January 8 - 14, 2012: Issue 40

Above: Phil Colman searching for marine treasure in a big kelp stranding on Collaroy Beach.

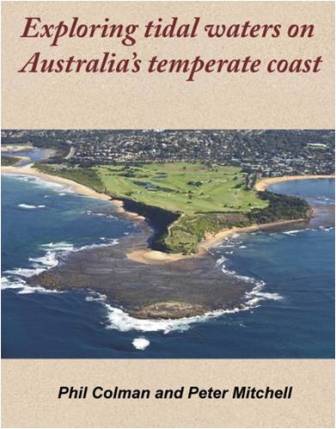

Below: Peter Mitchell above the cliffs near Port Campbell, his favourite bit of coast.

“Guides have taken groups of people, or school children, or church or sporting groups over places like Long Reef for many years. Why? Television and newspapers and books have opened a door recently to a life - or should we say ‘lives’ - that have been there forever but which few of us have ever seen. Children, and now adults, have come to visit a shore platform today and gone home to remember that day as something special, something magic right on their doorstep.

We challenge you to visit a shore platform during low tide and discover some of that magic. And take this book as a guide. No! It will get wet. Go home with this book and relive your adventure, again and again.”

The senior author, Phil Colman, has been taking groups of people over the rock platforms of the northern beaches for about 40 years. As a marine biologist, formerly of the Australian Museum, he is well equipped to explain the very rich and bio-diverse life of the intertidal zone there.

The senior author, Phil Colman, has been taking groups of people over the rock platforms of the northern beaches for about 40 years. As a marine biologist, formerly of the Australian Museum, he is well equipped to explain the very rich and bio-diverse life of the intertidal zone there.

This book is designed to answer, in simple language, the many questions he has been asked over the years – What is it? He describes the book as scientifically accurate but not scientifically boring. Co-author Peter Mitchell, a retired professor, added not only substantially to the written word but supplied all the many excellent photos, nearly all of which were taken locally.

The title indicates that the facts in the book apply equally to the whole of the non-tropical coast, so readers in say Tasmania would feel equally at home.

Available at Berkelouw Books Mona Vale, or Dee Why; or The Coastal Environment Centre in Narrabeen, (all $22), or groundtruthmitchell@gmail.com ($25 incl. postage).

Phil Colman, Peter Mitchell and 'Exploring tidal waters on Australia’s temperate coast'

Last year Pittwater, the Northern Beaches and Australia itself was enriched by the release of a great book by two local gentlemen, 'Exploring tidal waters on Australia’s temperate coast'.

As part of our Summer Mix the writer and photographer of this work share an insight into this work. Perfect for Summer explorations of where the earth meets the sea.

Phil Colman

Marine life has been on our rocky shores forever. Well almost, geologists tell us there was none when the oceans first formed but in a human context it has always been there but it is forever changing in any time frame you like to observe, between the tides, through the seasons, over decades and over millennia. It is both the diversity of life forms and the dynamics of change that make coastal shore platforms so fascinating. The rocky shore is one place where you can observe a totally different world on any visit and always come away with new knowledge.

I have walked and waded over Long Reef, or Newport headland, or Fairlight; or Flinders Is., or Mornington all my life, and wherever I go I’ve asked myself why? Why is that shellfish doing that? Why is that seaweed that shape? Why is that crab avoiding that pool? For 40 years I have been taking groups of all ages over those platforms, and every time many questions have been asked. Finally, calling on my co-author Peter Mitchell, we wrote a book to answer just some of those questions.

But before that, I’ll chart, briefly, my life so far. Born in Inverell, I came to Narrabeen when I was three, and the northern beaches have been my home ever since. From Narrabeen Primary School, I graduated to what was then affectionately known as Shacktown, or officially Balgowlah High, but when the newly built Manly Boys High opened, I moved there. That was the end of formal study but degrees and diplomas are superfluous when enrolled in the University of Life. In later years, while I was not fossicking on Long Reef or beach fishing (with, of course, my own caught beach worms) I worked with Dad in a printing/price-listing/advertising business.

In 1966 I was enticed away from the coast and worked for the B.P. Bishop Museum of Honolulu in their Field Station in New Guinea, where for four years I never saw the sea but chased vertebrates and insects mainly in the highlands. Then back in Sydney, I joined the Australian Museum (in the shell department) where I worked until I retired about 30 years later.

The book started out as a small set of notes I drew up to give to people I took out on rock platforms. I know nothing of geology and welcomed Peter who could talk rocks the way I couldn’t. What we originally thought would be a small, localized booklet certainly surprised us when a 128 page, 200 colour photos publication eventuated, nearly all photos taken by Peter.

The title Exploring tidal waters on Australia’s temperate coast incorporates the word ‘temperate’, as we both realised that what occurs here on the northern beaches also occurs right round non-tropical Australia. In fact, I sent a copy to a colleague in South Africa, who replied that he could take it down to his local rocky shore and feel really at home with it. We could sell this book around the world – if only we had the resources of a major publishing house!

The Coastal Environment Centre at Narrabeen (Pittwater Council) has been running a very successful programme called Coastal Ambassadors “Prepared for the communities of NSW who care about the coast”. I have been recently involved, and may play a larger role in coming years. Open to all, most participants so far have been from surf clubs who are keen to know and understand more about their local marine environment. In 2012 the programme has been extended to the State.

My favourite place on the Northern Beaches? Well it would have to be Long Reef wouldn’t it?

And a philosophy for life? Well if I have one it is that understanding biological life is a never-ending learning experience.

Peter Mitchell

I was born at an early age in Moonee Ponds, two things I share with Dame Edna. The eldest son of a milliner and a baker and I nearly became the third generation baker in the Mitchell family. But after primary and secondary school in Dandenong and Croydon life took a left turn and I landed a job as a lab technician at RMIT where I was able to develop a life-long interest by studying geology.

Some of my earliest fieldwork was along the spectacular cliffs of the Victorian coast from Cape Otway to Port Campbell and around the Mornington Peninsula. I still go back whenever I can and in recent years have taken groups of American undergraduates there (and elsewhere) on conservation projects with International Student Volunteers.

Later employment saw me mapping tunnels in the Snowy Mountains Scheme, searching for gold, copper, bismuth and uranium in the Northern Territory, and building airstrips in Victoria, Tasmania and the central west of NSW.

Chance brought me to Macquarie University shortly after it opened where I spent the next 30 years again as a lab technician and subsequently as an academic with a real PhD teaching physical geography and environmental science. Thousands of students later and with the University restructuring to address financial crises I retired early, then taught for several semesters and summer schools in the University of Canterbury in Christchurch NZ. For the last decade I have been self-employed as a consultant mainly advising archaeologists about the nature of past landscapes on Aboriginal sites in the eastern States. Somewhere in all of that I managed to squeeze in five seasons on a Bronze Age village site in Apulia, and of course we raised a family of three girls.

I first encountered Phil when we both served on a Scientific Advisory Panel for Manly Council. This ran for more than ten years and often dealt with coastal issues. At some stage Phil gave me copies of his notes and the idea of a joint book was born, I confess it did a have a long gestation but we are very pleased with the end product and are already talking about the next one.

A motto for life?

Walk lightly on the Earth, you only get one turn and be guided by Kipling’s ‘Six Honest Men’. Keep asking – what, why, when, how, where, and who.

What on earth are cunjevoi? Is it a plant or an animal?

Well there are actually two different things using this Aboriginal word in Australia. Sea squirts or acsidians found on the east coast temperate shores, and a large lily that grows in subtropical Queensland.

Well there are actually two different things using this Aboriginal word in Australia. Sea squirts or acsidians found on the east coast temperate shores, and a large lily that grows in subtropical Queensland.

We don’t know why these organisms have the same name, in fact we are not even certain from which Aboriginal language the word is derived but surmise it was probably first used by Europeans near Sydney.

The plant Alocasia brisbanensis, resembles an arum lily and is also known as spoon lily. All parts of the plants are extremely toxic but young shoots were eaten by indigenous people after careful pre-treatment and thorough cooking.

On the coastal rock platforms we find dense clusters of marine sea squirts, Pyura stolonifera at and below low tide level. Once a favoured food of Aboriginal people and still collected as bait by rock fishermen, cunjevoi are sessile (attached) organisms that squirt a quantity of water into the air from one of two body siphons on the top of their leathery coat (tunic and hence tunicate) if touched or disturbed when exposed.

Adult cunjevoi stand about 150 to 200mm high and in rough water conditions can be very crowded on the rocks. They are not very attractive to look at, are often coated in sea weed, and a lot of people imagine them to be plants but in fact they have been placed in the Sub-Phylum Urochordata because their tadpole like free swimming larvae have gill clefts, a tail, a nerve cord, and a notochord which we think is a precursor of a vertebrate spine. Adults however bear no resemblance to vertebrates! The larvae have a fairly short life as free individuals, maybe 24 to 36 hours and apparently detect the presence of adults from some chemical signal in the water and attach themselves head down in an existing colony. There they spend the rest of their days, probably a few years, functioning like a glued down vacuum cleaner pumping seawater through the body to filter feed, to obtain oxygen, and to dispose of wastes.

Only one species of cunjevoi is found around Australia. Pyura stolonifera extends from Shark Bay on the Western Australia coast, around the south coast and Tasmania, and up past Sydney to Noosa. If adult cunjevoi cannot move and the larvae only have such a short period of free movement then how does the population maintain a single gene pool across such a great distance and in different water bodies? That’s a question to which we don’t have an answer.

On a global scale the same animal is found on the shores of South Africa from Cape Town to Natal, and as a small population spread over 70km of coast in the Bay of Antofagasta in Chile. The first thoughts of biologists looking at this pattern were that cunjevoi evolved when the southern continents were joined as Gondwana. More recently the DNA of the species has been examined and it is clear that the African and Australian populations are rather different and that one of them should be given a new name. The Chilean population however is virtually identical to the animals in Sydney and for that there is a simple explanation. In the early 20th Century Antofagasta was an important port shipping nitrate fertiliser to Australia and cunjevoi undoubtedly crossed the Pacific on the hulls some of those ships.

In Chile the cunjevoi invasion has disturbed the inter-tidal zonation by displacing a native mussel upwards. Cunjevoi seem to grow taller in Chile and they certainly grow in denser clumps than we normally see. Exotic species often have a competitive advantage in new environments and the absence of their usual predators often allows a change in body form or habit.

Remarkable how far a simple question can take you isn’t it?