July 23 - 29 2023: Issue 591

ARC Training Centre To Advance Australia’s Transition To A Sustainable Plastic Future Officially Opened + Research Tests Whether Bioplastics Break Down In Moreton Bay + CSIRO's Free Program Empowers SMEs To Innovate Plastic Waste Solutions; Apply Now + New CSIRO Book: Ending Plastic Waste: Community Actions Around the World + Plastic pollution threatens birds far out at sea – new research

Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, is on a mission to end plastic waste and is providing free research and development (R&D) support to businesses working in the plastic and recycling sector.

Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) working on advanced solutions to innovate plastic waste are invited to apply for the free, ten-week Innovate to Grow program, offered by CSIRO, to support their commercial idea by building their R&D knowledge.

CSIRO has a goal to reduce 80 per cent of plastic waste entering the Australian environment by 2030. The Ending Plastic Waste Mission is intended to support a sustainable plastics circular economy to reduce detrimental impacts to the environment, while delivering economic benefits.

CSIRO’s Ending Plastic Waste Mission Lead Dr Deborah Lau said it’s only by bringing science and industry together that we can revolutionise plastic waste.

“Each year, 90 billion tonnes of primary materials are extracted and used globally for plastics, with only 9 per cent recycled. This is commercially unsustainable,” Dr Lau said.

"It’s important we work collaboratively with SMEs and facilitate access to R&D opportunities to help accelerate scientific advancements and cutting-edge technology to address the plastic pollution problem.

“SMEs play a key role in driving Australia’s circular economy and new industries. This program will help facilitate innovation to drive future pathways for managing plastic waste.”

George Feast, Deputy Director of CSIRO’s SME Connect, encouraged SMEs to get on board by taking advantage of free expertise, to help translate their ideas into viable commercial opportunities.

“R&D can be an expensive undertaking for businesses and risky for those without the right guidance and support,” Mr Feast said.

“To address these challenges, we’re inviting participants to come with a specific plastic or recycling idea they’d like to explore.

“Over 10 weeks CSIRO experts will guide businesses through how to refine their idea, to understand its research viability, and begin the process of engaging a university or research institution to deliver a collaborative R&D project.”

Upon completion of the program, eligible participants may have the opportunity to access facilitation support, through CSIRO, to connect to research expertise nationally, along with dollar-matched R&D funding.

Innovate to Grow: Ending Plastic Waste is open to SMEs working in the following sub-sectors:

- Plastic processor or converter

- Plastic waste collection/sorting

- Plastic recycling

- Packaging

- Agriculture and food

- Manufacturing

- Other

CSIRO’s Innovate to Grow: Ending Plastic Waste program, commencing 7 September, is available for up to 20 SMEs. Applications close 14 August 2023.

ARC Training Centre To Advance Australia’s Transition To A Sustainable Plastic Future Officially Opened

July 18, 2023

Today, Australian Research Council (ARC) Deputy Chief Executive Officer Dr Richard Johnson launched the ARC Training Centre for Bioplastics and Biocomposites.

Led by The University of Queensland, the ARC Training Centre aims to deliver cutting edge research with a holistic focus on technical, social, and policy solutions.

Through a highly collaborative process of co-design, co-production and co-delivery of knowledge and technology, the research team at the ARC Training Centre will be conducting research across four interconnected themes - Bioresource Transformation, Bioplastic Manufacture, Bioplastic Applications, and Change and Sustainability.

Dr Johnson said that the ARC Training Centre is fundamental to strengthening the capabilities of Australian industry to service rapidly growing national and international markets in bio-derived and biodegradable products.

“The ARC Training Centre for Bioplastics and Biocomposites will capitalise on Australia’s substantial bioresources to develop bioderived and biodegradable plastics and composites, such as high-performing think barrier films that are completely biodegradable, supporting two Industrial Transformation Priorities – Advanced Manufacturing, and Food and Agribusiness,” Dr Johnson said.

“ARC Training Centres are funded under the ARC’s Industrial Transformation Research Program. Training Centres, such as this one, are essential to increasing collaboration between Australia’s most innovative researchers and industries.”

The ARC Training Centre will train a cohort of industry-ready research specialists to underpin Australia’s transition to a globally significant bioplastic and biocomposites industry, expecting to attract 19 PhD Students, 19 Researchers, and 4 Research Fellows.

The ARC is investing $4.9 million over 5 years under the ARC Industrial Transformation Research Program.

For more information about the ARC Training Centre for Bioplastics and Biocomposites, please visit their website.

For more information about ARC Industrial Transformation Training Centres, please visit the ARC website.

Research Tests Whether Bioplastics Break Down In Moreton Bay

July 19, 2023

A major study in Southeast Queensland is testing how quickly biodegradable plastics break down in waterways, as researchers search for solutions to the world's growing plastics problem.

The project is underway at the $13 million Australian Research Council Training Centre for Bioplastics and Biocomposites at The University of Queensland, which has been officially opened by the Deputy Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Research Council, Dr Richard Johnson.

Director, Associate Professor Steven Pratt said the Centre was responding to unprecedented growth in demand for bioderived and biodegradable products with more than 10 million tonnes of plastic waste accumulating in oceans each year.

“One of the aims is to develop products that are capable of biodegrading in ambient environments to avoid the accumulation of micro and nanoplastics,” Dr Pratt said.

“The prospect of manufacturing a commercially available plastic with exceptional properties, but without the adverse legacy for the environment, is an exciting one.

“We’re well placed to do this in Australia as we have an abundance of natural bioresources – such as organic wastes – that are needed for manufacturing these products.”

UQ Vice Chancellor Professor Deborah Terry said experts at the Centre were working to develop commercial solutions that meet the needs of businesses, consumers, and the environment.

“We’re working alongside industry and government partners to deliver advances in the production and manufacture of the ‘bioplastics of the future’,” Professor Terry said.

“One of the strategies to deal with the longevity of plastics is to switch to biodegradable alternatives, but we need to know more about how they behave in the natural environment.

“There is a lot of research on what happens to biodegradable plastic in soil, compost, on land, and in landfills, but we actually don’t know what happens when these materials enter the marine environment.”

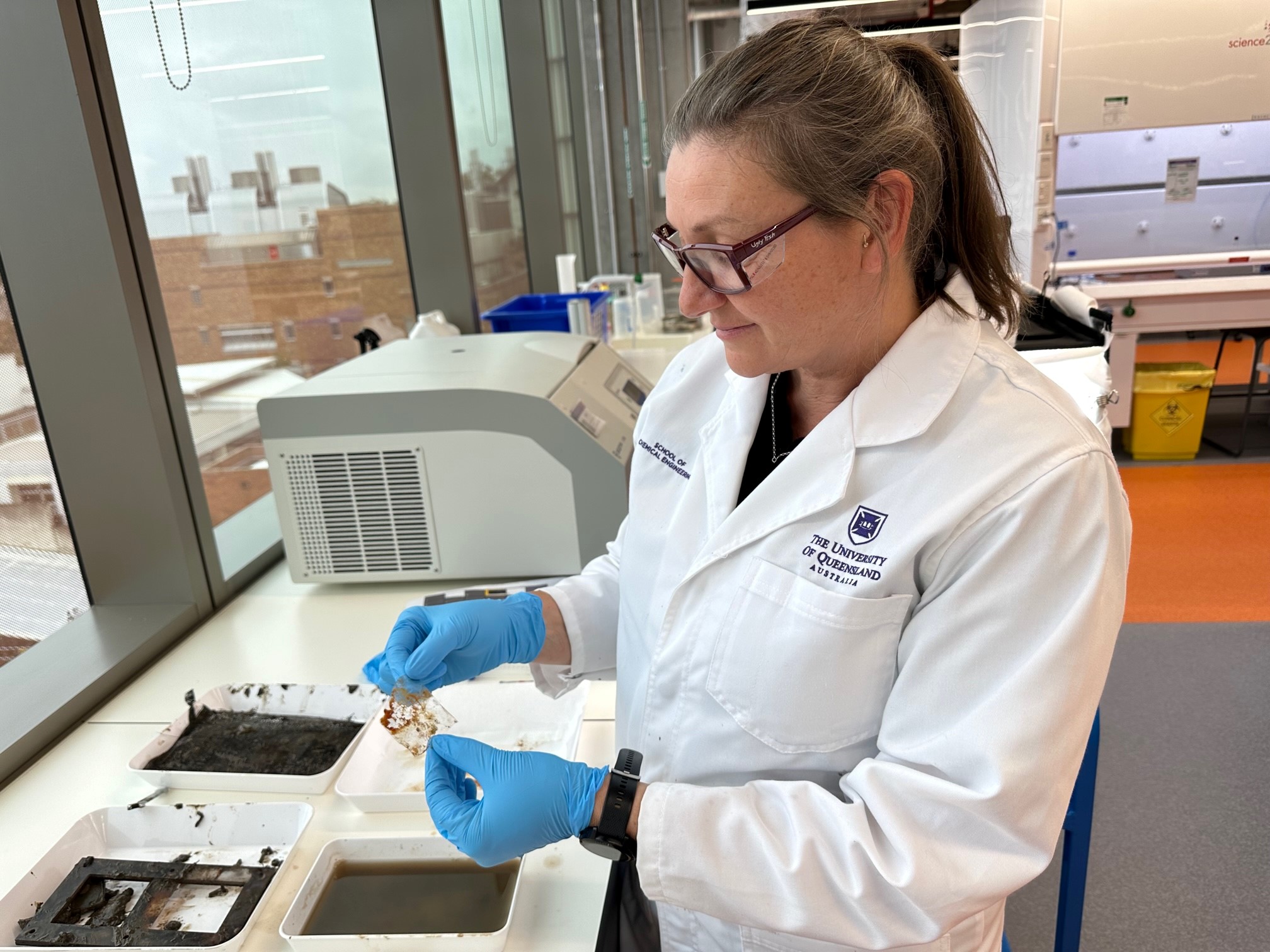

UQ PhD candidate Tracey Read has taken up this challenge and is examining how biodegradable plastics, like packaging and plastic bags, react in water.

PhD candidate Tracey Read checking samples at Sea World on the Gold Coast. Photo: UQ

More than 2,000 samples of varying types and thicknesses have been submerged at four southeast Queensland sites, including Dunwich in Moreton Bay, Rivergate Marina in the Brisbane River and Spinnaker Sound Marina in Pumicestone Passage.

The fourth location, above ground outdoor tanks located within a turtle rehabilitation area at Sea World on the Gold Coast, provides a more controlled environment.

Early results have found PHA plastics which are bioderived, degraded completely in water after 7 months but other bioplastics degraded by a little as one per cent in a year.

Full results will be published in the coming months.

The training centre is a partnership between UQ, QUT, the Queensland Government, Kimberly-Clark Australia, Plantic Technologies, Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation, Minderoo Foundation, and the City of Gold Coast.

Plastic sample being examined in the laboratory at the ARC Training Centre for Bioplastics and Biocomposites. Photo: UQ

EAIT Bioplastics Moreton Bay Research Site. Photo: UQ

Plastic Fantastic Initiatives Reducing Waste Across The Globe

July 3, 2023

A new book published by Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, shines a light on the creative and impactful ways communities across the globe are dealing with the plastic pollution crisis.

Released today, Ending Plastic Waste: Community Actions Around the World presents a collection of stories, advice and information from people in the field, and aims to serve as a source of inspiration to reduce plastic waste in the environment.

The book highlights 19 initiatives from 15 countries including Australia – including reusable menstrual products, thongs into artworks, and a recycling app to prevent waste ending up in landfill.

It’s estimated that global plastic production will double by 2040, and there are trillions of pieces of plastic already in our oceans.

CSIRO scientist and editor, Dr Denise Hardesty, said such is the scale of the problem that in June this year, countries from around the world came together to continue negotiations for the United Nations Environmental Programme global treaty to end plastic pollution.

“Plastic pollution is now considered a planetary crisis. The world is taking notice that we need to change our relationship with plastic and use plastic as a resource, rather than a waste,” Dr Hardesty said.

“It’s heartening to see how communities are managing plastic pollution in their local environment, delivering wins for the environment, the economy and livelihoods. We can all make a difference,” she said.

Ocean Sole: upcycling thong pollution (Kenya)

In Kenya, one million thongs are found as litter along its coastline per year. Ocean Sole is turning the discarded thongs into artworks.

Joe Mwakiremba from Ocean Sole said the organisation had recovered and upcycled over 559 tonnes of thong pollution since it began in 2006, using them to produce 65,000 artworks.

“The issue was so bad that turtles could no longer use some beaches to nest and lay eggs. Now, we have 15 coastal communities collecting thongs, resulting in economic benefits and cleaner beaches,” Joe Mwakiremba said.

Plastics Circle: circular economy for plastics (Australia/India)

Another program is the Plastics Circle. Founder Murray Hyde said the organisation has created an app to connect businesses to specific post-consumer recycled (PCR) plastic.

“Quality recyclables were going to waste in countries across Asia. The app creates a circular economy model so plastic can be used again, rather than going to landfill or ending up in our oceans,” Mr Hyde said.

“The app creates a market for PCR plastics with information on the plastic type, colour, condition, location and price so it can be used again,” he said.

The Plastics Circle was trialled in India, recovering almost 4000 kg of plastic over 67 collection days, equating. to almost six kilograms per person per day.

Natalie Harms is the Programme Officer on Marine Litter, Secretariat of the Coordinating Body on the Seas of East Asia (COBSEA), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

“Armed with knowledge and the stories told in this book, readers will feel inspired and empowered to create their own organisation and join us in our collective effort towards solving the global plastics pollution challenges.” Ms Harms said.

Ending Plastic Waste: Community Actions Around the World is available now.

CSIRO is on a mission to end plastic waste, with a goal of an 80 per cent reduction in plastic waste entering the Australian environment by 2030.

The book Ending Plastic Waste: Community Actions Around the World is available from CSIRO Publishing

Case studies highlighted in the book:

Plastic Collective – Australia

The Plastic Collective is a social enterprise to educate and equip remote communities with facilities to turn plastic waste into a resource.

Founder Louise Hardman has seen the impact of plastic first-hand. Rescuing a stranded turtle with a gut full of plastic inspired Louise to establish Resource Recovery Stations in communities to turn plastic into sellable recyclable material using a Shruder, which shreds plastic waste.

Each station has a target to recycle 200 tonnes of material per year. This provides economic, environmental, and societal benefits. It empowers communities with knowledge, particularly those with poor infrastructure, and high transport costs to manage waste.

Many of the resource recovery stations are currently operating across the Australian and South-East Asia region.

When a cyclone hit Vanuatu and supplies were cut off, Belinda Roselli pondered how women could manage through menstruation. This inspired Mamma’s Laef.

The organisation creates reusable hygiene products for women, offering a dignified and plastic free solution.

Local women manufacture reusable menstrual pads, incontinence aids and baby nappies. These are distributed to the local community across the island.

Mamma's Laef creates reuseable hygiene products for communities in need © Credit: Mamma's Laef

The Plastics Circle – Australia/ India

The Plastics Circle has created an app where brands and plastic processors can place orders for specific post-consumer recycled (PCR) plastic.

Quality recyclables were going to waste in countries across Asia. The app creates a plastics circular economy model so plastic can be used again, rather than going to landfill or ending up in our oceans.

The app shares information on the plastic type, colour, condition, location and price.

The commercial model has been piloted with success in India. Ten collectors recovered almost 4000 kg of plastic over 67 collection days – almost 6 kg per person per day.

One million thongs found as litter on Kenyan beaches per year have been turned into artworks through Ocean Sole.

Ocean Sole has recovered and upcycled over 559 tonnes of thong pollution since it began in 2006, with a record-breaking 65,000 artworks created.

Beaches in Kenya were littered with thongs. The issue had become so bad that turtles could no longer make nests on some beaches to lay their eggs.

15 coastal communities collect thongs. Ocean Sole then transforms the thong litter into collectable artwork, resulting in a thriving business, cleaner beaches, economic benefits and ocean conservation.

Ocean Sole is looking to scale the program to other countries, such as Brazil.

Ocean Sole collects discarded thongs and turns them into artworks © Eva Morel.

Australian Plastics Feeding Climate Crisis: Emissions To Double By 2050

July 10, 2023

- New research shows the plastics Australians consume in one year produce as much greenhouse gas as 5.7 million cars on our roads annually

- Australia’s plastic emissions will more than double by 2050 if we continue on current path

- Recycling alone won’t solve this problem – we must cut plastic use and stop using virgin plastic made from fossil fuels

- We can cut plastic emissions by up to 70% by cutting plastic use by just 10%, improving recycling rates and using renewable energy

The plastic consumed in Australia in just one year produces more greenhouse gas emissions than one third of our car fleet creates annually, according to groundbreaking research into the climate costs of Australia’s plastic addiction.

The report, produced by environmental consultants Blue Environment for the Australian Marine Conservation Society and WWF-Australia, shows that in 2020 Australia’s emissions from plastics created more than 16 million metric tonnes of greenhouse gases – equivalent to the emissions produced by 5.7 million cars on Australia’s roads annually.

If we continue on our current path of accelerating plastic consumption, the emissions from Australia’s plastics will more than double to 42.5 million tonnes annually by 2050 – the year Australia has legislated to reach net-zero emissions. The Center for International Environmental Law estimates plastics could account for up to 15% of the world’s carbon budget by 2050 if decisive action is not taken.

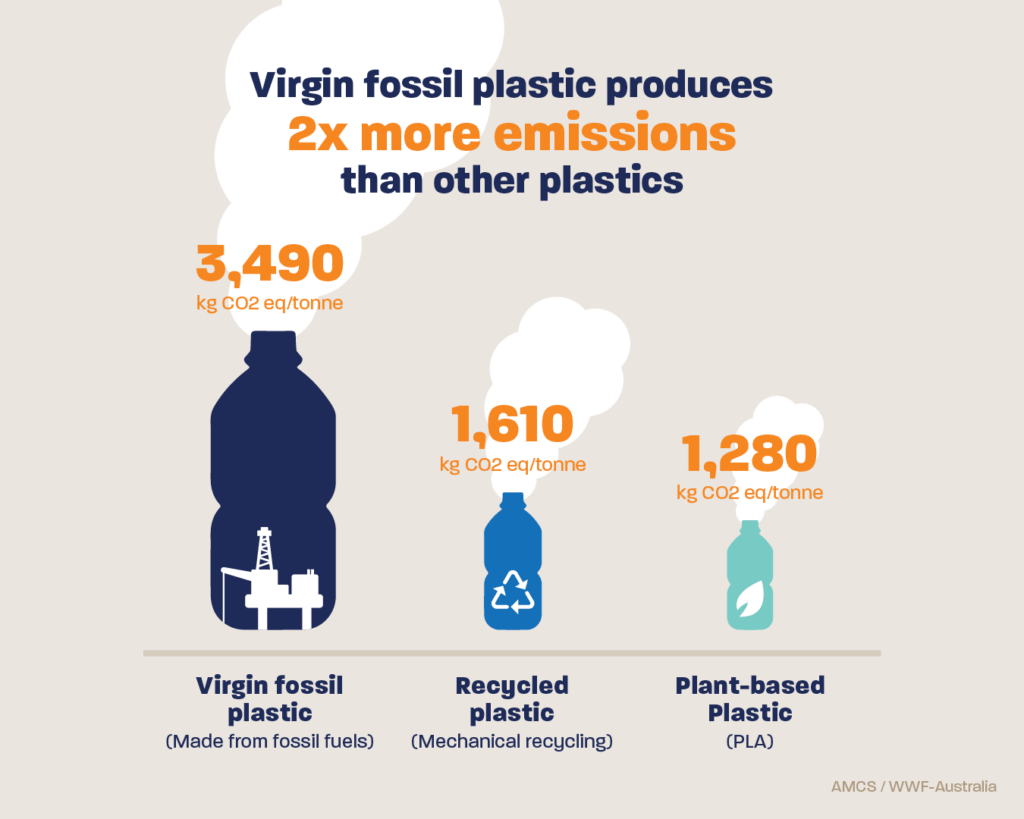

The report, Carbon emissions assessment of Australian plastics consumption, is the first major study to model the emissions associated with the production and disposal of plastics, including recycling, and what Australia can do to cut those emissions. The report shows that plastics produce significant emissions, and virgin plastics made from fossil fuels were the most emissions intensive to produce, creating more than double the emissions of any other plastic.

In Australia, we generate more single-use plastic waste per person than any other country except Singapore. The good news is that we can cut plastic consumption by 30% by 2040 through such approaches as banning plastic or increasing the use of reusables, before needing to substitute plastics with other materials.

AMCS Plastics Campaign Manager Shane Cucow said: “The findings are shockingly clear. We already knew runaway plastic use is creating mountains of waste and pollution, killing millions of animals every year through entanglement or ingestion. Now we have clear evidence it is also fuelling global warming, which is endangering our entire marine ecosystem.

“We must use less plastic, stop using fossil fuels to make it, and stop using fossil fuels as an energy source for plastic production and recycling. If we don’t, the emissions from plastic will only increase and exacerbate climate change.”

WWF-Australia No Plastics in Nature Policy Manager Kate Noble said: “We can’t rely on recycling solely to get us out of this mess; we need to drastically cut our plastic use and stop using virgin plastic made from fossil fuels. Even if we recycle 100% of the plastic we use, we’ll still see emissions double to more than 34 million tonnes annually by 2050.

“The good news is that we can reduce plastic waste and cut down the emissions from plastic at the same time. Reducing plastic consumption, combined with better design, using it longer, and managing it more responsibly, is the only way to bring our plastic addiction under control, and reduce the climate impacts of plastics at the same time.”

Cutting plastics emissions

The report modelled various scenarios including reducing plastics use, decoupling plastic production from fossil fuels, decarbonising energy systems globally, and significantly increasing recycling rates. Simply capping plastic production at current levels results in nearly a 40% fall in carbon emissions by 2050 relative to business as usual. Scenarios that solely rely on increasing recycling rates perform only marginally better than business as usual. Scenarios using renewable energy perform moderately well, and this is a key contributor to the combined scenarios that achieve high reductions in carbon emissions relative to BAU. Overall, the study findings strongly indicate that multiple complementary system level changes are required to significantly reduce the carbon emissions relating to plastics use.

Under a combined scenario, Australia could reduce the total emissions from its plastic use by up to 70% by 2050, with the greatest impact achieved by cutting plastics consumption by just 10%. We need to:

- use plastics more efficiently and cut total consumption by at least 10%,

- rapidly increase plastic recovery and recycling to 100%

- fully power plastics production and recycling with 100% renewable energy, and

- move away from virgin fossil-fuel based plastic entirely.

While these are ambitious goals that Australia is not currently equipped to meet, the report highlights the need for strong action on plastic consumption and waste management now, to avoid the growing waste, pollution and climate costs caused by skyrocketing plastic consumption.

Further findings

Greenhouse gas emissions from plastic production are higher than previously thought, due to substantive new research that indicates that methane from gas extraction and processing is at least 25-40% higher than estimates used by governments globally, which has been averaged to 32.5% for this report. This is likely to be an underestimate, with recent figures from the International Energy Agency putting the discrepancy at 70% higher than former estimates.

Manufacturing virgin fossil-fuel based plastics produces on average 3,490kg CO2e per tonne, more than double the emissions of producing new plastics through mechanical recycling (1,610kg CO2e/t) – 2.2 times the global warming potential (GWP) over GWP 20 years.

Fossil-fuel based plastics produce nearly three times the emissions to manufacture than plant-based plastics (1,280kg CO2e/t –2.7 times over GWP 20-year basis)

Incineration and burning plastics to produce energy are the most emissions intensive disposable methods for plastics.

Chemical recycling of plastics – where plastic waste is chemically treated to produce oil that can be used as fuel or remanufactured into plastic – is more emissions intensive than mechanical recycling, producing 67% more emissions than mechanical recycling.

Note: The emissions reduction scenarios modelled only refer to plastic emissions and do not consider the emissions of substituted products or other environmental harms caused by plastics. They are indicative projections only and further work is needed to identify technical pathways for reducing plastics consumption and increasing recovery.

The full report and report summary can be found at plasticemissions.org.au

Full report: Carbon emissions assessment of Australian plastics consumption – Project report

Summary report: Climate impacts of plastic consumption in Australia

Plastic pollution threatens birds far out at sea – new research

Seabirds are one of the world’s most threatened animal groups. They already contend with multiple issues, including climate change, accidental capture in fishing gear and being eaten by invasive species like cats and some rodents.

But these birds, which breed on land and forage for food at sea, are now facing another threat: plastic pollution. It’s becoming increasingly common to find seabirds that have ingested plastic as they forage for food.

A group of seabirds called petrels are particularly at risk. They roam vast areas of the ocean and cannot easily regurgitate the plastic they ingest. During the breeding season, they may even inadvertently feed this plastic to their chicks.

In our latest research, we tracked the movements of over 7,000 petrels of 77 different species. We combined this data with existing maps of marine plastic pollution to calculate an “exposure risk score” for each species. These scores enabled us to create a detailed picture of when and where seabirds are most at risk of encountering plastic pollution at sea.

We found that many species spend a lot of time in areas of the ocean with high concentrations of plastic. Plastic exposure risk was highest in enclosed seas where plastic can become trapped, such as the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. These regions accounted for over half of the global plastic exposure risk for petrels, potentially affecting all four of the species studied that forage there.

But many other petrel species are at risk of encountering plastic in remote parts of the ocean, including the north-west and north-east Pacific, south Atlantic and south-west Indian Ocean. This is mainly due to large systems of circulating ocean currents, called mid-ocean gyres, which transport plastic debris thousands of miles from its source – such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

In fact, one-quarter of petrels’ plastic exposure risk occurred in the high seas. These areas are not within any country’s jurisdiction, so international efforts are required to reduce the threat of plastic pollution to seabirds and other marine wildlife.

Vulnerable Birds

Plastic exposure risk varied depending on the species and whether it was breeding or non-breeding season. Notably, there were also differences in plastic exposure risk among populations of the same species.

Some already threatened species scored highly, including the critically endangered Balearic shearwater, which breeds in the Mediterranean. The Newell’s shearwater, which is endemic to Hawaii, was also at high risk of plastic exposure.

Another vulnerable species, the spectacled petrel, also scored high for plastic exposure risk. This species nests solely on an uninhabited volcanic island in the south Atlantic Ocean called Inaccessible Island.

Even species with low exposure risk, such as the northern fulmar and snow petrel, have in the past been found to eat plastic. This goes to show that oceanic plastic pollution poses a problem for seabirds worldwide, even outside of high exposure areas.

Plastic Pollution Is An Issue

Seabirds often swallow plastic by accident, mistaking it for their food. They also ingest plastic that has already been eaten by their prey.

This can lead to injury, poisoning from toxic chemicals that leach from the plastic and starvation as plastic fills up their stomach. Research from 2014 found that more than 60% of flesh-footed shearwater fledglings surpass international targets for plastic ingestion by seabirds. Worryingly, 16% of fledglings failed these targets after just one feeding.

Over time, plastic debris also breaks down into minuscule fragments called microplastics. Research has found that microplastic exposure can cause inflammation in a bird’s digestive system – a phenomenon called “plasticosis”.

We didn’t focus on the impact of plastic exposure on the petrel species studied, but many of these species are already threatened with extinction. Exposure to plastics may further reduce these birds’ resilience to the other threats they face.

Beyond National Boundaries

Our study marks the first time that tracking data for so many species has been combined with existing knowledge of oceanic plastic pollution. This represents a big leap forward in our understanding of the threat plastic pollution poses to the natural world.

A significant proportion of plastic pollution accumulates in the high seas, far beyond the waters of the country where a seabird breeds. Our findings highlight the need for international cooperation to tackle marine plastic pollution, both directly from boats and from plastic waste on land.

Research suggests that 22% of ocean litter is likely to originate from marine sources. Good waste management is therefore crucial to stop plastic waste from reaching the ocean. A key part of this will be improving compliance with the existing ban (which was adopted in 1973) on discarding any form of plastic from ships.

Protecting seabirds requires more than local solutions. We need regional and global treaties that address plastic pollution in both national waters and the high seas. Only by implementing solutions on a large scale can we safeguard the animals that inhabit our oceans.![]()

Elizabeth Pearmain, PhD Candidate in Seabird Ecology, University of Cambridge and Bethany Clark, Seabird Science Officer, BirdLife International

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.