchword, national service our one desire Only by a united effort could we play the part that was expected of us. Nothing less than our best, given ungrudgingly, would do.

Senator Ashley, PMG, said yesterday that cable services would not be interrupted as a result of the bombing of Dar-win. Even if the cable system were temporarily destroyed communication would be carried on through other channels.

HEADLINES IN LONDON

LONDON, Thursday

Evening newspapers play up the Darwin raid with front page streamers. Headlines were :— Evening Standard: "Australia First Bombs. Radio Closes Down as Japanese Raid Dar-win." Evening News: "First Bombs on Australia. Darwin Attacked for Hour." Star: "Australia Has Its First Air Raid. Port Darwin Bombs Cause Casualties and 'Service' Damage."

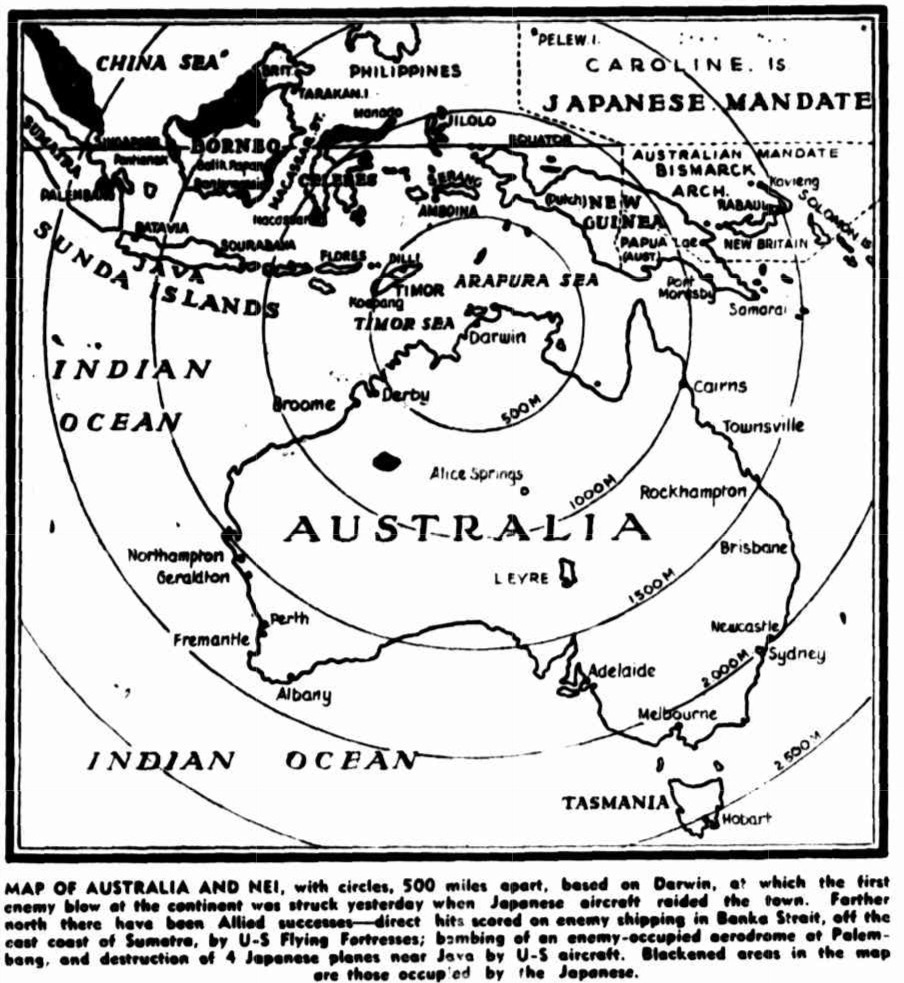

MAP OF AUSTRALIA AND NEI, with circles, 500 miles apart, based on Darwin, at which the first enemy blow at the continent was struck yesterday when Japanese aircraft raided the town. Farther north there have been Allied successes-direct hits scored on enemy shipping in Banka Strait, off the east coast of Sumatra, by U-S Flying Fortresses; bombing of an enemy-occupied aerodrome at Palembang, and destruction of 4 Japanese planes near Java by U-S aircraft. Blackened areas in the map are occupied by the Japanese.

AERIAL VIEW OF DARWIN HARBOUR, where shipping was attacked when enemy aircraft raided the town yesterday morning. The township extends to the left of this picture. Yesterday's raid was the first attack launched by the enemy on Australia itself. DARWIN HEAVILY BOMBED IN 2 RAIDS (1942, February 20). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article8233704

EYE WITNESSES TELL OF DARWIN RAID

WAVES OF DIVE-BOMBERS

"BLITZ OF MOST FEROCIOUS KIND"

The first stories of the Japanese raids on Darwin were told by air passengers who reached Townsville last night.

Men who were there during the raids declared it was worse than anything they had experienced in London. It was a blitz of the most ferocious kind.

There was very little warning of the first raid. Within two minutes of the alert bombs were falling. The bombers came over in seven or eight waves. It was perfect formation-pattern bombing.

There were nine machines to a wave, and they came over at intervals of about three minutes.

The machines kept their formation, dropped their bombs, and passed on their way.

The raiders appeared to concentrate on the harbour, bombing from 8,000 feet or 9,000 feet and using probably 500lb bombs.

The Post Office received a direct hit. It was in this burst that nine persons were killed. Some girls met their deaths at their post in the telephone exchange.

Following the big bombers, two waves of dive-bombers came over. Some of these dived from a great height to within 100 feet of the ground, bombing and machine-gunning. Others were not so daring, and gave the impression that the pilots had one hand on the bomb-control and the other on the joy-stick, ready to rise again.

When the alert was first sounded, people naturally ran for cover, but most of them were still running when the bombs began to fall.

Some sought shelter in trenches, others ran for the bush, while others made for open paddocks.

A.R.P. and ambulance organisations functioned well, and injured persons were hurried to the hospital, which, however, was hit by a bomb and dam-aged. The medical staff and nurses did wonderful work. Everyone had the warmest praise for the girls of the nursing services.

There was another raid at 11 a.m., which lasted about 20 minutes. In this, said the eye-witnesses, 54 machines were engaged, two formations of 27 each. They added to the destruction previously caused.

A flying-boat moored in the harbour suffered only two small holes in the fuselage. EYE-WITNESSES TELL OF DARWIN RAID WAVES OF DIVE-BOMBERS (1942, February 21). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17788982

The Darwin Post Office was located on the site where Parliament House and the Northern Territory Library are today. As the first raid began, staff ran to a trench constructed at the rear of their building. Tragically, it received a direct hit, killing all ten employees taking refuge there. Photo courtesy Northern Territory Library

BOMBING OF DARWIN

Vivid Accounts

Vivid eye-witnesses' descriptions of the sudden Japanese raids on Darwin on Thursday were given by passengers from Darwin, two of them injured, who arrived in Sydney on Saturday in a flying-boat which left Darwin at dawn on Friday. Machine-gun bullet holes in the flying-boat gave evidence of the raid.

According to their accounts high-flying bombers and dive-bombers were used in the raid, and attacking planes also machine-gunned the streets.

The unfaltering way in which the attackers found their tar-gets with the first run of bombs made it obvious that they knew exactly where to strike, in the opinion of Captain A. A. Koch, of Qantas Empire Airways.

He added that he was convinced the enemy was getting regular information out of Darwin.

Captain Koch was commander of the flying-boat Corio, which was shot down near Koepang by the Japanese on January 30. He was bombed four times in Koepang, and had only been a patient in the Darwin Hospital a few days when Darwin was raided.

He was carried ashore on a stretcher wearing only pyjamas, slippers, and an overcoat—the clothes in which he had left the Darwin Hospital.

HOSPITAL BOMBING

Describing the bombing of the hospital, Captain Koch said:—

"I heard the wail of sirens and the roar of planes overhead almost simultaneously. I managed to get under my bed before the first bombs fell. A wing of the hospital was hit, and the nurses, who knew I had been in raids before, followed my ex-ample, and started getting other patients under their beds.

"After the first shock was over they started getting patients down to the beach, about 200 yards away. A doctor and nurse helped me to the shelter of some bushes, and covered me with a mattress. We could hear bombs falling in other parts of the town. A doctor was in the middle of an appendix operation when the raid began, but I don't know what hap-pened to the patient."

Captain Koch said that he saw men swim ashore from ships in the harbour, and one man had his lungs badly injured by concussion from a bomb that fell near him in the water. He said that bombs of about 500lb were dropped from high levels, dive-bombers were used, and the streets were machine-gunned in the raids.

SAVED FLYING-BOAT

Captain H. B. Hussey and Captain A. H. Crowther were probably responsible for saving the flying-boat which was at anchor in the harbour at the beginning of the raid.

"I was waiting in the barber's for a haircut when I heard the sirens wail."

"I had to dodge pieces of falling stone and masonry which were hurled high into the air by explosions. A piece of heavy lead piping from the post-office, which received a direct hit, landed near me. People flung themselves into the gutters for shelter.

"As soon as the fall of bombs eased Captain Crowther and I made our way to the wharves. Dense smoke screened the flying-boat from the attackers, although bombs were dropped between it and a ship again and again."

Captain Hussey said he found a launch and with Captain Crowther made his way out to the flying-boat, which to their surprise they found in-tact. "We clambered on board and found the engineers had left the engines in flying order. We taxied away, and across the water we examined the hull to see if it had been damaged by concussion.

"We could still hear bombs fall-ing, so we decided to try and save the plane. We took off and flew down the coast and did not return till dusk, when we considered it safe. We worked on the plane and loaded it all night and left at dawn the next day."

Two casualties in the raid were Mr. J. R. C. Morris, a staff member of Qantas, who was wounded in the shoulder by a piece of shrapnel, and Mr. A. Ruddman, manager of a boarding-house in Darwin, whose hand was injured.

Mr. Ruddman declared that he thought Darwin was taken by surprise by the raid. "No one seemed to know whether the sirens sounded first or whether the crash of bombs was the first warning that we were being raided," he said.

Mr. Ruddman paid a special tribute to crews of the anti-aircraft guns who, he said, did a marvellous job. "They never ceased blazing away with their guns even when the enemy came down to within a couple of hundred feet. They certainly were game," he added. "So were the civilians. They proved that Australians can 'take it,' too."

BOMBING OF DARWIN Vivid Accounts (1942, February 23). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17789244

Darwin Hospital post February 19 1942. Photo: 1B_NTL-PH0861-0111, courtesy Northern Territory Library

The two air raids on 19 February 1942 caused extensive damage to essential services, shipping, and defence installations, and resulted in 237 deaths. A federal commission of inquiry established to investigate the raids found that the military had made many mistakes in Darwin. Japanese air raids continued until 12 November 1943. Photo: 11_NTL-PH0808-0021. Photo courtesy Northern Territory Library