January 18 - 24, 2015: Issue 198

A Glimpse of the Hawkesbury.

By Francis Myers.

ILLUSTRATED BY J. C. HOYTE.

That blue glimmer of electric light along the quay gleams as the entrance of an infernal city, and the red lights above beam as the eyes of a thousand devils, and the smoke goes up as the smoke of a place of torment; for we brain-wearied workers, who have been ground in its mills for many months, are flying away to rest. Yes ; to rest amongst the cool sea spaces and the nodding caps and the sleeping islands and the majesty of beauty and the blessed peacefulness and quiet of that larger heaven within the heads of Broken Bay.' We travel by Manly, and a short hour's journey brings us to that fair suburb. From Manly, by the primitive old coach, to Pittwater. Horses rough, harness rough, coach shaky, road bumpy; still, however rude, right pleasant work, for the great white Easter moon floods all the land with silver sheen and mystery. The low hills rest like sleeping creatures with folded wings, the still lakes are as great glassy windows through which spirits of the inner world might peep at the outer glory, here and there stands a tall palm as a sentinel, and rounding headlands by the open sea the murmur of the waves come up as of a million sea doves cooing through their dreams.

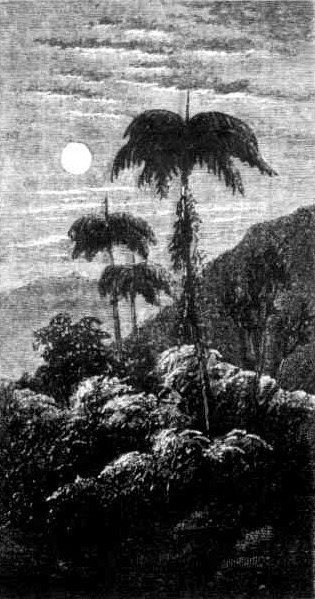

That blue glimmer of electric light along the quay gleams as the entrance of an infernal city, and the red lights above beam as the eyes of a thousand devils, and the smoke goes up as the smoke of a place of torment; for we brain-wearied workers, who have been ground in its mills for many months, are flying away to rest. Yes ; to rest amongst the cool sea spaces and the nodding caps and the sleeping islands and the majesty of beauty and the blessed peacefulness and quiet of that larger heaven within the heads of Broken Bay.' We travel by Manly, and a short hour's journey brings us to that fair suburb. From Manly, by the primitive old coach, to Pittwater. Horses rough, harness rough, coach shaky, road bumpy; still, however rude, right pleasant work, for the great white Easter moon floods all the land with silver sheen and mystery. The low hills rest like sleeping creatures with folded wings, the still lakes are as great glassy windows through which spirits of the inner world might peep at the outer glory, here and there stands a tall palm as a sentinel, and rounding headlands by the open sea the murmur of the waves come up as of a million sea doves cooing through their dreams.

A FEW TALL PALM TREES STAND AS SENTINELS.

High shorelands sink to shelving braches, and there through the weird water the pink sand flushes, as the cheek of a young Endymion to the kiss of the lady moon. Still tearing along with wboop, and halloa, and much persuasion to the tired horses, and by a quick turn upon a sidelong track into woodlands high and dank and dewy, all dark below save for the glimmer of a few white starry flowers, but fringed with silver aloft, for it is midnight, and the moon is in mid heaven. And 'twere well if we could all go to heaven for an hour or two, for the mundane aspect considered in mundane fashion is not inspiriting The journey is ended, and from a grim house comes a grim custodian, gaunt and churlish. House, man, and furnishings all much alike — better forgotten, o-better, perhaps, fixed in memory as things seen upon the shores of that lovely water in the Easter of 1883. What will it be in '93? Certainly it will not be fairer than it appeared at the very earliest dawning of the following day. Look outward and be happy, for the sunrise has not yet lipped the hills. The lovely purple uncrowned by one single gleam of gold deepens to indigo upon the edge of the water, which in its centre reflects the gray of the sky and the dying lights of some few pale twinkling stars. The birds are piping timidly as fearing to break the solemn hushfulness.

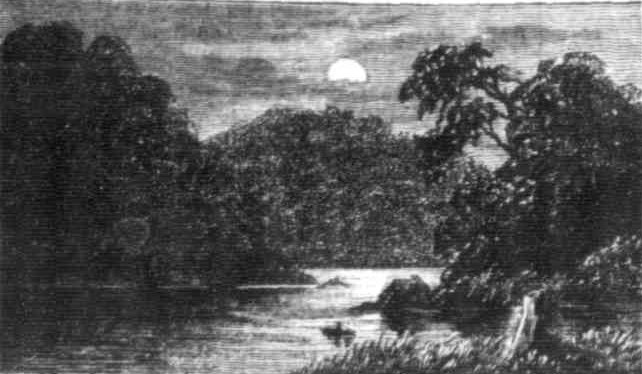

NEWPORT BASIN.

The tall trees hold every bough and branch and tiniest leaflet motionless. Only the blue mist quivers waiting, waiting — and suddenly, swiftly as the unfurling o1banners at a trumpet blast, a red light flashes on the high clouds to the westward, and the blue mist is burned up, and the glassy face of the water is broken, and the mystery of beauty of the dawning is thrust out of the world be for the glorious majesty of the day. The day spreads his livery of gold and brightness upon All the hills. The day smites the inner waters and the outer deeps with his strong hand and the white caps leap and flash, and the surges ring upon sand and rock. But very soon that white sail we are awaiting comes stealing, floating, gliding on, compelling the little fluttering breeze to her will, straight up the mid channel and round with a flutter of canvas abreast the narrow space of half civilized shore. And quickly we are on board and at rest.

There is no rest in the world to compare with that perfect abandonment, that absolute repose which comes with the idle lap of water against the vessel's sides, the near shores drifting backwards, a new heaven and a new earth perpetually opening ahead. At noon that autumn day we sailed into ' The Basin 'and dropped anchor. Ten years hence the article will be qualification enough for that basin. It will be no more necessary to ask what basin than what queen when Englishmen stand together to do allegiance. There are beauties enough within our own harbour gates, but they areas tiny pearls to an emperor's crown-jewel when compared with this. Here is a deep, still pool, a Constance, a Leman, a Katrine filled twice a day with the vigour and freshness of the strong sea tides.

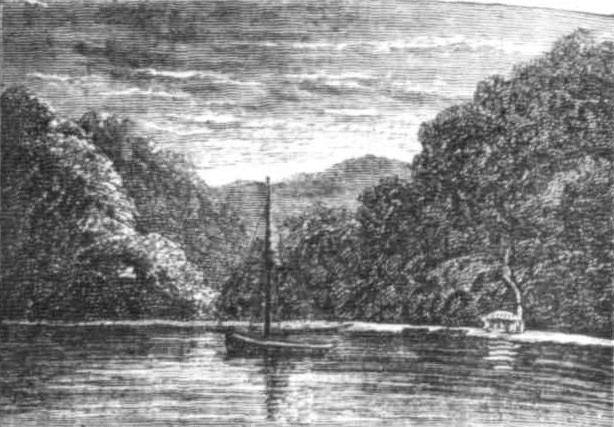

THE INNER BASIN.

THE OUTER BASIN -MARY ANN'S HUT.

Round Barrenjoey comes the swirling rush, rolling along the eastern harbour branch through the deep channel, washing the point of the sandspit, whispering on every beach, and lapping gently at the rocky base of every cliff, then resting for a quiet hour while the sun sets or the moon rises, and some few strange birds chirp contentedly in the forest. The hills, of a lordly size in the daylight, rise huge and vast when the moonshines. The great tree trunks below are scarcely perceived, but above, each leaf edge touched by the white light sparkles and gleams, and the waterfall sings louder through the dark, dank fern, and lazily-moving oars strike fire from the blackness that is barred from shore to shore by the long moon rays. Strange that no poet has sung of the mystery of the moonrise, the dawning of the night light. It is colourless but marvellously beautiful, a perfect revelation of all the divinity of form. 'What will the future show us about that basin's banks? Houses, homes, pleasure grounds, one of the chief playfields of the city ? It has marvellous capabilities. Room enough upon the promontory jutting out from cliff toward cliff for such an hotel as we have not yet seen in Australia, water enough, always smooth and still and pure, to give battle space for half-a-dozen warships, or to bathe a nation, and water that about three chains of stout sea- fencing would render absolutely safe against all sharks and finny monsters.

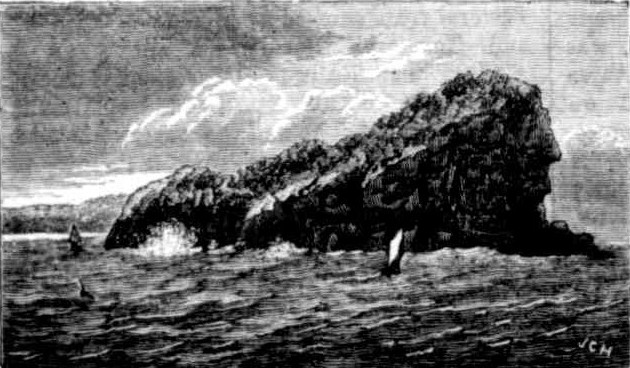

BARRENJOEY.

Now, a yachtsman's cottage and a fisherman's hut occupy the promontory, and for 11 months out of the year there is no more life or appreciation about the basin than about some lone tarn of the backblocks upon whose shore has been erected a boundary rider's hut. Morning brings us a dip in the lazy rollers upon the sand, a splash beneath the fresh water, raining from the ferns, a great breakfast of the black bream that swim into the fish-trap, poor foolish creatures, innocent and trustful as if their home were a thousand miles from any dwelling of man. Noon sees white wings spread again, and a further flight towards undiscovered beauties. Seeking the true Hawkesbury, we beat down abreast of the Heads, past the long sandspit coupling Barrenjoey to the mainland, regarding with much interest the huge,

grim, wave-washed, time-worn crag that lacks but around tower and a romance to fetter it to the hearts of a people. It bears a lighthouse useful to the mariner, but only vexatious to the dreamer. Wild and strong and stern frowns that rock with the sea foam at its base and the few sparse wind-tortured trees about its bead. It should have memories other than those of lamp- trimmers' yarns and convicts' jeers and groans.

And Elliott Island, lying almost in mid-channel, is also an artist's rock, so strangely shaped as to be capable of any comparison ; a lion couchant, a headless sphinx, a remnant of some giant's work of the world's strong youth worn down to vast indistinctness by winds and waves. Ah ! let us recall one evening when moored off the west head, the island and the rock, with every distant point, and all the dome of Heaven and the spaces of the sea, were seen transfigured and glorified by the out breathed spirit of a dying day. A thunderstorm had rolled over and lay upon the eastern bar and light from the clear inland western sky smote all its breast with fire. Some little shreds of cloud in midheaven let down a film of rain which bent the rays till they made bows upon the thundercloud, three separate trichord bands of light upon three points of distant land, an intense blackness below, and beyond a strange rich purple and greyness. Right out in the fore

ground Barrenjoey, his face as the face of an angry giant, every line, point, dent, and scar glowing as with the fire of an inward-born passion, and separated but by a silver band, the lovely Elliott Island cradled in blue water, fringed with the leaping foam, swathed in a silver haze that deepened to golden mist, end darkened too soon to a purple veil, all evanescent and beautiful as a dark proud woman's smile, and yet, thank God, in memory perpetual.

ELLIOTT ISLAND.

Round that West Head the river's mouth, or rather the ocean estuary, divides, and as we keep to the southern bank for a time the land is dreary, its monotony only broken by occasional fringes of sand and damp ravines, down which the waters flash, or trickle silently through wondrous mate of ferns, dense masses of luxuriant colour these ferns, showing every varying tints of tender green and rarest brown, the withered fronds above, dyed in the richest blood of autumn. But they are meanest details, thumbnail sketches in the great gallery. A merrier breeze pipes up from seaward, and in an hour we enter darker water, brown with all the silt of the big river, robbed of its beauty by the land stream and of its usefulness by the tide.

PEATE'S FERRY.

Dangar Island stands midway in the stream, an island that is not all rock, bearing at its seaward end some evidence of cultivation, and showing in many ways capabilities of usefulness which will not be developed. It would have made a splendid park for the people of the suburbs that will one day crown those hills. It would fulfil every requirement of a quarantine ground for the port of Newcastle. It might, had it been held, have brought a few thousands to the Treasury, but beyond enriching the lucky man whose name it bears it will never do much now. He bought it for less than £100, and less than100 years ago. Let it pass. How can we rest if the cares and crosses of the State are to intrude upon our holiday? The State may some day pay £10,000 for the island it sold for £80, but that £10,000 will be but as Dangar Island to Australia compared with the sum which will be required to complete the huge work which, coupling the next island with the mainland, will one day bar all further progress, or at least give peremptory orders —Down topmast !

Long Island is but a rifle shot from Dangar Island, and across Long Island run the red pegs denoting the chosen route for the Great Northern Railway to Newcastle. A thousand yards of water roll between the island and the Northern mainland, and across them must that railroad bridge be swung. Its construction will not be a childish task, but energy and perseverance will accomplish it, and proper care will keep us clear from both failure and caisson fever in its accomplishment. Long Island slips astern as the sun sinks down, and then farewell all railways, bridges, and works of trouble or rare, for just ahead looms Fairyland. The breeze dies, and the low flat rays or sunlight strike all the central sheet of water to the similitude of a silver shield. The water blazes with the white glory, and the low mangrove island seems quivering, melting, consuming away, and every headland is swathed in mist, as by the rising Spirit of the Water, and point after point, distance beyond distance, the beauty, the mystery, the glory increases and gathers till,' where the cones of the Sugar Loaves kiss the sky, the promise of a gorgeous sunset shuts in the view.

THE RUINS.

Round by the Sugar Loaves runs Berowra Creek, where any time of night or day or dawn or eve makes glory. But life is short, and holidays are not the greater part of life. We saw little of Berowra Creek, and are happier therefor, leaving its ungotten gold to gather up on another day. The anchor was let go that night but a little distance above the old ruins of Peat's Ferry. Poor old ruins, they are only a ghastly chimney and a few poor tottering walls ; a roadway all grass-grown and broken, and a few English trees and flowers in a waste of rank luxuriance. Doubtless it has a history, as no house and home ever grew and crumbled to decay without some threads of passion and pathos, and sorrow and joy, and love, which, gathered and woven to an intelligible whole, should present the warp and woof of the one great human romance clearly as the gorgeous fabrics woven amid the 'steelshod rush and the steelclad ring,' and the grinding dungeon keys and the wronged women’s wails and the tortured men's groans of the Rhineland of the medieval time. But the threads of this romance are scattered so widely we may not pause to gather them.

Only at early morning they lend themselves to the landscape, and lit by its strange light, and swathed in its weird mists, have a beauty that cannot be denied. But what narrowest space of heaven, or earth, or sea, lacks beauty when that rose of dawning blossoms and opens its heart of gold ? From the lovely western skyline to the highest heaven a thousand thousand angels were moving earthward.

' They all were saying Bencdictus qui venis,

And scattering flowers above and roundabout.’‘

And a colour breaks upon the sea as if some land god of the nether world surged upward with a brow of defiance. And the very hills are transfigured, lit as by an inborn fire, transmuted from sullen blackness to purple bases, with cones and crowns of molten gold. The heart leaps up with a shout, with an Io Pasan ! at the sight, for then the summons of that most notable canticle is answered :

'All ye mountains and hills, bless ye the Lord, praise him and magnify his name for ever.

All ye powers of the Lord, bless ye the Lord, praise him and magnify his name for ever.'

Alas, that there should be any end of dawning or of evening ! Alas, that the moments of true joy should be to each man's life as the flush of dawning to the long monotonous travail of the day. We bathed that morning upon the sandy spit of a mangrove island. Rabbit Island it is called, and the mangroves there grow into strange, fantastic, though occaisionally graceful forms. Close down on the beach one larger than his fellows, arches and dips to the water forming a frame in which any breadth of the river scenery may be set— fairy pictures, gem-like, amongst the master-work.

THE MANGROVES.

Down the stream again, for that dawn of life, the holiday, is waning fast, and whatever is missed in the narrower waters and nearer beauty above, there is the blue Cowan Creek which must be seen; and drifting down past the familiar islands and marking the still smooth depth of Refuge Bay as an evening camp, we enter the narrower water and the higher hills.

Cowan Creek is grander than that grim canon which 1makes the cul de sac of the Lane Cove estuary— broader and deeper in the water-filled gorge below and the cloven hills above than the Nepean above Penrith. At its entrance lake-like, broad, deep, and char with bold water up to the cliff bases, whose fronts rise 600 feet, in places sheer perpendicular. The clouds sweep down upon their heads in gray weather, and the long gray folds trail as mourners' garments on the wind that sighs or wails through the trees, Great eaglehawks dive downward for the fish, and rise on clanging wings echoing from cliff to cliff. And in un-clouded summer weather the blue atmosphere is seen as a palpable actual presence on the topmost heights— is felt as a companionship, only shaping itself in dreams. It is a strange solitude.

The big yacht runs her jib almost into the cliff fronts as she swings around on the short tacks, the water is so deep and safe from shore to shore. Up some steep gullies little blue feathers of smoke are seen, and learned men whisper of distilleries and say all the revenue Her Majesty's Customs receive from the Lower Hawkesbury would not clear the grog drunk by the women over 70 or the children under 15. There is something illicit in the appearance of some of the habitations; the men's faces are secretive as the leaden worm of a still, and the women seem as creatures of a new race. Strange people! They might enjoy all the comforts and many of the luxuries of life if they  would but fish with industry but what is fishing compared with watching a pintpot still and listening to the yarns of the elders, of floggings in Market-square and bushranging in the mountains? Most of the present inhabitants of these mountains, woods, and waters are relics, wearing out as other relics, soon to be talked of around hearths and campfires, but only to exist in memory.

would but fish with industry but what is fishing compared with watching a pintpot still and listening to the yarns of the elders, of floggings in Market-square and bushranging in the mountains? Most of the present inhabitants of these mountains, woods, and waters are relics, wearing out as other relics, soon to be talked of around hearths and campfires, but only to exist in memory.

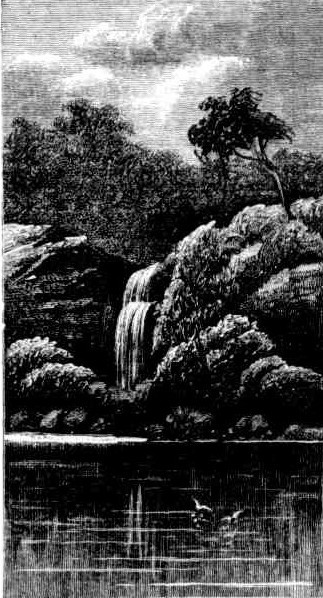

Refuge Bay is to be the palace of that night's repose, and to Refuge Bay we come as the light grows soft and dips low and the mountain shadows lengthen. Refuge Bay has no transcendent beauty. Its waters are calm and deep, its beaches bright; the wooded hills close about it on three sides, fair in form and luxuriant with foliage. Down a rocky face of its eastern side a waterfall tumbles — only a shower in dry weather, plashing musically, and giving life to giant ferns and creepers about the rocks ; but a leaping torrent when a thunderstorm has flooded the morass above, shouting in greeting to the echoing hills and in defiance to the unceasing ripple of the tides below. The waterfall is the best remembered feature of the bay, when upon the last day of our voyage all the loveliness and glory and rest of the place is left behind, and Barranjoey draws nearer; round about his base the high waves dashing with voices of anger or joy, out in the channel he guards, blue billows rolling, each with a comb of foam, and away upon the skyline a breeze that comes down to us as we sight the southern headland and bellows out the huge sail, and drives the leeward gunwale down into the seething, rushing blue.

THE WATERFALL (AFTER A SHOWER).

No more rest now; pace, life, motion, strained cords and canvas humming, and the strong jib biting at the waves ahead like a fierce sea creature's bill; but the brain is clear and pulse is strong, and all the cobwebs are swept out of the dusty corners of the brain. Work seems once the chief necessity of life, though memory may be its joy. The North Head hangs to the south, Barrenjoey north, both rather as signs in the clouds than as cliff fronts on the sea. The long beaches and the long points are passed one by one. We are abreast of Manly a mean and unlovely township as viewed from the ocean. A big ketch lumbering along under a marvellous spread of canvas, is overhauled and left behind as we enter the Heads, and before the sunset we are close in to the garden of man’s making beneath the towers of Government House, and making ready for home. The trip is ended: the little poem of life has been lived, many new flowers have been planted in the garden, new pictures hung in the galleries of memory, new friendships have been made, not with man or woman, but with the beings who live wherever Beauty lives , with the spirits whose smile is the glory upon the hills, the laughter upon the waves, and whose language is the emotion of gladness which comes wherever Beauty is perceived.

OFF WEST HEAD, BROKEN BAY.

A Glimpse of the Hawkesbury. (1883, April 7). The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912), p. 640. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article162078253

________________________________

Note: These Illustrations would have been made from woodcuts- engravings- no photography then Kiddies!

A VETERAN ARTIST. DEATH OF MR. J. C. HOYTE.

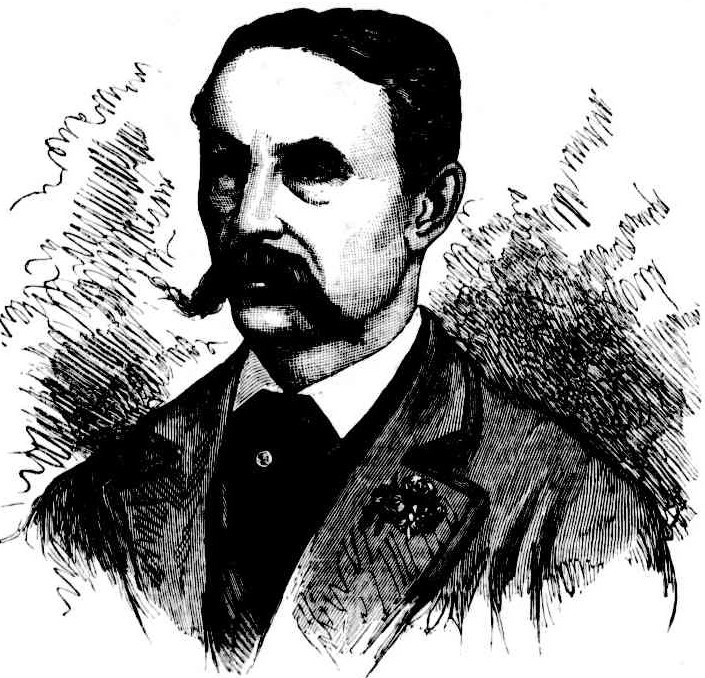

By the death of Mr. John Clark Hoyte, which occurred at his residence, 141 Avenue-Road, Mosman, on Friday morning, the art world of Sydney loses one of its oldest identities. Mr. Hoyte was born in England in 1835, and received his early artistic training there, but some years of his early manhood were spent in the West Indies. Returning to England about 1860, Mr. Hoyte married, and shortly afterwards decided to go out t0 New Zealand, where some time after his arrival he joined the teaching staff of the Auckland Grammar School.

It was about this time that Mr. Hoyte's artistic work began to bring him into prominence. It was not long before he occupied a leading position in New Zealand art circles, and it is as a portrayer of the scenic beauties of the Dominion that he will be long remembered. Right up to the time of his death his work found keen appreciation there. About 1877 Mr. Hoyte left New Zealand, and settled in Sydney.

He was one of the founders and the first president of the Royal Art Society, among those associated with him at the time being Mr. A. J. Daplyn, the present secretary of the society. Of late years Mr. Hoyte had been but little before the Sydney art public. He was one of the old school, and found it difficult to adopt his ideas to the conventions of the newer artistic cult. The deceased has left a widow and two married daughters (one daughter having died some years ago), and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren. A VETERAN ARTIST. (1913, February 25). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 8. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15400595

THE VICE-PRESIDENT, JOHN C. HOYTE, ESQ.

THE VICE-PRESIDENT, JOHN C. HOYTE, ESQ.

Mr. Hoyte is an Englishman, born in London,1837. He was sent out in 1856 by the firm of Denoon and Co., to Demorara, as bookkeeper and head overseer on their estate, but after three years' residence, on account of ill health, he returned to England, and came out to Auckland in 1860. He remained there 16 years, being for some, time engaged as second master in the Church of England Grammar School, and as a private tutor. He was also an officer in H.M. Customs. In 1869 he determined to devote himself to art solely, and was appointed secretary to the Auckland Society of Artists, which post he retained till his departure for Dunedin in 1875. He was also about the same time elected as a member of the Academy of Arts, Melbourne. In Dunedin he was a member of the council of the Dunedin School of Arts; after three years residence there he left Kew Zealand and came to Sydney. In July, 1880, a society was established here, the promoters being Messrs. A. and G. Collingridge, and at the general meeting for election of officers, etc, Mr. Hoyte was unanimously elected president. This office he held for one year, and used his utmost endeavours to promote the welfare of the society, but feeling that his being a comparative stranger in the colony might prove detrimental to the society, he resigned in favour of the Hon. E. Combes, being appointed vice-president for the current year, which office he now fills most satisfactorily.

The art society with which these gentlemen are associated, is gaining public confidence and esteem, and we gladly welcome it as one of the permanent institutions of New South Wales. THE VICE-PRESIDENT, JOHN C. HOYTE, ESQ. (1882, January 7). Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907), p. 17. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article70964090

Extract of biography:

Later, many of his drawings were reproduced as wood engravings in an illustrated Sydney newspaper. But the most significant instance of commercial art work of this kind is a book written by his son-in-law, Francis Myers, The coastal scenery, harbours, mountains and rivers of New South Wales, which was published by the New South Wales government in 1886 and extensively illustrated by Hoyte.

Life for Hoyte was, nevertheless, 'a continual struggle to live', although 'it is not for the sake of trying, I never leave a stone unturned'. In Auckland his career had clearly gone reasonably well, for by 1875 he was the owner of a house and grounds with an estimated market value of £550 and paid rates of almost £3. However, there is no trace of his ever owning real estate in New South Wales, which suggests that his last years were more difficult. He died, apparently intestate, in the Sydney suburb of Mosman on 21 February 1913. He was buried in the Church of England cemetery, Gore Hill, the following day. Rose Hoyte died four years later, in January 1917.

Two testimonies allow us to glimpse something of Hoyte's personality. Among his pupils at the Church of England Grammar School in Auckland was Charles Lush, whose personal diary reveals Hoyte as a man who was at times a strict disciplinarian, but was also a gentle and rather vulnerable figure. Lush records how on one occasion a pupil 'was very impudent to Mr. Hoyte, and as soon as school was over Mr. Hoyte went over and complained to Mr Kinder [the headmaster] about him and says that if the boys choose to insult him that way, he will leave the school.' However, the warmest assessment of the artist appeared in the Otago Daily Times just after his departure for Sydney in 1879: 'Quite free from the too common jealousy of other artists, he rarely had a word to say against the work of another man. Ever ready to help the amateur or struggling artist with useful advice and example…he made for himself a considerable circle of friends – among the general public on account of his sterling worth, and in our small artist-world'.

Hoyte, John Barr Clark: 1835–1913, Artist, teacher

This biography was written by R. D. J. Collins and was first published in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Volume 2, 1993

Retrieved from: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2h52/hoyte-john-barr-clark

MYERS-HOYTE. -November 3, at Christ Church, St. Leonards, by the Rev. A. Yarnold, Francis Myers, journalist, to Emily Rose Marianne, eldest daughter of John Clarke Hoyte, artist, of Bridge-street and North Shore. Family Notices. (1882, November 6). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13516578

The coastal scenery : harbours, mountains, and rivers of New South Wales / by Francis Myers ; with illustrations by J.C. Hoyte.

Author:Myers, Francis.

Published: Sydney : T. Richards, Govt. Printer, 1886.

Physical Description: 76 p., [30] leaves of plates : ill. ; 30 cm.

Subjects: New South Wales -- Description and travel -- 1851-1900.

Notes: "Prepared specially for the Colonial and Indian Exhibition."

OBITUARIES OF THE WEEK

Mr. Francis Myers.

The announcement of the sudden death of Mr. Francis Myers at Jindabyne (N.S.W.) on July 22 will be received with deep regret by all who knew and admired him as a fine journalist and a" graceful writer (says The Melbourne Argus). Mr.Myers, who embarked in journalism as a career in New South Wales upwards of 30 years ago. first made his mark in Victoria when, as "Telemachus." he succeeded the late Julian Thomas ("The Vagabond")as the writer of a series of Saturday sketches in The Argus, chiefly upon "Picturesque Victoria," He had something of the spirit of the romantic mountaineer, and, though picturesque nature in all its aspects attracted him, he turned naturally towards the mountains. One of the finest sketches he wrote for The Argus was "Cloudland and Snowland," a description of Mount Kosciusko in midwinter, and it is a singular coincidence that, after the lapse of years, he died while journeying to revisit these old scenes. In Nature animation appealed less to him than form, colour, and atmosphere. He had the giftto paint in words the picture that roman cists in art love to put upon canvas. In youth "Telemachus" had evidently spent much of his time in the arid lands of Northern and Central Australia, and was saturated with the spirit of it—the cruelty of the long drought, the time of desolation, not less than by the colour, the freedom, the far-stretching plenty of the genial ears. Of literary worth he was an admirable judge, and latterly much of his time and talents were given to that particular form of criticism. He wrote two novels, and nothing could be more unlike in tone and style than "Abishag the Shumanite" and "The Flame Tree." In temperament he was a complete Bohemian, trusting much to inspiration, and with perhaps something of a contempt for industry, which in the Bohemian spirit be regarded as the resource of the plodders in any profession. Exceedingly fond of club life, of those social pleasures which stimulate good-fellowship, he was ever a pleasant companion, a cultured and agreeable conversationalist, whom men of kindred tastes loved to meet. But tastes such as these were not the best equipment for a man who had already accepted the more serious responsibilities of life, and upon whose exertions others were dependent. Reflections upon that phase of his sanguine, happy character will cause those who knew him best to admit the high merit of the work he did, and regret the better part that was not accomplished. For some years past Mr. Myers, whose health had broken down, was a freelance in journalism. OBITUARIES OF THE WEEK. (1907, August 3). Observer(Adelaide, SA : 1905 - 1931), p. 38. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article163166154

Telemachus (/təˈlɛməkəs/; Greek: Τηλέμαχος, Tēlemakhos, literally "far-fighter") is a figure in Greek mythology, the son of Odysseus and Penelope, and a central character in Homer's Odyssey. The first four books of the Odyssey focus on Telemachus' journeys in search of news about his father, who has yet to return home from the Trojan War, and are traditionally given the title the Telemachy. Telemachus' name in Greek means "far from battle", perhaps reflecting his absence from the Trojan War. Homer also calls Telemachus by the patronymic epithet "Odysseus' son".

THE LATE MR. FRANK MYERS,

At the inquest held at Jindabyne respecting the death of Mr. Frank Myers, a well-known Sydney journalist, ' the evidence was that the deceased, with other tourists, proceeded from Cooma to Jindabyne on July 18. The journey was continued towards the mountains on Friday, when deceased found the air too keen, and complained of pains in his chest. He remained at M'Guffick's hut that night, and returned on Saturday to Mr. L. Harnett's residence, where every attention was given by the family and Constable Lynch. He gradually sank, and died early on Sunday morning. T. Henderson, of Adaminaby, stated that death was due to heart disease. The funeral was largely attended. THE LATE MR. FRANK MYERS. (1907, July 27). Evening News(Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931), p. 2. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article112646699

THE LATE FRANK MYERS. A BRILLIANT AUSTRALIAN WRITER.

Frank Myers, truly brilliant journalist, llittle dreamt that he would end his days' down by Kosciusko, but so it happened. He had been deputed to write a- series ofarticles on the snow country, but death overtook him at Jindabyne on Monday ere he had time to pen a line. Mr. Myers was, we believe, English-born of Jewish extraction, and although he had little to say of his young days in the old land there was small doubt that much of his great ability was fostered in his youthful training. The year 1880 saw him at work in the back country of Australia as a surveyor's assistant. Here it was, face to face with Nature in her varying moods, that he acquired his wonderful descriptive power as a writer on the glory of the bush which has charmed readers innumerable. Like many another clever writer, he was called to Sydney from his lonely haunts through the success of his contributions to the 'Bulletin.' Then, some twenty five years ago, he joined the staff of the 'Sydney Mail' and did some clever workf or it, the 'Echo,' and the 'S. M. Herald.' A tempting offer from the 'Argus' induced him to transfer his services to Melbourne, where 'he gained a considerable reputation under the pen-name of 'Telemachus.' The 'Argus' selected him to write up everything of importance, whether it was the Bourke flood or the Jubilee celebrations in Sydney ; and brilliantly indeed was the work performed. Some years ago he became leader-writer on the 'Australian Star’ when ability had some share in its darections but with the transfer of the services of its capable writers to other journals.

Mr. Myers Went South once more, and wielded a free lance in Tasmania and Victoria for some years past. Prior to and since that period he wrote for the 'Freeman.' A few weeks ago he returned to Sydney, cheery and hopeful as ever, but his iron frame, which had withstood more than a man's share of misfortune, largely self-imposed, succumbed at last, and he laid him down for his last sleep in the shadow of Kosciusko at the comparatively early age of 53. The scene of his death had been that of his early bushwork.

The present writer first met Frank Myers on the staff of the 'Globe' and the 'Sunday Times,' then under 'the editorship of Mr. Gresley Lukin, formerly of the 'Queenslander,' and now editor of a leading N.Z. journal. Myers was then doing editorial and descriptive work, and kindly encouraged young writers whom he was pleased to regard as promising. At that period he wrote a finely-turned description of Manly on the occasion of the local flower show,' what time it was opened by Lady Carrington. It was published in pamphlet form, and delighted the denizens of 'The Village.' The late Mr. E. C. Westlake, later on the 'Daily Telegraph,' was then sub-editor of the 'Globe,' and he discouraged the quotation of poetry by anyone except Myers, who introduced his article on the flower show with the well known lines: Sparkle full well in language quaint and olden, One who dwell eth by the castled Rhine As he culled the flowers so blue and golden, Stars that in Earth's firmament do shine.

Inspired by this example, a junior reporter essayed to drop into verse over the flower show, but his lines — ;'And strange-shaped flowers of gorgeous dyes, Unmoved by any wandering breeze, Look out with their great scarlet eyes, And watched me from the giant trees,' were remorselessly blue-pencilled by the prosaic sub-editor. And when the young writer would essay smart political paragraphs, Myers would say 'put a sting in it,' and it was Sir Henry Parkes and men of his day received many a rapier thrust. One of Myers's first instructions to a young writer then conveyed through the editor was to write a parody on 'Barney M'Guire's account of the Coronation''' in 'The Ingolds by Legends,' on the late John Young's celebration of Queen Victoria's Jubilee, what time Mr. Young was 'Mayor of Sydney. The lines were written and revised by Myers, who made little or no alteration, and they appeared in the 'Sunday Times'- of that day. All of which goes to show that he aided and inspired young writers whenever and wherever he could do so, just as those other giants of journalism, J. F. Archibald, W. H. Tiiaill, and Oresiey Lukin helped on young men who gave any sign of future success. A great admirer of the gifts of the late W. B. Dalley, Frank Myers wrote much of surpassing interest concerning that gifted Irish-Australian.

Of poor Meyers's weakness it is not meet to speak here. He shared it with many a man of genius, and suffered accordingly, but in his bright moments he was a laanip to the feet of aspiring writers — 'cheerful, laden with good reading, and picturesque reminiscence. Among his several novels were 'Abishag, the Shunammite ' and 'The Flame Tree.' Mr. Myers, on his return to Sydney, became associated with the 'Australian Star.' In addition to his other work, Mr. Myers was the joint author, with Frank Hutchinson, of 'The History of the Soudan Contingent,1885.' His wife, a daughter of Mr. Hoyte, the well-known artist, died about five years ago. He leaves three daughters and two sons. THE LATE FRANK MYERS. (1907, July 25). Freeman's Journal(Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1932), p. 26. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108040140

Twenty Golden Years Ago,

FOR THE 'FREEMAN.'

Everything was very gay and fine and splendid in those dear clays of twenty golden years ago. Sydney was not then gripped in the cold hand of dull obstruction apathy. Money rippled harmoniously over a pebbly brook-bed of prosperity. Metaphorically men burnt the promissory notes of their enemies as a sacrifice to future fortune. We were celebrating with a perfervid furore the anniversary of our first hundred years of history. Cannon boomed enthusiasm with aggressive-insistence, and squibs and crackers, illumined the purlieus of Wexford-street and outcast Woolloomooloo — and Woolloomooloo was fairly outcast in those prehistoric, remote times. Then, Bohemia was still an impossible 'inland seaport.'

Daley and Caddy and Harold Grey were wont to foregather at the 'Pirate's'--a playful name bestowed by the illuminati upon Captain M'Laughlin, who Wore a huge black beard and moustache, and spoke in ten or eleven languages. The captain was a vast institution, and ran a wine Bodega, to which Dan 0' Connor Used some-times to pay a ministerial visit. Holdsworth and Crick and Patsy Bourke were visitants, and were wont there to engage in wordy warfare. At the time of which the present scribe is writing, ''The Picturesque Atlas' Company was busily engaged in 'Wynyard square' creating the three, great and beautiful art volumes. Dr. Andrew Garran; LL.D, M.L.C.., arid subsequently Vice-President of the Legislative Council, was editor-in-chief, and to my own connection with the 'Freeman's Journal' and the kind offices of Mr. Thomas Butler (then editor of this paper) the offer was made to me by the 'Atlas' directors, of the associate editorship. The premises of the leading Catholic journal in Australia were practically within a stone's-throw of the large building in Wynyard-square, and friendly communication was continuous. At the 'Freeman's Journal' office, palatially imposing after the quaint and tortuously-staired building in York-street, opposite the old Central Markets(now pulled down), the writer made the acquaintance of a host of brilliant men, among whom he can still count many true and constant friend's. The younger generation had, however, not then arrived. The Roderic Quinns, the E. J. Bradys, and the Henry Lawsons had still to win their spurs.

Victor J. Daley flitted away to Melbourne, and there did sojourn for many years. But there were W.B. Dailey and Frank Hutchinson, and Frank Myers, and John Farrell, and 'Johnny' Hunt('The Flanour') and many, many others, some of whom have, alas! passed behind the veil. Dear old William J. Tarplee, J. W.Lambie, 'Jack' Soley, and 'Tommy' Elwell were then on the 'Sydney Morning Herald '; Hugh Mahon (now a member of the Federal Parliament), 'Jack' Danks, and Ernest Blackwell, on the 'Daily Telegraph' ; Terry was on the 'Evening News'; Harold Greyor Theodore Argles (otherwise 'The Pilgrim'), J. O'Brien, Victor J. Daley, John Warde, and F. J. Donohue ('Arthur Gayll')were all writing for 'The Bulletin.' Frank Hutchinson is today the doyen of the Sydney press; twenty years ago he was one of the most notable men in the city.

He often collaborated with Frank Myers, notably in the production of a History of the Soudan Contingent, which went campaigning in Africa in 1885. But Myers, brilliant, eloquent, and versatile as he was, never inspired the affection which seemed to irradiate the footsteps of the other Frank. Myers was more admired than loved. He lacked that abundant sympathy with which his confrere was full to overflowing. Young Hutchinson was only nineteen years of age when he first came to Sydney— as was Daley also, who was albeit a much younger man'. The 'Doyen' comes of a fine old literary family, and had for aunt that highly-cultured and sweet natured Mary Hutchinson, who wedded the poet Wordsworth. It is one of the inspiring reminiscences of Frank Hutchinson's infancy, that often he sat upon the knees or the dalesmen's poet and had his head caressed by the hand which penned 'The Excursion’ besides some of the noblest sonnets in our British tongue.

Frank Fowler (of the Sydney 'Month') was wont to boast in the brave days of old that he easily made a thousand sterling per annum as a journalist — unattached. But this was Frank Hutchinson's actual experience. It is over forty years since Hutchinson began to ply his pen for a livelihood, and for many years of that period he contributed from week to week, and from day to day, reams upon reams of racy comment, caustic satire, and weighty, pregnant editorial matter both to the daily and the weekly press. A valued and valuable leader writer in the columns of 'The Freeman's Journal,' he was also the life and soul of an evening paper now no longer in the land of the living, namely, the 'Echo,' of which for long doughty Frank Brewer, who was later succeeded by T. B. Clegg, was editor. Hutchison, who is still alive and in the vigorous enjoyment of perfect health, has as hear of memories of the older days absolutely Mount Morganic in richness and inexhaustibility, he had the friendship of many friends and the acquaintances of many enemies. He came into elesra and various contact with such notabilities as Henry Parkes, W.B. Dalley, Edward Butter, Q.C., Daniel Henry Deniehy, Henry Clarence Kendall, among a multitude of others. The world of a past Sydney he has read like the characters in an open book, but the man with whom, probably he was most closely associated was Frank Myers, a writer of very exceptional gifts. It is worthy of note that on the occasion of the celebration of the jubilee of the Fort street Superior and Training School, the Ode was written by Frank Hutchinson, and was performed in recitative and choral parts by the two thousand or so scholars of the institution. It is a splendid and lengthy work and fittingly commemorates the founders of the school, namely, John Hubert Plunkett, Sir Charles Nicholson, and William Sharpe Macleay.

Frank Hutchinson’s fidus Achates and collaborateur in historical writing, Francis Myers, was as delicate a craftsman in the art of sentence-making as Benvenuto Cellini in that of cutting a cameo- Nothing that he touched did he not dignify. With the glamour of his style he could decorate a dingy hen-coop till it glittered as an Eastern palace of marble in the rays of a tropic moon or could burnish with resplendent adjectives a piece of orange-peel in a slum gutter and make it blaze in the sunrays as imperial gold. Among much other work, Myers put forth two novels, 'Abisag, the Sunamite' and 'The Flame Tree.' the first a romance founded on a Scriptural subject, the second a story of Australia. But he wrote much —his pen tereatted of prospectuses of land sales and permutated to pantomime. He was poet, critic, leader and descriptive article and storywriter, biographer, picture appraiser, and theatrical first-nighter — everything in turns as a literary craftsman, besides being a brilliant conversationalist and an enthusiastic clubman. He died only the other day while en route to Kosciusko, 'that Moscow of ours, 'as he somewhat magniloquently phrased it. He was a better prophet than he either hoped or anticipated to be, for like many another of the Old Guard, he perished in the snow-track before sight of the city was won by his veteran's eye- In Frank Myers we lost one of the most eloquent of descriptive writers, if not 'the' most eloquent. th«*.we ever po3SP«Bed in Australia.

W. B. Dalley was, of course, a great poet— a great orator, a great journalist, a great advocate and (although there be those who deny it) a great statesman. Most particularly, however, he was a great friend. He was a soother of dying pillows, a replenishes of empty purses, and a filler of empty stomachs. He was the Maecenas, the friend, the encourager, the helper of the man of letters, an unfailing staff in the days of old to the poet. Deniehy, Kendall, Farrell: all of them, and each in turn, were glad recipients of his bounty, hearkeners to his heartening voice. The writer has a pleasant reminiscence and this connection. Farrell was away up in the Blue Mountains battling along against adverse circumstances with a paper called the 'Lithgow Mercury,' at a time when every sovereign was worth more than a battery of artillery to a Napoleon nugivb. have been on an Austrian battlefield. Well, 'The Picturesque Atlas' folk had means of capital — much more capital than poetical appreciation — and Farrell, being my very good friend, I was anxious to dev.fee something which might possibly help a poet out of a difficulty, and provide, ways and immediate means. As associate editor of the 'Atlas' 'it occurred to me that a grand introductory poem from Farrell's pen would be a quite admirable way of encompassing several things at once and the same moment, of aiding Farrell, and of increasing the artistic value of the 'Atlas.' There was, however, very little hope of carrying the matter into being. As I before hinted, the directors were all purely business men — which mean is that poetry was not included in any manner in their calculation of dividends. Dr. Garran was, fortunately, very human, but most poetically critical. Moreover, he did not know, and had never met the poet Farrell. So when I suggested to him the desirability of an introductory Farrellian poem, he said simply : 'I leave it to you. I do not know anything about Mr. Farrell. You must talk to the managing director!' This, of course, would have been a hopeless business, absolutely foredoomed to failure. But I thought of something. The 'Atlas' directors wanted the use of Dalley 's influential name for all that it was worth — at that day a truly princely asset. To the very last limit of manoeuvering they employed every art of deference and flattery to induce him to write a page or two for them. The great man would not, however, be drawn; although, when, at a later date, Ernest Blackwell and a few friends put forth the 'Centennial Magazine,' D alley was good enough to lend it his prompt and powerful assistance with a page or two of some pleasantly-written 'Penseee.' But to return to Farrell's poem:The Managing Director of the 'Atlas ' voted especially to the promotion of a lively trade in sewing- machines, knew less about Farrell and about poetry than did Dr. Garran; and this is where my thought of Dalley's influence came in; I knew it would work wonders. I called on our statesman in his Castle by the sea, 'Marinella' — a medieval fortress in miniature, terrible with arms and armour, menacious with suits of mail, and resplendent with battle-axes and the burnished weapons of a day that is no more. A quiet suggestion evoked from him a hearty response in the form of a letter which I was able to place before the Board of Directors, and the outcome was Farrells noble poem, entitled 'Australia,' for which, with Dalley's invaluable and influential assistance, he received the not unwelcome sum of £60. Dalley was, however, a very old and consistent friend to Farrell. Long before the poet had taken to journalism as a means of livelihood — when, indeed, he was earning his family's crust as a brewer — he was wont to send to a few literary publications, of which 'The Freeman's Journal' was one, versed of varying calibre, few of which had not, previously been submitted to the great little man of Manly. I met Farrell for the first time quite a while before he had forsaken his vats entirely for his verses, and ceased to delight Queanbeyan with topical satire- Perhaps it was about- the end of 1886, or the beginning of 1887, that Farrell ,brought out 'How He Died,' and other poems (Turner and Henderson), and William Bede Dalley wrote a highly enthusiastic criticism thereof in the 'Sydney Morning Herald. He hailed the new poet as in Australian Bred Harte, and lauded the poetical gifts of Queanbeyan's popular brewer so warmly that Farrell was both prompted and enabled to embark on a literary life.' One concluding anecdote about Farrell: It is a fitting conclusion to his life as a brewer —hospitable and generous-hearted. Ic was ona New Years Eve, and the entire township turned out to greet their favourite citizens. Among others, the home of Farrell was visited. It was a two-storeyed house, and overlooked the roadway. It was midnight, or thereabout, and Farrell was on the eve of retiring. The crowd clamoured vociferously. Etiquette demanded that those called upon should stand treat- The poet came to the railing of the balcony and called into the night with generous gusto: 'All right, boys! You know I don't drink anything myself. But there are the keys of the brewery. Go down and help yourselves.' Amid the hurrahs of the crowd the keys jangled on the roadway.

Who can forget dear old 'P. J.' . He was an Elizabethan folio bound up in a modern frock coat, with a rosebud boutonniere lettering. Holdsworth, Ednie-Brown, and 'Tommy'' Elwell were inseparable in the old days when forestry was a department of the State, and not a neglected national asset. Nobody thought of calling the Poet Holdsworth other than 'P.J.' He was a very dear fellow; with a beautifully kind temperament, and an unruffable temper. He was, moreover, a fine bit of picturesqueness in a dull and unconventional world. For 'P.J' everybody had a huge and splendid affection— an affection unpurchasable by ducats or doubloons. He was a dandy of an ancient day, faultlessly attired always; punctiliously courteous to an extent embarrassing; urbane in the highest degree of a marked distinction. His tightly-fitting and closely-buttoned frock-coat was ample in its proud ... splendour touching almost the glowing boot tops of his shining patent leathers. His silk hat was immaculate, chaste in design, and a polished as a poem. His buttonhole was a dream of floral daintiness. His Malacca cane was adorned with the massive gold knob of a French marshal's baton. His style of beard-wearing was Shakespearean, after the mode of the Stratton-on-Avon bust, and his Elizabethan cast of features was an inspiration and a joy. 'P.J.' liked nothing better than to seize upon a crony pleasured friendship and true artistry, no matter how thronged the thoroughfare, and to strike an attitude, as that, say, of Napoleon addressing the deputies on the great day of the eighteenth Brumairo, putting one hand into the bosom of his coat, holding with the other a coat-button of his vis-a-vis, and reciting his latest poetical tribute to- his Queen of Dreams, or some other imaginary goddess of his adoration. He was a fine fellow, 'P.J.’ with a true and emphatic gift of creative genius, albeit no great poet ; and his heart was as golden in sympathetic generosity as it was red with generous sympathy.

As a writer of verse, 'Quis Sepatabit' touches as highest water-mark ; but he wrote besides other fine verse, distinguished as much by gracefulness of phrase as by felicity of fancy. He was a scholar and a life-long student who had bathed in the Helicon fountain of Hippocrene, and steeped his soul and head and heart in the noble literature poured with lavish hands by Shakespeare and the mighty brood who graced and glorified the great and spacious days of Queen Elizabeth. P. J. Holdsworth was, by the way, a contributor to the 'Freeman's Journal,' as were so many or the leading litterateurs of Sydney, before as well as since a score of years ago. Peace to his ashes and honour to his memory. He left a multitude of friends, and hardly an enemy behind him. When he came to Sydney Farrell struck up a close friendship with Holdsworth. This was inevitable, for they were the veritable image one of the other. The writer has given his impression of Holdsworth, Miecourtier. Farrell, the brewer, was his downright opposite. His clothes fitted him as would a sack a scarecrow. He cared for none of the trifles of life. Hearty, loud-voiced, humorous, exaggerative, Farrell filled the office of his paper with the great vastness of the genii confined by Solomon in the fisherman's vase. When he first wont to the 'Daily Telegraph' as editor (when the paper had the Single Tax fever) he dressed him in purple and fine linen; or, rather, he donned a hat of the kind known as 'belltopper,' a frock-coat, together with all the fittings and appurtenances of a properly laid-out citizen of influence and affluence.

But Fanrell had no fancy for cigars of select brand, and would stand in King-street, 'belltopper,' frock-coat, and all the gorgeous rest of it, cutting away at a plug of 'ruby' tobacco with a brown handled clasp-knife, and filling a meerschaum pipe with a bowl as big as the barber's basin in the immortal romance of Don Quixote. Farrell' s hands were always richly and rarely stained with nicotian essence, and after a hearty hand-grip his interviewer would carry away with him the odour of a vast Virginian plantation. But Farrell was a good soul, with a heart that matched his voice, and his voice was mighty and resonant as a brass band out for a holiday. Farrell had two distinctly Farrellian characteristics — we will not call them failings; he never knew when to cease quotation when once he began quote a favourite poet, and he never knew when to cease writing once he began to write verse. P. E. Quinn belongs to those days of twenty golden years ago. Quinn it was who introduced the present writer to dear old 'Tom Butler’ — that sterling friend to many of Sydney's knights of the pen, and brother to the brilliant and gifted Edward, 'Paddy,' as his friends called the elder of the two literary Quinns, was a splendid and audacious personage at that time, and quite unspoiled by Parliament- The younger Quinn (Roderic)was only a lad then, perhaps about seventeen years of age. Henry Lawson's first verse appeared, perhaps, about the beginning of 1887. Brady, also, was awaiting the clang of the call-bell. Well does the writer recall, however, that tall human construction, which he has heard described as the 'Gothic' Tarleton (a Bachelor of Laws, 'by the way), who was wont to perambulate the city like a Tuscan companion torn by violent seismic shock from its pedal fastenings in the solid granite. J. G. O'Ryan, another barrister in those days, was also often to be seen in the offices of the 'Freeman's Journal'; to say nothing of the brilliant Thomas Chrysostom O'Mara (a one time member for Monaro in our Parliament),and the no less brilliant but loss meteoric 'Dick' O'Connor (now of the Federal High Court), the ponderous and genial and able Sir Patrick Jennings, the Rev. John Milne Curran(to whom 'geology is a joke and mineralogy a jeu d'esprit), old Hary P. Mostyn (with his eternal red neckerchief), Francis Joseph Donohue (a cultured master of golden phrasing), William Ehard (who, as 'Timothy Fogarty' wrote reams of reminiscence and recounted of old time incident), J. Sheridan Moore (who not unworthily united in his own the names of two great literary Irishmen), Michael Mullins M'Girr (with the features of an elderly Cupid— a one-time part-proprietor), J. A. Delany(greatest of all Australian-taught musicians, and the remarkable Harold Grey (leanest and lightest of journalists).Delany was a very good all round man. Apart from his music, he was a thorough scholar, capable critic, and ready winter. His wit, humour, and power of repartee were of the first order. In tire company of the writer Delany was one evening walking home to Rushcutter's Bay. A tramp solicited alms with a breath which would have advertised Farrell's Queanbeyan brewery throughout a suburb. Delany, turning to the writer, inquired if the latter had any money, and being met with a negative, turned to the stranger, gravely proffering him his visiting-card, with the remark: 'Neither my friend nor I am in funds ; but come to this address at 9 o'clock to-morrow morning, and I will give you two pianoforte lessons for nothing.', FRED. J. BROOMFIELD.

A VIEW OF W00N00NA, LOOKING NORTH. Twenty Golden Years Ago. (1907, December 12). Freeman's Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1932), p. 53. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108037690

IN THE MATTER OF FRANCIS MYERS, A single meeting. One debt was proved, J. B. Holdsworth, £29 9s 10d. The official assignee, Mr. Mackenzie reported that all the assets were secured to a creditor under a bill of sale. Insolvent deposed to the correctness of his schedule and was examined by Mr. M'Cermick (Holdsworth and Brown): while in New Zealand I wrote to my father asking him to send me £250 ; I have received no answer, and I do not know if the money had been sent; it would come to the Thames branch of the Bank of New South Wales, and if sent would be a voluntary gift from my father. No directions were given and the meeting terminated. Insolvency Court. (1873, December 13). The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912), p. 758. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article162662287