August 21 - 27, 2022: Issue 551

Masked Lapwing Plover Chicks Were In Danger: Now They're Dead Because No One Is 'Responsible' For Wildlife In Council Areas

%20body%20on%20road.jpg?timestamp=1660979088040)

Local councils responsibilities as defined under the Local Government Act 1993. This directs councils to properly manage, develop, protect, restore, enhance and conserve the local environment for which it’s responsible, in a manner that’s consistent with and promotes the principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development.

That's why it was so surprising to see the local council recommending formalising illegal bike tracks at Ingleside and North Narrabeen, where wildlife was once safe and could live in peace, and where at least one wallaby has already been run over by a biker. Visit: Council's Open Space and Outdoor Recreation and Action Plan Open For Feedback: Supports Formalising Illegal Bike Tracks In Bush Reserves and Public Parks feedback closed August 14.

Under the Local Government Act 1993 :

36E Core objectives for management of community land categorised as a natural area

The core objectives for management of community land categorised as a natural area are—

(a) to conserve biodiversity and maintain ecosystem function in respect of the land, or the feature or habitat in respect of which the land is categorised as a natural area, and

(b) to maintain the land, or that feature or habitat, in its natural state and setting, and

(c) to provide for the restoration and regeneration of the land, and

(d) to provide for community use of and access to the land in such a manner as will minimise and mitigate any disturbance caused by human intrusion, and

(e) to assist in and facilitate the implementation of any provisions restricting the use and management of the land that are set out in a recovery plan or threat abatement plan prepared under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 or the Fisheries Management Act 1994.

36J Core objectives for management of community land categorised as bushland

The core objectives for management of community land categorised as bushland are—

(a) to ensure the ongoing ecological viability of the land by protecting the ecological biodiversity and habitat values of the land, the flora and fauna (including invertebrates, fungi and micro-organisms) of the land and other ecological values of the land, and

(b) to protect the aesthetic, heritage, recreational, educational and scientific values of the land, and

(c) to promote the management of the land in a manner that protects and enhances the values and quality of the land and facilitates public enjoyment of the land, and to implement measures directed to minimising or mitigating any disturbance caused by human intrusion, and

(d) to restore degraded bushland, and

(e) to protect existing landforms such as natural drainage lines, watercourses and foreshores, and

(f) to retain bushland in parcels of a size and configuration that will enable the existing plant and animal communities to survive in the long term, and

(g) to protect bushland as a natural stabiliser of the soil surface.

Councils also have a range of functions, powers and responsibilities that can influence NRM on public and private land. This includes strategic planning and development control, managing public land, and regulating private activities. Natural Resource Management (NRM) activities include biosecurity, stormwater, biodiversity, roadside environmental management, water quality, as well as restoration and rehabilitation of habitat and support to local bush care and land care activities. They do not as yet specify any required response to wildlife in peril in these LGA's.

However, no council in Sydney states it is responsible for the wildlife living within these LGAs. No legislation directs them to do so.

All councils refer you on to wildlife organisations that exist solely because of volunteers who also pick up all the costs for saving local wildlife, as well as doing hundreds of hours of work each month to look after animals that come into care.

Council's Bushland and Biodiversity Policy Statement, published February 2021, outlines their own current commitments.

Male Superb Fairy Wren at Careel Bay playing fields - part of a colony that was here in 2012-2015 - now chased away by dog owners 'skitching' their dogs onto local birds

Decreasing Backyard Bird Diversity Flies Under The Radar

August 17, 2022

A deep dive into bird survey data has found that some of Australia’s favourite backyard visitors considered ‘common’ are actually on the decline as cities and suburbs opt for less greenery.

The study, led by Griffith University and published in Biological Conservation, used citizen science data to examine the prevalence and diversity of bird species across Greater Brisbane, Greater Sydney, Greater Perth and Greater Melbourne.

The team found that introduced species, historically prominent in Australian urban bird communities, were decreasing in prevalence in all four regions, while a small group of native urban exploiters were becoming more prevalent.

The results also showed that many species perceived to be “iconic” or “common” were experiencing declines in prevalence in urban areas, highlighting the importance of monitoring and conservation action in suburbs.

PhD candidate in Griffith’s Centre for Planetary Health and Food Security Carly Campbell said she wanted to get a broader look at bird communities across Australia see how they’re changing with the changing urban landscape.

Campbell said in the process, her research also highlighted the “support is crucial to ensure the conservation of some of our favourite backyard bird species”.

“It’s often the really rare or threatened species or the really charismatic ones that get a lot of research attention, but sometimes what’s happening to their communities as a whole can fly under the radar,” she said.

“So a lot of those considered common or non-threatened species might not necessarily have a lot of check ins, and the worry is that this kind of complacency about the conservation of these species might result in us missing some declines that are happening as our environments are changing so rapidly.”

Which species have been impacted?

The team used two databases with records spanning 1954 to present: Birdata which includes over 18 million records, and Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird project, which is a global programme containing over 600 million observations.

Examining Australia’s four most populous urban regions – Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney and Perth – the team pulled together all relevant bird survey records from the databases and their increases and declines over time using statistical modelling.

“We found that there are many species experiencing changes across the board. There was a really strong increase in noisy miner and the rainbow lorikeet. These birds are doing really well in cities and urban areas. This is bad for other species, as birds like the noisy miner are very aggressive and drive other species out of urban areas” Campbell said.

“We also found a lot of species going through declines, and it wasn’t just the rare and threatened ones – some were those considered common or iconic. So, in several of the areas, the galah and kookaburra were experiencing relative declines.

“What this paper overall highlights is that as much as we assume that a really large set of birds do well in urban areas and are still present, they’re actually starting to make up less of the diversity of species that are there.

“This might indicate that cities are moving towards a more homogenized set of species that you see there, to the loss of many others.”

Why is this happening?

Australians have been afforded a unique experience in being able to have frequent and richly diverse interactions with native birds in their own backyards, but Campbell said the concern was that not only are cities and suburbs expanding, but more and more people in urban areas were subdividing and removing trees, plants and bushes in the process.

“Birds act as a signal of ecosystem health – if there are lots of insect-eating birds around, usually that means you’ve got a lot of insects around, which indicates there’s healthy biodiversity,” she said.

“Also, our birds are really, really important pollinators in Australia, and they do a lot of work spreading seeds. Brush turkeys will turn over the soil and tend to leaf litter, and lyrebirds actually reduce fire risk by turning over leaf litter and help it break down.

“There are really important but unseen functions that birds play in our environments. So the loss of bird biodiversity is not only an indication of a breakdown of ecosystem functions, it’s also a loss for humans.”

Campbell also said there was a lot of evidence to suggest that larger birds have more competitive advantages in cities, and this is echoed in the paper which highlighted that smaller species bird were more likely to decline.

“This is usually because they can exploit more resources and are probably less vulnerable to predators. Birds that nest on the ground tend to have a much worse time as they have cats, dogs, cars and people to deal with so without the supporting plant life it’s a challenging place for small birds.

What can we do?

While Australia is currently experiencing a lot of housing development compounded with a lack of affordable shortages, Campbell said it was important for planners and homeowners to think about the best ways to not overly impact the habitats of “our amazingly diverse bird species that co-inhabit our backyards and suburbs”.

“We need to change how we’re structuring our vegetation, because what we do with the vegetation in cities and suburbs is really important as to what species thrive.”

“For example, the aggressive noisy miners are thriving in our suburbs, and this is because of us. They love isolated tall trees and nectar-rich flowering plants, and we have provided these in abundance. So city planners and homeowners should consider having a variety of different size and height native trees and shrubs to encourage other species.

“Planting more diverse forms of natives vegetation, particularly less nectar-rich species like wattles and she-oaks, can help maintain a diverse ecosystem that keeps encouraging a diversity of bird life to thrive in our cities and suburbs.”

The findings ‘Big changes in backyard birds: An analysis of long-term changes in bird communities in Australia’s most populous urban regions’ have been published in Biological Conservation.

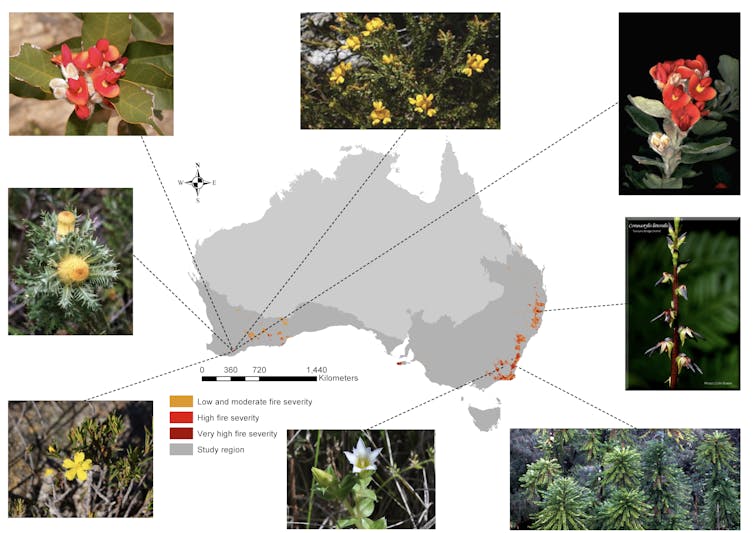

Wildlife recovery spending after Australia’s last megafires was one-thirteenth the $2.7 billion needed

Few could forget the devastating megafires that raged across southeast and western Australia during 2019-20. As well as killing people and destroying homes and towns, the fires killed wildlife and burnt up to 96,000km² of animal habitat – an area bigger than Hungary.

Under climate change, megafires will become increasingly common. This is likely to leave many species needing help at the same time, over vast areas. So our new research, released today, devised a way for conservation scientists and others to determine which actions, and where, will best help wildlife recover.

We also put a price tag on these measures. We found about A$2.7 billion should have been spent across Australia in the year after the megafires to mitigate all threats to 290 severely affected threatened animal and plant species. This is almost 13 times the funding dedicated by the former federal Coalition government.

The paltry spending means many species severely harmed by the megafires were left in desperate trouble, potentially pushing some closer to extinction.

The First Year Is Crucial

Many plant and animal species are especially vulnerable in the first year after a fire.

Fires can allow invasive weeds to invade and dominate burnt areas. This can hinder the ecosystem’s recovery, including making it more fire-prone.

Many native animals such as Kangaroo Island dunnart and long-footed potoroo rely on vegetation cover to avoid invasive predators such as feral cats and foxes. When fire removes this vegetation, native animals have nowhere to hide.

After a fire, any patches of unburnt vegetation are crucial for animals that survived. But invasive herbivores such as horses, deer, and pigs can graze on these food sources, leaving little for native wildlife.

For these reasons, the first year after a fire is usually the most important time to implement actions to help vulnerable species recover. Such actions can include:

- protecting habitat

- managing invasive plants and animals

- stopping native forest degradation associated with logging

- limiting damage from recreation activities

- managing disease.

But in the immediate aftermath of a fire, how do conservation scientists and others decide which species to help, and how? Which locations should they prioritise? And how does all this interact with other threats to wildlife such as land clearing and feral predators?

To date, decision-makers around the world have largely used a method known as the “site richness” approach to prioritise conservation actions. This approach concentrates actions in locations where the greatest number of species can be recovered.

But this approach can mean some high-risk species may not get the help they need, while other less critical species receive disproportionately high assistance.

For example, research from China has showed relying entirely on this method meant species of woody plants found only across a small range – and therefore potentially vulnerable – missed out on conservation actions.

Our New Approach

Our new research devised and assessed an alternative method. Known as the “complementarity” approach, it ensures conservation actions occur across the habitats of all threatened species. It involves combining data about:

- the distribution of species and threats

- fire extent and intensity

- a species’ risk of severe, irreversible decline after a fire.

From that, decisions can be made about which of the 22 conservation actions should be carried out first, and where. It prioritises locations where threats affect multiple species – making it more cost-effective to deal with them – and where actions at one site can be easily extended to nearby areas.

We then applied our framework to the 2019–2020 bushfires to identify the most at-risk species, the actions needed to save them, the best locations for these actions, and the costs.

Our approach identified 290 threatened species needing immediate conservation attention. They spanned mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs, insects, and plants.

Each species required, on average, three conservation actions to mitigate threats. The top three were habitat protection (all species), fire suppression (57% of species) and invasive plant management (36% of species).

We then prioritised cost-effective actions after the fires, using our approach. We found actions should take place in 179 geographic areas, including the Snowy Mountains in New South Wales and Gippsland in Victoria.

Actions in these regions recovered the highest number of at-risk species – such as koalas, greater gliders and regent honeyeaters – for the least cost.

We found A$2.7 billion would be needed to mitigate all threats to 290 species in the year after the megafires.

But the previous federal government committed just $200 million to post-fire recovery actions. Some $50 million of this was delivered relatively quickly. But the remainder was to be delivered over two years from July 2020 – beyond the timeframe in which many species required urgent help.

Heeding The Lessons

Our research shows the potential gains from alternative approaches to conservation after devastating fires. It also underscores the need for adequate government funding, delivered quickly, to help species most in need.

It’s worth remembering the loss of habitat from bushfires often compounds decades of land clearing. As Australia faces an ever-worsening bushfire risk, we urge Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek to prevent further loss of threatened species habitat.

Michelle Ward, Postdoctoral research fellow, The University of Queensland; Ayesha Tulloch, ARC Future Fellow, Queensland University of Technology, and James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.