Just days out from the United States presidential election last month, X (formerly Twitter) suddenly crippled the ability of many major media and political organisations to reach audiences on the social media platform.

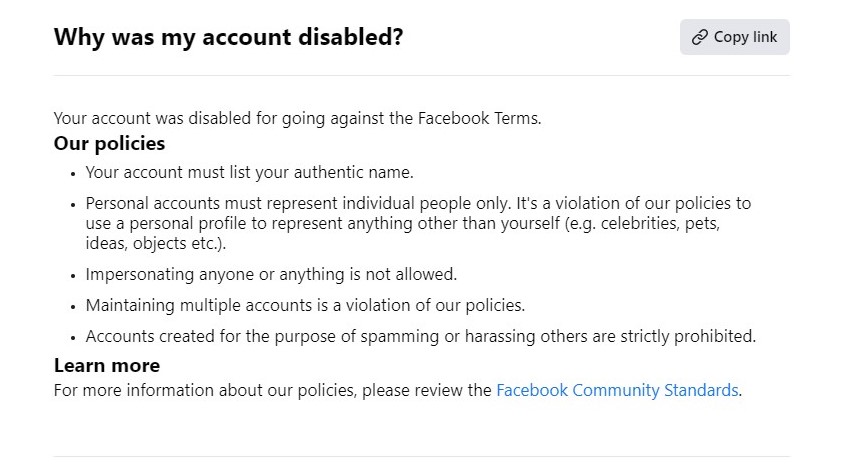

Without warning, the platform, under tech billionaire Elon Musk’s stewardship, announced major changes to the main pathway these organisations use to disseminate content. This pathway is known as the application programming interface, or API. The changes meant users of the free tier API would be limited to 500 posts per month – or roughly 15 per day.

This had a huge impact on news media outlets, including The Conversation – especially with one of the biggest political events in the world just around the corner. It meant software programs designed to quickly and easily share stories wouldn’t work and newsrooms had to scramble to post stories manually.

In turn, it also had a huge impact on the public’s ability to access high quality, independent news at a time when there was a flood of polarising fake news and deepfakes on X and other social media platforms.

But this is just one example of how social media companies are throttling public access to quality news content, which research has shown is a proven antidote to the insidious effect of misinformation and disinformation. If this trend continues, the implications for democracy will be severe.

The backend of online communication

An API acts like a service corridor between websites and other internet services such as apps. Just like your computer has a keyboard and mouse at the front, then a series of sockets at the back, APIs are the backend that different websites and services use to communicate with each other.

An example of an API in action is the weather updates on your phone, where your device interacts with the API of some meteorology service to request temperatures or wind speeds.

Access to social media APIs has also been essential for news companies. They use APIs to publish stories across their various platforms at key intervals during the day.

For instance, The Conversation might publish a story on X, Facebook, Instagram and Bluesky all at the same time through an automated process that uses APIs.

Journalists and researchers can also use APIs to download collections of posts to identify and analyse bot attacks and misinformation, study communities and understand political polarisation.

My own research on political behaviours online is one such example of a study that relied on this data access.

APIpocalypse

API restrictions – such as those suddenly imposed by X before the US presidential election – limit what goes in and what comes out of a platform, including news.

Making matters worse, Meta has removed the News Tab on Facebook, replaced the CrowdTangle analytics tool with another system that is less open to journalists and academics, and appears to have reduced the recommendation of news on the platforms.

X also seems to have reduced the reach of posts including links to news sites, starting in 2023.

After once being open and free, Reddit’s APIs are also essentially inaccessible now without expensive commercial licenses.

The net result is that it is getting harder and harder for the public to access high quality, independent and nonpartisan news on social media. It is also getting harder and harder for journalists and researchers to monitor communities and information on social media platforms.

As others have said, we really are living through an “APIpocalypse”.

The exact effect of this on any of the 74 national elections around the world this year is unclear.

And the harder it is to access APIs, the harder it will be to find out.

A public hunger for quality news

Research suggests there has been renewed diversification in the social media sector. This will likely continue with the recent explosion of X clones such as Bluesky in the aftermath of the US presidential election.

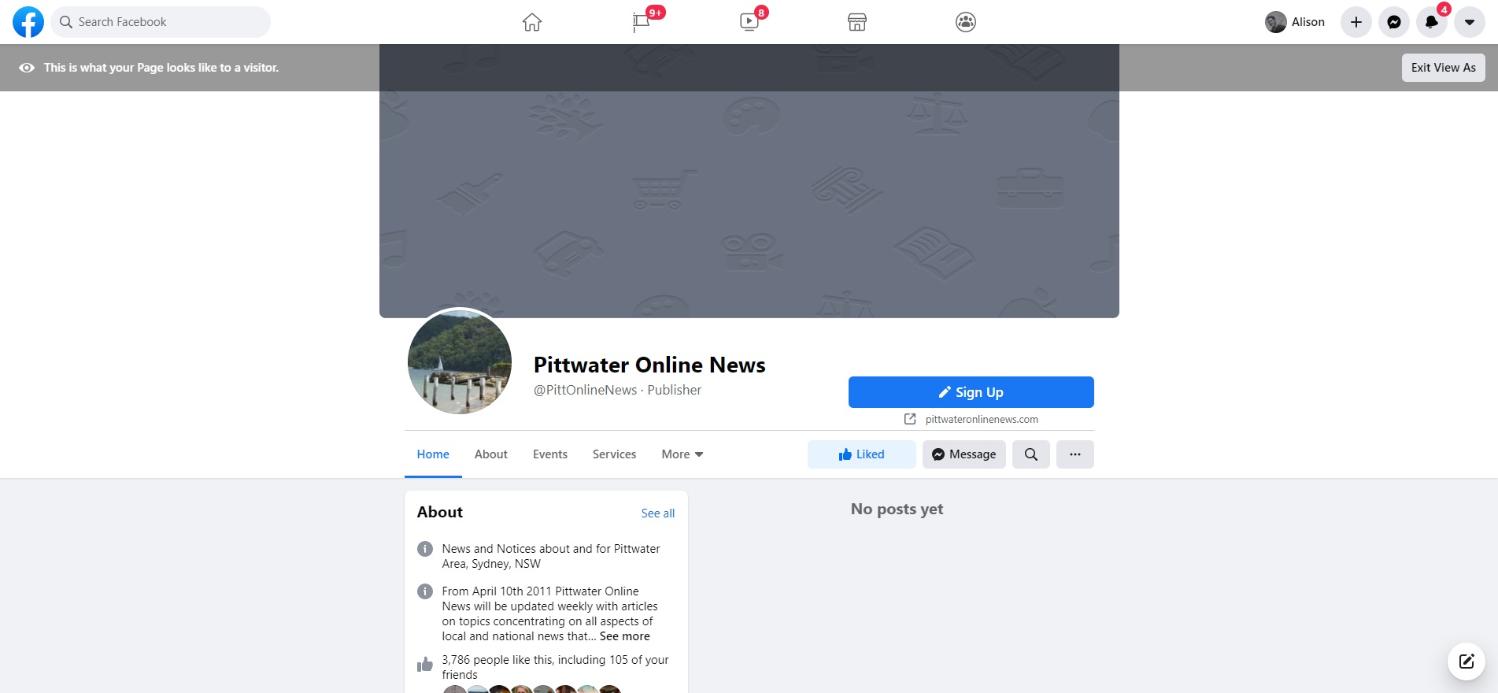

News organisations are capitalising on this by expanding their profile on these emerging social media platforms. In addition, they are also focusing more on email newsletters to reach their audience directly.

There is an enormous public hunger for reliable and trustworthy information. We know that globally people value quality, nonpartisan news. In fact, they want more of it.

This should give news media outlets hope. It should also inspire them to rely less on a few monolithic tech companies that have no incentive to provide the public with trustworthy information, and continue investing in new ways to reach their audiences.![]()

Cameron McTernan, Lecturer of Media and Communication, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

.jpeg?timestamp=1733364639137)