June 25 - July 15 2023: Issue 589

Ringtail Posse 5: June 2023

Lynleigh Greig OAM: Snakes, Dick Clarke: Diamond Python, Selena Griffith: Glossy Black-Cockatoo, Eric Gumley: Bandicoot

Definition from

Ringtail: from the 'Common Ringtail Possum' which is not so common anymore in urban areas. The Common Ringtail Possum is found along the entire eastern part of Australia and south west Western Australia. They are also found throughout Tasmania. The western ringtail possum is a threatened species under State and Commonwealth legislation. In Western Australia the species is listed as Critically Endangered fauna under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.+

Posse: noun. 1 : a large group often with a common interest 2 : a body of persons summoned by a sheriff to assist in preserving the public peace usually in an emergency 3 : a group of people temporarily organised to make a search (as for a lost child) 4 : one's attendants or associates.

On Wednesday June 21st 2023 a Motion regarding Heritage Protection was passed in the NSW Parliament. Tabled by The Hon. Peter Primrose, contributors to the discussion spoke of the Minns Government's commitment to developing the State's first heritage strategy, in which the Government will develop options to recognise and protect significant trees, urban bushland and wildlife corridors.

This was, of course, music to the ears of all who are working at ground level in these areas to safeguard the survival of the urban wallaby, koala, lizard, skink, snake, bandicoot, every bird of woodland, water and grassland, insects and every other wildlife species we share suburbia with.

In recent approved DA’s Council is listing as a requirement of consent in Assessment reports to look after the other residents of this area, the wildlife. On blocks where people wish to remove large amounts of trees that are clearly homes for local fauna a wildlife expert must assess these prior to any removal taking place, nesting boxes are required to be installed afterward and Ecologists must be on site during their removal.

Recent examples and instances are:

Bandicoot/Penguin (Avalon)

Long-nosed Bandicoots & Little Penguins – Best Practices for Residents

Residents are encouraged to follow a number of Best Practices to assist with the protection and management of the endangered populations of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins:

Long-nosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other native animals should never be fed as it may cause them nutritional problems, hardship if supplementary feeding is stopped, and it may increase predation.

Feral cats or foxes should never be fed or food left out where they can access it, such as rubbish bins without lids or pet food bowls, as these animals present a significant threat to Longnosed Bandicoots, Little Penguins and other wildlife.

The use of insecticides, fertilisers, poisons and/or baits should be avoided on the property.

Garden insects will be kept in low numbers if Long-nosed Bandicoots are present.

When the North Head Long-nosed Bandicoot Recovery Plan is released it should be implemented where relevant.

Dead Long-nosed Bandicoots or Little Penguins should be reported by phoning Manly Council on 9976 1500 or Department of Environment and Conservation on 9960 6266.

Please drive carefully as vehicle related injuries and deaths of Long-nosed Bandicoots and Little Penguins have occurred in the area. Care should also be taken at night in the drive way when moving cars as bandicoots will seek shelter beneath vehicles.

Cat/s and or dog/s that currently live on the property should be kept indoors at night to avoid disturbance/death of native animals. Ideally, when the current cat/s and/or dog/s that live on the property no longer reside on the property it is recommended that they not be replaced by new dogs or cats.

Report all sightings of feral rabbits, feral or stray cats and/or foxes to N B Council.

And;

Protection of Habitat Features

All natural landscape features, including any rock outcrops, native vegetation and/or watercourses, are to remain undisturbed during the construction works, except where affected by necessary works detailed on approved plans.

Reason: To protect wildlife habitat.

The Reason given in all instances is: To protect native wildlife.

This follows on from the 2022 Local Government NSW Conference where a Motion was passed - That Local Government NSW lobby the NSW Government to:

- In conjunction with industry associations, introduce enforceable standards for the preparation of flora and fauna management plans.

- Consider Codes of Practice and Guidelines for handling native wildlife and other best practice and animal welfare laws in development of the standards.

- Consult with Councils, National Parks and Wildlife Service, Ecological Consultants Association of NSW, wildlife rescue organisations and other relevant agencies in the preparation of standards.

Such a standard should include requirements for:

- Pre-clearance surveys to be carried out to establish which species are present on the site, including identification of any threatened and native species.

- The identification of suitable nearby areas where wildlife could possibly be relocated.

- The provision of possum, glider and bat boxes sufficiently in advance of vegetation clearing to allow wildlife time to discover the boxes and become familiar with them.

- Compliance with the NSW Code of Practice for Injured, Sick and Orphaned Protected Fauna and the licencing requirements contained in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

- Best practice for wildlife handling and care (including contact with local wildlife rescue groups).

- Reporting of injured or killed fauna to the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment to enable the data to be used in statewide biodiversity monitoring programs.

The premise of this is that mandatory pre-clearance surveys to establish what wildlife lives there before works commence, and to document this in a formal way, should be required on any site that has vegetation and for which a DA has been approved. The experience is that often vegetation is removed before an application is submitted, often leaving wildlife with no home. Wildlife then ends up on roads dead or dies after being displaced/evicted.

One wildlife carer cited a recent Pittwater case of a powerful owl pair site that had had vegetation removed to make the development more likely to proceed – the nest and two babies were destroyed.

‘It’s hard to prove wildlife is/was present after the clearing as they aren’t there.’

‘Once trees and vegetation are removed the problem is where do these animals go?’

Powerful Owls are also not so common anymore in urban areas.

However it's clear human residents of this LGA have a deep and abiding love for and connection to these other furry, scaled, finned and feathered locals. We listen for them during the night, happy when we hear their footsteps scampering across our rooves and fences or their soft hoots across the valleys.

We look out for them during the day, delighted with their presence.

Residents here are distressed when they find injured wildlife or witness wildlife being attacked. They are not in denial that all our local wildlife feels and thinks - they cry when their babies are killed in front of them, mourn the loss of a mate - people who have heard or seen this never forget.

Data kept by the NSW Environment Department, although only listing incidents from June 2013 to June 30 2021, shows that 33,391 wildlife animals have been rescued in our area between June 2013 and June 30 2021 and just 8, 812 released again. Of these 42 were threatened species.

Data to 30 June 2021 lists of the 5, 235 animals rescued during that 2020 to 2021 period just 1,573 were released. Across NSW during that same year a total 120, 927 animals were rescued and just 28, 805 released - 5, 122 of these were were threatened species (104 kinds) of which just 1,180 were released.

These figures and data do not take into account all the wildlife found deceased beside or on roads or elsewhere.

''This study draws on 469,553 rescues reported over six years by wildlife rehabilitators for 688 species of bird, reptile, and mammal from New South Wales, Australia.... Of the 364,461 rescues for which the fate of an animal was known, 92% fell within two categories: ‘dead’, ‘died or euthanised’ (54.8% of rescues with known fate) and animals that recovered and were subsequently released (37.1% of rescues with known fate).''In total, there were 872,087 records reported during the six-year (2013–14 to 2018–19) study period. Just over 97% of these came from three animal groups–birds, mammals, and reptiles. Of the total number of records, 402,534, (46%) were excluded from the descriptive analysis because they: a) did not contain any information about the animal, or the animal’s identification was ambiguous and could not be placed within a group (e.g. an ‘unidentified animal’); b) contained only sightings of animals and were not attended to in some way by a wildlife rehabilitator; c) were records of amphibians (373 records) or non-vertebrate fauna (e.g. spiders, insects, etc.); d) were non-avian marine vertebrates such as whales, seals, sharks, rays, fish etc; e) were reported as floating, drowned, or washed up animals (deemed an ambiguous cause for rescue, n = 48); f) contained both an ‘unknown’ cause for rescue and an ‘unknown’ fate; or f) were an introduced or spurious species (e.g. extinct, or out of known range). These exclusions resulted in a dataset for descriptive analysis of 469,553 records i.e. 54% of the initially reported amount.''

Many people state we are the generation witnessing the extinction of urban wildlife. There has been generation after generation of humans living alongside and with wildlife, until this one.

It's not just the Pittwater koalas that have gone, other species, like the ringtail possum or long-nosed bandicoot are disappearing, along with their joyful snuffles and squeaks, from our urban backyards and the trees that tower over them.

There is a growing silence at night for those species that forage for food then - possums, wallabies, owls. The same is occurring for those that are active during daylight.

Although many point to the impacts of cat and dog attacks due to irresponsible owners, there is also what is termed the 'inconvenient possum' in a roof or garden shed, because its home tree has been cut down. These are caught by those hired, some of whom have little knowledge or scruples, and release them into areas out of their home range - a death sentence for that possum as this species is territorial, along with requiring certain food trees in order to eat, to survive.

There is predation by other introduced species - readers regularly send in photos and videos of foxes roaming and killing at night.

There are roadkill black spots, places where wallabies or turtles or possums used to cross the area where a road has been cut through and a speed limit that means death for wildlife. There are no 'speed humps' in place, and no plan at a local, state or federal government level to install these. Residents and wildlife rescuers have reported some drivers 'aiming straight for' a stricken animal.

There is the razing of blocks of land for development prior to any required assessment of the environment taking place to circumvent those requirements so a report can state 'nothing present'. There is nothing present because its habitat has been cleared or the wildlife killed by these actions.

Our local wildlife carers are exhausted, state there have been so many, too many so far this year - they are increasingly heartbroken with all the babies they lose, they cry every day, and then pick themselves up and get on with trying to save the next critter, and the next.

Wildlife carers are all volunteers - they do the rescues, sometimes horrific rescues, run to and fro from the great local vets who help out trying to save them, they gather or pay for the food, for the milk, for the petrol, for the electricity to keep bubs warm. There are no grants or funding for Australia's wildlife carers - they have to raise funds through running events, raising awareness, collecting cans for a 10 cent return.

This year a celebration of residents' favourite wildlife runs as Profiles across 2023 - simply to allow those who love a chosen 'critter' to speak for them a little, to remind us of what is here and what we feel connected to has feelings too.

Information about these species and how many or why we are losing them is included - just so we can think about how we, as individuals and as one community, can turn around that growing silent emptiness closing in around us and these other ones we love.

Ultimately the founders of the Ringtail Posse are hoping everyone chooses to become a Member of the Ringtail Posse and keep their other loved one safer in its one and only home.

Reason?: To Protect Local Wildlife so it becomes 'common' and safer for our wildlife to be everywhere once more.

To join in please email us with 'Ringtail Posse' in the subject line - with so many local species of wildlife, vital insects and seals flopping around on the sand or penguins flitting through the seas, there are several on the lists that haven't been claimed for guardianship yet - what's yours?

Round 5 of Ringtail Posse Profiles includes the following now officially joined Members:

Lynleigh Greig OAM - Sydney Wildlife Rescuer/Carer, 2022 OAM 'For Service To Wildlife Conservation', Pittwater Woman Of The Year 2021: Snakes

When was the last time you had an interaction with a beautiful wild animal? I mean something epic like staring into the yellow eyes of a powerful owl in your backyard gum tree... Or watching a tiny feathertail glider licking a banksia flower under the moonlight… Or having the exhilarating experience of watching a python ingesting a rat in your outdoor shed…!

Are you noticing that these kinds of epic wildlife interactions are diminishing…?

Many of you probably already know that snakes are - by far - my favourite species! So it will come as no surprise when I complain about the fact that there are just not enough sightings of snakes in my yard or in my suburb! Gone are the days when snakes were “ everywhere" and you had to step over them to get from your front door to your car…! All of last summer the ONLY snake I saw in my yard was a golden-crowned snake. And it happened to be dead. Covered in tell-tale bites from a neighbouring pet left to roam at night and prey on our nocturnal animals :(

Why do I love snakes so much - and why should you join me in my adoration?

- Snakes are quiet and clean, they mind their own business and they perform a free pest extermination service!

- Snakes don’t dig up the veggie garden or eat the roses and they certainly don’t wake you at 5am with loud noises!

- Snakes don’t need anything in exchange for their rat-ridding services, except the chance to be left to live in peace.

- Snakes do not wish to have any interaction with humans. At all. Ever. They choose to flee from us rather than have a confrontation of any kind.

- Snakes are beautiful and fascinating and entirely awe-inspiring in every way.

If I had to play favourites, I would have to say red-bellied black snakes are the ones that have my heart. Followed by death adders and then tree snakes. Pythons are also pretty special - so languid and lazy and loaded with character.

So, if you see a snake, don’t shriek or panic. Stand quietly and appreciate the work they do to keep the ecosystem in balance.

And remember - without snakes, we would be overrun with pests that can potentially carry harmful diseases.

So thank a snake today :)

I would, if I could find one…

Young brown tree snake (Boiga irregulris) Photo by Jack Fegan

Diamond python (Morelia spilota spilota) Photo by Lynleigh Greig

Kayleigh and Lynleigh Greig, Sydney Wildlife Rescuers

Eric Gumley - Builder, Principal Sponsor Of Pittwater Online News, Grandfather, Lover Of All Local Wildlife: Bandicoot

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

Bandicoots.

Why do you like Bandicoots?

I just find them incredibly cute and gregarious animals – I love the sounds they make when talking to each other while foraging as a family unit. I also like that they help in my garden by turning over mulch and ‘aerating’ the lawn.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

Decades – although not for around 2 years lately.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

We used to have a family of bandicoots living in our yard. During the past 2 years they have completely disappeared. This started around 7 years ago when I found one dead in our yard, obviously mauled by a cat. Although I buried it before the wife could see she soon remarked that she could not hear that particular one among the mob that owned our yard after dark.

Soon after I found another one dead - mauled again - and then another on the verge of the road, probably trying to cross Barrenjoey Road at dusk or dawn.

I have, in fact, caught a cat in our yard just before dawn on several mornings since; a hungry looking lean one that may even be a wild cat. I am also aware that a pair of foxes hunts in our area, and have seen them crossing the road into the Careel Bay playing fields, where they would be hunting nesting birds or feral rabbits people have had – escaped pets.

As a new grandfather it distresses me that my grandson may not get to hear or see these wonderful local species in the suburbs because people let their cats out at night. Please keep your cats in between dusk and dawn and look after our local wildlife. If you see any foxes, please report them to Council so they can get rid of them. And please keep your dogs away from our local wildlife and where they live - our pup is not allowed near wildlife and even gets told off for 'yelling (barking) at the birds' that live here too - although I've caught the birds yelling back at her on occasion.

There were 94 Bandicoots (long-nosed: 64 - unidentified: 29) rescued during the 2020 to 2021 period and just 34 released, so 60, at least, lost their lives - 'unsuitable environment' is listed as the main cause for rescues, along with dog and cat attacks on this species - with dog attacks more frequent than cats. Wildlife rescuers and carers who find lactating mothers often then spend days searching for where the nest may be as there are babies to be rescued and fed as well - they are not often successful.

The data, dating from June 2013 and all that is officially available, records 409 bandicoots have been rescued in the 8 years of collecting the same and just 152 released. Overall collision with motor vehicles is listed as the big killer of rescued bandicoots and cat attacks on the same overtop the more recent upsurge of dog attacks on the bandicoot. Once again, this does not take into account all the manuy other bandicoots that are found deceased beside our roads or mauled in our urban yards.

Residents would know we are losing out local bandicoots - in a call out for information on if people had heard them going into the rounds of the Ringtail Posse answers from Balgowlah to Manly and all points north stated they had not heard them for a while. The family of bandicoots in the Pittwater Online yard that once thrived here has also not been heard for at least 2 years, although cats have been chased from the yard, hunting after dark, every night since.

Along with the long-nosed bandicoot this LGA was once home to the Southern Brown Bandicoot, however their population has been reduced to a critical level. We are most definitely losing or have lost the bulk of our bandicoots. As Tom states above - we need to drive so we don't kill our local wildlife and keep cats indoors at night and dogs away from where wildlife lives.

The NSW Department of Environment states the northern beaches from Manly to Palm Beach are one of the last strongholds for long-nosed bandicoots in the Sydney region. There are 2 significant populations: at Pittwater, and on the coast near Newport. Because it is cut off from other bandicoot populations by houses, a population of long-nosed bandicoots at North Head in Sydney Harbour National Park at Manly has been listed as endangered and was one of the first endangered population listings in New South Wales.

The Long-nosed bandicoot (Perameles nasuta) is around 31–43 cm in size and weighs up to 1.5 kg. It has pointed ears, a short tail, grey-brown fur, a white underbelly and a long snout. Its coat is bristly and rough. Gestation lasts 12.5 days, one of the shortest known of mammal species. The young spend another 50 to 54 days in the mother's pouch before being weaned.

The long-nosed bandicoot is a common prey item of the introduced red fox. and why residents are urged to report these when they see them. Report where and when at: https://www.feralscan.org.au/foxscan/default.aspx

Although the Dept. of Environment states this species is the most common species of bandicoot in the Sydney area, locals not hearing them anymore would point out they are not so common anymore.

Long-nosed Bandicoots are known to dig small, conical holes in lawns and gardens. Whilst bandicoot diggings can be unsightly, bandicoots are often helping the home gardener control grubs and garden pests. They eat insects, earthworms, insect larvae and spiders (including the venomous funnel-web spider) as well as tubers and fungi. Bandicoots are often attracted to forage on watered lawns and gardens where insect numbers are higher than in bushland, and these areas can sustain higher numbers of bandicoots.

Long-nosed Bandicoot, northern beaches, New South Wales. Photo: JJ Harrison

The Southern brown bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus) is listed as endangered in NSW. It is around 28–36 cm in size and weighs up to 1.5 kg. It has small, rounded ears, a longish, conical snout, a short, tapered tail and a yellow-brown or dark grey coat with a cream-white underbelly. They are smaller and shyer than other species and do not stray far from their preferred shelter of dense heath vegetation.

The southern brown bandicoot is patchily distributed and occurs south from the Hawkesbury River to the Victorian border and east of the Great Dividing Range.

There are 2 main populations; one lives in Garigal and Ku-ring-gai Chase national parks in northern Sydney - yet more reason to keep pets out of these places. The other lives around Ben Boyd National Park and Nadgee Nature Reserve in the far south-eastern corner of the state.

Southern brown bandicoots are nocturnal and omnivorous, feeding on insects, spiders, worms, plant roots, ferns, and fungi. Gestation lasts less than fifteen days and typically results in the birth of two or three young.

The young weigh just 350 mg (5.4 gr) at birth, remain in the pouch for about the first 53 days of life, and are fully weaned at around 60 days. Growth and maturation is relatively rapid among marsupials, with females becoming sexually mature at four to five months of age, and males at six or seven months. Lifespan in the wild is probably no more than four years.

Populations have declined markedly and become much more fragmented in the time since European expansion on the Australian mainland, much of that due to the clearing of habitat. In many areas of its range the species is threatened locally, while it may be common where rainfall is high enough and vegetation cover is thick enough. Apart from habitat fragmentation, the species is under pressure from introduced predators such as the red fox and feral cats. It has been reintroduced to some lower rainfall areas where there is protection against cat and fox predation – one such site being Wadderin Sanctuary in the eastern wheatbelt of Western Australia, 300 km east of Perth.

In national assessment, the southern brown bandicoot is currently regarded as Endangered on the mainland as a whole, and Vulnerable in South Australia.

Juvenile southern brown bandicoot. Photo; Bertram Lobert

Bandicoots have at least 4 distinct vocalisations:

- a high-pitched, bird-like noise used to locate one another

- when irritated, they will make a 'whuff, whuff' noise

- when feeling threatened or alarmed, they will make a loud 'chuff, chuff' noise and loud whistling squeak at the same time

- when in pain or experiencing fear, they will make a loud shriek.

Activities to assist this species:

- Prevent domestic cats and dogs from roaming into habitat areas.

- Protect all known and potential habitat and include linkages across the broader landscape.

- Undertake fox, feral dog and feral cat control programs.

- Apply fire regimes that maintain patches of dense ground cover and floristic and structural diversity in the habitat.

Selena Griffith - CEO, Academic, Mother, Design Thinker, Innovator, Entrepreneur, Gardener Of All Things: Glossy Black Cockatoo

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

Oh so many - but for this Glossy Black Cockatoo.

Why do you like the Glossy Black Cockatoo?

I do a lot of walking around West Head in Ku-ring-gai National Park and almost always see Glossy Black Cockatoos munching away on casuarina seed pods. I love the cracking sound. You hear it then know to look for them. They are so big yet so hard to see and their striking feathers! I also love their call. I love seeing them in family groups / small flocks. They have a very unusual shape in the sky.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

I used to see black cockatoos regularly, then started to see glossy black cockatoos over the past few years in greater numbers. Every time I see them it feels special.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

Yes, since the 2019/2020 bush fires there seems to be more here.

Glossy black cockatoo above Towler's Bay, June 2023. Photo: Selena Griffith

Glossy black cockatoo above Towler's Bay, June 2023. Photo: Selena Griffith

There have been 3, 819 parrots rescued across this LGA according to the 2013 to 2021 data made available, or just over 477 a year during this 8 year data period, and 823 released, meaning we have lost just over 8 parrots every single day during the 8 year data period available. Across the whole of NSW 83, 124 have been rescued and after those that were released are deducted we are losing 177 each day.

The data states 297 yellow-tailed cockatoos have been rescued across the whole of NSW throughout the 2013 to June 2021 period and just 38 released. Glossy Black-cockatoo rescues are listed as 50 and 4 released, the bulk of these in the 2019/20 and 2020/21 years, with none of those rescued during 2019/20 surviving - 32 of these deaths are listed as being attributed to 'unknown'. The data also lists 61 Red-tailed Black-cockatoos (inland sub species) with just 5 released, and 42 deaths again listed as 'unknown', and a further 30 'unidentified' black-cockatoos and just 7 released. A further 2 'coastal' subspecies of red-tailed black-cockatoo were rescued but did not survive in the 2019/20 period, or 127 of these already rare birds lost.

Glossy Black-Cockatoos occur from eastern Victoria to south-eastern Queensland; 38% of this range was burnt by the 2019-2020 bushfires. The fires also damaged old, hollow-bearing trees, the breeding sites for Glossies. Without appropriate breeding sites, their population will continue to decline.

The Glossy Black-cockatoo is listed as vulnerable in Queensland, New South Wales, endangered in South Australia and critically endangered in Victoria.

In 2019 to better understand the range of Glossy Black-Cockatoos in eastern Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute (ARI) researchers surveyed their known habitat for the presence of this species. To do this, they searched stands of Black She-oak for eaten cones. These surveys provided a critical baseline to later assess the impact of the Black Summer bushfires. After the fires, the same sites were surveyed again for evidence of Glossy Black-Cockatoo feeding. The survivorship of Black She-oak and the overall availability of cones – a critical food resource – were also assessed. Key findings include:

- Before the fires, signs of feeding were recorded at 37.8% of sites.

- Shortly after the fires (2-3 months) feeding was recorded at 38% of unburnt sites, but only 4.8% of burnt sites.

- On a follow up visit nearly 2 years after the fires, feeding sign was still low in burnt areas (4.8% of sites) but, concerningly, feeding signs in unburnt areas had drastically declined to 14% of sites.

Once numbering in the tens of thousands, fewer than 8,000 remain in the wild across the whole country, according to BirdLife Australia. An April 2023 ABC Report states Farmers in the New South Wales central west are trying to save this native bird from extinction.

''The birds' numbers are in decline because its natural habitat is disappearing.'' the report states

Fragmentation of what habitat remained across NSW after the 2019/20 fires, or no food trees next to nesting trees is accelerating the decline of these beautiful birds.

In an effort to protect the species, a group of farmers have planted more than 1,000 she-oaks and will soon install 45 nest boxes.

A study by the Australian World Wildlife Fund found more than half of the forests and woodlands in New South Wales have been lost since 1750.

David Watson, a professor of ecology at Charles Sturt University, has seen first-hand the impact tree planting can have on his 12-acre property near Albury.

"We have planted about 4,000 trees to bring it back from sheep country to the woodland it used to be," Dr Watson said. "Then one day there it was sitting in a tree next to the kitchen window, a glossy black-cockatoo in a tree that we had planted.

Dr Watson said this habit destruction had put the glossy black-cockatoo, and other bird species, on a path towards extinction.

"Extinction isn't just some distant idea that might happen in the far, far future that their grandkids might need to worry about. It is happening now."

The Glossy black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami) is a specialist eater and feeds on she-oaks, which is why we will see them in Pittwater and why we need to stop cutting down their food trees. Glossy Black-Cockatoos are strongly associated with she-oak trees (Allocasuarina and Casuarina), their primary food source. She-oaks are native, evergreen trees with long, needle-like foliage. Seeds are contained in woody cones (about the size of an olive but with a rough texture), and Glossy Black-Cockatoos extract them with their large and bulbous bills.

The glossy black-cockatoo is around 46 to 50 centimetres long and is generally smaller than other black-cockatoos. It is a brownish black colour and has a small crest.

There are some distinct differences in appearance between male and female birds. The male can be identified by the browner colour on the head and underparts and by bright red panels in the black tail. The female has a wider tail which is red to reddish-yellow, barred with black. Each female Glossy Black-Cockatoo (‘Flossy’) has a unique arrangement of yellow facial feathers, which, along with tail panels, help researchers identify individual birds.

That's right - humans aren't the only species with individual looks and personality traits.

Dick Clarke - Principal Of Envirotecture, Accredited Building Designer Focusing Exclusively On Ecologically Sustainable & Culturally Appropriate Buildings, As Well As Sustainable Design In Vehicles & Vessels, Multi Design Awardee: Diamond Python

What is your favourite local wildlife species?

Diamond Python by a small margin.

Why do you like the Diamond Python?

They are undeniably living artworks, both in patternation and movement. They are also very cuddly.

How long have seen or heard this animal?

Always at Elanora - and still do, very encouraging.

Have you noticed any changes in the number of these animals in your local neighbourhood?

Comes and goes with the wetness - dryness of the season, but numbers seem to be fairly stable.

The Data to 30 June 2021 lists 1,115 Diamond and Carpet pythons have been rescued across the Northern Beaches LGA and 431 released.

Collision with motor vehicles is listed as the primary reason for rescues, with 'unsuitable environment' listed second. Pythons like sunbaking on warm roads and some residents prefer they be moved along when found in their yard - sometimes for their own safety as cats attacking these is the third reason for rescues, treatments and deaths.

Dog attacks account for just 4 python casualties listed in the '50% excluded' data and 98 overall attacks on reptiles. Easter Blue-tongue and Easter Water dragons and the Ringtail Possum account for the bulk of species impacted by dog attacks, the data stating of the 315 animals rescued, from 34 species of which two were listed as threatened, 86 were released.

Diamond Pythons (Morelia spilota spilota) are close relatives to the Carpet Python and are black with cream and yellow patterns. They can be mostly black with a few spots or bright yellow with a few black edges. They can grow up to three metres long but are generally around 2 metres in length.

They are found all along the New South Wales coastline down into the north-eastern corner of Victoria. They are frequently spotted in Sydney suburbs that border on bushland. But like all pythons, these snakes are non-venomous.

They become most active in November, looking for mates and laying eggs. The male Diamond Python will travel up to 500m a day, following a scent trail left by a female when she is ready to find a mate. Numerous males can sometimes follow the trail of the same female.

The female Diamond Python lays eggs and coils around them to protect them and keep them warm. This maternal care, which is uncommon in snakes, ceases once the offspring hatch.

Male Diamond Pythons have a big home range of around 45 hectares and females have a range of around 20 hectares. They are always on the move and won’t stay in one place indefinitely. They live up to around 20 years so if you spot a Diamond Python more than once, even if it was years apart, it could be the same one.

A Diamond Python in your roof will not cause any damage but will help control rats.

The Diamond Python is not as widespread in Sydney as it once was and, although it is not considered endangered, it is under pressure from habitat destruction. - from/by Australian Museum

Diamond python (Morelia spilota spilota) Photo by Lynleigh Greig

Ringtail Posse Rounds 2023

- Ringtail Posse 1: February 2023 - Anna Maria Monticelli: King Parrots/Water Dragons, Jacqui Scruby: Loggerhead Turtle, Lyn Millett OAM: Flying-Foxes, Kevin Murray: Our Backyard Frogs, Miranda Korzy: Brushtail Possums

- Ringtail Posse 2: March 2023 - Kevin Murray: Tawny Frogmouth - Kayleigh Greig: Red-Bellied Black Snake - Bec Woods: Australian Water Dragon - Margaret Woods: Owlet-Nightjar - Hilary Green: Butcher Bird - Susan Sorensen: Wallaby

- Ringtail Posse 3: April 2023 - Jeffrey Quinn: Kookaburra, Tom Borg McGee: Kookaburra, Stephanie Galloway-Brown: Bandicoot, Joe Mills: Noisy Miner

- Ringtail Posse 4: May 2023 - Andrew Gregory: Powerful Owl, Marita Macrae: Pale-Lipped Or Gully Shadeskink, Jools Farrell: Whales & Seals, Nicole Romain: Yellow-Tailed Black Cockatoo

97% of Australians want more action to stop extinctions and 72% want extra spending on the environment

Most Australians (97%) want more action to protect nature, even if they don’t know the full extent of the biodiversity crisis. That’s the startling finding emerging from our first national survey of 4,000 voters.

Biodiversity matters. We rely on nature for healthy food, clean air and water. Roughly half of the global economy depends on natural systems. But Australia is losing biodiversity at a cracking pace. Over the past 200 years, a species has become extinct every second year on average. This includes one in ten of Australia’s mammal species. Thousands of species that were once common and widespread are now rare.

Halting and reversing species loss requires the support of the whole community. So we wanted to find out what Australians think about these issues and the potential solutions.

We found most of the community strongly supports pro-nature policies, such as ending logging of native forests and requiring businesses to report their impacts on nature. We hope the results in our Biodiversity Council report released today will galvanise support for greater conservation action.

Understanding The Biodiversity Crisis

Biodiversity refers to the richness and diversity of plants, animals and other living things in nature. Australia has one of the most unique and diverse natural environments in the world.

However, the state of the Australian environment is declining. The effects of climate change, land clearing, invasive species, pollution and more are causing irreparable damage.

The pace of loss and its consequences are even greater than previously thought. For example, biodiversity loss reduces the availability of clean water and air, and may limit future discoveries of potential treatments for many diseases and health problems. The loss of wild pollinators threatens the production of food crops globally.

This has led the World Economic Forum to declare biodiversity loss as the third most severe threat humanity will face in the next ten years.

As with climate action, the involvement and support of the wider community is essential to tackling the issue and requires people to take personal action. We also need people to back policies that protect and restore biodiversity.

Australians Want Action

In late 2022, we conducted an online survey of more than 4,000 people across Australia. We had a representative sample across age, gender and location, benchmarked against Australian census data. We asked people about their attitudes to nature, how much they participated in “pro-biodiversity” behaviours such as native gardening and sustainable consumption, and how concerned they were about biodiversity loss.

We also explored people’s opinions about the state of the environment, government performance and relevant policies.

Many people were not aware of the full extent of biodiversity loss, with 60% believing that the state of the Australian environment is “good” or “very good”.

Yet the vast majority of people still cared deeply for Australia’s environment. More than eight out of ten people were concerned about biodiversity issues (85%) and said it was important that nature in Australia is looked after (83%). As many as six out of ten (63%) people were “very” or “extremely” concerned.

Encouragingly, almost everyone (97%) wanted more action to conserve biodiversity. More than half wanted “a lot” or “a great deal” more action (58%). This shows that even when awareness is limited, people value nature and recognise the importance of protecting our natural environment.

Most people agreed everyone in Australia has a role to play (68%). More than half already engaged in actions to protect nature, such as being a sustainable consumer and managing pets or gardens for nature.

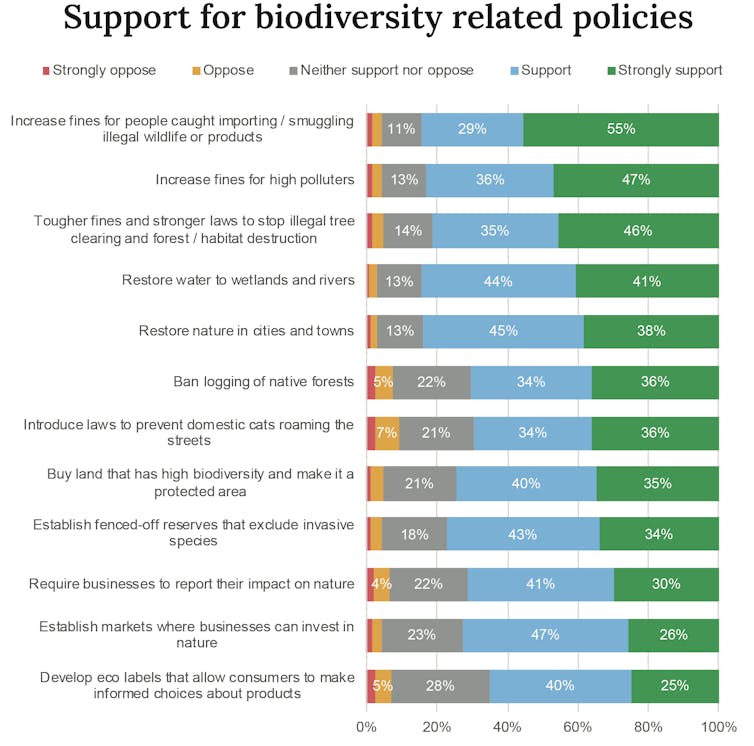

What About Policy Solutions?

Most of our survey respondents also believe all levels of government are responsible for taking action. Around three-quarters (72%) said more money should be spent on the environment. Only about one in 20 (6%) said less should be spent.

Most Australians were supportive of introducing new policies that could help protect biodiversity. The vast majority of people (80% or higher) support or strongly support:

- restoring water to wetlands and rivers

- increasing fines for people caught smuggling illegal wildlife or products

- restoring nature in cities and towns

- increasing fines for high polluters

- tougher fines and stronger laws to stop illegal habitat destruction and tree clearing.

More than 70% of people also support:

- banning logging in native forests

- introducing laws to prevent domestic cats roaming the streets

- requiring businesses to report their impact on nature

- establishing new protected areas (such as national parks) at places with high biodiversity.

A majority of Australians from all states and territories, political alignments, and regions, and from urban and rural areas supported these policies.

Significantly, very few people opposed these policies (between 3% and 9% across the suite of policy options). The remainder neither supported nor opposed policy action.

This means stronger laws and policies to protect and restore the environment are far less contested among Australians than is often depicted in the media and political debates.

What Now?

Policymakers should see our survey results as a green light to take stronger action for nature. Now is the time to start strengthening environmental laws, ceasing native forest logging, and increasing investment in biodiversity protection and restoration.

Around seven in ten Australians in our survey also indicated that nature conservation issues could influence their vote in future elections.

Politicians should take note. Self-identified swinging voters are significantly more concerned than non-swing voters (for example, 73% are “very” or “extremely” concerned about extinction compared with 66% of non-swing voters). They also believe more action is needed (63% believe “a lot” or “a great deal” more action is needed compared with 57% of non-swing voters), and state they are more likely to vote accordingly (80% of swing voters would be influenced by nature conservation in their Federal election votes compared with 73% of non-swing voters).

Australia has a lot to gain from engaging everyone in nature conservation and restoration, and much to lose if we fail.![]()

Liam Smith, Director, BehaviourWorks, Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Monash University; Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Kim Borg, Research Fellow at BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Monash University, and Rachel Morgain, Senior Research Fellow, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.