July 30 - August 5, 2017: Issue 323

Retracing Governor Phillip's Footsteps around Pittwater:

The Mystery of the Cove on the East Side

Roger Sayers and Geoff Searl

‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales. March 1788'. Image No.: a3461013h. Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

Retracing Governor Phillip's Footsteps around Pittwater:

The Mystery of the Cove on the East Side

by Roger Sayers and Geoff Searl

By Roger Sayers And Geoff Searl [i.]

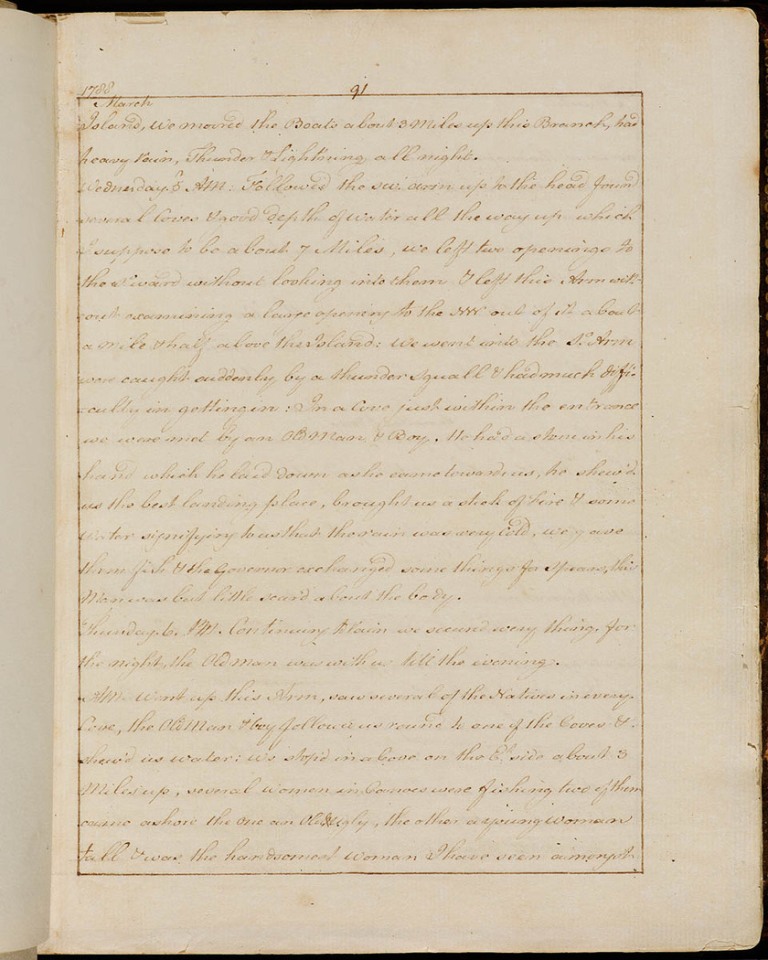

A sentence in Lieutenant William Bradley’s journal [ii.] for 6 March 1788 intrigued us when we were doing research for our first expedition to retrace Governor Phillip’s ‘footsteps’ around Pittwater[iii.]:

We stop'd in a Cove on the E.t. side about 3 Miles up... [iv.]

Governor Phillip, Lieutenant William Bradley and a party of sailors and marines explored Broken Bay from 2 to 9 March 1788 in search of potentially suitable places to grow food, vital for the newly established colony at Sydney Cove. Phillip’s journey included the first European exploration of Pittwater and the first recorded encounters with local aborigines.

We thought Bradley’s reference to a cove on the east side of Pittwater must mean Careel Bay. It seemed strange we hadn’t heard of Phillip landing at Careel Bay before, so we decided we’d investigate further. [v.]

We explored possible sites in Careel Bay where Phillip might have landed, based on the information in Bradley’s journal. Soon, however, we began to have doubts about Careel Bay being Bradley’s Cove. But if it wasn’t Careel Bay, then where could Bradley have meant?

Further investigation more often than not led to more questions, but we now believe we’ve solved this little mystery and identified the cove, the second location in Pittwater where Governor Phillip is recorded to have come ashore and met local aborigines.

We compared the first-hand observations we made in the course of several boat and shore excursions with the historical descriptions. The detailed 1990 work of Shelagh and George Champion [vi] helped guide us. We are also grateful for the assistance of staff at the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

Extracts from Lt W Bradley’s journal are reproduced in italics.

The morning of 6 March 1788

[Thursday. 6.] A.M. Went up this Arm, saw several of the Natives in every Cove, the Old Man & boy followed us round to one of the Coves & shew’d us Water...

On the morning of 6 March 1788 Governor Phillip, Lt Bradley and a party of sailors and marines set off, we believe, from West Head Beach, where they had camped overnight. They likely began the day’s exploration around 7am when it was high tide [vii] so that the Governor’s cutter and a longboat could navigate more easily between the rocks in front of the beach.

Weather conditions throughout Phillip’s first journey to Broken Bay and Pittwater were challenging, with constant rain and wind changes. The wind was WNW that morning according to Bradley’s record, so they probably began by rowing southward to the nearby coves along the western shoreline of Pittwater -¬ coves now known as Resolute, Mackerel and Currawong Beaches and Coasters Retreat (The Basin).

An old aboriginal man and a boy who had guided them through the rocks at West Head Beach the night before, followed them to one of the coves and showed them where they could find fresh water.

Bradley doesn’t say which cove or whether or not they went ashore, but the freshwater stream at Mackerel Beach, for instance, could have been pointed out to them and seen from the boats, as it runs across the beach when the catchment is full after rain. [viii]

As they travelled along the shoreline they would also have seen that there was very little flat land suitable for food cultivation to be found on the steep, rocky western side of Pittwater.

Directly east of Coasters Retreat is the entrance to Careel Bay and an area of flat land on Sandy Point.

Bradley’s next journal entry is:

We stop'd in a Cove on the E.t. side about 3 Miles up, several Women in Canoes were fishing two of them came ashore the one an Old & Ugly, the other a young Woman tall & was the handsomest Woman I have seen amongst them, she was very big with Child, her fingers were complete as were those of the Old Woman. One of the Women made a fishing hook while we were by her, from the inside of what is commonly called the pearl oyster shell, by rubbing it down on the rocks until thin enough & then cut it circular with another, shape the hook with a sharp point rather bent in & not bearded or barbed, in this Cove we met with a kernel which they prepare & give their Children, I have seen them eat it themselves, they are a kind of Nut growing in bunches somewhat like a pine top & are poisonous without being properly prepared the method of doing which we did not learn from them [cycads]. [ix]

It seemed to us so obvious that Careel Bay was where Bradley was referring to that we didn’t check initially whether Careel Bay was in fact about 3 Miles up.

We set about looking for possible locations in Careel Bay where Phillip might have landed: places that seemed to fit Bradley’s descriptions and were near early aboriginal sites (middens) - making them likely places where aboriginal women might have fished offshore from canoes and have come ashore to make fishhooks from oyster shells gathered from the rocks - and also near where the explorers might have seen cycads. We found a couple of locations that met all the requirements. One seemed particularly promising.

But we soon realised that (oops) we hadn’t yet measured the distance to see how far ‘up’ Careel Bay is from the entrance to Pittwater, at West Head Beach. And what kind of ‘miles’ was Bradley measuring?

If Bradley had meant normal miles, 3 miles equates to 4.8 kilometres. But as Bradley was a Naval officer, we figured that more than likely he would have meant 3 nautical or Admiralty miles, which are equivalent to 5.6 kilometres.[x] Despite some further confusion, as we later explain, nautical miles seem to have been the correct assumption.

Careel Bay’s entrance is only about 2.5 to 3.5 kilometres ‘up Pittwater’. [xi] So Careel Bay is not far enough south of West Head Beach in either miles or nautical miles to match Bradley’s description.

But there is no other obvious cove on the east side of Pittwater in that vicinity. The shoreline from Stokes Point (the southern headland of Careel Bay) to Taylors Point (the next prominent feature) is pretty much a continuous stretch of rocky foreshore and beaches [xii].

The mystery of the Cove

We considered a number of factors to work out where it was that Bradley meant and whereabouts they might have sailed after leaving Coasters Retreat.

First we looked at Bradley’s weather observations, which he recorded at noon each day:

March 1788

6th 74 degrees, wind WNW & SE, Fresh Gales with Rain

It seems likely they would have hauled up their sails to head out of Coasters Retreat and take advantage of the WNW wind to sail across to the eastern side of Pittwater. It’s possible that as they rounded the headland they saw coming, or may have experienced by then, the gale force SE wind change recorded by Bradley.

They would have wanted to distance themselves from the lee rocky western shore, especially after their sobering experience of gusty southerly squalls the night before when they came around West Head from the direction of the Hawkesbury River.

While they might have considered entering Careel Bay, it seems more likely they would not have wanted to chance it in such bad weather.

We believe they more likely sailed across Pittwater toward the eastern shoreline to head south, as they would have been able to see a stretch of land to the southeast of them that could offer some shelter from the SE wind and weather, in the vicinity of present-day Taylors Point.

Shelagh and George Champion’s detailed (1990) [xiii] research gave us some guidance:

‘They spent 6th March exploring Pittwater, and it was apparently on this day that Bradley illustrated the scene, looking northwards towards Lion Island.’

Bradley drew his well-known sketch of Pittwater, dated simply ‘March 1788’, in the vicinity of Taylors Point. Taylors Point wharf is approximately 5.8 kilometres south of West Head Beach, which closely corresponds to Bradley’s estimate of 5.6 kilometres (3 nautical miles).

Figure 6: ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales. March 1788'. Image No.: a3461013h. Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. IE number: IE1113857. This is the earliest European depiction of Pittwater.

Bradley records in his journal that several Women in Canoes were fishing near where they stopped.

And the sketch he drew in the vicinity of Taylors Point shows several native canoes offshore, where Phillip’s party are stop'd ... on the E.t. side of Pittwater.

We also found oysters on the rocks and cycads below the estimated location of the sketch site, matching Bradley’s other journal observations.

So it seemed highly likely that the sketch scene location would also be the location of Bradley’s Cove.

But if that’s the place, where’s the Cove??

The answer lies partly in different understandings of what constitutes a cove. We had in mind that Bradley meant an inlet. The Concise Macquarie Dictionary of Australian English defines cove as ‘a small indentation or recess in the shoreline of a sea, lake, or river’. [xiv.]

But according to the Cambridge Dictionary, cove in British English (as distinct from Australian or American English) means ‘a curved part of the coast that partly surrounds an area of water’.

The beach at Clareville curves gently toward Taylors Point and forms a cove in the British sense of the word, especially when approached from the north along the eastern shoreline, as we believe Phillip and Bradley would likely have done. [xv.]

Figure 7: Approached from the north, Clareville Beach shows a distinct curve, matching the definition of a ‘cove’ in the British English sense. Bradley’s sketch was drawn from a vantage point above the beach, near the centre left of this photograph.

The distance we travelled by boat when we followed Governor Phillip’s most likely route down Pittwater was 5.55 kilometres (by satellite track) from West Head Beach to just off Clareville Beach. This equates to 3 nautical miles. That fact, and a Broken Bay chart containing the first map of Pittwater (discussed further in the section below), supported our original assumption that 3 Miles up in Bradley’s journal refers to nautical miles.

By comparing Bradley’s sketch with our own observations of the area, we believe his sketch was most likely drawn from a location above the southern end of Clareville Beach, rather than nearer Taylors Point itself.

Figure 8: The view from a boat stopped just off Clareville Beach. We believe Governor Phillip’s most likely landing place was along this stretch of sand. Bradley’s sketch was drawn from a vantage point above the beach, near the centre of the photograph.

Bradley might have thought it would be self-evident to readers that he drew the sketch when the party had stop'd, as he recorded in his journal. But while he gave detailed descriptions of the aboriginal women coming ashore to make fish hooks from oyster shells gathered from the rocks, and of seeing what we now believe to have been cycads for the first time, there is nothing more in Bradley’s journal to describe or explain the sketch scene itself,¬ despite it suggesting a noteworthy event.

It seems likely that Bradley may have used some artistic licence in drawing his sketch to depict the friendly nature of the encounter with the local aborigines.

The afternoon of 6 March 1788

Bradley finishes his record of this first day of the earliest European exploration of Pittwater as follows:

Hard rain the greatest part of these 24 Hours.

[P.M.] Were at the upper part of the So. Arm,[South Arm of Broken Bay] found in every part of it, very good depth of Water except a Flat at the entrance from the Est. point 2/3 of the way over, between which & the W.ern shore is a Channel with 3fm at low Water & that depth close to the rocks, the Land on the Est. side of this Arm is in general good & clear, on the W. side all Rocks & thick Woods.

He doesn’t say where in the upper part of Pittwater they spent the night of the 6th, but it may have been on board their boats, as they had done previously. On the morning of the 7th they left Pittwater to further explore the SW Arm of Broken Bay and examine the entrance to the Hawkesbury. They returned to Pittwater on the evening of the 8th to camp once again at West Head Beach, as we believe, before departing Broken Bay the following day to return to Sydney.

Governor Phillip’s summary of his first visit to Pittwater

Summary of our findings

While we cannot be certain on some points, after following in Phillip’s ‘footsteps’ around Pittwater we believe we can say with a fair degree of certainty that:

Further material for the interested reader

1789 Charts published in Bradley’s journal

Because we like to try to dot our i’s and cross our t’s, and as we hadn’t been able to confirm from our reference searches our early assumption that Bradley’s 3 Miles up referred to nautical miles, we sought the advice of staff at the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

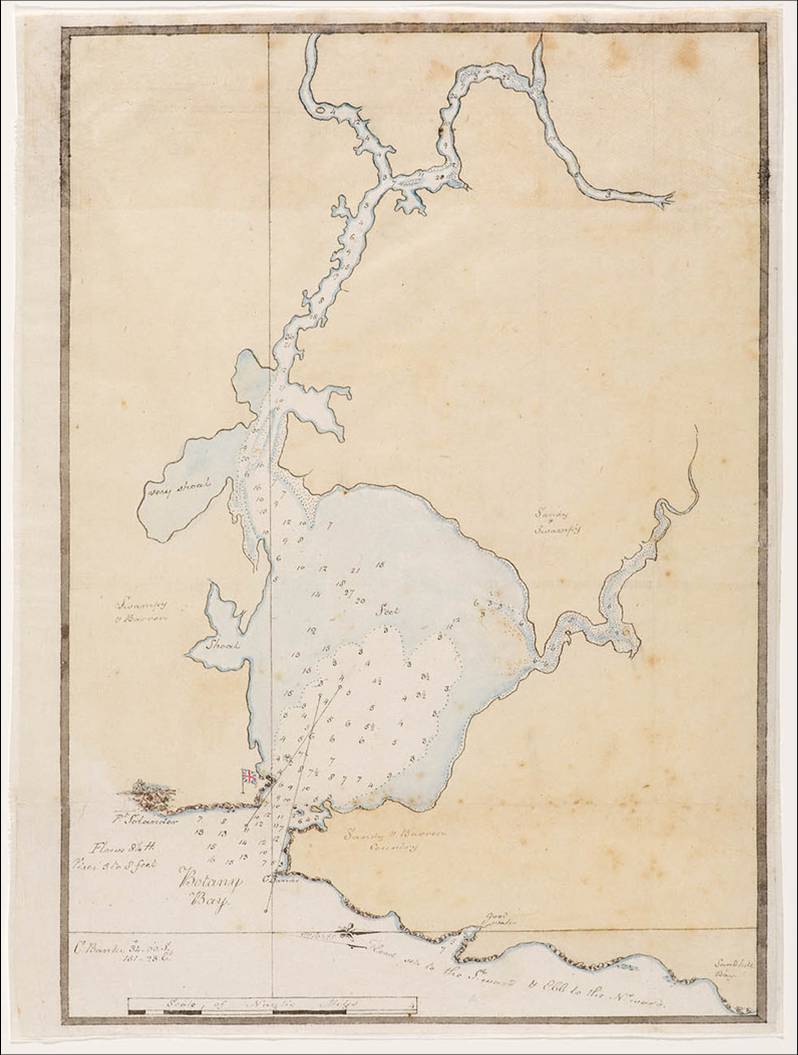

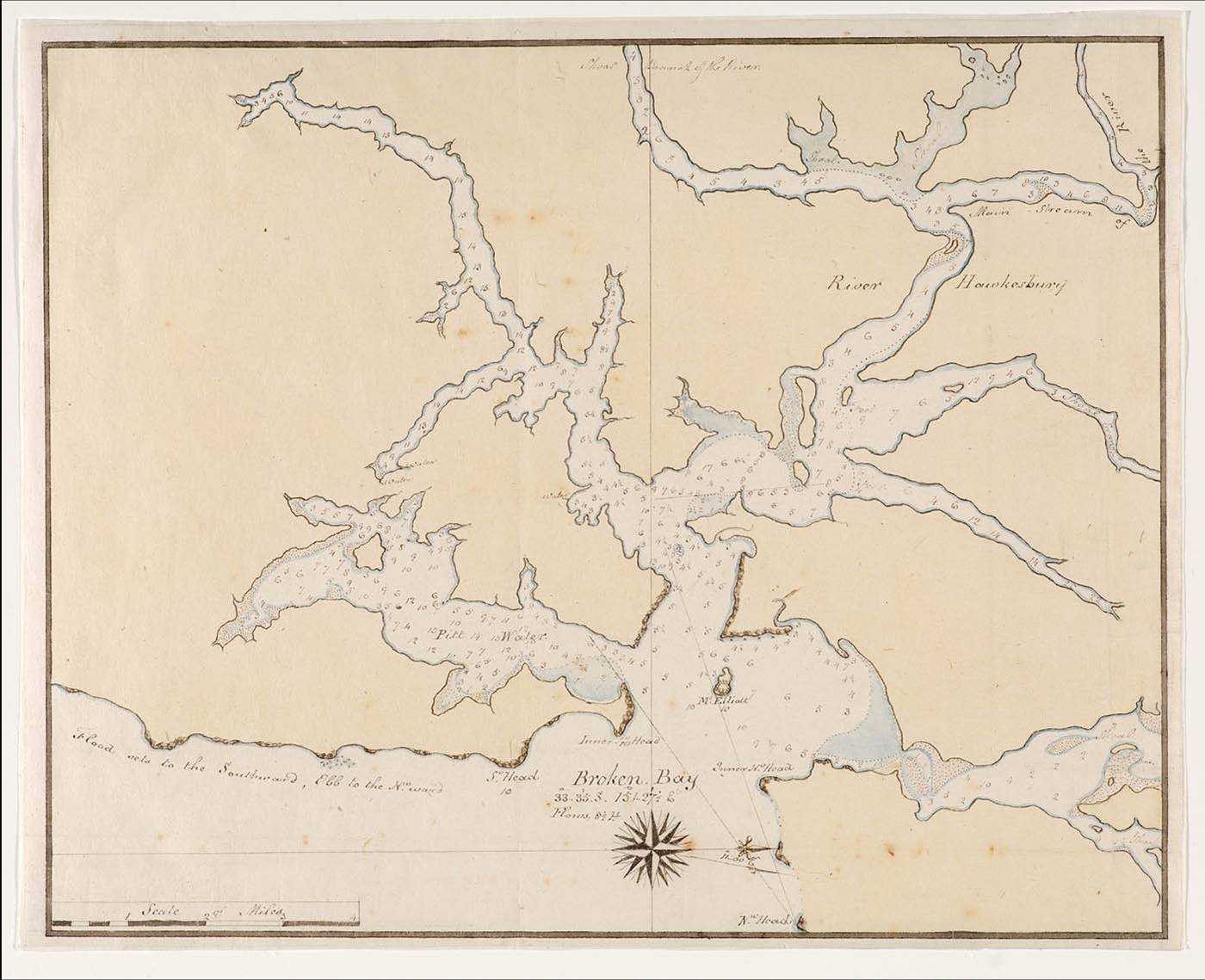

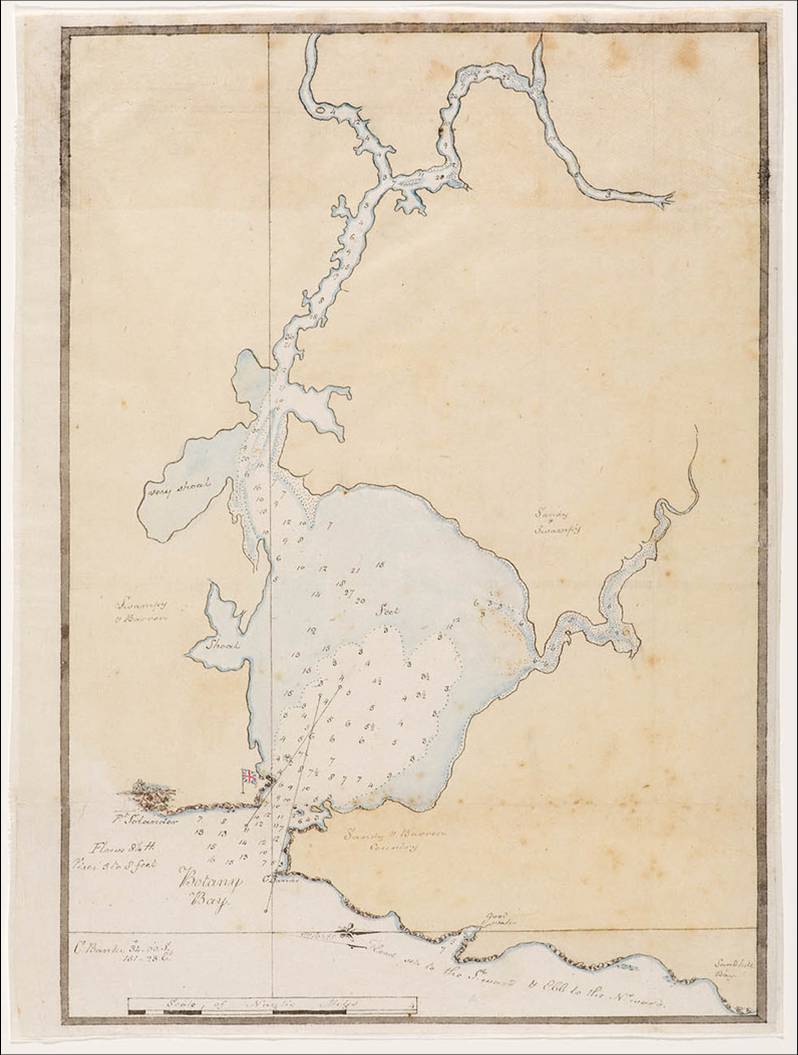

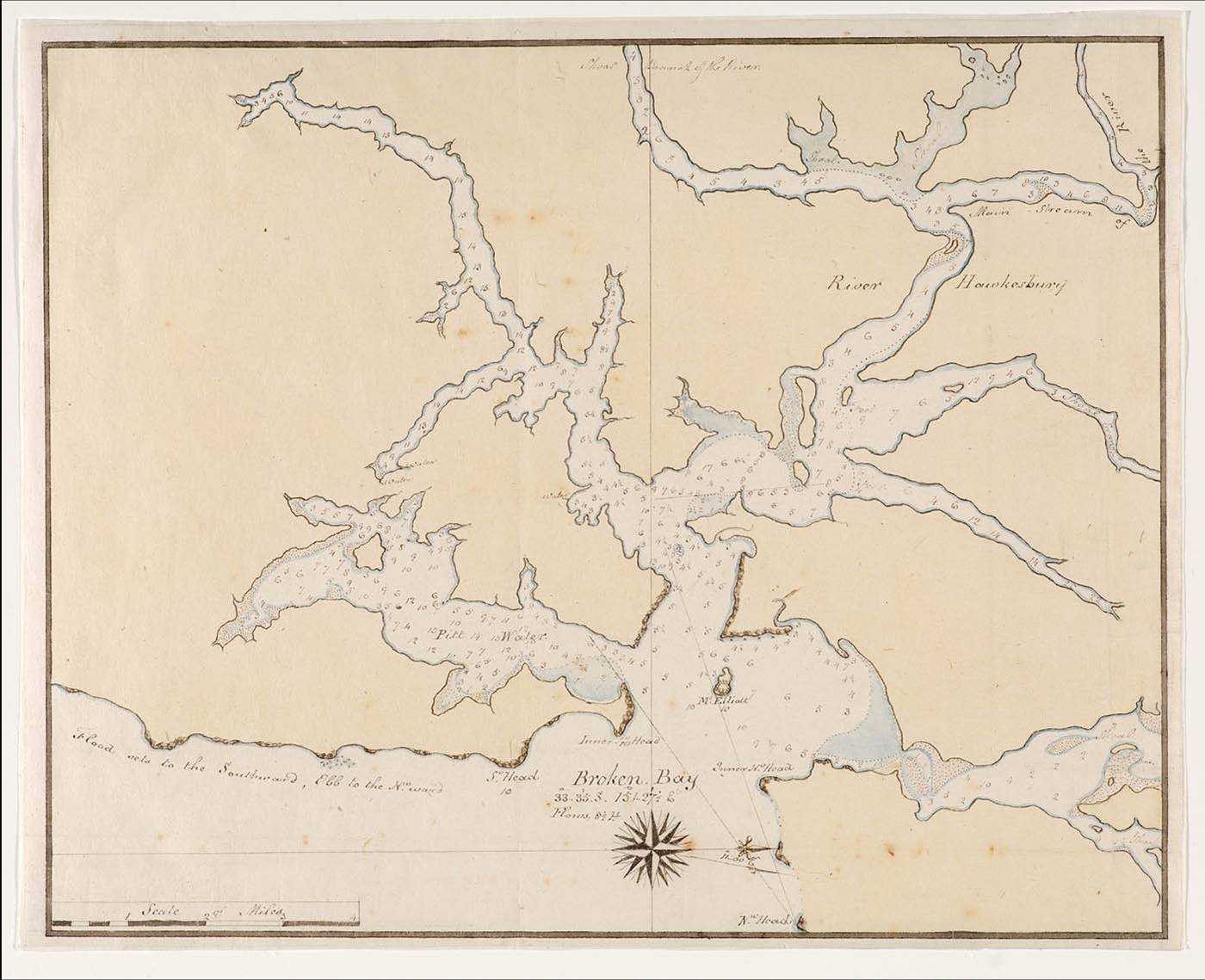

The Library staff were very helpful but said they couldn’t say for sure. They could not find any reference in Bradley’s published journal, A voyage to New South Wales, 1786-1792 to the specific identification of measurements. Some of the charts in his journal are labelled with a ‘Scale of Nautic Miles’ (such as the chart of Botany Bay shown in Figure 14) and some are labelled with a ‘Scale of Miles’ (such as the chart of Broken Bay shown in Figure 15, which incorporates the first map of Pittwater).

The ‘Nautic Miles’ on the Botany Bay chart provided us with a strong clue. When we measured the distance from West Head Beach to Taylors Point on the 1789 Broken Bay chart, we found that it almost exactly matches 3 ‘Miles’ according to the chart’s scale, strongly suggesting that the ‘Miles’ in this case in fact refer to ‘Nautic Miles’. This was confirmed when we measured this distance ourselves in kilometres on our journey.

We then found from referring to other work by the Champions [xvii] that the surveys of Botany Bay and Broken Bay were both carried out in the same month, August 1789 (more than a year after Bradley’s first excursion to Pittwater), by the same people, Captain Hunter and Lt Bradley. It seems highly unlikely that they would have used differing scales on the two maps.

We suggest it would have been self-evident to Naval people at the time that ‘mile’ measurements on navigation charts meant nautical miles and not land miles. So despite the anomaly in labelling, it seems logical to assume that the scales on both charts refer to ‘Nautic’ or nautical miles, and that Bradley’s journal entries similarly refer to nautical miles.

We also tried another tack and asked the Mitchell Library staff if Bradley recorded the latitude and longitude for his noon reading on 6 March 1788. But he did not do this during the party’s travels around Broken Bay, presumably because the weather conditions would have made such observations impossible.

Bradley’s sketch and the time spent at Clareville/Taylors Point

Phillip’s party must have spent some time at Clareville/Taylors Point for Bradley to have been able to draw at least the basic details of his sketch, take a break on land and make his other observations, yet (as mentioned earlier) Bradley made no other entries in his journal to describe the details shown in the sketch. It also seems likely that Clareville/Taylors Point would have provided a convenient sheltered location to drop anchor around noon and break the day’s excursions around Pittwater, given the bad weather.

We estimate that it would have taken Bradley at least 20 to 30 minutes to do even his basic sketch, based on Roger’s rough on-site sketch shown below. Bradley customarily finished his sketches later, filling in parts from memory.

Figure 9: Roger’s rough sketch drawn on site to assess the time necessary to include the main features captured in Bradley’s sketch.

This exercise also revealed that Bradley would have needed to use some artistic licence to highlight the key features that he wanted to record (or perhaps that Phillip asked him to record) for Naval and food-growing purposes.

For example, Bradley highlighted the folds in the hills to show bays and coves; he exaggerated the reefs at the points on the western foreshore, as well as the height of the land when seen from his vantage point; and he drew attention to the flat land around Sandy Point by drawing a number of thinned out individual palm trees (some planted cabbage tree palms are there today) to distinguish it from the more thickly vegetated hills.

Bradley’s illustration was not meant to be a work of art but was essentially a working guide to what others could expect to find in Pittwater. Drawing was part of a naval officer’s training at a time before the invention of photography.

Even a photograph of this scene, especially one taken on an overcast day, may not show the aspects a Naval officer exploring new areas would have wanted to note. Compare the details in the two sketches with the lack of clarity of some features in the photograph below (Figure 10).

Bradley’s observations of oyster shells and cycads

Bradley’s journal description of oysters on the rocks and cycads could have applied equally to Careel Bay and Taylors Point. The photographs below (Figures 11 and 12) were taken near Bradley’s sketch site.

...several Women in Canoes were fishing two of them came ashore the one an Old & Ugly, the other a young Woman tall & was the handsomest Woman I have seen amongst them, she was very big with Child, her fingers were complete as were those of the Old Woman. One of the Women made a fishing hook while we were by her, from the inside of what is commonly called the pearl oyster shell, by rubbing it down on the rocks until thin enough & then cut it circular with another, shape the hook with a sharp point rather bent in & not bearded or barbed...

Figure 11: Oysters on the rocks today below Bradley’s sketch site.

... in this Cove we met with a kernel which they prepare & give their Children, I have seen them eat it themselves, they are a kind of Nut growing in bunches somewhat like a pine top & are poisonous without being properly prepared the method of doing which we did not learn from them.

Figure 12: Cycads growing in the bush today, next to a grey spotted gum, below Bradley’s sketch site.

Figure 13: Extract from Lt W Bradley’s journal entry for 6 March 1788 (page 91). Image No.: a138091h Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved from http://digital.sl.nsw.gov.au/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=FL1614777&embedded=true&toolbar=false

When measured using the scale shown on this chart, the distance from West Head Beach at the entrance to ‘PittWater’ to Taylors Point is approximately 3 ‘Miles’. The distance between the same points as measured on maps today is approximately 5.8 kilometres, which closely corresponds to 3 nautical miles (5.6 kilometres).

We stop'd in a Cove on the E.t. side about 3 Miles up... [iv.]

Governor Phillip, Lieutenant William Bradley and a party of sailors and marines explored Broken Bay from 2 to 9 March 1788 in search of potentially suitable places to grow food, vital for the newly established colony at Sydney Cove. Phillip’s journey included the first European exploration of Pittwater and the first recorded encounters with local aborigines.

We thought Bradley’s reference to a cove on the east side of Pittwater must mean Careel Bay. It seemed strange we hadn’t heard of Phillip landing at Careel Bay before, so we decided we’d investigate further. [v.]

We explored possible sites in Careel Bay where Phillip might have landed, based on the information in Bradley’s journal. Soon, however, we began to have doubts about Careel Bay being Bradley’s Cove. But if it wasn’t Careel Bay, then where could Bradley have meant?

Further investigation more often than not led to more questions, but we now believe we’ve solved this little mystery and identified the cove, the second location in Pittwater where Governor Phillip is recorded to have come ashore and met local aborigines.

We compared the first-hand observations we made in the course of several boat and shore excursions with the historical descriptions. The detailed 1990 work of Shelagh and George Champion [vi] helped guide us. We are also grateful for the assistance of staff at the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

* * *

Figure 1: Pittwater and Broken Bay plaque at Lucinda Park, Sandy Point, Palm Beach, New South Wales.

Extracts from Lt W Bradley’s journal are reproduced in italics.

The morning of 6 March 1788

[Thursday. 6.] A.M. Went up this Arm, saw several of the Natives in every Cove, the Old Man & boy followed us round to one of the Coves & shew’d us Water...

On the morning of 6 March 1788 Governor Phillip, Lt Bradley and a party of sailors and marines set off, we believe, from West Head Beach, where they had camped overnight. They likely began the day’s exploration around 7am when it was high tide [vii] so that the Governor’s cutter and a longboat could navigate more easily between the rocks in front of the beach.

Weather conditions throughout Phillip’s first journey to Broken Bay and Pittwater were challenging, with constant rain and wind changes. The wind was WNW that morning according to Bradley’s record, so they probably began by rowing southward to the nearby coves along the western shoreline of Pittwater -¬ coves now known as Resolute, Mackerel and Currawong Beaches and Coasters Retreat (The Basin).

Figure 2: Western shore of Pittwater from just off West Head Beach, looking south to Resolute Beach, Mackerel Beach and Coasters Retreat. (Currawong Beach is behind the third headland.)

An old aboriginal man and a boy who had guided them through the rocks at West Head Beach the night before, followed them to one of the coves and showed them where they could find fresh water.

Bradley doesn’t say which cove or whether or not they went ashore, but the freshwater stream at Mackerel Beach, for instance, could have been pointed out to them and seen from the boats, as it runs across the beach when the catchment is full after rain. [viii]

Figure 3: Mackerel Beach, looking much as it would have in 1788. The freshwater stream running across the beach is visible from a boat offshore.

As they travelled along the shoreline they would also have seen that there was very little flat land suitable for food cultivation to be found on the steep, rocky western side of Pittwater.

Directly east of Coasters Retreat is the entrance to Careel Bay and an area of flat land on Sandy Point.

Figure 4: Looking east from Coasters Retreat toward the entrance of Careel Bay (centre) and an area of flat land on Sandy Point (left).

Bradley’s next journal entry is:

We stop'd in a Cove on the E.t. side about 3 Miles up, several Women in Canoes were fishing two of them came ashore the one an Old & Ugly, the other a young Woman tall & was the handsomest Woman I have seen amongst them, she was very big with Child, her fingers were complete as were those of the Old Woman. One of the Women made a fishing hook while we were by her, from the inside of what is commonly called the pearl oyster shell, by rubbing it down on the rocks until thin enough & then cut it circular with another, shape the hook with a sharp point rather bent in & not bearded or barbed, in this Cove we met with a kernel which they prepare & give their Children, I have seen them eat it themselves, they are a kind of Nut growing in bunches somewhat like a pine top & are poisonous without being properly prepared the method of doing which we did not learn from them [cycads]. [ix]

It seemed to us so obvious that Careel Bay was where Bradley was referring to that we didn’t check initially whether Careel Bay was in fact about 3 Miles up.

We set about looking for possible locations in Careel Bay where Phillip might have landed: places that seemed to fit Bradley’s descriptions and were near early aboriginal sites (middens) - making them likely places where aboriginal women might have fished offshore from canoes and have come ashore to make fishhooks from oyster shells gathered from the rocks - and also near where the explorers might have seen cycads. We found a couple of locations that met all the requirements. One seemed particularly promising.

But we soon realised that (oops) we hadn’t yet measured the distance to see how far ‘up’ Careel Bay is from the entrance to Pittwater, at West Head Beach. And what kind of ‘miles’ was Bradley measuring?

If Bradley had meant normal miles, 3 miles equates to 4.8 kilometres. But as Bradley was a Naval officer, we figured that more than likely he would have meant 3 nautical or Admiralty miles, which are equivalent to 5.6 kilometres.[x] Despite some further confusion, as we later explain, nautical miles seem to have been the correct assumption.

Careel Bay’s entrance is only about 2.5 to 3.5 kilometres ‘up Pittwater’. [xi] So Careel Bay is not far enough south of West Head Beach in either miles or nautical miles to match Bradley’s description.

But there is no other obvious cove on the east side of Pittwater in that vicinity. The shoreline from Stokes Point (the southern headland of Careel Bay) to Taylors Point (the next prominent feature) is pretty much a continuous stretch of rocky foreshore and beaches [xii].

The mystery of the Cove

We considered a number of factors to work out where it was that Bradley meant and whereabouts they might have sailed after leaving Coasters Retreat.

First we looked at Bradley’s weather observations, which he recorded at noon each day:

March 1788

6th 74 degrees, wind WNW & SE, Fresh Gales with Rain

It seems likely they would have hauled up their sails to head out of Coasters Retreat and take advantage of the WNW wind to sail across to the eastern side of Pittwater. It’s possible that as they rounded the headland they saw coming, or may have experienced by then, the gale force SE wind change recorded by Bradley.

They would have wanted to distance themselves from the lee rocky western shore, especially after their sobering experience of gusty southerly squalls the night before when they came around West Head from the direction of the Hawkesbury River.

While they might have considered entering Careel Bay, it seems more likely they would not have wanted to chance it in such bad weather.

We believe they more likely sailed across Pittwater toward the eastern shoreline to head south, as they would have been able to see a stretch of land to the southeast of them that could offer some shelter from the SE wind and weather, in the vicinity of present-day Taylors Point.

Figure 5: Leaving Coasters Retreat, looking south. Note the continuation of steep land unsuitable for agriculture on the western shore at right and land offering shelter from the southeast wind in the vicinity of Taylors Point in the centre distance.

Shelagh and George Champion’s detailed (1990) [xiii] research gave us some guidance:

‘They spent 6th March exploring Pittwater, and it was apparently on this day that Bradley illustrated the scene, looking northwards towards Lion Island.’

Bradley drew his well-known sketch of Pittwater, dated simply ‘March 1788’, in the vicinity of Taylors Point. Taylors Point wharf is approximately 5.8 kilometres south of West Head Beach, which closely corresponds to Bradley’s estimate of 5.6 kilometres (3 nautical miles).

Bradley records in his journal that several Women in Canoes were fishing near where they stopped.

And the sketch he drew in the vicinity of Taylors Point shows several native canoes offshore, where Phillip’s party are stop'd ... on the E.t. side of Pittwater.

We also found oysters on the rocks and cycads below the estimated location of the sketch site, matching Bradley’s other journal observations.

So it seemed highly likely that the sketch scene location would also be the location of Bradley’s Cove.

But if that’s the place, where’s the Cove??

The answer lies partly in different understandings of what constitutes a cove. We had in mind that Bradley meant an inlet. The Concise Macquarie Dictionary of Australian English defines cove as ‘a small indentation or recess in the shoreline of a sea, lake, or river’. [xiv.]

But according to the Cambridge Dictionary, cove in British English (as distinct from Australian or American English) means ‘a curved part of the coast that partly surrounds an area of water’.

The beach at Clareville curves gently toward Taylors Point and forms a cove in the British sense of the word, especially when approached from the north along the eastern shoreline, as we believe Phillip and Bradley would likely have done. [xv.]

The distance we travelled by boat when we followed Governor Phillip’s most likely route down Pittwater was 5.55 kilometres (by satellite track) from West Head Beach to just off Clareville Beach. This equates to 3 nautical miles. That fact, and a Broken Bay chart containing the first map of Pittwater (discussed further in the section below), supported our original assumption that 3 Miles up in Bradley’s journal refers to nautical miles.

By comparing Bradley’s sketch with our own observations of the area, we believe his sketch was most likely drawn from a location above the southern end of Clareville Beach, rather than nearer Taylors Point itself.

Bradley might have thought it would be self-evident to readers that he drew the sketch when the party had stop'd, as he recorded in his journal. But while he gave detailed descriptions of the aboriginal women coming ashore to make fish hooks from oyster shells gathered from the rocks, and of seeing what we now believe to have been cycads for the first time, there is nothing more in Bradley’s journal to describe or explain the sketch scene itself,¬ despite it suggesting a noteworthy event.

It seems likely that Bradley may have used some artistic licence in drawing his sketch to depict the friendly nature of the encounter with the local aborigines.

The afternoon of 6 March 1788

Bradley finishes his record of this first day of the earliest European exploration of Pittwater as follows:

Hard rain the greatest part of these 24 Hours.

[P.M.] Were at the upper part of the So. Arm,[South Arm of Broken Bay] found in every part of it, very good depth of Water except a Flat at the entrance from the Est. point 2/3 of the way over, between which & the W.ern shore is a Channel with 3fm at low Water & that depth close to the rocks, the Land on the Est. side of this Arm is in general good & clear, on the W. side all Rocks & thick Woods.

He doesn’t say where in the upper part of Pittwater they spent the night of the 6th, but it may have been on board their boats, as they had done previously. On the morning of the 7th they left Pittwater to further explore the SW Arm of Broken Bay and examine the entrance to the Hawkesbury. They returned to Pittwater on the evening of the 8th to camp once again at West Head Beach, as we believe, before departing Broken Bay the following day to return to Sydney.

Governor Phillip’s summary of his first visit to Pittwater

Immediately round the head land that forms the Southern entrance into the Bay, there is a third Branch, which I think the finest piece of Water I ever saw, and which I honoured with the name of Pitt Water, it is as well as the Southwest branch, of sufficient extent to contain all the Navy of Great Britain, but has only eighteen feet at low water, on a narrow bar, which runs across the entrance. Within the bar there are from seven to fifteen fathom water. The land here is not so high as in the Southwest branch, and there are some good situations where the land might be cultivated. We found small springs of Water in most of the Coves, and saw three Cascades falling from a height, which the rains then rendered inaccessible. I returned to Port Jackson, after being absent eight days in the Boats; some of the People feeling the effects of the Rain, which had been almost constant, prevented my returning by land as I intended in order to examine a part of the Country which appeared open, and free from Timber.

Summary of our findings

While we cannot be certain on some points, after following in Phillip’s ‘footsteps’ around Pittwater we believe we can say with a fair degree of certainty that:

- Bradley’s Cove on the E.t. side is Clareville’s sandy beach.

- Bradley drew the first elements of his sketch labelled ‘March 1788 view in Broken Bay’ from a vantage point above the rocks at the southern end of Clareville Beach on 6 March 1788, confirming the Champions’ earlier thoughts on the date. In drawing the sketch Bradley used some artistic licence to depict aspects that he wished to feature. Governor Phillip and his party likely spent some time in that vicinity, to break the day’s journey and shelter from the bad weather.

- Bradley’s estimate of 3 Miles up (Pittwater) refers to nautical miles, as confirmed by the equivalent kilometre measurement of our journey and also by subsequent reference to other maps from this period (see the note below and Figure 15).

- The distances on a chart of Broken Bay (discussed below) prepared from a survey by Captain Hunter and Lt Bradley in 1789 correspond to nautical miles, despite the chart bearing a ‘Scale of Miles’ (see Figure 15).

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Further material for the interested reader

1789 Charts published in Bradley’s journal

Because we like to try to dot our i’s and cross our t’s, and as we hadn’t been able to confirm from our reference searches our early assumption that Bradley’s 3 Miles up referred to nautical miles, we sought the advice of staff at the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

The Library staff were very helpful but said they couldn’t say for sure. They could not find any reference in Bradley’s published journal, A voyage to New South Wales, 1786-1792 to the specific identification of measurements. Some of the charts in his journal are labelled with a ‘Scale of Nautic Miles’ (such as the chart of Botany Bay shown in Figure 14) and some are labelled with a ‘Scale of Miles’ (such as the chart of Broken Bay shown in Figure 15, which incorporates the first map of Pittwater).

The ‘Nautic Miles’ on the Botany Bay chart provided us with a strong clue. When we measured the distance from West Head Beach to Taylors Point on the 1789 Broken Bay chart, we found that it almost exactly matches 3 ‘Miles’ according to the chart’s scale, strongly suggesting that the ‘Miles’ in this case in fact refer to ‘Nautic Miles’. This was confirmed when we measured this distance ourselves in kilometres on our journey.

We then found from referring to other work by the Champions [xvii] that the surveys of Botany Bay and Broken Bay were both carried out in the same month, August 1789 (more than a year after Bradley’s first excursion to Pittwater), by the same people, Captain Hunter and Lt Bradley. It seems highly unlikely that they would have used differing scales on the two maps.

We suggest it would have been self-evident to Naval people at the time that ‘mile’ measurements on navigation charts meant nautical miles and not land miles. So despite the anomaly in labelling, it seems logical to assume that the scales on both charts refer to ‘Nautic’ or nautical miles, and that Bradley’s journal entries similarly refer to nautical miles.

We also tried another tack and asked the Mitchell Library staff if Bradley recorded the latitude and longitude for his noon reading on 6 March 1788. But he did not do this during the party’s travels around Broken Bay, presumably because the weather conditions would have made such observations impossible.

Bradley’s sketch and the time spent at Clareville/Taylors Point

Phillip’s party must have spent some time at Clareville/Taylors Point for Bradley to have been able to draw at least the basic details of his sketch, take a break on land and make his other observations, yet (as mentioned earlier) Bradley made no other entries in his journal to describe the details shown in the sketch. It also seems likely that Clareville/Taylors Point would have provided a convenient sheltered location to drop anchor around noon and break the day’s excursions around Pittwater, given the bad weather.

We estimate that it would have taken Bradley at least 20 to 30 minutes to do even his basic sketch, based on Roger’s rough on-site sketch shown below. Bradley customarily finished his sketches later, filling in parts from memory.

This exercise also revealed that Bradley would have needed to use some artistic licence to highlight the key features that he wanted to record (or perhaps that Phillip asked him to record) for Naval and food-growing purposes.

For example, Bradley highlighted the folds in the hills to show bays and coves; he exaggerated the reefs at the points on the western foreshore, as well as the height of the land when seen from his vantage point; and he drew attention to the flat land around Sandy Point by drawing a number of thinned out individual palm trees (some planted cabbage tree palms are there today) to distinguish it from the more thickly vegetated hills.

Bradley’s illustration was not meant to be a work of art but was essentially a working guide to what others could expect to find in Pittwater. Drawing was part of a naval officer’s training at a time before the invention of photography.

Even a photograph of this scene, especially one taken on an overcast day, may not show the aspects a Naval officer exploring new areas would have wanted to note. Compare the details in the two sketches with the lack of clarity of some features in the photograph below (Figure 10).

Figure 10: The scene today taken from the vantage point from which Bradley and Roger drew their sketches. Note that the photograph does not clearly show the land features deliberately highlighted in both sketches.

Bradley’s observations of oyster shells and cycads

Bradley’s journal description of oysters on the rocks and cycads could have applied equally to Careel Bay and Taylors Point. The photographs below (Figures 11 and 12) were taken near Bradley’s sketch site.

...several Women in Canoes were fishing two of them came ashore the one an Old & Ugly, the other a young Woman tall & was the handsomest Woman I have seen amongst them, she was very big with Child, her fingers were complete as were those of the Old Woman. One of the Women made a fishing hook while we were by her, from the inside of what is commonly called the pearl oyster shell, by rubbing it down on the rocks until thin enough & then cut it circular with another, shape the hook with a sharp point rather bent in & not bearded or barbed...

... in this Cove we met with a kernel which they prepare & give their Children, I have seen them eat it themselves, they are a kind of Nut growing in bunches somewhat like a pine top & are poisonous without being properly prepared the method of doing which we did not learn from them.

Figure 12: Cycads growing in the bush today, next to a grey spotted gum, below Bradley’s sketch site.

* * *

Figure 14: Chart of Botany Bay from Lt W Bradley’s journal, A Voyage to New South Wales 1786-1792, labelled with a ‘Scale of Nautic Miles’. Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

Figure 15: Chart of Broken Bay from Lt W Bradley’s journal A Voyage to New South Wales 1786 -1792, labelled with a ‘Scale of Miles’. Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. This is the first known map of Pittwater (1789).

When measured using the scale shown on this chart, the distance from West Head Beach at the entrance to ‘PittWater’ to Taylors Point is approximately 3 ‘Miles’. The distance between the same points as measured on maps today is approximately 5.8 kilometres, which closely corresponds to 3 nautical miles (5.6 kilometres).

References

i. Geoff is President of the Avalon Beach Historical Society; Roger is a member of the Avalon Beach Historical Society.ii. Bradley, W. A voyage to New South Wales, 1786-1792. Bradleys Head in Sydney Harbour is named after him.

iii. Sayers R and Searl G. Governor Phillip’s first landing site, campsite and contact with local aborigines in Pittwater 5 March 1788: The case for West Head Beach. Pittwater Online News, December 18, 2016 - January 7, 2017: Issue 294. Retrieved from http://www.pittwateronlinenews.com/Governor-Phillip-at-West-Head-R-Sayers-G-Searl.php

iv. William Bradley - Journal. Titled `A Voyage to New South Wales', December 1786-May 1792; compiled 1802+, State Library of New South Wales digital version. Collection 02: Page 91. . Retrieved from http://digital.sl.nsw.gov.au/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=FL1614777&embedded=true&toolbar=false A State Library of NSW published version of the journal in A voyage to New South Wales : the journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786-1792 (also available in the Australian Reference area of Special Collections in the Mitchell Library, call number: 981/54A4) and viewed the notes section but was unable to locate any reference to the specific identification of measurements.

v. That was back in January 2017. It’s taken us this long (to July 2017) because we’re both retired and very busy having fun, people.

vi. Shelagh and George Champion. Manly, Warringah and Pittwater: First Fleet Records of Events, 1788-1790. No.3: Journey to Broken Bay by Water 2nd to 9th March, 1788. 1990. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/Roger/Downloads/Journey%20to%20Broken%20Bay%20by%20Water[2]%20(3).pdf

vii. Data provided by the National Tidal Unit of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology shows that the tide on 6 March 1788 would have been rising from just before 1am until around 7am:

Thursday AM 6 March 1788 - Low Tide 0052 0.53m

- High Tide 0713 1.66m

Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology National Tidal Unit ‘hind-cast of the tides for Fort Denison, using the basis of the 2017 tide predictions. The times should be a reasonable approximation, but the heights do not include any allowance for sea level rise since 1788.’ Authors’ note: There is no significant difference between tidal times at Pittwater and Sydney Harbour; both are open to the sea at their entrances.

viii. According to historical weather-focused research the weather was very stormy and wet in the early months of 1788, so the catchment at Mackerel Beach was probably full and its freshwater stream would have run across the beach. ‘The weather during the latter end of January and the month of February [1788] was very cold, with rain, at times very heavy, and attended with much thunder and lightening...’, David Collins, quoted in Joëlle Gergis and David J. Karoly, School of Earth Sciences, University of Melbourne, Australia, and Rob J. Allan, Met Office, Hadley Centre, Exeter, United Kingdom (page 93). A climate reconstruction of Sydney Cove, New South Wales, using weather journal and documentary data, 1788–1791. Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Journal 58 (2009) 83-98. Retrieved from http://climatehistory.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Gergis_Sydney-Cove_AMOJ.pdf

ix. This is doubtless a reference to cycads, which are found in bushland around Pittwater.

Stony Range Regional Botanic Garden’s Bush Tucker Walk leaflet notes that the seeds of Cycads (Macrozamia communis), or Burrawangs, are nutritious but ‘... highly poisonous unless properly treated with roasting, pounding & washing. Soft brown hairs were used as stuffing. Trunk and tubers are rich in starch.’

x.1 Admiralty Mile = 1.853 kilometres (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nautical_mile). So Bradley’s 3 [nautical] Miles is equivalent to 5.559 kilometres, or approximately 5.6 kilometres.

A State Library of NSW Librarian with specialised maps and charting expertise suggested that it may be possible to use the “Table of Latitudes & Longitudes of Places as Determined of Observations on Board…” (commencing on page 308 of the published version of the journal) in conjunction with journal entries to conduct research to determine the exact measurements used by Bradley.

xi. Source: Google maps initially. Confirmed by satellite track of authors’ journey from West Head Beach to Stokes Point = 3.5 kilometres.

xii. Paradise Beach is close to 4.8 kilometres (=3 land miles) from West Head Beach, but it doesn’t tally with a number of important factors. Most tellingly, if Bradley meant 3 land miles rather than 3 nautical miles, the distance from West Head Beach to Paradise Beach as measured by the scale on the Broken Bay chart shown in Figure 15 and discussed in the accompanying text should correspond to ‘3 Miles’. But it doesn’t, because, as we later establish, this scale in fact measures nautical miles (= 5.6 kilometres).

xiii. Shelagh and George Champion. Manly, Warringah and Pittwater: First Fleet Records of Events, 1788-1790. No.3: Journey to Broken Bay by Water 2nd to 9th March, 1788. 1990.

xiv. http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/cove

xv. If they had stopped and landed nearer to Taylors Point itself, it seems more logical Bradley would have said they stopped ‘in the shelter of a point of land’ rather than a cove.

xvi. Phillip, A. The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay. First pub. 1789.

xvii. Shelagh and George Champion. Manly, Warringah and Pittwater: First Fleet Records of Events, 1788-1790. No 11: Survey of Broken Bay: 27th August to 8th September 1789. 1990.