July 20 - 26, 2014: Issue 172

Colonial Statistics. BROKEN BAY AND BRISBANE WATER - 1838

THERE is no part the colony within a hundred miles of Sydney, which has either been so long settled, or so little frequented by travellers from our colonial capital, as the country intervening between Port Jackson and Broken Bay. It is a broken, sterile, and uninteresting country for the most part; but there are particular spots in it of a much superior character, and the scenery in certain localities, especially along the coast, on the Narrabeen Lagoon and the inlet called Pitt Water is exceedingly fine. We happened to make a pedestrian tour from Manly Cove, on the north side of the harbour near the Heads, to Broken Bay a few weeks ago; and, although we cannot say much either for the country or the road, there is nevertheless sufficient to be gleaned by a careful observer ever in such a tour as to prevent us from saying, " it is all barren." In fact, as the finest flowers and shrubbery are generally found on the most barren land, it is not always the best land that will furnish the best subject for a good literary article.

An extensive bottom, as the farmers would call it, of the richest alluvial soil may be exhibiting to the delighted eye of the settler a splendid crop of maize; or a series of "flats," with not a tree upon them in their natural state, may present the finest wheat land in the world ; but we confess there is very little bottom for a good article in either case, and even a good writer soon becomes flat enough unless he takes a kangaroo leap to some subject of a more interesting or spirit-stirring character. To be threading one's way, how- ever, through a tangled wood while the loud roar of the vast Pacific's big ocean waves breaking ever and anon on the ironbound coast of this vast terra incognita, is sounding in one's ear like distant thunder, or like the roar of artillery — to mount one of those barren hills that stretch along the coast to catch a glimpse of the wild, but romantic scenery around from its rocky summit — to be walking by moonlight along one of the sandy beaches that line the shores of Pitt Water, the exact counterpart of one of our finest Scotch Highland lochs—to be arriving late in the evening at some small settler's farm, who has just been six months on his land, to be regaled with tea without sugar out of a common water-jug, and a piece of a damper—to sleep, or rather to attempt to sleep with a host of active little combatants as numerous and as formidable as a Roman legion— and finally to lose one's way for five or six hours in the bush, and to arrive at the North Shore with one's clothes so torn with the prickly shrubbery of that locality as to render it necessary to bivouac for a time till the sun has gone down on the town of Sydney, and darkness covers the land—these are the subjects which one can either write upon, or read about without getting tired or complaining of flatness.

There is a respectable family of the humbler walks of life settled at Manly Cove whose establishment exhibits in a very strong light, the immense benefits which this colony will eventually derive from the introduction of reputable and industrious families of a similar class in society into its extensive territory, under the admirable system introduced by the Whig ministry, in appropriating for that most important purpose the proceeds of all Crown land sold in the colony. The family we allude to is of the name of Parker. It consists of a husband and wife, rather past the middle age, and two stout young men, their sons. The father is a gardener, who emigrated with his family from England to the Cape of Good Hope a good many years ago, but preferring this colony, from all he had heard and read of it both in England and at the Cape, came on to New South Wales, leaving his third son in business at Cape Town. One of Mr. Parker's other two sons is a stonemason, and the other a carpenter and cabinetmaker, each of whom appears to be as much an adept in his own business as his father, who is a remarkably intelligent, shrewd, and well-principled old man, evidently is in his. Mr. Parker has purchased twenty acres of land and rocks on the eastern side of the cove, part of which he has laid out very tastefully, his two sons having been occupied in the mean time in erecting a neat stone walled cottage with suitable outhouses, part of the walls of both being the solid rock, which has been hewn away in certain places, and allowed to remain in others to suit the taste or convenience of the proprietor. In short the combination of mechanical force which Mr. P.'s virtuous and respectable family have been able to bring to bear on their little property is one of the happiest we have witnessed in the colony, and the result, we are confident, within a very few years hence will be the transformation of their twenty acres of rocks and land, hitherto deemed good for nothing, into one of the best cultivated, most romantic, and most valuable properties of its size within a day's journey of the capital. Mr. P.'s object has been to establish himself as a gardener and nurseryman, to supply the Sydney market with vegetables, fruit, fruit- trees, and shrubs.

As soon as a few small steam boats, such as ply on the river Mersey between Liverpool and the numerous little thriving villages along the Cheshire shore, are procured and set to work in our harbour of Port Jackson to ply between Sydney and the more important localities on the opposite shore, every acre of available land within a reasonable distance of the North Shore, will be increased in value several hundred per. cent. We are happy to find that an experiment of this kind is about to be tried by the establishment of a Steam Ferry Boat between Dawes' Battery and Billy Blue's Point. The establishment of such a boat will not only lead to the formation of several thriving villages on the North Shore, but will set an example which some people will soon follow by placing boats of a similar kind on other short courses within the harbour. Within a few miles of Manly Cove, from which there is a tolerable road for a considerable distance towards Broken Bay, there is more available land than we anticipated finding, and there is already something doing also in the way of improvement; the important operations of felling, fencing, and cultivating, being pursued by certain proprietors in that neighbourhood with some vigour. A very large portion of the land, however, is irreclaimably and hopelessly sterile.

On the banks of the Narrabeen Lagoon, a pretty extensive and romantic sheet of water situated about nine miles from Manly Cove, and communicating with the ocean in high floods there is a small extent of superior land for cultivation with a considerable tract of very fair pasture land belonging to the family of the late Mr. Jenkins, of Sydney; and about three miles farther on, towards the head of Pitt Water, there is a very fair cultivation farm leased to a small settler of the name of Foley. But the patches of arable land all along from Port Jackson to Broken Bay, are generally of such limited extent and the pasture land of such inferior quality to the forest land of the interior, that there must always be a very limited and widely scattered population in that part of the territory.

The South Head of Broken Bay is called by its native name, Barranjoey. It is a bold, rocky headland, situated at the extremity of a long narrow strip of land separating the main ocean from Pitt Water, and has evidently been an island at some former period, with a spit of sand running out from it towards the south. This sand-spit would be gradually extended by every gale till the island was at length married indissolubly to the main, the ceremony of joining hands having been performed by Father Neptune himself. There is a small patch of alluvial land of the first-rate quality near Barranjoey Head, on which a very industrious small settler of the name of Sullivan has set down, within the last few months, on a lease from Mr. Wentworth, the proprietor. The extent of land he has managed to clear and put into crop in so short a time, is as creditable to the settler as the splendid crop of maize and tobacco it bears is to the land. The neighbour-hood of Pitt Water and Brisbane Water is considered particularly favourable for the growth of onions, and the raising of that useful article of horticultural produce for the Sydney market, is the main dependence of the small settlers in these districts. The past season has been considered rather unfavourable, however, for this crop, the late rains, which have come in such good time for the maize, having been too late for the onions; but we found a very tolerable crop notwithstanding on various farms in both districts.

South Head of Hawkesbury River called by the Natives Barrenjuee [sic]. W.R.G. Image No.: a5504050 from; William Govett notes and sketches taken during a surveying Expedition in N. South Wales and Blue Mountains Road by William Govett on staff of Major Mitchell, Surveyor General of New South Wales, 1830-1835

The scenery near Barranjoey is romantic and interesting in a very high degree, the land and water being finely disposed for a picture, and the forest trees on the low ground along Pitt Water being remarkably umbrageous and beautiful, while the view from the Head itself — including the vast Pacific; Pitt Water separated from it by the narrow strip of land above-mentioned, and running up for the remaining part of its extent between two ranges of considerable elevation, and losing itself at length in the distance; Broken Bay, with the lofty, precipitous rocky island, called Mount Ellis, guarding the entrance of the Hawkesbury, and standing off, like a sentinel on duty, from its opposite shore, while the lower reaches of that noble river are seen stretching far inland between the lofty and barren ranges that line the whole extent of its course from the Blue Mountains to the ocean — all this is uncommonly fine.

Second or third-rate writers of literary articles of this kind regularly wish for the pencil of a Claude, or a Salvator Rosa, when they find themselves in such situations as we found ourselves in, to our no small gratification and delight, when we stood perched for a time on Barranjoey Head ; but as such idle wishes would not save any of our readers who might be desirous of experiencing the same pleasurable emotions, the trouble and fatigue of a long pedestrian tour through the bush, we shall not put ourselves to the trouble of uttering them. If any of our readers should be desirous of visiting the district of Brisbane Water, which we can assure them is well worth visiting, we would by all means advise them to postpone their visit till some of our enterprising colonial speculators shall have put a steam-boat on the course between Sydney and Brisbane Water.

For our own part we crossed Broken Bay in Sullivan, the small settler's small boat; and as there is a large extent of shallow water on the north side of the Bay, on which the sea breaks violently (whence its appropriate name, Broken Bay) whenever there is the least wind from certain quarters, we confess that sailing in such a vessel is somewhat dangerous. Rollers rise instantaneously, even in the mildest weather, in the Bay, and when one of these breaks on a small boat she is almost sure to be swamped, and all on board drowned. Brisbane Water is an inlet from Broken Bay, opening into the land at its north-eastern extremity. There is a reef of rocks extending for a considerable distance across the entrance from south to north, but the channel is sufficiently wide for those who are at all acquainted with the locality. The inlet, for a considerable distance up, is exactly like the embouchure of a large river, and as there are several other inlets of a similar kind opening into the main one, as Broad Water, Kingcumber or Cockle Creek, the district is a complete alternation of land and water, affording excellent means of communication for the settlers and most delightful scenery. Both along the banks of the main inlet and the other two just mentioned, there are settlers' houses for the most part picturesquely situated with a greater or smaller extent of land in cultivation around them according to circumstances.

There is much alluvial land of the first quality in the district, and the crop of maize, wherever we had an opportunity of observing it, was quite magnificent. Maize, onions, shingles, and sawed timber are the principle productions and exports of the district, and from the large quantity of these articles that have been exported to Sydney during the last few years, the settlers generally, we were happy to find, are in a thriving condition. Indeed, the district of Brisbane Water has sufficient resources for the sustentation and employment of a large population, and its vicinity to the capital will certainly attract numerous and reputable families and individuals as permanent residents in it whenever it is thrown open to the public by the establishment of a steam communication with the capital. From the want of such a communication at present Brisbane Water, although within four or five hours sail of Sydney, is virtually as distant from it as Port Macquarie, and till such a mode of communication with it is established, its re- sources will never be developed nor its rapid advancement both in population and in importance generally secured. It is a matter of astonishment, therefore, to us, that while there is such a rage exhibited in the colony, on the part of certain of our colonial speculators, for the extension of steam communication with Hunter's River, the capabilities of a district, so much less extensive it is true, but so much nearer hand, should hitherto have been so totally neglected.

There are at present three steam boats running between Sydney and Hunter's river, and a fourth is expected to commence plying immediately. Now, whether this is overdoing the thing or not we have no means of determining; but as the smallest and tardiest of these vessels will in all likelihood stand but an indifferent chance of success in competing with the others, we would by all means advise the proprietor to try the experiment of changing her course by causing her to ply alternately between Sydney and Brisbane Water, and Sydney and Illawarra. Neither of these districts is supposed to be at present sufficiently advanced to afford constant employment to a steam vessel of the size of the Maitland, but knowing both of them, as we happen to do, we are confident they would afford such employment to any vessel that would make a voyage from the capital to each alternately.

The machinery of the Maitland is scarcely powerful enough for her size, and although a good sea boat she is unable to make much progress against a head sea. She will therefore run the risk of being driven off the course when a third powerful vessel, to ply twice a week, is placed on the Hunter's river line. But her slower rate of sailing than that of the other Hunters' river vessels would be no objection either at Illawarra or at Brisbane Water; and although the proprietor might not realize his expectations by placing her on that course at the very first, we are confident that the rapid advancement of both of these districts, beyond all former precedent would not only be the certain result, but would amply and speedily repay him for all his original outlay. Verbum sat sapienti.

The Rev. Mr. Rodgers of the Church of England, and the Rev. Malcolm Colquhoun, of the Church of Scotland, have both recently gone to settle as ministers of the gospel at Brisbane Water. We most heartily wish them both all success.

Colonial Statistics. (1838, February 28). The Colonist (Sydney, NSW : 1835 - 1840), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article31720524

__________________________________________________

The Colonist was founded by John Dunmore Lang with a religious and political agenda. First published on the 1 January 1835 by Henry Bull and J. Spilsbury, The Colonist was published from 1835 until 1840, after which it was absorbed by the Sydney Herald.

John Dunmore Lang (25 August 1799 – 8 August 1878) was a Scottish-born Australian Presbyterian minister, writer, politician and activist. He was the first prominent advocate of an independent Australian nation and of Australian republicanism.

Lang was born near Greenock, Renfrewshire (now Inverclyde), Scotland, the eldest son of William Lang and Mary Dunmore. His father was a small landowner and his mother a pious Presbyterian, who dedicated her son to the Church of Scotland ministry from an early age. He grew up in nearby Largs and was educated at the University of Glasgow, where he excelled, winning many prizes and graduating as a Master of Arts in 1820. His brother, George, had found employment in New South Wales and Lang decided to join him. He was ordained by the Presbytery of Irvine on 30 September 1822.

Arriving in Sydney Cove on 23 May 1823, he became the first Presbyterian minister in the colony of New South Wales. On the way back from the second of his nine voyages to Britain (1830–31), he married his 18-year-old cousin, Wilhelmina Mackie, in Cape Town. They were married for 47 years and had ten children, only three of whom survived him. There were no grandchildren.

Find out more at: John Dunmore Lang. (2014, June 16). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved fromhttp://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=John_Dunmore_Lang&oldid=613090053

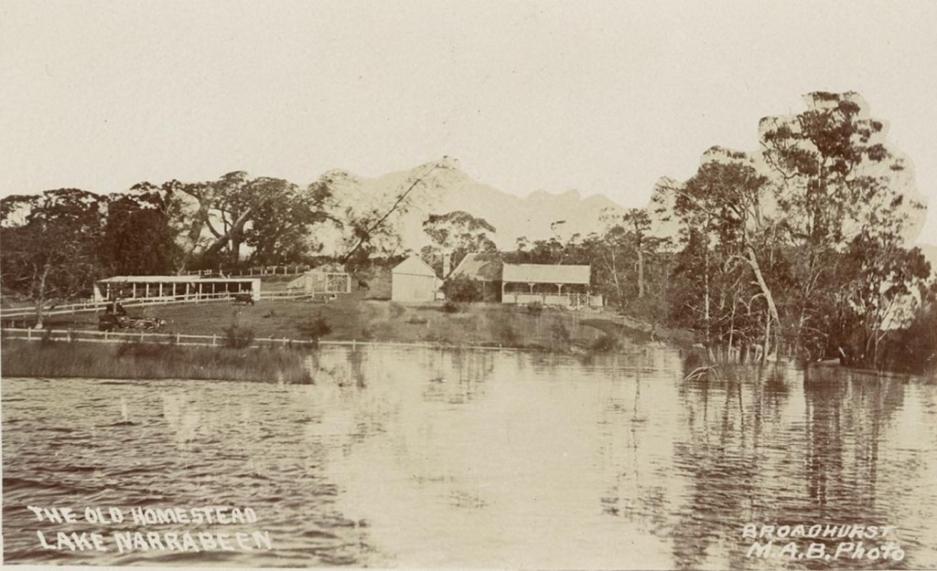

The Old Homestead Narrabeen (Wheelers) from: Scenes of Narrabeen, N.S.W., Sydney & Ashfield : Broadhurst Post Card Publishers, courtesy State Library of NSW - Image No.: a106064h