Retracing Governor Phillip's Footsteps Around Pittwater:

The Mystery Of The Cove On The East Side

Roger Sayers And Geoff Searl

This coming week marks the 230th anniversary of Governor Phillip sailing past Avalon and Palm Beach on 2 March 1788 and entering Pittwater for the first time on 5 March 1788.

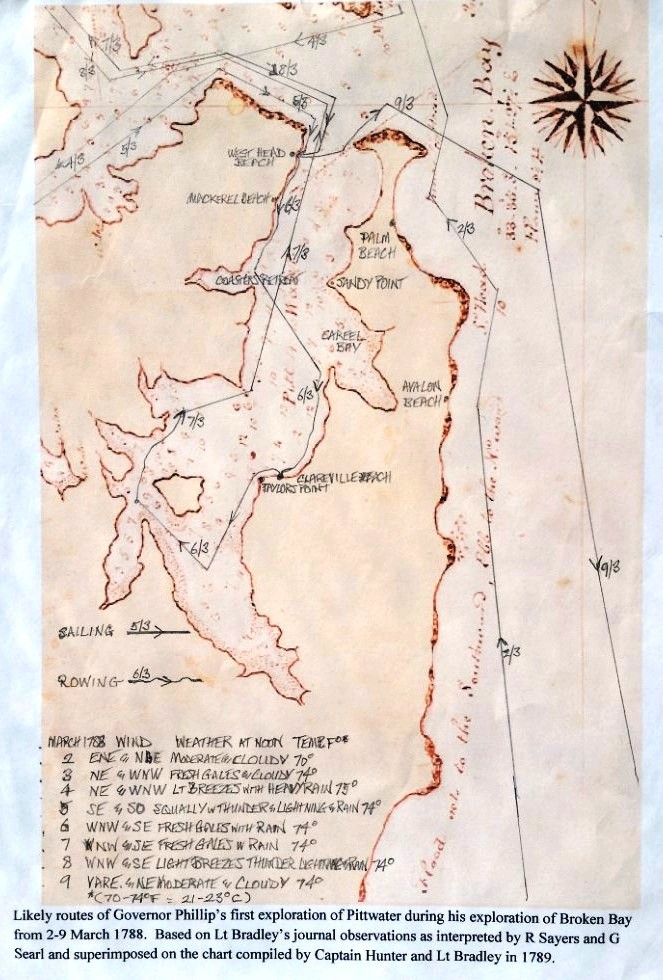

Below is a revised version of the earlier story in Pittwateronlinenews ..this time with a map showing Geoff Searl and Roger Sayers assessment of his most likely routes in out and around Pittwater on 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 March 1788.

When you're out and about on Pittwater this week - have a look around and think about what occurred here 230 years ago this week!

Thank you gentlemen.

Retracing Governor Phillip's Footsteps around Pittwater: The Mystery of the Cove on the East Side

by Roger Sayers and Geoff Searli

Just five weeks after landing at Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788, Governor Phillip, accompanied by Lieutenant William Bradley and a small party of sailors and marines in two boats, made the first European exploration of Pittwater while exploring Broken Bay. They were searching for land suitable for agriculture, as establishing a food source was essential for the new colony’s survival.

Bradley kept a detailed journal of his experiences as a member of the First Fleet, providing an invaluable record of the colony’s early years. This article focuses on an intriguing entry he made during this excursion which took place from 2 to 9 March 1788. (Extracts from Bradley’s journal are shown in italics throughout this article.)

On 6 March he noted:

We stop'd in a Cove on the E.t. side about 3 Miles up... iii

There is no obvious inlet in Pittwater that matches this description, and to date the location of this cove – the second place Governor Phillip came ashore in Pittwater and met with local Aborigines – has not been identified.

We set out to find this cove, guided by Bradley’s journal and weather observations (particularly his records of the prevailing winds), and the 1990 work of Shelagh and George Champion. iv We are grateful for the assistance of the Mitchell Library and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

On 5 March 1788 they camped overnight in a cove just within the entrance (of Pittwater) which we believe to be West Head Beach where an aboriginal old man and boy had guided them through the rocks.

The next day’s entry reads:

[Thursday. 6.] A.M. Went up this Arm [the South Arm of Broken Bay, ie Pittwater] saw several of the Natives in every Cove, the Old Man & boy followed us round to one of the Coves & shew’d us Water...

Weather conditions throughout Phillip’s first journey to Broken Bay and Pittwater were challenging, with constant rain and wind changes. Their exploration of Pittwater on 6 March 1788 probably started around 7am at high tide vi so that the boats could navigate the rocks off West Head Beach.

Bradley noted that the wind was initially from WNW. As this would have meant they were in a wind shadow beneath the steep hills, they doubtless rowed to nearby coves along the western shoreline, toward Coasters Retreat.

Figure 1: Western shore of Pittwater from just off West Head Beach, looking south

The fresh water they were shown by the old man and boy was possibly the freshwater stream at Mackerel Beach, which runs across the beach when the catchment is full after rain. The weather was very stormy and wet in the early months of 1788. vii

Figure 2: Mackerel Beach, looking much as it would have in 1788. The freshwater stream running across the beach is visible from a boat offshore.

Bradley’s next journal entry reads:

We stop'd in a Cove on the E.t. side about 3 Miles up ...

The steep, rocky land on the western shore was clearly not suitable for agriculture. Directly east of Coasters Retreat (the last cove on the western shore), on the opposite side of Pittwater, lies Sandy Point where there is an area of flat land, and Careel Bay a possible candidate for Bradley’s cove.

But Careel Bay is only 2.5 to 3.5 kilometres from Pittwater’s entrance, which doesn’t correspond to Bradley’s 3 miles - whether he was using either nautical miles (5.6 kilometres)viii as we suspected, or land miles (4.8 kilometres).

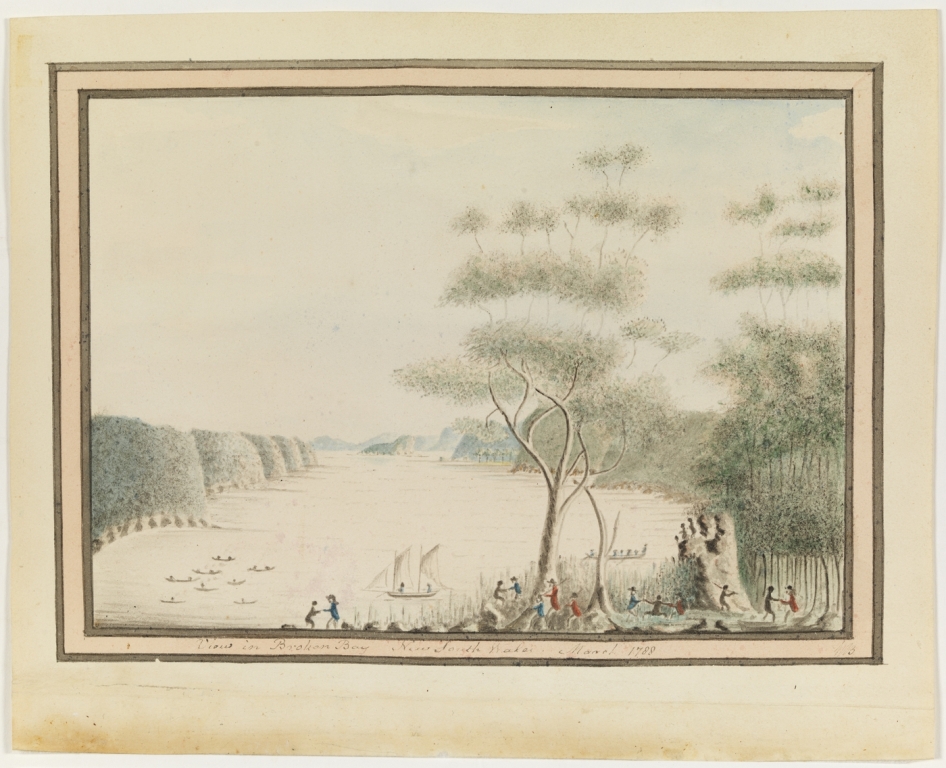

Nor is there any obvious inlet southward of Careel Bay. The eastern shoreline is a continuous stretch of rocky foreshore and beaches to the next prominent feature, Taylors Point. True, Bradley had apparently drawn his iconic scene of Pittwater ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales. March 1788' from the vicinity of Taylors Point, but there is no obvious cove nearby. It was a mystery.

Bradley recorded the following weather observations, at noon:

6th 74 degrees, wind WNW & SE, Fresh Gales with Rain

In order to leave Coasters Retreat and head across Pittwater, they would have stopped rowing and hauled up their sails, taking advantage of the WNW wind. On clearing the headland, they would have seen coming toward them, or felt, the gale force SE wind and tacked toward a stretch of land to their SE for shelter, away from the rocky western shore.

Figure 3: Looking east from Coasters Retreat toward the entrance of Careel Bay (centre) and an area of flat land on Sandy Point (left).

The Champions didn’t suggest where Phillip’s party may have stopped, but noted: ‘They spent 6th March exploring Pittwater, and it was apparently on this day that Bradley illustrated the scene, looking northwards towards Lion Island.’ ix

Figure 5: ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales. March 1788'. Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. IE number: IE1113857. This is the earliest European depiction of Pittwater.

Bradley:

… several Women in Canoes were fishing two of them came ashore the one an Old & Ugly, the other a young Woman tall & was the handsomest Woman I have seen amongst them, she was very big with Child, her fingers were complete as were those of the Old Woman.

... One of the Women made a fishing hook while we were by her, from the inside of what is commonly called the pearl oyster shell, by rubbing it down on the rocks until thin enough & then cut it circular with another, shape the hook with a sharp point rather bent in & not bearded or barbed, …

... in this Cove we met with a kernel which they prepare & give their Children, I have seen them eat it themselves, they are a kind of Nut growing in bunches somewhat like a pine top & are poisonous without being properly prepared the method of doing which we did not learn from them [cycads] x.

Bradley’s sketch doesn’t depict the observations above, but instead shows the Europeans and natives holding hands or even dancing. Neither does his journal describe the human event shown in his sketch. The sketch does shows several native canoes offshore from where Phillip’s party are stop'd ... on the E.t. side of Pittwater. Comparing Bradley’s sketch with our own observations, we believe it was most likely drawn from a location above the southern end of Clareville Beach.

Figure 6: The view from a boat stopped just off Clareville Beach. We believe Governor Phillip’s most likely landing place was along this stretch of sand. Bradley’s sketch was drawn from a vantage point above the beach, near the centre of the photograph.

Oysters on the rocks and cycads growing today beneath the likely location of Bradley’s sketch site, further suggest that the scene he depicted was drawn near the cove we were searching for.

Figure 7: Oysters on the rocks today below Bradley’s sketch site.

Figure 8: Cycads growing in the bush today, next to a grey spotted gum, below Bradley’s sketch site.

The distance we travelled from West Head Beach to just off Clareville Beach was 5.55 kilometres, or 3 nautical miles. As Bradley was a Naval officer, we assumed he meant 3 nautical or Admiralty miles (5.6 kilometres).

On consulting the Mitchell Library, we were advised that Bradley’s journal contains no references to measurements used. While some of the charts in his journal, including one of Botany Bay are labelled ‘Scale of Nautic Miles’, others, including one of Broken Bay (the first map of Pittwater), are labelled ‘Scale of Miles’.

However, using the Miles scale on the Broken Bay chart, we found that the distance from West Head Beach to Taylors Point almost exactly corresponds to 3 ‘Nautic Miles’.

The surveys for the Botany Bay and Broken Bay charts were both carried out in August, September 1789 by the same people, Captain Hunter and Lieutenant Bradley xi. It seems highly unlikely that they would have used different scales for the two charts. The conclusion is therefore that Bradley’s Broken Bay measurements refer to nautical miles (not ‘Miles’ as on the chart scale).

If, then, the sketch was drawn where they stopped in a cove 3 nautical miles up from the entrance to Pittwater, on the east side, where is this cove?

The answer lies partly in different understandings of what constitutes a cove.

We had in mind that Bradley meant an inlet. The Concise Macquarie Dictionary of Australian English defines cove as ‘a small indentation or recess in the shoreline of a sea, lake, or river’. But according to the Cambridge Dictionary, cove in British English means ‘a curved part of the coast that partly surrounds an area of water’. xii

The beach at Clareville curves gently toward Taylors Point and forms a cove in the British sense of the word when approached from the north along the eastern shoreline, as we believe Phillip and Bradley would most likely have done.

Figure 9: Approached from the north, Clareville Beach shows a distinct curve, matching the definition of a ‘cove’ in the British English sense. Bradley’s sketch was drawn from a vantage point above the beach, near the centre left of this photograph.

It was clear to us from our on-site observations that Bradley in his sketch used some artistic licence to show the key natural features that he wanted to record, such as emphasising folds in the hills to show bays and coves and exaggerating the reefs at the headlands on the western foreshore, the height of the hills, and the flat land at Sandy Point.

Figure 10: The scene today taken from the vantage point from which Bradley drew his sketch. Note that the photograph does not clearly show the land features that he deliberately highlighted in the sketch.

There is nothing in Bradley’s journal that explains the human aspect in the scene he sketched,¬ even though it suggests a noteworthy event, depicting as it does Aborigines and Europeans holding hands or even dancing together. Our conclusion is that Bradley also used artistic licence in order to depict the friendly nature of the encounter with the local Aborigines described in his journal.

Our conclusions:

- Bradley’s Cove on the E.t. side is Clareville’s sandy beach.

- Bradley sketched his ‘March 1788 view in Broken Bay’ from a vantage point above the rocks at the southern end of Clareville Beach on 6 March 1788, confirming the Champions’ thoughts on the date. Bradley clearly used artistic licence to depict aspects that he wished to feature for navigating and other purposes.

- Bradley’s journal estimate of 3 Miles up (Pittwater) refers to nautical miles.

- Distances on a 1789 chart of Broken Bay by Captain Hunter and Lieutenant Bradley correspond to nautical miles, despite the chart bearing a ‘Scale of Miles’.