August 21 - 27, 2022: Issue 551

Commissioning Of MRNSW Rescue Vessel Broken Bay (BB21) 'Bungaree' + New Base Construction Progress Inspection

On Saturday August 20th 2022 two brilliant and historic events took place at the Bayview base of Marine Rescue Broken Bay; the commissioning of a new rescue vessel for the Unit and a Progress Inspection of the building site where a new purpose-built base is being constructed.

Unit Commander Jimmy Arteaga provided an update of the Base building works, where the ground slabs and primary beams are already in place, explaining the layout of the build. Jimmy explained that the community will have access to a space in the Base, ‘because we are part of the community’, which is also alongside where the new kitchen and bathroom will be.

Marine Rescue Deputy Commissioner Operations, Alex Barrell, said that the new facility would showcase the latest generation of online marine radio technology, as well as a large training and meeting space, storage for rescue equipment, offices, amenities, kitchen facilities, a wet area for boat crews, and improved access for volunteers living with a disability.

The new rescue vessel, built specifically for local conditions, has several unique features.

“Designed with input from our volunteers, the new rescue vessel boasts a drop-down bow allowing it to pull up to beaches to rescue stranded boaters and walkers; as well as sonar, radar, a full Raymarine navigation suite and greater safety and protection on the water for its volunteer crew.” Deputy Commissioner Barrell said.

Unit Commander of Marine Rescue NSW Broken Bay Unit Jimmy Arteaga revealed the name for the new vessel, as chosen by the Unit’s Members, is ‘Bungaree’ to honour Broken Bay’s most revered of saltwater men.

As our younger readers LOVE the boats but may not have heard much about Bungaree as yet, this Issue we run an historic insight written by one of his still living here relatives, Uncle Neil Evers.

You can read all about Bungaree below and all about the new rescue vessel for Broken Bay HERE.

Bungaree Was Flamboyant

Bungaree (1775 ‐ 24 November 1830) possibly born at Patonga, was of the Garigal Clan and Pittwater People or saltwater people.

Bungaree (1775 ‐ 24 November 1830) possibly born at Patonga, was of the Garigal Clan and Pittwater People or saltwater people.

He was flamboyant, intelligent and shrewd. He was an explorer, a great voyager, a go-between, an esteemed elder of his people, a beggar and, at times a drunkard. He was a clever communicator and a mimic when language failed. He reached out across the cultural gulf to become a valued friend of Matthew Flinders, Governor Lachlan Macquarie and many explorers, writers, botanists and artists.

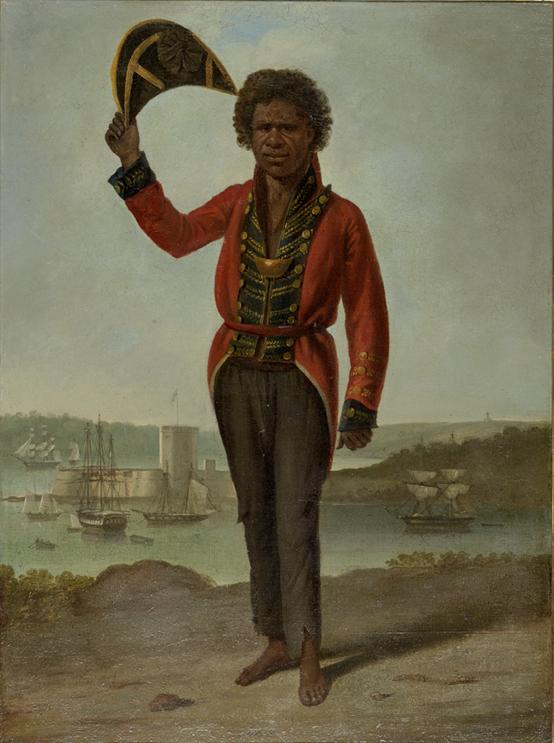

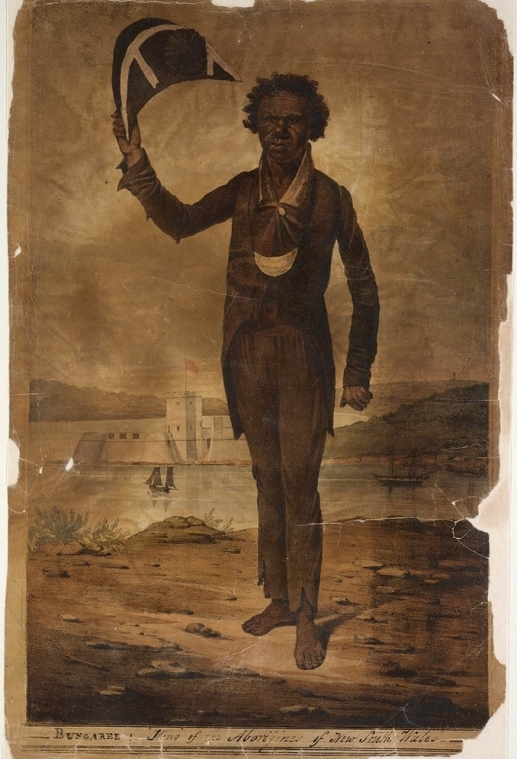

Right: Portrait of Bungaree circa 1826 by Augustus Earle.Image No: nla.pic-an2256865, courtesy National Library of Australia (Portrait of Bungaree, a native of New South Wales, with Fort Macquarie, Sydney Harbour, in background)

Bungaree mimicked the walk and mannerisms of every governor from John Hunter to Sir Thomas Brisbane and perfectly imitated every conspicuous personality in Sydney. He spoke English well and was noted for his acute sense of humour. He also helped authorities in tracking escaped convicts.

Bungaree and his people brought with them their Garigal language, which is now mistakenly called Kuringgai (Guringai), a name first coined by the Reverend John Fraser in 1892 and used by linguist Arthur Capell in 1970 ‘for convenience’.

At the time of European settlement in 1788 the land enabled the Guringai people to maintain a high standard of living from the plentiful fish, shells, seals and marine life of the waters and well stocked hunting lands along the peninsulas and foreshores of the region.

The number of Aboriginal sites adjacent to the mouth of Broken Bay estuary was greater than areas further upstream or inland. The implications for the Barrenjoey Peninsula/Pittwater area were that the number of sites prior to land development was relatively dense.

Yet between April 1789 and 1790 most of the Guringai people died of a disease, probably small pox against which they had no immunity.

This is in stark contrast to how Captain James Cook saw the Aboriginal people in 1770;

“They are far more happier than we Europeans, being wholly unacquainted not only with the Superfluous, but with the necessary conveniences so much sought after in Europe. They are happy in not knowing the use of them. They live in a tranquillity which is not disturbed by the inequality of condition.

The earth and sea of their own accord furnishes them with all things necessary for Life.

They covet not magnificent house, household stuff, etc.; they live in a warm and fine climate, and enjoy every wholesome air, so that they have little need of clothing; and this they seem to be fully sensible of, for many to whom we gave cloth, etc., left it carelessly upon the sea beach and in the woods, as a thing they had no manner of use for; in short, they seemed to set no value upon anything we gave them, nor would they ever part with anything of their own for any one article we could offer them. This, in my opinion argues that they think themselves provided with all the necessaries of life.”

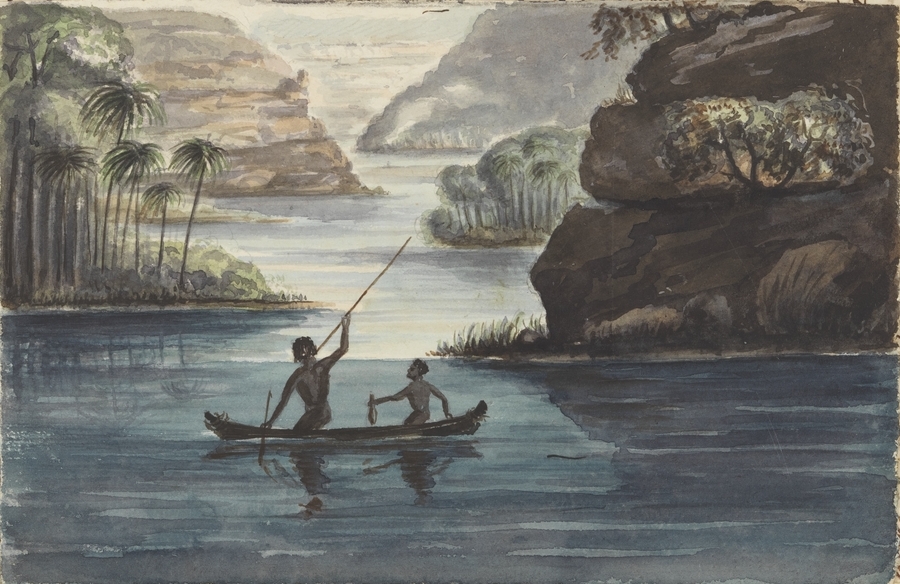

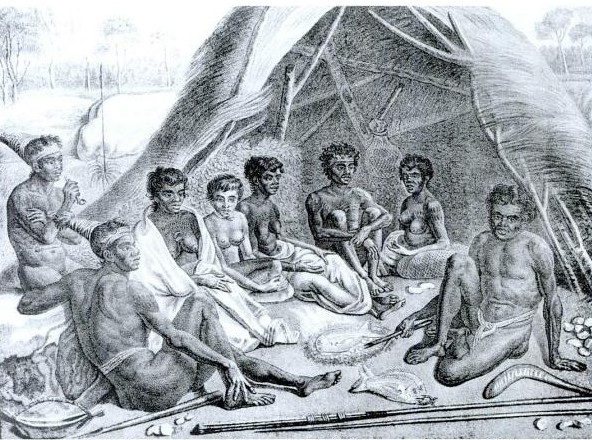

Aborigines spear fishing 1830 by William Govett from Album; ‘William Govett notes and sketches taken during a surveying Expedition in N. South Wales and Blue Mountains Road by William Govett on staff of Major Mitchell, Surveyor General of New South Wales, 1830-1835 Image No.: a5504059, courtesy State Library NSW

This was the life led by Aboriginal people for millennium, way before the white man set foot on Terra Nullius – a land without people. Aboriginal people had lived in this land for more than 60,000 years. They knew this country intimately and had protected its valuable resources.

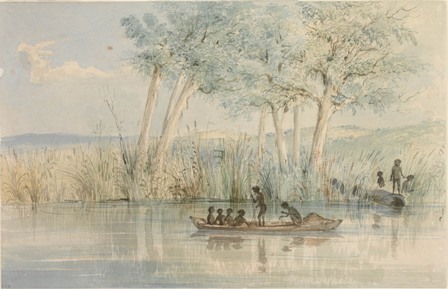

The people that lived along the coast were known as the Saltwater people – at home on the rivers and the beaches. Theirs was a canoe culture, and they went out in large surf onto rock shelves, diving down to catch lobsters and abalone. Whilst the first settlers were starving, Aboriginal people were thriving.

It is such a shame the much evidence of Aboriginal sites has now been obliterated.

Bungaree had several wives, as was the custom. His first wife was named Matora; Cora Gooseberry became his principal wife, with the title of queen.

"Bongry" first went to sea aboard HMS Reliance on May 29, 1798, sailing from Sydney Cove to Norfolk Island. His indigenous shipmates were Nanbarry, a Cadigal, and Wingal from Port Stephens. It was during this 60‐day round voyage that Flinders first met and came to respect Bungaree.

In 1799 Flinders took Bungaree with him on a survey voyage to Bribie Island and Hervey Bay on the 25‐tonne decked longboat, Norfolk. Flinders relied on Bungaree's knowledge of Aboriginal protocol and his skill as a go‐between with local Aborigines during this six‐week voyage.

During 1802‐03 he became the first Australian to circumnavigate the continent 36,000 kilometres of coastline when he sailed with Matthew Flinders in the sloop HMS Investigator which also visited Timor. On this long voyage Bungaree used his knowledge of Aboriginal protocol to negotiate peaceful meetings with local Indigenous people.

Years later, in A Voyage to Terra Australis (1814), Flinders wrote that Bungaree's "good disposition and open and manly conduct had attracted my esteem". Flinders described the affectionate relationship between Bungaree and the cat Trim who sailed on Flinder’s ships: ‘If he [Trim] had occasion to drink, he mewed to Bongaree and leapt up onto the water cask; if to eat he called him down below and went straight to his kid, where there was generally a remnant of a black swan. In short, Bongaree was his great resource, and his kindness was repaid with caresses.’

In May 1804 Bungaree escorted six Aboriginal men returning to the Hunter River from Sydney in the ship Resource. The commandant at Newcastle, Lieutenant Charles Menzies, valued Bungaree's help in capturing runaway convicts and called him 'the most Intelligent of that race I have as yet seen'. However, in October Menzies reported that convicts had taken revenge by killing Bungaree's father 'in the most brutal manner'.

About this time Bungaree took his first wife Matora. According to the Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld, mut-tau-ra, meant 'small snapper' in the Newcastle‐Lake Macquarie ('Awabagal') language group, to which she probably belonged.

Bungaree and his Brisbane Water people settled on the north shore of Port Jackson, bringing their Garigal language with them.

On 31 January 1815 Governor Lachlan Macquarie reserved land and erected huts at Georges Head for Bungaree and his clan to ‘Settle and Cultivate’. Macquarie’s intention was to civilise all the Aboriginal people by first converting Bungaree to the 'benefits' of living a 'civilised' lifestyle and then use him as an example to other Aboriginal people. Also he hoped to keep them away from the British settlement with its temptations of alcohol and tobacco.

Bungaree was given a fishing boat, clothing, seeds, stock and convict instructors and farming implements. Elizabeth Macquarie gave Bungaree a sow and piglets, a pair of Muscovy ducks and outfits for his first wife, Matora, and their daughter.

They were installed with a feast at which the governor decorated Bungaree with a brass plate inscribed 'Bungaree: Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe', a completely fictitious title.

On Tuesday last, at an early hour, His Excellency the GOVERNOR and Mrs. MACQUARIE, accompanied by a large party of Ladies and Gentlemen, proceeded in boats down the Harbour to George's Head.

The object of this excursion, we understand, was to form an establishment for a certain number of Natives who had shewn a desire to settle on some favourable spot of land, with a view to proceed to the cultivation of it. The ground assigned them for this purpose (the peninsula of George's Head) appears to have been judiciously chosen, as well from the fertility of the soil as from its requiring little exertions of labour to clear and cultivate; added to which, it possesses a peculiar advantage of situation; from being nearly surrounded on all sides by the sea; thereby affording its new possessors the constant opportunity of pursuing their favorite occupation of fishing, which has always furnished the principal source of their subsistence.

On this occasion, sixteen of the Natives, with their wives and families were assembled, and His EXCELLENCY the GOVERNOR, in consideration of the general wish previously expressed by them, appointed Boongaree (who has been long known as one of the most friendly of this race, and well acquainted with our language), to be their Chief, at the same time presenting him with a badge distinguishing his quality as "Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe," and the more effectually to promote the objects of this establishment, each of them was furnished with a full suit of slop clothing, together with a variety of useful articles and implements of husbandry, by which they would be enabled to proceed in the necessary pursuits of agriculture : - A boat (called the Boongaree), was likewise presented them for the purpose of fishing.

About noon, after the foregoing ceremony had been concluded, HIS EXCELLENCY and party returned to Sydney, having left the Natives with their Chief in possession of their newly as-signed settlement, evidently much pleased with it, and the kindness they experienced on the occasion.

http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/629052#pstart7249

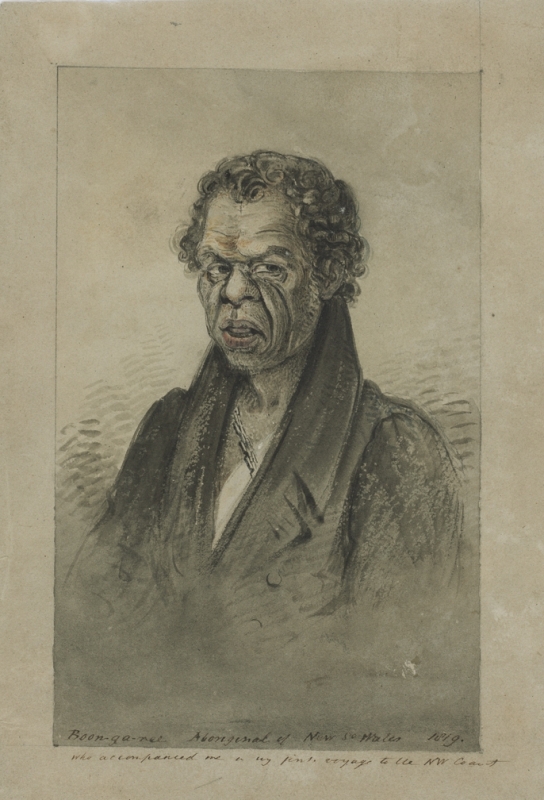

The group did not take to farming and the venture failed. At the end of his term of office in 1822 Macquarie asked his successor, Brisbane, to protect and look after this group. Brisbane gave them a fishing boat and net. At the age of 42 in 1817 Bungaree volunteered to go to sea again on the cutter Mermaid with captain Phillip Parker King, son of governor P.G. King, who surveyed the north and west coasts of Australia. King said Bungaree was "about 45 years of age, of a sharp, intelligent and unassuming disposition, and promised to be of much service to us in our intercourse with the natives".

At the age of 42 in 1817 Bungaree volunteered to go to sea again on the cutter Mermaid with captain Phillip Parker King, son of governor P.G. King, who surveyed the north and west coasts of Australia. King said Bungaree was "about 45 years of age, of a sharp, intelligent and unassuming disposition, and promised to be of much service to us in our intercourse with the natives".

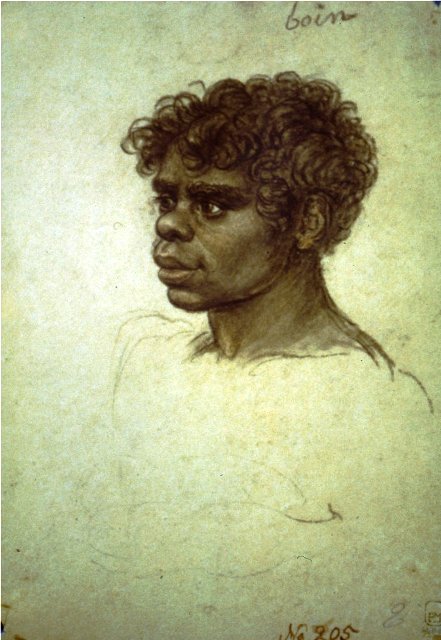

Right: 'Boon-ga-ree' Aboriginal of NSW who accompanied me on my first voyage to the N. W. coast, 1819 Phillip Parker King. Image No.: 3464032h, Courtesy State Library of NSW.

The snub‐nosed cutter Mermaid left Port Jackson on 22 December 1817, put into Twofold Bay, steered through Bass Strait, and followed the Great Australian Bight to King George Sound (Albany). Bungaree assisted the botanist Alan Cunningham, who called him "our worthy native chief" and praised "the character of this enterprising Australian", a very early use of the name.

In June 1818 Mermaid anchored at Kupang, Timor, 15 years after Bungaree's first visit to the island with Flinders. Bungaree promptly returned to a bar that he had been in previously and demanded the change from his drink that had not been given to him.

1821 The day before he embarks on ship for England, Macquarie visits Bungaree to say farewell and to present him with Macquarie’s old uniform and a new boat to use for fishing and greeting arriving ships in the harbour.

Bungaree returns to Sydney and becomes a familiar figure and a lively interpreter for his people. He is a famous mimic of the colonial authorities.

From Georges Head, two of his wives would row Bungaree out to greet the captains of visiting ships. He would climb on board to welcome newcomers to ‘his’ country and then would ask to drink to the captain’s health in old French brandy (for preference) rum or brandy. Afterwards he inspected the ships pantry and levied his ‘tribute’ in the form of ‘presents’ or ‘loans’.

One ship that the family welcomed was the Vostok, a Russian ship that came into Sydney in March 1820 during its expedition to Antarctica.

Captain Thaddeus Bellingshausen thereafter often visited the camp of Bungaree & Matora and noted the various hunting and gathering techniques used by the Aboriginal people. Bellingshausen developed an extremely high regard of Bungaree’s character:

“He is about 55 years of age; he has always been noted for his kindness of heart, gentleness and other excellent qualities and has been of great service to the colony. He has often endangered his life in his efforts to keep the peace within his tribe.

A few years ago an escaped convict fell into the hands of another tribe.

They robbed him, took his axe away from him, and were about to kill him.

Bungaree appeared on the scene, took the man under his protection, secured his freedom, and then for three days carried him across rivers and feeding him roots.

He asked for no reward, save the fugitive’s pardon. The Government of the colony gave Boongaree a long boat as a present. He is a generous man, generally beloved for similar kind actions.”

Frank Debenham (translator), The Voyage of Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas, London: Hakluyt Society, 1945.

Aboriginal camp, showing fishing implements circa 1820, reproduced from The Voyage of Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819-21, 1945 – Bungaree (second from left), Matora (third from left)

When Bungaree attended corroborees and contests, he appeared a transformed man. The coat and plumed hat were gone, his powerful body was dusted with red ochre and painted with red and white clay, his canoe filled with spears and clubs. The warriors moved easily back and forth between white and Aboriginal worlds, and they had made the white world partly their own. (Grace Karksens “Red coat, blue jacket, black skin: Aboriginal men and clothing in early New South Wales”). In 1826 artist Augustus Earle used a lithographic press for a series of Sydney views and to reproduce several impressions of Bungaree which is thought to be the first lithograph ever printed in Australia.

In 1826 artist Augustus Earle used a lithographic press for a series of Sydney views and to reproduce several impressions of Bungaree which is thought to be the first lithograph ever printed in Australia.

Right: 'Bungaree' 1826 Lithograph by Augustus Earle. Image No: a928486, courtesy State Library of NSW

1829 William Romaine Govett surveyed the Northern Beaches and wrote of the Koories living a traditional life along the coast. He described, in the Saturday Magazine, large numbers of Aboriginal people at Cowan Creek, Broken Bay and Barrenjoey.

Hunting and Fishing, 1829, William Govett; (Govett draws Garigal people fishing at Bilgola Beach and North Narrabeen. Hunting and Fishing, 1829, by William Govett, courtesy Manly Museum and Gallery)

Bungaree spent his life ceremonially welcoming visitors to Australia, educating people about Aboriginal culture (especially boomerang throwing), and soliciting tribute, especially from ships visiting Sydney.

Towards the end of his eventful life, Bungaree and his Broken Bay Clan had crossed from the North Shore to camp in the Governor’s Domain, which they shared with Aboriginal people from Newcastle and Port Stephens.

In 1830 Bungaree suffered a long illness that lingered for months. He spent several weeks in the General Hospital and was put on government rations. Bungaree’s friends took him to Elizabeth Bay and later to Garden Island where he died on 24 November 1830. He was buried in a wooden coffin in a grave dug at Rose Bay ‘beside his dead Queen’ Matora.

An Aboriginal clan, the Gommerigal, occupied ‘Gomora’ or Darling Harbour until at least 1830, when the Sydney Gazette 27 November 1830 reported that King Bungaree ‘died in the midst of his own tribe, as well as that of Darling Harbour, by all of whom he was beloved’.

So many artists were drawn to Bungaree’s distinctive image that today he appears in a rich gallery of 18 portraits and other illustrations. This was an extraordinary number as there were only two or three portraits of Governor Macquarie. The artists included Augustus Earle, Pavel Mikhailov, Jules Lejeune, Charles Rodius, Phillip Parker King, John Carmichael and William Henry Fernyhough.

Bungaree and Matora’s eldest son Bowen or Boin was born about 1799.

Bungaree was succeeded, said the Launceston Advocate, 'by his eldest son [Bowen], who is the very semblance of the virtues of his departed father'. In November 1831, 'Young Bungaree' was 'floored by a waddie' (club) at the conclusion of a ritual revenge combat at Woolloomooloo. Bowen and his wife Maria (Man Naney or Maria Jonza, sometimes called 'Queen Maria') usually lived in the Sydney area. They had two children, baptised as Theela and Theeda (Jane) at St. Mary's, Sydney. In 1834 ’Members of Bowen's tribe' were listed as Maria, Jane, Bob, Yama, Tobin (Toby, Bowen's brother) and Dinah (Diana, the fair‐haired daughter of one of Bungaree's wives and a European).

In 1849 Bowen and five other Broken Bay men were taken to San Francisco by Sydney merchant Richard Hill on the brig William Hill with passengers bound for the California goldfields. He was the only one of these men to return. According to historian Maybanke Anderson: Mr. Hill took the blackfellows with him because they were used to boating, and could be employed to row the boats which were needed to carry the crowds who were flocking to the Eldorado. Black Bowen is the only one to return. He speaks with ridicule about America, “That country! No wood for fire, but plenty cold wind … no good for me! No good for blackfellows!”

On his return Bowen resumes his duties as a Police Tracker and reports to police the activities of two assigned servants (convicts) who had escaped and are petty thieves on the Northern Beaches. The men are captured and sent to prison. Bowen’s reputation is now well established as a tracker.

Bowen accompanied John Oxley on his voyage from Port Jackson to Port Curtis and Moreton Bay in 1823. Oxley had been on an expedition with instructions from Governor Brisbane to assess Port Curtis, Moreton Bay and Port Bowen as sites for convict settlements. On 29 November 1823 Oxley wrote that he 'endeavoured to make the Natives through Bowen (our Sydney native who understood something of what they said) & Pamphlet our desire to see the other two white men'. Thomas Pamphlett and the two other white men, John Finnegan and Richard Parsons, were timber‐getters, whose open boat had been wrecked on Moreton Island the previous April and had since lived with Aborigines on Bribie Island. With Finnegan as guide, Oxley in a whaleboat charted and named the Brisbane River (after Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane), returning to the ship on 5 December 1823.

In 1823 the colonists had won the right to distil spirits from grain; build vessels of less than 350 tons; and to participate  in colonial trade. Spirits and liquor was the ‘currency’ of the Colony at the time.

in colonial trade. Spirits and liquor was the ‘currency’ of the Colony at the time.

Pittwater became a haven for those who could escape from Sydney and Parramatta convict goals and concentrations. Pittwater was an unpoliced area and once reached by escapees they were safe from arrest.

By 1832 smuggling had become a significant problem and the Commissioners of Customs in London were considering the solution put forward by the colonial comptroller to establish two customs stations, one each at Botany Bay and Broken Bay. It would take an initiative by George Gipps, Governor of New South Wales in 1843 to eventually see the establishment of the Customs House at Barrenjoey. The prime object was to prevent loss of revenue from illicit dealings.

In 1832, Bowen Bungaree moved his family, wife Maria, two daughters, Theela and Theda (Jane), and newborn Mark to Pittwater, settling beside the old Customs shed (later to become a house) on Barrenjoey headland. Maria’s parents Nan and Jonza came with them.

Right: Bowen Bungaree by Pavel Nikolaevich

Bowen, his mother Cora Gooseberry and their extended family camped in the Domain in Sydney, at a spot near Centipede Rock at Woolloomooloo, through to the 1840s. They were regularly seen at the wharves at nearby Circular Quay, selling fish and oyster catches, and demonstrating how to throw boomerangs.

1836 Surveyor William Govett described the bark canoes on Pitt Water as sitting so low in the water that the people appeared to be actually in the water. The bark to fashion these canoes was peeled in its entirety (after being scorched by fire) from the Bangalay eucalypts (E. Boyryoides) which are still numerous in Palm Beach and on Barrenjoey headland. These trees were also a food source for koalas.

Right: Australian aborigines, their implements and weapons in boat circa 1845, by Samuel Thomas Gill. Image No.: 824237, courtesy State Library of NSW.

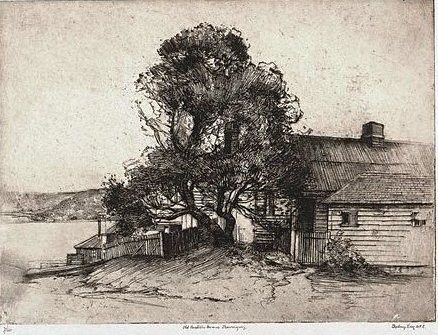

1843 the Broken Bay Customs House was established with convict labour in the sheltered corner of Barrenjoey Headland on the Pittwater frontage to control smuggling and other nefarious practices which had become rife among the settlers of the labyrinth of waterways of the Broken Bay/Hawkesbury River system.

Left: The Customs Shed at Barrenjoey, Image 145 – 0087, courtesy National Library of Australia.

Bowen and his clan comprised eight men, women and children including King Bungaree’s widow Cora Gooseberry and her relation Ricketty Dick. They worked as police trackers, tracker of bushrangers and convicts and finding illegal stills, and also traded fish with the settlers.

Bowen was rewarded with a boat for his own use, which would have allowed him to visit relatives at Broken Bay.

Bowen had been supplied with a rifle to hunt Casey and three other bushrangers, who were a pitiful, sneaking kind of bushranger, robberies were chiefly of rations and clothing of poor settlers. In 1829 Bowen shot and killed the bushranger Casey.

Right: Aboriginal man with rifle, probably Bowen Bungaree, c. 1843-1849, Artist unknown. Image No.: a624005 courtesy State Library of NSW

Right: Aboriginal man with rifle, probably Bowen Bungaree, c. 1843-1849, Artist unknown. Image No.: a624005 courtesy State Library of NSW

Later Bowen was ambushed and shot in the back by the other bushrangers on Bushrangers Hill, Newport 1853.

Excerpt from an article written by Charles de Boos; ‘My Holiday1861 and other early travels from Manly to Palm Beach’

We all adjourned to the verandah, under which we were sheltered from the rain falling from the tail-end of a cloud that had all but passed over.

"It has stopped now, you see," he said.

"Yes, but look at that high headland to the south-ward, on which the succeeding cloud has already commenced to discharge cargo." I had him there.

"It's coming down there, isn't it?" he responded. "It's strange how all the heaviest showers touch that hill first as they come in from the sea."

"Perhaps it's the highest," I suggested.

"So it is; it's the highest piece of ground between Sydney and Newcastle, and when on its top you can see Sydney Heads, and even Botany on one side and Bungaree Norah on the other."

"What do you call it?" I asked.

" I don't know what name they give it on the maps, but we here about call it Casey's Hill," answered Farrell; "that's the name I've known it by from a boy, and it was so called from a notorious bushranger named Casey, who used to make it his haunt."

"Rather an out-of-the-way place," I put in.

"Not at all. There's always been plenty of settlers between here and Lane Cove, and he had the whole country open to him - along the Parramatta River on one side, and the Hawkesbury on the other. He used to come up here after his expeditions, and lay by a bit, because he could see all around him for miles, if any one was in pursuit of him."

"I never recollect hearing of him. What became of him?" I asked.

"He was shot at last by a blackfellow – Black Bowen as we used to call him - one of the finest darkies I ever met with, and I've seen a good many of 'em in my time," he replied.

We now all pressed him to give us the particulars of this "death of the bushranger."

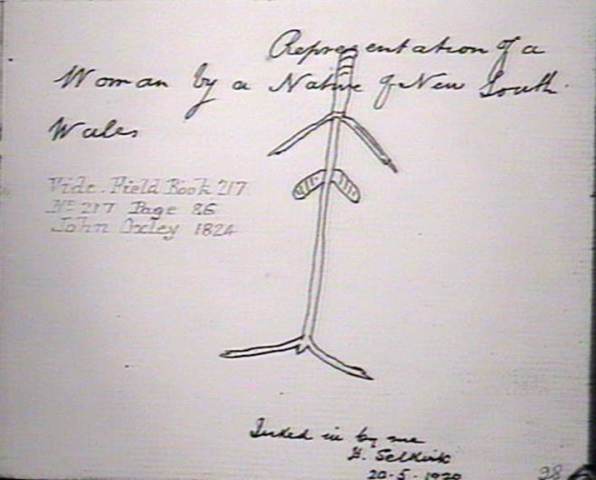

Right: Representation of a woman by a native of New South Wales – Bowen Bungaree 1823. Image No.: d1_13890, courtesy State Library of NSW

Right: Representation of a woman by a native of New South Wales – Bowen Bungaree 1823. Image No.: d1_13890, courtesy State Library of NSW

"I'll tell you all I know about the matter, though it isn't much, and as it happened a long time ago, I forget a good deal about it. However, this Casey was a pitiful, sneaking kind of bushranger, never venturing, like Opossum Jack, or Paddy Curran, or Jackey Jackey, to do business on a large scale, or amongst those who could afford to lose the money he took, but confining his operations to huts and small farm-houses, never caring whether it was an unfortunate Government man that he robbed of his rations, or whether it was a poor devil of a settler, who didn't know which way to turn to make the two ends meet, that he cleared out. His robberies were chiefly of rations and clothing, sometimes a little money, or articles that could be converted into money. (He had had a pretty good run, having been out nearly two years, when at last, in consequence of some ruffianly conduct on his part, the Government determined upon his apprehension. In those days there was very scant ceremony over a convict that took to the bush, and where there was no good reward for delivering him up, the police have been suspected of shooting their man where they found him, just to save trouble in escorting him afterwards. They were out after Casey for three weeks or a month, but deuce a bit could they find him. There he was perched on that hill, and their first appearance sent him off to some of the many secure nooks that are to be found hereabouts, in which a regiment of police would never ferret a man out. He was compelled to take this course, because every man in the district, Government men and all, on account of his plundering his own kind of people, was dead against him.

Now, it happened that Bowen, who was a great favourite with the Governor, had been several times employed to track bushrangers, though it was a job that he didn't like, as his sympathies were rather with than against them, and on one occasion for something he had done this way, he had had a gun made a present to him. This he ever afterwards carried about with him as a trophy of prowess; and it was a trophy, too, for few white men, let alone blacks, possessed a gun in those days. Well, Bowen was very proud of this and took it with him everywhere. One day he was out in the bush towards Lane Cove way, I don't know exactly where, but at all events, he heard great cries and noise coming from a spot where he knew two Government men were stationed in a hut. The word "murder" being used most energetically, Bowen ran as hard as he could to the place, and soon came in sight of the two men who were desperately engaged in defending themselves against Casey, whilst he was attacking them with a large knife in one hand, and a pistol held by the barrel in the other. Bowen at once saw how the land lay, so coming up cautiously, though rapidly, he got within gunshot of Casey, and sent the contents of his piece into the worthless carcass of the bushranger. The charge struck him in the back and lodged in his heart, and he never spoke again. It seemed that he had been blockaded in his hill for so long that his grub had run out and he had been obliged to come down for something to eat. Getting to the hut he was about to steal the poor men's bit of rations, when they came upon him before he had time to get away. A struggle ensued, and a tough one it was too, as the question to be decided was, which of the parties should go without grub for the remainder of the week. Casey was armed only with a pistol, and this he had dis-charged without effect, and had then attacked them with the knife, wounding both so severely as to lay them up in hospital for some weeks afterwards."

"Your Bowen, then, was a plucky dog," said Tom.

"He was," answered Farrell, "and without exception one of the rummest devils I ever saw. He was particularly fond of dress, but would never wear more than one article at a time. Sometimes he would appear in a pair of old regimental trousers; then these would be put aside and he would turn out in a waist-coat, which, in its turn would have to give place to a coat or a hat. But his most favourite piece of finery was an old dress coat of mine, a regular swallow tail that I had given him, and in which he would turn out as proudly as any swell in the land, although he hadn't another stitch on him."

"It is not often that you can get the blacks to wear clothes," I observed.

"Well, Bowen took to this old coat of mine most amazing, putting it on upon all grand occasions of ceremony. Ha! ha! ha! I shall never forget his coming to me one day with it on, to give me information of a bee's nest he had discovered. He was in full fig with the dress coat, his hair knotted up behind, and three feathers stuck init. He took me to the tree, and my noble Bowen at once proceeded to mount in the usual way, by cutting himself foot holes in the trunk, and hoisting himself up with his tomahawk. Arrived at the limb at which was the nest, Bowen proceeded to chop, to make an opening by which to take out the honey. With the first jar of the stroke of his tomahawk, out flew a host of bees, who, circling round, soon discovered their persecutor. They lodged about his body in all directions, but as they don't sting until they are themselves attacked, Bowen would have got off scot free, if it hadn't been for the dress coat. This was buttoned in front, and of course, with every movement of his arm in chopping, the inner surface of the coat rubbed against his body. Now, some of the bees, in the course of their explorations over his person, got between his skin and the coat, and feeling the friction, fancied themselves aggrieved, and at once took revenge by driving their stings into the offending surface, coat or flesh, whichever happened to be nearest. "Ha!" "Oh!" "ha" would poor Bowen cry out, as he felt the prick-up now on one side, now on the other, at the same time bending his body to take off the pressure from the side stung, and thereby causing a friction and a consequent sting on the other side. At last it got so warm that Bowen was coming down, when I, who up to that time had been unable to speak for laughing, told him the cause of his suffering, and directed him to take off the coat. It was with extreme reluctance that he did so; but once relieved of the swallow-tail all went well,

and we got the honey."

"I have always understood that a black would never attempt to ascend a tree with any article of clothing on," remarked Nat.

"No more they will generally," responded Farrell:" but Bowen was very proud of his coat."

“And what became of him, after all?" I asked.

"Poor Bowen!" he replied, his usually joyous tones sinking to a melancholy cadence, "he was shot, whilst sitting at his camp fire, by a cowardly skulking lot of bushrangers, who hadn't the manhood to come up and meet him face to face, for Bowen was game to the back bone, and has stood to me in many a pinch both on land and water."

"Don't you know who killed him?" I again enquired.

"No. The news was brought me by some blacks who found his dead body by the side of the fire, and who, from the tracks around, knew that four armed whites had been there. It was perhaps lucky both for me and for the man who did the deed that I didn't know him, for I looked upon Bowen almost as a brother, and I would have followed his murderer to this day, but I would have had blood for blood."

He was 56 years old. His death was registered at St. Lawrence's Presbyterian Church and his occupation was given as fisherman.

1820 Biddy or Sarah (1803‐1880) is Bowen’s sister and my great great grandmother.

Biddy Lewis (Sarah Ferdinand) at a Public Auction on 13th April 1835 purchased three acres (1.21 hectares) of land at Marramarra Creek for Fifteen Shillings.

Her husband John Lewis Ferdinand, also known as John Lewis, is a Prussian soldier in the German army and has fought in the Napoleonic wars. He deserted and was sentenced to life imprisonment to Australia.

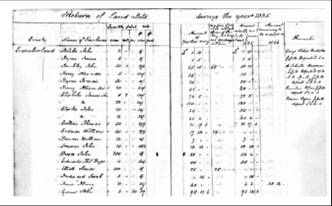

John meets Biddy while working as an assigned convict on Bungaree’s farm at George’s Heights, Mosman Right: Return of Land Sale during the year 1835, documenting the sale to Sarah Ferdinand

Right: Return of Land Sale during the year 1835, documenting the sale to Sarah Ferdinand

He and Biddy have 10 children, seven survive. The family lives by fishing and oyster gathering as well as boat building and selling fruit from their orchard, while Biddy acts as midwife for the whole district. A story is told that Lewis, sailing his boat, would often say to Biddy “Sit in the bow of the boat, Biddy, so I can look at your beautiful face”.

There are known descendants of their children Elizabeth, Mary Ann, James, Thomas and Catherine. The family flourished and lived by burning lime to sell for mortar, boat building, growing fruit and fishing. Biddy is a fisherwoman and farmer.

One child, Catherine, marries Joseph Benns, a Belgian. They settle on Scotland Island, Pittwater.

Catherine becomes known as the ‘Queen of Scotland Island’, and also becomes a famous midwife.

Today descendants of Catherine, James, Mary Ann and Thomas still live on the land of their ancestors on the Northern Beaches of Sydney.

By Neil Evers, 2014

Bungaree's granddaughter is my great great grandmother.

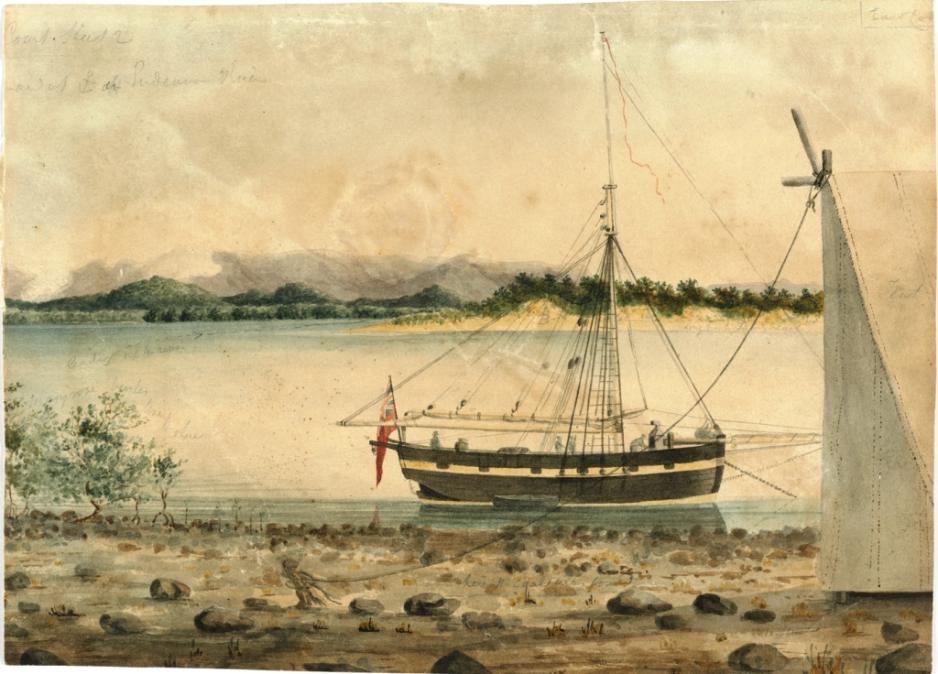

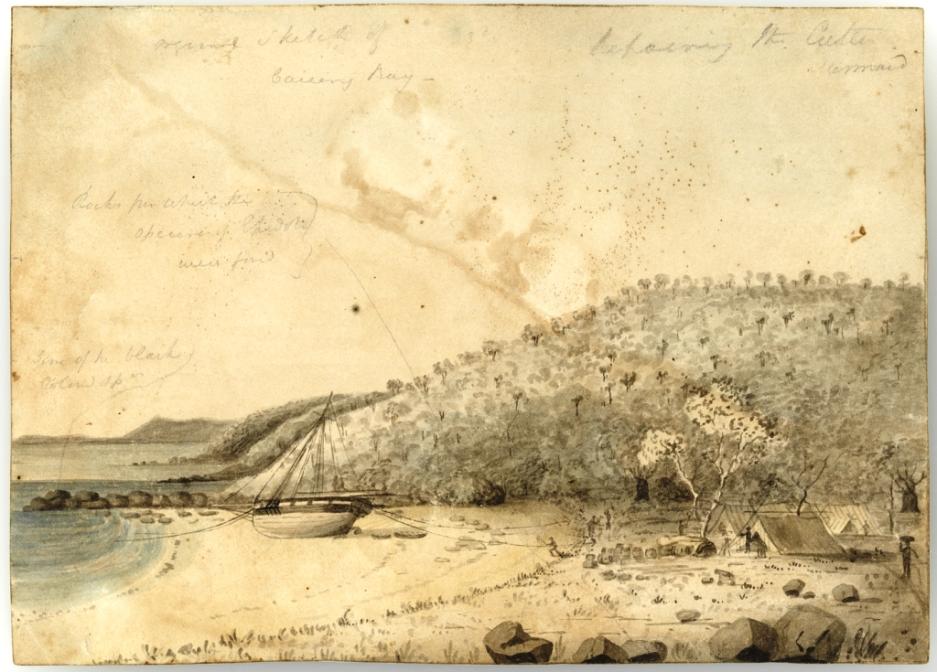

Above: Repairing the Cutter Mermaid, Careening Bay, [1820] Image Number: a3464061 courtesy State Library of NSW.

Below: Mermaid at [symbol of an anchor = anchor] Endeavour River East Coast, [1819] Image Number: a3464059, courtesy State Library of NSW.

Both from Phillip Parker King - album of drawings and engravings, 1802-1902