April 29 - May 5, 2012: Issue 56

A Cruel Sea By Gordon Wellings

Broken Bay  This incident commenced at Broken Bay, one of the most popular sections of the Australian coastline. Broken Bay is located approximately 16 nautical miles (30 kilometres) north of Sydney Heads, and is the convolution of Brisbane Waters, The Pittwater and the Hawkesbury River. The name does not tell a lie; the Bay is difficult to describe accurately in terms of its geographic boundaries. The inner boundary is best described as thus: If the point of a compass is on Lion Island and an arc is prescribed in a clockwise direction, you would best begin at Barrenjoey Headland marking the southern entrance to the Bay. From there you traverse the entrance to The Pittwater, in a westerly direction to West Head. Continue North West and cross the Hawkesbury River to Middle Head. Then swing generally north behind Lion Island and follow the beaches of Umina and Ocean Beach and eventually cross the narrow, navigable entrance to Brisbane Waters to Box Head , which is the northern boundary to the bay.

This incident commenced at Broken Bay, one of the most popular sections of the Australian coastline. Broken Bay is located approximately 16 nautical miles (30 kilometres) north of Sydney Heads, and is the convolution of Brisbane Waters, The Pittwater and the Hawkesbury River. The name does not tell a lie; the Bay is difficult to describe accurately in terms of its geographic boundaries. The inner boundary is best described as thus: If the point of a compass is on Lion Island and an arc is prescribed in a clockwise direction, you would best begin at Barrenjoey Headland marking the southern entrance to the Bay. From there you traverse the entrance to The Pittwater, in a westerly direction to West Head. Continue North West and cross the Hawkesbury River to Middle Head. Then swing generally north behind Lion Island and follow the beaches of Umina and Ocean Beach and eventually cross the narrow, navigable entrance to Brisbane Waters to Box Head , which is the northern boundary to the bay.

This boundary is approximately 2.7 nautical miles across from Barrenjoey to Box Head.

To mariners, Broken Bay also has an outer boundary, stretching from Bangally Head off Avalon, north to Cape Three Points. This stretch of coast includes Killcare Beach and Maitland Bay.

Norah Head

From Cape Three Points the coast swings to the north towards Newcastle. It is 22.5 nautical miles (41 kilometres) to Norah Head from Barrenjoey Headland. Norah Head has a lighthouse with a white light that flashes once, and is visible for 30 nautical miles (55 kilometres). The light is approximately the midpoint from Broken Bay to Newcastle.

Traffic

Many thousands of vessels, predominately pleasure craft, enter and leave Broken Bay each year. Some proceed to sea and back to their berths for day trips while many others head out for longer, overnight trips to Lake Macquarie Port Stephens and Queensland.

This large volume of traffic has some interest to this story, because many should have seen the stricken Votan during its first morning off the coast.

The Ill-fated Votan

The Votan is a 10m, steel-hulled ketch with an auxiliary four- cylinder petrol engine. The engine would later be described to police by one of the owners as being in fair mechanical condition. The vessel was permanently moored at Halverson 's Boatshed, Bobbin Head. The Votan is a Canadian vessel finding its way into Australian waters after being sold a number of times.

It was purchased by Adrian Wedgwood and Ray Kruger off a family that had purchased it from the Australian Government after it had been impounded as the result of a serious crime. At the time of purchase, Wedgwood told the family that he intended on sailing it back to England with friends. An interesting challenge considering he had no sailing experience.

It was apparent that very little safety equipment was kept on board the ketch. There was no radio and no V Sheet; or if there was a 'V' Sheet, the owners and crew did not know where it was or how to use it. There were very few flares. In later statements, reference was made to firing two flares, however it is believed these may have only been hand-held flares and none of the parachute variety.

Voyage to Death

On Friday 7 June 1974 the two owners Solicitor Adrian Wedgwood (the son of Lord Piers Wedgwood, owner of the famous Wedgwood crockery and dining settings company), aged 26, and Labourer Raymond Kruger, also about 26, loaded a dog of unknown breed four passengers including a female student. Hong, Ja Jin: labourer Brian. Kennedy: hospital attendant Ian Wilkins and methods engineer, Derek James Catterall - all in their 20s - onto the Votan for a weekend of sailing practice and leisure No-one on board had any sailing experience Adrian Wedgwood and Ray Kruger had only purchased the ketch in December 1973 and for practice had been taking the ketch for weekend day trips preparatory to travelling to Sydney Harbour where they intended to permanently moor it.

Once underway that afternoon, they proceeded under power to Refuge Bay in Cowan Creek, where they moored the vessel over night. It should be noted at this time that the auxiliary engine gave no indication of unreliability.

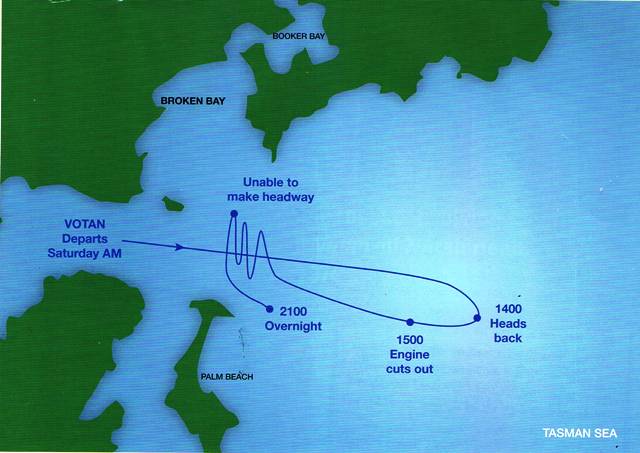

On the morning of Saturday 8 June, 1974, they sailed out of Broken Bay and out to sea. They described the sea at the time as "slightly choppy" with moderate winds of 10-15 knots.

Ray Kruger stated that on the Friday, when they read the weekend forecast, there was no indication of bad weather. By about 1230 hours three of the crew were sea sick. Kruger later told police that at some time between 1230 to 1300 hours he discussed with Wedgwood about returning to Broken Bay, so they would be there by 1630 hours. About 1400 hours, he later told police, he was below deck and overheard some talk between Adrian Wedgwood and those on deck that they had altered course and were heading back to Broken Bay.

Around 1500 hours, Adrian Wedgwood went below and told Ray Kruger that due to the wind, they were making very little headway. After some discussion, Wedgwood and Kruger decided to drop the sails and rely on the auxiliary engine. They managed to start the engine however it ran for only a short time before it cut out. Eventually they were able get it running and made reasonable progress for another 40 minutes. They managed to get inside the outer boundary of Broken Bay just off Lion Island, when the engine cut out again.

In an effort to keep moving they put up the sails and tacked south towards Sydney, and then back towards Lion Island By this time the seas had become choppier, and darkness was fast approaching. For some reason they decided it was more prudent to head out to sea for the night, rather than undertaking the numerous tacks and jibes that it would have taken for them to get back inside Broken Bay.

By 2100 hours (9pm) they had been pushed south of Lion Island, and were close to Barrenjoey Head and were in complete darkness. The wind had increased in velocity and the sea had risen. Around this time the crew let off a red flare as they were becoming increasingly concerned about their ability to manage the rising seas and increasing winds. It was also decided that Adrian Wedgwood and Ray Kruger would take it in turns to sit at the helm during the night. Adrian Wedgwood took the first shift, remaining at the helm until about 0330 hours when he was relieved by Ray Kruger.

Fatal Error

As the sun rose on Sunday 9 June, 1974, the damage inflicted on the Votan during the night became apparent The main sail was broken the mizzen had been lowered and the only sail up was the jib The seas had risen 30 to 40 feet and were considered rough According to Ray Kruger, the wind had increased between 30 and 40 knots but unfortunately, it was in fact closer to 60 knots or 100kph During the first hours of daylight they again tried to tack into Broken Bay, but were again unsuccessful. About 1100 hours they gave Broken Bay away, and because their charts indicated that there was safe anchorage at Terrigal Haven on the Central Coast, they decided to run with the sea to Terrigal. In making this decision, Wedgewood and Kruger had totally ignored the atrocious weather conditions and monstrous seas, and were obviously ignorant of the fact that the area is littered with Bomboras and reefs, which are extremely dangerous in heavy weather. Their decision was about to turn their weekend joy-ride into a lethal nightmare.

The Votan sailed north, but for some reason missed Terrigal Haven and ended up at Tuggerah. About 1400 hours, Adrian Wedgwood made several attempts to tack into Tuggerah without success. Being the only person on deck, he possibly felt out of control and out of depth, and ignited a hand-held red flare Brian Kennedy was looking out through a porthole window when without warning the Votan capsized doing a complete 360 degree roll then hastily righting itself.

Those below deck immediately went topside and as Brian Wilkins would later tell police he saw Adrian Wedgwood floating in the sea about 100 metres from the Votan with his head just above the water. He only saw him for about four to five seconds then he disappeared behind some big waves and did not see him again.

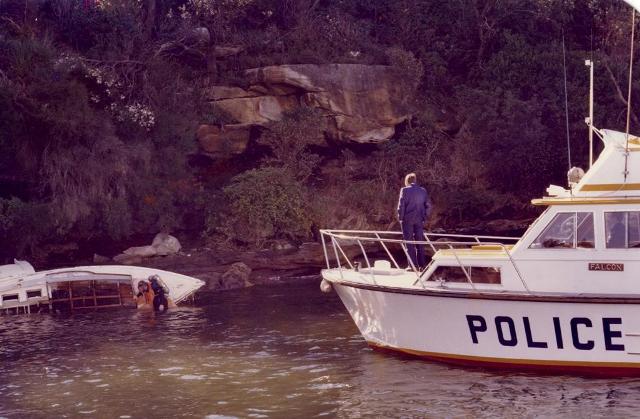

As a result of the roll-over, all of the Votan's masts were broken and hanging over the side. The Votan was stricken; there was considerable water in the bilge, it was low in the water and it was adrift. In an effort to lighten the vessel and keep it afloat, the passengers started to throw everything overboard that was not tied down.

To try and stop the Votan from drifting into the Tuggerah Bomboras, Derrick Catterall dropped the anchor. However, all the anchor did was hold the ketch into the face of the prevailing weather and allow the waves to continually crash over the bow. Faced with this potentially fatal situation he cut the anchor line, again setting the Votan adrift. As luck would have it, the prevailing sea and wind took the ketch further up the coast towards Norah Head and away from the bomboras. About 45 minutes later; and after seeing light aircraft fly close overhead, Derrick Catterall discharged another flare. He stated that at that time the "seas were mountainous."

The Falcon

The Police launch Falcon was a 32-foot (10-metre), double-diagonal, triple-skinned, timber-hulled vessel built by the well-known and respected Sydney boat builder, Peter Bracken. The vessel had a trunk cabin with twin bunks, a wheelhouse with radio and chart table facilities and spare seating. The main deck was fitted with a tow post and two reels of towing rope. The Falcon was powered by twin V8 Mercruiser petrol engines (the inboard version of the famous Mercury outboard motor).

All this made the Falcon an extremely strong and very good sea-going vessel. It was also fitted with police and marine radio communications suitable for Search and Rescue (SAR) and police operational requirements (there was no GPS or satellite navigation in those days. Radio Direction Finders - RDF - had been fitted to some police launches, but not the Falcon. The NSWPF flagship, NTW Allan, was the only vessel with radar).

The Rescue

On the morning of Sunday 9 June, 1974, the Commander of the Water Police contingent at Mona Vale and 15-year Water Police veteran, Buster Brown, had been rostered alone at the police berth at Church Point in Pittwater to perform maintenance on the Falcon and to attend to public enquiries. His full name was Roper Lars Scott Brown but he had only ever been known (even by long-term friends) as Buster. At 0830 hours, both Brian Friend and I were recalled to duty by Buster to assist with the increased volume of 'search and recovery work', and to take reports of damage due to the strong winds the previous night.

Buster not only had years of experience operating police launches. but for most of his life had been an active member of South Curl Curl Surf Life Saving Club (SLSC). The skills practised in both his professional and volunteer life made him one of the most experienced police officers in the state in relation to surf and ocean rescue.

Brian Friend was a Constable 1st Class and being an active member of the Avalon Beach SLSC was very experienced in surf and sea rescue He was also a mechanical engineer, which was a terrific skill to have when working in and around boats. I was a Senior Constable and acted as the third crew member; I had been transferred to Mona Vale in 1967 as a general duties police officer. Like most other members of the station, I was required to be licensed and proficient in the operation of the Falcon. This presented a unique challenge for me as I was born and raised in the Riverina of NSW and had no prior boating experience. I actually learnt to swim in irrigation channels!

As Buster predicted, we were called out a number of times that day to jobs in and around The Pittwater. Because we were so busy in The Pittwater, we didn't get a chance to venture around the 'Joey' (Barrenjoey Headland). Either way, we didn't think anyone would be out in such terrible conditions. As it was the weekend, both the RVCP and the Australian Volunteer Coast Guard (AVCGA) were on-duty at their bases in the Hawkesbury, and were monitoring marine frequencies.

About 1430 hours, we were cleaning up preparatory to ending the shift when Buster received a message, that a ketch had overturned not far off The Entrance, between Terrigal and Norah Head on the NSW Central Coast, and that a power Surf Rescue Boat from The Entrance Surf Life Saving Club was responding.

Fortunately, we had just refuelled the Falcon and were able to mobilise quickly. We made our way down The Pittwater to the Joey', and into Broken Bay. We knew the sea had been building all day, but were astounded at the size of the swell that was running south, south east. Although we were apprehensive about the dangers of a rescue in such bad conditions, our sense of duty far outweighed any concerns we had, plus we felt obliged to back up the power surf boat. So as the Falcon's twin 350ci V8 engines powered out through the heads, we notified police on the Central Coast and the RVCP that we should be off Tuggerah at about 1700 hours.

We had only been underway about 20 minutes when Buster told us to get out the life jackets and put them on. This was the second time that I was aware that Buster had ever worn life jackets on board a police launch the first time was some time ago when he was in terrible sea conditions on the NWPF flag ship the Nemesis. For me in the seven years I had been working part-time in the Water Police this was by far the largest sea I had ever been out in. To make matters worse the starboard motor started cutting out under idle, which was basically every time we went down the back of a large wave. The Falcon had been booked to be taken to Sydney Water Police on the Saturday for repairs to an engine, but we put it off due to the expected workload of this weekend.

As we rounded Cape Three Points and headed north with the sea and wind behind us, we learnt that the power surf boat had got beyond the break on the beach but had become disoriented and lost in broad daylight. The depth of the troughs and the short periods that they were on the wave crest meant they could not get their bearing. The surf boat could only enter the sea and return to safety via the channel leading into The Entrance. Conditions were far too rough and dangerous they couldn't return to their home base via their return route. A helicopter had been called earlier in the afternoon, but because the only available helicopter had a single engine, it was considered too dangerous to operate over the sea in the current conditions. The military had twin-engine-powered helicopters, but could not reach the operation area before night, which also put them out of consideration.

We were basically on our own and had gone very quickly from backing up to a surf boat to being the main rescuers with absolutely no backup or assistance. We were advised that the ketch was very close to entering the broken surf of the Bombora just off Norah Head which we knew would have meant its destruction and the death of all those on it. During the hours that it took to power up the coast, Buster displayed the most skilful piece of driving that I have ever seen, as he kept the Falcon on a straight course. Looking astern from inside our wheelhouse we could not see the tops of the waves. They were so high and as they passed beneath us, we looked down into a trough at least twice the length of the Falcon.

When we were about five nautical miles seaward of Norah Head, we turned to the port (left) and headed west towards the shore. Buster instructed Brian to put on a harness and go up to the flying bridge (an elevated position on the vessel that is fitted with a seat so that a vantage point is able to be established) to keep a look out, and try and spot the Votan. It was about 1700 hours, the sun was low in the western sky and was shining directly into our eyes. We could barely see anything in front of us. I contacted local police who sent a police officer to the Norah Head Lighthouse with a portable radio to guide us in.

We were about three hundred metres off Norah Head when we first saw the Votan. It was difficult to see as its masts were hanging over the side, and its hull was quite a dark colour. The ketch was just outside the breakers pounding the Bombora off Norah Head and drifting slowly towards certain disaster. I was directed by Buster to don a safety harness.

As Buster turned the Falcon into the sea and we edged slowly astern Brian climbed over the stern and onto the marlin board and whilst I held on to his belt he tossed a tow line to the Votan. One of its crew caught it and secured it to the deck. We picked up the slack and started towing the Votan. This gave us a few seconds to gather our composure and time to discard our safety harnesses as they were severely hampering our movement and risking the success of the rescue operation. It was then that I saw off our bow the largest wave I have ever seen. I yelled to Brian to hang on and get back towards the tow post. The Falcon was 32 feet in length and we travelled from the trough of that wave up its face (at least three boat lengths) before crashing through the top few feet. I knew that the ketch would not make it. The tow line sliced down through the wave behind us and then parted and broke.

As Buster turned the Falcon into the sea and we edged slowly astern Brian climbed over the stern and onto the marlin board and whilst I held on to his belt he tossed a tow line to the Votan. One of its crew caught it and secured it to the deck. We picked up the slack and started towing the Votan. This gave us a few seconds to gather our composure and time to discard our safety harnesses as they were severely hampering our movement and risking the success of the rescue operation. It was then that I saw off our bow the largest wave I have ever seen. I yelled to Brian to hang on and get back towards the tow post. The Falcon was 32 feet in length and we travelled from the trough of that wave up its face (at least three boat lengths) before crashing through the top few feet. I knew that the ketch would not make it. The tow line sliced down through the wave behind us and then parted and broke.

Although the tow line had broken, the Votan had enough forward momentum from our tow to make it over the top of the massive wave, but after that it began its inevitable march back towards the reef, propelled by the incessant wind and waves. Without hesitation, Buster spun the Falcon around and again approached the ketch. We threw her our second (and last) line, which they caught and tied it on. We had only towed it out about 50 meters when two huge waves rose up in front of us but somehow passed under us. They broke right in the spot we had just left. I remember I was near the tow post with Brian and we looked at Buster who yelled, "The Lord is with us today boys"; we had just escaped certain destruction by a few meters and a couple of minutes. I have never forgotten that moment or those particular words.

We towed the Votan a few hundred meters away from the cliff, and, because we didn't have any more tow lines, Buster decided that we couldn't afford to leave the people on the stricken ketch. He acknowledged that it would be very hazardous, but decided we had to retrieve them in the dark. We slackened off and edged closer to the ketch. When we were within throwing distance, I tossed them a life ring and yelled to them to take it in turns to put on the ring, jump in the water and we would pull them aboard the Falcon one at a time. We did this five times without too much of a problem considering the conditions. Brian Friend stood on the tray and hauled each one up onto it. I held on to his belt and the tray and hauled each one up onto it. I held on to his belt and helped the survivors over the stern and into the cockpit and told them to get into the wheelhouse. One of the survivors became insistent that we rescue their dog that had been left on the Votan, but our duty to preserve human life far outweighed the risk to life it would have involved if we tried to rescue the dog.

One crewman had a lacerated leg that was bleeding profusely. I tied my belt over the wound to stem the blood flow and placed him on the wheelhouse floor between Buster and me at the radio/navigation chair. We put two passengers on the floor in the trunk cabin - there were two single bunks but they did not have larboards and would be very difficult to remain in them in the conditions. The two others were placed in the two small bench seats in the wheelhouse.

With the Votan still in tow, we headed for Cape Three Points and on to Broken Bay. We were aware the Police launch NTW Allan was seaward of us and approaching from the south, but we could not see each other. As darkness approached, we thought we may see the navigation lights of the NTW Allan but to no avail. The wind and the sea had not abated although we were thankful that it had not worsened.

Day 1: Map indicating the movements of the Votan

About 1830 hours, Buster took his bearings off the Norah Light House and became aware that the Norah Light House was in fact on our starboard beam. It should have been on our starboard quarter, which meant we were being pushed backwards. Some days later we learnt that although we were heading south, we had in fact been pushed five miles north and past the Norah Light House.

We held a brief discussion with the survivors, telling them that with the Votan in tow and with only one engine we were going backwards and suggested that we cut the Votan adrift. Although it was a difficult decision in one respect to deliberately leave a vessel that had survived so much and kept its crew alive by its obvious sea-keeping qualities, our survivors needed medical attention, and our fuel was not limitless. We also had to consider the unknown state of the weather, the fact that we could not locate the NTW Allan and our starboard engine had been playing up all day. We cast the Votan adrift at 1900 hours, and notified Sydney Radio who put out a Notice to Shipping, instructing mariners to beware of the possibility of a drifting ketch off the Central Coast or Newcastle areas. Everyone felt bad about the dog that had been left on the ketch, but ultimately we had no choice.

Then continued the longest and most uncomfortable and worrying voyage all three of us had ever experienced. To keep us well clear of numerous bomboras running on the reefs all along the central coast to Terrigal, Brian gave us a course further out to sea. I remained at the radio/navigation position talking to the NTW Allan, the RVCP vessel South-Pacific, Sydney Radio and the RVCP at Church Point.

We were keen to know a more accurate location of the NTW Allan as it was our only refuge if things went seriously wrong with the Falcon. The wind was still strong and the sea had not abated. It was agreed by the crew of the NTW Allan that we would fire a red parachute flare at a precise time. We did as agreed, and it was sighted by the crew of the NTW Allan, who we were able to establish were not far from us. In the following radio communication exchange, we established that we were invisible on their radar due mainly to the sea clutter on their screen, and we couldn't get a visual fix on each other due to the fact that we were in a trough at the same time as them. Firing the flare was not without incident. We had a very old pistol which was used to discharge flares and fire rockets with lines attached for rescue purposes. After Brian fired the first flare, nothing happened for about 15 seconds and then it went off. By then, however, Brian had lowered the pistol and the flare fired into the sea. We were very lucky it was not pointed into the wheelhouse; it could have killed someone, set fire to the inside of the Falcon or generally caused considerable consternation. We had to make sure the next attempt was successful, as our supply of red distress flares was limited and we had to ensure we kept a couple in the event we needed them in the course of the night for our own rescue. As I said, the second firing was successful and was sighted by the crew of the NTW Allan.

Relentless Assault

The assault by the waves and wind was relentless. The current state of the sea had been experienced by most Water Police on the NSW coast at some stage in their career, but not for such prolonged periods of time. Usually such experiences are for much shorter periods of time, and in more defined locations such as a bombora, reef or a lee shore like the high cliffs leading into Port Jackson. The waves came on like soldiers: no stopping, no hesitation, and no respite from their size or make up.

The Falcon was only a vessel of less than 10m and each wave we climbed up was twice the length of her. The exceptions were those that capped due to the wind velocity and the top meter or so fell on top of us. My two crewmates both had extensive experience in surfboats over the years. Buster later related that he started looking for a set' (when a prevailing sea is running usually, a certain number of large waves will be followed by a number, or set, of smaller waves), but this did not happen. Mariners and surf boat crews look for these sets to get an opportunity to turn about in heavy seas, or do something on the vessel they had been putting off. He counted 50 large waves at one point and gave up counting. The winds were around 100 knots in velocity (170kph), and were constantly ripping the tops off waves and dumping the contents on top of us. This went on without respite for hour upon hour. One of my niggling fears was that the winds and sea would dislodge our radio aerials and void our communications.

The Falcon was only a vessel of less than 10m and each wave we climbed up was twice the length of her. The exceptions were those that capped due to the wind velocity and the top meter or so fell on top of us. My two crewmates both had extensive experience in surfboats over the years. Buster later related that he started looking for a set' (when a prevailing sea is running usually, a certain number of large waves will be followed by a number, or set, of smaller waves), but this did not happen. Mariners and surf boat crews look for these sets to get an opportunity to turn about in heavy seas, or do something on the vessel they had been putting off. He counted 50 large waves at one point and gave up counting. The winds were around 100 knots in velocity (170kph), and were constantly ripping the tops off waves and dumping the contents on top of us. This went on without respite for hour upon hour. One of my niggling fears was that the winds and sea would dislodge our radio aerials and void our communications.

The Barrenjoey Light House flashes in a group of four. It is visible for 19 nautical miles in normal conditions. The troughs and peaks were such that we were only about two nautical miles off the Barrenjoey Light House before we saw a completion of the four flashes. I recall Buster Brown saying, "...that is the first time I have seen the four flashes."

The storm was one of the two worst experienced on the Sydney coast in the second half of last century. The storm surge created on the Saturday and Sunday was sufficient to stop the tide running out of the Hawkesbury River. The Pittwater also failed to empty and the public wharf at Palm Beach had about half a metre of water over its deck planks. Ironically, the other storm - and perhaps worse - was only a month earlier when the beaches lost their sand and the Manly fun wharf and pool enclosure in the harbour was swept away.

South West for 'The Joey'

The hours passed by and when off Cape Three Points, it was comforting to at last make a slight turn to starboard and head towards Broken Bay. Buster had decided to lengthen the trip a little by travelling well south of Maitland Reef which was extremely dangerous in most seas let alone this southern swell we were experiencing. When the NTW Allan and the RVCP vessel South Pacific (20m motor cruiser) had us on their radar, I believe we all started to feel a little more comfortable. When we cleared Cape Three Points, Buster was quite excited that he saw a flash of the Barrenjoey Light on the low horizon. We were about 12 nautical miles north east of the light. The Joey, (the name by which it stands with the Broken Bay locals) was home.

We rounded Barrenjoey Light about 0130 hours and entered The Pittwater. We proceed to the Royal Motor Yacht Club at Newport where we had arranged for ambulance officers and police to meet us. The club was chosen principally because the ambulance had access right up to the launch. The survivors were given a brief examination by Doctor Hardy off the AVCG vessel Leslie Anne, and were then transported to Mona Vale Hospital. They were all released the following day.

Coronial Inquiry

The body of Adrian Wedgwood was never located. The City Coroner, J.D. Goldrick, held a Coronial Inquiry into the circumstances surrounding his disappearance.

About the death of Adrian Charles Hamilton Wedgwood he found that, “the above named on the ninth day of June 1974 off the coast of New South Wales near Tuggerah Reef in the said state died then and there by drowning when he was accidentally washed overboard when the yacht Votan overturned. I further find that the body of the deceased has not been recovered but I am completely satisfied that such death actually took place and I find accordingly"

Glebe Coroners Court, tenth day of October 1974 Signed J.D Goldrick, City Coroner.

The Inquiry had actually completed taking evidence on the fourth of October, however a number of people wished to record comments on the incident, the subsequent rescue, and the actions of those involved.

Mr I. Ward represented Adrian Wedgwood and was of the view that, “…if there wasn't any evidence of negligence, then at least it would have been prudent for the people who undertook this journey to have taken into consideration the experience they didn't have, the defective engine, and the fact that they should have assessed the weather conditions and got out of the area".

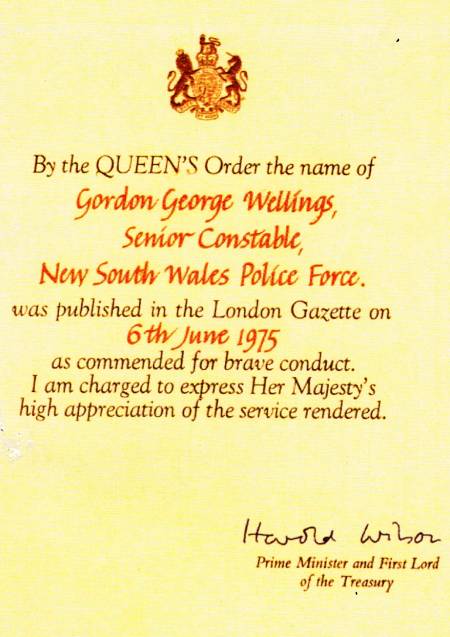

Sergeant Noel Short, assisting the Coroner, spoke very highly of the crew of the Falcon. He recorded that "... at any moment during the rescue operation they could also have lost their lives", and that they performed their duties “…far and beyond what would normally be expected of a member of the Water Police…”. He further stated “I submit this will probably rank as one of the most meritorious rescues ever carried out in Australian waters…”

Recognition  What pleased me at the time, as much as any favourable comments, was the way Sergeant Short and the Coroner Mr Goldrick, recognised the significant role played by the crew of the NTW Allan, the Royal Volunteer Coastal Patrol vessel South Pacific, the Australian Volunteer Coastguard Broken Bay and the two very brave Surf Life Savers who supplied the initial response to the incident in the power boat from The Entrance Surf Club.

What pleased me at the time, as much as any favourable comments, was the way Sergeant Short and the Coroner Mr Goldrick, recognised the significant role played by the crew of the NTW Allan, the Royal Volunteer Coastal Patrol vessel South Pacific, the Australian Volunteer Coastguard Broken Bay and the two very brave Surf Life Savers who supplied the initial response to the incident in the power boat from The Entrance Surf Club.

The press covered the rescue in a very positive manner, nearly to the point of embarrassment. It was good to see the NSW Police Force being congratulated instead of being criticised as they often are. I always found the sabre rattling that takes place, mostly without foundation, quite disconcerting and disappointing.

Later that year, we were all awarded the Commissioner's Commendations for Courage (The highest Commissioner's award at the time) and the following year, in 1975, at Governautical Milesent House, we were awarded the Queen's Commendation for Brave Conduct.

Reflections

How did the Votan get there? It has always seemed incredible to me that a large ketch couldn't get into Broken Bay. From approximately 1200 hours on the Saturday they repeatedly tried, under sail and motor, to get in but to no avail. After a night at sea in terrible conditions, it drifted north past Cape Three Points until it rolled over off The Entrance. I am amazed that no other vessel saw them all day Saturday; there were no flare sightings reported to the Water Police, RVCP or Coast Guard and no person or vessel was reported overdue or missing.

State of the Sea

It was not until the next day and then for many years later, that I reflected on the size of the sea that afternoon. The trio of waves that reared up in front of us and began to break as we secured the first tow line was the most dangerous I have encountered. I have reflected on this over the years and although I have probably encountered larger sets of waves, I have seen none that were steeper or more dangerous than that on the day. We all believed that if we had been 30 seconds later, or 50 meters further in, the breaking wave that crashed where we had just pulled the Votan from would have reduced both our craft to driftwood, and all eight lives would most likely have been lost. Even so, the Votan was fortunate that we had the line secured which kept the bow of the ketch facing the waves, and although the line, had broken, the Votan still had enough forward inertia to break through. As we dropped over the back of that first wave, the utterance of Buster Brown that “The Lord is with us today mate,” has remained indelibly etched on my mind.

Falcon

If Lady Luck has a hand in the course of events, then she was certainly busy that weekend. The Falcon had been programmed to be taken to Sydney Water Police on the Saturday for repairs to the starboard engine. However, Buster had made the decision not to go due to the workload inside The Pittwater caused by the high winds. If the launch had gone to Sydney, there would have been no other police vessel in the area to rescue the stricken Votan.

Petrol engines are now regarded as dangerous due to the possibility of highly volatile petrol leaking into the bilge or some other area of a vessel from a broken fuel line or petrol tank. They can also become unreliable when exposed to excessive moisture, which could have been one of our main issues that afternoon as the starboard engine kept cutting out.

Ship Mates

During the entire rescue, Roper Lars Scott 'Buster' Brown remained at the helm. He declined relief as he felt that, after a couple of hours working with the vessel and its temperamental engine, he was best placed to anticipate its behaviour. In the 20 years I served in the Water Police following this rescue, I have seen drivers who were as good as Buster, but none better. I remain enthralled as to his seamanship and skills.

Brian Friend was fearless. He scampered around a wildly pitching and yawing launch Falcon all day. He did not hesitate to climb over the stern (there was no gate), and balance untethered on to the marlin board to pull the Votan crew out of the water. The lucky survivors from the Votan will attest to the value of his SLSC skills, as he ran round the vessel looking after them for the entire trip back to the Royal Motor Yacht Club at Newport.

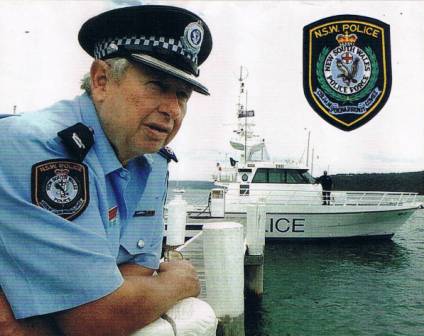

Picture: Police Launch Falcon crew (from left): Senior Constable Gordon (Boot) Wellings, Sergeant 3rd Class H. (Buster) Brown, Constable First Class Brian (Friendly) Friend. Image courtesy Brian Friend.

I worked four radio frequencies for most of the journey; the Police Radio (VKG), the ship to shore working and emergency channel, the Volunteer organisations channel, and the two-way chatter channel between us and the NTW Allan. When I had the chance I helped Brian with the survivors, however, apart from keeping them warm. there was little we could do. When Brian wasn't running around the vessel putting something back in its place, or fixing something, he was madly keeping track of our course and position. Whenever we had the opportunity, we would take a break, which amounted to no more than the simple pleasure of standing adjacent to the tow post and watching the backs of huge waves as they disappeared behind us into the darkness to the north.

Above: Police Launch Falcon crew receiving awards - image courtesy Brian Friend.

Workmates

The Australian ethic of helping out our mates when things are difficult was demonstrated personally to me that night by Sergeant John McNamara of Mona Vale Police Station. He knew that my wife was due to have our first born that weekend. From mid afternoon when he commenced duty, he contacted my wife on the hour until 0100 hours, to reassure her of my position and that she should contact him immediately should she require transport to hospital. The irony of that dawned on me the next day that while my wife waited at home for ‘broken waters’ to herald the dawn of a new life, I was hoping that "broken waters" wouldn't take mine.

Water Police in 2011

Having read this account, you could be excused for thinking the Water Police vessels at the time were ill equipped and inappropriate for such tasks, and by today's standards, you would be right. However, in the 60s and 70s, and even earlier; they met the standard, and in fact were all we had. Police launches at the time were not required to be built to Marine Survey. There was no requirement as to who built them and with what material, as long as they satisfied the tender requirements. Most were built of timber, however during the 80s, a number of steel and fibreglass vessels were built. All had petrol engines and it wasn't until one blew up at the Sydney Water Police that a hasty decision was made to change all engines to diesel. Diesel motors had not been favourable up until the late 70s as they were not regarded as high performance with good speed and were very noisy.

Today's vessels are required to be built to Survey, are very large and strong and capable of travelling many hundreds of miles to sea and remain there for days. What the boats lacked in appropriateness we made up for with experience. The common denominator from the 70s to the present day is just that - experience. One cannot learn it, you can only learn from it. It is an individual's decision on how they get it, and how they benefit from it. It was experience and seamanship particularly from Buster and Brian Friend that took us out there and brought us back in one piece.

The equipment on today's vessels was not imaginable in the 60s and early 70s. There have been huge developments in technology, such as the increased capacity of radio communications, of navigation equipment, and of computers. When this rescue happened, we were only 30-odd years out of the Second World War, which was when radar had been developed. It was still in its infancy on pleasure craft and only the larger cruisers and commercial vessels carried it. Today, of course, every vessel has it, and the crew are trained to operate it. The safety equipment has to meet the Survey standard, and each vessel carries an array of distress equipment, first aid kits and associated equipment.

At the time of this rescue, the only qualification I had to have to operate the launch was a Radio Operator's Licence and a Coxswain's Certificate, which was the entry level qualification for commercial/professional drivers. Today, the crew of a police launch must have an advanced first aid qualification and appropriate Marine Certificates of Competency for the length of the vessel. These certificates ensure a satisfactory training in trouble-shooting engines and mechanical equipment, as well as training in fire fighting, navigation and driving experience, to name a few.

Author's Post Script

I was a member of the NSW Police Force for nigh on 40 years; 20 of those attached the NSW Water Police, 10 as Commander, and two as Commander and acting Superintendent of the Olympic Marine Security.An act of bravery? What is bravery? I believe that is for others to decide. From the moment we rounded the Joey and saw the sea we were entering, we were apprehensive. When we turned to towards shore off Norah Head to perform the rescue after the surf boat got lost we were scared. From the whole time we were out amongst the swells, during the rescue and to the point that we actually cut the Votan loose, we were terrified. From then on, until we got back to the Joey our terror abated to apprehension. A colleague once said "yeah but have you ever been shot at?" I said "No; but if I was, I would be frightened for a couple of minutes. In this voyage, I was frightened for almost the entire journey."

Gordon Wellings

Chief Inspector (Ret.)

Commander NSWPF Water Police

John Morcombe Gordon Wellings

WELLINGS, Gordon George (Boot) Passed away October 21, 2010. Late of Avalon Beach. Retired Chief Inspector NSW Police. Q.C. B.C. Dearly loved husband of Jean. Much loved father and father-in-law of Phillip and Rene, Brian and Lisa. Loved by his grandchildren Olivia, Tiffany and Harvey. Beloved son of Iris and George (deceased). Loved brother of Lindsay, John and Heather and their families. Aged 64 years "Gone to sea"

Published in The Daily Telegraph on October 23, 2010

Further:

Also included as part of this Issue, from former Avalon artist Christine Hill: The Story of the making of the paintings illustrating the “Falcon” rescue of “Votan” and her crew – Sunday 9th June 1974 by Christine Hill FASMA, written October 2011

Also see Brian Friend - Profile and Roper Lars Scott (Buster) Brown - ‘LEGEND of the SEA’ by Brian Friend, OAM-QCBC

Christine Hill at RMYC Marine Art Exhibition with one of the Falcon-Votan paintings.

Originally published in the Australian Police Journal, Volume 65. No 3. September 2011. Reproduced with the kind permission of Jean Wellings. Copyright Gordon Wellings and the Wellings Family, 2012. All Rights Reserved.