Maritime Fee Increases From 1 July 2024 - 90% Will Pay $8 More; Jet Ski Riders Will Pay $35

General boat and personal watercraft licence and registration holders are being advised about the fee changes in writing as part of their licence and registration renewal notices.

All Maritime fees have been subject to a 5.89 percent CPI increase. General boat and personal watercraft licence and registration fees have been increased beyond CPI to ensure Maritime is able to continue maintaining its current services levels, while continuing to invest in key boating initiatives across the state.

Over 90 per cent of customers will experience a price increase of less than $35, for example a 1 year licence for a boat will change from $69 to $77. However, jet ski riders will need to meet a higher increase in fees of an extra $35.

Transport for NSW states the higher fees are needed as jet ski riders need more taxpayer-funded resources out on the water to ensure they stick to the rules.

Maritime NSW states:

'PWC users will be subject to the largest fee increase due to a large increase in the number of PWC riders on NSW waterways and higher costs to regulate this segment of boaters. PWC licences and registrations have increased by more than 40 per cent since 2018, which is a faster rate than any other registered recreational vessel group.

PWC remain heavily overrepresented in boating incidents overall and especially in recreational boating serious injury incidents in the last 10 years. As such, the higher fees are directly reflective of the increased resources and effort required by NSW Maritime to regulate this user group.'

The NSW Government announced in 2022 that it would ask boaters for feedback on how boating laws in the state should change – the biggest overhaul of the marine safety regulations in the state for a decade.

It has since launched blitzes targeting jet ski riders. The latest, in February 2024, focussed on what NSW Maritime executive director Mark Hutchings said was “a dangerous minority who have been clashing with residents, boaters and swimmers at popular waterways”.

“Hooning, aggression and intimidation will absolutely not be tolerated. If you want to keep your licence, follow the rules and respect other peoples’ right to a safe day on the water,” Hutchings said at the launch of the targeted campaign.

"Waterways are for everyone to enjoy, not a playground for hoons on high-powered vessels. Those who act dangerously or flout the rules face hefty fines, loss of licence and in some cases even having your vessel impounded.”

NSW Maritime has singled out the Greater Sydney area as the part of the state with the worst locations for jet ski offences including Pittwater, Georges River, Botany Bay and Port Hacking.

During 'Operation Stay Afloat', NSW Maritime officers stressed to jetskiers a good time should be a safe time for everyone on the water. As part of the safety and educational campaign aimed at driving home the importance of responsible riding on the state’s waterways, NSW Maritime crews conducted more than 2000 vessel safety checks.

While 87% of boat and jetski operators were found to be complying with all license and safety requirements, NSW Maritime issued 186 official warnings and 81 penalty notices - 31.4% were issued for not wearing or carrying a lifejacket, 27.7% were for unlicenced drivers or unregistered vessels and 11.2% were for speeding.

It follows a year where jetski-related offences were on the rise. There were a total of 1560 jetski offences recorded in NSW during 2023, up 53% on the previous year’s 1023 jetski infringements. Speeding made up almost 30% of offences recorded.

More jetskiiers are found to be non-compliant in Sydney waters compared to other parts of NSW, with the George’s River, Botany Bay and Port Hacking taking the top spots for illegal activity leading to infringements.

The popularity of jetskis and personal watercraft has soared over the last 4 years, with over 90,000 licenced riders in NSW, an increase of over 35% since 2020. The largest jump in jetski licences has been among Generation Z, those born between 1995 and 2010. There are more than 23,000 licenced riders aged between 13 and 28 in NSW, an increase of 22% on January 2023.

The top 5 Local Government Areas for newly issued licences are Canterbury-Bankstown, Sutherland Shire, Central Coast, Lake Macquarie and the Manly to Barrenjoey peninsula.

Pittwater residents state they have witnessed jet ski operators harassing the seals that live at Barrenjoey headland, not heeding the speed limits in waterways and mooring areas, driving dangerously close to other vessels and ripping up seagrass, the nursery place for fish.

Jet ski riders harassing whales during migration season, or dolphins off local beaches, have also been reported across the Sydney basin in recent years.

Jet ski owners have argued that a big hike in fees will only force more unlicensed riders out on the water. They suggest alternatives of increasing penalties, impounding the skis of repeat offenders or those committing serious offences, and even providing more rider education before riders are handed a personal watercraft licence as a better strategy.

Under the changes, a one-year boat licence will rise from $69 to $77, and a 10-year licence will increase from $521 to $679.

The highest increase will apply to jet ski riders, who see the price of a one-year licence rise from $210 to $245, while a 10-year licence will rise from $1043 to $1961.

NSW Maritime has stated;

'The fee increase will support a range of Maritime activities, including Maritime’s on-water safety and compliance operations, and investment in critical assets to promote safe and accessible boating across NSW and key boating safety initiatives such as the Maritime Safety Plan.

Since 2014, Transport for NSW has spent $98 million on the ‘Boating Now’ Program, which has funded more than 388 projects.'

The Boating Industry Association (BIA) met with Transport for NSW officials earlier in June in an attempt to overturn the fee hikes.

BIA, which states it it represents hundreds of marine businesses and thousands of workers in the maritime industry, has said Transport for NSW had seemingly constructed the plan behind closed doors to significantly raise taxes on boating well beyond CPI to raise millions of dollars in new revenue.

BIA spokesperson Neil Patchett said, “Just a couple of years ago boating proved itself during a global pandemic as a standout option in recreation for people to experience the great outdoors and the social benefits of getting out on the water with families and friends.

“Now despite reaping the revenue rewards of increased participation through extra licences and registrations over the past few years, Transport wants to make what are already the highest boating fees in the nation, even higher.”

BIA says the massive disparity in boating licence fees in NSW compared to the neighbouring States of Queensland and Victoria is alarming.

“Boating is a way of life for many in NSW and Transport is set to make it even more expensive which runs the risk of disenfranchising young people and families from participation in what is a healthy outdoor activity with proven social benefits,” Patchett said on June 20

“We remain hopeful the Transport Minister will intervene and force Transport for NSW to reset the full schedule of fees impacting licences, registrations and moorings to be no more than CPI adjusted.”

A change.org petition has been launched by the BIA.

A new jet ski can cost anywhere from $10,000 to upwards of $30,000 in 2024, depending on its make and features.

A new jet ski can cost anywhere from $10,000 to upwards of $30,000 in 2024, depending on its make and features.

Despite being considerably cheaper than buying a boat, the price brackets for jet skis are pretty broad. For a new model, you can expect to pay anything between $5,000 and $20,000, depending on the features it has, and in some cases, far more than this.

For used and second hand models, prices obviously reduce in some cases as older models may not have the newest features.

A personal watercraft (PWC) is a vessel with a fully enclosed hull that may be driven standing up, lying down, sitting astride or kneeling, and includes jet-powered surfboards.

A special licence is required to drive one, regardless of the speed at which it's driven.

To obtain a PWC driving licence you must hold a general boat driving licence and have successfully undertaken the PWC licence knowledge test.

If you've already passed the test and completed the requirements with an Authorised Training Provider (ATP), you can post your application or take your documents to a service centre.

If you're aged 12 years or older and you hold a general boat driving licence, you can upgrade to a PWC driving licence at any time.

There are licence restrictions for people under 16.

Transport for NSW has published 'Personal Watercraft Handbook; A guide to the key PWC rules and requirements' available to download here.

The fees that will apply from 1 July 2024 are listed here:

the NSW Government has developed rules regarding aquatic wildlife.

An approach distance is the closest you can lawfully go to a whale, dolphin, dugong or seal to watch it safely and without disturbing or harassing them, so they can live naturally and without interference.

Scientists, including veterinarians, helped to develop the Biodiversity Conservation Regulation 2017, which outlines the approach distances for New South Wales. These are based on The Australian National Guidelines for Whale and Dolphin Watching 2017 and also includes seals.

Remember, if a marine mammal approaches you, slowly move back to at least the minimum approach distance. Never chase it; try to touch it or restrict its path. On a rare occasion, a National Parks and Wildlife Service officer may ask you to move back beyond the minimum approach distance if they see an animal is still distressed and behaving as if it is disturbed.

By observing the following approach distances, you can have a safe and enjoyable time while helping to keep our wildlife wild.

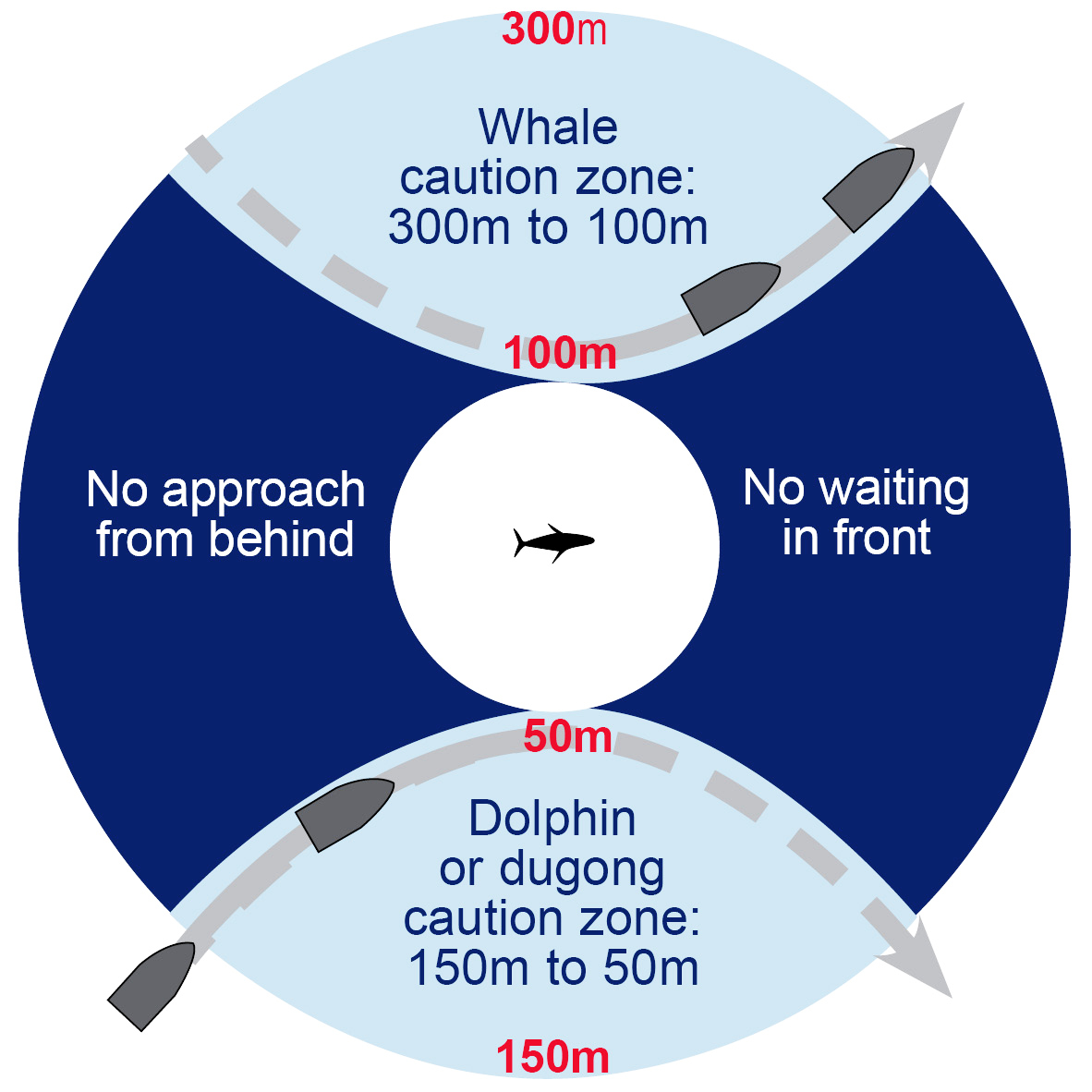

Under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Regulation 2017 all watercraft, including boats, surfboards, surf skis and kayaks must stay at least 100 m from a whale, and ths increases to at least 300m if a calf is present.

Restrictions also apply to swimmers, snorkellers, divers and those in the water, who must stay at least 30 m from a whale. There are also restrictions for aircraft, including drones.

From May to November each year, humpback whales make their annual migration from Antarctic waters to Queensland to calve, while southern right whales tend to stay in NSW’s protected bays and beaches to nurture their young.

Signs of disturbance

Disturbed whales, dolphins, dugongs and seals react with a sudden change of behaviour, including:

- hastily diving

- vocalising

- changes in breathing patterns

- sudden change in body posture or positioning

- a sudden change in direction

- a change in swimming speed

- aggressive behaviour such as tail splashing, head lunges and charging

- protectively moving between you and their young.

If you see someone intentionally harming, touching, harassing, chasing, trying to restrict the path of a marine mammal, or getting too close, please report the illegal activity to National Parks and Wildlife on 13000PARKS (1300 072 757).

Approach distance

An approach distance is the closest you can lawfully go to a whale, dolphin, dugong or seal to watch it safely and without disturbing or harassing them, so they can live naturally and without interference.

Scientists, including veterinarians, helped to develop the Biodiversity Conservation Regulation 2017, which outlines the approach distances for New South Wales. These are based on The Australian National Guidelines for Whale and Dolphin Watching 2017 and also includes seals.

Remember, if a marine mammal approaches you, slowly move back to at least the minimum approach distance. Never chase it; try to touch it or restrict its path. On a rare occasion, a National Parks and Wildlife Service officer may ask you to move back beyond the minimum approach distance if they see an animal is still distressed and behaving as if it is disturbed.

By observing the following approach distances, you can have a safe and enjoyable time while helping to keep our wildlife wild.

Whales, dolphins dugongs

The approach distance is determined by the activity you are doing, either in the air, or in or on water, the type of animal and if there is a calf present.

The exception is when a whale, dolphin or dugong that is mostly white in colour is present. You must always stay at least 500 metres from them.

Approaching when in the water – swimmers, snorkelers and divers

If you are a swimmer, snorkeler or diver, to observe a marine mammal, you may enter the water at a minimum distance of:

- 100 metres away from a whale

- 50 metres from a dolphin or dugong.

If you are in the water, you must keep at least:

- 30 metres from a whale, dolphin or dugong, including a calf.

For reference, 30 metres in length is approximately the same length as:

- an official basketball court

- 2 public transport buses lined up end to end.

Approaching on the water – boats and surfboards

A vessel is watercraft that can be used as transport, including motorised or non-motorised boats, surfboards, surf skis and kayaks.

If you are on the water in a vessel you are not permitted to approach a marine mammal from behind or wait in front of it.

If a calf is present, you are not permitted to enter the caution zone for closer viewing. The caution zone boundary is 300 metres for whales and 150 metres for dolphins and dugongs.

You must comply with the following approach rules:

A vessel is in the caution zone when it is:

- 300 metres from a whale

- 150 metres from a dolphin or dugong.

A vessel can move no closer than:

- 100 metres to a whale

- 50 metres to a dolphin or dugong.

In the caution zone the skipper must:

- post a lookout if 2 or more people are on board

- not position the vessel ahead of the animal to wait for it

- approach from the side at least 30 degrees to its direction of travel

- move at a constant slow speed with negligible wake – when the waves created by the movement of the prohibited vessel are so small that if there was a boat nearby it would not move

- only 3 vessels are permitted to be in the entire caution zone at any one time – other vessels must wait their turn, regardless of size and not drift closer.

If dolphins are bow-riding, you must maintain course and speed.

If a whale approaches, slow down to minimal wash speed, move away or disengage gears and do not make sudden movements.

Approaching on the water – prohibited vessels

Prohibited vessels include personal motorised watercraft (jet skis), parasail boats, hovercraft, hydrofoils, wing-in-ground effect craft, remotely operated craft or motorised diving aids like underwater scooters.

These vessels are prohibited because they can make fast and erratic movements and not much noise underwater, so there is more chance they may collide with a marine mammal.

If you are approaching a marine mammal using a jet ski or other prohibited vessel you must have negligible wake and stay at least 300 metres from a whale, dolphin or dugong.

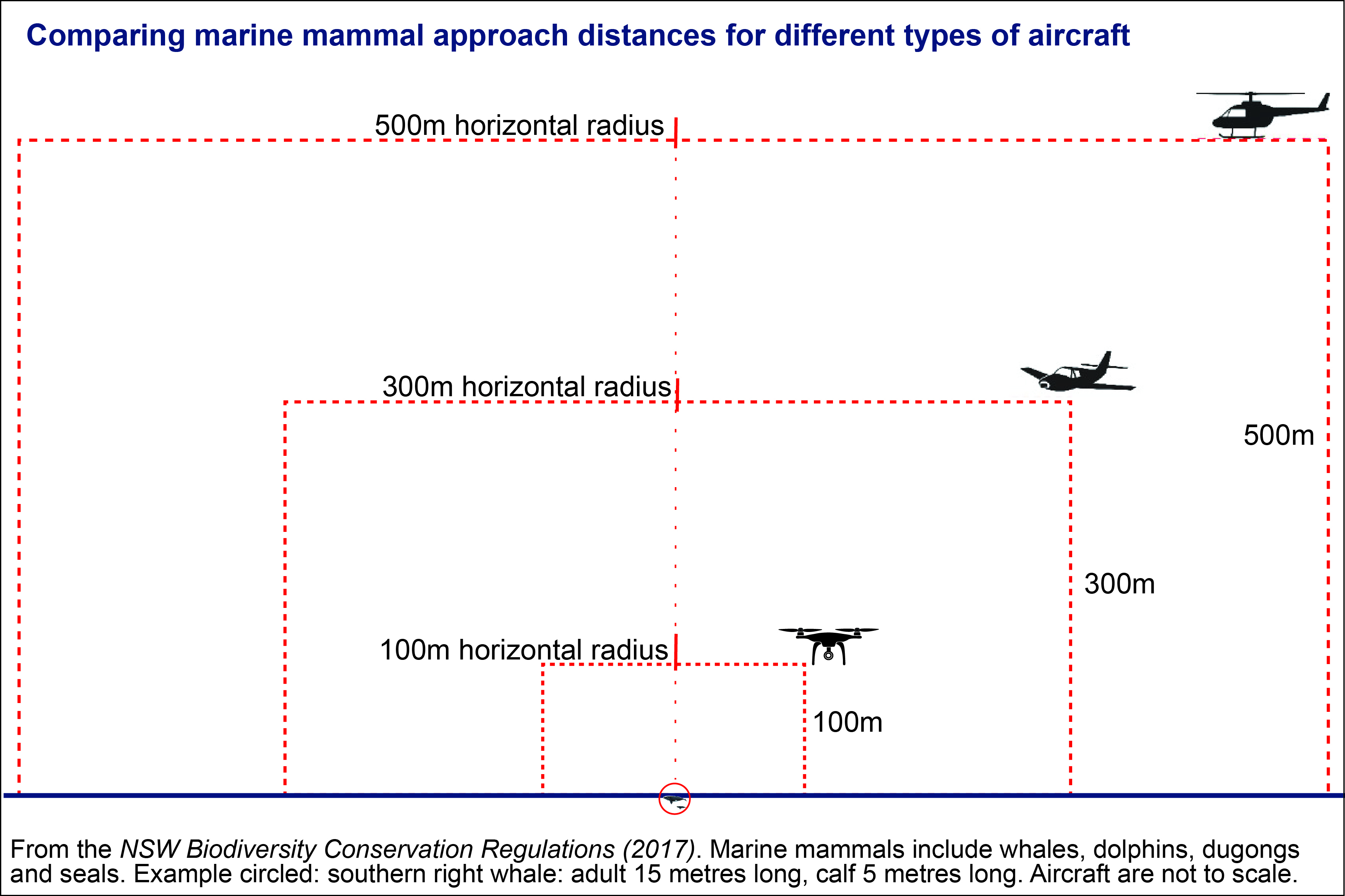

Approaching from the air – aircraft including drones

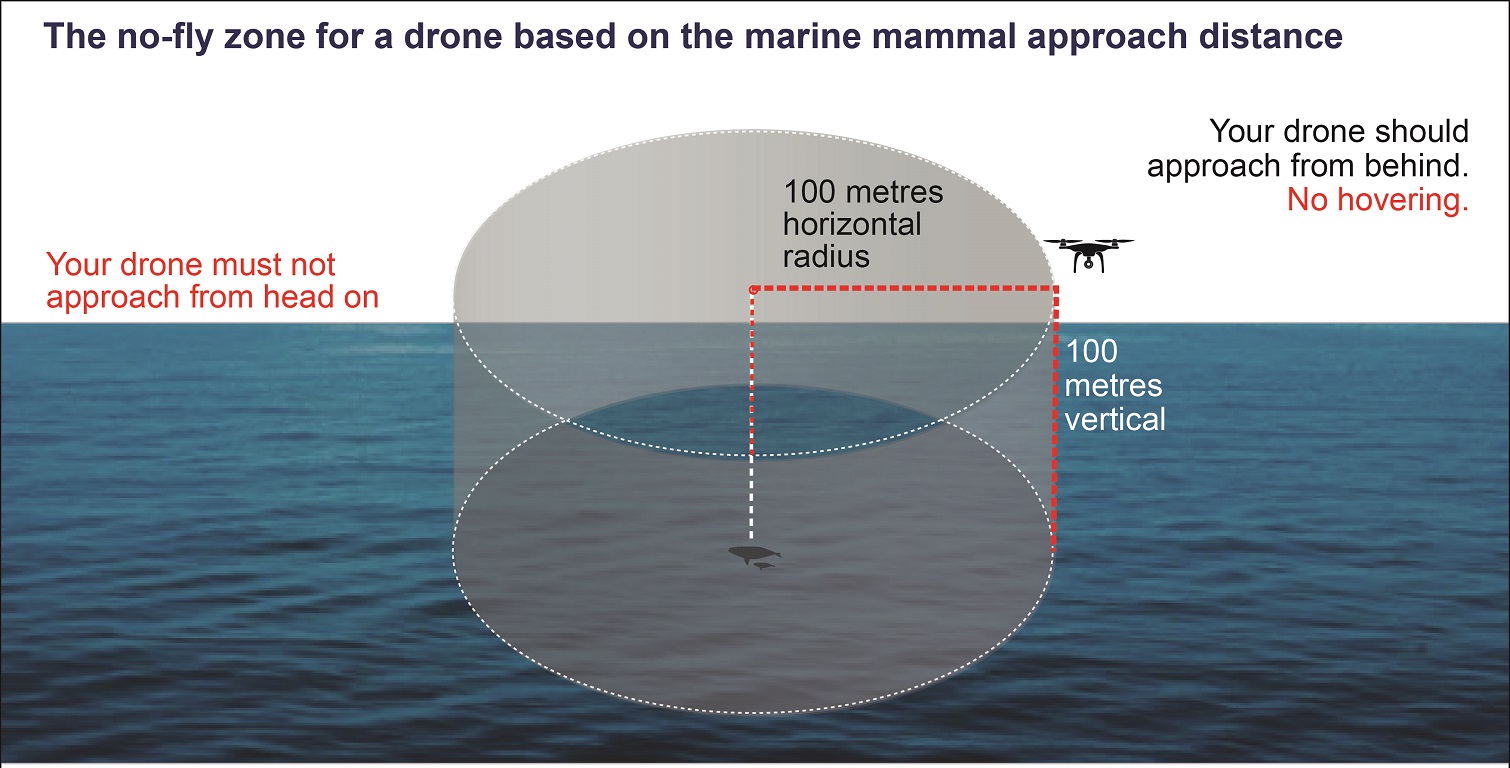

To observe a marine mammal from the air, you must approach it from behind, not hover over it and not land on the water to observe it. The pilot must also comply with Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) requirements.

The approach distances for different types of aircraft are:

- 100 metres for drones (also known as RPAs and UAVs)

- 300 metres for fixed-wing aircraft

- 500 metres for helicopters and gyrocopters.

The approach distance for aircraft is the height above a marine mammal and the horizontal distance away from it.

If you go closer than the approach distance, you have entered the no-fly zone. The no-fly zone for aircraft over a marine mammal can be imagined as an approach distance cylinder.

The 'no-fly zone' is shaped like a cylinder and moves with the whale, dolphin, dugong or seal. A drone can fly a minimum of 100 metres vertically over, and 100 metres horizontally around a marine mammal. A drone is not permitted to cut through the no-fly space. The aircraft is not to scale. Based on NSW Biodiversity Conservation Regulations (2017).

A drone pilot needs skill, understanding of the regulations and environmental awareness to lawfully approach a marine mammal. The drone pilot must always be in visual line of sight with the drone, not create any hazards and not cause harm to wildlife.

Listen for wildlife distress calls. If birds are disturbed, the pilot is advised to abandon the flight for 5 minutes, land and consider an alternate launch site or wait until birds of prey have left the area, or nesting birds have resettled, then try again.

Seek permission to launch from the landholder or land manager and follow all instructions. Do not launch from or fly over a national park without permission.

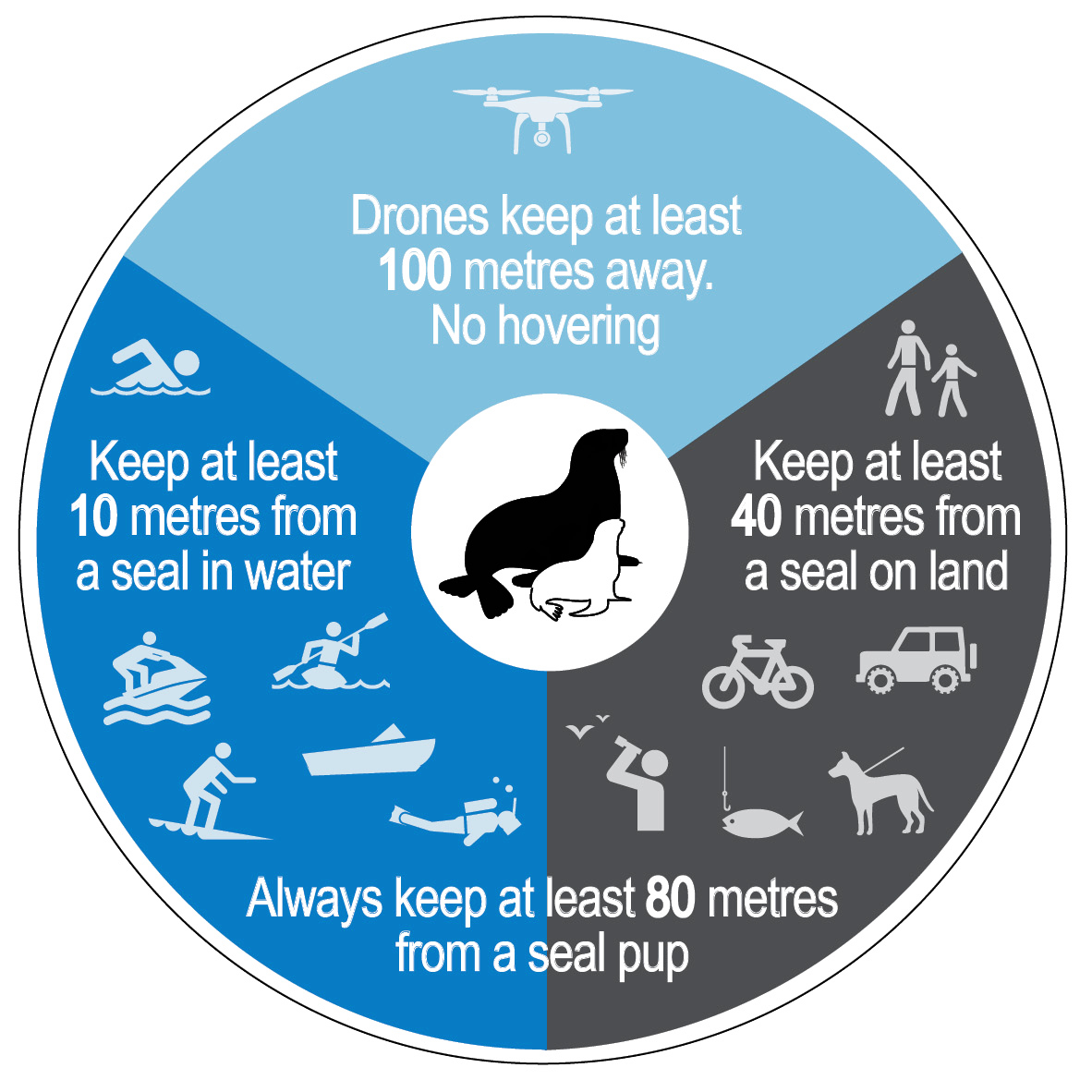

Seals

A seal may look like it is yawning but is actually baring its teeth as a warning sign.

Approach distances for seals are based on where the seal is located and if a pup is present. A seal is considered a pup if it is up to half the length of the adult.

If a seal comes towards you, you must move back to the minimum approach distance.

Approaching a seal when it is in the water

Seals are agile swimmers with strong flippers. When a seal is in the water you must keep at least:

- 10 metres away from the seal

- 80 metres from a seal pup

- 100 metres for a drone.

If you are also in or on the water and a seal approaches you, stay calm and move away slowly. If bitten or scratched, seek immediate medical advice.

Approaching a seal when it is hauled out on land

Seals haul out to rest after foraging at sea.

If a seal feels threatened, it may show aggression by yawning, waving its front flipper or head, or calling out. Seals are very agile and can move fast on land, using all 4 limbs to run. When a seal is hauled out on the land you must keep at least:

- 40 metres away from the seal

- 80 metres from a seal pup

- 100 metres away from the seal for a drone.

Seals can often have injuries that look quite alarming but will heal well without needing veterinary assistance.

If you are concerned call National Parks and Wildlife on 13000 PARKS (1300 072 757), or Organisation for the Rescue and Research of Cetaceans in Australia on 02 9415 3333 for the animal to be checked and monitored.

Vessels watching seals resting on the rocky shore must also keep back 40 metres or 80 metres if a pup is present. Limit the time you spend watching because it can be stressful for them. It is likely you are not the only vessel to approach them that day.

For more information on approach distances, please visit the NSW Environment website.

For information on whale watching vantage points along the South Coast’s National Parks and Reserves, visit the NPWS website.

Keep your dog restrained

With marine mammal populations slowly recovering in New South Wales, there is an increased chance that you will come across one when walking on a break wall or jetty. Keep your dog on a leash to avoid an unexpected encounter. This will reduce stress for the animal and reduce the chance of your dog being bitten. Dogs can transfer diseases to seals and vice versa.

A reminder that it is illegal to take dogs into National Parks.

Entangled whale, dolphin or seal

If you see an entangled animal:

- Watch from a distance, do not approach or enter the water or attempt to disentangle it.

- Immediately report it to:

- National Parks and Wildlife on 13000 PARKS (1300 072 757)

- Organisation for the Rescue and Research of Cetaceans in Australia on 02 9415 3333

Note the time, your location, the whale's direction of travel and speed.

Observe from a safe distance to:

- look for injuries and identifying marks

- take photographs of the entangling material to help rescuers bring the most suitable gear to remove it

- try to keep watch until help arrives.

Infographics: NSW Dept. of Environment