February 27 - March 5, 2022: Issue 528

Ukrainian Poet Taras Shevchenko: Some Translations

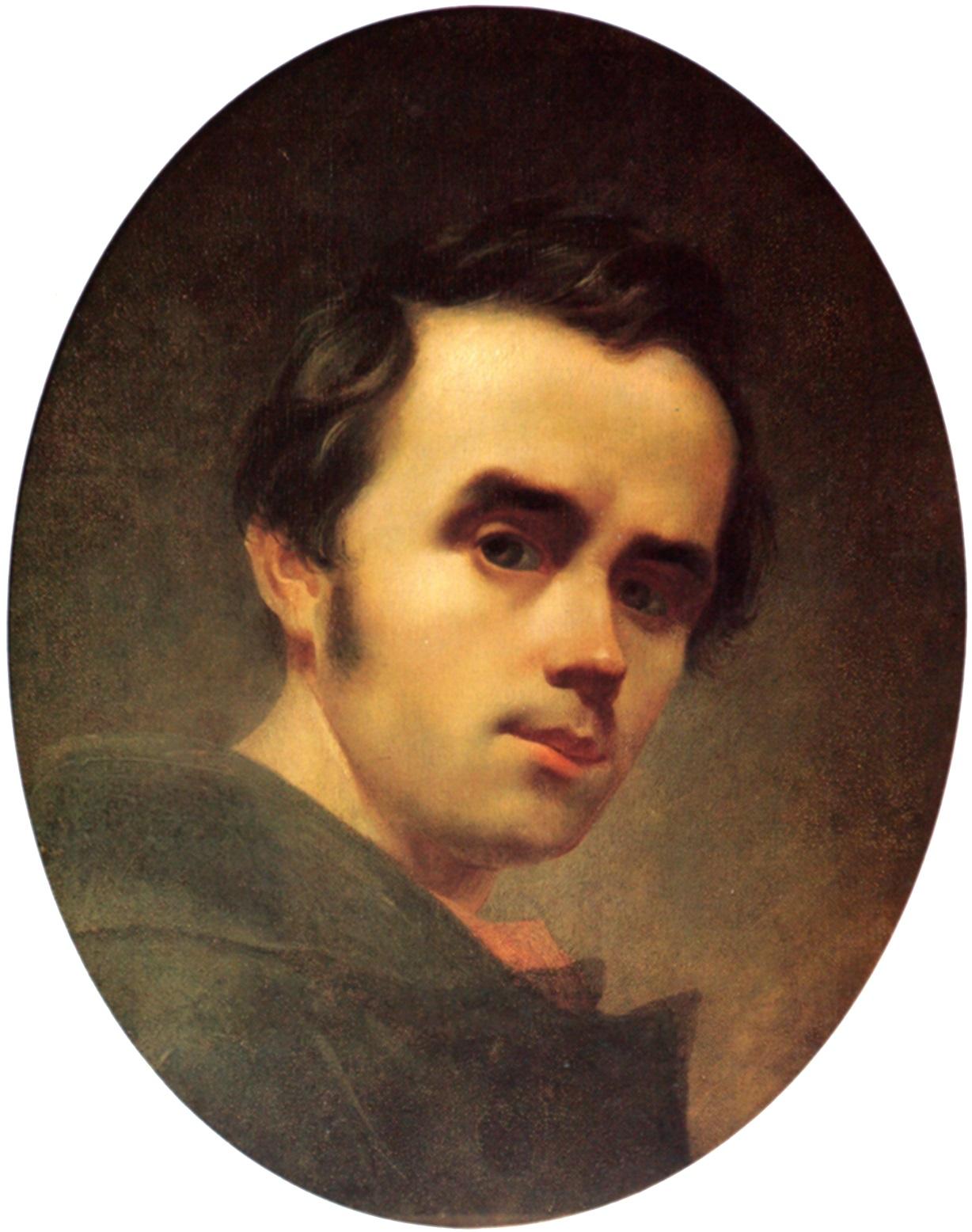

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko (Ukrainian: Тара́с Григо́рович Шевче́нко) March 9th [O.S. 25 February] 1814 – March 10th [O.S. 26 February] 1861), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (kobzars are bards in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, writer, artist, public and political figure, as well as folklorist and ethnographer.

His literary heritage is regarded to be the foundation of modern Ukrainian literature and, to a large extent, the modern Ukrainian language, though the language of his poems was different from the modern Ukrainian language. Shevchenko is also known for many masterpieces as a painter and an illustrator.

He was a fellow of the Imperial Academy of Arts. Though he had never been the member of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, in 1847 Shevchenko was politically convicted for explicitly promoting the independence of Ukraine, writing poems in the Ukrainian language, and ridiculing members of the Russian Imperial House. Contrary to the members of the society who did not understand that their activity led to the idea of the independent Ukraine, according to the secret police, he was the champion of independence.

Taras Shevchenko was born in the village of Moryntsi, Zvenyhorodka county, Kyiv Governorate, Russian Empire (today Zvenyhorodka Raion, Ukraine). He was the third child after his sister Kateryna and brother Mykyta, in family of serf peasants Hryhoriy Ivanovych Shevchenko (1782?–1825) and Kateryna Yakymivna Shevchenko (Boiko) (1782? – 6 August 1823), both of whom were owned by a landlord called Vasily Engelhardt. According to the family legends, Taras's forefathers were Cossacks who served in the Zaporozhian Host and had taken part in the Cossack uprisings of the 17th and 18th centuries. Those uprisings were brutally suppressed in Cherkasy, Poltava, Kyiv, Bratslav, and Chernihiv disrupting normal social life for many years afterwards. Most of the local population were then enslaved and reduced to poverty.

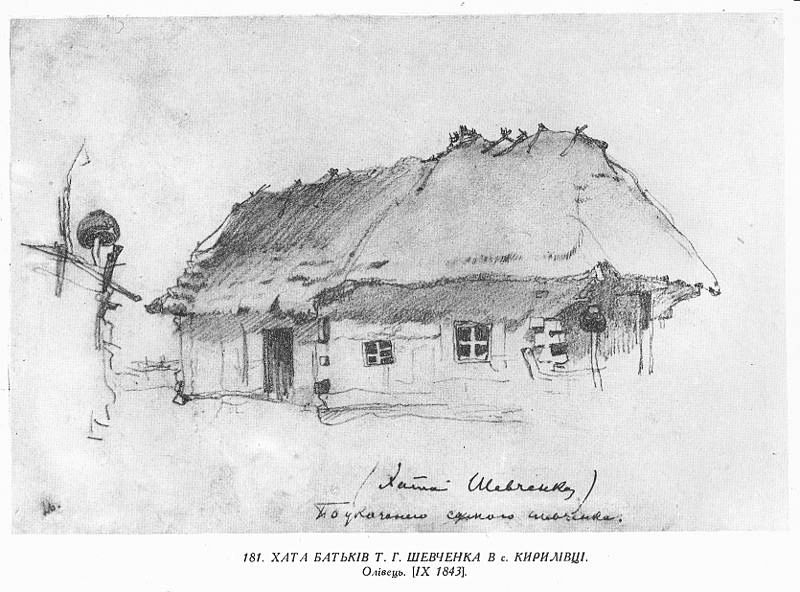

In 1816 the Shevchenko family moved back to the village of Kyrylivka (today Shevchenkove) in Zvenyhorodka county, where Taras' father, Hryhoriy Ivanovych, had been born. Taras spent his childhood years in the village. In 1824 Taras, along with his father, became a traveling merchant (chumak) and traveled to Zvenyhorodka, Uman, Yelizavetgrad (today Kropyvnytskyi). At the age of eleven Taras became an orphan when, on 2 April [O.S. 21 March] 1825, his father died as a serf in corvée. Soon his stepmother along with her children returned to Moryntsi.

Parent's hut in Kyrylivka (now village of Shevchenkove, Zvenigorodsky region, Ukraine). Taras Shevchenko, pencil, 09/1843

Taras went to work for precentor (a person who leads a congregation in its singing or prayers) Bohorsky who had just arrived from Kyiv in 1824. As an apprentice, Taras carried water, heated up a school, served the precentor, read psalms over the dead and continued to study. At that time Shevchenko became familiar with some works of Ukrainian literature. Soon, tired of Bohorsky's long term mistreatment, Shevchenko escaped in search of a painting master in the surrounding villages. For several days he worked for deacon Yefrem in Lysianka, later in other places around in the southern part of Kyiv Governorate (villages Stebliv and Tarasivka). In 1827 Shevchenko was herding community sheep near his village. He then met Oksana Kovalenko, a childhood friend, whom Shevchenko mentions in his works on multiple occasions. He dedicated the introduction of his poem "Mariana, the Nun" to her.

As a hireling for the Kyrylivka priest Hryhoriy Koshytsia, Taras was visiting Bohuslav where he drove the priest's son to school, while also taking apples and plums to market. At the same time he was driving to markets in the towns of Burty and Shpola. In 1828 Shevchenko was hired as a serving boy to a lord's court in Vilshana and gained for permission to study with an unamed local artist.

When Taras turned 14, Vasily Engelhardt died and the village of Kyrylivka and all its people became a property of his son, Pavlo Engelhardt. Shevchenko became a court servant of his new master at the Vilshana estates. On December 18th [O.S. 6 December] 1829 Pavlo Engelgardt caught Shevchenko at night painting a portrait of Cossack Matvii Platov, a hero of the Patriotic War of 1812. He boxed the ears of the boy and ordered him to be whipped in the stables with rods. During 1829–1833 Taras copied paintings of Suzdal masters.

For almost two and a half years, from fall of 1828 to start of 1831, Shevchenko stayed with his master in Vilno (Vilnius). Details of the travel or are not well known. Perhaps while there he attended lectures by painting professor Jan Rustem at the University of Vilnius. In the same city Shevchenko could also have witnessed the November Uprising of 1830. From those times Shevchenko's painting "Bust of a Woman" survived. It displays professional handling of the pencil.

After moving from Vilno to Saint Petersburg in 1831, Engelgardt took Shevchenko along with him. To benefit from the art works (since it was prestigious to have one's own "chamber artist"), Engelgardt sent Shevchenko to painter Vasiliy Shiriayev for four years of study. From that point and until 1838 Shevchenko lived in the Khrestovskyi building (today Zahorodnii prospekt, 8) where Shiriayev rented an apartment. In his free time at night, Shevchenko visited the Summer Garden where he portrayed statues.

While in Saint Petersburg he also started writing his poems, although other records state he commenced writing much earlier.

In Saint Petersburg Shevchenko met Ukrainian artist Ivan Soshenko, who introduced him to other compatriots such as Yevhen Hrebinka and Vasyl Hryhorovych, and to Russian painter Alexey Venetsianov. Through these men Shevchenko also met famous painter and professor Karl Briullov, who donated his portrait of Russian poet Vasily Zhukovsky as a lottery prize. Its proceeds were used to buy Shevchenko's freedom on May 5th, 1838.

Shevchenko was accepted as a student into the Academy of Arts in the workshop of Karl Briullov in the same year. The following year he became a resident student at the Association for the Encouragement of Artists. During annual examinations at the Imperial Academy of Arts, Shevchenko won the silver medal for landscape painting. In 1840 he again received the silver medal, this time for his first oil painting, The Beggar Boy Giving Bread to a Dog.

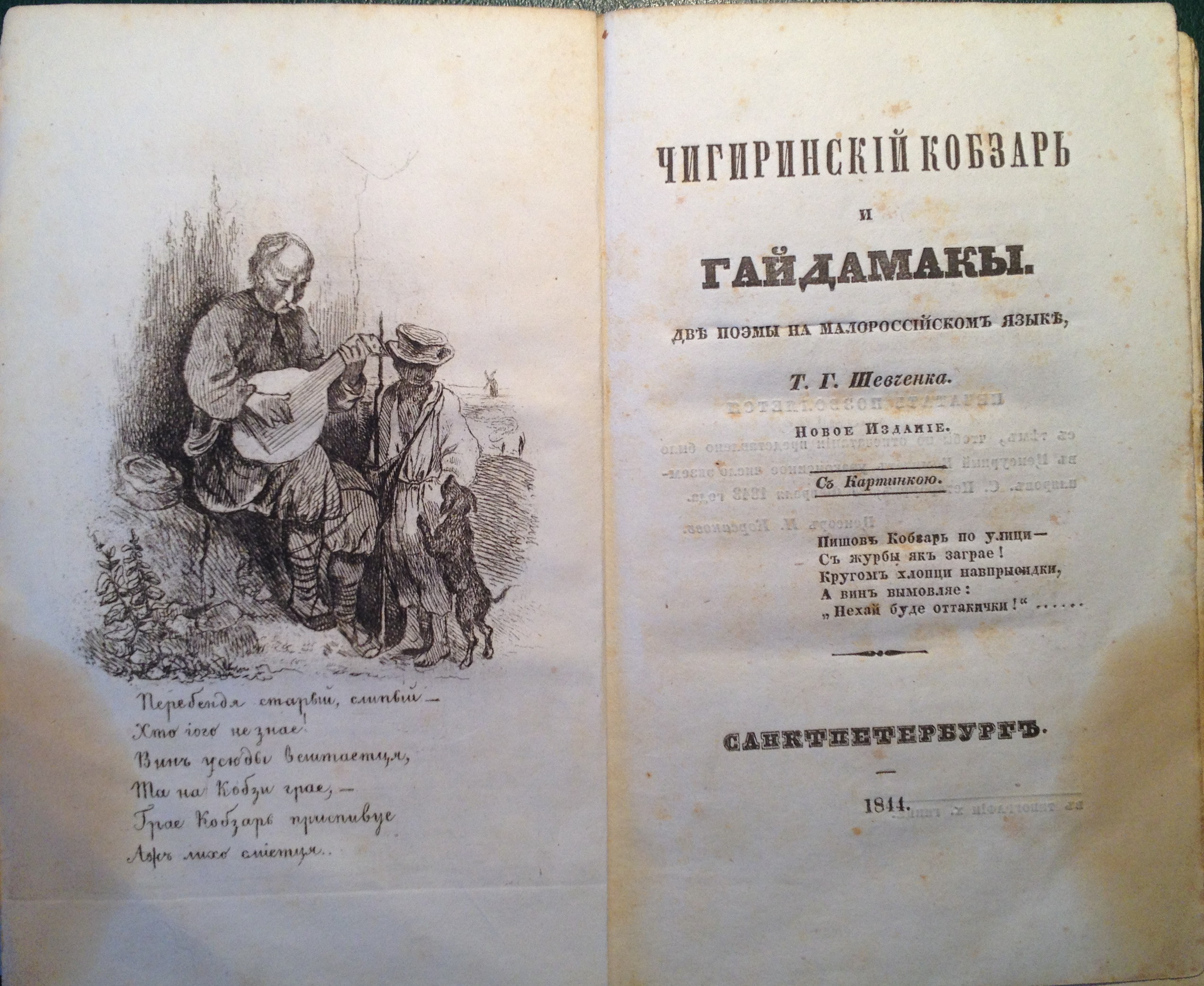

Shevchenko began writing poetry while still a serf, and in 1840 his first collection of poetry, Kobzar, was published. According to Ivan Franko, a renowned Ukrainian poet in the generation after Shevchenko, "Kobzar] was "a new world of poetry. It burst forth like a spring of clear, cold water, and sparkled with a clarity, breadth and elegance of artistic expression not previously known in Ukrainian writing".

In 1841, the epic poem Haidamaky was released. In September 1841, Shevchenko was awarded his third silver medal for The Gypsy Fortune Teller. Shevchenko also wrote plays. In 1842, he released a part of the tragedy Mykyta Haidai and in 1843 he completed the drama Nazar Stodolia.

Gypsy Fortune Teller, 1841. Winner of the 1841 Silver Medal at the Imperial Academy of Arts

While residing in Saint Petersburg, Shevchenko made three trips to Ukraine, in 1843, 1845, and 1846. The difficult conditions Ukrainians had made a profound impact on the poet-painter. Shevchenko visited his siblings, still enslaved, and other relatives. He met with prominent Ukrainian writers and intellectuals Yevhen Hrebinka, Panteleimon Kulish, and Mykhaylo Maksymovych, and was befriended by the princely Repnin family, especially Varvara.

On 22 March 1845, the Council of the Academy of Arts granted Shevchenko the title of a non-classed artist. He again travelled to Ukraine where he met with historian Nikolay Kostomarov and other members of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, a clandestine society also known as the Ukrainian-Slavic society and dedicated to the political liberalisation of the Empire and its transformation into a federation-like polity of Slavic nations. Upon the society's suppression by the authorities, Shevchenko's wrote a poem "Dream", that was confiscated from the society's members and became one of the major issues of the scandal.

Shevchenko was arrested together with the members of the society on April 5th, 1847. Tsar Nicholas I had read Shevchenko's poem, "Dream". Vissarion Belinsky wrote in his memoirs that, Nicholas I, knowing Ukrainian very well, laughed and chuckled whilst reading the section about himself, but his mood quickly turned to bitter hatred when he read about his wife. Shevchenko had mocked her frumpy appearance and facial tics, which she had developed fearing the Decembrist Uprising and its plans to kill her family. After reading this section the Tsar supposedly indignantly stated "I suppose he had reasons not to be on terms with me, but what has she done to deserve this?"

In the official report of Orlov Shevchenko was accused in using "Little-Russian language", (the archaic Russian name for the Ukrainian language) and of outrageous content instead of being grateful to be redeemed out of serfdom. In the report Orlov claimed that Shevchenko was expressing a cry over the ''alleged'' enslavement and disaster of Ukraine, glorified the Hetman Administration (Cossack Hetmanate) and Cossack liberties and "with incredible audacity poured slander and bile on persons of the Imperial House".

While under investigation, Shevchenko was imprisoned in Saint Petersburg in the casemates of the 3rd Department of Imperial Chancellery on Panteleimonovskaya Street (today Pestelia str., 9). After being convicted, he was exiled as a private to the Russian military garrison in Orenburg at Orsk, near the Ural Mountains. Tsar Nicholas I, personally confirmed his sentence, added to it, "Under the strictest surveillance, without the right to write or paint." He was subsequently sent on a forced march from Saint Petersburg to Orenburg and Orsk.

Kobzar and Haidamaky, 1844

In 1844, distressed by the condition of Ukrainian regions in the Russian Empire, Shevchenko decided to capture some of his homeland's historical ruins and cultural monuments in an album of etchings, which he called Picturesque Ukraine. Only the first six etchings were printed because of the lack of means to continue. An album of watercolors from historical places and pencil drawings was done in 1845.

In 1848, he was assigned to undertake the first Russian naval expedition of the Aral Sea on the ship "Konstantin", under the command of Lieutenant Butakov. Although officially a common private, Shevchenko was effectively treated as an equal by the other members of the expedition. He was tasked to sketch various landscapes around the coast of the Aral Sea. After an 18-month voyage (1848–49) Shevchenko returned with his album of drawings and paintings to Orenburg. Most of those drawings were created for a detailed account about the expedition. Nevertheless, Shevchenko created many unique works of art about the Aral Sea nature and Kazakhstan people at a time when a Russian invasion of Central Asia had begun in the middle of the nineteenth century.

He was then sent to one of the worst penal settlements, the remote fortress of Novopetrovsk at Mangyshlak Peninsula, where he spent seven terrible years. In 1851, at the suggestion of fellow serviceman Bronisław Zaleski, lieutenant colonel Mayevsky assigned him to the Mangyshlak (Karatau) geological expedition. In 1857 Shevchenko finally returned from exile after receiving amnesty from a new emperor, though he was not permitted to return to St. Petersburg and was forced to stay in Nizhniy Novgorod.

In May 1859, Shevchenko received permission to return to Ukraine. He intended to buy a plot of land close to the village Pekari. In July, he was again arrested on a charge of blasphemy, but then released and ordered to return to St. Petersburg.

Taras Shevchenko spent the last years of his life working on new poetry, paintings, and engravings, as well as editing his older works. After difficult years in exile, however, his illnesses took their toll upon him. Shevchenko died in Saint Petersburg on March 10th, 1861.

He was first buried at the Smolensk Cemetery in Saint Petersburg. However, fulfilling Shevchenko's wish, expressed in his poem "My Testament" ("Zapovit"), to be buried in Ukraine, his friends arranged the transfer of his remains by train to Moscow and then by horse-drawn wagon to his homeland. Shevchenko was re-buried on 8 May on the Chernecha hora (Monk's Hill; today Taras Hill) near the Dnipro River and Kaniv. A tall mound was erected over his grave, now a memorial part of the Kaniv Museum-Preserve.

Dogged by terrible misfortune in love and life, the poet died seven days before the 1861 emancipation of serfs was announced. His works and life are revered by Ukrainians throughout the world and his impact on Ukrainian literature is immense.

Taras Shevchenko's writings formed the foundation for the modern Ukrainian literature to a degree that he is also considered the founder of the modern written Ukrainian language (although Ivan Kotlyarevsky pioneered the literary work in what was is close to the modern Ukrainian in the end of the 18th century).

Shevchenko's poetry contributed greatly to the growth of Ukrainian national consciousness, and his influence on various facets of Ukrainian intellectual, literary, and national life is still felt to this day. Influenced by Romanticism, Shevchenko managed to find his own manner of poetic expression that encompassed themes and ideas germane to Ukraine and his personal vision of its past and future.

In view of his literary importance, the impact of his artistic work is often missed, although his contemporaries valued his artistic work no less, or perhaps even more, than his literary work. A great number of his pictures, drawings and etchings preserved to this day testify to his unique artistic talent. He also experimented with photography and it is little known that Shevchenko may be considered to have pioneered the art of etching (in 1860 he was awarded the title of Academician in the Imperial Academy of Arts specifically for his achievements in etching.)

His influence on Ukrainian culture has been so immense, that even during Soviet times, the official position was to downplay the strong Ukrainian nationalism expressed in his poetry, suppressing any mention of it, and to put an emphasis on the social and anti-Tsarist aspects of his legacy, especially the Class struggle within the Russian Empire. Shevchenko, who himself was born a serf and suffered tremendously for his political views in opposition to the established order of the Empire, was presented in the Soviet times as an internationalist who stood up in general for the plight of the poor classes exploited by the reactionary political regime rather than the vocal proponent of the Ukrainian national idea he actually was.

This view is significantly revised in modern independent Ukraine, where he is now viewed as almost an iconic figure with unmatched significance for the Ukrainian nation, a view that has been mostly shared all along by the Ukrainian diaspora that has always revered Shevchenko.

He inspired many of the protestors during the Euromaidan.

On November 21st 2013, Ukrainians took to the streets in peaceful protest after then-president Viktor Yanukovych chose not to sign an agreement that would have integrated the country more closely with the European Union, instead choosing closer ties to Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union. The brutal government crackdown that followed these initial protests galvanised Maidan supporters and encouraged more to join. This momentum, further propelled by killings on February 20 and 21, led to the removal of ex-president Yanukovych from power.

On February 27 and 28, pro-Russian gunmen seized key buildings in Crimea and took control of the Crimean Peninsula. On March 16, in a disputed referendum that Ukraine and the West deemed illegal, a section of the Crimean population chose to secede from Ukraine. On March 18, Russian and Crimean leaders signed a deal in Moscow to join the region to Russia.

Following Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea, many people from the Ukrainian community and Crimean Tatar minority community, fearing repression, fled the region. Those who stayed behind have faced persecution.

In April 2014, pro-Russian separatist activity spread to other eastern Ukrainian cities like Donetsk and Lugansk in the Donbass region. This escalated into an armed conflict between the Ukrainian government and the separatist forces of the self-declared Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics, whose demands range from self-rule to union with Russia. The conflict has caused displacement, civilian loss of life, destruction of infrastructure, and a humanitarian crisis. The UN estimates that between mid-April 2014 and January 2015, at least 5,244 people were killed and 11,862 wounded in the conflict. People are still being killed in the regions. People have fled these regions ever since and the UNHCR estimates there are now 1.5 million displaced people within the Ukraine.

The term "Euromaidan" was initially used as a hashtag of Twitter. A Twitter account named Euromaidan was created on the first day of the protests. It soon became popular in the international media. The name is composed of two parts: "Euro" is short for Europe and "maidan" refers to Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), the large square in the downtown of Kyiv, where the initial protests took place. The word "Maidan" is an Arabic word meaning "square" or "open space" adopted by Ukrainians from the Ottoman Empire. During the protests, the word "Maidan" acquired the meaning of the public practice of political protest.

Below run some of Taras' poems, as translated by various scholars ever since.

Biography from:

- "National Museum of Taras Shevchenko. Virtual Archives. Metric book".

- "Shevchenko, Taras". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com.

Shevchenko's "My Testament", (Zapovit, 1845), has been translated into more than 150 languages and set to music in the 1870s by H. Hladky.

My Testament

When I die, remember, lay me

Lowly in the silent tomb,

Where the prairie stretches free,

Sweet Ukraine, my cherished home.

There, ’mid meadows’ grassy sward,

Dnieper's waters pouring

May be seen and may be heard,

Mighty in their roaring.

When from Ukraine waters bear

Rolling to the sea so far

Foeman’s blood, no longer there

Stay I where my ashes are.

Grass and hills I’ll leave and fly.

Unto throne of God I’ll go.

There in heaven to pray on high,

But, till then, no God I know.

Standing then about my grave,

Make ye haste, your fetters tear!

Sprinkled with the foeman’s blood

Then shall rise your freedom fair.

Then shall spring a kinship great,

This a family new and free.

Sometimes in your glorious state.

Gently, kindly, speak of me.

Source of English translation of the poem: "The Kobzar of the Ukraine". Being select Poems of Taras Shevchenko. Done into English Verse with Biographical Fragments by Alexander Jardine Hunter, p. 144 - 145. Translated by Alexander Jardine Hunter

To N. N.

As the sun sets and hills grow dark,

as the birdsong ends and fields fall silent,

as the people laugh and take their rest,

I watch.

My heart hurries

to the twilit gardens of Ukraine.

And I hurry.

O, how I hurry with my thoughts,

as my heart yearns for rest.

As the fields grow dark,

as the groves grow dark,

as the hills grow dark,

I see a star.

And I weep.

Hey, you star! Have you reached Ukraine?

Do dark eyes scour the blue sky for you?

Or don’t they care?

May they sleep if they don’t.

May they know nothing of my fate.

1847

Translated by Alexander J. Motyl

[Untitled]

If only I could see

my fields and steppes again.

Won’t the good Lord let me,

in my old age,

be free?

I’d go to Ukraine,

I’d go back home.

There they’d greet me—

glad to see the old man.

There I’d rest,

I’d pray to God,

There I’d—but why go on?

There will be nothing.

How am I to live in slavery

with no hope?

Do tell me,

please,

lest I go crazy.

1848

Translated by Alexander J. Motyl

In the Casemate

III

It’s all the same if

I settle in Ukraine or not.

If someone finds or forgets

me in the desert snow

in some other country—

doesn’t matter to me.

In slavery I grew

around strangers

and your folks

un-cried for. In slavery

you cry, die. Everything taken

up with you, don’t leave

light footprints

in this radiant country—

on ground that is not yours.

And the dad won’t reminisce

with the son. Won’t

tell the son, pray, pray,

for Ukraine was bludgeoned

down at some point.

I don’t care if the son prays.

But it’s not the same to me,

as vicious people lull

Ukraine to sleep slyly

and in a fire, kidnapped,

she’s woken up on fire . . . Ah,

it’s not all the same to me.

April 17–May 19, 1847, St. Petersburg, Russia

Translated from the Ukrainian by Daniel Moysaenko

My Friendly Epistle

To the Dead, the Living, and to Those Yet Unborn, My Countrymen all Who Live in Ukraine and Outside Ukraine;

If a man say, I Love God, and hate his brother, he is a liar, - 1 John iv. 20

Day dawns, then comes the twilight grey,

The limit of the live-long day;

For weary people sleep seems best

And all God’s creatures go to rest.

I, only, grieve like one accursed,

Through all the hours both last and first,

Sad at the crossroads, day and night,

With no one there to see my plight;

No one can see me, no one knows me;

All men are deaf, no ears disclose me;

Men stand and trade their mutual chains

And barter truth for filthy gains,

Committing shame against the Lord

By harnessing for black reward

People in yokes and sowing evil

In fields commissioned by the Devil…

And what will sprout? You soon will see

What kind of harvest there will be!

Come to your senses, ruthless ones,

O stupid children, Folly’s sons!

And bring that peaceful paradise,

Your own Ukraine, before your eyes;

Then let your heart, in love sincere,

Embrace her mighty ruin here!

Break then your chains, in love unite,

Nor seek in foreign lands the sight

Of things not even found above,

Still less in lands that strangers love…

Then in your own house you will see

True justice, strength, and liberty!

Then in your own house you will see

True justice, strength, and liberty!

There is no other such Ukraine,

No other Dnieper on the plain;

And yet you throng to foreign lands

To seek the Highest Good that stands.—

True Liberty, that sacred Good

In fair fraternal Brotherhood! …

And you have found it as you roam!

From foreign fields you bring it home,

A heap of words that sound most great

And naught else … You vociferate

That God created you to be

His Justice’s epitome,

Yet you still bend your backs today

To aliens, and are prompt to flay

The hide off lowly peasant brothers;

Then, seeking “Truth” beyond all others,

You scurry off to German strands

And to the lore of other lands.

If you could in your baggage bind

The misery you leave behind,

Or carry off beyond appeal

Those gains our forbears had to steal,

There would be left, to mourn our ills,

Lone Dnieper with its holy hills. For this great boon my spirits yearn.—

That from abroad you’d not return,

That there you’d die, where you did learn!

For children then in our Ukraine

No more would weep in futile pain,

Nor would your motherland lament

Or God declare you insolent;

The sun would not a task perform

Your stinking carcasses to warm

Upon a land, pure, free, and vast

And people would not know at last

What birds you are, how greedy, dread,

And at you shake a hopeless head…

Come to your senses! Human be,

Or you will rue it bitterly:

The time is near when on our plains

A shackled folk will burst its chains.

The Day of Judgment is at hand!

Dnieper will speak across the land;

Hundreds of streams will surge in flood

To bear along your children’s blood

To the blue sea,. . . Nor man nor whelp

Will offer you the slightest help:

Brother will turn from brother wild,

The mother will forsake her child;

Thick clouds of smoke at noonday bright

Will hide the sunshine from your sight;

And your own sons, for all your crime,

Will curse you to the end of time.

Make yourselves clean! God’s image clear

In man should not be sullied here!

Don’t breed your children up in scorn

To think that they were proudly born

To lord it over humble folk—

The peasant’s untaught eye will poke

And peer into their very souls

Unsnared by specious aureoles.

Soon will the wretched creatures find

Your hides are of a kindred kind,—

Then will the meek in judgment sit,

All your fine wisdom to outwit.

II

If you would train yourselves alone,

You’d have some wisdom of your own;

But you must prattle from the sky:

“We are not we, and I not I!

All have I seen, I’m now all wise,

There is no hell, no paradise,

Not even God; but I exist

And this smart German atheist

And nothing else . .”—”Brother, go slow!

Who are you then?”—”I do not know—

We’ll let the Germans speak to that,

For they have all the answers pat!”

In such a fashion then you train

Yourselves in foreigners’ domain!

A German pundit says, “You’re Mongols.”

And you reply: “Of course, we’re Mongols,

The naked seed upon this plain

Sowed by the golden Tamerlane!”

Or if some German says: “You’re Slavs,”

You’ll echo back: “Of course, we’re Slavs,

The ugly, graceless progeny

Of our great ancestors, you see!”

Perhaps you even read old Kollar,

Enthusiastic for that scholar,

And Hanka too, and Safatik

And strive with zeal most politic

To rank among the Slavophils

And demonstrate linguistic skills

In all Slav tongues except your own.

“Some day we’ll have the time,” you groan,

“To speak our native language well

If some smart foreigner will tell

Its principles; if he’ll relate

Our history as well, then straight

We’ll study at a furious rate!”

How you have sought with ardent suction

To soak up foreigners’ instruction!

You talk in such a mongrel speech

That even Germans, wise to teach,

Gape at it as a senseless joke —

Still more, of course, the common folk.

And such a noise! What row you raise:

“What harmony beyond all praise!

Our tongue is music from the skies!

Our history? Behold it rise,

A freeborn people’s lofty poem…

Rome seems to this a paltry proem!

Horatius, Brutus, whom they will,

Let Romans praise! We’ve greater still,

More famous, ne’er forgotten too…

It was with us that Freedom grew,

Lay stretched in Dnieper’s mighty bed

And on our mountains couched her head

And made our steppe her counterpane!”

No, you are wrong! In this Ukraine

Our history was bathed in blood

And slept on corpses in the mud,

On Cossack corpses, no more free

But here despoiled of liberty! …

Look well into our history’s store

And read it closely, o’er and o’er;

That glorious tale you may have heard,—

But take it slowly, word by word;

No punctuation mark omit,

For even commas lend their bit;

Examine everything you see;

Then ask yourselves: Now, who are we?

Whose children? Of what fathers born?

By whom enslaved in utter scorn?

Then only will you understand

The Brutuses of this your land

Slaves, grovellers of Muscovy

And Warsaw’s refuse, such will be

The illustrious hetmans you applaud!

And have you something then to laud,

Sons of Ukraine, where misery chokes?

Perhaps that you walk well in yokes,

More nobly than your fathers walked?

Don’t boast that you have bravely stalked:

Your hides are being tanned, though callow,

But they were often boiled for tallow!

Perhaps you base your boast on this:

The Cossack Brotherhood with bliss

Defended and preserved our faith?

That in Sinope’s flaming wraith

And Trebizond’s, they cooked their cake?

They did, but you’ve the belly-ache;

For in the Sitch the German sage

Now plants potatoes; without rage,

You buy his produce with your wealth

And eat it gladly for your health,

And glorify the Cossacks’ fame.

But whose rich blood, O men of shame,

Has saturated all the soil

That yields potatoes which you boil?

You do not care; you merely know

It’s good to make the garden grow!

And yet you boast that with our frown

We once sent Poland toppling down!

You are quite right: for Poland fell;

And in the wreck crushed us as well.

And that is how our sires, now dead,

For Muscovy and Warsaw bled,

And left their sons, as legacy,

Their shackles and their infamy!

III

Thus, in her struggle, our Ukraine

Reached the last climax of pure pain:

Worse than the Poles, or any other,

The children crucify their mother;

As it were beer, they tap with zest

The pure blood from her sacred breast,—

They would enlighten, they surmise,

Their ancient mother’s rheumy eyes

With clear, contemporary light,

And lead her, in her dumb despite,

A blind wretch, out upon the stage

Into the spirit of our age.

Good! Show her! Lead her in the way!

Let the old mother learn today

How to take care, as Wisdom runs,

Of you, her new enlightened sons!

Show her! But do not raise a ruction

About the price of that instruction!

Well will your mother pay you back:

The wall-eyed cataract will crack

Upon your own dull, greedy eyes

And you will see her glory rise,

The living glory of your sires,

To shame your fathers’ black desires!

Gain knowledge, brothers! Think and read,

And to your neighbours’ gifts pay heed, —

Yet do not thus neglect your own:

For he who is forgetful shown

Of his own mother, graceless elf,

Is punished by our God Himself.

Strangers will turn from such as he

And grudge him hospitality —

Nay, his own children grow estranged;

Though one so evil may have ranged

The whole wide earth, he shall not find

A home to give him peace of mind.

Sadly I weep when I recall

The unforgotten deeds of all

Our ancestors: their toilsome deeds!

Could I forget their pangs and needs,

I, as my price, would than suppress

Half of my own life’s happiness…

Such is our glory, sad and plain,

The glory of our own Ukraine!

I would advise you so to read

That you may see, in very deed,

No dream but all the wrongs of old

That burial mounds might here unfold

Before your eyes in martyred hosts,

That you might ask those grisly ghosts:

Who were the tortured ones, in fact,

And why, and when, were they so racked?

Then O my brothers, as a start,

Come, clasp your brothers to your heart, —

So let your mother smile with joy

And dry her tears without annoy.

Blest be your children in these lands

By touch of your toil-hardened hands,

And, duly washed, kissed let them be

With lips that speak of liberty!

Then all the shame of days of old,

Forgotten, shall no more be told;

Then shall our day of hope arrive,

Ukrainian glory shall revive,

No twilight but the dawn shall render

And break forth into novel splendour….

Brother, embrace! Your hopes possess,

I beg you in all eagerness!

Taras Shevchenko, Viunishcha, December 14, 1845

Translated by C. H. Andrusyshen & W. Kirkconnell