April 8 - 14, 2018: Issue 355

Saving Our Species Program Aims To Keep Species In The Wild For 100 Years

- install around 6,500 fence pickets;

- roll-out 300 kms of plain wire;

- put in place 96 kms of netting; and

- attach 750,000 clips (to hold netting in place).

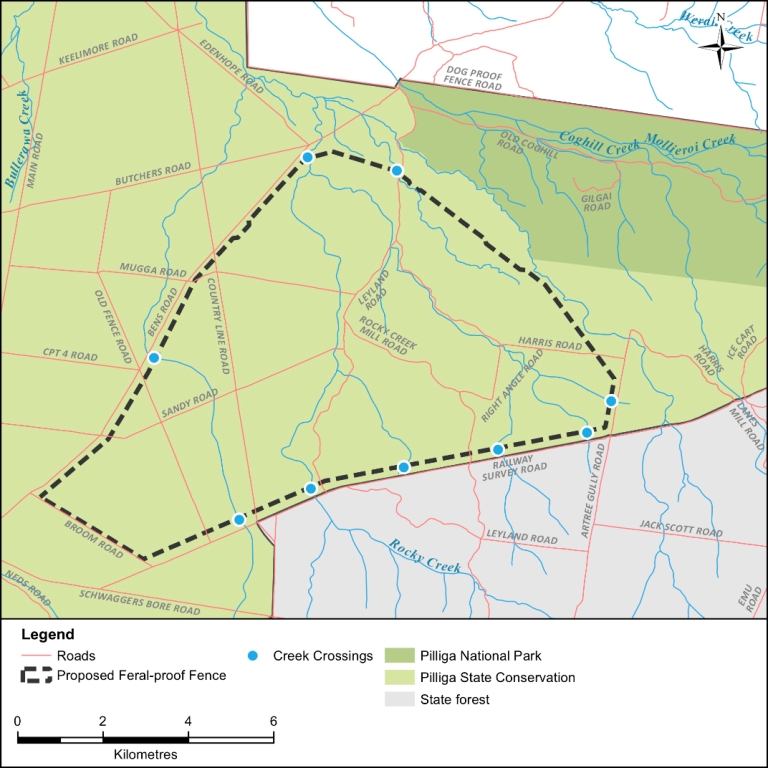

Bilbies To Return To NSW National Parks

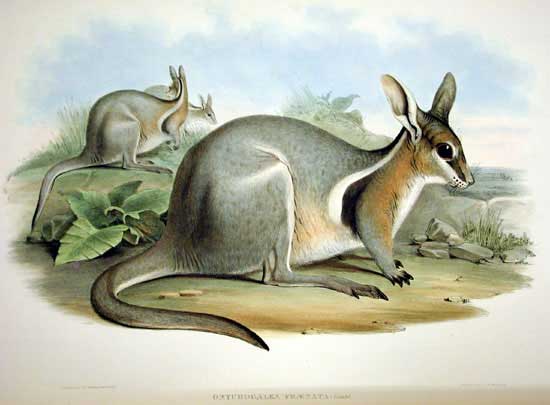

Bridled Nailtail Wallaby

Brush-Tailed Bettong

1.jpg?timestamp=1522886833880)

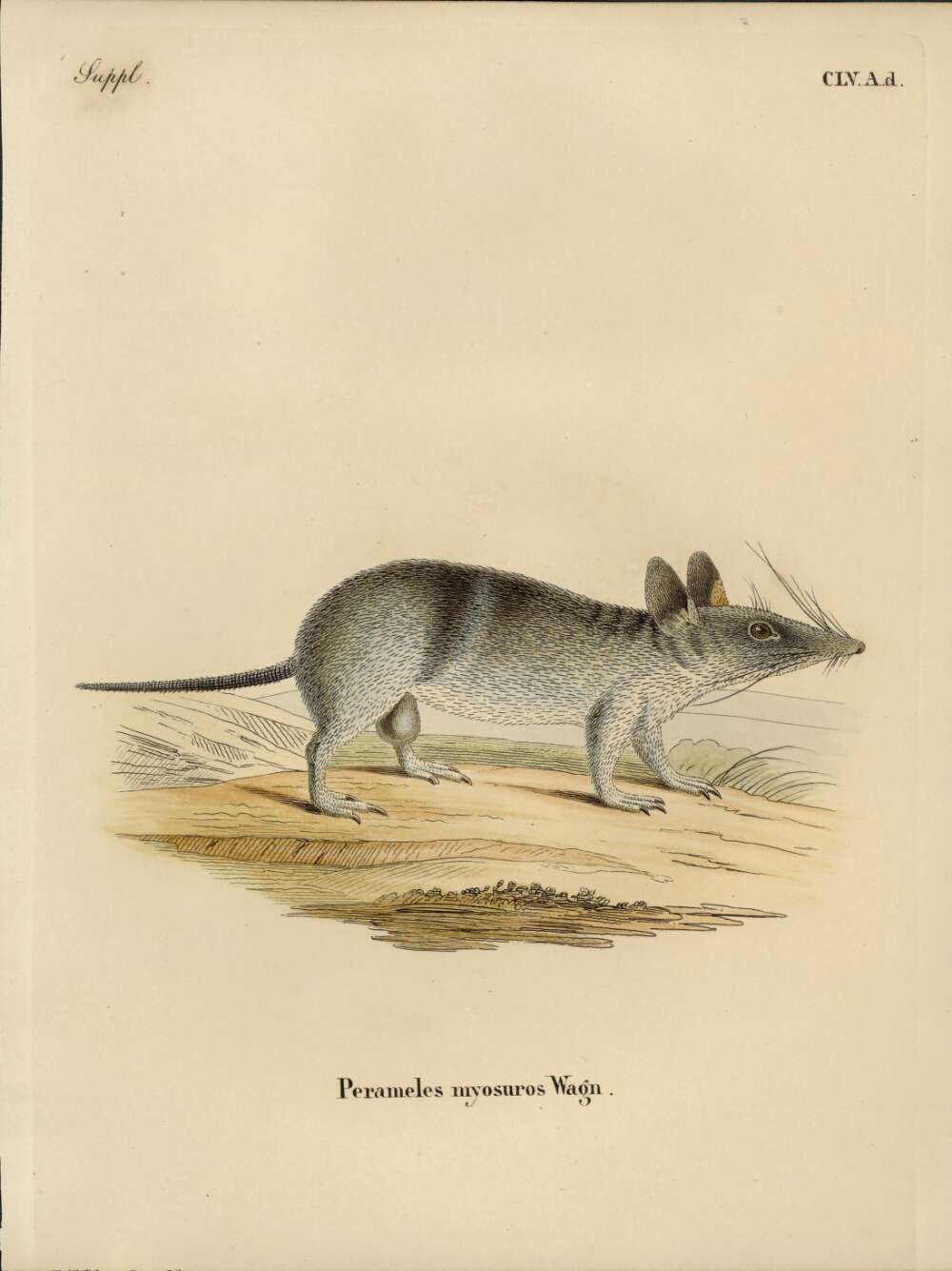

Western Barred Bandicoot

Plains Mouse

Extinct mouse resurfaces in state’s west

March 24, 2016: UNSW

University of New South Wales scientists find a female Pseudomys Australis, commonly known as the plains mouse, at the UNSW Fowlers Gap research station near Broken Hill. (Supplied: UNSW Fowlers Gap Arid Zone Research Station)

A big-eared native mouse declared extinct in NSW after not being seen for more than 80 years has been found at the UNSW Fowlers Gap Arid Zone Research Station near Broken Hill.

A young female of the species Pseudomys australis – commonly known as the plains mouse – was caught by UNSW scientists surveying for small mammals on the property, which is the only research station in the arid zone of NSW.

“It was very exciting to come across an animal we thought had gone for good in this state,” says UNSW biologist Dr Keith Leggett, who found the mouse with his UNSW Science honours student, Thanuri Welaratne.

“NSW has a dreadful record of extinctions of native mammals, and the reappearance of the plains mouse shows the benefit of carefully maintaining the conservation areas we have at Fowlers Gap,” says Dr Leggett, who is director of the research station.

The identity of the native mammal was confirmed by scientists including UNSW biologist Associate Professor Mike Letnic, who has caught them in the South Australian desert where they still occur in small numbers.

“The plains mouse is quite distinctive looking. It is one of the largest rodents in the arid zone and has relatively big ears and big feet,” says Associate Professor Letnic.

Native rodents play an important role in the Australian ecosystem, but since European settlement many species have declined dramatically in numbers and range, or become extinct.

“The decline is thought to be largely due to introduced predators such as red foxes and feral cats – particularly in areas where foxes flourished because they had lots of rabbits to feed on,” says Associate Professor Letnic.

“Overgrazing by sheep, cattle, kangaroos and goats has also probably contributed to the reduction in native rodents by degrading their habitats.

“The plains mouse in particular has disappeared from huge areas of the continent, so the find at Fowlers Gap is very unusual and great news.

“It may suggest they are recovering due to a decrease in the number of rabbits following the introduction of the calicivirus in the late 1990s. Fowlers Gap also has very few foxes, due to intensive controls on their numbers there,” says Associate Professor Letnic.

Dr Leggett and his colleagues have been surveying for small mammals at the research station for the past six years. Captures are recorded and then the animals are quickly released back into the wild.

Last year, a suspected male plains mouse was found in the same ungrazed conservation area of the property by UNSW Emeritus Professor Terry Dawson and Dr Steve McLeod of the NSW Department of Primary Industry, but it was not formally identified.

“This second capture and positive identification confirms their existence at Fowlers Gap, which is a pretty big deal,” says Dr Leggett.

The last recorded sighting of the plains mouse in NSW listed in the Atlas of Living Australia was in 1932, from the Liverpool Plains.

Fowlers Gap is used by scientists from UNSW and other local and international institutions for a wide range of studies on birds, kangaroos, reptiles, other flora and fauna, soil conservation and groundwater management. Some areas of the 39,000-hectare property have been continuously monitored for 50 years, providing a unique ecological record that earned the station a place on the Register of the National Estate in 1996. Artists are also attracted to the dramatic landscape at the station, which has several artists’ retreats.

Pseudomys australis. Photo by and courtesy of Peter Halasz

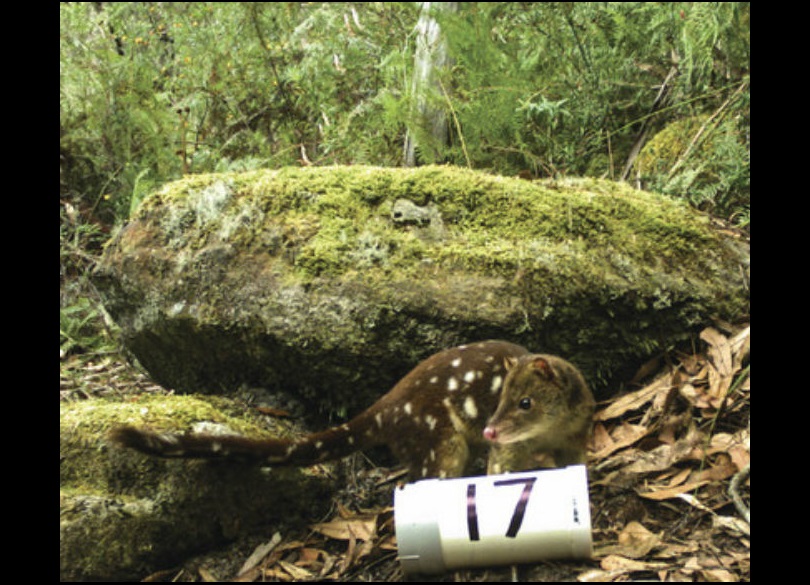

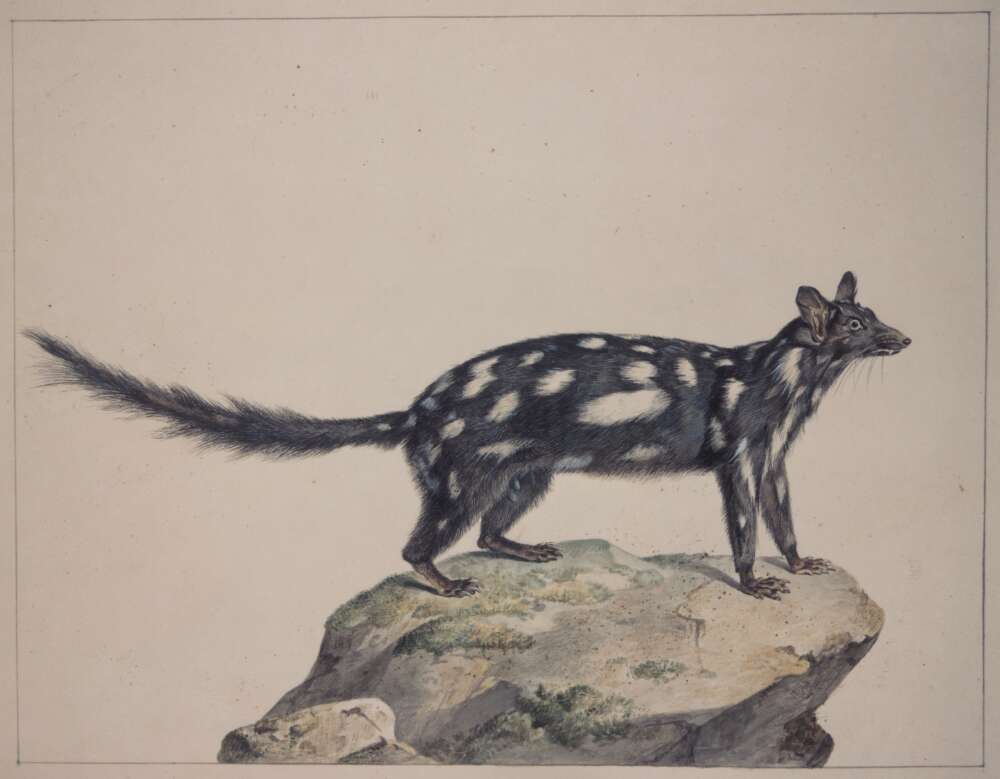

Western Quoll

Saving Our Species Program Background

- establish six new management streams to better target the management of each threatened species (Rec. 1)

- target investment at the minimum set of actions that are crucial for securing a species (Rec. 5)

- develop a sound, repeatable and transparent process for prioritising effort between species statewide (Rec. 6)

- develop a process for monitoring and reporting on the outcomes of projects and actions for threatened species (Rec. 7)

- develop a simple, user-friendly database to support program delivery (Rec. 8).

Introducing Saving Our Species : December 2013

- aligns everyone’s efforts under a single banner, so investment in threatened species conservation can be accounted for

- assigns threatened species to different management streams so the individual requirements of each species are clearly understood

- invites the NSW community and businesses to participate, because projects to save threatened species are collaborative efforts.

- site-managed species

- iconic species

- data-deficient species

- landscape-managed species

- partnership species

- keep watch species.

- share information on the website about what they are already doing

- subscribe to receive updates on the program and threatened species conservation projects

- search for a conservation project in their area

- learn more about threatened species.

About Saving Our Species

- initiating projects that improve habitat and control threats, such as weeding programs and fox baiting

- monitoring the effectiveness of these projects and the response of species and ecological communities to management activities

- supporting conservation projects in national parks and on private land.

- consults extensively with experts and applies independent peer reviewed science to species, populations of a species and ecological communities projects

- takes a rigorous and transparent approach to prioritising investment in projects that ensure benefit to the maximum number of species

- provides targeted conservation projects that set out the actions required to save specific plants and animals on mapped management sites

- regularly monitors the effectiveness of projects so they can be improved over time

- encourages community, corporate and government participation in threatened species conservation by providing a website and a database with information on project sites, volunteering and research opportunities.

- total annual investment and the return on the investment

- tangible outputs that can be totalled across the program

- threats under control or on track to be under control

- management sites with populations that are secure or on track to be secure

- species on track to be secure in the wild in NSW for 100 years.

Saving Our Species 2016-2021

Further Reading: Local Relevance

Collaboration Key To Saving Critically Endangered Northern Sydney Native - December 2016

Pittwater: Where the Wild Flowers Are - (1916 & 1917 lament) - September 2017

Grevillea Caleyi Seed Collection At Ingleside: PNHA

Volunteers at the Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) bush regeneration project at the Baha’i Temple, Ingleside had a special demonstratio n at their December bushcare morning when staff of the Royal Botanic Gardens undertook collection of seeds from the critically endangered Grevillea caleyi.

n at their December bushcare morning when staff of the Royal Botanic Gardens undertook collection of seeds from the critically endangered Grevillea caleyi.

Grevillea caleyi is restricted to small pockets within the Terrey Hills, Duffys Forest, Belrose and Ingleside areas. The Royal Botanic Gardens will be collecting seed from these sites for storage in the Australian PlantBank at the Mount Annan Australian Botanic Garden to provide long term back-up in case of any loss that may occur to the species in its natural habitat.

Meanwhile the PNHA bush regeneration project continues, with the dedicated team of volunteers including members of the Baha’i congregation working alongside professional bush regenerators to give this population of Grevillea caleyi a chance to increase.

They welcome new volunteers, so if you are interested in helping on the project in 2016 call David Palmer on 0404 171 940

Collaboration Key To Saving Critically Endangered Northern Sydney Native

9 December 2016

A three-year project to preserve and restore the critically endangered Grevillea caleyi shrub and endangered Duffys Forest ecological community culminated in a final Bushcare day at Ingleside this week

Driven by local volunteers through funding from Greater Sydney Local Land Services and the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH), the project focusses on protecting vegetation on the grounds of the Baha’i Temple which is home to the endangered native plant.

Greater Sydney Senior Land Services officer Rebecca Mooy said Northern Sydney had the only population of Grevillea caleyi in the world.

Photo by Greg Steenbeeke – Orkology.

“There are currently less than 20 mature plants and around 50 seedlings at the Temple grounds. Our volunteers have done an incredible job to protect this plant and raise awareness about its importance to our natural environment,” she said. “Their work has involved, bush regeneration, mapping of plants, seed collection, protection of seedlings and management of other plant species at the site.

“What has been achieved over the past three years is a great example of meaningful collaboration between community and government.”

OEH Senior Threatened Species Officer Erica Mahon said great team work has been pivotal to the success of the three year project to save the critically endangered plant, which can be found in the Northern Sydney suburbs of Ingleside, Terrey Hills and Belrose.

“It’s been inspiring to work with such a devoted group of volunteers. Their commitment has ensured the survival of the critically endangered Grevillea caleyi. The funding is one thing, but without the dedication of the local landholders and volunteers, projects like this couldn’t succeed.

“I look forward to continuing to work in partnership with the Pittwater Natural Heritage Association and the Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’i as we continue the successful Bushcare mornings with funding under the Saving our Species Program,” Ms Mahon said.

David Palmer of Pittwater Natural Heritage Association said volunteers had contributed 11,000 volunteer hours over the three year project.

"While the project may be over it’s not the end of efforts to save and protect the Grevilla caleyi, and we look forward to continuing our work in the future,” Mr Palmer said.

This project has also been supported by the former Pittwater and Warringah Councils, the Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'í, and the Pittwater Natural Heritage Association.

From Local Land Services – Greater Sydney, NSW Government

L to R - Erica Mahon Senior Threatened Species Officer NSW OEH, David Palmer, Volunteer with Pittwater Natural Heritage Association / Bahai Bushcare and Ned Macken Volunteer Supervisor from Australian Bushland Restoration.