October 14 -20, 2012: Issue 80

Les Ball

How long have you been in Ingleside?

How long have you been in Ingleside?

In 1954 I came here; to my mum in laws in Gondola Road, Narrabeen. I was there for a while and this place came up for sale. The lady who owned it was a retired school teacher and I made an offer. The son was in New Guinea; that would have been about January and later, in 1955 the sale went through.

You have a bit of land here?

It’s about 1.3 acres. It was much the same then as it is now. I looked out here then at night and its black, not a light. Now, I can see one, two, three; traffic lights, road lights. When I came here that place wasn’t there. The one over there was here and just one there. There was no Westpac training college; it was cobblestones on the road too; probably from World War I.

At Elanora; I came back in 1944, I’d been married in the June, and I came straight from the showground out to Gondola road, North Narrabeen and again at the end of 45 and ’46 and Narrabeen was a weekender kind of place. There were little fibro boxes everywhere which may not have been built as weekenders but that’s the kind of place it was, just like Harbord was a weekender kind of place way back in the 1940’s, before the war.

There was a quarry just past Beananna road, a continuation of Rickard road and going up the hill, McFarlane’s quarry. There was Elanora Country club, but Monash wouldn’t have been there yet. The only road that would have gone right through would have been Powderworks road. There was always a road going to Elanora Country Club, no Wakehurst Parkway then.

Where were you born?

Wallace Street West Kogarah; it’s called ‘Bexley’ now. That area was paddocks for sport; cricket and look for birds. I went to Carlton Primary School then to Hurstville Tech. it was like a High School, it went to third year, and this was during the Depression. Even when I went to Infant’s School, which was also during the Depression, there were kids coming to school with bare feet. The Dole then, they got tickets to buy food, they didn’t get money, so money was very scarce. A penny would be worth about 20 cents or more.

This card from 1910 is from my mother to my father. My parents (Florrie and Claude) got married in 1917 and she’d have been about 15 or 16 when he received this. They knew one another since then, it was a long time before they got married. My father worked as a sugar boiler in The Colonial Sugar Company. During WWI he was in Fiji and was a great letter writer and described being on the ship to Fiji and current dress over there.

How old were you when you went into the Army?

23. I left school just after I turned 15 and as we were in the Depression I couldn’t get a job. I was at the Enmore Tech, finishing my fourth year, and I can remember going for a job at Anthony Hordern’s Emporium, there was a stack of boys going for some little job like a messenger.

I was playing sport then too, at Tempe, there was a sports field there along the Cook’s River, I was playing cricket there one day and an uncle of mine, an ex-International footballer, he worked at the Fire Brigade in Sydney, he worked at the headquarters in Castlereagh street, and through his boss, who also knew the boss at a motor place, he learned that they wanted a boy. So my uncle came out on a tram all the way to Tempe to get me. So then I was half a day at school and half a day at work. I began at H W Crouch Pty. Ltd., they were the Federal Truck Distributors, which were quite popular then.

They were making an American truck that was similar to a Diamond T, they were good trucks and a good company. So when I went into the army I was still working there. I was specialising by then in doing alterations to wheel bases and the roofs. When they came out they’d arrive in cases and had to be assembled. For taxation purposes and import duties it worked out better to do this. In the shed the springs would be made; a lot of the extra parts were made here; they didn’t import those. The chassis would be in rails and I used to put them together, do the riveting, or wheel base alterations so that they’re 167 each on the wheel base. Somebody might want 180 sometimes so I’d build a bigger body. The boss said I was the best one there they had doing that.

That would have been 1933. Fifteen shillings a week when I started. I’d give my mother ten shillings, the train ticket from Kogarah or Rockdale for six days a week going into Liverpool street was 2/ and tuppence a week.

When you were going home at half past five you’d be hanging out the trains were that packed. Everybody evidently knocked off at the same time. I’d get in the train at Museum station; I’d walk down and catch it there. You worked the Saturday morning, so that was six days a week.

My mother was a terrific person, very strong, and in Wallace street, there was my mother, father and me, and I had a sister six years younger then me, and a couple hundred metres up the road was my grandmother Weir, an Irish family, from Northern Ireland, they came out here about 1850 during the potato famine. My grandmother was nine years of age when she came out here. Further up the road were my mother’s cousins. They, the Weirs, went to Mackay in QLD originally, possibly because Australia was after workers for the cane fields. They were there about 12 months and then came to Sydney when they were building train lines out to Kogarah. A lady wrote a book about all this titled ‘Don’t blame the Weirs’. I’m not sure whether it was published or not.

Family photo circa 1923, Les is little boy second from left first row.

So you went into the Armoured Division ?

Yes. During the war they called up for training for different Army units and I did training in what was called the Universal Army Training, I’d already done three months of that. The next year I was called up do more and then I joined the AIF. We were Corp Troops. This was about the time they were forming a new division, The Armoured Division; they picked those out that they thought were more qualified to be part of this division. The Armoured Division wasn’t formed when I went in, they formed that later. I enlisted the 23rd of July 1941 and that was in anArmoured Training Regiment in Redfern, then we were at Cowra.

The first division formed was the 2nd/11th Armoured Car Regiment and I went in that at Cowra. Then we went off to Greta in the Hunter Valley, still training. They formed another regiment about that time and that started off the Armoured Division. If you were interviewing someone who said they were in the Armoured Division then they probably would have started off at Greta and not know about Cowra, which was before then. Most of those I know now from that Division went in at Greta or after, they weren’t in at the beginning.

I can remember I was in the UT and we were in camp at Broadmeadow, I’d got a pass and they sent me down here, I went to Victoria Barracks to have my medial, vaccinations and all that, and went home and then in the afternoon we were off to Cowra and we changed trains at Blaney and it was cold, it was 11 o’clock at night and cold as anything.

There was 28 different items on the menu but later on they cut it down to 14. On a Friday we’d get a bit of fish and a bucket of ice cream. At Cowra there was one chap, they’d stick us all in a hut together, 14 of us, and one bloke had false teeth and he’d stick them in a glass of water and one morning they were frozen!

We were walking in to Cowra, me and a mate, and there was a car broken down with an older man, flat tyre, and I went over and helped him and changed his tyre. His surname was Penny and he owned half of Cowra; he lived in a big home right at the back of the shops up on the hill and he had us over for a couple of drinks; there was a waiter and all that; amazing house and life.

At the end of ’41 we were in Tamworth and from there we moved to Singleton, we did an exercise there. It was just opening there then, a tank range. When we were in Tamworth, on the establishment of the 2nd/11th Armoured Cars, I was to be the OC of the squadron, or driver/mechanic to the OC, the head of the squadron, but I’d done an examination while at Greta and was on a Trade Pay and I couldn’t be that and a mechanic to the rest of the squad.

Here’s a funny thing, must tell you this, would interest anybody; I was a top tennis player in the

Here’s a funny thing, must tell you this, would interest anybody; I was a top tennis player in the  district, even before I was in the Army. (Picture to left in Tennis Flannels; to right; pennats and badges from Les's tennis days) I’d been at the Reservists tennis court in Tamworth. My father had sent me a tennis racket (I used to get my tennis rackets for free from Slazenger’s due to the tournaments etc. I went in) and at this time it was just around when Pearl Harbour occurred or just after and they had restrictions on movements. The Army had made Tamworth train station out of bounds. Well I got a telegram through Brigade Headquarters to go to Tamworth station to pick up my racket. So I went in with a mate and at Tamworth station the parcel office faces outside like a shop. We went in there and we got picked up by the MPs. The BOOB was right near our line there, the Armoured Cars, with other regiments further along, and the OC found out I was in the BOOB and raced up to the Brigade headquarters and put on a bit of a performance telling them they shouldn’t have sent the telegram. So I got sprung out, we’d been in there about five hours; and do you know who was in charge of the Tamworth station picket at the time? Frank Packer! He was a Captain then, Frank Packer! He put us in the BOOB, Frank Packer!

district, even before I was in the Army. (Picture to left in Tennis Flannels; to right; pennats and badges from Les's tennis days) I’d been at the Reservists tennis court in Tamworth. My father had sent me a tennis racket (I used to get my tennis rackets for free from Slazenger’s due to the tournaments etc. I went in) and at this time it was just around when Pearl Harbour occurred or just after and they had restrictions on movements. The Army had made Tamworth train station out of bounds. Well I got a telegram through Brigade Headquarters to go to Tamworth station to pick up my racket. So I went in with a mate and at Tamworth station the parcel office faces outside like a shop. We went in there and we got picked up by the MPs. The BOOB was right near our line there, the Armoured Cars, with other regiments further along, and the OC found out I was in the BOOB and raced up to the Brigade headquarters and put on a bit of a performance telling them they shouldn’t have sent the telegram. So I got sprung out, we’d been in there about five hours; and do you know who was in charge of the Tamworth station picket at the time? Frank Packer! He was a Captain then, Frank Packer! He put us in the BOOB, Frank Packer!

Do you want any romantic bits?

Sure.

This is getting off the story a bit but anyway. I must have been on leave once in Newcastle, had been there before I joined the AIF, and I had a girl there. So we went down there from Great and they took us to a party out at Swansea, you caught trams out there then, and it was a Saturday, and we were supposed to be back Sunday morning for Church Parade. Well, I never got back. I’d been out all night; I’m up at Newcastle park, haven’t been back to camp, and had my girlfriend on one arm and her sister-in-law on the other arm walking through the park and there’s my Sergeant Major walking towards me. He didn’t like me after that, seeing me with those two beautiful girls. We knew a doctor and I got a Doctor’s certificate to say I’m sick but they didn’t believe that and I got seven days CB in camp. That was funny.

So when you did the training exercise at Singleton, what did that involve?

One training exercise we did maps and all the bridges. It would have been part of the squadron duties; there were only two or three dozen of us. I was an expert on the combination motorbikes then, because you never had jeeps, at that stage. These were Norton bikes; Norton combinations, like when you see a movie with the Germans riding them and they have sidecars. I taught different ones to ride them; they’d put them in gullies and then get them out, or how to drive on the sidecar wheel too. We went to do that and I’m travelling behind in one of the trucks and they told us we had to ‘live off the land’.

One training exercise we did maps and all the bridges. It would have been part of the squadron duties; there were only two or three dozen of us. I was an expert on the combination motorbikes then, because you never had jeeps, at that stage. These were Norton bikes; Norton combinations, like when you see a movie with the Germans riding them and they have sidecars. I taught different ones to ride them; they’d put them in gullies and then get them out, or how to drive on the sidecar wheel too. We went to do that and I’m travelling behind in one of the trucks and they told us we had to ‘live off the land’.

We had a stack of potatoes and some tea, which was restricted amongst the civilian population, so we could exchange that for meat and other essentials. This was part of the training, ‘live off the land’. I remember one group quite well, a truck with a canopy on it and they’d shot a pig, some farmers pig, and had it strung up to clean it, and that caused a bit of a fuss.

We came back and stopped at Gloucester, they made a bit of a fuss there because they didn’t know we were coming, and put the vehicles in the showground where they used to show the picture shows and the town people came out and had a look. I had a picket at 12 o’clock, the night was my share of the picket, well I never got back in time to do the picket so the picket broke down. We met some girls, that’s why we didn’t get back. Nobody worried about it, I hoped over the fence at six in the morning.

We were camped at Dungog then. So they then had a big whole divisional exercise in Northern NSW in 1942 and I was in the Armoured Cars. From the 2nd/11th. The whole Division was camped between Gunnedah and Narrabri, all those places. Our regiment, for training purposes, was the enemy to the rest of the Division. We were moving all the time; we’d be camped, move at night time then set up again. After so many weeks up there the campaign in New Guinea was getting worse. The Japanese were about fourty miles from Port Moresby. I’d been sent into the 2nd/6th then to make the numbers up. They were short of equipment then too, so any equipment not in use was handed in. we’re loading machine gun belts, pistols and the like for days before we went. I had been issued a 45 which was probably from another regiment. We went straight from there straight through on a train to Brisbane, didn’t get out, the meals were handed to us through the windows at stations along the way. At Brisbane we changed trains and went straight through to Townsville and we were evidently to be on a convoy and we missed it by six hours. So we then spent a fortnight in Townsville, and B Squadron, the one I was in, we were split up, and we went straight to Milne Bay. The others were sent to Moresby.

Milne Bay had just finished; that as the first defeat of the Japanese, at Milne Bay. That was ’42. Milne Bay was very important because that was the first defeat, they stopped them from getting to Port Moresby. We arrived about two months after that. The ship we were on, zigzagging and very fast, straight to Moresby then on to Milne Bay. As we went in there was a ship sunk there, laying on its side in there. Milne Bay is about the wettest place in the world and it was a very wet year in 1942. They couldn’t move anything, there was mud up to your knees, you’d sink walking along the track. You’d pick place to walk, but if you had to move a vehicle along the track you couldn’t. It was just a bog.

Milne Bay had just finished; that as the first defeat of the Japanese, at Milne Bay. That was ’42. Milne Bay was very important because that was the first defeat, they stopped them from getting to Port Moresby. We arrived about two months after that. The ship we were on, zigzagging and very fast, straight to Moresby then on to Milne Bay. As we went in there was a ship sunk there, laying on its side in there. Milne Bay is about the wettest place in the world and it was a very wet year in 1942. They couldn’t move anything, there was mud up to your knees, you’d sink walking along the track. You’d pick place to walk, but if you had to move a vehicle along the track you couldn’t. It was just a bog.

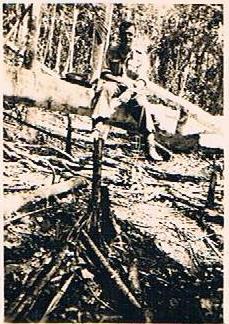

Picture to left is of Les at Milne Bay, 1942

The Japanese had got out by sea and gone into the hills at the back of Milne Bay and they were firing 25 pounders into those hills one after the other. If you were trying to sleep it was just constant ‘bang! BANG!’. So they could move something they had everybody there do a shift getting gravel. I was out with the others one night digging up this gravel and I got malignant Malaria. There was no hospital, only a field ambulance; there were people dying around me. Milne Bay was a shocking place then particularly. They treated me very well; I took quinine, and then went convalescing for three weeks.

When I came out my squadron had moved, heading for Buna. I was placed with another of our squadrons that had been moved from Moresby to take their place. There was four others like me; we eventually had to catch up to them.

.jpg?timestamp=1350115268777) Photo to right: 1943-01-07. PAPUA, GIROPA POINT. MEMBERS OF 2/12TH INFANTRY BATTALION ADVANCE AS GENERAL STUART M3 LIGHT TANKS MANNED BY B SQUADRON, 2/6TH ARMOURED REGIMENT, BLAST JAPANESE PILLBOXES IN THE FINAL ASSAULT ON BUNA. NOTE MACHINE GUN ON TANK CLEARING TREETOPS OF SNIPERS BY SYSTEMATIC SPRAYING OF TREES AS THE INFANTRY MOVES FORWARD. THIS TANK, IN ONE MORNING'S FIGHTING, FIRED 10,000 ROUNDS OF MACHINE GUN AMMUNITION. THE PHOTOGRAPH WAS TAKEN DURING ACTUAL FIGHTING. NEAREST THE TANK IS CORPORAL G. G. FLETCHER, AND NEXT TO THE TREE (CENTRE) CORPORAL M. D. CROKER. (NEGATIVE BY GEORGE SILK).This image is available from the Collection Database of the Australian War Memorial under the ID Number: 014008

Photo to right: 1943-01-07. PAPUA, GIROPA POINT. MEMBERS OF 2/12TH INFANTRY BATTALION ADVANCE AS GENERAL STUART M3 LIGHT TANKS MANNED BY B SQUADRON, 2/6TH ARMOURED REGIMENT, BLAST JAPANESE PILLBOXES IN THE FINAL ASSAULT ON BUNA. NOTE MACHINE GUN ON TANK CLEARING TREETOPS OF SNIPERS BY SYSTEMATIC SPRAYING OF TREES AS THE INFANTRY MOVES FORWARD. THIS TANK, IN ONE MORNING'S FIGHTING, FIRED 10,000 ROUNDS OF MACHINE GUN AMMUNITION. THE PHOTOGRAPH WAS TAKEN DURING ACTUAL FIGHTING. NEAREST THE TANK IS CORPORAL G. G. FLETCHER, AND NEXT TO THE TREE (CENTRE) CORPORAL M. D. CROKER. (NEGATIVE BY GEORGE SILK).This image is available from the Collection Database of the Australian War Memorial under the ID Number: 014008

Well, they did the Buna campaign and at Sanananda we caught up to them. At Oro Bay, the ship called the Tungsung took us there; Oro Bay was the only deep water spot. At night the Japanese would fly over, they’d probably been bombed every night by then. We ate pretty well there; they had all the food stored there, cases of peaches. The next day we went on a small boat like those Halverson cruisers they have nowadays up to Buna and we’re going along and all we had was .5 gun on the thing.

The 41st American Division were in control then there. So we had to meet our crowd; they didn’t come down this track because I think the damned think might have still been mined then so we had to meet them along a bit.

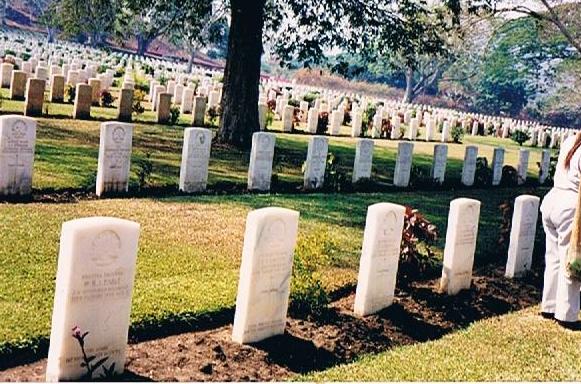

The dead around there, so many; the Australians had been buried and had their rifles with the tin hat on top to mark their graves. The Japanese were laying around dead. We’d crossed a bridge there and I saw a Japanese laying there dead and thought then they must have a had bit of a hospital there. Evidently they didn’t I’ve since found out. There were so many dead still there because there was intense fighting at Sanananda. They thought once Buna fell Sanananda would go too but it didn’t.

The dead around there, so many; the Australians had been buried and had their rifles with the tin hat on top to mark their graves. The Japanese were laying around dead. We’d crossed a bridge there and I saw a Japanese laying there dead and thought then they must have a had bit of a hospital there. Evidently they didn’t I’ve since found out. There were so many dead still there because there was intense fighting at Sanananda. They thought once Buna fell Sanananda would go too but it didn’t.

If you read the papers in Australia then they gave you the case that Sanananda was going to fall but it didn’t. There were 96% casualties there; they weren’t all killed but there were injuries, sickness. 96%! in that campaign. We lost some of ours, they were killed in the tanks. They put four tanks in that Sanananda fight and there wasn’t any traction there. All of the side was swamped so it was easy for the Japanese to defend it there, just mine the thing or put guns in. They shouldn’t have put the tanks in there but they did and the four of them got knocked out; they all got incinerated. They were hit with a gun, mined at the same time, and it blew the whole thing up. The tanks couldn’t turn around, couldn’t move, couldn’t do anything as a result.

The five of us caught up with our unit there, Sanananda. We went into Suputa, a complete jungle. There was a stream running through, with a big freshwater pool, anyone could peel off and swim in it. I camped with one of my mates in a tree about four or five foot off the ground, among bamboo. It was hot as anything; we had a sheet, no blanket, or a groundsheet over us to keep the rain off. That jungle was so thick they could fly over and they wouldn’t have a clue you were in there. That’s where I was until we went to Popondetta. At Popondetta there were a couple of big huts to accommodate twenty or more in each with cots and mosquito nets. I can remember being on picket one night at Popondetta, I don’t know what I would have done if any Japanese came up, I had a tommy gun, and we’d shoot towards the water; it was so dark you might have killed your own. If you could see them it’d be alright.

The five of us caught up with our unit there, Sanananda. We went into Suputa, a complete jungle. There was a stream running through, with a big freshwater pool, anyone could peel off and swim in it. I camped with one of my mates in a tree about four or five foot off the ground, among bamboo. It was hot as anything; we had a sheet, no blanket, or a groundsheet over us to keep the rain off. That jungle was so thick they could fly over and they wouldn’t have a clue you were in there. That’s where I was until we went to Popondetta. At Popondetta there were a couple of big huts to accommodate twenty or more in each with cots and mosquito nets. I can remember being on picket one night at Popondetta, I don’t know what I would have done if any Japanese came up, I had a tommy gun, and we’d shoot towards the water; it was so dark you might have killed your own. If you could see them it’d be alright.

The 41st American Division was camped about a mile from us and we’d exchange food with them. We had lots of fresh fruit; bananas, paw paws; Mount Lamington was just near us, farmland, and they’d grow pineapples, vegetables like pumpkins. We got sick of bully beef so we’d exchange it for some of their stuff. Their rations were better then the Australian ones although they were getting their rations mainly from Australia then; they were giving them better food for some reason then what we had.

The boys we had carrying water, the stream was about 25 metres away, were the Fuzzy Wuzzies. When we were going home they said “Australian boys going home. Me very sorry…me very sorry.”

The Bismarck Sea battle happened early March. They’d spotted this convoy coming across from Rabaul, which was under Japanese control then; it was warships, about ten thousand troops and more. These Catalina’s had spotted it. I was on picket that night; they brought a lot of planes over from Moresby to get at it. We were at Dobbinburin airstrip in the early hours of the morning and you could hear all the engines starting up. They sank everything; they even sank the Japanese in lifeboats; they were doing the same to us or would do the same to you. As the crow flies we weren’t that far away because you could hear them. If you turned the radios on on your tanks you could hear them; the American fighters, the Beaufighters underneath and them calling “They’re in the Way!” and hearing the bombs go off. There were 59 ships or 18 thousand troops all told on their way here.

Later on that same month we flew back to Port Moresby, had to camp there for about four days before we could catch the ship back to Townsville and then we’d train back to Sydney. This was mid-1943. You remember that hospital ship that got sunk around that time? (At approximately 4.15K hours on Friday 14 May 1943, the hospital ship A.H.S. Centaur, ablaze with lights, with a compliment of 332 persons on board, was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-177 south east of Cape Moreton, Queensland) that happened at the same time.

People aren’t aware how many Japanese submarines lie off our coasts from then or that they sunk about eighty ships; coal ships, the sixty milers, they sunk all them. All that early part we’re talking about people don’t realise; Macarthur, he wasn’t as popular then as he in now, Blamey too. They hardly ever got into the conflicts; I think they only went to New Guinea once. That’s why Curtin (then Prime Minister) wanted our troops back here; we were getting invaded and needed our soldiers back here to defend us. Then we had the Battle of the Coral Sea soon after; a few weeks later. All about the same time.

What did you do when you got back to Sydney?

I got married! I came home and Betty had about three boyfriends; one bloke was away, part of the 9th Division, a bloke she’d known since school. They’d been on leave just before us. The 9th Division, in the next year, they were doing fighting around Lai four months after Buna. Betty was engaged to him. I was stationed at the Showgrounds, just about to go on leave, accrued leave. Those that were getting married could have 24 days off, those that weren’t were getting 14 days. I rang my father first of all. I rang Betty, she was living with her auntie and uncle at Auburn. I said I was only in shorts and shirt and she said doesn’t matter, come over. We get married in a week’s time at Bexley at the church there. We had to see some minister and talk to him and so forth; at any rate we got organised and married within a few days!

Then I was due to go back and had probably exerted myself too much and I got malaria again. So I had to go into Uralla hospital at Concord. The doctor came, the medical officer and he said “you’ve got pneumonia.”; I knew it was the malaria but you can’t tell them. So he sent me into the chest complaint ward and said to the female doctor “I think I’ve got malaria.”. So she took a blood slide and it came back the next morning and she said “Your diagnosis was right; you’ve got malaria.”

So they put me on the quinine and Atebrin for 13 days then three weeks up at Ingleburn to convalesce. I used to go off every night there too; just put something in my bed in case they checked, and went home. Then they marked me awol though and had an inquiry over that too. Later on I went to Borneo. When I went back to catch up with my unit I got malaria again and then it was Queen’s Lake hospital. Same thing again. Then we were at Caboolture and I got malaria again! I got it about five or six times once we were back in Australia. That sort of saved me lots of times because if there was something nasty going on I’d get malaria and couldn’t go. I’d be sent to hospital.

So they put me on the quinine and Atebrin for 13 days then three weeks up at Ingleburn to convalesce. I used to go off every night there too; just put something in my bed in case they checked, and went home. Then they marked me awol though and had an inquiry over that too. Later on I went to Borneo. When I went back to catch up with my unit I got malaria again and then it was Queen’s Lake hospital. Same thing again. Then we were at Caboolture and I got malaria again! I got it about five or six times once we were back in Australia. That sort of saved me lots of times because if there was something nasty going on I’d get malaria and couldn’t go. I’d be sent to hospital.

With our regiment; the tanks got knocked out, people killed, we were under strength. They gave us a spell over in Western Australia and brought another regiment over to take our place in Queensland. Over in the west I was able to play sports again so my tennis came into play once more. That was good. I played for the Army in Western Australia and we won a competition there in 1944 at Queen’s Park where they play the big games now. It was grass then. That was good. It occupied the troops; the other sports too; Australian rules, some of them, the ‘odd sods’ you’d call them then, played basketball.

We came back after 8 or 9 months in the west and they didn’t need the mechanics and fitters so we went into a pool. I had leave when we came back and Betty had our eldest girl then; which was very good. I was sent to Queensland again, a DVD (Defence Vehicle Division) in Brisbane. Some of my mates there put a claim in for me and I went into a vehicle parts workshop which was ok. This was about thirty stops by tram from Brisbane.

I camped at Chermside there. I could play sports again there, do my tennis. I played in the Brisbane competition there, the Pennant competition. The Milton courts, the Army had those courts, and I was playing for East Brisbane. My partner, he was an ex-Olympic player and my female player would have been the best female player in Queensland. I played about a round in the competition before we were moved overseas.

We went on a Liberty ship, they were turning out one everyday in the United States (cargo ships built in the United States during World War II); they were done in sections then pushed together and welded. We left Brisbane and we were headed north and at Finschhafen we got wrecked. We were about twenty miles off the shipping lanes and we hit a reef. We were evacuated by Americans, by coast guards. Then we went to Morotai and then went on American LST’s to Balikpapan in Borneo. I was in the vehicle parts workshop there. We’d have been in the second wave landing there; this was 1945 by now.

What I’d like you to note here is that all the time we were going over there on those ships I only saw one Japanese plane. It was way up in the air, probably doing a message service or something, not even interested in us. So before, in the early part of the war when I mentioned Milne Bay, there were Japanese planes everywhere all the time. I remember when we were going into Oro Bay in New Guinea, four planes were skimming over the water towards us but they turned out to be B25’s, American planes. And us with that one little gun on the boat!

What I’d like you to note here is that all the time we were going over there on those ships I only saw one Japanese plane. It was way up in the air, probably doing a message service or something, not even interested in us. So before, in the early part of the war when I mentioned Milne Bay, there were Japanese planes everywhere all the time. I remember when we were going into Oro Bay in New Guinea, four planes were skimming over the water towards us but they turned out to be B25’s, American planes. And us with that one little gun on the boat!

That just shows the difference between the years; between that and then; one Japanese plane! So the Japanese were out of it then; there were still some at Wewak, up towards the northern end but they were just waiting for them then, starving them out. The Japanese were still resisting then, even when they were starving. They couldn’t get supplies in, the Australians were still wiping them out.

Anyway, we went to Borneo and it was similar there; the Japanese weren’t strong enough; they’d have just a gun on a train line inside the mountain and wheel it out and fire it, wheel it back in. When we finished there; I came home pretty quick; it took three months and then the war ended while I was there. I had the job of testing, because a lot of vehicles were handed in then, I’d be doing jeeps. I’d take them for a drive and test them and class them; Class 1, Class 2 or 3; I’d put a ticket on them. Here once again our food was crook and we exchanged with the Americans. They’d say “Come over with us.” They were off the ground, had their tents boarded up; and this chap would say “Oh, it’s an off day today.” And we’d be getting dished up Lamb’s fry and creamed potatoes and then ice cream later on. And the Yank in front of me was having a go because “They’ve only ordered three flavours of ice cream!”

In the middle of the Borneo… they were in the Navy. You never had bread in any of the places we Australians were, it was always hard biscuits. We had quince jam…bully beef…couldn’t have butter only margarine because the butter would go off.

When I came home my points were just about up and my form put in a claim for me. So I got back in ’45 and I went back to them in the early months of ’46 after my accrued leave. Betty and I went with her father, he was like a beachcomber only he’d go off with the aboriginals. We were at this sheep shed near Gunnedah; there were 16 stands of sheep, and we were bringing it down here for the farmers at Warriewood. We filled one railway truck and brought it down to Gordon station and then in a truck down here and we got about £75 for it, which was a lot of money then. This would have been ’46 before I went back to work. It was hot as hell that Summer; hotter down there; sheep dust. Betty worked like anything.

When I came home my points were just about up and my form put in a claim for me. So I got back in ’45 and I went back to them in the early months of ’46 after my accrued leave. Betty and I went with her father, he was like a beachcomber only he’d go off with the aboriginals. We were at this sheep shed near Gunnedah; there were 16 stands of sheep, and we were bringing it down here for the farmers at Warriewood. We filled one railway truck and brought it down to Gordon station and then in a truck down here and we got about £75 for it, which was a lot of money then. This would have been ’46 before I went back to work. It was hot as hell that Summer; hotter down there; sheep dust. Betty worked like anything.

Narrabeen in 1946 looking north to Lake. Image d1_36505r GPO locations. Courtesy State Library of NSW.

When I got out the Army I came straight over to Narrabeen. We were living in the temporary dwelling at the back of Gondola Street. About ’48, we had two little girls by then, my uncle, the one who was the international footballer, was at Crows Nest hotel, he was the licensee and we went to his place near my mother’s for a while, at Bexley. He sold it (the hotel) to a bloke, George Satchel, who was a sports writer way back in those days, who wanted for his daughter. He knew the Secretary for the Housing Commission and said “We’ll get him a place.” And we went from there to a place near Punchbowl in temporary housing for about 12 months. Then we went to East Hills for a while before we came back to Narrabeen. I was still at Crouch’s then.

I decided to go to York Motors, or Lancaster Motors as it became known. I was offered a job and I took it. This was at Greenacre or Chullora as we call it at a place called S&M Fox. They were doing a lot of work for York Motors. They were bringing out at this time, this was early 1951, and selling like hotcakes, Morris trucks. One particular model was selling like anything. I was the inspector. We had a couple of blokes from our production company checking them while they were making them too. I was passing them; if they weren’t up to scratch I’d put a list on them of what had to be done. We lived at East Hills then; I could take a vehicle home each night and bring it back in the morning.

By 1952 or 1953 the work slowed down a bit, they were selling less trucks. I moved back to Steammill street, Darling Harbour, which was our headquarters and was part of the delivering; Morris minors etc. when they’re being delivered you had to put number plates on and they had me fixing things; you know, tail light is not working, that’s sort of stuff. I got sick of that so Bill Duncan, who was Betty’s stepfather by then, had put in for a taxi, which were better then hire cars then. We used to come over and they kidded me to put in for one of these hire cars. I was still playing tennis then; my last competition was around then; in the Illawarra.

I’d play there on a Saturday then hurry back here to drive the taxi on a Saturday night and Friday night. In those day cabs were pegged; there were four Narrabeen cabs. There was only two at Dee Why then because Dee Why wasn’t as big as Narrabeen then, and Manly too. There were restricted cabs and unrestricted cabs; unrestricted cans could go anywhere whereas the restricted cans the idea was to keep in that area. A restricted cab for say, Narrabeen, couldn’t go to Manly.

What was your first car in the cabs?

What was your first car in the cabs?

A Vanguard; a standard Vanguard, black it was. You’d go up to the War Veterans home, that winding bit, and the damned thing would jam in gear and you had to get out with a lever to knock the thing back into gear. That was 1954, when I started driving the cab. We were the 14th cab in Manly Warringah.

So you bought this place at Ingleside in 1955?

I first put a fifty pound deposit on a place at Aileen Avenue, a place owned by a Mrs Newman. I was getting the loan through DVD and they came out to check it and advised me not to get it. They said the roof was jerry-built, probably built during the war and no good. So we didn’t get it. Then I head this place was up for sale, the lady had died. I offered two thousand pounds and the son who was in New Guinea took it.

We’d go down to East Hills, there were four or five shops there, big grocery shops, and buy with our five pound note big bags of everything we needed; bulk bags of everything. It was right where the train line ended there. I put a big six foot wire fence up over there. Our young fella, when he was young, he’d wander across the road to get on the train, only four or five he was then. He liked the trains.

I got my cab on seniority because I’d been driving for so long in September 1973. I met my second wife Elizabeth Leniham, who had already been driving a cab, a few years prior to then. When I got my cab she said “I want to come and drive with you.”

She lived with her brother at Narrabeen and a couple of times I’d give her a lift home after her shift. We got married in July 1974. We had a lot in common, she liked reading like me, that sort of thing.

There was a car at Dee Why that was already painted in the Manly Warringah colours so I got that. My cab was then 142. A fellow that worked on the radio, John Beady, used to call me ‘One for Two’ so I got that nickname ‘1 for 2’ and that stuck.

Was the most interesting cab ride you ever had?

At night time it would be alright; I remember one fellow I used to pick up and would take him to Lithgow. He lived in Manly or had a woman friend, I think he lived at Newport. At any rate, he’d get me to run him to Lithgow to visit his brother there. This one time he bangs on the door to his brother’s home and the brother says “Go home you silly bugger.” And I had to bring him back!

Another time I got a job up to Newcastle when the Queen was out here and coming back there were police cars everywhere, lots of traffic, and the money I got for that job wasn’t equal to what I would have made here. Some of them would play up with you and the best thing was to hit them first, not wait for them to hit you; that would straighten them out. You wouldn’t do it if there were numbers, two or three of them.

One night, in town; I stopped for this bloke who was leaning against a post in Redfern about midnight. He started going to sleep and I couldn’t wake him up. Another chap went to help me, a Legion cabbie; we couldn’t wake him up. He said “Take him to the Police station.” I was driving a HQ Holden then; he rang Legion and they sent the police out to pick him up.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater and why?

Ingleside. Because the weather’s good, the locality is good. It’s quiet and better then being in the country. I’m 94 now; I wouldn’t want to go from here to anywhere else.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

Well, first of all, I’m friendly with everyone, if you were a female you could say ‘Love everyone’ so I’d say it’s something like that. I’ve never cheated anyone so I’d say ‘exercise integrity in all you do’ too.

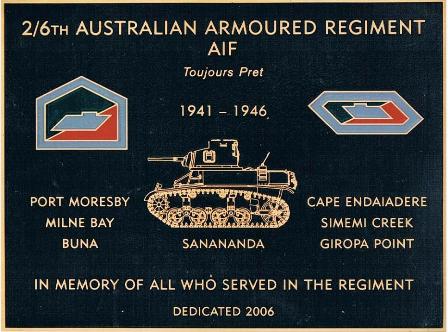

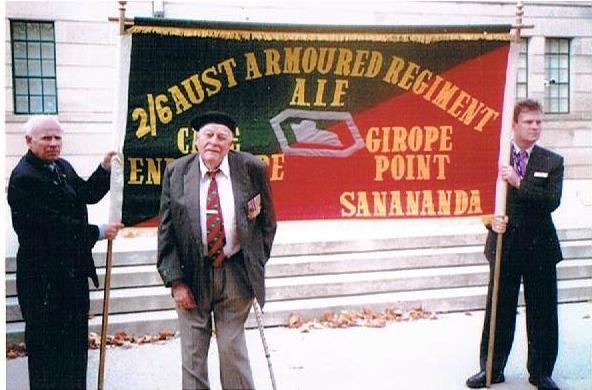

2/6th Armoured Regiment (Australia)

The 2/6th Armoured Regiment was formed in August 1941 as part of the 1st Armoured Brigade of the 1st Armoured Division. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel C.R Hodgson, the regiment recruited mainly from the state of New South Wales. It was initially located atGreta, New South Wales and was equipped with Universal Carriers for training purposes, due to the shortage of other armoured vehicles. Following the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941, the regiment was deployed to defend Coffs Harbour against a feared Japanese attack.

In May 1942 the 2/6th Armoured Regiment was moved to Singleton, New South Wales and was equipped with M3 Stuart light tanks. Later they moved to Narrabri, New South Wales where they took part in large-scale divisional exercises with the rest of the 1st Armoured Division.

In September 1942, the regiment's 'A' Squadron was deployed to Port Moresby and Milne Bay in New Guinea, making the 2/6th the first Australian armoured regiment to be deployed to a combat zone in the Pacific theatre. In December 1942, 'B' and 'C' Squadrons were shipped to Buna on the north coast of Papua to help break the deadlock in the Battle of Buna–Gona. Although the lightly armoured Stuart tanks proved to be unsuited to jungle warfare and suffered heavy casualties, the regiment played an important role in the eventual Australian victory at Buna. In December, seven tanks were dispatched to take part in the fighting around Cape Endaiadere. Three Stuarts were lost on 18 December, while the other four were knocked out on 24 December when they were engaged by Japanese anti-aircraft artillery from point blank range. Reinforcements were brought up, though, and an attack was put in at Giropa Point on 29 December, although difficult terrain prevented a link up with the infantry. Further attacks occurred in January 1943 around the Sananada Track. In April 1943 the regiment was relieved and returned to Australia. Upon its return to Australia the 2/6th Armoured Regiment was incorporated into the 4th Armoured Brigade, which was the Australian Army's specialist jungle armoured formation. The regiment was transferred to the 1st Armoured Brigade Group in Western Australia in early 1943, however, and did not see further combat. After the 1st Armoured Brigade Group was disbanded in September 1944 due to manpower shortages and the decreasing strategic need for armour, the regiment operated as an independent formation until it rejoined the 4th Armoured Brigade in July 1945.Following the end of hostilities, the 2/6th Armoured Regiment was disbanded in February 1946.[During the course of its service it lost 15 men killed in action or died on active service, while members of the regiment received the following awards: one Military Cross, one Military Medal and seven Mention in Despatches.

2/6th Armoured Regiment (Australia). (2011, February 23). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=2/6th_Armoured_Regiment_(Australia)&oldid=415430041

Copyright Les Ball, 2012. All Rights Reserved.