June 29 - July 5, 2014: Issue 169

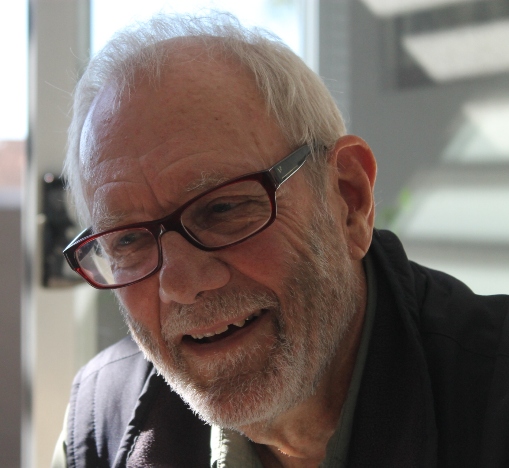

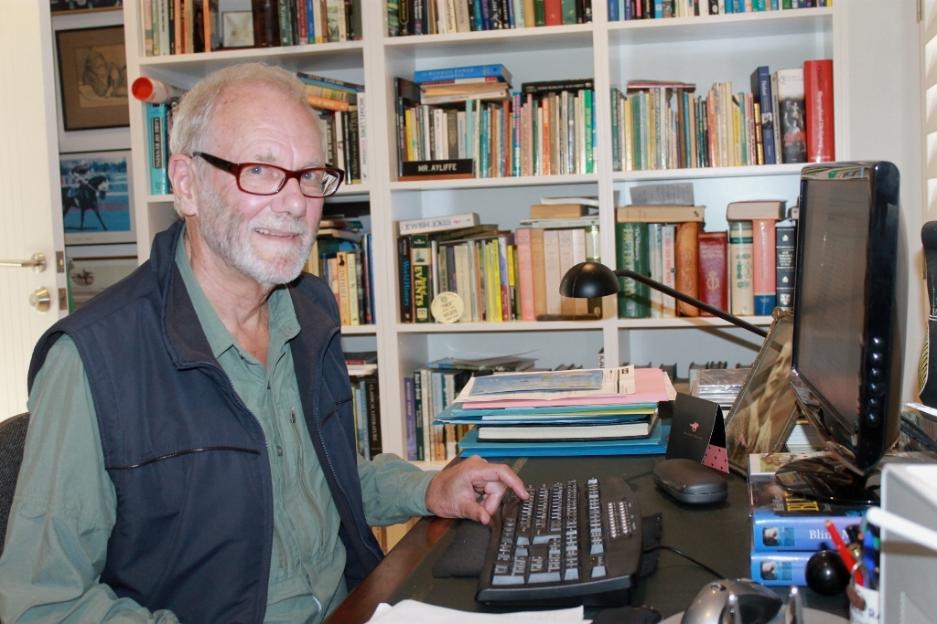

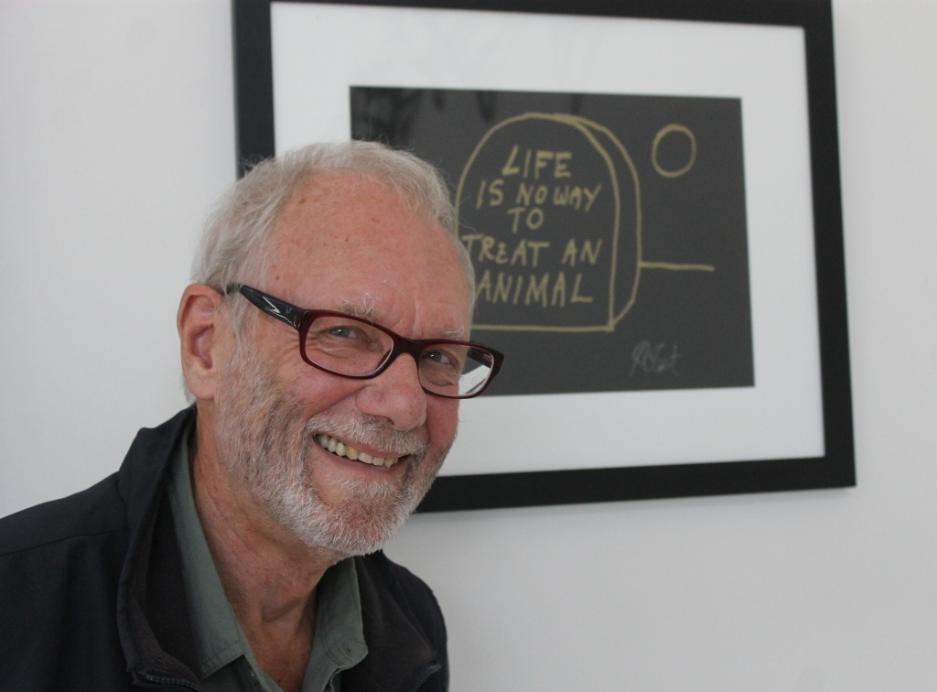

John Stephen Ayliffe

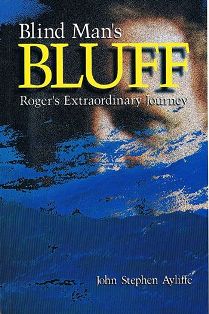

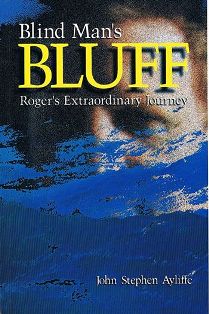

Having met John Stephen Ayliffe quite a few years ago, when he had just published Blind Man's Bluff - a wonderful biography of Roger McKenzie, blinded by meningitis at age 14 but determined to live a full and rich life regardless, John immediately seemed to share a few traits with Roger - determined to live a rich and full life pursuing and developing his own abilities to translate the human experience into stories that are written with truths kept at their core.

Committing yourself to any writing project requires a certain amount of bravery, if the genre is about people, even more so. For many writers it is a great love of people that inspires them to share insights many would simply keep hidden. The writer may shrug off this sense of nakedness with a certain 'people may choose to have this or simply pass it by - not glancing in' - but ultimately the writer is being brave, they are trying to give something - and will go hungry, become homeless, and devote years to working, working, working - to get near a final draft.

Mr. Ayliffe has a rich heritage of family writers, has 'always wanted to write'. Prior to becoming a full time writer he wended his way through the advertising world, at the top of the field for many years, creating a successful pathway to where he stands now...

When and where were you born?

In Sydney, at Maroubra, in 1943. I spent the first three years of my life there. My only memories of there are of when dad was down on the waterfront watching for submarines. One night mum got me underneath the table, as the alarms had gone off; I remember the two of us sitting under the table, and the blackout curtains.

In Sydney, at Maroubra, in 1943. I spent the first three years of my life there. My only memories of there are of when dad was down on the waterfront watching for submarines. One night mum got me underneath the table, as the alarms had gone off; I remember the two of us sitting under the table, and the blackout curtains.

AYLIFFE (nee Audrey Stephen) - August 22, at the War Memorial Hospital, to Mr. and Mrs. F. Ayliffe of Maroubra - a son (John Stephen). Family Notices. (1943, August 28).The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 16. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17862158

Where did you grow up?

My early years were at Ashfield, dad was in the bank there. I would get on the bus to go to Trinity Grammar. When I was about 11 years old dad said he was going back to the country, he was a country boy. He said I could either go to Orange High School or stay at Trinity Grammar, one of my great uncles wanted to pay for me to stay in the boarding school, and so that’s what I did.

My early years were at Ashfield, dad was in the bank there. I would get on the bus to go to Trinity Grammar. When I was about 11 years old dad said he was going back to the country, he was a country boy. He said I could either go to Orange High School or stay at Trinity Grammar, one of my great uncles wanted to pay for me to stay in the boarding school, and so that’s what I did.

What was that like?

I didn’t like boarding, hated it, and it made it difficult for me when I started excelling at athletics, I was a sprinter – there was something about being the ‘star’ that I found very difficult, but it was a good school. I did well in the things I wanted to do well in and badly in the things I didn’t think mattered.

The athletics – you have some Olympics framed photographs here – these are here because of your success there?

That’s the Golden Girls from the Olympics of 1956 - and was given to me by my mates I used to run marathons with, until I got two new hips, on my 60th birthday. They’re all signed. Dear old Betty Cuthbert, who developed multiple sclerosis, still signed it even though her signature may have been difficult for her to do.

How far did you go with the athletics?

I stopped after I left school. I didn’t think I’d ever quite get there. I discovered much later that the Western Sydney Athletics Club wanted me to join them; Marlene Matthews and Betty Cuthbert were part of that group, but I think inside I felt I had neither the ability nor the dedication to really get to the top.

What did you do when you left school?

All I really wanted to do was to write. There I was sitting at home at cold Blayney, where dad was the bank manager. In those days, 1960, the residence was behind the bank. Dad said to me ‘what are you going to do?’ and I said ‘ I want to write.’ He told me the school wanted me to go back on a sporting scholarship and I answered that I didn’t want to go back, I hated the school, or hated the boarding school part of it – this went on for about six weeks with dad getting more worried about me.

One day he came in and said ‘your uncle has been on the phone, he (Terry Southwell-Keely) had been a war correspondent, bullet in his typewriter, he was my surrogate father in Sydney, a very interesting and strong man, an Ernest Hemingway type, a man’s man – dad said, your uncle knows a man in Sydney who is going to pay you to write.

I thought ‘well I’m there then’. I jumped on the ‘rattler’ (we used to stick our heads out the window and pick the sparks up for a laugh). I hit Sydney and went in to see this man in a three piece suit with a carnation in his buttonhole, slicked back hair in a beautiful timber panelled office behind a great timber desk. He said ‘we’ve got a really good Copy-chief here, he’s written a couple of books John. His name is Hugh Atkinson. If he likes you, you will be his apprentice; but first off all you will have to be working in the Message Department.’

Which is how people started off.

That night I got home and couldn’t wait for Uncle Terry to come home because I had one significant question. When he walked in, got his scotch out, I said ‘what’s an advertising agency?’

That’s how I started.

It turned out that they’d employed a bloke to run messages two days prior top me. Because he’d started two days before me he declared himself the boss and I was the runner. So he stayed at the agency all the time and took all the briefs and worked out what had to be taken her or there and what had to be picked up from here or there. Meanwhile, how silly had he been, because now I’m out there, meeting the clients, who would want to talk to the young kid coming in, meeting the printers, I found out where all the Media was, where the Sydney Morning Herald was, where 2GB was, all that.

Six months later I’m working with Hugh Atkinson (Hugh was impressive, not the least that he had had published a novel! It was called Low Company). He’d give me odd lines to write – he’d write a headline and say ‘fill in the copy’ and then he’d go to the Newcastle Pub and get on the turps with his mate Ray Matthew, who was the poet, who I met through him. Most of the time I was protecting him; he drank a hell of a lot. He came back to the office, would pick up his telephone books, put them under his desk and use them as a pillow while he had a sleep.

Six months later I’m working with Hugh Atkinson (Hugh was impressive, not the least that he had had published a novel! It was called Low Company). He’d give me odd lines to write – he’d write a headline and say ‘fill in the copy’ and then he’d go to the Newcastle Pub and get on the turps with his mate Ray Matthew, who was the poet, who I met through him. Most of the time I was protecting him; he drank a hell of a lot. He came back to the office, would pick up his telephone books, put them under his desk and use them as a pillow while he had a sleep.

Ken Unstead, the boss, the three piece suit man, would stick his head in the door and say ‘is Atkinson in?’. I’d say ‘oh no, expecting him about three, maybe four.’ And of course his feet are sticking out from under the table!’

One day he said ‘I don’t want you to work here any longer; you’re going to go and work at Farmer’s Advertising Department where you’re going to learn selling.’ That’s where everybody starts; Leo Schofield started there.

They had this wonderful woman there, Zelda Stedman, who was known as ‘the dragon’; she was absolutely amazing. When I got there the first thing she said to me was ‘John, I’ve got something a bit unusual for you to do to start with, if you can pull this one off we’re going to get on very well. I want you to sell my car… it’s in the basement.’…and ‘Now John, don’t you wash it; I don’t want it washed, it’s never been washed.’

So I went downstairs, I’d only had my licence for about a year and hadn’t done much driving; I jumped into this Peugeot from the 1950’s that had the gear shift as part of the wheel. I rang my father and he said ‘go down Parramatta road’; so I looked up in the telephone book all the Peugeot dealers, drove down Parramatta road stopping at one after the other and ended up getting a pretty good price for her. But while doing this one of these guys said to me: ‘This car has never been washed and I explained that I was told not to wash it. He said ‘do you know why sonny; If we wash it the duco (the paint) will all fall off; have a look at this’; anyway, he scratched and a bit of paint fell off.

So that’s how I started there.

At Farmer’s you literally had to write a headline from men’s shoes to refrigerators to books. I didn’t get any women’s underwear, which would have excited me more at that age! I liked doing the books of course.

At Farmer’s you literally had to write a headline from men’s shoes to refrigerators to books. I didn’t get any women’s underwear, which would have excited me more at that age! I liked doing the books of course.

After about six months Zelda called me in again and said ‘John, I’ve got something else for you to do now.’ And I immediately thought ‘oh no, not another car.’ But she was giving me a column. I had a column in Friday’s Sun newspaper; it was called ‘The Young Man Shop’ column. It wasn’t much but I got to write a couple of paras - something that might interest young men and their girls.

What was in fashion? what was the first suit you wrote about?

My first job was actually what was called a ‘Stamina Suit’ – a very conventional school suit. Stamina was trying to sell these school suits to boys for when they got a job. In fact I think my first suit was a Stamina Suit.

At that time things were still pretty conservative – there were no jeans or anything like that. Fletcher Jones was the competition.

How long were you doing that for?

I did that for about a year and became a bit bored. I thought ‘Mr Atkinson has suggested that I do this to learn to sell retail, what would he think I should do now?’ I tried to contact him, he was near retirement by now, and away crocodile shooting with his mate Ray Matthew – I always thought that sort of stuff was wonderful…

Yes, very John Huston of them….

(John laughs) At any rate; I went to 2GB from there. Once again I was an apprentice, this time to try and learn Radio Copywriting – the trouble was the sort of radio copywriting expected then was very retail, similar to what we see today with “Price, Price PRICE!” – coupled with the man who I was apprenticed to thinking I was there to take his job, even though he was the boss and I was the apprentice, made life extremely difficult as well as no real expansion on what I’d already done.

There was a wonderful fellow there, who also wrote advertising. named Noel Judd, who was quite famous for writing and appearing in some of those very early radio plays; things like ‘Life with Dexter’ - he was a wonderful man; he taught me a lot of things.

What did he teach you?

He taught me about birth control. He taught me the withdrawal method; that was his big thing. (laughs) That’s the first conversation I had with him; ‘oh, by the way, you’re twenty, what has your father told you about this and that… what are you doing about…’ It was so funny.

At any rate, I left there; I needed to go to an advertising agency really, to become more creative, to become more rounded, as they say. So I worked through a couple of Advertising Agencies … I was a naughty boy really…walked out if I didn’t like it.

In those days we knew why we were at school, and this is a major difference between today and then; we were at school to get a job. And we never ever believed that there wouldn’t be a job. So we could have any job; and you could walk out and get another job. I probably shouldn’t have done that as much as I did, but I ended up where I wanted to end up. I thereby got to work with a wonderful Jewish Creative Director, Morris Hertz at a place called USP Benson; the ‘United Services Publicity’.

United Services Publicity was formed by three men from the war (WWII) who had been in the services together and when they came out they started an advertising agency together. They then brought in an English agency ‘Benson’. They were lovely people – Morris Hertz, although not one of those three, was the Creative Director. He was a very stylish man – lived in Paddington; he and his wife were good friends of Leo Schofield, so that connection came back again, I would see a bit of Leo through them.

Morris let me loose with television; television was pretty new then. What he taught me was that it’s about the idea; forget about everything else, it’s about ‘The Idea’. First you have to establish who you’re trying to talk to and then find an idea that will establish what it is about that will resonate with them; is it a trendy product, is it a useful product, is it a practical product, is it going to change people’s lives?

The most important message I think I got form Morris Hertz - which I never forgot - was that advertising has the ability to change people’s lives.

In a way I probably took that too far at times; there were times much later, when I owned an agency, that I felt that we could do really good things in a social sense. I drove my business partner crazy as I’d be going out looking for social interest campaigns; child sexual assault, wife bashing, drugs; all of those sorts of taboo subjects which needed some focus and because I thought advertising could change the world. Of course advertising can’t do this; what it can do is just another part of communication.

I used to think it was an information service prior but that was before I went to London. There it was confirmed for me that a good ad is no different to an encyclopaedia Britannica salesman knocking on your door to sell you the set, and the most successful people in advertising understand that. Attracting attention and getting into the customer’s heart requires lateral thinking - a good idea.

How did you get from USP to owning your own agency? Did you realise you were making someone else rich and keeping yourself poor?

No – all my life has been an accident in some ways. The only thing I really wanted to do is write. The famous Alan Bennett always declared that 95% of what he wrote he never showed anyone. I would be up around the 80% (laughs); and I’ve written stuff that almost got published then didn’t get published - all the usual experience that writers go through. So the one constant was that I wrote, always. But, I was also always scared that I’d get found out.

What, for being a sly poet?

Yes. I always felt that even when I owned the agency.

Why were you afraid of that?

Because I thought ‘well, these guys must know that I don’t want to write advertising forever – I want to write books, and one day I’ll get found out’ .

So you went to London?

I went to London. I discovered at that time that all the guys who wanted to get on were going to New York or London. We used to get what they called the ‘Monday Newcomers’ – you’d see these commercials and they were so much better than anything we were doing.

In what way?

The English ones were great ideas – you’d look at them and say ‘that’s incredible’. And then Doyle Dane and Bernbach in the States, who were the first big creative agency in the United States, did Volkswagen and at a time when Americans were buying tanks they had to sell a Volkswagen to people who wanted a car that could fit their family and the family next door in.

I’ll never forget their first ad; they took a whole page, it had a tiny little Volkswagen down the bottom and it said ‘Think Small’ – in big letters. It was a great ad. Then there was that wonderful Volkswagen in the snow ad; that is one of the greatest ads of all time. The Volkswagen in the snow; you’re looking at the snow, in the snow there is a shape like this (hand gestures the classic Volkswagen Beetle shape) and the shape starts to break away, the snow starts falling off, you hear an engine start up, and out of this mound of snow comes a Volkswagen; which drives over the snow and arrives at a big machine which looks like a big tractor. As it gets closer to it a Voice Over begins that says ‘in case you’re ever wondered how the man who drives the snow plough gets to the snow plough, he does it in a Volkswagen.’

It’s those sorts of things, I’ve done ads that have won awards, but I’ve never done an ad that would equal that ad.

Just as I’ve never written a book that would equal Catch 22 – the great Catch 22 – my favourite book of the 20th century. Scott Fitzgerald –The Beautiful and the Damned – or This Side of Paradise – you have got to have that ambition to do it as well as you can – to have such works up there to aspire to.

This was one of the reasons I had to get out of Australia; find out ‘how do you do all that?’ …’how do you get people to accept all that?’…that’s amazing…You see, it’s not just a matter of coming up with an idea, you have to be able to convince someone to do it, to spend a million on it.

How long were you in London for?

Three and a half years. I worked for the same agency three times. I found another Morris Hertz. His name was Joe Baker, he was a cockney – he was a print writer, didn’t understand television at all, the agency was called George Cummings, it was on Bond Street, it was run by an Australian. I was given a letter by a fellow called Ken Ballantine who was a director of USP. Joe took my portfolio, went through it, threw it on the floor and said ‘well, that’s a heap of sh*t , isn’t it?....but, like the way you talk, like the way you think, stick with me and I’ll make you a copywriter…in the meantime you can write television.’

So I got all the television stuff to write but he gave me other stuff to do too. My first print job took me six weeks to do and for one magazine ad; it was to sell the Alpha Romeo Guilia Super to women; this was going to go in Queen magazine and Nova, which were current female magazines of that time. It took six weeks because he kept knocking me back, ‘you could do better’. By this stage he was calling me ‘Baby J’; because I had discovered Carnaby Street; John Stephen of Carnaby street was a distant cousin, who owned 26 shops up there, and I was wearing a denim suit and hand-painted ties. This is 1965, the Beatles are happening.

I got the headline pretty much straight away – ‘Seduction Italian Style’ – that’s pretty easy really – but the copy, not so. The first line was ‘Introducing the Alpha Romeo Guilia Super. We think you will find it seductively different. Some cars treat you like a husband, this one treats you like a lover.’

That was the line he wanted – as Joe said, you know it when you’ve got it. It might have taken six weeks, but it set me up!

I was doing other stuff at the same time – a television commercial selling a lawnmower; went to Jersey and it rained for two weeks while we made this commercial (laughs).

I worked there three times. I met my wife there, who is Australian. I wanted to travel and so asked if I could have six weeks off after I’d been there a year. He agreed to it so off I went and came back. I did this again with Helen, we wanted to go to Europe together and hitchhike around, in those days you could do that. We went hitchhiking via trucks for about three to four months. Joe said ‘don’t know if I can hold your position open that long, but keep in touch’.

You went to the American Express office wherever you were when travelling then and could receive a telex. I got a telex just over three months later, we were in Amsterdam, which said ‘If you can’t be back here by the 15th Baby J your job’s gone.’

I said to Helen, we better get back. When I got back there it turned out that he’d employed someone who hadn’t worked out. It’s a very people business advertising, it’s chemistry; it’s not just a matter of whether you have the idea, it’s a matter of whether you have the chemistry to work with each other.

How did you meet Helen?

There was an Englishman in the agency who was taking out this Australian girl and he wanted me to meet her. We’ve now been married for 45 years – since 1969. We have four boys, eight grandchildren…Helen has kept me on the straight and narrow. Helen is my rock. People may say that all the time but Helen really is my rock – I’m sure I get away with the fairies a lot and Helen is the one who keeps us secure, she is the one with lots of common sense.

John and Helen - 2014

When did you come back to Australia?

In 1968 – we married in 1969. Helen came back to Australia and was going to return to London. Before she left, I wanted to take her to Paris, show her all the sights, not a fling of course; she was a good Catholic girl; and you could go to Paris for £8 then, airfares, accommodation, the whole lot, and I was earning £25 a week at that stage. Coming back in, when they stamped my passport, they said ‘you’ve been leaving the country too often and we can’t give you any more than six months here’.

Helen went back to Australia and I told Joe about this problem. No prob, one of the directors in the company said he’d get a friend of his, who was quite high up in some circles over there. ‘Knows Ted Heath.’ Well his friend fixed it alright- I was told that I had to get out of England within 3 months!

I rang Helen and told her I’m coming back. Joe did one of the most wonderful things that anyone has ever done for me in my career. He put a full page ad in the advertising magazine that had a cartoon drawing of me in my denim suits and hand-painted tie being kicked up the **se by a bureaucrat with Union Jack trousers on: with the headline ‘One of our better copywriters is being transported’ – basically it was saying that the job is open.

Joe said ‘now Baby J, word of advice; pick out three or four places that you think you might like to work and send that to them.’

So I wrote ‘John Ayliffe – coming soon’ with a phone number and sent it on to three agencies in Sydney. They all offered me jobs – the first one didn’t work out, it was a bit like a Public Service, and I was there for six weeks. A wonderful man employed me, I liked him very very much but they wanted me to work with him to try and change the culture and I couldn’t handle it.

I was having trouble coming back because I actually felt like I didn’t want to be here – I wanted to be there – London was where it was all happening. I was taking drugs to try and keep my head together. I ended up working for all three of those Creative Directors.

I worked for Leo Schofield at Jackson-Wain which then became Leo-Burnett. There were some wonderful people there; some of the classy people that I’d found overseas ended up there, it was a really good agency. And Leo of course is a master of style, he’s extraordinary.

I only worked there for about 15 months or so. I was employed by Leo in the morning and by another fellow called Vic Nicholson in the afternoon. Vic Nicholson was on the New Inventors, for those who remember that show, he was the marketing guy on there. That was difficult as they both felt I was working solely for them and I couldn’t be the servant of two masters.

After about 15 months Jacqui Hughie, who was at Compton and Australia’s first really high flying advertising lady, and with whom I’d had a frank conversation about not being able to settle back in and taking drugs to cope etc, rang me and said ‘if you aren’t settling in Sydney – what about working in Melbourne?’

I said to Helen ‘this could be the back door,’ and we went to Melbourne. We were there for a couple of years and returned with Helen pregnant with our first child. I went back to Compton and worked with Jacqui for a while.

I was still having trouble trying to sort myself out so I then went freelance – was one of the first freelance copywriters in Sydney.

I did this with another fellow who was a very good Director and Producer in television and radio. Peter Brett. I was mostly working weekends – I’d get a call on a Friday afternoon, go in there and there would be a Creative Director who would be at his wits end, usually drunk, he had a terrible failure that morning, gone to lunch and the client has knocked everything back and wanted the job done by Monday morning.

I had a sabbatical – I decided I had to pull myself together. We had saved enough money for me to not work for a year. We had always wanted to live up here (Pittwater) – we were living in Mosman then. Helen found a place in Avalon, a little cottage – we had two kids by then.

I then cold-turkeyed myself, got my act together.

About nine months into that sabbatical I got a phone call from one of the agencies that I’d done a lot of work for which went like ‘have you woken up to yourself yet?; when are you coming back into the business?’

He said ‘can I come and see you?’

He came down the next day and said he wanted me to be Creative Director. I explained that I was trying to write a book and didn’t feel I could go straight back into the business – he said ‘well, come and work three days a week and have two days for your book.’

What was this first book you were writing about?

It was a traditional ‘This Side of Paradise’ type of book – a coming of age – a young man trying to find himself, the subject matter of so many first novels.

What was Avalon like when you first came out – when was that?

1975 – We weren’t on the sewage. That was the first thing I noticed (the second thing was getting Golden Staff; it was probably from the sea – I was surfing most mornings – and I remember the doc telling me if we made that public he’d be sued! Such is politics). Fortunately, within a year or so we were put on the sewer. Anyway, I’d be down on the beach every morning, in the dark; there was a little group of us and all surfing with an innovative board and we called a Belly Bogger that one of the guys had invented; Dick Ash, he made Okanuis as well. We’d all stand on the edge of the pool until we could just see the shape of a wave and jump in. by the time we got out there it was light enough to catch a wave.

1975 – We weren’t on the sewage. That was the first thing I noticed (the second thing was getting Golden Staff; it was probably from the sea – I was surfing most mornings – and I remember the doc telling me if we made that public he’d be sued! Such is politics). Fortunately, within a year or so we were put on the sewer. Anyway, I’d be down on the beach every morning, in the dark; there was a little group of us and all surfing with an innovative board and we called a Belly Bogger that one of the guys had invented; Dick Ash, he made Okanuis as well. We’d all stand on the edge of the pool until we could just see the shape of a wave and jump in. by the time we got out there it was light enough to catch a wave.

I went back to Advertising and it wasn’t long before it was five days again. They then employed a fellow called Terry Carr who ended up being my partner in the business This again shows how chemistry works – I was the Creative Director and Terry was the man in the suit. It was already named ‘Pemberton Advertising’.

It was owned by the financial arm of Guinness breweries – those were the days when these guys in England were looking for investments that suited their lifestyles; these financial entities would buy everything from trout farms that didn’t work to orange groves that didn’t work to advertising agencies that didn’t work. They bought an agency called ‘O’Brien Publicity’, which was the second oldest agency in Australia; Pemberton was the second oldest agency in England, and they’d bought that, and changed the name to ‘Pemberton’.

There was an old fellow who had been in O’Brien for all his life who needed Terry and I. Terry and this fellow went off to meet the clients in England - I get a phone call about three o’clock in the morning and Terry said “John, these guys were going to sell the agency (to Saachi and Saachi!). So we’ve said ‘can we buy it?’ and they’ve said ‘yes’”

I said “oh, right – ok.” – it’s three o’clock in the morning – Terry says to me, “John, I can’t do it without you, can’t do it.” So I said “Ok mate, whatever you reckon.”

I hang up – Helen wakes up; “who was that?” - I said “Don’t worry, it’s fine, it was Terry.” – “Terry! He’s in London – what’s happened?” – I said “Oh, I think we just bought Pemberton.” – “We what?!!” – All the lights go on, alarms would have gone off if there had been an alarm – I said ‘darling, don’t worry, we haven’t signed anything yet.’ ‘Oh, that’s all right then.’

They were wonderful, they allowed us to buy the business out of Profits over about four years. In one sense that was really good, in another sense we’d bought a broken down agency; where were the Profits going to come from? (Work, bloody hard work and a modicum of luck; in buying Pemberton we owed $4 for every $1 we had, but that’s where good wives and life-partners come in, with their trust!).). And here am I, still that innocent – ignorant? - lad who had hoped he wouldn’t get found out?’… and had once asked ‘what’s an advertising agency? For me, at the end of the day it’s Faith – it all goes back to that to me – it’s Faith. Life is Faith.

How long did you do this?

We had 10 years in the sun, we had 10 really good years – we built up a pretty successful business.

Did you have some award winning ads during that time?

We did. But the ones I treasure most were the ones we did in the social welfare area. The Child sexual assault one about a father picking up his daughter and taking her home to molest her ran in America. The headline was ‘It’s often closer to home than you think.’

Another was ‘No Excuses Never Ever’.

That would have been very difficult to do?

That was tough. The little girl who played the part was just absolutely amazing. The guy who played the father was amazing because he’d been molested as a kid. He said ‘I want to put something back – I want to fix those ...tards’.

I won cinema awards too – I won awards for things you shouldn’t win awards for and wouldn’t these days - cigarettes.

Out of all those you did do, which were your favourites and why?

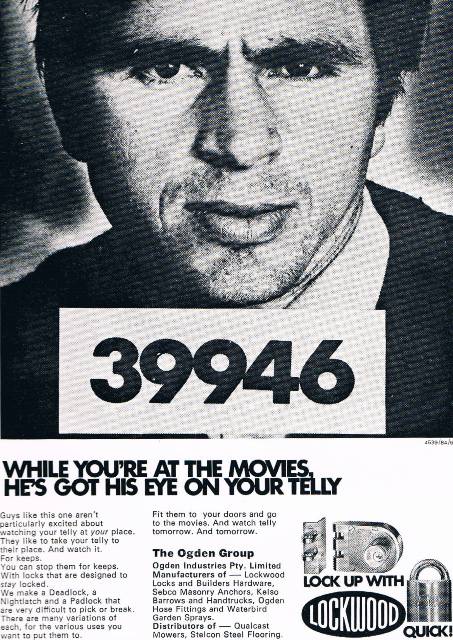

Probably a print campaign for Lockwood locks in which we used criminals – I sent a photographer to go along the waterfront with a mission to find crims, and of course at that stage Australia had one of the worst waterfront criminal problems in the world.

Probably a print campaign for Lockwood locks in which we used criminals – I sent a photographer to go along the waterfront with a mission to find crims, and of course at that stage Australia had one of the worst waterfront criminal problems in the world.

There were headlines like ‘Guess who’s coming to Dinner?’ and ‘While you’re watching the telly he’s got his eye on your camera’ with the payoff line ‘Lock Up with Lockwood – Quick!’

I’m prouder of the social interest ones because it did prove that advertising could do more than con people into buying bikes or something.

It must have been difficult to be working on those kinds of advertisements though – what years are we talking of?

Early ‘80’s.

That would have been fairly ground-breaking then; people didn’t discuss these kinds of subjects openly, let alone run advertisements so confronting.

It sort of was I suppose, yes.

We made a lot of money out of retail during that period – and were a bit ground-breaking there as I thought we could bring the kind of ideas that you could put on to brands into the retail area. We launched a jewellery chain called ‘Goldmark Jewellers’.

My line was ‘Your heart is just around the corner at a Goldmark Jewellers store’ (which wasn’t bad, considering they began with 3 stores in Sydney – within four years Goldmark was all over Australia, with over 100 stores).

I used these wonderful singers like jazz singer Kerry Bidell. I was quite proud of that and proud of the fact that the man who came to see us, a South African man, a Johannesburg Jew; Manfred was a wonderful man who was quite different to the Apartheid-loving Afrikaans.

Manfred had explained that the mark-up in jewellery is astronomical, he said it’s all about show for dough – meaning it looks fantastic but isn’t what it seems. So there was the opportunity, to drop the prices. I was quite proud of Goldmark – it wasn’t always creatively fulfilling but, we had 35 employees and I was getting to do a lot of these really good things via the government – the drug ads and subjects alike that, so as far as I was concerned it was all working; everyone had a job, the kids were being educated.

Ten years later – what were you doing then?

That’s when I wrote Blind Man’s Bluff. I’d met a young blind fellow, Roger McKenzie, and my uncle Terry Southwell-Keely, when he retired he didn’t retire – he went and worked as PR Chief of the Deaf and Blind Institute for Children. He rang me and said ‘John I need some help. I’ve got this really smart guy here…”

That’s when I wrote Blind Man’s Bluff. I’d met a young blind fellow, Roger McKenzie, and my uncle Terry Southwell-Keely, when he retired he didn’t retire – he went and worked as PR Chief of the Deaf and Blind Institute for Children. He rang me and said ‘John I need some help. I’ve got this really smart guy here…”

I went and met Roger and he had this great idea to put together a charity concert to raise money for the Institute by putting on the first ever Country Music Hall of Fame concert. He’d get together all the great country music singers; Slim Dusty, Reg Lindsay, Reg Poole, all these people; I remember all these names he rattled off, and the concert would be in Sydney. He needed help to get people to attend. There was no money in it for us; it was a bit before the social interest stuff we were doing but one of the charity things Terry and I decided we should do. Any good agency will do a certain amount of charity things, put something back, we always did.

The concept we came up with was to use the Australian flag and we put all these famous names in the stars and stuck it on buses and posters – worked gangbusters, filled the place, had to have a second concert.

It worked well until Terry got a phone call from one of his counterparts in Canberra, who worked for the Prime Minister’s Department as Press Secretary, who said ‘you’re in a spot of trouble; you’ve defaced the flag.’

So I’m dragged over the coals – anyway, it was all too late, the concerts had already run – it was for the Institute, after all - and they let us off but it was a bit nasty for a while. Terry would have me up in his famous Rugby Union Club whenever he wanted to have a serious talk with me – he was right on top of me, all the time, - and this was one of those times; he said ‘we can get sued, you can be sued and end up in gaol, defacing the flag is the equivalent of burning it’.

So, that’s how I met Roger. Ten years later, I am writing his story.

So you became a member of the Palm Beach and Whale Beach Association? And how did you get involved with the Whale Beach Surf Club?

I went to school with Richie Stewart who called me one day and asked if I’d work the beach with Ian Shepherd – Ian is still Channel Nine’s Sales Director –for the Big Swim that’s held each year; interviewing competitors as they come in. I’ve been doing that for about seven years now.

John interviewing Councillor Jacqueline Townsend - Mayor of Pittwater - The BIG Swim 2014. A.J.G. pic.

What’s the best thing to you about getting involved in that fundraiser swim?

Giving something back to the community – community to me is everything. I became a Catholic in 1976 – I was very involved in the church when younger, was a server at school, Trinity is C of E, but had walked away from it. I was always searching, looking for something.

What caused the change?

Pope John XXIII – he was the Pope John who changed the Catholic world. His first speech in the Vatican stated ‘there are too many Christians outside the Church.’

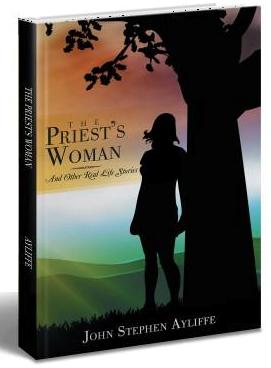

How do you get them back in again? What he did, in very simple terms, was to move the Church from a religion of fear to a religion of love. I didn’t pick up on that until 1975, that huge shift. My book The Priest’s Woman is all about keeping the Faith in spite of the Church.

To me Pope John he was communicating that the people come first.

What was it like writing Blind Man’s Bluff? Roger sounds quite feisty and determined to do anything anyone else can do…

He was (sadly, Roger died a few years ago). Roger said to me ‘if you’re going to write my story you have to tell it as it is’. So I honoured that – I kept it true. He did some amazing things; that Prologue when he goes against Rob Brown who is his skipper, and gets up on the yacht in the middle of a storm, in some ways epitomises his need to conquer fears, even if he put the others on that boat in that race at risk.

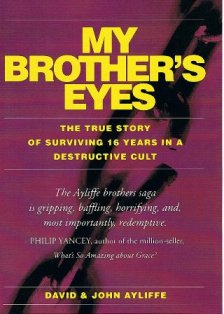

The book you wrote with you brother – My Brother’s Eyes – how did that come about?

After I’d finished writing Roger’s book was when I started querying the church – the capital ‘C’ church. I spent a lot of time talking to Morris West, who to me is one of the best writers in the Catholic tradition. Just great – The Shoes of the Fisherman – Clowns of God – he was a wonderful writer and a very kind old bloke, he helped me a lot. I started writing stories about the struggle believers have with the duplicity and ongoing crimes of their Church. This is the work that became ‘The Priest’s Woman and Other Stories’. They’re all pretty close to truth – they’re stories I’ve picked up over twenty years – for instance; one day a friend, a lapsed Catholic, went to live with a guy in a motel over the ranges and the next time I saw her she said ‘John, you know we’ve got these two people who have been meeting at this motel once a week for the last 10 or 12 years. He’s a priest, she’s a teacher.’

After I’d finished writing Roger’s book was when I started querying the church – the capital ‘C’ church. I spent a lot of time talking to Morris West, who to me is one of the best writers in the Catholic tradition. Just great – The Shoes of the Fisherman – Clowns of God – he was a wonderful writer and a very kind old bloke, he helped me a lot. I started writing stories about the struggle believers have with the duplicity and ongoing crimes of their Church. This is the work that became ‘The Priest’s Woman and Other Stories’. They’re all pretty close to truth – they’re stories I’ve picked up over twenty years – for instance; one day a friend, a lapsed Catholic, went to live with a guy in a motel over the ranges and the next time I saw her she said ‘John, you know we’ve got these two people who have been meeting at this motel once a week for the last 10 or 12 years. He’s a priest, she’s a teacher.’

I never forgot that – I talked a bit more about it with her and thought, there’s a great story there; a great story of heartache, of the ridiculousness of celibacy; there is nothing biblical about celibacy, it was brought in because the popes were making too many children all over the place and there were problems of heredity – the Church hangs on that ‘give yourself unto God’ – so that was the first story.

There were then other ones; a man who was gay and went into the priesthood to try and conquer the fact that’s he’s homosexual – which is your genes, not a disease or condition.

The book opens with a confession – I was sitting in a pub in Dublin and on the television was this young girl confessing to the interviewer that she is a good Catholic, has seven children, and has a husband who is drinking too much and can’t keep a job and so she is working as a prostitute to support them all. They are these kinds of stories, human interest stories…

Were you trying to write a holy book in The Priest’s Woman, a book about people’s spirituality?

People tell me this is what it seems like to them; that this is what it leaves them with. I hoped to do that. If I didn’t think it could do that I would not have published it.

I couldn’t get a publisher for that book, my publisher in Melbourne, who did My Brother’s Eyes, wasn’t game to do it – so I basically did it myself. I managed to place it with Ex Libris in America – they did hard copies and paperbacks and put it on Kindle, and did a really good job with the book. It may find a publisher here at some point.

So My Brother’s Eyes?

I was writing The Priest’s Woman stories and my brother had had his family in a cult for 16 years. He was not allowed to talk to us; mum would ring up and he wouldn’t talk to her, he lived in fear, abject fear that if he did anything wrong his Pastor would kill him. Violet Pryor – how ironic is that! On the cover of the book it says ‘if you ever leave me I will kill you!...God has informed me that the Lord’s Anointed is the chosen one and the purpose of the end-time ministry is to prepare the Bride for the coming of the Bridegroom..’

How frightening!

Yes, it was horrific. He came out of the cult, he’s ten years younger than me, and was having trouble, as you would expect, getting back into the real world. All his kids were born in the cult, all named by the cult leader, he was having trouble. I said to him one day ‘mate, you are a writer too – we’ve come from a whole line of writers’, Virginia Woolf is a relative, mum’s cousin, who was Virginia Stephen – which is why I’m John Stephen Ayliffe – he’s David Stephen Ayliffe ….there are many writers in the family…

Yes, it was horrific. He came out of the cult, he’s ten years younger than me, and was having trouble, as you would expect, getting back into the real world. All his kids were born in the cult, all named by the cult leader, he was having trouble. I said to him one day ‘mate, you are a writer too – we’ve come from a whole line of writers’, Virginia Woolf is a relative, mum’s cousin, who was Virginia Stephen – which is why I’m John Stephen Ayliffe – he’s David Stephen Ayliffe ….there are many writers in the family…

He’d started life as a journalist so I said ‘write it down, get it out of your self’. That’s what writers do – don’t we - write to get it out of ourselves – ‘what is the purpose of life and the meaning of death?’ Isn’t that what writing is about?

So he began writing and showing me stuff, and I thought ‘hang on, this is my story too.’

So I did what writers should do and investigated what was out there – and there were thousands of books on cults, most of these badly written, fragmented, probably because people are so emotional after such an experience that they can’t get it out. But there was a story here, through David’s eyes and my eyes – this was a railway track – this was happening to him and this was our reaction, this was also happening to us. And so that’s why it’s called ‘My Brother’s Eyes’.

We wrote it together.

Did it bring some healing for your brother?

Oh yes. He’s pretty remarkable. He works as a Carer – he still has his family, has grandchildren. We (writing the book) went away a few times to a cabin in the bush in Victoria, going away once for a week, we didn’t see another soul, just drank good wine and worked on the book, made dinner together, two brothers, how good is that?. At the end of it he said ‘I can’t do any more’ – he’d reached the end of his tether- he handed it to me, said I’d have to do the final edit. I said ok and then found out I had cancer – non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

I said I can’t do it, can’t concentrate for more than 15 minutes. So I put it aside and while I was going through six months of chemotherapy I found that The Priest’s Woman was really alive, but only for five and ten minutes at a time. I’d write these bits down and then I’d go to sleep again.

At the end of all that I had all these notes that gave me a shape for a book.

The architecture?

Yes, in one way. But more. One of the things was with this; there was a writer named Ruth Bedford, who was mum’s first cousin, and Dorothea Mackellar’s mate, they travelled together; Cousin Ruth was also a writer and when I was a kid mum would take me to visit. We’d go into this darkened room, she had subdued light all the time, and was surrounded by books, and she would say to me, always, ‘what do you want to do John?’ and I said ‘I want to write’. She would say “John, don’t write until you’ve got something to say.”

I never forgot that – and that is perhaps why I’m not a commercial storyteller, I have to keep it real, true.

We put the book together and sent it off and one day David got a call from a bloke called Gary Eastman. David phoned me and said you have got to ring John Garratt Eastman; so I did, and he said “John, I hope you haven’t gone anywhere else with that book – I picked it up last night and finished reading it at 10 o’clock. I’m sending you an air ticket, I’ll give you an advance, I’ll hire publicity, we’ll do a good job for you, when can you come down?’ (To Melbourne). So, that was that.

How did you get through having cancer?

Faith. And not just in God, I’ve been blessed with some very good doctors. When I talk about Faith I mean …well, in my very first marathon, I was running along with two guys, and about the 35 k mark I crossed myself, involuntarily, and the guy running beside me said ‘do you think that helps?’ to which I answered ‘I don’t know, but I’m giving it a go.’

I pray every day and certainly was during the cancer experience; it was morning and night then and with a rosary, which is a meditation.

Was there a heightened or stronger sense of being in communication with God during that time and by doing that?

I find that very hard to answer. I have come across people whom I would describe as ‘gone with God’ and who have said to me ‘God saved you’. I’m sure there’s a very deep spiritual side to this, and a very prayerful side and I’m sure that God played a role there somewhere, but I don’t discount modern medicine. Then I realised, after quite some time, that that is God too.

There’s a great book by Paul Davies called ‘The Mind of God’ a title which comes from the last line of ‘A Brief History of Time’ where Stephen Hawkins says ‘and then we’ll know the Mind of God..’

Which is also from the Bible…

Paul Davies is also a nuclear physicist and what he’s saying through his thesis in that book, is that everything has always been there, it is just gradually being given to us with evolution. He makes wonderful statements, my favourite… ‘How come there’s only one Mozart 21st ?’ and ‘how come Mozart did everything in 10 years?’ or something like that.

Mozart was an imbecile, worked flat out for 10 years, and then was an imbecile again – what happened? Anyway, religion, it’s Faith but it’s also a mystery.

The icons book – how did that come about?

To start at the end; it needed a Medici and found its Medici in Peter Montgomery. I don’t believe there is a publisher in Australia who would have produced that book like that – it’s high quality.

What was your brief?

It all started in the Palm Beach and Whale Beach Association. I had been on the Committee for a long time, and my friend Bryce Ross-Jones was still there, as Vice-President. . At the end of the bi-centenary year they published a book, Palm Beach 1788-1988, which is filled with interesting information, and they wanted me to update that. I had been involved in a lot of the historical stories they wanted to put together but I had also been doing a lot of historical research along another vein.

I was standing up the top of Sunrise Hill one day and looking at it all, and thought ‘you know, I bet that was once an island’; and went and investigated and found this to be true. I thought ‘gee, there’s a really interesting book here, it stems from the aborigines right up to present times’. Then I thought, how come this place didn’t turn into Bondi? How did it survive like this?

![]() So I went and talked to some local people, many whose families went way. Laurie Seaman, the people at Currawong. I went into it further, found Tench’s notes and original map of up here which says things like ‘too rocky’ , ‘no place for boats’, so that’s how it all started. One day Bryce went to see Peter Montgomery, told Peter about our discussions about my idea of a coffee-table book that had a good story, would make this place sing. Every story has to start somewhere and what had saved the Northern Beaches was Governor Phillip’ He was brought up here by longboat after Tench had been here, came with Collins and a surveyor, and there are two lines, one of which was ‘this place is useless; it’s high places are fit only for birds’ and the other of course that he found Pittwater ‘the finest stretch of water’ he had ever seen and so named it ‘Pitt Water’ after the young and current English Prime Minister of then whom he had a great regard for, especially because at that time he was working to end slavery. Pitt was up against a lot of the Westminster parliamentarians who were slave owners – James Stephen was his lawyer, who wrote the White Paper at the end of the day, that did the trick.

So I went and talked to some local people, many whose families went way. Laurie Seaman, the people at Currawong. I went into it further, found Tench’s notes and original map of up here which says things like ‘too rocky’ , ‘no place for boats’, so that’s how it all started. One day Bryce went to see Peter Montgomery, told Peter about our discussions about my idea of a coffee-table book that had a good story, would make this place sing. Every story has to start somewhere and what had saved the Northern Beaches was Governor Phillip’ He was brought up here by longboat after Tench had been here, came with Collins and a surveyor, and there are two lines, one of which was ‘this place is useless; it’s high places are fit only for birds’ and the other of course that he found Pittwater ‘the finest stretch of water’ he had ever seen and so named it ‘Pitt Water’ after the young and current English Prime Minister of then whom he had a great regard for, especially because at that time he was working to end slavery. Pitt was up against a lot of the Westminster parliamentarians who were slave owners – James Stephen was his lawyer, who wrote the White Paper at the end of the day, that did the trick.

Philip had refused to leave England until all the women had all the stuff that women would need; his main issue was ‘there will be no slavery in this land’. That went onto to be his first proclamation, upon arrival in the new colony. Those transported were prisoners, they weren’t serfs or slaves; when as a criminal someone had served their time they would be as free as anyone else.

So there was a book; put all that together and we might have something, something worthwhile. I loved the fact that, thanks to that great and compassionate man, I could say ‘and nothing happened for a hundred years.’

They tried to flog off the land and no one came – it wasn’t until 1912 when the first successful land sale took place, the Napper Estate that covered most of the two far Northern beaches.

Then war broke out, so, with little building it was back to nature. Then came the Great War and it wasn’t until the 1920s – 130 years after that first Sydney settlement – that Buildings such as Jonah’s and the Seaman house began to take shape. icons tries to capture that story, but as I say at the end of all my books – I can only go so far, if you want to know more, here’s a list of books and there are plenty of others.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater and why?

Barrenjoey and McKay Reserve – which is where our first house up there was and that’s where we had the big battle to keep the road open. Zealots wanted to close the road and it was a major fire break. It is a place where you can think you’re actually in a National Park – so McKay Reserve would be one of my favourite places.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

To thine own self be true.

That was written in ecclesiastical gold behind the altar of St John’s church Ashfield – when we’d go out walking mum would occasionally take me in there, and she’d sit for a while.

Copyright John Stephen Ayliffe, 2014.

John Stephen Ayliffe – Artist of the Month – July 2014

John Stephen Ayliffe has published three books prior to the icons project. Blind Man's Bluff is the story of a blind man who took on the world. Hitch-hiked India, swam in shark-infested waters, sailed the forbiddingly challenging Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, and all while conducting a business aimed at keeping the media on its toes.

John Stephen Ayliffe has published three books prior to the icons project. Blind Man's Bluff is the story of a blind man who took on the world. Hitch-hiked India, swam in shark-infested waters, sailed the forbiddingly challenging Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, and all while conducting a business aimed at keeping the media on its toes.

John co-wrote My Brother's Eyes : The True Story Of Surviving 16 Years In A Destructive Cult with his brother, David, who survived almost two decades in a destructive cult, a life episode that tore the brothers apart. Read a sample here

John co-wrote My Brother's Eyes : The True Story Of Surviving 16 Years In A Destructive Cult with his brother, David, who survived almost two decades in a destructive cult, a life episode that tore the brothers apart. Read a sample here

In 2012 The Priest's Woman: And Other Real Life Stories was released

Keeping the Faith in spite of the Church: True love triumphs against the Catholic Church’s most outdated law, a gay priest is hounded by the Vatican’s “Secret Police”, a courageous young journalist takes on Nazi Germany and exposes the Pope who aided Hitler - Composed over three decades my stories from real life are about the struggle between Faith and organised religion, its hierarchical duplicity, shameful denial and lack of justice and compassion. “I’d love to be a Catholic, but the Church is in the way,” says Jimmy, who wants to make love not war.

“The Priest’s Woman” is an anthology that, as a whole, tells the story of modern Catholics, and how their compassion and goodness is being stifled by the hypocrisy and archaic mindset prevalent in the Church. Ayliffe’s work will intrigue and compel readers who wish to gain a deeper insight into the issues facing Catholicism today.

For more information on this book, interested parties can log on to www.Xlibris.com.au

For more information on this book, interested parties can log on to www.Xlibris.com.au

John’s books are also available on Kindle (John Stephen Ayliffe gets people there instantly). And he is happy for people to contact him for copies at johnstephenayliffe@bigpond.com.

In March 2014 icons: a celebration of Sydney's far northern beaches by John Stephen Ayliffe with Terri Ayliffe was released through the support of Jonah's Restaurant, Whale Beach.

The book is a celebration of an iconic part of Sydney – the far Northern Beaches. Pittwater continues to be a haven for artists, writers, historians, photographers and film makers, many of whom have visited Jonah’s over its 85 years. “Every picture in this book tells a special story - this book owes so much to the locals” says Mr Ayliffe.

With double page spreads of beautiful pictures intertwined with historical notes, this is a must for every Pittwater home and a great gift for visitors to ‘God’s Country’; Pittwater!

Copies of the book are available to guests of Jonah’s, Whale Beach. We share a sample here this month.

John Stephen Ayliffe is our Profile of the Week for Issue 169 and shares insights into a successful career in advertising and the evolution of a constant theme throughout his life of ‘wanting to write’.

John and wife Helen have called Pittwater ‘home’ for four decades. The couple have four boys and eight grandchildren.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()