February 12 - 18 2023: Issue 571

Ringtail Posse: 1 – February 2023

Anna Maria Monticelli: King Parrots/Water Dragons - Jacqui Scruby: Loggerhead Turtle - Lyn Millett OAM: Flying-Foxes - Kevin Murray: Our Backyard Frogs - Miranda Korzy: Brushtail Possums

Definition from

Ringtail: from the 'Common Ringtail Possum' which is not so common anymore in urban areas. The Common Ringtail Possum is found along the entire eastern part of Australia and south west Western Australia. They are also found throughout Tasmania. The western ringtail possum is a threatened species under State and Commonwealth legislation. In Western Australia the species is listed as Critically Endangered fauna under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.+

Posse: noun. 1 : a large group often with a common interest 2 : a body of persons summoned by a sheriff to assist in preserving the public peace usually in an emergency 3 : a group of people temporarily organised to make a search (as for a lost child) 4 : one's attendants or associates.

In recent approved DA’s Council is listing as a requirement of consent in Assessment reports to look after the other residents of this area, the wildlife. On blocks where people wish to remove large amounts of trees that are clearly homes for local fauna a wildlife expert must assess these prior to any removal taking place, nesting boxes are required to be installed afterward and Ecologists must be on site during their removal. Other recent examples and instances are:

Bandicoot/Penguin (Avalon)

Long-nosed Bandicoots & Little Penguins – Best Practices for Residents

Residents are encouraged to follow a number of Best Practices to assist with the protection and management of the endangered populations of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins:

Long-nosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other native animals should never be fed as it may cause them nutritional problems, hardship if supplementary feeding is stopped, and it may increase predation.

Feral cats or foxes should never be fed or food left out where they can access it, such as rubbish bins without lids or pet food bowls, as these animals present a significant threat to Longnosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other wildlife.

The use of insecticides, fertilisers, poisons and/or baits should be avoided on the property.

Garden insects will be kept in low numbers if Long-nosed Bandicoots are present.

When the North Head Long-nosed Bandicoot Recovery Plan is released it should be implemented where relevant.

Dead Long-nosed Bandicoots or Little Penguins should be reported by phoning Manly Council on 9976 1500 or Department of Environment and Conservation on 9960 6266.

Please drive carefully as vehicle related injuries and deaths of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins have occurred in the area. Care should also be taken at night in the drive way when moving cars as bandicoots will seek shelter beneath vehicles.

Cat/s and or dog/s that currently live on the property should be kept indoors at night to avoid disturbance/death of native animals. Ideally, when the current cat/s and/or dog/s that live on the property no longer reside on the property it is recommended that they not be replaced by new dogs or cats.

Report all sightings of feral rabbits, feral or stray cats and/or foxes to N B Council.

And;

Dead or Injured Wildlife (Palm Beach)

If construction activity associated with this development results in injury or death of a native mammal, bird, reptile or amphibian, a registered wildlife rescue and rehabilitation organisation must be contacted for advice.Protection of Habitat Features

All natural landscape features, including any rock outcrops, native vegetation and/or watercourses, are to remain undisturbed during the construction works, except where affected by necessary works detailed on approved plans.

Reason: To protect wildlife habitat.

The Reason given in all instances is: To protect native wildlife.

This follows on from the 2022 Local Government NSW Conference where a Motion was passed - That Local Government NSW lobby the NSW Government to:

- In conjunction with industry associations, introduce enforceable standards for the preparation of flora and fauna management plans.

- Consider Codes of Practice and Guidelines for handling native wildlife and other best practice and animal welfare laws in development of the standards.

- Consult with Councils, National Parks and Wildlife Service, Ecological Consultants Association of NSW, wildlife rescue organisations and other relevant agencies in the preparation of standards.

Such a standard should include requirements for:

- Pre-clearance surveys to be carried out to establish which species are present on the site, including identification of any threatened and native species.

- The identification of suitable nearby areas where wildlife could possibly be relocated.

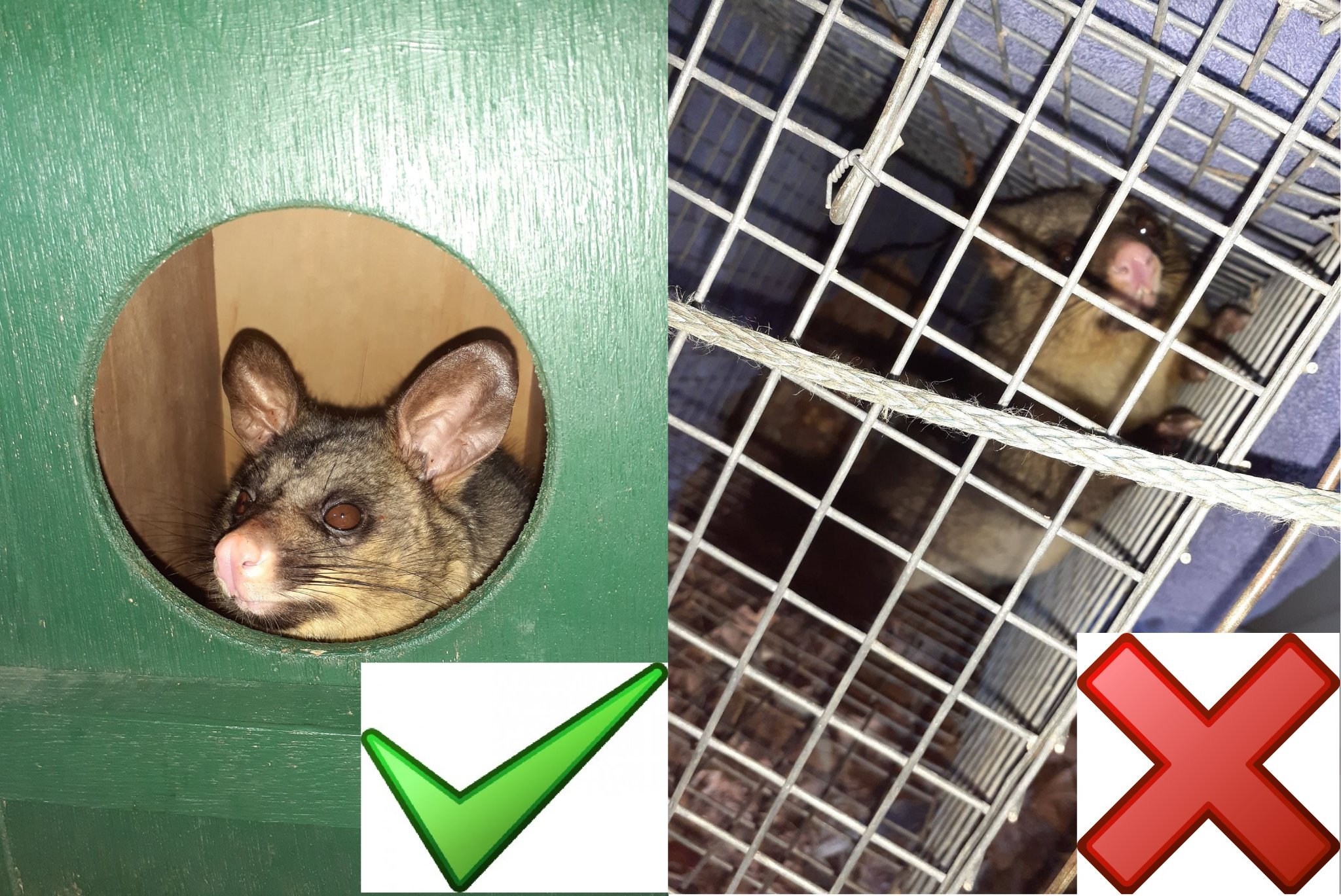

- The provision of possum, glider and bat boxes sufficiently in advance of vegetation clearing to allow wildlife time to discover the boxes and become familiar with them.

- Compliance with the NSW Code of Practice for Injured, Sick and Orphaned Protected Fauna and the licencing requirements contained in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

- Best practice for wildlife handling and care (including contact with local wildlife rescue groups).

- Reporting of injured or killed fauna to the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment to enable the data to be used in statewide biodiversity monitoring programs.

The premise of this is that mandatory pre-clearance surveys to establish what wildlife lives there before works commence, and to document this in a formal way, should be required on any site that has vegetation and for which a DA has been approved. The experience is that often vegetation is removed before an application is submitted, often leaving wildlife with no home. Wildlife then ends up on roads dead or dies after being displaced/evicted.

One wildlife carer cited a recent Pittwater case of a powerful owl pair site that had had vegetation removed to make the development more likely to proceed – the nest and two babies were destroyed.

‘It’s hard to prove wildlife is/was present after the clearing as they aren’t there.’

‘Once trees and vegetation are removed the problem is where do these animals go?’

Powerful Owls are also not so common anymore in urban areas.

However it's clear human residents of this LGA have a deep and abiding love for and connection to these other furry, scaled, finned and feathered beings. We listen for them during the night, happy when we hear their footsteps scampering across our rooves or their soft hoots across the valleys.

Human residents are distressed when they find injured wildlife or witness wildlife being attacked.

Data kept by the NSW Environment Department, although only listing incidents from June 2013 to June 30 2020, shows that 28,542 wildlife animals have been rescued in our area between June 2013 and June 30 2020. That's well over 4000 each year. Of these 41 were threatened species (504 threatened animals rescued - only 111 threatened animals released).

''This study draws on 469,553 rescues reported over six years by wildlife rehabilitators for 688 species of bird, reptile, and mammal from New South Wales, Australia.... Of the 364,461 rescues for which the fate of an animal was known, 92% fell within two categories: ‘dead’, ‘died or euthanised’ (54.8% of rescues with known fate) and animals that recovered and were subsequently released (37.1% of rescues with known fate).''In total, there were 872,087 records reported during the six-year (2013–14 to 2018–19) study period. Just over 97% of these came from three animal groups–birds, mammals, and reptiles. Of the total number of records, 402,534, (46%) were excluded from the descriptive analysis because they: a) did not contain any information about the animal, or the animal’s identification was ambiguous and could not be placed within a group (e.g. an ‘unidentified animal’); b) contained only sightings of animals and were not attended to in some way by a wildlife rehabilitator; c) were records of amphibians (373 records) or non-vertebrate fauna (e.g. spiders, insects, etc.); d) were non-avian marine vertebrates such as whales, seals, sharks, rays, fish etc; e) were reported as floating, drowned, or washed up animals (deemed an ambiguous cause for rescue, n = 48); f) contained both an ‘unknown’ cause for rescue and an ‘unknown’ fate; or f) were an introduced or spurious species (e.g. extinct, or out of known range). These exclusions resulted in a dataset for descriptive analysis of 469,553 records i.e. 54% of the initially reported amount.''

Data to 30 June 2021 lists of the 5, 235 animals rescued during that 2020 to 2021 period just 1,573 were released.

Many people state we are the generation witnessing the extinction of urban wildlife. There has been generation after generation of humans living alongside and with wildlife, until this one.

It's not just the Pittwater koalas that have gone, other species, like the ringtail possum or long-nosed bandicoot are disappearing, along with their joyful snuffles and squeaks, from our urban backyards and the trees that tower over them.

There is a growing silence at night for those species that forage for food then - possums, wallabies, owls. The same is occurring for those that are active during daylight.

Although many point to the impacts of cat and dog attacks due to irresponsible owner, there is also what is termed the 'inconvenient possum' in a roof or garden shed, because its home tree has been cut down. These are caught by those hired, some of whom have little knowledge or scruples, and release them into areas out of their home range - a death sentence for that possum as this species is territorial, along with requiring certain food trees in order to eat, to survive.

There is predation by other introduced species - readers regularly send in photos and videos of foxes roaming and killing at night.

There are roadkill black spots, places where wallabies or turtles or possums used to cross the area where a road has been cut through and a speed limit that means death for wildlife. There are no 'speed humps' in place, and no plan at a local, state or federal government level to istall these. Residents and wildlife rescuers have reported some drivers 'aiming straight for' a stricken animal.

There is the razing of blocks of land for development prior to any required assessment of the environment taking place to circumvent those requirements so a report can state 'nothing present'. There is nothing present because its habitat has been cleared or the wildlife killed by these actions.

Our local wildlife carers are getting exhuasted, state there have been so many, too many so far this summer - they are increasingly heartbroken with all the babies they lose, they cry every day, and then pick themselves up and get on with trying to save the next critter, and the next.

Wildlife carers are all volunteers - they do the rescues, sometimes horrific rescues, run to and fro from the great local vets who help out trying to save them, they gather or pay for the food, for the milk, for the petrol, for the electricty to keep bubs warm. There are no grants or funding for Australia's wildlife carers - they have to raise funds through running events, raising awareness, collecting cans for a 10 cent return.

Similarly we are not in denial that all our local wildlife feels and thinks - they cry when their babies are killed in front of them, mourn the loss of a mate - people who have heard this or seen this never forget.

This year a celebration of residents' favourite wildlife will run as Profiles across 2023 - simply to allow those who love their chosen 'critter' to speak for them a little, to remind us of what is here and what we feel connected to has feelings too.

Information about these species and how many or why we are losing them will also be included - just so we can think about how we, as individuals and as one community, can turn around that growing silence and emptiness closing in around us and these other ones we love.

Ultimately the founders of the Ringtail Posse are hoping everyone here chooses to become a Member of the Ringtail Posse and keep their other loved one ever present in their heart.

Reason?: To Protect Local Wildlife so it becomes 'common' and safer for our wildlife to be everywhere once more.

To join in please email us with 'Ringtail Posse' in the subject line - with so many local species of wildlife, vital insects and seals flopping around on the sand, there are several on the lists that haven't been claimed for guardianship yet - what's yours?

Round 1 of Ringtail Posse Profiles includes the following now officially joined Members:

Anna Maria Monticelli

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

I love every single moving creature that visits my garden – but of course I have regulars who can’t resist my Italian hospitality and I spoil them rotten. In my garden, I have hidden ponds with fresh water and plants and logs for them to hide in - so my visitors feel safe when they need a bath or drink. I would betray them if I had to choose only one, a favourite – as my backyard kingdom occupies many superstars.

Around 5pm every day the bar opens inside the house and the food kitchen for the birds and water dragons shifts al fresco.

Some years ago, while filming in Africa, my daughter’s beloved pet dog Joan Sutherland died. Since then, we’ve had to keep up the opera theme with pets such as Bella who is an opera aficionada.

So, the enduring pair of King Parrots: Mimi the female and Marcello the male, wait patiently for the right treat and won’t budge until they get what they came for. Marcello is pushy – if I put seeds on the bird dish, he won’t let Mimi eat - so Mimi flies over to me and rests on my shoulder or arm for protection – Marcello becomes jealous and comes over too. I have to hand-feed each one individually so that they don’t brawl.

Around the same time Despina, the Female Water Dragon, comes for her strawberries or banana treat. This summer she arrived with little Miss Elektra, way too shy to know her character, yet .

Despina follows my voice and comes looking for me – even enters the house if the door is open. I love watching the way her eyes rotate almost robotically and is cautious, always cautious – unlike her lover Don Giovanni who is robust and greedy and eats up all the rations.

The only brave souls at the 5pm menagerie banquet to challenge Don Giovanni are the Rainbow Lorikeets who have extraordinary instincts and know when everyone else has arrived. Wow, do they take over – hop hop waving their swords and, in a minute, the stage is theirs.

La Fille du Regiment is the first one to arrive, who checks out the battlefield and then is joined by the regiment to start the war: Hop-hopping towards Despina and even challenging Don Giovanni to retreat – once the floor is theirs they clean up any morsels deserted by Mimi or Marcello.

Despina the water dragon - Mimi

So many of my visiting birds sing, fill the air with music – gangs of Kookaburras at dawn and dusk send messages across the trees - to other gangs who return the laughter – I wonder what’s so funny or are they cries of territorial warnings.

A pair of Rosellas chirp gently by the front door swinging on a stray wisteria branch calling me – I hand them a walnut each and off they go.

This spring a Willie Wagtail made a nest below my gutters hidden by the bougainvillea – and two baby birds hatched in remarkably short time. I left the nest for future visitors.

A Sulphur Crested Cockatoo comes by to check and see how the tomatoes are going – looking for an entry to the netting maze I made. An old soul, he knows that I know his shrewd plan and he watches me convinced he will outfox me.

The solitary Magpie sings a sweet tune and waits for his treat too.

The daily joy these animals bring! Why wouldn’t I fight for their survival?

After their visit they all fly across the road where they safely live in a beautiful wild reserve. And they can rest assured that, if anyone ever dares cut a tree or destroy their habitat, they will have to deal with Lady Macbeth.

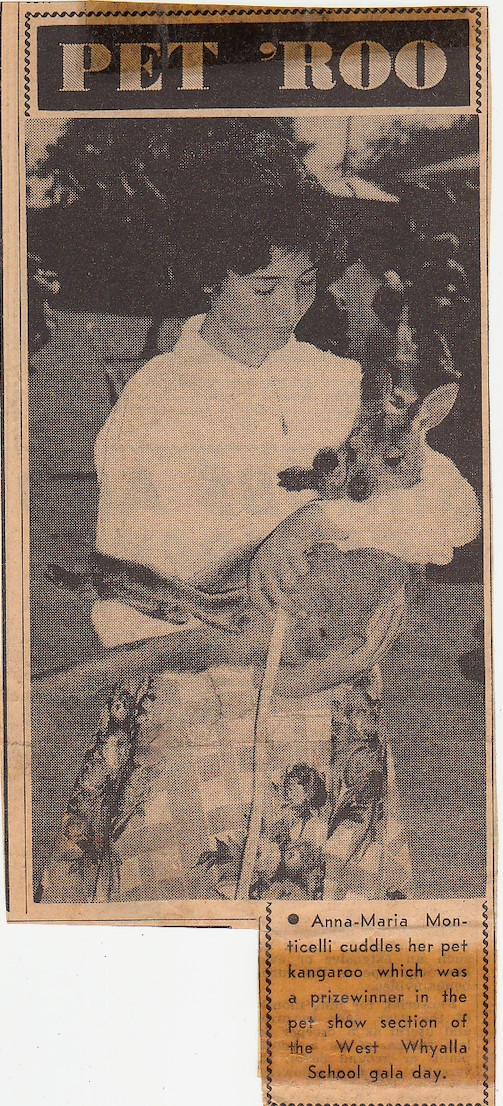

With my kangaroo - I nursed this delightful bub after her mother was killed. I was 12

.jpg?timestamp=1676227209958)

Anna Maria Monticelli

Australian king parrot (Alisterus scapularis), male. Photo: A J Guesdon

King Parrot Information

There have been 80 King Parrots rescued during the June 2013 to June 2021 data collated in this LGA - 16 were released. Collison with motor vehicles, or collision with 'other', usually indicating a bird has flown into a glass window (you can put stickers or markers on these to prevent this) also accounts for a high incidence of rescued kingies.

There have been 390 Water Dragons rescued locally during the reported period, 134 were released. Being attacked by dogs accounts, by far, for the highest 'common reason for rescue'. Unfortunately a dog will grab a water dragon around the neck and shake it from side to side violently, so even if they do not die from the bites and subsequent infections, their small bones have been fractured or dislocated beyond healing. The highest count for this locally occurred during the 2019 to 2021 timeframe - during the Covid lockdowns. In comparison, just two were lost due to car strikes.

Physignathus lesueurii lesueurii, the Eastern Water Dragon. Photographed in Careel Creek 31.10.2013. Picture by A J Guesdon.

Jacqui Scruby, Independent Candidate For Pittwater In 2023 State Election

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

This is a very hard question - I love the creatures you just don't expect to see from our local seals to late night owls and the odd early morning wallaby and I also love that on the peninsula our schools have cockatoos instead of pigeons! But I actually think the loggerhead turtle is my answer.

Why do you like the loggerhead turtle?

We have a little turtle who lives in Dolphin Bay and brought much joy to my family during COVID lockdowns. Its occasional appearance sparks absolute joy and a bit like chasing the end of a rainbow, he always remains elusive. I've been a big advocate for fighting ocean plastics and this little turtle reminds me why addressing our plastic waste crisis is critical - something I've done on an individual and business level and am ready to take on at a state level.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

First spotted during COVID when the world slowed down (and so did I) - a lovely reminder that in many ways we need to slow down to see what's hidden in plain sight and be stewards for nature as we design our communities.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

I've only ever seen one turtle at a time so that says it all.

Independent Canidate for Pittwater, Jacqui Scruby

Loggerhead Turtle Information

The main causes of loggerhead deaths locally is drowning in shark nets, although recent data shows most are found before they drown and released. Fortunately the shark meshing period coincides with surf lifesavers being on the beach or on the water and effecting rescues and detanglings before they drown or a hit by passing boats while unable to get away.

Locally loggerheads have been found deceased within the Pittwater estuary with fishing line entanglements, along with signs of boat strikes. During last years' storms, run off out of the Hawkesbury River was attributed as a causing deaths factor in large Loggerheads being found deceased on Central Coast beaches, along with nets off the coast.

Digesting plastic fishing line and other plastics, which look like their chosen diet underwater, has also contributed to local mortalities.

The loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) is a species of oceanic turtle distributed throughout the world. It is a marine reptile, belonging to the family Cheloniidae. The average loggerhead measures around 90 cm (35 in) in carapace length when fully grown. The adult loggerhead sea turtle weighs approximately 135 kg (298 lb), with the largest specimens weighing in at more than 450 kg (1,000 lb). The skin ranges from yellow to brown in color, and the shell is typically reddish brown. No external differences in sex are seen until the turtle becomes an adult, the most obvious difference being the adult males have thicker tails and shorter plastrons (lower shells) than the females.

The loggerhead sea turtle is found in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, as well as the Mediterranean Sea. It spends most of its life in saltwater and estuarine habitats, with females briefly coming ashore to lay eggs. The loggerhead sea turtle has a low reproductive rate; females lay an average of four egg clutches and then become quiescent, producing no eggs for two to three years. The loggerhead reaches sexual maturity within 17–33 years and has a lifespan of 47–67 years.

The loggerhead sea turtle is omnivorous, feeding mainly on bottom-dwelling invertebrates. Its large and powerful jaws serve as an effective tool for dismantling its prey. Young loggerheads are exploited by numerous predators; the eggs are especially vulnerable to terrestrial organisms. Once the turtles reach adulthood, their formidable size limits predation to large marine animals, such as large sharks.

The loggerhead sea turtle is considered a vulnerable species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. In total, 9 distinct population segments are under the protection of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, with 4 population segments classified as "threatened" and 5 classified as "endangered" Commercial international trade of loggerheads or derived products is prohibited by CITES Appendix I.

Untended fishing gear is responsible for many loggerhead deaths. Mortaility also occurs due to the swallowing of marine debris such as plastic bags or balloons let loose with trailing strings, also plastic.

The greatest threat is loss of nesting habitat due to coastal development, predation of nests, the introduced red fox is a predator of loggerhead nests in Australia. Human disturbances (such as coastal lighting and housing developments) that cause disorientations during the emergence of hatchlings also causes deaths.

Turtles also suffocate if they are trapped in fishing trawls. Turtle excluder devices have been implemented in Australia in an effort to reduce mortality by providing an escape route for the turtles.

Loss of suitable nesting beaches and the introduction of exotic predators have also taken a toll on loggerhead populations. Efforts to restore their numbers will require international cooperation, since the turtles roam vast areas of ocean and critical nesting beaches are scattered across several countries.

Major threats to loggerhead turtle populations here are listed as including climate change, marine debris - entanglement and ingestion, chemical and terrestrial discharge, light pollution and fisheries bycatch. Other threats include feral animal predation, habitat modification and boat strike.

Climate change impacts appear to be affecting nesting sand temperatures with changes in hatchling sex ratios and emergence success and increased extreme weather events resulting in erosion of nesting sites.

Light pollution: Lights from coastal development results in changed light horizons, which causes increased mortality of hatchlings when they move towards stronger light sources inland instead of the low horizon out at sea. There is also a decline in the recruitment of new adults to nesting populations on lit beaches as they avoid brightly illuminated beaches.

Crab pots: Loggerhead turtles get tangled and drown in commercial and recreational crab pots and their float lines. Trap types that cause an impact include round crab pots, collapsible pots, and spanner crab traps.

Underside of a loggerhead sea turtle as it swims overhead. Photo: Lance Miller

Lyn Millett OAM, WIRES Wildlife Carer For Decades

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

My favourite local wildlife species is the Grey-headed flying fox, especially the pups.

Why do you like flying foxes?

Flying foxes are very intelligent animals and unlike possums who are marsupials, they are mammals, like dogs and cats. Therefore they raise their babies with love and lots of attention. This is such a change for us marsupial carers and raisers (who have to keep the joeys as wild as possible) as we can give them names and cuddle them, carry them around and bond with them as this is best for their early days. Flying Fox babies are all born around the same time, in spring, and by mid summer they are 10 - 12 weeks old and off to creche so we only get to enjoy them for a short time. It is like raising a human baby in that they have dummies, nappies are wrapped and put to bed after each feed in the early weeks with bathtime in the middle of the day. As they get older they hang on a frame during the day, and when they see you they reach out for a cuddle. Such affectionate little things. Dave and I are both trained and vaccinated so some seasons we have a pup each and they are company for each other. As there are several flying fox colonies in our area we usually get local pups that have lost mum. Sometimes we have been able to reunite them with their mums but more often we get them from dead mums that have been electrocuted on power lines. Even though mum is dead, the baby can survive for several days.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

We have been carers for about 25 years and most years we have had pups to raise. Occasionally we get in adults, especially in summer when fig trees are fruiting and have been netted as very easy for them to get entangled in the netting.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

Flying fox colonies come and go depending on the available food in the area. Sometimes there can be hundreds locally and other times very reduced numbers.

We are so lucky to have them in our area as they are masters at dispersal of seeds to regenerate native plants.

Mother with near-mature pup. Photo: Andrew Mercer

Lynette Millett OAM. Photo: Michael Mannington OAM

Flying Foxes Information

Also visit: Kukundi Wildlife Shelter

There have been 338 Grey-headed Flying-foxes rescued locally in the period of data collated from June 2013 to June 2021 with 83 released. There have been 393 Flying-foxes rescued in this LGA during the same timeframe with just 2 released. The 2015-2016 period saw 'weather' as the highest cause of mortality. Electrocution features as causing a high mortality, 'fallen from nest', 'unsuitable environment' and 'attack' by an introduced predator or domestic pet are also listed.

The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) is a megabat native to Australia. The species shares mainland Australia with three other members of the genus Pteropus: the little red P. scapulatus, spectacled P. conspicillatus, and the black P. alecto.

There are three known roosts in our LGA.

Grey-headed flying foxes live in a variety of habitats, including rainforests, woodlands, and swamps. Roost vegetation includes rainforest patches, stands of melaleuca, mangroves, and riparian vegetation, but roosts also occupy highly modified vegetation in urban areas.

Movements of grey-headed flying foxes are influenced by the availability of food. Their population is very fluid, as they move in response to the irregular blossoming of certain plant species. They are keystone pollinators and seed dispersers of over 100 species of native trees and plants.

Around dusk, grey-headed flying foxes leave the roost and travel up to 50 km a night to feed on pollen, nectar and fruit. The species consumes fruit flowers and pollens of around 187 plant species. These include eucalypt, particularly Corymbia gummifera, Eucalyptus muelleriana, E. globoidea and E. botryoides, and fruits from a wide range of rainforest trees, including members of the genus Ficus. These bats are considered sequential specialists, since they feed on a variety of foods. Grey-headed flying foxes, along with the three other Australian flying fox species, fulfill a very important ecological role by dispersing the pollen and seeds of a wide range of native Australian plants. The grey-headed flying fox is the only mammalian nectarivore and frugivore to occupy substantial areas of subtropical rainforests, so is of key importance to those forests.

The grey-headed flying fox is now a prominent federal conservation problem in Australia. Early in the last century, the species was considered abundant, with numbers estimated in the many millions. In recent years, though, evidence has been accumulating that the species is in serious decline. An estimate for the species in 2019 put the number at 586,000 and the national population may have declined by over 30% between 1989 and 1999 alone.

As they are a keystone species their demise would lead to our own.

Grey-headed flying foxes are exposed to several threats, including loss of foraging and roosting habitat, competition with the black flying fox, and mass die-offs caused by extreme temperature events. When present in urban environments, grey-headed flying foxes are sometimes perceived as a nuisance.

Because their roosting and foraging habits bring the species into conflict with humans, they suffer from direct killing of animals in orchards and harassment and destruction of roosts. Negative public perception of the species has intensified with the discovery of three recently emerged zoonotic viruses that are potentially fatal to humans: Hendra virus, Australian bat lyssavirus and Menangle virus. However, only Australian bat lyssavirus is known from two isolated cases to be directly transmissible from bats to humans. No person has ever died from ABLV (Lyssavirus) after having had the ABLV post-exposure vaccine.

The urbanised camps of cities were noted as succumbing to poisoning during the 1970s to 1980s, identified as the lead in petrol that would accumulate on the fur and enter the body when grooming. The mortality rate from toxic levels of lead in the environment dropped with the introduction of unleaded fuel in 1985. An introduced plant, the cocos palm Syagrus romanzoffiana, now banned by some local councils, bears fruit that is toxic to this species and has resulted in their death; the Chinese elm Ulmus parvifolia and privet present this same hazard. The species is vulnerable to diseases that may kill large numbers within a camp, and the sudden incidence of premature births in colonies is likely to significantly impact the re-population of the group; the cause of these disorders or diseases in unknown.

Recent research has shown thousands of grey-headed flying foxes have died from extreme heat events. Unsuitable backyard fruit tree netting also kills many animals and may bring them into close contact with humans, but can be avoided by using wildlife-safe netting. Barbed wire accounts for many casualties; this can be ameliorated by removing old or unnecessary barbed wire or marking it with bright paint.

The early twentieth century saw the incursion of Pteropus poliocephalus to the opportunities they discovered at orchards, and the government placed a bounty on the declared pest. Their reputation for destroying fruit crops was noted by John Gould in 1863, though the extent of actual damage was often greatly exaggerated. When Ratcliffe submitted his report, he noted the number of paid bounties was 300,000, and this would not have included the mortally wounded escapees or those left suspended at roosts by the grip that is held by their weight.

This species continued to be killed or wounded by shotguns, many remaining disabled where they fell after the bounty was stopped, despite the advice of Ratcliffe and later researchers on an ineffective and uneconomical practice and the needless extermination of the population.

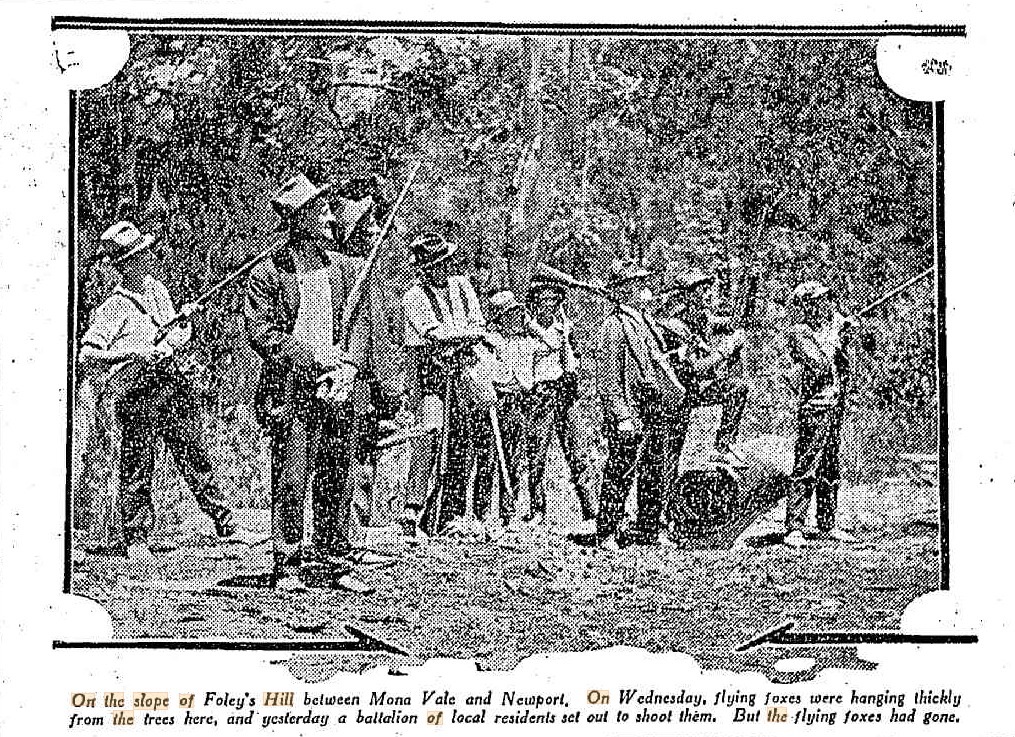

FOXES FLEW

HUNT THAT WASN'T MONA VALE BATTLE

It was the strangest of fox hunts No red coats flashed. No horses streaked across" the landscape. No hounds bayed or waggled their wet red tongues.

No hunting horns sounded echoing blasts. No pretty huntresses skimmed across fences, with the tang of the tonic air turning cheeks pink. And, strangest thing of all, there was no fox! It all happened not at a romantic-ally-named Chevy Chase or Tavis tock 'Downs, but at prosaic Cabbage Tree Gully, Mona Vale. It was a severely, masculine affair— only men and boys and fox terriers and guns.

But It was not a hunt. Certainly it' was intended that it should have been more. Flying foxes have been swooping down from the forest-terraced hills beyond Mona Vale. Like mountain brigands, they have raided the orchards about Newport, Pittwater, and as far afield as Pymble. A trail of peaches, apples, and early plums, all scarred by tiny teeth, has been left under the trees. This tyranny became remorseless. Flying foxes have been getting the fruitgrowers under their iron wing. So war was declared. The whole district rose up in revolt. Rifles were oiled. Cartridges were gathered. Dogs were given more meat. Scouting par ties went out.

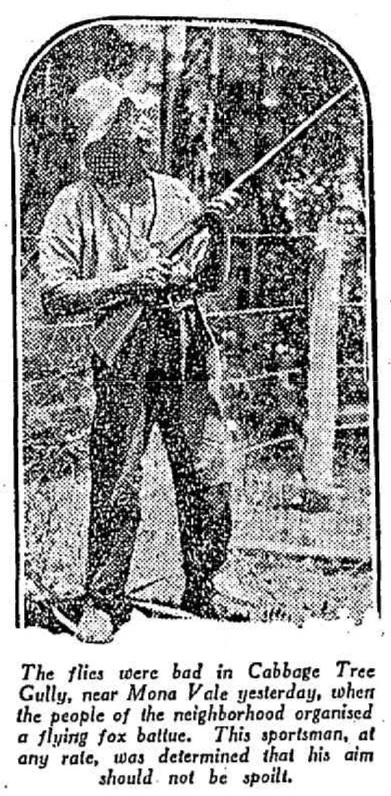

The flies were bad in Cabbage Tree Gully, near Mona Vale yesterday, when the people of the neighbourhood organised a flying fox battle. This sportsman, at any rate, was determined that his aim should not be spoilt.

IS IT WAR!

Someone spoke of a LEWIS gun. Someone else told how one had been trained on a big ironbark whose every branch "was draped with clinging foxes, it had failed miserably, chopped off branches and- only scattered the, inhabitants. A youth suggested poison gas. He was eyed with indulgent pity.

"Shoot 'em out!" was the verdict of the oldest bushmen in the district. It went. Guerilla bands yesterday morning gathered in a paddock of ferns near the Pittwater-road. Grim sun-tanned men strode out or the bush with guns, and bandoliers! Aged bushmen, hardy warriors with Visors of fly net across their lulw. strode out of the bush with guns and bandoliers! Boys of 16 and 17 strode out of the bush with guns and bandoliers! Two fox terriers playing the role of the pack of hounds had the light of battle in their eyes. Cicadas on every side did more baying than any string of dogs. ;

ARMY ON THE MOVE

On Wednesday the lair of the flying bandits had been found. Many hundreds of them gave a couple of iron-barks and sheoaks a living brown-grey foliage in a wall of green on a 'hillside.

"You can't miss 'em," said one optimist.

"I'll lay three to one you don't get a fox," retorted Gus Anderson, who knows every piece, of fern from Narrabeen to Newport.

Then began the climb up the gully. The armed party looked like a Boer commando or one half of a Kentucky feud. Later It looked like a string of Tyrolese mountaineers as men and boys shinned and slid up and down brown rock faces and the steep -timber strewn wall of the gully.

They fought through waves of ferns and wild palms and wild apple Scrub. They crept through black aisles of sheoaks, turpentines, and Ironbark, gloomy as a pillared cathedral. Then across the gully rattled a shot. "It's all right, it's only a pigeon, blokes," echoed a far-away voice from the green ocean of leaves.

Hopes that had soared crashed again.

"Keep quiet, we'll hear 'em squeal, ordered someone. The punitive expedition, even to the terrier, seemed to hold its collective breath. But when you began to listen Intently It was brought home vividly how really clamorous the bush can become. Birds screamed and chattered, and the symphony of the cicadas had swelled to a crashing chorus.

"Blow'd if a man could hear them squeal," exclaimed one hunter, disgustedly.

NOT A FOX SEEN

After what seemed an age of scrambling over dry logs and slipping on oak needles the bandits' lair was reached. Not a fox draped a twig. Faces fell.

Tired men and boys sank on to logs.

"Gus Anderson was right. They’ve gone to Deep Water Creek," they panted.

Striking toward the coast, the army worked through the moist heated forest to the head of Cabbage Tree Gully and around to Spear's Point; a butto of rock that rises from .the bronze green forest ocean. Not a fox was seen. Shots were fired. But, there was no squealing scurry from the branches.

An aged fruitgrower at Cabbage Tree' Gully turned disappointment to despair. He said he had not seen a flying fox over his fruit trees for two days — not since a boy had a few shots from a pea-rifle somewhere in the gully on Thursday. The army halted. Faces glistened with sweat.

Everyone was hot. tired, and dusty.

A Mona Vale David, single handed, had put to flight the winged terror to which 30 men had sought to give battle.

The flying foxes had flown!

Hunters were out till last evening, but no reports were received of the foxy bandits having been traced.

FOXES FLEW (1926, December 5). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article224130852 -

Orchardists have begun shifting to the use of netting that also discourages the daytime visits of birds.

The impact of indiscriminate shooting of bats has resulted in the species being declared vulnerable to extinction, to the tree species that relied on them for regeneration, the subsequent alteration to the forest ecology of the eastern states.

To answer some of the growing threats, roost sites have been legally protected since 1986 in New South Wales and since 1994 in Queensland. In 1999, the species was classified as "Vulnerable to extinction" in The Action Plan for Australian Bats, and has since been protected across its range under Australian federal law, listed as Vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). A species recovery plan was created by the federal Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment and the South Australian Department for Environment and Water and published in 2021.

As of 2021 the species is listed as "Vulnerable" on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species under criteria A2ace and A4ac. Justification for the assessment says that "although the population is relatively large (exceeding 10,000 mature individuals) and it has a large extent of occurrence (> 20,000 km²), a continuing population decline is inferred to be more than 30–35% over the last three generations", and that further decline is expected.

Baby flying foxes usually come into care after having been separated from their mothers. Babies are often orphaned during four to six weeks of age, when they inadvertently fall off their mothers during flight, often due to disease or tick paralysis (their own and/or that of the mother).

Bat caregivers are not only specially trained in techniques to rescue and rehabilitate bats, but they are also vaccinated against rabies. Although the chance of contracting the rabies-like Australian bat lyssavirus is extremely small, bat caregivers are inoculated for their own protection and as a requirement to care for these little ones.

Crib full of babies rescued by Wildcare Australia in care at The Bat Hospital. Photo: Wcawikinfo

Kevin Murray: Our Backyard Frogs

One of the first things we did when we moved into our Warriewood house nearly 50 years ago was to install an above-ground pool. This pool gave us years of fun but as our nephews and nieces grew older it got used less and less. The day arrived when we decided it had to go, to be replaced by numerous plants that would eventually grow into a small forest. One end of the pool was below ground so, rather than fill in the remaining hole, we installed a large fishpond (and two smaller, shallower ones) which we populated with fish that did little other than supply sustenance for our resident Kookaburras and a very thankful Heron.

So we decided that frogs might enjoy our backyard watery accommodation. We collected a handful of frog spawn from a friend in Frenchs Forest, plonked it in the pond and we have been enjoying the subsequent summertime croakings of generations of their descendants ever since.

There are now two species of frog that serenade us (and our neighbours) through the long summer nights, especially after rain. The main one is the Striped Marsh Frog, whose loud ‘tok’ call can sound like there’s a tennis match going on in the darkness of our our backyard. Between September and April they lay their myriad of small black eggs, embedded in distinctive white foam rafts. These eggs hatch into tiny black tadpoles, most of which, as is Nature’s way, die. Those that do survive slowly grow into large, pitch-black tadpoles that, after about a year, lose their tails, sprout legs and develop the distinctive markings that define them as Striped Marsh Frogs. They can then leave the aquatic confines of our pond and explore the rest of our frog-friendly, leaf-littered backyard.

Striped Marsh Frog

The other species of frog that inhabits our backyard is the Peron’s Tree Frog. We know when one is there by its distinctive call, which sounds like a jackhammer crossed with a machine gun. The Peron’s Tree Frog is a relatively large tree frog, growing up to 7cm in length and, interestingly, can change the colour of its entire body in a matter of seconds. Depending on temperature, time of day and humidity they can appear brown, green or white. During the day they will usually take on a white colour and at night they tend to look brown with mottled yellow thighs. November is the middle of their breeding season, when the noise levels will be at their peak. The male tree frog calls from high up in a tree but he has also developed a cunning tactic of sometimes using the downpipes in our house to amplify his calls to potential mates.

Peron's Tree Frog

It might seem strange, but we get much more pleasure now from hearing the reassuring cacophony of our backyard frogs than we ever got from that sterile swimming pool. I thoroughly recommend the transformation from pool to pond – or should that be “metamorphosis”?

Photos: Kevin Murray

Kevin Murray

Frogs Information

The main threats to our local frog populations are loss of habitat, pollutant runoff into the creeks and ditches they inhabit, and:

Wanted: Photos Of Flies Feeding On Frogs (For Frog Conservation)

Do you have any photos of frogs being bitten by flies? Submit them to our study to help in frog conservation.

By sampling the blood of flies that bite frogs, researchers can determine the (sometimes difficult to spot) frogs in an environment.

UNSW Science and the Australian Museum want your photos of frogs, specifically those being bitten by flies, for a new (and inventive) technique to detect and protect our threatened frog species.

You might not guess it, but biting flies – such as midges and mosquitoes – are excellent tools for science. The blood ‘sampled’ by these parasites contains precious genetic data about the animals they feed on (such as frogs), but first, researchers need to know which parasitic flies are biting which frogs. And this is why they need you to submit your photos.

“Rare frogs can be very hard to find during traditional scientific expeditions,” says PhD student Timothy Cutajar, leading the project. “Species that are rare or cryptic [inconspicuous] can be easily missed, so it turns out the best way to detect some species might be through their parasites.”

The technique is called ‘iDNA’, short for invertebrate-derived DNA, and researchers Mr Cutajar and Dr Jodi Rowley from UNSW Science and the Australian Museum were the first to harness its potential for detecting cryptic or threatened species of frogs.

The team first deployed this technique in 2018 by capturing frog-biting flies in habitats shared with frogs. Not unlike the premise of Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park, where the DNA of blood-meals past is contained in the bellies of the flies, Mr Cutajar was able to extract the drawn blood (and therefore DNA) and identify the species of amphibian the flies had recently fed on.

These initial trials uncovered the presence of rare frogs that traditional searching methods had missed.

“iDNA has the potential to become a standard frog survey technique,” says Mr Cutajar. “[It could help] in the discovery of new species or even the rediscovery of species thought to be extinct, so I want to continue developing techniques for frog iDNA surveys. However, there is still so much we don’t yet know about how frogs and flies interact.”

In a bid to understand the varieties of parasites that feed on frogs – so Mr Cutajar and colleagues might lure and catch those most informative and prolific species – the team are looking to the public for their frog photos.

“If you’ve photographed frogs in Australia, I’d love for you to closely examine your pictures, looking for any frogs that have flies, midges or mosquitoes sitting on them. If you find flies, midges or mosquitoes in direct contact with frogs in any of your photos, please share them.”

Mountain Stream Tree Frog (Litoria barringtonensis) being bitten by Sycorax. Photo: Tim Cutajar/Australian Museum

“We’ll be combing through photographs of frogs submitted through our survey,” says Mr Cutajar, “homing in on the characteristics that make a frog species a likely target for frog-biting flies.

“It’s unlikely that all frogs are equally parasitised. Some frogs have natural insect repellents, while others can swat flies away. The flies themselves can be choosy about the types of sounds they’re attracted to, and probably aren’t evenly abundant everywhere.”

Already the new iDNA technique, championed in herpetology by Mr Cutajar, has shown great promise, and by refining its methodology with data submitted by the public – citizen scientists – our understanding of frog ecology and biodiversity can be broadened yet further.

“The power of collective action can be amazing for science,” says Mr Cutajar, “and with your help, we can kickstart a new era of improved detection, and therefore conservation, of our amazing amphibian diversity.”

Read more: Frogs are dying en masse again, and we need your help to find out why

Greens Councillor Miranda Korzy’s Favourite Local Wildlife Species

The first time I saw a brushtail possum up close was as a student at the ANU (Australian National University) in Canberra 40 years ago. Trees around the university provided homes for lots of wildlife including Sulphur Crested Cockatoos, who would hang upside down in them outside my room on campus - looking like hundreds of white socks pegged out to dry. You’d also see lots of possums in the trees too if you were walking home on a moonlit night.

On one of these nights, an extremely excited Sri Lankan flatmate came running into our lounge room shouting “Mongoose, mongoose,” grasping a screeching brushtail in front of him. With lots of scratching and struggling the “mongoose” escaped, running around the floor, leaving a trail of droppings behind until someone was able to catch it with a large rug and return it outside. The thing that really impressed me about that possum was how long and sharp its claws were - and the evidence they left behind on our Sri Lankan friend. Its furry tail and cute face, with its big eyes and pink nose, disguised a very determined creature, well able to climb trees and defend its territory.

Moving to Avalon some 20 years ago, wildlife became a feature of our everyday lives again. Amongst them were the ticks, the bandicoots that would join us uninvited on our verandah when we had barbecues, and the brushtails we’d see running along the guttering on our neighbours’ roof at night. I don’t know why we never had them in our roof, but there were plenty around, and we’d sometimes see one of the local dogs who roamed free eating a possum dinner.

In those days, brushtail possums were ubiquitous, thriving on the edges of urban life. I vividly remember a meeting one night at Avalon OOSH, where one of the topics under discussion was how to remove the resident possum from the roof. Suddenly, a stream of urine poured from the ceiling in a steady flow.

Later, living in another part of Avalon, my kids found an apparently very tame brushtail in a wattle tree across the street. This time we carefully approached it with a thick towel - but it didn’t put up a fight when we wrapped it up and took it to the vet. The vet said it had some sort of infection; it was underweight and had clearly not eaten for some time, too far gone to nurse back to health.

Then there was the spring we planted a row of corn. We watered the seed and watched the ears grow over the weeks, until one night we decided the now large cobs would be ready to harvest the next day. Inspecting our crop 24 hours later, it was a shock and extremely disappointing to peel back their green overcoats and discover every single cob had been eaten overnight, after some visitor, presumably a possum, had got there first.

It’s a while since I’ve seen a possum around our place. They used to visit our roof, but it’s been fairly silent up there for a couple of years now - except during the wettest weather. I know I should be grateful, given the mess they can make. And a wildlife-carer friend tells me she would rather wrangle a snake than a brushtail! But apart from providing food for other species like Powerful Owls and Diamond Pythons, I like them for their grit - as well as their model good looks!

Cr. Miranda Korzy

Brushies Information

There have been 7,118 possums rescued in our LGA area from June 2013 to June 2021, 1,978 were released.

There have been 3.351 cuscus and possums rescued in our LGA area from June 2013 to June 2021, 820 were re-released.

There have been 20 Eastern Pygmy possums and Feathertail gliders rescued acrsoss the LGA - habitat alteration and tree felling has caused the bulk of rescues, and in 2015 to 2017 was the highest occurrence. Of those rescued just 14 were released.

A tiny shy nocturnal possum, these are not always found before a tree is cut down and would not be seen among the debris.

For the cus cus collisions with with motor vehciles is listed as the most common reason for rescue, followed by 'unsuitable environment' (in someone's roof for example), and then 'parent taken into care' - due to cat attack, 96 of these in 2020/2021 alone, or 'fallen from nest' - a spring time dilemma - 158 of these in 2020/2021 and one that would account for many of those re-released.

Brushies 'fell from nest' into 60 rescues during 2020/2021, there were 39 recorded attacks by a cat, 14 'rescued' due to being in an unsuitbale enviroment - rooves, trees that are about to be cut down - and 10 which had been hit by a car.

It's importnat to remember that those rescued due to being 'hit by a car' is not the same as those who could not be rescued because they have been killed by a car. More on those statsics soon.

Cuscus is the common name generally given to the species within the four genera of Australasian possum of the family Phalangeridae with the most tropical distribution:

- Ailurops

- Phalanger

- Spilocuscus

- Strigocuscus

Locally we also have the Pygmy Possum and a project that commenced in May 2015 in our offshore community as a monitoring program to establish data on the location, frequency and seasonal movements of the Eastern Pygmy Possum on the Western Shores of Pittwater. Other visitors to the nesting boxes, such as Feather-tailed Gliders and Antechinus, are also recorded.

The funding applicant, Rocky Point Bushcare, was provided with mini grant of $1500, awarded by Greater Sydney Local Land Services, to fund the purchase of 2 high quality wildlife cameras and backed by Pittwater Council, the Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA), and local state member Rob Stokes.

Twenty-nine nesting boxes were purchased by residents and placed at the back of properties throughout Elvina Bay, Lovett Bay and Towlers Bay.

The common brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula, from the Greek for "furry tailed" and the Latin for "little fox", previously in the genus Phalangista) is a nocturnal, semiarboreal marsupial of the family Phalangeridae, native to Australia.

The common brushtail possum is largely arboreal and nocturnal. The common brushtail possum can breed at any time of the year, but breeding tends to peak in spring, from September to November, and in autumn, from March to May, in some areas. A newborn brushtail possum is only 1.5 cm long and weighs only 2 g. As usual for marsupials, the newborn may climb, unaided, through the female's fur and into the pouch and attach to a teat. The young develops and remains inside the mother's pouch for another 4–5 months. When older, the young is left in the den or rides on its mother's back until it is 7–9 months old. Brushtail possums can live up to 13 years in the wild.

Brushtail possum with young. Photo: Bryce McQuillan

Although once hunted extensively for its fur in Australia, the common brushtail possum is now protected in mainland states, but it has only been partially protected in Tasmania, where an annual hunting season is used. In addition, Tasmania gives crop-protection permits to landowners whose property has been damaged.

Populations of all these species are declining in due to habitat loss and cats that are allowed to be outdoors at night and attack them.

The Brushie has a mostly solitary lifestyle, and individuals keep their distance with scent markings (urinating) and vocalisations. They usually make their dens in natural places such as tree hollows and caves, but also use spaces in the roofs of houses.

Brushtail possums compete with each other and other animals for den spaces, and this contributes to their mortality, as does removing them from rooves and dumping them in the bush - here too they will meet other brushtail possums that will chase them off. Brushies are also particular about what they eat and like the taste of what grows in their home grounds - dumping will lead to starvation.

These too, are not so 'common' anymore.

Pittwater: Urban Wallabies

Report fox sightings

Fox sightings, signs of fox activity, den locations and attacks on native or domestic animals can be reported into FoxScan. FoxScan is a free resource for residents, community groups, local Councils, and other land managers to record and report fox sightings and control activities. Our Council's Invasive species Team receives an alert when an entry is made into FoxScan. The information in FoxScan will assist with planning fox control activities and to notify the community when and where foxes are active.

Report where and when at: https://www.feralscan.org.au/foxscan/default.aspx

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

More in:

- Ringtail Posse 2023: The Generation Witnessing An Extinction Of Urban Wildlife

- Motion To Have Fauna Management Plans In Local Council Comply With The NSW Code Of Practice For Injured, Sick And Orphaned Protected Fauna To Be Presented At LGNSW 2022 Conference - Some FMP's Passed Allow For Wildlife To Be Killed Where Their Homes Are Felled

- Spring Carnage For Our Wildlife: Out Of Date Data Shows At Least 4000 Local Rescues Annually - Lack Of 'Responsibility' Facilitates Extinctions

- Masked Lapwing Plover Chicks Were In Danger: Now They're Dead Because No One Is 'Responsible' For Wildlife In Council Areas