August 11 - 17, 2013: Issue 123

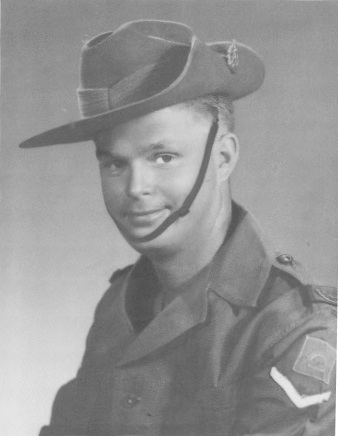

Henry John Chisholm

Our 2013 Vietnam Veteran’s Profile is a regular visitor to Club Palm Beach where the annual Vietnam Veteran’s (Northern) March and Service at Club Palm Beach (Palm Beach RSL) takes place, and a resident of the Central Coast at Point Clare. Every year the Vietnam Veterans (Northern) Group have a March (gather at PB Ferry Wharf 10.30am), Service and lunch together. This precedes the official Vietnam Veterans Day which this year will be Sunday 18th of August. On the 17th of February every year there is a Memorial Service for those we lost on Bribie Island in Queensland.

In reading this interview you will not hear the sighs and pauses in Henry’s voice when relating losing platoon members or helping to evacuate wounded men. To hear pain in men’s voices, or feel a shiver when they relate losing members of their platoon in conflict, or the drop to silence, to wordlessness when asked about returning to an atmosphere of vilification from Australian citizens and the Press when they could finally come home, you will need to be among those who attend a Vietnam Veteran Day Service and be prepared to listen should you be fortunate enough to meet one who can talk, who will speak, who can utter a few words about how it felt to be spat on, jeered, booed…for following orders, for serving their country, for putting their life at risk.

No one escaped this conflict unharmed. Those who returned home unwounded physically were already carrying scars that cannot be seen. They were then made to haemorrhage again, at our hands. This week we are very privileged to share a few insights from one of those men who did serve in this conflict and continued to serve.

Where and when were you born?

Northampton in Western Australia on the 11th of March, 1937.

Did you grow up there?

Yes, I stayed in the West until I was 21 years of age and then went to

Perth. I joined the Regular Army in 1959. Prior to then I was working on a farm

at Northampton with my dad, sister and brother; we ran sheep and grew wheat. It

was pretty tough then, I couldn’t make a go of it. There was my dad and my

brother and we were only on a small farm of 3000 acres.

Yes, I stayed in the West until I was 21 years of age and then went to

Perth. I joined the Regular Army in 1959. Prior to then I was working on a farm

at Northampton with my dad, sister and brother; we ran sheep and grew wheat. It

was pretty tough then, I couldn’t make a go of it. There was my dad and my

brother and we were only on a small farm of 3000 acres.

When I first joined the Regular Army I had to do all my recruit training and then went to an infantry Battalion – the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment. I did my recruit training at Kapooka in N.S.W. New South Wales was a bit of an eye-opener then, very different from W.A.

We did 17 weeks of Basic Training; Drill, Weapons, Route Marches, Map Reading, Field Craft. From there I went to the 4th Battalion which then was a Ingleburn.

At Ingleburn we learned the Infantry Corp Training.

From there I was posted to the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, at Holsworthy, this was September 1959

How long were you there?

I stayed in 2nd Battalion until 1965 but in 1961 to 1963 I had two years in Malaya during the Malayan Emergency. We came in at the end of the Malayan Emergency.

What did you think of that experience?

It was different. I rather enjoyed it; we had barracks life at Terendak Camp in Malacca. We did operations up along the Malay-Thai border against the CT’s (CT: ‘communist terrorists’).

Did you come under fire?

No, but we were deemed to be on Active service because we were carrying live ammunition and did ambushes, but we didn’t have any contact with anyone.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, 2 RAR undertook two tours of Malaya during the Malayan Emergency, the first between October 1955 and October 1957 and the second between October 1961 and August 1963. During the second tour they were stationed at Camp Terendak near Malacca in October 1961. In August 1962 they were committed to anti-Communist operations in Perlis and Kedah once more, searching for the remnants of the Communist terrorists along the Thai-Malay border. This lasted only a couple of months before it was decided to withdraw the Battalion from this role for six months' training as part of the FESR. Regardless, several 2 RAR companies were used on further operations against the Communists in May 1963, before the battalion returned to Australia in August, without having suffered any losses. (1.)

Terendak camp - 1964

We came home then, in 1963, and then 6th RAR was formed on the 6th of

June, 1965 and I was promoted then to a Sergeant.

What does being a Sergeant entail?

You’re an understudy to the Platoon Commander. You’ve got the Platoon Commander who is the head of the platoon and then you have the Sergeant who is an understudy to the Platoon Commander and is also responsible for all the administration of the 32 fellas in the platoon. I was 4 Platoon B Company.

When were you sent to Vietnam?

On the 28th of May, 1966 because I went on the advance party for 6 RAR up to Ben Wa (Bien Hoa) and we had to get up there and take over all of 1 RAR’s stores. We came back from there to Nui Dat and the rest of the battalion joined us there.

What was it like being first in?

It was the big unknown, we were very apprehensive.

Did you come under fire while there?

No, we didn’t have any contact until late in June.

Do you still have a clear recall of the events you experienced while in Vietnam?

Some of them I do. The first major Operation we did was on the 24th of June, 19666when we first came under heavy fire everyone was scared, which is normal. They started to fire mortars on us, which dropped close by, and we had two fellows killed. These weren’t from my platoon but from 6 Platoon; there were 2 KIA, both from 6 Platoon, and they had seven or eight wounded, whom we had to evacuate out by helicopter.

What was the biggest conflict that you were involved in?

The Battle Of Long Tan in Aug 66 in which B Coy was involved as part of the relief force for D Coy and then Operation Bribie in Feb 67.

What were your orders?

We were told there was a small enemy camp at a certain location, 15 kilometres southeast of Nui Dat. We were to be choppered in. We were the second Company to go in; A platoon went in first and came under heavy enemy fire. We followed them in and we received small arms fire while we were coming in on the choppers.

Photo: Phuoc Tuy Province, Vietnam. 18 February 1967. A RAAF Iroquois

helicopter (also known as a Huey) from No. 9 Squadron assisting the 6th

Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) while they are on patrol in the

Nui Dinh Mountains known as the Warburtons by soldiers from the 1st Australian

Task Force. (Donor P. McNamee) Australian War Memmorial Image

P02629.027

Photo: Phuoc Tuy Province, Vietnam. 18 February 1967. A RAAF Iroquois

helicopter (also known as a Huey) from No. 9 Squadron assisting the 6th

Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) while they are on patrol in the

Nui Dinh Mountains known as the Warburtons by soldiers from the 1st Australian

Task Force. (Donor P. McNamee) Australian War Memmorial Image

P02629.027

We landed and then the Commanding Officer told us that we had to do a company attack and A Company were to give us covering fire while we went in to try and take this position out.

So we were two platoons forward and one in the rear; I was in 4 platoon on the left forward, 5 platoon was on the right and we only went about 50 metres and couldn’t go any further; we were pinned down with small arms fire and MG fire. I had one soldier killed, when we’d only gone 20 yards I suppose, when he got shot…and I had another wounded. So we had to stop and allow 6 Platoon to come through us, mind you this was under orders by the O.C. Major Ian Mackay, so they pushed forward and 5 platoon was told to also go forward as well. And then they had a lot of casualties.

6 platoon also got pinned down and couldn’t go forward so it was really 5 platoon that was ordered by the O.C. to go forward and subsequently lost a lot of guys.

Eventually they got artillery fire in and ten thy got mortar fire and air strikes but we had to stop, we couldn’t go any further.

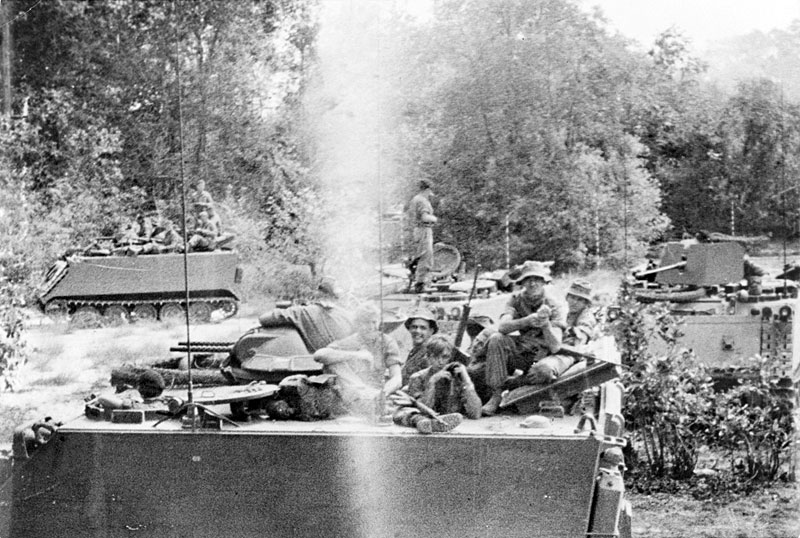

They brought in, because 5 platoon had so many casualties, the APC’s who tried to get all the wounded out. They too came under heavy enemy fire and they had an APC hit by an RPG which killed the driver and wounded the commander.

Eventually we got enough APC’s in to get all the wounded out … and some of the dead.

It was a terrible Operation.

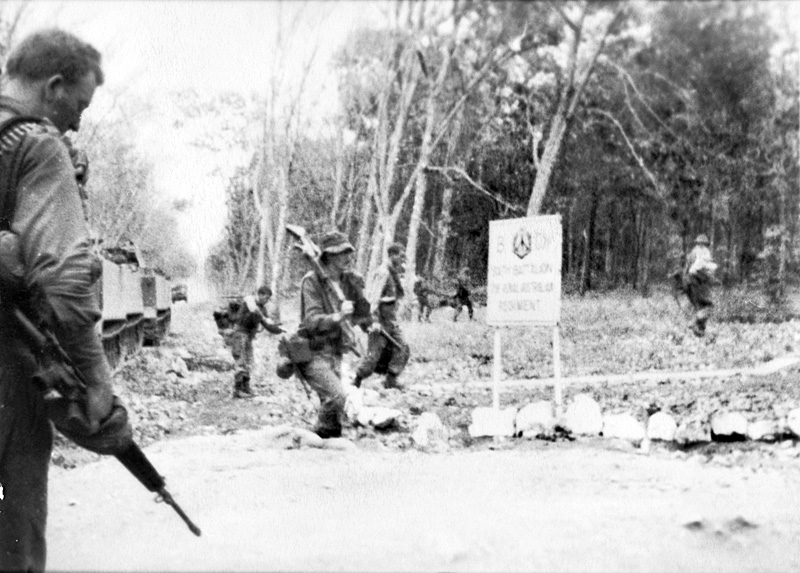

Members of 6RAR return to the Battalion lines after Operation Bribie. [AWM P02809.008

When did you get to leave the field?

It was right on dark. We were there until right on dark and then we pulled back a couple of kilometres to bivouac overnight…but there were still wounded guys out there… and one fellow we didn’t find until the next morning.

Was he still alive?

Yes, he was still alive, and we saved him.

Operation Bribie (17–18 February 1967), also known as the Battle of Ap My An, was fought during the Vietnam War in Phuoc Tuy province between Australian forces from the 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6 RAR) and two companies of Viet Cong from D445 Battalion, likely reinforced by North Vietnamese regulars. During the night of 16 February the Viet Cong attacked a South Vietnamese Regional Force compound at Lang Phuoc Hai, before withdrawing the following morning after heavy fighting with South Vietnamese forces. Two hours later a Viet Cong company was subsequently reported to have formed a tight perimeter in the rainforest 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) north of Lang Phuoc Hai, near the abandoned hamlet of Ap My An. In response the Australians mounted a quick reaction force operation. Considering that the Viet Cong would attempt to withdraw as they had during previous encounters, forces from 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) would subsequently be inserted into blocking positions on the likely withdrawal route in an attempt to intercept and destroy them.

On the afternoon of 17 February 6 RAR deployed into the area north-west of Hoi My by AmericanUH-1 Iroquois helicopters and M113 armoured personnel carriers (APCs) in an attempt to cut off the anticipated Viet Cong withdrawal, establishing blocking and assault forces. Following an airmobile assault into an unsecured landing zone at 13:45, A Company 6 RAR was subsequently surprised by a strong, well-sited and dug-in Viet Cong force, which, rather than withdrawing, had likely remained in location as part of an attempt to ambush any reaction force sent to the area. The Australians were soon contacted by heavy small arms fire, with a third of the lead platoon falling wounded in the initial volleys. A Company subsequently broke contact and withdrew under heavy fire from what appeared to be a Viet Cong base area. Initially believing they were opposed by only a company, 6 RAR subsequently launched a quick attack by two companies. However, unknown to the Australians the Viet Cong had been reinforced and they now faced a battalion-sized force in well prepared positions.

With A Company providing fire support, B Company assaulted the position at 15:35 with artillery, air strikes and armour in support. From the outset the lead elements came under constant Viet Congsniper fire from the trees, and from machine-guns that had not previously been detected by the Australians. The assault soon faltered with steadily increasing casualties as the Viet Cong resisted strongly, withstanding multiple frontal assaults, including bayonet charges by two separateplatoons. Surrounded and receiving fire from all sides, the lead Australian elements from B Company could advance no further against a determined and well dug-in force, and all attempts to regain momentum were unable to dislodge the defenders. Initially the Australians had used their APCs to secure the landing zone at the jungle's edge, however with the infantry in trouble they were subsequently dispatched as a relief force. Fighting their way forward, the M113s finally arrived by 18:15 and began loading the most badly wounded as darkness approached. The Viet Cong subsequently launched two successive counter-attacks, yet both were repulsed by the Australians. During the fighting one of the APCs was subsequently disabled by a recoilless rifle at close range, killing the driver.

Members of 6RAR atop APCs during Operation Bribie. [AWM P02629.007]

Finally, by 19:00 B Company was able break contact and withdrew after a five-hour battle, moving into a night harbour near the landing zone with the remainder of the battalion. Mortars, artillery fire and airstrikes covered the Australian withdrawal, and then proceeded to pound the battlefield into the evening. After a tense night the Australians returned the next morning only to find that the Viet Cong had left the area during the night, successfully avoiding a large blocking force while dragging most of their dead and wounded with them. A hard fought affair at close range, the Viet Cong had lost heavily during the fighting, yet the disciplined force had matched the Australians as both sides stood their ground, inflicting numerous casualties on the other before each fell back. (3)

Were you sent home then?

No, I stayed there. I came home with the main body in June of 1967. We did a lot of other operations between Bribie and when we came back, a lot of other operations, but they were nothing compared to Bribie. We were still in the same area.

Did you get a sense that there was any positive improvement during this time from the end of Operation Bribie up until you came home?

Well, it quietened down a bit in Phuoc Tuy Province but they were so spasmodic; they’d come and go.

Where were you sent when you came home in June 1967?

I came back to Brisbane. We had leave and I think I had about five weeks leave and then back into barracks. Soon after we finished leave 6 Battalion had to move from Brisbane to Townsville.

I went to Townsville for 12 months and then, because they were moving people around, I got posted out and I was posted back to Western Australia!!

What was it like coming home after experiencing Vietnam?

Like a holiday, and a relief.

I became an instructor then for what they call the Training Cell at Karakata in Western Australia. I had three years there then they posted me again to another Army Reserve Unit at Victoria Park in Western Australia with the 16 Battalion. I had another three years there and then I had another posting to Kapooka … so I did the full circle.

I was a CSM at 1 RBT at Kapooka (1st Recruit Training Battalion) and I had about four and a half years there and was promoted to Warrant Officer Class 1 and they sent me back to an Army Reserve in Victoria as their RSM (Regimental Sergeant Major) and I had 18months to two years there and was then posted to the 5th/7th Battalion at Holsworthy as the RSM.

At that stage I had my twenty years up so I though, I’ve got to think of my wife and my children, I had four boys; they been to every school – they’d been to Queensland, Western Australia, Victoria and New South Wales for their schooling and I wanted them to settle down.

So at the end of twenty years I decided I’d take my discharge.

What did you come out as?

As a Warrant Officer Class 1.

What did you do then?

Well, after a good break, I bought myself a little lawn mowing run. I was mowing lawns up here on the Central Coast – out of Terrigal.

What attracted you to the Central Coast?

My wife comes from Ettalong Beach. We first met in 1960 at a dance at Parramatta.

What song were you dancing to?

It was all the old time waltzes, it was good. After I met her we communicated by writing to each other, she wrote to me all the time I was in Malaya. When I came back form Malaya we got married, on the 28th of March, 1964.

She must have been panic stricken the whole time you were away.

Oh yes, particularly when I was in Vietnam. My second eldest son was born while I was on Operation Bribie and I didn’t know he was born until two weeks after Bribie because the mail was so slow getting through.

You chose a lawn mowing run when you finished your service career; did you need to stay outdoors; so many people who have served in any conflict cannot easily fit back into the roles and life they had prior to serving in any conflict?

Yes. I found it was great for me because I was outdoors, I was in the sunshine, I was my own boss and I could do what I pleased. I don’t think I could have worked for a boss. I was still, I suppose, suffering a little bit.

Do you still have days or nights now where you are back in the battle?

Yes. You have a lot of flashbacks of some of the traumas. On one of the operations we had one of our soldiers killed accidentally by one of our own. That was my worst day in the Army…it was just purely an accident but it played on my mind. I was the first one to get to him, to find him…It was terrible.

If there was something you could communicate to our younger readers about serving your country, one positive and one negative, what would it be?

You have got to be prepared for the worst….whether it’s you or your mate or... a mine explosion, killed in action, in an ambush, you may get wounded while doing an attack...

On the positive side I suppose you have got to be positive just to have your wits about you and be determined.

When our

Vietnam Veterans returned home they experience vilification in our Press and at

the hands of strangers in the community. How did that affect you, did you have

any experience of that?

When our

Vietnam Veterans returned home they experience vilification in our Press and at

the hands of strangers in the community. How did that affect you, did you have

any experience of that?

Yes, it did happen. The March back through Brisbane when we came home; we were jeered and booed and spat at.

Photo: Members of 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) march through the streets of Brisbane after arriving home from Vietnam on the 14 June 1967. More than 2,000 people, friends and relatives, gave a rousing welcome to the 500 troops arriving home from Vietnam onboard the HMAS Sydney, 60,000 people later lining the route as they marched through Brisbane city. Image P06136.011 courtesy Australian War Memorial

I also wanted to join my local RSL and was told I’m not entitled to it because we didn’t fight in a war.

When people became more aware that people who had been sent to Vietnam

went with the best intentions, thinking they were serving their country, and the

Welcome Home march occurred in October 1987, how did it feel for you…did this

have a healing effect for you?

When people became more aware that people who had been sent to Vietnam

went with the best intentions, thinking they were serving their country, and the

Welcome Home march occurred in October 1987, how did it feel for you…did this

have a healing effect for you?

It certainly does and did.

I don’t drink anymore. I used to drink a lot when I first came back but I don’t drink at all anymore. I’m 76 now and I stopped drinking about four years ago; the main thing now is to stay fit and healthy.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater?

Palm Beach RSL – that’s about the only place I go to regularly.

We hope to launch Wyong Online News next year so since we do, and are already collecting material - What is your favourite place on the Central Coast?

Now, it would be the Gosford RSL - it has a great atmosphere and I’ve met some real characters there at the RSL. You can get a good meal there too.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

My motto is always be positive.

__________________________________

References:

1. 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment. (2013, July 15). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=2nd_Battalion,_Royal_Australian_Regiment&oldid=564307421

2. 6th RAR Association: http://www.6rarassociation.com/

3. Operation Bribie. (2013, May 30). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Operation_Bribie&oldid=557441992

B Company 6 RAR – Operation Bribie

First Day: 17 February 1967;

Townsend's plan envisioned A Company advancing south approximately 200 metres (220 yd) and engaging the Viet Cong in an attempt to split their fire and provide fire support, while B Company would move around from the right flank to launch the assault. Meanwhile, C Company would occupy a blocking position to the west, while D Company would be kept in reserve. B Company would then assault in a south-east direction on an axis that would take them across the front of A Company, which would require their fire to cut-out as they did so. The scheme of manoeuvre was based on the assumption that the Viet Cong position was a camp as previously reported, and not a defensive position, yet with visibility in the thick vegetation limited to between 10 to 30 metres (11 to 33 yd), few of the men from A Company had actually seen much of the position during the earlier fighting. Yet the Viet Cong had likely now been reinforced by North Vietnamese regulars from 275th Regiment and unknown to the Australians they now faced a battalion-sized force in well prepared positions.

The assault began at 15:35, with A Company beginning their advance into the rainforest with two platoons forward and one back. Meanwhile, B Company began forming up in single file on the right flank, also with two platoons forward in assault formation, while one remained in reserve at the rear. Each of the forward platoons covered a frontage of 100 metres (110 yd), with 4 Platoon—under the command of Second Lieutenant John Sullivan—on the left, and O'Halloran's 5 Platoon on the right. Company headquarters was located centrally, while 6 Platoon—commanded by Sergeant Butch Brady—was to the rear. Each platoon adopted a similar formation, with two sections forward and one back. From the outset the lead elements of B Company came under constant sniper fire from the trees, and from Viet Cong machine-guns that had not previously been detected by the Australians. Even as the company was shaking out they were engaged sporadically by a group of Viet Cong just 50 metres (55 yd) to their front, with one Australian soldier being hit before the attack began and later dying at the landing zone before he could be evacuated. B Company subsequently crossed the line of departure at 15:55, and two minutes later A Company began engaging the Viet Cong positions with small arms from their 7.62 mm M60 machine-guns and L1A1 Self Loading Rifles, and 5.56 mm M16 assault rifles in support.

As B Company moved forward, their left flank was engaged by a machine-gun from a small party of Viet Cong to their front, while sniper fire intensified. The Australians continued to advance with co-ordinated fire and movement, but were now receiving fire from three directions. Ten minutes after stepping off, B Company crossed the front of A Company, forcing them to cease their covering fire. Without support, the Australians were now assaulting a well dug-in and largely unseen Viet Cong force that was disposed in a wide arc. Penetrating the position, the Australian flanks were increasingly exposed to fire, while the dense undergrowth obscured the Viet Cong pits and reduced visibility to just a few metres. Both the lead Australian platoons were soon enveloped, as fire swept across the front of B Company from the Viet Cong engaging them with heavy machine-guns, claymore mines and light mortars. Meanwhile, Viet Cong snipers continued to engage the Australians from the rear, who unsuccessfully attempted to regain the initiative with small arms fire and grenades. The assault soon faltered with steadily increasing casualties.

The two forward Australian platoons subsequently lost contact with each other, while the left section of 4 Platoon was engaged by a 12.7 mm heavy machine-gun, and began to fall behind. The section on the right was also engaged by a machine-gun, and the frontage of the platoon subsequently broke. The section commander assaulted the Viet Cong position with an M79 grenade launcher, however he was unable to dislodge them. Meanwhile on the right, 5 Platoon pressed their advance, and they subsequently pulled further ahead of the rest of B Company. At 16:25, with 5 Platoon now 40 metres (44 yd) in front and also receiving machine-gun fire from its front and right flank, Mackay finally ordered the platoon to halt as he attempted to manoeuvre the company to regain control of the situation. 6 Platoon was ordered to advance through 4 Platoon to assault the machine-gun on the left flank, before linking up with 5 Platoon and continuing the assault. Brady subsequently directed his men to fix bayonets and charge the Viet Cong positions, yet the attack was soon cut to pieces by machine-guns which engaged them from the centre and left and it was subsequently halted behind O'Halloran's rear section. Brady then requested mortar fire in support; however, the need to request air clearance only resulted in further delay. By 16:45 B Company's assault had bogged down due to the strong Viet Cong resistance. All of its platoons were in contact and unable to move, while company headquarters had advanced behind the lead platoons and was also pinned down.

As the fighting continued, D Company remained in a blocking position to the north-east of the landing zone. Meanwhile, after inserting C Company into its blocking position to the west, the APCs from A Squadron had moved into a harbour around the tree line, from where they covered the flanks of the rifle companies in the rainforest. Not included in the assault due to the belief that the terrain was unsuitable for armour, in their location the APCs were occasionally hit by overshooting rounds, but otherwise remained out of the battle. This assumption was later found to be incorrect though, and the APCs would likely have been able to move through the dense undergrowth, while the firepower provided by their .50 calibre machine-guns would have been able to assist B Company, which was pinned down. Regardless, the armament of the M113s would have likely proven inadequate for attacking strong defences and bunkers, and their light aluminium armour was known to be vulnerable to heavy machine-guns and RPGs. With both A and B Company now heavily engaged, Townsend subsequently asked Murphy whether his APCs could move around to the right in another attempt to outflank the Viet Cong; however, a creek made the ground in that area too boggy for the vehicles and this proved impractical.[43] A close quarters battle then ensued, continuing until night fell with the Australians assaulting the Viet Cong positions using frontal tactics which resulted in heavy casualties on both sides.

Final assault and withdrawal overnight, 17/18 February 1967

Under orders from Townsend to press on with the assault as fast as possible, Mackay decided to switch the B Company assault to the right flank, ordering O'Halloran by radio to advance a further 30 metres (33 yd) in order to outflank the Viet Cong machine-gun and allow 6 Platoon to resume its advance on the left flank. However, the machine-gun was soon found to be located a further 30 metres forward than expected, and 5 Platoon would need to assault 60 metres (66 yd) across open scrub under heavy fire in order to silence it. As O'Halloran relayed orders for the assault, machine-guns and snipers continued to engage them intermittently, and the Australians continued to return fire with small arms and grenades. Again fixing bayonets, on order the Australians rose as one and were almost immediately hit with heavy fire, with the forward line disintegrating as a result. The left forward section under Lance Corporal Kerry Rooney then advanced directly at the machine-gun located to their front, firing as they moved. Rooney then charged the position throwing grenades but was shot and killed within metres of the Viet Cong position. Suffering several more men wounded, the Australian left flank again became pinned down.

Meanwhile, the right forward section under Corporal Robin Jones attacked the Viet Cong at close range, inflicting heavy casualties on the defenders with grenades and small arms fire. However, three previously undetected Viet Cong machine-guns subsequently engaged 5 Platoon, which succeeded in breaking up the Australian attack on the right flank with intense enfilade fire which killed three men and wounded five more. Of his section only Jones was left unwounded. For his leadership he was later awarded the Military Medal. The Australian assault stalled having covered just 25 metres (27 yd). Nearly half of the men in the forward sections had become casualties and the platoon stretcher bearer, Private Richard Odendahl repeatedly risked his life dragging men to safety, providing first aid, recovering weapons from the dead, and providing O'Halloran with information on the disposition of his platoon. For his actions Odendahl was also later awarded the Military Medal. Attempting to reinforce his threatened right flank, O'Halloran ordered the M60 machine-gun from his reserve section forward to support Jones while the wounded were recovered, however both the machine-gunner and his offsider were killed attempting to move forward. Surrounded by Viet Cong machine-guns and receiving fire from all sides, the lead Australian elements from B Company could advance no further against a determined and well dug-in force, and all attempts to regain momentum were unable to dislodge the defenders.

With the Australian and Viet Cong positions now too close to each other, O'Halloran could neither move forward nor withdraw. Artillery began to fire in support of the Australians, however it initially fell too far to the rear to be effective, and it had to be adjusted by the B Company forward observer, Captain Jim Ryan, himself under heavy fire. 5 Platoon was still in danger of becoming isolated and O'Brien now suggested he move A Company forward to assist B Company, however this was rejected by Mackay who feared the two companies clashing in the confusion. Meanwhile, O'Halloran called for the APCs to come forward to provide assistance, while the platoon sergeant—Sergeant Mervyn McCullough—guided a section from 6 Platoon forward to reinforce 5 Platoon, and begin evacuating the casualties. Bolstered by reinforcements and with accurate artillery covering fire O'Halloran now felt that he was in a position to extract his platoon. Yet at that moment two rounds from one of the howitzers fell short, and while one of the shells harmlessly exploded against a tree, the other landed just to the right of the 5 Platoon headquarters, killing two men and wounding eight others, including six of the seven reinforcements from 6 Platoon. Following an urgent radio call from O'Halloran, the artillery ceased fire. Shortly afterwards an RPG round hit the same area, wounding McCullough.

Townsend subsequently then reported that he was facing a force of at least battalion-strength with support weapons—likely D445 Battalion—while the level of proficiency indicated that it might also include North Vietnamese Army (NVA) elements. However, due to earlier warnings that the Viet Cong were preparing to attack Nui Dat that evening, prior to the start of the operation Graham had ordered Townsend to return to base that afternoon, and this restriction remained extant. Likewise, with Operation Renmark scheduled to start the following morning, A Company 5 RAR—then at Dat Do protecting the artillery—would also need to be released before nightfall, adding to the requirement to conclude the operation that afternoon. Regardless, this restriction had only served to make B Company's task all the more difficult, with Mackay facing demands to complete the action while at the same time not become decisively engaged and unable to withdraw his company. At 16:17 Townsend was ordered to prepare his battalion for a helicopter extraction which was due to begin an hour later, while at 17:15 he was ordered to break contact immediately, however this proved impossible as 5 Platoon remained in heavy contact. Mackay now estimated that he would be unable to get forward to support the beleaguered platoon for a further 30 minutes; however, by 17:50 he realised that the Viet Cong had moved between them and A Company. Yet even while the Viet Cong continued to heavily engage both A and B Companies, the remainder of the Australian battalion and the APCs were beginning to line up on the landing zone in preparation for returning to Nui Dat. The order was finally rescinded when it became clear that both companies were unable to break-off the engagement. Meanwhile, a number of bush fires were now burning through the area, detonating discarded ammunition and adding to the noise of the battle.

Initially the Australians had used their APCs to secure the landing zone at the jungle's edge, however with the infantry in trouble they were subsequently dispatched as a relief force. Three M113s from 2 Troop under Sergeant Frank Graham entered the rainforest shortly after 17:15; however, lacking clear directions to B Company's position 300 metres (330 yd) away, they fumbled around in the dense vegetation before locating A Company instead. Instructed by Mackay to head for the white smoke of the bush fire, in error the APCs then set out towards the most obvious smoke further to the south-east of B Company. A Viet Cong 75 mm recoilless rifle subsequently engaged the lead vehicle twice at close range, though both rounds missed, exploding in the trees nearby. Still unsure of B Company's location, Graham was unwilling to engage the Viet Cong position with heavy machine-guns for fear of hitting his own men, and the cavalry subsequently withdrew. Later it was discovered that the cavalry had likely been engaged by elements defending the Viet Cong headquarters. Meanwhile, due to the threat posed by the Viet Cong anti-tank weapons the remainder of 2 Troop then arrived under the command Second Lieutenant David Watts to provide added protection; in total 12 vehicles. A further attempt to reach B Company by the cavalry also failed however, after the A Company guide became disorientated in the thick vegetation. Mackay then threw coloured smoke, while Sioux helicopters arrived overhead to guide the vehicles to their position. B Company's casualties now amounted to seven men killed and 19 wounded.

Fighting their way forward, the M113s finally arrived by 18:15 and began loading the most badly wounded as darkness approached. The Viet Cong subsequently launched two successive counter-attacks, assaulting B Company from the east and south-east; however, both attacks were repulsed by the Australians, as they responded with small arms fire while Mackay called-in an airstrike. During the fighting one of the APCs was subsequently disabled by a recoilless rifle at close range, killing the driver and wounding the crew commander. A second round then struck the open cargo hatch, wounding several more men and re-wounding a number of the Australian casualties. A third round then landed nearby, as the M113s returned fire with their .30 and .50 calibre machine-guns. Under covering fire the Australians attempted to recover the damaged vehicle, yet it became stuck hard against a tree. With the Viet Cong threatening a further attack from the north-east, the Australian cavalry swept the area with a heavy volume of fire and were met by equally heavy return fire. By 18:50 the light was fading rapidly, while the bulk of 5 Platoon's more serious casualties had been evacuated by APC. However, with many of the Australian dead lying in close proximity to the Viet Cong positions, no attempt was made to recover them due to the likelihood of further casualties. Meanwhile, the damaged APC was subsequently destroyed with white phosphorus grenades to prevent its weapons and equipment from being captured.

Finally, by 19:00 B Company was able break contact and withdrew after a five-hour battle. Both sides then fell back as the Viet Cong also dispersed, evacuating most of their dead and wounded. Meanwhile, under covering fire from the APCs of 2 Troop, B Company boarded the remaining carriers, moving into a night harbour near the landing zone with the remainder of the battalion at 19:25, as the last of their casualties were extracted by helicopter. Mortars, artillery fire and airstrikes covered the Australian withdrawal, and then proceeded to pound the abandoned battlefield into the evening. That night the body of the dead APC driver was evacuated by helicopter, as American AC-47 Spooky gunships circled overhead, dropping flares to illuminate the battlefield and strafing likely Viet Cong positions, while F-4 Phantoms dropped napalm. The airstrikes then continued in preparation for a further assault by the Australians planned for the following day. Otherwise there was no further fighting that night, and both sides remained unmolested. Ultimately no attack was made against the Australian base at Nui Dat that night either, while no unusual activity was reported in the area.

Return to the battlefield: 18 February 1967;

After a tense night the Australians returned to the battlefield the following morning. At 09:30 on 18 February 6 RAR assaulted into the area on a broad front, with C and D Companies forward and A Company in reserve, while B Company and the APCs from A Squadron occupied a blocking position to the south. Anxious not to repeat the failure to follow up the retreating Viet Cong after Long Tan, from Saigon Vincent urged Graham to pursue D445 Battalion. Meanwhile, a large American force of over 100 armoured vehicles from the 2nd Battalion, US 47th Mechanised Infantry Regiment, supported by a battery ofself-propelled guns and helicopters from the US 9th Division, attempted to cut-off likely Viet Cong escape routes. Having deployed in support of 1 ATF earlier that morning from Bearcat, 42 kilometres (26 mi) north-west of Nui Dat, the Americans subsequently cleared an area along the line of Route 23, 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) north-east of the battle-zone. Although constituting an impressive display of combat power, the Americans had arrived too late to affect the outcome of the battle, and no contacts occurred before they were withdrawn the following day. Meanwhile, the Australians conducted a sweep of the battlefield only to find that the Viet Cong had left the area during the night, successfully avoiding the large blocking force while dragging most of their dead and wounded with them.

During the sweep one of the missing Australians—Lance Corporal Vic Otway—was unexpectedly found alive, having spent the night in close proximity to the Viet Cong after being wounded in both legs and falling just metres from the machine-gun he had been assaulting. Unable to answer calls from other members of his platoon for fear of being discovered, he was presumed to have been killed. Lying still for four hours, Otway had managed to crawl 70 metres (77 yd) to the rear after dark, before artillery fire and airstrikes began to fall on the area. Digging a shell scrape for protection from the American napalm strikes, he was subsequently wounded again by shrapnel. After first light he had continued to crawl back towards the Australian lines, but was confronted by a group of Viet Cong soldiers just 6 metres (6.6 yd) away. Otway attempted to fire on them, however his weapon jammed, and the Viet Cong had walked past him unaware of his presence. Continuing their search, the Australians then located and recovered the bodies of the six dead from 5 Platoon. Most had been burnt beyond recognition by napalm, while at least one had been stripped of his webbing and equipment.

Operation Bribie. (2013, May 30). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Operation_Bribie&oldid=557441992

Copyright Henry John Chisholm, 2013.