November 15 - 21, 2015: Issue 240

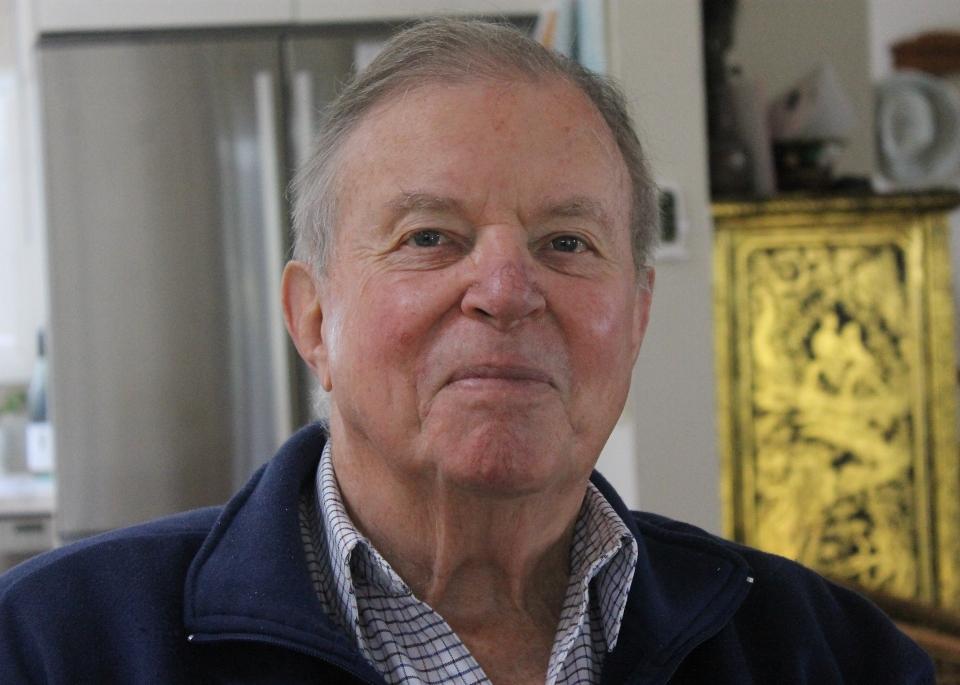

Christopher Chubb

Pittwater gentleman Christopher Chubb has lived through experiences many can only imagine. Born in the late 1930's in Hong Kong, he was a child when The Battle of Hong Kong (8–25 December 1941), also known as the Defence of Hong Kong and the Fall of Hong Kong, took place.

This was one of the first battles of the Pacific campaign of World War II and occurred on the same morning as the attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. The forces of the Empire of Japan attacked British Hong Kong, in violation of international law as Japan had not declared war against the British Empire. Japan's forces were met with stiff resistance from Hong Kong's garrison, composed of local troops as well as British, Canadian and Indian units. Within a week the defenders had abandoned the mainland, and less than two weeks after this, with their position on the island untenable, the colony surrendered.

As a survivor of a World War II Internment Camp, Mr. Chubb subsequently went on to Serve as a National Serviceman during the Malayan Emergency as part of one of the world’s oldest Regiments, the King’s Dragoon Guards, rising to the rank of Lieutenant.

A successful career in banking followed where Mr. Chubb was posted throughout Asia.

Where and when were you born?

In Hong Kong in 1937.

Were you still there when Hong Kong fell?

Yes. We, my mother, father and myself, were placed in an Internment Camp, Stanley, at the southern end of the Hong Kong peninsula. We were there for the duration of World War II. Some people were fortunate to get out prior to the capitulation – you had to have money to get out and to be able to support yourself elsewhere, whichever country you got to. In the camp the form of money was IOU’s which you honoured after the war.

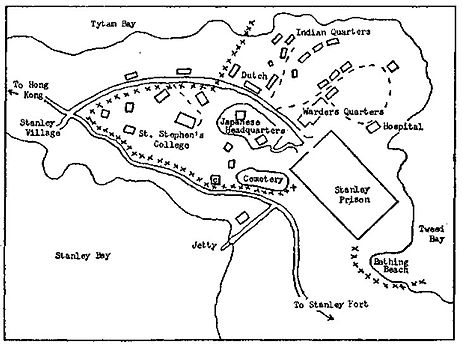

This map, which I don’t think is quite accurate, shows the layout of the camp. Block 14, where we were, was not like that, so somebody has drawn this up from memory. As a child we got a pretty good idea as to where things were, we used to roam around there, everyday.

We lived in this block here on the right hand side down the bottom, in a single room, all three of us. We were better off than people here who were crowded in, three to four families per flat. There were around 3000 people altogether at the camp, mainly British people.

There were people killed there by the Japanese but I didn’t witness any of that fortunately.

This map shows St Stephen’s College – where there was a massacre. The Japanese soldiers rounded everybody up, and killed all the soldiers, nurses and doctors on Christmas Day 1941*. This was the last battle for Hong Kong, this garrison. They didn’t know that the others had already surrendered so they kept fighting and they came in and massacred them all.

What was your father doing prior to being placed in Stanley Internment Camp?

He was the Superintendent of the Peak Tram in Hong Kong when the war came. His claim to fame was that he disabled it when the Japanese came and the capitulation occurred. He had the clippers in hand and would have had it if he hadn’t been quick off the mark.

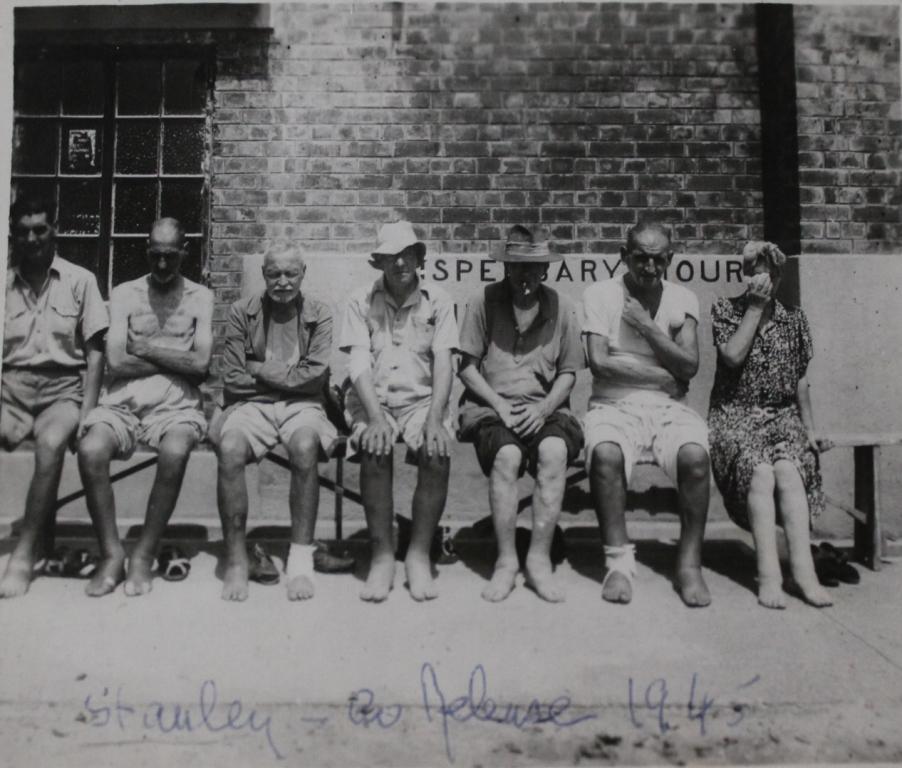

After the war, in 1945, despite the fact he was quite sick, and looked like one of these people in these photographs here, he got it up and running again by Christmas.

This is what the adults there looked like. These were taken just after the liberation.

Did you go hungry?

The kids didn’t no, but I think the adults did. There was very severe malnutrition amongst them. They went without to feed the children.

The death rate wasn’t too bad compared to other camps.

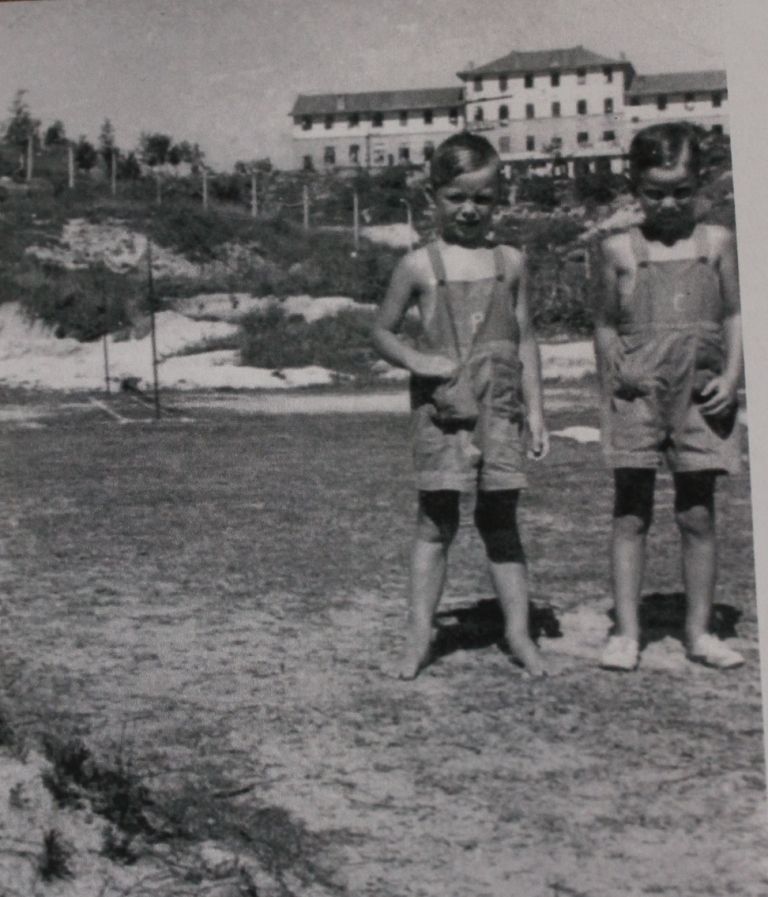

There was very limited schooling. There was a camp school for children but this was only two or three days a week and half a day at that, so we quite often skipped it. Because I was so young it was like a giant playground to me. We kids just went wild.

I remember we suddenly had rations, which we’d never had before because the Japanese didn’t give them to us, we suddenly had rice. The Chinese people on the streets of Hong Kong didn’t have anything, they starved for four years.

A lady, Barbara Anslow, who had been interned at the same camp kept a diary throughout that time and sent me this via email. Barbara Anslow says in this that the Chinese were starved and many of them died. The lady who wrote this is 96 now and read this on radio in London on the 15th August 2015 - VJ DAY. When I read through this some parts really struck a chord – this one for instance is what happened to us;

“On Friday August 10th, only a fortnight ago from today when at 10.30 a.m. news whipped around the camp that 175 Technicians and families were leaving Stanley by Japanese order. No details…”

We were all shipped off to a camp in Kowloon for the last two weeks.

Why did they move you to Kowloon?

There were Technicians there ‘for the reconstruction of Hong Kong’, which was a Japanese euphemism. But in fact I think we were moved there as part of a program of extermination. I think we may have been quite fortunate to have survived.

I have kept a piece here regarding that in my own diary:

“On the 10th of August 170 key civilians, including my father, my mother and myself, were transferred from Stanley Camp to Central Kowloon for, quote ‘the reconstruction of Hong Kong’. It was strongly rumoured after the Liberation that this was in fact a selection of personnel for possible extermination should the Japanese homeland be invaded.”

It was true, there were too many rumours for this to be ignored. The Japanese would have exterminated every prisoner, every allied serviceperson, the Australians, everybody, if they’d been invaded.

They gave up prior to this fortunately.

Can you remember any of the Japanese soldiers?

Not really, I recall they used to lecture us a bit. They would gather us, the whole camp, on this bit of a sort of village green here and harangue us. These were all about how we were to behave, to bow to the Japanese – bow like this to a soldier, bow like this to an officer.

'This photo was taken by the camp commandant, this picture of myself and my friend': Chris at Stanley Internment Camp, Chris is on the right – his little mate of then now lives on the Gold Coast

Do you recall the day of Liberation?

Oh yes, there was a hell of a noise. When we found out the Japanese had surrendered the whole camp went bananas. Nobody heard the surrender speech of course, only the Japanese.

The British and Americans moved the Japanese all back to Japan as fast as they could after the capitulation. There was no food for them where we were, nothing to enable them to look after them, so they put them all on boats and sent them back as fast as they could, unlike the Soviets, who kept them for five years. The Soviets broke the treaty and went into Manchuria and made some of the Japanese civilians walk a thousand miles to get out of there, just to survive – they were horrible to them.

This I learnt from another book – my wife has told me ‘no more war books’. I have researched a lot of it of course, for years. I have an extensive list of all the Japanese surrenders in Borneo, which is very interesting, and of course it was mainly to the Australians that they surrendered there.

So every place you were sent to work you did more research on what occurred there during WWII?

Yes, especially in the Sandakan area. I was the Manager there. They have a new museum in Central Borneo, in the interior where the March ended. That has all become bigger since I was there, there wasn’t much while we were there.

Have you been back there – to Stanley?

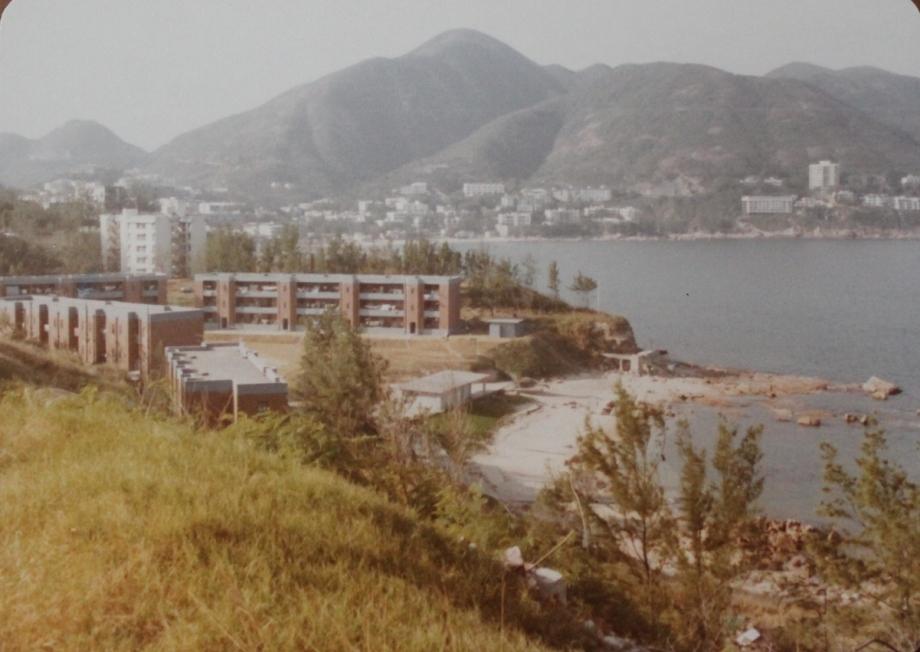

Yes, I went back a few years ago now. This is what it looks like when I went back – they’ve cleaned the place up and there has been some rebuilding – this I took around 1978. It was interesting for me. I walked all around and found all the nooks and crannies which I knew as a child. It was the last battlefield of Hong Kong before the Surrender.

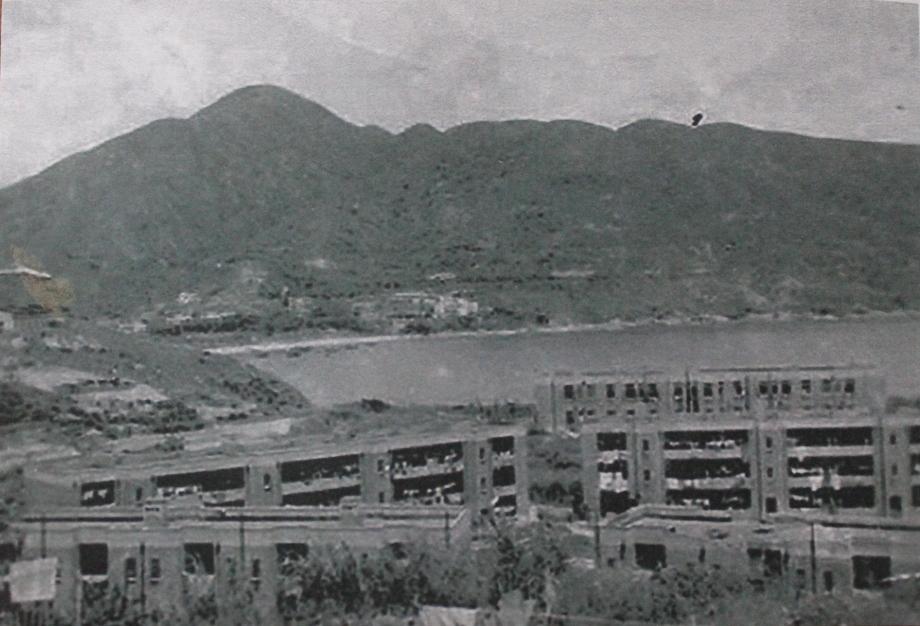

Text on back of: 'Indian Quarters: Stanley Camp - Blocks 13 & 14 were at rear of photo. We were in a small room at the end of Block 14.'

Photo from 1978

Remembrance Day and Victory in the Pacific Day have special meaning for you then?

Yes, it does because my parents were the sufferers from that and so I always attend because of them.

Did your parents recover from their experience?

My father didn’t live long afterwards, he was too weak, as you can see from the photographs. My mother lived on until she was about 80.

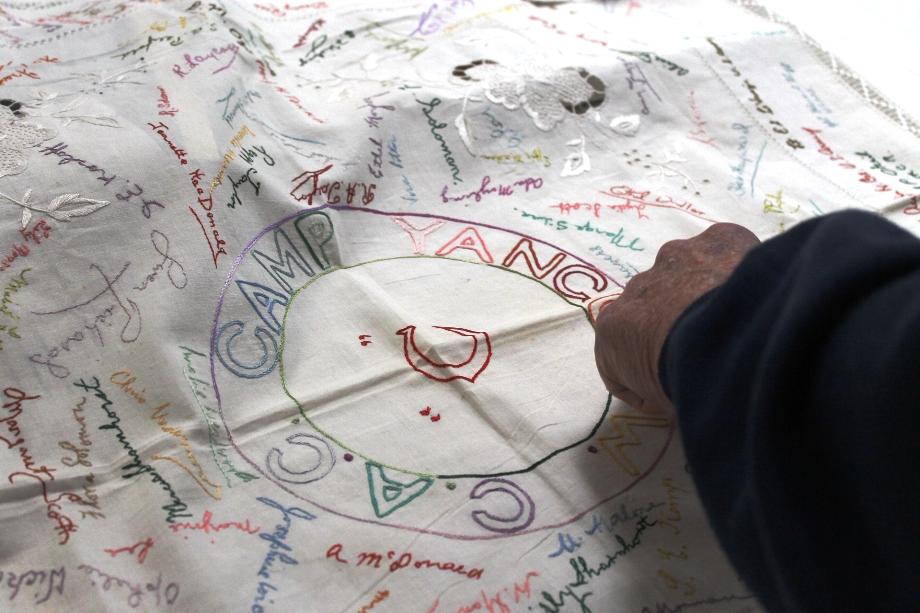

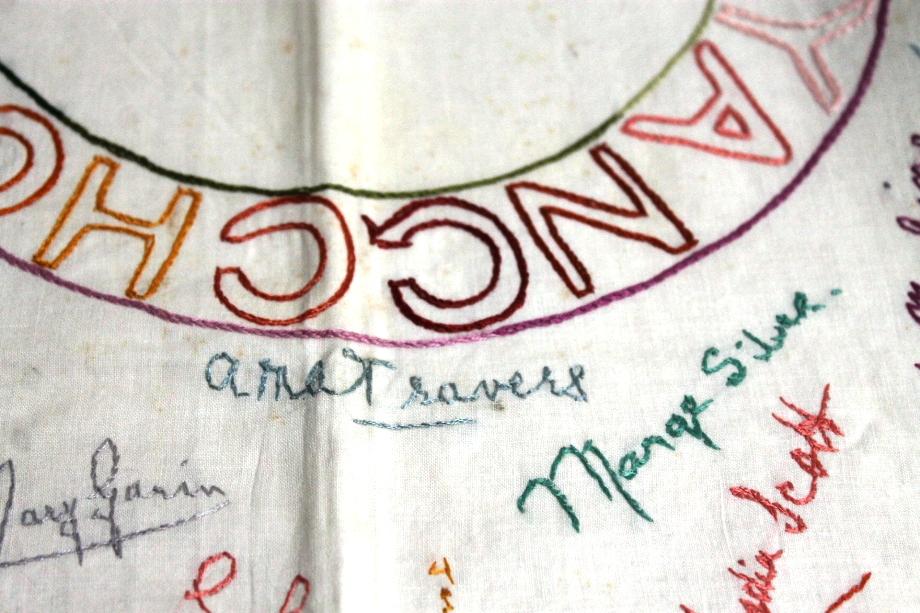

My grandmother, Amelia Margaret Travers, was in a camp in North China, Yangchow Camp, and she lived on until she was 97. She had a hell of a life, went through everything.

She lived through the Boxer Rebellion in China, during the First World War she was locked up in Hamburg, came back to the War Lords situation in China, which was a shambles, then got caught up by the Japanese and was placed in a camp, then got out again and went to Rhodesia where her son Norman Travers was.

I have her tablecloth from her camp which the camp inmates all signed and then she embroidered their signatures. This is very precious and quite old now of course.

Yangchow Embroidered Tablecloth: “CAC” actually stood for “civilian administration centre”.

What happened to you after the liberation?

I was just under 8 years of age when the war finished. We were evacuated to England and went to Sussex in southern England. I went to school there at a place called Christ Hospital in Sussex. Because I’d had no education before the age of 8 it was difficult, I was behind. I had to work hard to catch up. It was not very pleasant, I was sent to boarding school which I found very Dickensian. There were 800 boys there, all boarders. There were a couple of nice teachers I recall but the rest were all very boring in those days; they just did their job and weren’t really interested.

I didn’t go to university – in those days you left school and got a job.

What did you do?

I joined the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, in Hong Kong. I went in at entrance level as a Clerk.

What was it like going back to Asia after your childhood experience?

Interesting. Nothing much had changed by 1960. After the war had ended it was a mess there, a huge mess, everything had been bombed out, levelled.

Being born in Asia – did it still feel like your home?

It was nice to go back, yes.

What stands out as the biggest changes?

The whole economy changed. To begin with it was part of the British Empire and what was manufactured in Britain was sold in Malaya. Things then shifted to Import Substitution, where they decided to make everything themselves. The next step was of course Exports.

I was there from 1960 to 1985 and so saw huge development. The building stands out, construction just went bananas during those 25 years.

I didn’t spend all of that time in Hong Kong – I worked all over the place; Malaysia, Japan, Thailand, Germany, gradually going up and up the ladder. Before retiring I was Manager of East Malaysia.

It was interesting living in these various countries but wasn’t too good for a family life. I did learn a few languages though, and about these different cultures.

Did you have a favourite?

It’s hard to say, you made the best of everything wherever you were. Working in Japan was exciting. Apart from very hard work the language was so difficult I couldn’t pick up more than ‘Taxi!’.

The food in each place was wonderful.

You have also done some Service – how did that begin?

In those days in England you got called up for National Service when you were 18, no questions asked, everyone was in. When you signed up for National Service you were asked if you want to become an officer, I said ‘yes I do’. You are then asked if you have a regiment you want to join, and I said, ‘yes I do, I want to join the Kings Dragoon Guards’.

They are a very old regiment and they were in Malaya and I wanted to go to Malaya. It was the Far East and better than staying in some crummy Army camp in England or Germany.

I was sent to Malaya during the Malayan Emergency as part of the Armoured Car Regiment of the Army. We had to do a lot of street patrols and country road patrols, there was a lot of ambushing going on and night firing. I was posted there for one year.

In some ways it was quite fun, we learned how to use a gun and did all these patrols. I actually led the military parade through Kuala Lumpur on Independence Day in 1957. By then I was a Lieutenant.

National Service is now defunct – do you think it was a good thing for all young men to have had to do that?

Yes, I think so. There were a lot of young men there who had never left home in their lives and it made men out of them. It gave them a sense of discipline and broadened their horizons.

It was cancelled for purely political reasons. The Army didn’t like it either you know, they had all these National Servicemen coming in who weren’t professional enough. They simply weren’t professionals.

You sometimes wear medals to VP Day and Remembrance Day services; which are these?

I received Medals for the Malayan Emergency, a General Service Medal for the Army, the National Service Medal – and then the Malayan Government gave all a medal 50 years later!

What did you do after the years service as part of those sent to the Malayan Emergency?

As I was already in the bank prior to doing National Service, I went straight back to this afterwards and was then posted to Hong Kong.

Avalon Beach RSL Sub-Branch – you joined there?

Yes, I was co-opted by the President, Graham Sloper. He explained that as I’d done military service I could join up there. These organisations are great in providing a social function for service people.

I have also met Australians who served as part of National Service. The biggest difference was the Australian National Servicemen were all sent to Vietnam whereas British National Service people were sent all over the world, to Kenya, to Cyprus, to Hong Kong, to Malaya, anywhere British Colonialism had spread they were sent to these trouble spots.

I have placed a few souvenirs in Avalon Beach RSL’s cabinets – one is an unexploded 20mm cannon shell. It’s not a live shell of course, my father took all the mechanisms out of these, defusing them within the camp. It dropped right outside our window after one of these air raids, which were coming in every day towards the end. They would come in, machine gun the Japanese mortars and then disappear.

When did you come to Australia?

In 1985. My wife Joy was born in Sydney and our children were schooled in Australia. I met my wife in Borneo in 1963. Her father was there through the Colombo Plan, educating the people there so she went too. My future wife was only 23 when we met.

I ran a business from home here in Australia for a while which required my use of the Indonesian language but when Indonesia was no longer the flavour of the month in Australia that went by the by and I sold it. On reflection I have had the best of both worlds, the best of the East and the West.

What were your first impressions of Australia?

It was quite enjoyable – only 15 cents for a schooner…

That’s what you remember?

Yes! We lived in Wollstonecraft initially and then moved to this home in Avalon eventually in 2002. We lived on the bay here at Careel Bay at first, which was great for the grandchildren but I had a few mobility problems so we decided on this place, where it’s flatter.

What are your favourite places in Pittwater?

Whale Beach, we take the children along to there, and they’ve been part of the Surfing School at Palm Beach. I like the shape of these two beaches and they’re good for the children. We have six grandchildren, the youngest is 4 and the eldest 17.

What is your motto for life or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

I don’t really have one but if I did it would be ‘keep your feet on the ground and keep interested in what’s around you’.

Notes and References

*St Stephen's College

The massacre perpetrated at St Stephen's College is the least well-known. Only thirteen victims can be confirmed at the location, but reports and estimates put the real number as high as 99. The names of all the reported victims may never be known. Between 75 and 150 bodies were cremated by the victors in the aftermath of the battle, but this total includes the victims of the fighting around Stanley Fort, such as the men of 965 Defence Battery. Although it is the "most infamous massacre", it "has been the hardest to match with records."

Several hours before the British surrendered on Christmas day at the end of the Battle of Hong Kong, Japanese soldiers entered St. Stephen's College, which was being used as a hospital on the front line at the time. The Japanese were met by two doctors, Black and Witney, who were marched away, and were later found dead and mutilated. They then burst into the wards and bayoneted a number of British, Canadian and Indian wounded soldiers who were incapable of hiding. The survivors and their foreign nurses were imprisoned in two rooms upstairs. Later, a second wave of Japanese troops arrived after the fighting had moved further south, away from the school. They removed two Canadians from one of the rooms, and mutilated and killed them outside. Many of the foreign nurses next door were then dragged off to be gang raped, and later found mutilated. The following morning, after the surrender, the Japanese ordered that all these bodies should be cremated just outside the hall. Other soldiers who had died in the defence of Stanley were burned with those killed in the massacre, making well over 100 altogether.

When Stanley became a civilian internment camp, the internees gathered up the burnt remains, shards of bones, buttons and charred effects from the cremation, and then buried them. A gravestone marks the spot where these items were interred at Stanley Cemetery.

Battle of Hong Kong. (2015, November 12). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Battle_of_Hong_Kong&oldid=690364669

St. Stephen's College massacre. (2015, November 11). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=St._Stephen%27s_College_massacre&oldid=690101135

The Peak Tram

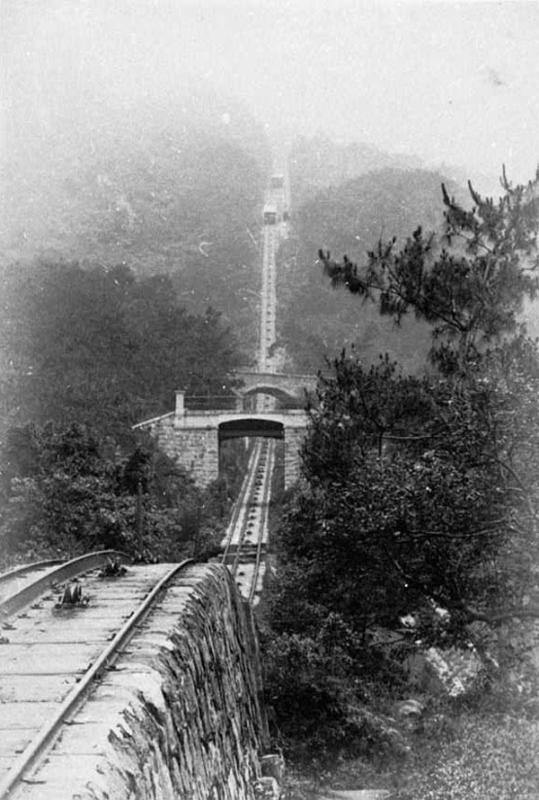

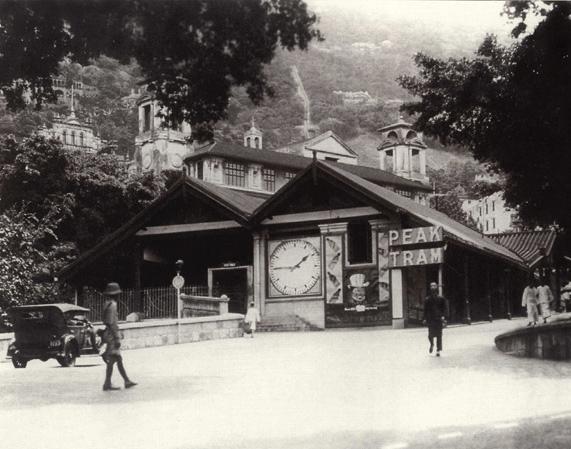

Since 1888, The Peak Tram has served Hong Kong, quietly witnessing 120 years of the city's changes. The Peak Tramway is a funicular railway in Hong Kong, which carries both tourists and residents to the upper levels of Hong Kong Island. Running from Garden Road Admiralty to Victoria Peak via the Mid-Levels, it provides the most direct route and offers good views over the harbour and skyscrapers of Hong Kong.

History overview: www.thepeak.com.hk/en

On 11 December 1941, during the Battle of Hong Kong, the engine room was damaged in an attack. Service was not resumed until 25 December 1945, after the end of the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong.

Uphill tram route 1897 The original uploader was Kevinhksouth at Chinese Wikipedia - Transferred from zh.wikipedia to Commons.

The Peak Tram, Garden Road Terminus, circa 1920

Hong Kong's Defenders, Dec 1941 - Aug 1945

from Hong Kong War Diary website

Civilians:

Chubb Mrs. No 287 LRTP

Chubb Child, No 287 LRTP

Chubb, S.F. 52, Peak Tramways, No 287 LRTP

" After the Japanese forces occupied the Kowloon Peninsula in December 1941, they installed heavy artillery there and commenced shelling the Peak in an effort to destroy the barracks.

The engine room of the Tram was severely damaged and to this day there is still part of a Japanese shell lodged under a base plate.

Jack Chubb, the superintendent engineer at that time, spent several hours cutting essential wiring in the engine room to make sure thatthe Japanese would not be able to use the Peak Tram. Unfortunately, his work was interrupted by the sudden arrival of Japanese troops, but he managed to conceal his wire cutters or he would have suffered the fate of other saboteurs - decapitation." - Grand old lady to turn 110, Eric Cavaliero, Thursday, July 24, 1997. The Standard, Hong Kong, retrieved from http://www.thestandard.com.hk/news_detail.asp?pp_cat=&art_id=52189&sid=&con_type=1&sear_year=1997

NB: Chris' father was actually named 'Frank' not Jack.

Stanley Internment Camp

Stanley Internment Camp was a civilian internment camp in Hong Kong during World War II. Located on the Stanley peninsula, on the southern end of Hong Kong Island, it was used by the Japanese imperial forces to hold non-Chinese enemy nationals after their victory in the Battle of Hong Kong. About 2,800 men, women, and children were held at the non-segregated camp for 44 months from January 4th, 1942 to August 16th, 1945, after Japanese forces surrendered. The camp area consisted of St. Stephen's College and the grounds of Stanley Prison, excluding the prison itself.

The internees numbered at 2,800, where an estimated 2,325 to 2,514 were British. The adult population numbered at 1,370 men and 858 women, and children 16 years of age or younger numbered at 286, with 99 of whom were below the age of 4.

The internees were freed on 16 August 1945, the day after Emperor Hirohito broadcast his acceptance of the Potsdam Proclamation in surrender. About two weeks later, the British fleet came for the internees, and several weeks after that, the camp was closed. Many internees went back to the city and began to adjust back to their former lives, and many others, particularly those of poor health, remained on the camp grounds to await for ships to take them away. Historian Geoffrey Charles Emerson wrote the "probable" reason the British internees were not repatriated before the end of the war was related to the Allied forces refusing to release Japanese nationals held in Australia. These nationals were the only sizable group of Japanese nationals held by the Allies after the repatriation of the American and Canadian internees. They had been pearl fishermen in Australia before the war, and knew the Australian coastline well. Their knowledge would have been "militarily important" to the Japanese if an invasion of Australia was attempted, hence the Allied refusal to release them.

In the UK, from 1952 to 1956, about 8,800 British internees, specifically those who normally resided in the UK when the war began, received a sum of ₤48.50 as reparation. Payments for American and British internees were made from the proceeds of Japanese assets seized per the Treaty of San Francisco.

Most had lost everything during the subsequent looting that took place after Hong Kong fell.

Copyright Christopher Chubb, 2015.