We know feral cats are an enormous problem for wildlife – across Australia, feral cats collectively kill more than three billion animals per year.

Cats have played a leading role in most of Australia’s 34 mammal extinctions since 1788, and are a big reason populations of at least 123 other threatened native species are dropping.

But pet cats are wreaking havoc too. Our new analysis compiles the results of 66 different studies on pet cats to gauge the impact of Australia’s pet cat population on the country’s wildlife.

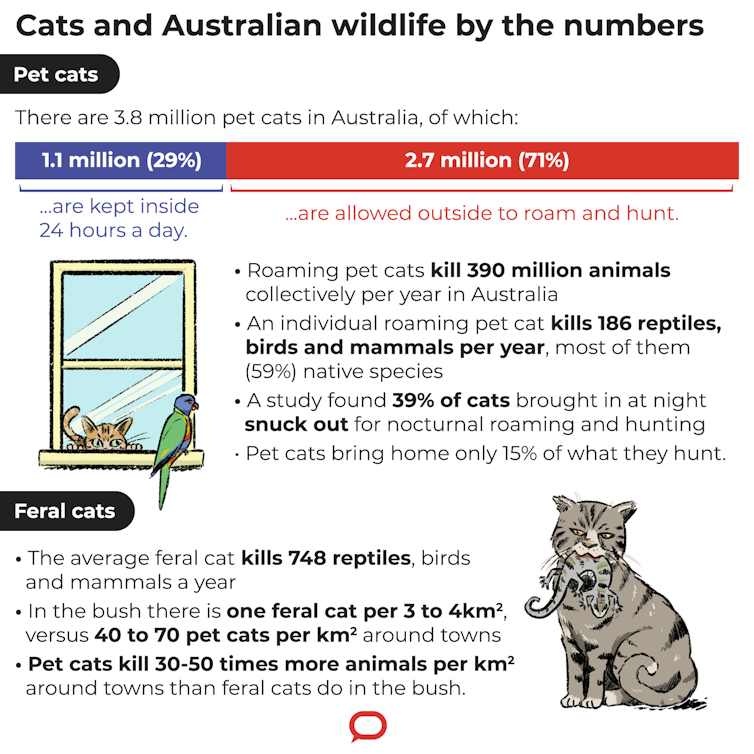

The results are staggering. On average, each roaming pet cat kills 186 reptiles, birds and mammals per year, most of them native to Australia. Collectively, that’s 4,440 to 8,100 animals per square kilometre per year for the area inhabited by pet cats.

If you own a cat and want to protect wildlife, you should keep it inside. In Australia, 1.1 million pet cats are contained 24 hours a day by responsible pet owners. The remaining 2.7 million pet cats – 71% of all pet cats – are able to roam and hunt.

What’s more, your pet cat could be getting out without you knowing. A radio tracking study in Adelaide found that of the 177 cats whom owners believed were inside at night, 69 cats (39%) were sneaking out for nocturnal adventures.

Surely not my cat

Just over one-quarter of Australian households (27%) have pet cats, and about half of cat-owning households have two or more cats.

Many owners believe their animals don’t hunt because they never come across evidence of killed animals.

But studies that used cat video tracking collars or scat analysis (checking what’s in the cat’s poo) have established many pet cats kill animals without bringing them home. On average, pet cats bring home only 15% of their prey.

Collectively, roaming pet cats kill 390 million animals per year in Australia.

This huge number may lead some pet owners to think the contribution of their own cat wouldn’t make much difference. However, we found even single pet cats have driven declines and complete losses of populations of some native animal species in their area.

Documented cases have included: a feather-tailed glider population in south eastern NSW; a skink population in a Perth suburb; and an olive legless lizard population in Canberra.

Urban cats

On average, an individual feral cat in the bush kills 748 reptiles, birds and mammals a year – four times the toll of a hunting pet cat. But feral cats and pet cats roam over very different areas.

Pet cats are confined to cities and towns, where you’ll find 40 to 70 roaming cats per square kilometre. In the bush there’s only one feral cat for every three to four square kilometres.

So while each pet cat kills fewer animals than a feral cat, their high urban density means the toll is still very high. Per square kilometre per year, pet cats kill 30-50 times more animals than feral cats in the bush.

Most of us want to see native wildlife around towns and cities. But such a vision is being compromised by this extraordinary level of predation, especially as the human population grows and our cities expand.

Many native animals don’t have high reproductive rates so they cannot survive this level of predation. The stakes are especially high for threatened wildlife in urban areas.

Pet cats living near areas with nature also hunt more, reducing the value of places that should be safe havens for wildlife.

The 186 animals each pet cat kills per year on average is made up of 110 native animals (40 reptiles, 38 birds and 32 mammals).

For example, the critically endangered western ringtail possum is found in suburban areas of Mandurah, Bunbury, Busselton and Albany. The possum did not move into these areas – rather, we moved into their habitat.

What can pet owners do?

Keeping your cat securely contained 24 hours a day is the only way to prevent it from killing wildlife.

It’s a myth that a good diet or feeding a cat more meat will prevent hunting: even cats that aren’t hungry will hunt.

Various devices, such as bells on collars, are commercially marketed with the promise of preventing hunting. While some of these items may reduce the rate of successful kills, they don’t prevent hunting altogether.

And they don’t prevent cats from disturbing wildlife. When cats prowl and hunt in an area, wildlife have to spend more time hiding or escaping. This reduces the time spent feeding themselves or their young, or resting.

In Mandurah, WA, the disturbance and hunting of just one pet cat and one stray cat caused the total breeding failure of a colony of more than 100 pairs of fairy terns.

Benefits of a life indoors

Keeping cats indoors protects pet cats from injury, avoids nuisance behaviour and prevents unwanted breeding.

Cats allowed outside often get into fights with other cats, even when they’re not the fighting type (they can be attacked by other cats when running away).

Roaming cats are also very prone to getting hit by a vehicle. According to the Humane Society of the United States, indoor cats live up to four times longer than those allowed to roam freely.

Indoor cats have lower rates of cat-borne diseases, some of which can infect humans. For example, in humans the cat-borne disease toxoplasmosis can cause illness, miscarriages and birth defects.

But Australia is in a very good position to make change. Compared to many other countries, the Australian public are more aware of how cats threaten native wildlife and more supportive of actions to reduce those impacts.

It won’t be easy. But since more than one million pet cats are already being contained, reducing the impacts from pet cats is clearly possible if we take responsibility for them.![]()

Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Brett Murphy, Associate Professor / ARC Future Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Chris Dickman, Professor in Terrestrial Ecology, University of Sydney; John Woinarski, Professor (conservation biology), Charles Darwin University; Leigh-Ann Woolley, Adjunct Research Associate, Charles Darwin University; Mike Calver, Associate Professor in Biological Sciences, Murdoch University, and Sarah Legge, Professor, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.