Surf’s up: Australia’s breaks inject almost $3 billion into the economy each year

Highlights

- Surfing ecosystems provide recreation services with wellbeing benefits to participants and monetary flows into the economy.

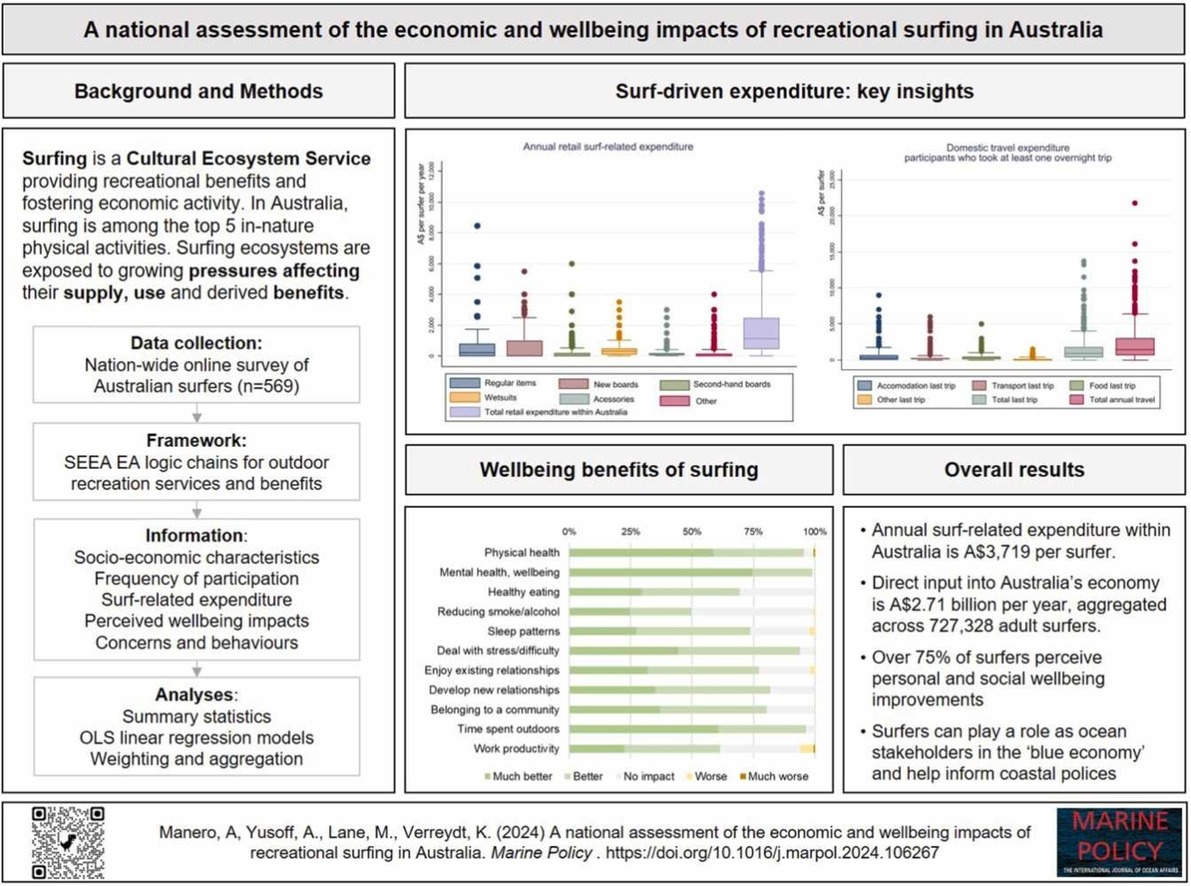

- The average Australian surfer spends A$3719 per year on retail (A$1858) and domestic travel (A$1861).

- Direct input into the Australian economy is A$2.71 billion per year; A$4.88 billion/yr including indirect effects.

- Surveyed surfers perceive benefits for their physical health (95 %), mental health (99 %) and community connectedness (80 %).

- Overcrowding, climate impacts and poor water quality are surfers’ top concerns, while fewer worry about shark risks.

It’s no secret Aussies love to surf. It’s one of our favourite pastimes, but it turns out riding the perfect wave offers more than just the ultimate thrill – it also provides a major boost to the economy, according to new research from The Australian National University (ANU).

The researchers found surfing injects almost $3 billion into the Australian economy each year.

“We asked participants how much they spent on domestic travel and how often they’d travelled to go surfing during the last 12 months, but also how much they spent on new boards, wetsuits and other surf-related accessories,” survey lead Dr Ana Manero, from ANU, said.

“Our research shows adult surfers spend more than $3,700 per person, each year.

“Using data from the Australian Sports Commission, which shows there are more than 720,000 active adult Australian surfers, we found that surfing injects at least $2.71 billion into the economy each year.

“This is a conservative figure at best because it doesn’t factor in overseas visitors who travel to Australia to go surfing or money generated through professional surfing.”

The nationwide survey of 569 people found that more than 94 per cent of respondents reported surfing had a positive impact on their physical and mental wellbeing and ability to deal with stress in their life.

Meantime, more than 80 per cent of respondents believe surfing helps foster a greater sense of connectedness to their community.

“Although surfing is typically perceived as a thrill-seeking activity and an individual sport, it’s actually a much more social endeavour than previously thought,” Dr Manero said.

According to Dr Manero, Australia’s surf breaks are increasingly coming under threat from a range of issues including climate change, coastal erosion, poor water quality and overcrowding pressures.

She argues governments have for too long “overlooked” the value of surf breaks and sees an opportunity for better policies and local coastal management plans to help safeguard our nation’s surfing environments and ensure they are more resilient.

“Surf breaks are valuable natural assets, but waves only form under a very delicate set of conditions that can be easily altered by anything that we do to the coast,” Dr Manero said.

“Things like sand nourishment programs, the construction of infrastructure, the expansion of a marina, can impact how waves form and how often they break.

“A previous ANU study found a wave off the town of Mundaka in northern Spain disappeared because of changes to the sand bar caused by dredging in the nearby river. That resulted in the cancelation of a competitive event and led to a slowdown in economic activity in the area.

“Meantime, closer to home, the expansion of the Ocean Reef Marina in Perth in Western Australia caused the disappearance of three surf breaks in 2022. An artificial reef has now been proposed, but it would have been better to recognise the value of the natural breaks in the first place."

Dr Manero said Australia has an opportunity to follow other countries and adopt formal legal protections to preserve the country’s surfing environments.

“Unlike countries like New Zealand and Peru, where surf breaks are recognised by national-level legislation, Australia’s environmental laws and polices largely overlook surf breaks as valuable natural assets. Across the country, only 20 surf breaks have some form of legal protection,” she said.

“This means that in Australia you can basically make a wave disappear and no one bats an eyelid because these surf breaks sit in a legal vacuum.”

The research is published in the September 2024 edition of Marine Policy. Co-authors Asad Yusoff from ANU and Mark Lane and Katja Verreydt from Surfing WA contributed to the findings.

Ana Manero, Asad Yusoff, Mark Lane, Katja Verreydt. A national assessment of the economic and wellbeing impacts of recreational surfing in Australia, Marine Policy, Volume 167, September 2024, 106267, ISSN 0308-597X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106267.

Abstract:

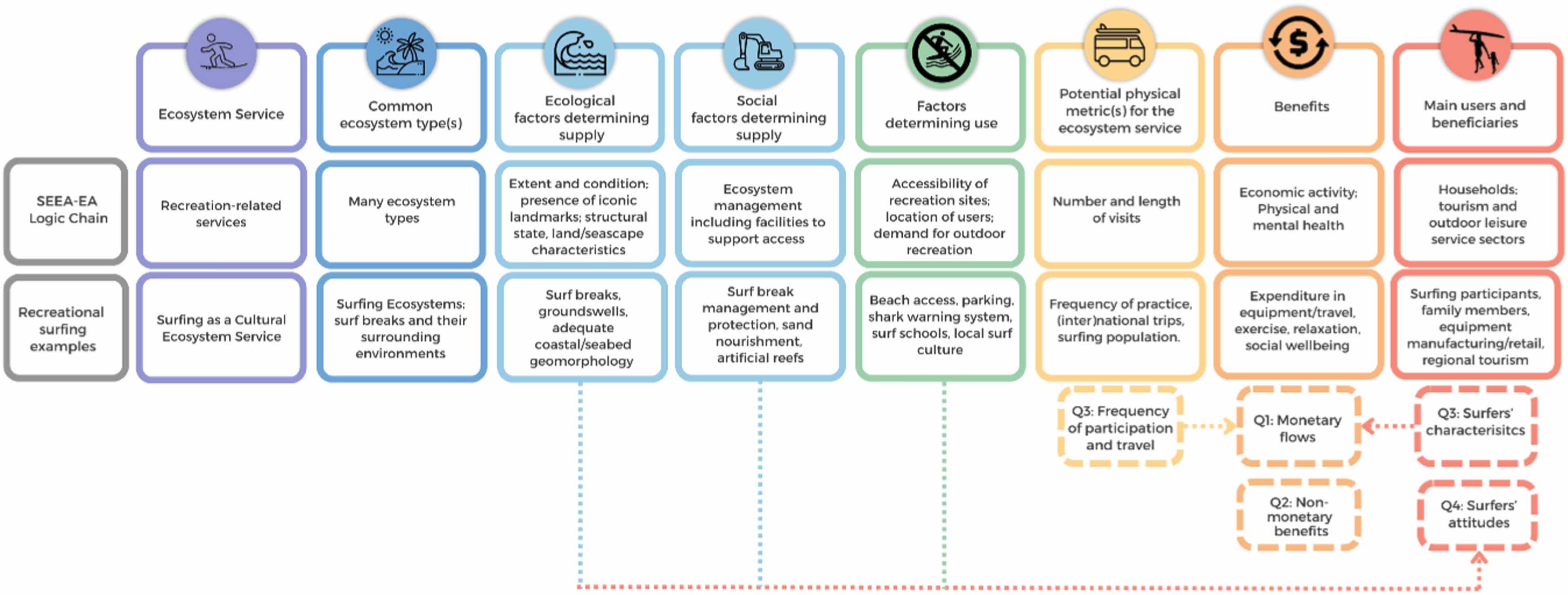

Surfing is a cultural ecosystem service, providing recreational benefits to over 50 million people worldwide and fostering economic activity through retail and tourism industries. Despite its growing popularity and threats to natural environments, surfing’s economic and social impacts remain sparsely documented. This study provides a nationwide assessment of surfing’s impact on Australia’s economy and participants’ wellbeing, using an online survey of Australian surfers (n=569).

Domestic surf-related expenditure was estimated at A$3719 per surfer per year, including retail (A$1858) and travel (A$1861). Heterogeneity analyses reveal differences in expenditure patterns across regions, age groups and modalities of engagement in the sport. Aggregating across a population of 727,328 Australian adult surfers, the direct input into the market economy is estimated at A$2.71 billion per year. Standardized wellbeing measures indicate that over 80 % of participants experience positive effects from surfing, particularly in community connectedness, physical, and mental health.

However, major concerns exist regarding the sustainability of surfing environments due to erosion and overcrowding pressures. Following the SEEA EA’s ‘logic chain’ framework, this study provides a set of baseline results that may be inputted into accounting processes considering recreational ecosystems services. Further, the systematic approach used in this study could be replicated by comparative analyses across time and other prominent surf regions.

As coastal areas worldwide urgently respond to climate threats and the need to support the ‘blue economy’, a better understanding the socio-economic values derived from ocean-based recreation can help inform coastal polices aimed at fostering more resilient environments.

Introduction

The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) follows the mandate to generate “The Science We Need for the Ocean We Want”, in order to reverse the decline in ocean health, whilst improving the wellbeing of coastal communities [116]. With the aim to support sustainable ocean-based economies and broaden citizen participation, increasingly diverse groups of stakeholders are called upon to provide insights to inform policy and decision-making processes [16]. Surfers (ocean users riding waves, typically with the use of a board or other craft) have been described as key ocean knowledge holders, “injecting millions of dollars into local economies” ([89], p. 181). Despite surfing’s recognition as a Cultural Ecosystem Service (CES) [88], the monetary and social values associated with recreational surfing are only sparsely documented, even in premier surf regions like Australia ([20], [67]). A better understanding of the dynamics associated with surfing demands can help predict how growing natural and anthropogenic pressures may impact socio-economic activities that are underpinned by the presence of surf breaks [63].

Worldwide, there are an estimated 50 million surfers spending up to US$65 billion annually on surf travel, with figures rising following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and surfing’s inclusion as an Olympic sport in 2021 [54]. While surfing demands keep growing, the availability and quality of surfable waves is increasing compromised by climatic and direct human pressures [58], [72]. The formation of surfable waves depends on a specific set of oceanic and geomorphological conditions, but the effects of coastal changes on surfing amenity are still poorly understood and rarely quantified [18], [25], [43], [50], [100]. Historically, community organizations, such as Surfrider Foundation (www.surfrider.org.au ) and Surfers Against Sewage ( www.sas.org.uk ), have played a fundamental role in knowledge generation and translation [114]. For example, in 2020 in Chile, advocacy efforts by Fundación Rompietes and Save The Waves Coalition led to the creation of the Created Piedra del Viento Coastal Marine Sanctuary–a 4000 ha biodiverse hotspot, home to two iconic surf breaks [98]. More recently, a growing body of academic literature has documented the values and pressures associated with recreational surfing, including to inform decision-making processes, such as policy formulation and cost-benefit analyses [95].

From a wellbeing perspective, surfing has been examined as part of ‘blue spaces’, i.e., health-enabling places where water is at the center of the environment [17], [69]. The therapeutic benefits of surfing are well documented among adults and children with special conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder [21], [62], poor mental health [61], [65], [68], disabilities [3] and chronic illness [35]. More broadly, qualitative analyses of local case studies suggest that surfing may contribute to social wellbeing through community cohesion and strong family relationships [110], [118]. Further, surfing’s sense of place has been observed as a catalyzer of pro-environmental attitudes, like care for coastal landscapes, ocean literacy and activism [13], [32], [48], [95].

The presence of surf spots has been found to be associated with several forms of economic activity, such as attraction and fixation of local employment, and improvements in local services and infrastructure [55], [64], [87]. A limited number of studies have estimated various forms of values, benefits and impacts associated with recreational surfing (see Table A1 in the Appendix under Supplementary material for a comprehensive overview of market and non-market valuation studies of recreational surfing). For example, using night lights as a proxy indicator, McGregor and Wills [64] found that, at a global scale, good quality surf breaks added US$4.00 billion in local economic activity. A hedonic pricing study by Scorse et al. [104] found proximity to the Santa Cruz surf break, in California, increased a house price by U$106,000, compared to an equivalent property one mile (1.6 km) further away. While a few non-market valuation studies exist (e.g. [75], [86]), the literature on surfing’s economic impacts has predominately focused on direct expenditure (see Table A1). These two approaches serve different aims and are underpinned by diffident theoretical frameworks, with welfare values appropriate for environmental valuation, and exchange values suited for accounting purposes [77].

From a policy perspective, recognizing the values associated with non-extractive ocean-based recreation is important, especially since the majority of the world’s high-quality surf breaks are situated within marine biodiversity hotspots [114]. As the marine area under full protection in Australian water declines, and current mechanisms remain primarily focused on ecological targets [27], an important policy question regards the formulation of guidelines and regulations simultaneously serving both biodiversity and cultural goals [10]. For this purpose, it is helpful for values associated with cultural ecosystem services to be framed within a system that allows integration and comparison with information linked to other coastal ecosystem services [2].

In this study, we examine how recreational surfing, understood as a CES, is characterized under the conceptual framework of SEEA EA ‘logic chains’ for recreation-related services (Fig. 1). SEEA EA logic chains are a systematic framework to record information related to the supply, enabling characteristics and benefits of ecosystem services, as well as interconnections between ecosystem variables and outcomes [2]. As elaborated by Barton et al. [11], SEEA EA logic chains characterize outdoor recreation services through four types of economic input: accommodation, transport, guiding and equipment. Benefits from outdoor recreation include enjoyment, physical and mental health to participants, as well as economic gains accrued to the tourism and leisure services sectors [117]. SEEA EA logic chains have been used to examine economic impacts of outdoor recreation, including national parks in Australia [77] and marine areas in the north-east Atlantic [2].

In full at:

Ana Manero, Asad Yusoff, Mark Lane, Katja Verreydt. A national assessment of the economic and wellbeing impacts of recreational surfing in Australia, Marine Policy, Volume 167, September 2024, 106267, ISSN 0308-597X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106267.