August 29 - September 4, 2021: Issue 508

National Cabinet Must Revise Its Plan To Transition Australia’s National COVID-19 Response; High Morbidity And Mortality Predicted Under Current Targets

Australia Cannot Treat COVID-19 ‘Like The Flu

August 24, 2021

ZOË HYDE, QUENTIN GRAFTON, TOM KOMPAS

National Cabinet must revise its plan to transition Australia’s National COVID-19 Response

The New South Wales COVID-19 epidemic has highlighted the divisions in National Cabinet about what vaccination level needs to be reached before Australia can relax its COVID-19 restrictions, Zoë Hyde, Quentin Grafton, and Tom Kompas write.

On 30 July, National Cabinet’s National Plan to transition Australia’s National COVID-19 Response was announced, intended to manage a shift in Australia’s pandemic response from the suppression of COVID-19 to managing the virus like other common respiratory diseases.

As part of this plan, vaccination targets for those aged over 16 were set. These targets were informed by epidemiological modelling undertaken by the Doherty Institute and an economic impact analysis by the Australian Treasury.

Currently, Australia is in Phase A of the Plan, the ‘vaccinate, prepare and pilot’ phase, with the goal to “strongly suppress the virus for the purpose of minimising community transmission”.

Once 70 per cent of the adult population is fully vaccinated with two doses of vaccine, Australia will transition into Phase B, where the goal will be to “…to minimise serious illness, hospitalisation and fatality as a result of COVID-19 with low level restrictions”.

Phase C begins when 80 per cent of the adult population is fully vaccinated, and its goal will be “…to minimise serious illness, hospitalisations, and fatalities as a result of COVID-19 with baseline restrictions”. Phase C will only allow for highly targeted lockdowns.

Finally, Phase D’s goal is to “manage COVID-19 consistent with public health management of other infectious diseases”. This final phase of the Plan is likely to be reached in 2022. At that point, international borders will reopen and there will no longer be ongoing public health restrictions or lockdowns. In other words, COVID-19 will be managed like other common respiratory diseases, akin to treating the virus “like the flu”.

Unfortunately, this National Plan to transition Australia’s COVID-19 response is back to front. Instead, the Government should establish a transition strategy based on the following three key pillars.

First, it must be built on staying below a transparent and agreed-upon maximum tolerable number of hospitalisations and fatalities, as well as long COVID cases, determined by National Cabinet.

Second, it should identify the minimum vaccination level for the total population and for vulnerable groups required to achieve public health goals. These numbers should be fully informed by comprehensive risk analyses, account for scientific uncertainty in key parameters, and be comprehensible to decision-makers.

Third, it must evaluate public health and economic trade-offs – at different vaccination levels – for both the total population and vulnerable groups.

We have modelled the projected outcomes of dropping all public health measures and managing COVID-19 like the flu at different levels of vaccination.

Our modelling evaluates the effects of vaccinating children, providing a single mRNA booster (of Pfizer or Moderna vaccine) to all those who received the AstraZeneca vaccine, and vaccinating all those 60 years of age and older at a higher level than the general population – 95 per cent.

Our results are built on four key assumptions.

First, that when Australia no longer imposes adequate public health restrictions or lockdowns, everyone will eventually be exposed to the virus that causes COVID-19.

Second, we assume that Australians will face a variant that is at least as transmissible as the Delta variant, which has an estimated basic reproduction number, or R0, of six.

Third, that fatality rates will be at least as high as those observed for the original strain in 2020.

And finally, that vaccine effectiveness against infection, symptomatic disease, and hospitalisation are, respectively, for AstraZeneca: 60, 67, and 92 per cent, and for Pfizer: 79, 88, and 96 per cent.

Making these assumptions, our modelling shows that herd immunity against strains as contagious as the Delta variant can be achieved if 95 per cent or more of the entire population is vaccinated, but only if people who receive the AstraZeneca vaccine are subsequently given a mRNA booster shot.

We find that if 70 per cent of Australians over 16 years of age are fully vaccinated, but with a 95 per cent vaccination level for those aged 60 years and over, there could eventually be some 6.9 million symptomatic COVID-19 cases, 154,000 hospitalisations, and 29,000 fatalities. Notably, hospitalisations and fatalities would not be restricted to the unvaccinated.

Further, if just five per cent of symptomatic cases result in long COVID, where serious symptoms such as post-viral fatigue can persist for months or longer, and which can also occur in vaccine breakthrough infections, some 270,000 Australians could develop long COVID, even if 80 per cent of those aged 16 years and over are vaccinated.

If children are also fully vaccinated, national fatalities – for all age groups – would be reduced to 19,000, assuming 80 per cent adult vaccination coverage, and would fall to 10,000 at a 90 per cent adult vaccination coverage.

Children also benefit directly from vaccination. Our projections indicate that 12,000 hospitalisations could be prevented in children and adolescents if 75 per cent vaccination coverage is achieved in these age groups.

Giving adults a booster dose of an mRNA vaccine further improves outcomes. At 80 per cent adult vaccination coverage but allowing for an mRNA booster for all those fully vaccinated with AstraZeneca, symptomatic cases, hospitalisations, and fatalities could be much less, with our modelling predicting 6,000 fewer deaths.

Our projections of fatalities are much higher than those of the Doherty Institute used in the National Plan. The Doherty Institute, relative to our modelling, assumed: a shorter modelling time horizon, a lower assumed proportion of symptomatic infections, lower transmission among children, baseline public health measures that reduce the reproduction number from 6.32 to 3.6, and that Test, Trace, Isolate and Quarantine remains partially effective, even at very high new daily cases.

Our projections of hospitalisations and fatalities would have been even worse if we had used the higher preliminary estimates of the increased virulence of the Delta variant. This means our projections likely represent a lower estimate of the cumulative public health outcomes of fully relaxing public health measures at Phase D of the National Plan, or sooner, if outbreaks are not effectively suppressed or eliminated.

Our results suggest that four key vaccination steps must be followed before exposing Australians to uncontrolled SARS-CoV-2 infection.

First, children and adolescents should be vaccinated.

Second, vaccine coverage among adults aged older than 60, and in other vulnerable groups like among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, should be 95 per cent or higher.

Third, Australians vaccinated with AstraZeneca should be given an mRNA (Pfizer or Moderna) booster before the international border reopens or public health measures are prematurely relaxed when there is ongoing community transmission. Those vaccinated with an mRNA vaccine should also receive a booster shot, when appropriate.

And, finally, Australia needs very high vaccination coverage for the entire population, preferably more than 90 per cent, to mitigate excess deaths.

If the country achieves these four steps, fully relaxing public health measures to eliminate community transmission could still, eventually, result in some 5,000 fatalities and 40,000 cases of long COVID.

By comparison, under the National Plan, assuming 80 per cent vaccination coverage overall for those over 16 – without attaining 95 per cent coverage in those aged 60 and over – there could be 10 times as many cumulative fatalities, approximately 50,000, and some 270,000 cases of long COVID, when public health restrictions are fully relaxed.

The consequences of prematurely relaxing public health measures to suppress COVID-19, even after vaccinating 80 per cent of adults, would likely be irreversible, and unacceptable to many Australians.

National Cabinet must not squander its opportunity to devise a safe and affordable transition to a ‘post-COVID-19’ era. If National Cabinet revises its strategy to include our four vaccination steps, many lives will be saved, and many more (including children) will not suffer from debilitating long COVID.

The information contained in this article is not formal medical advice regarding COVID-19. For individual medical advice about COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccinations, consult with your GP.

This piece was first published at Policy Forum, Asia and the Pacific’s platform for public policy analysis and opinion. Read the original here: https://www.policyforum.net/australia-cannot-treat-covid-19-like-the-flu/

By same Authors:

High vaccination coverage is required before public health measures can be relaxed and Australia’s international border fully reopened. ZoëHyde*Western Australian Centre for Health and AgeingThe University of Western Australia Perth, Western Australia Australia, John Parslow Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, R. Quentin Grafton Crawford School of Public Policy The Australian National University Canberra, ACT, Australia, Tom Kompas Centre of Excellence for Biosecurity Risk Analysis University of Melbourne Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

This version 14 August 2021- Abstract

In July 2021, the Australian Government announced a national plan to transition its response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic from the current goal of suppression of community transmission, to managing COVID-19 like other common respiratory pathogens. We modelled the likely morbidity and mortality expected to eventually result from prematurely relaxing lockdowns and/or fully reopening Australia’s international border at various levels of vaccination coverage. We find substantial morbidity and mortality is likely to occur with the Government’s target of vaccinating 80% of Australians aged ≥16 years, and that vaccinating more than 90% of the total population is highly desirable.

Vital Signs: with vaccine thresholds come the danger of repeating past mistakes

Richard Holden, UNSWIn 2020 when people talked about “living with COVID” it was code for letting the virus rip. It was really a plan for many to “die with COVID”.

Thankfully our political leaders listened to experts.

In general, Australia managed the pandemic’s public health and economic challenges better than most countries. The glaring exceptions were, of course, our vaccination strategy and our quarantine arrangements.

With vaccines we didn’t buy a properly diversified portfolio of vaccines, didn’t act with a sense of urgency — “It’s not a race,” said the Prime Minister and other ministers — and didn’t have an effective plan for getting jabs into arms quickly.

With quarantine arrangements we failed to build fit-for-purpose facilities akin to the one in Howard Springs outside Darwin. Instead we relied on poorly ventilated hotels in the heart of our biggest and most densely populated cities.

Now, with the roll-out of high-efficacy vaccines against COVID-19, we are beginning to have a national discussion genuinely about how to live with COVID.

It is vital that during that discussion we don’t repeat the mistakes of 2020.

Those mistakes all sprang from false economies.

The federal government thought we could save a few bucks by gambling on vaccine purchases. It favoured vaccines that could be made locally more as a back-door industry policy rather than strategic supply-chain management. It thought using hotels as quarantine facilities could help financially support the hospitality sector.

Pinching pennies cost us. Big time.

It is imperative we don’t fall into the trap of false economies again by opening up too soon, before what is needed to stay open is in place.

Vaccination Milestones

The national plan about when Australia will “reopen” is pegged to vaccination milestones.

We’re still in the first of the four-phase plan. We will move to Phase B (the “vaccine transition phase”) when 70% of eligible Australians over the age of 16 are vaccinated. At 80% we move to Phase C (the “vaccination consolidation phase”).

At this 80% threshold the plan is for only “highly targeted lockdowns”, the end of passenger caps for vaccinated Australians returning home, and restarting outbound travel for vaccinated Australians.

There are important epidemiological debates about whether 70% and 80% are the right thresholds. I’m just an economist, so I’m not going to get into that here.

But if we accept, for the sake of argument, that 80% is the practically relevant threshold for moving to Phase C of the national plan, then we should at least insist on getting the arithmetic right.

On this, there are two key questions.

80% Of What?

The first is about the vaccination rate. Moving to Phase C calls for 80% of the “eligible” population to be fully vaccinated.

But that’s not 80% of Australia’s population of 25.8 million.

Rather, it’s 80% of the population aged 16 and over — about 16.6 million people, or 64% of the population.

If the national plan is changed to make it 80% of the population aged 12 and over, that would be about 17.6 million people, or 68% of the population. To paraphrase the United States politician Everett Dirksen, a million here, a million there, and pretty soon you’re talking about real numbers.

There are two points here.

First, the much-touted 80% threshold is really only 64% of the whole population. Yet herd-immunity levels — where outbreaks die out — are typically expressed as a proportion of the entire population. Given the basic reproduction rate of the Delta variant and current vaccine effectiveness, the actual herd immunity vaccination threshold could easily be north of 85%.

Read more: How will Delta evolve? Here's what the theory tells us

Second, the longer that lockdowns continue, the stronger the temptation for politicians to shift to targets that are easier to achieve. Though this might be politically convenient, it would be disastrous.

Read more: Should we give up on COVID-zero? Until most of us are vaccinated, we can't live with the virus

80% Plus How Long?

The second question is how long after hitting the 80% threshold do we begin moving from Phase C to Phase D.

Clinical trial data for the Pfizer vaccine suggests the best immune response occurs about two weeks after the second dose. The federal Department of Health emphasises that:

Individuals may not be fully protected until 7-14 days after their second dose of the Pfizer (Comirnaty) or AstraZeneca (Vaxzevria) vaccine.

Read more: How long do COVID vaccines take to start working?

So if the government is going to stick to the spirit of the national plan, we really should be waiting until two weeks after 80% of the 12+ population has been vaccinated.

Again, there will be a big political temptation to reopen the day of the “threshold” second jab, rather than when it really becomes effective.

Don’t Fall At The Final Hurdle

Australians have put up with a lot since early 2020. A devastating virus, lockdowns, uncertainty, isolation from loved ones, economic pain, and differing degrees of government competence.

It is essential we finish this race properly. We must not let our political leaders reopen too early by redefining the targets they have signed up for. It would be the ultimate false economy.![]()

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Opening with 70% of adults vaccinated, the Doherty report predicts 1.5K deaths in 6 months. We need a revised plan

Stephen Duckett, Grattan Institute and Anika Stobart, Grattan InstituteOne consequence of the escalating COVID outbreak in New South Wales has been increased political tension around the “national plan” for COVID reopening.

The prime minister has argued that states signed up to the plan – albeit “in principle”, whatever that means – and they should do whatever the plan says, whenever the plan says to do it.

Some premiers are now pushing back, arguing the Doherty Institute modelling was based on certain assumptions which no longer hold true so the previous agreement no longer stands.

There are three distinct questions at issue here. Is the Doherty Institute modelling still applicable? How does the national plan stack up? And what should happen next?

1. Is The Doherty Institute Modelling Still Applicable?

The Doherty Institute was given a very specific remit. It was asked “to define a target level of vaccine coverage for transition to Phase B of the national plan”, where lockdowns would be “less likely, but possible”.

Read more: Australia has a new four-phase plan for a return to normality. Here's what we know so far

In identifying the vaccination coverage target for the transition to Phase B, Doherty’s experts assumed that testing, tracing, isolation, and quarantine (TTIQ), would be central to maintaining lower case numbers.

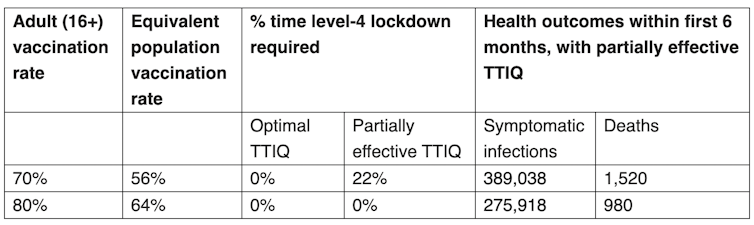

They highlighted two scenarios in terms of testing-tracing-isolation-quarantine capacity – an “optimal” scenario and a “partially effective” scenario – summarised in the table below.

Doherty Institute modelling outcomes

While these numbers may look acceptable, the assumptions underlying them are now hanging by a thread.

Case numbers have been rising rapidly, putting significant pressure on testing-tracing-isolation-quarantine capacity.

Doherty Institute described its assumptions thus:

We assume that once community transmission becomes established leading to high caseloads, TTIQ [testing-tracing-isolation-quarantine] is less efficacious than the optimal levels observed in Australia because public health response capacity is finite.

This tells us that given our current high case numbers, we can probably only assume, at best, “partially effective” testing-tracing-isolation-quarantine capacity.

It’s also important to note the Doherty modelling did not incorporate scenarios where the virus was in uncontrolled spread after target vaccination levels are achieved.

But it now seems unlikely that NSW – and maybe even Victoria – will be able to suppress COVID down to zero before any vaccination target is reached.

If lockdowns are eased according to the modelled targets, while there is still substantial community transmission, testing-tracing-isolation-quarantine is unlikely to be enough to suppress further spread sufficiently, potentially resulting in higher numbers of hospitalisations and deaths than initially modelled.

2. How Does The National Plan Stack-Up?

The federal government used the Doherty Institute report’s findings as the basis of the “national plan” it put to National Cabinet.

But it glossed over the options, scenarios, and caveats in the Doherty modelling, and assumed the most optimistic testing-tracing-isolation-quarantine scenario: that everything would be rosy if Australia started opening up once 70% of adults (equivalent to only just over half the population) are vaccinated.

The transition to Phase C, where lockdowns would be targeted and vaccinated people would be exempt from restrictions, was also optimistically adopted at 80% adult vaccination, despite the lack of modelling for this scenario in the Doherty report.

In a bid to make it appear convincing – but also realistic, given all the uncertainty – a veil of vagueness was cast over the national plan. The document is full of weasel-words and caveats, which means it is impossible for anyone to be held to account.

The equivocal “in-principle” condition on National Cabinet’s approval makes it even harder to know exactly what premiers signed up to.

But the severity of the New South Wales outbreak has forced some of our leaders to take off the rose-coloured glasses and adopt a more realistic view. Premiers are now saying they did not sign up to high death tolls.

According to Doherty modelling, deaths could reach 1,500 within six months of implementing Phase B. Agreeing to such a scenario is politically untenable for states that currently have zero cases.

3. So, What Should Happen Next?

With states divided over the national plan, and the modelling potentially out of date, it’s time for National Cabinet to come back with a new approach. We need a revised national plan – one that all states can sign up to, one that is not full of caveats and conditions.

This should include a realistic plan for scaling up testing-tracing-isolation-quarantine capacity so that it can manage in a feasible way when each infected person could have at least ten new contacts per day.

And it should include a plan to protect primary schools and childcare centres while a vaccine remains unavailable for younger children.

Grattan Institute has also done its own modelling.

But our model was about Phase D – what Australia needs to do to avoid obtrusive restrictions such as lockdowns altogether – which was not modelled by the Doherty Institute.

We argued that it is only safe to open the borders, to lift restrictions, and to manage without lockdowns and use only unobtrusive measures such as masks on public transport, if we vaccinate at least 80% of the total population and continue the vaccination rollout to 90% throughout 2022.

Recent modelling from other academics has come to similar conclusions, with some even suggesting a slightly higher threshold for safe re-opening.

Governments cannot keep making unrealistic promises about easing restrictions at 70% and 80% adult vaccination, a plan that relied on optimistic scenarios in the first place, and one that now bears little relation to the real world. It is irresponsible to build public momentum and hope around targets that are unlikely going to be enough.

Australia needs the National Cabinet to come clean and accept that the changing circumstances require a change in the plan.![]()

Stephen Duckett, Director, Health and Aged Care Program, Grattan Institute and Anika Stobart, Associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.