October 19 - 25, 2014: Issue 185

Patrick McGrath

Patrick McGrath

A lot of firsts mark Patrick McGrath’s life, he introduced Lock Crowther multihulls to Canada, always sailed with women crews in racing while in Toronto as they ‘were better sailors – had a 'killer instinct' and ‘were determined to win’, developed an epoxy that could eliminate the rot in wooden vessels and pursued a lifelong passion for aircraft that translated through to his passion for mulithulls, among many other things. Having met this wonderful gentleman at the RMYC Multihull Division's Lock Crowther Regatta of 2014, we couldn't wait to share his wonderful experiences.

With astounding recall for dates and events, Mr. McGrath's path is best told in his own words.

When and where were you born?

I was born in Portsmouth, England in 1928. I was born into a military family. As a result I got involved in boats and aeroplanes and of course Portsmouth is a Navy town, it was Lord Nelson’s base.

When I was five we left and went up to the Midlands, to Nottingham. All of my upbringing up until I left school was in Nottingham. We did all sorts f things while I was growing up. Nottingham had cycle pathways right through it and we would move around on roller skates. We then graduated to bicycles.

Where did you go to school?

There is a bit of involvement in that; I had two sisters who both came down with tuberculosis. They went into the sanatorium in Nottingham. One recovered enough for them to send her down to the Isle of Wight to the Hospital for the Diseases of the Chest and the younger sister they unfortunately sent home to die.

My father didn’t want me around while this was occurring so he had me put into an orphanage. I was there for a year and then came back home. My mother left home and went down to be with my sister who had recovered, to look after her at my grandmother’s house.

My father found it difficult to look after me on his own and so put me in a private boarding school, Radcliffe House school, run by a lady called Miss Munro, in a suburb of Nottingham called West Bridgeford. People referred to it as ‘Miss Munro’s’. There were about three boys and five girls boarding there – at the end of the first term a few of the boys left and then again at the end of the second term. I was left there with all these girls. As a result I did a lot of singing and I learnt how to dance – all those old time dances like the Highland Fling, Strip the Willow, etc:

My father met another lady, bought a house and I then went to live at home. My father then sent me to Nottingham High School – the English education system is a different from what is in Australia; in England they are called “public Schools’ but in England a public school is not like a public school here – a pubic school is a private school and usually quite illustrious establishments. If you have been or are a ‘public school boy’ it opens lots of doors to you.

Nottingham High School was originally called ‘Mellor's due to being founded by Dame Agnes Mellor in 1513. It was a very prestigious high school. I didn’t do very well at that school although I was good at things like English, Geography and History and I was always top in Art. I was bad at Mathematics and next to bottom in French.

Because of the nature of the school they had an Officers Training Corp of which I was obliged to be a part of. Towards the end of my time there – 1943 to 1944 – I switched to the Air Cadets.

My father arranged for me to sit what was called the ‘Tri Forces Exam’; in which you took an exam for an apprenticeship and then one of the Services would agree or not agree to take you in as an apprentice.

I passed the exam and at the age of 15 went to become an aircraft apprentice. I left home one month before my 16th birthday and went into the Royal Air Force.

The apprentice scheme was such that when you went in as an apprentice you had to sign on for 12 years from the age of 18. you had to do a 3 year apprenticeship first.

I wasn’t daunted by this as I was looking forward to it – I’d always been attracted to aeroplanes. I started making model aeroplanes when 11 and of course none of them flew but eventually they did and I got to be quite good, not only at building model aeroplanes from kits but also designing my own planes and building and then flying them.

So I was already very Air Force orientated.

To cut a long story short; I did three years at RAF Halton and passed out in the top 50 out of 250. As a result I was eligible to go to a selection board to see if I was suitable to be selected to be an officer and fly. For some reason out of this 50 only 3 were chosen and I was one of those.

I went to the Royal Air Force College at Cranwell to learn to fly. I was there for a couple of years and didn’t like it at all; it was very class conscious and I’d been brought up as a middle-class person and an apprentice which was a really rough go because this included kids from all levels of life and they could be a pretty sacrilegious bunch. Others were really great. I was one of the last to be soloed on Tiger Moth biplanes.

I was then sent to RAF Cottesmore,where I did my final advanced flying training. I flew on Harvards. We were the last entry class to fly these; I think they brought in Avro Tutors shortly after.

I was then sent to the No 4 School of Technical Training at RAF St Athan’s, in Wales, where I was sent to do more technical training and bookwork which would qualify me for an Air Force Degree in Aeronautical Engineering.

I wasn’t good enough to be a fighter pilot but was ok to be a bomber on multi engine planes; I was posted to an Avro Lincoln squadron OTU (Operational Training Unit) and was only there for three weeks before I was reposted onto the OTU for B29 Washingtons.

The story behind this is that during the Korean War the Americans were really tied up in Korea but were afraid that Russia may take the opportunity to make a move in Europe during that time. The British Air Force was really run down at that stage, the second world war had taken a huge toll on the British Forces and when the Labour Government came in they cut back spending on everything.

I went on to the Avro Lincoln, which was the development of the Avro Lancaster Bomber; they had developed the Lincoln for use in the Pacific but by the time they got the plane ready to go over there the Atom bombs had been dropped and the war was over.

Compared to the B29 bombers that the Americans had, the Lincoln was a pretty agricultural plane – I was posted onto No.: 35 squadron OTU and on to these beautiful B29 bombers, which were called the ‘B29 Washington’. The Americans lent Britain 80 of these.

For the next two years I had the best time of my life flying these beautiful, great quiet and powerful aeroplanes in Lincolnshire at a place called RAF Marham. They were upholstered inside, pressurised, heated, every seating position had an ashtray and a soup warmer – you could get a can of soup, place it in the slot, press the button and in one minute you could take the top off and drink it.

We never flew lower than 20 thousand feet, sometimes 25 thousand feet and on the odd occasion 38 thousand feet; we could only fly there for one hour at that height as otherwise they had to change all the engines – they would get too hot, the thin air flow wouldn’t cool them properly and the Wright Cyclone engines were a rotten engine – they were the Achilles heel of the B29’s.

There were lots of B29’s lost in the Pacific not through being shot down or pilot error but because the engines failed.

So during the Korean War we were flying these planes in Europe to guard against the Russians making a move there. The B29 was a long haul plane; you could fly very long distances with it and we would fly flights up to 23 and a half hours with it non-stop. There was no in-flight refuelling in those days. Our route was taking off from Lincolnshire and down over the Alps, across the Mediterranean, right along the North African coast to Alexandria and then we’d turn left and fly up through the Bosporus and then up over southern Germany and through back into the North Sea and then return home to land. We’d take off at sunset and land at sunset the next day.

That was good stuff; they talk nowadays about the dangers of taking drugs – they used to give us Benzedrine to keep us awake!

When the Korean War was over the Americans wanted all their planes back.

Because I had flown American planes I was transferred onto the Lockheed Neptune, which was an American twin-engine plane which was an anti-submarine aircraft. It was more powerful than the Lancaster with four engines, because there was 3000 horsepower for each engine. It was a wonderful plane to fly.

I was transferred to Coastal Command and flew these Lockheed Neptune planes for the rest of my time during the Cold War. I was posted right up into the very North of Scotland to a place called RAF Kinloss which is about 33 miles east of Edinburgh on the Moray Firth – I was there for four and a half years and that was four and a half of the best years of my life.

Scotland was cold, we did get six feet of snow on occasion in the Winter, but the Summers are beautiful, the scenery is beautiful and it was a great time.

We were flying these machines during the Cold War, and believe me, the Cold War was very close to being a Hot War; we never flew without being fully loaded for action. Every sortie, for example, we would fly 8 hours one day, and have the whole of the next day off, we always flew with 8 x 300 pound anti-submarine depth bombs, 16 x 6inch rockets, 2400 rounds of half inch ammunition for our 10 machine guns and we had a two million candlepower searchlight on the wingtip and an attack radar on the other wingtip. If when we were out flying it came over the radio that we were at war all we had to do was flip a red cap off the arming button and everything on board the plane would be live.

We would fly around, at a very low altitude, flying at 1500 feet. It was rough, waves on a very rough day at 40 feet high making the plane bucket around; there was a lot of airsickness. I would go down from the cockpit and make bacon and eggs in the galley for the crew, nobody else would do it because it made them airsick.

What people didn’t understand is that the Russians had submarines that were way ahead of ours. They would submerge and have a snorkel which would take in air and pump out exhaust; they could run their diesel engines under the surface. That would keep their batteries up so they could use their electric motors if they had to deep dive.

But the exhaust fumes from their snorkel would leave a trail and we had a device called a ‘sniffer’ on board our plane which could pick up a trail of fumes at a distance of 70 miles.

When we were going along and would suddenly get a click on the sniffer, we’d immediately turn around and take another click. This would give us a bearing on where the submarine was. If the submarine had its radar on, which it would have had, we would switch on our radar and go one, two and a half turns and stop; if we had the very powerful radar on we could pick up a snorkel at 120 miles away…but so could the submarine and get a bearing on us.

We would catch Russian submarines on the surface or just below it – this would be in the North Sea or the North Atlantic, in International waters- we’d go right up the coast to NOVAYA ZEMLYA which is way beyond the North Coast of Sweden.

Anything that came out of the Baltic had to go around there to get into the Atlantic and this is the area that we covered.

We’d come down to 50 feet over the sea. You can’t fly at hands on at that low a level and so the plane would be on flight control. We had a radio altimeter which would communicate with the automatic pilot – the plane flew itself. If it was night-time we’d switch on the searchlight and if a submarine was on the surface we’d illuminate it.

We would drop things called ‘sono-buoys', which could locate and track a submarine.

One day we got a warning from the Air Ministry not to approach within 40 thousand feet of any submarines whatsoever as they were now armed with Surface to Air Missiles (SAM’s).

When did you leave there?

I was getting towards the end of my 12 years. We had friends who had left the Air Force and gone to Canada and were sending us letters filled with praise on the wonderful life they were having there. People must remember that In Britain, even then, some things were still rationed after the second World War and this was the early 1950’s.

We decided that we’d go to Canada. I wrote to an aircraft company in Canada, the Avro Aircraft Company, where they were developing a new fighter plane which nobody else had as yet, listing my experience and received a reply stating they were interested subject to a face to face interview.

I still had 10 months to go on my 12 years. At that time the new government came in with its program of austerity and my unit, No.: 217 Squadron, was disbanded. The aeroplanes were sent back to America and all of us were sitting around waiting to be reposted to other units. In the meantime I got a job going through the Queen’s Regulations and found in there a part which stated that in special circumstances permission may be given to get relief from your contract to leave the Air Force.

I wrote a letter to the Air Ministry showing them this letter from Avro in Canada and received a letter back stating ‘agreed – you are released within current date’; and six weeks later I was out of the RAF and on my way to Canada.

I was 29 when we went to Toronto, Canada.

What was your position with Avro in Canada?

I became part of the Flight Test and Development Team. We had a lovely three level house built by Johnson Brothers for 11 thousand dollars through an Avro Company affiliation with a local bank – I was happy with that.

Unfortunately the politicians all became involved in the Avro Arrow development, and the Americans were jealous as heck of the twin engines in particular, which was developed by Orenda Engines for this incredible plane and they cancelled the whole thing one afternoon. They cancelled it like that at 2.30 in the afternoon and 14 thousand people were instantly out of work. 10 thousand at Avro and 4 thousand at Orenda

So what happened to those already built?

They had three of them already flying and seven on the production line; they just took them out on the tarmac and cut them apart with torches. They then took all the plans, all the instructions and design materials, masses of it, made a huge pile at the intersection of the runways, hosed it with petrol, and set it alight.

They obliterated every aspect of the Avro Arrow.

On the day we landed in Canada, the 10th of June 1957 a new government came into power in Canada and John Diefenbaker, then in charge of this Conservative government, and who had campaigned on reigning in the Liberal spending, set his sights on the company. In October 1958, to cut costs, the new Conservative government terminated Canadian fire-control and missile development, and renewed efforts to sell the aircraft to the US, just when the US was promoting Bomarc missiles to meet and explode any Sputnik missiles that may come from Russia into Canadian airspace.

RL-204, late 1958 Avro CF-105 Arrow with CF-100 Canuck in background, courtesy Don Rogers - Photograph from private collection.

So what did you do then?

I went home and told my wife I was out of a job – we had two boys.

That evening a man from the Motor Club Membership knocked on the door to renew my membership with the National Automobile League. I gave him my $15.00 membership and asked him about what he did and whether he made a good living. He explained that if he hadn’t made $100.00 that week then it had been a bad week. The average national wage in Canada at that time was $70.00 a week – I thought I was doing pretty well as an engineer getting $92.50 a week.

I had made a pretty penny earlier in the 1950’s in England selling motor cars where you could buy an old car, do it up and sell it for a lot of money as there was a real shortage of cars immediately after the war. He asked me if I was interested, and I explained I was interested in anything that day, and he introduced me to his manager.

This guy Lloyd Dennis came along, a great man, had been a tank commander during the second World War, and he said to come out with him and he’d teach me how to sell Motor Club memberships.

I went out with him and we were on the road for about two weeks. We’d go out during the day and during the evening to sell memberships. We’d stay in motels, which in those days cost $2.00 a night. I did this for 20 months.

I’d met a guy before Avro’s packed up who had a sailboat, a little thing called a Silhouette 18/Mrk II, a New Zealand design, whom I’d go sailing with. One Summer, providing I bought him a new gyb sail, he let me use his boat for my two weeks holidays. This whetted my desire to have a boat of my own… although this had always been so.

Most Air Force stations are placed inland. When we were stationed in Scotland at RAF Kinloss, it was right on the edge of the sea. There was Findhorn Bay right near the air field and at the back of its sandy beach was a thing on chocks called a Dragon, a Dragon yacht. I used to look at this boat and thought it was the most beautiful thing in the world.

I promised myself when I got out of the RAF I would build, buy or get a boat.

In Winter of 1957 in Canada I built my very first boat – a Pram dinghy – and I built it in my living room. It was my first experience at building and sailing a boat. During Spring of1959 we put it on the front lawn with a sign on it ‘$50.00’ and someone came along and bought it like that. (snaps fingers)

I then got into sailboards – now this is not Windsurfing – these were like windsurfers but they had a sail and you sat on it and sailed it like a yacht. The only ones in these days were either the Sunfish or the Sailfish of which the Sailfish was the smaller version. They were darned fast – you needed to learn about sailing, about having to go to windward or how to use a centreboard. So I learnt how to sail fast on a sailboard, a Sunfish, and then this guy who had the Silhouette Mk II and I decided we’d go into business making these things.

We found a company in New Jersey who were popping Styrofoam hulls out of a mould. We bought a bunch of these, fitted them with

masts and sails and called it ‘the Dart’ and started a company called ‘MachCraft’.

When trying to register this company we found we couldn’t – there were too many companies incorporating ‘machine’ – we explained that this was related to speed and the speed of sound---- but were still refused.

We sold a few of the Darts and then, shock horror, they brought in Sales Tax, a 3% Sales Tax. We would sell these boats for $99.95 prior to this and thought it would be too difficult to sell them beyond that so we packed it in and called it quits.

This did whet my appetite for being involved in sail boats though.

In the meantime the main thing to get on with was making a living. I graduated from selling car club memberships to selling these heat measuring devices. These fitted into the base of chimneys and were fitted with a selenium cell which could determine how much smoke was being made and if there was a problem a bell alarm or flashing red light would alert the superintendent of the larger buildings they were installed in to adjust the flue so they weren’t making smoke. At this time penalties for making air pollution were being brought in. I did very well at this and sold lots of units.

I moved from there to working for a pharmaceutical company, Ortho Pharmaceutical as what they then called a Detail Man – my work would involve calling on gynaecologists and obstetricians. The company put me through a six week training course during which you learnt all about female Endocrinology.

As fate would have it this was immediately before they introduced the oral contraception, ‘The Pill’. I found myself going around to pharmacies of a morning and doctors of an afternoon.

I did this for five years and became weary with the ethics of pharmaceutical companies..

I went back to the aircraft industry in what used to be the Avro aircraft offices, only now it was McDonald-Douglas who were making aircraft parts. I began work there as a Contracts Officer. While working there I was approached by a guy who used to be part of what was Orenda Engines which was now Hawker Siddeley Canada. They wanted me to come work for them and offered me a thousand dollars more a year then what I was earning at McDonald-Douglas.

My work there was again Contracts for machinery parts in titanium steel for the engines of turbo jet motors for American helicopters flying in Vietnam.

Throughout this time I was continuing with my sailing, sailing on Lake Simcoe, which is immediately north of Toronto. Beautiful place with lovely surrounds and lots of islands in the middle of it.

During the running down of the Vietnam War the department I was in became redundant and with others I was laid off.

I was fortunate in quickly finding a new position as a Contracts Administrator with a company called Garrett Air Research, an American company. They were making all sorts of stuff for different planes. During the course of my interview with my new boss I found out he was a sailor ---- I got the job.

By now I knew that the aerospace industry is a boom and bust business. I had been working on my own little private business in the background.

In 1966 I realised I’d built a dinghy, built sailboards and then had built a 16 foot trimaran sailboat for my son to sail and then I built a 24 foot Piver trimaran for my family to sail. I contacted what I thought to be the top leading multihull sailboat designers in the world.

I simply said, ‘I’m living here in Toronto. I sail a multihull. I’ve built multihulls. I’ve been the secretary of the AYRA – the Amateur Yacht Research Association – I was the Canadian Secretary of that association – I raced regularly with the Toronto Multihull Cruising Club, and I know a lot of people and think I can do something for you – would you like to make me an agent for your multihull designs?’

Lock Crowther was one of these designers and so was Arthur Piver; ‘Piver rhymes with Diver’ he used to tell everybody.

The people I approached all said yes. Arthur Piver said he wanted to be the only one represented and I turned him down – within months he was lost at sea.

I worked this business up. I wrote a book called ‘Modern Catamarans’ which would be archaic if you read it today, but went over well at the time – I sold it at $3.00 a pop.

Once these designers like Lock Crowther, Jim Brown, Norman Cross, James Wharram, Hedley Nicol and others were on board, I wrote a book called ’50 Multihulls you can build’ involving all of the designers I was agent for. That sold out for $3.00 a book and was in itself an advertisement for the designers.

I did very well at this and was making a good living simply selling their plans.

Lock would send me a packet of plans, I would sell them, keep my commissions and send the rest back to him along with details of those who had bought them.

Of the multihull designers you represented – what was the greatest difference between their designs?

There was a great difference between some of them. Some were very racy, others were cruiser orientated – Arthur Piver for example concentrated on the number of berths on his boats; we got to calling those designs ‘condo-marans’ and even ‘room-marans’.

Did the Lock Crowther designs stand out?

Yes. They stood out because first of all his designs looked good. He had the knack of making boats look beautiful. Arthur Piver’s could look like boxes – while other’s looked too racy or too way out.

Lock’s cruising boats grew out of racing boats. His first boats were always racers but then he began making cruising boats. He wrote an article which I reprinted to use as a sales brochure which was called ‘A Message to the Cruising Man’. I still have it.

Because I was building boats for myself as well as selling plans people would ask me to make hulls for them. So I rented a small commercial unit and started making boat hulls.

The very first one I made for someone else was a 38 foot Lock Crowther design. We did others and I built my own boats there as well. I remember building a 52 foot James Wharram design catamaran for a movie producer in Toronto. It became very interesting but I got too much into the boat building aspect when my major income was still selling the plans.

In 1964, when I was building my own boats; my own Nugget trimaran, and for my son a 16 foot, Frolic, I learnt that wooden boats in Canada had a life of about six years. This was because of the climate and because most of the sailing there was in fresh water. The primary building material in wood was Douglas Fir in Canada; this is a strong, straight grained wood which is quite heavy and in fresh water rots very quickly. It turns black.

I was trying to find some method of using this lovely wood and overcome the problems of rotting – I was playing about with different coverings, different paints.

When I built my first Lock Crowther boat, which was a Buccaneer 24, I went to a company that made epoxy coatings for steel ships which were being built in Canada.

When I built my first Lock Crowther boat, which was a Buccaneer 24, I went to a company that made epoxy coatings for steel ships which were being built in Canada.

They had an epoxy tar – so I coated the Buccaneer 24 with epoxy tar.

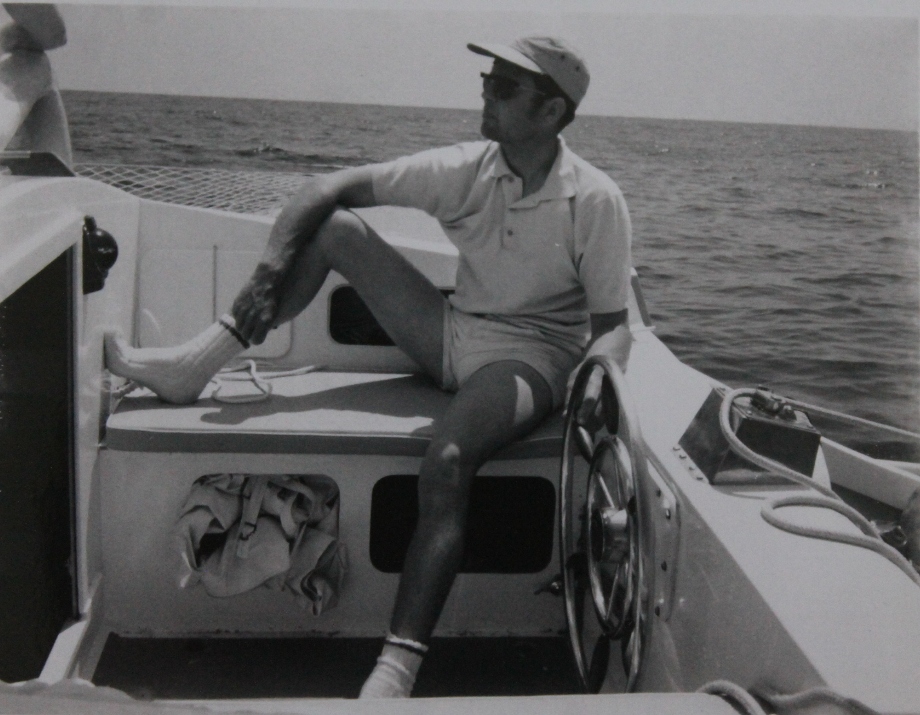

Photo: Pat with his Buccaneer 28

What I had done with my previous wooden boats was just to paint the inside – which was fine above the floorboards but beneath these you had to soak it with Copper Naphthenate which was called Cuprinol; this green stinky stuff which soaks into wood and kills all the fungus spores.

During Winter in Canada you would have to pull all the boats out of the water as it froze and the snow which would build up on the boats would melt, go down into the lower decks and bilge and you would get this black rot occurring. You would have to put a blower heater in the boat and dry it all out in the Spring and then recoat it with the Cuprinol.

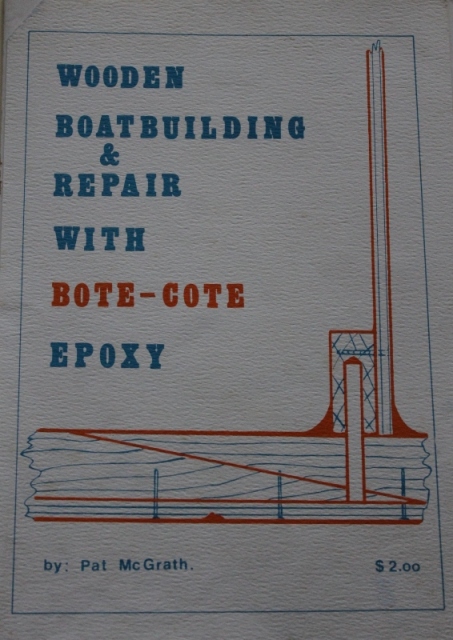

So I developed this business of getting thin epoxy and painting the wood with two or three coats of it to keep the water and water vapour out.

Unbeknownst to me, 200 miles away in America, were the Gougeon Brothers who did the same thing at the same time.

This happens all the time – history is filled with such cases.

They developed a similar system and called it WEST System Epoxy – ‘Wood Epoxy Saturation Technique’.

I couldn’t call mine by a same name, so I called mine ‘BOTE-COTE’ – and built a business where when you’re building a boat you simply encapsulate every part with this epoxy; two coats on the inside and three coats on the outside. The stuff thickened up could be used as glue, thickened further it could be used as a lightweight filler when making fillets.

As a subsidiary of my company I then registered BOTE-COTE Products Limited.

That took off really well.

My first wife died in 1970.

I met Jillian, who was in ballet and a ballet teacher. Jillian had two ballet schools in Melbourne and hired people to run these while she went around the world doing guest teaching in Europe, Mexico, in California America and then she came to Toronto.

We lived in a huge high rise complex called Thorncliffe Park in the middle of which was this beautiful recreation centre; it had a rolling glass canopy which could be opened up during the Summer, it looked down into the Don Valley and a huge grassed area. The recreation centre had a full sized Olympic swimming pool, a dance area, a gym, everything to do with recreation.

Jillian started there teaching ballet to children and quickly ended up being manager of the whole centre, overseeing 32 staff, and that’s when I met her.

She left this position and came working with me as my Administrator. Jillian was more than adept at this but I also have photos of her applying epoxy as well – she worked on building boats as well as anyone else.

Jillian

How did you end up in Australia?

Well, Australians always want to come home, don’t they? They roam the world but always come back to Australia. We moved to Australia in October of 1977, to Melbourne.

The business developed into a conglomerate of companies and we sold the whole thing; it started off as Canadian Multihull Services and ended up as Canadian Aeromarine Services because I added on a couple of aircraft companies as well as this epoxy glue we developed was so good it passed the test for being used in kit airplanes.

We sold the company and sold the rights to BOTE-COTE to a guy in the east coast of America and went to Melbourne. I also sold, at the same time , the rights to be the agent for all the multihull designers. Unfortunately he didn’t do too well and ran this business into the ground. Lock wasn’t happy with this or the change as I’d been his top agent prior to then.

While in Melbourne I registered a new business as BOTE-COTE Products and began doing the same boat building there. This went down very well.

I had a dealer in Melbourne who had a marine woods company and he did very well selling this product. While doing this I came down with pleurisy. The doctor said to Jillian ‘you’ve got to get him out of here’ and so we decided to move to Sydney. The company putting up the BOTE-COTE epoxy bought me out.

I had a dealer in Melbourne who had a marine woods company and he did very well selling this product. While doing this I came down with pleurisy. The doctor said to Jillian ‘you’ve got to get him out of here’ and so we decided to move to Sydney. The company putting up the BOTE-COTE epoxy bought me out.

Very shortly after this they were absorbed into a larger business through a hostile takeover and this company had no interest in the epoxy. The guy who had had an interest as my agent in Melbourne bought the rights to BOTE-COTE for a thousand dollars!

He linked up with another chap in Melbourne, a Chemical Engineer, they developed BOTE-COTE futher and it is still being sold as we speak by a company called Boat Craft Pacific, in Queensland, and still doing very well.

It would have been revolutionary?

Yes; my neighbour here has a 34 foot boat and explained to me recently about this wonderful epoxy he uses, which you can wash in water and spoke more about it. I said, ‘you must be talking of BOTE-COTE epoxy’, to which he answered; ‘how did you know?’ …’because I developed BOTE-COTE epoxy’ – he looked at me with absolute blank disbelief.

Where did you move to in Sydney?

We came up and stayed for a couple of weeks with Lock Crowther in Allambie heights. Jillian, who is very good at this, earmarked an apartment in Manly facing directly up the harbour.

Jillian started work for Blackmore’s in a position where she only answered to Marcus Blackmore – she initiated their magazine and all sorts of stuff. While living in this apartment we had our two children, a boy and a girl.

I got into windsurfing. Knowing a lot about epoxies and adhesives and the tricks if the trade I found that the Windsurfer, which was built right here by Sailboards Australia, had a problem near the centreboard which resulted in the centreboard case splitting and resulted in water getting into the hull. I was told you couldn’t repair this due to the cross linking polyethylene it’s made of is not able to be glued.

I thought it could be repaired and so started a company called Brookvale Sailboard Repairs and hung a sign out in a little commercial shop. I placed an ad stating “Splits in your Sailboard? We fix them - $25.00”.

I would do six sailboards a day and this little business did very well.

When I told my cheeky number two son Nigel I was making $600 a week he answered ‘you can do better than that’ – he had just become a multi-millionaire himself by developing a computerised set up which would dispense with car manufacturers needing to make moulded mock ups of proposed new cars. He was a computer whizz. It took them seven years to develop this fantastic CGI which would do away with people having to make physical models.

Fantastic!

Yes, he’s amazing. They do a lot of the special effects you see in many current popular TV programs.

Getting back to Lock – what was he like as a man?

He was a real good Australian bloke. He was a good bloke and he had a lovely attitude, he didn’t annoy anybody. He knew what he was doing, he was very well educated – as taking a degree in Aeronautical Engineering but realised there was no real future in this area so switched to Electrical Engineering and did very well in that but found himself moving into boat design. He designed his own boat for his own reasons and really loved what he was doing, found he was designing boats that won races and so became a multihull designer.

He had what it takes – he had that talent.

I was very happy to find him and when I wrote to him and asked if I could represent him and began selling his boats like nobody’s business, he eventually decided I could be his exclusive agent in both America and Canada.

Were his designs popular?

Yes – because of two things; when I wrote books like ‘50 Multihulls You Can Build’ those names in that book became known. We also had some ins with the people in the business and I wrote articles on these as well.

Because I was involved in representing Lock Crowther, and while we were still living in Melbourne one of Lock Crowther’s clients was building a beautiful new sea-going racing boat which Lock designed specifically for him. This man wanted somebody to run the building of the boat and employed an overseer or foreman and they hired me as a construction consultant, and this too was a hands on position.

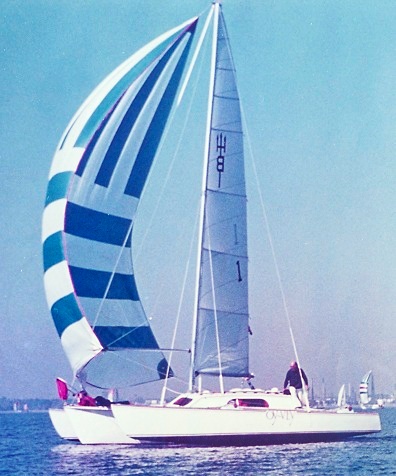

There were several very innovative elements involved in this boat such as bow bulbs, stern bustles and particular hull sections for this boat, that was named Bagatelle – I still have a hard hat that says ‘Construction Consultant – Bagatelle’. That was a marvellous boat – Bagatelle.

Which was your favourite out of all the Lock Crowther boat designs?

The Kraken 40. I sold Kraken 40 # I to a guy called David Green in Toronto. When I had my own boats Dave Green also got into building boats. I had an Arthur Piver Nugget and he built an Arthur Piver 40 foot Victress called ‘Zing’ - these were fairly agricultural boats compared to the stuff Lock Crowther came up with. He then built a Jim Brown boat in which he sailed around the Bahamas.

Jim Brown boats have a middle cockpit with accomodations fore and aft – very nice boats, but if you’re out in rough weather centre cockpit hull boats are bad, as all the sea spray comes into the cockpit.

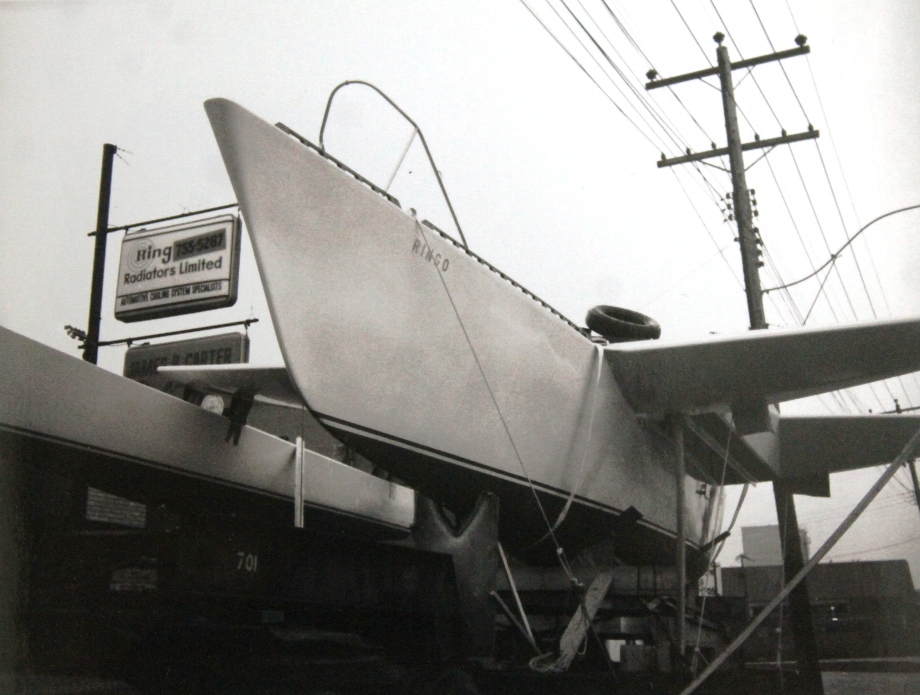

I sold him a set of Kraken 40 plans and he built this boat very quickly for the Inaugural Multihull New York to Bermuda Race. I helped him build this first Kraken 40, he sailed it down to New York and we drove down to the Miramar Yacht Club to board this boat where I met this guy who was the originator of the trimaran – Victor Tchetchet, a little Russian man. He coined the name ‘trimaran’ – built the first modern trimarans seen in North America in 1945. Arthur Piver took this on, kept calling them ‘trimarans’ and that’s how that name became part of our language. Victor had tears in his eyes as he looked at "Ringo", "I have lived to see this " he said. He died a while later.

Dave Green sailed this first Kraken 40 in the first New York to Bermuda Multihull race and it cleaned the clocks, setting a multihull record despite us being becalmed for one whole day; If you ever think about going into the Bermuda Triangle, think again, and don’t.

He called his Kraken, "RINGO" because he had this company called 'Ring Radiators' –and Ringo was the first Lock Crowther Kraken 40 to be built. So Lock gave it sail No. 1.

I liked it because it was a new design, because it was beautiful. It was a beautiful boat; you looked at it and it looked like an aeroplane, a lovely boat altogether. There’s another story there but we’ll talk about that another time.

Photo: Dave Green in cockpit of Kraken 40 Ringo – photo taken in St. George’s Harbour in Bermuda

Pat: this photo illustrates what is absolutely typical of this beautiful boat the Kraken 40 – see how it looks alike an aeroplane

I can see why you went from aeroplanes to Multihulls

Yes there’s a lot of similarities – the early designs for trimarans and catamarans used exactly the same techniques that De Havilland used in their designs that won all the races from Britain to Australia in the 1930's.

All these people building their own boats – nowadays people go and buy a boat already built …

Well, there was a time when to get a multihull, if you wanted one, you had to do it yourself. A lot of people who did it for themselves then turned into building them for others – some they built weren’t that crash hot. On the other hand the best designers would design boats that you and I could build and they were great boats, and Lock Crowther was one of these few.

I ended up with six designers world wide that were what I considered were of a standard where I could sell their plans honestly and say ‘these are good and you can do it’.

You seemed to be enjoying yourself at the most recent Lock Crowther Multihull Regatta here on Pittwater – you still enjoy sailing?

I love sailing – you can’t keep me off the water, even if I’m getting a bit doddery nowadays.

Back in Brookvale..?

So I set up Brookvale Sailboard Repairs and was then approached by a guy from Alfa Romeo who wanted to do a promotion where they wanted all of their dealers to have an Alfa Romeo sailboard. I knew a guy who made sailboard sails – we designed a sail with red and white stripes that had an Alfa Romeo brand logo on it – I also knew some people who imported a Swedish sailboard, from whom I could buy the board.

I asked the man how many he wanted – he said they had 150 dealers and ‘I want everyone to have one of these sailboards’ and further, he wanted everyone who bought one of the Alfa Romeos to also get one of these sailboards.

So I organised all this and made so much money that I was able to forget about sailboard repairs and open my own sailboard shop, called The Sailboard Shop, at Cremorne.

This business was doing quite well when I suddenly got a letter from somebody in Newcastle stating I couldn’t’ call the business The Sailboard Shop because " we’re The Sailboard Shop and have that name registered as a Pty. Ltd name."

I went back to the Business Registry Office and explained their mistake – they were very good about it all and reimbursed me the costs incurred through changing signage, letterhead , business cards, etc.

I changed the name to "The Windsurfing Shop "– and then thought I’d have problems with the chap who owned Sailboards Australia, as I knew he was a protective guy.

Just then, and out of the blue, the lawsuit denying the patent on ‘windsurfer’ occurred and no one could stop me calling it "The Windsurfer Shop"

Around this time there was" Sydney Sailboards" at The Spit as well. David Bray, who is a very smart business man, came to me and explained that I was hurting their business and offered to buy me out. I had been looking at the sailboard business in Europe and saw interest was declining; it was fad over there, and was fading in America too – I reasoned it was only a matter of time before that occurred here. So I sold to David and he ended up opening "Sydney Sailboat Centre" in Mona Vale in 1985 on the corner where the Commonwealth Bank was, installed me as manager, and paid me very well.

This business flourished for a while and some people are still Windsurfing today. The sailboat part of the business was managed by Curly Colette who up until quite recently was on the corner of Bassett street.

When I worked at Sydney Sailboats Centre at the Spit, I met a girl who taught sailing and windsurfing, Holly. – she was a cracking good girl, very smart, and the daughter of Lowell North of North Sails, a very well known award winning sailor, an entrepreneur who has sailed all over the world. Holly North taught me how to windsurf. While working in Mona Vale I hooked up with a company that was putting out a magazine called Sea Spray – for whom I wrote articles. When I met this wonderful girl, Holly North, we would do sailboat tests which they then printed in this magazine.

Holly finally went back to America and to finish a degree in Agriculture, came back to Australia and is now working for the Parks and Wildlife Service in Byron Bay. She is now a Ranger and flies a helicopter around the place keeping an eye on the animals and parks.

The articles and sailing with Holly caused me to really want to build and have my own boat again but with a young family and work it didn’t eventuate.

I was sailing with Bill Salisbury on his big 45 foot catamaran Pennant along with David Bishop and his beautiful wife Jenny. From sailing on Pennant I got to sail with Logan Apperly, who had a Kraken 40 called "Mana Moana" – he built this boat and then he, with Lock Crowther as crew, sailed it from Sydney to New Zealand and set a record for Sydney-Auckland.

I sailed with Logan as his navigator on Mana Moana. We did lots of racing and sailing around Sydney until Apperly had a misfortune in the Manly end of Sydney Harbour. Apperly had a guest who was a monohull sailor, who was on the tiller when Logan went below for some reason. A big gust came down from the North Head, whacked into the sails, and being a monohull sailor he did what a monohull sailor would correctly do and heaved on the tiller to allow the boat to heel and lose the wind.

You don’t do this on a multihull though – you feather right up into the wind, or blatantly pull off downwind.

In heaving on the tiller, the boat heeled, but being a multihull it depressed its float right under. The Kraken 40 was one of few boats that had submersible outriggers, which they don’t do anymore. The tip of the outrigger was down about ten feet below the surface of the water and the bow of the hull imploded. The boat continued to cartwheel and turned completely upside down and capsized.

As it was in Manly Harbour the Police boat came along and towed bow over stern and righted it again. Logan was so put off by this that he sold it – and it was also bad press for multihulls at the time.

After sailing with Dave Bishop I raced with a guy called Geoff Jacks on board his boat Trojan – he had a company called Trojan Electric Motors – and this was one of the three fastest boats on Pittwater. That was exhilarating sailing. There’s another of these fast boats that was still racing on Pittwater until recently called Zorro 2.

I remember one sail on Trojan where we hard on the wind, the sails as flat as sheets of steel and sailing along in a crowd of monohulls, going through them like a knife through butter, at a solid 15 knots.

How long have you been living in Mona Vale?

We were living in Manly. We had a business in Manly too – The Organising Group – which was a conference organising business that Jillian asked me to come into and computerise. This was around the time the sailboards were not so popular so I left the selling of these and went into The Organising Group.

Jillian wanted to move to a house with a garden for the children as living a second floor apartment wasn’t good for two young children. We bought our very first house in North Narrabeen in 1985 prior to my joining The Organising Group.

We sold The Organising Group in 1996 and Jillian had two years off. After this, and with her love of houses, administrative ability and being good with people, she decided to go into Real Estate and sell houses. Jillian was so good at this that she caught the eye of John McGrath and joined their Mosman office.

After doing well in this office she approached John McGrath about opening offices in Manly and further along the Northern Beaches, which he gave her his backing for and she excelled in opening up the Northern Beaches to McGrath Real Estate offices.

We were in Manly for six years, North Narrabeen for five and a half years and then we moved to Church Point, right behind the BYRA clubhouse. We looked directly down onto the RMYC start line – every Saturday morning until recently I would be there, in the bathroom, with my binoculars, watching the start line, watching all the boats.

I used to race on David Bishop’s boat, the Mighty Manfred, which was a Crowther 10 metre stretched to 35 feet – a beautiful cruising boat. Dave Bishop was a very laid back sailor – he wanted to cruise, and now has bought himself a big cruising boat in Qld..

When Jillian retired we fulfilled one of Jillian’s dreams, to have a lovely home with a picket fence and moved to the Blue Mountains. We sold 15 Corniche Road and bought a

beautiful house in Katoomba with a huge garden with a lemon tree, rows of pear trees, a big lawn, pool, two fountains – nice high box hedges all around.

It was marvellous, except, it was no where near the water – I couldn’t sail, couldn’t exercise my hobby of flying radio controlled model aeroplanes, too many trees.

Then the bushfires of October 2013 came. They were really bad there – the fire Chief of the area told us to get out.

We put the house up for sale, packed our bags, and left. We came back down here, to my daughter and son-in-law’s home at Palm Beach. While staying there the house sold – we never went back. Jillian found this place and we bought it.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater?

Anywhere on Pittwater. – it’s all beautiful. Where we lived at Church Point for 20 years was just beautiful. On a clear day I could see the gallery around the top of Barrenjoey lighthouse.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

When I wake up in the morning I look out of the window and look at the water, and I look at the sky, and I look at the trees and their leaves, and I say ‘Thank You Lord for another day’.

Pat's Buccaneer and Oy-vey

References – Extras:

Outrigger pioneers: http://outrig.org/pioneers_jb.

html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thorncliffe_

Park Lowell Orton North (born December 2, 1929) is an American sailor and Olympic Gold Medalist. He competed at the1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, where he received a gold medal in the star class with the boat North Star, together with Peter Barrett. In 1957, he founded North Sails in San Diego, a world wide company producing sailing equipment. He received a bronze medal in the dragon class at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. North participated in 1977 America's Cup defender series where he skipped the 12 metre yacht Enterprise. More at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lowell_North

Wooden Boatbuilding & Repair with Bote-cote Epoxy - Authors Canadian Multihull Services, Pat McGrath, Edition 8. Publisher Canadian Multihull Services, 1977. Length 16 pages

Nottingham High School is an independent fee-paying day school for boys in Nottingham, England, comprising the Infant and Junior School (for ages 4–11) and Senior School (for ages 11–18). Nottingham High School has 987 pupils, including approximately 717 in the Senior School (about 123 in each of years 7–11 and around 51 in each of the two years of the Sixth Form). Located on Waverley Mount,[3] the school's main building is close to local amenities and public transport. The main building is in the style of Gothic Revival architecture; other buildings include: the Founder Hall building (in which the school's swimming pool and drama studios are situated); the Sir Harry Djanogly Art and Design Technology building; the Lady Carol Djanogly Music School; the Sports Hall; the Simon Djanogly Science building; the Old Gymnasium; and thePlayer Hall. The Junior School has its own buildings on the same campus. The playing fields are some 3 miles (4.8 km) from the school and are located at Valley Road.

In 1513, the school was founded as the "Free School" by Dame Agnes Mellors, after the death of her husband, Richard, partly in his memory, but also as an act of atonement for his several wrongdoings against the people of Nottingham. In order to do this she enlisted the help of Sir Thomas Lovell, who was both the Governor of Nottingham Castle and Secretary to the Treasury. As a result of their combined efforts, King Henry VIII sealed the school's foundation deed on the 22 November of that year. It is not clear whether this was a new institution or a refoundation or endowment of an existing school, of which records exist as far back as 1289.[5] 19,940 boys are estimated to have attended the school since 1513. Nottingham High School. (2014, October 16). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Nottingham_High_School&oldid=629851427

RAF Halton: http://www.raf.mod.uk/rafhalton/

The Royal Air Force College (RAFC) is the Royal Air Force training and education academy which provides initial training to all RAF personnel who are preparing to be commissioned officers. : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Air_Force_College_Cranwell

RAF Cottesmore: Royal Air Force Station Cottesmore or more simply RAF Cottesmore is a former Royal Air Force station in Rutland, England, situated between Cottesmore and Market Overton. The station housed all the operational Harrier GR9squadrons in the Royal Air Force, and No. 122 Expeditionary Air Wing. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RAF_Cottesmore

RAF Kinloss: Kinloss Barracks is a former Royal Air Force station (RAF Kinloss), located near the village of Kinloss, on the Moray Firth in the north of Scotland 19 (C)OTU was split into 236 Operational Conversion Unit (OCU) and the School of Maritime Reconnaissance in 1947 with 236 remaining at Kinloss. A further change in 1956 saw the units recombine as the Maritime Operational Training Unit (MOTU), which remained at Kinloss until 1965. In July 1962, the station received one of its highest honours, the Civic Freedom of the Royal and Ancient Burgh ofForres, allowing Kinloss personnel the right to march through the burgh with swords drawn. This was the first time any military unit had been so honoured by Forres throughout the burgh's 1400 year history. During the Cold War Kinloss squadrons carried out anti-submarine duties, locating and shadowing Russian naval units.: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RAF_Kinloss

Avro Canada: In August 1957, the Diefenbaker government signed the NORAD (North American Air Defense) Agreement with the United States, making Canada a partner with American command and control. The USAF was in the process of completely automating their air defence system with the SAGE project, and offered Canada the opportunity to share this sensitive information for the air defence of North America. One aspect of the SAGE system was the Bomarc nuclear-tipped anti-aircraft missile. This led to studies on basing Bomarcs in Canada in order to push the line further north, even though the deployment was found to be extremely costly.

The introduction of SAGE in Canada will cost in the neighbourhood of $107 million. Further improvements are required in the radar... NORAD has also recommended the introduction of the Bomarc missile... will be a further commitment of $164 million... All these commitments coming at this particular time... will tend to increase our defence budget by as much as 25 to 30%. — George Pearkes, then-Minister of National Defence, 1958

Defence against ballistic missiles was also becoming a priority. The existence of Sputnik had also raised the spectre of attack from space, and, as the year progressed, word of a "missile gap" began spreading. An American brief of the meeting with Pearkes records that Pearkes "stated that the problem of developing a defence against missiles while at the same time completing and rounding out defence measures against manned bombers posed a serious problem for Canada from the point of view of expense".[67] It is also said Canada could afford the Arrow or Bomarc/SAGE, but not both.

By 11 August 1958, Pearkes requested cancellation of the Arrow, but the Cabinet Defence Committee (CDC) refused. Pearkes tabled it again in September, and recommended installation of the Bomarc missile system. The latter was accepted but, again, the CDC refused to cancel the entire Arrow program. The CDC wanted to wait until a major review in 31 March 1959. They did, however, cancel the Sparrow/Astra system in September 1958.[69] Efforts to continue the program through cost-sharing with other countries were then explored.

We did not cancel the CF-105 because there was no bomber threat, but because there was a lesser threat and we got the Bomarc in lieu of more airplanes to look after this. — George Pearkes, then-Minister of National Defence, 1959

Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow. (2014, September 18). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved fromhttp://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Avro_Canada_CF-105_Arrow&oldid=626019579

Ortho Pharmaceutical was initially formed in the United States in 1931 as a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson to market the first prescription spermicidal contraceptive jelly, Ortho-Gynol. In 1963, Ortho introduced the second oral contraceptive available in the United States (Ortho-Novum 10 and Ortho-Novum 2, produced by Syntex). Ortho Pharmaceutical. (2013, February 21). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ortho_Pharmaceutical&oldid=539370472

Copper Naphthenate has been used as a wood preservative for over one hundred years with many applications for use, including field boxes, benches, flats, fence posts, water tanks, canvas, burlap, ropes, nets, greenhouses, utility poles, crossarms, and wooden structures in ground contact and above ground contact.