Can you see three trees from your home, school or workplace? Is there tree canopy cover shading at least 30% of the surrounding neighbourhood? Can you find a park within 300 metres of the building?

These three simple questions form the basis of the “3+30+300 rule” for greener, healthier, more heat tolerant cities. This simple measure, originally devised in Europe and now gaining traction around the world, sets the minimum standard required to experience the health benefits of nature in cities.

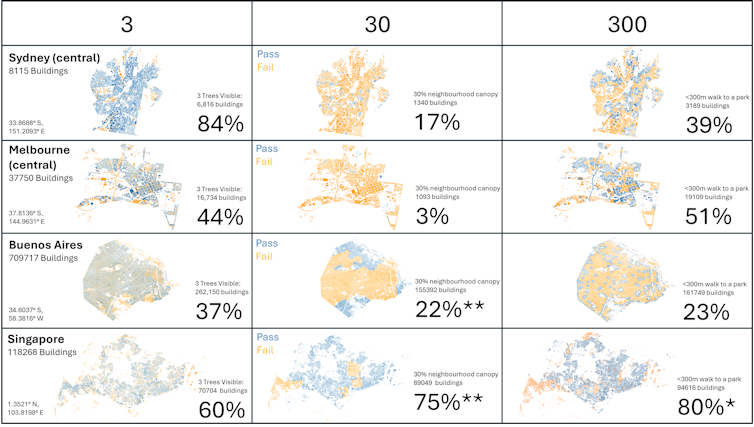

We put the rule to the test in eight global cities: Melbourne, Sydney, New York, Denver, Seattle, Buenos Aires, Amsterdam and Singapore.

Most buildings in these cities failed to meet the 3+30+300 rule. We found canopy cover in desperately short supply, even in some of the most affluent, iconic cities on the planet. Better canopy cover is urgently needed to cool our cities in the face of climate change.

Explore all three interactive maps, zoom in or out and search by address or place, hit the “i” button for more detail. Source: Cobra Groeninzicht

Shady trees are good for health and wellbeing

People are more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, obesity and heatstroke in places with fewer trees, or limited access to parks. But how much “green infrastructure” do we need to stay healthy and happy?

Dutch urban forestry expert Professor Cecil Konijnendijk set the standard when he introduced the 3+30+300 rule in 2022. This benchmark is based on his wide-ranging review of the evidence linking urban nature to human health and wellbeing.

While the rule is still relatively new to Australia, it is gaining momentum internationally. Cities in Europe, the United States and Canada are using the measure, formally or informally, in their urban forestry strategies and plans. These cities include Haarlem in the Netherlands, Malmö in Sweden, Saanich in Canada, and Zürich in Switzerland.

Putting the rule to the test

We applied the 3+30+300 rule to a global inventory of city trees that collates open source data from local governments. We selected cities with the most detailed data for our research, aiming for at least one city on every continent. Unfortunately no suitable data could be identified for cities in Africa, mainland Asia or the Middle East.

Our final selection of eight cities features several regarded as leaders in urban forestry and green space development. The City of Melbourne is renowned for its ambitious Urban Forest Strategy. New York is home to successful projects such as MillionTreesNYC and The Highline. Singapore is known for lush tropical greenery including standout sites such as Gardens by the Bay and Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park.

Analysis of Melbourne and Sydney was restricted to central areas only, based on limitations in the data, while the other six analyses covered whole cities.

Most buildings across the eight cities met the three trees requirement but fell short on canopy cover. In contrast, three in four (75%) buildings passed the 30% canopy benchmark in Singapore and almost one in two (45%) passed in Seattle.

Just 3% of buildings in Melbourne had adequate neighbourhood canopy cover, despite 44% having views of at least three trees.

Central Sydney fared better, although only 17% of city buildings were shaded enough despite 84% having views of at least three trees.

Access to parks was also patchy. Cities such as Singapore and Amsterdam scored well on parks, while Buenos Aires and New York City scored poorly.

Since completing this study, we partnered with Dutch geospatial firm, Cobra Groeninzicht to map ten extra cities in Europe, the US and Canada. We found similar results in these cities.

Too small and spaced out

We were surprised to discover so many buildings around the world had views to at least three trees but still had inadequate neighbourhood canopy cover. This seemed contradictory – are there enough trees, or not?

The issue comes up in other studies too. For example, the city of Nice in France recently revealed 92% of residents have views to three trees, but only 45% had adequate neighbourhood canopy.

When we looked into this issue, we found those three trees, visible as they may be, are often too small to create decent shade.

Planting density was an issue too. When a city did have large trees, they tended to be very spaced out.

Meeting the 3+30+300 rule therefore requires bigger, healthier longer-lived trees, planted closer together.

Explore all three interactive maps, zoom in or out and search by address or place, hit the “i” button for more detail. Source: Cobra Groeninzicht

City living is tough for trees

Many of our roads and footpaths sit on a base of compacted crushed rock, topped by impermeable asphalt or paving. This means very little water reaches tree roots, and there isn’t much space for the roots to grow. As a result, street trees grow slowly, die young, and are more susceptible to pests, disease and heat stress.

Above ground, trees face further challenges. Power companies have legal powers to demand sometimes excessive amounts of pruning. Residents and developers frequently request tree removals, often successfully.

This trifecta of high removal rates, heavy pruning and tough growing conditions mean large, healthy canopy trees are rare.

Planting new trees is surprisingly difficult too. Engineering standards often act against tree planting by requiring large clearances from driveways, underground pipes, or even parking spaces.

Instead of managing potential conflicts, trees are often simply deleted from streetscape plans. Sparse planting is the result.

Finding solutions to nurture tree canopy

Fortunately, there are solutions to all of these issues.

Legal reforms to put trees on equal footing with other infrastructure would be a great place to start. Trees do come with risks as well as benefits, but we need to manage those risks rather than settling for hot, desolate streets.

Better planting standards will be important too. Technology already exists to create larger soil volumes under footpaths and roads. Clever asphalt-like materials (often called “permeable paving”) allow rain to infiltrate soils. These approaches cost more, but they work very well. Not only do they potentially double tree growth rates trees, but they also help reduce flood risks and minimise issues such as roots blocking drains or causing bumpy footpaths.

Our study is a clear call to action for cities to expand, maintain and protect their urban forests and parks to prepare for climate change. With another record-breaking summer predicted, hot on the heels of the world’s hottest year, growing tree canopy has never been more urgent. We must push forward with these reforms and ensure our urban populations have all the green infrastructure they need to protect them into the future. ![]()

Thami Croeser, Research Fellow, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.