July 29 - August 4, 2012: Issue 69

Mona Vale Outrages

By George Champion OAM

“As one wends his way along through the bush, and Mona Vale opens out before him, he stands to behold and enjoy the novel view that presents itself; it is so secluded and quiet, and yet so grand, with the rugged ridges on the one hand, and the turbulent ocean on the other, that it singularly impresses the visitor, who becomes eager to learn its history, and feels sure there must be many pleasant reminiscences to tell of past occupants. What a sad mistake! What fearful trials and losses and disappointments have been experienced here. Its history should be written in blood, for if ever red-handed crime flourished in any country, it flourished and triumphed here, till it brought ruin and death to honest people; and justice, outraged beyond bearing, rushed in and brought the delinquents to punishment.” The Town and Country Journal 6 January 1877.

The isolation of the peninsula in the 1800s made it difficult for the law to be properly policed in the area. Some grants of land were fairly small, whilst others by comparison were large. Inevitably friction occurred between some of the neighbouring farmers. There was always a temptation to allow cattle to trespass on another’s land for grazing purposes, and to build up herds by illegally acquiring someone else’s cattle. Horses too were then a valuable commodity, and were often stolen. When new occupants moved on to a property, they were quite often dissuaded from staying by means of arson.

One well known family which acquired land quite early in the vicinity of Newport and nearby, was the Farrell family. As there were three John Farrells, for the sake of clarity, they are often referred to by the numbers I, II, or III.

Not long after David Foley’s brutal murder on 8 November 1849, his daughter Mary Ann married the Foleys’ northern neighbour, John Farrell II on 8 February 1850. He was the son of John Farrell I and was born in the Colony in 1823. It appears that David’s widow, with her five children, stayed on at Bungin (now named Mona Vale) for some years. The Farrells, who had less land but more cattle than Foley, now had the opportunity to use Bungin land for their own grazing.

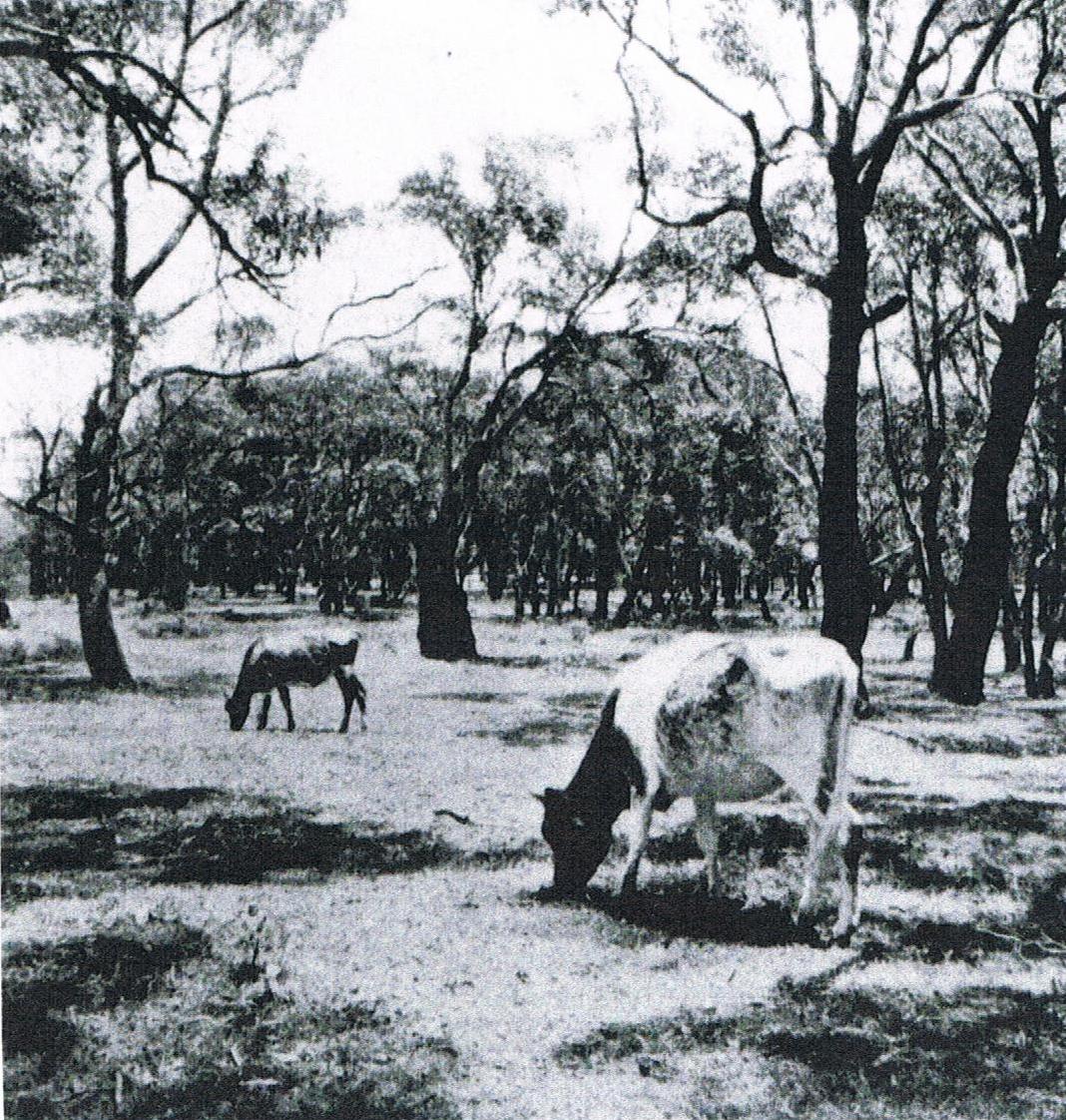

In 1858 Henry Bate, his partner Fred Berkelman and their families leased Bungin from Captain Benjamin Darley. In his book Samuel Bate: Singular Character the author Frank Bate says, “Here they ran about 40 cattle including 20 milkers, with pigs and farm horses. Each fortnight Elizabeth [Henry’s wife], driving a horse and cart, would deliver the butter produced to Manly wharf from where it was shipped to Sydney for sale. Potatoes and other crops were grown and to reduce the need for cash, bartering of labour or produce was commonplace between neighbours. With six Bate children, the Berkelman family and two employees the household was a large one. Additional acreage was rented to supplement existing pastures. ... Many years later, Mary Bate, daughter of Henry and Elizabeth, wrote that despite the hopes which the farm at Mona Vale gave rise to, it eventually failed because of the activities of cattle duffers who frequently drove off and killed their cattle.”

In 1858 Henry Bate, his partner Fred Berkelman and their families leased Bungin from Captain Benjamin Darley. In his book Samuel Bate: Singular Character the author Frank Bate says, “Here they ran about 40 cattle including 20 milkers, with pigs and farm horses. Each fortnight Elizabeth [Henry’s wife], driving a horse and cart, would deliver the butter produced to Manly wharf from where it was shipped to Sydney for sale. Potatoes and other crops were grown and to reduce the need for cash, bartering of labour or produce was commonplace between neighbours. With six Bate children, the Berkelman family and two employees the household was a large one. Additional acreage was rented to supplement existing pastures. ... Many years later, Mary Bate, daughter of Henry and Elizabeth, wrote that despite the hopes which the farm at Mona Vale gave rise to, it eventually failed because of the activities of cattle duffers who frequently drove off and killed their cattle.”

It was at this time that the name “Mona” or “Mona Vale” began to be used. “Mona” is a Celtic word meaning “high-born”, and the name seems to have had some popularity in the Colony.

On 5 June 1860 the following advertisement appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald:

“TO LET, MONA VALE, consisting of 700 acre grant, but by measurement about 2000 acres [a gross exaggeration - authors]. It will carry about 300 head of cattle, besides the fenced in paddocks, will milk about 60 to 70 cows all the year round. There is coals and a good wharf on the estate, the fire-wood will three times pay the rent, as the wharf and other conveniences are greater than any other place in the colony for the Sydney markets. For particulars apply by letter to H.J.BATE, at Mr. F.R. Robinson’s ironmonger, George-street, opposite Sydney Markets.”

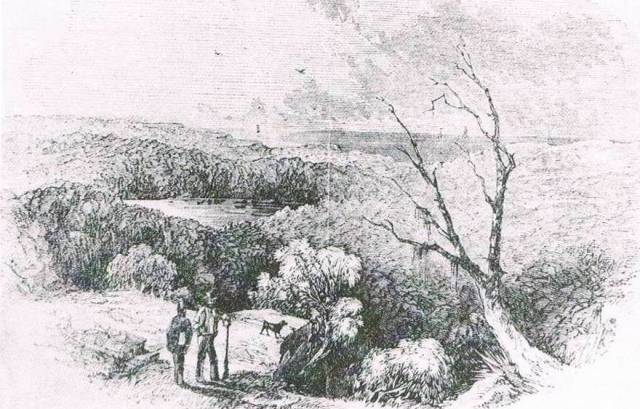

The advertisement was repeated, and by 24th October 1860 Mr Lush, with his family, had been installed as caretaker. The Lushes were in occupation when Charles de Boos and his companions called at the farm in 1861. De Boos described their arrival at the homestead:

The advertisement was repeated, and by 24th October 1860 Mr Lush, with his family, had been installed as caretaker. The Lushes were in occupation when Charles de Boos and his companions called at the farm in 1861. De Boos described their arrival at the homestead:

“... it is so nestled down amidst the sand hills that surround it as to be unperceived until you are within a hundred yards of it. We found it a neat looking little place so far as outside appearance went, but evidently the worse for wear, like every building we had then met, and I may add, like every one we afterwards came to in the district. It had, at one time, been a dwelling of some pretension, as was evident from the stabling, fowl-house, and dairy, now somewhat dilapidated; and from the enclosed garden in front of the house, in which flowering plants, roses, pinks and geraniums, struggled manfully for existence with the straggling couch grass, amidst which they were all but buried. A large stockyard, in which was a shed, covering in the milking bail and calf pen, lay to the north of the house, the venerable grey hue of the timber speaking for the antiquity of the construction, as well as for the durable characters of our colonial timber, since the posts, though somewhat eaten away by decay below the surface, were still sound and hard as flint above it. At the back of the domicile, or eastward, the high sandbanks sheltered it from the fierce sharp breezes from the ocean, through the surf, as it curled and dashed upon the long sandy beach, roared and moaned incessantly in such close proximity as to be inconvenient until the ear had got accustomed to the sound. To the right, or northerly, a high range terminating in a rocky headland which jutted far out into the sea, and abruptly ending the long line of beach, arose almost bluffly from the edge of a small paddock reserved for a kitchen garden; whilst southerly a close belt of honeysuckle [i.e. banksia] protected it. To the front or westward, the view was open, extending along the broad clear flat which I have before spoken of as reaching to the head of Pittwater and a large portion of which I could now see was enclosed, thereby forming a vast paddock.”

A squall of rain was approaching and Mrs. Lush welcomed them inside, placing them in comfortable seats around the log fire, over which there hung a large three-legged iron pot which steamed and bubbled, sending forth a captivating savoury odour. The squall passed, and in the drizzling rain which followed, the Lushes’ seventeen year old daughter took out coats for her father and brother. When they came in, they all sat down to eat the contents of the pot, followed by bread and honey. That night they had beef and pumpkin for supper.

“Mona Vale” continued to be advertised for lease until July 1862. About this time James Therry arrived in the Colony with his family. He was the nephew of the Rev John Joseph Therry, who had substantial land holdings to the north of John Farrell II. James Therry took the lease of “Mona Vale” and renovated the house for his family. However, before they could occupy the residence it was destroyed by fire, on 5 November 1862. Suspicion fell on John Farrell II, as Therry had already had occasion to speak to him about his cattle trespassing on “Mona Vale”, whereupon Farrell had said that Mr Therry would not remain on the farm for six months. At the inquest into the fire, however, the jury concluded that “the said premises, situated at Mona Vale, Pitt Water, were wilfully and maliciously set fire to, but the evidence does not clearly show who the guilty party or parties are.” According to the Sydney Morning Herald, Therry was then threatened that if he did not leave the district he might expect further injury, not only to his property but to his person.

The Therry family persevered, living in tents and a makeshift hovel. A reporter from the Empire, who visited the remains of the ruined homestead, said he saw standing near what had been the hearth of the burnt dwelling-house, a woman, who, from her manners and conversation, was evidently a lady. A number of young children were also gathered round a small hovel which had been erected on a rising ground beyond.

Several horses were also stolen from the Therrys. John Farrell took Mr and Mrs Therry to court for using insulting language, and they were both fined. Farrell had Therry charged with cruelly beating a heifer, for which he was fined forty shillings, although Therry and his daughter denied it. James Therry then took Farrell and two of his employees, Henry John Wright and Malcolm Turner, to court for destroying his fences and six trees, which offences they admitted, John Farrell giving as his defence that he could not use the new public road, proclaimed in June 1860, to get to his farm. What was more, he said he needed a road sixty-six feet wide, the nine feet of fence which had previously been broken down not being enough for him. The court imposed fines on Farrell and Wright and Turner was sent to gaol for fourteen days.

Several horses were also stolen from the Therrys. John Farrell took Mr and Mrs Therry to court for using insulting language, and they were both fined. Farrell had Therry charged with cruelly beating a heifer, for which he was fined forty shillings, although Therry and his daughter denied it. James Therry then took Farrell and two of his employees, Henry John Wright and Malcolm Turner, to court for destroying his fences and six trees, which offences they admitted, John Farrell giving as his defence that he could not use the new public road, proclaimed in June 1860, to get to his farm. What was more, he said he needed a road sixty-six feet wide, the nine feet of fence which had previously been broken down not being enough for him. The court imposed fines on Farrell and Wright and Turner was sent to gaol for fourteen days.

As the feud progressed, there were charges of trespassing, perjury, and finally cattle stealing.

The trial of John Farrell II, charged with having stolen ten cows, the property of James Therry, began in the Central Criminal Court in Sydney on 30 September 1863. The jury could not agree on a verdict and a retrial was ordered.

The feud raged on unabated. Therry’s horses were stolen, charges against Farrell and Turner for assault were dismissed, and charges against Therry for perjury were withdrawn.

On 29 September 1864 four charges of cattle stealing and receiving were preferred by James Therry, the defendants being John and Mary Ann Farrell, John Farrell the younger (John Farrell III born 1851, son of John Farrell II), Thomas Collins, Lavinia Collins and Frank Poyner.

The breakthrough came when Malcolm Turner, who had been brought up by the Farrells from the age of seven, apparently had had enough, and worked with an experienced detective, Daniel McGlone, to give evidence against the Farrells. After preliminary hearings, John Farrell II appeared in the Central Criminal Court on 28 December 1864, indicted on five counts concerned with stealing and killing ten cows. After hearing evidence for three long days, the jury found Farrell guilty of maliciously killing cattle.

In sentencing Farrell Judge Wise said, “The crime of which the prisoner has been found guilty was of a most heinous character, and rendered more atrocious by his attempt to fix a charge of perjury on an innocent man. His Honor then sentenced the prisoner to be imprisoned and kept at hard labour on the roads or other public works of the Colony for the period of seven years. Farrell was released after serving four and a half years.

On 27 January 1865 Mrs Lavinia Maria Collins, who was also about to face legal proceedings, died from injuries received, when her dray upset in Manly.

The trial of Mary Ann Farrell (wife of John Farrell II) began in the Central Criminal Court on 6 February 1865, before the Chief Justice. She was charged with stealing thirteen calves. Once again it was Malcolm Turner’s evidence that proved to be decisive, as he had shown Detective McGlone the remains of calves dug into the ground in Farrell’s orchard, near Pine Street, Manly. McGlone also had the remains of calves he had found in a gully about seven or eight hundred yards away from the Farrells’ Pittwater farm.

The trial of Mary Ann Farrell (wife of John Farrell II) began in the Central Criminal Court on 6 February 1865, before the Chief Justice. She was charged with stealing thirteen calves. Once again it was Malcolm Turner’s evidence that proved to be decisive, as he had shown Detective McGlone the remains of calves dug into the ground in Farrell’s orchard, near Pine Street, Manly. McGlone also had the remains of calves he had found in a gully about seven or eight hundred yards away from the Farrells’ Pittwater farm.

After two days, the jury returned a verdict of guilty, with a recommendation to mercy, on account of her family. The next day, the Chief Justice sentenced her to be kept at light labour in the gaol at Sydney for the term of three years. She was released after serving two and a half years.

James Therry’s evidence showed that he was ruined as a farmer, and left with only two horses. From his losses reported to the police, and published in the New South Wales Police Gazette in 1863 and 1864, it can be calculated that James Therry lost at least forty head of cattle and twelve horses. To make ends meet during these difficult times, Mrs Therry ran a boarding house in Manly.

Malcolm Turner was then charged with perjury by the Farrells’ solicitor, but was found not guilty.

The following descriptive extract from an article titled “A Ride to Barrenjoey”, in the Sydney Morning Herald, 22 March 1867, speaks for itself:

“It is the same until you reach the farm once occupied by the Farrells, who were two years ago convicted of destroying cattle owned by a farmer named Terry [Therry]...Beautiful and interesting as the country is from Manly Beach to Broken Bay, one feature presents itself of an unpleasant character, and that is the apparent decay of the farms – it is evident that a large quantity of land was under cultivation at one time in this district, ‘ruthless ruin’ seems, however, to have seized on what a few years ago must have been an animated scene. The land now lies fallow, and save for the feeding of a few cattle, and sustaining about fifty people, is of no use whatever in contributing its quota to the general welfare. No doubt, the comparative difficulty of communication with the city by land has something to do with this state of things, but it is impossible not to believe that the chief cause of this inertia is to be found in the bad reputation of the district for agrarian out-rages. The history of the Mona Vale case reveals a condition of society, within a few miles of Sydney, that might well deter persons from settling there; and though the arm of the law fell on some of the evil-doers in that locality, there is now too much reason to fear that similar outrages will again disturb the district, as, only a few weeks ago, Mr Wilson found a valuable bull of his, and a heifer belonging to another person, grazing on his land, both dead, having been shot evidently by design. This is a serious matter to the owner, but it is still more serious to the community in the demoralisation likely to ensue from these villainous practices. It is the duty of the authorities at once to take such steps as may ensure protection for honest and hard working men, who with the responsibilities of large families to support and educate, are striving hard to do so, and are willing to contend with climatic variations, and other disadvantages, but cannot stand against the treachery of scoundrels who stealthily destroy the means by which they live. A reward for the discovery of the offenders and the presence of a well mounted policeman in the district would probably lead to good results; and above all, in case of conviction, a punishment that shall remove them from the district for some years.”

It should be noted that Thomas Wilson was now the lessee of “Mona Vale”, and that he was experiencing trouble similar to that encountered by previous lessees.

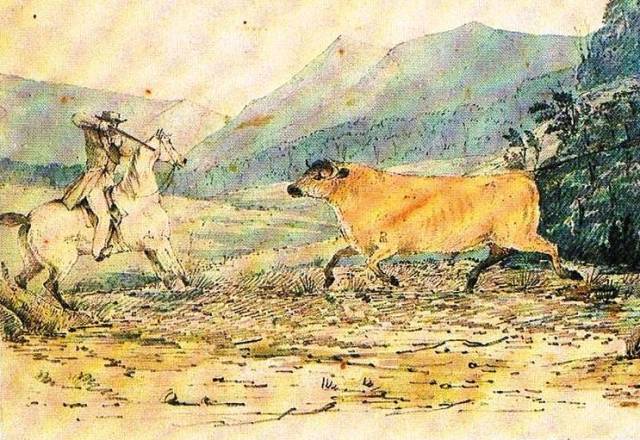

On 4 August 1870, Thomas Wilson saw John Farrell III on horseback about an hour before sunset, driving some of Wilson’s cattle towards Farrell’s own place. A red and white heifer, about three years old and within six weeks of calving, was found to be missing. Wilson reported the matter to the police, who went to Farrell’s with a search warrant. In the stockyard they found a dead calf and entrails covered with corn stalks. They also found fresh beef in a cask. In August 1870 legal proceedings commenced against John Farrell III in the Water Police Court (now a museum in Phillip Street, near Circular Quay, Sydney). In an apparent act of retaliation, John Farrell II charged Thomas Wilson on 14 October with allowing two bulls to trespass on his property and damage growing crops. Wilson was fined eight shillings, without costs.

On 4 August 1870, Thomas Wilson saw John Farrell III on horseback about an hour before sunset, driving some of Wilson’s cattle towards Farrell’s own place. A red and white heifer, about three years old and within six weeks of calving, was found to be missing. Wilson reported the matter to the police, who went to Farrell’s with a search warrant. In the stockyard they found a dead calf and entrails covered with corn stalks. They also found fresh beef in a cask. In August 1870 legal proceedings commenced against John Farrell III in the Water Police Court (now a museum in Phillip Street, near Circular Quay, Sydney). In an apparent act of retaliation, John Farrell II charged Thomas Wilson on 14 October with allowing two bulls to trespass on his property and damage growing crops. Wilson was fined eight shillings, without costs.

After much legal wrangling and disagreement, the case against John Farrell III was eventually brought to the Central Criminal Court, but the jury could not agree upon a verdict. During the protracted proceedings, little Blanche Wilson, aged two years and two months, drowned in a shallow pond, about eighteen inches deep, on Friday, 11 November 1870. She had been playing with other children near the waterhole on Mona Vale farm, where the men were employed in making hay. Apparently she had overbalanced into the water on to her face, and was unable to extricate herself from the reeds. Thomas Wilson received this shocking news at the Central Criminal Court.

eventually brought to the Central Criminal Court, but the jury could not agree upon a verdict. During the protracted proceedings, little Blanche Wilson, aged two years and two months, drowned in a shallow pond, about eighteen inches deep, on Friday, 11 November 1870. She had been playing with other children near the waterhole on Mona Vale farm, where the men were employed in making hay. Apparently she had overbalanced into the water on to her face, and was unable to extricate herself from the reeds. Thomas Wilson received this shocking news at the Central Criminal Court.

The case against John Farrell III was brought to court again in February 1871, and this time the jury returned a verdict of guilty. John Farrell III was sentenced to be imprisoned in Parramatta Gaol for three years, with hard labour, by the Chief Justice, who said he was as certain of his guilt as he was of his own existence. Farrell was discharged from Port Macquarie Gaol two and a half years later, in August 1873.

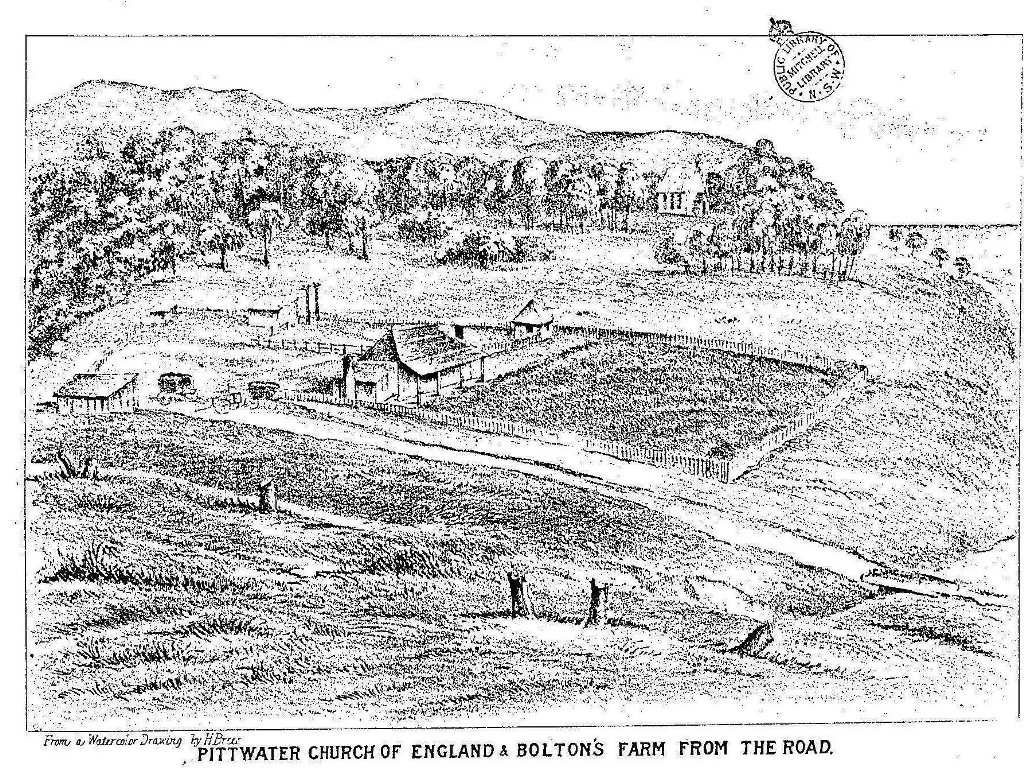

On the 21 September 1871 a beautiful little chapel was opened near Mona Vale farm, on land donated by Mr Benjamin Darley. This small church was the first to be erected in the area, and about one hundred people assembled for the occasion. The Sydney Morning Herald reported: “Those who have contributed to this good work have conferred an incalculable benefit upon a locality, where until recently – before a service was commenced there by the late incumbent, the Rev G. Gurney - lamentable to say, were to be found adults who had never heard the Word of God.”

Thomas Wilson remained at Mona Vale until about 1872, when he went to Little Mackerel Beach. The tenancy passed to William Boulton. He was at Mona Vale until January 1882, when he took out a publican’s licence for the Newport Hotel.

Soon after this, land subdivisions increased and the lifestyle of the local inhabitants changed greatly.

Main source

Manly, Warringah and Pittwater 1850-1880 by S. and G. Champion. Killarney Heights NSW, 1998.

Images

1 A view of Pittwater from Illustrated Sydney News, 1854. (Courtesy State Library of NSW)

2 Cattle grazing at Pittwater from The Sydney Mail, 28 December 1938 page 12 (Courtesy State Library of NSW)

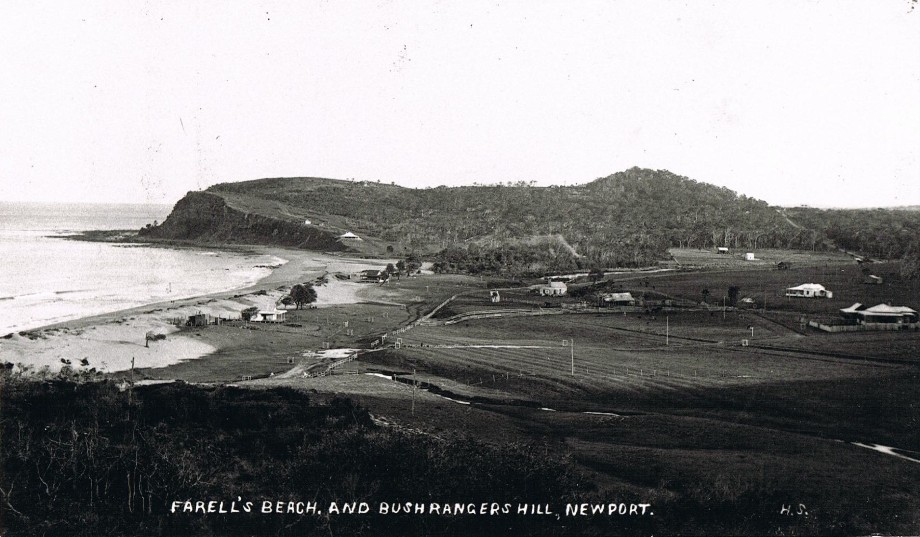

3 Farrell's Beach and Bushrangers Hill, Newport from Small Picture File, Courtesy Mitchell Library.

4 Farrell's cottage, Newport Beach. Photograph - by and Courtesy Jeanne McGlynn.

5 Shooting a bull. Watercolour, 'A bush incident' by Abraham Lincolne from his Australian Sketches, c.1838-44. (Courtesy Mitchell Library). Copied from Australians 1838 page 154.

6 John Farrell II and Mary Ann Farrell, early 1870s Courtesy Manly Library Local Studies.

7 John Farrell III. Photograph - by and Courtesy Jeanne McGlynn.

8 Pittwater Church of England and Bolton's Farm from the Road; illustration from the Pittwater and Hawkesbury Lakes Album. 1880, Courtesy the Mitchell Library

Copyright Shelagh Champion OAM and George Champion OAM, 2012. All Rights Reserved.

|

|