The face of the water, in time, became a wonderful book—a book that was a dead language to the uneducated passenger, but which told its mind to me without reserve, delivering its most cherished secrets as clearly as if it uttered them with a voice. And it was not a book to be read once and thrown aside, for it had a new story to tell every day. - Mark Twain

For several years the rumour that Mark Twain visited our area has persisted in tales of a fishing trip to Manly with J. F. Archibald. Henry Lawson also figures in the 'tale', and asked by Archibald to keep supplying live fish to Twain's line from a hidden crevice below where they fished from.

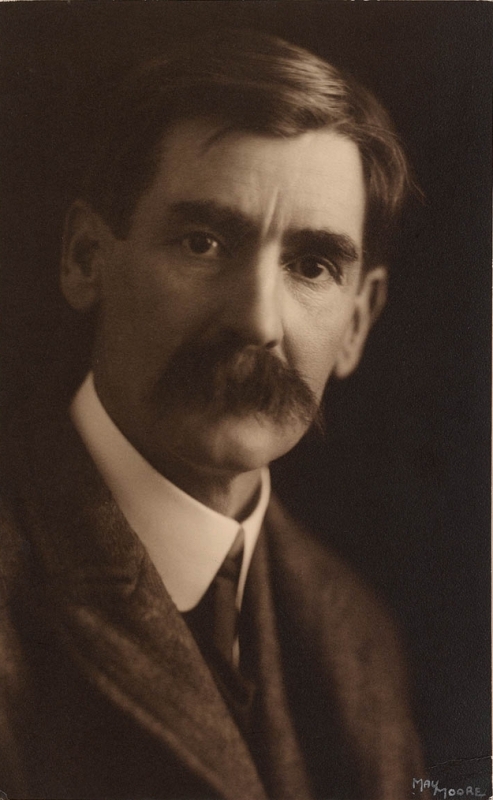

J. F. Archibald was a keen promoter and supporter of Henry Lawson through The Bulletin.

Following other threads, from which it is recorded that when Henry Lawson heard Mark Twain on his speaking tour in Sydney of September 1895, 'the young poet, seated in the front row, banged the stage so hard in enthusiasm that the white hair of the old American shook' it is also asserted and that the two dined together in Sydney.

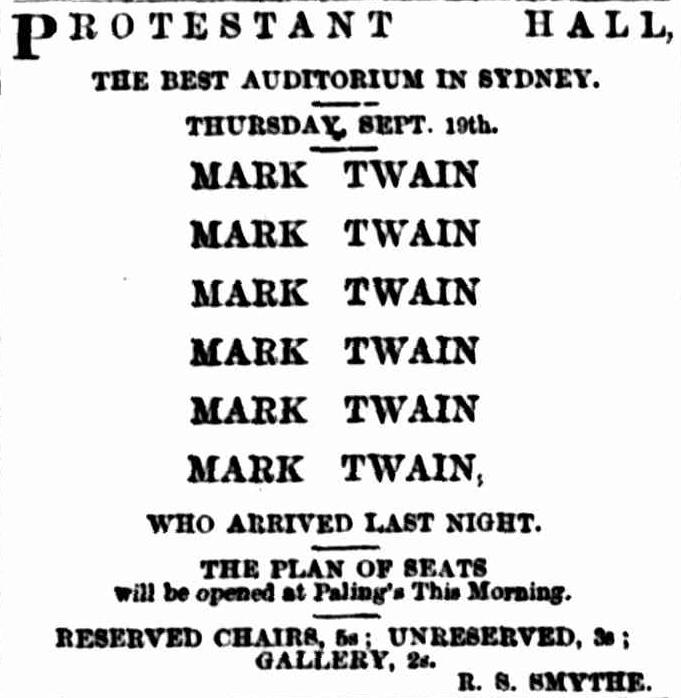

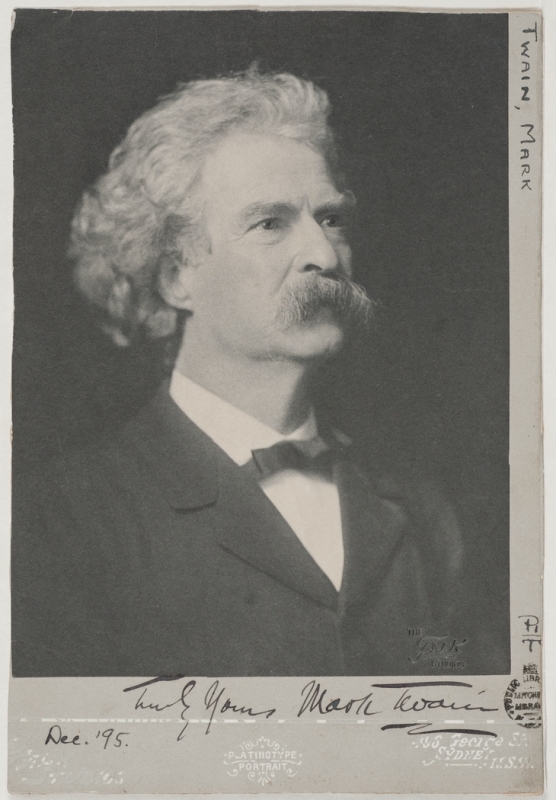

Mark Twain's first public engagement:

This appears in the same paper two days afterwards:

A LECTURE ON HENRY LAWSON.

Mr. J. Le Gay Brereton, last night at the small hall in the School of Arts, delivered a lecture on Henry Lawson, the Australian poet. He was assisted by Messrs. Teece and Moses, who recited pieces from the works of the poet. The lecturer said that Lawson had the poetic faculty in a high degree, and as his judgement developed and his style matured would improve. A LECTURE ON HENRY LAWSON. (

1895, September 18 - Wednesday).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 6. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14017257

On the evening of the 18th:

Mark Twain.

Few will need reminding that America's great humorist addresses an Australian audience for the first time this evening. The lecture will be delivered in the Protestant Hall, and the subject is to be 'Knights of Wit and Humor.' The booking in advance has been excellent, and there is certain to be a good attendance, while it is equally certain that the remarks of so witty and practised a speaker as Mr. Clemens will be about as entertaining as platform utterances can be made. The members of the Athenaeum Club last night entertained Mark Twain at dinner, and there was a good and representative gathering. The Hon. E. Barton presided, and the guest, in response to the toast of his health, made one of iris humorous speeches, and concluded by proposing the sentiment 'Advance Australia,' which was responded to by Sir Henry Parkes, Sir. W. Windeyer, and the Hon. J. Want'.Mark Twain (1895, September 19). Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article109885278

NB: - other sources state this first presentation was 'Nights of Wit and Humour'.

from Chapter 28, An evening with Mark Twain, extracts from pages 273 to 274, of Faces in the Street :

“Heh heh,” he continues, “as many of you will know, I am Vice President of the American Anti-Imperialist League, which the Cincinatti Observer misspelled as the ‘South Carolina Pickle-Bottling Society’.”

Henry is now standing and leaning forward against the stage, rocking and laughing and whooping and turning around to Jack and to the crowd to nod and laugh and join in their exquisite merriment. He pounds his hands on the stage so strongly that they will hurt in the morning, and the old man’s white locks almost shake with the floorboards.

“Well, this young fella thought it was funny, anyway,” Mark Twain says laconically. “What’s your moniker, young man? I do like your moustache! It reminds me of one I saw in my mirror – about thirty or forty years ago.”

Henry looks behind him, but he can see by the faces in the glare of the footlights that the question was directed to him.

“Henry Lawson,” comes the nervous reply, and the crowd cheers and applauds as loudly as before.

“Well, by gee, by the sound of that acclamation, and this being Sydney, you must be a sportsman, am I correct?”

“No, sir.”

“Then you must be a lawyer and involved in the Lemon Syrup Case that threatens to out-publicize my tour,” Mark Twain says to applause. “It

seems every man in this town is involved – you’re not Mr Crick or Mr Meagher, are you?”

“No, sir, I’m a writer.”

“Oh, I’m truly sorry to hear— no, I’m jesting, sir. I know, sir, I know that you are a writer. I hope you will excuse my jest. I recall you as one of the ‘faces in the street’ from my ‘days when the world was wide’.”

Henry is overwhelmed and salutes and quickly sits down low in the green upholstered seat, but Jack forces him to turn around again and take the bow that the audience so uproariously demands.

And so, this is how it came to be that Henry Lawson first heard the phrase, “Truth is more of a stranger than fiction”, with Jack Brereton, Samuel Langhorne Clemens and Mr Jim Beam, later that night, in Mark Twain’s room at the Athenaeum Club.

“Ahhh, gentlemen!” says Mark Twain as he slumps into a plush leather chair and loosens his tie. “Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over. I said that.”

From - Faces in the Street

Louisa and Henry Lawson

and the Castlereagh Street Push

By Pip Wilson. 2007 - available HERE

In Down Under Day by Day with Mark Twain, from the Mark Twain Journal, Vol. 33, No. 2 (FALL, 1995), pp. 6-34 reference is indeed made to Clemens fishing with Archibald - only this is stated as 'spent many pleasant hours during his too short stay', between September 21-24, 1895, fishing with J. F. Archibald at his cottage at Cronulla. To wit:

For many years Archibald had a week-end cottage at Cronulla. There among his pots and pans he would entertain. Poets and artists, who as freelances ate for the most part at counter lunches, were regaled by Archie with turkey and champagne. "A change of diet," he said, "is good for everyone."

Some week-ends his guests would be Jack Want, leader of the Bar, Toby Barton and the bon vivants of the day. "I'd give them corn beef, pot-atoes and beer," Archie told, adding with a chuckle, "A change of diet is good for everyone."

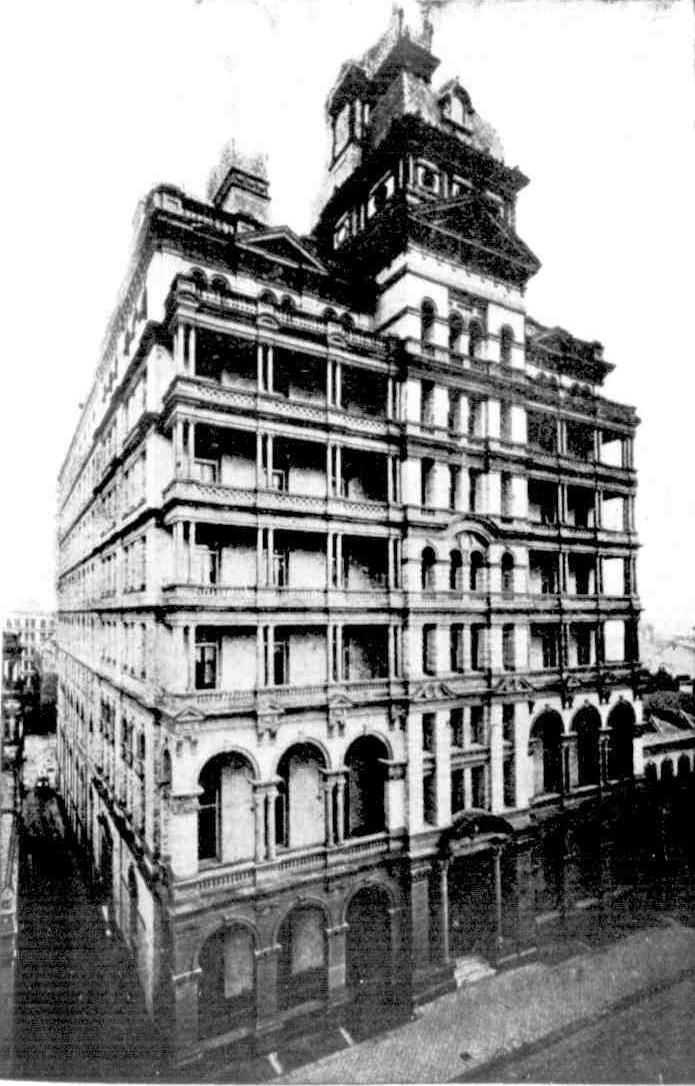

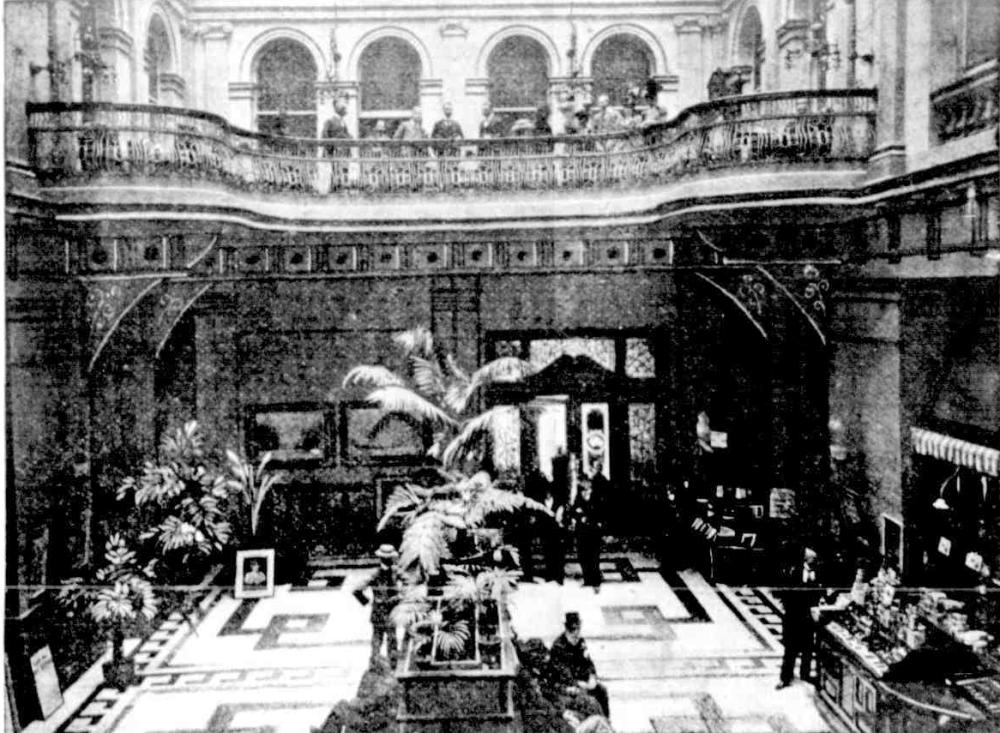

His companions on these latter occasions were all members of the old Athenaeum Club, then the haunt of wit and learning. The quality of the speeches at a dinner given to Lord Rosebery on his one visit to Australia so captivated him that he bought the building and leased it to the club at a peppercorn rental.

But whether the intellectual pressure was too great to be sustained or not, the fact is that the Athenaeum lost its pristine glory. When I had entered its portals members were housed in a couple of rooms in Martin Place. Archie took me there. Looking around, he said, "This Club was founded as a literary and artistic club. The only literary effort you are likely to see here today is someone writing a check and the only artistic effort is getting it cash

These journals also note that he stayed at the Australia Hotel,

opened June 19, 1891, which also had an entrance on Castlereagh street and frontage to Rowe street. Lawson had removed to John McGrath's

Edinburgh Castle Hotel in 1895, corner of Bathurst and Pitt streets.

It would seem Samuel Clemens, a man of letters who kept notes and journals, would have written down the name of the place correctly though - In Following the Equator - A journey around the world by Mark Twain, SAMUEL L. CLEMENS, HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT(published 1897) he lists the names of places he visited and his attempt to weave these wonderful and song-like Australian place-names into a poem.

This report, days after his departure from Melbourne for India, may be where all the conjecture began:

MARK TWAIN An Incident of his Stay in Sydney.

Mark Twain, the American humorist, confided to a few intimates just on the eve of his departure from Melbourne, that the 'pleasantest afternoon he had, spent in Australia was devoted to a fishing expedition with Archibald, of the Sydney 'Bulletin,' down at a place called Narrabeen.'

Then Mark shook his hyacinthine locks and was convulsed with nasal laughter.

‘Don’t ask me anything about it, boys; it's going to be the plum of my book. Wild horses won't draw it out of Archibald, so there's something for you to wonder over for a few months. So long I' MARK TWAIN. (

1896, January 5).

Truth (Sydney, NSW : 1894 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169755516 "Why, there’s two of them, and they’re having a fight! Come on.”’

It seemed a strange place for a fight — that hot, lonely, cotton-bush plain. And yet not more than half a mile ahead there were apparently two men struggling together on the track.

The three travellers postponed their smoke-ho and hurried on. They were shearers — a little man and a big man, known respectively as “Sunlight” and “Macquarie,” and a tall, thin, young jackeroo whom they called “Milky.”

“I wonder where the other man sprang from? I didn’t see him before,” said Sunlight.

“He muster bin layin’ down in the bushes,” said Macquarie. “They’re goin’ at it proper, too. Come on! Hurry up and see the fun!”

They hurried on.

“It’s a funny-lookin’ feller, the other feller,” panted Milky. “He don’t seem to have no head. Look! he’s down — they’re both down! They must ha’ clinched on the ground. No! they’re up an’ at it again. . . . Why, good Lord! I think the other’s a woman!”

“My oath! so it is!” yelled Sunlight. “Look! the brute’s got her down again! He’s kickin’ her. Come on, chaps; come on, or he’ll do for her!”

They dropped swags, water-bags and all, and raced forward; but presently Sunlight, who had the best eyes, slackened his pace and dropped behind. His mates glanced back at his face, saw a peculiar expression there, looked ahead again, and then dropped into a walk.

They reached the scene of the trouble, and there stood a little withered old man by the track, with his arms folded close up under his chin; he was dressed mostly in calico patches; and half a dozen corks, suspended on bits of string from the brim of his hat, dangled before his bleared optics to scare away the flies. He was scowling malignantly at a stout, dumpy swag which lay in the middle of the track.

“Well, old Rats, what’s the trouble?” asked Sunlight.

“Oh, nothing, nothing,” answered the old man, without looking round. “I fell out with my swag, that’s all. He knocked me down, but I’ve settled him.”

“But look here,” said Sunlight, winking at his mates, “we saw you jump on him when he was down. That ain’t fair, you know.”

“But you didn’t see it all,” cried Rats, getting excited. “He hit me down first! And look here, I’ll fight him again for nothing, and you can see fair play.”

They talked awhile; then Sunlight proposed to second the swag, while his mate supported the old man, and after some persuasion, Milky agreed, for the sake of the lark, to act as time-keeper and referee.

Rats entered into the spirit of the thing; he stripped to the waist, and while he was getting ready the travellers pretended to bet on the result.

Macquarie took his place behind the old man, and Sunlight up-ended the swag. Rats shaped and danced round; then he rushed, feinted, ducked, retreated, darted in once more, and suddenly went down like a shot on the broad of his back. No actor could have done it better; he went down from that imaginary blow as if a cannon-ball had struck him in the forehead.

Milky called time, and the old man came up, looking shaky. However, he got in a tremendous blow which knocked the swag into the bushes.

Several rounds followed with varying success.

The men pretended to get more and more excited, and betted freely; and Rats did his best. At last they got tired of the fun, Sunlight let the swag lie after Milky called time, and the jackaroo awarded the fight to Rats. They pretended to hand over the stakes, and then went back for their swags, while the old man put on his shirt.

Then he calmed down, carried his swag to the side of the track, sat down on it and talked rationally about bush matters for a while; but presently he grew silent and began to feel his muscles and smile idiotically.

“Can you len’ us a bit o’ meat?” said he suddenly.

They spared him half a pound; but he said he didn’t want it all, and cut off about an ounce, which he laid on the end of his swag. Then he took the lid off his billy and produced a fishing-line. He baited the hook, threw the line across the track, and waited for a bite. Soon he got deeply interested in the line, jerked it once or twice, and drew it in rapidly. The bait had been rubbed off in the grass. The old man regarded the hook disgustedly.

“Look at that!” he cried. “I had him, only I was in such a hurry. I should ha’ played him a little more.”

Next time he was more careful. He drew the line in warily, grabbed an imaginary fish and laid it down on the grass. Sunlight and Co. were greatly interested by this time.

“Wot yer think o’ that?” asked Rats. “It weighs thirty pound if it weighs an ounce! Wot yer think o’ that for a cod? The hook’s half-way down his blessed gullet!”

He caught several cod and a bream while they were there, and invited them to camp and have tea with him. But they wished to reach a certain shed next day, so — after the ancient had borrowed about a pound of meat for bait — they went on, and left him fishing contentedly.

But first Sunlight went down into his pocket and came up with half a crown, which he gave to the old man, along with some tucker. “You’d best push on to the water before dark, old chap,” he said, kindly.

When they turned their heads again, Rats was still fishing but when they looked back for the last time before entering the timber, he was having another row with his swag; and Sunlight reckoned that the trouble arose out of some lies which the swag had been telling about the bigger fish it caught.'

In December 1894 Lawson's Short Stories in Prose and Verse was released. In 1895 he contracted to publish two books with Angus & Robertson and these were released in 1896; In the Days when the World was Wide and other Verses and While the Billy Boils. While the Billy Boils went on to be a successful stage play, despite Mr. Lawson's reservations:

LAWSON'S DREAM

Henry Lawson has been having restless nights lately apparently over the play "While the Billy Boils," which was staged at the Theatre Royal last night. He sends the following to Beaumont Smith: "I had a peculiar dream, or call it a nightmare, the other night — I thought I was fishing on the river in the gnarled old bush out here; when, suddenly there came some white faced people running, with a lot of terrible rough characters after them. Dream-Instinct told me It was part of a theatrical company, and part of an Infuriated Sydney audience. Then, suddenly, nightmare-instinct told me that they were after me too — and I was streaking further west when I woke up." LAWSON'S DREAM (1916, October 1). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 18. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article223359527 Mr. Lawson mentions Mark Twain in his Autobiographical writings (some volumes have been digitised by the State Library of NSW) and clearly was a fan as his own methods frequently employed humour, pathos and communicated a love of all humanity and a laughing at pompous fools who thought themselves in charge or displayed less liked human traits such as race prejudice - something Lawson and Clemens had in common, in all their works. The tone in Lawson's journals is that of a friend of some acquaintance, which was his nature in any case, as it was, in same, with Clemens.

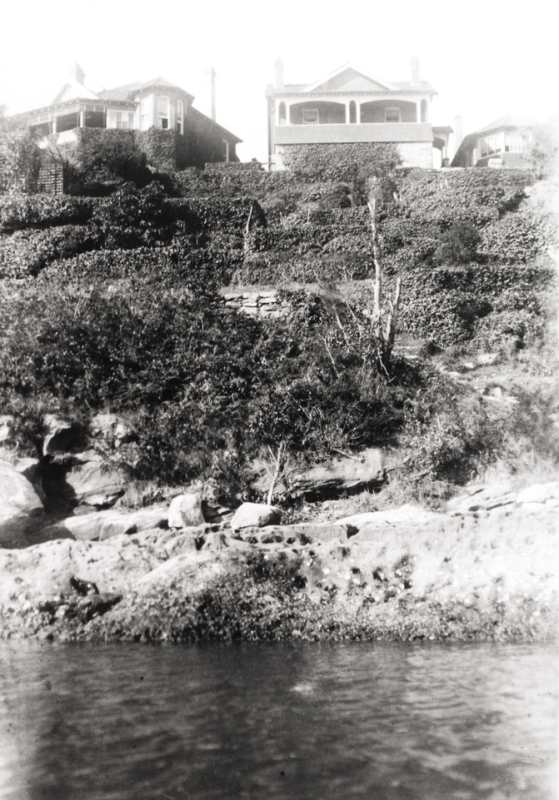

Henry Lawson certainly had friends in Manly during 1895 too, one of whom, Charles Lind, tragically took his own life and left a letter addressed to Lawson, which is recorded by numerous newspapers in 1896. The Australian poet would certainly have known about Narrabeen and its by then quite famous fishing grounds.

Henry Lawson also resided at Manly after his return from England

GRIMY OLD BABYLON.

HENRY LAWSON'S APPRECIATION. (From the "Sydney Daily Telegraph.")

"Yes, I like London, "said Mr. Henry Lawson, the Australian bush idyllist, with a light of pleasure on his earnest face, as he drew his chair up before the fire for a chat and a smoke. Having lately returned from England, Mr. Lawson has settled, at least for the present, in a little snuggery edging on to the ocean beach at Manly. His memories of London are still fresh and rapturous. " For the first few months the monotony and loneliness of London was worse to me than the monotony and loneliness of the bush. But then I found friends, and began to learn my London, and I have grown fond of the grimy old Babylon. " You've read Newbolt's poem : 'It is London, it is London ! and it calls ?' Well, when you've lived a couple of years in London, as I have, and come away, you will understand how London calls. " Still, I was glad to start for home. There was the novelty and excitement of it, and I kept on being glad until—well, until, strange to say, about the time we crossed the line. Then—well, London began to call, if you understand. "To put it simply, when I came to Sidney from the hush, Sydney spoilt me for die bush—l couldn't lire in the country now; I feel twice the man when I set my feet on pavements—and London has spoilt me for Sydney. 8I suppose London has got me—and will bury me in the end, I fancy. "What struck me first and most In England was the astounding ignorance of the English people an all matters connected with Australia, or, indeed, with any other British possession beyond the seas. I never actually met an Englishman or Englishwoman who thought that we Australians were black, though I did meet a German lady who was firmly convinced of it, and who set me down at once aa a fraud. "But I have met people who were surprised to hear me speak such good English and I have been asked by fairly intelligent Englishmen if we had a common language out there. Our first landlady said to me, 'Why, I never would have thought that you were an Australian, Mr. Lawson —she had never seen one, nor been out of England—and she said she always thought we were much danker, and spoke 'Spanish, or something.' I suppose the name of Australia gave her that idea. "No, we know infinitely more about England than England knows about Australia. That is because we learn England from English people who come out here—there's little emigration from Australia to England-and. above all, from the shoal of English illustrated magazines. " Another thing that surprised me, and discouraged me, and made me homesick at the time, was to travel for an hour in a railway carriage with nine Englishmen, who never spoke a word to each other. I thought they were only waiting for someone to break the Ice —to give a lead, so to speak—and so I started to talk. But they answered me in words of one syllalble, and put up their papers, and seemed to regard me with disfavour and distrust. They seemed irritated, and annoyed, too, and I couldn't make out what I'd said or done to offend 'em. Australians would be friendly and joking and laughing before the train started....GRIMY OLD BABYLON. (

1902, August 30).

The Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 - 1939), p. 475 (unknown). Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21627642

This new dwelling at Manly was not without mishap. This incident occurred during a time of heavy drinking by the Australian legend and when he was having marital problems with his wife Bertha:

ACCIDENT TO MR. HENRY LAWSON.

Shortly after 10 o'clock on Saturday morning a fisherman named Sly, while walking along the cliffs at Manly, noticed a man lying near the water's edge. Sly climbed down a path which is used by fishermen, and found that the man was Mr. Henry Lawson, poet and story-writer. He was quickly carried to the top of the cliffs, and Dr. Hall, who was summoned, found that Mr. Lawson was suffering from a broken ankle, a lacerated wound over the right eye, besides other injuries. It was ascertained that Mr. Lawson had fallen over the cliffs, which at that place are about 80 or 90ft. high. He was conveyed

And another Lawson at Manly recollection, only years afterwards;

Henry Lawson.

As before stated — and memory revived by the late pilgrimage to his grave. I also met and knew the late Henry Lawson many years ago while living at Manly, and spent some very pleasant times in his company. We would meet of an evening, stroll round, and stop one occasionally. I found him a genial boon companion., inclined to be reserved, enjoying himself in his own quiet way. He and the late Phil May were great friends, and both very much attached to each other. Both now have gone the way of all flesh. He, as is well known, was born at Grenfell, being the son of the late Peter Hertzberg Larsen, a Norwegian, his mother being Louisa Albury, a native of New South Wales. He worked with his father as a boy and went to Sydney at the age of 17, learning the trade of a coach painter. He commenced writing verses when he was 20, and was on the staff of several papers. He travelled extensively in New South Wales, West Australia and New Zealand, engaging in various occupations, and died in Sydney in poor circumstances, being accorded a State funeral. It is mooted to erect a statue of him in the Sydney Domain near that of Bobbie Burns. The Sydney 'Bul-letin' is a great supporter. The late Mr. Archibald, of that paper, was one of Lawson's best friends. A Norwegian has just lately completed a version of Lawson's poems into Norwegian for circulation in that country. I quote a verse or two from here and there: —

'The Drover.'

Our Andy's gone to battle now

'Gainst drought, the red marauder,

Our Andy's gone with, cattle now

Across the Queensland border. '

Oh, may the showers in torrents fall,

And all the tanks run over,

And may the grass grow green and tall

In pathways of the Drover.

And may good angels send the rain

On desert stretches sandy,

And when the summer comes again

God grant 'twill bring us Andy.

'Out Back.'

For time means tucker, and tramp you must where the scrubs and plains are wide,

With seldom a track that a man can trust, or a mountain peak to guide,

All day long in the dust and heat— ,

When summer is on the track,

With stinted stomachs and blistered feet,

They carry their swags Out Back

'The Vagabond.'

A rolling stone! — 'tis a saw for slaves —

Philosophy false as old,

Wear out or break 'neath the feet of knaves,

Or rot in your bed of mould.

Cleave to your country, home and friend,

Die in a sordid strife,

You can count your friends on your finger ends,

In the critical hours of life.

Sacrifice all for the family's sake,

Bow to their selfish rule!

Slave till your soft heart they break

The heart of the family, fool.

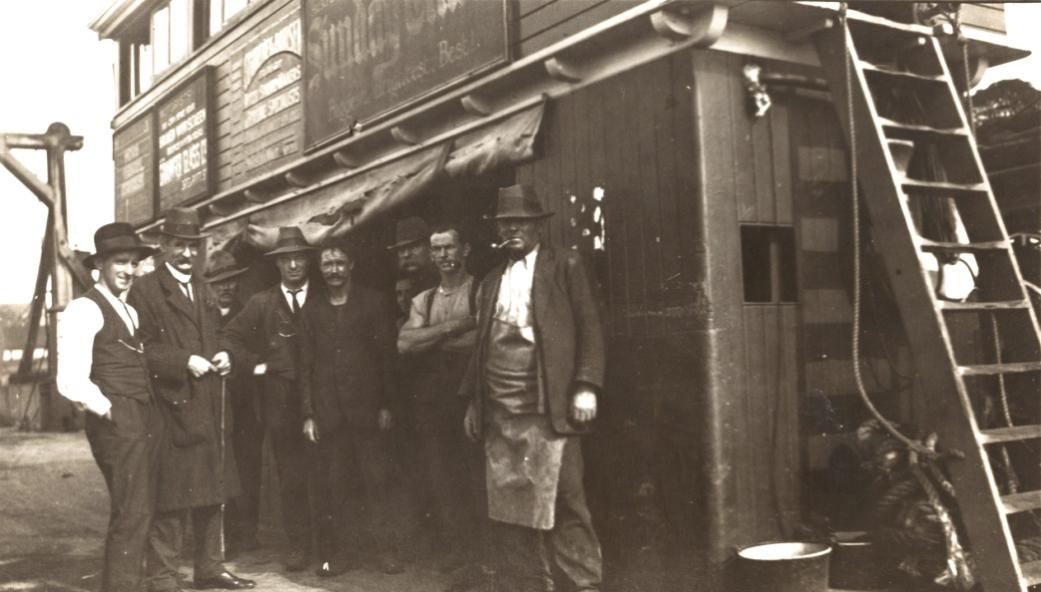

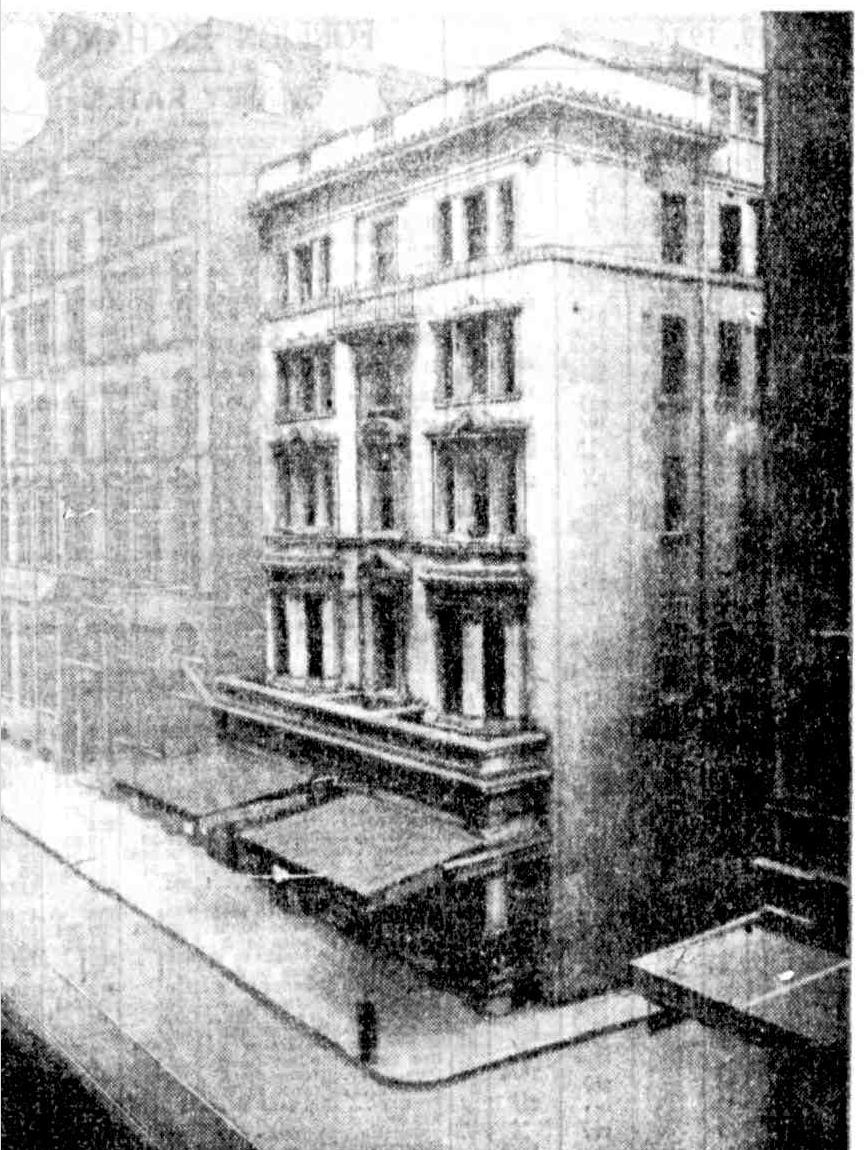

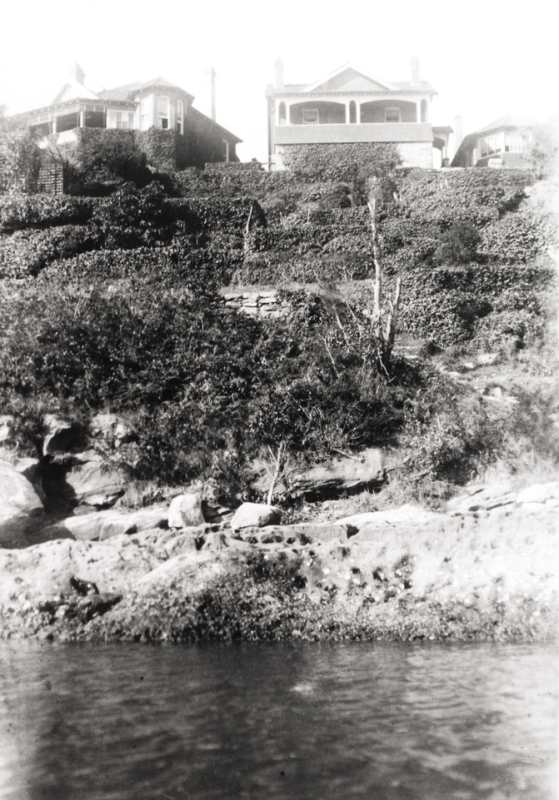

Untitled houses, possibly residences of Henry Lawson, from album:

Henry Lawson's funeral at Waverley Cemetery, September 1922, Digital Order Number: a6134008, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

To get at the truth behind the remark from Mr. Clemens own lips regarding a laughing matter during a fishing trip to Narrabeen we must resort to poring through the pages of those who knew more intimately the third mentioned member of this so-called 'party - J F Archibald, born and christened, John Feltham, who had a deep passion for all things French, and changed his name to Jules François, most well known for that fountain in Hyde Park and being one of the founders of the Bulletin with John Haynes.

An extract from one who knew him for decades in a tribute after he had passed away on Archibald living at Manly and frequently walking to Narrabeen to fish comes from the pen of Fred. J. Broomfield as part of - In Memoriam: Jules Francois Archibald:

He was characteristically retiring, and had a constitutional objection to 'crowds' of even moderate dimensions. Indeed, he abhorred sitting still, if sitting still involved doing nothing, and he did not like listening if he could not answer. Hence the theatre or the concert hall bored him. He would attend such a place, with a companion, but would disappear before the orchestra had finished playing the overture, or, at latest, before the middle of the first act had been reached. He would wander down stairs and chat with the 'Front of the House,' stroll to a cab rank and discuss the points of a horse with a Jehu or seize on some acquaintance and plunge into the less-lighted streets talking ‘paper’. The dim byways of Darlinghurst and Potts Point wore the scenes of his nightly rambles and his peripatetic 'journalising' with the friend of the evening.

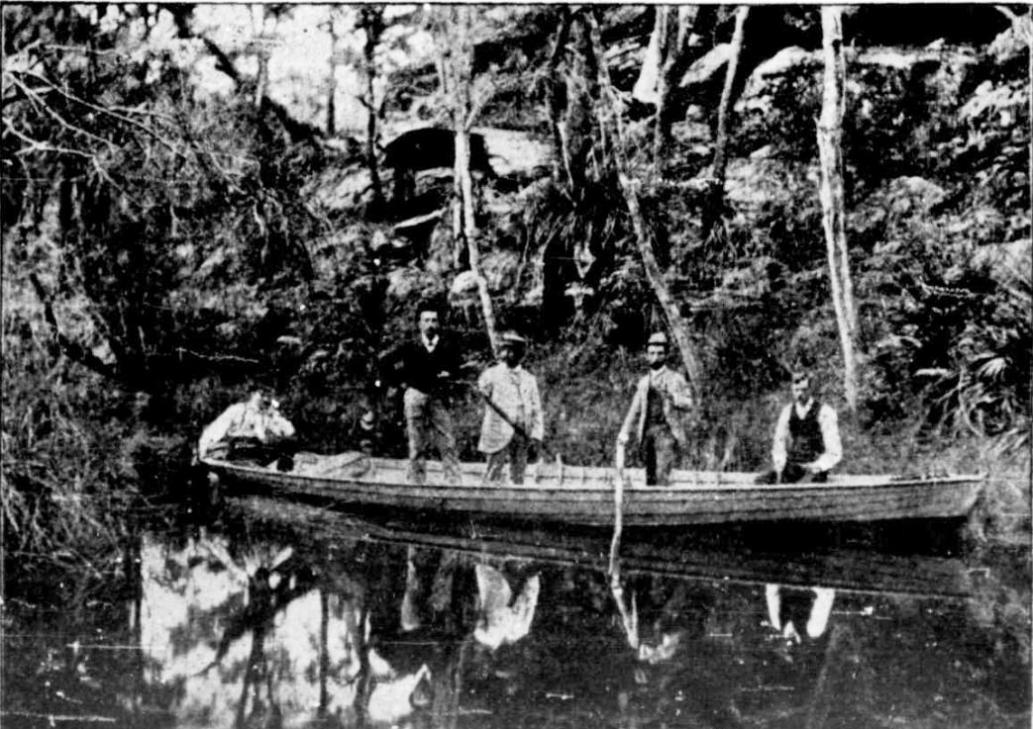

In those days Archibald's chief relaxations were long walks and fishing excursions — but not with a party. A single companion, with whom he could talk 'paper,' was all that he required. 'The paper' obsessed him, absolutely and unceasingly. In his short snatches of sleep he often dreamt ‘paper,' and burnt the candle of a remarkable nervous vitality at both ends. Ultimately he was called upon to pay for the tremendous expenditure of energy by shattering health both of mind and body.

In the strenuous days of the 'Bulletin', Wednesday afternoon was Archibald's weekly half-holiday, spent when he lived at Darlinghurst by a wander about the foreshores of Sydney Harbor, or a trip to the Zoo, or a fishing jaunt anywhere with a wharf attached; when he lived at Manly, often by a tramp to Narrabeen and back. A motor-boat at Port Hacking, in the days of his recovery from serious breakdown, extended his piscatorial excursions to notable expeditions and epic exploits unrecorded in the placid annals of Izaak Walton.

When Archibald went to Manly— 'on residence,' as the French have it — he assumed insignia of editorial office in the shape of a pigskin bag, somewhat smaller than a Gladstone and Larger than a kit. Every evening it was stuffed to repletion with copy and proofs and a correspondence dated from almost every postal town in Australia besides many letters and contributions from far-away nooks in the Old World and New — for he held firm to his faith that every man was a husk concealing the kernel of at least one story, could it only be gotten at. He devoted hours to reading that appalling mail, selecting, editing, polishing. He worked like a lapidary for months over Louis Becke's 'By Reef and Palm.' To use his own expression, he wanted every sentence to shine like a star. During the long boat trip to Manly he read his proofs and marked for reference the evening papers with a blue pencil. If he had a companion he revelled in a Paradise of his own creation. From the depths of his bag he would fish forth (the action reminded me of his piscatorial afternoons) a something or other to read — a convict episode, perhaps, by 'Price Waning,'' or a short story by Randolph Bedford or Albert Dorrington, or some topical verse by George Black, a philosophical article from the pen of Francis Adams, or mayhap a chapter of the 'History of Botany Bay' by Arthur Gayll, a character sketch by Frank Myers, a screed anent old mining days by Ted Dyson, a back-blocks, ballad by 'The Banjo', a literary criticism by the 'Red Pagan,'' a study of Malay life and character by Alick Montgomery, a jingle by Edmund Fisher or 'The Colonel,' a political philippic by Joes O'Brien, or a strong leader by some Australian Boanerges of the 'Bulletin', on 'The Parks for the People.' In Memoriam: Jules Francois Archibald. (

1919, October 9).

Worker (Brisbane, Qld. : 1890 - 1955), p. 17. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71422893

How long would a tramp to Narrabeen take? a few hours - and was this popular? - yes it was - there was also a considerable rise in the number of fish to be caught at Narrabeen due to a ban on netting:

SYDNEY AMATEUR WALKING CLUB.

The North Shore Tourists and the Sydney Amateur Walking Club made an excursion on Sunday to the Narrabeen Lakes. The tourists (among whom may be mentioned F. Bauer, A. J. Napier, H. H. Pooley, and H. Healy) met at the engine-house of the North Sydney tramway, and at 9.15 a start was made along the Military-road to the Spit ferry. After crossing Middle Harbour the Manly road was followed for about two miles, then taking a bush track to the left for nearly a mile, Pittwater-road was struck at 10.42. From there the Newport road was followed, passing Dee Wey Lagoon at 11.30, and Narrabeen Lakes at noon. The walking time was two and a half hours. Four hours were spent at Narrabeen, and at 3 o'clock the return journey was commenced, the party crossing the Spit ferry at 5 o'clock and reaching North Sydney 5.50. Through-out the tramp an average of four miles per hour was maintained, and the distance covered both ways about 22 miles. SYDNEY AMATEUR WALKING CLUB. (

1894, July 18).

The Sydney Morning Herald(NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 7. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28260821

the whole of the tidal waters of Manly, Carl Curl, Deewhy, and Narrabeen Lagoons, together with all bays, affluents, and tributaries, have been closed against net fishing for two years. NEWS OF THE WEEK. (1894, March 3).Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907), p. 16. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71210797

It would seem the fabled fishing trip did take place, that it was fishing at Narrabeen Lagoon and Wednesday the 18th of September or Thursday the 19th may have been the day or even later in Clemen's week and a half first visit to the harbour city. His 'Journals' note that he claimed to have caught a fish at Bondi on September 19th and that this is the root of the 'shark stories' that form part of Clemen's espousing on the same in Sydney in

Following the Equator - A journey around the world.

It could also be read, from this information, that similar skylarking and fishing, with Mr. Lawson near or not far away, happened on occasion at Manly during his brief stay in Sydney before heading to Melbourne and Adelaide on Wednesday September 25th. The trip may even have taken place during his return to Sydney from New Zealand, arriving Tuesday December 18th to his departure on Monday December 23rd, barring the day spent on the Hawkesbury.

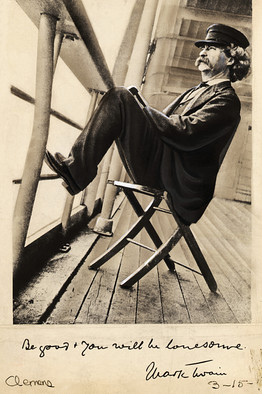

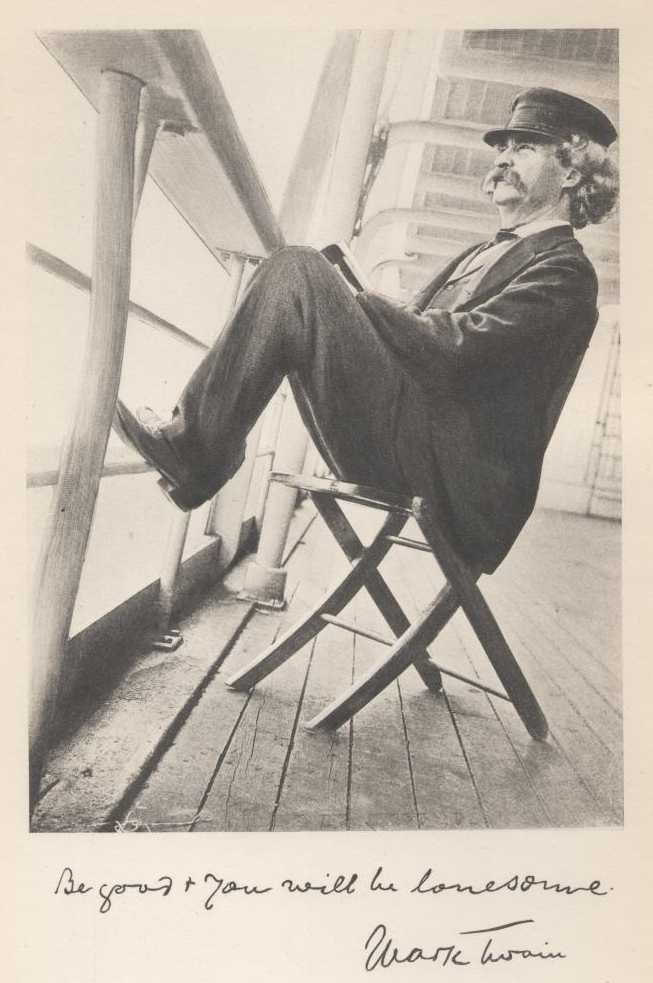

Don’t tell fish stories where the people know you, but particularly, don’t tell them where they know the fish. - Mark Twain

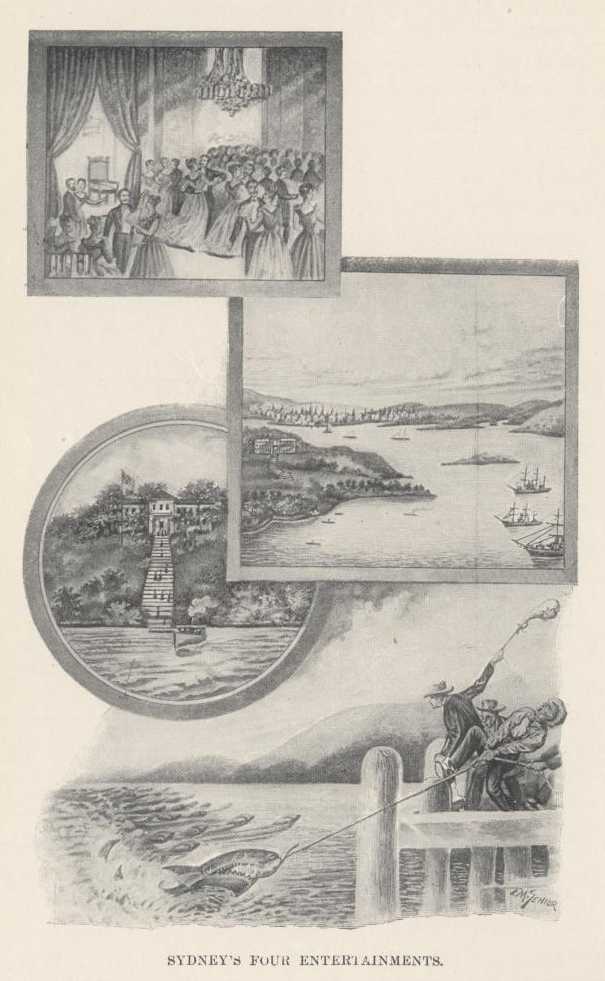

Mr Clemen's on Sydney Harbour from Following the Equator...

"It would be beautiful without Sydney, but not above half as beautiful as it is now, with Sydney added. It is shaped somewhat like an oak-leaf—a roomy sheet of lovely blue water, with narrow off-shoots of water running up into the country on both sides between long fingers of land, high wooden ridges with sides sloped like graves. Handsome villas are perched here and there on these ridges, snuggling amongst the foliage, and one catches alluring glimpses of them as the ship swims by toward the city. The city clothes a cluster of hills and a ruffle of neighboring ridges with its undulating masses of masonry, and out of these masses spring towers and spires and other architectural dignities and grandeurs that break the flowing lines and give picturesqueness to the general effect.

The narrow inlets which I have mentioned go wandering out into the land everywhere and hiding themselves in it, and pleasure-launches are always exploring them with picnic parties on board. It is said by trustworthy people that if you explore them all you will find that you have covered 700 miles of water passage. But there are liars everywhere this year, and they will double that when their works are in good going order. October was close at hand, spring was come. It was really spring—everybody said so; but you could have sold it for summer in Canada, and nobody would have suspected. It was the very weather that makes our home summers the perfection of climatic luxury; I mean, when you are out in the wood or by the sea. But these people said it was cool, now—a person ought to see Sydney in the summer time if he wanted to know what warm weather is; and he ought to go north ten or fifteen hundred miles if he wanted to know what hot weather is." Extract from Chapter IX

Among 'four social pleasures' is reference once again to piscatorial pleasures:

'There are four specialties attainable in the way of social pleasure. If you enter your name on the Visitor’s Book at Government House you will receive an invitation to the next ball that takes place there, if nothing can be proven against you. ...

Another of Sydney’s social pleasures is the visit to the Admiralty House; which is nobly situated on high ground overlooking the water. The trim boats of the service convey the guests thither; and there, or on board the flag-ship, they have the duplicate of the hospitalities of Government House. The Admiral commanding a station in British waters is a magnate of the first degree, and he is sumptuously housed, as becomes the dignity of his office.

Third in the list of special pleasures is the tour of the harbor in a fine steam pleasure-launch. Your richer friends own boats of this kind, and they will invite you, and the joys of the trip will make a long day seem short.

And finally comes the shark-fishing. Sydney Harbor is populous with the finest breeds of man-eating sharks in the world. Some people make their living catching them; for the Government pays a cash bounty on them.' Extract from ChapterIXIII

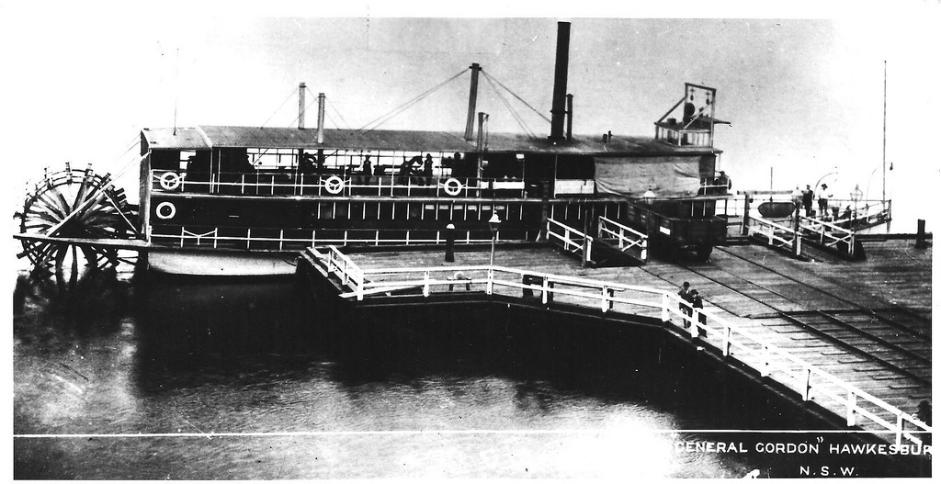

Prior to heading south once more Mr. Clemens did in fact visit closer our namesake estuary on Sunday, December 22nd when a visit to the Hawkesbury, leaving via the Market Street wharf (per 'Journals'), formed part of his second last day in Sydney. His wife Livy and one of his daughters, Clara, who accompanied him on his 'world tour', also went on the trip to the Hawkesbury. Here once again a note is recorded that he had contact with Bulletin staff on this day - probably J. F. Archibald.

This visit to the 'Hawkesbury National Park' was in the company of a H. S. Chipman. The steamships Newcastle, Sydney, Maitland and Namoi offered excursionists picnic and day visits to the Hawkesbury and Pittwater (Newport) during 1895. The Government also offered a trip via train on Sunday December 22nd, departing from Milson's Point, to the Hawkesbury where excursionists would be taken on the General Gordon paddlewheeler for a trip along the Hawkesbury.

AFTERNOON EXCURSIONS.

S.S. NAMOI, 1414 tons, to HAWKESBURY RIVER,on SATURDAY, from Market-street Wharf, at 2. Return Fare, 2s. Advertising (

1895, December 17). Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931), p. 6. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108082815

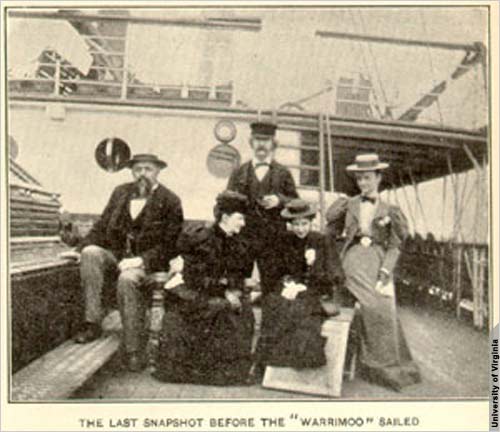

People nowadays pass their lives reading papers and getting photographed, and two hours after Mark Twain had landed in Sydney, he, with his wife and daughter, had been taken by Falk and Co. Mrs. Clemens takes life more seriously than her husband, is reserved in manner, and looks at everything through matter-of-fact glasses. She dresses simply, having a preference for brown colours; so has her daughter, a slight, dark, pretty girl, with hair done in Madonna fashion. They are attentive listeners to Mark's entertaining stories, and it is easy to see that the author of The Innocents Abroad is a hero in the eyes of his wife and daughter.

MRS. S. CLEMENS. Miss CLEMENS

WIFE AND DAUGHTER OF MARK TWAIN.

(PHOTOGRAPHED SPECIALLY FOR " THE AUSTRALASIAN " BY FALK, SYDNEY AND MELBOURNE.) No title (

1895, September 28).

The Australasian (Melbourne, Vic. : 1864 - 1946), p. 21. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article139715519

Curiously Henry Lawson, among his

correspondence files, has a letter-card sent to George Robertson of Angus & Robertson, publishers, in March 1920, which features a view of the Hawkesbury and gives his Eureka Street, North Sydney address as a return. No indication of when the letter-card may have been purchased is indicated. There is also a studio portrait done by wonderful photographer May Moore, a resident of Bayview, that dates as around 1915:

Henry Lawson - studio portrait by

May Moore, ca. 1915,

Creator Moore, May, 1881-1931 Digital Order No. a128844, courtesy State Library of NSW.

Henry Lawson's first published poem 'A Song of the Republic' appeared in The Bulletin, 1 October 1887. The Bulletin became Australia's leading outlet for poets, cartoonists, short-stories and comic writers, its value could never be overestimated. It was Archibald who, in 1892, when Lawson seemed failing and drinking too much alcohol for anyone's good, suggested he take a trip inland at the Bulletin's expense. Providing £5 and a rail ticket to Bourke, Lawson set out in September 1892 on what was be one of the most important journeys of his life. During this sojourn Lawson saw a drought-blasted west of New South Wales that appalled him. 'You can have no idea of the horrors of the country out here', he wrote to his aunt, 'men tramp and beg and live like dogs'. For months the experience at Bourke itself and in surrounding districts through which he carried his swag absolutely overwhelmed him. By the time he returned to civilization, he was armed with memories and experiences, some comic, many shattering, that would fill his writing for years and attribute to his apt name as a 'bush poet'alongside contemporary Banjo Paterson.[2.]

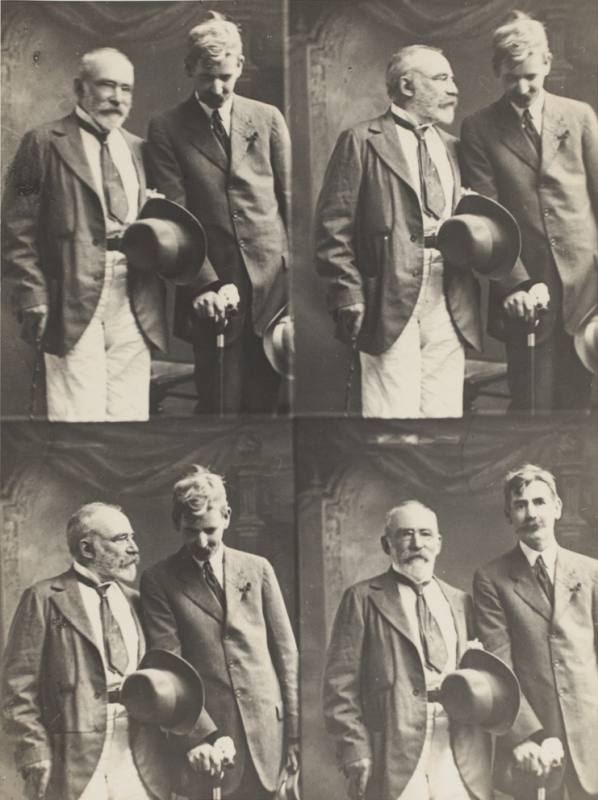

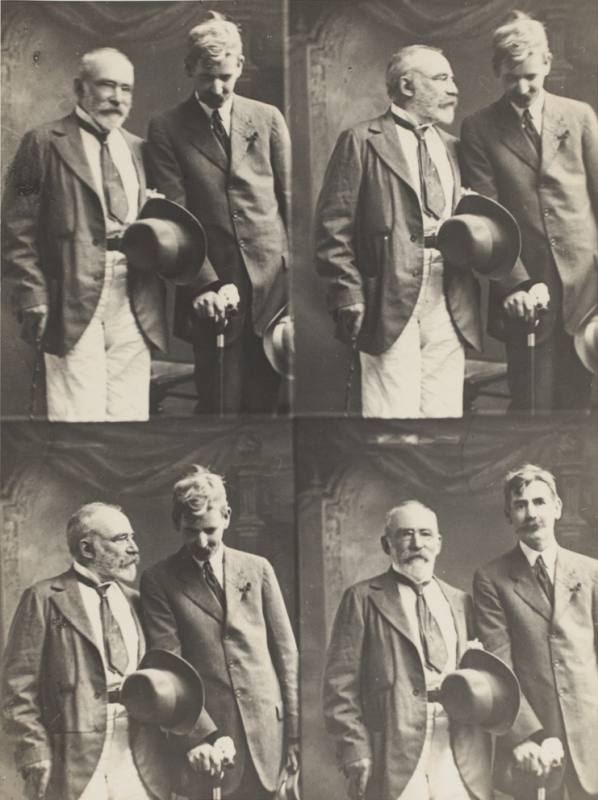

Archibald and Lawson together - circa 1915-1918 courtesy State Library of NSW, Image No.: a6176019h, from the album, Series 07: Henry Lawson family photographs, friends and memorial events, 1897-1956

Was Henry on that fishing trip to Narrabeen with Archibald and Clemens? - possibly. The story that caused such mirth, as with all fishing stories, probably had a touch of the fanciful woven larger by time. Clemens/Twain was certainly someone Lawson held in high regard. Reference is made to 'Twain' in some of Henry's writings - a few samples here from before and after they met:

CULLED VERSE

The Vote of Thanks Debate

[This poem was written by Henry Lawson on the occasion of the vote of thanks moved in Parliament to the Police and Military heads, following the

bush strike of 1891.]

The other night I got the blues and tried to smile in vain,

I couldn't chuck a chuckle at the foolery of Twain ;

When Ward and Billings failed to bring a twinkle to my eye,

I turned my eyes to "Hansard" of the fifteenth of July.

I laughed and roared until I thought that I was growing fat,

And all the boarders came to see what I was laughing at;

It rose the risibility of some, I grieve to state

That foolish speech of Brentnall's in the Vote of Thanks debate.

Oh, Brentnall, of the olden school and cold, sarcastic style!

You'll take another "Worker" now and stick it on your file;

"We're very fond of poetry," we hope that this is quite

As entertaining as the lines you read the other night.

We know that you are honest, but 'twas foolish to confess

You read and file the "Worker" ; we expected something less.

We think an older member would have told the people, so -

"My attention was directed to a certain print" (you know).

The other night in Parliament you quoted something true,

Where truth is very seldom heard except from one or two.

You know that when the people rise the other side must fail,

And you are on the other side, and that explains it all.

You hate the Cause by instinct, the instinct of your class,

And fear the reformation that shall surely come to pass;

Your nest is feathered by the "laws" which you, of course, defend,

Your daily bread is buttered on the upper crust, my friend.

"We aim at broader interests," you say, and so we do;

WE aim at "vested interests" (the gun is loaded, too).

We HATE the wrongs we write against. We've

FELT the curse of Greed.

There's little nonsense in the school where Labor learns its creed.

But you know little of the Cause that you are running down.

You would deny there's misery and hardship in the town;

Yet I could take you through the hells where poverty holds sway.

And show you things you'd not forget until your dying day.

Oh, Brentnall! Have you ever tramped the city streets within,

And felt the pavement wearing thro' the leather, sock, and skin?

And looked for work, and asked for work, and begged for work in vain,

Until you cared not though you ne'er might touch your tools again?

Oh, Brentnall! Have you ever felt the summer sun and dirt?

And wore the stiffened socks for weeks, for weeks the single shirt?

And shunned your friends like smallpox— passing on the other side—

And crept away in shadows with your misery and pride?

Another solemn member rose encouraged by the cheers,

And talked of serving medals to our gallant volunteers,

And extra uniforms, that they might hand the old ones on

"As heirlooms in the family" when they are dead and gone.

But since the state of future times is very much in doubt,

They'd better wear their uniforms, they'd better wear them out;

They may some day be sorry for the front that they have shown,

And, e'er the nap is worn away, they mightn't like it known.

The children of a future time shall read, with awe profound,

How goslings did the goose step while a gander led 'em round.

Oh, Brentnall! Speak your periods into a phonograph,

that generations yet to rise may lay them down and laugh.

I wouldn't trust the future much, Posterity might own

That sense of the ridiculous that you have never shown;

And not the smiles of Mammon, nor the pride of place and pelf,

Can soothe the thought that one has made a Jackass of one's self.

We're low, but we would teach you it you're willing to be taught,

That in the wilderness of print are tartars still uncaught;

And if you hunt in such a way— believe we do not jest

Your chance to catch one is as good and better than the best.

Be very sure about the mark before you cast the stone,

And, well, perhaps 'twould be as well to leave the muse alone.

You'll call it egotism?

Yes; but still I think that I

Might hit a little harder if I only liked to try.

Henry Lawson Brisbane, July, 1891.

The Old Pens and the New

Henry Lawson, 1908

I wish that Time could bring again

To Letters — and so give to Art —

The healthy humour of Mark Twain,

The kindly scamps of poor Bret Harte!

This worship of the Things That Are,

These lazy pens of Let it Bide —

These would-be makers who but mar

Have held their sway since Dickens died.

Oh, we are wise, and "realise",

We study men and things, and know —

Just in the sense that fools grew wise

Three thousand weary years ago.

We sit beneath the fraud and fool,

With poisoned minds in manhood's prime,

While children prattle home from school,

As happy as in Pharaoh's time!

We want no God, but many a god,

And we want many gods and none —

The preacher by the upturned sod

Shall pray, when all is said and done.

We make a noble thing of sin —

We've found the "Truth" (for aught I know),

Since we, as children, tip-toed in

When late to "chapel" long ago.

We part the husband and the wife,

And make a filthy thing of love.

We make a "problem" of grand Life!

Despite the shining signs above.

We "scoff at gale" or "rail at fate",

Or rave and rant with rotten lung,

But Jim and Mary at the gate

Are young as when the world was young.

There's gold, and passing fame in store

For those with "clever books" to give,

But I would win me back once more

To where my working people live.

Where evening, coming on apace,

Brings father and the boys to see

The mother bustling round the place,

And Mary "dishing" up the "tea".

A bit about Mr. 'Twain' while on our shores.

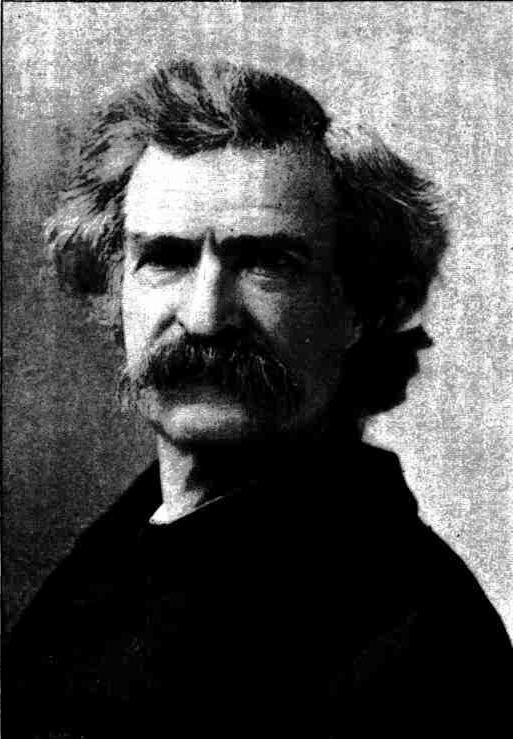

Mark Twain.

Mark Twain.