April 16 - 22 2023: Issue 579

Ringtail Posse 3 - April 2023

Jeffrey Quinn: Kookaburra, Tom Borg McGee: Kookaburra, Stephanie Galloway-Brown: Bandicoot, Joe Mills: Noisy Miner

Definition from

Ringtail: from the 'Common Ringtail Possum' which is not so common anymore in urban areas. The Common Ringtail Possum is found along the entire eastern part of Australia and south west Western Australia. They are also found throughout Tasmania. The western ringtail possum is a threatened species under State and Commonwealth legislation. In Western Australia the species is listed as Critically Endangered fauna under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.+

Posse: noun. 1 : a large group often with a common interest 2 : a body of persons summoned by a sheriff to assist in preserving the public peace usually in an emergency 3 : a group of people temporarily organised to make a search (as for a lost child) 4 : one's attendants or associates.

In recent approved DA’s Council is listing as a requirement of consent in Assessment reports to look after the other residents of this area, the wildlife. On blocks where people wish to remove large amounts of trees that are clearly homes for local fauna a wildlife expert must assess these prior to any removal taking place, nesting boxes are required to be installed afterward and Ecologists must be on site during their removal. Other recent examples and instances are:

Bandicoot/Penguin (Avalon)

Long-nosed Bandicoots & Little Penguins – Best Practices for Residents

Residents are encouraged to follow a number of Best Practices to assist with the protection and management of the endangered populations of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins:

Long-nosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other native animals should never be fed as it may cause them nutritional problems, hardship if supplementary feeding is stopped, and it may increase predation.

Feral cats or foxes should never be fed or food left out where they can access it, such as rubbish bins without lids or pet food bowls, as these animals present a significant threat to Longnosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other wildlife.

The use of insecticides, fertilisers, poisons and/or baits should be avoided on the property.

Garden insects will be kept in low numbers if Long-nosed Bandicoots are present.

When the North Head Long-nosed Bandicoot Recovery Plan is released it should be implemented where relevant.

Dead Long-nosed Bandicoots or Little Penguins should be reported by phoning Manly Council on 9976 1500 or Department of Environment and Conservation on 9960 6266.

Please drive carefully as vehicle related injuries and deaths of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins have occurred in the area. Care should also be taken at night in the drive way when moving cars as bandicoots will seek shelter beneath vehicles.

Cat/s and or dog/s that currently live on the property should be kept indoors at night to avoid disturbance/death of native animals. Ideally, when the current cat/s and/or dog/s that live on the property no longer reside on the property it is recommended that they not be replaced by new dogs or cats.

Report all sightings of feral rabbits, feral or stray cats and/or foxes to N B Council.

And;

Dead or Injured Wildlife (Palm Beach)

If construction activity associated with this development results in injury or death of a native mammal, bird, reptile or amphibian, a registered wildlife rescue and rehabilitation organisation must be contacted for advice.Protection of Habitat Features

All natural landscape features, including any rock outcrops, native vegetation and/or watercourses, are to remain undisturbed during the construction works, except where affected by necessary works detailed on approved plans.

Reason: To protect wildlife habitat.

The Reason given in all instances is: To protect native wildlife.

This follows on from the 2022 Local Government NSW Conference where a Motion was passed - That Local Government NSW lobby the NSW Government to:

- In conjunction with industry associations, introduce enforceable standards for the preparation of flora and fauna management plans.

- Consider Codes of Practice and Guidelines for handling native wildlife and other best practice and animal welfare laws in development of the standards.

- Consult with Councils, National Parks and Wildlife Service, Ecological Consultants Association of NSW, wildlife rescue organisations and other relevant agencies in the preparation of standards.

Such a standard should include requirements for:

- Pre-clearance surveys to be carried out to establish which species are present on the site, including identification of any threatened and native species.

- The identification of suitable nearby areas where wildlife could possibly be relocated.

- The provision of possum, glider and bat boxes sufficiently in advance of vegetation clearing to allow wildlife time to discover the boxes and become familiar with them.

- Compliance with the NSW Code of Practice for Injured, Sick and Orphaned Protected Fauna and the licencing requirements contained in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

- Best practice for wildlife handling and care (including contact with local wildlife rescue groups).

- Reporting of injured or killed fauna to the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment to enable the data to be used in statewide biodiversity monitoring programs.

The premise of this is that mandatory pre-clearance surveys to establish what wildlife lives there before works commence, and to document this in a formal way, should be required on any site that has vegetation and for which a DA has been approved. The experience is that often vegetation is removed before an application is submitted, often leaving wildlife with no home. Wildlife then ends up on roads dead or dies after being displaced/evicted.

One wildlife carer cited a recent Pittwater case of a powerful owl pair site that had had vegetation removed to make the development more likely to proceed – the nest and two babies were destroyed.

‘It’s hard to prove wildlife is/was present after the clearing as they aren’t there.’

‘Once trees and vegetation are removed the problem is where do these animals go?’

Powerful Owls are also not so common anymore in urban areas.

However it's clear human residents of this LGA have a deep and abiding love for and connection to these other furry, scaled, finned and feathered beings. We listen for them during the night, happy when we hear their footsteps scampering across our rooves or their soft hoots across the valleys.

Human residents are distressed when they find injured wildlife or witness wildlife being attacked.

Data kept by the NSW Environment Department, although only listing incidents from June 2013 to June 30 2020, shows that 28,542 wildlife animals have been rescued in our area between June 2013 and June 30 2020. That's well over 4000 each year. Of these 41 were threatened species (504 threatened animals rescued - only 111 threatened animals released).

''This study draws on 469,553 rescues reported over six years by wildlife rehabilitators for 688 species of bird, reptile, and mammal from New South Wales, Australia.... Of the 364,461 rescues for which the fate of an animal was known, 92% fell within two categories: ‘dead’, ‘died or euthanised’ (54.8% of rescues with known fate) and animals that recovered and were subsequently released (37.1% of rescues with known fate).''In total, there were 872,087 records reported during the six-year (2013–14 to 2018–19) study period. Just over 97% of these came from three animal groups–birds, mammals, and reptiles. Of the total number of records, 402,534, (46%) were excluded from the descriptive analysis because they: a) did not contain any information about the animal, or the animal’s identification was ambiguous and could not be placed within a group (e.g. an ‘unidentified animal’); b) contained only sightings of animals and were not attended to in some way by a wildlife rehabilitator; c) were records of amphibians (373 records) or non-vertebrate fauna (e.g. spiders, insects, etc.); d) were non-avian marine vertebrates such as whales, seals, sharks, rays, fish etc; e) were reported as floating, drowned, or washed up animals (deemed an ambiguous cause for rescue, n = 48); f) contained both an ‘unknown’ cause for rescue and an ‘unknown’ fate; or f) were an introduced or spurious species (e.g. extinct, or out of known range). These exclusions resulted in a dataset for descriptive analysis of 469,553 records i.e. 54% of the initially reported amount.''

Data to 30 June 2021 lists of the 5, 235 animals rescued during that 2020 to 2021 period just 1,573 were released. Across NSW during that same year a total 120, 927 animals were rescued and just 28, 805 released - 5, 122 of these were were threatened species (104 kinds) of which just 1,180 were released.

These figures and data do not take into account all the wildlife found deceased beside or on roads or elsewhere.

Many people state we are the generation witnessing the extinction of urban wildlife. There has been generation after generation of humans living alongside and with wildlife, until this one.

It's not just the Pittwater koalas that have gone, other species, like the ringtail possum or long-nosed bandicoot are disappearing, along with their joyful snuffles and squeaks, from our urban backyards and the trees that tower over them.

There is a growing silence at night for those species that forage for food then - possums, wallabies, owls. The same is occurring for those that are active during daylight.

Although many point to the impacts of cat and dog attacks due to irresponsible owner, there is also what is termed the 'inconvenient possum' in a roof or garden shed, because its home tree has been cut down. These are caught by those hired, some of whom have little knowledge or scruples, and release them into areas out of their home range - a death sentence for that possum as this species is territorial, along with requiring certain food trees in order to eat, to survive.

There is predation by other introduced species - readers regularly send in photos and videos of foxes roaming and killing at night.

There are roadkill black spots, places where wallabies or turtles or possums used to cross the area where a road has been cut through and a speed limit that means death for wildlife. There are no 'speed humps' in place, and no plan at a local, state or federal government level to istall these. Residents and wildlife rescuers have reported some drivers 'aiming straight for' a stricken animal.

There is the razing of blocks of land for development prior to any required assessment of the environment taking place to circumvent those requirements so a report can state 'nothing present'. There is nothing present because its habitat has been cleared or the wildlife killed by these actions.

Our local wildlife carers are getting exhuasted, state there have been so many, too many so far this summer - they are increasingly heartbroken with all the babies they lose, they cry every day, and then pick themselves up and get on with trying to save the next critter, and the next.

Wildlife carers are all volunteers - they do the rescues, sometimes horrific rescues, run to and fro from the great local vets who help out trying to save them, they gather or pay for the food, for the milk, for the petrol, for the electricty to keep bubs warm. There are no grants or funding for Australia's wildlife carers - they have to raise funds through running events, raising awareness, collecting cans for a 10 cent return.

Similarly we are not in denial that all our local wildlife feels and thinks - they cry when their babies are killed in front of them, mourn the loss of a mate - people who have heard this or seen this never forget.

This year a celebration of residents' favourite wildlife will run as Profiles across 2023 - simply to allow those who love their chosen 'critter' to speak for them a little, to remind us of what is here and what we feel connected to has feelings too.

Information about these species and how many or why we are losing them will also be included - just so we can think about how we, as individuals and as one community, can turn around that growing silence and emptiness closing in around us and these other ones we love.

Ultimately the founders of the Ringtail Posse are hoping everyone here chooses to become a Member of the Ringtail Posse and keep their other loved one ever present in their heart.

Reason?: To Protect Local Wildlife so it becomes 'common' and safer for our wildlife to be everywhere once more.

To join in please email us with 'Ringtail Posse' in the subject line - with so many local species of wildlife, vital insects and seals flopping around on the sand, there are several on the lists that haven't been claimed for guardianship yet - what's yours?

Round 3 of Ringtail Posse Profiles includes the following now officially joined Members:

Jeffrey Quinn – Labor Candidate For Pittwater In 2023 State Election

Kookaburra

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

Kookaburra

Why do you like the kookaburra?

The riot that lives all around me are just amazing. We had one that had been ostracised by the main group adopt us for a while, but we haven't seen it for about a year.

How long have seen or heard the kookaburra?

The main riot is always in earshot in the mornings or before the rain.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these birds in your local neighbourhood?

There seems to be more but they must be feeling threatened by the amount of tree felling happening in my area, around Church Point.

The laughing Kookaburra was the 4th most rescued species in our Local Government Area (LGA) during the counting period from June 2020 to June 2021 - 268 were rescued and just 112 released, which means 156 died. Collision with a motor vehicle is listed as the predominant cause for rescues and deaths. Those found dead already are not part of the statistics.

If you are hearing less kookaburras sounding out from the less trees around you, this is why. Tom Borg McGee, running below, shares his own experience of this loss.

The laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae) is a bird in the kingfisher subfamily Halcyoninae. It is a large robust kingfisher with a whitish head and a dark eye-stripe. The upperparts are mostly dark brown but there is a mottled light-blue patch on the wing coverts. The underparts are white and the tail is barred with rufous and black. The plumage of the male and female birds is similar. The territorial call is a distinctive laugh that is often delivered by several birds at the same time, and is widely used as a stock sound effect in situations that involve a jungle setting.

The laughing kookaburra is native to eastern mainland Australia, but has also been introduced to parts of New Zealand, Tasmania, and Western Australia. It occupies dry eucalypt forest, woodland, city parks and gardens. This species is sedentary and occupies the same territory throughout the year. It is monogamous, retaining the same partner for life. A breeding pair can be accompanied by up to five fully grown non-breeding offspring from previous years that help the parents defend their territory and raise their young. The laughing kookaburra generally breeds in unlined tree holes or in excavated holes in arboreal termite nests. The usual clutch is three white eggs. The parents and the helpers incubate the eggs and feed the chicks. When the chicks fledge they continue to be fed by the group for six to ten weeks until they are able to forage independently.

A predator of a wide variety of small animals, the laughing kookaburra typically waits perched on a branch until it sees an animal on the ground and then flies down and pounces on its prey. Its diet includes lizards, insects, worms, snakes, mice and are known to take goldfish out of garden ponds.

Kookaburra fledgling at Pittwater Online office. Photo: A J Guesdon

Tom Borg McGee – Volunteer Wildlife Rescuer With WIRES

Kookaburra

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

It is very difficult to choose a sole favourite local wildlife species of Pittwater, as despite many local extinctions of iconic Australian species such as the koala, echidna and swamp wallaby among many others, there are still so many incredible and loveable wild species of our living community to choose from.

However, on a very personal level, it is our iconic Laughing Kookaburra which has most greatly made my spirit smile and expanded my appreciation of the uniqueness of each wildlife individual, their life experiences and the hardships/danger they face trying to survive in this deranged human world.

Chook and Kook with Tom

Why do you like the Laughing Kookaburra?

Again, another very difficult to answer question. Because there are so many reasons to love the laughing kookaburras of Pittwater! I have rescued, released and or cared for many various age and personality kookaburras through WIRES over the past 5 years.

They like such strong, beautiful and charismatic birds with such an array of personalities.

We all know the calls of the laughing kookaburra are nostalgically Australian and literally tied to sands of time as our living environment fades into the night or day.

On a very personal level, I have chosen the laughing kookaburra because I genuinely have had the honour of getting to know, live, love and laugh with a very special kookaburra friend, who I will miss with bitter sadness for the rest of my life.

Kook truly opened my mind and my heart to the reality that we are wildlife, they live, love, laugh, share and experience their own lives just like we do, except they give everything to our world and take nothing except what they need in attempt to survive.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

I have heard the nostalgic chorus of the laughing kookaburra throughout my whole life, minus a few years spent as a child with my family in SE Asia.

Hearing the laughing kookaburra as well as all the birds of Stapleton reserve gives me great joy in the beauty and security of their existence and drive to strive to be an ambassador and warrior for their critical to our own wellbeing right to exist in prosperity.

In terms of my beloved Kook, I spent time very close to every single day over 4 years with him, and or his partner and offspring from 4 generations. Kook was my friend, my brother, my son and my spirit animal all in one. I will never be so fond and find such joy in the existence of another living being.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

I am very aware on both an individual basis, as well more broadly across the northern beaches of the acute, intensifying and long persisting extinction of the laughing kookaburra, as well as next to all other native species in Pittwater.

I have a saying, which realistically is a fact that goes “there is a million ways the wildlife suffer and die and soon there will be none”. However there are some methods of murder that are more prolific than others.

The logging, bulldozing and other destruction forms of killing and removing trees and other flora from the soils which provide the LKs with shelter, breeding sites, food and their living environment.

The excavation of the unique ancient soils from Pittwater which literally give rise to all flora, fauna and the living architecture of our home area. This emits immense amounts of carbon, forever removes the capacity for future life of any magnitude in the area and destroys unfathomable amounts of fauna and or insect numbers in the present and years to come.

King Kook was recently killed whilst hunting food for his new babies, by human speeding down Central road in their car, hit and run.

A friend of a friend’s son stopped to remove Kook’s body from the road, where I found it by coincidence 10 minutes later whilst literally going to release a juvenile kookaburra into the very nearby Toongarri Reserve.

Kook is one of dozens, if not hundreds of laughing kookaburra’s which suffer and or die due to the neglect, cruelty and chaotic dangers of our selfish, stubborn and short-sighted human society. I lose count of how many kookaburras each year I scrape off the road, that die after rescue, that cannot be rehabilitated/released and have to be euthanized by vets, and those they are lucky enough to recover from injury. There are so many ways the laughing kookaburras like all other wildlife die… the trees that provide shelter, nest hollows and food are logged and woodchipped, the soils which give rise and nourish to all flora, fauna and environmental conditions they depend on are gouged out and replaced with concrete.

History of Kook (unfinished).

On a very personal level, it is our iconic Laughing Kookaburra which has most greatly made my spirit smile and expanded my appreciation of the uniqueness of each wildlife individual and the hardships they suffer in this human dominated world.

I have visited Pittwater to see family since a young child, and have lived in the Avalon area for the last 20 years, but the last 4 years have been the most special.

I have lived for the last 4years in a dodgy rental property I describe as the center of my happiness on Nandina terrace off Central road. This old brick house which is in total and chilling shade for half the year backs straight into the incredible spotted gum rainforest left as part of Stapleton Reserve.

My friendship with the local Nandina-Stapleton Kookaburra riot started very soon after moving in, as they were fast to pick up there was an almost daily bbq meal being fired up on the balcony amongst the tree tops where they felt safe to come investigate.

To begin with, it was only a married couple of two kookaburra friends that came to ask for a bbq treat (but instead it was life insects and WIRES approved vitamin coated steak they received!), one particularly more confident, fluffy and vocal than the other.

This kookaburra was who I came to call simply 'Kook', among names such as King Kook, Daddy Kook, the real OG Kook and or Kook love of my life!

The other Kook I initially called Brutus, as this was the largest kookaburra I'd ever seen, with body, eyes and beak all large and sharp as strong kookaburra genetics should be.

I naturally assumed that Kook was the wife, and Brutus was the husband... But as I learnt the blue buttock and wing feathers of laughing kookaburras indicate a male, I realised after a year of getting to know each other that the smaller, fluffier and more confident Kook who would feed the partner, as well as more regularly fly off to carry food to their first clutch of chicks (known to me) was actually the father!

Hence the references Daddy Kook and Big Mumma Bruddi were coined.

Over the last 4 years I not only have the privilege of engaging with Kook and Bruddi every single day, but also feed, nurture, get to know and eventually name each of the dozen little kooks over the past 4 breeding seasons.

Now 3-4 chicks a year is not the standard for kookaburras, influences include the quality of nesting hollow available, genetic capacity of the parents, stresses of the environment and especially food availability.

Though lucky for Kook and Bruddi, Stapleton reserve is great old growth habitat to have as a home and with myself as well as our neighbours the Holdiks, they had a steady stream of kookaburra appropriate food in the form of life insects and insectivore multi-vitamin coated beef pieces to help them throughout the severe and chaotic storms after the black summer bushfires which drowned much of their usual prey options.

Kook, Bruddi and their fluctuating family group of up to 8 beautiful and individual kookaburras would come almost every day, often more than once to say g'day whether than be in the morning, midday or the afternoons before they roosted and laughed high up in the mighty spotted gum sentinels behind us as the sunset.

Between intense doctor of physiotherapy studies and the years of COVID restrictions on normal human engagement, I spent a particularly large and consistent amount of time with my kooka family, Kook in particular. It didn't matter what was going on in life, or how I felt at the time, seeing kook and having him hop onto my arm or fly onto my shoulder for a pat and a snack would always make me happy. It would mutually give me joy to see Kook, with his partner and offspring, hunting for them, basking in the sun, drinking from our bird bath, diving into the Holdiks pool for a swim, talking and calling and in so many ways exploring and enjoying his home just like we do.

Many of my most fond memories of Kook are of him spending minutes, sometime a dozen perching on my arm or shoulder and closing his beautiful blue eyelids as I strokes his head, neck or stomach...his usual response would be to become fluffier and fluffier in his enjoyment.

Kook was always particularly excited once his babies of the season has hatched, I always knew when this has happened. He would become particularly talkative and bouncy, I knew he was telling me they were hatched and he wanted my help to feed them. When given a wood roach, super worm, meal worms or insectivore coated beef pieces he would thank me, exclaim his success and excitement to have acquired baby sustenance by talking loudly whilst hopping up and down the balcony railing (sometimes in a circle) before taking off into flight far up into the spotted gum and Angophora dominated forest where him and Bruddi's beautiful termite mound hollow nest resided.

Kook was an incredibly special living being and the most bloody beautiful, intelligent, personable, polite and affectionate kookaburra (or any wild animal) I will ever have the honour of befriending.

I would not be the person I am today, if I did not receive the blessing of time almost every day over the past 4+ years with Kook, and his family of distinct personalities (but none like him).

The reality is, despite the uniqueness of Kook and our friendship... every wildlife member of this country is the same. They are unique and essential living beings with complex lives and personalities, many of whom form deep romantic, familial and social relationships.

They are just like us, except they are truly innocent.

I scrape or otherwise remove the dead bodies of wildlife from Central Road alone, every single week (or every day if you include any other road in Pittwater, the NB/Northern Sydney Area or callouts through WIRES!).

It is abhorrently cruel, blood-boiling, heart-breaking and unsustainable to the point of permanently damaging to the genetic variance and survival of local populations.

Kook died for no reason like almost all the others... because of the negligent choices and behaviours of humans. Because people drive their locomotive machines of death like no other life exists or matters.

Our local roads (as well as around this country) are graveyards strewn with the corpses of wildlife (and discarded rubbish).. just look.

But so few truly look and appreciate the extent of this horrible reality... Despite the population being some of the most fortunate out of 8 billion primate parasites destroying all other life on this amazing planet.

Accidents happen, shit happens, but our streets do not have to be the mass wildlife graves which they are and only worsening.

Speeds for our suburban streets can be changed, many simple but effective structural interventions to the roads can be implemented and the choices/behaviour of people driving their locomotive death machines can be changed.

The great Steve Irwin made the statement, that 'we can't save the wildlife if we don't stop killing them!'

It is the responsibility of all who drive to actively choose to drive to keep wildlife alive... that means go slow, scan the road, be prepared to slow down, stop or give a tiny fraction of your time to check if wildlife needs your help.

It only took one person, at one place, during one fleeting moment in time to speed down Central Road with little to 0 appreciation of their split second capacity to injure and kill children or adults of so many different species and families.

Kook was killed whilst looking for food for his family, and died for no reason at all but the selfish, absent minded or other negligence of a single person out of our 8 billion.

Our roads, country in general and the behaviours of individuals as well as the masses reflects gross societal, systematic and individual elements of negligence, cruelty and or short signed selfishness in regards to the wellbeing of wildlife and living country.

In that moment it was Daddy Kook that was killed, in the subsequent others it is another member of our local wildlife or human community on the road.

Drive to keep beloved wildlife and the many loved ones of others alive...

There is no reason to go beyond 40KM/H on our local streets and no reason to drive at a speed you can't watch out and react to a changing environment on our main roads.

I can only hope that Kook's little ones in the nesting hollow are able to survive without him and his family riot persevere.

Kook, King of Nandina-Stapleton I will never forget you my dear best mate..

The spotted gum forest of your home and mine will forever remind me with love of the joy, laughter and support you brought us all..

But also great sadness in your sudden, unnecessary and premature death meaning you will no longer be the laughing sun in my days.

We are wildlife.

Stephanie Galloway-Brown – Artist

Bandicoot

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

Bandicoot

Why do you like the bandicoot?

How can you not love a little Bandicoot, such a unique cute little critter. I’ve just got a soft spot for our little garden buddies but they seem a bit misunderstood. They’re nocturnal and I enjoyed sitting in the garden at night hidden in the cubby watching them fossick around for grubs and worms with their long powerful noses. They get so excited when they find a meal making funny little snorting squealing noises. Sometimes a mum would have babies on board and that’s how I discovered their pouch faces backwards like a wombats. We knick-named them snorky or snorks as we were so used to sharing our garden & hearing them every night.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

For the last 25 years I’ve been living in North Narrabeen we’ve been lucky to have them living around us.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

Yes definitely, there’s certainly not nearly as many as there used to be. Up to 10 years ago we’d hear them nightly and see the little holes they’d left in the morning but now we’re lucky if we hear one every now and then and occasionally see a few holes they’ve left. I really miss them not being around as much anymore.

Stephanie Galloway-Brown's FACE OF EXTRAORDINARY: VOLUNTEERS Exhibition and book - Photo: Stephanie and Lorrie Morgan with Lorrie's portrait behind them. Pic: A J Guesdon

There were 94 Bandicoots (long-nosed: 64 - unidentified: 29) rescued during the 2020 to 2021 period and just 34 released, so 64 lost their lives - 'unsuitable environment' is listed as the main cause for rescues, along with dog and cat attacks on this species - with dog attacks more frequent than cats. Wildlife rescuers and carers who find lactating mothers often then spend days searching for where the nest may be as there are babies to be rescued and fed as well - they are not often successful.

The data, dating from June 2013 and all that is officially available, records 409 bandicoots have been rescued in the 8 years of collecting the same and just 152 released. Overall collision with motor vehicles is listed as the big killer of rescued bandicoots and cat attacks on the same overtop the more recent upsurge of dog attacks on the bandicoot. Once again, this does not take into account all the manuy other bandicoots that are found deceased beside our roads or mauled in our urban yards.

Residents would know we are losing out local bandicoots - in a call out for information on if people had heard them going into the rounds of the Ringtail Posse answers from Balgowlah to Manly and all points north stated they had not heard them for a while. The family of bandicoots in the Pittwater Online yard that once thrived here has also not been heard for at least 2 years, although cats have been chased from the yard, hunting after dark, every night since.

Along with the long-nosed bandicoot this LGA was once home to the Southern Brown Bandicoot, however their population has been reduced to a critical level. We are most definitely losing or have lost the bulk of our bandicoots. As Tom states above - we need to drive so we don't kill our local wildlife and keep cats indoors at night and dogs away from where wildlife lives.

The NSW Department of Environment states the northern beaches from Manly to Palm Beach are one of the last strongholds for long-nosed bandicoots in the Sydney region. There are 2 significant populations: at Pittwater, and on the coast near Newport. Because it is cut off from other bandicoot populations by houses, a population of long-nosed bandicoots at North Head in Sydney Harbour National Park at Manly has been listed as endangered and was one of the first endangered population listings in New South Wales.

The Long-nosed bandicoot (Perameles nasuta) is around 31–43 cm in size and weighs up to 1.5 kg. It has pointed ears, a short tail, grey-brown fur, a white underbelly and a long snout. Its coat is bristly and rough. Gestation lasts 12.5 days, one of the shortest known of mammal species. The young spend another 50 to 54 days in the mother's pouch before being weaned.

The long-nosed bandicoot is a common prey item of the introduced red fox. and why residents are urged to report these when they see them. Report where and when at: https://www.feralscan.org.au/foxscan/default.aspx

Although the Dept. of Environment states this species is the most common species of bandicoot in the Sydney area, locals not hearing them anymore would point out they are not so common anymore.

Long-nosed Bandicoots are known to dig small, conical holes in lawns and gardens. Whilst bandicoot diggings can be unsightly, bandicoots are often helping the home gardener control grubs and garden pests. They eat insects, earthworms, insect larvae and spiders (including the venomous funnel-web spider) as well as tubers and fungi. Bandicoots are often attracted to forage on watered lawns and gardens where insect numbers are higher than in bushland, and these areas can sustain higher numbers of bandicoots.

Long-nosed Bandicoot, northern beaches, New South Wales. Photo: JJ Harrison

The Southern brown bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus) is listed as endangered in NSW. It is around 28–36 cm in size and weighs up to 1.5 kg. It has small, rounded ears, a longish, conical snout, a short, tapered tail and a yellow-brown or dark grey coat with a cream-white underbelly. They are smaller and shyer than other species and do not stray far from their preferred shelter of dense heath vegetation.

The southern brown bandicoot is patchily distributed and occurs south from the Hawkesbury River to the Victorian border and east of the Great Dividing Range.

There are 2 main populations; one lives in Garigal and Ku-ring-gai Chase national parks in northern Sydney - yet more reason to keep pets out of these places. The other lives around Ben Boyd National Park and Nadgee Nature Reserve in the far south-eastern corner of the state.

Southern brown bandicoots are nocturnal and omnivorous, feeding on insects, spiders, worms, plant roots, ferns, and fungi. Gestation lasts less than fifteen days and typically results in the birth of two or three young.

The young weigh just 350 mg (5.4 gr) at birth, remain in the pouch for about the first 53 days of life, and are fully weaned at around 60 days. Growth and maturation is relatively rapid among marsupials, with females becoming sexually mature at four to five months of age, and males at six or seven months. Lifespan in the wild is probably no more than four years.

Populations have declined markedly and become much more fragmented in the time since European expansion on the Australian mainland, much of that due to the clearing of habitat. In many areas of its range the species is threatened locally, while it may be common where rainfall is high enough and vegetation cover is thick enough. Apart from habitat fragmentation, the species is under pressure from introduced predators such as the red fox and feral cats. It has been reintroduced to some lower rainfall areas where there is protection against cat and fox predation – one such site being Wadderin Sanctuary in the eastern wheatbelt of Western Australia, 300 km east of Perth.

In national assessment, the southern brown bandicoot is currently regarded as Endangered on the mainland as a whole, and Vulnerable in South Australia.

Juvenile southern brown bandicoot. Photo; Bertram Lobert

Bandicoots have at least 4 distinct vocalisations:

- a high-pitched, bird-like noise used to locate one another

- when irritated, they will make a 'whuff, whuff' noise

- when feeling threatened or alarmed, they will make a loud 'chuff, chuff' noise and loud whistling squeak at the same time

- when in pain or experiencing fear, they will make a loud shriek.

Activities to assist this species:

- Prevent domestic cats and dogs from roaming into habitat areas.

- Protect all known and potential habitat and include linkages across the broader landscape.

- Undertake fox, feral dog and feral cat control programs.

- Apply fire regimes that maintain patches of dense ground cover and floristic and structural diversity in the habitat.

Joe Mills – Pittwater Online New Photographer, Former- Cartographer, Volunteer

Noisy Miner Bird - Shearwater Estate NBC Council Nature Reserve

My local favourite species (because they live with us in an adjoining Nature Reserve) is the much maligned NOISY MINER. Not to be confused with the Indian Mynah which is a Starling species, whilst the Noisy Miner is part of the Honey-eater (Nectar) species.

Photo: A J Guesdon

We have lived in Shearwater Estate for about 14 years (since 2009), and lived alongside their favourite territory, the NBC Nature Reserve. This has provided them with most of their needs, which are more than supplemented with water in our bird baths, and flowering plants & Lilli Pilli trees in our yard (especially when they are flowering) for their nectar supplies.

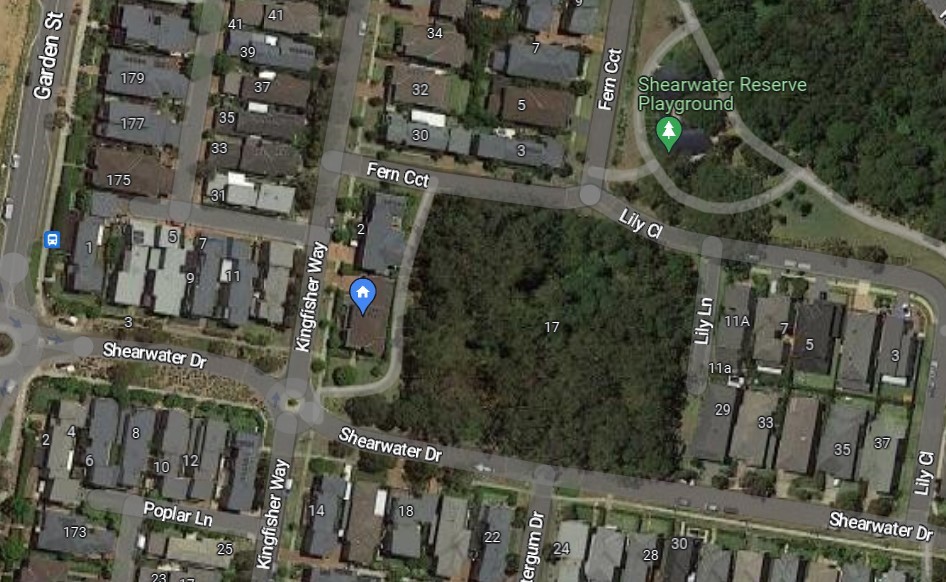

Part of Shearwater Estate showing our home (Blue Home icon) & the NBC Nature Reserve

(Courtesy of Google Maps)

When we first arrived we could only see Noisy Miners as they then had the numbers then, and chased every other bird species out. They now (2023) are a smaller flock of about 12 (The Dirty Dozen) and share the reserve with regulars such as Magpies, Butcher Birds, Tawny Frogmouths and Crested Pigeons. Each of these species have their own favourite trees for nests & shade.

The Noisy Miners nest & breed in the reserve and, surprisingly, in the small trees fronting the main street (Kingfisher Way) in front of our home & the neighbours. These trees are about 4 m in height. Their success rate is very high, even in our front street trees. Usually 2 fledglings always survive, with continuous squawking whilst being fed by 2 - 3 other Noisy Miners (usually males of the flock), as the female only lays & incubates the eggs.

Noisy Miner chicks begging for food (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

Nesting time is when all the flock defences come out, including ganging up on other birds, animals such as dogs & cats, humans if they get too close to the nest, and dive bombing humans very close & clicking their beaks. I have not yet seen one wound on a human adult or child. They just go very close. If a Hawk or other predatory bird flies nearby, usually one or two will begin to harass it, and if that is not enough, then the whole flock is summoned to help. I have seen Hawks on several occasions been harassed by at least a dozen adults above the reserve.

With our other resident birds such as the Magpies and Butcher Birds, the Noisy Miners seem to accept them, and do not perform the massive and noisy flocking behaviours. Flocks are called Coalitions, for a good reason.

When we first arrived the flock size I would say was near the 20 mark, and now a constant 12 mark. The mortality of young fledglings is (I feel) quite high, due to motor traffic, nest falls, predation by pet cats, foxes and previously Python snakes. The Noisy Miners overcome this by nesting multiple times a year in a very comfortable local climate, even in winter.

The Wiki description calls Noisy Miners as gregarious & territorial: they forage, bathe, roost, breed & defend territory communally, by forming colonies. The Noisy Miner is an unusually vocal species having a large & varied repertoire of songs, calls, scoldings and alarms (most are loud and penetrating).

The female alone builds the nest (cup shaped & deep) from twigs, grasses, plant material, animal hair & spider webs. The clutch is usually 2 - 4 eggs.

Hatched Noisy Miner chick and unhatched egg (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

From hatchling to fledgling (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

With all the storm-trooping done by these birds, they tend to be disliked by a lot of people, including my wife Gerry. But I see in them a lot of positives, including:

- Communal support

- Protection of their territories

- Protection of their young

- Keep their nests clean by removing faeces, but shit on everything else on their flight paths

- Keep our home clean of spiders, especially the house

- Have a cheeky grin, and I believe, recognise regular contacts such as us home regulars

- Regular bathers

- Look at themselves in window reflections, especially as fledglings

- Are very calm around people they know

I always get great pleasure out of watching them have a bath in the bird baths. The bird bath on the east side of the house is in shade in the afternoon, and is very popular by the whole family. But during nesting and fledgling, the adult usually has to demonstrate to the young birds the bathing technique while they watch. Then it is their turn and one at a time they take their turns. Early attempts are mixed, but after a few minutes they get the hang of it, and before long the adult and the fledglings are into a mass bath (and having a great time). This performance is every year, and we watch it from our Alfresco.

Some more pics:

Fledgling hiding in tree (Courtesy Joe Mills)

Noisy Miner in local shade tree (Courtesy Joe Mills)

In the year from 2020 to 2021 283 Noisy Miners were rescued in this LGA and formed the bulk of the 315 honeyeaters rescued. Just 80 were released.

The noisy miner (Manorina melanocephala) is a bird in the honeyeater family, Meliphagidae, and is endemic to eastern and southeastern Australia. This miner is a grey bird, with a black head, orange-yellow beak and feet, a distinctive yellow patch behind the eye, and white tips on the tail feathers. Found in a broad arc from Far North Queensland through New South Wales and Victoria to Tasmania and south-eastern South Australia, the noisy miner primarily inhabits dry, open eucalypt forests that lack understory shrubs. These include forests dominated by spotted gum, box and ironbark, as well as in degraded woodland where the understory has been cleared, such as recently burned areas, farming and grazing areas, roadside reserves, and suburban parks and gardens with trees and grass, but without dense shrubbery. The density of noisy miner populations has significantly increased in many locations across its range, particularly in human-dominated habitats. The popularity of nectar-producing garden plants, such as the large-flowered grevilleas, was thought to play a role in its proliferation, but studies now show that the noisy miner has benefited primarily from landscaping practices that create open areas dominated by eucalypts.

Noisy miners are gregarious and territorial; they forage, bathe, roost, breed and defend territory communally, forming colonies that can contain several hundred birds. Each bird has an 'activity space', and birds with overlapping activity spaces form associations called 'coteries', which are the most stable units within the colony. The birds also form temporary flocks called 'coalitions' for specific activities, such as mobbing other birds.

Abundant throughout its significant range, the noisy miner is considered of least concern for conservation, and its extreme population densities in some areas actually constitute a threat to other species. The strong correlation between the presence of noisy miners and the absence of avian diversity has been well documented. Locally they have displaced the smaller wren species and birds such as the silver-eye, which was once far more abundant in our area.

The silvereye (Zosterops lateralis). Photo: Fir0002.

Another insectivorous little bird that was once prolific across Pittwater but is now found only in bush reserves is the Spotted Pardalote (Pardalotus punctatus). The Spotted Pardalote is a tiny bird that is most often high in a eucalypt canopy, so it is more often detected by its characteristic call. The wings, tail and head of the male are black and covered with small, distinct white spots. Males have a pale eyebrow, a yellow throat and a red rump. Females are similar but have less-distinct markings. The Spotted Pardalote uses a tunnel built in clay or soil that ends in a lined chamber, and may ignore the approach of birders. This one photographed this week seemed as curious about the birder as she was of him. Both parents share nest-building, incubation of the eggs and feeding of the young when they hatch.

The Spotted Pardalote forages on the foliage of trees for insects, especially psyllids, and sugary exudates from leaves and psyllids. The Spotted Pardalote remains relatively common in urban areas that have a high density of eucalypts.

Spotted Pardalote photographed at Ingleside in 2013. Photos: A J Guesdon.

The role played by the noisy miner in the steep decline of many woodland birds, its impact on endangered species with similar foraging requirements, and the level of leaf damage leading to die-back that accompanies the exclusion of insectivorous birds from remnant woodlands, means that any strategy to restore avian diversity will need to take account of the management of noisy miner populations.

Some habitat restoration and revegetation projects have inadvertently increased the problem of the noisy miner by establishing the open eucalypt habitat that they prefer. A focus of many regeneration projects has been the establishing of habitat corridors that connect patches of remnant forest, and the use of eucalypts as fast-growing nurse species. Both practices have sound ecological value, but allow the noisy miner to proliferate, so conservation efforts are being modified by planting a shrubby understory with the eucalypts, and avoiding the creation of narrow protrusions, corners or clumps of trees in vegetation corridors. A field study conducted in the Southern Highlands found that noisy miners tended to avoid areas dominated by wattles, species of which in the study area had bipinnate leaves. Hence the authors proposed that revegetation projects include at least 15% Acacia species with bipinnate leaves if possible, as well as shrubby understory plants.

Translocation of noisy miners is unlikely to be a solution to their overabundance in remnant habitats. In a Victorian study where birds were banded and relocated, colonies moved into the now unpopulated area, but soon returned to their original territories. The translocated birds did not settle in a new territory. They were not assimilated into resident populations of miners, but instead wandered up to 4.2 kilometres (2.6 mi) from the release point, moving through apparently suitable habitat occupied by other miners—at least for the first 50 days following translocation. Two birds with radio tracking devices travelled 18 kilometres (11 mi) back to their site of capture.