October 5 - 11, 2014: Issue 183

John Gould's Extinct and Endangered Mammals of Australia

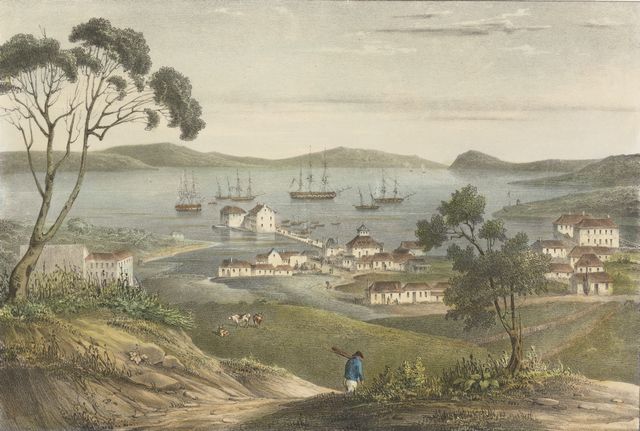

Hobart Town & view of the Derwent River, Taken from Signal [hut] Mt Nelson, Van Diemen's Land, [1819] Digital Order Number: a3464071 - State Library of NSW picture.

John Gould's Extinct and Endangered Mammals of Australia by Dr. Fred Ford

Between 1850 and 1950 as many mammals disappeared from the Australian continent as had disappeared from the rest of the world between 1600 and 2000!

These species, along with the instantly recognisable Tasmanian Devil, Kola and Common Wombat, appear in John Gould's Extinct and Endangered Mammals of Australia as animals long gone or with an increasingly tenuous grasp on existence.

Zoologist Fred Ford takes up the story of 46 Australian mammals that were documented by John Gould in his 1863 landmark three-volume work, The Mammals of Australia. Today these species are threatened or extinct but thrive in the lavish colour plates reproduced in this book from Gould's original publication.

Fred Ford provides the reader with fascinating, and often poignant, stories of European attitudes and behaviour towards Australia's native fauna and connects these to the animal's fate today.

Much of this behaviour, from the bounty hunting of the Thylacine in Tasmania to Koala fur-trading and the 'wallaby drives' in the late 1800's, would today be considered shameful. Other threats to our native fauna, such as the introduction into Australia's ecosystem of rabbits, foxes and cats and intensive pastrolism, persists today.

Fred Ford charts how these changes to the continent since 1863 have caused the wholesale loss of populations of native mammals and the extinction of many species. But alongside the sobering accounts are success stories of reintroducing species, ridding areas of introduced pests, and preserving habitat.

We spoke this week to Dr Ford who will also be appearing on 702 Sydney ABC on October 7th with Linda Mottram (8.30 - 11.00 am) about this important new book.

________________________________________

Earlier this year the NSW Government announced plans to reintroduce 8 extinct and endangered species to National Parks in various regions - based on what your research has brought to light, what prerequisites and areas (in Parks) would you recommend they focus on to achieve success?

Reintroduction of species is a key approach to achieving actual conservation gains for species that have disappeared across their former distributions. As with any recovery program the answer to this question will vary depending on the type of species. However, the reality with reintroduction is that there is always an unfortunately large element of chance involved in achieving long-term success, so its vitally important to ensure that everything else is as conducive to success as possible.

One of the key messages from Gould's time is that most of the smaller species that are now threatened have the potential to be 'pests'. Early settlers found species like quolls ('native cats') to be obnoxious beasts that ate their poultry, and bettongs ('kangaroo rats') raided their gardens. Give these species the chance through introducing them to enough places and not expecting them to immediately establish and they can probably make a decent go of it. Address the key threats, such as foxes and cats for bettongs, and don't be afraid to keep introducing a few more individuals over time to keep bolstering the population until it finds its own feet.

One of the issues we currently have with many successful reintroductions in eastern Australia is that they have to be conducted within fenced enclosures to ensure success. The alternative is to not fence, but to recognise that recruitment of more animals can counter-act the effects of predation. Its slightly encouraging to bear in mind that there are far fewer rabbits now than there were around the start of the twentieth century when many populations of native animals went extinct. This has two key outcomes 1) fewer rabbits means more food and habitat and less competition and 2) less foxes.

If we can generally raise the populations of native species over multiple sites instead of single sites, and do so outside of fences, or in combination with a few key fenced areas that act as a source populations, then we have the greatest chance of success. Another issue in choosing sites is the perception of what the habitat requirements of a particular species are. Most threatened species once inhabited many more types of habitats than the small, relict populations now left. Decisions about where a species can survive today are often swayed by a very limited perception of what the species is actually capable of given the chance. A case in point is the species that became restricted to offshore islands, like the greater stick nest rat. You can take them and stick them in the middle of the South Australian desert (where there is no sea weed) and they still do fine. So - to answer the specific question; almost anywhere with native habitat within a species former distribution, and at as many of those sites as possible where there is a chance populations could grow and naturally re-connect themselves.

How do you think Gould would respond to the information that so many of the species he once brought to light are now dead?

Even as Gould was writing he was very admonishing of the Australian philosophy of introducing European species to the detriment of native ones. He also was firmly of the belief that it was inevitable that many species would go extinct, although he thought persecution and hunting would be the key drivers. Interestingly Gould was also very admiring of the flavour of bandicoots and many kangaroos, and would probably be more amazed at the lack of exploitation of Australian animals than at the extinctions that have occurred. He would probably be surprised by the loss of the smaller 'pest' species because no one probably expected the extreme almost continent-wide impacts of species like the rabbit and fox on these smaller species. Ultimately Gould was a bit of a fatalist. he saw the extinction of the Thylacine (Tasmanian Tiger) as tragic, but understandable given the inevitable demonisation and conflict of large predators with graziers the world over.

Even as Gould was writing he was very admonishing of the Australian philosophy of introducing European species to the detriment of native ones. He also was firmly of the belief that it was inevitable that many species would go extinct, although he thought persecution and hunting would be the key drivers. Interestingly Gould was also very admiring of the flavour of bandicoots and many kangaroos, and would probably be more amazed at the lack of exploitation of Australian animals than at the extinctions that have occurred. He would probably be surprised by the loss of the smaller 'pest' species because no one probably expected the extreme almost continent-wide impacts of species like the rabbit and fox on these smaller species. Ultimately Gould was a bit of a fatalist. he saw the extinction of the Thylacine (Tasmanian Tiger) as tragic, but understandable given the inevitable demonisation and conflict of large predators with graziers the world over.

Portrait of John Gould, ornithologist by Maguire, T. H. (Thomas Herbert), 1821-1895. (1849 ?) - nla.pic-an9547887

The endangered smoky mouse inland of Eden - what attracted you to studying this - and what did your thesis conclude?

Honestly, the original attraction was a great field-based project proposal complete with scholarship but I very quickly became engrossed in the intrigue of the Australian rodents and the fact that they are so underestimated in the public knowledge of our fauna (25% of all mammal are rodents, and only about half of Australia's mammals are marsupials).

Ultimately that research in rodents continued through my PhD and first book, "Native Rats and Mice" which I co-authored with Bill Breed from the University of Adelaide. The smoky mouse itself proved to be a remarkable animal- one of the only species of its kind that nests communally in a forest environment. I found up to five breeding females all nesting in the same burrow. No one expected that. They can also move extraordinary distances each night for such a small species. Even just routine feeding trips can cover kilometres of distance. Many northern hemisphere rodents that appear to be similar may never move more than twenty meters or so from their nest. Unfortunately I also witnesses a major population crash.

Smoky mice just tend to appear and disappear almost as fast, which makes it really hard to manage them in a sensible fashion beyond making sure that large enough areas exist for them to go on blinking on and off across a landscape. I went on to look further afield for smoky mice, and followed old bone deposits to Yarrangobilly Caves in Kosciuszko National Park. I never managed to trap a mouse in Kosi, but one afternoon while I was going for a walk along the river I found three lying dead on the walking track. That pretty much sums up the species - you can look and look, and study and study and hardly learn a thing. They hold their secrets, but then occasionally throw up a random finding or event that re-energises your interest.

Which introduced animal contributed the most towards the destruction of native species - 'homo sapiens Anglo Saxon' - the fox, the rabbit, the dog or the cat, or hard hoofed domesticated sheep and cattle?

Its an undeniable toxic mix of factors, and for some species a different factor has primacy. For rock wallabies that don't move much between rocky outcrops, and therefore don't re-colonise areas where they have disappeared very easily, hunting by 'Homo sapiens' probably was the key original driver, reinforced by fox predation on small remnant populations. The vast scale of clearing in the sheep/wheat belts certainly doesn't help most native animals to survive, but when you think of what most rodents for example want, its a large field of wheat. The two prime drivers of extinction across much of the continent were probably rabbits and foxes in combination, but there are species like quolls and the white tailed rabbit rat where disease seems to be a more likely cause of population declines, and ultimately extinction for the rabbit rat.

Gould met a virtual Eden, a land teeming with life of every variety - and visited so many places during his tours - if you could time travel, which leg/state would you undertake as a personal favourite, and why?

To some extent you can still "time travel' if you visit Tasmania. Many of the species Gould encountered on the mainland are still found there, although the chance that foxes have taken a hold and the presence of Devil facial tumour may yet change that state of affairs. However, I guess what would be the most interesting place to see would have to be Sydney and surrounds purely from the degree of modern change across that landscape.

Van Diemans Land - p.2 – Vue de la rade de Hobart-Town, Ile Van-Diemen - [Paris] : Tastu, [1833] ([Paris] : Lith. A. Bes) 1 print : lithograph, hand col., St. Aulaire, A. (Achille), 1801-approximately 1833/1889, nla.pic-an8368168, courtesy National Library of Australia

European settlers changed the landscape - orchard attracting fruit bats, paddocks attracting kangaroos or even birds - how has this contributed to the destruction of some species and endangerment and extinction of others?

The changes have certainly benefited many species like the large kangaroos, cockatoos, crested pidgeons, galahs etc etc. What's interesting among the mammals is that many species did benefit from the early modification, particularly the smaller macropods like bettongs and wallabies, and had bounties placed on their heads in response. It wasn't the bounties that changed their capacity to take advantage of the modified landscapes, it was the later pressures like fox predation.

It also wasn't just the native animals that suffered under these later pressures. The farmers who had modified the landscapes saw the productivity of their efforts disappear as rabbits took over in the late 1800s. The clear message from accounts through the late 1800s and early 1900s is one of the whole landscape losing productivity and the capacity to sustain both agriculture and animals.

It's really not clear how much of a lasting impact that will be, but Australia is a fragile system with limited capacity to regenerate that lost productivity. There are of course other species like flying foxes that are still in direct competition with farmers, and high death rates due to the use of electric grids and other crop protection measures have contributed to the threatened species listing of two species of flying foxes.

The art works and artists who created this Illustrations for Gould's works - do you have a favourite?

Not really. Among Gould's images illustrated by Henry Richter I think the Thylacine head is one with some appeal; solely because Gould presented it at life size, something he could do in the large folios he produced.

Not really. Among Gould's images illustrated by Henry Richter I think the Thylacine head is one with some appeal; solely because Gould presented it at life size, something he could do in the large folios he produced.

Right: Thylacinus cynocephalus, key plate (1841) by H C Richter - nla.pic-vn3292752

There are also some quirky images like the numbat where Gould sketched it eating ants, although in reality it eats termites. This visual preservation of the fact that Gould's works really still represent the start of our understanding of the mammal fauna is a nice foible of the fact that he tried to engender meaningful context to his colour plates.

Among the many other illustrations and content used to accompany the text its always nice to see your own photos in print, but its really the 'word pictures' provided by some of the newspaper clippings that I find most interesting; like the debate between 'A bushman' and 'yet another bushman' about the purpose of the nail on a nailtail wallaby's tail; swinging from cliffs doesn't sit high on the list of accepted theories today!

Taken as a whole, the scope of imagery drawn from the National Library's collections is just a great visual setting for the historical context, and many of the images do of themselves tell great stories of moments in our history.

What, for you, was the best part about creating this wonderful work and its records?

It was a pleasant diversion to put myself back in the early 1800s, although that was also bitter-sweet when having to come back to modern reality. However, I think the best thing was the capacity to really delve into the collections of the NLA (National Library of Australia). Anyone who has logged on to Trove- the libraries online collection and catalogue- will know that you can really get lost in there. I wasted far too much time while researching the book going off on tangents about all sorts of other things. I’m very proud that this book while now form part of that collection.

Nailtail Wallabies - p 174

Dr. Fred Ford

John Gould's Extinct and Endangered Mammals of Australia

John Gould's Extinct and Endangered Mammals of Australia

By Dr. Fred Ford

Publisher: National Library of Australia

Edition: 1st Edition

ISBN: 9780642278616

Pages: 280

Publication Date: 01 October 2014

Price $49.99

Overview

How poignant it is to look at some of Gould's beautiful images of our animals and know that some are no longer with us, and some are fighting for their lives?

In this book, author Fred Ford compares Gould’s world, and the world that the animals live in at that time, with the world today. John Gould’s Extinct and Endangered Mammals of Australia includes 46 Australian mammal species that, today, are threatened or extinct and that were portrayed in the lavish colour plates in John Gould’s 1863 publication, The Mammals of Australia.

Each animal ‘opener spread’ begins with a Gould plate accompanied by ‘At a Glance’—a very short summary; the conservation status according to the EPBC (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation) list, the species names, a map of its former and current distribution and sites of reintroduction; and a timeline of the species history since European colonisation.

Accompanying the pictures are accounts of the animals as they lived in the relatively untouched Australia that John Gould knew, and evidence of the attitudes of European settlers towards the native fauna. The author provides the reader with fascinating, and often poignant, material and stories of what would be considered today as shameful behaviour and attitudes towards Australia’s native fauna. In this book are not only sobering stories of the fate of these animals after Gould’s time, but also success stories of reintroducing species to places, ridding areas of introduced pests, and preserving habitat.

Purchase Online at: publishing.nla.gov.au/book/john-goulds-extinct-and-endangered-mammals-of-australia.do

About Dr. Fred Ford and his work

I lived in Canberra until completing an undergraduate Science degree ANU in 1997. My honours thesis was on the endangered smoky mouse inland of Eden and began my research interest in threatened native mammals, particularly native rodents. My PhD, based out of James Cook University, Townsville, focussed on native rodents across northern Australia, in particular the intriguing pebble-mound mice. I also conducted small contracted research projects for the NSW National Park and Wildlife Service during which I worked on a variety of mammals including endangered mountain pygmy possums and spotted tailed quolls.

Between 2003-2007 I began to investigate bone deposits left by owls in caves to help track down rare and endangered mammals in the south-east. This led to a position at CSIRO’s Australian National Wildlife Collection (2007-2010) that specifically looked at the natural mammal fauna of eastern Australia before European colonisation in 1788. This formed the background research and thinking that developed into the information presented in this book.

John Gould’s Extinct and Endangered Mammals of Australia takes up the story of Australian mammals that were known to the early explorers and naturalists as documented by Gould in his landmark three volume work “the Mammals of Australia”, completed in 1863.

The book describes the relationship of early authors, the public and subsequent generations to these mammals. It also charts how the wholesale changes to the continent since 1863 have caused the wholesale loss of populations of native mammals, ending in the extinction of many species.

Aside from the works of John Gould himself, other key books on Australian mammals from the early and mid 20th century add authoritative accounts of the fate of such species, but for many species the more revealing information can be gleaned from newspaper articles describing hunting trips, quirky encounters, garden pests and outlandish claims of near supernatural attributes of the fauna. For many species the complete lack of information is equally revealing. They disappeared without ever being seen or documented in any meaningful way by European settlers.

Some key stories are extremely well documented, such as the very vocal resistance to the hunting of koalas for the fur trade that resulted in massive public outcry in the 1920s and the need for federal government intervention to prevent the export of skins from Queensland. The Thylacine too, was a species of international conservation concern that was actively persecuted to extinction by the Tasmanian Government, who moved far too late to enact protective measures to preserve the species.

It took two years to complete my book. Over that time I spent much time pouring over the works of Gould, and scanning articles on the National Library’s Trove collection, as well as reviewing museum records of animals and scientific papers about the conservation and history of the species.

Examples of what you may find in Trove regarding Mr. Gould:

GOULD'S BIRDS OF AUSTRALIA.

Of all Ornithological paintings, those of Mr. and Mrs. Gould's are far the most natural and beautiful. Their works on the birds of the Himalaya Mountains, their Monographs of the Toucans, and Trogons, and their great one on the ' Birds of Europe,' just brought to a close after six years of unremitting toil, have progressively in-creased their fame ; but they must all yield the palm to the 'Birds of Australia,' which both from the superior beauty of the subjects it contains, and from the greater finish given to it, promises to be the most splendid work on Ornithology that has ever appeared ; and one moment's comparison with Lewin's book on the same subject, will show how amazingly Natural History painting has advanced since that work appeared. Mr. and Mrs. Gould are now in the colony, to which they have come at great expense and sacrifice of comfort, purely with the view of making this work still more valuable by taking their drawings from living specimens ; and an additional recommendation is, that in the drawings which we have kindly been permitted to see, the birds are placed on our native shrubs, so that in fact we shall possess two works in one. Before we proceed to review the two parts which have al-ready appeared, we would call on our wealthy colonists to come forward and enter their names as subscribers, and thus become the Stanleys and the Devon-shires of Tasmania, by becoming the patrons of science.

Plates 1 and 2 contain two species of Malurus, the superb warbler of the older naturalists, one dedicated to Mr. Lambert ; the other the Melegans first described in the present work, both exceedingly beautiful, yet in our opinion neither of them equals our old superb warbler or Blue Wren ; and we doubt if even the inimitable pencil of Mrs. Gould can do adequate justice to the exquisite colouring of this splendid bird. Plate 3 is a figure of Calodera maculata, a bird allied to the Satin bird of New South Wales, and remarkable for the singular ruff around its neck. Plates 4 and 15 represent two species of Amadina, neither however can vie in delicacy of pencilling with our own little Amadina or Fire tail. In plate 5, we have three figures of a rare and most lovely Ground paroquet, the Nanodes undulatis, which

our fair friends would term 'loves of birds.' Plate 6 contains a male and female of the Nymphicus nova Hollandiae, a very delicate and quaker-like looking paroquet, with a crest like a cockatoo, one or two of which we believe may be seen in confinement in Hobart. Plates7 and 16 are figures of two large and remarkable parrots, the one from New Zealand, and the other from Norfolk Island, distinguished for the great length of the upper mandible. In plate 8, we have a quail, supposed by the author to be an inhabitant of Van Diemen's Land, but which however we have never seen. Plate 9 is the figure of a beautiful bird

from Port Phillip, or the south coast, a species of long-legged plover or rather Avocet, which we consider to be one ofthe happiest efforts of Mrs. Gould's pencil ; the bird is placed in a position so truly graceful and animated, that it al-most appears to move. Plate 10 is a Cormorant from New Zealand, taken home by Capt Lambert, of the Alligator. In the next plate we meet with the wiretailed swift of Van Diemen's Land, the Cbaetura macroptera of Swainson, which must be an exceedingly rare bird in the sister colony, since Mr. Gould states that he never received but one specimen; here, however, it is occasionally more

plentiful, as we know a gentleman who saw them in flocks near Richmond, two specimens of which he secured for we believe, the British museum: a specimen may also be seen in our Hobart Museum. But we must pass over the remaining plates to notice the Apteryx australis, which is represented nearly the size of life in plate 19. This bird was first described by Dr. Shaw, in 1812;but from that time till a very short period prior to the present publication no other specimen was sent to England, till at length the very existence of the bird was doubted. However, all doubts are now at an end, as the figures were taken from two specimens presented to the Zoological Society of London, by the New Zealand Association. GOULD'S BIRDS OF AUSTRALIA. (1838, October 12). The Hobart Town Courier (Tas. : 1827 - 1839), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4162381

John Gould.

Admittedly the greatest bird observer of Australia was an Englishman—John Gould. But his fame was not confined to Australia. He deservedly won worldwide distinction. Few people, however, realise how much he did for ornithology or the personal risk and hardships lie faced in acquiring his knowledge when Australia was chiefly wild and unknown bush. In the course of an interesting address on this subject, Mr. A. J. Campbell (the well-known Victorian authority) threw some light on the work of Gould in this country:—

Accompanied by his wife and their eldest son he left England for Australia in May, 1838. Melbourne was then one year old. Bell-birds tinkled their chime like notes among the redgums on the Richmond Flats; curlew-calls made nocturnal music in the Government Domain; crowds of quail frequented the kangaroo-grass crops on the stony rises of Footscray, where big bustards proudly paced; while the West Melbourne Swamp and Albert Park Lagoon—the former long since reclaimed, the latter not then named —were teeming with fowl of every wing. Gould first landed in Tasmania then proceeded to South Australia, returned to Tasmania; and, lastly, visited New South Wales. Thence he reached home in August, 1840, via Cape Horn, thereby completing the circuit of the southern Seas, which greatly helped him in his important work among the petrels-.Gould had able coadjutors—John Gilbert, killed by aborigines in the Gulf of Carpentaria district; Johnson Drummond, killed in like manner in Western Australia , and others. The number of species of Australian avi-fauna was raised from300 to 600 by the adventurous journey of Gould and his worthy assistants—a gigantic undertaking in those early days. The trip cost £2000 The amount would have been much greater had it not been for the extreme hospitality Gould and his family received at the hands of the pioneer colonists. When he was in Tasmania his family were guests of Sir John and Lady Franklin at Government House, where Mr. and Mrs. Gould had a son born to them. That the great naturalist had a son an Australian native is indeed a strong bond of sympathy between present-day natives and the historic past.

"On returning to England Gould immediately recommenced (for he had in 1837 commenced to publish a work on Australian birds, but found he had insufficient material to carry out the project successfully) his immortal work on "The Birds of Australia," the first part of which appeared in 1840, and by 1848 the seven handsome volumes, containing 600 plates, were completed. In 1851 the first of his folio "Supplement" was published, and in 1865 the exceedingly helpful twin volumed "Handbook", appeared. There is a copy of this great work in the Melbourne Public Library. It is on the basis of this savant's authority that Mr. Campbell takes up his position about bird naming. Australian ornithologists in choosing Gould are precisely on the same footing, and are adopting the same rule as did the old-world ornithologists in regard to Linnaeus. There must be a limit, and Mr. Campbell quotes with apparent approval an American code which states:- 'It is undeniable that a mere shuffling of names ... is mistaken for scientific research and the advancement of science.'

Gould was the Audubon of Australia. Just as it is natural for northern nations, Says Mr. Campbell, to honour Linnaeus with the limit of priority in nomenclature, so Australia desires to honour Gould, who did more for Australian bird love, and even for the ornithology of the world, than Linnaeus." John Gould. (1919, May 9). The Land (Sydney, NSW : 1911 - 1954), p. 9. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103013430

WHERE JOHN GOULD LIVED

The late John Gould, F.R.S., of London, a world-famous ornithologist, visited Australia and Tasmania in the interest and scientific study of our native birds, during 1838 to the early part of 1840, and returned to England. The Gould League of Bird Lovers was named and formed in Australia a number of years ago in honor of Mr. Gould, as all school children know. While in New South Wales he did much practical and important work about Scone during the latter months of 1839, and the early months of 1840, and resided at Yarrundi, on the Dartbrook Creek, several miles west of Scone.'

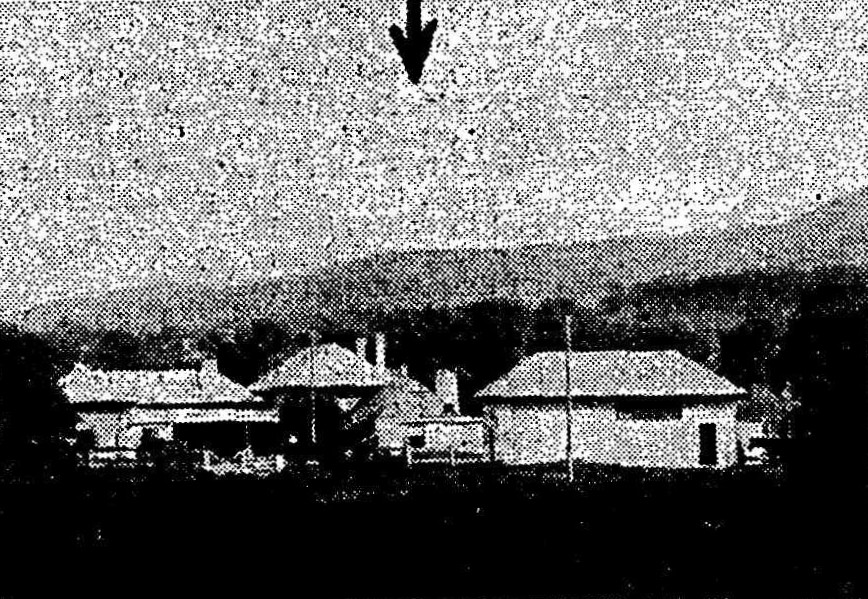

The writer had the pleasure of making his first visit to the latter locality during 1907, and photographed the small house in which Gould' lived so long ago. When Gould was there, the Yarrundi homestead was occupied by relations of his named Coxen, and this was Gould's headquarters for that district. The little house shown immediately below the arrow in this photograph is where Gould lived at Yarrundi, and', it was pulled down about ten years after the photograph was taken. The other buildings are all recent additions. In his great and most valuable work, "Birds of Australia,"' he frequently mentions Scone and the district.-Cherra-Chelbo. WHERE JOHN GOULD LIVED. (1934, August 29). The World's News (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 1955), p. 11. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13699897

Hobart Town, / Van Diemen's Land - 1828 by Evans, George William, 1780-1852, Image No.: a1528626, courtesy State Library of NSW and NLA: Published 1828, by R. Ackermann, 96 Strand, London.