April 28 - May 4, 2013: Issue 108

Philip Bond

Philip Bond is the latest author to be published in Pittwater. Three books, Short Stories for Long Journeys, Between Gin and Tonics and After the Brandy are already available as e-books here and a fourth, Fasten Your Seatbelt is a current work in progress. All of the short stories in these E Books are taken from his extremely colourful and exotically eccentric lifetime of travel, adventure, and of growing, across six continents.

Mr Bond is not just an accomplished wordsmith though, a founding member of the Woody Point Yacht Club, the gentleman who came up with the idea of having an annual Marine Art Show to coincide with RMYC’s annual Timber Boat Show, an illustrious career in film and television, a man who has leant on both sides of pub bars are just some markers of a life filled with initiating and fulfilling inspirations. This week we share a small insight into another Pittwater ‘travelling under the radar’ stalwart…Mr Philip Bond.

When and where were you born?

I was born in

Hammersmith in London in 1931; not because my parents lived there but because we

were going to watch the Oxford and Cambridge boat race and my mother got taken

short and was rushed into Hammersmith Hospital.

I was born in

Hammersmith in London in 1931; not because my parents lived there but because we

were going to watch the Oxford and Cambridge boat race and my mother got taken

short and was rushed into Hammersmith Hospital.

Where did you grow up?

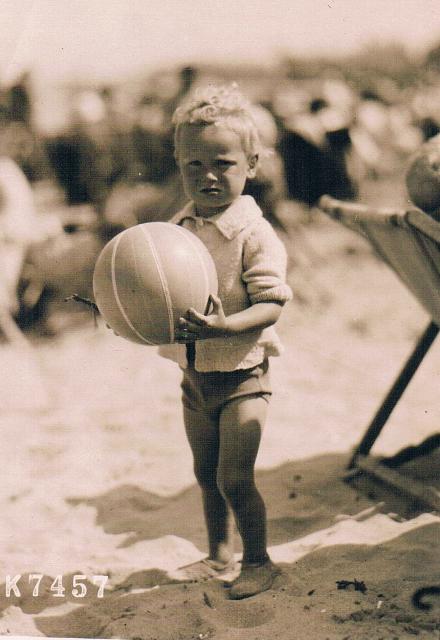

Well, the first years I don’t remember of course but father, when I was about aged three I was in Gibraltar, was posted to Gibraltar. My father was a Captain in the Army. I can actually claim to have been among the gunfire in four wars; we were shelled by the Spanish at some point from Algeciras, my nanny (Maria) took me up onto the roof, and said “look, fireworks!”; but in fact they were shelling Gibraltar so I was quickly rushed down again. (laughing).

I do remember something else that was dramatic which was they torpedoed a German Battleship; I don’t know whether it was the Scharnhorst or one of those, and it was pulled into Gibraltar harbour, this is before WWII, and it was a fair sized boat. The British naval Dockyards repaired it for them! My father had to put up all the German officers and crew, billet them around the place, and we had two; a Ober lieutenant and also another ranked one. I remember him teaching the cook to goosestep around the garden; I can remember that.

We bailed out of there just before WWII and he got posted to Norway. My first memory of that was when, I was staying with my grandmother in Portsmouth, and there would be a knock on the door and I would go and answer it and there I was standing looking at a German Swastika on a helmet and there was my dad’s face at the top of it; he apparently was on the last destroyer to escape from the Narvic Fjord in Norway and while waiting to be transported he’d put on some fatigues and while waiting to be loaded he’d rushed behind a warehouse because he needed to go to the bathroom and when he returned where all his luggage, where he had been standing, was a big hole; it had all been blown up by a bomb; so all he’d got was what he was standing up in and a German helmet. That’s what he arrived in at 57 Chetwynd Road, Portsmouth.

What was your father’s role in the Army?

He finished up as a Major-General. He was head of what was then called the Royal Army Service Corp which was transport and actually makes up one fifth of the whole British Army, or had at one time.

Needless to say, I followed in father’s footsteps and went to Sandhurst.

I went to St Paul’s school, which was in

London, and became Montgomery’s headquarters, and we were evacuated out into the

countryside near Wellington College and then back to London after the war, St.

Paul’s was arguably the oldest school in England, it was formed by Dean Colet in

the courtyard of St Paul’s Cathedral.

(St Paul's School is a

boys' independent school, founded in 1509 by John Colet, located on a 42-acre

(170,000 m2) site in the London suburb of Barnes.)

You were supposed to get a really good education here and I suppose I did having passed the exams into Sandhurst. At Sandhurst I became a Second Lieutenant and was posted to Germany, found it all very regimental and boring so volunteered to go to Korea.

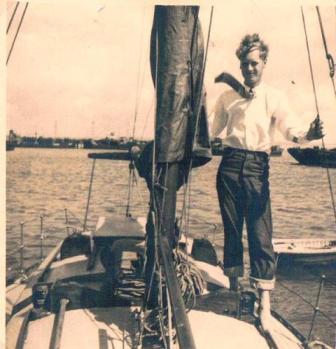

So I then went to Korea and found myself actually based in Japan at Head Quarters British Commonwealth Forces Korea (. I was in an Australian camp in Kure; I was in charge of the Cold Storage Depot; but I did do all sorts of things with the boys; I ran the sailing; we had VJ yachts from Australia and I think we had 16 of them.

Was this the first time you encountered Australians; in Japan?

Yes, I

suppose it was.

Yes, I

suppose it was.

What was your first

impression of them?

What was your first

impression of them?

Well, I had to make an impression by pretending to be Australian. I started freelancing with the local radio station and saying things like “This is the Australian Forces Network broadcasting pushing it out to you on the twin booms of Radio Kure.” So I was pretending to be an Australian and I had to get it( get the accent right).

You had 16 VJ’s there; how did that come about?

They came down with what was called the ‘Amenities Unit’. So having done quite a bit of sailing before that I was put in charge of running and teaching people on R&R from Korea to sail. I also heard about a boat that had sunk, a Halverson yacht. The American seaplane unit at Iwakuni had pulled it off the bottom and were trying to get rid of it and asked would I put it on our noticeboard with a price on it and see whether they got any offers. Well I didn’t put it on the noticeboard at all, I made the only bid as it happened because we wanted it and so I got myself a beautiful Halverson yacht and spent quite a bit of time on that.

Then I formed a band out of the guys at the camp; ‘The Fabulous All Star Kure City Jazz Band of Stage and Radio fame’ and I heard much later, when Graham Bell visited the troops in Japan and Korea, that he heard about this mysterious Jazz Band that had a yacht before he arrived and wanted to know who we were.

What year was this?

1950. I then went to Malaya (what was called the Malay Emergency) and fought in the jungle, which was a little bit hairy, in fact very hairy, and everyone has a story of their own about these experiences; but I resigned my commission because I was shot at one day, quite furiously shot at by a guy that we did intend to kill, and we both missed, and I thought to myself ‘This is the silliest game I’ve ever played.’ So I resigned my commission. I had a bit of trouble getting out because dad was a General.

You spoke about sailing in Japan and that you’d had a fair amount of experience at this by then; when did you first start sailing?

I’d always learnt to sail, right from Gibraltar days I was racing, my father taught me to race. In the brief period I was in Germany I sailed too, because I was always in demand as crew, but I was always the junior member of the crew. I remember sailing on one race, the Kiel Copenhagen race, and we won it; it was a cold night, I hadn’t been dry for three days and I was freezing cold. They were all celebrating obviously down below, I’m on the helm, it was about four in the morning, and I saw Kiel Tower coming out of the mist. And I looked at that tower and said to myself “I’m never going to do that again.” And I never went sailing again really, apart from the Japanese bit, until I got to Australia in 1976.

You have a long practised creative streak. Where did that start from?

My father was one of the many Army Generals who

did art or were artists, and my mother was a portrait painter. I didn’t really

take up painting until I came to Australia and I decided to join an art class.

Then at the Royal Motor Yacht Club, I’d been a member since arriving in

Australia, and also a founder member of the Timber Boat Division, and we had a

Timber Boat Show. I can remember having a committee meeting where we were saying

‘we’ve got to do more then just this boat show, we need a few side shows.’ I

said, ‘well why don’t we have a Marine Art Show, we’ll just put up a tent in the

car park and have a dozen or so paintings which people can put in.’

Well,

that, even then, developed way beyond its intentions. It is now the largest

Marine Art Show in Australia. It’s held every year now of course, and will be

the ninth annual show this June.

You have also done a bit of film directing haven’t you?

My word I have. That was all in between leaving the Army and then being here. When I finally got out of the Army my father didn’t want to know me so I had to get a job. So I got a job, after all that broadcasting experience, with the BBC in Bristol, but I couldn’t take the job as it wasn’t vacant until six months later. I heard about a friend of mine who had just been fired by Pearl and Dean the advertising and film people and so I went and applied and somehow managed to get the job as trainee script writer, I would have been 25 by then. Trainee didn’t come into it; I was thrown in at the deep end and found myself writing for a director called Kenny Hume who was gay as all get out which didn’t bother anyone in particular apart from the girl he married – Shirley Bassey.

I clearly remember

when we were in the editing room and it was about six or seven o’clock in the

morning and we were putting something together with a very dour editor called

Alan something or other and somebody rushed in and said, “Hey, Kenny Hugh is

getting married. “ and we all said, “Married? You’ve got to be kidding. Who is

he getting married to?” to which the answer was, “You know, that coloured

singer..what’s her name ?” and Alan looked up and said “Paul

Robeson?”

I clearly remember

when we were in the editing room and it was about six or seven o’clock in the

morning and we were putting something together with a very dour editor called

Alan something or other and somebody rushed in and said, “Hey, Kenny Hugh is

getting married. “ and we all said, “Married? You’ve got to be kidding. Who is

he getting married to?” to which the answer was, “You know, that coloured

singer..what’s her name ?” and Alan looked up and said “Paul

Robeson?”

(Laughing)

So he married Shirley Bassey,

which didn’t work out in any shape and form. I can remember them arguing in the

office time and time again.

That’s by the by; what happened was, the

managing director, Byron Lloyd, said to me “look, your scripts are too hard to

direct.” And I said “well, that’s not possible….” And “has it occurred to you

that this particular director doesn’t want to go down to Bristol for the weekend

( I think we were filming on the Britannia then); I’d written the script for

that, Ovaltine, Sir Harry Haig, and he gave me free reign Harry Haig, which was

great; so I said, if they won’t direct it, let me direct it; and he said ‘that’s

a good idea’; so I went down and did it and about six months later I wrote and

directed a TV commercial which won the Cannes Lion at the Cannes Film

Festival.

Which was this?

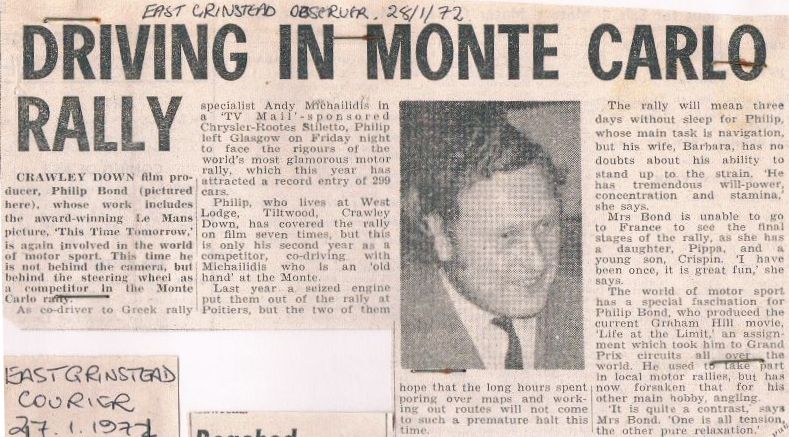

It was for a newspaper; the Evening Standard. This was the first Cannes Lion England had won. From that moment on I was away, I couldn’t do anything wrong.

Inspired by the International Film Festival, which had been staged in Cannes since the late 1940s, a group of worldwide cinema screen advertising contractors (SAWA) felt that the makers of advertising films should receive similar recognition as their colleagues in the feature film industry. In order to promote the cinema medium, SAWA established the International Advertising Film Festival. The first Festival took place in Venice in September 1954 with 187 film entries from 14 countries competing. The Lion of Piazza San Marcos in Venice was the inspiration for the Lion trophy. The second Festival was held in Monte Carlo and then in Cannes in 1956. After that, the Festival took place alternately between Venice and Cannes. The films in the competition were split into two categories: TV and Cinema. They were judged according to technical craft. There were, for example, categories for commercials of different lengths, live action and animation. More.

Did you stay in the commercials world?

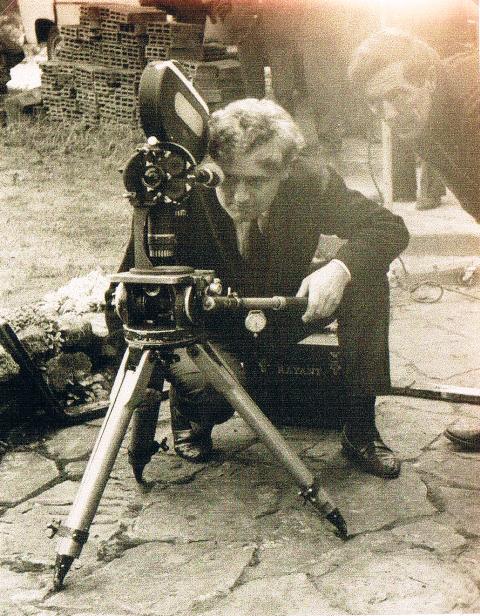

I then left Pearl and Dean and joined a television company called Rayant which was an ongoing documentary film making company and wanted to start commercials divisions which I was to start. I didn’t get on with that too well because I discovered I was on a profit-sharing basis as this was one of five companies owned by the London Breweries trust and the object of this particular company was to lose money. So then I formed Philip Bond Productions.

What was the first film that came of Philip Bond Productions?

Well actually it was a very good one which paid for everything; it was a series for Vauxhall cars which was to be shot in Spain. We shot it in Spain, which had its dramas, every film had its dramas. I then went on to do, and probably hold the world record, over two and a half thousand television and cinema commercials. We were doing four a day at one stage.

That’s a phenomenal amount Philip.

Yes, it was hard work; we’d do four a day; they were those cinema trailer things, they were easy to write and get done.

Trilby; he’s done a phenomenal amount of things; he’s only up to when he’s about 35 years (where has told to) and he’s 82 now.

Philip:

so we formed Philip Bond Productions; I

desperately needed a good producer because the company was me; I was writing and

directing, and I needed someone to sell me; I’m no good at selling myself, I

don’t think anybody is.; you can’t say ‘Look, I’m terrific.’ So I needed

somebody else and I got a guy called Patrick Cahill and we became Philip Bond

and Partners then. That didn’t last all that long because he married an Italian

girl who’s father was the boss of Rome or something. We formed a company in Rome

which was called ‘Chelsea Films’. In the meantime I opened branches of Philip

Bond and Partners in Kingston, Jamaica, in Paris, in Johannesburg; we went

worldwide. We were in the top ten of English Production houses at that stage. We

didn’t realise what life was, we were having a ball but working non stop.

Philip:

so we formed Philip Bond Productions; I

desperately needed a good producer because the company was me; I was writing and

directing, and I needed someone to sell me; I’m no good at selling myself, I

don’t think anybody is.; you can’t say ‘Look, I’m terrific.’ So I needed

somebody else and I got a guy called Patrick Cahill and we became Philip Bond

and Partners then. That didn’t last all that long because he married an Italian

girl who’s father was the boss of Rome or something. We formed a company in Rome

which was called ‘Chelsea Films’. In the meantime I opened branches of Philip

Bond and Partners in Kingston, Jamaica, in Paris, in Johannesburg; we went

worldwide. We were in the top ten of English Production houses at that stage. We

didn’t realise what life was, we were having a ball but working non stop.

I

mean it was really stressful I have to say; it was really very stressful, but I

found a way of defeating stress.

What was that?

By cooking. I would come back from a day at the studio or wherever we had been on location and I’d cook a meal and unwind gently.

What sort of meals were you cooking?

Well, I’d throw it away, I didn’t eat it. It was just the process of unwinding.

Trilby; he still does all our cooking.

Trilby; he still does all our cooking.

Is he a good cook?

Trilby: yes, he’s a fabulous cook.

Philip Bond Productions; where did that lead you to; what came next?

I then took on some partners, probably in the late ‘70’s, and we didn’t agree, even on things like what colour the wallpaper should be; it was that silly. At that time Terry Ohlsson, who had been a client of mine through a London advertising agency, had come back to Sydney, because he was Australian, and had formed a company called ‘Kingcroft Productions’. Terry came to me and said “I’m looking for a trendy director.” I said, what do you mean ‘trendy’?’ and he said, “well, it’s trendy in Australia to have a cockney film director who wears blue jeans in is probably about 22 years old.” ..and I was forty something by then.

So I arranged all these interviews for him and he came and interviewed these guys and I never heard anymore. I had to find out what was going on because those who had been interviewed were ringing me up everyday saying “what’s going on? Have you heard” kind of thing. So I rang Terry and asked him what’s going on and he said “I didn’t really like any of them. What are you doing?” and I said, well I’m not doing anything much but I’m not 22years old and I don’t have a cockney accent. My then marriage had just broken up and the company was falling apart so I said; I’m out of here, I’ll come and join you.

And that’s how you ended up in Australia?

I ended up in Australia doing effectively one documentary but that documentary won awards in Australia. It was for the OTC as it was then and it was about laying the cables and it then went on to all the other stations all over the world. The point was I knew how to do it; I’d had all these other companies in different countries and knew how to co-ordinate that kind of thing, what is required. Also, when working in England, I had to be part of the English union, so when we had to film in the UK I would get the job because I could actually work there; the other Australians weren’t allowed to. Over the course of my career I wrote 74 documentaries.

When did you meet Trilby?

I met Trilby on about my third visit to an advertising agency

Trilby: Terry sent him in to an advertising agency; I’d never worked in advertising and I’d been there about five months, working for a Creative Director of Conan and Bell it was called, and the first job that Terry gave to him was to meet people and tell them about a documentary Terry had just made for the Army, ‘The Green Machine’, and it was about these particular tanks and there was no talking it was all set to this classical music the 1813 Overture by Tchaikovsky; you know that incredible one with the guns going off to punctuate the crescendo

The Green Machine a look at the early 1970's in the Australian Army. Video was used to recruit, shows snippets of an exercise Iron Man with 8/9 Bn Youtube at: http://youtu.be/mgfFbTV6u0c

Trilby; in those days there some short films that got shown before you saw the main movie or feature film, so Philip came into our agency. Advertising agencies in those days had a bit of fun and Friday’s you stopped about four or four thirty in the afternoon and went into the boardroom and started drinking yourselves silly, and there would be an excuse like ‘Philip Bond is coming in today to show us something…’ So I was given the job, as secretary of the Creative Director, of looking after him; so I did.

And he asked you out?

Trilby; no, I think I asked him out. I’d never ever asked anyone out…ever ever… but when I met Philip, the sort of person that he was, such a gentleman that he was and is, I knew he wouldn’t ask me out, he’d just arrived here in Australia, and I thought ‘this is a really nice man’.

So this is about 1977, ’78 now?

Philip; yes, ’77.

Where were you living when you first moved to Australia?

I lived with Terry at Manly on the beach to start with. He had this house that was always full of air hostesses from TAA; these girls would drop in, stay the night, and fly off again. One of them Marie said one day, because Terry was getting quite interested in one of them, and they are now happily married, but Marie said; “it’s getting a bit crowded around here. Do you think you and is should go and set up house together and get out of here?” I thought to myself; ‘goodness, this is this blonde 21 year old..’ but share a house as flatmates is what she meant! So we ended up in Fairlight which was very nice but not for that long.

Around then I had heard about a timber boat that was for sale on Pittwater and I needed a slightly bigger boat for on the Harbour so Trilby and I came down here to have a look at it.

Trilby: which was through George, Tanya Mottl’s father, he was a boat seller/broker here then; he had this upstairs and downstairs was a real estate office.

What was the name of that boat?

Philip: the boat was called ‘Aldrich’. It turned out to be the very first Pittwater ferry. It didn’t look like a ferry; 21 foot; it was probably an old putt putt before that. Anyway I looked at it and George suddenly couldn’t find the key to start it and everything went a bit pear shaped and I thought to myself; ‘well, wait a minute, I know how much it is, because the guy who was selling it had told me, so I said to him ‘I know how much it is, here’s a deposit and we’ll come back on the weekend or tomorrow.’ In the meantime I said; can you drop us on that island over there we’d like to have a look and a walk around, since we’d come all this way from Manly.

Trilby; he must have dropped us off at Bell

(wharf) I think and we went around the wrong way and ended up, because it was

Winter, in July, and we went all around the damp end, the unsunny side for that

time of year and we just arrived around on the sunny side with the sunset, the

sun going down, and there was this log cabin…

Trilby; he must have dropped us off at Bell

(wharf) I think and we went around the wrong way and ended up, because it was

Winter, in July, and we went all around the damp end, the unsunny side for that

time of year and we just arrived around on the sunny side with the sunset, the

sun going down, and there was this log cabin…

Philip: there was a log cabin on the corner, and it became known as ‘The House on Pooh Corner’, which is a story on its own. It was one of these kit log cabins I suppose, where you could extend it.

Trilby:

we saw it was for sale and this guy, the agent, was showing

it to two people. We asked if we could have a look at it; and he said ‘I just

have to drop these people back to Church Point but just please go into the house

and help yourself to a wine from the cask on the bench in there but don’t let

the Abyssinian cat out. So we sat there, on the balcony, and it wasn’t a

waterfront but it had a good view…

Trilby:

we saw it was for sale and this guy, the agent, was showing

it to two people. We asked if we could have a look at it; and he said ‘I just

have to drop these people back to Church Point but just please go into the house

and help yourself to a wine from the cask on the bench in there but don’t let

the Abyssinian cat out. So we sat there, on the balcony, and it wasn’t a

waterfront but it had a good view…

Philip: it was lovely.

Trilby: so as we walked away from it Philip

said “I’m going to buy that.”

I’m a … ‘I have to look at every house that

comes up for sale’ and have great difficulty making decisions and I thought,

‘don’t say anything, just see what happens’. So George Mottl came down the next

day and took us out on the boat and we asked ‘do you have any houses to show

us?’, looked at them. Went back and looked at the log cabin and when we went

away on the Sunday we’d committed to buying the boat and a house in the one

weekend. We rang up people and told them and they said “Goodness; it will take

you three quarters of an hour to get to the city!” but we loved

it

Philip: yes; I said ¾ of an hour, it used to take me an hour and a half to get to London, this is nothing.

So where did the Ferryman’s Cottage name come from?

Trilby: it wasn’t called that to begin with.

Philip: what happened then was.. Kingcroft and Australia gave me a whole new bite of the cherry, another seven years in that career.

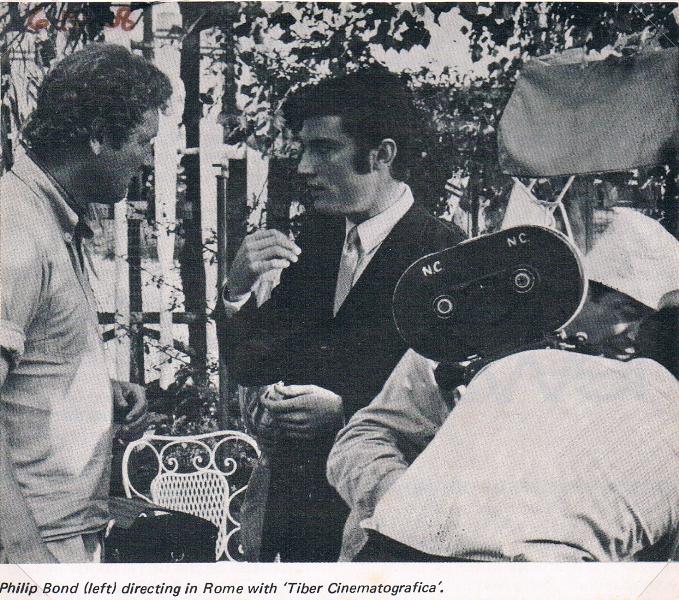

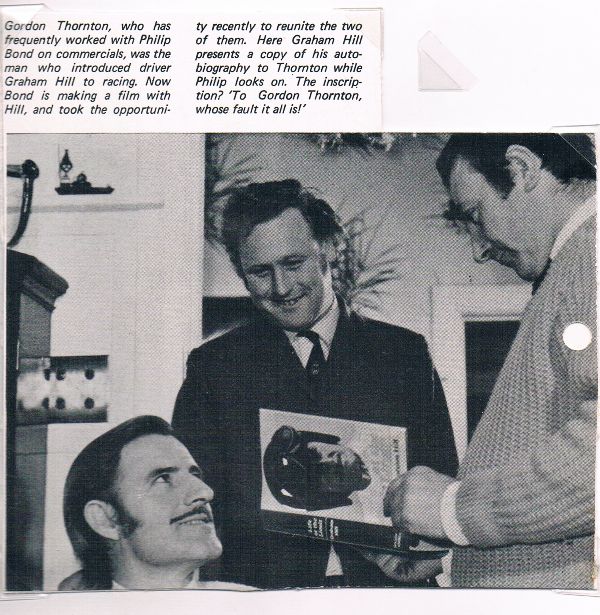

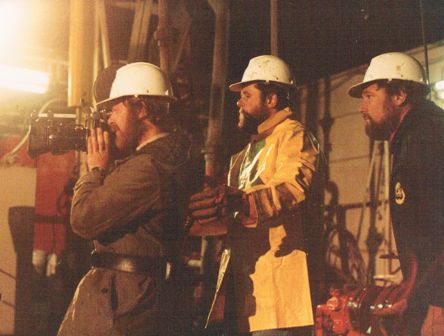

Left: Film Production Days -

Australia with Kingcroft Productions 1976-1985

Left: Film Production Days -

Australia with Kingcroft Productions 1976-1985

Trilby: Yes; you were just coming up to age 55; and he’d had a great London career and he could see that the film and television commercial business was about to go down; it was still going up then but you could see it was about to drop, and 55 is very old in that industry, there were lots of young kids in there…

Philip: I was the elder.

Trilby: Kingcroft was struggling and Philip felt guilty for taking a salary from Kingcroft, at least I think you did?

Philip: I did.

Trilby: and he thought ‘what else can I do?’ and he’d always been very good at pouring out a beer. So he decided to go back to England and have a pub.

Philip: this was to help me to decide whether I was English or Australian at first….and I didn’t know what else to do after leaving the film industry but knew I was very good at standing at a bar so I decided to go and stand behind a bar. We went on a Brewery Course, both of us, for the week and learnt all about how to do it right and how to do it wrong and then there were offers out of the blue, the same day, two pubs...

Trilby; we were offered the management of the Punch Bowl and we went in and did that for about four or five months and realised we were bloody good at pulling in people, and then we got offered two pubs. The thing about that was, there were lots of pubs; we spent eight months driving around looking at them all, at grotty pubs, a lot of people start in grotty pubs, but we wanted something else; we were 55 and didn’t have time to build something up that would take years and years. We wanted something that would suit us for about ten years and we were very fussy and then lucky; we wanted the right pub and it did take a while to find it; and then we went on this brewery course and we did shine, this would have to do with our knowledge in advertising, a combination of things, so we shone at this course and were then offered the management of two places that were opposite ends of the spectrum.

Philip: one was down in Hampshire, which was terribly run down and could only go up, but it was a beautiful place and had character; and it was clearly the one not to go for because the other one was silver service and had the old Naval commander behind the bar, who actually turned out to be a Chief Petty Officer; he had the golden chain across the waist and all of that, and it was silver service dining, and we thought ‘well this one is right at the peak of its days.’

Trilby: it was beautiful.

Philip; it was lovely, had everything …or this other one that was really grotty and half the time didn’t bother to open and the landlord’s wife had run off with the barman or something

Trilby; it was 16th century …all the opportunity we had and we ended up in a bar with no living accommodation, it was filthy, they’d had cats in there for years and it stank, took us so long to get rid of the stench.

So how long were you doing that for?

Philip: Four and a half years. It was called ‘The George Inn’ in a village called Vernham Dean which was down a little back road between Andover and Newbury; we used to say ‘if you can find us, you’re definitely lost’. So we managed to get the village to come back and once they started to come back we just took over the local; it was more like a club then a pub.

So after four and a half years of being a pub keeper you decided you were Australian?

Philip: (laughing) that’s exactly what

happened; it was the greatest realisation; it was being permanently under a

cloud in England, it was always either drizzling or raining. I can remember one

customer coming in and saying to me, “This would be the best country in the

world if it had a roof over it.”

I think that’s

what convinced me; that was it.

Trilby; there was also the Brewery; we’d worked very hard and built up a clientele and made it successful and they wanted to up the rent. And it wasn’t the kind of pub where you could put lots of staff on and we were already working really hard, you couldn’t take time off, you had to be there, and so we told the brewery to get lost and he was coming up to 60 so we decided to retire.

We still had the log cabin but both our parents died within a short time of each other; my mother had been sick and I came back out here to look after her, this would have been 1988…and of course I loved the island and the area and we’d always wanted to come back… and then his father died; we lost them on both sides within weeks of each other. So Philip came and joined me in time for the bicentennial and we then bought Ferryman’s Cottage although it wasn’t Ferryman’s Cottage then, it was a fibro shack, and it was known as Mona O’Malley’s old place because Mona had been there forever. We knocked it down and built what became known as Ferryman’s Cottage.

Philip: because it was, originally, the Ferryman’s Cottage. So we had the old ferry and the original house. So they all sort of linked in with each other.

Trilby; There were these metal slipways at the front of the property, three of them, between the Quarterdeck and us

Philip: the Curlew came up from Sydney and was rebuilt on the island.

The Ferryman's Cottage

Trilby: when we finished building Ferryman’s Cottage and had had all our friends to stay, we’d run out of projects, we were retired and we’d had to do a little bit of bed and breakfast when we’d had the pub, and we’d heard about this lady at Palm Beach and contacted her, and Pittwater Council, at that stage, didn’t want any Bed and Breakfasts in the area, of course now there’s quite a few, but this was in the days before the internet and we came out in a little book called the Australian Bed and Breakfast which sold only in bookshops, and we did Bed and Breakfast for five years and then stopped and then Rosalie and Colin came along.

So you’re back in Australia and you get involved in the Woody Point Yacht Club?

Philip: I started it with a few other chaps. What happened was we were restoring a wooden putt putt over at Woody Point on the beach there on a Sunday morning and the rules were; bring something to throw on the barbecue and a bottle of champagne. Then one day, we were sitting on the end of the jetty, and having a champagne and in my case, a fish, we’d just chuck a line in on the way over and catch something, and I said ‘we should be a club’, and they said ‘well, what will we call it?’ and I said’ well, nobody’s got a yacht, we’ll call it the Woody Point Yacht Club’... and that was the way it started.

Trilby: and then we went off, and the guy whose boat they were all fixing died, Tim Shaw, and one of the ways we wanted to keep his memory going was to keep the club going. We didn’t have much to do with it for a while because we’d gone off but one of the ways to stay involved was to keep paying our membership fees; we had June Lahm looking after our affairs while we were travelling and she made sure we were part of that and up to date, and so when we got back it had become a yacht club and by then there were a few people as members who had yachts, and somebody had started having a cocktail party as part of the club’s social functions. We turned up at that and one of the strong minded ladies said “What are you doing here? You’re not members!”

Philip laughing in background…

Trilby: and we said, excuse me…

We’re the founders…?

Philip: yes; check your list. (laughing again)

And in 1994 you were commodore.

Philip: yes, after Ian Treharne.

Trilby: we decided, when Philip became commodore, to have the first fancy dress party. When we had the pub we were always envious of people having weekends off and being able to do other things, and there was this fancy dress party going on in the village which was called ‘What you were wearing when the ship went down’ and we thought this would be great for those back on Scotland Island. When we did come down to live on the island fulltime it was around the time June Lahm’s partner of then was having his 50th, which was a fancy dress, and was fabulous; so when we went back to England we remembered these. Then when Philip was commodore we introduced, as well as or for the cocktail party that we’d have a theme of ‘what you were wearing when the ship went down’. So every year it became a fancy dress from then on.

The Timber Boat Festival and the Annual Marine Art show that came from that and became a separate event each year…

Philip: That came about because we just got too many entries by about year two or three of the Timber Boat Festival to run it in a tent. So Graham Chatfield agreed to running it in the dining room and I think the first one we ran in there we had 150 pictures. Now it’s getting to the point where we may have to start turning pictures away there are so many, we may have to establish a cut off point. I don’t run it anymore; I said to them, you know the drill, I’d rather you took it over and run all that.

Trilby: for the first three or four years it was part of the Timber Boat festival; the wives went and looked at the paintings while their husbands looked at the boats. Then it became too big and then it was decided they were both big events in their own right and to run them separately.

You’ve

always been a bit of a wordsmith and in recent years have begun putting pen to

paper under the non de plume of ‘Twitcher’ for Bayview Golf

Course, and speaking about the birds on the tees in their due

seasons..

When I was in England, or even when still at school, our House Master was walking around with binoculars, and the one thing id did learn was to appreciate and recognise all the British birds. It was not so easy when I first got here because they were all so different, even those that had the same names as all the British settlers and explorers that came out just called everything by the same name if it looked similar; the fish for example, the whiting here is nothing like the British whiting.

And you have written some short stories too now?

Yes, last January I decided to write a book which was just going to be called ‘Short stories for long Journeys’ and I contacted various editors and they said ‘oh, you’re not a writer, we can’t publish you.’ Despite the fact that this is what I’d done all my life. ‘But nobody’s ever heard of you because you don’t get your name on your tv commercials and documentaries and what have you…’…and I said ‘well, ok, but don’t you want to have a look at it at least?’

Anyway the upshot of all that was that they didn’t want to do it so I looked into this self publishing thing on Kindle and with the help of my daughter, Pippa, did it that way instead. Now the books have turned into four now, the fourth of which is just about to happen… I’m still writing it; shall do a bit later on today.

People have been telling us how great your stories are so there are a few people looking forward to this new one. What are the other two called?

The first one is called ‘Short Stories for Long Journeys’, and there’s twenty short stories in each, a few poems, all of which are based on some sort of experience in the spirit of making commercials and films in some part of the world or another, the second one is called ‘Between Gin and Tonics’, and the third is called ‘After the Brandy’. The fourth, which hopefully will be finished in the next six months or so, is called ‘Fasten Your seat Belts’. So in other words, it’s something for reading on flights. So they’re all on Kindle but because I’ve done no advertising or promoting at all it’s more or less word of mouth that’s letting people know about them. People are buying them but mine only sell for $3.99 of which I’ll probably get $1.20 which is not funding the books I want to purchase and read that are all about $15.00 !

How many children do you have Philip?

Two; my daughter is out here and runs a café called ‘Splat’ in Queenscliff. My son and his wife have a very successful restaurant down in Somerset in the UK.

What is your favourite place in Pittwater and why?

What I like to do is get in the boat and go across to what I call Treharne Cove and look to see if there’s any Sea Eagles above or in the trees, switch off the engine and just drift and listen. That’s possibly one of my favourite places in Pittwater.

What is your ‘motto for life’ or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

Well; I do live by this one: “WHEN IT STOPS BEING FUN, STOP DOING IT.”

Short

stories for Long Journeys [Kindle Edition] by Philip Bond

Short

stories for Long Journeys [Kindle Edition] by Philip Bond

A

series of entertaining short stories from all warps of life. This book is

certain to delight a wide audience with its dappled impressions and

observations. It is designed to make the long haul or short distance travel a

more pleasureable experience. With the second book in the series , the title "

Between Gin and Tonics" says it all.

These stories cover a long journey, of many, many miles, from childhood to the present day. There are stories of joy and of sadness, of truth and lies, fact and fiction. Yarns drawn from an exotically eccentric lifetime of travel and adventure across six continents. Tales that excite, amuse, annoy, entertain, inspire, accuse and bemuse, sadden and gladden to enhance your journey.

Between

Gin & Tonics [Kindle Edition] by Philip Bond

Between

Gin & Tonics [Kindle Edition] by Philip Bond

Follow up

selection of short stories to the popular "Short stories for Long Journeys" by

the same author. Philip Bond has again captured the imagination and draws one

into tales of intrigue, english country life, australian landscapes, including

the familiar roguish character "Clinker" from the first collection. A veritable

smorgasbord for all tastes, available only from Amazon.

After

The Brandy [Kindle Edition] by Philip Bond

After

The Brandy [Kindle Edition] by Philip Bond

Another excellent

selection of short stories by Philip Bond to pick up and put down at leisure.

This collection skillfully avoids any mention of children, cats, native animals,

problems, spiders other peoples pets or relatives. Philip has again captured the

imagination in his inimitable style with these brilliant eclectic tales

including our favourite rogue "Clinker" available only from

Amazon.

WPYC Australia Day Regatta - the early days.

Trilby and Philip Bond, 2013.

Scotland Island, April 2013.

Copyright Philip Bond, 2013. All Rights Reserved.