January 6 - 12, 2013: Issue 92

Canoe and I go with the Mosquito Fleet.

Being desirous of winding up a pleasant cruise on the upper reaches of the Hawkesbury and McDonald Rivers with a sail round the coast to Sydney, we-that is to say, the 14ft canoe Golden Butterfly and her skipper-parted company with our companions, the Cissie and Gaiety Girl, at Peat's Ferry, where the magnificently ugly railway bridge spans the wide river. Setting sail at about 4 p.m. on the 18th instant, we shape a course for Barrenjoey, the bold- light-crowned bluff that stands, sentinel-like, at the southern side of the entrance to Broken Bay, a harbor little behind Port Jackson in capacity, depth of water, and other advantages.

Clearing the kerosene-tin lined and old-bucket beaconed channel that leads through the mudflats to Brooklyn, another of the designations which the bad taste of the official sponsors, sufficiently advertised already over the whole of the colony, has added to a village with as many names as houses, we and that a strong, adverse tide and lumpy water make progress unpleasantly wet and tardy. The freshening north-easter, almost dead in our teeth, coupled with the carrying away of a yoke-line, in a place awkward to repair efficiently while afloat, breaks us considerably off our proper course, and we only fetch Little Pittwater, an inlet near the mouth of Cowan Creek, one of the principal arms on the southern side of Broken Bay.

Having no time to lose in order to reach Barrenjoey before nightfall, we here stowed the main-sail and took to the paddle. Although sadly tempted to tarry a while and flesh our maiden oyster knife on the immense deposits of fine bivalves with which the tide-exposed rocks were thickly covered, we resisted the temptation, and, pushing along vigorously under the lea of the land, made good progress, passing one or two sheltered coves, in one of which a party of aquatic holiday makers were snugly camped. Out in the open water several "school sharks" and sea-salmon were leaping and playing around, throwing themselves occasionally several feet out of the water, their quivering lengths glistening in the sunlight, the splash of their heavy fall dashing up a shower of spray being audible at a considerable distance.

Away to the northward, paddling feebly, and with much groaning, to comparatively little progress, on her return trip up river, we recognized poor old Utility, the ancient little ferry-boat that used to ply across Darling Harbor to Pyrmont. She is now a travelling store or hawking boat, and has been rechristened the Emporium.

Rounding the false headland which, until now, had screened the outer harbor and light station from our view, we encounter the full strength of tide, wind, and sea, the long swell swinging in from the Pacific unchecked or broken.

It had been already a fairly long day, our last camping-place being a little below Wiseman’s Ferry, some five-and-thirty miles up the river; but her three formidable opponents tackled the Butterfly in vain, for, wielding the double-bladed paddle for all we were worth, she had gained at sunset the shelter of Pittwater, wherein three or four wind-bound coasters were snugly moored.

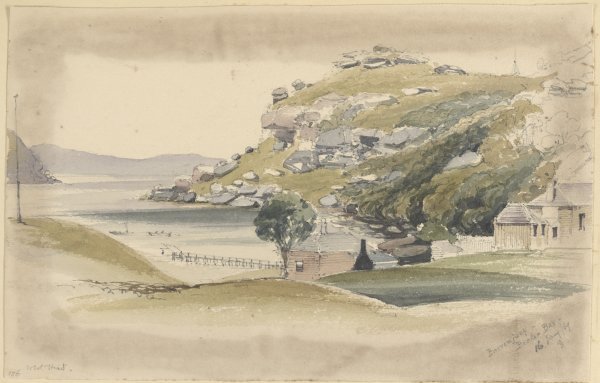

Barrenjuey [i.e. Barrenjoey], Broken Bay [picture]. 1869 Jan. 16. by George Penkivil Slade, 1832-1896. nla.pic-an6454687 courtesy National Library of Australia

Right ahead, a mile or so distant, the rugged headland of Barrenjoey reared itself at the end of a long, high sandpit, connecting it with the elevated timber coastland to the southward; the lofty lighthouse and its substantial outbuildings arising prominently from its scrub-covered summit; while at the foot, behind a pretty little arc of sand beach, enclosed by the rocky promontory and a fine jetty, the cottages of the Customs officer and his boatmen snugly nestle in a bower of varied foliage.

On beaching the Butterfly we are made welcome by Captain Champion and his crew, who assist us in carrying the little craft up on to a grassy flat above high-water mark, and the last few minutes of the waning daylight are occupied in making final preparations for the voyage, such as utting reef earrings to the sails, splicing the broken yoke-line, and sharpening a lance kindly contributed by a Brooklyn boatbuilder. This deadly weapon was ingeniously contrived from a shear blade securely seized to a short bamboo shaft, and, effectively administered, it would not doubt have considerably impaired the digestion of any shark who seriously contemplated a change of diet.

Not that its use, save as a last resource, would have been judicious, as the "tiger of the deep" is easily provoked, and it would take more than a buttonhole in his waistcoat to incapacitate or deter him from his purpose once he was fairly "on the job."

As an unpleasant matter of fact, a really hungry shark is a source of far more danger to the experienced canoeist than a gale of wind, as he is almost entirely at the mercy of the voracious creature, who can unship him by merely rubbing against the keel of his comparatively narrow and unstable craft, or chew an end off her at a mouthful.

It was hardly encouraging to learn that not long previously, at this very place, a large, heavily-built fishing boat had had her side stove in, and was with difficulty saved from foundering, by the foiled rush of a big "blue pointer," who was endeavoring to seize a hooked schnapper that was being hauled in ; and that shortly before this one of the boatmen who had been spearing salmon from a 20ft boat found it desirable to throw overboard his fish, in order to divert the too pressing attention of one "Billy," a Colossus among the carcharidae, who was a well-known and much-respected inhabitant of the local waters.

After stowing away an ample and well-earned meal, enlivened by the discourse of some of the youngest inhabitants, we decided to refrain from our usual custom of sleeping afloat, in order to give our friend Billy no more opportunities than were absolutely unavoidable. So we made a bed for the canoe of dried seaweed, and rigging the hard-weather tent, which also does as an apron, over the open well, made all snug for the night.

Before turning in we-that is to say, the skipper-tempted by the fineness of the night, and the companionship of one of the local "waits," who regaled us with more exhilarating yarns about "Billy," indulged in a ramble on the jetty.

The scene was beautiful and impressive. Away overhead, through the starry night, streamed the ruby glare of the landward face of the light; while at several points the distant wooded eminences inland were girdled with bush fires, fanned by the fresh north-easter, which every now and then, as some inflammable bush or tree was caught within the embrace of the glowing circles, flared up like beacons, almost quenching the faint light of the young moon, already veiled by the smoke clouds which swept the western sky.

The dull booming of the long ocean rollers dashing themselves in endless succession against the foot of the lofty cliff and the steep beach without, was mingled with and made more nieloaious by the rhythmic Bong of the tiny surges that rippled along the margin, of the sand and shingle, and the rustling murmur of the trees.

The dark water at our feet was frequently illuminated with streaks and crescents of phosphorescent light, as its numerous finny denizens darted hither and thither, in their various quests and pursuits.

Acting upon good advice, "all hands" were called at the earliest flush of dawn, and in a very short time the little craft was again afloat, with stores and ballast aboard, and in good sea-going trim.

The light north-wester then blowing being too much ahead just at first for us to lie our course under sail, and it being cool enough to make brisk exercise desirable, we paddled out of the littlehaven and round the rocky base of the headland.

The Venus, a little ketch in the firewood trade, was also getting under weigh, bound south, so we hoped for company; but, alas! the goddess' sunflattering namesake, which, judging from appearances, was christened "sarcastic," did not walk the water like Amphitrite of old, and all we subsequently saw of her was her dingy old patched mainsail diminishing to a mere speck astern.

Running out with the full strength of the ebb-tide, we soon cleared the rock-girt headland and gained open water, setting sail on our course to a light, fair wind, over the starboard quarter.

The sea having still a considerable "swing" on, and there being a lively "hobble," due to the rocky bottom underneath, the light canoe was tossed about like a cork in a decidedly un-pleasant manner, making at first little headway; as the breeze barely sufficed to keep the sails from flapping, we again took to the paddle, making fair headway along the broken coastline.

Occasionally we were

visited by a "sooty gull" which came sweeping in graceful curves, skimming over

the heaving billows like an animated boomerang. To seaward nothing else was in

sight save, far away in the oiling, sharply outlined against the brightening

morning sky, a little barque in tow of a three-masted screw steamer, which, as

well as we could make out without a glass, were two of Sydney oldest marine

identities, that have survived alike the perils of the sea, the decaying touch

of time, and the ruthless march of improvement-the Fanny Fisher, (left)

built here half a century ago to fetch grain from South America to the almost

starving settlers, and the Saxonia, in her day a crack intercolonial

mailboat. Now both were bound for Newcastle to load black diamonds. How have the

mighty fallen!

Occasionally we were

visited by a "sooty gull" which came sweeping in graceful curves, skimming over

the heaving billows like an animated boomerang. To seaward nothing else was in

sight save, far away in the oiling, sharply outlined against the brightening

morning sky, a little barque in tow of a three-masted screw steamer, which, as

well as we could make out without a glass, were two of Sydney oldest marine

identities, that have survived alike the perils of the sea, the decaying touch

of time, and the ruthless march of improvement-the Fanny Fisher, (left)

built here half a century ago to fetch grain from South America to the almost

starving settlers, and the Saxonia, in her day a crack intercolonial

mailboat. Now both were bound for Newcastle to load black diamonds. How have the

mighty fallen!

While passing the second promontory the golden arc of old Sol flamed with a sudden brightness above the rugged, undulating horizon, his beams gilding their wide pathway over the cold, steel grey waves, and transforming the face of nature almost with the celerity of a harlequin's wand, painting the sombre foliage with verdant hues; warming the hitherto monotoned sandstone cliffs with many a weather stained tint; while the foam fringed beaches were lit up with a brightness feebly rivalled by ivory set in diamonds, and every wave was decked with flashing gems. As the uneasy motion of our little vessel suggested the possibility of our having, perhaps, to make an unwilling sacrifice to Neptune, and knowing, from experience, that any neglect to lay in the necessary provision adds to the unpleasantness of the objectionable rite, we got out the tuckerbox, and, all things considering, succeeded in surrounding a very satisfactory meal. On the accomplishment of this feat we were rewarded by a more northerly shift of the wind, which, with added weight in it, rendered the galley slave business unnecessary, and not only made the Butterfly flit along at a considerably increased speed, but checked in great measure her uneasy jerking motion.

By-and-bye the wind settled into its regular quarter, the north-east, and slipping merrily along, the coastal panorama unrolled itself, revealing many familiar objects and localities.

Here and there the old Pittwater-road was to be seen winding its way, like a white thread, among the scrubby sandhills, past grassy knolls and over steep, wooded ridges. Now, just abeam, the prettily-situated buildings of a long defunct powder manufacturing company, the ornate residence of the manager being very conspicuous, show plainly, away back among the dark hills. A little further and we pass a cottage perched high on the hillside, wherein we had spent many a pleasant hour in the days that were. Soon we are abreast of the low sand-choked entrance of Lake Narrabeen, where-how many years ago?-we had spent a pleasant canoeing holiday, in company with a younger brother, now some-where in the interior of the "dark continent." The old Rock Lily Hotel and a more pretentious modern structure are also visible, and one who knows where to look can make out, on a verdant slope overlooking the beautiful little lake, the site of one of the earliest settler's homestead, the scene of an awful bushranging tragedy in the early days. Away ahead the Dee-Why Lagoon, with its reedy marshes, at one time the haunt of many wild fowl, lies just behind the low sandhills.

While off Narrabeen we are passed quite closely to starboard by a small green screw steamer, which did not appear to have her name painted in the usual place, probably because she was bound for Gosford and Brisbane Water. The crew, who were evidently surprised to see so small a canoe at sea, applauded us vigorously, and shouted, "Go it, old man!" "Good luck to you!" and other cheering injunctions; while a solitary lady passenger waved her lily-white hand encouragingly. She-I mean the steamer-looked very pretty, dipping her head deep into the rollers, and flinging the creamy surges off either bow.

Passing Long Reef, on which the sea was breaking heavily, the breeze began to freshen, and by the time the Curl Curl Head was abeam the waves were beginning to show an occasional bréale, which suggested the desirability of gaining some more offing, in order, should the weather freshen, to be able to tip the combers "the stern" without getting too close to the coast, and sacrificing the sea room necessary for safety.

The northern sky was streaked with "mares' tails," and there was every indication of the "blow" which, at the time of writing this little narrative, is still making things very lively for anything afloat. However, with such a short distance still to run, there was no need of apprehension, as only a stiff southerly could have now made our making Port Jackson at all doubtful.

Continuing to make good progress, we slip past "The Village" and Fairy Bower, the scene of the last boating fatality, and are about abreast of the Catholic College on Manly Heights, a prominent landmark for a considerable distance along the northern coast, when we are passed to seaward by one of the most peculiar craft that hails from Sydney. She was a large, flat-bottomed, twin-screw scow, with a lofty mast stepped well forward. Considering the comparatively light wind and sea, she did not appear to be making very good weather of it, and rolled heavily, at times showing a good third "of her length out, of the water as she wallowed over the waves; kicking up more "bobbery" than an ocean liner. Experiences of long ago, however, as "mate" of a very similar craft on the coast of North Queensland and New Guinea convinces us that they are much better sea boats than they look, and very suitable for bar harbors and shallow estuaries.

There is no lack of company for us now. Several fishing boats are beating up to their fishing grounds, and as they are lifted on the crest of the following sea we note their crews taking stock of us. A coastal schooner also, looking pretty enough at a distance, is standing out close-hauled under full sail, and away in the offing are the smoke "trails" of a steamer or two making up and dawn the coast.

And so we run past the precipitous North Point and the Tumbledown, close under the cliff; indeed, rather too close, as the breeze is here very fluky, and the sea breaks occasionally. Luffing round North Head, we are met with some very hot, baffling puffs, that render it necessary to "get out" on the gunnel smartly, and "sit her" while they last, the more so as we have somewhat prematurely "jettisoned" our extra sand ballast, in order to lighten the canoe for running.

Entering the Harbor, we pass more sailing boats, "outward bound," and exchange greetings with an acquaintance piscatorially bent.

Weathering the South Head, and rejoicing in smooth water and all the wind required, we run up the Harbor like a steamer before the now stiff north-easter, and finally, at about 10.30 a.m., bringing up at the club shed in Lavender Bay, where we duly report ourselves, terminate a highly enjoyable and successful cruise.

"Golden Butterfly."

Canoe and I. (1896, January 18). Australian Town and Country Journal (NSW : 1870 - 1907), p. 42. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71240609