Scotland Island Dieback Accelerating: IPART Review of increases In Sydney water's pricing proposals An Opportunity to ask: 'what happened to the 'Priority sewerage Scheme' for our Island?

Residents will have noticed the change in the tree canopy of Scotland Island over the past decade and witnessed an accelerated increase in dieback of the tree canopy in just the past few years.

Scotland Island on April 7 2013:

Scotland Island March 7 2015:

Scotland Island in July 29, 2023:

In July 29, 2023 (from Church Point):

Scotland Island from Salt Pan Cove and Florence Park (Newport/Clareville) on November 22, 2024:

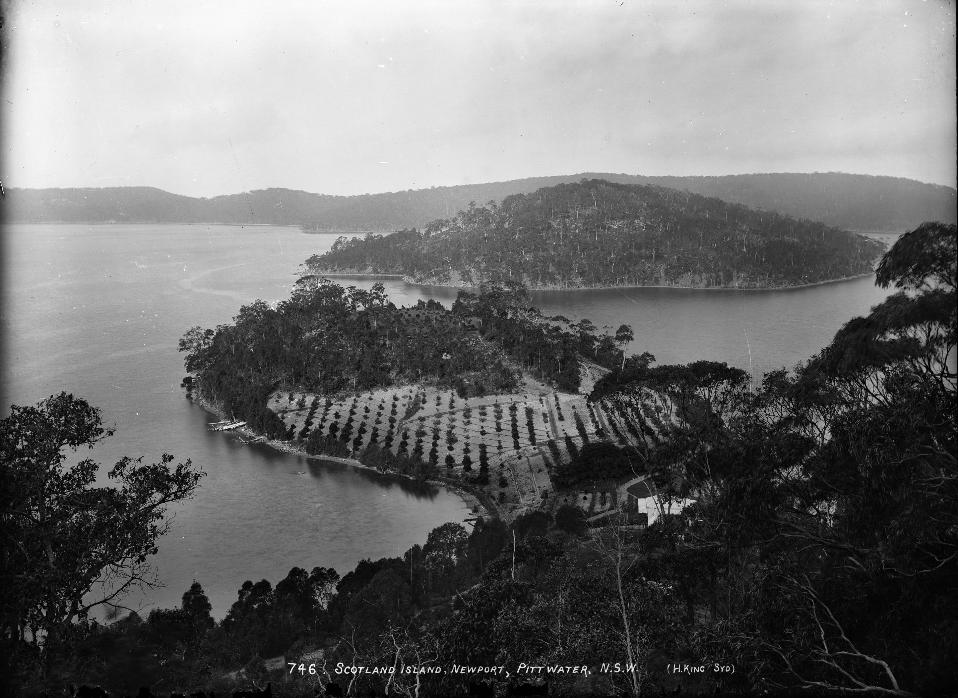

In circa 1880-1886:

'Scotland Island, Newport, Pittwater, N.S.W.', photo by Henry King, Sydney, Australia, c. 1880-1886. From Tyrell Collection, courtesy Powerhouse Museum - taken from above Rocky Point Peninsula and Lovett's Bay looking east.

The above was during the Benns-Jenkins decades of occupation of the island. Joseph Benns, (real name Ambrol Josef Diercknecht 1816-March 29, 1900) and Charles Jenkins, leased Scotland Island in 1855 for seven years. When they discovered those who had claimed ownership of the island did not have title they ceased paying rent and continued living there, building a home and cultivating the land, which may account for the patches of bare ground that can be seen on the island in the above photo. Mr. Benns was a master mariner and owned at least two ships, so he may have been harvesting timber as well - the image shows those trees closest to the water (easiest to fell and load onto a ship) are gone. 'Timber-getters' worked acros Pittwater even into the 1920's, cutting down the oldest, tallest trees. Benns was the husband of Martha Catherine Benns, the lady known locally as the 'Queen of Scotland Island'.

Pittwater wharf at Bayview facing Scotland Island (at Right), 1900, and looking towards Church Point - from NSW State Records and Archives, Item: FL11281545:

Pittwater from above Lovetts, Scotland Island to the left; 1900. Item: FL11281628, courtesy State Records of NSW:

Apparently dieback may be caused by psyllid lerps insect infestations. However, our trees in the PON yard (also Pittwater Spotted gums) had an abundance of these in 2014 and none were lost or even looked like they would die.

White ash substance on eucalypts - remnants of the casing of the nymph-stage of the psyllid lerps insect.

Above: Cicada rain on a sunny day - December and January 2014. We had so many cicadas, and continue to, that we are being 'peed' on during some summers. And it's loud, really LOUD, there are so many some years. But no trees have died from too many cicadas during the 40+ years they have been deafening us from our spotted gum trees.

In March 2023 Roy Baker, Editor of the Pittwater Offshore Newsletter (the original PON) and a Scotland Islander, penned a report, 'Scotland Island's Tree Canopy - Is it really dying?' where he stated:

'Northern Beaches Council have confirmed that their staff have observed die-back among both young and mature spotted gums on the island’s north-facing slopes. They describe the die-back issue as complex, without a clear cause.

‘It’s clearly not drought-induced’, a spokesperson told me. ‘It’s possible that there is an insect or fungal outbreak across the region following the three moist years we've had.’ -'

However, the images above show the dieback is happening on the south and east sides of the island, as well as the north. Added to this, the hills beyond Scotland Island on Rocky Point, Church Point and further west and north, as well as across the bay on the eastern side of Pittwater, remain as green as ever - there is no dieback elsewhere in Pittwater.

A respondent to Roy's article, Scotland Island's Trees - A Spotted Gum plantation by Alan Erdman (June 2023), an arborist with decades of experience, who also has been connected with the island since 1975, explained what he thinks is happening:

'There is probably a complex interplay of different factors, ranging from septic systems to climate change. But, in essence, nature does not like a monoculture. When they arise nature will turn on itself, with pests and disease becoming more prevalent. This can lead to devastating results. To take an extreme example, when a farmer plants a field of wheat, the incidence of pests and disease significantly increases and considerable crop losses can result.

In a natural ecosystem a full tree canopy will rarely provide space for a young tree to reach maturity. In short, an older tree first needs to fall down. When that rare event happens it creates a race amongst the understorey, which only the strongest trees will win.

Compare that to a situation in which there is extensive canopy clearing. There is then opportunity for many more trees to mature. There is less natural selection, therefore greater propensity for genetically weaker trees to become dominant.

This is what, I believe, is the main underlying driver for the current state of tree dieback. And that’s why there often doesn’t seem to be rhyme or reason to why some trees are dying while others flourish. If you look at a group of trees next to each other you will typically see around three-quarters in decline but the rest with healthy canopies. The flourishing trees are those more able to withstand environmental pressures, while the others are genetically weaker and probably should not have been there in the first place.

Basically, what we’ve ended up with is akin to a Spotted Gum plantation. And a quick Google search will reveal that Spotted Gum plantation managers are facing similar situations to what is happening on the island. For a couple of examples, click here (2020) and here (2017).'

Others are attributing the increase and acceleration of tree dieback to increased numbers of residents on the island putting pressure on the septic systems. Scotland Islanders, almost 100 years after sustained growth in homes from subdivisions occurred, are still not connected to mains water or the sewerage system.

The Scotland Island Residents Association (SIRA) has been trying for decades to bring the island on to the same system the rest of Sydney enjoys.

There are 377 dwellings on Scotland Island, according to the council. The Australian Bureau of Statistics' 2021 Census recorded that 711 people were 'usually resident' on Scotland Island on Tuesday, 10 August 2021. The island's population is partly seasonal: around 23% of the 358 private dwellings on the island were classed as 'unoccupied' on that Census night. In Summer he population is closer to 1000 people.

In January 2011, incoming Premier of NSW Barry O’Farrell wrote:

“The NSW Liberals and Nationals will fast-track the connection of sewerage … clearing most of the Keneally Labor Government's Priority Sewerage Program backlog,… We will also ensure remaining areas such as Austral, West Hoxton, Menangle, Menangle Park, Nattai and Scotland Island are connected to the sewer as a matter of priority...”

In 2012, the NSW Government’s Northern Beaches Regional Action Plan committed to:

Better manage waste water and improve ocean water quality including upgrades to waste water and sewerage treatment facilities for Scotland Island”, (page 13). And “The provision of wastewater services to Scotland Island is a matter of priority …” (page14).

Scotland Island was subsequently listed under the 'Priority Sewerage Program'. Sydney Water's Operating Licence had committed them to delivering schemes under the Priority Sewerage Program.

The Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (IPART) review of Sydney Water's Operating Licence in 2015 noted Sydney Water's estimate that the capital cost of providing wastewater services to Scotland Island would be $235,000 per lot ($2014/15). Sydney Water claimed delivering the remaining schemes under the Priority Sewerage Program would result in an unacceptable increase to Sydney Water service charges for Sydney Water's 1.7 million wastewater customers.

That was accepted by IPART and therefore Sydney Water's next Operating Licence 2015-2020 did not contain any commitment to delivering schemes under the Priority Sewerage Program, but did state that Sydney Water must comply with any government review of the Program.

Sydney Water's Operating Licence, reviewed every five years, includes a review of commitments to programs such as the Priority Sewerage Program.

IPART's 2019 Review of the Sydney Water Operating Licence, to which SIRA made a submission, stated in its final report:

Recommended Priority Sewerage Scheme clauses

3.3 Priority Sewerage Program

3.3.1 Sydney Water must participate cooperatively in any NSW Government review of the Priority Sewerage Program.

3.3.2 If required by the Minister, Sydney Water must implement and comply with any outcomes (including timeframes) of any NSW Government review of the Priority Sewerage Program.

[Note: The areas to which the Priority Sewerage Program applies are Austral, Menangle, Menangle Park, Nattai, Scotland Island and Yanderra as listed in Schedule B of this Licence.]

So; a big fat 'nothing'.

At the same time of the 2019 Review the by then in charge of the area Northern Beaches Council received State Government funding through the Stronger Communities Fund to conduct an independent investigation into the commercial feasibility of water and wastewater services to Scotland Island.

The Council commissioned a study and assessment which found:

''Wastewater systems consist of on-site management systems that are generally unsuitable for the topography and geology of the Island. Scotland Island is steep-sided bedrock with shallow soils of sandy loam (highly permeable) with sandy clay loam subsoils (highly impermeable). Evidence of overflow of septic systems was observed during the site inspection and audit conducted as part of this investigation. Septic odours and high numbers of mosquitos were also observed, supporting anecdotal reports of these issues.

During the site inspection undertaken for this assessment, evidence of significant noxious weed infestation and Eucalyptus dieback was observed. It is likely that altered soil moisture and nutrient characteristics caused by poorly performing on-site wastewater management systems are contributing factors. It this regard, it should be noted that the vegetation on the Island is listed as an endangered ecological community (Pittwater Spotted Gum Forest).''

And:

Physiochemical degradation of soil due to effluent disposal is expected to be widespread and both surface and ground water resources are expected to be polluted. An implication of this is that native vegetation may be placed at risk and evidence of Eucalyptus dieback has been documented in the past (Scotland Island Wastewater Impact Study 1997). The vegetation of the Island is listed as an endangered ecological community (Pittwater Spotted Gum Forest, see Figure 2). The presence of this endangered ecological community further increases the implications of this degradation.

A site visit was conducted during the preparation of this report (see Appendix C for photographs). Extensive and widespread weed growth was observed during the site visit. A failing wastewater system represents a concentrated source of not only faecal matter and bacteria but also nutrients. High nutrient loads are a likely contributing factor to the widespread weed issue and degradation of native vegetation through nutrient overload and weed propagation.''

And:

''It should also be noted that Scotland Island is in closer proximity to heavily populated areas of Sydney than Dangar Island. When considered in these terms, it is a reasonable community expectation that Scotland Island be provided with the same level of water and wastewater services as Dangar Island.

The emergency water supply pipeline set up for firefighting and then later as an emergency drinking water supply, is now used by the majority of residents. This supply is officially non-potable. On-site wastewater systems are of insufficient capacity to cope with the substantial use of the non-potable supply. This has contributed to water quality impacts on the Pittwater Estuary, particularly following rain events.

The annual State of the Beaches reports, over the decade and a half the news service has run them, has consistently stated in regards to Scotland Island:

'' indicates microbial water quality is considered suitable for swimming most of the time but may be susceptible to pollution after rain, with several potential sources of faecal contamination including onsite systems.''

Council's Water and Waste Water Feasibility Study [Endorsed by Council Nov 2020] found:

'The study estimated the cost to construct the preferred options and provide water and wastewater services to the 377 properties on Scotland Island would be just under $69 million (in today's prices).

The study recommended that the state government fund the scheme.'

Currently, IPART is seeking feedback on the next five years of how much Sydney Water can charge - see: IPART seeks feedback on water pricing proposals: Submissions close December 9

Sydney Water has proposed bills increase by 18% next year, and then further increases of 7% a year plus inflation, or around 31.5% overall between 2025-2030.

The documents state Sydney Water has proposed $16.5 billion in investment over the next 5 years.

'Almost 60% of its proposed capital investment ($9.5 billion) over the next 5 years is to deliver new services to growth areas across Greater Sydney, including for new water assets and wastewater treatment facilities. It would spend around $6.3 billion to renew existing infrastructure.

The words 'Scotland Island' do not appear once in the 2024 Pricing proposal - Sydney Water document submitted to IPART by Sydney Water. Nor does any reference to a 'Priority Sewerage Scheme' appear. The document, after talking about the 570,000 new dwellings in Western Sydney that will need a tap and a loo, does use a map to show where it supplies water to - with Scotland Island included.

If your water supply is non-potable, it means the water has come from a non-potable, or non-drinking, water source. Water provided as non-potable water to be used as a supplementary water supply. It is not intended to be your primary water supply.

Sydney Water wants to increase all local water bills by an average of $620 per annum for the next five years, or an extra $3100 per household on average all up, while we sit still and watch Scotland Island's trees die.

The vision of Sydney Water, as part of the Greater Sydney Water Strategy, as stated in their 2022 Annual Report is “creating a better life with world class water services”.

Two of their key research and innovation priorities are “reliable and resilient water supply” and “healthy waterways and environment”. Through their Urban PlungeTM strategy, Sydney Water aims to “to fast-track the delivery of more swimming and water recreation opportunities across Greater Sydney”, “a clean safe place to swim…. to swim and play and provide access to recreational waterways for people across Greater Sydney”.

The 2024 (for 2025-2030) pricing proposal states in its opening pages Sydney Water's objectives are to:

- protect public health

- protect the environment

- be a successful business.

Safe drinking water for Scotland Island residents, a safe sewerage system to prevent disease, and cleaner estuary waters for visitors and residents alike as a result, AND saving an endangered ecological community are the markers of a successful business and epitomise Sydney Water's objectives.

Submissions close December 9.

The 2024 Pricing proposal - Sydney Water

Provide 'feedback' HERE