May 1 - 7, 2022: Issue 536

The Petrov Safe Houses In Pittwater

These were followed by a March Past at Bilgola Beach, and 11 am Commemorative Services at Palm Beach RSL, at Church Point's Memorial, at Avalon Beach and Terry Hills and a Dusk Service at Collaroy RSL Sub-Branch. Overall thousands came to Honour all those who have served and all those who serve still.

There were also some wonderful stories to be met along the way. As one example, Avalon Bulldogs Junior Rugby League Football Club member Maverick and his brother, part of the 11am March at Avalon Beach with their sports club, were spotted as grandmother Carmel was pinning on their great great grandfather's and great great grandmother's medals as they walked to the muster point outside Avalon Public School.

Carmel's parent's, Bede William Merrick and Elizabeth Minnie Merrick (nee White), served during World War II, Elizabeth in the Army and Bede in the Army too.

Bede was a 'Rat of Tobruk', a very fine musician according to the papers of the day, and later was assigned to look after defecting Russian spy Petrov as part of the Neutral Bay unit of the Volunteer Coast Patrol. Apparently Bede was stationed in his boat off the McMahon's Point 'safe house' the Petrovs lived in after deciding they'd rather live here than in 1950's Russia.

As a small 'thanks' to Maverick and his wonderful grandmother Carmel, and following up numerous requests from Readers, this Issue's History page delves a little deeper into those April 1954's happenings - possibly of interest to a few as three of the 'safe houses' given over for looking after the Petrovs after their defection were purportedly in Pittwater; at Palm Beach, Avalon Beach and Towlers' Bay.

.jpg?timestamp=1651168645345)

proud grandmother Carmel and her grandsons

Vladimir Mikhaylovich Petrov, born Afanasy Mikhaylovich Shorokhov into a peasant family in the village of Larikha, in central Siberia, (February 15 1907 – June 14 1991) was a member of the Soviet Union's clandestine services who became famous in 1954 for his defection to Australia.

Vladimir Petrov had been third secretary of the Soviet Embassy in Canberra since February 1951. His wife, Evdokia, also worked at the embassy, but the couple were actually intelligence officers who were carrying out espionage in Australia. On April 3rd 1954, Vladimir Petrov defected to Australia. Evdokia followed on April 20th after Australian police freed her from Soviet couriers at Darwin airport.

The Petrovs' defections caused the USSR to withdraw their embassy from Canberra and expel Australian diplomats from Moscow. On April 13th 1954, Prime Minister Robert Menzies told parliament about Vladimir Petrov's defection. He also established the Royal Commission on Espionage to inquire into and report on Soviet espionage in Australia.

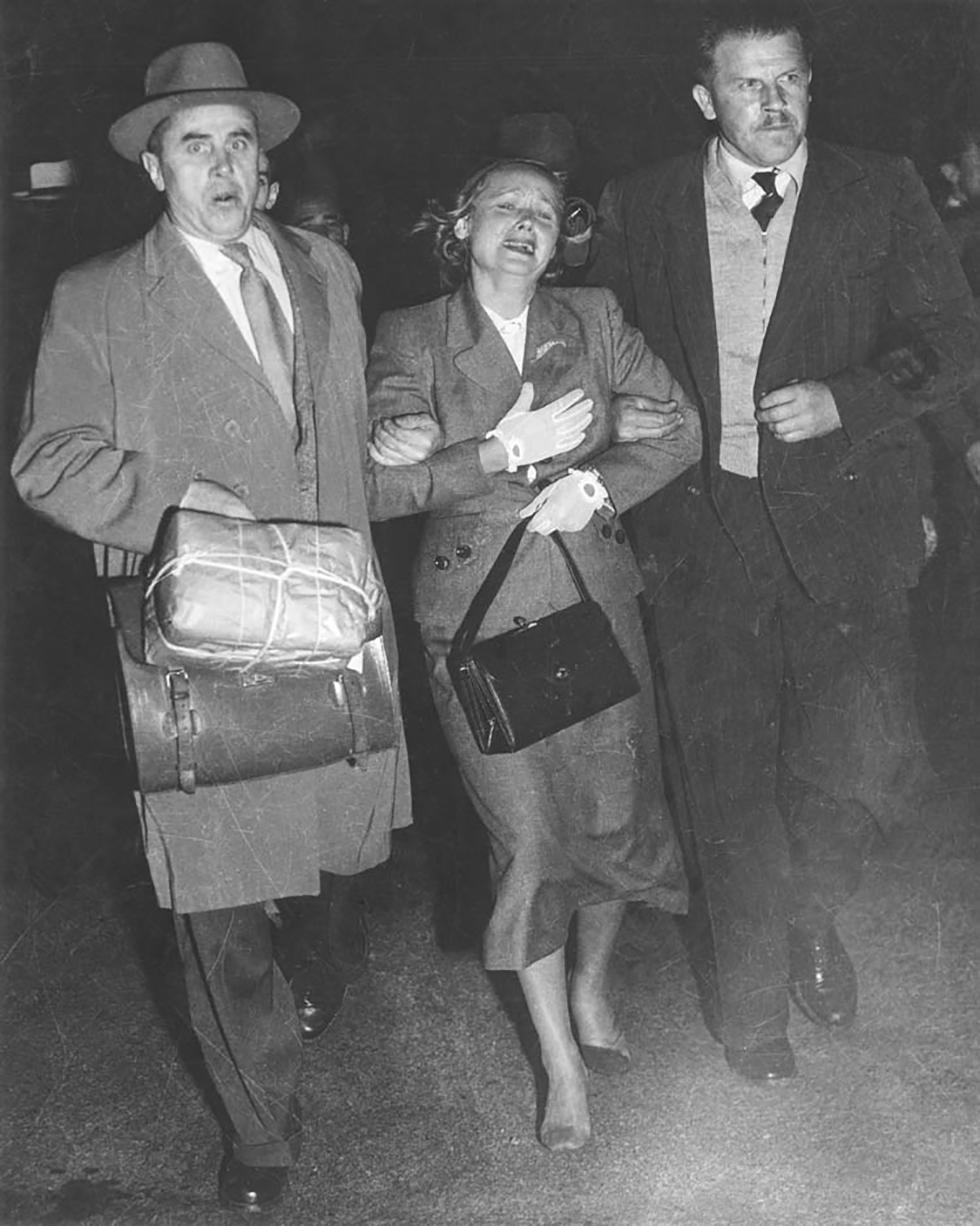

Evdokia Alexeevna Petrova (1914-2002) was taken by Russians into their custody as soon as news of her husband's defection broke and placed in house arrest at the Russian embassy in Canberra. She was told by them that her husband had been 'kidnapped' by Australian authorities. Initially preferring to return home to avoid reprisals against her family she changed her mind at Darwin airport and was dramatically removed from Soviet custody. This followed a letter sent from her husband to the Russian Embassy and a reply which stated, supposedly from her, that she did not want to stay and scenes at Mascot where she was being 'manhandled' onto a plane despite thousands of shouting Australians, including many Soviet and eastern European refugees, trying to stop this. There her reportedly crying out in Russian, “I not want to go'', set the wheels in motion to give her a chance to speak up. So rough were her 'minders' that one of her shoes came off in the scuffle and they would not stop long enough for her to regain it. Joyce Bull, an air attendant (then called a 'hostess') gave Mrs Petrov a pair of shoes to replace the shoe lost in the scuffle at Mascot.

A few notes from the pages of the past:

Mrs. Petrov Leaving

Mrs. Petrov being taken by car from the Russian Embassy, Canberra, for Sydney yesterday afternoon. A Russian courier is nearest the camera in the front seat. Mrs. Petros is on the far side, hidden from view. A Russian attaché takes pictures of the photographers. Mrs. Petrov Leaving (1954, April 20). Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article134917692

MRS. PETROV GOES

Two Russian couriers forcing Mrs. Petrov on to the Mascot tarmac to the plane in which she left Sydney last night on her way to Moscow.

She called "Help me!" "Save me!" in English. As her guards dragged her on to the plane she said in Russian, "I don't want to go home."

Angry people mobbed the plane, stones at it and dragged the steps away. Several men struck the Russians heavy blows on the face and body

Menzies says Mrs. Petrov will get another chance, Page 2. More Pictures, Pages 3 and 5. MRS. PETROV GOES (1954, April 20). The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1931 - 1954), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article248870673

GUARDS DRAG AWAY MRS. PETROV

" Help, save me," she screamed

Mrs. Evdokiva Petrov called 'Help me'. 'Save me,' as two Russian couriers dragged her on to a Constellation plane last night. Hundreds of people mobbed the plane and delayed its take-off from Mascot airport for 15 minutes. Mrs. Petrov cried and screamed as the couriers dragged her towards the plane through the angry crowd.

Crowd attacks

The crowd at the airport totalled about 3000. Mrs. Petrov is the wife of Vladimir Petrov, Third Secretary of the Russian Embassy, who was granted asylum in Australia after revealing details of Soviet espionage. The two Russian couriers are V. Karpinsky and P. Jarkov. They arrived last Thursday from Russia, and are escorting Mrs. Petrov back to Moscow. About 8 p.m. the Second Secretary at the Russian Embassy, Mr. P. V. Kistlitsyn, arrived at Mascot in a diplomatic car. Later he boarded the Constellation without an escort and without trouble. The Constellation is due to land at Darwin at 5.25 a.m. today (Sydney time). The plane will be on the ground for two hours 20 minutes.

Police describe the departure of the Russians as a near-riot. The crowd fought, struggled, punched, kicked, and screamed from the moment Mrs. Petrov arrived at the airport at 9.20 p.m. until she was inside the plane at 9.35 p.m. The crowd tore the gangway from the aircraft while the two Russian couriers were dragging Mrs. Petrov up the steps.

A big crowd had gathered outside the Overseas Terminal before the Russians arrived. Kistlitsyn entered the Terminal with an Embassy attaché and went to the B.O.A.C. luggage counter and checked in luggage and collected tickets for the Russian party of four. About 9.10 p.m. two diplomatic cars parked in a driveway a short distance from the terminal. Mrs. Petrov, weeping, was sitting in the front seat. Reporters and photographers approached the car and cameramen took pictures of her sitting in the front seat. The two Russian couriers, who were sitting in the back seat, held their hats over their faces. The cars remained parked in the drive for 10 minutes, then drove up to the overseas terminal. A crowd of 2000 were waiting outside the terminal and another 1000 inside.

Rushed at car

The car containing Mrs. Petrov drove up to the first door of the overseas terminal about 9.20 p.m. The two couriers got out of the back of the car. As they moved to open the front door the crowd swept on the car. Scores of uniformed pol-ice, C.I.B. detectives, Commonwealth Security men and Qantas security officers were unable to hold back the mob. Fierce fighting broke out around the car. The couriers, assisted by other Russian Embassy officials, pulled Mrs. Petrov from the front seat of the car. Mrs. Petrov looked ill and in a state of near collapse.

Several men struck the Russian couriers heavy blows in the face and body. The crowd crushed the group against the ear. Several men were knocked to the ground as police forced their way towards the car. The Russian couriers tried to drag Mrs. Petrov to the entrance of the terminal opposite their car. The couriers stood each side of Mrs. Petrov and each had hold of one of her arms. The mob swept the Russian group away from the terminal doors and forced them 80 yards along the road toward the T.A.A. terminal

Brawling punching, kicking and fighting was going on among the crowd near the Russians all the time Scores of New Australians yelled to Mrs. Petrov. "Do you want to go back?" They also screamed at the couriers. "Let her go, you communist criminals." The crowd continually booed as it fought to tear Mrs. Petrov from the powerful grip of the couriers. Scores of White Russians, Latvians and Estonians said they heard Mrs. Petrov say she did not want to go back to Russia Mrs. Petrov said in Russian: "Ya ne ehotchu yachatz domoi nazatj" — (I don't want to go home) Many anti-Communist migrants from Iron Curtain countries were in the crowd. Among those who heard Mrs. Petrov use these words were the leader of the Czech community in Sydney, Mr Thomas Jilek.

Many of them said Mrs. Petrov looked like a very sick person or one who had been drugged. Two Russian Embassy officials seemed to half carry her, they added Mr. V. Stepanoff, an ex- policeman, of Bruce Street, Stanmore, said he heard M . Petrov say Russian, "I don't want to go home." Another who heard her say it was one of about 30 migrants who tried to free Mrs Petrov. He is Mr. Victor Nepomnjatschy of Brook Street, Coogee. He said: "Somebody hit me on the jaw and I had to let go."

As Mrs. Petrov was being led to the aircraft hundreds of migrants shouting "free her— she wants to stay"- jumped railings' to follow Mrs. Petrov on to the tarmac. Wild scuffIe

There was a wild scuffle between migrants and police and hundreds of people followed Mrs. Petrov and her guards to the air craft. The couriers, sweating and panting, frequently exchanged blows with those trying to free Mrs. Petrov. One man spat in the face of one of the couriers.

An Australian who got in front of Mrs. Petrov and demanded: "Do you want to go to Russia?" was struck on the jaw with a case by one of the couriers and knocked to the ground. The crowd swarmed around the aircraft Many of them were smoking, and Qantas officials and aircrew sent out a call for a fire engine One of them said: "For God's sake — look after the plane." People were smoking right underneath the air craft. While the crowd was milling around the air craft several people tried to board the plane. Several of them had reached the landing stage when it was suddenly pushed away from the door.

A large crowd inside the terminal waiting to see Mrs. Petrov were unaware of the riot outside. Among them were Czech national groups carrying banners, "We want the release of political prisoners in Czechoslovakia' and "We want free Czechoslovakia in Europe " When the crowd had pushed the Russians almost to the T.A.A. terminal police shepherded the couriers and Mrs. Petrov through asmall gate on to the tar mac. The police stopped the crowd following the Russians through the gate. But hundreds climbed over the fence, or raced through the terminal on to the tarmac.

The Russians at first, dragged Mrs. Petrov, who was continually weeping and wiping her face with her hands, towards a T.A.A. plane bound for Melbourne

Feet drag

After they had gone 50 yards across the tarmac to the T.A.A. plane, with a huge crowd following, they wheeled suddenly and made towards the Constellation about 100 yards away. There were fresh bursts of fighting and punching. The crowd struggled with police and security officers and tried to release Mrs. Petrov from the grip of the Russians. Mrs. Petrov's feet were dragging along the ground. The couriers were almost carrying her and almost running. The crowd was screaming, and booing, and hissing.

The couriers tried to get Mrs. Petrov up the crew's ladder on the side of the plane farthest from the terminal. The crowd tore them away from the crew's ladder, and the couriers, assisted by Qantas officials, dragged Mrs. Petrov under a wing and around the tail of the plane to the passengers' gangway. Hundreds streamed on to the tarmac from the terminal. As the couriers and Mrs. Petrov began to ascend the gangway the crowd dragged it from the plane's side.

A fantastic melee broke out around the gangway. Qantas security officers struggled with men and women in an effort to get Mrs. Petrov up the gangway. A woman climbed the side of the gangway and got a firm clutch of the courier on Mrs. Petrov's right. A Qantas security officer punched her until she let go the Russian's arm. Several others grabbed the couriers and the mob milled around the gang way. Police punches Police tried to quell the crowd and dragged down people who were climbing the gangway. They put armlocks and headlocks on several and swung them away from the gangway and threw them bodily into the crowd. As others pressed forward police forced them back with punches, elbow thrusts, and open-palmed pushes in the face. Police and Qantas security officers fought violently to keep men from following the Russians up the- gangway. Some of the Qantas security men used their boots to keep back the mob. The couriers inched forward up the gangway with Mrs. Petrov. She was obviously in extreme distress and was crying out in both Russian and English. Mrs. Petrov was leaning backwards, as the couriers forced her bit by bit up the gangway. She had lost one of her shoes in the struggle to reach the plane. The couriers were dishevelled and perspiring, and one lost his hat. Three rocks hit the plane above the port wing. Many New Australians cried out, "They've drugged her," "Stop them " ."Let her go."

Mrs. Petrov without here shoe

Bearlike grip

At one stage the gangway was dragged back 10 feet from the side of the plane. A Qantas security man nearly fell from the platform at the top as it was pulled backwards. As the gangway swayed to and fro the couriers, hugging Mrs. Petrov in a bear-like grip, looked around in horror and amazement. For several minutes the gangway remained a dozen feet from the plane. Below police, security officers, and Qantas employees fought and struggled in the crowd. Slowly officials manoeuvred the gang-plank back to the aircraft door The couriers hustled Mrs. Petrov into the plane's doorway. Two members of the plane's aircrew had to help the couriers drag Mrs. Petrov the last few feet into the plane. GUARDS DRAG AWAY MRS. PETROV (1954, April 20). The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1931 - 1954), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article248870671

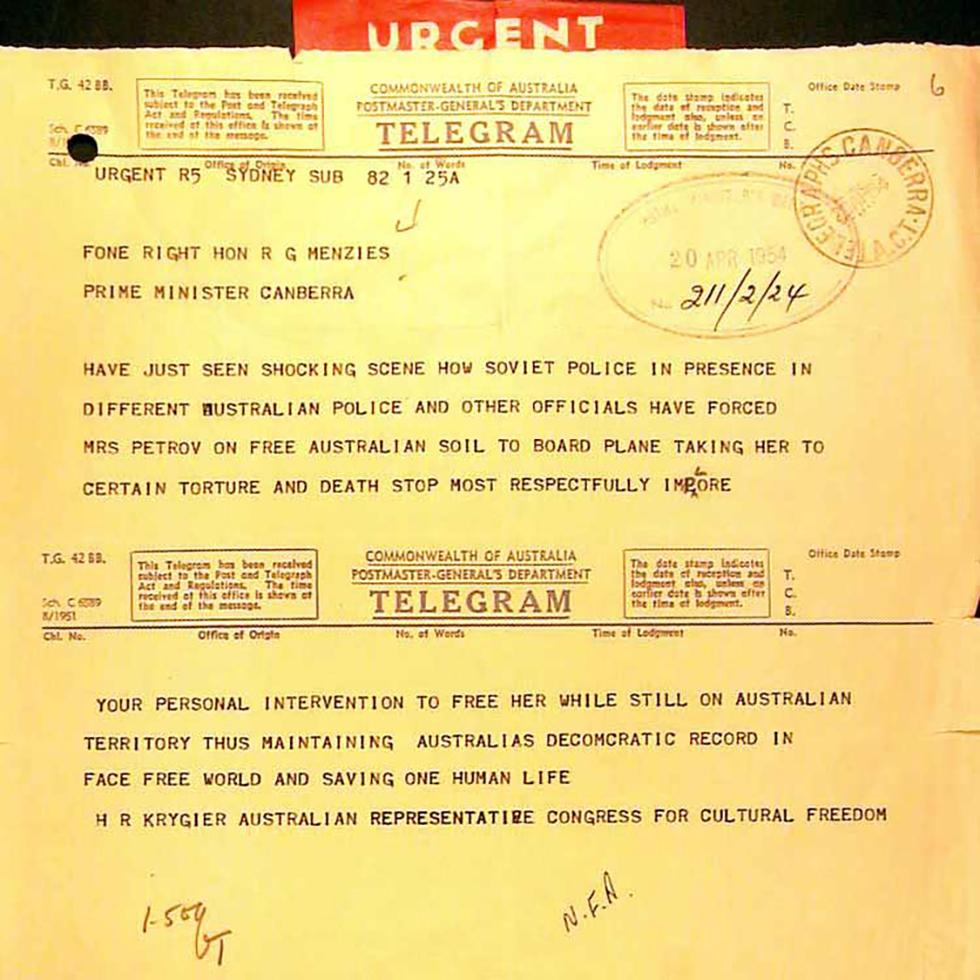

Telegram to Prime Minister Robert Menzies, urging him to intercede

At 9.45pm, then Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies telephoned the head of ASIO, Brigadier Charles Spry, in Canberra. Brigadier Spry sent three questions to the captain of the BOAC Constellation: What is the physical condition of Mrs Petrov? Is she in a state of fear? Has she indicated that she wishes to stay in Australia?

Evdokia told flight stewards that she was frightened of her couriers, who were armed. At 2.20am, Captain Davys signalled his replies: she was in a state of fear. She did wish to stay in Australia.

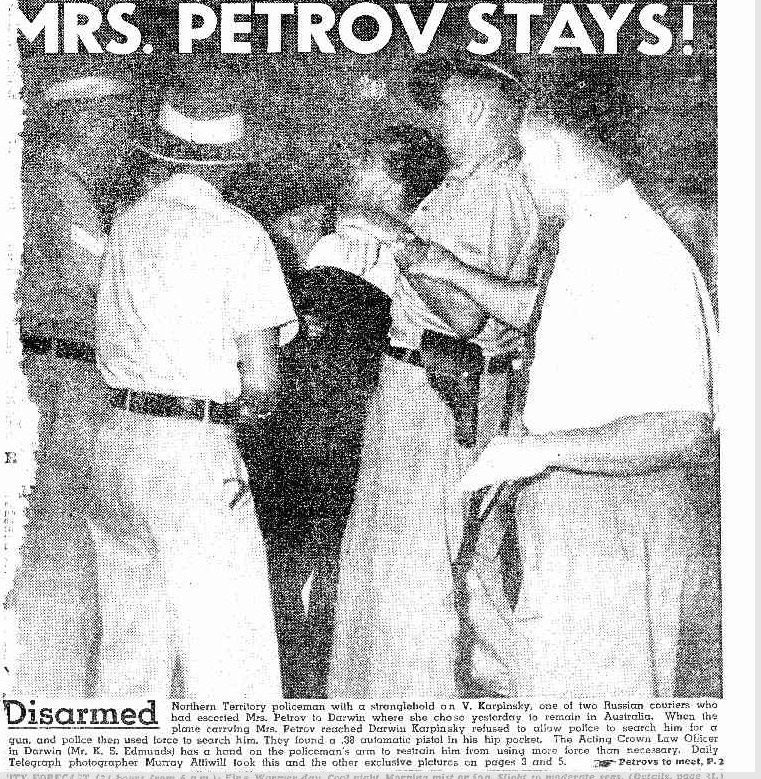

Brigadier Spry contacted the Acting Administrator of the Northern Territory, Reginald Leydin, who was to ask Evdokia on arrival whether she wished to stay. Spry had become aware of section 119 of the Air Navigation Act, which stated that the carrying of firearms on aircraft flying over Australian territory was illegal. Police, law officers and ASIO operatives approached the gangway when the Constellation landed at Darwin at 5am to refuel. Leydin drew Evdokia aside to offer asylum. One courier, Karpinsky, resisted and a Sergeant Ryall put him in a headlock while he was disarmed.

DISARMED

Northern Territory policeman with a stranglehold on V. Karpinsky, one of two Russian couriers who Escorted Mrs. Petrov to Darwin where she chose yesterday to remain in Australia. When the plane carrying Mrs. Petrov reached Karpinsky refused to allow police to search him for a gun, and police then used force to search him. They found a .38 automatic pistol in his hip pocket. The Acting Crown Law Ofiicer in Darwin (Mr. K. S. Edmunds) has a hand on the policeman's arm to restrain him from using more force than necessary. Daily Telegraph photographer Murray Attiwill took this and the other exclusive pictures on pages 3 and 5. Petrovs to meet, P. 2 MRS. PETROV STAYS! (1954, April 21). The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1931 - 1954), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article248870829

The commission opened in Canberra on May 17th 1954. This sat for 126 days over the following 10 months and examined 119 witnesses, producing almost 3000 pages of transcripts. It also received over 500 exhibits, including the documents Vladimir Petrov handed to Australian authorities, which became known as 'the Petrov Papers'.

The commission presented an interim report to the Governor-General in October 1954. This report dealt with the authenticity of two of the Petrov Papers. It was published as an appendix to the final report. The final report was presented to the Governor-General on August 22nd 1955 and to Parliament on September 14th 1955.

The commission found that:

- the Petrov Papers were authentic documents and the Petrovs were truthful witnesses

- the Soviet Embassy in Canberra had been used for espionage in Australia from its establishment in 1943 to its departure in 1954

- the only Australians who knowingly assisted Soviet espionage were communists.

The commissioners recommended that no-one be prosecuted as a result of their inquiry.

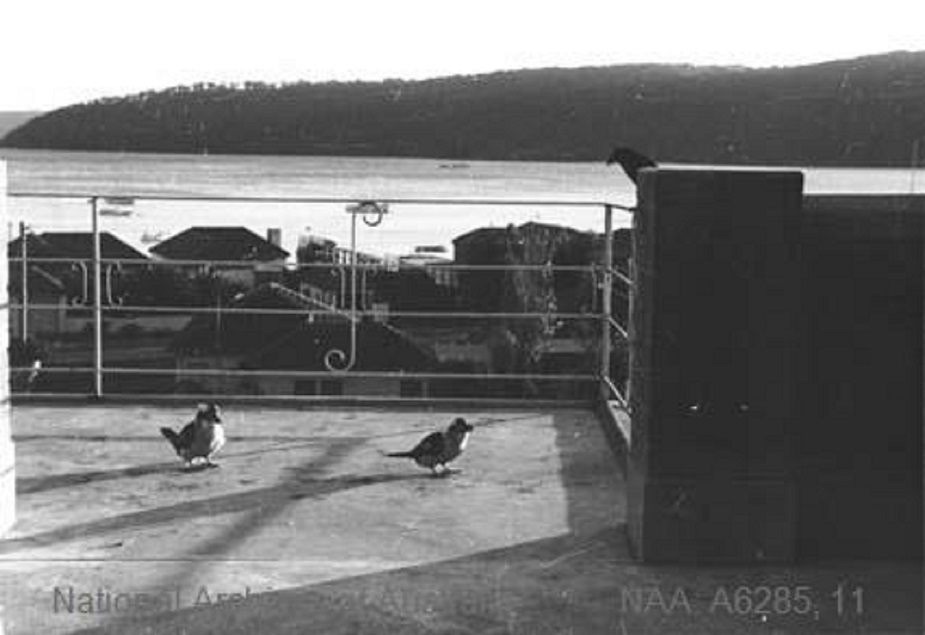

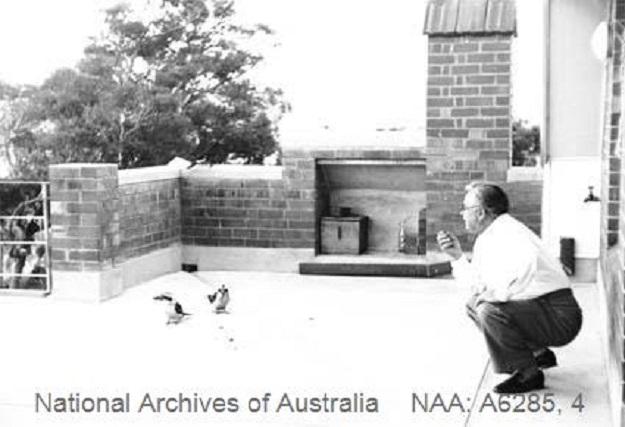

The Petrovs were photographed at a ”safe house” in Palm Beach mastering the art of using a Hills Hoist, an adjustable clothes line, feeding the resident kookaburras and speaking inside the home. It was actually from this home on Barrenjoey Road, Palm Beach, that Vladimir is stated to have spoken to his wife via a phone call to Darwin, urging her to stay in Australia too.

That call would have been the first time they had been able to speak without interference.

Two kookaburras on verandah of the Palm Beach safe house occupied by Vladimir Petrov and Evdokia Petrov after their defection to Australia. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage. Copy of photo courtesy National Archives of Australia.

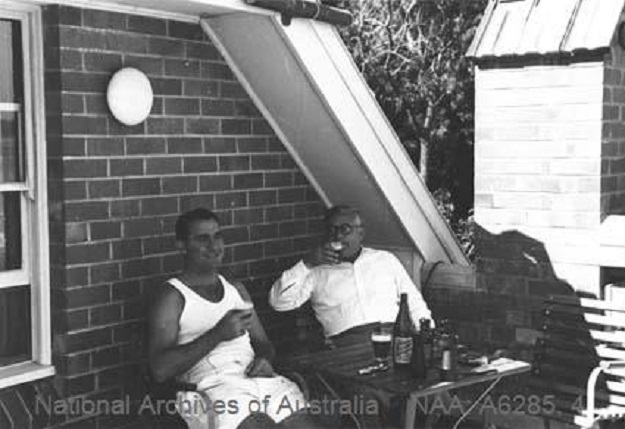

Vladimir Petrov and Evdokia Petrov (left) with ASIO officer Ernie Redford, after the couple's defection to Australia. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage, 1954 and Vladimir Petrov (right) and ASIO officer Ernie Redford (left) in garden after his defection to Australia. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage, 1954. Photos courtesy National Archives of Australia.

Evdokia Petrov with two ASIO officers (identities suppressed for national security reasons) after she and her husband Vladimir Petrov were granted political asylum in Australia. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage, 1954 and Kookaburra being fed by Vladimir Petrov on the verandah of the 'safe house' where he and his wife Evdokia Petrov were held following their defection to Australia. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage, 1954, and View from the verandah of the 'safe house' where Vladimir Petrov and his wife Evdokia Petrov were held following their defection to Australia. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage, 1954. Below; Vladimir Petrov sharing a beer with ASIO officer Ron Richards on the verandah of the 'safe house' where he and his wife Evdokia Petrov were held following their defection to Australia. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage. Photos courtesy National Archives of Australia.

This is around the same location on Barrenjoey Road, Palm Beach in 2016, Australia Day

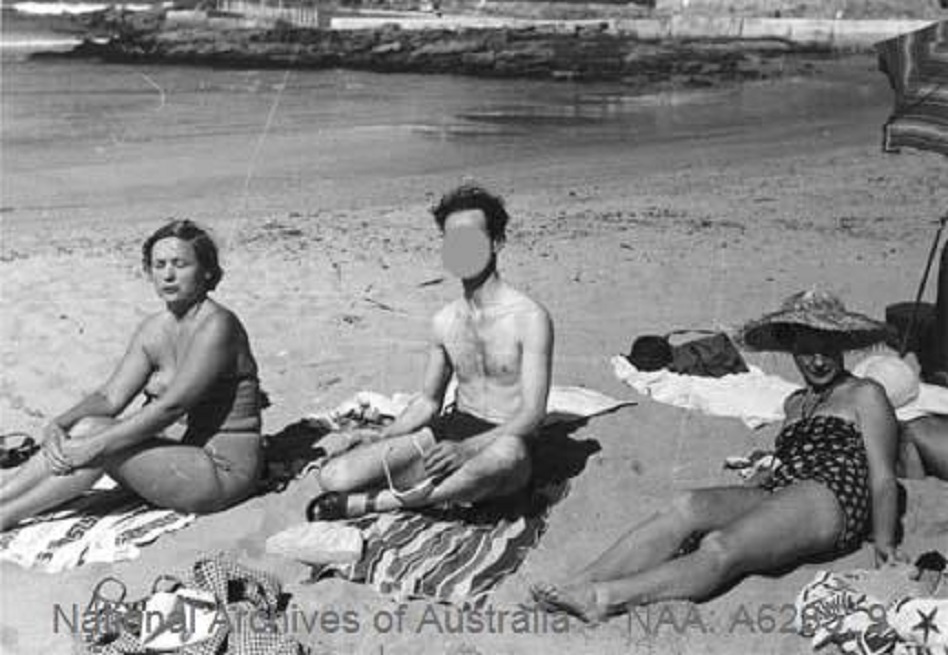

Evdokia Petrov and ASIO officers (identities suppressed for national security reasons) on the beach. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage, 1954. Copy of photo courtesy National Archives of Australia.

Evdokia Petrov and ASIO officers (identities suppressed for national security reasons) on the beach after being granted political asylum in Australia. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage 1954. Copy of photo courtesy National Archives of Australia.

Evdokia and Vladimir Petrov on the verandah of the Palm Beach safe house. Copy of photo courtesy National Archives of Australia.

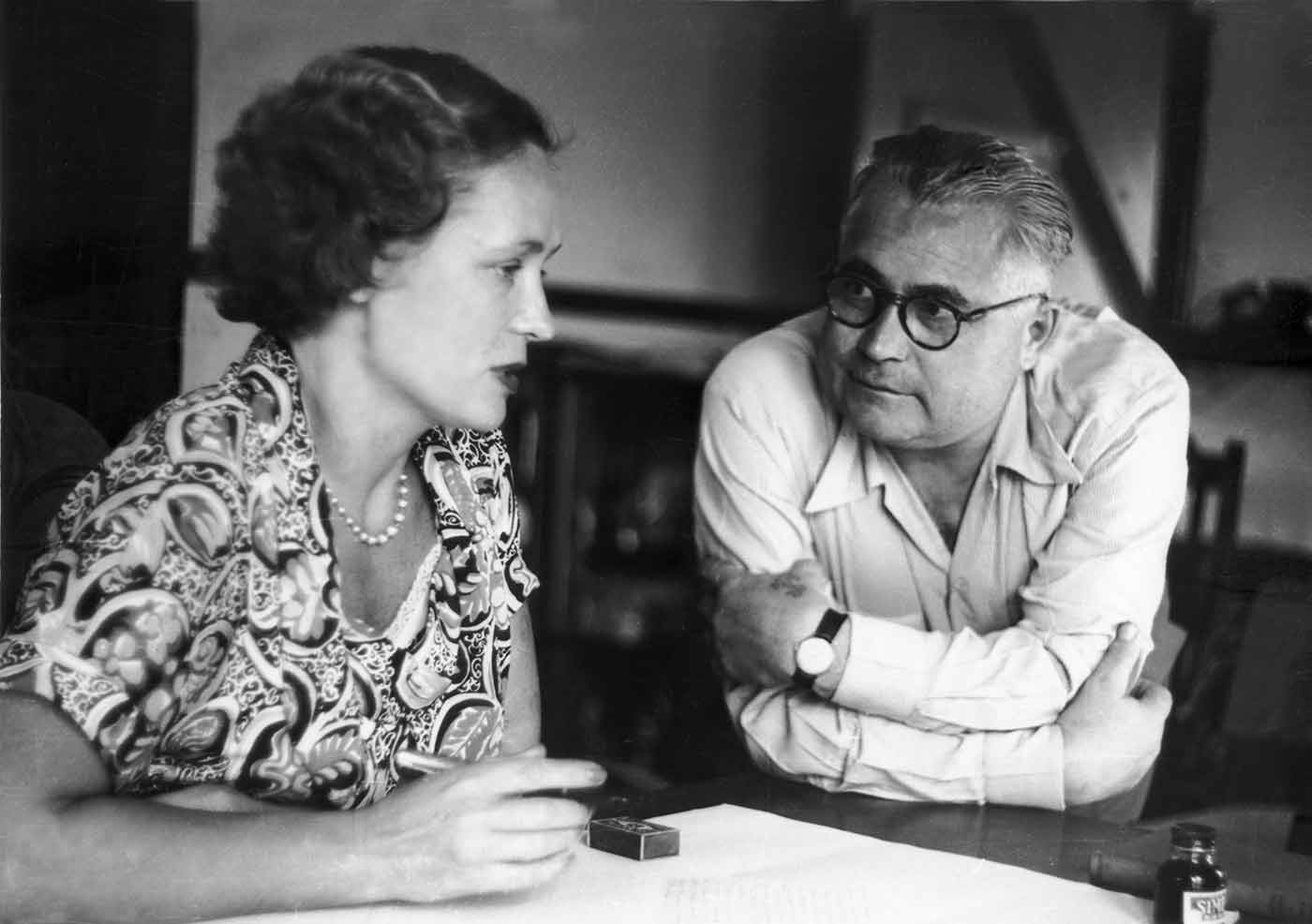

Vladimir Petrov and Evdokia Petrov inside the safe house in which they were held following their defection to Australia. Photograph presented as evidence to the Royal Commission on Espionage. Copy of photo courtesy National Archives of Australia.

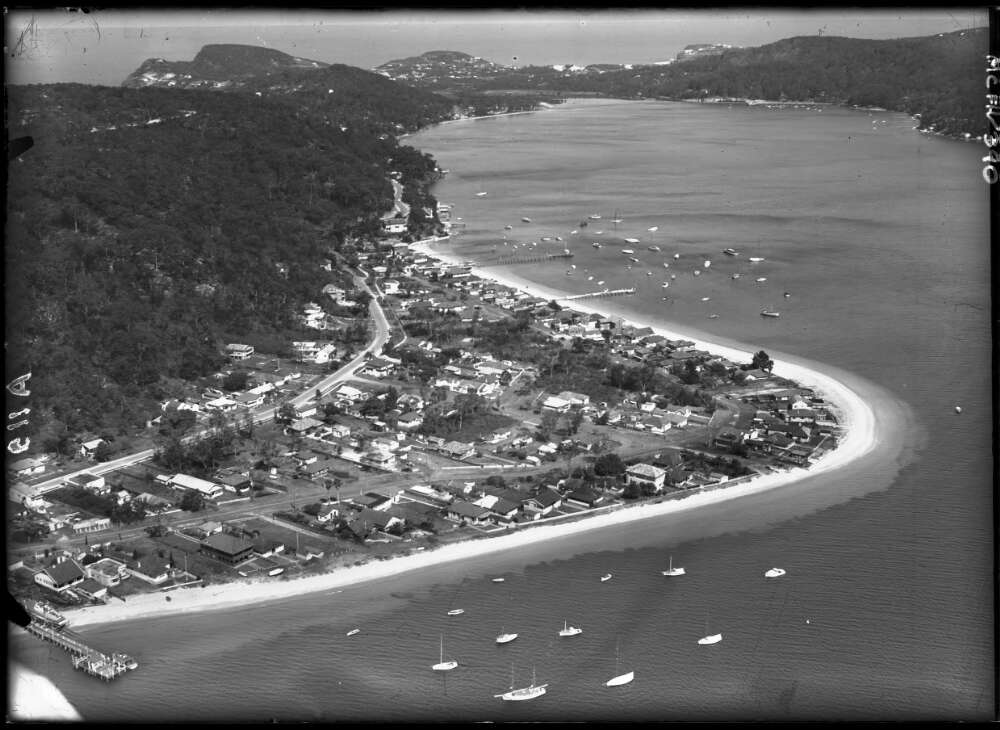

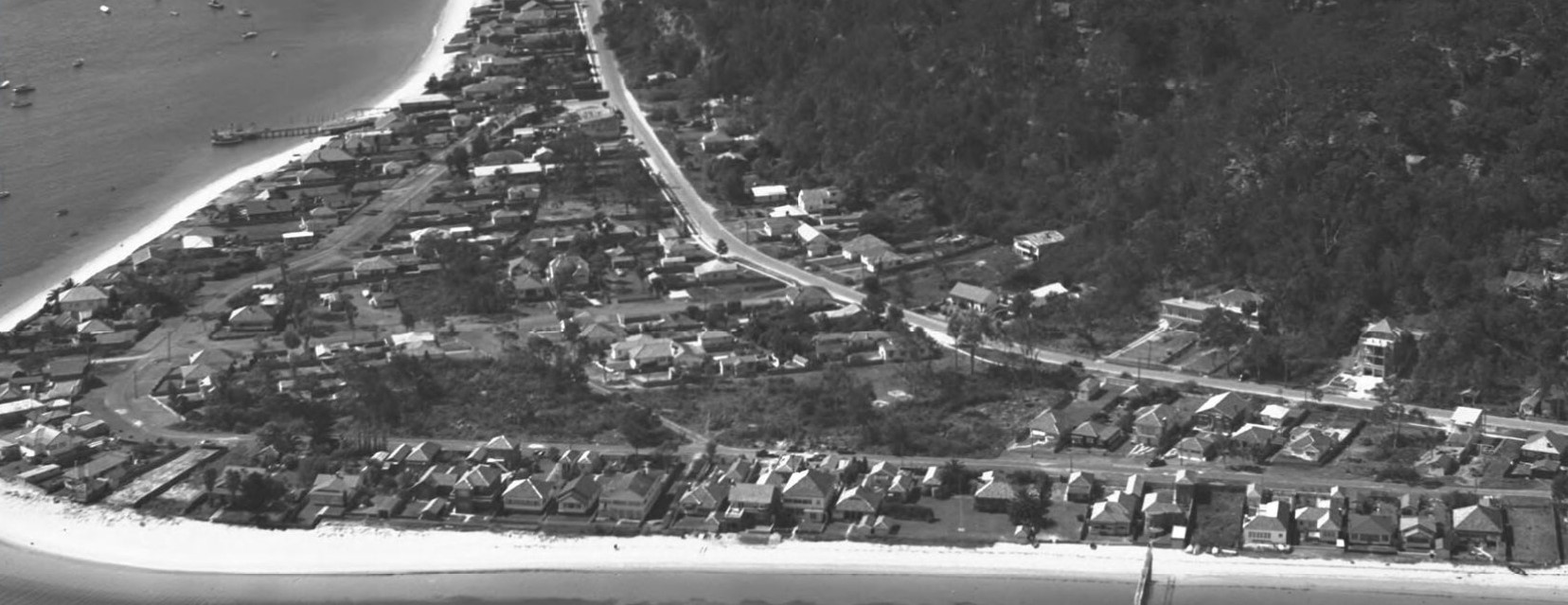

Another Petrov safe house, according to a 2016 interview with Steve Fitzmaurice of Fitzmaurice Property Group Avalon, was 137 George Street Avalon Beach, while a third in Pittwater was what was called 'Towlers Bay Cottage', also the scene for a Liberal Party conference later on.

After speaking with ASIO, the Museum of Democracy in Canberra, the National Archives and Geoff Searl OAM, President of the Avalon Beach Historical Society, Mr Fitzmaurice discovered there were four Petrov safehouses on the north shore of Sydney. They were in Avalon Beach, Towlers Bay on Pittwater, Berrys Bay in North Sydney and Palm Beach.

“The safehouses were ‘compulsory acquisitions’ and the government only held them for 18-months,” he told news.com.au.

This article states:

''...the big giveaway for 137 George Street was the contract of sale. We thought if it was a compulsory acquisition it must have been bought in 1954 and sold in 1956 and sure enough, in the contract for sale that is exactly what happened.”

The other clue came from an aerial photograph he received from the Avalon Historical Society.

“[The President of the Avalon Historical Society] has an aerial photograph of 1955,” Mr Fitzmaurice said.

“A lot of articles came out of the National Archives ... which named the street that [the safe houses] were in and they had said there was a safe house in George Street, they just hadn’t put numbers on it. But when you look at the aerial shot at the end of George Street in Careel Bay, there is only one house there — so it became fairly obvious.”

The final piece of evidence that makes Mr Fitzmaurice certain number 137 is a home for the history books is the secret trap door, which is hidden under built-in seating.

“It also has that very strange trap door. That is a room — quite a big room — which has no other access and no windows, and the only way to get to it is through that library seat which you lift up, open the trap door and there is a ladder down there,” Mr Fitzmaurice stated

“It is a fair assumption that if the KGB turned up, they would have shoved the Petrovs down that hole.”

Beneath those built-in those library chairs lies a trap door leading to secret, windowless room not shown on the floor plan. Photo Source: Domain real estate listings and Fitzmaurice Property Group Avalon

What's interesting about those four safe houses Mr. Fitzmaurice's research turned up is that they were all on or close to the water, providing opportunities for escape should that be required.

137 George Street - Petrov safe house. Photo Source: Domain real estate listings and Fitzmaurice Property Group Avalon

outlook over Careel Bay from Avalon 'safe house' for the Petrovs. Photo Source: Domain real estate listings and Fitzmaurice Property Group Avalon

137 George Street - Petrov safe house. Photo Source: Domain real estate listings and Fitzmaurice Property Group Avalon

Vladimir Petrov’s life after defection was not the utopia he had imagined. Petrov, despite his relatively junior diplomatic status, was a colonel in (what became in 1954) the KGB, the Soviet secret police, and his wife was an officer at the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD). The Petrovs had been sent to the Canberra embassy in 1951 by the Soviet security chief, Lavrentiy Beria. After Joseph Stalin's death in March 1953, Beria had been arrested and shot by Stalin's successors, and Vladimir Petrov evidently feared that, if he returned to the Soviet Union, he would be purged as a "Beria man". For many years he lived in fear of assassination, haunted by what he knew of the death of Leon Trotsky at the hands of a Soviet assassination squad, as well as what some refer to as being Beria's man. According to Michael Thwaites, who ghost wrote Petrov's ''Empire of Fear'', Soviet ambassadors Lifanov and Generalov had accused the Petrovs of trying to set up a Beria group in the embassy. Vladimir Petrov was due to return to Russia but feared for his life.

Other sources state Petrov applied for political asylum on the grounds that he could provide information regarding a Soviet spy ring operating out of the Soviet Embassy in Australia. Petrov states in his memoirs that his reasoning for defecting lay not in an imminent fear of being executed, but in his disillusionment with the Soviet system and his own experiences and knowledge of the terror and human suffering inflicted on the Soviet people by their government. He witnessed the destruction of the Siberian village in which he was born, caused by forced collectivization and the famine which resulted.

His job here was to recruit spies and to keep watch on Soviet citizens, making sure that none of the Soviets abroad defected, as well as feed information on British and US activities to his 'minders'. Ironically, it was in Australia where events would occur which led to his own defection from the USSR. This came about through his association with Polish-born doctor and musician Michael Bialoguski, who played along in seeming to allow Petrov to recruit him to gather information, while at the same time reporting to Australian Security Intelligence Organisation on Petrov's activities.

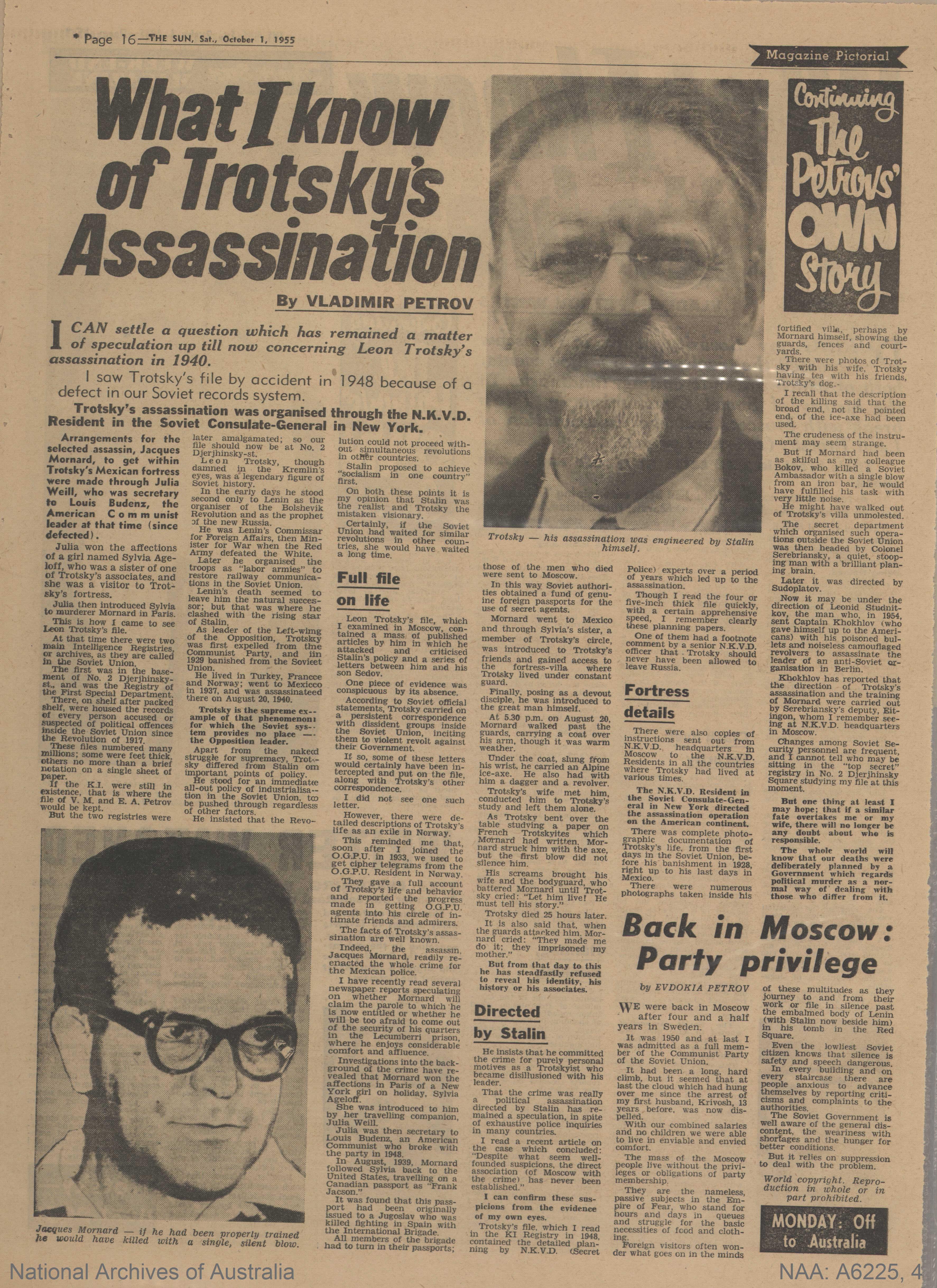

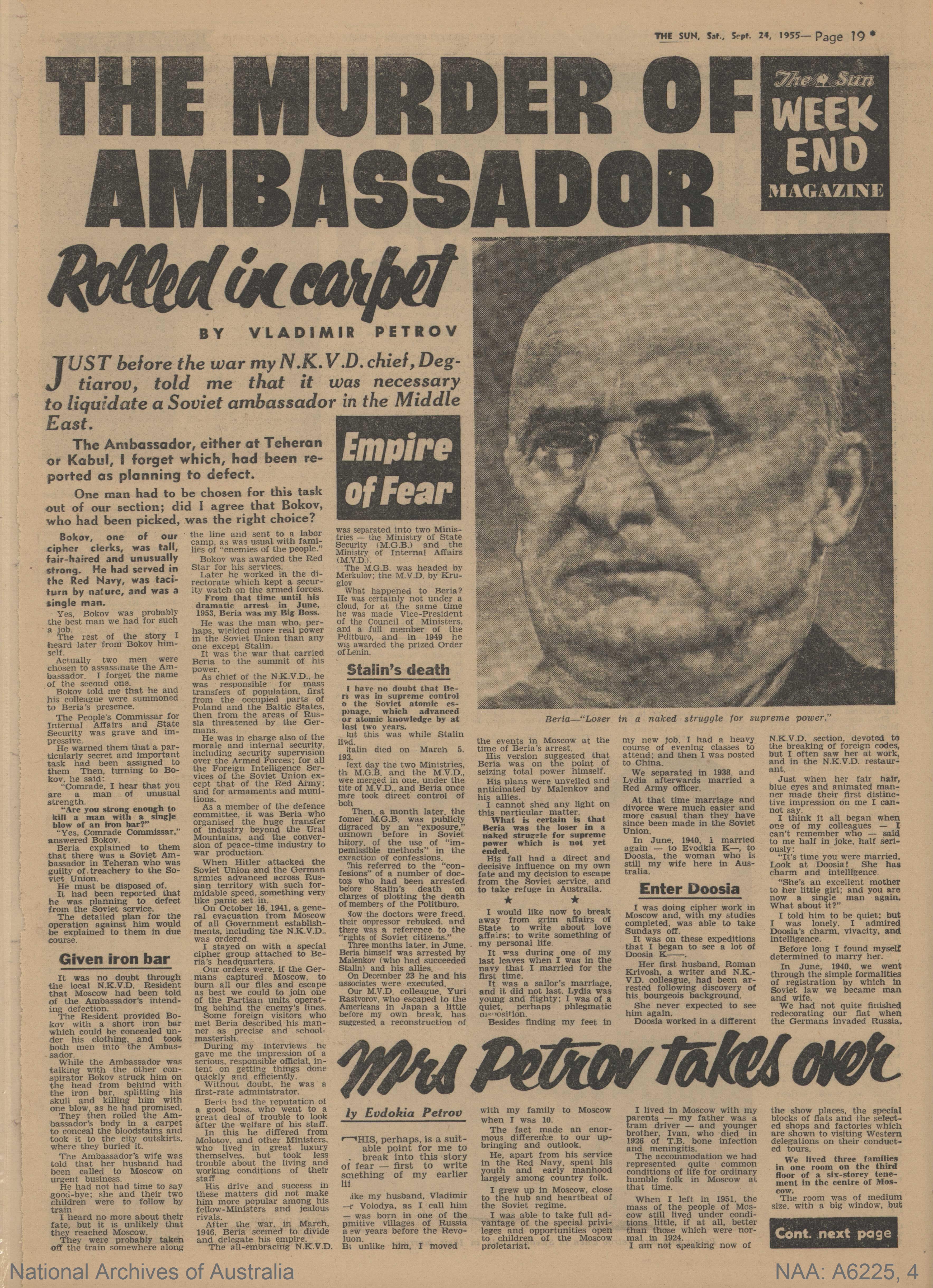

Increasingly fearful, Petrov rarely left the safe house, except to go hunting or fishing – his favourite pastimes. The newspapers of the day charted their thoughts and life before Australia and after defection:

The money Petrov was led to believe he would make from publishing a book in 1956 on this story, ''Empire of Fear'' did not eventuate, possibly because much of it had been published in the newspapers beforehand. The Petrovs became Australian citizens in 1956 and lived in suburban Melbourne. Petrov was given the name ‘Sven Allyson’. Ironically he found work developing film for Ilford Photographics. He had previously processed his instructions from Moscow from undeveloped film.

ASIO continued to interview the Petrovs for many years and the information they provided about methods of Soviet espionage was of great value to Western intelligence. Apart from providing information on the organisational structure of Soviet intelligence, they were able to identify (from photos) over five hundred Soviet agents.

Vladimir Petrov passed away in 1991. His wife was unable to attend his funeral because of an unremitting media presence.

Evdokia was more content with life in Australia than her husband, although for many years she was haunted by thoughts of the fate of her family in Moscow. She believed they had been punished or even killed because of her defection. In 1960 Evdokia was re-connected with her family through the Red Cross. She learned that her father had been sacked from his job after her defection and had died three years later. Her mother and herself corresponded until her mother’s death in 1965. Evdokia was finally reunited with her sister Tamara, who migrated with her family to Australia in 1990.

It was painful, painful. Because still somewhere, somewhere inside of me or in my husband always some kind of feeling that you left your country and you feel that you are just a defector. - Evdokia, 1996

With the £5,000 they received from the Australian Government and book sales, the Petrovs bought a home in Bentleigh, a suburb of Melbourne, in 1956. They lived under the protection of a D-Notice – an agreement between media and Government to protect their identity and privacy. The media did not always respect this agreement, especially after it was lifted in 1982. Occasionally Evdokia had to escape journalists by slipping through a gate in the back fence with the help of neighbours.

Evdokia, now ‘Maria Anna Allyson’, found work as a typist with William Adams Tractors. She outlived her husband by 11 years and passed away in July 2002 at the age of 87.

The Petrovs were reportedly moved around frequently to keep them safe although, from the images and records made available through the National Archives of Australia, it would seem they spent most of their time during the Autumn and Winter of 1954 at Palm Beach, finally able to exhale and enjoy the freedom many of us take for granted.

Notes: Who Was Ruling Russia When The Petrovs Defected?

After Stalin’s death in 1953, a power struggle for leadership ensued, which was won by Nikita Khrushchev. His landmark decisions in foreign policy and domestic programs markedly changed the direction of the Soviet Union, bringing détente with the West and a relaxation of rigid controls within the country. Khrushchev, who rose under Stalin as an agricultural specialist, was a Russian who had grown up in Ukraine. During his reign Ukrainians prospered in Moscow. He took it for granted that Russians had a natural right to instruct less-fortunate nationals. This was especially evident in the non-Slavic republics of the U.S.S.R. and in eastern and south-eastern Europe. His nationality policies reversed the repressive policies of Stalin. He grasped the nettle of the deported nationalities and rehabilitated almost all of them; the accusations of disloyalty made against them by Stalin were declared to be false. This allowed many nationalities to return to their homelands within Russia, the Volga Germans being a notable exception. (Their lands had been occupied by Russians who, fearing competition from the Germans, opposed their return.) The Crimean Tatars were similarly not allowed to return to their home territory. Their situation was complicated by the fact that Russians and Ukrainians had replaced them in Crimea, and in 1954 Khrushchev made Ukraine a present of Crimea. Khrushchev abided by the nationality theory that suggested that all Soviet national groups would come closer together and eventually coalesce; the Russians, of course, would be the dominant group. The theory was profoundly wrong. There was in fact a flowering of national cultures during Khrushchev’s administration, as well as an expansion of technical and cultural elites.

Khrushchev sought to promote himself through his agricultural policy. As head of the party Secretariat (which ran the day-to-day affairs of the party machine) after Stalin’s death, he could use that vehicle to promote his campaigns. Pravda (“Truth”), the party newspaper, served as his mouthpiece. His main opponent in the quest for power, Georgy M. Malenkov, was skilled in administration and headed the government. Izvestiya (“News of the Councils of Working People’s Deputies of the U.S.S.R.”), the government’s newspaper, was Malenkov’s main media outlet. Khrushchev’s agricultural policy involved a bold plan to rapidly expand the sown area of grain. He chose to implement this policy on virgin land in the north Caucasus and west Siberia, lying in both Russia and northern Kazakhstan. The Kazakh party leadership was not enamoured of the idea, since they did not want more Russians in their republic. The Kazakh leadership was dismissed, and the new first secretary was a Malenkov appointee; he was soon replaced by Leonid I. Brezhnev, a Khrushchev protégé who eventually replaced Khrushchev as the Soviet leader. Thousands of young communists descended on Kazakhstan to grow crops where none had been grown before.

Khrushchev’s so-called “secret speech” at the 20th Party Congress in 1956 had far-reaching effects on both foreign and domestic policies. Through its denunciation of Stalin, it substantially destroyed the infallibility of the party. The congress also formulated ideological reformations, which softened the party’s hard-line foreign policy. De-Stalinization had unexpected consequences, especially in eastern and southeastern Europe in 1956, where unrest became widespread. The Hungarian uprising in that year was brutally suppressed, with Yury V. Andropov, Moscow’s chief representative in Budapest, revealing considerable talent for double-dealing. (He had given a promise of safe conduct to Imre Nagy, the Hungarian leader, but permitted, or arranged for, Nagy’s arrest.) The events in Hungary and elsewhere stoked up anti-Russian fires.

Khrushchev had similar failures and triumphs in foreign policy outside the eastern European sphere. Successes in space exploration under his regime brought great applause for Russia. Khrushchev improved relations with the West, establishing a policy of peaceful coexistence that eventually led to the signing of the Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty of 1963. But he was at times eccentric and blunt, traits that sometimes negated his own diplomacy. On one occasion he appeared at the United Nations and, in his speech, emphasized his point by banging a shoe on his desk. Such conduct tended to reinforce certain Western prejudices about oafish, peasant behaviour by Soviet leaders and harmed the Russian image abroad. Khrushchev’s offhanded remarks occasionally caused massive unrest in the world. He told the United States, “We will bury you,” and boasted that his rockets could hit a fly over the United States, statements that added to the alarm of Americans, who subsequently increased their defence budget. Hence, he turned out to be his own worst enemy, accelerating the arms race with the United States rather than decelerating it, which was his underlying objective. His alarmingly risky policy of installing nuclear weapons in Cuba for local Soviet commanders to use should they perceive that the Americans were attacking brought the world seemingly close to the brink of nuclear war.

Khrushchev was a patriot who genuinely wanted to improve the lot of all Soviet citizens. Under his leadership there was a cultural thaw, and Russian writers who had been suppressed began to publish again. Western ideas about democracy began to penetrate universities and academies. These were to leave their mark on a whole generation of Russians, most notably Mikhail Gorbachev, who later became the last leader of the Soviet Union. Khrushchev had effectively led the Soviet Union away from the harsh Stalin period. Under his rule Russia continued to dominate the union but with considerably more concern for minorities. Economic problems, however, continued to plague the union. Khrushchev attempted to reform the industrial ministries and their subordinate enterprises but failed. He discovered that industrial and local political networks had developed, which made it very difficult for the central authority to impose its will. Under him there was a gradual dissipation of power from Moscow to the provinces. This strengthened the Russian regions. The agricultural policy, which was successful for a few years, eventually fell victim to lean drought years, causing widespread discontent.

Stalin's office records show meetings at which Khrushchev was present as early as 1932. The two increasingly built a good relationship. Khrushchev greatly admired the dictator and treasured informal meetings with him and invitations to Stalin's dacha, while Stalin felt warm affection for his young subordinate. Beginning in 1934, Stalin began a campaign of political repression known as the Great Purge, during which many were executed or sent to the Gulag. Central to this campaign were the Moscow Trials, a series of show trials of the purged top leaders of the party and the military. In 1936, as the trials proceeded, Khrushchev expressed his vehement support:

Everyone who rejoices in the successes achieved in our country, the victories of our party led by the great Stalin, will find only one word suitable for the mercenary, fascist dogs of the Trotskyite-Zinovievite gang. That word is execution.

Khrushchev assisted in the purge of many friends and colleagues in Moscow oblast. Of 38 top Party officials in Moscow city and province, 35 were killed—the three survivors were transferred to other parts of the USSR. Of the 146 Party secretaries of cities and districts outside Moscow city in the province, only 10 survived the purges. In his memoirs, Khrushchev noted that almost everyone who worked with him was arrested. By Party protocol, Khrushchev was required to approve these arrests, and did little or nothing to save his friends and colleagues.

When Soviet troops, pursuant to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, invaded the eastern portion of Poland on September 17 1939, Khrushchev accompanied the troops at Stalin's direction. A large number of ethnic Ukrainians lived in the invaded area, much of which today forms the western portion of Ukraine. Many inhabitants therefore initially welcomed the invasion, though they hoped that they would eventually become independent. Khrushchev's role was to ensure that the occupied areas voted for union with the USSR. Through a combination of propaganda, deception as to what was being voted for, and outright fraud, the Soviets ensured that the assemblies elected in the new territories would unanimously petition for union with the USSR. When the new assemblies did so, their petitions were granted by the USSR Supreme Soviet, and Western Ukraine became a part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukrainian SSR) on 1 November 1939. Clumsy actions by the Soviets, such as staffing Western Ukrainian organizations with Eastern Ukrainians, and giving confiscated land to collective farms (kolkhozes) rather than to peasants, soon alienated Western Ukrainians, damaging Khrushchev's efforts to achieve unity.

When Nazi Germany invaded the USSR, in June 1941, Khrushchev was still at his post in Kiev.[55] Stalin appointed him a political commissar, and Khrushchev served on a number of fronts as an intermediary between the local military commanders and the political rulers in Moscow. Stalin used Khrushchev to keep commanders on a tight leash, while the commanders sought to have him influence Stalin.

As the Germans advanced, Khrushchev worked with the military to defend and save Kiev. Handicapped by orders from Stalin that under no circumstances should the city be abandoned, the Red Army was soon encircled by the Germans. While the Germans stated they took 655,000 prisoners, according to the Soviets, 150,541 men out of 677,085 escaped the trap. Primary sources differ on Khrushchev's involvement at this point. According to Marshal Georgi Zhukov, writing some years after Khrushchev fired and disgraced him in 1957, Khrushchev persuaded Stalin not to evacuate troops from Kiev. However, Khrushchev noted in his memoirs that he and Marshal Semyon Budyonny proposed redeploying Soviet forces to avoid the encirclement until Marshal Semyon Timoshenko arrived from Moscow with orders for the troops to hold their positions. Early Khrushchev biographer Mark Frankland suggested that Khrushchev's faith in his leader was first shaken by the Red Army's setbacks.

Almost all of Ukraine had been occupied by the Germans, and Khrushchev returned to his domain in late 1943 to find devastation. Ukraine's industry had been destroyed, and agriculture faced critical shortages. Even though millions of Ukrainians had been taken to Germany as workers or prisoners of war, there was insufficient housing for those who remained. One out of every six Ukrainians were killed in World War II.

Khrushchev sought to reconstruct Ukraine but also desired to complete the interrupted work of imposing the Soviet system on it, though he hoped that the purges of the 1930s would not recur. As Ukraine was recovered militarily, conscription was imposed, and 750,000 men aged between nineteen and fifty were given minimal military training and sent to join the Red Army. Other Ukrainians joined partisan forces, seeking an independent Ukraine. Khrushchev rushed from district to district through Ukraine, urging the depleted labor force to greater efforts. He made a short visit to his birthplace of Kalinovka, finding a starving population, with only a third of the men who had joined the Red Army having returned. Khrushchev did what he could to assist his hometown. Despite Khrushchev's efforts, in 1945, Ukrainian industry was at only a quarter of pre-war levels, and the harvest actually dropped from that of 1944, when the entire territory of Ukraine had not yet been retaken.

In an effort to increase agricultural production, the kolkhozes (collective farms) were empowered to expel residents who were not pulling their weight. Kolkhoz leaders used this as an excuse to expel their personal enemies, invalids, and the elderly, and nearly 12,000 people were sent to the eastern parts of the Soviet Union. Khrushchev viewed this policy as very effective and recommended its adoption elsewhere to Stalin. He also worked to impose collectivization on Western Ukraine. While Khrushchev hoped to accomplish this by 1947, lack of resources and armed resistance by partisans slowed the process. The partisans, many of whom fought as the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), were gradually defeated, as Soviet police and military reported killing 110,825 "bandits" and capturing a quarter million more between 1944 and 1946. About 600,000 Western Ukrainians were arrested between 1944 and 1952, with one-third executed and the remainder imprisoned or exiled to the east.

Khrushchev's final years in Ukraine were generally peaceful, with industry recovering, Soviet forces overcoming the partisans, and 1947 and 1948 seeing better-than-expected harvests. Collectivization advanced in Western Ukraine, and Khrushchev implemented more policies that encouraged collectivization and discouraged private farms. These sometimes backfired, however: a tax on private livestock holdings led to peasants slaughtering their stock.] With the idea of eliminating differences in attitude between town and countryside and transforming the peasantry into a "rural proletariat", Khrushchev conceived the idea of the "agro-town". Rather than agricultural workers living in villages close to farms, they would live further away in larger towns which would offer municipal services such as utilities and libraries, which were not present in villages. He completed only one such town before his December 1949 return to Moscow; he dedicated it to Stalin as a 70th birthday present.

In his memoirs, Khrushchev spoke highly of Ukraine, where he governed for over a decade:

I'll say that the Ukrainian people treated me well. I recall warmly the years I spent there. This was a period full of responsibilities, but pleasant because it brought satisfaction ... But far be it from me to inflate my significance. The entire Ukrainian people was exerting great efforts ... I attribute Ukraine's successes to the Ukrainian people as a whole. I won't elaborate further on this theme, but in principle, it's very easy to demonstrate. I'm Russian myself, and I don't want to offend the Russians.

On March 1st 1953, Stalin suffered a massive stroke. As terrified doctors attempted treatment, Khrushchev and his colleagues engaged in an intense discussion as to the new government. On March 5th, Stalin died. Khrushchev later reflected on Stalin:

Stalin called everyone who didn't agree with him an "enemy of the people." He said that they wanted to restore the old order, and for this purpose, "the enemies of the people" had linked up with the forces of reaction internationally. As a result, several hundred thousand honest people perished. Everyone lived in fear in those days. Everyone expected that at any moment there would be a knock on the door in the middle of the night and that knock on the door would prove fatal ... [P]eople not to Stalin's liking were annihilated, honest party members, irreproachable people, loyal and hard workers for our cause who had gone through the school of revolutionary struggle under Lenin's leadership. This was utter and complete arbitrariness. And now is all this to be forgiven and forgotten? Never!

After Stalin's death, Beria launched a number of reforms. According to Taubman, "unparalleled in his cynicism, he [Beria] did not let ideology stand in his way. Had he prevailed, he would almost certainly have exterminated his colleagues, if only to prevent them from liquidating him. In the meantime, however, his burst of reforms rivalled Khrushchev's and in some ways even Gorbachev's thirty-five years later." One proposal, which was adopted, was an amnesty which eventually led to the freeing of over a million non-political prisoners. Another, which was not adopted, was to release East Germany into a united, neutral Germany in exchange for compensation from the West—a proposal considered by Khrushchev to be anti-communist. Khrushchev allied with Malenkov to block many of Beria's proposals, while the two slowly picked up support from other Presidium members. Their campaign against Beria was aided by fears that Beria was planning a military coup, and, according to Khrushchev in his memoirs, by the conviction that "Beria is getting his knives ready for us." The key move by Khrushchev and Malenkov was to lure two of Beria's most powerful deputy ministers, Sergei Kruglov and Ivan Serov, to betray their boss. This allowed Khrushchev and Malenkov to arrest Beria as Beria belatedly discovered he had lost control of Ministry of Interior troops and the troops of the Kremlin guard. On 26 June 1953, Beria was arrested at a Presidium meeting, following extensive military preparations by Khrushchev and his allies. Beria was tried in secret and executed in December 1953 with five of his close associates.

This alone would be why Mr. Petrov was not anxious to return to Russia.

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria was the longest-lived and most influential of Stalin's secret police chiefs, wielding his most substantial influence during and after World War II. Following the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, he was responsible for organising purges such as the Katyn massacre of 22,000 Polish officers and officials. Beria would later also orchestrate the forced upheaval of minorities from the Caucasus as head of NKVD, an act that was declared as genocidal by various scholars and, as concerning Chechens, in 2004 by the European parliament.

He simultaneously administered vast sections of the Soviet state, and acted as the de facto Marshal of the Soviet Union in command of NKVD field units responsible for barrier troops and Soviet partisan intelligence and sabotage operations on the Eastern Front during World War II. Beria administered the expansion of the Gulag labour camps, and was primarily responsible for overseeing the secret detention facilities for scientists and engineers known as sharashkas.

After the war, he organised the communist takeover of the state institutions in central and eastern Europe. Beria's ruthlessness in his duties and skill at producing results culminated in his success in overseeing the Soviet atomic bomb project. Stalin gave it absolute priority, and the project was completed in under five years.

After Stalin's death in March 1953, Beria became First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers and head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In this dual capacity, he formed a troika with Georgy Malenkov and Vyacheslav Molotov that briefly led the country in Stalin's place.

The coup d'état by Nikita Khrushchev, with help from Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgy Zhukov, in June 1953 removed Beria from power. After being arrested, he was tried for treason and other offenses, sentenced to death, and executed on December 23rd 1953.

Notes sourced from Encyclopaedia Britannica and Wikipedia