August 10 - 16, 2014: Issue 175

Bryan Webster

Mr Webster is a Whale Beach original. His days have been filled with being on the beach and contributing to the Whale Beach SLSC since a teenager. He is also current President of Palm Beach RSL (Club Palm Beach).

Bryan is one of the young Australian men who went to the Vietnam War and like all who have Served, did not come home the same as he left. To honour our Vietnam Veterans, whose Memorial Day and Service shall be held on August 17th, 2014 this year, and today, August 10th, 2014, at Palm Beach for the Vietnam Veterans (Northern), we have the honour of sharing a few insights from a wonderful Pittwater gentleman with a great sense of humour:

Where and when were you born?

In Sydney, 5th of November 1947 – Guy Fawkes Day, which seems prophetic now.

I was brought up in Whale Beach. My father lived in Whale Beach with his parents and he bought three blocks of land for a hundred pounds each over in Palm Beach, over the hill from Whale Beach. We ended up living on one of those blocks in a stone house, my father was a stonemason, as was his father.

My grandfather was the first permanent resident of Whale Beach – some say 1921, others say 1923, I don’t have the records to ascertain which it is.

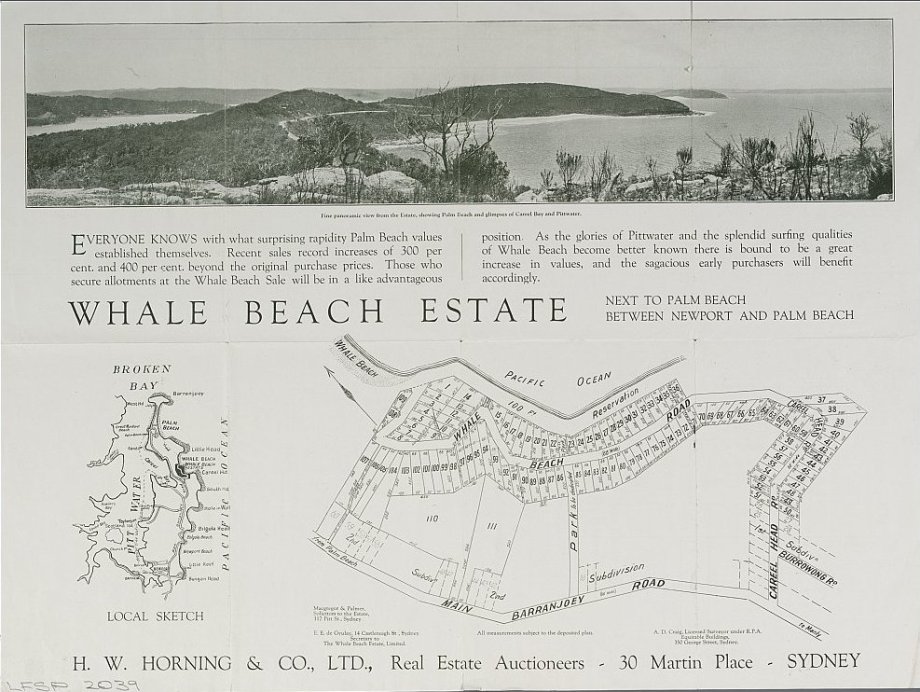

Whale Beach estate [cartographic material] 1921. MAP Folder 129, LFSP 2039. Above Part 1. Below Part 2 - courtesy National Library of Australia.

What was your grandfather’s first name?

He was John, but everyone knew him as ‘Pop’ – Pop Webster. My father’s name was also John but they called him Jack. My eldest brother was called John – it ran in the family I suppose.

My grandfather was given the job of organising the infrastructure for Whale Beach. This consisted of a crushed rock road. He had a gang of men who lived on the flat, on the dairy land at Careel Bay/North Avalon, some of them in tents.

They would come around, and Pop had a horse and dray and they would go around building this crushed rock road. This went along Bungalow road, from north to south Whale Beach – and this was joined up to Surf View Road, which came over the hill, to join on to Barrenjoey Road.

However, Surf View Road was shortened to ‘Surf Road’, and Bungalow Road, when it was finally joined up through North Avalon and around to Palm Beach, was renamed ‘Whale Beach Road’.

There’s many a trick where Surf Road leaves Whale Beach Road, it goes up in a series of dog legs or ‘s’ bends, that zigzags up the hill. My plans actually show it coming up at right angles (I live at the corer of one of these ‘s’ bends), and going straight up the hill.

What they forgot was that my grandfather only had a horse and dray, and a horse and dray couldn’t go up that steep incline, so he built the road as a series of ‘s’ bends that finally went up the hill and along up to Bynya Road.

There’s a lot of history of Whale Beach in the family – I’m the last of the Websters, the rest have died out now.

I love the place, I feel at home in Whale Beach. It’s a great place to bring up kids and grandchildren as well as it turns out.

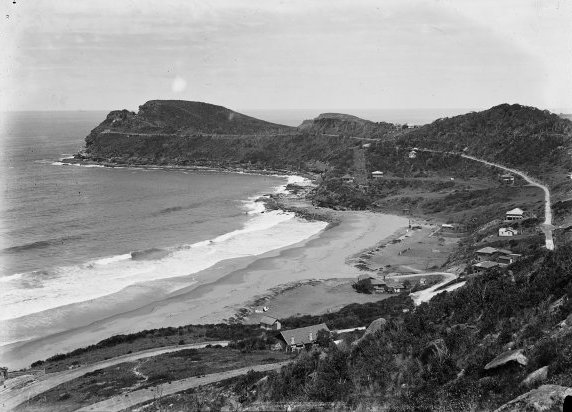

Panorama of Whale Beach no. 4 - (and blown up section from below), New South Wales between 1917 and 1946. Part of Enemark collection of panoramic photographs by EB Studios (Sydney, N.S.W.). Image No.: nla.pic-vn6152465, courtesy National Library of Australia.

Your grandfather was there pre-Jonah’s days then?

Oh yes.

So, what were the changes you saw during your decades here?

As a youngster I’d run up over the hill from the Pittwater side of Whale Beach, where I lived, and visit my grandmother’s house to check in with her, see if she needed anything; that was a precondition of me being sent to the beach as an 8 or 9 year old, see if she needed any milk or papers from the shop There was a little general store there in those days, Brandon’s had it when I was a kid.

Then I was allowed to go down to the beach and do whatever I wanted there – every now and then I had to check the front window of my grandparents house and if a tea towel was hanging there it meant ‘come up’; there was a message for me.

I had older brothers and younger sisters but I was the one really keen on surfing, surfboard riding initially, we had old planks to go on with friends, and then finally into the Whale Beach surf club at 15.

My father was the original captain back in 1937 and up until World War II; for the first three years he was the captain. He had got his Bronze Medallion at Palm Beach. All the local people finally convinced him that they wanted to start a club for Whale Beach and he was the only one with his Bronze Medallion.

My father was the original captain back in 1937 and up until World War II; for the first three years he was the captain. He had got his Bronze Medallion at Palm Beach. All the local people finally convinced him that they wanted to start a club for Whale Beach and he was the only one with his Bronze Medallion.

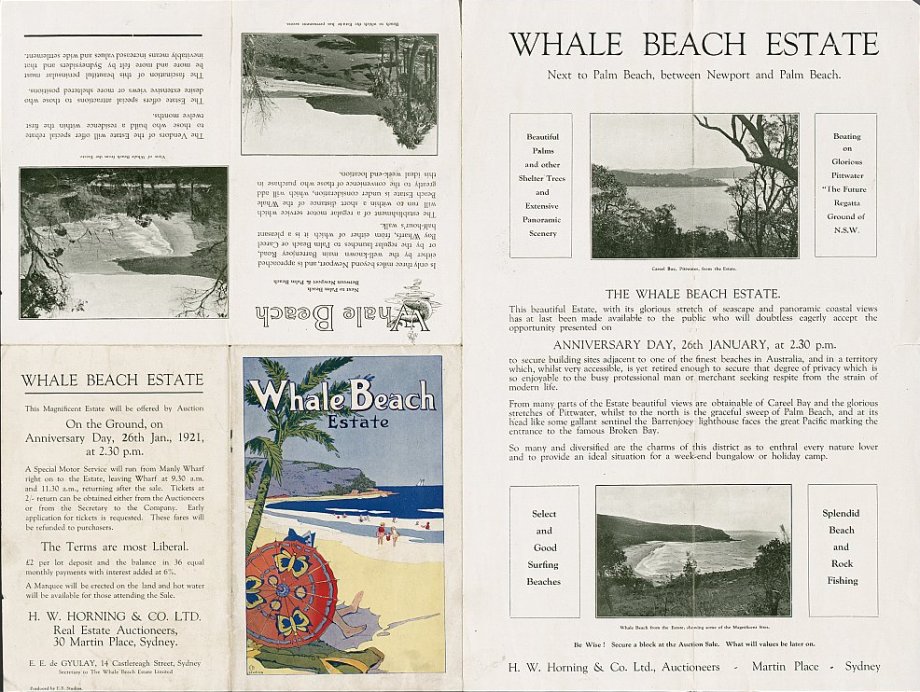

Right - Whale Beach SLSC members, 1938

He put through a Bronze squad, and they were successful in early 1938, Adrian Curlewis, as he was in those days, this was pre ‘Sir’, actually presented their Bronze Medallions and an Instructors Certificate to my father.

For me the Surf Club has been wonderful. I still have the friends I made over 50 years ago during my early surf club days, we still get together ad some of us are still heavily involved in the surf club. I’m currently the secretary and have been so for the last three years; I’ve held other positions and am a Life Member. I’ve been a Radio Officer and have been ever since this was installed in the surf club, back in around 1974 – so I’ve been the Radio Officer for 40 years.

The changes have been in the housing, all the bungalows have just about gone replaced by big houses – some of these are fabulously designed, others don’t seem to fit the landscape all that well while some have to be contoured to the block that’s available – my place is available at an astronomical price of course! (laughs).

Other changes would be that I used to wag school and go surfing at North Avalon and then the sods built a High School right beside the break at North Avalon, at our surfing spot! How cruel is that?

I’m fairly sure there are a few out in the surf even nowadays who possibly should be at school – where did you go to school?

North Narrabeen Boys – I then did my 4th and 5th year in town. Other people used to live in town and have a holiday house at Palm Beach. We lived in Palm Beach and had a holiday house at Leichhardt, dad bought it out of necessity.

My eldest brother, who had only just turned 16 when he did his Leaving Certificate and got excellent passes and scholarships to go to various places, settled on Kensington at the Uni of NSW. The old 190 bus route from here in the late 1950’s was a couple of hours to town and then another hour or so getting to the right bus and another half an hour out to Kensington – so it was five or six hours if you included waiting time or travelling time. He was too young to have a licence so dad bought a house out of his mother’s family – the former Mayor’s residence in Leichhardt, a fabulous old house.

It had gas light fittings which swung out of the wall, fireplaces in every room. When I moved there in the early 1960’s for a couple of years I had the ballroom for a bedroom. It had a concertina wall tat moved to one side and the ground floor – by pushing the concertina walls together I had a huge bedroom – it was phenomenal.

It had leadlight front doors, the windows were all leadlight, a slated roof. The mayor lived in one side and there was another side, it was a two storey house, and the deputy mayor lived on the other side; two outside toilets. They obviously looked after their mayors – it was built in around 1888.

I would be there Monday through Friday and as soon as Friday was done I’d be on the first bus back to the beach. I’d throw my dirty school uniforms into my mother’s waiting lap and disappear off to the surf club until Sunday afternoon.

We had a great group of guys, all men in those days of course. A lot of those boys came from the Strathfield to Epping rail-line and outnumbered the locals – there was only Chris Hendrikson and I and Phil Cullis, Peter Cane, Johnny Oliver was around at Palm Beach – there weren’t a lot of us who lived in the area – we would have been outnumbered ten to one.

Where did the chaps that came from elsewhere stay?

In the surf club. We had some bunks but you had to fight for the bunks with the seniors, who had right of way because they were bigger and stronger, so quite often you’d have a sleeping bag and sleep on the sand – I occasionally slept at Chris Hendrikson’s house, which was on the beach where the kiosk now is. We had a ball growing up there.

Of course on a Sunday afternoon the rest of the kids would go home and leave Chris and I to hang around.

School holidays were a magic time for us. You’d grow up seeing the changes coming – there’s more people that live at Whale Beach now on a permanent basis.

I can remember walking through there mid-winter 30 years ago and you’d see perhaps five lights on in houses – the rest were holiday places.

I can remember walking through there mid-winter 30 years ago and you’d see perhaps five lights on in houses – the rest were holiday places.

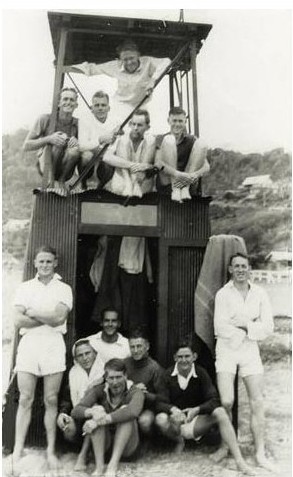

Right: Houses dotted on the hillside around Whale Beach, Sydney, ca. 1930s - Part of Fairfax archive of glass plate negatives. Image No.: nla.pic-vn6328733, courtesy National LIbrary of Australia.

When I was a kid coming home five lights would be a bonus. If you came home at night there were no street lights around Morella road – I’d walk back from the north end of Whale Beach, this would have been 1956 and there was a kid who had the first tv set that I knew of in Whale Beach – and there were very few houses, mainly bush. During winter you’d hear rustling of the possums in the pitch black, you’d be lucky to get a bit of starlight, the moon was a bonus; I’ve trodden on snakes in the middle of the road, certainly have seen them. I know for a fact that twice I’ve actually trodden on a snake. One of them whipped against me, obviously his eyesight wasn’t all that good either as he missed. I’ve no idea what kind of snake it was because he promptly slithered one way and I ran the other! But, I was barefoot in those days.

Where did you finish school?

At Knight Rocks Park – I finished school in Leichhardt so I could get away from the surf. I was distracted by the surf, and I went straight from school to the Air Force and joined at 17 and went in for six years – this was 1965 – I got out in 1971.

What training did you do?

Apart from rookies, which was fun because I was an adventurous soul…

You were a Boys Own Adventure man?

I rode surfboats, I was a beach sprinter and boat rower, paddled canoes, climbed rock faces and ran around the rock shelfs beside the sea as an exercise – played rugby, did all the right things. I was convinced by the media of the day that the right thing to do (was to enlist), and remember conscription was in then, the reds were under the bed, the hordes were coming – the domino effect – the media was very gung-ho; there was Robert Menzies, his period of time in the lead up to these years, and as a 15 year old, my formative years, I was convinced and had had an idea all along that I was going to join the Air Force.

I actually wanted to be flight crew but my mother was dead against it, she was scared of flying herself. She said ‘you’ll be shot’ – she was brought up during World War II when the fighting for Navy, Army and Air Force was pretty terrible, but the losses in bomber command were horrendous. There was also the media that she read of that time too, exacerbating that fear.

At any rate, I ended up going to be a Radio Technician for a couple of years down in Melbourne and became a Radio Technician – Airborne. I looked after aircraft, maintained aircraft, the primary and secondary radar systems, the communications gear.

I came back to work for the Hercules squadron. I was posted to Richmond; I actually wanted to go to Antarctica, to the Australian Antarctica Division – you could get a deployment to them for a year, year and a half; one of my lecturers was very keen on me going as I had a natural aptitude, and I was gung-ho, which you may have needed there.

I came back and worked for a Herc. Squadron for a couple of years and they then transferred me to the Caribou squadron at Richmond and I installed a secondary radar system – AWA had developed a secondary radar system which told you how far away you were from a fixed base station. This meant you could work out, if you looked at two fixed base stations, triangulated them, you’d know exactly where you were; it also gave you the rate of closure to that fixed base station if you were flying towards it- you knew how fast you were going and the distance – you knew the direction and how fast you were travelling. This was a great system. I installed that in the Caribous.

Just as I finished setting up the test bench I thought I’ve got less than 12 months to go, I’m set for life – I determined that at the end of that period I’d marry my girlfriend and things would look up from there.

They sent me to Vietnam. Typically gung-ho, I wanted to go. It was the end of 1970, things were turning a bit uglier but I was still fairly blind and thought if the government wanted me to go I should go.

I was ordered to go to Vietnam.. so…I went up there. I’d been up there a couple of times previously with the Herc.s flying in as part of the air crew and I’d been in a number of times flying into the bases to drop off personnel and cargo.

We’d go to Vung Tau – the run was Sydney – Darwin – Butterworth, which was in Malaysia and that was a day for each hop – day to get to Darwin, another day to get to Butterworth. We’d fly in to Vung Tau, where the Caribous were stationed. We’d fly up to Phan Rang where the two squadron bombers were stationed, the Canberras.

The Iroquois and Canberras were based at Vung Tau – we’d then go up to 2 squadron at Phan Rang and came back to Tsan San Nut, which is in Saigon (now called Ho Chi Min), and deliver any cargo or personnel…and pick up bodies, bring the caskets home.

We used to be a travelling hearse sometimes.

Then we’d fly back in to Butterworth that night, where we’d have a lay day because of aircraft hours, fix any faults on the aircraft in Butterworth where we had technicians stationed, and then we’d fly back to Darwin and then from Darwin back to Sydney. You’d be away a week. Sometimes you would do a couple of flights into Vietnam but the usual program was to fly in once, do all the jobs, fly out and have a lay day and then fly home.

It was full on. I did that a number of times. Then in the beginning of 1971 I was actually sent up to work in Vung Tau with the Caribous, there was only a couple of Radio Technicians doing the job – although when they sent 2 squadron home we got a mate of mine down from there to help out. That allowed me to go off and become an assistant Loadmaster. I’d go as part of the air crew and fly in the dark of the morning and we’d fly home in the afternoon.

You’d seat the passengers, which was a bit like playing hostie, make sure if you had packs that these were tied down or strapped in, help with the cargo - make sure the cargo was safe, refuel the aircraft as we’d be away from the base all day doing short hops from here to forward artillery bases.

You’d take a load on pallets, rolled pallets – in one load you’d take huge cartons of milk, an 8 gallon carton of milk in a placcy bag with a cardboard box around it, to the forward US Army artillery base on the border with Cambodia. So the first load of the day might be milk, you’d then go back to Bien Hoa and the next load you’d pick up would be cordite, the explosive component you needed to fire the shells. So it would be milk-cordite-milk-cordite-general cargo-cordite. You did a number of these ‘frags’, as they were known by, in a day.

You would have to fly into the base between the lulls of the artillery firing. They had a short strip, dirt, an unprepared strip on the top of a hill somewhere – to me these pilots were heroes, what they did and got it right. I think they had a few little mishaps, but mostly they pulled it off successfully.

This, and the life on the base, led me to the point of just how impotent we were; inasmuch as people could lob mortars or rockets into our base, and they did, but would do it at night so you could never find them although you would occasionally find bullet holes in your accommodation but you never saw them; so I went through my tour of Vietnam without firing my weapon in anger.

You were issued a weapon of course, an SLR, when you arrived in country, but you weren’t issued any ammunition.

We lived in a cantonment just off the Air Force base, a double sand-bagged place with towers on each corner that was all lit up at night- so everyone could see you and you couldn’t see them because of the bright lights. We lived in these flimsy ply two storied accommodation huts, open to the air and all else. If a bullet came through it would go straight through one wall, pass through the accommodation area and straight out the other wall and keep going. We were surrounded by overgrown paddies and bush land.

Their thoughts were that if we were ever attacked, and there were a few moments, that you would go to the armoury, where they would set up a desk and hand you out two or three loaded magazines, 20 round magazines, for your weapon. You would sign for 60 odd shells; that you were in receipt of two or three magazines with 20 shells in each. They then wanted them back – if you didn’t use them you had to give them back.

When you returned them they actually emptied the magazines to make sure there were 20 bullets.

Bryan Webster President Palm Beach RSL at 2013 Vietname Veterans (Northern) Service. AJG Picture.

So who was defending the base?

We had a ADGs- Aerodrome Defence Guards, there was a squad of them on call all the time. But even the Guard Towers, you weren’t armed in the Guard Towers…

That must have been frightening..

There were a few times I got shot up – once in the Guard Tower. The thud of a round hitting the sandbags was something, you’d think ‘what the hell was that?’.

In reality you didn’t ever know whether it was a local with a grudge against you or a Vietcong shooting up the base to keep you on your toes. Or it could have just been a US Army guy high on drugs letting off a bit of steam by shooting at the brightest object in his sight, which was our Guard Tower.

Were there any casualties from this?

No, not from that, not while I was there at any rate. You have to remember they kept a lid on everything – you didn’t really know what was going on until afterwards. You didn’t hear of anything – they kept it compartmentalised – it was very rare to hear anything. You saw the odd thing; the squadron leader who was new in country and shared the hangar with us came in and did his route check up to Nui Dat.

On the way a round came through the front of the helicopter and hit him fair in the flak vest. It didn’t penetrate the flak vest but dented it so badly, and the shock that it gave him, it gave him the wobbles, that they flew him back to the base, got him out of the aircraft with a crewman under each shoulder and got him back into the hangar where they got an ambulance from the Army hospital and a couple of days later he was medivac’ed back home; From the shock of it…he was only in country a few days.

What was your most frightening experience while there?

Probably the civilians. You’d go into the local township, it was bigger than a village, and it’s a huge place now; it was alike the French Rivera, a popular bathing spot for the French back in their colonial days.

We’d go into town to have a few drinks. At one stage on the way home, a Tuk-Tuk; a motorbike, raced past us (there were three or four of us in the back of a Tuk-Tuk) and went up to the Tuk-Tuk in front and threw a petrol satchel bomb in and basically it was engulfed in flames. That was frightening.

An American was in it on his own, and I think they targeted the Americans.

The Australians went into town in civilian clothes unless you were on duty, whereas the Americans wore uniform all the time.

Another instance I recall; we were at a bar, there was some unpleasantness at the bar with an American serviceman carrying on a bit. The standing instructions to you, if you were in town in civilians, were to leave the vicinity and to not get involved.

So we left the bar and walked down the pavement to another bar twenty five metres away and drank there instead. We kept an eye on the previous bar and saw the American come out still unhappy with the world and the bar manager.

There were some ‘cowboys’, which are local hoodlums on the back of motorbikes; because they wore cowboy hats, and tended to dress up as cowboys, they were known as ‘cowboys’. They were the local mafia or gangs I suppose. They lived on the back of motorbikes.

At any rate, the American went up and had a discussion with one of these local cowboys out in front of the bar and gave him some money. One of them went into the bar. A few minutes passed and the cowboy came back out and pulled out this huge silver handled handgun, it looked half as big as him, and shot the American dead, put a couple of bullets into him and just dropped him.

He then casually looked around, checked up and down the street, saw us standing there, and honestly my feet were like clay, I could not have moved, ducked, anything.

I thought ‘what the!’ – it was just instantaneous.

He sort of shrugged, jumped on the back of a motorbike and they raced off.

So there weren’t MP’s patrolling these areas?

No. Eventually they would turn up, the white mice, the local police. They were called white mice because they had white gaiters, belts and what have you – at any rate, the white mice turned up.

We vacated the area, we couldn’t do anything, so we left.

We went back a month later and talked to the bar owner and asked what had happened. The bar manager turned around and said ‘silly man, he has fight with me in bar; he go outside and give the local cowboys a hundred dollars US’, or ‘green’ as it was called in those days, ‘he give them a hundred dollar green to come in and kill me. Silly man, why do you think cowboy sit outside my bar? They my protection. I give cowboy one hundred dollar green as well, he go out and kill him.’

At this stage, life was worth one hundred dollars green.

I wonder now why the Americans didn’t subsidise the local cowboys to go out and do their job – it would have been a lot cheaper.

Of course Trevor, my mate with me, and I instantly said “Is our bar bill up to date?”

‘yeah, you boys ok.’

How long were you stationed there?

Nine months. I had to come home in September to get out of the Air Force; I was finishing my last year. I said ‘leave me up there’, I wanted to stay up there…

Why did you want to stay?

Because, the rest of the guys were up there for 12 months, but also because it was an accident that I was there; I was on a list of people to go on tour, but when the end of October came up I said I was going to get out in 12 months, which meant you were taken off the lists of overseas postings. So I fell off the list.

What had happened then though was a chap that had been sent up there only a few months earlier, Phillip, and there was only a couple of us, it was pretty specialised, he got polio, he drank the town water, and ended up paralysed.

Phillip got most of his functions back, but they brought him back. Somebody else was due and so they needed a replacement immediately and so took the first guy off the list and sent him early. Lyndon Johnson his name was, not Lyndon Baines Johnson – he was a lovely little kid, a youngster though. But then I had only just turned 23 myself.

So you were young yourself.

No, I was old compared to the others there, most were 19 or 20. At any rate Lyndon went immediately, and the next guy on the list was actually in Borneo with a Caribou we had doing survey work in Indonesia.

He had just come down with a tropical fungus in his inner ear. They diagnosed that they couldn’t kill it and so he wasn’t allowed to be sent any further north than Sydney in case it flared up again. So he was taken off the list and then another guy, Chris, he’d recently gotten married, and he was with our detachment in New Guinea. We had another three aircraft up there.

Chris had a few problems after marrying, and was hospitalised with severe anxiety. So the list was shrinking fast – I’d been taken off but they said to me ‘Bryan, would you go?’ and I said ‘yes, of course I’d go. That’s what I joined up for, to Serve.’.. and to Serve in a war zone was fine by me.

I was still reasonable gung-ho. They said they’d extend my Service by three years. I said ‘no, just keep me up there until the year is up and I’ll come home.’

They had the ability to do that but persisted in trying to convince me to extend. I explained that I didn’t want to, I’d planned my life, my intentions were to marry my girlfriend when I left the Air Force at the end of my six years in 1971.

I was fed up to the gills with the trivia, the pedantic attitudes, by this stage.

Catch 22 is my favourite book- the movie was horrible, but Catch 22 the book is just delightful; I had used it at one stage.

We got into a situation where we had equipment that we couldn’t get rid of because we didn’t know where it came from, but it was the right sort of equipment for our Herc.s squadron.

The maintenance squadron wouldn’t accept it because the paperwork wasn’t filled out. And we couldn’t fill the paperwork out because we didn’t know where it came from – so it was Catch 22.

One night on Duty Crew, the electronics side of it, I was on my own so I sat there and filled out the correct forms to attach to it and label it, picked one of our aircraft numbers, put the right numbers and what have you and put ‘intermittent operation – requires bench check’.

We didn’t know what was wrong with it – it was three black boxes, that we used, but we couldn’t account for them.

Every morning these would go off to the maintenance squadron but would come back again because no paperwork was attached to them. This time they went off with these pieces of paperwork and labels attached to them and of course they didn’t come back, the maintenance squadron worked on them.

A couple of weeks later the sergeant over there rang up and said ‘can I speak to…’ because I hadn’t signed them off with my name but with ‘LAC Washington Irving’, or ‘Irving Washington’ – I can’t remember which version, but one of those characters from Catch 22 used by ‘Major Major Major’

Oh right; ‘don’t bring anyone in my office to talk to me while I’m here – only when I’m not here’.

Yes, that one. When Major Major Major wanted to get rid of the file that was perpetually circulating, and kept coming back for him to read, he signed it off as ‘Irving Washington’ and then for a joke he turned that around and made it ‘Washington Irving’, which was an American poet of course, and then the orderly clerk eventually got around to considering he was someone outside the loop of which this file was continually passing through the squadron hands of, eventually read this and it had ‘file’ on it so he filed it – he put it away! It finally stopped coming – so since it had worked for Major Major Major he kept using it.

So I too used this, nome de plume if you like, and put down LAC Washington Irving. A couple of weeks later a sergeant at the maintenance squadron rang up and said ‘can I speak to LAC Irving please.’

The boss of our maintenance squadron said ‘there’s no LAC Irving here.’

‘Oh well, it could be ‘Washington’.’

‘No Washington either.’

‘That’s strange, I have some paperwork here and it’s got Washington Irving on it.’

That is getting off the track a bit, but that’s what I did.

The sergeant came over and blamed one of the other Tech.s, a known prank player, so I took him aside and said ‘Roy, it was me and this is why.’

‘Ohhh…you can’t sign fictitious names…oh dear.’

I gave him my copy of Catch 22 and said ‘look, read this and it will explain.’

I’d worked with him before, and he didn’t want to do anything nasty to me, but he felt horrible because of the trivia, the Army and Air Force lived on trivia, there were pedantic attitudes, bureaucracy ruled.

In a matter of days he’d read Catch 22. He said he couldn’t put it down, and he now totally understood my situation, that for months we’d been trying to get rid of this stuff and it was a Catch 22 situation.

He said ‘I’ll sort it out this time, but if it ever happens again, just use that Washington Irving nome de plume and I’ll know what it’s about, and in worst case scenarios I’ll give you a call.’

Well, we had to use it again – and we’d sort it out.

We eventually found out it was an American C141 Starlifter – this was coming in and parked overnight and they have these boxes, and carry their own spares, so if they had a UHF black box that was crook they simply took it off and put it out at the base they were at because they expected the base they were at to fix it and return it to the stockpile. It didn’t matter where it was in the world – could have been at the Philippines or anywhere – but of course we don’t work with that – and it got dropped off to our squadron, we don’t have Starlifters, with no paperwork, no anything – and so the Australian Air Force was up a number of black boxes more then they’re supposed to have.

Yes, so I got myself out of trouble on a number of occasions using Catch 22 techniques.

My squadron nickname in Vietnam was ‘Mr. Fix-it’ – because I’d track down wiring problems in the aircraft (the Caribous), and of course the Caribous were these:

This photo was taken by a friend of mine out the back of another Caribou.

Did you do the extra three months?

No. I stayed at base here and went through expecting to be called up at any time and told I was staying for the whole 12 months. They sent me home to do a couple of weeks on the base and a couple of weeks post-Vietnam leave – you had to do that.

I got on the base, did my leave, got married – two days later.

Where did you get married?

At North Avalon – I think it was a Methodist Minister in a Baptist Church. We had the reception at Avalon Surf Club.

I’d been sending home litre bottles of spirits – Bacardi, Scotch, Bourbon, Vodka. This was 1971 – you got them from the US Army PX (Post Exchange) and would pay US $1.10 for them in those days.

The Iroquois squadron used rocket launchers and these came in foam cartons that were square with a circular hole to fit the missile in. You could chop these into four lengths – generally the bottle fitted perfectly inside with these nice foam protectors – you’d put a bit of cardboard at each end, tape it all up, wrap it in brown paper and send it home – and of course there was no postage. I sent these to my bride-to-be.

After she received a dozen or more of these the post office at Avalon got onto her, or the Customs got on to her and said ‘you should probably be paying Customs Tax on these’. They made her pay $1.50 per bottle – so I was still getting them for $2.50 – while in Australia a bottle of Bacardi would have been selling for $10 or $12 – the 750ml one.

As far as spirits went I finished drinking my spirits from there about five or six years later I’d sent so much home. My trunk that I sent home from Vietnam, I left most of my trashed uniforms up there, they were pretty grotty, was full of spirits too. This came by a Herc. of course, to Richmond Air Force base and I’m glad it was only given a perfunctory once over as if anyone had looked they would have been horrified.

I came home, got married, had two weeks off. Went back to work, sorted out problems with the secondary radar systems that I’d set up before I went away, they’d left all the problems for me – all the black boxes that were unserviceable; ‘US’ .

I went to them and said ‘why didn’t you leave me up there?’ – as the aircraft were due home by Christmas, and actually came back the beginning of February ’72, - they had the facility to do this – there was a special group of people called the ‘AEF – Air Emergency Force’, - he explained ‘no, we couldn’t enrol you in that because there was no application form to join – you have to be appointed to it’ – this was based upon your usefulness and whether you’re a good guy – there was certain criteria, only a certain amount of people were appointed to it because there was a monetary value involved as well as anything else And if they use you there’s a high risk involved too.

On the day I left the Air Force, I was signing all my forms, and the Orderly Room clerk said ‘you don’t need to sign for the Reserves, you’ve been appointed to the Air Emergency Force.’

I said, ‘but I’m back here now.’ – ‘yes, that’s a pity. Well, don’t unpack your bags.’

So I waited for the next month to see if they were going to call me up and send me back up there, but it never happened.

So I got ordered to go to Vietnam because I wouldn’t sign for an extension and had less then 12 months to go; I was one of the few Air Force people, certainly in my mustering, that wanted to go, you wanted to prove yourself, but was eventually ordered to go because I couldn’t volunteer – I wasn’t allowed to volunteer despite saying ‘I’m quite happy to go.’ – ‘yes, but that’s that form’ – Catch 22 again!

It was a bureaucratic nightmare – I love the Air Force and have recommended other people join, certainly if they want a career this is the place to go but some of the aspects of it….goodness.

I was lucky that I came back to a loving wife, my own family and her family, her father had served in the Air Force in the islands in WWII, so he was a Vet., and he understood what it was all about – so I came home to loving families, the surf club was fabulous – the surf club had provided a number of people to the armed services, particularly the Air Force at Whale Beach SLSC, and they just accepted you.

So you didn’t experience the cold shoulder and vilification so many other Vietnam Veterans did?

In other areas I did – at the RSL clubs, in certain public people, and I was aghast at the Press and the politicians of the day, at how back stabbing some of them were. It got to you; after I got back it got to me, more so then when I was up there.

But my wife was 5 foot 11, a PE teacher, and she told me to suck it in; ‘get on with it’. She was a fabulous person, if I ever felt stressed by it, and I was occasionally distressed by what was happening, I found that I had support. I had a good network.

I didn’t March anywhere until the 1980’s. I went in one March before the Coming Home March - I met up with blokes from my squadron I hadn’t seen in a decade. I remember this big tall bloke, ‘Flash Harry’ we called him – I turned to him at one stage after the March, we were having a drink and this would have been the August or September, and said to him ‘are you going to come to the March?’ (the next one – for Vietnam Veterans – the Coming Home) , and he’d been like me, he hadn’t Marched – I said ‘we should do it for our friends and colleagues who either didn’t come back, or those that came back with a problem – not like you or me.’

Harry said ‘speak for yourself’

I replied ‘come on mate’ – he was this huge hulk of a man – ‘we’ve got all our fingers and toes.’

He looked at me and said, ‘did you come back an alcoholic?’

I said, ‘no, we all drank while we were up there, but I went back to being a two pot screamer soon after my return.’

He said he came back an alcoholic, he couldn’t stop drinking. His wife left him – when he got home he found his wife had had an affair and left him, but she waited until he came back to tell him, she took the kids and left him. He drank too much, he couldn’t stop drinking. He had obviously signed on again deciding to make the Air Force his career, and the Air Force then threw him out, because in those days they didn’t have a programme to actually realise there’s a problem, so they wiped their hands of him.

So he lost everything?

He lost everything. It was ten years on when he and I were doing a March for the first time, and I hadn’t seen him since ’71. He had spent all of his time getting his life back together and he was only just now able to have a drink and keep it to just one or two drinks and then stop.

I was about to say ‘we all drank’ but luckily stopped myself and listened to his story. I realised how absolutely lucky I was to come back to enough of a support group to protect me.

Things went off the rails a bit for me when my wife passed away – that caused problems because there went my support crutch. I had someone to support me if I was angry at the media – I’m angry at the media at present because of the way the Iran business is unfolding – I saw this happening again and went off the rails so to speak. I thought ‘not again – what is your exit strategy’ – I get emotionally distressed when I see anything to do with death and destruction.

I can’t go to funerals – I’ve done a funeral service, the RSL Service, and I found that it was just so traumatic for me that I couldn’t do it again.

I don’t go to anyone’s funerals. I’m not going to mine…

You’re not going to your own funeral Bryan? Going to absent yourself – AWOL?

Yep, not going to mine. Going AWOL

That’ll be a first – I’m going to cover that story.

We did one for Hal Bailey – remember Hal?

Yes. Wonderful man.

We did Hal’s Service in the RSL club. He wasn’t anti-religious but was ambivalent about the whole thing. His wife Betty came to us and said Hal wanted to have it done at the RSL. So we traipsed his coffin in, had the Funeral Director there, put up a bier with the flowers on it, had the Service and Oratory in the auditorium. It was chock’a’block – you couldn’t move. It was a great service – people spoke from and about different parts of his life, a lot of it was surf club – I spoke for my generation that knew Hal, someone spoke for the generation down from him – it was absolutely fabulous – he was not only a great bloke, he was an inspiration, and if anything, that would be the way I’d go.

We did a service for Lindy on the beach at Whaley at six o’clock one Sunday morning. It was in October so the sun was just getting up, that was when she ran the beach before she went to work. We had a few complaints from people, ‘oh, we’ve got to travel’, but that was what time she’d run the beach, so be there. We had 750 people there, that was good.

How did you meet Lindy?

Moby Dicks – remember Mobys?

Of course.

One of my best friends in the surf club, a bloke I was best man for, Pete, he lived up at West Pennant Hills then. We were 21 year olds and had been doing lifeguarding work during the week, living in the surf club, I was on leave from the Air Force and he was on leave from Telecom (now Telstra) and we’d put the bins out for the kitchen twice a week. For that we got a free meal each every night of the week. We had to eat near the kitchen though, not in the dining room.

If we missed a night and told the chef in advance we could have four meals the next night. So Peter invited a couple of girls out, including Lindy. We both had new cars – he came and told me this when he was intoxicated, I was a little too and hanging off a poker machine there at Moby’s – I was on a winning streak on one of these one armed bandits, and I said ‘yeah, yeah – whatever Pete’.

A little later I felt these eyes staring into my back – one was five foot nothing, and the other is almost six foot tall. Pete is about five foot six at best – so I thought obviously Pete is taking out the shorter one, and the other is six inches taller than me – at any rate they were ‘not impressed – we’re going out to dinner with you in a few days time’ – I was burbling, hopeless.

At any rate, we went down to pick them up a few days later down the back of Avalon Primary School, in Bellevue avenue, the house was resumed eventually and is now a playground. I had a V8 GTS Monaro, brand new, and if you remember these you’ll recall they had one door and these doors were huge. We got down there after Peter and I had been roaring around for a bit and then roared up there – the girls came out and we went in and said hello to the parents Wally and Mary, that sort of thing, and out they came. I went around to the driver’s door and jumped in. Peter went around to the passenger’s door, flipped the seat forward and ushered both girls into the back seat - he was shotgun you know, he’s not giving up his seat for anything. He pulled the seat to and at that stage I was still trying to figure out which girl I’m with…

We roared off to Moby’s and had these four free meals, not that we told the girls that by the way, and when they suggested Sweets, we were a little bit ‘oh, oh, oh – no we don’t do Sweets.’

We had a good time, danced and all that. We had parked down in front of the Surf Club and went down the stairs, Peter swings the door open, and I went around to the driver’s side, still not sure who’s who in the zoo, and Peter ushered Leigh, the shorter girl in, and then Lindy got behind Peter and pushed him into the back seat, swung the seat back in place, jumped in, looked at me and said ‘I’m not sitting in the back seat of this car ever again.’

I said ‘that’s fine by me.’

I said ‘that’s fine by me.’

I started taking her out, going for a drive. That was Christmas 1968, early 1969. I took her out for a couple of years during her teacher training. Her training was done down at Wollongong for three years. At the end of 1970 she graduated and applied for Richmond High, Windsor High or Northern Beaches. Her parents were still down at Avalon at that stage, and later moved up to Rayner Road, Whale Beach.

She got Windsor High – a week later I got my marching orders to Vietnam. She taught there through until the end of 1976. We moved into the servants quarters of Fairfield House, which sits on a golf course overlooking the Air Force base. The stairs were almost vertical, very narrow.

Right: Fairfield House at Windsor has been renovated since this photo - and is now a Wedding reception venue.

Let’s talk about rugby for a moment – a few little birds told us you did very well there. Who were you playing with?

I played with Cammeray/Northbridge and Whale Beach Surf Club.

Whale Beach Surf Club had a rugby team?

Whale Beach Surf Club won the inaugural Barraclough Cup. The Barraclough Cup in those days was for one team clubs. All of Whale Beach’s players used to play from Cammeray/Northbridge but we had enough for one team – so we seceded from Cammeray/North’s and created Whale Beach Surf Club and played in the inaugural Barraclough Cup Competition and won. This was 1969.

The inaugural cup is actually hidden somewhere in Moby’s still. It was on the wall in Moby’s – it might be in the storeroom there after the renovations.

That’s a story in itself.

Yes, we should run a page on that.

When I was in the Air Force at Richmond I found I couldn’t train and so ended up going back to Cammeray/Northbridge – not that Whale Beach trained a lot, but that’s another story.

I ended up captaining a team from Cammeray/Northbridge that knocked Whale Beach out in a semi-final, and I kicked the goal that did it …

Very very naughty…

While I was playing for Cammeray/Norths and my brothers were playing for Cammeray/Norths, my cousins were playing for Cammeray/Norths, my dad came along and started his rugby career at the age of 57. He had played some league as a young man. He took up playing rugby, in the bottom grade obviously, but he was so strong, a big solid upper body strength, he was huge, and was fabulous even in his late 50’s.

He played through into his 60’s, and then they wouldn’t play him anymore once he hit his 60’s, they refused to register him as a player. In 1971 he moved to Newport to the Breakers. He was the original wrinkled rat – no fear or favour or any golden oldies rules applied with him being over 60, he was full on. He didn’t drink, he didn’t smoke, he had seven children - there’s a lesson to be learned there.

He was regarded as a fabulous old bloke and when I came back out of the Air Force I got to play with him at Newport.

I played for a few years when I was stationed down in Victoria too – that was a great social club part of life there. It was hard going and a very serious competition but they were geared to be social. It never got warm there, so there was great ‘socialising’.

So I joined Newport to look after dad and played with them right through the 1970’s into the early ’80s. He finally gave up when he was 67.

He must have been the oldest player?

I think he may have been in those days. There were photos of him in the clubhouse, some write ups in the Daily Mirror, ‘Still Going Strong’ – there was a lovely shot of him passing the ball to me – it makes me look bigger than him, and I was an inch or two taller, but back then I always had to stand up tall because Lindy was five foot 11 – I was on my toes all the time.

I had mutton chops in this picture, long flowing locks and mutton chops, and a mo’. I think it was a rebellion against the short back and sides of the Air Force.

Seeing that shot made me decide to have a haircut though.

What did you go into once you left the Air Force?

When you were leaving the Air Force you sent out a shotgun resume to all the prospective employers, which was in the electronics world for me, which I did. Due to being overseas I did this quite late, practically with only days to go.

So I surfed at Whale Beach for a little while and then Vic Withers, who was managing Moby’s and did for many years, caught me laying about the beach mid-week and he needed a mid-week daytime barman. I had no experience apart from pouring a beer out of a keg, so he knew I could pour a beer properly- you never wasted a drop when you were in a drop when you were in a Surf Club, and ended up becoming a barman for Moby’s. That warped into a bit of weekend work where I became the Wine Waiter and because of my parents and grandparents, everyone in Moby’s on Saturday nights knew Jack or Pop, would say hello and ‘how’s dad’ that kind of thing, I became very popular although I knew nothing about wines. People would ask for my recommendation and I would base my suggestion on value; if it was valuable on the Wine Menu then it must be good. I’d say ‘they’re all good, that one is the best’.

The number if people that actually took the most expensive – Moby’s was fabulous in those days, Saturday nights.

Then one of my shotguns came home to roost. I became a Technical Officer for a big Australian company, Oberton and Frankie, in their technical area testing and importing and training people from overseas – I became an Office Manager and their technical adviser.

I did some work for them on some advertising material and they promoted me to National Advertising Manager. This entailed mainly proof reading all the different divisions – they went from electric motors to a division such as Makita Power tools, that was one of theirs, they had a number of different agencies they brought in. I would proof read their ads and make suggestions. I excelled at that for some reason and it became a bigger position, a growth position.

I did some work for them on some advertising material and they promoted me to National Advertising Manager. This entailed mainly proof reading all the different divisions – they went from electric motors to a division such as Makita Power tools, that was one of theirs, they had a number of different agencies they brought in. I would proof read their ads and make suggestions. I excelled at that for some reason and it became a bigger position, a growth position.

After nine years I left them and went into Biomedical Engineering for a while. From there, and a couple of kids later, I joined the government for ten years.

I initially started off as the buyer of audio-visual goods for the NSW government, setting up common use contracts, doing tenders for the contracts. I became the boss of my little buying group, for electronics and office equipment. I was successful at that, had my people working to time, so they added another buying group to mine, so I then had a dozen or more contract officers working for me.

A that stage I’d sat in the boss’s job and realised you had to be a real bastard to be in the next up job. All you would be looking at was deadlines, you didn’t care about people anymore. I was a people person and knew that wouldn’t suit.

Being the natural inheritor of the job above me, and he did move on, I knew I couldn’t do it.

I joined Samsung instead – they head-hunted me to become their government manager. With them I was doing the government contracts right around Australia. I was there for 13 years – I started in 1994 until 2007.

I retired from them. Post Lindy passing away I found I was having problems – I was faced with two teenagers at school, one was just finishing Year 12 and the other was finishing Year 9. Naturally I focused on their lives and work suffered to some extent. I found I was becoming testy with particularly the Koreans at Samsung – whether there was a hangover from them being Asian or not, I don’t know – but I no longer had the support of Lindy to keep me on the straight and narrow, and would get into heated arguments with some of the Koreans, some of whom I liked enormously, admired, respected.

I found myself getting worse and worse and saw this as the writing on the wall; I wasn’t coping very well. I realised there were some underlying problems, that my lifestyle was deteriorating. So I went and got a bit of help, Veteran’s Affairs were very very good, they arranged counselling for me.

I realised my time had come, I was 59 and a half then and that at 60 I could go with the Service Pension. I paid off all my debts, pulled the pin and focused on looking after my kids.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater and why?

Whale Beach obviously. Why?; because, apart from the aesthetic beauty of it, even though it has been built out to some extent, apart from my memories of it and the community relationships that we’ve developed over the years both at a Surf Club level and more recently with the community at large, it is that there are a number of wonderful people, giving people, not only my neighbours but from the hillside generally, who have astounded me with their generous natures. Their support for the Surf Club, their help with the Big Swim – they’ve given their time, they’ve given their money and their support.

I love the whole of the peninsula, but I love Whale Beach in particular.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to love by?

Catch 22!

Life’s a matter of giving, not expecting thanks or reward.

It took me years to realise this – years before I saw both my kids have Master’s degrees and were in stable relationships. I hadn’t had a holiday in ten years, I’d focussed on their lives and suddenly here they were. I don’t regret any of that at all as both my kids have developed into wonderful human beings. They’re both giving individuals as well.

So to me it’s better to give, and not expect a pat on the back for it.

Panorama of Whale Beach no. 1 - (and blown up section from below), New South Wales between 1917 and 1946. Part of Enemark collection of panoramic photographs by EB Studios (Sydney, N.S.W.). Image No.: nla.pic-vn6152463, courtesy National Library of Australia.

Panorama of Whale Beach no. 4 - (and blown up section from below), New South Wales between 1917 and 1946. Part of Enemark collection of panoramic photographs by EB Studios (Sydney, N.S.W.). Image No.: nla.pic-vn6152465, courtesy National Library of Australia.

Extras:

Vũng Tàu is a seaside city of Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province in Southern Vietnam. During the Vietnam War, the 1st Australian Logistics Support Group was headquartered in Vũng Tàu – as were various United States military units at different times. Vũng Tàu also became popular for R&R, amongst in-country US personnel.

Vũng Tàu is mentioned in "I Was Only Nineteen", the #1 single by Australian folk rock band Redgum about the Vietnam War from the 1983 album Caught in the Act. The 1979 Australian film The Odd Angry Shot contains a sequence in which the protagonists go on leave in Vũng Tàu. The Vũng Tàu sequence also shows US troops, taking R & R, being swindled.

RAAF Transport Flight Vietnam – later No. 35 Squadron – was the first Air Force unit in Vietnam in August 1964 and the last out in February 1972. During almost eight years of service, the Squadron developed special tactics to beat enemy fire, its personnel were recognised with awards and, most remarkably, no members were killed. Their story is recalled here in the lead up to the 40th anniversary of the deployment.

Air Force personnel and a Hercules flypast join veterans to commemorate 50 years since deployment to Vietnam War

Air Force personnel from RAAF Base Richmond will join their veteran counterparts in Coffs Harbour from Friday-Sunday, 8-10 August, 2014, to mark the 50th anniversary of the RAAF deploying to the Vietnam War.

At 2:30pm on Saturday, 9 August, a Hercules will fly from north-to-south over Opal Cove Beach at a height of 75 metres, then conduct a second flypast with its landing gear down and cargo ramp opened.

On 8 August 1964, the RAAF Transport Flight Vietnam (RTFV) was formed at Vung Tau Air Base in South Vietnam, with three DHC-4 Caribou transport aircraft.

From August 1964 to February 1972, the RTFV would expand to six Caribou, and would be reformed as No. 35 Squadron.

The RAAF also deployed Canberra bombers and Iroquois helicopters; as well as operational planners and support personnel, and a number of pilots on exchange with the United States Air Force.

At its peak, RAAF had 750 personnel deployed in the Vietnam War, and suffered 14 casualties, five of these during combat.

The reunion in Coffs Harbour is being coordinated by the No. 35 Squadron Association, which includes veteran members of the Vietnam War. They will be joined there by current Air Force personnel, including members of the present-day No. 35 Squadron from RAAF Base Richmond.

Wing Commander Bradley Clarke is Commanding Officer of No. 35 Squadron, and said he was honoured to join the veterans for the reunion.

“No. 35 Squadron has a 72-year history, and its service in Vietnam is an extremely important part of our unit’s identity,” Wing Commander Clarke said.

“It was during this conflict that the squadron’s nickname, ‘Wallaby Airlines’, was forged, with RAAF Caribou in Vietnam flying 81,500 operational sorties.”

“They carried 42,000 tons of cargo, and 679,000 passengers, leading Americans to believe the RAAF had more Caribou in Vietnam than we really did.”

“The current generation of No. 35 Squadron is extremely proud of the contribution made by our veteran members, and we’re looking forward to joining them in Coffs Harbour,” he said.

RAAF Base Richmond was an important part of Air Force’s role in the Vietnam War. The base supported the DHC-4 Caribou which flew missions in South Vietnam, and was also home to the C-130 Hercules which transported equipment and personnel from Australia.

The Hercules were also configured to carry casualties on aero-medical evacuation missions, which saw RAAF medical crews care for wounded during 14-hour non-stop flights from Vung Tau to Richmond.

_________________________________

Awards for actions

THE first awards for operational service in Vietnam were three Mentions in Dispatches in August 1965 for courage under fire or the threat of fire in support of operational forces.

The awards went to:

• Flight Lieutenant Ronald Raymond, a pilot who participated in night flare dropping missions;

• Leading Aircraftman Daniel Gwin, a loadmaster, for accurate return fire on a mission; and

• Corporal Robert Wark, a member of the repair party that retrieved a damaged Caribou in November 1964 when under nightly ground fire and attack by Viet Cong.

Squadron Leader Christopher Sugden was awarded a Bar to go with his DFC in December 1965. And in 1972, Squadron Leader Stanley Clark, CO of 35SQN from November 1970 to November 1971, received a DFC.

Another possible record for RTFV/35SQN – during the deployment, not one man was killed.

RAAF A4 DHC 4 Caribou crews return to Vung Tau, date and time unknown. With aircraft A4-171 in the background and pilot third right (carrying bag in left hand) is Flying Officer Jan Staal. © Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Defence

A formation of seven RAAF A4 DHC 4 Caribous approaches Vung Tau, South Vietnam, 1970. © Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Defence