April 5 - 11, 2020: Issue 445

Stargazing In Pittwater: An End Of Daylight Savings Pastime - The 2020 CWAS David Malin Photography Awards Are Now Open

The CWAS 2020 'David Malin Awards' are now open, with entries received online until Tuesday June 30th, with one category for phone photographers this year. Named for revered Ingleside astronomer and astrophotographer David Malin, submission of entries will be accepted from Wednesday, 1 April 2020 - details below. Not only have many Pittwater landmarks featured among the finalists and commended images for this award each year, in 2019 a Pittwater High School student and avid star photographer, Mona Vale's Austin Turpin won the Junior category for this wonderful picture:

Austin Turpin's How Small It Makes Me Feel won the junior category. (Supplied: CWAS/Austin Turpin)

With the upcoming school holidays, the 2020 CWAS David Malin Awards now open, and some great sky stories about to erupt above our heads, it's worth reminding Pittwater telescope and camera, or even phone owners that the year's biggest supermoon comes with the April 2020 full 'super pink' moon as it beams in the east after sunset April 8, climbs highest up for the night around midnight, and sets in the west around sunrise April 9. The best time to see it will be around 11pm on the 8th.

In the northern hemisphere, the April full Moon is named after the first flower of spring — pink moss or phlox and can also be known as the sprouting grass Moon, fish Moon, hare Moon, egg Moon and paschal Moon. This Moon is closest to Earth (perigee) this month at a distance of 356,907 kilometres from Earth, and means we have what is commonly called a super-Moon, although astronomers prefer to go by a more scientific term describing the phenomenon as a perigee-syzygy moon.

Later in April the Lyrid meteor shower – April’s shooting stars – lasts from about April 16 to 25. About 10 to 15 meteors per hour can be expected around the shower’s peak, in a dark sky. The Lyrids are known for uncommon surges that can sometimes bring the rate up to 100 per hour. In 2020 the peak viewing hours to take place in the dark hours before dawn April 22, with no moon to ruin the show.

THE COMET.

Mr. C. R. Grimstone, writing from Fowler's Bay, Pittwater, states that he saw the comet on Monday, April 10, about 5 a.m.. Just before day break. It showed out quite distinctly. The tail was easily distinguishable to the naked eye. THE COMET. (1917, April 27). The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 - 1930), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article239383682

Cyril Grimstone's note is in reference to a new comet named the 'Wolf' Comet that was first sighted on April 27th, 1916 at Heidelberg by Max Wolf. Although now known as the 'Wolf' comet it was also, as comets were ascribed as being omens, called the 'Peace' comet during this year of World War One:

THE COMET.

The "peace comet" is now clearly seen in the eastern sky.

Mr. C. A. M'Leod, engine driver of Queen's-avenue, Ascot Vale, Victoria (according to a Melbourne paper) saw the new comet before it had been noticed by the Melbourne Observatory. Whilst driving a train from Melbourne to Fern Tree Gully his attention was attracted by what appeared at casual sight to be a flashing of electric light along the wires adjacent to the line. On looking "further afield" he saw that the light was reflected by an unusually large and brilliant comet in the east, just above the point of sunrise. The morning was chilly and beautifully clear. Mr. M'Leod said he was no astronomer, but one did not need to be an astronomer to tell a comet of that sort when one saw it. Its head and long milky-like tail, slightly widening towards the tip, and pointing towards sunrise, were unmistakable. He and his fireman were immensely interested in the sight, and had it in full view from 5 AO until after 6 o'clock. They had no idea that they were making a discovery at the time. Later he gathered that the Observatory folk had not noticed the event, and that quickened his interest. He described to the Observatory through the telephone what he had seen. THE COMET. (1917, April 21). Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, NSW : 1888 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article45429939

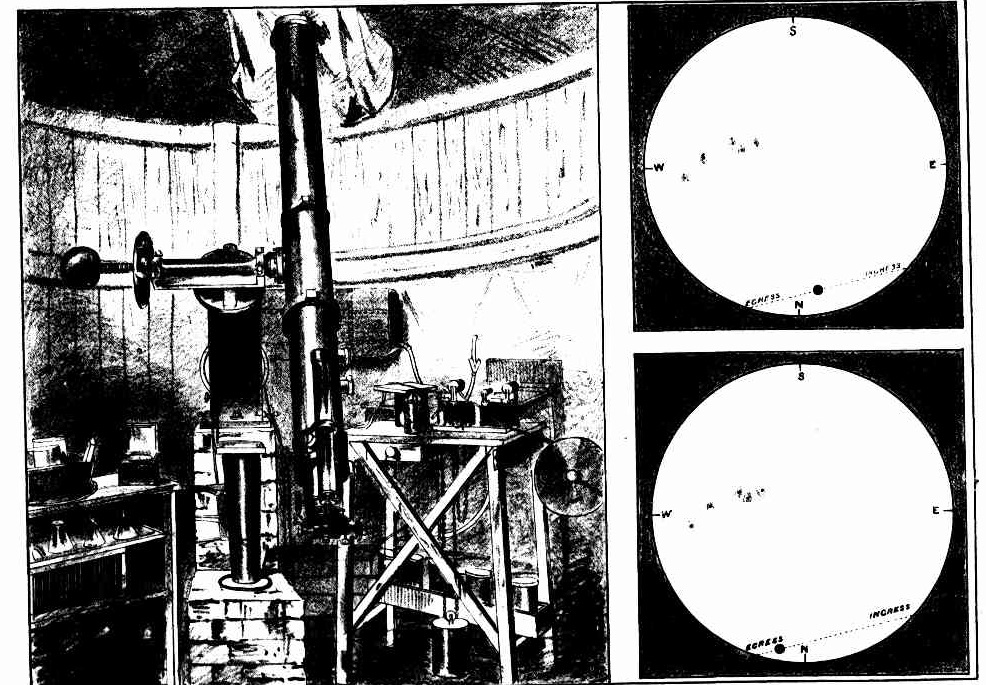

This wasn't the first use of Astronomy in local terms to have been keenly followed by the local amateur populace - the 1874 and 1882 Transits of Venus across the face of the sun were also keenly followed for reasons that illustrate how the pursuit of science, and this branch in particular, has made advances for others in other fields - the 1874 Transit of Venus took place on December 9th:

THE TRANSIT OF VENUS.

THAT the expenditure .of £200,000 on this day's special astronomical observations, to be carried on at seventy or eighty stations scattered over Egypt, Siberia, China, Japan, India, Cape colony, Australia, and islands of the Indian Ocean, and the racine, will not merely serve to gratify scientific curiosity--though that is no mean object-but to promote the safety and convenience of navigation and other useful purposes, is manifest from this statement of Professor Forbes :

" In the first place, the longitudes of a host of stations all over the globe will be accurately determined, and it is a remark by no means unworthy of notice that the simple observation of the local time of contact will give the inhabitants of East Africa and of all Asia an accurate means of determining their absolute longitudes. If, moreover, as has been proposed, San Francisco and Japan are to be compared directly as to longitude, the whole circuit of the globe will be completed by telegraphic and accurate chronometric determinations."

And, of course, accurate information as to longitudes secures more correct charts of rocks and headlands-that is, better protection against shipwreck. THE TRANSIT OF VENUS. (1874, December 9). Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1875), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article61020633

Collectors of all things starry, who may have a small telescope as well as a box edition of Star Wars and have taped every available episode of Star Trek (along with collectable figurines, t-shirts, mugs, toys and various other paraphernalia) will, in many cases, not be aficionados in speaking Klingon but will have a pervading interest in actual Astronomy and can point out to you which stars are which in the ever revolving night sky. Their interest is in the big cosmic events and having mementos from these - such as the lithograph print above, No. 18 of 75 Issued by then Blue Mountains resident Kate Burness.

In April 1986 another comet came closer to Australian soil than it would elsewhere - Halley's Comet - which for this visit was best seen, according to the then Astronomers, from the Southern Hemisphere and on April 11th in particular as that was when it would pass closest to the earth - or 34 years ago this coming Easter Saturday.

In a March 13, 1986 Sydney article 'Australian outback ready to cash in on Halley's return' by Chris Pritchard in the The Christian Science Monitor, it is reported that many are heading south to observe the comet:

Sorry, the Barrow Creek Hotel is full. The 11-room, rough-and-ready establishment insists it will take no more reservations for April, though owner Lance Pietsch says visitors are welcome to camp outside with their sleeping bags. Barrow Creek, a folksy stop (gas station, hotel, post office, general store, and little else) on the long road north from desert-like Alice Springs to tropical Darwin in Australia's vast, empty northern territory, is set to cash in on Halley's comet.

The last time the visitor from outer space passed earth's way was in 1910. This time, the best place to see it is from the Southern Hemisphere. Australia's outback -- far from distracting city lights and easily accessible by scheduled airline service -- is being widely touted as offering the ultimate view.

In southern skies, Halley's will be seen in the morning this month and throughout the night for much of April. Its appearance is causing some of the unlikeliest places in Australia to get ready for tourism booms.

Japanese visitors -- 9,000 of them -- top the list. But 7,000 extra American tourists are coming, too, specifically for the experience. All told, around 20,000 arrivals from overseas are expected.

Robin Hirst, curator of astronomy at Melbourne's Museum of Victoria, hopes they won't be disappointed. It'll be less dazzling, experts say, than in 1910.

But cautious voices from observatories aren't dissuading foreigners. Japan Airlines has special charter flights scheduled for Sydney in early April. The New South Wales town of Bathurst will play host to a tent city for Japanese campers. Japanese astronomy students will be housed in remote farmhouses across the Australian countryside. While waiting for the comet, they'll be given an outdoor ``Aussie'' experience: horseback riding, fence-mending, and sheep round-ups.

In Alice Springs, Northern Territory, older Japanese will be abandoning their customary preferences for high-standard accommodations (now all sold out) and are slated to stay in trailer parks.

Some of their compatriots will camp in remote and eerie Wolf Creek Meteor Crater, a 2 million-year-old phenomenon that rises 100 feet above the otherwise monotonously flat landscape of Western Australia's Kimberley Region. These comet-watchers will pitch their tents surrounded by the sandstone and quartzite walls of the crater.

For tourists canny enough to have made reservations in time, an alternative to land-based observation has proved popular: ships. The Royal Viking Line has four cruises starting in Sydney and Auckland, New Zealand, to points in the South Pacific from where the comet will be viewed in isolated maritime luxury.

How did Australia manage to be at the heart of a tourism boom many of its own officials didn't expect? Research by the American magazine ''Sky and Telescope'' determined that Australia would be the place to be for this once-in-a-lifetime event. Word spread to the travel industry. Promotion of special tours began.

Australians haven't been forgotten: For around $200, they can buy an evening flight on jet airliners from any of a number of major cities. The flight lands at the same point from which it took off. In the two hours in between, there's a celebration dinner, an in-flight lecture from an astronomer, distribution of a souvenir kit that includes a T-shirt and key-ring, and a view of Halley's comet from 30,000 feet.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics, in the Year Book of Australia, 1986, contributes:

AUSTRALIA AND COMET HALLEY, 1985-1986

(This article has been contributed by the Mount Stromlo and Siding Spring Observatories Australian National University)

The return of Comet Halley to the inner solar system during 1985-86 has resulted in the most intensive observational effort ever devoted to a single astronomical object. Australian astronomers, as part of the International Halley Watch network, are playing a major role in this effort.

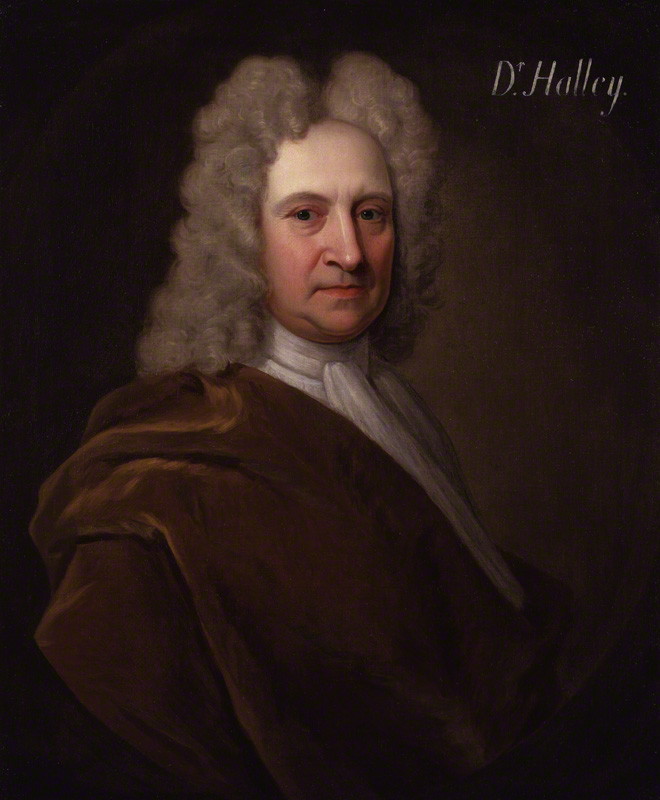

Comet Halley was named in honour of the noted English astronomer and mathematician, Edmond Halley (1656 - 1742) who in 1705 published calculations showing that comets observed in 1531, 1607 and 1682 were really the one comet. He predicted its return in 1758 and it was sighted late that year, passing perihelion (nearest point of orbit to the sun) in March 1759.

Later calculations identify it with the large bright comet seen during the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 and with other comet sightings at intervals of about 76 years from 240BC.

Edmond Halley (1656-1741) - Portrait by Richard Phillips, before 1722

Bright comets have always been a source of wonder, excitement and (in past times) fear: even today the physical and chemical composition of comets is not fully understood. The present apparition of Comet Halley provides an unprecedented opportunity to vastly increase our knowledge of these visitors from the outer limits of our solar system.

Comets are thought to enter the solar system from a vast swarm of primordial debris known as the Oort cloud. This cloud contains the remnants of material from the time of formation of the solar system and is thought to extend about 2 light years (19,000,000,000,000 km) beyond the known planets. Occasionally, about once every 100,000,000 years, another star passes close to the Oort cloud. The gravitational effects of this passage 'scramble' the orbits of the comets and some begin to fall in towards the sun. The comet thus becomes an infalling sample of the solar system's remote past, and by studying it astronomers can learn something of what the conditions were that led to the evolution of the solar system and, ultimately, to human life.

When they first leave the Oort cloud, comets are small bundles of ices (mainly water with traces of hydrocarbon nitrocarbon compounds) and dust. up to a few tens of kilometers in diameter. As they approach the sun. solar radiation heats the comet and the ice and gasses boil out of it. Interaction with the solar wind (the stream of charged particles that flow out of the sun) blows the gasses back from the head of the comet and causes them to fluoresce forming an ion tail which always points away from the sun. Dust particles are also lost from the comet and are strewn along the comet's orbit to form a dust tail which may lie in a different direction to the ion tail. When a comet is close to the sun it thus consists of a head (or nucleus), surrounded by a coma (the bright gasses expelled from the nucleus) and having an ion tail of fluorescent gasses and a dust tail. Also surrounding the nucleus is an immense cloud of atomic hydrogen, coming from the breaking up of water molecules in the coma; this hydrogen cloud may grow to the size of the sun.

Most comets fall into elliptical orbits around the sun, with the sun at one focus and a point in the Oort cloud at the other, returning to the inner solar system at long intervals (up to millions of years). Over several passages this orbit may be severely perturbed by the gravitational effects of the planets, particularly Jupiter, and the comet may become 'trapped' inside the solar system, having a shorter orbital period and never returning to the Oort cloud.

The importance of Comet Halley lies in the fact that it is the only fairly young comet for which the period is accurately known, and which has predictable return dates in the near future. It is therefore possible to plan experiments well ahead of the expected return time. During the current passage, Comet Halley will be studied from ground-based observatories, and from a fleet of spacecraft which will rendezvous with the comet in March, 1986. Australian astronomers have a vital role to play in these observations since during the time when the comet is at maximum brightness during March and April, 1986, and at the time of its closest approach to earth on April 11, 1986, Comet Halley will be far south in the sky, inaccessible to the major observatories in the northern hemisphere.

The CSIRO radio telescope at Parkes, N.S.W. is the vital link in communication with the most complex of the spacecraft, the European Space Agency's GIOTTO, due to pass within 500 km of the comet nucleus on March 13, 1986. GIOTTO carries cameras which may provide our first close-ups of a cometary nucleus, as well as experiments designed to sample the chemistry and magnetic fields inside the comet. Since there is a high probability that GIOTTO will be destroyed during its 'close encounter', all data is instantly transmitted to Parkes, thence to Darmstardt, West Germany, for processing. As well as monitoring the GIOTTO encounter, CSIRO scientists will use the Parkes telescope and their smaller millimeter-wave telescope at Epping, N.S.W., to investigate the hydrogen halo and the molecular compounds present in the comet.

From Mount Stromlo, near Canberra, A.C.T., astronomers of the Australian National University's Mount Stromlo and Siding Spring Observatories will be observing Comet Halley at optical wavelengths using the observatory's 1.9 m and 0.8 m telescopes and advanced technology detectors designed and built at the observatories. Experiments planned from Mount Stromlo concentrate on spectroscopic studies, investigating the detailed physical and chemical make-up of the comet, plus infra-red studies, investigating the complex molecules and dusty compounds in the comet.

At the A.N.U.'s Siding Spring Observatory, near Coonabarabran, N.S.W., no less than eight optical telescopes will be involved in the onslaught on Comet Halley. These telescopes include some of the world's most modern telescopes; the brand-new A.N.U. 2.3 m Advanced Technology Telescope (the ATT), the Anglo-Australian Observatory's 3.9 m reflector (the AAT). and the United Kingdom Science and Engineering Research Council's 1.2 m Schmidt camera.

Experiments planned for the AAT, the largest and best-equipped telescope in the southern hemisphere, concentrate on the detailed structure of the comet. The observations include photography of the comet's head. using both conventional cameras and charge-coupled diode arrays (CCDs). and infra-red spectroscopy, which provides information about the molecules and gasses present in the comet.

The most spectacular photographs of Comet Halley are likely to come from the U.K. Schmidt. This telescope is specially designed to have a wide field of view and will be able to photograph both the head and tail of the comet on the one plate for most of the comet's passage. The Schmidt has been photographically monitoring Comet Halley since August, 1985.

A.N.U. astronomers at Siding Spring will be using six telescopes, ranging in size from the 2.3 m ATT to an ultra-high-speed 20 cm Schmidt camera. A full range of optical investigations is planned; photography, mapping the changing structure of the comet; photometry, monitoring the brightness and colour; polarimetry, investigating the interaction of the comet with the solar magnetic field, and the nature of the dust particles; infra-red observations, studying the molecules and dust; and spectroscopy, the most powerful tool of the astronomer, providing detailed measurements of the physics and chemistry of the comet. Prime telescope will be the 2.3 m. which has the unique facility of being able to change the mode of observation in a matter of seconds, making it possible to run, e.g., spectroscopic and photographic observations practically simultaneously. Coupled with the Mount Stromlo Photon Counting Array, the most advanced light-detecting system in the world, the 2.3 m has a major role to play in the study of Comet Halley.

By the time that Comet Halley leaves the inner solar system toward the end of 1986 the efforts of Australian astronomers will have vastly increased our knowledge of comets, our solar system. and the first steps in the evolution of life.

Australians have long been associated with comet chasing and finding. An early observatory was established in 1788 by William Dawes on Dawes Point, at the foot of Observatory Hill, in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to observe in 1790 the return of a comet suggested by Edmond Halley (not Halley's Comet but a different one). The area was originally known by the Aboriginal names of Tar-ra and Tullagalla. This was later changed to Point Maskelyne in honour of Reverend Dr Nevil Maskelyne, British Astronomer Royal. He sent out the first astronomical instruments which were established at the point in the country's first observatory, by Lieutenant William Dawes (1762-1836), astronomer with the First Fleet. The point was renamed in honour of Dawes.

Sydney looking south from Flagstaff Hill, ca. 1821 by James Taylor, Item: a2850001h courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

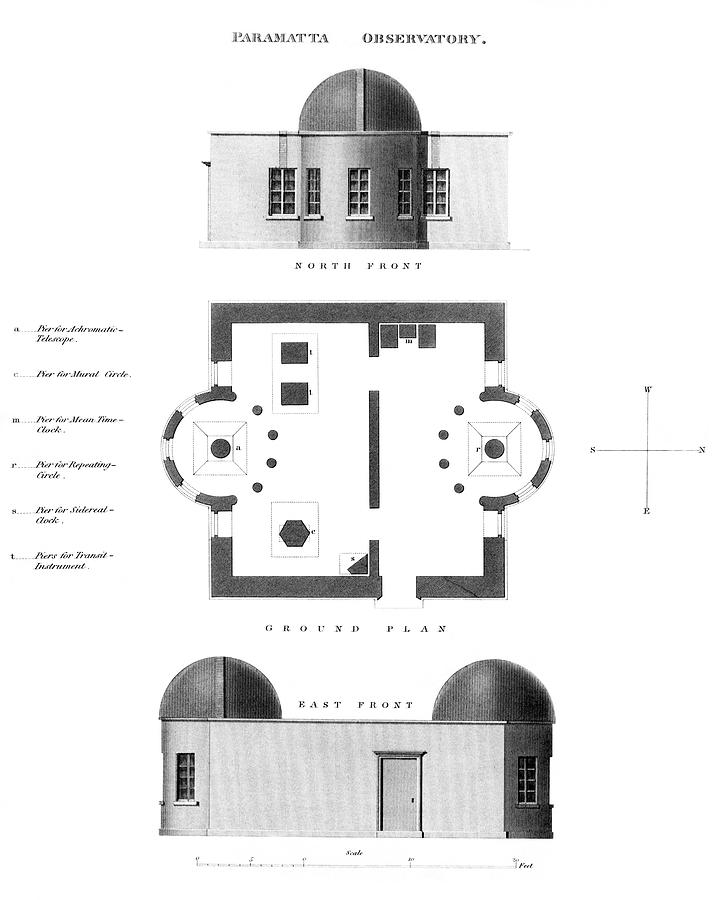

Sir Thomas Brisbane, the sixth governor of New South Wales, established the first private observatory in Australia at Government House in Parramatta after he arrived in the colony in 1821. Two astronomers came out with him, Charles Rumker and John Dunlop. Within months of establishing the observatory, they discovered Encke’s Comet, a short-period comet. It was found on its first predicted return in June 1822. In an article on ‘Progress of the Mathematical Sciences’, the French scientist M. Fourier wrote:

the return of this star is an astronomical event of the greatest interest. Its faint splendour and crepuscular light did not allow it to be observed in Europe. Nor were they more fortunate at the Observatory of the Cape of Good Hope; but it was decried in the region of the earth the most remote from Europe—New Holland. The astronomer of the observatory at Parramatta, the most recent establishment of such a kind, observed this comet throughout the month of June 1822, and in positions very near those which had been anticipated.

This comet, seen previously in 1818 by the astronomer J. Pons in the northern hemisphere, was named after astronomer Johann Franz Encke who had calculated its 3.3-year orbit. The rediscovery of Encke’s Comet was important because it was only the second time that the predicted return of a comet had been observed. The first, as noted above, was Halley’s Comet. This observation made Encke’s Comet a permanent member of the solar system and confirmed that comets, like planets, obeyed Newton’s laws of gravitational motion.

Parramatta Observatory Plans. Plans of the observatory in Parramatta, Sydney, Australia, which was completed in 1822. This observatory was financed completely by Sir Thomas Brisbane, who employed two notable astronomers, Christian Carl Rumker and James Dunlop. By 1825, the locations of 7385 stars had been determined and in 1835, the Catalogue of 7385 stars was published. These plans, drawn by Reverend W. B. Clarke in 1825, published in 1835, show the building's simple structure made of wood and canvas, with two metre sandstone piers. This Observatory was closed in 1847.

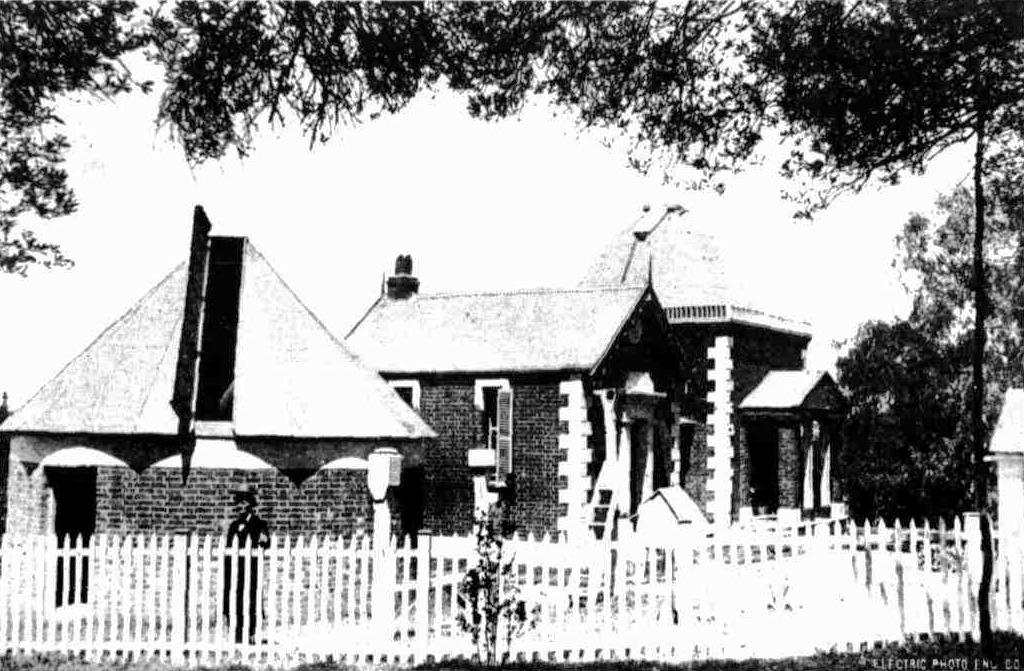

In 1848, a new signal station was built by the Colonial Architect, Mortimer Lewis, on top of the fort wall on Windmill Hill. Then, at the instigation of the Governor, Sir William Denison, it was agreed seven years later to build a full observatory next to the signal station. The first Government Astronomer, William Scott, was appointed in 1856, and work on the new observatory was completed in 1858.

Sydney Observatory (H.C. Russell in doorway), circa 1860 - Russell joined the Sydney Observatory [in 1859] under Rev. W. Scott. In 1862-64 he was acting director and was appointed government astronomer in 1870. Reference: Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol.6 (pp.74-5)GENERAL NOTEDated from the same photograph "Sydney Observatory from the south shortly after completion, about 1860" reproduced in: Sydney Observatory : a conservation plan for the site and its structures / James Semple Kerr. Sydney : Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, c1991. (p.23) Digital order no: a089301, courtesy the State Library of New South Wales.

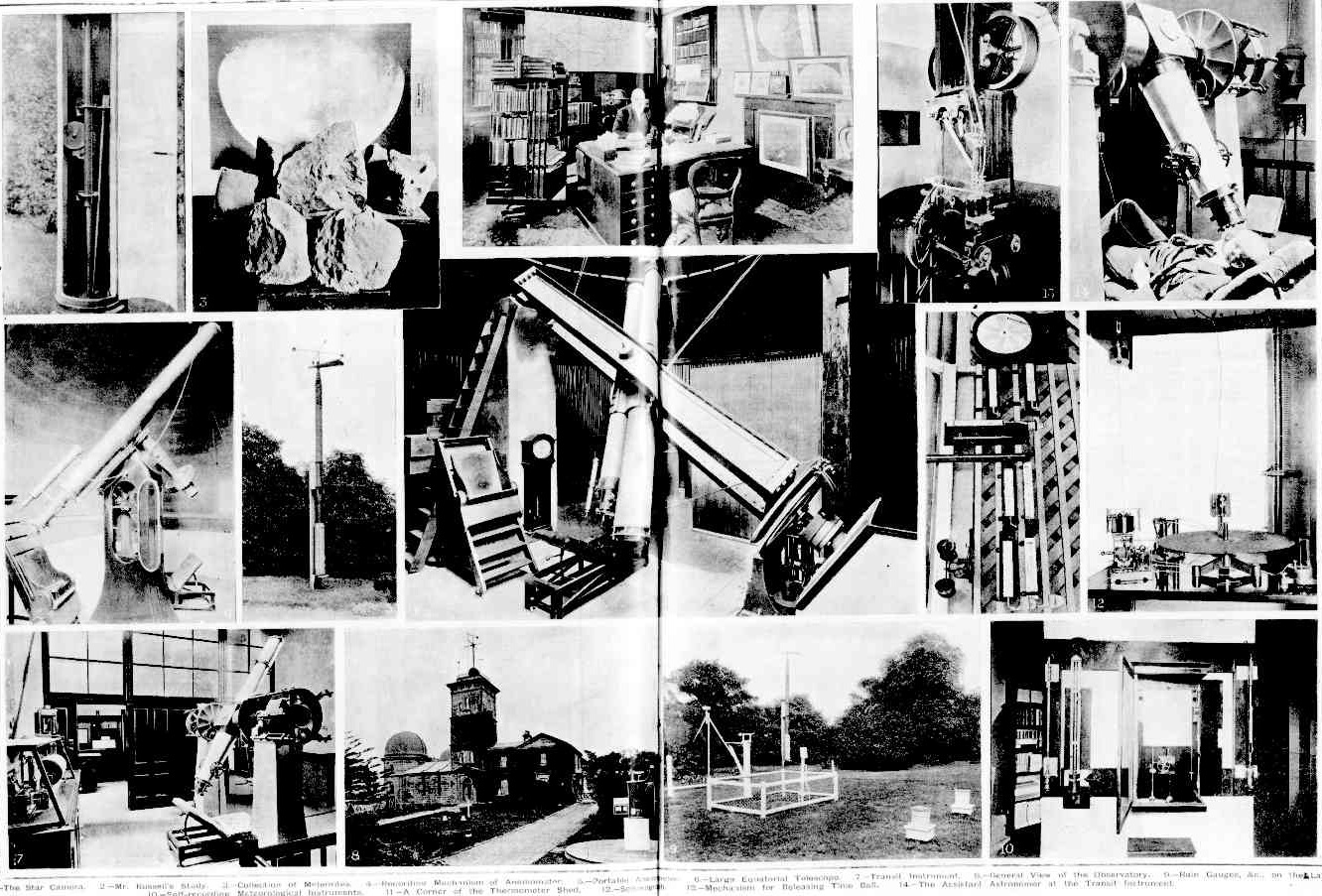

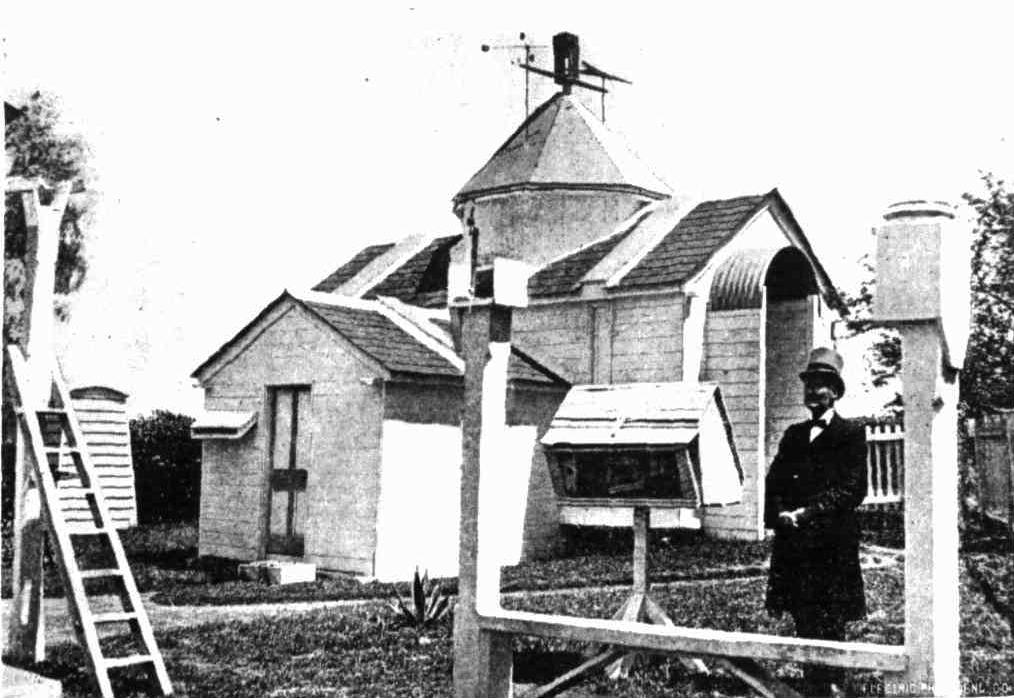

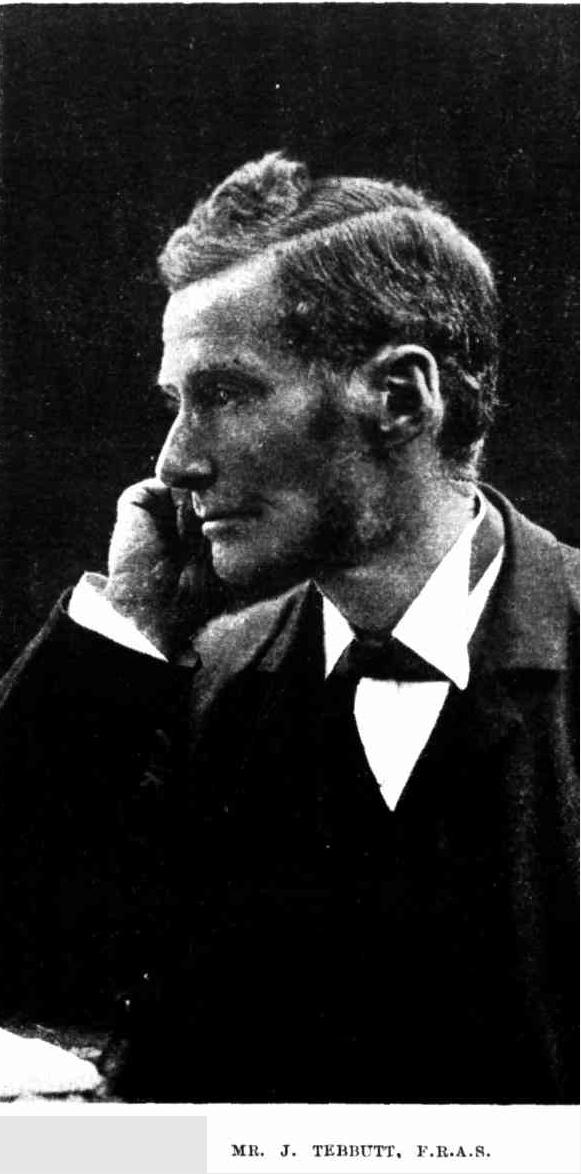

This success was followed by Australia’s those of our most famous nineteenth-century comet hunter, John Tebbutt, whose papers are held at the National Library of Australia. Mr. Tebbutt’s interest in comets began with his first naked-eye observation of a comet in May 1853. His next was Comet Donati, which had been discovered by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Donati in Florence on 2 June 1858.

Becker, Ludwig & Ladd & Carr. (1858). Donati's comet over Flagstaff Hill Observatory, Melbourne, 11 October 1858 Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152709026

Mr. Tebbutt then shot to international fame with the discovery of the Great Comet of 1861 on May 13th of that year - this one passing closet to the earth on June 30th. He wrote in his memoirs that this discovery ‘made him known to the astronomers of the northern hemisphere’.

Great Comet of 1861, also known as C/1861 J1 or comet Tebbutt; drawing by E. Weiss, created in 1881

His next great discovery and international exposure took place in 1881. C/1881 K1 (also called the Great Comet of 1881, Comet Tebbutt, 1881 III, 1881b) is a long-period comet discovered by John Tebbutt on May 22nd, 1881 at Windsor, New South Wales. It is called a great comet because of its brightness at its last apparition.

In his Astronomical Memoirs in the section entitled 1881, John Tebbutt gave an account of his discovery:

This year, like 1861, was signalised by the discovery of a great comet. While scanning the western sky with the unassisted eye on the evening of May 22, I discovered just below the constellation Columba a hazy looking object which, from my familiarity with that part of the heavens, I regarded as new. On examining it with the small marine telescope previously referred to in these memoirs, I found it to consist really of three objects, namely, two stars of the 41⁄2 and 51⁄2 magnitude afterwards identified at γ1 and y2 Cæli, and a head of a comet. I could not find any trace of a tail, but on the 25th it exhibited a tail about two degrees in length. Immediately on its discovery I obtained, with the 41⁄2 equatorial, eight good measures of the nucleus from one of the bright stars just mentioned. On the following day I notified the discovery to the Government Observatories at Sydney and Melbourne. A series of filar micrometer comparisons was obtained at Windsor, extending from the date of discovery to June 11, when the comet disappeared from our morning sky and became an object for the northern observatories. …

The great comet of 1881 (Comet C/1881 K1). Observed on the night of June 25-26 at 1h. 30m. A.M. (Plate XI from The Trouvelot Astronomical Drawings 1881) by Étienne Léopold Trouvelot - MLibrary Digital Collections

In her monumental work on the history of nineteenth-century astronomy, Agnes Clerke wrote that ‘the comet of 1881 was of signal service to science … Cometary photography came to its earliest fruition with it’.

_b_501_1.jpg?timestamp=1585879962902)

The great comet of 1881, image published in Die Gartenlaube (the first successful mass-circulation German newspaper and a forerunner of all modern magazines)

For his extraordinary work, Tebbutt was awarded the Hannah Jackson (nee Gwilt) Gift and the Bronze Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1905. In 1973, the International Astronomical Union renamed the lunar crater Picard G ‘Tebbutt’. In 1984, Tebbutt and his observatories were depicted on the new Australian $100 note.

Back of the $100 banknote, showing John Tebbutt, with watermark of Captain James Cook - Concept design by Harry Williamson, first issued in 1984

Of course, the collecting of Art associated with Astronomy and even Astronomy Photographs (known as Astrophotography) has become more popular in recent years with the advent of equipment that captures and highlights that wheeling night sky above landmarks or simply shows galaxies and star groups.

April is also a great time to commence looking for the Aurora Australis, or Southern Lights as the skies shift towards Winter with between March and September noted as peak times and Tasmania, Antarctica and Victoria the best places to see them - although you can see them while in New South Wales if somewhere out of Sydney where urban light won't interfere - The Dark Sky Park for instance in the Warrumbungle National Park. Such great images are being captured of the Aurora Australis that in recent years Hobart has hosted an annual exhibition of these works and some are even sold to those who love collecting these images, for great prices.

It's a great time of the year to remind yourself, with the first possum grunt, microbat flit or owl hoot that the universe is available to be seen when the sun slides behind the western horizon. You may even discover your very own comet or galaxy!

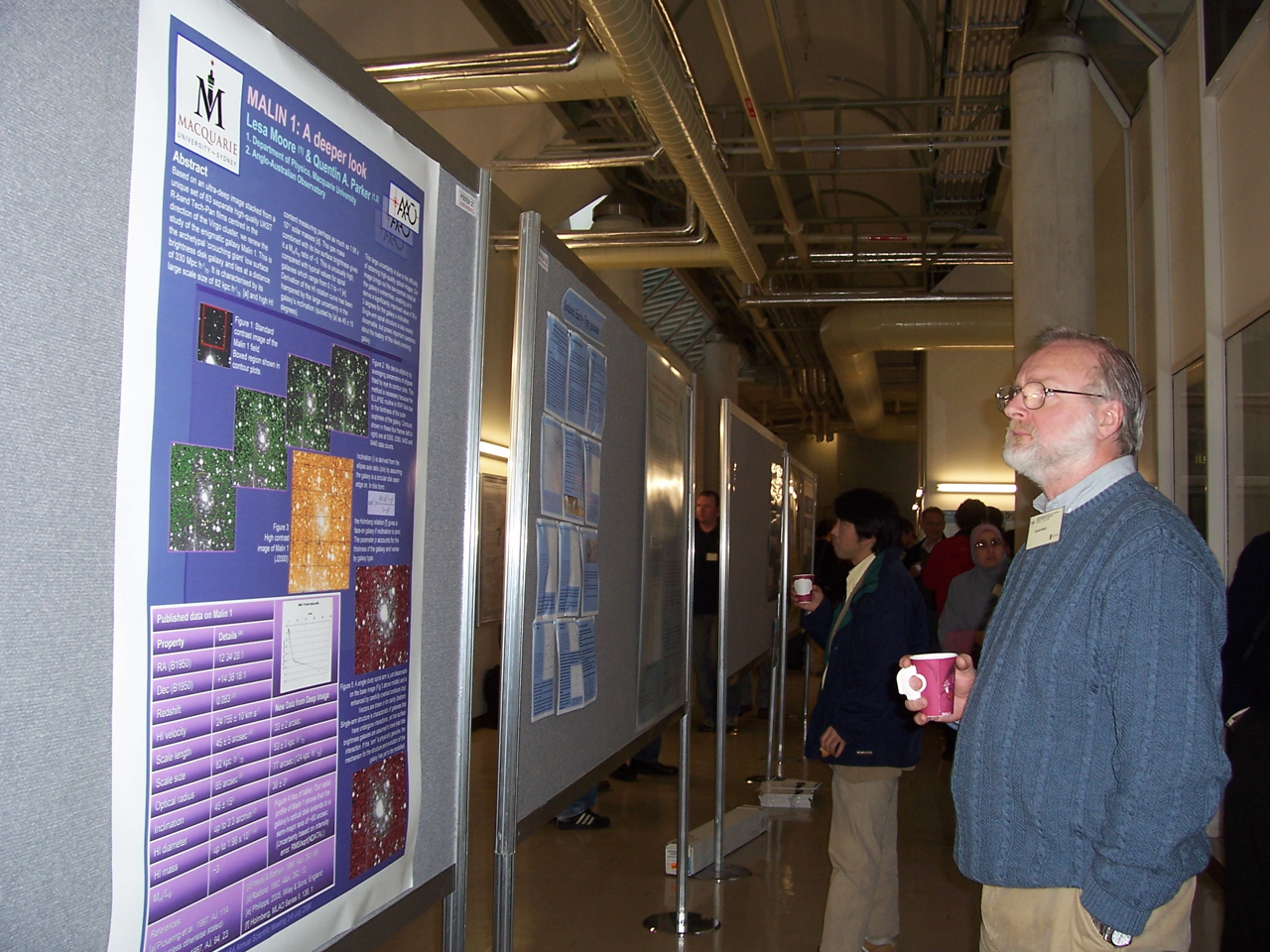

David Malin looking at a poster about Malin 1, the first galaxy to be discovered by him. Photo taken in 2006 by 'Catherine' (?)

Malin 1 is a giant low surface brightness (LSB) spiral galaxy. It is located 1.19 billion light-years (366 Mpc) away in the constellation Coma Berenices, near the North Galactic Pole. As of February 2015, it is the largest known spiral galaxy, with an approximate diameter of 650,000 light-years (200,000 pc), thus over three times the diameter of our Milky Way. It was discovered by astronomer David Malin in 1987 and is the first LSB galaxy verified to exist. Its high surface brightness central spiral is 30,000 light-years (9,200 pc) across, with a bulge of 10,000 light-years (3,100 pc). The central spiral is a SB0a type barred-spiral. Malin 1 is peculiar in several ways: its diameter alone would make it the largest barred spiral galaxy ever to have been observed.

View of the town of Parramatta from May’s Hill - circa 1840, attributed to George Edwards Peaccock, Item: a128026h, courtesy the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

State Library of NSW Curator states:

It was rare for artist George Peacock to move away from his usual subject of Sydney Harbour, however this view looks down on Parramatta from Mays Hill. It is likely to have been painted during the brief period in 1839 when Peacock was being trained as a weather observer at the Parramatta Observatory. Old Government House, at the left, looks over Pitt and Hunter streets, and the centre of the town of Parramatta. In the lower right corner, someone has erroneously signed the painting ‘Allport’ — another well-known colonial artist — presumably as a crude attempt to pass it off as a work by a more respected artist.

The 2020 CWAS "David Malin Awards"

Proudly supported by CSIRO's Astronomy and Space Sciences, The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences and Canon Australia.

The Central West Astronomical Society is proud to announce the 2020 CWAS Astrophotography Awards judged by Dr David Malin - the "David Malin Awards".

Click here to see the Conditions of Entry.

This year's competition continues to build on the experience of previous years to help make it the premier competition of its kind in Australia. The competition this year will have three sections of entry - General Section, Open Themed Section and a Junior Section (18 or younger). The general section is divided into five categories; Wide-field (camera shots), Deep Sky (telescope shots), Solar System, Nightscapes and Animated Sequences. The Animated Sequences category has two subsections - Scientific and Aesthetic. The Junior Section will have one open category and entries can be of any astronomical subject, and can be an animated sequence.

The Competition Structure:

General Section:

- Wide-Field

- Deep Sky

- Solar System

- Nightscapes

- Animated Sequences

- Scientific

- Aesthetic

- Junior Section (18 or younger) - One Open Category (can be of any astronomical subject)

- Open Themed Section - "Astrophotography with your Smartphone"

- The "David Malin Innovation Prize" may be awarded, at Dr Malin's discretion, for a striking astronomical image that shows exceptional imagination, innovation or an unusual approach in any of the categories.

- An additional prize, "The Photo Editor's Choice", will also be awarded. This will be judged by a major news organisation's photo editor or editors.

The Solar System category is for images of solar system objects taken with a telescope. Wide-field solar system shots may be entered in the Wide-Field or Nightscape categories depending on the subject and composition.

The Nightscapes is intended to showcase the increasing popularity and evolution of this relatively new genre of astrophotography, combining beautiful terrestrial foregrounds with a night sky scene - often in a single exposure (HDR is OK) or as a multi-shot panorama.

Animated Sequences should be videos that are intriguing or highlight concepts and events not obvious or significant in stills. Astrophotographers are invited to submit animations, produced as either time-lapse sequences or with other forms of video. They can be of any subject, provided there is a distinct astronomical link. This category will have two subsections - Scientific and Aethestic. Scientific animations are short sequences that have an obvious scientific purpose, perhaps changes in the appearance of a planet, comet or other celestial body, or where the footage was used for the timing of a transit, an occultation, or even in studying dome seeing. These sequences usually require great skill and/or perseverance in first obtaining the data and then in collating them to reveal an aspect of scientific merit. Aesthetic sequences are animations that are aesthetically pleasing in some way, where the use of appropriate music and editing is encouraged, but always with a strong astronomical component. Scientific animations should be silent and be less than one minute in duration. Aesthetic animations must not exceed two minutes in runtime. All animations must be submitted as MOV, MPEG, AVI or MP4 files.

The Open Themed Section is open to all astrophotographers. They are encouraged to see who can be the most inventive and creative in evoking the theme, which this year will be "Astrophotography with your Smartphone". Smart phones are everywhere and some are capable of impressive low light-level photography. We are looking for images that have been taken with a smartphone of an astronomical scene that has some aesthetic appeal and/or that has captured something you might not expect to see from such a tiny camera.

All entries must be images that faithfully reflect and maintain the integrity of the subject. Entries made up of composite images taken at different times, different locations or with different cameras are not acceptable. Image manipulations that produce works that are more "digital art" than true astronomical images, will be deemed ineligible.

All still images must be submitted as digital files via a dedicated web site that can be accessed at this web address. For judging purposes, still images must be submitted as JPG files with the longest side having a dimension no greater than 4,950 pixels. All images must be in Adobe 1998 RGB colour space and will be judged using a calibrated monitor. Similarly, winning images will be printed from the files as-received, so it would be prudent for entrants to calibrate their monitors if possible. It does make a difference. Click here for an example of a very detailed set of calibration procedures for all platforms. For Mac users, a useful monitor calibration program can be found under "Monitors" in System Preferences, and the ideal solution for monitor calibration is a stand-alone device such as the Spyderexpress.

Submission of entries will be accepted from Wednesday, 1 April 2020, and will close at 24:00 (AEST) on Tuesday, 30 June 2020. Entrants must register in advance. This can be done from 1 April from the Submit Entries link on this page.

Entry payments can be made by cheque, money order or direct deposit. For the entries to be accepted, the payments must be received by the deadline. Entry fees are $15 per entry. Payment details will be presented following each entry submission.

The photographs will be judged by world-renowned astrophotographer, Dr David Malin. During the course of the judging process, Dr Malin may invite, at his discretion, the views of other distinguished international astronomers to aid him in his deliberations, with Dr Malin's decisions being final.

All entries will be judged without David being aware of the identity of the photographer, and to preserve anonymity, the submitted image files should not contain identifying metadata. The winners will be notified and presented with the "David Malin Awards" during a special ceremony at the CSIRO Parkes Observatory in the presence of invited dignitaries on a date to be announced. All winners are required to make every effort to attend the presentation of the awards.

A selection of the finest astrophotographs received will be professionally printed courtesy of Canon Australia by Sunstudios and exhibited for the entire year at the CSIRO Parkes Observatory's Visitors Centre. In addition, a second set will tour the country in a travelling exhibition, organised by the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, to selected venues beginning with Sydney Observatory.

There is a limit of five (5) entries per category per photographer. All photographs must have been taken no more than 2 years before the closing date of entry, and no re-entries from previous DMA competitions will be accepted. All entries must be submitted in electronic form via the dedicated submissions web site. The entrants must provide brief details of the equipment, exposure times, processing and, where relevant, the location where the image was taken.

It is not just technical skill that David Malin will be looking for, but an aesthetically pleasing picture that reflects and captures the beauty, inspiration and interest of astronomy. All images will be judged by these criteria.

Canon Australia is supporting the competition with significant prizes.

Finals Judge: Dr David Malin

Presentation Ceremony for the 2020 CWAS "David Malin Awards" to be held at the CSIRO Parkes Observatory on a date to be announced.

Entries close at 24:00 (AEST) on Tuesday, 30 June 2020.

Visit: https://www.parkes.atnf.csiro.au/news_events/astrofest/DMA/

Kate Burness was born in Australia in 1947, grew up in the country, then the outer suburbs of Sydney, attended the National Art School in the inner city there from 1963-1967 majoring in Commercial Illustration & Graphic Design.

From her website Bio:

On graduating I worked as an illustrator and art director for a national magazine publishing company and then traveled overseas for 4 years, crossing Asia to the U.K. and Europe.

I have been a professional artist and illustrator in Britain and Australasia for all of my adult life. My work has been published in children's books, on posters, greeting cards, place mats, packaging, as well as in national advertising campaigns. I have also had various exhibitions over the years, and am represented in collections in Australia, New Zealand, the U.K., U.S.A. and Europe.

In 1986, while living in the Blue Mountains of Australia, west of Sydney, my husband Bob Anderson and I started Blue Moon Cards Pty Ltd. We published high quality artist illustrated greeting cards, postcards and prints, unique in the country at that time. From small beginnings the company grew dramatically, and by 1994 we were publishing 27 artists on a royalty basis, and servicing over 1500 retail outlets!

In November 1996, after a personal tragedy, we sold Blue Moon, and moved to the South Island of N.Z.

New Zealand has become my home, and I have come to love its unique landscape, its diversity and accessibility. Having moved from my small organic property, Golightly Farm, in the Motueka Valley, I now live as simply and sustainably as I can in Takaka in the beautiful Golden Bay at the top of the NZ's South Island.

Bob died in March 2012. He was the Love of my life, and I was in deep grief for a long time. I am ready to come back into the world now, and make my work available to a new audience and generation, as I feel it is timeless and universal. Today's technology allows me to do that.

I continue to paint in my simple studio here in Takaka, and draw my inspiration from the natural world, and my own imagination.

Visit: www.kateburnessart.com

Trove - National Library of Australia

David Malin Website: https://www.davidmalin.com/

Sky Events To Watch Out For In 2020

April 22, 2020, before dawn, the Lyrids: The Lyrid meteor shower – April’s shooting stars – lasts from about April 16 to 25. About 10 to 15 meteors per hour can be expected around the shower’s peak, in a dark sky. The Lyrids are known for uncommon surges that can sometimes bring the rate up to 100 per hour. In 2020 the peak viewing hours to take place in the dark hours before dawn April 22, with no moon to ruin the show.

May 5, 2020, before dawn, the Eta Aquariids: This meteor shower has a relatively broad maximum; you can watch it the day before and after the predicted peak morning of May 5. The shower favours the Southern Hemisphere and is often that hemisphere’s best meteor shower of the year. The radiant is near the star Eta in the constellation Aquarius the Water Bearer. The radiant comes over the eastern horizon at about 4 a.m. local time; that is the time at all locations across the globe. For that reason, you’ll want to watch this shower in the hour or two before dawn, no matter where you are on Earth.

Late July 2020, before dawn, the Delta Aquariids: Like the Eta Aquariids in May, the Delta Aquariid meteor shower in July favors the Southern Hemisphere and tropical latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere. These faint meteors appear to radiate from near the star Skat or Delta in the constellation Aquarius the Water Bearer. The maximum hourly rate can reach 15 to 20 meteors in a dark sky. The nominal peak is around July 27-30, but, unlike many meteor showers, the Delta Aquariids lack a very definite peak. Instead, these medium-speed meteors ramble along fairly steadily throughout late July and early August. An hour or two before dawn usually presents the most favourable view of the Delta Aquariids. At the shower’s peak on or near July 28, 2020, the rather faint Delta Aquariid meteors will be best seen in the predawn hours, after the moon has set.

Late evening to dawn on August 11, 12 and 13, 2020, the Perseids: The Perseid meteor shower is perhaps the most beloved meteor shower of the year for those in the Northern Hemisphere. These swift and bright meteors radiate from a point in the constellation Perseus the Hero. As with all meteor shower radiant points, you don’t need to know Perseus to watch the shower; instead, the meteors appear in all parts of the sky. These meteors frequently leave persistent trains. Perseid meteors tend to strengthen in number as late night deepens into midnight, and typically produce the most meteors in the hours before dawn. In 2020, the peak night of this shower will be somewhat marred by the last quarter moon, although the brighter Perseids will likely overcome the moonlit glare. Predicted peak in 2020: the night of August 11-12, but try the nights before and after, too, from late night until dawn.

October 7, 2020, nightfall and evening, the Draconids: The radiant point for the Draconid meteor shower almost coincides with the head of the constellation Draco the Dragon in the northern sky. That’s why the Draconids are best viewed from the Northern Hemisphere, although keen astronomers will also spot them from here. The Draconid shower is a real oddity, in that the radiant point stands highest in the sky as darkness falls. That means that, unlike many meteor showers, more Draconids are likely to fly in the evening hours than in the morning hours after midnight. This shower is usually a sleeper, producing only a handful of languid meteors per hour in most years. But watch out if the Dragon awakes! In rare instances, fiery Draco has been known to spew forth many hundreds of meteors in a single hour. In 2020, watch the Draconid meteors at nightfall and early evening on October 7. Try the nights of October 6 and 8, too. Fortunately, the waning gibbous moon won’t rise till late evening, providing moon-free viewing for several hours after nightfall.

October 21, 2020, before dawn, the Orionids: On a dark, moonless night, the Orionids exhibit a maximum of about 10 to 20 meteors per hour. More meteors tend to fly after midnight, and the Orionids are typically at their best in the wee hours before dawn. These fast-moving meteors occasionally leave persistent trains. The Orionids can sometimes produce bright fireballs. In 2020, the waxing crescent moon sets in the evening, providing moon-free viewing for rest of the night. With no moon to ruin the show, try watching the Orionids in the hours before dawn on October 21 and 22.

Late night November 4 until dawn November 5, 2020, the South Taurids: The meteoroid streams that feed the South (and North) Taurids are very spread out and diffuse. Thus the Taurids are extremely long-lasting (September 25 to November 25) but usually don’t offer more than about five meteors per hour. The Taurids are, however, well known for having a high percentage of fireballs, or exceptionally bright meteors. Plus, the two Taurid showers – South and North – augment each other. In 2020, the expected peak night of the South Taurid shower happens when a waning gibbous moon lights up the sky almost all night long. Peak viewing is just after midnight. The South and North Taurid meteors will continue to rain down throughout the following week, but with more interference from the waxing gibbous moon.

Late night November 11 until dawn November 12, 2020, the North Taurids: Like the South Taurids, the North Taurids meteor shower is long-lasting (October 12 – December 2) but modest, and the peak number is forecast at about five meteors per hour. The North and South Taurids combine to provide a nice sprinkling of meteors throughout October and November. Typically, you see the maximum numbers at around midnight, when Taurus the Bull is highest in the sky. Taurid meteors tend to be slow-moving, but sometimes very bright. In 2020, the slender waning crescent moon – rising in the wee hours before dawn – won’t seriously intrude on the peak night of November 11 (morning of November 12).

November 17, 2020, before dawn, the Leonids: Radiating from the constellation Leo the Lion, the famous Leonid meteor shower has produced some of the greatest meteor storms in history – at least one in living memory, 1966 – with rates as high as thousands of meteors per minute during a span of 15 minutes on the morning of November 17, 1966. On that beautiful night in 1966, the meteors did, briefly, fall like rain. Some who witnessed the 1966 Leonid meteor storm said they felt as if they needed to grip the ground, so strong was the impression of Earth ploughing along through space, fording the meteoroid stream. The meteors, after all, were all streaming from a single point in the sky – the radiant point – in this case in the constellation Leo the Lion. Leonid meteor storms sometimes recur in cycles of 33 to 34 years, but the Leonids around the turn of the century – while wonderful for many observers – did not match the shower of 1966. Like many meteor showers, the Leonids ordinarily pick up steam after midnight and display the greatest meteor numbers just before dawn, for all points on the globe. In 2020, the moon will display a waxing crescent phase, and set at early evening, to provide moon-free skies nearly all night long. The expected peak night is from late night November 16 till dawn November 17. The Leonids tend to produce the most meteors in the predawn hours, at which time the moon will be long gone.

December 13-14, 2020, mid-evening until dawn, Geminids: Radiating from near the bright stars Castor and Pollux in the constellation Gemini the Twins, the Geminid meteor shower is one of the finest meteors showers in the Northern Hemisphere (though still visible, at lower rates, in the Southern Hemisphere). The meteors are plentiful, rivalling the August Perseids. They are often bold, white and bright. On a dark night, you can often catch 50 or more meteors per hour. The greatest number of meteors fall in the wee hours after midnight. In 2020, the peak of the shower almost coincides with new moon, providing dark skies all night long. Watch the usually reliable and prolific Geminid meteor shower from mid-evening December 13 until dawn December 14, with absolutely no moonlight to ruin the show.

December 22, 2020, before dawn, the Ursids: Die-hard meteor watchers in the Northern Hemisphere watch for Ursid meteors about a week after the Geminids. This low-key meteor shower is active each year from about December 17 to 26. The Ursids usually peak around the December solstice, perhaps offering 5 to 10 meteors per hour during the predawn hours in a dark sky. This year, in 2020, the first quarter moon will set in the evening, providing dark skies at late night and the morning hours.

AN unusual catch by George Turner at the Manly A.F.A. picnic at the Basin, Pittwater, last Sunday, was a stargazer. This species has a wide mouth and two prominent eyes on top of the head. It is not an edible fish. FOUND A STARGAZER (1937, February 14). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 52. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article230785504

In 1705, applying historical astronomy methods, Halley published Astronomiae cometicae synopsis, which stated his belief that the comet sightings of 1456, 1531, 1607, and 1682 were of the same comet, which he predicted would return in 1758. Halley did not live to witness the comet's return, but when it did, the comet became generally known as Halley's Comet.

An early observatory was established in 1788 by William Dawes on Dawes Point, at the foot of Observatory Hill, in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to observe in 1790 the return of a comet suggested by Edmond Halley (not Halley's Comet but a different one). The area was originally known by the Aboriginal names of Tar-ra and Tullagalla. This was later changed to Point Maskelyne in honour of Reverend Dr Nevil Maskelyne, British Astronomer Royal. He sent out the first astronomical instruments which were established at the point in the country's first observatory, by Lieutenant William Dawes (1762-1836), astronomer with the First Fleet. The point was renamed in honour of Dawes.

This was followed by that built by Governor Brisbane at Parramatta and completed in 1822.

THE ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATORY AT PARRAMATTA

Mr. James Dunlop's appointment to the charge of the Government Observatory at Parramatta, is announced elsewhere. In so ample a field as this hemisphere presents for astronomical research, it is shameful to reflect on the little encouragement which that sublime study meets with, at the hands of the Colonists themselves, or has met with at the hands of their late gothic rulers. — Of Mr. Dunlop, it is enough for us to know that he was patronised by Sir Thomas Brisbane, to presume that he is a fit sort of person to discharge the important trust confided to him, at least with credit to himself, if not very great advantage to science. As an optician, we believe, he ranks high in the order of mechanical skill. But we do not mean to undervalue Mr. D.'s abilities, when we say there is a something more than manual skill and sublunary talent — there is a " sacra fames"— an sacred thirst after abstruse investigation — a degree of mental sublimity — a sprinkling of Newtonian philosophy needed to make up the " astronomer." Sydney (or Parramatta) is geographically situated to be one day to the eastern new world, what Greenwich is and long has been to the old. The services of such a man as Mr. Rumker, therefore, we can not help considering highly desirable, that is to say, in conjunction with Mr. Dunlop. Indeed, without sufficient competent help, we cannot expect that Mr. Dunlop, with all his skill and zeal, should throw any great light on those hidden treasures of science, which these southern regions reveal to the searching eye of the astronomer, or to the refining touch of the alchymist. No doubt, if the succeeding Government be of a philosophic turn, the reason of what we have premised, will be shewn by the selection of competent assistants at the Parramatta Observatory. THE ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATORY AT PARRAMATTA. (1831, November 25). The Australian (Sydney, NSW : 1824 - 1848), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36865831

In 1848, a new signal station was built by the Colonial Architect, Mortimer Lewis, on top of the fort wall on Windmill Hill. At the instigation of the Governor, Sir William Denison, it was agreed seven years later to build a full observatory next to the signal station. The first Government Astronomer, William Scott, was appointed in 1856, and work on the new observatory was completed in 1858.

The most important role of the observatory was to provide time through the time-ball tower. Every day at exactly 1.00 pm, the time-ball on top of the tower would drop to signal the correct time to the city and harbour below. At the same time a cannon on Dawes Point was fired, later the cannon was moved to Fort Denison. The first time-ball was dropped at noon on 5 June 1858. Soon after the drop was rescheduled to one o'clock. The time-ball is still dropped daily at 1pm using the original mechanism, but with the aid of an electric motor, not as in the early days when the ball was raised manually.

Sir William Thomas Denison KCB (3 May 1804 – 19 January 1871) was Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen's Land from 1847 to 1855, Governor of New South Wales from 1855 to 1861, and Governor of Madras from 1861 to 1866. According to Percival Serle, Denison was a man of high character and a good administrator. In his early days in Tasmania he spoke too frankly about the colonists in communications which he regarded as confidential, and this accentuated the feeling against him as a representative of the colonial office during the anti-transportation and responsible government movements. He showed great interest in the life of the colony, and helped to foster education, science and trade, during the period when Tasmania was developing into a prosperous colony. In New South Wales his task was easier

OBSERVATORY.

I heard with some regret a few years ago that the Observatory at Parramatta had been broken up. I am aware that this was in a great measure due to the misconduct of the person then acting as astronomer, in consequence of which some doubt was thrown upon the correctness of his observations, and consequently on the value of the results deduced from them. This was, perhaps, a sufficient reason for the withdrawal by the Home Government of the allowance granted to an observer in these latitudes ; but there are many circumstances which would, in my opinion, make it very advisable to re-establish the Observatory, not on its old site, but upon one in the immediate vicinity of Sydney.

In the first place, proevision has already been made for the erection of a building to contain the machinery of a time ball, and for the purchase of the machinery, but the time ball will, in point of fact, be worse than use-less, unless there are means for determining the time correctly-that is, unless there are proper clocks and proper instruments for determining the time, and these instruments are in the hands of the observer responsible to the Government for their proper application. I say that a time ball would be worse than useless without those, for as the time ball is established for the purpose of enabling captains of vessels to rate their chronometers properly, any error in the time given by the ball has the effect of deceiving the captain as to the quality of his chronometer, and as to the daily rate at which it either loses or gains ; and a very trilling error in the rate, accumulating daily, will, in the course of a month, amount to a serious error in time, and a still more serious one in longitude.

In the second place I am anxious for the establishment of an Observatory in the immediate vicinity of Sydney, as affording to all persons, and especially to those educated at the University, a practical example of the application of science to the determination of matters altogether beyond the scope of our ordinary or uneducated reason.

The student sees in the results deduced from observation, the application of those truths or principles which have been put before him at school in an abstract form ; and he begins to comprehend that what he has hitherto been engaged in is to be looked upon in the light of an apprenticeship, during which he has learnt to handle the tools which he will from henceforth have to apply to the purposes of life.

In the third place, I am desirous to establish an Observatory for the purpose of connecting it with the trigonometrical survey of the country, and thus, by means of the perfect and absolute determination of the position on the earth's surface of one point, to be enabled to lay down with perfect accuracy the whole of the remainder of the country, not merely with relation to that spot, but with relation to tho remainder of the earth's surface.

In the fourth place, I am anxious for the establishment of an Observatory as a means of connecting this colony with the scientific societies of Europe and America. I have no doubt but that from my acquaintance with the Astronomer Royal I shall be able to obtain from him a recommendation of a person thoroughly qualified to take charge of the Observatory; and we can then procure assistants from the youth of the colony, some of whom will be trained up to take the place hereafter of the astronomer at first supplied from England.

The instruments in our possession already are of great value, and, I believe, only require to be properly adjusted to allow of their employment at once ; provision should be made for a building to contain them ; for such repairs as may be found necessary to the instruments themselves ; for a house for the astronomer in the immediate vicinity of the Observatory, and such additional accommodation for computers, &c., as may probably be required. It would also be desirable to provide for the purchase of a dozen sets of meteorological Instruments for the purpose of establishing different points throughout the extensive area of the colony, and such observations as to temperature, moisture, direction of wind, and generally of such atmo-spheric phenomona as may afford data from which we may be enabled at some future period to deduce the laws upon which these phenomena depend, or by which they are regulated.

(Signed) W. DENISON. 31st March, 1855. OBSERVATORY. (1855, June 27). Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1875), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60181005

Chant, J. J & Tweedie, W. M. (1863). His Excellency Sir William Thomas Denison, K.C.B. &c. &c., Colonel of the Royal Engineers & formerly Governor General of the Australian colonies Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140403432

FIRE AT PARRAMATTA.

OLD GOVERNMENT HOUSE PARTIALLY GUTTED.

Parramatta, Wednesday.— At about half-past 1 o'clock this morning a fire broke out in the stable connected with the old t Government House, Parramatta. The names quickly communicated with the adjoining outbuildings'which in the old days were used as soldiers quarters, and a great blaze quickly ensued. The Parramatta fire brigades were communicated with in a prompt manner, but before water could be got in play the names had secured a firm hold, and the outbuildings were completely wrecked, several narrow escapes occurring among the boarders who occupied the rooms. The Granville and Rookwood 'brigades subsequently put in an appearance, and under the direction of Captain Love, did their utmost to suppress the names, but despite all efforts the outbuildings and the greater part of their contents were destroyed. Captain M'Crae, an old identify over 80 years of age, had slept in one of the buildings destroyed till a few days back. The damage is estimated at £300, which will be considerably reduced by insurance.

Old Government House was one of those buildings usually described as historic landmarks. It stood on a hill in Parramatta Park, overlooking that pleasing enclosure in one direction, and the town in another. It was erected by Australia's first Governor.Captain Phillip, soon after the foundation of the colony, and was the home of each succeeding Governor till the days of Sir Charles Fitzroy. Lady Bourke, wife of Governor Bourke, died there, and Lady Mary Fitzroy was brought to it dead after being killed at the foot of the hill on which it stands.

Within a few yards of the building are stones marking the place of the old Government Observatory founded in 1822 and closed in 1847, in December of which year Lady Mary Fitzroy was killed. The establishment of Government House in Sydney and the removal thither of the vice-regal court of the olden times made the old house useless for state purposes, and it sank in rank till it became what it has been for many years now, a popular boarding-house, under the lesseeship of Mr. Bishop.

It has many peculiarities that were interesting to visitors, apart from its historic associations. The rooms were large and lofty, and had an old-fashioned air of comfort about .them. Owing to the double storey and immense thickness of its walls the building was cool in the hottest summer's day. The centre walls were no less than 3ft 6 in thick. Every doorway was provided for the action of double doors. The rafters and flooring were as sound yesterday as when first put down, although 105 years old. The back yard is paved with bricks three or four thicknesses in alternate layers. Cellars extended throughout nearly the entire basement of the house. - The old houses which held the hogsheads and the stone wine bins were relics of the luxury of the good old times, it used to please Mr. Bishop greatly to act as cicerone to visitors and discount on the history of the building, and there are few of Parramatta's old identities unable to supply some story respecting the venerable old edifice that has now been reduced to ashes.

Old Government House, Parramatta.

FIRE AT PARRAMATTA. (1893, August 30). Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article113726991

James Dunlop, the superintendent of the government observatory at Parramatta (he was Australia's first official astronomer) who discovered a comet in 1833.

DIED,. At Bora Bora, Brisbane Water, on the 22nd instant, James Dunlop, Esq., late Astronomer of the Royal Observatory, Parramatta, aged 53 years, much regretted by all who knew him. Family Notices (1848, September 27). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12902643

DEATH.

On 22nd October last, aged 67, at Borra Borra, Brisbane Water, Jane Dunlop, widow of the late James Dunlop, Astronomer Royal. Family Notices (1859, November 2). Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1875), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article64092281

Deaths.

LENEHAN — On Saturday, May 2, Henry A. Lenehan. Government Astronomer, aged 65 years. R.I.P. Family Notices (1908, May 3). Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW : 1895 - 1930), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article126748035

BARFF.---June 10 at her residence, Cotham, 30 Newcastle-street, Rose Bay, Jane Foss, wife of the late Henry Ebenezer Barff, Esq., C.M.G., sometime Warden and Registrar of the University of Sydney and daughter of the late H. C. Russell, Esq., C.M.G., sometime Government Astronomer of New South Wales, aged 73 years. Interred June 10. Family Notices (1937, June 11). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 10. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17372807

1874 Transit Of Venus

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

_b_695.jpg?timestamp=1585852633297)

Map showing the visibility of the 1874 transit of Venus

The 1874 transit of Venus, which took place on 9 December 1874 (01:49 to 06:26 UTC),was the first of the pair of transits of Venus that took place in the 19th century, with the second transit occurring eight years later in 1882. The previous pair of transits had taken place in 1761 and 1769, and the next pair would not take place until 2004 and 2012. As with previous transits, the 1874 transit would provide an opportunity for improved measurements and observations. Numerous expeditions were planned and sent out to observe the transit from locations around the globe, with several countries setting up official committees to organise the planning.

There were six official French expeditions. One expedition went to New Zealand's Campbell Island, the other five travelling to Île Saint-Paul in the Indian Ocean, Nouméa in New Caledonia in the Pacific, Nagasaki in Japan (with an auxiliary station in Kobe), Peking in China, and Saigon in Vietnam.

There were five official British expeditions or observation sites. One expedition travelled to Hawaii, with two others sent to the Kerguelen Archipelago in the far southern reaches of the Indian Ocean, and Rodrigues, an island further north in the Indian Ocean, near Mauritius. A fourth expedition went to a site near Cairo in Egypt, and the fifth travelled to a site near Christchurch in New Zealand. Several of the expeditions included auxiliary observation stations that were constructed in addition to the main observation sites.

In the United States, the Transit of Venus Commission sent out eight expeditions funded by Congress, one to Kerguelen, one to Hobart, Tasmania, one to Queenstown, New Zealand, one to Chatham Island in the southern Pacific, one led by James Craig Watson in Peking, one to Nagasaki in Japan, and one to Vladivostok in Russia. The eighth expedition had been intended for Crozet Island, but was unable to land there and instead made observations from Tasmania. These expeditions obtained 350 photographic plates for the 1874 transit.

The transit was observed from many observatories, including the Melbourne Observatory, Adelaide Observatory and Sydney Observatory in Australia, the Royal Observatory at Cape Town in what is now South Africa, the Royal Alfred Observatory on Mauritius, the Madras Observatory in Madras, India, the Colonial Time Service Observatory in Wellington, New Zealand, and the Khedivial Observatory in Egypt. The Sydney Observatory sent an observing party to Goulburn in Australia.

.jpg?timestamp=1585852712688)

File:1874 Pierre Jules César Janssen - Passage de Venus.webm - Passage de Venus (1874) by Pierre Janssen

Italian astronomer Pietro Tacchini led an expedition to Muddapur, India. Other locations in India from where the transit was observed included Roorkee, and Visakhapatnam. The German astronomer Hugo von Seeliger directed an expedition that travelled to the Auckland Islands (subantarctic New Zealand islands).[3] German astronomers also travelled to Isfahan in Persia, and to Kerguelen. The Dutch astronomer Jean Abraham Chrétien Oudemans made observations from Réunion, and observations were also made from various points in the Dutch East Indies. Austrian astronomers made observations from Jassy, in what is now Romania. The Russian astronomer Otto Wilhelm von Struve organised expeditions to make observations in eastern Asia, the Caucasus, Persia and Egypt. Two Mexican expeditions travelled to Yokohama in Japan.

There were also several individuals that journeyed to various locations to observe the transit, or funded private expeditions. Archibald Campbell made observations from Thebes in Egypt. James Ludovic Lindsay funded a private expedition to Mauritius. Several private or amateur observations were known to have been made from New South Wales, including from Eden, Windsor, and Sydney. A privately funded expedition from the USA also travelled to Beechworth, Victoria, in Australia.

Not all the observers were able to make measurements, either due to adverse weather conditions, or problems with the equipment used. Many observers, particularly those on the official expeditions, used the new technique of photoheliography, intending to use the photographic plates to make precise measurements. However, the results of using this new technique were poor, and several expeditions were unable to produce publishable results or improve on existing values for the astronomical unit (AU). In addition to this, observations made of Mars were producing more accurate results for calculating the value of the AU than could be obtained during a transit of Venus.

The Transits of Venus in 1874 and 1882

May 1, 1869

Doubtless many of our readers may think it premature to say anything about an event six years before it will transpire, but there are good reasons in this case for such an apparently ill-timed proceeding. The transits of Venus to take place in 1874 and 1882 are justly looked forward to by astronomers as the greatest astronomical events of the century in which they will occur. Why they are so considered, and the necessity for anticipating them by extensive preparations, it is the object of this article to show. The phenomena called transits occur only with the inferior planets, that is, those whose paths of revolution around the sun lie wholly within that of the earth.

A transit is nothing less than an eclipse of the sun by an inferior planet, that is, the passage of either Venus or Mercury directly between the earth and the sun, so that their disks partially obscure its face, and appear as round, dark spots upon it. Conventional usage has limited the term eclipse of the sun to the obscuration of its disk by the moon, and transit to the same effect produced by the passage of Venus and Mercury between the earth and the sun, although there is no essential difference in the nature of the phenomena. The transits of Venus occur very seldom. The first one, we believe, of which there is any record, was observed in 1639, by the gifted young astronomer, Horrox, whose brilliant career was so suddenly terminated by death at an age when few have even begun to achieve immortality.

The celebrated Dr, Halley communicated a paper to the Royal Society in 1691, with a view of calling attention to a proposed method for determining the parallax of the sun, and thereby its real distance from the earth. Since his time only two transits of Venus have occurred viz., in 1761 and 1769. Dr. Halley ex. pressed in his paper the belief that, in the way proposed, the sun's distance from the earth would be determined with great accuracy. The feasibility of the method at once attracted the attention of astronomers, and, upon the occurrence of the transits in 1761 and 1769, the sun's distance was computed to be 95,173,000 English miles.

The parallax of heavenly bodies is the difference in their apparent relative position, when viewed from different stations. It is usually expressed in degrees, minutes, and seconds, of angular measurement. This may be illustrated by the following simple method. Take a station at any point where a tree, or lamp-post, or stake can I e brought into range with a corner of a house or any other fixed object, representing the sun. The intervening object may be considered to represent the planet Venus, and the station at which the two observed objects are in line, may represent a portion of the earth's surface. If, now, the observer take a station to the right or left of the first station, the objects will no longer appear superimposed, but separated to a distance, depending upon the distance between the two stations, the distance of the stations from the remotest object, and the distance of the stations from the intervening object. The angular difference between the apparent positions of the bodies observed, and the distance between the stations, are sufficient data for determining all the other distances, provided the angle formed by a line joining the two stations, and a line joining either station with the intervening object is also known. The problem is then reduced to the finding of one side of a triangle, another side and two angles being given, a very simple operation in plane trigonometry. In astronomical observation there are always some determinate errors, arising from refraction and other causes, which may, however, be readily corrected, and do not affect the general principle of the method as above illustrated. In calculating the distance of the sun from the earth, the stations, from which the observations are made, can be so placed that the semidiameter of the earth becomes one side of a triangle. The parallax of the sun was thus calculated from the transits of 1761 and 1769, and found to be 8*65 seconds angular measurement, and the distance of the sun was hence determined to be 95,173,000 English miles, as given above. Subsequent calculation by Encke made the parallax to be i 8*5776 seconds. j It will be seen that the correctness of these results depends i upon the accuracy of the observations upon which the mathematical calculations were based. That these were not accurate, seems probable from the fact that there is every reason to believe, from the sun's parallax, as more recently determined, that the distance as originally computed is wrong by at least 4,000,000 miles. Many hypotheses have been made as to the origin of such a grave mistake some attributing the error to confounding a part of the planet with its penumbra, and others to mistakes j i n the computation, but these are of little importance. The time is approaching when the problem can be reworked, and, with the improved apparatus now possessed by astronomers, and the wonderful advances made in methods of observation, it may well be hoped that this time a reliable result will be obtained.

The Standard (London) says of the extensive preparations now initiating for the observation of the coming transits, that " the Astronomer Royal is doing good service in preparing betimes lor the great event. Though it may seem a long time to look forward to, to those who are unacquainted with the amount of preparation required for such observations, those who know the difficulty of procuring a large number of j first-rate instruments, unless plenty of time is allowed, will j know that there is really no time to be lost, especially if, as ! we should hope would be the case, all the expeditions sent out are provided with precisely similar instruments and apparatus. It is imperative upon the government to put no obstacle in the way of carrying out these observations in the most perfect manner. England must not be behind the Continent, at any rate. If any amount of failure takes place, it will not bo from want of preparation on Mr. Airy's part. At the late meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society he showed that there was nothing indefinite about his ideas; he had already prepared careful maps both for observing the ingress and egress of the planet. He showed the importance of sending j expeditions to several places, because, among other considera-' tions, a thousand obstacles might interfere with the observations in any particular place. There are places which, if weather, etc., are favorable, will be admirable for all purposes, but, as in the case of Kerguelin Island, the chances are very much against a clear atmosphere. Captain Toynbee said that this island is seldom to be found on account of the fog. If practicable, no expedition will be of the importance of one sent to the South Pole, that is, as near to it as possible.

At the South Pole the effect of parallax will be the greatest that is to say, the position of Venus will vary to the greatest extent on the sun's disk. The Astronomer Royal in his maps suggests two points, one in Enderby's Land, but here the sun would be too low for it to be a certainly advantageous position he greatly preferred a point in the Antarctic Continent, where Sir James Ross landed. As a place for observation nothing could be better. The only point is, Will the severity of the climate admit of the expedition ?

Captain Richards, the hydrographer to the Admiralty, spoke well upon it. He showed that if properly fitted out and provided with good huts, clothing, and food, there would be no further objection to the place than must stand in the way of any Arctic expedition. Those, however, who joined in it would have to make up their minds to one thing, namely, that they would have to spend a year upon the spot; for that it was unapproachable at anything near the time when the transit will take place. To show, however, that he did not consider this in any way fatal to the position as a station for observation, he said that he should much like to be one of the party himself. In this he was fully borne out by Captain Davis, who landed there with Sir James Ross. So that we may hope that this, at least, will be one station, and that the government will not postpone till too late the preparations to make it as favorable for the comfort of the spirited observers who will join in the expedition ns for the objects of the enterprise. It may possibly be advisable to send out an exploring party previously, though Captain Davis did not seem to think that it would be necessary. The first great difficulty in all places will be to get the absolute longitude. No ordinary nautical longitude will be of the slightest value. Observations necessary can be made at many places easily accessible, as far :a England is concerned, as at Alexandria, where the telegraph will be of great use ; at many places, too, in the United States, where we can safely leave the work to Americans. We may especially do the same in the case of the Russians, where the exact longitude of Orsk, the extremity of the great arc of longitude extending from that place to Valencia, is known to a millionth part of a second, or in other words, to absolute certainty. The other places which are reepmmended to the English government are Mauritius for one reason, and Madagascar for another. If, however, it should be thought unnecessary to fix both of these'spots, then an intermediate station viz., on the Island of Bourbon, would be preferable. If the Astronomer Royal can show that the two stations would be of considerable advantage, we hope that no financial reasons will prevent his wishes being carried out. Above all things we would urge upon the authorities the importance of making up their minds as to the instruments to be used, and in losing no time in having them put in hand. There is one more point worth noticing. How far photography can be depended on as to accuracy in helping to discover the sun's distance is not easy to answer off-hand ; but certainly it is not to be doubted that much useful and interesting information may be secured by its means; and it is highly desirable that at none of the stations its use should be neglected. This part of the question is not, how- ever, of the same pressing importance as the fixing of the stations suitable for observing the ingress and egress of the planet, and of the preparation in good time of the instruments and apparatus required." Our readers will now be prepared to appreciate the importance of this subject, and to understand why its discussion is likely to occupy, to a large extent, the attention of the scientific press for a considerable time to come. - This article was originally published with the title "The Transits of Venus in 1874 and 1882" in Scientific American 20, 18, 281-282 (May 1869) - doi:10.1038/scientificamerican05011869-281d

THE TRANSIT OF VENUS.